There is no quantum world. There is only an abstract physical description. It is wrong to think that the task of physics is to find out how nature is. Physics concerns what we can say about nature…

—Niels Bohr1

ANOMALIES

In the late nineteenth century, the wave theory of light seemed secure. It was consistent with all observations with just three exceptions, three anomalies that could not be explained within the theory as it was understood at the time.

When the optical spectrograph was developed, it became possible to measure the wavelengths of light from various sources. These measurements extended beyond both ends of the visible region of the electromagnetic spectrum, from the shorter wavelengths of the ultraviolet to the longer wavelengths of the infrared.

It was found that all bodies emit a smooth spectrum of light, whose peak intensity occurs at a wavelength that depends on the temperature of the body: the higher the temperature, the shorter the wavelength at peak intensity. For the very hot sun, the peak is smack in the center of the visible spectrum, in the region humans recognize as the color yellow.

What a coincidence! The spectrum of our main source of light, the sun, just happens to be right in the center of our visual capability. This is an example of what in recent years has been termed the anthropic principle: the universe is just so, “fined-tuned” so we and other life-forms are able to exist.

Actually, the universe is not fine-tuned for us; we are fine-tuned to the universe. Obviously, our eyes evolved so they would be sensitive to the light from the sun. Animals that could see only x-rays would find it difficult to survive on a planet where most of the objects around them do not emit x-rays. While other so-called anthropic coincidences are not so obvious, it has not been shown that they are so unlikely that the only explanation is a supernatural creation.2

At lower temperatures, such as those in our everyday experience, bodies radiate light in the infrared region where our eyes are insensitive, although we can see the infrared with the night-vision goggles of modern military technology or with infrared photography. You can buy a photo of your infrared “aura” at most psychic fairs. It is not empirical evidence for any supernatural qualities.

Despite psychic claims, your aura is perfectly natural. It is an example of what is called blackbody radiation. Everyday objects that do not emit or reflect visible light appear black to the naked eye, hence the name of this type of radiation.

According to the wave theory of light, vibrating electric charges inside a body emit electromagnetic waves. The lower the wavelength of these waves, the greater number of them can “fit” inside the body. So the wave theory predicts that the intensity of emitted light will increase indefinitely as you go to shorter and shorter wavelengths. This is called the ultraviolet catastrophe and is simply not observed. Rather the intensity of light falls off smoothly at both ends of the spectrum. This is anomaly number one.

Anomaly number two also involves the spectra of light. When a gas is subjected to an electric discharge (a spark) or otherwise heated to a high temperature, the observed spectrum is not totally smooth, although it still has a smooth part, but is composed of very narrow, bright lines at well-defined wavelengths. These are called emission lines. A gas will also exhibit sharp, dark absorption lines when a broad spectrum of light shines through it. The wonder of these line spectra is that they are different for gases of different chemical composition, providing a powerful tool for determining chemical compositions for materials on Earth and even deep in space.

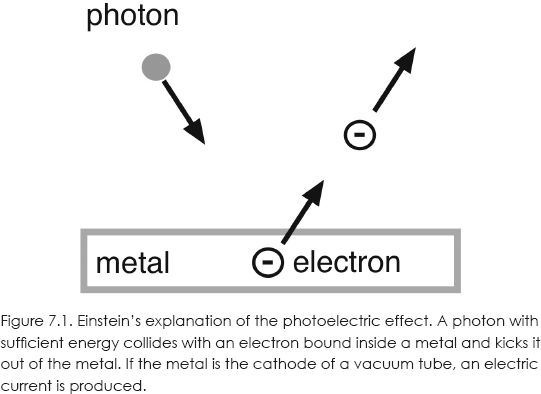

The third anomaly that was observed in the late nineteenth century is the photoelectric effect. When light is beamed onto the metal cathode of a vacuum tube, an electric current is sometimes produced in the tube. The wave theory predicts that the current should increase with increased intensity of light, since the energy in a light beam is greater when the intensity is greater. In fact, increasing the intensity has hardly any effect. Instead, a threshold frequency exists below which no current is produced, a current occurring only after you go above that value. In addition, the energy of the free electron is a function of the frequency of the light, not its intensity.

The frequency f of a wave is the number of crests of the wave that pass a certain point per unit time. The wavelength λ of the wave is the distance between crests. The two are related by f = c/λ, where c is the speed of the wave. In the case of light in a vacuum, c is the speed of light.

LIGHT IS PARTICLES

At the University of Munich, Max Planck (1858–1947) had written his doctoral dissertation, which he defended in 1879, on the second law of thermodynamics. He was no immediate fan of atomic theory, having the same objection as many physicists of the time that it involved probabilities rather than the certainties of thermodynamic law. In 1882 he wrote, “The second law of the mechanical theory of heat is incompatible with the assumption of finite atoms…. A variety of present signs seems to me to indicate that atomic theory, despite its great successes, will ultimately have to be abandoned.”3

Sometime around 1898, Planck seems to have made an abrupt reversal in his thinking and realized that the second law must be probabilistic. He had been studying the thermodynamics of electromagnetic radiation and realized that the same probability arguments used to derive Boltzmann's formula for entropy, S = klogW, could be applied in that situation.4

In 1900, Planck proposed a model that quantitatively described the blackbody spectrum. He still applied the wave theory in visualizing a body as containing many submicroscopic oscillators. However, he added an auxiliary assumption: the energy of the electromagnetic waves occurs only in discrete bunches proportional to the frequency of the waves. Planck dubbed these bunches quanta. While he was not quite ready to call these “atoms of light,” he had made a major move in applying the discreteness of the atomic theory to electromagnetism and thereby ushered in the quantum revolution.

Planck proposed that the energy of quanta are multiples of hf, where f is the frequency and h is a constant of proportionality now called Planck's constant. He was able to estimate the value of h by fitting his model to measured blackbody spectra. Not only did he get the shape of the spectrum right, he also obtained the correct temperature dependence. In the energy units we are using, h = 4.14× 10–15 eV-seconds. That is, the energy of a quantum of light with a frequency f = 1015 cycles per second (Hertz), or a wavelength of λ = c/f = 3 × 10–7 meter, will be 4.14 eV.

Planck did not speculate on the origin of the quantization of light energy. Einstein provided the explanation in a remarkable paper on the photoelectric effect that was published the same year, 1905, as his other remarkable papers on special relativity and Brownian motion. Although you will hear otherwise from some authors who would like you to think that the quantum revolution dispensed with the reductionist, materialistic view of matter and energy, we will see that the story is quite the opposite.

It was Einstein who proposed that the quanta of light were actually particles, later dubbed photons. Each photon has an energy E = hf, where f is the frequency of the corresponding electromagnetic wave, as suggested by Planck. Einstein viewed the photoelectric effect as a particle-particle collision between a photon and an electron in the metal (see fig. 7.1). Since that electron is initially bound in the metal, some minimum energy is needed to kick it out into the vacuum tube to produce the observed current.

An American physicist, Robert A. Millikan (1868–1953), was convinced that Einstein was wrong since it was already well established that light was a wave. He spent a decade trying to prove it. Instead, as he later admitted, his results scarcely permitted any other explanation than the photon theory of light.

By applying a back potential to the anode of a vacuum tube, Millikan was able to measure the minimum energy a photon had to have in order to remove an electron from the metallic cathode, as a function of frequency of the corresponding light wave. He found that the energy was proportional to the frequency of the light with a constant or proportionality equal to Planck's constant, precisely as Einstein had predicted.

The equations of special relativity require that an object traveling at the speed of light must have zero mass. However, a photon has both energy and momentum, which (in units c = 1) implies that m2 = E2 – p2 = 0, that is, E = p. So, even though it has zero mass, since anything with energy and momentum is matter, the photon is matter.

And so, Einstein revived Newton's corpuscular theory of light. At the same time, light still diffracted as expected from waves, and no violation of Maxwell's electromagnetic wave theory of light was found. Light thus exhibits what became known as the wave-particle duality, about which we will have more to say. But first—back to atoms.

THE RUTHERFORD ATOM

To avoid confusion on the meaning of the term atom, which is used in several contexts in this book, I will sometimes refer to the atoms comprising the chemical elements as chemical atoms. Early in the twentieth century, the chemical atoms were found not to be uncuttable after all but composed of parts that are more elementary.

In 1896, French physicist Henri Becquerel (1852–1908) discovered that uranium wrapped in thick paper blackened a photographic plate. The paper ruled out the possibility that the effect was caused by visible light, such as from phosphorescence. The phenomenon was dubbed radioactivity. Further observations, notably by Marie (1867–1934) and Pierre (1859–1906) Curie, identified various types of radioactive emanations associated with different materials. These were called alpha, beta, and gamma radiation. Ernest Rutherford (1871–1937) inferred that some of these phenomena were associated with the transmutation of one element to another.

In 1909, Rutherford, along with Hans Geiger (1882–1945) and Ernest Marsden (1889–1970), performed an experiment in which gold foil was bombarded with alpha radiation. In 1911, Rutherford proposed a model of the gold atom that explained the large angles at which the alpha rays were occasionally deflected. In Rutherford's model, the atom has at its center a positively charged nucleus that contains almost all the mass of the atom while at the same time being very much smaller than the atom as a whole. Rutherford envisaged the atom as a kind of solar system, with the nucleus acting as the sun and electrons revolving around the nucleus like planets.

In 1917, Rutherford made the alchemists’ dream a reality. He did not make gold, but instead succeeded in transmuting nitrogen into oxygen by bombarding nitrogen with alpha rays. He determined that the nucleus of hydrogen was an elementary particle, which he called the proton. Rutherford speculated that the nucleus also contains a neutral particle, the neutron, which was eventually confirmed in 1932 by his associate James Chadwick (1891–1974). Eventually the three types of nuclear radiation were identified as particulate: alpha rays are helium nuclei (a highly stable state of two protons and two neutrons); beta rays are electrons; gamma rays are very high-energy photons.

With the discovery of the neutron, all of matter could be described in terms of just four elementary particles. All the chemical elements and their compounds, which formed all the material substances known at that time, were composed of a tiny nucleus, made of protons and neutrons, surrounded by electrons. However, as we will see next, these electrons are no longer viewed as orbiting “planets” but rather as a diffuse cloud.

The fourth elementary particle known at that time was the photon. As already noted, the photon has zero mass but still carries energy and momentum. In 1916, Einstein showed in his general theory of relativity that the photon is acted on by gravity, another proof that it is material in nature. You just have to be careful to use the modified kinematical equations of special relativity when you are describing a photon's motion, since it travels at the speed of light.

THE BOHR ATOM AND THE RISE OF QUANTUM MECHANICS

In 1913, Niels Bohr (1885–1962) used Rutherford's atomic model to develop a quantitative theory of the simplest atom of all, hydrogen, which is composed of an electron in orbit about a proton. For simplicity, Bohr initially assumed the electron followed a circular orbit. However, the planetary model of the atom had a serious problem. According to classical electromagnetic theory, an accelerated charged particle will radiate electromagnetic waves and thereby lose energy. Since orbiting electrons continually change direction, they are accelerating and so will quickly spiral into the nucleus, collapsing the atom.

Bohr's solution was to hypothesize that only certain orbits are possible and that each orbit corresponds to a different, discrete “energy level.” In the lowest orbit, the electron has a minimum energy and cannot go any lower, thus making the atom stable. When the electron is in a higher orbit, it can drop down to a lower one, emitting a photon with energy equal to the energy difference between levels. In this way, only certain well-defined energies are emitted, giving the line spectrum of wavelengths that are observed.

To specify which orbits are allowed, Bohr made the following hypothesis: the angular momentum of the electron must be in integral multiples of h/2π.5 In physics, this quantity is called the quantum of action and is given the special symbol  , called “h-bar.” From this, Bohr was able to calculate the spectrum of hydrogen observed in spectrographic measurements. The theory was also applied to heavier atoms, called ions, in which all but one electron has been removed.

, called “h-bar.” From this, Bohr was able to calculate the spectrum of hydrogen observed in spectrographic measurements. The theory was also applied to heavier atoms, called ions, in which all but one electron has been removed.

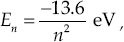

The energy levels of the hydrogen atom calculated by Bohr are where n is the orbital quantum number, with integer values 1, 2, 3, and so on. Note that En does not include the rest mass of the electron, as is the convention in nonrelativistic physics. The negative sign means that this much energy (|En|) must be provided to remove the electron from the atom. When an electron drops from a higher energy level to a lower one, the emitted photon has an energy equal to the energy difference between levels. This produces the emission spectrum. The absorption spectrum results when photons with an energy equal to the difference between two levels are absorbed by lifting electrons from lower to higher levels.

However, the Bohr model could not explain the Zeeman effect, which is the splitting of spectral lines that occurs when atoms are placed in a strong magnetic field. Bohr and Arnold Sommerfeld made the obvious improvement, allowing for elliptical orbits analogous to Kepler's planetary system. They also took into account special relativity. The new model was characterized by three quantum numbers:

| n = 1, 2, 3,… | orbital quantum number |

| l = 0, 1, 2, 3, n – 1 | azimuthal quantum number |

| m = –l, –l + 1, –l + 2,…, l – 2, l – 1, l | magnetic quantum number |

The orbital quantum number n is the same as in the Bohr model and in the absence of external fields; the energy levels are the same, depending only on n. The azimuthal quantum number l is a measure of the ellipticity or shape of the orbit; the smaller the value, the more elliptical. The l = 0 orbit goes in a straight line right through the nucleus and back. The magnetic quantum number m is a measure of the orientation or tilt of an orbit.

As a circulating charge, the electron produces a magnetic field that will be different for different orbital shapes and tilts. The spectral line shifts observed in the presence of external magnetic fields result from the interaction energies between the external field and the fields produced by circulating electrons in orbits with different tilts.

The Bohr-Sommerfeld model successfully described the Zeeman effect, but as experiments became increasingly refined, a “fine structure” of spectral lines was observed even in the absence of external fields that the model could not explain. In order to fit that data, the old quantum theory of Bohr and Sommerfeld and the planetary model was discarded and a new quantum theory was born.

ARE ELECTRONS WAVES?

Louis-Victor-Pierre-Raymond, 7th duc de Broglie (1892–1987), made the first step toward the new quantum theory in 1924. Although light had been shown to be composed of particulate photons, a beam of light still exhibited the diffraction and interference effects associated with waves. De Broglie noted that the wavelength associated with a photon with a momentum p is given by λ = h/p. He then conjectured that the same relation holds for electrons and other particles. That is, an electron of momentum p will have a “de Broglie wavelength,” λ = h/p.

In 1927, American physicists Clinton Davisson (1881–1958) and Lester Germer (1896–1971) ostensibly verified de Broglie's conjecture when they measured the diffraction of electrons scattering from the surface of a nickel crystal. Since then, diffraction has been observed for other particles such as neutrons and even large objects such as buckyballs, molecules containing sixty carbon atoms.6 In fact, every object—even you and I—has an associated wavelength. It's just too tiny to be observable for macroscopic objects because their momenta are so large.7

The wave-particle duality thus seems to hold for all particles, not just photons. However, as we will see, it is a mistake to think that an object is “sometimes a particle and sometimes a wave.” The wave nature that is associated with particles applies to their statistical behavior and should not necessarily be assumed to apply to individual particles. Neither photons nor electrons individually exhibit wavelike properties. Only beams of many of them do.

THE NEW QUANTUM MECHANICS

In 1926, Erwin Schrödinger (1887–1961) formulated a mathematical theory of quantum mechanics based on the classical mechanics of waves. He derived an equation that enables one to calculate a quantity ψ called the wave function for a particle of mass m, total energy E, and potential energy V. The wave function is a field with a value at every point in space and time. When E is positive, ψ is sinusoidal with a wavelength given by the de Broglie relation. However, it is important to remember that the wave function is not always in the form of a wave.

E can also be negative when the particle is bound, such as an electron in the hydrogen atom. Schrödinger was able to solve his equation for the hydrogen atom and obtain the same energy levels derived by Bohr.

The wave function in the Schrödinger equation is actually a complex number, so it has two values at each point in space-time—an amplitude A and a phase  . The equation itself is a partial differential equation utilizing mathematics that is taught at the undergraduate level and is familiar to any natural science, engineering, or mathematics major.

. The equation itself is a partial differential equation utilizing mathematics that is taught at the undergraduate level and is familiar to any natural science, engineering, or mathematics major.

However, Schrödinger was not the first to develop the new quantum mechanics. In the previous year, 1925, Werner Heisenberg (1901–1976) had proposed a formulation using less familiar mathematical methods than those used by Schrödinger. A few months later in the same year, Heisenberg, Max Born (1882–1970), and Pascual Jordan (1902–1980) elaborated on Heisenberg's original ideas utilizing matrix algebra, which is not terribly more advanced than partial differential equations. In 1926, Wolfgang Pauli (1900–1958) showed that matrix mechanics also yielded the energy levels of hydrogen.

In 1930, the two theories—Schrödinger wave mechanics and Heisenberg-Born-Jordan matrix mechanics—were shown by Paul Dirac (1902–1984) to be equivalent. Dirac's own version of quantum mechanics was based on linear vector algebra, which, while less familiar than Schrödinger's, is by far the most elegant and more widely applicable.8 In the Dirac theory, the quantum state of a system is called the state vector, and the wave function is just one specific way to mathematically represent the state vector. Neither Heisenberg's or Dirac's quantum mechanics is based on any assumptions about waves.

Let me give some more details on the nature of the solutions of the Schrödinger equation for the hydrogen atom. The mathematical form of the wave function depends on three quantum numbers:

| n = 1, 2, 3,… | principle quantum number |

| l = 0, 1, 2, 3, n – 1 | orbital angular momentum quantum number |

| m = –l, –l + 1, –l + 2,…, l – 2, l – 1, l | magnetic quantum number |

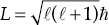

Note that the Bohr-Sommerfeld azimuthal quantum number has been renamed the orbital angular momentum quantum number. In the new quantum mechanics, the angular momentum L of an orbiting electron is quantized according to  while the magnetic quantum number gives the component of angular momentum along any particular direction you choose to measure it. Let's arbitrarily call that the z-axis. Then Lz = m

while the magnetic quantum number gives the component of angular momentum along any particular direction you choose to measure it. Let's arbitrarily call that the z-axis. Then Lz = m .

.

SPIN

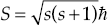

In 1925, Pauli made a further improvement to the atomic model when he proposed that electrons and other particles have an intrinsic angular momentum, called spin. He added a new spin quantum number s, where the spin S of a particle is given by  and its component along the z-axis is Sz = m

and its component along the z-axis is Sz = m . As with the magnetic quantum number m, ms ranges from –s to +s in unit steps. In the case of the electron s = ½ and ms = –½ or +½.

. As with the magnetic quantum number m, ms ranges from –s to +s in unit steps. In the case of the electron s = ½ and ms = –½ or +½.

Particles with half-integer spins are called fermions; those with zero or integer spins are called bosons. Pauli introduced what is now called the Pauli exclusion principle: only one fermion at a time can exist in a given quantum state. As we will see, this helped explain the periodic table of the chemical elements. The Pauli principle does not apply to bosons. Indeed, they tend to congregate in the same state, producing interesting quantum effects such as boson condensation.

At first, it was imagined that the electron was a solid sphere spinning about an axis. A spinning, charged sphere has a magnetic field caused by the circulating currents in the sphere. Furthermore, as we have seen in the Bohr-Sommerfeld model, the electron's motion around the nucleus also generates a magnetic field, so the two fields can interact with one another, producing a split in the spectral lines of an atom even in the absence of an external field. However, it turned out that the spinning sphere model of the electron gives a magnetic field for an electron that is too small by a factor of two.

With the discovery of electron spin, quantum mechanics moved into a new realm. Up to this point, quantum phenomena all had classical analogues, such as the planetary atom. Spin was a whole different animal with no classical analogue. Points don't spin. Quantum mechanics cannot be fully understood with images solely based on familiar experience. That does not mean, however, as is often thought, that quantum mechanics cannot be understood.

DIRAC'S THEORY OF THE ELECTRON

In 1928, Paul Dirac developed a theory of the electron that took into account special relativity. Remarkably, the spin of the electron did not have to be inserted manually, as with Schrödinger's and Heisenberg's nonrelativistic theories, but fell right out of the mathematics. So did the factor of two in the electron's magnetic field, as measured by what is called the magnetic dipole moment of the field, which was missing from the model of an electron as a spinning sphere.

With the Dirac equation for the electron, the detailed spectrum of hydrogen, as it was measured at the time, was fully described. However, just after World War II, in the aftermath of the Manhattan Project, incredibly precise experiments led to a theoretical breakthrough called quantum electrodynamics (QED). Quantum electrodynamics integrated Dirac's relativistic quantum mechanics into a new framework known as relativistic quantum field theory, which will be discussed in chapter 9.

Dirac's theory was even more world shaking than all that. It had negative energy solutions that he associated with antiparticles, in particular, antielectrons. These are partners of electrons that are identical in every way except their electric charges are opposite. In 1932, Carl D. Anderson (1905–1991) observed positive electrons in cosmic rays and dubbed them positrons. Earlier the same year, Chadwick had discovered the neutron, which, we recall, suggested that the physical world was composed of just four particles: the photon, electron, proton, and neutron. Now, a few months later, we had to add the positron. Eventually physicists would find antiprotons and antineutrons. The universe is simple, but not too simple.

The Dirac equation applies only to spin ½ fermions. However, other relativistic quantum equations were shortly developed for spin 0 and spin 1 bosons. These are all that are necessary for most purposes because all known elementary particles have either spin ½ or spin 1. As we will see, a spin 0 particle called the Higgs boson that is part of the so-called standard model of elementary particles and forces has now apparently been observed.

WHAT IS THE WAVE FUNCTION?

Relativistic quantum field theory is needed to understand the structure of matter at its deepest levels. The wave function that is prominent in the Schrödinger theory plays no important role in quantum field theory or in relativistic quantum mechanics. It is mentioned on only one page in Dirac's classic 1930 book, in a dismissive footnote:

The reason for this name [wave function] is that in the early days of quantum mechanics all the examples of these functions were in the form of waves. The name is not a descriptive one from the point of view of the modern general theory.9

However, Schrödinger wave mechanics remains in common use and is by far the most familiar to physicists, chemists, biologists, and others who work on lower-energy, nonrelativistic phenomena such as condensed matter physics, atomic and molecular chemistry, and microbiology. So, let us ask: What is this wave function? What does it mean?

No one has ever measured a wave function. Schrödinger thought that A2, the square of the amplitude of the wave function, gives the charge density of a system such as an atom. De Broglie proposed it was a “pilot wave” that guided particles in their motion.10 This view was developed further by David Bohm in the 1950s.11

But the interpretation of the wave function that caught on and is still accepted by the consensus was the one proposed by Max Born in 1926. Born hypothesized that the square of the amplitude of the wave function at a given point in space and time is the probability per unit volume, that is, the probability density, for observing the particle at that position and time. In this picture, the wave function is not some kind of waving field of matter any more than the electromagnetic field is a waving of the aether. It is a purely abstract, mathematical object used for making probability calculations. Furthermore, we no longer picture the atom as a submicroscopic solar system, but as a nucleus surround by a fuzzy cloud of electrons. Wherever the cloud is denser, the more likely an electron will be found at that point.

In this picture, the de Broglie wavelength is not, as usually described, the “wavelength of a particle.” More precisely, it is the wavelength λ = h/p of the wave function, the mathematical quantity that allows you to calculate the probability of a particle of momentum p being detected at a certain position at a certain time. Put another way, if you have a beam of many particles, each with a momentum p, it will behave statistically like a wave of wavelength λ = h/p, for example, by exhibiting diffraction, interference, and other wavelike behavior.

THE HEISENBERG UNCERTAINTY PRINCIPLE

In 1927, Heisenberg asked what would happen if you tried to measure with increasing accuracy the position of a particle. To do so, you would have to scatter light off the object with shorter and shorter wavelengths, or else diffraction effects would wipe out any position information.

Assume, for simplicity, that the light beam is monochromatic, that is, it has a well-defined wavelength λ. Heisenberg noted that, according to de Broglie, the light beam would contain photons of momenta p = h/λ. The shorter the wavelength, the higher will be the corresponding momentum.

When the photons scatter off the object in question, a good portion of their momenta will be imparted to the object, rendering its momentum increasingly uncertain. Heisenberg determined that the product of uncertainty in a particle's position Δx and the uncertainty (technically, the standard error) in its momentum Δp can never be zero. The product must always be greater than or equal to  /2.

/2.

In the case of an electron in an atom, if you tried to measure its position accurately within the atom, you would have to hit it with photons or other particles of such high momentum that they would likely kick the electron out of the atom. Hence, the electrons in an atom are best described as a cloud in which their positions are indefinite.

Now, you might say that the electrons still move around in definite orbits and we just can't measure them. This is an example of the new philosophical questions that arise in quantum mechanics. If you can't measure a particle's position accurately, does it “really” have a well-defined position? The answer seems to be no.

Take, for example, the way atoms stick together to form a molecule. Consider the simplest case, the hydrogen molecule composed of two hydrogen atoms. You can think of one atom being a positive H+ ion, which is simply a proton with the electron removed. This positive ion comes close to a negative H– ion, a hydrogen atom with an extra electron. The two will attract each other by the familiar, classical electrostatic force.

However, there is more to it than that. Because of the uncertainty principle, the electron's position cannot be measured with sufficient accuracy to determine which atom it is in. Thus, it is in neither—or both. This results in an additional attractive force called the exchange force that, like spin, has no classical analogue.

Now, if you persist in trying to understand quantum mechanics in terms of classical images, or worse, try to relate it to some ultimate “reality,” you have some work to do. How can the electrons be in both atoms at once? Once again, if we try to measure their position with, say, a photon of sufficiently high momentum, we will split the molecule apart. Is it proper to even talk about something you cannot measure? Just because you can't measure something, does that mean it can't be real? Why can't it really be real and we just can't measure it? The best answer we can provide is the one adopted by most physicists today: “Shut up and calculate.” We have a model that agrees with observations and enables us to make predictions about future observations. What else is needed?

Now, the above development of the uncertainty principle followed the traditional derivation as originally proposed by Heisenberg. However, the uncertainty principle can be shown to follow from the basic axioms of quantum mechanics.12

BUILDING THE ELEMENTS

The chemical elements were the atoms of the nineteenth century. Recall that I refer to them as chemical atoms, since they are now known not to be elementary but composed of nuclei and electrons. The number of protons in a nucleus of a given chemical atom is given by Z, where Z is the atomic number that specifies its position in the periodic table (see fig. 4.1). That is, each chemical element is specified by the number of protons in the nucleus of the corresponding chemical atom. An electrically neutral atom has Z electrons to balance the charge of the nucleus. If it has more than Z electrons, it is a negative ion; if it has fewer than Z electrons, it is a positive ion.

The number of neutrons in a nucleus is represented by N, so that the nucleon number of a nucleus is A = Z + N. The nucleon number is related but not exactly equal to the atomic weight that is usually given in tables of elements. The atomic weight is a measure of the total mass of an atom (atomic mass is a better term), including electrons, which is needed for quantitative chemical calculations. Usually (but not always) you can get the nucleon number by rounding off the atomic weight.

A given chemical element generally has nuclei with several different neutron numbers. These are called isotopes. For example, hydrogen has three isotopes: normal hydrogen, 1H1, with no neutrons; deuterium, 1H2, with one neutron; and tritium, 1H3, with two neutrons. In the notation I am using here (slightly unconventional), the subscript is Z. This is technically not needed since it is already specified by the chemical symbol, but I have included it for pedagogical purposes. The superscript is A. Since all isotopes of an element have basically the same electronic structure, they will have the same chemistry except for small differences that result from their masses being slightly different.

Starting with a single proton, we add an electron and get a hydrogen atom. That electron can be found in any of the allowed energy levels described above, depending on the principle quantum number n. The lowest level, with n = 1, is called the ground state. The higher energy levels are called excited states. When any atom is in an excited state, it will spontaneously drop to a lower level, emitting a photon with energy equal to the energy difference between levels. It will eventually end up in the ground state. For the rest of this discussion, let us just think about ground states.

If we add another proton to the nucleus, we get helium. Since two protons have the same charge, they will repel; so we will need some neutrons—which attract protons and other neutrons by way of the nuclear force—to help keep the nucleus together. (The nuclear force will be discussed in more detail in a later chapter.) For helium, 99.999863 percent of its isotopes are comprised of 2He4. The remainder occurring naturally is 2He3. Isotopes of helium from A = 5 to A = 10 have been produced artificially.

Let us focus on the electrons and not worry about the number of neutrons in the nucleus, which we saw has a generally small effect on chemistry.

Recall the Pauli exclusion principle, which says that two or more fermions cannot exist in the same quantum state. Since the electron has spin ½, it has two possible spin states. So both electrons can sit in the lowest energy level.

When we add a third proton to the nucleus, we get lithium. A third electron is needed for the neutral atom. However, that electron must go into the next higher energy level, or shell. That is, a shell is defined as all the electrons having the same principle quantum number, n.

Recall the quantum numbers, n, l, m, and ms, that specify an electron's quantum state. As we saw above, l has a maximum value of n – 1, m ranges from –l to +l, and ms is ±½. So when n = 1, only l = 0 and m = 0 are possible, so only two electrons can fit in the lowest shell. When we move to n = 2, we can have l = 0 and m = 0 as well as l = 1 and m = –1, 0, +1 possible. There is room for eight electrons in the second shell. I leave it for the reader to work out the number of allowed electron states in the third, n = 3, shell. The answer is eighteen. A little mathematics will show that the maximum number of electrons in the nth shell is 2n2.

We also define a subshell as the set of states with the same orbital quantum number l. The maximum number of states in the lth shell is 2(2l + 1).

So the periodic table is built up as electrons fill in the allowed states. Look again at figure 4.1. Note that the first row has two elements, H and He, filling up the first shell. The second row has eight, from Li to Ne, filling up the second shell. However, beyond the second shell, things get more complicated. The third row also has eight elements, and the fourth and fifth rows have eighteen, so the rows of the periodic table do not correspond simply to closed n-shells. Other effects beside the Pauli principle come into play.

For our purposes, we need not go into further technical detail. The basic point is that without the Pauli exclusion principle, the electrons in every atom would settle down to the ground state and we would have no complex chemical structures and a very different universe. It is hard to imagine that any form of life, which depends on complexity, could evolve in such a universe.

Another important point is that we can understand why some chemical elements are highly reactive, some mildly so, and some not reactive at all. It all depends on the most loosely bound electrons, the so-called valence electrons.

Let us examine the columns of the periodic table. In the first column, we have H, Li, Na, K, and other atoms with a single valence electron. This electron is very loosely bound and so can be easily shared with another atom. In the farthest-right column we have He, Ne, Ar, Kr, and other “noble elements” that have complete valence shells and their electrons are too tightly bound to be shared with other atoms.

Just to the left of these we have two columns of elements in which either one or two electrons are missing from a complete or “closed” valence shell. These atoms are happy to pick up an electron or two from other atoms and react with them. And so, for example, two hydrogen atoms readily combine with an oxygen atom to form H2O. The two hydrogen electrons are shared with the oxygen atom, thus closing its valence shell.

The Schrödinger equation can be written down for any multi-electron atom, although it cannot be solved exactly for any element above helium. Nevertheless, atomic physicists and chemists can use numerical techniques to calculate many important properties of the chemical elements. All the physics needed to understand the chemical elements is contained in that one equation, and there is very little mystery left in the chemical atom.