While Alexander’s presence at headquarters had been detrimental to the operations of the Russian armies, Napoleon’s absence from the front line was disastrous for the French. He had allowed himself to get bogged down with political and administrative concerns in Vilna, where he spent two precious weeks during which he effectively lost the initiative.

Having failed to trap and defeat Bagration, he now ordered Davout to keep alongside him and diverted Prince Eugène northwards in order to prevent the Second Army from joining up with Barclay’s First. This was being hotly pursued by Murat with his cavalry corps. Such a pursuit would in normal circumstances either have forced the Russians to face the French or turned their retreat into flight, but forced marches were something the Russian army was good at. In the event, Murat’s hot pursuit only contributed to the destruction of the Grande Armée’s cavalry, with catastrophic consequences later in the campaign.

This was not entirely Murat’s fault. In putting together a corps of 40,000 cavalry, Napoleon had created the greatest forage problem in the history of warfare. By giving the corps the role of a mobile spearhead, he condemned its stock to attrition. After a long day’s march, often involving skirmishes with cossacks or other units of the Russian rearguard, the men and horses would have to bivouac out in the open, with no shelter and often no food for the men or any kind of feed for the horses, which were lucky to get some old thatch pulled off a peasant hovel. In the morning they would be saddling and tacking up early for ‘la Diane’, a long stand-to while all the pickets came in and reported back, a rigmarole that could take up to a couple of hours. The long marches and the lack of rest meant that the horses suffered from saddle sores and other ailments as well as exhaustion, but these factors were aggravated by Murat himself.

Murat was one of the most colourful characters of his day. ‘He always wore grandiose or bizarre outfits deriving from the Polish and the Mussulman, combining rich cloth, striking colours, furs, embroidery, pearls and diamonds,’ wrote a contemporary. ‘His hair fell in long curls on his broad shoulders, his thick black sideburns and his sparkling eyes contributed to an ensemble which aroused astonishment and made one think of him as a charlatan.’ Determined to look his best on this campaign, Murat brought with him not only a variety of his operatic costumes but also, according to one of his officers, a whole wagonload of scents and cosmetics.1

Murat’s great virtues were his reckless bravery and his ability to inspire valour in his men. He thought nothing of standing under fire or leading charges, often disdaining to draw his bejewelled sabre and brandishing no more than a riding crop. But he had absolutely no tactical, let alone strategic, sense. He was the master of unnecessary and suicidal cavalry charges.

While he was a fine horseman, Murat showed a total lack of concern for the well-being of the beasts, which communicated itself to the generals serving under him, as a captain in the 16th Chasseurs à Cheval explained. ‘I will quote only one example among a host of similar ones,’ he wrote. ‘Sent off on picket duty with a hundred horsemen in the evening after the combat at Viasma, I was left at my post without being relieved until noon on the following day, and with strict orders not to unbridle the horses. The horses had been bridled since before six o’clock in the morning on the previous day. Having nothing for my pickets, not even water nearby, in the course of the night I sent an officer to explain my situation to the General, asking him for some bread and above all for some oats. He replied that he was there to make us fight, not to feed us. And so our horses went for thirty hours without being watered or fed. When I came in with my pickets it was time to move on; I was given one hour to refresh my detachment, after which I had to rejoin the column at a trot. I had to leave behind a dozen men, whose horses could no longer walk.’2

When he came across Murat’s cavalry on the march, barely three weeks into the campaign, Prince Eustachy Sanguszko, one of Napoleon’s aides-de-camp, noted that ‘the horses swayed in the wind’. Caulaincourt watched them skirmishing with the enemy rearguard at about the same time, and was shocked to see that after some of the charges the troopers were obliged to dismount and walk their horses back, and if there was a counterattack they had to abandon their mounts and save themselves by running, as they could do so faster than the exhausted creatures could carry them.3

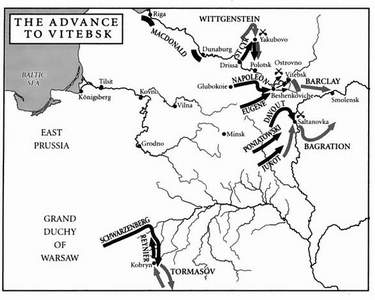

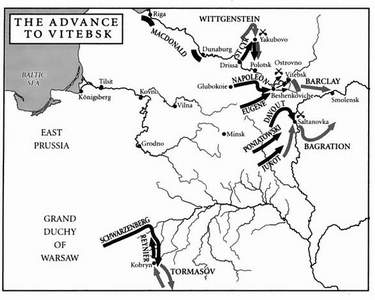

When Murat reported that Barclay had taken up position at Drissa, a new plan began to form in Napoleon’s mind. He would make for Polotsk, thereby turning Barclay’s left wing and cutting him off not only from Bagration but also his supply lines to the east. He would then attack and push him westwards towards the sea and into the path of the advancing corps of Oudinot and Macdonald. Leaving Maret in Vilna to manage his relations with the outside world, he set off in pursuit.

The Russians had indeed exposed themselves by wasting time at Drissa, and Napoleon’s plan would undoubtedly have culminated in the destruction of the First Army had it not been for his uncharacteristic lack of decision and speed. While the Russians were discussing the merits of Phüll’s position, he himself had been procrastinating in Vilna. On the very day he finally marched out, 16 July, the last units of the Russian army were evacuating the Drissa camp.

When Napoleon learned that the Russians had abandoned Drissa he amended his plan and made for Vitebsk rather than Polotsk, hoping to be able to outflank them there. But when he reached Beshenkoviche on 25 July he discovered that Barclay had slipped through ahead of him. Murat, leading the advance with his cavalry corps, had stumbled on his rearguard near Ostrovno. This time, the Russians stood and fought. Napoleon was delighted when he heard of this. ‘We are on the eve of great things,’ he wrote to Maret in Vilna, adding that he would soon be announcing a victory.4

Barclay appeared to have decided to give battle before Vitebsk. He had left Count Ostermann-Tolstoy with his 4th Corps of some 12,000 men barring the road at Ostrovno, with instructions to delay the French advance and win him time to deploy his forces. With his habitual impetuousness, Murat had launched his cavalry at the Russians. General Piré’s Hussars executed a brilliant charge in which they captured a Russian battery, and Murat himself led a couple of charges which pushed the Russians back in disorder. But he could not make any real headway against them, particularly when they took up positions in a wood, as he had no infantry or artillery to support him. That evening he was reinforced by the arrival of General Delzons’ infantry division, and the Russians were pushed back once more despite putting up a determined resistance.

This first serious engagement of the campaign had been the baptism of fire for many on both sides, and Lieutenant Radozhitsky of the Russian light artillery was horrified by the carnage. ‘My heart shuddered at such a sight,’ he wrote. ‘An unpleasant feeling took hold of me. My eyes grew dim, my knees gave way.’ Some of his old soldiers had told him that the fear would go once the waiting was over and they went into action, and he did indeed find that once he was firing off his guns at the French he felt only fury.5

The French felt an eerie sense of disappointment when they occupied Ostrovno that evening. ‘There was nobody who could pay to the courage of these soldiers the tribute of admiration which they had so richly deserved,’ wrote Raymond Faure, a doctor in the 1st Cavalry Corps. ‘There was not a table at which they could sit down and recount the exploits of the day.’

On the following morning Faure rode out onto the battlefield. ‘The sward was ploughed up and strewn with men lying in every position and mutilated in various ways. Some, all blackened, had been scorched by the explosion of a caisson; others, who appeared to be dead, were still breathing; as one came up to them one could hear their moans; they lay, some with their heads on the body of one of their comrades who had died a few hours before; they were in a sort of apathy, a kind of sleep of pain, from which they did not appear to wish to awake, paying no attention to the people walking around them; they asked nothing of them, probably because they knew that there was nothing to hope for.’6

The battle resumed that morning some eight kilometres to the east, as the Russians, who had been reinforced with Konovnitsin’s division and General Uvarov’s cavalry corps, fought to hold the French advance. They mounted a counterattack, sowing confusion in the French ranks, but the situation was redressed by a spectacular charge led by Murat in person. The charge was backed up by Delzons’ infantry, and the Russians were defeated. Only the timely arrival of reinforcements in the shape of General Stroganov’s division of grenadiers steadied their ranks and allowed them to retreat in good order.

Napoleon spent much of that night in the saddle, hurrying his forces forward, sensing the possibility of a battle. By midday on the following day, 27 July, he could see Barclay’s troops drawn up outside Vitebsk, behind the river Luchesa. The approaches to the river were defended by Count Pahlen’s cavalry corps, supported by infantry and cossacks, and Napoleon himself directed the operation of clearing them away, taking the opportunity to reconnoitre the Russian positions. The fighting was heavy. Many of Napoleon’s units were still coming up along the road, so he decided to put the battle off till the next morning. It was uncharacteristic of him, and it was also a grave mistake, for, as Yermolov’s aide-de-camp Lieutenant Grabbe pointed out, if he had pushed home his attack that evening, the Russians, who were also unprepared for battle, would have been routed.7

Napoleon was in the saddle until ten that night, directing the deployment of units as they arrived. Those that had already made camp were busily preparing for the next day. Days of battle were regarded as holidays, and as such demanded the finest turnout possible. The men unpacked their dress uniforms, polished the brass buckles and plaques, and pipeclayed the belts with an enthusiasm born of frustration. Everyone was looking forward to the battle, and none more so than Napoleon himself. There was no hiding his excitement as he bade Murat goodnight. ‘Tomorrow, at five o’clock. The sun of Austerlitz!’ he said, alluding to the magic moment, fixed in the memory of all those who had been there, when the sun broke through the morning mist on the day of the legendary battle.8

‘The men had spent the night preparing themselves, and on [28] July, the rising of a magnificent sun revealed us in the colourful dress of a parade,’ wrote Henri Ducor of the marine infantry. ‘Weapons glinted, plumes fluttered; joy and delight were visible on every face; the mood of gaiety was universal.’ But the gaiety turned to disappointment, then anger, and even a degree of despair when, as they marched out to take up their positions for battle, they realised that the enemy had vanished overnight.9 Napoleon was stupefied.

It is difficult to be sure whether Barclay had really intended to give battle. In his account of the campaign he maintains that he did. He had no more than about 80,000 men at his disposal, but he was only confronting the corps of Ney and Eugène, Murat’s cavalry and the Guard, rather than the whole of the Grande Armée, so although he would have been outnumbered, the disproportion would not have been that great. And he was under enormous pressure to fight. The murmuring against him and all the ‘Germans’ at headquarters had turned into open accusations of incompetence, cowardice and even treachery, and this was beginning to seep down to the ranks. ‘I beg Your Majesty to rest assured that I will allow to pass no opportunity to harm the enemy,’ he wrote to Alexander on 25 July as he began taking up position at Vitebsk, ‘nevertheless, the most thorough regard for the preservation and security of the army will remain an inseparable element of my efforts against the enemy forces.’10

This last phrase suggests that Barclay was open to any excuse not to fight, and on the afternoon of 27 July, while the two armies were skirmishing and just before Napoleon decided to adjourn the battle to the morrow, he was handed one. A courier arrived from Bagration informing him that the Second Army had failed to break through to Orsha, from where it could have come to his aid. It had found its path blocked at Saltanovka by Davout who, although greatly outnumbered, had beaten it back on 23 July, forcing it to wheel south. This meant not only that Bagration would not be able to come to the support of Barclay, which the latter must have known anyway, but, as Barclay did not hesitate to point out, that even if he scored a victory over Napoleon at Vitebsk he would have Davout’s corps (whose strength the Russians consistently overestimated) in his rear, and when he turned about to defeat this he would have Napoleon, at best beaten but not routed, in his rear. He therefore took the only sensible course. He let Napoleon believe he would fight, and slipped away quietly as soon as darkness fell, leaving only a skeleton force of cossacks to keep the campfires burning.11

This was not the result of some new plan to draw the enemy into Russia, but of dire necessity. ‘I cannot deny that although many reasons and circumstances at the beginning of military operations made it necessary to abandon the frontiers of our land, it was only with the greatest reluctance that I was obliged to watch as these backward movements continued all the way to Smolensk itself,’ Alexander wrote to Barclay a couple of weeks later. And Smolensk was the very furthest fallback position contemplated.12

Barclay did the right thing. If he had stood and fought, he would almost certainly have been defeated, and that would have entailed the loss of, in Alexander’s words, the only army he possessed. In the highly unlikely event that Barclay had won, the victory would not have been a decisive one, as it would only have defeated part of Napoleon’s forces, and it would not have expelled the French from Russia. Finally, robbing Napoleon and his army of the chance of a fight had a negative effect on their morale, and it was in very low spirits that they took possession of Vitebsk on 28 July.

The men were at the end of their endurance. They had been on the march for up to three months, and some, like one regiment of flankers of the Young Guard made up of youths barely out of school, had come all the way from Paris with only a single day’s rest at Mainz and another at Marienwerder. Some units were marched for thirty-two hours at a stretch, with only a couple of hours’ rest in brief intervals, covering as much as 170 kilometres. Carl Johann Grüber, a Bavarian cuirassier officer, recalled that his men were so tired after some of the marches that ‘hardly had the cry of “Halt!” rung out, than they fell to the ground and into a deep sleep without even bothering to cook up the slightest meal’. And even if they were not moving out early in the morning, they had to go through the tedious ritual of ‘la Diane’.13

As they moved from Germany into Poland the quality of the roads declined, and when they crossed the Niemen these turned into troughs of sand or mud, according to the weather. Wading through either required twice the effort of marching along a firm road. The terrain between the Niemen and the borders of Russia proper is wooded and boggy in places. It is cut across by a multitude of small rivers, many of which trickle along the bottom of deep ravines. Existing bridges often consisted of no more than a few tree trunks, so if the sappers were not at hand, infantry, cavalry, artillery and supply wagons had to tumble down into the ravines and scramble up the other side.

Where they ran into woods, the tracks often became so narrow that infantry had to break ranks, while caissons and guns got jammed. Cavalry had to contend with low branches, which were a particular menace to those, like the Italian Guardia d’Onore, whose tall Roman-style helmets seemed made to catch on them. ‘Many riders who had fallen asleep in the saddle out of sheer exhaustion hit their heads on the branches,’ recorded Albrecht Adam, an artist who accompanied the staff of Prince Eugène on campaign. ‘Their helmets either fell off or hung lopsidedly by the chinstraps, and several of the men tumbled to the ground.’14

The sheer volume of traffic on these country roads and tracks ground the dust finer and churned the mud to its most viscous. It also caused jams, delays, arguments over precedence, and sometimes fights. A gun team which had to stop in order to repair a piece of harness or tend to a lame horse would lose its place and then have to literally fight against infantry units unwilling to let it back into the stream of traffic, with the result that it would get cut off from its battery and might not be able to rejoin it for a day or more. And the multinational make-up of the army meant that arguments over precedence could turn ugly.

Seasoned soldiers were used to hardship, and needed to be, as marching for hundreds of miles burdened with a heavy backpack, a full cartridge case, a sword and a musket was no picnic. But none of them could remember as difficult and painful a march as this. By the middle of July most of the footsoldiers were barefoot, as their boots had fallen to pieces, and even the proverbially jolly French infantrymen had stopped singing their songs as they marched.

In France, Germany, Italy and even Spain, troops would be found billets in towns and villages on the march, and only had to bivouac out in the open on the eve of battle. But there could be no question of lodging anyone in the miserable villages of eastern Poland and Russia. The troops had not slept under any kind of cover since crossing the Niemen five weeks before, as they hardly ever had the time to construct shelters out of branches and whatever else came to hand. Prescient officers had had canvas sleeping bags run up for themselves, but their men had only their greatcoats to sleep under. The young recruits, away from home for the first time, adjusted particularly badly to this.

On warm summer evenings a bivouac could be a pleasant experience, with either some of the regimental bandsmen or odd strummers playing music and the men smoking their pipes as they chatted by the fireside. That is certainly how it struck the nineteen-year-old Baron Uxküll, an officer in the Russian Imperial Guard. ‘What a sight tonight!’ he wrote in his diary on 30 July. ‘Imagine a dense forest that had taken in two cavalry divisions beneath its majestic, bushy roof! The campfires, now gleaming brightly, now dying down, could be seen burning through the foliage their heat kept agitating; at every moment they revealed to astounded eyes groups of men sitting, standing, and lying down around them. The confused noise of the horses and the axe strokes that were cutting away to feed the fires, all this added to the blackest night I’ve ever seen in my life – created, in fact, an effect that was as novel as it was bizarre; it resembled a magic tableau. I thought involuntarily of Schiller’s The Robbers and of mankind’s primitive life in the forest.’ It is worth noting that this particular young man had set off to war with Madame de Staël’s Delphine and the poems of Ossian in his saddlebag.15

He omits to mention the swarms of mosquitoes that tormented the men in the predominantly marshy areas they were marching through, or the fact that, as often as not, they had nothing to eat as they sat around their campfires. The sweltering heat of the July days was frequently followed by bitterly cold nights, and they sometimes had to lie down to sleep under torrential rain. ‘The rain and the cold of the night meant that we had to keep campfires burning all night in front of the shelters,’ recalled another Russian officer. ‘The smoke from the damp brushwood, mixed with that of tobacco from the men who smoked, stung our eyes and tickled our throats, making us weep and cough.’16 Even in summer there is dew, so their clothes were invariably damp when they rose; some never did, having died of hypothermia in the night.

Because of the forced marches they usually stopped for the night quite late, and instead of being able to rest had to busy themselves making fires, gathering supplies and cooking something to eat. ‘It was, to my mind, the hardest part of this campaign,’ recalled the Comte de Mailly, an officer in the Carabiniers à Cheval. ‘Imagine what it was like for us, after having marched ten leagues, in atrocious heat, with a helmet and cuirass, and often without having had enough to eat, to start killing a sheep, skinning it, plucking geese, making the soup, and keeping the fire going so as to roast what we would eat or take with us for the next day.’17

Often they had nothing with them, and had to send out men to forage in the locality. By the time these returned with victuals, or the regimental supply wagons rolled up, the men had fallen asleep, so they would take it in turns to cook the food while most of them slept, and the men would eat their dinner before setting off in the morning. This meant that they had to wolf it down in a hurry; sometimes, if there was an alarm or an order to move out urgently, they had to leave it behind uneaten.

The sheer misery comes through the pages of the journal kept by Giuseppe Venturini, a Piedmontese conscript. ‘Horrible day!’ reads the entry under 20 July. ‘Bivouacked in the mud, thanks to our two cretinous generals. Ditto on the 21st, 22nd, 23rd. On the 24th, in a nice meadow. I felt as though I was in a palace. I was on sentry duty at General Verdier’s. I was lucky that day; I ate a good soup. On the 26th six men died of hunger in our regiment.’18

Hunger was the worst affliction of all. ‘You who have never felt the pangs of hunger, you whose palate has never been parched by thirst, you do not know what real need is, a need which never lets up for an instant, and which, only partly satisfied, becomes all the more urgent and more acute,’ wrote one of the paymasters in Davout’s 1st Corps. ‘In the midst of the great events which unfolded before my eyes, one dominant thought preoccupied me: to eat and to drink, that was my only goal, the nub around which my whole mind was concentrated.’19

The regimental supplies carried on wagons and the herds of cattle driven along in the wake of the advancing troops inevitably fell behind if the tempo of the march quickened, and in many cases they were three or four days behind. As a result, regular distributions of rations rarely, if ever, took place. Major Everts of Rotterdam, serving in Davout’s corps, noted that his men had not had a crust of bread for thirty days when they reached Minsk. Captain François of the 30th of the Line claims that outside Vilna they received two rations of mouldy bread, the only such distribution during the entire campaign. These were not isolated experiences. ‘As soon as we had crossed the Vistula all regular supplies and normal distribution of food ceased, and from there as far as Moscow we did not receive a pound of meat or bread or a glass of brandy through orderly distribution or normal requisitioning,’ reported General von Scheler to the King of Bavaria.20

Ultimately, it was down to the men to find something to eat and to prepare it themselves. The most resourceful were, by all accounts, the French and the Poles, who procured – by purchase or looting – cooking pots and utensils, and knew how to make out of the most unpromising raw materials a dish that would at least lull the stomach even if it did not nourish. They were also, according to General von Scheler, better at bringing in supplies. They would find what they needed quickly and bring it straight back to the unit for all to share; if everyone did this there would be plenty to go round. Scheler’s Bavarians were slow off the mark, and if they found something to eat would set about filling their own bellies. They would only then try to rejoin their unit with the rest of their booty, by which time it would have moved off and they would either have to jettison their load or fall behind for good.21

But necessity is a great instructor, and Jakob Walter of the Württemberg division in Ney’s corps soon learned how to find the jars of pickles, the barrels of stewed cabbage, the honey, potatoes and sausages hidden under floors and piles of wood or buried in the orchards of deserted and apparently devastated villages. ‘Here and there a hog ran around and then was beaten with clubs, chopped with sabres and stabbed with bayonets,’ he wrote, ‘and, often still living, it would be cut and torn to pieces. Several times I succeeded in cutting off something; but I had to chew it and eat it uncooked, since my hunger could not wait for a chance to boil the meat.’22 Eating undercooked pork is notoriously dangerous, but even without that, the diet they were subjected to, rich in meat but poor in bread, rice and vegetables, upset their stomachs and made them prone to diarrhoea and dysentery.

Near Korytnia, Murat’s corps moved into a camp recently vacated by the Russians. ‘The shelters constructed out of branches were still standing, the fires were only just extinguished,’ noted an officer in the Lancers of Berg. ‘Behind this camp was a ditch in which the soldiers had gone to satisfy their natural needs, and I noted the considerable volume of the piles of excrement with which this area was covered, and came to the conclusion that the enemy army had been abundantly fed.’ Heinrich von Roos noted that on coming upon a recently vacated encampment, the surest way of telling whether its last occupants had been friend or foe was to seek out the latrines, explaining that ‘the excreta left behind by men and animals on the Russian side testified to a good state of health, while ours showed in the clearest possible way that the entire army, horses as well as men, was suffering from diarrhoea’.23

Thirst also tortured them all from the moment they crossed the Niemen. Daytime temperatures reached 36°C (97°F), and many of those who had campaigned in Egypt claimed they had never marched in such heat.* On 9 July the 11th Light Infantry lost one officer and two men to heatstroke. ‘The air along the wide sandy tracks running through endless dark pinewoods was really like an oven, so oppressively hot was it and so unrelieved by the slightest puff of wind,’ recorded a Russian cavalryman retreating before them. The occasional downpour would drench them without refreshing them or the country they marched through, and steam would rise from their uniforms while the water seeped into the sandy soil. Due to the sparseness of the population there were few wells, and the ponds and ditches contained only brackish water. The men would dig holes in the ground and wait for them to fill with water, but it was so full of worms that they had to filter it through kerchiefs before they could drink it. One of Berthier’s staff officers had equipped himself with his own cow and a range of essences, and was able to treat his colleagues to ice cream, but the rank and file on the march had to make do with what was to hand. ‘How many times did I not throw myself down on my belly in the road to drink out of the horsetracks a liquid whose yellowish tinge makes my stomach heave today,’ recalled Henri Ducor, and he was certainly not the only one to drink horse’s urine out of the ruts in the road.24

Not surprisingly, many died of dehydration or malnutrition. Others got dysentery. The German contingents seem to have been most vulnerable. Their men were less resourceful than the French and others at building shelters, harvesting crops, grinding corn, baking bread or making up a pottage of whatever was going. The Württembergers suffered particularly badly from dysentery – Carl von Suckow’s company had dwindled from 150 to just thirty-eight, without having so much as seen the enemy – and the Crown Prince himself became so ill that he had to leave the army. The Bavarians also suffered badly, and by the time their contingent of 25,000 men reached Polotsk it was down to 12,000. The Westphalians succumbed to the heat in droves. At the end of a forced march in a temperature of over 32°C (90°F) one regiment was down to 210 men out of a complement of 1980.25

The more resilient simply suffered from diarrhoea and soldiered on, clutching their bellies and making sudden dashes to the side of the road to drop their pants. This was more than a nuisance to Aubin Dutheillet de la Mothe, a twenty-one-year-old officer in General Teste’s brigade. At one point he felt such an urgent need to defecate that he rode off the road, dismounted and dropped his breeches without pausing to tether his horse. As he squatted helplessly a squadron of cuirassiers clattered by and his own mount trotted off with them, bearing his sabre and much of his kit, never to be seen again.26

The roadside was littered not only with excrement, but with the carcases of horses and the bodies of men who died on the march. ‘On some stretches of the road I had to hold my breath in order not to bring up liver and lungs, and even to lie down until the need to vomit had died down,’ wrote Franz Roeder, a Hessian Life Guard officer.27

The horses too were having a terrible time of it. Unused to the kind of diet they were being subjected to, they suffered from colic and diarrhoea or constipation. One artillery officer recorded that he and his men would have to plunge their arms up the poor creatures’ anuses up to the elbow in order to pull out rock-hard lumps of dung. Without such attentions, their stomachs would blow up and explode.28

As they were continually in action, the horses had also developed saddle sores. ‘Entire columns consisting of hundreds of these poor beasts had to be led along in the most pitiful condition, with sores on their withers and backs stopped up with bits of hemp and dripping with pus,’ noted a witness. ‘They had lost so much weight their ribs stood out and they presented a picture of the most abject misery.’ As the fine-bred creatures brought from France and Germany died they were replaced with whatever the country could offer, which for the most part were shaggy little peasant horses known throughout the army as ‘cognats’, from ‘kon’, the Polish for horse.29

To the discomforts of the march have to be added the swarms of vicious wasps, horseflies and mosquitoes that are a feature of summer in that part of the world, and the terrible clouds of dust churned up by the men and horses as they marched. ‘The dust on the roads was so thick that whether a horse be a bay or a grey it was the same colour, and there was no difference in the colour of the uniforms or of the faces,’ recorded a lieutenant in the 5th Polish Mounted Rifles. The dust was so thick in places that infantry had to have the drummers beating constantly at the head of every company, so they did not lose their way.30

When they could see around them, they were confronted with an empty, desolate landscape stretching away into the unknown. Towns and villages were few and far between, and most were devastated by the passage of troops. ‘What I have seen in the way of distress in the past two weeks is beyond description,’ the artist Albrecht Adam wrote to his wife. ‘Most of the houses are deserted and without roofs. In the areas we are marching through most of them have thatched roofs, and the old straw from these has been used as fodder for the horses. The houses have been destroyed or ransacked, and the inhabitants have fled, unless they are so poor that they have died of hunger, having had all their food taken away by the soldiers. The streets are strewn with dead horses which give off an awful stink in the hot weather we are having, and every moment more horses collapse. It is a horrible war. The campaign of 1809 seems like a pleasant promenade by comparison.’31

The population, such as it was, shocked the French and their allies by its abject poverty and backwardness. The Jews, who were such a dominant feature of every town and village in these former Polish lands, revolted the troops and brought out all their innate prejudice as they surrounded them to buy, sell or barter. ‘If you knew the countryside through which we are wandering, my dear Louise,’ General Compans wrote to his young bride, ‘you would know that nothing in it is beautiful, not even the stars, and that if one were to try and form a harem of four wives for a sultan here, one would have to tax the entire country.’32

Another factor, enervating as well as striking by its novelty, was the shortness of the summer nights this far north. ‘Many times when we went into bivouac for the night, the great glow of the sun was still in the sky so that there was only a brief interval between the setting and the rising sun,’ wrote Jakob Walter from Stuttgart. ‘The redness remained very bright until sunrise. On waking, one believed it was just getting dark, but instead it became bright daylight. The night-time lasted three hours at most, with the glow of the sun continuing.’33

Whether they came from Germany or Portugal, the troops felt very far away from home, and their anxiety grew with every step further they took. Such feelings were particularly strong among the young recruits, but even the old soldiers later reflected that the advance into Russia had been in some respects worse than the notorious retreat. Some deserted and headed back homeward. Hundreds committed suicide. ‘Every day one heard single shots coming from the woods lining the road,’ recalled Carl von Suckow. A patrol would be sent out to reconnoitre and would return with the report that a man had shot himself. And it was not just unhappy recruits who took their lives. On 14 July Major von Lindner of the 4th Bavarian infantry cut his throat with a razor from despair.34

According to the commissaire des guerres Bellot de Kergorre, the whole army had been reduced by a third by the time it reached Vitebsk, without fighting a single battle. The Legion of the Vistula had lost between fifteen and twenty men in every company. ‘In a normal campaign,’ explained one of its officers, ‘two proper battles would not have managed to reduce our effectives to such an extent.’ The Army of Italy was down by one-third overall, though some units were even more depleted – one had lost 3400 out of a total of 5900 men. Ney’s 3rd Corps was down from 38,000 to 25,000.35

The German contingents had suffered more than most. ‘The food is bad, and the shoes, shirts, pants, and gaiters are now so torn that most of the men are marching in rags and barefoot. Consequently, they are useless for service,’ General Erasmus Deroy reported to the King of Bavaria. ‘Furthermore I regret to have to tell Your Majesty that this state of affairs has produced a serious relaxation of discipline, and there is such a widespread spirit of depression, discouragement, discontent, disobedience, and insubordination that one cannot forecast what will happen.’36

But the worst affected were Poniatowski’s Poles and the West-phalians, now under the command of General Junot, whose march had taken them through the most desolate areas and who, because they had been set in motion after the main force of the Grande Armée, had been obliged to make up for lost time when Napoleon changed his plans and gave them the job of chasing Bagration.

Ironically, the losses in men were in fact beneficial to the Grande Armée. The ranks had been cleared of the weakest, who should never have been sent off to war in the first place. But before they died they had helped to slow down the operations of the army, to ravage the country through which they passed and to overload the supply machine to an extent from which neither recovered. And the sight of them dying in their thousands had an unsettling effect on those who remained.

Napoleon was usually very active when on campaign. He was always up by two or three o’clock in the morning and never retired before eleven at night. He ranged all over the theatre of operations, travelling in his carriage so he could work, and mounting one of his saddle horses which were led along behind in order to go and reconnoitre a position or inspect some troops. His aides-de-camp, who had to ride behind his carriage and often did not have a spare horse to hand, would have trouble in keeping up with him as he galloped off.

But the sheer size of the Grande Armée at the outset of this campaign and its wide dispersion in so many corps meant that Napoleon never saw most of his troops, on the march or at bivouac, as he usually did. As a result he did not see the condition or catch the mood of the army, and the men did not feel his presence and commitment in the way they had grown used to. He studied lists and figures, many of them wildly inaccurate, and optimistic reports from unit commanders eager to please. General Dedem de Gelder noted that when reporting their numbers, all the commanders inflated the figures in order to make themselves look good, and according to his calculations Napoleon must have thought he had about 35,000 troops more than he did at this stage.37

Napoleon only saw his troops when they were in action or on parade before him, when, buffed up and motivated, they looked and felt their best. He therefore tended to disregard the occasional honest reports on their condition that did reach him, and as he did not like to hear them, dismissed them as exaggerated scaremongering. Had he taken a closer look, he would have seen that the situation called for some urgent reorganisation.

Murat’s huge cavalry formation had outlasted its usefulness, since it performed no real military purpose and was incapable of feeding itself. The cavalry would have found it much easier to feed its horses and would have been of far more use if it had been broken down into brigades and divisions and dispersed among the various corps.

It had also become obvious to most of the commanders on the ground that the artillery could have done with some weeding. The Russian artillery was not only of a very high standard, it also used guns of greater calibre, which meant that the dozens of light field pieces being dragged along by the French were largely useless. Napoleon had given every infantry regiment its own battery of four-pounders, primarily for psychological effect. They could hold their own in skirmishes between small bodies of troops, but not in a set-piece battle in which the Russian artillery was deployed. But their presence required a vast amount of effort, thousands of horses and tons of fodder. Many had been left behind along the way, at Vilna and elsewhere, for lack of draught animals, but they were all laboriously dragged up as soon as possible instead of being abandoned.

According to some sources, on entering the rooms which had been prepared for him in Vitebsk, Napoleon took off his sword and, throwing it on the table covered with maps, exclaimed: ‘I am stopping here; I want to take stock, rally and rest my army, and to organise Poland; the campaign of 1812 is over! The campaign of 1813 will accomplish the rest!’ Whether the scene was quite as theatrical as this is questionable, but the gist of what he said is not. He told Narbonne that he would not repeat the mistake of Charles XII by venturing deeper into Russian lands. ‘We must settle down here this year, so as to finish the war next spring.’ And to Murat he is reported to have said that ‘the war against Russia will be a three-year war’.38

Napoleon had taken his quarters in the residence of the Governor of Vitebsk, the Tsar’s uncle Prince Alexander of Württemberg, and there he installed his travelling office, with his portefeuille and boxes containing papers as well as a couple of long mahogany cases with his travelling library. Presumably alarmed at the thought of the longueurs that lay ahead, he wrote to his librarian in Paris asking him to send ‘a selection of amusing books’ and novels or memoirs that made for easy reading. The weather was extremely hot, with temperatures of 35°C (95°F) at night recorded by his secretary Baron Fain, and while his troops cooled themselves by bathing in the river Dvina, he sweated as he worked at tidying up the army. He gave orders for a new route of communication and supply to be opened via Orsha to Minsk, instructed General Dumas to start building up a sizable magazine and to construct bread ovens, and he set up a local administration. He bought and demolished a block of houses in front of his quarters in order to create a square on which he could review his troops, and held regular parades, knowing this to be good for the soldiers’ morale. He was aware that they were grumbling about the supply situation, so he used one of these parades, on 6 August, to vent his anger publicly at the commissaires and those in charge of the medical service. Shouting loud enough for the soldiers to hear, he reproved them for failing to comprehend ‘the sanctity of their mission’, sacked the chief apothecary and threatened the doctors that he would send them all back to treat the whores of the Palais-Royal. It was pure theatre, but the soldiers cheered their Emperor who cared so much for them.39

Napoleon issued confident-sounding and mendacious Bulletins, wrote to Maret instructing him to publicise non-existent successes, and blustered in front of the men; but in the privacy of his own quarters he was irritable and often in a bad mood, shouting at people and insulting them in a way he rarely did. He made contradictory statements and appeared at a loss as to what to do next.

His instinct was to pursue the Russians and force them to fight. He had nearly managed it at Vitebsk, and felt sure they would make a stand in defence of Smolensk, a larger city of some moral significance to them. There was no logic whatever in stopping at Vitebsk while there was still an undefeated Russian army in the field. For one thing, he would quickly starve. He had reached a more fertile area, but the country would still not be capable of feeding his army over a long period of time, while supplying it from Germany was not realistic. He could hardly go into winter quarters in July, and he was the first to see that this was not a good position, since the rivers that provided some kind of defence in summer would freeze over in winter, making it highly vulnerable.

The wider strategic situation was problematic. On Napoleon’s northern flank, Macdonald was besieging Riga and Dunaburg. Oudinot, after an inconclusive engagement against Wittgenstein at Yakubovo which both sides claimed as a victory, had fallen back to cover Polotsk, where he was reinforced by St Cyr’s 6th corps. In the south, General Reynier’s Saxons had suffered a minor defeat at the hands of Tormasov near Kobryn, but he and Schwarzenberg had then pushed Tormasov back, clearing the Russians out of Volhynia entirely.

It was high time he made a decision on whether to play the Polish card or not. He had been greeted in Vitebsk by delegations of local Polish patriots, and had evaded their expectant questions as to his intentions by heaping abuse on Poniatowski and the alleged cowardice of the Polish troops, which, he claimed, was largely responsible for the failure to catch Bagration. ‘Your prince is nothing but a c—,’ he snapped at one Polish officer.40

From Glubokoie he had written to Maret telling him to instruct the Polish Confederation in Warsaw to send an embassy to Turkey with the request for an alliance. ‘You realise how important this démarche is,’ he wrote. ‘I have always had it in mind, and cannot imagine how I forgot to instruct you accordingly.’ Poland and Turkey were united in enmity to Russia, and Turkey had never reconciled herself to the removal of her ally from the map. A firm declaration of intent by Napoleon to restore Poland might well have persuaded Turkey to resume her war with Russia.41

Many argued that this was the moment to send Poniatowski south into Volhynia. This would have raised an insurrection in the whole of the old Polish Ukraine, which would have yielded men and horses in plenty as well as abundant supplies. More important, it would have tied down all the Russian forces in the south, under Chichagov and Tormasov, neutralising any threat they might otherwise pose to Napoleon’s flank. But a few days later, from Beshenkoviche, he wrote to Reynier leaving it up to him whether to encourage the local Poles to rise against the Russians.42

In the event, Reynier’s Saxons behaved so badly that they aroused hostility among even the most patriotic Poles in the area. Those who had hoped that Napoleon might restore Poland were disenchanted. ‘The mask of his good intentions towards us was beginning to slip,’ in the words of Eustachy Sanguszko, one of his aides-de-camp. For his part, Napoleon told Caulaincourt that he was disappointed by the Poles, and that he was more interested in using Poland as a pawn than in restoring her independence.43

While at Vitebsk he received news of the ratification of the treaty of Bucharest between Russia and Turkey, and details of that between Russia and Sweden signed in March. What he did not know was that Russia had also signed a treaty of alliance with Britain on 18 July. From Berlin he was receiving intelligence that the British were planning a joint landing in Prussia with the Swedes. But he was cheered by the news of the outbreak of war between Britain and the United States of America.

‘While the Emperor meditated on new and more decisive blows, a great cooling off was taking place around him,’ according to Baron Fain. ‘Two weeks’ rest gave people time to reflect on the enormous distance at which they found themselves, and on the singular character which this war was assuming.’ He added that there was ‘anxiety and discouragement’ in the various staffs. Napoleon sensed this, and for the first time he drew a wider group of generals into his confidence, asking them what they thought should be done. Berthier, Caulaincourt, Duroc and others felt it was time to call a halt. They cited losses, provisioning difficulties and the length of the lines of communication, and expressed the fear that even a victory would cost them dear, on account of the lack of hospitals and medical resources.44

But Napoleon clung to his original assessment. The Russians were now stronger than they had been, and were on the borders of Russia proper, so they were more likely to accept battle – and that was what he staked everything on. ‘If the enemy holds at Smolensk, as I have reason to believe he will, we shall have a decisive battle,’ he wrote to Davout. Once he had defeated them, Alexander would sue for peace, and the Russians would furnish him with all the supplies he needed. ‘He believed in a battle because he wanted one, and he believed that he would win it because that was what he needed to do,’ wrote Caulaincourt. ‘He did not for a moment doubt that Alexander would be forced by his nobility to sue for peace, because that was the whole basis of his calculations.’45

But Napoleon remained agitated, as Narbonne’s diary shows, for he was far too intelligent not to see the truth of all the arguments against proceeding. This proverbially decisive man seemed panicked by the very fact that he could not reach a decision, and, leaping out of his bath at two o’clock one morning, suddenly announced that they must advance at once, only to spend the next two days poring over maps and papers. ‘The very danger of our situation impels us towards Moscow,’ he said to Narbonne finally. ‘I have exhausted all the objections of the wise. The die is cast.’46

* All temperatures recorded during this campaign were in Réaumur. For the reader’s sake I have converted them into Celsius and Fahrenheit throughout.