ENIGMATIC LONDON

ENIGMATIC LONDON

GLOSSARY

Black Death, 1348 Known at the time as the Great Pestilence, the Black Death was the most devastating pandemic ever caused by the bubonic plague, killing more than half of Europe’s population and half London’s population (40,000) in two years after its arrival in 1348.

bubonic plague A type of bacterial infection responsible for successive pandemics that killed millions of people worldwide from the fourteenth to seventeenth centuries.

City of London A city and county of Britain governed by the City of London Corporation covering a geographic area broadly defined by the walls of the Roman settlement, also referred to as the Square Mile.

dot map A method of surveying using data collection recorded in the form of dots on a map to represent the incidence and geographic location of a phenomenon.

grave-goods Objects buried with a corpse, usually in the form of personal possessions and artefacts or offerings believed to help the deceased in the afterlife.

Great Fire, 1666 London’s largest ever fire, which started in a bakery in Pudding Lane and over the course of three days swept through the medieval streetscape, destroying more than 13,000 wooden buildings, including 87 parish churches and the old St Paul’s Cathedral.

Great Plague, 1665 The last major outbreak of the bubonic plague, which killed more than 100,000 Londoners, or a quarter of the city’s population.

Industrial Revolution The rise and proliferation of industrial forms of production and manufacturing over manual labour and craft production, originating in Britain in the mid-seventeenth century and quickly spreading throughout the world.

Londinium The Roman title for London, established shortly after their invasion of Britain in 43 CE, from which the modern city gains its name.

miasma Ancient theory purporting that the spread of disease was caused by noxious air caused by rotting matter, which held sway until disproved by the advance of modern science in the mid-nineteenth century.

Peasants’ Revolt, 1381 Uprising among peasants of Kent and Essex that resulted in a march on London led by Wat Tyler and the unprecedented capture of the Tower of London. The young King Richard II negotiated with the peasants, though his concessions were later retracted and Tyler was killed by the Lord Mayor of London.

resurrectionist Also known as body-snatchers, resurrectionists exhumed dead bodies to sell for anatomical research, a practice that reached its peak in the eighteenth century when medical research was flourishing and the law did little to deter such activities.

GRAVEYARDS

the 30-second tour

Dating to 4000 BCE, London’s earliest known burial site is located in Blackwall in the East End. Prehistoric graveyards, mainly cremation fields, have also been discovered in west London, while there is evidence that the Thames may also have been used for prehistoric burial. Roman Londinium was surrounded by graveyards, containing thousands of burials with exotic grave-goods. Medieval monasteries had extensive cemeteries, with senior clergy and wealthy patrons buried in the churches, and the poorer outside, sometimes in mass graves at times of catastrophe. Legend has it that London is covered in plague pits, but only two small Black Death cemeteries have been excavated. Increased population, urbanization and epidemics such as cholera and typhoid caused major problems. In the nineteenth century, the burial grounds choked and bodies could not fully decompose. There were notorious problems with resurrectionists robbing graves to sell bodies for anatomical study. London’s graveyards were closed by Act of Parliament in 1851, yet people kept dying. One solution was to open a cemetery outside London served by special train; thus the London Necropolis Company was founded and the Brookwood Cemetery opened. London’s modern cemeteries are almost full; where will the dead be buried in future?

3-SECOND SURVEY

Over the millennia, London’s graveyards have gone from small islands of commemoration to elaborate landscapes devoted to the dead.

3-MINUTE OVERVIEW

In the eighteenth century concerns were raised about overflowing small parish cemeteries but it wasn’t until 1832 that the first of what became known as the Magnificent Seven Cemeteries was opened to counter the problem. These are architectural masterpieces and havens of solitude from modern, hectic London, to be found at Kensal Green, Highgate, West Norwood, Abney Park, Nunhead, Brompton and Bow.

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHY

MRS BASIL HOLMES

1861–unknown

Researched and published the fascinating and informative London Burial Grounds in 1897, describing nearly 500 sites

30-SECOND TEXT

Jane Sidell

London is a paradise for ghost hunters, abounding with hundreds of burial grounds from the small and private to the vast and public.

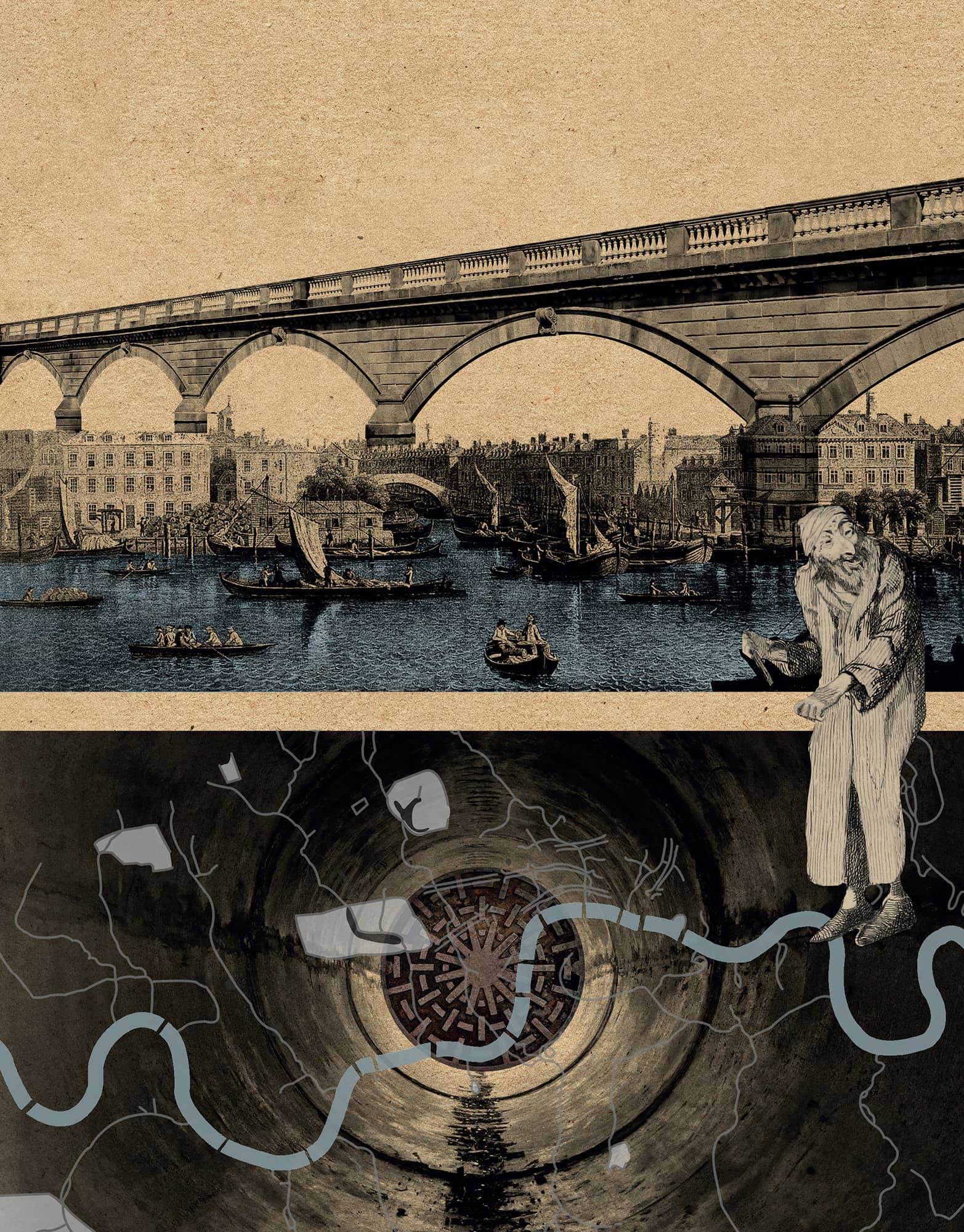

SUBTERRANEAN LONDON

the 30-second tour

Built on a chalky basin under soft clay, two millennia of development mean a deep history and active infrastructure are well preserved below London. The city’s rich archaeological record reveals Roman bathhouses and medieval priories below office blocks and estates. The Thames Tunnel was the world’s first tunnel under a navigable river. Opened in 1843, it was the work of Marc and Isambard Kingdom Brunel, Britain’s great engineering heroes. Next was the world’s first underground railway, in 1863, beginning a vast transport network 6 to 56 metres (20 to 185 feet) below the ground. But perhaps the mightiest underground achievement was Joseph Bazalgette’s extraordinary sewer system, opened in 1865, revolutionizing Londoners’ waste. The Thames Embankments of the 1870s effectively covered Bazalgette’s low-level sewer, the underground railway, telegraph services and water mains in a palimpsest of subterranean improvements. And from 1927 even the post was carried 20 metres (65 feet) underground on a driverless railway line. Underground became a place of refuge in World War II when eight deep-level air-raid shelters were constructed across London; and again when Clapham South’s shelter was used to temporarily house West Indian immigrants arriving on the Empire Windrush in 1948.

3-SECOND SURVEY

London’s extensive archaeological record, subterranean networks of Victorian improvements and twentieth-century communication systems amount to centuries of history below ground.

3-MINUTE OVERVIEW

It was the Great Stink of 1858, and awful outbreaks of cholera, that galvanized the Metropolitan Board of Works to invest in a proper sewer system. Civil engineer Joseph Bazalgette designed the ingenious network of tunnels that carried waste eastwards along gravitational outfall routes. Thanks to his foresight – constructing the tunnels twice as wide as Victorians needed – it remains the foundation for today’s sewers.

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHY

JOSEPH BAZALGETTE

1819–91

Civil engineer who masterminded the London Victorian sewer system that still serves modern London

30-SECOND TEXT

Emily Gee

With one of the world’s largest underground railway systems and hundreds of miles of Victorian sewers, there’s much more to London than meets the eye!

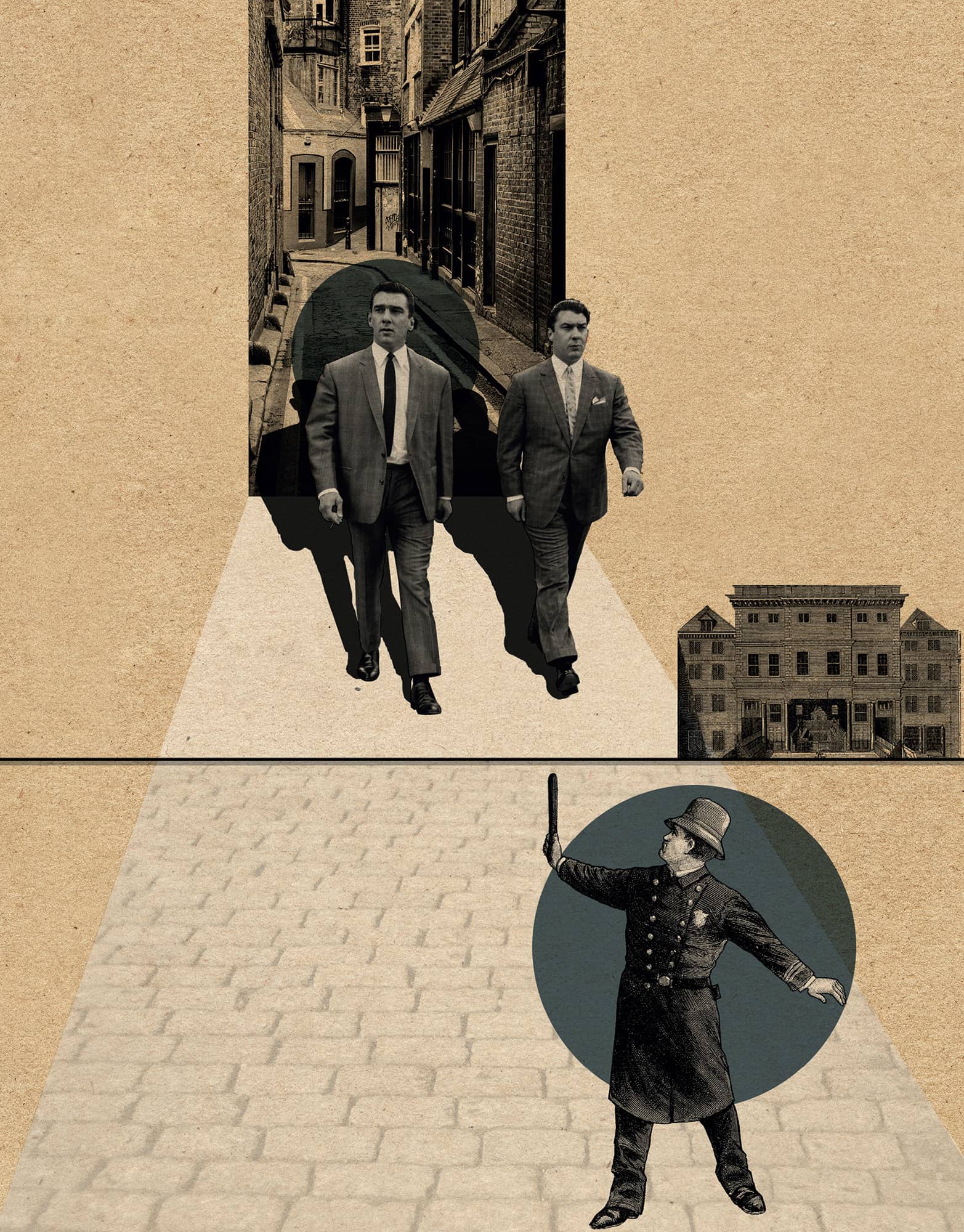

CRIME

the 30-second tour

London has a long and bloody relationship with crime, the consequences of which have bestowed on the world such familiar names as Scotland Yard, the Old Bailey and Sherlock Holmes. Crime has shaped the city’s social, physical and legal character, pioneering new forms of crime prevention, legal institutions and even literary genres. The Romans were the first to establish an organized system of crime prevention in London. In 1285 the Statute Victatis London dealt with policing, which was administered locally by paid watchmen. By the eighteenth century, the Industrial Revolution precipitated London’s rapid urbanization and expansion, demanding a more effective and organized system of policing. In 1798 the Thames River Police was established and later subsumed into the newly created Metropolitan Police following the 1829 Metropolitan Police Act. Colonel Charles Rowan and Richard Mayne (from whom the policeman’s moniker ‘Bobbie’ was derived) were placed in charge of the new force, conducting their work from 4 Whitehall Place, which backed onto a small courtyard called Great Scotland Yard, the name becoming synonymous with the Metropolitan Police Headquarters ever since. The City of London Police, established in 1832, maintained their independence from the Metropolitan Police.

3-SECOND SURVEY

London has three independent police forces: the Metropolitan Police, the City of London Police and the British Transport Police.

3-MINUTE OVERVIEW

London has hosted some of the world’s most infamous criminals, from Jack the Ripper, who terrorized Victorian London, to the violent East End gangland twins, Ronald and Reginald Kray. One of London’s most extraordinary crimes was the Sidney Street Siege of 1911. An impasse between police and the Latvian Gardstein gang led to the Home Secretary, Winston Churchill, sending in heavy artillery, but the gang members died before they arrived when the house burned down.

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

SIR CHARLES ROWAN & SIR RICHARD MAYNE

1782–1852 & 1796–1868

Joint first Commissioners of the Metropolitan Police

GILBERT MACKENZIE TRENCH

1885–1979

Surveyor and architect for the Metropolitan Police. Designed the blue Police Box (1928) immortalized by its depiction as the Tardis in Dr Who

30-SECOND TEXT

Edward Denison

Crime has long held a central place in London’s popular culture.

TORTURE & EXECUTION

the 30-second tour

Until the nineteenth century, public executions drew huge crowds who revelled in the spectacle of the hangman’s noose. London’s longest serving gallows was at Tyburn, now beneath Marble Arch. For over six centuries prisoners were paraded from Newgate Prison along the route of Oxford Street to be hanged. When Tyburn closed in 1783, Newgate erected its own gallows from which people were hanged in public until 1868 when the hanging of Fenian, Michael Barrett, marked the end of execution as public entertainment. Nearby Smithfield was a multifunctional execution ground. In 1305 William Wallace, the Scottish patriot, was hanged, disembowelled and cut into pieces there. Wat Tyler, the leader of the Peasants’ Revolt, was beheaded there in 1381, and in 1410 John Badby was burned in a barrel for denying substantiation. Smithfield also hosted Britain’s first public boiling, when Richard Rouse, the Bishop of Rochester’s cook, was boiled to death in 1531. Other popular gallows were at Execution Dock in Wapping and Charing Cross, which also boasted a pillory for public flogging. At 2pm on 30 January 1649, Londoners observed the city’s most famous execution when King Charles I was led out of a window of Banqueting House on Whitehall onto a scaffold and beheaded in one fell swoop of the executioner’s axe.

3-SECOND SURVEY

Londoners loved a good hanging. A carnival atmosphere accompanied public executions, which attracted tens of thousands of spectators who revelled in a fellow Londoner’s expiry.

3-MINUTE OVERVIEW

The Tower of London is synonymous with execution and torture. Public executions were conducted outside on Tower Hill, except on rare occasions when the condemned was a celebrity. Henry VIII’s wives, Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard, both lost their heads on Tower Green, inside the Tower compound. All manner of grisly contraptions were contrived to extract confessions or exact punishment, from the rack, which stretched bodies, to the scavenger’s daughter, which compressed them.

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

WILLIAM WALLACE

c. 1270–1305

Met his end at Smithfield in 1305. He was hanged, eviscerated so that he could witness his entrails being cooked, then beheaded and quartered, his limbs being sent to the four corners of Britain

GUY FAWKES

1570–1606

Was hanged, drawn and quartered in Old Palace Yard outside the Houses of Parliament, which he had tried to blow up

CHARLES I

1600–49

Was the subject of one of Britain’s most famous executions when he was beheaded on a scaffold in Whitehall in 1649

30-SECOND TEXT

Edward Denison

Londoners used to revel in the spectacle of a public execution.

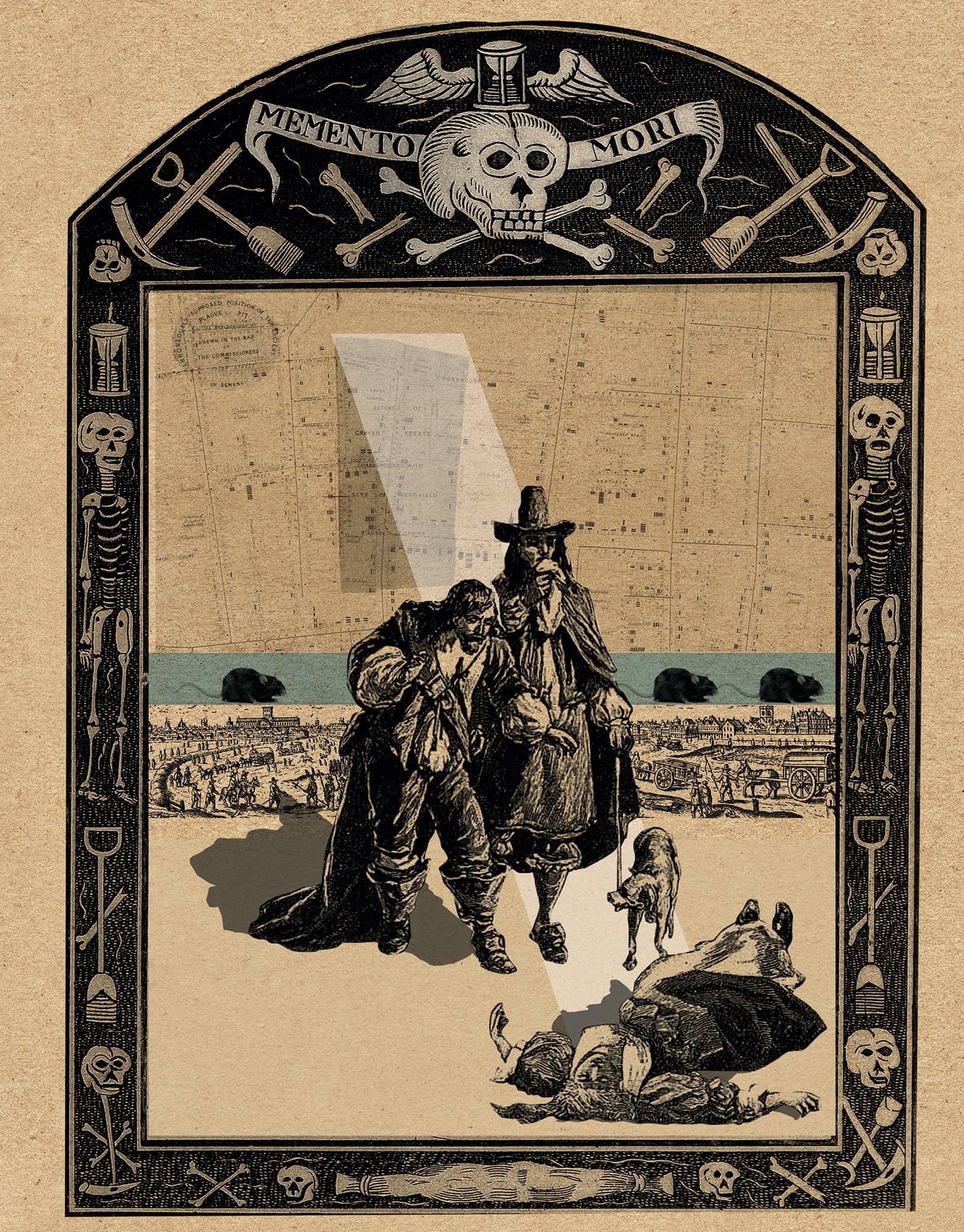

EPIDEMICS

the 30-second tour

London is a crowded city. Proximity to others, limited hygiene facilities, easily contaminated water and a constant stream of visitors have ensured its history has been marked by disease, epidemic and plague. Fear of disease shaped its social patterns, with the rich fleeing the city for the countryside, and poorer areas being feared as sites of infection. The Black Death of 1348 and the Great Plague of 1665 are the most notorious of over 40 outbreaks of the bubonic plague, which not only spread terror, but also posed civic authorities practical challenges such as how to dispose of the dead or how to alert the authorities to infection. Poor sanitary conditions aided major outbreaks of typhoid, typhus and cholera in the nineteenth century, which then helped to generate a fear of the poor and of immigrants (who were believed to carry disease) and support belief in disease-spreading miasmas, as well as inspiring the first serious attempts to map and mitigate such challenges to public health. Echoes of such past epidemics remain in the fabric of the city, such as the discovery of plague pits under construction sites, while modern epidemics, such as HIV/AIDS and the rise of drug-resistant tuberculosis, continue to trouble public health authorities.

3-SECOND SURVEY

London’s population has always been troubled by epidemics, creating cultural repercussions as well as posing a threat to life itself.

3-MINUTE OVERVIEW

In 1854, Dr John Snow famously removed the handle of the water pump in Broad Street in modern-day Soho, thereby halting a cholera epidemic. Although recent research suggests that the epidemic was already waning before Snow’s action, and that he did not use a ‘dot map’ to locate the source of the disease, he has entered the history books as a heroic example of the success of a scientific approach to public health and disease.

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHY

DR JOHN SNOW

1813—1858

Physician and pioneer epidemiologist, who was sceptical of the miasma theory of disease and instead blamed the transmission of cholera on contaminated water

30-SECOND TEXT

Matthew Shaw

London’s history is beset by epidemics of one form or another, the worst of which culled up to half of the city’s population.

LOST RIVERS

the 30-second tour

The River Thames might be the largest and most famous waterway in London, but it has never been alone in draining the region’s water, whether it has fallen from the sky, risen from springs or been flushed from our homes. The area around London was once laced with over 20 rivers winding their way to the Thames, but today nearly all have been buried beneath the vast metropolis, channelled into culverts, pipes and sewers. Hidden from view, these tributaries have left an indelible mark on the city’s physical, etymological, literary and political landscapes. Echoes of the small brook that ran through the Roman wall reverberate in the conjoined name of Walbrook in the City of London. The annular form of the Oval is a fossilized relic of the Effra’s once meandering course. The Fleet’s stinking condition by the nineteenth century inspired local resident, Charles Dickens, to make it the setting for Fagin’s lair in Oliver Twist. London’s Royal Parks were furnished with lakes created by diverting rivers such as the Westbourne, which filled Hyde Park’s Serpentine. London’s rivers have left their mark on the political map too, with these ancient obstacles forming boundaries that continue to separate local authorities – the Fleet divides Camden and Islington just as the Westbourne separates Westminster from Kensington and Chelsea.

3-SECOND SURVEY

London sits in a geological basin that was once awash with small rivers that ran like veins into the main artery of the Thames.

3-MINUTE OVERVIEW

London’s largest lost river was the Fleet, which flowed from Hampstead Heath through Camden Town to the Thames, where it was once nearly 200 metres (650 feet) wide and where Christopher Wren proposed Venetian-style embankments. Swimmers would frequent this brook around St Pancras, but by the nineteenth century it had deteriorated severely. The foul-smelling ditch was covered and today it is a sewer beneath Farringdon Road, though its ancient course is evidenced in the steep slopes around Clerkenwell and Holborn Viaduct.

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

CHRISTOPHER WREN

1632–1723

Architect who supervised major improvements to the Fleet in the late seventeenth century

CHARLES DICKENS

1812–70

Lived near the banks of the Fleet and was inspired by the impoverished setting created by this once proud river

30-SECOND TEXT

Edward Denison

London’s submerged rivers are remembered in place names, topography, street patterns and political boundaries.

MAPPING LONDON

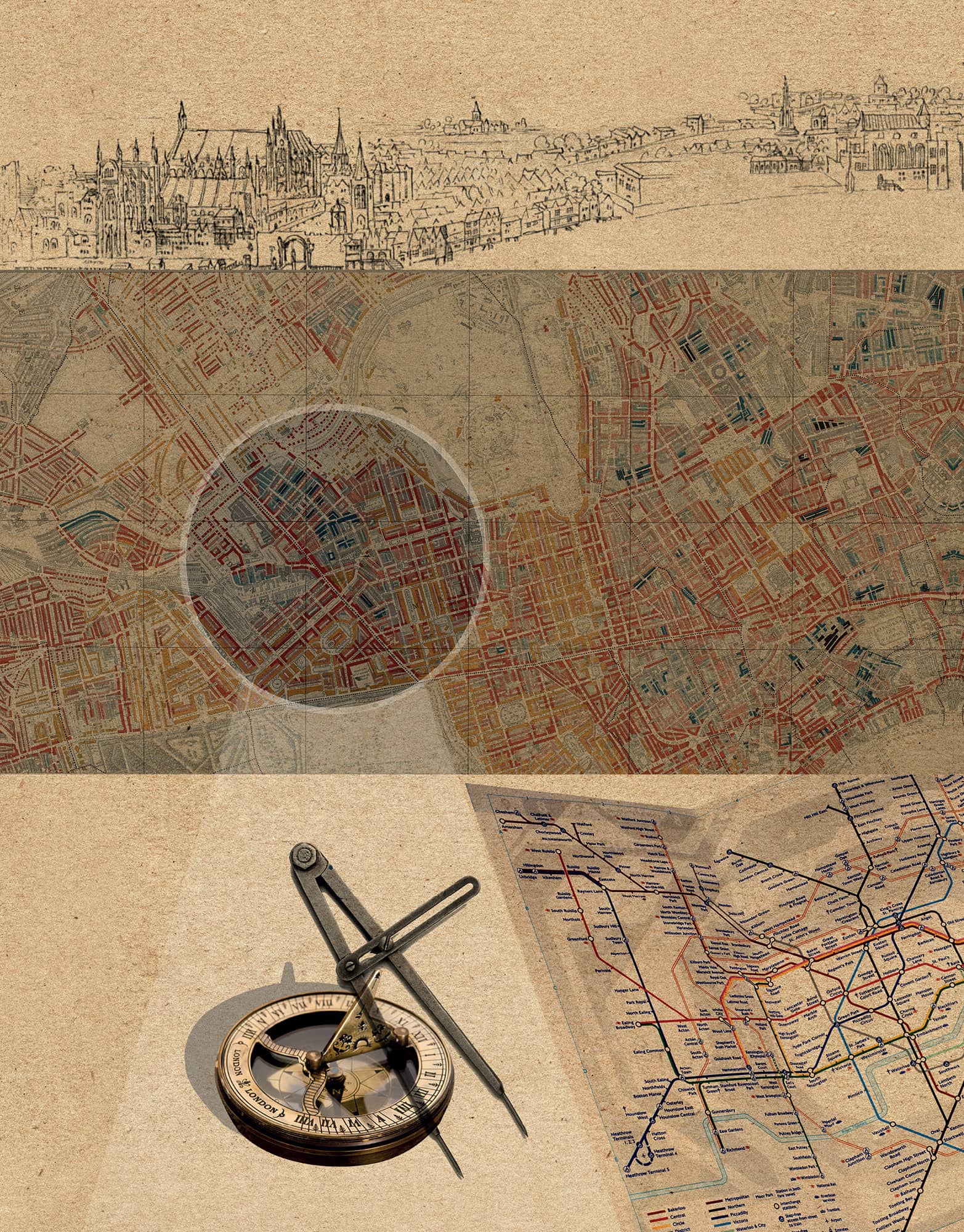

the 30-second tour

London has been pictorially recorded since the first maps of the city as a whole emerged in the 1550s. The artists Wyngaerde and Hollar meticulously captured the layout and topography of late medieval Westminster, the City of London and Southwark in their panoramas of 1543 and 1647. These Renaissance depictions would have been an utter revelation for contemporary Londoners. Maps were more widely used following the Great Fire, such as in 1677 when John Leake recorded the remaining buildings and the zone of devastation. This would be repeated three centuries later during World War II when the government collated information gathered by air-raid wardens to map the degree of loss to London’s buildings and, by correlation, human life. Equally unsettling, yet useful to historians, are Charles Booth’s maps from the 1890s, which also used colour to map London’s social classes. Colour was introduced again in Harry Beck’s map of 1931, which made a design triumph of the London Underground system and became the model for underground railway maps around the world. Around this time, Phyllis Pearsall began her epic journey to capture every road in London in the best-known street atlas: the trusty A-Z, which has assisted motorists and pedestrians alike ever since.

3-SECOND SURVEY

London was first mapped as a city in the sixteenth century and has been captured in beautiful, harrowing and useful maps through the centuries.

3-MINUTE OVERVIEW

In the 1890s, the reformer and social researcher, Charles Booth, set out to record the wealth and poverty of Londoners in an extraordinarily detailed map: Life and Labour of the People in London. His army of researchers went door-to-door recording residents’ work and incomes and colour-coding these in seven bands from the ‘Lowest class. Vicious, semi-criminal’ (black) to ‘Upper-middle and Upper classes. Wealthy’ (yellow). Pockets of black and dark blue next to swathes of yellow and red illustrate how intermingled late Victorian London was.

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

ANTON VAN DEN WYNGAERDE & WENCESLAUS HOLLAR

1525–71 & 1607–77

Artists who created the first panoramas of London

CHARLES BOOTH

1840–1916

Mapped the economic reality of late Victorian London in graphic colour

HARRY BECK

1902–74

Designed London Underground’s iconic map

PHYLLIS PEARSALL

1906–96

Created London’s street atlas, the A-Z

30-SECOND TEXT

Emily Gee

People have tried to make sense of London by mapping its myriad features.