The decades-long effort to sequence the human genome changed the way many people talk about human biology, disease, and difference. Genes were hailed as the ultimate medical solution to every kind of disease and unwanted behavioral condition. Popular media stories of criminals released from death row, genetic tests to find one’s “true” ancestors, and science fiction movies all heralded a new genomic age.1 It was the promise of the genomic revolution that led to the creation of the Human Genome Project. Formally launched in 1990 with funding from the Department of Energy and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the costs to sequentially detail the patterns of proteins that DNA on each chromosome is reported to be more than $3 billion in public investment and likely much more from the private sector. While the advances in genomic sciences changed the way we talk about human difference, biology, and disease, its effect on the way we actually think about and act upon human difference remains to be seen. The ramifications of the use of genetics to think, talk, and solve the problems of type 2 diabetes, and of ethnoracial2 differences in health more generally, is the subject of this book.

In many respects this book anticipates the end of the genomic era at precisely the moment many researchers have convinced funders such as the NIH and countless investors that the future of biomedicine rests squarely in genomic sciences. At the turn of the last century, interdisciplinary teams in universities and corporations were repackaging themselves to accommodate the post-genomic speculative promises for the mass genetic data sets soon to be at their avail in huge depositories called biobanks. Mapping new chromosomal regions, characterizing new informative bits of proteins called markers, and populating DNA data banks were the necessary preconditions for finding the genetic contributions for such common diseases as diabetes, asthma, heart disease, addiction, and hypertension. Researchers worldwide busied themselves with these foundational practices while finding susceptibility genes filled the research and popular cultural imaginaries as the most important and imminently doable task at hand.

The end of the genomic era has not arrived, however. The former director of the Human Genome Project, Francis Collins, has been appointed by President Obama as director of the NIH, and researchers daily report findings of suspected genetic contributions to this or that embodied or behavioral phenomenon. Little debate accompanies such findings; interdisciplinarity ends where epistemological interventions might begin. The new foundational practices of tooling-up labs and research networks have moved up the physiologic food chain to now include traits such as skin color and brain size and behaviors such as delinquency, gang membership, weapon use, arson, even bad driving, as well as a host of predisease bioindicators—those physiological conditions that are clinically implicated in a range of health outcomes (e.g., preterm birth, cancer survival, asthma).3 Finding markers and querying the biobank infrastructures are now pointedly pressed into service in the enduring push to keep genomics at the cutting edge of biomedical research. These practices, while knowledge based, are not based on knowledge per se. They constitute what Greenhalgh describes as the problematization, assemblage, and micropolitics of science making through which we can trace “the political careers of scientific ‘truths’ and discover how science has gained its incredible power in the political and social realms.”4 This book examines the politics of knowledge claims about diabetes.

As it pertains to the human genome, politics and economics have modulated the genomic amplitude, tempered the optimism of most, and tested the patience of many. Anticipating the completion of the human genome, the NIH published its Roadmap in 2002, which charts the vision of the future of genomic sciences. This future, argue its authors, requires approaches that span the many divisions of the NIH and seeks public buy-in and thus acceptance from the lay (nonscientific) community. In this way, the Roadmap argues, we will be able to take full advantage of the genomic revolution, transform research practices, and accelerate clinical application. A year after the Roadmap was published, Francis Collins, then director of the National Human Genome Research Institute, published a vision of the role of genome research that shifted the focus to improving human health while also acknowledging the social and ethical frontiers the genomic era creates.5 Expanding, as these official positions did, from the aims of finding the structure and function of the human genome to addressing cross-cutting interdisciplinary challenges with both clinical applications and social implications signaled that the human genome was not solely a basic scientific pursuit. It has application.

This bicameral basic and applied dimension is what gives “New Genetics” its cultural fraction.6 New Genetics permeates our conceptions of life itself, of what it means to be a human, of who gets sick and why, and it is related to entire industrial and technoscientific apparatuses scarcely imaginable decades ago. As Palsson argues, we must “recognize the successes of the new genetics while exploring the implications of the gene centrism configured with and through them.”7 To this end, this book looks at the human genome as a cultural form of the most basic kind drawing upon—and in many ways constituting—new and old social and material orders. It is at this juncture, this confluence of basic, applied, computational, molecular, infrastructural, cultural, political, economic, and social assemblages, that I situate the story of diabetes genetic epidemiology.

I began in 1998 to investigate the work of scientists searching for the genes that “cause” type 2 diabetes.8 Diabetes is not one disease but many. More than 90 percent of all diabetics have type 2 diabetes, which is characterized by elevated blood glucose triggered by poor insulin production or insulin resistance in skeletal muscle and lipid tissue. Type 2 diabetes is also known as non-insulin-dependent diabetes because, unlike the rarer form of the disease, people with type 2 diabetes produce insulin and therefore seldom need therapeutic insulin at the initial onset of disease. Type 2 diabetes, hereafter referred to simply as diabetes, is, like heart disease, hypertension, and asthma, referred to as a complex disease because its putative risks lie in both environmental and biological domains. That is, diabetes is caused by an as yet unknown combination of factors that include lifestyle, diet, physical activity, and an array of physiological triggers, among which it is presumed that genetic susceptibility plays a part.

Diabetes is the seventh leading cause of death in the United States and is frequently referred to as a public health crisis in the government, academic, and popular press.9 The World Health Organization has called diabetes an emerging epidemic with more than 16 million people affected in the United States and hundreds of millions more in the rapidly urbanizing Southern Hemisphere and China. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), by 2025, 270 million people worldwide will have diabetes. If the current trend continues, over the next 50 years, one out of three Americans will develop diabetes in their lifetime. For the general population, one in three represents a 165 percent increase by the year 2050. Since 1987, the death rate ascribable to diabetes has increased by 45 percent, whereas the death rates due to heart disease, stroke, and cancer have declined.

Diabetes is a peculiar disease. Its symptoms have been likened to quantitative variation of normal physiology. Its causes have been attributed to genes (read errors), environment (read behaviors), and gene-environment interactions (read lifestyle, nutrition, physical activity levels, marriage practices, and ancestry). During the course of my research, not once did the living conditions for Mexicanas/os along the U.S.-Mexico border figure into a conversation about causality. Drug companies narrate diabetes as a biochemical error, and genetic epidemiologists frame the disease as a population-based syndrome. Because diabetes in indigenous populations has been criticized as a response to the onslaught of unhealthy Anglo values and lifestyles, social scientists have framed it as a disease of civilization or a disease of capitalism.10

The hallmark of the condition of diabetes is hyperglycemia, or high blood sugar, caused by the poor utilization of insulin. Insulin is a hormone released by beta cells in the islets of Langerhans of the pancreas. The hormones function to control blood sugar levels. Insulin regulates glucose transport into cells so they can produce energy or store glucose for later use. As food gets digested and transformed into simple sugars, the pancreas is stimulated to release insulin to be used by the muscles as energy, thus preventing hyperglycemia. Most people with diabetes suffer from elevated blood glucose because the insulin their pancreas produces is underutilized by their fat and muscle tissues. Diminished insulin uptake results in hyperglycemia, elevated blood glucose levels.

The pervasiveness of the rhetoric of diabetes as a public health threat is evidenced in the September 2000 issue of Newsweek magazine. The cover story, titled “An American Epidemic: Diabetes,” tells of the rise of diabetes among Americans. It featured (in the online version) a photograph of Yolanda Benitez, a middle-aged woman with diabetes. The photo shows Benitez heating a tortilla on a cast iron comal (skillet). The front-page text reads, “Something terrible was happening to Yolanda Benitez’s eyes. They were being poisoned; the fragile capillaries of the retina attacked from within and were leaking blood.” The main health concerns for people with diabetes, as the story of Benitez illustrates, are the complications. According to the CDC, diabetes is the leading cause of blindness among people between the ages of 20 and 74. In fact the CDC estimates that when the costs of diabetes complications—eye disease ($470 million), kidney failure ($842 million), and lower extremity amputations ($860 million)—are added to the costs of controlling glucose ($100 million), the expenditure for type 2 diabetes exceeds $2.7 billion annually.11

Geneticists, epidemiologists, government analysts, and journalists frame diabetes as an ethnoracial disease. In fact, it is hard to find a discussion, popular or scientific, about diabetes without a discussion of its differential impact on people of color. A publication from the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention reads:

The burden of disease is heavier among elderly Americans—more than 18 percent of adults over age 65 have diabetes—and certain racial and ethnic populations, including African Americans, Hispanics/Latinos, and American Indians and Alaska Natives. For example, American Indians and Alaska Natives are 2.8 times more likely to have diagnosed diabetes than non-Hispanic whites of similar age.12

Similarly, a grant application submitted to the U.S. Public Health Service by one scientist I worked with begins its “Background and Significance” section with the differential prevalence patterns of diabetes in populations defined with ethnoracial labels. It reads, “Type 2 diabetes has an estimated prevalence of 6–8 percent in white populations, 10–12 percent in African Americans, and 15–20 percent in Mexican Americans.” The proposal cites an array of scientific references for each population. Additionally, the Newsweek story describes Benitez as a “representative victim” of diabetes, citing the usual ethnoracial statistics, a claim that we will return to in chapter 5.

Schooled in the critique of genetic determinism, I was concerned with this scientific practice that, from the outside looking in, appeared to actively transform DNA labeled with historically specific folk taxonomies (Mexican American, Asian, European) into substances with biological significance. Through participant-observation and text-based analyses, I tracked the use of race/ethnicity within an international consortium of scientists who had formed a transdisciplinary and transnational academic-, corporate-, and state-funded alliance. Some of the 33 institutional members include the University of Chicago, the University of Texas, the NIH (including Francis Collins, the director of the Human Genome Project), the American Diabetes Association [ADA], Harvard University, and GlaxoSmithKline.13

In the early stages of project development, I traveled to Mexico, Texas, and North Carolina to interview researchers who were in one way or another interested in an aspect of diabetes. In Mexico, I spoke with a population geneticist at the Instituto Nacional de Nutrición, Salvador Zubiran; a geneticist at the Universidad Nacional Autonomia de México; and a clinical researcher at a children’s hospital in Mexico City. The population geneticist had biologically characterized some samples used by the clinical researcher who was a coauthor with a University of Texas epidemiologist involved in a San Antonio-based family study. The transnational and cross-disciplinary collaboration of my ethnographic interlocutors figured prominently in the development of the methodological and theoretical foundations of my research. In addition to my interest in race and ethnicity, I was interested in the nature of this scientific collaboration. To understand it would require attending to the transient investigators, data sets, DNA samples, and institutional arrangements that assembled the diabetes enterprise and the locally derived social relations that brought forth the cultural form at each collaborative node. Additionally, I set about to characterize the breadth and depth of scientific cooperation and how such communal research practices could thrive amid the hype about intellectual property.

Analytically, the type 2 diabetes enterprise is productively understood as an anthropological problem of the first order. In saying this, I am influenced by Ong and Collier’s definition of anthropological problems as those involving a confluence of “forms and values that bear directly upon individual and collective existence through which technological, political, ethical reflection and intervention occur.”14 This is Anthropological with a capital A, that which Rabinow calls appropriately, anthropos.15 Diabetes is not merely to be understood as an object of human sciences through which we come to locate an instance of population governance.16 Rather it is also a cultural form that requires attention to humans as both biological and social beings. By confluence, I think not of a noun, a mixture, but a verb, a process of merging together old and new ways of conceiving illness, disease, human variation, biology, society, knowledge, and so on.

Take, for example, diabetes scientists’ use of human DNA. Intervening into the value-laden and context-bound configurations of human bodies, the type 2 diabetes enterprise enlists research subjects by virtue of their perceived membership in ethnic groups. Mexicano/as, blacks, Asians, and a host of other groups were enrolled as if these groups made sense sui generis. I was curious as to why the race or ethnicity of a population was important for research into disease given the conviction within anthropology that race is a social construct.

I demonstrate in the pages that follow that my interests in the diabetes enterprise at times sharpened and at others blurred as the “conversation” I was having required me to reflect anew upon my understandings. For example, I began by wondering how race could be biologically meaningful if it is a social construct. I ended, through a series of dialogical conversations,17 with a clearer explanation of the meanings of “race” and of “social” and of “constructions” that emerge within this technoscientific cultural form. In this way, this project befits Annelise Riles’s conceptualization of fieldwork as “an act of circling back, of engaging intellectual and ethical origins from the point of view of problems that now begin elsewhere.18 That is, the dialogics of my ethnographic practice required me to return to what I had thought I understood. More important, however, as my understanding changed and I came to understand the logics of pragmatism, of antipolitics, of value generation, of service to humanity, the problems of race and diabetes and genetics came to be imaginable as mere markers of larger cultural assemblages with histories and trajectories well beyond my field site and interlocutors.

The problems of diabetes science certainly do not originate in the social worlds of diabetes genetic epidemiology. The disease, and its attendant medical-scientific enterprise are co-configured by the context of their production.19 The idiom of co-configuration parallels Jasanoff’s idiom of coproduction in several important ways. First, diabetes as a material and semiotic assemblage is conceptualized as irreducible to either the material or the semiotic. As Jasanoff remarks, “The co-productionist idiom stresses the constant interplay of the cognitive, the material, the social and the normative.”20 Second, the diabetes genetic enterprise as a technoscientific formation is unpacked as a means through which researchers order knowledge about a chronic epidemiological problem, while at the same time ordering Anglo-Mexicano relations. Jasanoff keenly observes of the interplay of society and science, “Science and technology operate, in short, as political agents.”21 In the coproductionist vein, then, this book demonstrates the means through which a technoscientific project co-configures disease, populations of affected groups, and social orders more broadly. However, I do not adopt Jasanoff’s idiom of coproduction wholesale.

This book demonstrates that something unique occurs when we examine the embodied inflections of a natural or cultural assemblage such as “the Mexican diabetic,” in which the materiality and meanings of the ethnic body and diabetes are freighted with structural violence and inequality. While I share Jasanoff’s resistance to a reductionist social science that finds reproductive social forces in every (scientific) claim or artifact, the case of the “Mexican diabetic” in this postgenomic moment articulates squarely with the racially structured social formations that co-configure well-worn relations of domination and subordination.22 Far from a coproductionist account of a technoscientific ordering that rejects “a priori demarcations,”23 the diabetes enterprise, it will be shown, asserts its recombinatory force in the midst of incredible social inequalities. Thus the diabetes enterprise must be unpacked for its ideological work, which at times reinforces and at others resists the reproductive articulations of racial domination. In other words, the diabetes enterprise does reproduce social forces but not unidirectionally or in isolation of the context of its production. The practices that co-configure Mexicanos as diabetic, type 2 diabetes as an inherited condition, and diabetes science as delinked from the sociohistorical orderings of the U.S.-Mexico border are the site of the articulation between racially structured social formations and science and technology. The challenge before me is to account for pronounced structural inequalities within the co-configurations without sullying our understanding of the operations of nature and culture within these same co-configurations. Such is my hope for this book.

In many ways, the diabetes research enterprise is a product of the promises and perils associated with the height of the human genome project, the speculative futures of biotech and other markets, the historic demographic and geopolitical shifts in the United States and Europe that enabled and required frequent contact—and often conflict—between ethnically diverse peoples. The question becomes, What role does the diabetes genetic enterprise play in this constitutive process today and can we learn anything new about the problems of race in science and the broader sociocultural forces through an ethnographic engagement with this scientific enterprise? At an even finer resolution, what happens to the semiotic status of the materials (genes, blood samples, DNA donors) when they become the building blocks of a technoscientific enterprise? And, further, in what ways do these artifacts themselves inflect the social worlds out of which they were fashioned?

This book presents a more comprehensive and complex presentation of my questions and conclusions than I have heretofore been able to discuss with those with whom I studied. In that, it is still conventionally one sided and unavoidably at times presentist if not disciplinist in it representative prejudices.24 That is, it is my account of events and their meanings. Still, it is my hope that this book illustrates the important sociocultural work that diabetes scientists carry out in the name of finding the genetic bases of disease. I hope also that it reconfigures anthropological problems as neither utilitarian puzzles that our analyses can piece together nor as enactment of the revelatory moment of discursive emergence—modes of analysis that have been attributed to Dewey and Foucault, respectively.25 And both the puzzle solved and the revelation fall short of capturing the entangled contingencies of anthropology’s problems when we honestly acknowledge our historical and institutional emplacement within the contesting apparatuses of knowing and versions of making and understanding human beings and our world.26 This ethnographic investigation of diabetes genetic epidemiology, which occurred in the twilight of the completion of the human genome, offers just such problems.

In 1993, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) launched the GENNID study. The acronym GENNID stands for the Genetics of Non-Insulin Dependent Diabetes. The GENNID study aims to acquire, test, store, and analyze blood samples from “African American, Japanese American, Hispanic and non-Hispanic white” families. At the time, the GENNID study was predominantly a DNA-collection project. Acquisition centers were set up in university hospitals throughout the United States and were organized by folk taxonomies of ethnicity and race. For example, white samples were gathered in Utah and St. Louis, African American samples in Arkansas and Chicago, Hispanic samples in Texas, and so on. By 1998, more than twelve hundred individuals from 220 families had contributed DNA to the study. The ADA’s Web site directs interested researchers to an online catalogue of these samples.27 Following the link takes one to the Coriel Cell Repository. Coriel started in 1953 as a public nonprofit clearinghouse and storage facility (biobank) for a variety of biological samples and cell cultures. DNA samples were added later. The catalogue includes a reference population and various human variation panels along with their respective price tags. The GENNID samples are not publicly available, however. To access these requires an NIH grant or an arrangement with the ADA.

A few years after the GENNID study began, a consortium of clinical epidemiologists, geneticists, statisticians, and molecular biologists working on the genetics of type 2 diabetes formed an informal alliance to analyze the growing body of DNA samples acquired from diabetic individuals and their families. It was the height of the Human Genome Project, and the organizers of the alliance anticipated the next stage in genetics-based research: making sense of the human genome for disease research. It was a forward-thinking approach. Finding the genetic contribution to chronic disease such as type 2 diabetes would be an intellectual and financial gold mine. The alliance, which soon became the International Diabetes Genetic Analyses Consortium, was formed because each researcher realized that his or her few samples could never reach the statistical significance required for genetic analyses of a complex condition like diabetes. Several consortium members remarked, “Everyone had to fail a few times before coming to see the importance of joining the consortium.” Herein, I refer to the “diabetes consortium” as a constellation of people, technology, tools, and biological and chemical materials involved in the production, circulation, and consumption of diabetes knowledges. This constellation of human and nonhumans will hereafter be referred to as key actors, or actants, in the making of diabetes knowledges in this postgenomic era.28 I refer to the “diabetes enterprise” as a broader and even more heterogeneous constellation of actants involved in diabetes research and product development. In short, the consortium involves knowledge while the enterprise involves products, potential or realized, that the knowledge has in some way enabled.

The research for this book is anchored within a subset cluster of the consortium consisting of scientists from the University of Chicago in collaboration with the University of Texas Health Sciences. The head of the analysis team and arguably the coordinator of the consortium is at Chicago and the director of the sampling operation for the principle data set is in Texas. I interviewed and observed these and other consortium scientists in their places of work, at scientific meetings, and during their collective conversations about the power of their data sets and experimental results. Inspired by actor network theory, I follow DNA samples analytically and physically as they are drawn from a donor’s body and processed along the pathways of scientific research. The latter, the following of DNA samples and the sociocultural formations they enable, is the central organizing trope of this book.

I found the consortium by following the GENNID samples from the ADA to the pharmaceutical giant then called Glaxo Wellcome. The company’s researchers partner with academic and clinical researchers because Glaxo does not have access to diabetic patients. To identify drug targets, Glaxo acquires samples and conducts genomic scans and linkage analyses to help its partners identify potential genetic causes for disease. In fact, the populations drive the partnerships. Glaxo, for example, was allowed to join the consortium because of its contract with the ADA to genotype and analyze the GENNID data. As the head of the Department of Human Genetics at Glaxo’s U.S. headquarters told me, “You can’t do genetics without family materials.” The relationship between populations and partnerships will be explored in detail in chapter 4.

Over a period of 21 months of field research from 1998 to 2000, I conducted research at the University of Chicago School of Medicine, at scientific meetings and workshops, and at a genetic epidemiology field office on the U.S.-Mexico border. Following a collaborative pathway extending out of the Chicago laboratories, I also visited the labs and research field sites of collaborators in the United Kingdom. Blending empirical research methodology from anthropology and the social studies of science, I followed a cluster of researchers in their labs, field offices, conferences, and other venues of knowledge production. I physically followed DNA data sets through the pathways of research in Mexico, Texas, and Chicago. As will be shown in the chapters that follow, my method of following blood samples required that I accompany research field workers on home visits, to places of work, and anywhere a sample donor was to be sampled. I followed donors as they worked their way through the field office research stations, then followed the vials of their blood to the field office laboratory. I then tracked the samples as they were shipped to collaborators and moved back and forth between the places that the sample had occupied, from Chicago to Texas and to the United Kingdom.

I observed more than 80 formal and informal meetings between collaborating investigators. I listened to conversations, both formal and casual, noted the population labels in use, and documented other discussions about population DNA, data sets, and collaboration. This included conversations in phone calls, impromptu meetings between colleagues, formal journal club and lecture presentations, lunch conversations, corridor talk, bench banter, one-on-one and small group meetings, consortium meetings, meetings with guest lecturers, and between research participants and research field workers. Additionally, I conducted more than 20 interviews with diabetes researchers from public, private, and corporate institutions29 and attended five national scientific conferences.30

Further, I analyzed manuscripts, conference presentations, journal club reports, grant proposals, laboratory materials, newspaper articles, and drug company promotional materials to document the ways population labels are codified in writing for an array of audiences. Together, these methods help produce an understanding of how race and ethnicity, two social constructs with complicated scientific registers, are constituent elements in the configuration of biogenetic studies and explanations of a chronic disease like diabetes. In fact, in the conclusion of this book, I show that race and ethnicity in technoscientific use are reconfigured into “bioethnicity,” which is a hybrid concept that attains meaning through the confluence of natures and cultures.31 Further, this project elaborates the empirical claims that scientific practices shape and are shaped by the social context of their production and explains the role of genetic research in the persistent use of race to divide populations in society at large.

Taking as its main problem the axiomatic (non)existence of distinct human racial groups and the heterogeneous meanings of race, this book explains how the social constructs of human variation (white, Mexican, African American, etc.) inform the work of scientists looking for genetic susceptibilities to type 2 diabetes. Diabetes affects ethnic groups disproportionately. For decades, biomedical researchers have collected demographic and genetic information taken from racialized populations. In this book, I focus on the use of information and material taken from Mexicans and Mexican Americans specifically. The use of DNA from other groups also informs the work of researchers, professionals, and others who are interested in postgenomic diabetes. However, the arguments put forth here centrally revolve around the principal data set taken from the U.S.-Mexico border.

Placing DNA acquisition within the sociohistorical context of the U.S.-Mexico border, the processes and products of genetic epidemiological research can be understood as founded upon long-standing racialized social and economic inequalities. Yet, this project does not advance new theories or instances of overtly racist science. On the contrary, the type 2 diabetes genetic epidemiological enterprise—hereafter simply the diabetes enterprise—illustrates how the science of diabetes and social inequality are co-configured in spite of the acts of socially responsible scientists. For this project, I foreground the connections between medical science, a highly codified and privileged social practice, and the larger social forces that link political economy with race and ethnicity and, to a degree, gender. Further, under the persistent history of violent conflict, exclusion, enmity, and threat, Mexicanos/as on the U.S.-Mexico border who participate in genetic research fulfill an embodied role as racialized objects of research in a manner wholly consistent with such histories.

Understood in this context, the case of the diabetes enterprise demonstrates that DNA donors serve as global human capital for genetics-based medical research. The state and academe are revealed as privileged domains of sociocultural production that promote the generation of value for some and not others. Yet I have worked to ground the contributions of state and academic institutions by presenting how the work that emanates from a university is inseparable from the lives of the actors who operate these institutions. Furthermore, as intended beneficiaries and necessary actors within the pathways of research, DNA donors become transformed into transnational protogenetic subjects of state-capital interpellation. Readers interested in the use of human subjects will learn that in this enterprise, donor populations and their DNA become silenced commodities through the quantitative SNP-based genetic research practices. Donors’ samples are part of the larger reworking of “the biological” through regimes of exchange and ultimate profitability. Further, I came to appreciate that scientists do not unconsciously re-create racial typologies, but instead carefully press the social formations of ethnic identity into the service of the biogenetic research enterprise. As a consequence, diabetes research conflates the descriptions of affected populations with the attributes of those populations, thus pathologizing the ethnicity of DNA donors.

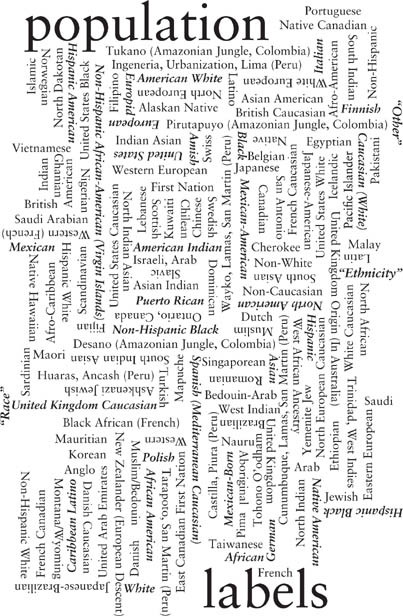

I begin with an outline of the problem of population labels. This is intended to introduce the reader to issues addressed in detail in the chapters that follow.

At its most rudimentary, this project seeks to answer the following question: How do diabetes researchers resurrect empirically defunct biological separations between populations? Does the use of Mexicano/a DNA in biogenetic research convert ethnicity into biological race? The answer lies in the difference between ethnicity and race. If the labels do not reference race, a fictive biological construct, then they must refer to ethnicity. Ethnicity is not discernable at the level of the phenotype—visible empirical types, presumed to be an expression of underlying genetics. This is because ones’ ethnicity is a complex of ascriptive and descriptive elements derived from geographic, political, historical, and socioeconomic factors. The differences between “white” and “Hispanic white” or “Latino” and “Mexican” are just two examples. The fundamentally social and historical nature of ethnicity is all the more apparent in labels like Islamic, Black Arab, American, non-Hispanic African American, and Japanese Brazilian, to name a few appearing in research abstracts. Clearly these are not biological nomenclatures in any simple sense. But the race-and-no-race debates deserve a closer examination, for they orient much of this book.

Race, some have argued, is an unstable category subject to contestation.32 Race cannot be understood as a free-standing metalinguistic taxonomic system because it is always mediated through human actors that are caught up in discourses of social location, identity, class, nation, culture, science, sexuality, and nature-biology. Yet when the biology of human variation is at issue, the discussion often gets simplified as an either/or debate. On the one hand, there are those who argue that distinct biological racial groups do not exist at all.33 Biological anthropologist Jon Marks writes:

Biological variation exists within the human species, and some of it is structured geographically. But this component of our biological variation is (1) very small relative to the total and (2.) not patterned in such a way as to permit the formalization of a reasonably small number of natural “races.” To the extent that we popularly identify such clusters, they are the result of cultural impositions of meaningful distinctions on nature, a classically anthropological example of a “folk taxonomy.”34

These researchers argue that there is no biological justification for racial groupings. They draw upon decades of research to note that most variation, approximately 95 percent, exists within so-called racial groups, that racial groups are not biological clusters, and that biological variation is a function of the evolutionary effects of geographic distance.

Though race has been a contested topic for decades, this most recent debate can be linked to the emergence of the Human Genome Project. In 1990 the United States Human Genome Project began the coordinated efforts to map and sequence the human genome. Among the assemblage of scholars involved in launching this effort was a working group charged with evaluating the ethical, legal, and social implications (ELSI) of the project. In 1996, seven years after the project began, this advisory group was the only group whose work to initiate the project was not complete.35 Sociologist Troy Duster, then chair of the group and the leading critic of “race” in medicine, explained to a national blue ribbon panel that the group’s charge was as pertinent as ever because “as genetic discoveries are made, they affect people of varying social positions, cultures, religions and genders differently.”36 The group would be needed in perpetuity, he explained, because it was the only entity able to evaluate the effect of genetic advances on groups rather than on individuals or individual bodies.

The distinction between the consequences for human groups rather than individuals is central to the cultural work of the diabetes enterprise and of this project. In this vein, the effect (good or bad) of genetic advances on an individual diabetic is a different set of issues from the ways categories of diabetic groups (e.g., Mexican diabetics) are effected. It is understandable, then, that issues involving groups defined by such labels as “Black, Native American, Asian, Mexican” would be one of the most salient themes in determining the social, legal, and ethical implications of the Human Genome Project. The ELSI working group remains to this day, and a portion of the genome project’s research budget is devoted to the group’s original charge.

That charge addresses a long-standing debate in medicine, public health, epidemiology, and the social sciences that calls into question the dubious applicability of racial groupings in studies of health outcomes, interventions, and disease etiologies.37 For example, Duster’s work documented the ways that the genetics of sickle-cell anemia led to the pathologization of African Americans.38 He illustrated how public health campaigns that encouraged African Americans to get screened for the disease in effect curbed African American birthrates.

Other studies critiqued the labels used in public health research, the discordance between biology and race, and unequal treatments based upon race and sex. For example, R. Hahn, Mulinare, and Teutsch examined infant mortality in the United States between 1983 and 1985 and found highly inconsistent coding of race and ethnicity of infants at birth and death.39 Their research sheds doubt on all racial and ethnic labeling in medical research. A subsequent national study of funeral directors found similar taxonomic instabilities.40 Related problems for forensic identification have been identified by Goodman.41 A study by Schulman and colleagues demonstrated that the race and sex of a patient influenced the rates at which physicians referred individuals for cardiac catheterization.42 This landmark study confirmed that race and sex operated independently of differences in the clinical presentation of the patients.43 Similarly, a report issued in March 2002 by the National Academies of Science, Institute of Medicine, reviewed more than one hundred studies and reaffirmed these patterns in health care.44 The report found that minorities, irrespective of access, education, and income, were discriminated against in health care.

Since 2000, there has been a steady stream of editorials and special commentaries reiterating that race is a social construct and not a biologically meaningful taxonomic system. In various ways and from an array of biomedical or other academic disciplines, authors warn against the improper use of race in research or clinical practice.45 Parts of the debate have spilled onto the pages of the New York Times. Psychiatrist Sally Satel, for example, boldly proclaimed in the Sunday Times Magazine, “I Am a Racially Profiling Doctor” (May 5, 2002). At the end of the first paragraph she writes, “When it comes to practicing medicine, stereotyping often works.” Satel is critical of the no-race position because in her practice and among her colleagues, race (defined as genetic differences based on ancestral geography), she says, should not be ignored. Citing diagnostic anecdotes and research into variable drug efficacies by race, Satel argues that attention to racial or ethnic differences can help patients. The New York Times science reporter Nicolas Wade came to similar conclusions in his reporting on a study that supports the continuation of racial or ethnic self-identity in biomedical and genetic research.46 Citing a National Cancer Institute researcher who claims that critics are unqualified, Wade champions a study by Neil Risch and colleagues that argues that a race-neutral approach to human categorization in biomedical research is statistically less valid than racial self-identification. Wade presents the Risch study as if it were a definitive end to the no-race critique (“Race Is Seen as a Real Guide to Track Roots of Disease,” July 30, 2002).47

Reardon’s astute analysis of the Human Genome Diversity Project articulates the crux of this debate.48 That project was an attempt to collect the genomes of isolated and often indigenous peoples in an effort to preserve a genetic record of human biodiversity and thus enable an understanding of human evolution. The project died almost as soon as it began and has morphed into numerous other biobanking projects.49 In assessing the controversies that surrounded the Human Genome Diversity Project through much of the 1990s, Reardon observed that the scientific issues of human genetic differences were inextricably linked with social and ethical issues of North-South relations, colonialism, intellectual property rights, and human origin narratives of particular groups. The failure to implement the project was a result of epistemological differences between geneticists and their critics and a priori political encumbrances of human genetics research itself. Scientists argued over the appropriate and ethical units of analysis (populations, individuals, groups, bodies), while activists and community groups critiqued the assumptions that social and cultural groups could ethically or accurately map onto genetic groups in the first place.

Like the conundrum presented by the Human Genome Diversity Project, when we examine closely the development of genetic knowledge derived from epidemiological research into type 2 diabetes, the problematic ontological incongruities of race and genes come into view. That is, races are not biological categories discernable through genetic frequencies. Beyond the difficulties of navigating the socioethical alongside the scientific, as suggested by the coproduction framework,50 the ways genetics is used to explain population differences for medical purposes are at odds over what constitutes a person. On the one hand, a race-neutral perspective sees no link between a blood sample and the person from whom DNA has been extracted. There is only DNA, bits of genes, not persons. On the other hand, critics of race see people whose bodies are interpellated by a dominant ideology of genetic reductionism and groups of people whose genetic information is the telegraphic proxy for their bodies and the personification of their group. Within the Human Genome Diversity Project, Reardon describes this conflict as an understanding that “imagines a ‘population’ corded off from modernity; what makes these ‘populations’ genetically interesting is precisely what defines them as not part of modern Western social orders.”51 Key to the project and the collection of genetic materials for disease research are the presumed concordance between genes and race and, even more important, between genes and disease.52

Some scholars remain deeply skeptical of any use of social taxonomies in the biosciences. They argue against any racial or ethnic classification based on evolutionary or biological phenomena between or within populations.53 Molnar, for instance, writes in his textbook Human Variation: Races, Types, and Ethnic Groups, “I shall use, where necessary, the term race to mean a group or complex of breeding populations sharing a number of traits.”54 The no-race school of thought is also opposed to work that seeks to establish the concordance between genetic variation and racial groupings.55 Some no-race theorists charge that the use of race or racial typologies as a means to define populations is, simply, racist.56 Anthropologist Harrison defines racism as “the nexus of material relations within which social and discursive practices perpetuate oppressive power relations between populations presumed to be essentially different.”57 It is the “presumption of essential difference” and the consequences of those presumptions that are at the core of the race-no-race debate.

Genetic data affirm that neither geographic circumscription nor distinct evolutionary lineages can support population or individual taxonomies as we currently construe them.58 Further, more human variation can be found within than between geographically, linguistically, and culturally categorized groups.59 Patterns of variation do correlate with geographic distributions, but these variations do not directly correspond to U.S. racial categories. Anticipating a steady stream of spurious claims about the existence of biological race, in 1998 the American Anthropological Association commissioned a statement on race authored principally by Audrey Smedley and carefully reviewed by a working group of distinguished anthropologists.60 The American Anthropological Association Executive Board adopted the position that “most physical variation, about 94 percent, lies within so-called racial groups.” In the AAA statement, the authors argue that biological indices cannot be used to differentiate human groups labeled with conventional taxonomies of race because race is fundamentally an ideology about human differences. The statement argues that medical research derived from such groups thus inaccurately portrays biological differences between peoples.

At first glance, diabetes researchers seem to be the perfect example of the inaccurate use of racial taxonomies in biomedical research. An example will illustrate. The premier venue for presenting research findings for diabetes is the American Diabetes Association Scientific Sessions. The 1998, 1999, and 2000 ADA’s Scientific Sessions Abstract Books parsed research according to 23 distinct investigative areas. The areas garnering the most research attention at the meetings include, in order, metabolism, clinical diabetes, macrovascular complications, insulin action, immunology, islet biology, genetics, and epidemiology. On average, the meetings publish nineteen hundred abstracts each year with posters representing more than half of all reports. Oral presentations constitute 16 percent of abstracts, with reports of research published only for the abstracts books accounting for the remaining 31 percent.

An analysis of the abstracts indicates that the use of ethnoracially labeled groups in diabetes research is on the rise. Between 1998 and 2000, the different kinds of population labels used by researchers jumped 17 percent, from 153 to 179 distinct ethnoracial labels. During this same period, there was a 60 percent increase in the overall use of data with ethnoracial labels, from 191 uses to 305. The greatest increase in ethnoracially labeled populations occurred among geneticists whose use of such labels jumped 60 percent, followed by epidemiologists whose use jumped 30 percent over the three years surveyed. And even though type 2 diabetes researchers deploy ethnoracial labels approximately four times as often as those conducting research on type 1, ethnoracial labels frequently appear in complications research, which crosses both diabetes domains. The trend as indicated in research abstracts suggests that at the very moment “race” is pronounced scientifically dead, diabetes researchers increasingly use population-based specificity to advance their research agendas.

Admittedly, race and ethnicity present a conundrum for medical researchers. On the one hand, since conservatively 96–99 percent of human genetic material is common to all human beings, there is minimal biological basis for parsing populations by genetic differences. On the other hand, there are different frequencies in the distributions of genetic material that some researchers believe may prove important in finding genetic contributions to diabetes and other complex diseases, frequencies in which leading researchers claim ethnic membership plays an important role. The pertinent question is how can the two propositions be explained without resorting to academic one-upmanship, or by simply amplifying old arguments in increasingly dismissive or inflammatory language?

For this project, the question is not whether population-based data is informative, but rather, informative of what? For some kinds of research, population specificity is explained as a way to control for heterogeneous research variables. For genetics, for example, research protocols based on the fine-grained single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP; see the glossary) require population specificity to help reduce the “noise” in their data. In other words, the reduction in gene variants supposedly afforded by a carefully selected group of human subjects significantly shrinks the size of the haystack through which researchers must sift in looking for a needle.61 Finding a genetic component to type 2 diabetes, for example, facilitates the more difficult task of identifying physiological triggers and pathways by localizing molecules of interest.

There are related advantages afforded by population-based research in epidemiology, investigations of patient or practitioner behavior, and analyses of health care delivery. For example, collecting ethnic-specific data can help document health disparities, practitioner biases, or unequal access to health care.62 It is less clear, however, that the use of ethnoracial labels is helpful in clinical trials, treatment protocols, and non-epidemiological research into complications.

The labels used by diabetes researchers reveal the profoundly social nature of population identifiers. For example, in the more than 460 ADA research abstracts analyzed, there are seven labels for African Americans, including Afro-American, non-Hispanic black, black, and non-Hispanic African American. For Latinos there are eight labels, including Latin, Latino, Mexican American, and Mexican. However, most interesting anthropologically are the increases in the frequency and the breadth of monikers used to describe so-called white people. In 1998 there were only two uses of the label “Caucasian (white)”; by 2000 there were 31. The current range of ethnic labels for people of northern European ancestry is quite diverse, including white, British Caucasian, Hispanic white, North American, Western, and a nonstatistical reference to a population labeled simply “United States.” In all, there are at least 30 different population labels that could fit in the “white” category. Continents, nations, and religions are also represented including Jewish, Islamic, Muslim, African, Asian, Amish, French, German, Japanese, and Europid. Based upon the classificatory moving targets represented in diabetes research abstracts, it is clear that diabetes researchers’ labels are fundamentally social constructs founded upon social history, geopolitical boundaries, or census categories.

FIGURE 1. Complete list of population labels used in ADA abstracts, 1998–2000.

Notably, the journal Nature Genetics banned the use of population labels on its pages unless the science requires it. In an editorial the journal notes, “Race might be a proxy for discriminatory experiences, diet or other environmental factors.”63 But to conduct research designed to exploit the purported genetic differences between populations identified with ethnoracial labels raises a host of ethical questions that go beyond questions of scientific accuracy.

Because the production of knowledge is the object and subject of this book, it is also concerned with productively discomforting academic discourses and narratives. These include (1) theories of race, (2) theories of science and society, (3) political economy of the body and health, and (4) studies of the historical and contemporary lives of Latinos, predominantly Mexicano-identified peoples in the United States and elsewhere. It draws upon these discussions in an effort to initiate conversation between them and to thereby extend these theories in productive ways.

Critical theories of race figure heavily in the context of this project. Since Boas first problematized the relationship between one’s phenotype and one’s character by showing that the ethnological and sociological evidence did not support the prevailing assumptions of his day, social prejudices based upon biological race have been thoroughly rejected in anthropology as elsewhere.64 Still, the arguments for and against biological differences between human groups remains contested terrain. The very existence of biological race has surfaced as a contested issue again and again.65 In genetics, Lewontin, Rose, and Kamin are arguably the most emblematic of the critiques of biological race and of reducing everything to a biological problem.66 Equally groundbreaking and productively discomfiting are philosophers of technosciences who skillfully sully the determinisms, biologisms, and geneticizations in gendered and racialized ideologies within scientific texts.67

Research that states that the characteristics of individual health are the consequence of biology are adroitly critiqued by Duster and Krieger, whose accounts, respectively, of passive eugenics and of the embodiment of inequality point to the power of the social analytic on matters of human biology and health.68 Lewontin and colleagues trace the development of race from its original concept of a different “kind” to that of a species and subspecies to subgroups defined by blood and geography or by outward appearances. Current debates, which will be examined within the context of medical and genetics research in chapter 1, have centered on the differentiation made possible through analysis of shared genetic frequencies.69 As the chapters that follow will show, the resurgence of the race debate in science and medicine are linked with the political changes of the past and present social relationships forged within, through, and among ethnic groups. What is important is not merely that race is an ever-changing political construct.70 The present case particularly, though not exclusively, highlights racial relations between Anglos and Mexicanos on the U.S.-Mexico border and beyond. The racial category called “Mexicano” is understandable as a political construct and as a biological one intimately tied to the conditions of its production, in the laboratory, and in the lives of those whose DNA makes possible the diabetes scientific enterprise.

Hannah Arendt, for example, argued that Jews and modern anti-Semitism were part of the development of the modern nation-state. Aspects of Jewish history and the societal roles of Jews over the last few centuries were important influences on the configuration of Jewishness and prejudices toward them. She argues that Jews were not scapegoats or millennial victims; most, of course, were impoverished laborers rather than cosmopolitan merchants or financiers. Yet their occupation of an “ethnic” niche in such fields made Jews easy targets as imperialism weakened the need for their financial role in service to states whose social and economic policies had worked to create Jews as a special social class. Mexicanos also occupy an ethnic niche related to the labor that they provide. However, beyond the manual labor so commonly associated with Mexicanos, the donation of DNA affords a further articulation of the role for Mexicanos as an ethnic group. It is a role, I argue here, that articulates in embodied form specific social and economic policies toward Mexicanos since before the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848.

Omi and Winant similarly argue that state apparatuses such as economic and social policies shape the racial order.71 Examining the United States from the 1960s to the 1990s, they argue that race is an autonomous historically situated ideological field of social and political organization and as such must be understood as simultaneously experiential, embodied, and structural. Several other authors have examined the ways race as a biological notion has been transformed by social factors.72 Building on these theorists, this book illustrates that the racialization of Mexicanas/os and other groups taken up in genetic epidemiological research is, indeed, part and parcel of specific historical, political, and social situations. Yet attention to the specificities of Mexicana/o DNA, DNA donation, participation in research, and rates of disease demonstrates the resilience of racialized inequality even within the social world of curing disease. Hence this case also accentuates the conundrum of technoscientific idealism when placed within a space of great conflict and oppression. To be sure, Mexicana/o racialization everywhere is intimately tied to the constructs of race, space, and legal strictures of U.S. nationalism and global capitalism.73 As such, this ethnography of the diabetes genetic enterprise is notably inspired by the everyday hopeful act of DNA collection, processing, circulation, representation, and consumption.

This book also details the problem of race and of racialization of Mexicanas/os as intimately linked to the political economy of the U.S.-Mexico border. Such structural forces as agribusiness, immigration reform, war, dispossession, drug commerce, and trade agreements and disagreements all shed light on the peculiar stranglehold on the conditions of living for Mexicanas/os along the border. To understand those conditions, which are the same forces that enable DNA acquisition, it is important to anchor the transfer of biological samples within the very same sets of systemic racialized inequalities that characterize the U.S. treatment, governmental and lay alike, of the Mexicana/o residents along the border. Racialized inequalities that are inseparable from social orders of white supremacy have historically served U.S. global capital expansionism in the region.

Current questions of race, its existence or its utility, are thus not a scientific coincidence. The findings of the genetic epidemiologists studied are herein evaluated in terms of the actors and networks involved in their production. Following Callon and Latour, this book uses actor network theory to explore the role DNA samples themselves play in the claims making processes of diabetes knowledge production.74 Callon and Latour’s notion of actor network theory proposes that only by examining the ways persons and things work together can we understand how one scientific claim gains purchase over another. No fact stands alone, they infer, because nature and society lie behind facts after they are made, never behind facts in the making. The proof of a claim’s success is its ability to enroll allies (persons and things) in its support. This is neither conspiratorial, competitive alliance making nor strategic maneuvering.75 Rather, it is an analytical approach that enables, as it has herein, the inclusion of an accounting of the human and nonhuman actors, actants, involved in the scientific process.76

In this book, it is demonstrated that the rise of the genetic epidemiological approach to type 2 diabetes is embedded in a particular social and historical context that is understandable through an assessment of the key racialized actant, DNA. Arguing that diabetes is at once a biological and a political construct, this book expands actor network theory by grounding it explicitly into the nuanced positioned interests of Mexicanas/os and those who genetically study them. I argue that (complicating Callon and Latour) nature and society are indeed behind the facts in the making, for “nature” and “society” constitute the processes and products of scientific fact. My argument is akin to that of Latour and Fujimura, who argue that a scientific claim is coproduced with the problems that initiated its examination in the first place.77 As Haraway argues of the ways race, class, sexuality, and gender are produced, “Both the facts and the witnesses are constituted in the encounters that are technoscientific practice. Both the subjects and objects of technoscience are forged and branded in the crucible of specific, located practices some of which are global in their location.”78 Hence the race debates in medicine and the ethnographic case study herein, are co-constituted with the particular technological developments of genomic science and of population genetics. In other words, this book and the range of topics it addresses must be conceptualized in tandem with the national social agendas to make the United States a color-blind society, a land of equal opportunity, and a place free of inequalities of health.79 The research for this book occurred while the U.S. Supreme Court was deliberating on an affirmative action case involving the University of Michigan, during the referendum preparations of the California Racial Privacy Initiative, and under the publicity generated by the U.S. government’s Healthy People 2000 and 2010 initiative. The aims of the latter are to end the inequalities of health burdens patterned along racial and ethnic lines.

As it pertains to health, medicine, science, and diabetes, context matters in this book. First, within these chapters, health, disease, risk, and the embodiment of ethnicity are simultaneously theorized such that both the co-constituted cultural meanings and political economies of diabetes and the U.S.-Mexico border are revealed. Scheper-Hughes and Lock argue that we must carefully scrutinize the kinds of bodies evoked in specific contexts if we are to explain how certain bodies and the “cultural sources and meanings of health and illness” are produced.80 The use by diabetes scientists of bodies identified with racialized labels thus affords an opportunity to examine the cultural work that occurs when people are treated as individuals, as diabetics, as research participants, as humans, and as Mexicanas. It also enables us to observe and assess the manner in which we are all increasingly conscripted into various pathological states.81 In the chapters that follow, there appear many instances in which the social body and the individual body are reworked through the metaphors of Mexicana/o ethnicity. A more general application of this process is advanced in the concept of bioethnicity (see chapter 5), which is the resultant product of the ways ethnicity comes to be constructed as meaningful for scientific research.

This book also converses with social epidemiological analyses that examine disease and illness within their environmental, historical, and political contexts. Pertinent to this book are those authors who argue for the inclusion of social class as a predictor of health outcomes.82 These analysts examine life expectancy as a conditional aspect of social inequality, presenting evidence that societies with the greatest income disparity also evince the greatest health disparities. Further, classic studies by epidemiologists Cooper and David and Krieger and Fee argue that cultural history, not genetic history, produces human disease.83 Cooper and David assert that making a genetic claim for ethnic differences in disease “accepts as given precisely the thing to be explained,”84 and Krieger and Fee argue that within-group comparisons would be a more informative means of examining the biological and social patterns of disease than are between-group comparisons.85 Similarly, social epidemiological analyses have critiqued the use of race in the medical and epidemiological literatures, arguing that race is both an inaccurate and misleading research variable.86 In particular, medical anthropologist Robert Hahn’s seminal analysis of racial classifications between birth and death illustrate the fluidity of folk taxonomies used for vital statistics and by extension all epidemiological research.87 Taking seriously these epidemio-logics, the case of diabetes within the Mexicana/o community exemplifies the embodiment of social inequality along the U.S.-Mexico border. The diabetes genetic enterprise thus affords a glimpse at how global technoscientific knowledge production plays out in local cultural contexts through the appropriation of embodied expressions of sociopolitical configurations.

This book is principally dedicated to an interrogation of the persistent enrollment of Mexicanas/os into genetics-based medical research practices. This project is not an ethnography about Mexicanos, however. The approach differs from the wealth of analyses of maquiladoras, of migration, Latino cultural citizenship, of frontera identity and mestizaje, of development and modernity, or of indigenismo.88 Instead, I invert the ethnographic lens to examine the people who examine and produce (biologically and socially) those who make up the largest U.S. minority group, Latinas/os.89

However, the contingency of population taxonomies presented in the chapters that follow raises questions of central importance to understanding Anglo-Mexicano relations and Mexicano experiences. In what ways do changes in agricultural production along the U.S.-Mexico border determine the availability of a class of ready-made research subjects for Anglocentric scientific enterprises?90 How can scholars account for the pernicious effects of the configurations of Mexicanas/os as an admixed biological race while preserving the cultural force of indigenismo and mestizaje inherent in critical counterdiscourses? How can the critique and understanding of capitalist hegemony be improved by an inclusion of Mexicana/o participation in capital-intensive research enterprises? And in what ways can a critique of the dominant rhetorics of Mexicano culture as fatalistic, unhealthy, superstitious, unserious (relajo) be fortified through an understanding of the embodiment of Mexicanos’ susceptibilities to disease? These are all questions that are taken up to varying degrees, implied rather than directly addressed, and thus are not the central themes of this book.

The theoretical orientations and commitments outlined above are beginning points for understanding the analyses and arguments that follow. Shared by theories of race, social and cultural analyses of science, and social epidemiologists is the critical contextualization of the phenomena of race, disease, health, and Mexicano ethnicity. There exists a common thread in these constellation of terms that are mutually composed through biological research and sociocultural conditions. It is the aim of this book to extend these theoretical conversations by offering an empirical foothold for making critical contextual connections and thereby resist the reductionist limitations of viewing this constellation of phenomena in isolation of one another or as either predominantly sociological or predominantly biological.

One set of recurrent sociocultural processes that make the case of the type 2 diabetes genetic enterprise especially vexing is the reductive and deterministic discourse of biology and genetics in particular. Simply put, the epistemic authority91 of genes and biology reconfigure all things racial, ethnic, and pathological as if they were at their most fundamental level biological or genetic phenomena. Hubbard, and Hubbard and Wald, have critiqued the field of genetics for its reductive and deterministic biases.92 In genetics, genes get endowed with tremendous and entirely unfounded powers of causation. However, Hubbard and Wald remind us that genes do not make proteins. Genes are DNA segments that, in concert with a concatenation of other metabolic apparatuses within cell formation, work to synthesize a protein.93 The consequences of reductive reasoning make highly individual (gene or organism or person) what is best understood as a dynamic interaction within a specific environment.

Hubbard and Wald demonstrate that the idea that genes cause disease not only creates a context in which solutions get constructed as technical problems rather than as social or environmental ones, but additionally places the person affected by a disease in a double bind of being both blamed for the behavior that caused the condition (e.g., sedentary lifestyle for diabetes) and deprived of agency.94 So, for example, when field office worker Judi is asked why her community has such high rates of diabetes, she remarks, “It’s in our blood.” Judi’s acceptance of a genetic (blood heredity) explanation of diabetes etiology illustrates the process of geneticization characterized by Lippman.95 Geneticization occurs when social, behavioral, and physiological problems are defined as genetic and when solutions to those problems are presumed to rely upon genetic expertise.

To be sure, the mechanisms of determinism and reductionism at work in the diabetes enterprise are similar to those that deal in representations of sex and gender and of geneticization writ large. The racially deterministic impulse states that the characteristics of the individual are a consequence of their biology. Determinism fits the prevailing social order, Lewontin and colleagues assert, because its practitioners always try to change the population to fit the environment.96 In the case of race, the differences between populations (skin color, language, or clusters of gene polymorphisms) have been used to explain criminality or intelligence without having to critically examine the organization of society itself. Like the earlier work of Boas, who tried to use the science of biological race to critique the “psychological origin or the implicit belief in the authority of tradition,”97 Lewontin and colleagues use genetic determinism to critique capitalist society for the ways certain questions about human variation are never asked.

Deterministic and reductionistic science are not unique to disease science, nor are racializing discourses. Cartmill analyzed the use of racial categories in physical anthropology from 1965 to 1996.98 He found that such racial categories as australoids and Negroid were used consistently about 40 percent of the time for the entire thirty-year period. This large minority shares with the rest of physical anthropology “the general conviction that human behavior is significantly channeled, constrained and determined by human biology.”99 We all have to eat and sleep, for example. However, Cartmill points out that there is a danger of using biology as justification for social order. Race, for example, is often conflated with blood heredity. This essentialist notion leads to arguments about the superiority or inferiority of one biologically delimited group or another. He argues that while Tay-Sachs disease for evolutionary and sociocultural reasons may be more common among Ashkenazim, this does not mean that Ashkenazim are inferior. Membership does not equal Tay-Sachs, and Tay-Sachs cannot be used as proxy for membership. Rather, certain combinations of genes in certain environments can lead to Tay-Sachs disease. Like other social constructs, Cartmill writes, races are real in their consequences.

More pernicious than the consequences of using biological concepts to explain social phenomenon are the ways reductionism, determinism, and geneticization configure the way knowledge is produced. For example, feminist scholars of science have shown the ways that primatology and embryology imagined women, from the outset, only vis-à-vis their biological differences from men.100 Similar conceptual and institutional prefigurations reinforce dubious distinctions between humans from nonprimates, and cleave illness from disease.101 In each case, it is shown how cultural logics shape the ways researchers observe and interpret data and diagnose, manage, or treat human suffering with a priori assumptions about the very phenomenon they seek to understand.

A recurrent theme within this book, therefore, is the ways the objects of interest resist ontological assimilation into the bifurcations of difference and the reductionism that occurs when difference itself is left unexamined. I thought this project was going to easily enable a taking of sides, epistemological at least, related to the matter of race, disease, and human variation. Instead, I found that the dualisms that shaped the conceptualization of the project did not fit. Race, as a kind of differentiation within the diabetes enterprise, was simultaneously many different things, practices, and processes with many different consequences. To be sure, as I will show throughout this book, race, Mexicano, ethnicity, genes, and diabetes can be mapped onto familiar patterns of social reproduction. They also map onto other questions, problems, and logics that are not easily traced in the dystopias of modernity, advanced capitalism, neoliberalism or their often violent histories.

Moving beyond the dualisms that are inherent in reductionistic thought, I argue that the contests between race as social or biological reinforce both sides of the argument while maintaining a hold on the modernist logics of divide and conquer. Thus the challenge I have set forth here is to think about race as an idea, as a thing, as a practice, as a system in a way that does not lead to the grooves of either-or thinking. Thus throughout this book, you will read instances of confluences between natures, cultures, and other binaries. What would race look like had Descartes not successfully mechanized the body, divorcing it from the soul? What would disease look like if health were not its opposite? What would a knowledge making, or an accounting of one epistemological approach to the body look like, feel like, and produce if I resist the temptation to racially place everything about the diabetes enterprise as either social or biological?

Surely this will leave some uncomfortable seeking to locate this work along a continuum of “race” and “no race.” Yet I share with Gravlee the desire to push beyond discussions that reiterate that race is a social construct about which biology can tell us little.102 While true, this insight closes rather than opens the conceptual terrain about race and how it relates to biology. Although I reproduce these debates here, I do so only to orient the reader to the epistemological field in which I situate this project. I find it more productive, more faithful to my field encounters, to resist the dualistic side-taking of biology versus society in examining the diabetes enterprise.

Eschewing reductionistic thinking leaves us with a far more interesting and productive set of approaches to disease, human variation, and race. I draw upon Margaret Lock’s keen insights that “biological difference—sometimes obvious, at other times very subtle—molds and contains the subjective experience of individuals and the creation of cultural interpretations. A dialectic of this kind between culture and biology implies that we must contextualize interpretations about the body not only as products of local histories, knowledge, and politics but also as local biologies.”103 Local biology, like biocultural and ecosocial approaches to human health, requires the simultaneous acknowledgment that diet, physical activity, stress, labor relations, forced migrations, poverty, and a host of other sociohistorical factors shape and are shaped by experiences that can have biological outcomes.104

On the other hand, attempting to explain a particular configuration of biogenetic and medical knowledge requires an acknowledgment that science is a practice that is a product of the lived experience of people who are powerfully influenced by local contexts. Karen Sue Taussig’s work on genomic knowledge and practice demonstrates the “multiple ways the local production of scientific and medical knowledge of genetics and its application in practice intertwine with history, religion, geography, and political economy.”105 Ethnographers of technoscientific sociocultural forms who ignore the context of knowledge production and, I would add, its consumption and reception do so at the risk of clinging to the fictions of a monolith of Western science. As Taussig argues, technoscience unfolds in ways deeply bound to geographic, temporal, local, and global concerns, very few of which travel as “universal scientific objects and events.”106 To assess the meanings and significance of emergent technoscientific claims, let alone to contribute to the understandings of the problems scientists seek to understand, requires that we move beyond old dichotomies and simplistic epistemological tournaments.

For the diabetes enterprise, this postreductionistic approach does not mean that racialization does not occur within my ethnographic encounters or that old, patterned conscriptions of social difference are not made to do biological work and that biological differences are not made to do sociocultural work. Indeed they do. Rather, what I have found confounds simple binaries. Annemarie Mol describes this as mutual inclusion.107 Drawing upon Michel Serres, she notes the Aristotelian logic that proposes difference as mutual exclusion, A and not A, creates a dichotomy where it did not necessarily exist.108 The arguments about race as biological versus race as a social construct operate in similar fashion. Building upon the logics of exclusion in the making of categorical difference, dare I say ontological difference, by thinking “race” is an either-or proposition, as a taxonomic system of mutual exclusions of membership and nonmembership, or as natural or as social, conceals more than it unmasks.109 More than unmasking, however, this book explains how diabetes and social difference are both locked in epistemological approaches that incommensurably trap the social and the biological aspects of blood sugar regulation and population differences in a zero-sum reductionistic claim to the right way to think.