ARTS & CULTURE

ARTS & CULTURE

GLOSSARY

bohemian An artistic character whose lifestyle and attitude to work are free from conventional rules and practices.

Camden Town Group Group of artists based in London’s northern suburb of Camden whose depictions of urban life in the early twentieth century came to define an important period of English art before World War I.

Chartists Working-class activists established in 1836 to campaign for political reform and the rights of the working classes.

debtors’ prison Jails in which people who owed money to public or private firms were incarcerated until their debt could be paid.

Dickensian Resembling the period, style and often squalid conditions of nineteenth-century Britain, and in particular London, shown in the writings of Charles Dickens.

Downing Street Street off Whitehall in central London containing the residences of the Prime Minster (No. 10) and the Chancellor of the Exchequer (No. 11).

Gordon Riots, 1780 Anti-Catholic protest led by Lord George Gordon, President of the Protestant Association, fuelled by the Catholic Relief Act of 1778, which led to widespread rioting and looting across London.

Gothic Revival Artistic style originating in mid-eighteenth-century Britain before spreading across the globe. It drew inspiration from the Gothic art and architecture of ‘native’ medieval sources, often in deliberate contrast to Continental classicism.

Great Ormond Street Hospital Pioneering children’s hospital established in central London in 1852 to provide dedicated inpatient care to children.

hackney carriage A form of taxi distinguished from other taxis by its special licence held by the driver that allows them to ‘ply for hire’ or stand in a rank.

Peasants’ Revolt, 1381 Uprising among peasants of Kent and Essex that resulted in a march on London led by Wat Tyler and the unprecedented capture of the Tower of London. The young King Richard II negotiated with the peasants, though his concessions were later retracted and Tyler was killed by the Lord Mayor of London.

the Reformation Separation of the Church of England from the Catholic Church in the sixteenth century precipitated by many factors, including the effect of the Protestant Reformation in Europe and by Henry VIII’s desire to divorce his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, which the Catholic Church forbade.

the Renaissance The fundamental revival of art, literature and learning in Europe beginning in the fourteenth century that defined the transition from the medieval period to the modern world.

rookeries Impoverished and crowded tenement houses that proliferated in the nineteenth century due to rapid industrialization and intense urbanization.

suffragette movement Women’s organization established in the late nineteenth century that became a political movement in the early twentieth century campaigning for women’s rights and in particular the right to vote.

workhouse Institutions established in the fourteenth century and abolished in the twentieth century that provided accommodation for the impoverished and destitute in return for unskilled manual labour.

ART PATRONAGE

the 30-second tour

Over three centuries, London went from being a centre for the arts in Britain to a global capital. The origins of this prodigious rise can be traced to the sixteenth century, when the Reformation and the European Renaissance loosened the tight grip that the Church and the monarchy had on art. The growth of London’s aristocracy and their capacious residences paralleled the commoditization of art and the use of their homes as private galleries. Art was also used as a force for social and moral good. The eighteenth-century painter and satirist William Hogarth was a founding Governor of London’s Foundling Hospital and encouraged its use as a venue for art exhibitions and recitals, including regular performances of Handel’s Messiah. The patronage of art through exhibitions in the manner of (and an alternative to) the Paris salons was a feature of eighteenth-century London. The Dilettante Society (1732), the Foundling Hospital, the Society of Artists of Great Britain (1761) and the Royal Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (RSA, 1754) presaged the eventual establishment of the Royal Academy in 1768. The founding of the Arts Club (1863) and the rival Chelsea Arts Club (1891) continued the patronage of the arts throughout the nineteenth century.

3-SECOND SURVEY

For centuries, London’s art scene has thrived on – as much as been shaped by – the patronage of the city’s wealthiest and most influential residents.

3-MINUTE OVERVIEW

The Royal Academy (RA), founded in 1768 by 34 eminent artists and architects, sought not only to exhibit the nation’s best work but also to promote art through education and public debate. A century after its foundation, the RA moved to Burlington House, Piccadilly, where it still remains one of the nation’s leading art institutions. The RA possesses Britain’s oldest fine art library and hosts public debates and the annual Summer Exhibition.

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

JOSHUA REYNOLDS

1723–92

A founder member and the first President of the Royal Academy of Arts in 1768

JOHN SOANE

1753–1837

Architect and Royal Academy professor who converted his house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields into a museum for his huge collection of art, architectural artefacts and antiquities

CHARLES SAATCHI

1943–

One of Britain’s leading art patrons, he famously sponsored the Young British Artists throughout the 1990s

30-SECOND TEXT

Edward Denison

The Royal Academy, whose first President was Joshua Reynolds, has occupied Burlington House since 1867.

SCENES OF LONDON

the 30-second tour

London has been depicted by visual artists since the sixteenth century. Each has brought their own perspective and presented very different faces of the city. Canaletto’s depictions of the Thames present London as if it were a version of his native Venice. The French printmaker Gustave Doré, working 150 years later, captured late-Victorian industrial London as a dark satanic city. But London has produced its own artists too. William Hogarth’s work was often of a moral theme, depicting social scenes that still resonate today: A Rake’s Progress, Industry and Idleness, Beer Street and Gin Lane provide rich depictions of London life and landscape. George Cruikshank, James Gillray and Thomas Rowlandson – all born in London – presented the eighteenth-century city as a roaring, boisterous world of people mixing, fighting and filling streets, lanes, public houses and coffee shops. The vicious bite of these caricaturists was replaced in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries with social insights concerned with simple reflections on the landscapes of London life; the Camden Town Group, for example, depicted the interiors of everyday homes, cafés and shops. Perhaps the most famous London artist is J. M. W. Turner, whose paintings present the fog and smoke, railways and shipping of the working city as a majestic play of light.

3-SECOND SURVEY

London has been presented as a sublime, pretty, wonderful and wicked city by a succession of artists since the sixteenth century.

3-MINUTE OVERVIEW

Depictions of London often tell us as much about the artist as they do about London itself. But regardless of whether an artist has communicated the atmosphere, the social life, the politics, the architecture, the events, or simply the colour and form of the city, so often London is portrayed as a centre of excess and restlessness.

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

GIOVANNI ANTONIO CANAL ‘CANALETTO’

1697–1768

Venetian artist whose works were particularly popular among British ‘Grand Tourists’

WILLIAM HOGARTH

1697–1764

Influential painter, printmaker and art critic, produced a series of prints depicting London life

J. M. W. TURNER

1775–1851

Painter whose Romantic landscapes, particularly in oil, contributed to the transformation of European landscape art

30-SECOND TEXT

Nick Beech

From Canaletto to Hogarth, artists have long been inspired by London.

FILM

the 30-second tour

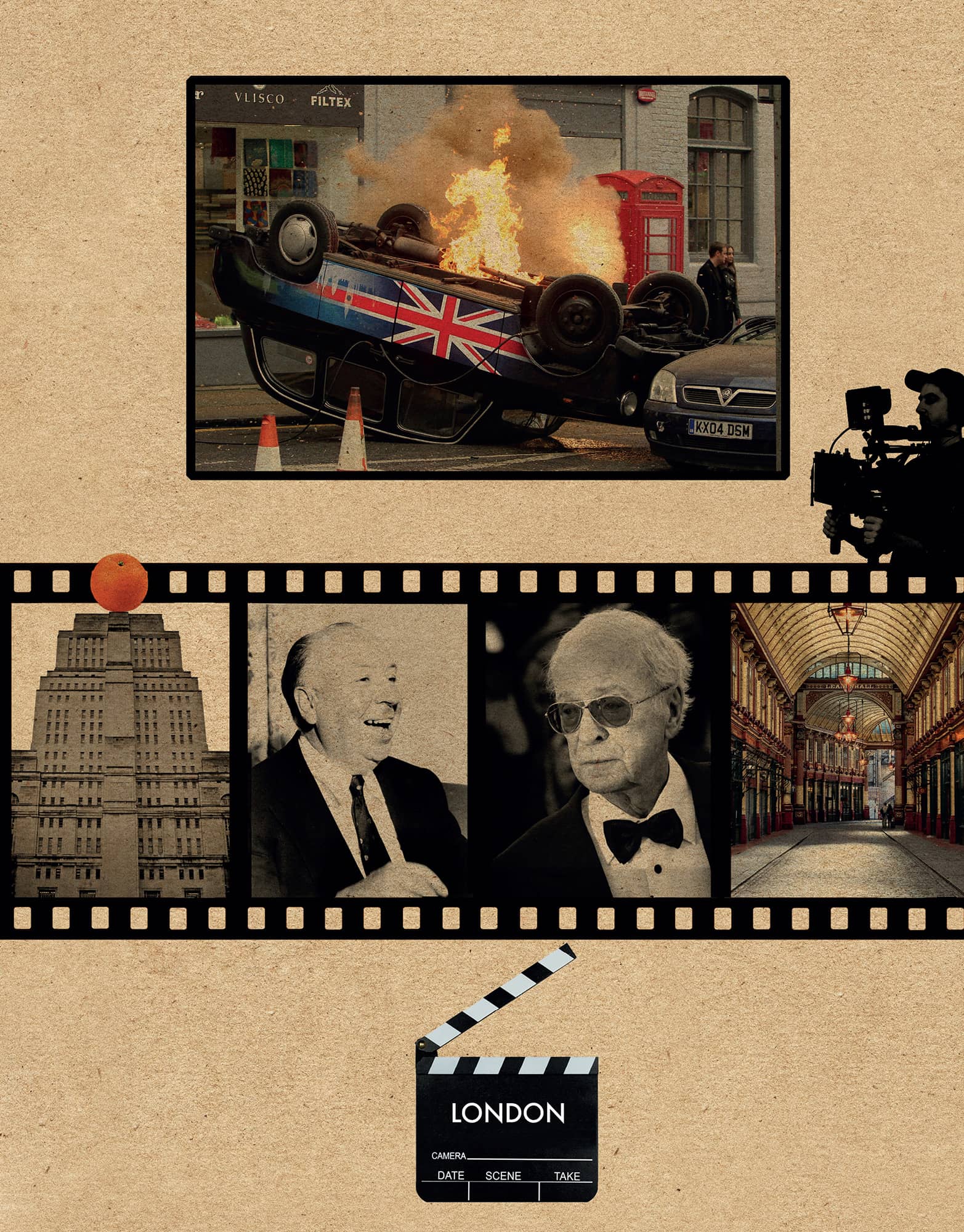

For film-makers, London is a magnificent movie set bristling with ready-made props and scenes, from Gothic gables, classical colonnades and high-tech towers to cobbled streets, concrete jungles and verdant parks and gardens. London’s most enduring cinematic depiction is its crime-ridden foggy Victorian streetscape immortalized in the film adaptations of Charles Dickens’s novels and Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories. The Harry Potter series drew on the city’s traditional characteristics when featuring George Gilbert Scott’s Gothic-Revival masterpiece The Midland Grand Hotel, with Horace Jones’s Leadenhall Market recast as Diagon Alley and the entrance to the Leaky Cauldron. Modern London has been the setting for some of the most memorable scenes in cinema history, from the dystopian casting of Charles Holden’s Senate House as the Ministry of Truth in Nineteen Eighty-Four (1984) and Thamesmead in A Clockwork Orange (1971) to the comedic horror of An American Werewolf in London (1981) or capturing modernity’s mood in The Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night (1964) and the cult classic Blow-Up (1966). London’s romantic side has also endured in film, from My Fair Lady and Mary Poppins (both 1964) to Notting Hill (1999), Shakespeare in Love (1999) and Love Actually (2003).

3-SECOND SURVEY

London is the birthplace of some of the greatest names associated with film, whether writers, actors, directors and producers, or studios.

3-MINUTE OVERVIEW

The world-famous Ealing Studios in west London became synonymous with post-war British comedies such as The Lavender Hill Mob (1951) and The Ladykillers (1955), the latter filmed in London’s King’s Cross. Both starred the London-born actor Alec Guinness, who famously played Fagin in the acclaimed adaptation of Oliver Twist (1948) by the renowned director and producer, Sir David Lean, from Croydon. Lean worked closely with another of London’s great screenwriters and actors, Noël Coward.

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

ALFRED HITCHCOCK

1899–1980

One of the greatest film directors of the twentieth century, renowned for his masterful use of suspense

MICHAEL CAINE

1933–

One of Britain’s most celebrated actors, born in Bermondsey, south London, and renowned for his strong London accent

30-SECOND TEXT

Edward Denison

London’s depiction in film has made the city familiar to audiences worldwide.

THE BLOOMSBURY GROUP

the 30-second tour

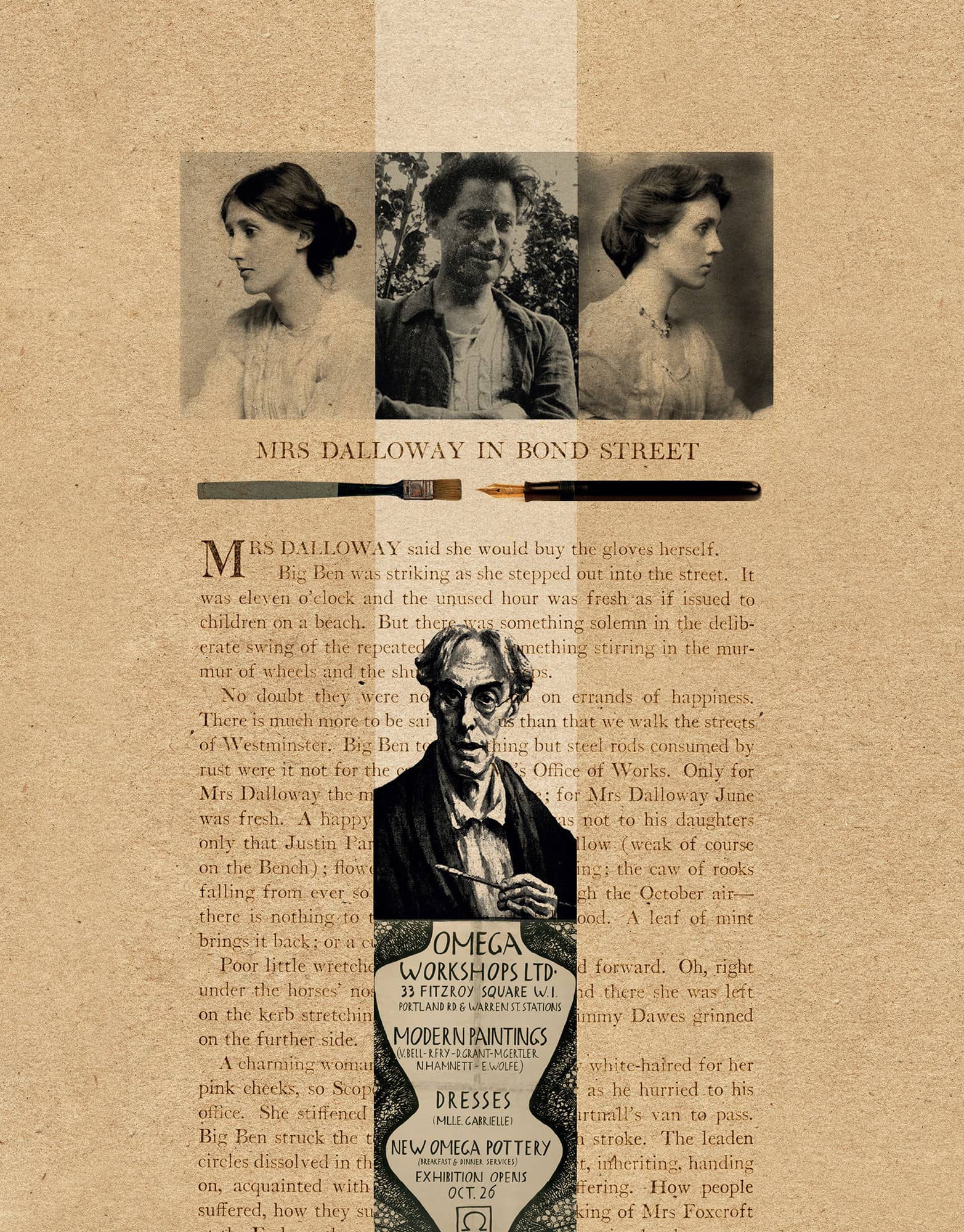

The Bloomsbury Group, a network of writers, artists, activists and dilettanti, began in Cambridge but crystallized in 1904 in Bloomsbury, then an unfashionable area of Georgian terraces and squares between Euston Road and Holborn. The men and women of the Bloomsbury Group were united by a revolt against social conventions and a belief in the power of ideas to change and improve the lives of others by rational thought, gender equality and breaking taboos. Their specialisms ranged from economics (John Maynard Keynes) through psychoanalysis (Adrian Stephen) to the better-known writing (Virginia Woolf, Lytton Strachey) and art (Roger Fry, Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant). They were arguably Britain’s chief creative and critical avant-garde before 1914. Private life and friendship were paramount, expressed in conversation and letters. Although they also spent time at their houses in the countryside, Bloomsbury remained an important geographical focus: it was cheap, bohemian and well situated for research and publishing. Fry’s Omega Workshops, set up in 1913 in Fitzroy Square, set new French-inspired styles for interiors. Virginia Woolf’s novels, especially Mrs Dalloway (1925), express the slightly delirious feeling of London life at the time – parties, domestic graces, and the interiority of private and public sadness after World War I.

3-SECOND SURVEY

Connected by family and friendship, the Bloomsbury Group was widely influential in many fields of culture.

3-MINUTE OVERVIEW

The Bloomsbury Group has suffered bad press from D. H. Lawrence onwards, accused of snobbery and mutual back-scratching. The 1970s and 1980s saw it return from obscurity and captivate scholars and public alike who wished they’d been there. It deserves a more balanced assessment, as the total range of thought and output is astonishing, even if highly uneven. Several of the houses lived in by the group survive in Gordon Square.

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

ROGER FRY

1866–1934

Introduced modern French art to London in 1910 and 1912, a thoughtful popularizer of all forms of art

VIRGINIA WOOLF

1882–1941

Learned, catty, endlessly fascinated by people, but also self-doubting to the point of death

JOHN MAYNARD KEYNES

1883–1946

Pioneer of demand-led thinking in economics, favouring public works subsidy to stimulate employment during depression

30-SECOND TEXT

Alan Powers

The Bloomsbury Group was made up of a constellation of artists including Virginia Woolf, Duncan Grant, Vanessa Bell and Roger Fry.

RED BUS, BLACK CAB

the 30-second tour

Red buses and black taxi cabs are the classic London combination, and for good reason. Most cities buy their buses and taxis off the shelf. But with London’s twisting roads, stop-start traffic and heavy payload, only bespoke designs stand the strain. Bus passenger numbers have doubled since the 1980s and in 2014 London’s buses drove almost half a billion kilometres (300 million miles). The rules for London buses were laid down in 1909. Vehicles had to be hard-wearing, simply engineered, with all parts being completely interchangeable. London Transport had its own engineers, research department and production lines, which in the 1950s created the world-famous Routemaster bus, with its iconic open rear platform. The Routemaster recently underwent a redesign, with the new model boasting three doors, two internal staircases and dashing diagonal front and rear windows. Similar attention has been paid to the design of black cabs (officially ‘hackney carriages’). London’s fleet of 23,000 cabs retain their curvy, roomy character, but will in future be powered by eco-friendly engines. One thing technology can never replace is ‘the Knowledge’. This is the test – requiring knowledge of 320 routes, 25,000 streets and 20,000 landmarks – that all black cab drivers must take before getting their badge.

3-SECOND SURVEY

Such is the complexity and congestion of London streets that since 1909 buses and taxis have had to be specially designed to cope with the workload.

3-MINUTE OVERVIEW

‘Hold very tight please!’ Once the clarion call of London’s ‘clippies’ (bus conductors) who swung daringly from the rail on the open platform of a Routemaster, this cry can now only be heard on Route 15 from Tower Hill to Trafalgar Square. Only ten of these classic buses still work London’s streets, but of the 2,876 built between 1954 and 1968, incredibly over 1,200 survive elsewhere, owned by collectors, museums and bus companies as far afield as China and Australia.

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHY

THOMAS HEATHERWICK

1970–

London-born designer who wowed the world with his Olympic Cauldron during the opening ceremony for the 2012 Games. His distinctive remodelling of the classic Routemaster also debuted in London in 2012

30-SECOND TEXT

Simon Inglis

London prides itself on its efficient transport system and its design heritage, which come together in the world famous old and new Routemaster bus and the black cab.

PUNK

the 30-second tour

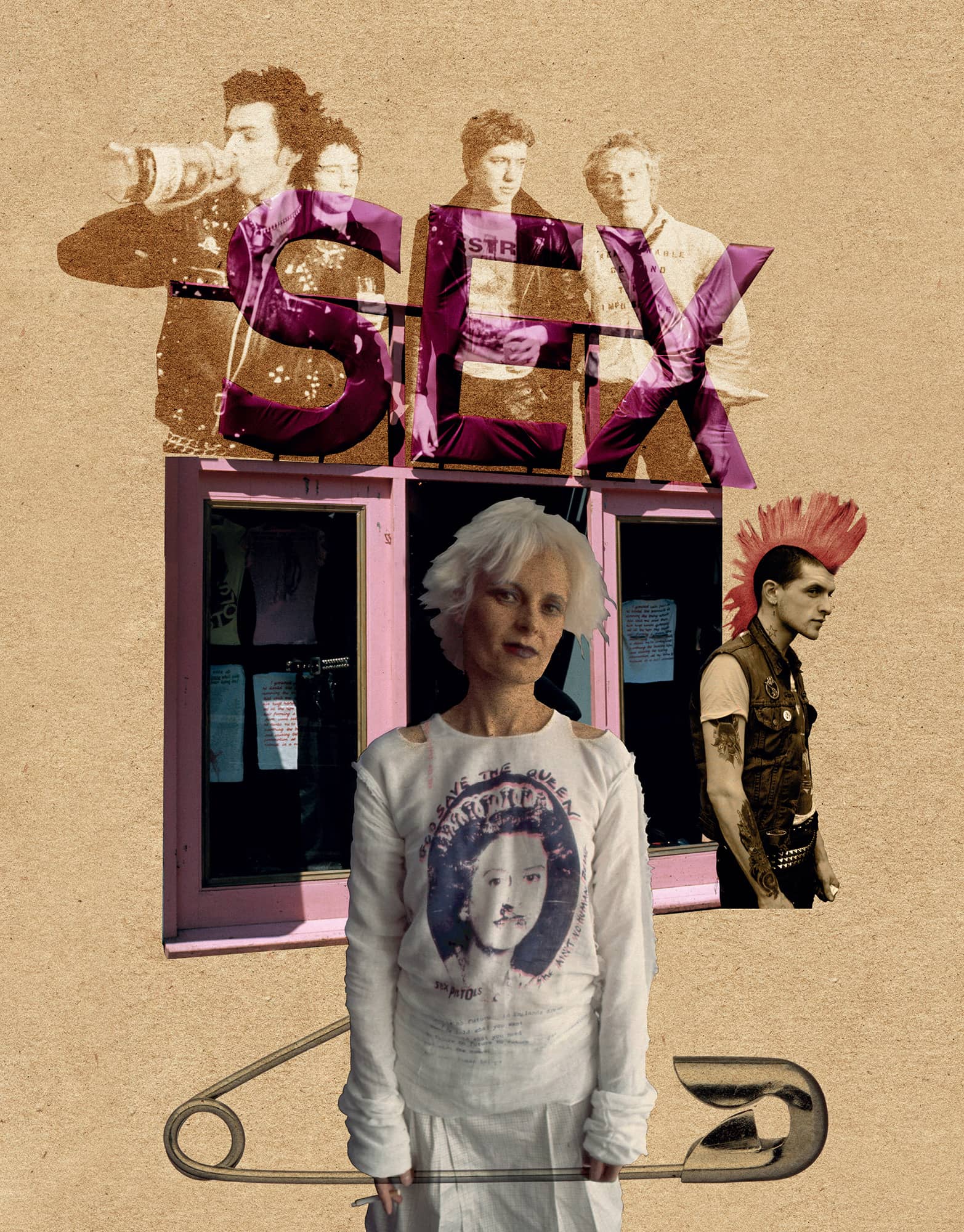

Punk was not born in London, but the city swiftly became its spiritual home. The embryonic energy of early punk emanating across the Atlantic found the perfect host amid the economic misery and social boredom of mid-1970s London. Punk was a cultural attitude fervently embraced by disillusioned and disenfranchised youth, finding its most potent expression in music – raw, angry and primordial. The soundtrack to British punk rock was forged in London’s dingy pubs and seedy nightclubs – El Paradise, 100 Club, the Marquee and the Roxy – before reverberating around the globe. Punk’s most influential band was the Sex Pistols, comprising four teenagers from across London brought together by the impresario Malcolm McLaren who owned a fashion boutique called Sex on Chelsea’s King’s Road with his partner, fashion designer Vivienne Westwood. Today, decades after punk exploded in all its swearing, sneering and spitting fury into British popular culture, the theatrical image of the angry figure clad in Dr Marten boots, with brightly coloured hair and safety-pinned attire has become a symbol of London’s counter-culture. Behind this stereotype, punk remains one of the most potent expressions in a long and quintessentially British tradition of opposing the establishment.

3-SECOND SURVEY

Punk may have been born in New York, but it made its home in London where it enjoyed an uproarious adolescence.

3-MINUTE OVERVIEW

Punk’s dystopian vision of London was a consistent catalyst and compelling backdrop for some of its greatest anthems and the inspiration for many songs including: The Clash’s ‘London’s Burning’, ‘White Riot’, ‘White Man in Hammersmith Palais’ and ‘Guns of Brixton’; ‘Down in the Tube Station at Midnight’ and ‘A Bomb in Wardour Street’ by The Jam; ‘Dark Streets of London’, ‘Rainy Night in Soho’ and ‘London You’re a Lady’ by The Pogues; and Madness’s ‘We are London’.

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

JOE STRUMMER

1952–2002

Lead singer of The Clash and writer of some of the most critically acclaimed punk songs

JOHNNY ROTTEN

1956–

Lead singer of the Sex Pistols famed for his piercing sardonic gaze and green teeth that inspired his nickname

SID VICIOUS

1957–79

Sex Pistols’ bassist and media antihero who died of a heroin overdose having been accused of murdering his girlfriend Nancy Spungen

30-SECOND TEXT

Edward Denison

Vivienne Westwood’s boutique, Sex, was at the centre of punk’s nihilistic style.

PROTEST

the 30-second tour

As the centre of political power in Britain, London has always been a site of both peaceful and violent protest. Its dense network of streets has provided a theatre for marches, while public squares and greens have become spaces for gatherings and communal action, from the mass Chartist meeting on Kennington Common (1848) to the Poll Tax (1990) and the recent anti-austerity riots of Trafalgar and Parliament Squares. London also has a record of quieter vigils, whether outside Parliament or in front of national embassies, as well as the democratic tradition of the symbolic presentation of petitions to Downing Street. Such protests might have their roots in the Peasants’ Revolt (1381) or the days of anti-Catholic violence known as the Gordon Riots (1780), but also draw on a lexicon of public gatherings, ranging from religious processions, public hangings and the knockabout hustings of the British electoral tradition. Although often male-dominated, the first quarter of the twentieth century was also peppered by the actions of the suffragettes, who burned down the refreshment pavilion at Kew Gardens and whose threat to public artworks caused radical changes to museum and gallery admissions. Today, London’s spaces increasingly outlaw public protest, from Westminster Square itself to private developments such as Canary Wharf and King’s Cross.

3-SECOND SURVEY

London’s maze of streets and public spaces provide the map on which political protest can take physical form – both peacefully and with violence.

3-MINUTE OVERVIEW

Many of the symbolic forms of protest that we recognize today came into focus during the Chartist campaign for electoral reform in the late 1830s and 1840s. Mass gatherings, public speeches and the presentation of vast public petitions to the government (one with a claimed 6 million signatures) coincided with civic unrest during a time of economic depression, causing the government to send 8,000 soldiers to police the Kennington Common gathering in 1848.

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

LORD GEORGE GORDON

1751–93

Politician who led a march of 50,000 in opposition to Catholic Emancipation, leading to several days of violent rioting

WILLIAM CUFFAY

1788–1870

Chartist leader and organizer of tailors’ strikes for an eight-hour day (1834)

OLIVE WHARRY

1886–1947

Artist and suffragette sent to Holloway Prison in 1913 for setting the Kew Gardens tea pavilion on fire. She went on hunger strike for 32 days

30-SECOND TEXT

Matthew Shaw

Londoners have a healthy disrespect for authority and willingly exercise their right to protest.