Chapter Three

Work (Sucks)

You can be a boss or you can get a job

—Shy Glizzy, “Awwsome”

There’s a contradiction in the premise so far: On the one hand, every kid is supposed to spend their childhood readying themselves for a good job in the skills-based information economy. On the other hand, improvements in productive technology mean an overall decrease in labor costs. That means workers get paid a smaller portion of the value they create as their productivity increases. In aggregate, this operates like a bait and switch: Employers convince kids and their families to invest in training by holding out the promise of good jobs, while firms use this very same training to reduce labor costs. The better workers get, the more money and time we put into building up our human capital, the worse the jobs get. And that’s a big problem because, as we’ve seen over the last two chapters, America is producing some damn good workers.

We’ve already seen a detailed and representative example of how the labor market has changed: the higher education sector. In Chapter 2, we looked over the Delta Cost Project study on the shifting composition of the higher education workforce. Universities have reduced the share of nonprofessional campus workers—jobs that largely did not require college education but still paid living wages—through costly investment in automation and digitization. The middle-income jobs that universities haven’t been able to automate have been outsourced to for-profit contractors who can do a better job managing (read: keeping to a minimum) employee wages and benefits. The contractors will sometimes even pay for the privilege—as when Barnes & Noble takes over a campus bookstore or McDonald’s a food court concession. On the classroom side, a glut of qualified graduates facing an unwelcoming job market has pushed down the cost of instruction labor. Graduate instructors and adjunct lecturers now teach the majority of college classes, and the tenured professor seems to be going extinct, with the title, security, perks, and pay scale reserved for a lucky few and the occasional hire whose fame extends beyond their subject field. At the top, salaries for administrators (and surgeons and athletic coaches) now reach into the millions, as they work to keep everyone else’s compensation as low as possible.

Higher education is just one industry, and it follows—sometimes leads—the same trends as the rest of the labor market. But colleges aren’t just shifting the composition of their own workforce; they’re facilitating wider changes as well. Across the economy, bad jobs are getting worse, good jobs are getting better, and the middle is disappearing. University of North Carolina sociologist Arne L. Kalleberg calls this move “polarization.” As Millennials enter the workforce, we’ve faced a set of conditions that are permanently different than what previous generations have experienced. As Kalleberg puts it:

The growing gap between good-and bad-quality jobs is a long-term structural feature of the changing labor market. Polarized and precarious employment systems result from the economic restructuring and removal of institutional protections that have been occurring since the 1970s; they are not merely temporary features of the business cycle that will self-correct once economic conditions improve. In particular, bad jobs are no longer vestigial but, rather, are a central—and in some cases growing—portion of employment in the United States.1

When older commentators compare the current labor market to past ones, they usually disguise the profound and lasting changes that have occurred over the past few decades. But when the elder generations set the stakes for childhood education and achievement as high as they do, they’re being more honest: Where you end up on the job distribution map after all that time in school really is more important than it used to be. It’s harder to compete for a good job, the bad jobs you can hope to fall back on are worse than they used to be, and both good and bad jobs are less secure. The intense anxiety that has overcome American childhood flows from a reasonable fear of un-, under-, and just plain lousy employment.

To see what roles young people are being readied to fill in twenty-first-century America, we need to understand changes in the job market over the period in question. Jobs are the way most Americans afford to live week after week, month after month, the way most parents can afford to raise children, and what we spend a lot of time preparing kids to do. Despite changing a lot over the past thirty to forty years, the relation between employers and workers still structures American lives. It controls not only the access to income, the ability to pay back educational debts, and the ability to rent a room, buy a house, or start a family, but also public goods like medical care and retirement support. We’ve put the reproduction of society in the hands of owners motivated purely by profit. As a result, the consequences of career success and failure are growing heavier as time goes on. Work is intensifying across the board, abetted by communications technology that erases the distinction between work-time and the rest of life. For young people entering or preparing to enter the labor market, these extraordinary developments have always been the way things are.

3.1 The Changing Character of Work

In his book-length report Good Jobs, Bad Jobs, Kalleberg takes a macroscopic view of changes in the American job market from the 1970s to the 2000s. (Because the study is such a strong and well-supported survey, I’ll be referring to Kalleberg’s summaries often throughout this chapter.) What he found is totally inconsistent with what’s supposed to be labor’s deal with the twenty-first century: The population gets more educated, more effective, better skilled, and in return, it’s rewarded with high-paying postindustrial jobs. Instead, Kalleberg found the polarization mentioned above, as well as decreasing job security across both good and bad jobs. Despite all the preparatory work, all the new college degrees, all the investment in human capital, the rewards haven’t kept up with the costs for most.

The growth of a “new economy” characterized by more knowledge-intensive work has been accompanied by the accelerated pace of technological innovation and the continued expansion of service industries as the principal sources of jobs. Political policies such as the replacement of welfare by workfare programs in the 1990s have made it essential for people to participate in paid employment at the same time that jobs have become more precarious. The labor force has become more diverse, with marked increases in the number of women, non-white, older, and immigrant workers, and growing divides between people with different amounts of education. Ideological changes have supported these structural changes, with shifts toward greater individualism and personal accountability for work and life replacing notions of collective responsibility.2

Every bit of this so-called progress has made employees both desperately productive and productively desperate, while the profits from their labor accrue to a shrinking ownership class. From this perspective, all that work in childhood seems motivated more by fear of a lousy future than by hope for dignity, security, and leisure time. “Since both good jobs (for example, well-paid consultants) and bad jobs are generally insecure,” Kalleberg writes, “it has become increasingly difficult to distinguish good and bad jobs on the basis of their degree of security.”3 Paying to train employees you might not need later is inefficient, and inefficiency is mismanagement. As a result, today’s employers are scared of commitment. The inequality that results isn’t cyclical—these aren’t just temporary growing pains as workers adjust to market demand for new skills. It’s the successful and continued development of a wage labor system in which owners always think of workers as just another cost to be reduced.

There are a lot of ways to talk about this dynamic, a lot of metrics and statistics and anecdotal data we could use to illustrate how most workers are living with less. Because the world of policy analysis doesn’t have the tools to look at the comparative worsening conditions of people’s everyday lives directly, each measure has its problems—but looking at each of them can help us glimpse the bigger picture.

3.2 Getting Paid

Take the question of wages: The category of wages doesn’t include income derived from rents or investments. Hedge fund managers are fighting an ongoing battle to keep their astronomical compensation categorized as investment income instead of wages, to avoid taxes, and this also skews the distribution. Many low-wage jobs are off the books and don’t show up in government data. Which is all to say, the richest and poorest Americans aren’t represented in our wage measures. And yet, the numbers still show growing polarization and the evaporation of middle-income jobs.

The most important confounding variable when it comes to American labor compensation is gender. As social and educational barriers to women’s participation in the workforce have eroded, firms have looked to women as a lower-wage alternative. Women still aren’t paid as well as men for the same productivity, but the wage gap has closed significantly since the late 1970s. Even though the gap persists, its narrowing has a large effect on historical measures of compensation. When you don’t separate the numbers by gender, the narrowing gender wage gap pushes the average wage up significantly, but that doesn’t mean the quality of jobs has risen. Rather, it’s an example of firms trying out new strategies to keep their costs down by growing the pool of available labor.

Even with those caveats in place, this is how Kalleberg describes the body of research on wages by quintile:

Wages have stagnated for most of the labor force since the 1970s, especially for men. Rates of real wage growth in the United States have averaged less than 1 percent per year since 1973….Median wages for men (50th percentile) have remained stagnant, at nearly $18 per hour, while median wages for women have increased from $11.28 in 1973 to $14.55 in 2009. Wages for men in the twentieth percentile have fallen from almost $12 per hour in 1973 to $10 per hour in 2009; while wages for women in the lowest quintile have increased slightly, from about $8 per hour in 1973 to about $9 per hour in 2009.4

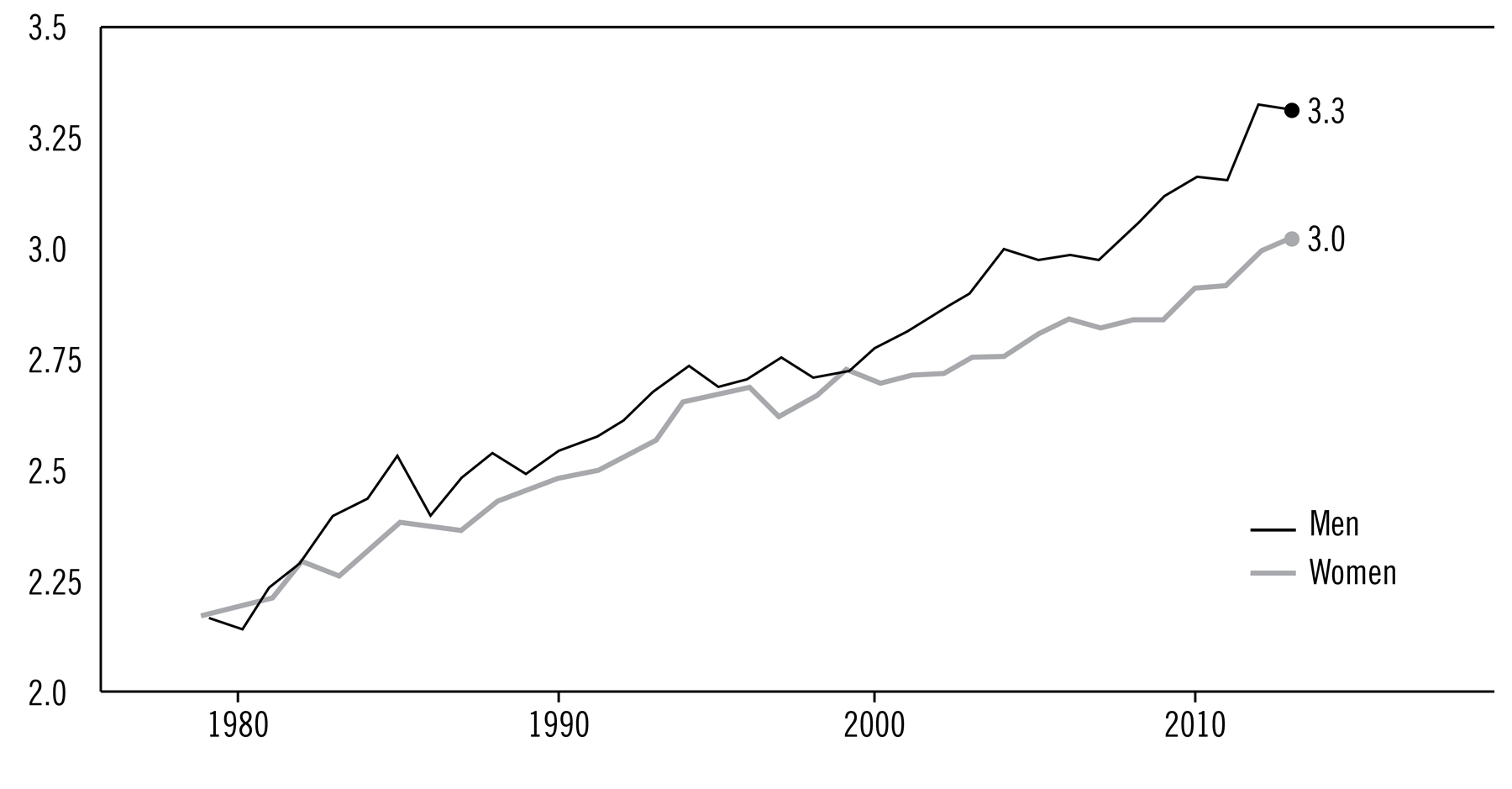

He calculated the relations between different deciles over time and found that the ratio between the bottom of the wage scale and the middle has been steady since the mid-1990s. The ratio between the top 10 percent and the median decile of wage earners, on the other hand, has consistently escalated over the same period. “It is the increase in jobs with very high wages—the top 10 percent, or even the top 1 or 5 percent,” Kalleberg writes, “—that is primarily responsible for driving the overall increases in wage inequality in the United States since the mid-to late-1980s.”5 A report from the Economic Policy Institute (EPI) disaggregated inequality between the median wage earned and the ninety-fifth percentile by gender and found steady, nearly equal growth in inequality for both men and women.6 That means inequality between male and female wage earners has narrowed overall, but inequality within each gender group has grown.

Wage Inequality Has Dramatically Increased Among Both Men and Women Over the Last 35 Years

Wage gap* between the 95th and 50th percentiles,** by gender, 1979–2013

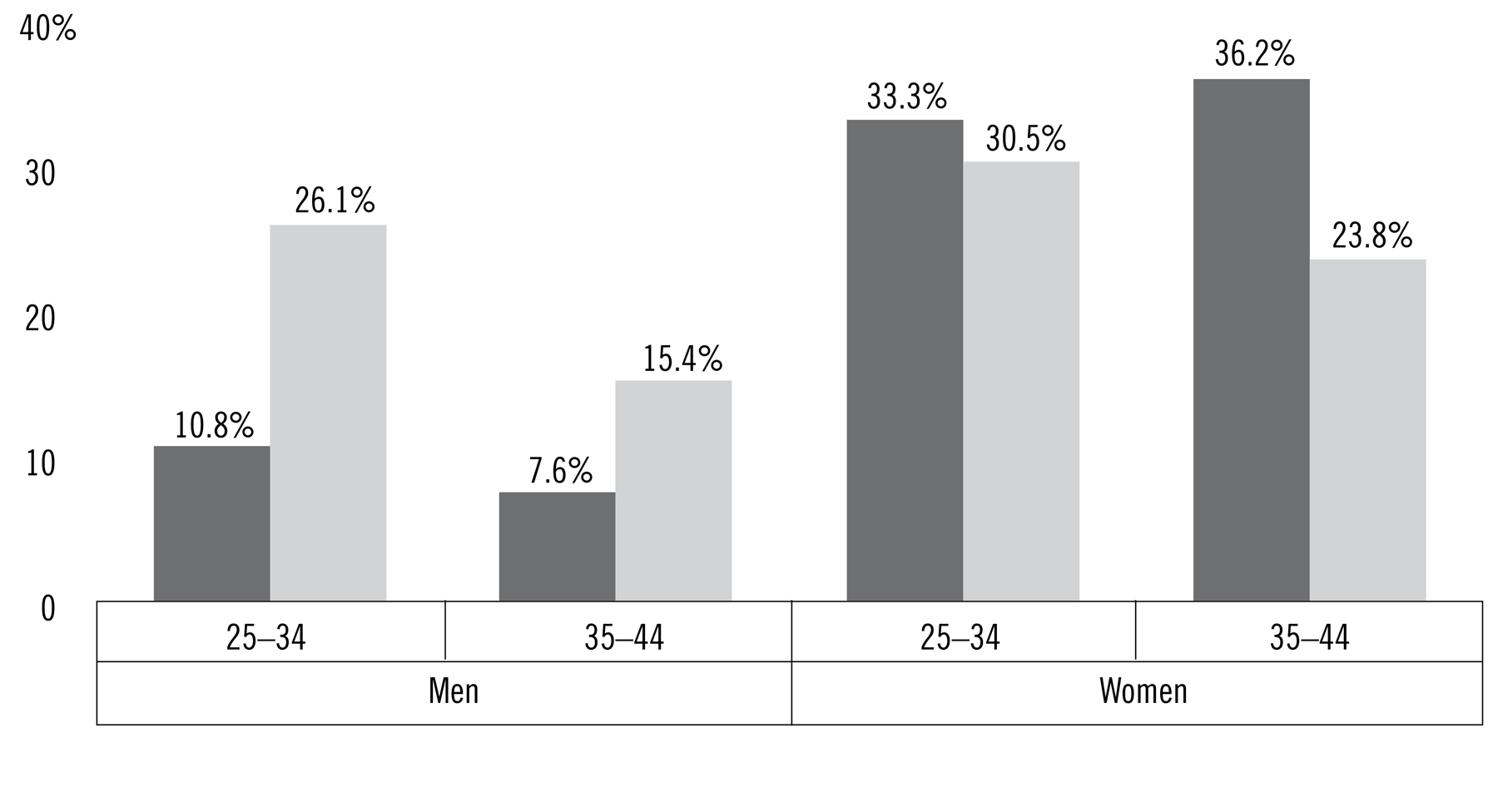

An Increasing Share of Men of Child-Rearing Age Earn Low Wages

Share of workers earning poverty-level hourly wages, by gender and age group, 1979 and 2013

Note: The poverty-level wage in 2013 was $11.45.

Another report from the EPI compared the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ number of workers earning poverty-level wages in 1979 and 2013 as divided by age and gender.7 In 1979, the relations between the numbers make sense for the late-ish twentieth century: 10.8 percent of male workers aged twenty-five to thirty-four and 7.6 percent of male workers aged thirty-five to forty-four worked at or under the poverty line. On the women’s side, the age gap was the same size but in the other direction: one-third of younger women workers worked for poverty wages in 1979, compared to 36.2 percent of older women. This reflects the larger proportion of women moving into higher-paid skilled jobs. But by 2013, younger workers were at a very serious disadvantage: The age gap for male workers more than tripled, with 26.1 percent of younger and 15.4 percent of older male workers under or at poverty pay. For women, the direction of the gap changed, with a higher proportion of younger workers under the threshold. While women did bad jobs at a much higher rate than men during the twentieth century, in 2013 younger male workers were more likely to work at or below the poverty level than older women wage earners. Most of that difference was due not to the improvement of women’s wages, but to the increase in the number of young men working for low wages. Being under thirty-five is now correlated with poverty wages.

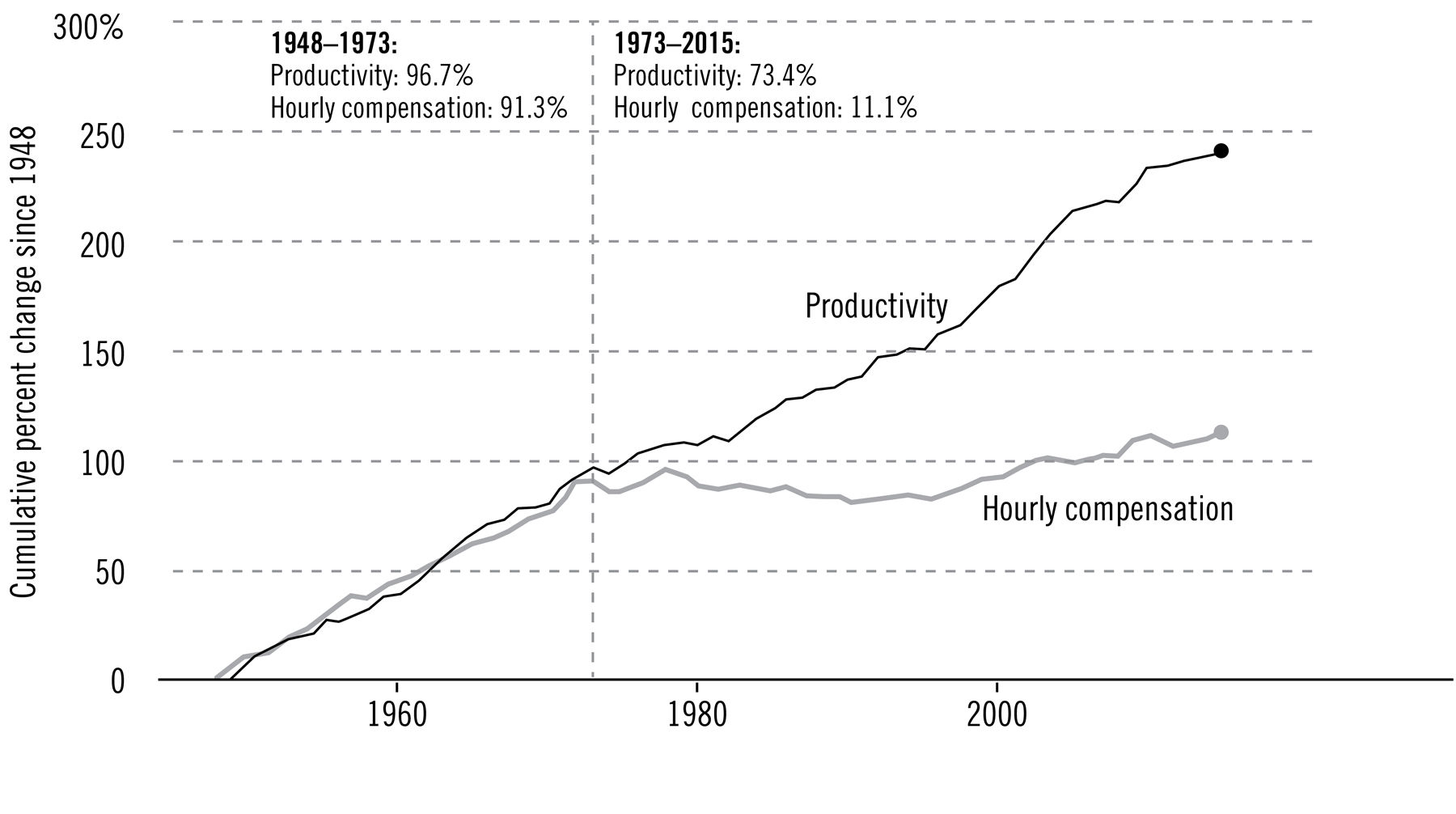

Disconnect Between Productivity and a Typical Worker’s Compensation, 1948–2015

Note: Data are for average hourly compensation of production/nonsupervisory workers in the private sector and net productivity of the total economy. “Net productivity” is the growth of output of goods and services minus depreciation per hour worked.

Just because the quality of jobs has tanked, that doesn’t mean the quality of workers and their work has gone down as well. Productivity hasn’t followed the stagnant wage trend. In fact, nonsupervisory workers’ productivity increased rapidly between 1972 and 2009, while real wages dipped.8 Until the 1970s, both metrics grew together; their disjuncture is perhaps the single phenomenon that defines Millennials thus far. Since young workers represent both a jump in productivity and a decrease in labor costs, this means we’re generating novel levels of “surplus value”—productivity beyond what workers receive in compensation. This is, of course, the goal of employers, executives, and the management consultants they hire to improve firm efficiency. It’s not just their habit to step on labor costs, it’s their fiduciary duty to shareholders.

3.3 Polarization

Commentators have a lot of ways to talk about the labor market’s heightened stakes. A favorite one is the “skills gap,” in which employers stall as they wait for better-educated workers. But that doesn’t accord very well with an economy in which profits and inequality are both up.

Productive technology has aided a lot in this development, allowing managers to hyperrationalize all of their inputs, including and especially labor. The manager’s job is to extract the most production from workers at the smallest cost, and managers are handsomely paid for it. Private equity firms, for example, have made untold billions by buying up companies, lowering labor costs (by means of layoffs, outsourcing, and increasing employee workloads), showing a quick turnaround in a firm’s numbers, and selling it off again, all primed and ready for the twenty-first-century global economy. These corporate raiders are the market’s shock troops, and over the past few decades they’ve twisted and prodded and cut companies into proper shape. The same forces are molding young people themselves into the shape that owners and investors want. From our bathroom breaks to our sleep schedules to our emotional availability, Millennials are growing up highly attuned to the needs of capital markets. We are encouraged to strategize and scheme to find places, times, and roles where we can be effectively put to work. Efficiency is our existential purpose, and we are a generation of finely honed tools, crafted from embryos to be lean, mean production machines.

The jobs that are set to last in the twenty-first century are the ones that are irreducibly human—the ones that robots can’t do better, or faster, or cheaper, or maybe that they can’t do at all. At both good and bad poles of job quality, employers need more affective labor from employees. Affective labor (or feeling work) engages what the Italian theorist Paolo Virno calls our “bioanthropological constants”—the innate capacities and practices that distinguish our species, like language and games and mutual understanding. A psychologist is doing affective labor, but so is a Starbucks barista. Any job it’s impossible to do while sobbing probably includes some affective labor. Under the midcentury labor regime we call Fordism, workers functioned as nonmechanical parts on a mechanical assembly line, moving, manipulating, and packaging physical objects. But as owners and market pressures pushed automation and digitization, the production process replaced American rote-task workers with robots and workers overseas whenever possible—that is, whenever the firms could get ahold of the capital to make the investments.

Post-Fordism, as some thinkers call the labor model that came next, requires people to behave like the talking animals we are. Here’s how Virno explains the growing demand for affective work: “In contemporary labor processes, there are thoughts and discourses which function as productive ‘machines,’ without having to adopt the form of a mechanical body or of an electronic valve.”9 We’re still on an assembly line of sorts, but instead of connecting workers’ hands, the line connects brains, mouths, and ears.

The growth of affective labor hasn’t patched up the hole left by the decline in industrial labor; instead, it’s driven the top and bottom of the job market further apart.

Over years of analysis, economist David Autor (of MIT and the National Bureau of Economic Research) has split work into three categories based on the type of tasks required: routine, manual, and abstract. Routine tasks characterize those middle jobs that have evaporated consistently since 1960: gigs like “bookkeeping, clerical work, and repetitive production tasks.” Manual tasks, Autor writes, “require situational adaptability, visual and language recognition, and in-person interactions,” and are associated with “bad” service jobs, like “janitors and cleaners, home health aides, security personnel, and motor vehicle operators.”10 Abstract tasks—tasks that involve “problem-solving capabilities, intuition, and persuasion”—have grown as a share too.11 On both the high and low ends, more work requires the communication and understanding of emotions and ideas. This humanization of work is one of the results of firms automating mechanizable jobs in the middle of the income distribution. It also spells more work for workers; “Service with a smile” is harder than “Service with whatever face you feel like making.”

What this means intergenerationally is that, as job training has become a bigger part of childhood, kids are being prepared to work with their feelings and ideas. Or, if they’re on the wrong side of polarization, other people’s feelings and ideas. They’re being managed to work with their emotions, and to do it fast, with attention to detail, and well. Society’s stressors and pressures, consciously and unconsciously, forge kids into the right applicants for the jobs of the near future.

3.4 The Feminization of Labor

The missing center of the job distribution, the routine tasks that have been largely mechanized and computerized, were built by and for male workers. As we saw earlier in the chapter, that balance has shifted, with women exceeding the male education rate and entering the workforce at higher levels and higher income brackets than they used to. This isn’t just because women were cheaper and at least as competent—though that’s undeniably part of it too—it’s because women are better trained by society for the jobs that have been resistant to automation. British scholar Nina Power wrote about the feminization of labor in her book, One Dimensional Woman:

One does not need to be an essentialist about traditionally “female” traits (for example, loquacity, caring, relationality, empathy) to think there is something notable going on here: women are encouraged to regard themselves as good communicators, the kind of person who’d be “ideal” for agency or call-center work. The professional woman needs no specific skills as she is simply professional, that is to say, perfect for the kind of work that deals with communication in its purest sense.12

On both sides of polarization, the jobs lasting and being created are “women’s work,” evoking the same qualities women practice every day by doing a disproportionate amount of unpaid emotional and domestic labor. Power’s idea of feminization in work as a pattern within capitalist development finds support in the employment numbers. We’ve already seen how the gendered wage gap has narrowed in the past decades, but women not doing as badly as their counterparts hardly justifies proclaiming “the end of men,” as the writer Hanna Rosin did in a monumentally popular piece for the Atlantic in 2010, and then in a book two years later. “Man has been the dominant sex since, well, the dawn of mankind. But for the first time in human history, that is changing—and with shocking speed,”13 Rosin wrote. Is Millennial gender hierarchy shifting as fast as everything else?

There’s decent evidence that the answer is yes, and not just at the level of theory or rhetoric. And though women’s gains haven’t been evenly distributed, the data on jobs confirms that we have undergone a real shift, even if it’s not quite as dramatic as Rosin makes it out to be. Here’s how Autor summarizes the state of American male workers since the late twentieth century:

Males as a group have adapted comparatively poorly to the changing labor market. Male educational attainment has slowed and male labor force participation has secularly [over the long term] declined. For males without a four-year college degree, wages have stagnated or fallen over three decades. And as these males have moved out of middle-skill blue-collar jobs, they have generally moved downward in the occupational skill and earnings distribution.14

Combine this with the stereotype of white-collar men as less masculine than manual and routine workers, and the “feminization of labor” looks like a very real phenomenon. But instead of the optimistic portrait of female empowerment that commentators like Rosin and Sheryl Sandberg paint, feminization reflects employers’ successful attempts to reduce labor costs. Women’s labor market participation has grown just as job demands intensify and wages stagnate.

As we saw earlier in the chapter, the trend of women’s work improving as they joined the labor force—i.e., fewer women in each generation working for poverty-level wages—has ended, and that ending coincides with the broader move toward feminization. The increase in paid work among mothers is part of an overall increase in their weekly labor hours, not a replacement for domestic tasks. It’s hard to work out the exact relation, but the “end of men” definitely hasn’t been a zero-sum gain for women workers, most of whom (judging by the end of progress out of poverty-level jobs) seem to have hit their heads on the glass ceiling. However, some men look at these labor market changes in the light of the expansion of women’s rights within marriage (like the right to own property and decline sex) and feel they’ve lost ground. A smaller group of men called men’s rights activists, or MRAs, have knit a total ideology around their sense of lost privilege and a desire to turn back the clock on American heterosexual relations. But their assumption that if men take a hit on the job market it’s to the advantage of women is a bad guess.

The feminization of labor involves a declining quality of life for working men and women within heterosexual family units. In her book Pressed for Time: The Acceleration of Life in Digital Capitalism, sociologist Judy Wajcman explains how the process works at the family level:

The major change has come from working women themselves, who reduce their time in unpaid labor at home as they move into the workforce. However, they do not remotely reduce their housework hour-for-hour for time spent in paid labor. And while their male partners increase their own time in housework, this is not nearly as much as working wives reduce theirs. The upshot is that rather less unpaid household labor gets done overall in the dual-earner household—but women’s total combined time in paid and unpaid household labor is substantially greater than is the typical nonemployed women’s in domestic labor alone….The working woman is much busier than either her male colleague or her housewife counterpart.15

It’s important not to blame the wrong actor and to make sure we keep our eyes on the bottom line: Women are working more overall, men are doing more housework, and yet there’s less housework getting done and less financial stability. This is what happens when all work becomes more like women’s work: workers working more for less pay. We can see why corporations have adapted to the idea of women in the labor force. Plus, the ownership class can redirect popular blame for lousy work relations toward feminists. Millennial gender relations have been shaped by these changes in labor dynamics, and we can’t understand the phenomenon of young misogyny without understanding the workplace.

Just because some men’s work tended to be better at a time when single-worker families were more common doesn’t mean we can return to the former by returning to the latter. But that’s the narrative misogynists use to interpret what’s going on and how it could be fixed, and they’ve attracted a lot of angry and confused men who aren’t sure about their place in the world. One antidote to this kind of thinking is an alternative framework for why and how workers (of all genders) came to be in such a precarious position.

3.5 Precarity

Like feminization, the term “precarity” has spread from radical corners to the mainstream, as commentators, analysts, and average folks alike reach for a word to describe the nature of the change in the employer-employee relationship during Millennials’ lifetimes. Precarity means that jobs are less secure, based on at-will rather than fixed-duration contracts; it means unreliable hours and the breakdown between the workday and the rest of an employee’s time; it means taking on the intense responsibility of “good” jobs alongside the shoddy compensation and lack of respect that come with “bad” jobs; it means workers doing more with less, and employers getting more for less. More than any other single term, “precarity” sums up the changed nature of American jobs over the last generation. And not only the jobs; young people curl around this changing labor structure like vines on a trellis. We are become precarity.

In his book 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, Columbia University professor Jonathan Crary describes how market logic has forced itself into the whole of workers’ daily lives. Precarity digs the basement on labor costs deeper, pushing the limits on how much employers can juice out of employees. Speaking broadly, there are three ways to do that: increase worker productivity, decrease compensation, and increase labor-time. It’s the third of these that Crary focuses on in 24/7. “By the last decades of the twentieth century and into the present, with the collapse of controlled or mitigated forms of capitalism in the United States and Europe, there has ceased to be any internal necessity for having rest and recuperation as components of economic growth and profitability,” he writes. “Time for human rest and regeneration is now simply too expensive to be structurally possible within contemporary capitalism.”16 Free time can always turn to productivity, so when productivity is properly managed, there is no such thing as free time. Instead, like cell phones that are only meant to be turned off for upgrades, Millennials are on 24/7. In a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention survey, over two-thirds of high schoolers report getting fewer than eight hours of sleep per night,17 a situation the agency has labeled a “public health crisis.”18

Aside from the myriad physiological effects of prolonged sleep loss, this 24/7 life has serious psychosocial effects for the people who attempt it. Adjusting to being always on is hard work, and it’s not for nothing. Employees who can labor when others sleep have an advantage, and in this market, someone is always willing to seize an advantage. In the start-up sector, where the main thing some entrepreneurs have to invest is their own work-time, every hour of sleep is a liability. Whether it’s because of enthusiasm, economic insecurity, or too many screens with too many feeds that never stop scrolling, Millennials are restless creatures. “24/7 is shaped around individual goals of competitiveness, advancement, acquisitiveness, personal security, and comfort at the expense of others,” Crary writes. “The future is so close at hand that it is imaginable only by its continuity with the striving for individual gain or survival in the shallowest of presents.”19 If enough of us start living this way, then staying up late isn’t just about pursuing an advantage, it’s about not being made vulnerable. Like animals that don’t want to be prey, young workers have become quite adept at staying aware and responsive at all times.

This hyperalert lifestyle doesn’t sound particularly appealing for the people living it, but for employers, it’s a dream come true. Or, I should say, a plan come to fruition. Twenty-four/seven work is a crucial aspect of precarious labor relationships. On the unfortunate side of polarization, lower-skill jobs may not provide employees (if they’re even categorized that way, rather than as “independent contractors”—or even worse, paid off the books with no official status to speak of) with a full forty-hour workweek, but that doesn’t mean they’re exempt from 24/7 time pressures. Employers value flexibility, and the more time workers could be potentially working, the more available they are on nights and weekends, the more valuable they are. You don’t get paid for the time you spend available and unused, since the compensation is hourly, but part-time retail workers (for example) still can’t draw a clear line between work-time and the rest of their lives, because they never know when the boss might need them. According to the National Longitudinal Study of Youth data, nearly 40 percent of early-career workers receive their work schedules a week or less in advance.20 That’s not a lot of time in which to plan your life.

On the professional side of polarization, the proportion of men and women working more than fifty hours a week has grown significantly.21 Innovations in productive technology make it possible for these high-skill employees to be effectively at work wherever or whenever they happen to be in space and time. There have always been people who spend all their time working—some of them better compensated than others—but at least in professional jobs, this condition has generalized. No longer are a good education and a good career dependable precursors to a life with lots of leisure time. For young people who are working hard to put themselves on the successful side, they’re setting themselves up for more of the same. This road is no mountain climb: It’s a treadmill.

3.6 Nice Work If You Can Get It

Not only is the forty-hour workweek a thing of the past for most employees, more is required of workers during their hours. Higher productivity can sometimes sound easy, as if we were Jetson-like technolords, masters of our working domain, effortlessly commanding the robot servants that titter at our beckon. That’s not how it works. As we’ve seen, the benefits of technological innovation haven’t been well distributed. Instead, workers become more like the hyperconnected, superfast, always-on tools we use every day. And it’s hard to keep up with a smartphone.

Commentators and analysts who sympathize with the employer point of view, or who believe growth to be uncomplicatedly beneficial for society, are excited by gains in hourly productivity. Kalleberg gives us another way of looking at “productivity” (the term itself betrays an employer’s perspective), paying attention to the role of coercion:

To take advantage of this potential for productivity growth, however, workers must be persuaded (or coerced) to devote high levels of effort….Highly educated professionals and managers and those in full-time and traditional work situations have seen their hours increase and have had to work harder. Meanwhile, workers at lower-wage strata often have to put together two or more jobs to make a decent living.22

This is what young people are training so hard to prepare for: a working life that asks them once again to bear the costs while passing the profits up the ladder. Whether they end up on the winning or losing side of income polarization, young workers need to be prepared to work hard and often. The grand irony is that this system wouldn’t be possible without a generation of young Americans who are willing to take the costs of training upon themselves. If young people refused to pay in time, effort, and debt for our own job preparation, employers would be forced to shell out a portion of their profits to train workers in the particular skills the companies require. Instead, a competitive childhood environment that encourages each kid to “be all they can be” and “reach their potential” undermines the possibility of solidarity. As long as there’s an advantage to be had, Millennials have been taught to reach for it, because if they don’t, someone else out there will. This kind of thinking produces some real high achievers, but it also puts a generation of workers in a very bad bargaining position. If we’re built top-to-bottom to struggle against each other for the smallest of edges, to cooperate not in our collective interest but in the interests of a small class of employers—and we are—then we’re hardly equipped to protect ourselves from larger systemic abuses. In a way, we invite them, or at least pave the road.

This is how the individual pursuit of achievement and excellence—the excellence and achievement that every private, public, and domestic authority urges children toward—makes Millennials into workers who are too efficient for our own good. As it happened to Danny Dunn, the predictable consequence of increasing your ability to do work is more work. That’s what intensification is, and it’s a bummer.

So far I’ve looked at labor trends as they’ve changed the entire job market, but now I want to focus on how workers experience these shifts on different ends of polarization, as well as some labor relations that don’t fit simply in either category. Although precarity and intensification are common to both higher-and lower-income workers, that doesn’t mean I can draw any hasty equivalences. Even if good and bad jobs are both worse than they have been in important and similar ways, as we’ll see, the divisions between them—and between the lifestyles they enable—have deepened.

To get at the comparative intensity of unemployment and underemployment, we can look at other historical measures. One way the Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) database tracks the quality of unemployment is the median duration—that is, the median length of time that workers spend looking for work. From the 1970s to 2000, this measure varied cyclically between four and ten weeks, only edging above ten for seven months in the early 1980s. After the 2001 recession, the rate increased to ten before falling to eight. The 2008 recession had a more dramatic effect: In June 2010, the median length of unemployment peaked at twenty-five weeks. Since then, it has declined from this postrecession high, but the new normal (ten weeks) is off the charts compared to the twentieth century.23 And because unemployment doesn’t include so-called marginally attached workers who haven’t looked for work in the four weeks preceding the survey, we can’t be sure how many people have fallen off the statistical edge.

If Kalleberg is right and these changes are lasting instead of cyclical, then the twenty-first-century recessions represent a quantum jump in the nature of job-seeking. Electronic résumé and application tools like Craigslist and LinkedIn make it easier to apply, but they also make it easier for employers to dip into reserve pools of increasingly skilled labor. This follows a familiar pattern: If we’re getting better and more efficient at looking for jobs, that’s a good indication that we’re going to be doing a lot more of it. Like work, unemployment has intensified.

When people do find a job—if they’re lucky enough to do so—it’s less likely than ever to be full-time. In the wake of the 2008 crisis, the number of Americans working part-time jobs for specifically economic reasons doubled, to over nine million. Since then the number has adjusted downward, but five years after the peak, only half the postrecession increase had receded.24 This accords with what millions of Americans already know, and what we’ve just seen above: The lower end of job polarization is increasingly managed according to employers’ whims and immediate profit concerns. The popularity of part-time jobs makes it easier for owners to efficiently toggle their labor inputs, but being toggled along with the market makes life hard for workers who can’t rely on future income—never mind the predictable promotions and salary bumps that come with progress in a firm’s internal labor market—or nonwage benefits like health care, pensions, severance, or sick leave.

When given the choice, employers would rather pay only for the labor-time they need, rather than assuming long-term commitments to flesh-and-blood workers who might get pregnant or fall down or get sick or need to grieve a family member or maybe just become redundant or too expensive. It’s much cheaper to think of labor as a flow that can be spliced into hourly pieces to fit employer specifications, a production input like plastic or electricity, and just as subject to rationalization. (This is, of course, how accounting as a discipline and managerialism as an ideology view workers.) Having pushed so many of the training costs onto young people and their families, employers have less invested in individual employees and their continued welfare. If they didn’t invest in the workers’ human capital, firms aren’t compelled to “protect” their investments. Management of all but the most rarefied, highest-skill workers is no longer about carrots and sticks; employers can let generalized debt and the cost of living take care of the incentives. It’s a buyer’s market when it comes to labor, and they get to set the terms.

3.7 Deunionization

Employers didn’t just awake one day and decide to treat their workers worse. Capitalism encourages owners to reduce their labor costs until it becomes unprofitable. The minimum wage exists to put an extramarket basement on how low the purchasers of labor can drive the price. As Chris Rock famously put it: “Do you know what it means when someone pays you minimum wage? I would pay you less, but it’s against the law.” But the minimum wage hasn’t been the strongest bulwark against the drive to depress compensation—and not just because it has lost a quarter of its inflation-adjusted value against the Consumer Price Index since the late 1960s.25 Industrial labor unions have always attempted to counter employer interests by representing large numbers of workers together. This collective bargaining meant wages, benefits, hours, working conditions, promotions, etc., were all subject to negotiation between two parties that needed each other. If unions care about their members, and firms are compelled to care about what their unions want, then as long as their mutual dependence lasts, unionized workers can maintain some balance of power. But in the last few decades, that bit of shared leverage has largely dissolved.

According to a 2013 report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, union membership was nearly halved since the bureau began measuring in 1983. Over the three decades, the rate dropped from 20.1 percent to 11.3 percent.26 Everything in this chapter so far has to be understood in the context of massive deunionization in America. Although union membership rates have dropped for men and women over the past thirty years, they’ve fallen over three times faster for men (12.8 vs. 4.1 percent).27 The narrowing of this gap between the number of unionized men and unionized women is another component of the feminization of labor and the reduction of costs. Without collective bargaining, only the most in-demand employees have any leverage at all when it comes to determining the conditions of and compensation for their work.

There are a lot of proximate causes for deunionization: Automation displaced routine jobs, which are particularly suited for collective bargaining, since labor’s role in production is clear and individual workers’ contributions are easily compared. Because median union pay is over 20 percent higher than pay for nonunion workers, multinational firms have offshored unionized manufacturing, chasing cheaper labor from right across the border in Mexico all the way to China.28 Republicans have tried schemes at the local, state, and national levels to undermine unions for ideological and economic reasons, but also because organized labor is a power base for Democrats. Unions themselves have been forced into a defensive position, fighting for institutional survival instead of expansion. There’s also a cultural aspect: Kids trained from infancy to excel and compete to their fullest potential under all circumstances are ill-suited for traditional union tactics that sometimes require intentionally inefficient work, like the slowdown strike or work-to-rule. Instead, we’re perfect scabs, properly prepared to seize any opportunity we can.

No tendency better describes the collapse of American organized labor than the decline in strike activity. In the 1970s, there were hundreds of strikes every year with thousands of workers, but by the turn of the century, the decline in membership and antistrike legislation caused the number of actions and rate of participation to drop 95 percent each.29 A strike is how organized labor flexes its muscles; the threat that organization poses is a halt to production. Without the promise of work stoppage, union power dissipates and workers can’t possibly negotiate from a position of strength.

Muscles atrophy, and solidarity can’t be relied upon if young workers don’t learn and practice it. At last count, a negligible 4.2 percent of workers under twenty-four belonged to unions, less than one-third the rate of workers over fifty-five.30 The older you are (up until retirement age), the greater the chances you belong to a union, which indicates that current membership rates are soft and will decline fast as older laborers retire and die. It’s not just a question of access; the BLS reports that young workers are the least likely to join and pay dues when they’re hired at a unionized workplace.31 As Millennials enter the labor force, they have been structurally, legally, emotionally, culturally, and intellectually dissuaded from organizing in their own collective interest as workers. And the plan has been successful. With the number of unemployed and part-time workers, there’s no macroeconomic indication that large unions are going to regain their prominence. It looks more likely that American industrial labor unions as we’ve known them won’t survive another generation.

3.8 Just Get an Intern

Union workers symbolize the aspects of employment that are on the decline: Members tend to be male, full-time, higher-paid, and older. They embody an American social contract and a way of life that’s dying. So what is the inverse? What is the figure that represents the type of labor that’s on the rise? The unpaid intern is a relatively new kind of employee. This role combines features of low-and high-skill labor, along with the lack of compensation that befits work under the pedagogical mask. Unpaid interns are more likely to be young women and work flexible hours. Most of all, they’re unpaid. They do manual tasks like fetching coffee and making copies, as well as abstract tasks like managing social media accounts and contributing to team meetings. Interns have one leg in each side of labor polarization.

The intern category recently applied only in extraordinarily high-skill professions like medicine, where doctors train in a live workplace setting (and get paid a beginner wage from the government). In this traditional mode, newcomers are learning the ropes via trial and error, and if hospitals didn’t need a next generation of doctors, they wouldn’t be worth the trouble. The new interns, however, are more like entry-level employees whom firms have convinced most of us they don’t have to pay. Although these things are hard to measure reliably, the survey data we have suggests that half of college graduates complete an internship before they’re done.32 That’s a huge workforce; the most credible conservative numbers say that between one and two million interns offer their labor to firms every year.33 Free workers undermine the demand for entry-level workers across the board; why pay for anything if you don’t have to?

In his book Intern Nation, Ross Perlin details the explosive growth of internships, which he incisively calls “a new and distinctive form, located at the nexus of transformations in higher education and the workplace.” In his analysis of the rhetoric surrounding want ads for unpaid internships, Perlin writes that the burden of getting value out of an internship has fallen to the interns themselves. Internships are no longer by and large a means of professional reproduction; rather, they have become an easy way for employers to take a free dip in the flexible labor pool. Instead of an investment in the future, unpaid internships are extractive. As we’ve moved into a parody world where there exists such a thing as a barista internship, the idea that young and inexperienced workers are still entitled to pay has gone out of fashion. In a job market where a letter of recommendation and a line on a résumé seem so valuable, we Millennials have shown ourselves willing to trade the only things we’ve got on hand: our time, skills, and energy.

Universities have done more than their share to promote unpaid internships, with some even requiring students to complete one to graduate. Many schools offer credit for internships, treating them as if they had the educational value of a course. What this three-party relationship means is that students are paying their colleges and working for companies (or the state or nonprofits), and in return both will confirm for anyone who asks that the student indeed paid for the credits and performed the labor. Interns are like Danny Dunn, getting paid in homework stickers.

From a student’s perspective, an internship for credit, even if unpaid, is a simultaneous step toward both graduation and a job in her chosen field. At least, that’s what students have been sold—because there’s not much evidence that unpaid internships lead to favorable job outcomes. A 2013 survey by the National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE)—an organization that exists in part to promote internships—found that graduates who had completed an unpaid internship were less than 2 percent more likely to get a job offer than the control group (37 and 35.2 percent, respectively), and their median starting salary was actually lower ($35,721 versus $37,087).34 Considering those numbers, the whole sector looks like a confidence game in which young workers take the boss’s word for it that they’re not supposed to be paid yet, but if they try hard it will all work out for the best. It’s a myth that unpaid internships are a crucial step to career advancement, but as far as colleges and employers are concerned, it’s a very useful one.

Another legend surrounding unpaid internships is that the young people who do these not-quite-jobs are pampered, living on sizable grants from their parents. In popular culture, interns are the best dressed in the office, biding time while their future among the elite works itself into place. A survey by Intern Bridge—the other main research organization besides NACE that focuses on the internship market—found that lower-income students were more likely to take unpaid internships, whereas their higher-income peers were more likely to be found in the paid positions.35 Also, women were significantly more likely to take unpaid internships both compared to paid work and compared to men. The myth of the rich intern has more to do with who gets to make movies and TV shows about young people than the actual young people who do this work, but it also serves a valuable purpose in the maintenance of the status quo: If firms and society in general assume that interns are being taken care of by a nonmarket agent like their family or school, they need not trouble themselves with how their interns are getting by week to week. This further entrenches the idea among young workers that they’re not in a position from which to negotiate and that all they can do is work harder and try to ingratiate themselves with their bosses.

It’s a sign of devastated expectations and rampant misinformation that entry-level workers believe they only have the leverage to ask the powers that be to confirm their labor for the record (rather than negotiating for wages). Only a generation raised on a diet of gold stars could think that way. Virtually no employer would be willing to bring in nonemployees who lose them money, which is what they want the Department of Labor to believe they’re doing. Not in this economy, surely. As the Intern Bridge report says, “In point of fact, it is nonsensical to suggest that interns do not provide benefits to a company.”36 But that hasn’t stopped influential college presidents from trying to prolong the internship windfall for as long as possible. In 2010, after the Department of Labor sent a reminder that internships had to abide by existing employment regulations, thirteen university presidents cosigned a letter to then secretary Hilda Solis requesting that federal authorities keep their hands off.37

My fear is that the prominence of the unpaid internship isn’t the result of a regulatory oversight. Rather, this new labor regime is a natural and unavoidable outcome of a culture in which children are taught that the main objective while they’re young is to become the best job applicant they can be. Even if federal regulators came down hard on firms for minimum-wage violations, even if they pursued a massive fraud case against universities that used federal funds to pay for potentially illegal internship programs, I believe there would remain young people willing and eager to break the rules in order to sell themselves short.

As long as American childhood is a high-stakes merit-badge contest, there will be kids who will do whatever they must to fill out their résumé. Like Tom Sawyer talking his friends into paying him and doing his chore, employers and colleges have convinced young people that work itself is a privilege of which they are probably unworthy. In fact, they say our contributions are literally worthless. As Perlin writes, “The power of offering something for free—that it breaks down barriers to entry, reaches a much wider audience, and evades formal structures such as budgets—is counterbalanced by a host of negative psychological baggage….In a society hooked on cost-benefit analyses, free is not part of the accounting; free isn’t taken seriously.”38 This belief spurs some short-term profitability, but it teaches people to be servile, anxious, and afraid. And those are not the type of people who get paid the kind of money that lasts.

3.9 Owners and Profiteers

A good way to read the cumulative effects of all these trends is to look at shifts in the accumulation of wealth by age. Income is a useful but incomplete metric for assessing how people are doing economically. As we noted earlier, income measures traditionally exclude money from government transfer programs, inherited wealth, and profits from capital gains, all of which influence people’s lived experience. Net worth, like a balance sheet, measures the difference between a household’s liquid or saleable assets and its liabilities. This metric gives us a good idea where the proceeds from increased productivity have found their home.

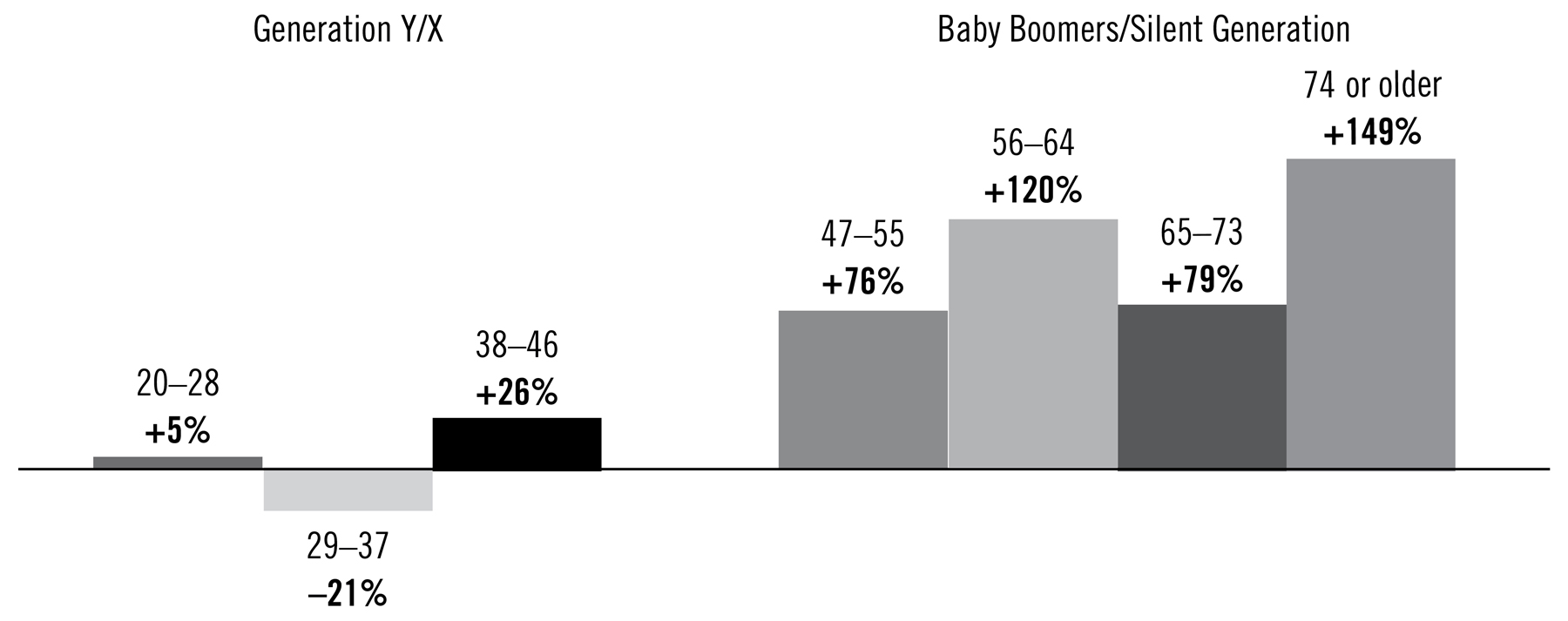

Of course, older households are going to have comparatively more time to stack up assets and pay down debts, so a straight-up comparison between older and younger workers doesn’t tell us much. But by looking at the historical trends, we can see structural changes to the economy over the time in question start to manifest. In 2013, a group of researchers from the Urban Institute compared changes in average net worth by age between 1983 and 2010 as reported in the Survey of Consumer Finances.39 What they found was startling: Older households have grown their wealth significantly over the time in question, while younger households have seen much smaller or even negative gains. Households at the most aged level (seventy-four and over) increased their wealth by nearly 150 percent in this twenty-seven-year period, and those between fifty-six and sixty-four saw a 120 percent gain. Other older households (forty-seven to fifty-five and sixty-five to seventy-three) had 76 and 79 percent increases, respectively. Below forty-seven, the surges start to dwindle. Households headed by Americans between the ages of thirty-eight and forty-six saw a 26 percent jump, while those twenty-nine to thirty-seven endured a 21 percent decrease. For those in their twenties, there was a modest boost of 5 percent. This marks a meaningful change in the progression of American generations: “As a society gets wealthier, children are typically richer than their parents, and each generation is typically wealthier than the previous one,” the researchers write. “But younger Americans’ wealth is no longer outpacing their parents’.”40

Change in Average Household Net Worth by Age Group, 1983–2010

Americans have taken for granted that ours is a society getting wealthier and that children will out-earn their parents, and that has been a fair assumption. Economists use the term “absolute income mobility” to describe the relation of one generation’s earning to another’s, and a group at the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) compared the scores for Americans born in 1940 and 1980, to check on the mobility of mobility. It’s no wonder we’re used to feeling like things are going to get better: In the 1940 cohort, approximately 90 percent out-earned their parents. But for Millennials, the mobility number is down to 50 percent: It’s a coin-flip whether or not we’ll out-earn Mom and Dad.41 The analysts conclude that the drastic change comes from the shifting, increasingly unequal distribution of GDP, rather than a lack of growth itself. The American dream isn’t fading (as the title of the NBER paper says), it’s being hoarded.

Still, when it comes to wealth, comparatively gradual income shifts have mattered less than the dramatic changes in debt and housing prices. Mortgage debt tends to peak when borrowers are in their late thirties, and these are the households who got caught without a seat when the subprime music stopped. Since the crisis, however, American consumers have slowed down their use of credit, deciding of their own volition to deleverage themselves. Research economists Yuliya Demyanyk and Matthew Koepke at the Cleveland Fed studied a number of trends to see if the decline in consumer credit was due to banks’ unwillingness to lend or consumers’ unwillingness to borrow. After assessing the credit statistics, Demyanyk and Koepke determined that the decline was more due to consumers tightening their belts than to banks tightening lending standards.42 For the first time this century, the average consumer owns fewer than two bank cards. Although this is probably heartening to frugal-minded commentators, it also means more people are living with less.

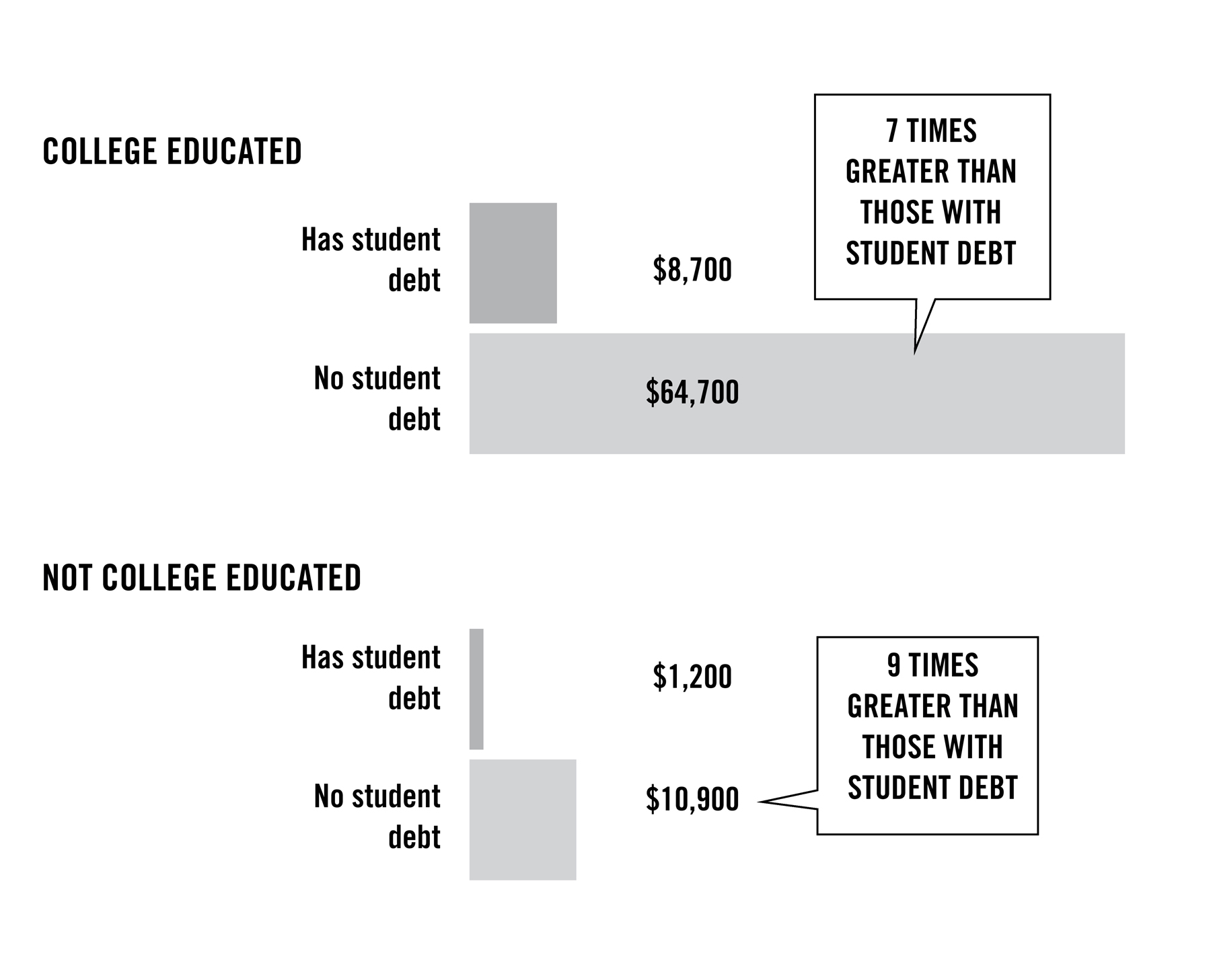

The exception to de-escalating debt, as we’ve seen, is in education. Student debt has grown completely unconnected to other forms of borrowing and people’s ability to pay. In 2014, Richard Fry of Pew Research Center looked at the same 2010 survey data as the Urban Institute study, specifically at households under forty and their education and student debt loads. What he found runs counter to the conventional wisdom about the value of a college degree.43 Fry split the households under forty twice: those with a bachelor’s degree (“college educated”) and those with outstanding student debt. The big division comes not between either of the two splits, but between one quadrant and the other three. College-educated households without student debt had a median net worth just shy of $65,000, far higher than the three other categories combined, and over seven times greater than the $8,700 median wealth for college-educated households with debt. The average wealth for households without a bachelor’s and without student debt is actually higher than that for the indebted graduates, at just under $11,000. The worst off are those without a bachelor’s but who have still racked up some debt—not uncommon considering the many Americans who enter programs but don’t finish, and the number in two-year and vocational programs. The wealth that’s supposed to come with educational debt hasn’t accrued to the tail end of Gen X yet, and it’s going to get worse.

Young Student Debtors Lag Behind in Wealth Accumulation

Median net worth of young households

Note: Young households are households with heads younger than 40. Households are characterized based on the educational attainment of the household head. “College educated” refers to those with a bachelor’s degree or more. Student debtor households have outstanding student loan balances or student loans in deferment. Net worth is the value of the household assets minus household debts.

And yet, despite all the economic instability in this young century, despite all the popped bubbles and chastened speculators, if you don’t examine the distribution, things look great in America. In March of 2014, the Wall Street Journal was able to report the headline “U.S. Household Net Worth Hits Record High” without, strictly speaking, lying.44 Increases in the value of stocks, bonds, and homes have driven the recovery from the 2008 crisis, even though the recovery has been unevenly enjoyed. The net acquisition of financial assets nearly tripled between 2009 and the second quarter of 2014, from $666.7 billion to $1.935 trillion.45 Rental income has grown almost as fast, from $333.7 billion to $636.4 billion.46 Meanwhile, employee compensation has grown 9.5 percent between 2008 and 2013,47 only a fraction of the 50 percent swell in corporate profits between 2009 and the second quarter of 2014.48 Postcrisis America has been a great place to own things and a really bad place not to.

What we see in the wealth numbers is not a clean-cut case of intergenerational robbery, or at least not just that. A quadrant of young households in the Pew data are doing quite well for themselves. Over the past generation, the economy has bent heavily in the owners’ direction, like a pinball machine on tilt. The uneven impact of the 2008 crisis could have led to reevaluation of these trends. But it didn’t. Instead, the owners of land, real estate, stocks, and bonds have increased their rate of gain at the expense of everyone else. This also means that the path from worker to owner gets steeper and more treacherous, and since few Millennials are born with a stock portfolio, fewer of us will make it up the mountain than in past generations.

The increasing wealth division between American owners and workers gives some much-needed context for the central role competition plays in young people’s lives. With the middle hollowed out of the job market, there’s less room for people to fall short, a thinner cushion for underdeveloped ambitions and ungrasped advantages. You either become someone who’s in a position to buy stock and real estate—an ownership stake in the economy—or you work for them on their terms. It’s no wonder that, when asked in a Pew poll, 61 percent of Millennial women and 70 percent of men said they aspired to be a boss or top manager.49 But the 1 percent isn’t called that because most people can join. The majority of these would-be bosses are on a fool’s errand.

In the face of overwhelming odds and high stakes, a sufficient number of Millennials are willing to do whatever it takes to be a winner in the twenty-first-century economy. There are many more of us willing to do the work than there is space on the victors’ podium. Even at the supposed highest levels of postcollegiate achievement, the same intense pressures pit workers against each other for a few spots on top. For his book Young Money, journalist Kevin Roose spoke with entry-level finance workers about their jobs, which he turned into a medium-term longitudinal study of what life is like after you win college. The large financial institutions where Roose is looking recruit almost exclusively out of the Ivy League, but an undergraduate background in finance is not necessarily required. What they want is twenty-one-year-olds who have never lost at anything in their lives, and then they want them to compete against each other.

Finance is, at root, about making money by owning and selling the right things at the right times. In an economy that increasingly rewards owners, these ownership managers are among the best-compensated workers in the country. (I’ll get to the techies later.) But even though the job is all about risk, Roose’s investigation suggests that a thirst for adrenaline isn’t what motivates the top students at the top schools to join Goldman or Bank of America. Rather, it’s risk aversion. Roose talked to a Goldman analyst who told him about the real motivations for the recruits he sees:

Wall Street banks had made themselves the obvious destinations for students at top-tier colleges who are confused about their careers, don’t want to lock themselves into a narrow pre professional track by going to law or medical school, and are looking to put off the big decisions for two years while they figure things out. Banks, in other words, have become extremely skilled at appealing to the anxieties of overachieving young people and inserting themselves as the solution to those worries.50

Once you’re inside, the finance industry manages their domestic human capital the same way they treat human capital on the market. (Roose notes that Goldman Sachs renamed its human resources department Human Capital Management.)51 First-year financial analysts are expected to explicitly renounce any other commitments and be on call at all times. Many of the well-publicized perks of working in finance—from the gyms to free food to late-night transportation—exist to encourage employees to work longer hours. After taking into account his obscene workweek, one J.P. Morgan analyst Roose interviewed calculated his post-tax pay at $16 an hour 52—more than $5 less than the 1968 minimum wage adjusted for productivity growth.53 This yields what Roose describes as “disillusionment, depression, and feelings of worthlessness that were deeper and more foundational than simple work frustrations.”54

None of this is to say anyone should feel sorry for financiers—even junior ones—but it’s worth understanding what is really at the end of the road for Millennials who do everything right. The best the job market has to offer is a slice of the profits from driving down labor costs. One of Roose’s subjects found himself working on a deal he believed to be about rehabbing a firm, only to discover that his bosses were more interested in firing workers and auctioning equipment before selling the now “more efficient” company for a quick $50 million profit. Although they’re the natural outcomes of the wage relation, work intensification and downsizing don’t just happen by themselves. The profits have to be made, and the best of the best Millennials end up doing the analytical drudge work that makes superefficient production possible, then crying to reporters over their beers. It hardly seems worth it.

There is, eventually, a hard limit when it comes to extracting labor from workers. In 2013, a twenty-one-year-old summer intern at Merrill Lynch’s London branch named Moritz Erhardt died after working until six in the morning three nights in a row.55 (This isn’t particularly uncommon—Roose describes the “banker’s 9-to-5” as 9 a.m. until 5 a.m. the next day.) Eventually, if you work someone harder and harder without any regard for how they get themselves from one day to the next, they will quit or die. Like golden retrievers who don’t know how to stop chasing a ball, Millennials are so well trained to excel and follow directions that many of us don’t know how to separate our own interests from a boss’s or a company’s.