This concise consideration of the historical Jesus will use the Gospel of Mark and the early-sayings source Q to present a historically plausible explanation of the significance of Jesus’ words and actions in Galilee in the early 30s of the first century CE. The task of differentiating what the historical Jesus said and did from secondary interpretations of the tradition after the resurrection is complex. As has been noted, every reconstruction of the historical Jesus privileges certain aspects of the tradition that tend to reinforce one’s preconceptions of Jesus. There are tensions in the Gospel tradition that cannot be resolved without positing that certain parts of it are the result of later theological reflection. Instead of beginning by outlining a method to distinguish what is authentic to Jesus from what is the product of later christological reflection, the priority here is to succinctly reconstruct the Galilean context as a framework for interpreting the earliest layer of the Jesus tradition. Context is the key to interpretation, and even a compact description of Jesus’ Galilean environment elucidates the force of his words and deeds.

Jesus was born in the early years of the Roman Empire, which began when Augustus was declared emperor in 27 BCE. Herod the Great was the client king of the Roman Empire. Herod’s allegiance to Rome was evident in his grand building projects, which included the rebuilding of the Jerusalem temple in Hellenistic-Roman style as well as temples dedicated to the divine Augustus. He also appointed high priests to replace the Hasmoneans, and together with other Herodians they formed a powerful aristocracy that collaborated with Rome. Herod’s massive building program may have brought honor to him and his Roman patrons, but it was the cause of considerable economic distress for those living in Roman Palestine. It is not surprising that when Herod died in 4 BCE, there were rebellions in Galilee, Judea, and Perea that had to be suppressed. The Jewish historian Josephus relates the views of a delegation that went to Rome to complain about the repercussions of Herod’s rule.

He had indeed reduced the entire nation to helpless poverty after taking it over in as flourishing condition as few ever know.… In addition to the collecting of the tribute that was imposed on everyone each year, lavish contributions had to be made to him and his household and friends and those of his slaves who were sent out to collect the tribute because there was no immunity at all from outrage unless bribes were paid. (Josephus, Ant. 17.307–8)

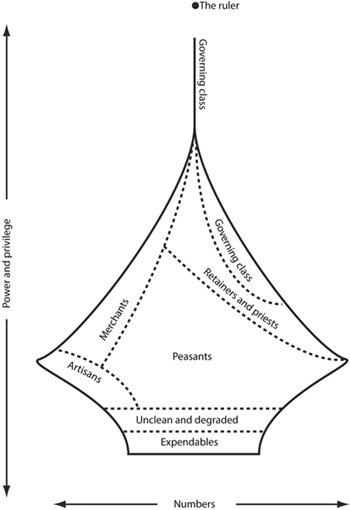

The Roman Empire was an aristocratic empire. The example of Herod illustrates the dynamics in which the majority of resources are controlled by elite families who live off the labor of peasants. Roman Palestine was divided after Herod’s death, and his son Antipas was given control of Galilee by Augustus. Herod Antipas was client king during Jesus’ ministry, and the economic hardship that characterized his rule is reflected in the Gospels. The Jesus movement was a Galilean movement, and Galilee was an agrarian peasant society. Galileans were subjected to a triple tax system that consisted of a temple tax, a Roman tax, and a tax from the Herodian aristocratic administration that placed almost unbearable economic pressure on them. The political facet of this predicament was that this agrarian society was controlled by a ruling aristocracy, mostly from the neighboring cities of Sepphoris and Tiberias, who exploited local peasants through debt slavery. John’s baptism of repentance and Jesus’ message and enactment of the kingdom of God should be seen as responding to this social crisis in Galilee. Figure 2 is a graphic representation of an agrarian tributary society (from Lenski, 284; see Crossan 1991, 45–46).

The first task is to situate Jesus in his Galilean context in the 30s. All the Gospels agree that Jesus’ ministry begins with his baptism by John in the Jordan River. John was an apocalyptic prophet announcing God’s imminent judgment unless Israel repented. In the Gospel tradition, John’s role is described as forerunner to Jesus. However, the Israelites who submitted to his baptism probably understood it as a reenactment of the exodus, as Crossan and Reed suggest, “taking penitents from the desert, through the Jordan, into the Promised Land, to possess it in holiness once again” (117–18). John’s baptism, then, ritualized a hope for liberation from the political and economic oppression that characterized life in Galilee at this time. Jesus began his ministry under the auspices of John the Baptist, and whatever message and ministry he had was, initially at least, aligned with John’s.

One of the main challenges in appreciating the significance of John and Jesus in their Galilean setting is the tendency to regard them simply as religious figures. However, in the ancient world, religion, politics, and economics were inextricably bound together. For Israelites, fidelity to God’s covenant encompassed every dimension of life. The fact that Herod Antipas killed John indicates that he viewed John as a political threat. A passage from the Jewish historian Josephus elucidates both what John was doing and why Herod was concerned.

FIGURE 2. Agrarian tributary society (after Lenski, 284).

For Herod had put him to death, though he was a good man and had exhorted the Jews to lead righteous lives, to practice justice towards their fellows and piety towards God, and so doing to join in baptism. When others too joined the crowds about him, because they were aroused to the highest degree by his sermons, Herod became alarmed. Eloquence that had so great an effect on mankind might lead to some form of sedition. (Ant. 18.117–18)

The Gospels report that Herod expressed the same concern about Jesus when he heard that Jesus had cast out demons and healed the sick.

King Herod heard of it, for Jesus’ name had become known. Some were saying, “John the baptizer has been raised from the dead; and for this reason these powers are at work in him.” But others said, “It is Elijah.” And others said, “It is a prophet, like one of the prophets of old.” But when Herod heard of it, he said, “John, whom I beheaded, has been raised.” (Mark 6:14–16)

Later when Jesus is in Jerusalem, Luke says that some Pharisees warned Jesus,

“Get away from here, for Herod wants to kill you.” He said to them, “Go and tell that fox for me, ‘Listen, I am casting out demons and performing cures today and tomorrow, and on the third day I finish my work.’ ” (Luke 13:31–32)

The activity of John the Baptist and Jesus occurred in Galilee and surrounding villages, where taxation and subsistence agriculture served Herod Antipas’s project of urbanization (Oakman). Richard Horsley has made the connection between the exploitation of the populace in these agrarian villages and the numerous incidents of resistance and rebellion that occurred around the time of Jesus. A related observation is that during Second Temple times most inhabitants of Galilee were descendants of the northern Israelite peasantry, and stood in the northern prophetic tradition calling for the revitalization of Israelite village communities and a return to covenantal principles as a means of redressing social, political, and economic injustices (Horsley 2003). Both John the Baptist and Jesus were shaped by this prophetic tradition and were committed to the renewal of village life in the face of these harsh circumstances. However, while Jesus was initially identified through baptism with John’s more apocalyptic hope of God’s coming in judgment to rectify matters, he is depicted throughout the Gospel tradition as having a different strategy of grappling with the distress and discontent that Galileans experienced.