5

A HERO’S JOURNEY

Primordial feelings provide a direct experience of one’s own living body, wordless, unadorned, and connected to nothing but sheer existence. These primordial feelings reflect the current state of the body along varied dimensions … along the scale that ranges from pleasure to pain, and they originate at the level of the brain stem rather than the cerebral cortex. All feelings of emotion are complex musical variations on primordial feelings.

—ANTONIO DAMASIO, THE FEELING OF WHAT HAPPENS

The transformation of procedural memories, from immobility and helplessness to hyperarousal and mobilization, and finally to triumph and mastery, is a trajectory I have consistently observed in most of the thousands of traumatized individuals that I have worked with over the past forty-five years. Pedro is an example of this primordial awakening.

Pedro

Pedro is a fifteen-year-old adolescent suffering from Tourette’s syndrome, severe claustrophobia, and panic attacks, as well as intermittent asthma like symptoms. He was brought to one of my case consultations during a class I was conducting in Brazil by his mother, Carla. Pedro was obviously very uncomfortable with the idea of talking to a therapist, particularly in a group setting. However, his desire to get relief from the embarrassment and shame about his “tics” and panic attacks helped him overcome his reluctance to attend the session. His tics involved myoclonic jerks and convulsions in the muscles of his neck and face, causing abrupt lateral movements of the jaw and repetitive turning of the head to the right. In taking a history from his mother, I learned his childhood had included significant, serious falls involving repeated shocks to his head. A brief accounting of these incidents is as follows.

At seven months of age, Pedro tumbled several feet out of his crib and landed facedown on the floor. The child’s nanny had discounted the muffled noise of the infant’s terrified screams, reassuring his mother that nothing was amiss with her baby. Though not yet crawling, Pedro had managed to scoot himself to the closed bedroom door. Fifteen or twenty minutes later, his mother, finally succumbing to her persistent maternal concern, tried to open the door and found her child wedged against it, collapsed and whimpering piteously. According to Carla, he had incurred a large hematoma in the fall. She reported grabbing the child off the floor and yelling out an attacking rebuke to the nanny in her panic. This understandable reaction likely further frightened the child and caused Carla to neglect his immediate need for gentle, quiet soothing.

At age three, Pedro had another fall after climbing onto a folding ladder that his older brother had carelessly left unattended. The ladder collapsed as he got to the third rung, throwing Pedro backward onto the ground. The impact of the accident on the child was twofold, with the back of his head hitting the floor and the heavy ladder striking him in the face.

Finally, at the age of eight, Pedro fell yet again. This time he was thrown from a car moving at approximately twenty-five miles per hour. He sustained yet another head injury, as well as deep abrasions across both shoulders. The seriousness of this fall occasioned a weeklong stay in the hospital, with three initial days of isolation in the intensive care unit. Pedro’s tics appeared two months after this third fall.

As we started the session, it was obvious to me that Pedro was uncomfortable in this group setting, as he was fidgeting and glancing furtively around the room. I noticed that he was intermittently clenching his fist and drew his attention to this gesture. I asked him to see if he could begin to feel the sensations of the clenching by “putting his mind right into his fist.” This wording helped Pedro learn to discern the difference between thinking about his hand and actually observing it as physical sensation. Such a shift in perspective can be quite elusive at first, but often arrives suddenly as a “mini-revelation.” This new vantage brings with it an excitement, as though learning a new language and being able to communicate with the locals for the first time; here, however, the foreign language was the interoceptive (interior) landscape of the body and the local resident was the core, primal (“authentic”) Self.

I observed a nascent curiosity in Pedro and asked him to slowly close his hand and then slowly open it as he put his direct (sensate) awareness into this continuous movement.a “So now, Pedro,” I asked, “how does it feel when it is closed into a fist, and then how does it feel when it is slowwwly opened?”

“Hmm,” he responded. “My fist feels strong, like I can stand up for myself.”

“OK,” I replied, “that’s great, Pedro; and now how does it feel when it’s opening?”

At first, Pedro was bewildered by my question, but then he smiled. “It feels like I want to receive something for myself … something that I want. It feels like I really want to get over my panic attacks so I can go to Disneyland.”

“And how does that wanting feel to you right now?” I asked.

He paused and then replied, “It’s funny—my fist feels like it has the power I need to get over my problems. And then when my hand opens it feels like I can use that strength to reach for it, to reach for what I want for myself.”

I asked, “Is there anywhere else in your body where you feel something like that power or that reaching?”

“Well,” he said, pausing for a moment, “I can also feel something like that in my chest … it feels warm there and like I have more room to breathe.”

“Can you show me with your hand where you feel that?” I asked. Pedro made a slow circular movement. As he continued, I noticed that the circle was gradually getting larger in an outward spiraling motion. “So Pedro,” I asked, “Do you feel the warmth spreading?”

“Yes,” he replied, “It feels like a warm sun.”

“And what color is it?”

“It’s yellow, like the sun … Oh wow! Now, when I feel my hand opening, the warmth is spreading into my fingertips and they are starting to tingle.”

“OK, Pedro, that’s great! I think that you are now ready to face the problem.”

“Yeah,” he replied, “Yeah, I know it.”

“And how do you know it?” I asked, tipping my head quizzically.

He giggled. “Oh, that’s easy—I feel it in my body.”

“OK then!” I responded encouragingly. “So then, let’s go on.”

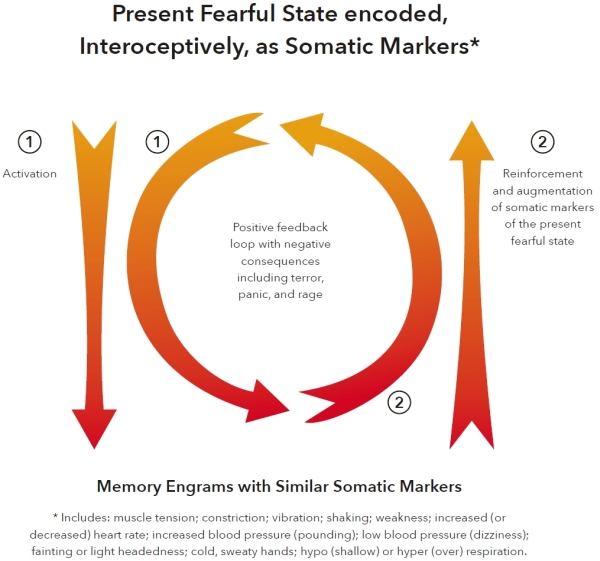

We see in Figure 5.1 (see insert here) that it is our present (here-and-now) somatic state that determines the relationship and platform to renegotiate a traumatic procedural memory. This initial awareness work that I had just completed with Pedro now became the embodied foundation for further investigation. The outcome of the entire session was first germinated in this initial here-and-now inner exploration. Bringing attention to Pedro’s fist may seem trivial; however, it was the sensing of this subtle inner movement, the burgeoning awareness of how this movement really felt from the inside that set the stage for the remainder of the session. This somatically based, resourced platform made it safe enough for Pedro to now process his challenging procedural memories and then ultimately to support their transformation. It cannot be overstated how the body’s felt sense allows physiological access to procedural memories. These are the crucial implicit memories that cognitive approaches simply don’t engage and cathartic approaches frequently override and overwhelm.

A fundamental concept in Somatic Experiencing (SE) is pendulation, used in resolving implicit traumatic memories. Pendulation, a term I have coined, refers to the continuous, primary, organismic rhythm of contraction and expansion. Traumatized individuals are stuck in chronic contraction; in this state of fixity, it seems to them like nothing will ever change. This no-exit fixation entraps the traumatized individual with feelings of extreme helplessness, hopelessness, and despair. Indeed, the sensations of contraction seem so horrible and so endless, with no apparent relief in sight, that individuals will do almost anything to avoid feeling their bodies. The body has become the enemy. These sensations are perceived as the feared harbinger of the entire trauma reasserting itself. However, it is just this avoidance that keeps people frozen, “stuck” in their trauma. With gentle guidance, they can discover that when these sensations are “touched into,” just for a few moments, they can survive the experience—they learn that they won’t be annihilated. While exiting numbness and shutdown often feels more acutely disturbing at first, with gentle yet firm support people can suspend their resistance and open to a tentative curiosity. Then as these sensations are contacted, momentarily and very gradually, the contraction opens to expansion and then moves naturally back to contraction. This time, however, the contraction feels less stuck, less ominous, and then leads to another spontaneous experience of quiet expansion. With each cycle—contraction, expansion, contraction, expansion—the person begins to experience an inner sensation of flow and a growing sense of allowance for relaxation. With this sense of inner movement, freedom, and flow, they gradually ease out of trauma’s terrifying and gripping “dragnet.”

Another foundation stone in this early therapeutic exploration involves contacting both inner strength and the allied capacity for what I call healthy aggression.b For Pedro, this initial contact occurred when he became aware of the felt strength in his fists and then the openness in his hands. Together they comprised the new experience of healthy aggression: the capacity to stand up for himself, to mobilize and direct his power toward getting what he needs, and thereby opening to new possibilities. So with this reliable, steadfast foundation, Pedro was now equipped to confront the dragons that were “dragging-on” his aliveness and forward movement in life. So what happened next?

I engaged Pedro in a series of slow, repeated titrated, movement exercises that involved gradually opening his mouth to the point of resistance and then gently closing it.18 These exercises replicated his earlier exploration of contraction and expansion, and interrupted Pedro’s compulsive “over-coupled” sequence of neuromuscular contractions in his head, neck, and jaw. A rest between each set of these openings and closings allowed for an interlude of settling, a periodic quieting of his arousal. As Pedro moved through these graduated efforts, he experienced some abrupt shudders in his neck and shoulder, and then a softer trembling (a “discharging”) in his legs during the resting phase.19 He also reported an uncomfortable and intense burning heat that emanated from the tops of his shoulders. This “body memory,” his mother later observed, was located where the lacerations from his third childhood fall had left considerable scarring. After several more cycles of micro-movement/discharge/rest, Pedro’s tics were significantly reduced and he was clearly more present and available for interaction with me, as his “guide,” and the class as his supportive allies.

As the tic movements subsided, Pedro reported feeling much more at ease. I then asked him what he wanted most from the session. He offered that he was really hoping to get rid of his claustrophobic fears so that he could travel with his family from Brazil to Disneyland for spring vacation. He told me that previously he had experienced a panic attack when he was in a hot, stuffy plane that got delayed at the gate, held in waiting for over thirty minutes with its doors sealed shut. I asked him what he noticed when he thought about being in the plane.

“Scared,” he murmured.

“And how does that feel in your body?”

“Like I can’t really breathe … like there’s a band around my chest … I really can’t breathe.” I put my foot next to Pedro’s, asking first if that would be OK. “Yes,” he responded, “it helps me not go away into the air.”

With this added “grounding,” I asked Pedro whether the tension in his chest had become stronger or weaker, stayed the same, or if it had changed to something else. This type of open questioning evoked a stance of curiosity on Pedro’s part. He paused for a few moments and then offered, “It’s definitely getting better. It feels like I can take a breath.”

“Is there anything else that you notice?” I asked.

“Yes,” he replied “I feel some warmth in my chest again … and it’s starting to spread up into my face.c

“Yeah,” he added “it’s really spreading now, moving through the rest of my body … it feels really good, like warm tingles and a gentle shaking … and inner shaking … that’s really funny … it’s like the panic went away, like it’s gone … like it’s really gone!”

I asked Pedro if he could recall another recent experience involving his claustrophobic panic. He described an occasion a year earlier when he was playing in a swimming pool with a large ball that could be entered into through a zippered opening. Once a person was inside, the ball could be closed from within by pulling up on the zipper. The passenger could then roll the ball across the surface of the water by shifting his weight. This ball was meant to create fun and excitement. Pedro, however, was not having fun. Instead, the closed interior was stifling to him and he fell backward. This re-created the terrifying interoceptive experience of his previous falls, as well as the suffocation panic he had experienced when he was caught in the airplane. Pedro panicked when he could not open the ball. Though unable to scream because of his hyperventilated breathing, his stifled moans did, once again, alert his mother. While unzipping the ball from the outside and freeing her son from his predicament, she felt an anguish similar to that which had been provoked by the strangulated moans of her injured seven-month-old baby. When Pedro emerged from this ensnaring cocoon, he saw, again, his mother’s frightened face. Her terrified expression startled him once again, intensifying his feeling of fear and defeat.

As Pedro completed his rendering of this most recent panic episode, I noted that he was slumped over in his chair. It was as though his shoulders had hunched forward and his middle spine had collapsed over his diaphragm. This sunken posture mirrored the abject shame, despair, and overwhelming passivity of his rescue—both as an adolescent and as an infant. Recognizing a timely opportunity to help Pedro experience some agency in his body, I brought his attention to his fist, which he was once again subconsciously opening and closing. “Hmm,” he replied, “I can feel some of the strength here; it’s coming back. It reminds me of when we first started the session.” I then guided him to sense his posture and to gently deepen his forward slump. This sinking collapse came to rest, and then a spontaneous gradual upward rebound movement began. I encouraged him to simply notice his felt experience as his spine lengthened and his head lifted upward. This conscious encounter conveyed an unexpected sense of pride, or even triumph, which he acknowledged with these words: “Wow, that feels a lot better, like I can hold my head up and look ahead; it makes me feel more confident.”

Building on this burgeoning exhilaration, I asked Pedro if he would be willing to revisit his most recent moment of defeat. He agreed. I suggested that he picture himself inside the ball. He seemed ready to engage in this challenging somatic visualization. He described entering the ball, closing the zipper, and then losing his balance as he started to fall backward. As he recalled this series of events, his embodied imagination led to a reexperiencing of the vertigo. This dizziness had previously ignited the initial phase of a panic reaction, including a tightening of his chest and hyperventilation. This, in turn, amplified his panicky feelings of suffocation. However, he was now able to experience it without feeling overwhelmed. I guided him to once again attend to the specific sensations of constriction around his chest, and his breathing gradually settled and he took several spontaneous, slow, and easy breaths with full exhalations.

We then explored his sensation of falling backward. I gently supported Pedro’s upper back and head with my hands, while encouraging him to surrender and let go into the sensations of falling. He immediately reported that he “needed to get out!”

I responded calmly with the question, “And how can you do that?”

To this he replied, “It feels like I am leaving my body.”

“OK,” I answered, “let’s just see where you go.”

He acknowledged that he was afraid to give into “this weird floating feeling.” Pausing to provide reassurance, I gently encouraged him to notice the floating sensations and asked him where he might float to. When this kind of dissociation occurs, it is important not to ask body-based language questions, but rather to accept and follow the dissociated experience. Pedro hesitated and then said, “Up—up out of the ball.”

“Well, that might be a good place to be,” I suggested.

He then described looking down at the ball from above and also knowing that he was inside of it.

I inquired, “OK, what might you want to do from up there?”

He replied, “I would like to go down and open the zipper.” Even though Pedro was partially dissociated, he was able to envision and execute, in his imagination, this active (motoric) escape strategy. Previously, he had to rely on his mother to rescue him—hardly an empowering experience, particularly for an adolescent. This “renegotiation” led to a further reduction of his tics.

Pedro then recalled an earlier time when he’d had a similar experience. He told me that when he was five years old, the door to his bedroom got stuck and would not open. He remembered pulling at it with all of his might, to no avail. He recalled that this had precipitated a terrifying panicky reaction, like what had happened in the airplane. As therapeutic observers, we can see how this was a “replay,” an echo, of his earliest experience of being hurt, helpless, and alone at seven months old. Falling out of his crib, being unable to get to his mother, and then being alone for twenty minutes (an eternity for a baby) had branded him with this searing and enduring emotional and procedural imprint.

As such, Pedro’s five-year-old panicky “overreaction” to the stuck bedroom door is more than likely due to that earlier (seven-month-old) fall with its serious injury, extreme helplessness, and thwarted efforts to solicit timely attention. However, with the one success in embodied imagery of getting out of the ball under his belt, and with a relaxed determination in his jaw from the jaw awareness exercise, I had the sense that he would be able to complete his five-year-old escape from the bedroom in a way that he had not been able to accomplish previously. I felt that he would persevere and not be defeated this time.

I now asked Pedro to continue imagining pulling at the door knob and urged him to feel his whole body as he engaged in this assertive effort. When I inquired about a brief flicker of a smile that flitted across his face, he boldly described how he pulled and pulled and kicked and finally broke the door down. He then smiled broadly and I asked him where he could feel that Cheshire grin. “Oh,” he replied, “I can really feel it in my eyes, my arms, my chest, shoulders, legs, and even here,” he said, pointing to his belly. “Really all over my body. I feel super strong and powerful, like a superhero … my body can protect me,” he offered triumphantly.

Like many parents, Pedro’s mother had reported that she was concerned about her teenage boy’s excessive use of the computer and internet; it did appear that his usage was extreme and compulsive. Two days after our session, she reported that Pedro had asked her to buy him some art supplies. He used to enjoy drawing as a child, but after his symptoms had worsened and involved his face, head, and neck, he had lost all interest in art and became glued to the computer. This compulsion seemed to make his symptoms worse. She was more than a little pleased with this new artistic development. And then to her complete surprise he took the bold initiative of joining a singing class at his school. There he could feel the powerful connection between his jaw and diaphragm. Pedro also relayed to his mother that he had a new plan for his future schooling, stating that he wanted to do research in the field of psychology instead of his earlier choice of engineering. He was fascinated by what was going on in his own brain and was eager to do the brain scan that they had put off for years because his claustrophobia was so severe. Pedro now expressed excitement about planning the family trip to Disneyland. Apprehension about the long plane trip seemed to have disappeared. This most certainly was a new multidimensional change of perspective on his future—a future very different from his past. So let us now briefly summarize the steps of renegotiation that brought Pedro to his new, updated memories and how they enabled Pedro to put his past behind him and then move forward, empowered and self-directed.

To summarize, the basic steps in renegotiating a traumatic memory generally involve these processes:

1. Help create a here-and-now experience of relative calm presence, power, and grounding. In this state the client is taught how to visit his positive body sensations, as well as his difficult, traumatically based sensations.

2. Using this calm, embodied platform, the client is directed to gradually shift back and forth between the positive, grounded sensations and the more difficult ones.

3. Through this sensate tracking, the traumatic procedural memory emerges in its traumatic, truncated (i.e., thwarted) form. The therapist continues to check that the client is not in an over-activated (or under-activated) state. If they are, the therapist returns to the first two steps.

4. Having accessed the truncated form of the procedural memory, the therapist, recognizing the “snapshot” of the failed (i.e., incomplete) response, encourages further sensate exploration and development of this protective action through to its intended and meaningful completion.

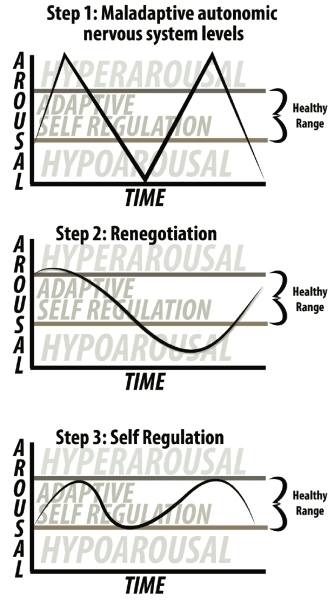

5. This leads to a resetting of the core regulatory system, restoring balance, equilibrium, and relaxed alertness.20 (See Figure 7.1, here.)

6. Finally, the procedural memories are linked with the emotional, episodic, and narrative functions of memory. This allows the memory to take its rightful place where it belongs—in the past. The traumatic procedural memories are no longer being reactivated in their maladaptive (incomplete) form, but are now transformed as empowered healthy agency and triumph. The entire structure of the procedural memory has been changed, promoting the emergence of new (updated) emotional and episodic memories.

A key feature in working with traumatic memories is to visit them incrementally from the vantage of a present state which is neither a state of hyper-activation and overwhelm nor a state of shutdown, collapse, and shame. This can be a bit confusing for therapists, because individuals who are in a state of shutdown may appear to be calm.

In general when working with procedural memories, it is best to work with the more recent ones first. In reality, however, all procedural memories with similar elements and attendant states of consciousness tend to merge into a composite procedural engram. Pedro’s explicit recall of being trapped in the ball allowed him to access the procedural engram of being helplessly trapped and then to engineer an active escape. The full renegotiation of the composite engram was accomplished, so to speak, retrospectively. This allowed Pedro to find completion, first in freeing himself from the ball as an adolescent and then in opening the door as a five-year-old. These two discreet phases of his session also helped address the composite engram that included his pervasive feelings of helplessness as an infant. Hence, his primal infantile anguish was also neutralized to some degree along with the successful reworking of his adolescent and five-year-old traumas.

Pedro’s form of triumph was also manifested in a session I had with a champion marathon runner who was dealing with intimacy problems related to her childhood sexual abuse by an uncle. In her session, she experienced the impulse to fight back and kick him in the genitals. She also recognized (with a growing self-compassion) that he had, in fact, fully overpowered her as a four-year-old. After that, she then felt her power returning, as she imagined extending her arms as a form of boundary against his advances. At the end of the session, she reported feeling like she had run a marathon. I asked her what that felt like, to which she replied: “It felt like I was getting to a point where my legs were going to give out; they felt like I could barely stand, no less continue to run … and then something happened. It was like I heard a voice in my head saying, ‘Just keep moving … keep moving.’”

I asked her if that was a common experience for long-distance runners. “Yes,” she replied, “but in our session, I was feeling that from the inside, inside the whole of me, not just in my legs. I can defend myself now; I know I have this capacity for enduring great challenges and overcoming obstacles.”

She told me a week later that she had experienced some opening to sexual intimacy—and this, she added, “was her greatest triumph over him [her uncle].”

On the Will to Persevere

The world breaks everyone and afterward many are strong in the broken places.

—ERNEST HEMINGWAY

You gain strength, courage, and confidence by every experience in which you really stop to look fear in the face. You are able to say to yourself, “I have lived through this horror. I can take the next thing that comes along.” You must do the thing you think you cannot do.

—ELEANOR ROOSEVELT, YOU LEARN BY LIVING: ELEVEN KEYS FOR A MORE FULFILLING LIFE

My forty-five years of clinical work confirms a fundamental and universal instinct geared toward overcoming obstacles and restoring one’s inner balance and equilibrium: an instinct to persevere and to heal in the aftermath of overwhelming events and loss. In addition, I suspect that this instinct has physical footprints in a biological rooted will to persevere and triumph in the face of challenge and adversity. Any therapist worth his or her fees not only recognizes this primal capacity to meet adverse challenges, but also understands that their primary role is not to “counsel,” “cure,” or “fix” their clients, but rather to support this innate drive for perseverance and triumph. But how do we facilitate the fulfillment of this instinct?

I will freely admit that this inner quest for transformation, illustrated by Pedro’s journey, portrays a drive, the nature of which I have reflected upon and pondered for many of these years. Recently a German colleague, Joachim Bauer, knowing of my investigations, handed me an obscure journal article based on the treatment of a few epileptic patients. However, before we discuss this interesting paper, let me first offer a short background on the neurosurgical treatment of epilepsy.

Since the pioneering work of the eminent mid-twentieth-century neurologist Wilder Penfield, a procedure for remediating severe, intractable epilepsy involved cutting out the brain cells that are damaged, thus averting these violent “nerve storms.” However, before this surgical extirpation proceeds, the neurosurgeon must first establish what the afflicted brain region controls or processes. This is done so that the surgeons do not inadvertently cut out and interfere with a function vital to that individual. Since there are no pain receptors in the brain, this procedure is readily done with the patient fully awake and responsive as the surgeon stimulates these focal areas with an electrode probe.

Until recently, most of these electrical stimulations have been confined to the surface of the brain and have been associated with specific concrete functions. For example, if somato-sensory areas are stimulated, patients generally report sensations in various parts of their body. Or if the motor cortex is stimulated, then a part of the body, such as a finger, moves in response to the electrical stimulus. Penfield also reported that there were some “associational” areas (including the hippocampus) that, when he stimulated them, the person reported dreamlike reminiscences. Some sixty-five years later, after these initial investigations, protocols were developed to position electrodes in various deep brain areas for the same purpose of treating intractable epilepsy.

In the provocative case study handed to me by my German friend, a group of Stanford researchers published an article with the intriguing title “The Will to Persevere Induced by Electrical Stimulation of the Human Cingulate Gyrus.”21 It reported on an unexpected experience provoked by the delivery of deep brain stimulation to a completely different part of the brain than had been previously explored by Penfield and other earlier neurosurgeons. This brain region is known as the anterior midcingulate cortex (aMCC).

The patients in this study experienced something quite remarkable. The exact words of patient number two, as his aMCC was stimulated, were: “I’d say it’s a question … not a worry like a negative … it was more of a positive thing like … to push harder, push harder, push harder to try and get through this … if I don’t fight, I give up. I can’t give up … I (will) go on.” Patient one described his experience with this metaphor: “It’s like you were driving a car into a storm and … like one of the tires was half-flat … and you’re only halfway there and you have no other way to go back … you just have to keep going forward.” Both patients in the study recounted a sense of “challenge” or “worry” (known as foreboding), yet remained motivated and prepared for action, aware that they would overcome the challenge. Wow!

During the stimulation of these patients, the authors noted increases in heart rate, while at the same time the patients reported autonomic signs including “shakiness” and “hot flashes” in the upper chest and neck region. Indeed, for me this rang a thunderous bell, as most of my clients have reported very similar autonomic sensations as they worked with their traumatic procedural memories and moved from fear through arousal and mobilization into triumph. At the same time, my clients exhibited subtle postural changes including an extension of the spine and an expansion of the chest.

From a physiological point of view, there is at the level of the aMCC a functional convergence of the (dopamine-mediated) systems for motivation and the (noradrenergic) one for action. To keep things in perspective, let us not forget that for thousands of years, well before the advent of neuroscience, such triumphant convergence of motivation and action, of focus and the will to persevere, has been described in numerous myths from around the world and in our everyday lives. From a mythological vantage, these researchers and their courageous patients may have just uncovered a neurological substrate of the “hero’s journey.”

In his landmark book The Hero with a Thousand Faces, the eminent mythologist Joseph Campbell traces the occurrence of this myth throughout the world and across recorded history. He makes a compelling case that it is precisely this coming to terms with one’s destiny, through meeting a great challenge (whether external or internal) and then mastering it with clear direction, courage, and perseverance, that is at the core of this universal archetype, the hero/heroine myth. This perseverance in meeting extreme adversity is also the basis of many shamanic initiation rituals. The will to persevere, this initiation or trial by fire, may be exactly what this sliver of brain tissue—the aMMC—seems to orchestrate. Indeed, it may be part of the core neural architecture facilitating triumph over adversity, the quintessential encounter of the human condition. Clinically, we need to address the central question of how that part of the brain normally gets stimulated in the absence of epilepsy and depth electrodes.

Current research on the aMCC shows that this brain region is activated when there are stimuli of strong affective salience, whether positive or negative. It has clear neural connections with areas in the insula, amygdala, hypothalamus, brain stem, and thalamus. The aMCC, along with the insula cortex, receives its primary input from sense receptors inside the body. In addition, it is the only part of the cortex that can actually dampen the amygdala’s fear response.22 Indeed, this circuit of thalamus, insula, anterior cingulate, and the medial prefrontal Cortex receives interoceptive information, i.e., involuntary internal body sensations, and affects the preparation for action via the extrapyramidal motor system. These are the very fabric of which procedural memories are made.23 (See Figure 7.1, here.)

Without the benefit of a multimillion-dollar brain scanner, we are free to speculate on the two-way communication between Pedro’s brain and body as his internal body sensations change from ones of fear and helplessness to those of triumph and mastery. To this end I wish to enlist the existence of a crucial “instinct”: an innate somatic drive to overcome adversity and move forward in life. Indeed, without this primal instinct, trauma therapy would be limited to insight and cognitive behavioral interventions, whereas with this instinct engaged, transformation becomes possible as the client gradually meets and embraces trauma. I further speculate that this instinct operates through activating the coordinated, procedurally based systems for motivation, reward, and action. This convergence of motivation and action systems (dopamine and noradrenaline) is what I have called “healthy aggression.”

A few case studies on the deep brain stimulation of epileptic patients can hardly be considered proof of the existence of an instinct to persevere and triumph. However, a body of clinical evidence (as I describe in In An Unspoken Voice), as well as the accumulation of world myths, rituals, and a multitude of films and written literature, speaks to the universality of perseverance and triumph over obstacles and challenges as being at the heart of human endeavors. Perhaps this hard-wiring for transformation not only speaks to our humanity but also connects us to our ancestors, both human and animal.

Indeed, in the session with Pedro, we saw how the access and completion of his procedural memories was the therapeutic pathway toward confronting and transmuting his demons and then to “mythically” fulfilling his rite of passage as he transformed these procedural memories from helpless child to competent adult. Thus, he begins to assume the mantle of his destiny as a potent and autonomous young man.

Insula, aMCC, and Ecstasy—A Spiritual Side of Transforming Trauma

Fyodor Dostoevsky, who suffered from grand mal seizures, wrote of his experience in words which might seem fanciful: “A happiness unthinkable in the normal state and unimaginable for anyone who hasn’t experienced it … I am then in perfect harmony with myself and the entire universe.” These sensations seemed to inform his epic novel The Idiot, whose central character, Prince Myshkin, says of his attacks, “I would give my whole life for this one instant.”

The question about how wide ranging these “peak” experiences are among other “sufferers” has been difficult to ascertain, perhaps because people fear that they would be considered “crazy.” However, a few neurologists have found what is referred to as “the Dostoevsky effect” to be a fascinating, if not legitimate, area of study. In epilepsy treatments similar to the Stanford group’s stimulation of the aMCC, neurologists at the University Hospital of Geneva in Switzerland seem to have localized the initial focus of a subpopulation of their patients with “ecstatic seizures.”24 Using powerful brain imaging techniques for detecting location of activity, they reported that the insula seems to be the focal region. In stimulating the anterior insula, they were able to evoke “spiritual rapture” in a few of their patients. It is noteworthy that when one of the patients was told she could probably be cured of her epilepsy, were she willing to forfeit these ecstatic states, she boldly and summarily declined. Even with her severe epilepsy, “it was not worth the trade-off.”

The insula is divided into posterior (back) and anterior (front) sections. It appears that the posterior part registers raw (“objective”) sensations, both internally and externally generated. In contrast, the anterior portion (which is associated with the aMCC) seems to process more refined, nuanced, and subjective feeling-based sensations and emotions. Craig,25 Critchley,26 and others have suggested that the anterior insula is largely responsible for how we feel about our body and ourselves. Furthermore, they note, the left side of the insula is related to positive feelings and the right side to negative ones. Once again, it is the part of the brain that receives input from interoceptive (internal body) sensors. In this regard, various spiritual traditions have developed breathing, movement, and meditative techniques to evoke these types of spiritual states while also providing guidance on how to deal with the polarity of these emotional and sensation-based states—that when one experiences ecstasy, there is a subsequent “let down,” a swing to the negative realms.

In renegotiating trauma via Somatic Experiencing, we utilize “pendulation,” the shifting of body sensations or emotions between those of expansion and those of contraction. This ebb and flow allows the polarities to gradually be integrated. It is the holding together of these polarities that facilitates deep integration and often an “alchemical” transformation.

What follows in Chapter 6 is a textual and visual demonstration of the role of procedural memories in trauma resolution, taken from videos of sessions with two clients. The first sequence shows a fourteen-month-old toddler named Jack. Because of his age and verbal development, his work involves only procedural and emotional memories. However, when he returns two-and-a-half years later for a follow-up, we see how the procedural memory has evolved into an episodic one.

The second session involves work with a Marine named Ray who was hit by blasts from two IEDs in Afghanistan after having his best friend die in his arms. After he resolves the procedural memories of the blast (shock trauma), he is then able to access and process his emotional, episodic, and narrative (declarative) memories, and comes to a deeper peace with his survivor’s guilt, grief, and his loss of community.

Figure 5.1. Somatic Markers. The above graphic illustrates how our present interoceptive state links to emotional and procedural memories exhibiting similar states. Our current physical/physiological and emotional response unconsciously guides the type of memories and associations that will be recalled; present states of fear evoke fear-based memories, which in turn reinforce the present agitated state. This can lead to a positive (“runaway”) feedback loop of increasing distress and potential retraumatization.

Figure 5.2. Window of Self-Regulation. The above charts show the renegotiation of hyperarousal (overwhelm) states and hypoarousal (shutdown) states in re-establishing the range of self-regulation and restoring dynamic equilibrium.

a. The emphasis of this slow, deliberate, mindful inner movement contrasts with what is frequently asked for in various expressive therapies, such as “psychodrama” or some Gestalt therapies. These therapies tend to accentuate gross external movement rather than internal, felt, movement. These inner movements are more involuntary and employ different brain systems, including the brain stem, cerebellum, and extrapyramidal systems.

b. The word “aggression” derives from the Latin verb aggredi, which can mean “to approach,” “to have a goal,” “to seize an opportunity,” or “to desire,” among other things.

c. This corresponded visibly to a mild vasodilation in his throat and face, as observed by the “glowing” color tone of his skin.