You need to know only two tags in order to create a frame

document: <frameset> and

<frame>. In addition, the HTML 4 and XHTML standards provide the

<iframe> tag, which you may use

to create inline, or floating,

frames, and the <noframes> tag

to handle browsers that cannot handle frames.

A frameset is simply the

collection of frames that make up the browser's window. Column- and

row-definition attributes for the <frameset> tag let you define the number

of and initial sizes for the columns and rows of frames. The <frame> tag defines which document—HTML

or otherwise—initially goes into the frame within those framesets

and is where you may give the frame a name to use for

document hyperlinks.

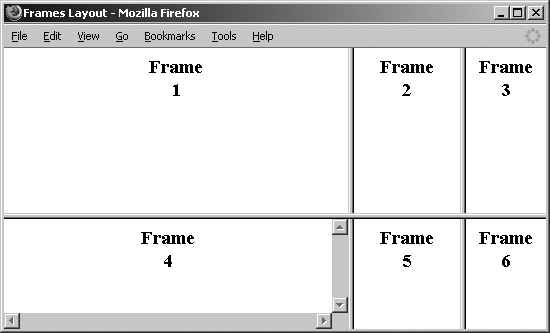

Here is the HTML source we used to generate Figure 11-1:

<html>

<head>

<title>Frames Layout</title>

</head>

<frameset rows="60%,*" cols="65%,20%,*">

<frame src="frame1.html">

<frame src="frame2.html">

<frame src="frame3.html" name="fill_me">

<frame scrolling=yes src="frame4.html">

<frame src="frame5.html">

<frame src="frame6.html" id="test">

<noframes>

Sorry, this document can be viewed only with a

frames-capable browser.

<a href = "frame1.html">Take this link</a>

to the first HTML document in the set.

</noframes>

</frameset>

</html>

Notice a few things in the simple frame example and its rendered

image (Figure 11-1). First,

like tables, the browser fills frames in a frameset row by row. Second,

Frame 4 sports a scroll bar because we told it to, even though the

contents may otherwise fit without scrolling. (Scroll bars automatically

appear if the contents overflow the frame's dimensions, unless

explicitly disabled with the scrolling attribute in the <frame> tag.)

Another item of interest is the name attribute in the example frame tags. Once

named,[*] you can reference that particular frame as the target in

which to display a hyperlinked document or perform some automated

action. To do that, you add a special target attribute to the anchor (<a>) tag of the source link.

For instance, to link a document called new.html for display in Frame 3, which we've

named fill_me, the anchor looks like

this:

<a href="new.html" target="fill_me">

If the user chooses the hyperlink—say, in Frame 1—the new.html document replaces the original frame3.html contents in Frame 3. [The target Attribute for the <a> Tag, 11.7.1]

Anyone who has opened more than one window on their desktop display to compare contents or operate interrelated applications knows instinctively the power of frames.

One simple use for frames is to put content that is common in a collection, such as copyright notices, introductory material, and navigational aids, into one frame, with all other document content in an adjacent frame. As the user visits new pages, each loads into the scrolling frame, while the fixed-frame content persists.

A richer frame document-enabled environment provides navigational tools for your document collections. For instance, assign one frame to hold a table of contents and various searching tools for the collection. Have another frame hold the user-selected document contents. As users visit your pages in the content frame, they never lose sight of the navigational aids in the other frame.

Another beneficial use of frame documents is to compare a returned form with its original to verify the content the user submitted. By placing the form in one frame and its submitted result in another, you let the user quickly verify that the result corresponds to the data entered in the form. If the results are incorrect, the form is readily available to be filled out again.

[*] But, interestingly, not id'd, even though the attribute exists for

frames and can identify other HTML/XHTML elements as hyperlink

targets.