‘The greatest regret in my life,’ Alexander’s sister Catherine later said, ‘is not having been a man in 1812!’1 Had she been one, she might well have ended up in his place. Alexander knew that as the Russian armies fell back, allowing the French invaders to strike into the very heartlands of the empire, he would be blamed. And he could not forget what had happened to his father and grandfather. Arakcheev, Balashov and Shishkov had convinced him that he must galvanise Russia and rally it to his cause. But he could not be sure which way his subjects would swing, particularly as many of them had only become his subjects as a result of conquest.

The territory occupied by the French thus far had only been part of the Russian empire for between seventeen and fifty years, and Alexander could not expect much devotion to the cause of the Tsar and fatherland from the preponderantly Polish gentry or the mass of peasants, who had no defined sense of nationhood. Nor could he play the religious card there: in the areas acquired by Russia in 1772, the population consisted of 1,500,000 Uniates and 1,300,000 Catholics, 100,000 Jews, 60,000 Old Believers, 30,000 Tatar Muslims and three thousand Karaim Jews, as against only 80,000 Russian Orthodox. And even some of these were not reliable. Varlaam, Orthodox Archbishop of Mogilev, went so far as to swear an oath of allegiance to Napoleon, encouraging his flock to do likewise and attend services in the Emperor’s honour. The Russian troops considered the locals to be foreign and ill-disposed to Russia, and while they maintained amicable relations with them during the eighteen months or so they had been posted there, they began plundering manors and villages as they withdrew.2

In the event, most of the Polish nobility opted for Napoleon in principle, though the majority did so without much enthusiasm, and many adopted a wait-and-see attitude. The peasants seem to have reacted in more pragmatic ways. Some took the opportunity to rebel, or at least to refuse to carry out their labour obligations. Others apparently made a run to freedom: in 1811 the administrative regions of Mogilev, Chernigov, Babinovitse, Kopys and Mstislav contained 359,946 serfs belonging to landowners and the Church; in 1816 there were only 287,149 of them.3

The Russian authorities were nervous of how the Jews would react, since they represented the only group in this area, apart from the Polish nobility, who could have been of use to the French in administering it. Napoleon had emancipated the Jews in every country he had marched through, and in 1807 he had called a Grand Sanhedrin or gathering to which he had invited Jews from all over the world. In the event, many Jews did make themselves useful to the French as traders, as guides, and sometimes as informers. But most remained indifferent, while a number proved surprisingly loyal to the Tsar.4

In the Russian heartlands, which the French were now entering, there were none of these alien elements (the Jews were banned from them), but this did not make the authorities any less apprehensive. In what seems a chillingly modern kind of operation, the police in the province of Kaluga rounded up its foreign residents – Frenchmen, Germans, Swiss, Danes, Englishmen, a Dutchman, a Pole, a Spaniard, a Portuguese, a Swede and an Italian, who variously plied every trade from doctor, tailor, hatter, pastrycook, dancing master and gardener to governess and hairdresser – and packed them off away from the war zone.5

Another potential threat were the Old Believers, a sect which had split from the Orthodox Church a century and a half earlier in protest at reforms brought in by the Tsar. They regarded Alexander, not Napoleon, as the Antichrist. But although they were ubiquitous, they were few in number and passive by nature.

Amongst Russians, first reactions to the invasion had been positive, even if some exaggerated the patriotic surge. In an unfinished novel set in 1812, Pushkin depicts Moscow society as francophile and dismissive of the rather ‘simple’ defenders of things Russian, whose patriotism ‘was limited to passionate condemnations of the use of French’, until the French invaded. From that moment, ‘social circles and drawing rooms filled with patriots: some threw the French snuff out of their snuffboxes and began to use the Russian variety; others burned French pamphlets by the dozen; others turned away from the Lafitte and took to sour cabbage soup instead’. Pushkin was certainly being a little ironical. Others were less so. ‘News that the enemy had invaded made people of every age and condition forget their private joys and sorrows,’ noted the nationalist Filip Vigel in Penza. ‘When news of the intrusion of Napoleon’s countless hordes spread through Russia, one can truly say that one feeling inspired every heart, a feeling of devotion to the Tsar and the fatherland,’ wrote Prince N.V. Galitzine, a serving officer. In Moscow, ‘old ladies would cross themselves, spit and curse Napoleon’, while young society girls imagined themselves in the roles of Amazons or nurses.6 But such enthusiasm was by no means shared by the population as a whole.

Over 90 per cent of this consisted of serfs, about half of them owned by the nobility, the rest by the Church or the state. Serfs were chattels. They could be bought and sold, included in a gambling debt, marriage contract or loan. They could be flogged by their masters, and killed in the process. There was no identifiable revolutionary urge among the serfs, mainly because they had no leaders, but there was always the potential for bloody mutiny, and there had been a terrible one, led by Pugachov, in living memory.

The intrusion of the French army could not fail to affect the peasants’ attitude towards their rulers, or at least bring to the surface latent grievances. The authorities had anticipated this, and the police intensified their snooping in taverns and alehouses all over the country. There were confused reports of agitators travelling around the countryside encouraging serfs to rise, and rumours circulated among peasants and house serfs to the effect that Napoleon had told Alexander to emancipate them, otherwise he would. Alexander had stationed half-battalions of three hundred men in every province as a precaution, which was not misplaced. There would be sixty-seven minor peasant revolts in thirty-two different provinces in the course of 1812, more than twice the annual average.7

The serfs were nevertheless Russians, deeply attached to their land and their faith, and it was hoped that they would rally to the defence of these. But first signs were not promising. D.I. Sverbeev, the nineteen-year-old son of a landowner to the south of Moscow, recalled how, on hearing news of the invasion, his father called his serfs together after church on Sunday. The seventy-two-year-old master announced that he and his son were going to go to Moscow to enlist, and called on his serfs to volunteer. There was much shuffling of feet, and finally one old peasant volunteered, while some of the others offered a few pennies. Other squires fared even less well. There were instances of rebellion and sacking of manors as the French armies drew near.8

It was up to Alexander to ensure that patriotic feeling, or rather the determination to stand by the whole political, social, religious and cultural edifice which he embodied, spread through every class of the nation. A huge propaganda exercise was required, and in this Shishkov was to be invaluable. Alexander would hand him a draft proclamation, written in French, and Shishkov would turn it into stirring Russian. The manifesto issued in Polotsk on 6 July announced that Napoleon had come to destroy their ‘great nation’. ‘With guile in his heart and flattery on his lips he is bringing for it eternal flails and shackles,’ it warned. Alexander would chase Napoleon from the land, but as Napoleon disposed of enormous strength, the Tsar would need to gather new forces. The manifesto represented the whole nation as being engaged in a life and death struggle in defence of their wives, children and homes, and called on nobles, clergy and peasants to emulate heroes of the past. Shishkov knew how to combine love of family and home with love of fatherland and Tsar. His proclamations were couched in biblical vein, equating Russia with the chosen people which must one day tower above others, and brimmed with pious confidence in divine providence.9

Alexander also brought the propaganda machine of the Orthodox Church into play. He wrote to bishops urging them to mobilise their clergy into action against the common threat of the alien and godless ‘army of twenty tongues’, as the multinational Grande Armée was sometimes referred to. The Synod issued its own proclamation, calling on everyone to take up arms in defence of faith and fatherland against the godless intruders who had offended the Almighty by overthrowing the throne and the altar in France. It called on priests up and down the country to arm simple souls with the correct sentiments. At Alexander’s request, Augustine, Vicar of Moscow, wrote a special prayer in which the faithful could beg God to defend Russia, inspire devotion to the Tsar and imbue him with all the wisdom and courage required to give him victory, quoting the examples of Moses and Gideon, David and Goliath.10

Issuing ringing manifestos was one thing. Keeping people calm was another. The febrile mood of St Petersburg veered from absurd optimism to darkest despair with astonishing ease. ‘Everyone is expecting a courier to appear at any moment with news of a victory, rumours of which are circulating in the city,’ wrote an inhabitant of the capital to a friend in the county on 21 July. ‘They say that Bagration has beaten the King of Westphalia. They give the number of prisoners taken as 15,000.’ There was talk of resounding victories: Wittgenstein had thrashed Oudinot and Macdonald, Ney and Murat had been beaten outside Vitebsk, and so on.11

But there was also much anger at the retreats, and at the optimistic bulletins being issued by the authorities. ‘In these they write about our successes, about the slow pace of Napoleon’s advance, about his lack of confidence in his forces, but the facts themselves show us something quite different; we have been successful only in retreating, and while the enemy has not conquered, he has simply helped himself to entire provinces,’ complained Varvara Ivanovna Bakunina in a letter to a friend, adding that ‘despair and fear grow by the hour, while they try to deceive us, assuring us … that all this is happening according to some very clever plan’. Hundreds of refugees from Riga had turned up in St Petersburg, sowing panic. ‘Grief, fear and despair has taken hold of everyone,’ she reported on 6 July.

The ratification of peace with Turkey, announced a week later, steadied nerves. But fast on this came news that Alexander had abandoned Drissa, which threw St Petersburg into a panic. Tidings of Wittgenstein’s stand at Yakubovo restored a semblance of calm. On 25 July there was a service of thanksgiving for this in the Tauride Palace, followed three days later by one for Tormasov’s success at Kobryn. But when they heard that Napoleon was in Vitebsk, many people began to pack their bags and some actually left St Petersburg, expecting it to be the next goal of his advance.12

The mood was only a little steadier in Moscow. On 27 June, three days after Napoleon crossed the Niemen but before she had heard of it, Maria Apolonovna Volkova wrote to her friend Varvara Ivanovna Lanskaia that she ‘had always been of the opinion that one should not concern oneself too much with the future’. But her philosophy did not stand up to the test when the fatal news broke. ‘Peace has abandoned our lovely city,’ she wrote on 3 July. A couple of days earlier, a German inhabitant of Moscow was nearly stoned to death by the mob, who thought he was French. A week later, Maria Apolonovna took up the pen once more. ‘Five days ago they were saying that Ostermann had won a great victory. This turned out to be a fabrication,’ she wrote. ‘This morning news reached us of a brilliant victory won by Wittgenstein. This news comes from a reliable source, and Count Rostopchin is confirming it, but nobody dares believe it.’13

What Alexander had to do was to convert these fears and this anger into action. In the first place, he needed more men – and these belonged, physically, to the landed nobility. There had already been much grumbling in March when he had squeezed another extra draft out of them, and he would need all their good will to get them to give him more now. He also needed large quantities of cash, and he must therefore appeal for donations, over and above taxation, which had itself been increased dramatically in the run-up to war. It would be the greatest test his legendary charm was ever put to.

In Smolensk, where he went first, many nobles came and offered themselves and their wealth to the cause. Typical of them was Nikolai Mikhailovich Kaliachitsky, who offered his three sons for ‘either a determined defence or a glorious death’, as well as wagonloads of supplies for the army, which virtually spelt ruin for his small estate.14 Emboldened by the effusion of patriotism and devotion to his person he had witnessed here, Alexander set off for one of the most important meetings of his life – that with the inhabitants of Moscow.

He did not want to make a triumphal entry into the city, as he was not at all sure of the reception he would get in this stronghold of the ‘starodumy’, the defenders of tradition whom he had done his utmost to placate by ditching Speransky and appointing Rostopchin. He asked the Governor to drive out and meet him at the last posting station before Moscow on the afternoon of 23 July. They had a long talk, during which Rostopchin reassured him that he had the city under control and that Alexander had nothing to fear. The Tsar nevertheless resolved to drive into Moscow at midnight, hoping that by then everyone would be in bed. But he was to be disappointed.

The nobility had gathered to meet him in the Kremlin. The great rooms were filled with aristocrats and high officials, while the open spaces inside the precincts were crowded with the populace. Suddenly a rumour spread through the throng that Orsha had fallen to the French, and the people surged around the Kremlin howling about treason. Then someone suggested that the Tsar had not shown up yet because he was dead. ‘A tremor ran through the crowd,’ recalled one of the young noblewomen in the upstairs rooms. ‘They were ready to believe anything and to fear everything.’ Someone standing next to her, hearing the roar of the populace outside, whispered ‘Rebellion!’ The word flew through the room, and bedecked aristocrats began to panic. Happily for all concerned, a courier then appeared announcing the Tsar’s imminent arrival.15

Crowds had also gathered on the Poklonnaia, the hill of Salutation, to greet him, but instead of waiting, they moved further and further out along the road. It was a warm, starry night, and when his carriage was still fifteen versts from the city, Alexander found the road lined with peasants clutching candles and priests holding aloft icons and blessing him. When he reached the city, the crowd unharnessed his horses and hauled his carriage through the streets, with people kneeling as he passed.

The next morning he attended a solemn service in the Kremlin’s Uspensky cathedral to celebrate the ratification of the peace with Turkey. Afterwards Metropolitan Platon blessed him with an icon of St Sergei which had accompanied Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich in his wars against the Poles and Peter the Great against the Swedes. ‘Lead us where you will, lead us, father, we will die or conquer!’ people shouted all around him. But he was nevertheless nervous when, on the following day, he set off to the Sloboda Palace, where the nobility and the merchants had gathered to meet him. Alexander looked ‘pale and thoughtful’, and unlike himself without his usual warm smile. In order to reassure him, Rostopchin had parked a row of police kibitkas outside the palace, and was prepared to bundle any troublemakers into them and send them off to Kazan. But they would not be needed. Alexander harangued the nobles and the merchants about the need to make sacrifices in order to defend the fatherland, and then left them to debate, separately, on the matter.16

The nobles began to discuss the viability of raising one man in twenty-five, when someone suggested one in ten. It later transpired that the proposal had been put forward by a man who owned no land in the province and only wanted to gain influence at court. His suggestion hit the mood and was endorsed in a rush of enthusiasm. The merchants’ meeting was held in a no less exalted atmosphere. ‘They struck themselves on the head, they tore out their hair, they raised their hands to heaven; tears of fury flowed down their faces, which resembled those of ancient heroes. I saw one man grinding his teeth,’ recorded a witness. ‘It was impossible to discern exact words in the general uproar; all one could hear were wails and shouts of indignation. It was a spectacle quite unique.’ The provost of the merchants gave a huge sum, saying: ‘Je tiens ma fortune de Dieu, je la donne à ma patrie.’ As well as offering to give one man in ten to the militia, the nobility came up with a pledge of three million roubles, and the merchants contributed eight million.17

Alexander had achieved something far greater than merely obtaining the men and the cash he needed. According to Prince Piotr Andreievich Viazemsky, who was living in Moscow at the time, the war had been regularly discussed in the English Club and in drawing rooms, but the tone of the discussions had always been a touch academic, as though it did not really concern those present. But everything changed with Alexander’s arrival on the scene. ‘All vacillation, all perplexity vanished; everything seemed to harden, to become tempered and came together in one conviction, in one holy feeling that it was necessary to defend Russia and save her from the invading enemy.’18

His visit to Moscow had a profound effect on Alexander himself, and he left the old capital on the night of 30 July a stronger man. He was filled with a new determination and strength by the effusion of devotion to his person. ‘I have only one regret, and that is not to be able to respond in the way I should wish to the love of this admirable nation,’ he said to one of the Tsarina’s ladies-in-waiting, Countess Edling. ‘How so, Sire? I do not understand.’ she replied. ‘Yes, it needs a leader capable of leading it to victory, and unfortunately I have neither the experience nor the talents required at such a moment.’ Despite himself, he began to think once more of assuming command of the army. But a timely letter from his sister Catherine, which pointed out that he had let down Barclay by his indecision, virtually ordered him not even to think of it.19

The Russian army was no happier than the French at its failure to stand and fight at Vitebsk, and the troops were in a state of dejection as they trudged back towards Smolensk. They reached the city on 1 August and made camp on the north bank of the Dnieper. Barclay issued a proclamation to the effect that they were about to be joined by Bagration’s Second Army, and would then be ready to take on the French, which lifted spirits.

On the following day, Bagration himself rode into Barclay’s camp wearing all his decorations and accompanied by a suite of generals and staff officers. Barclay looked sober and underdressed as he came out to meet him. ‘They greeted each other with all possible marks of courtesy and the appearance of friendship, yet with coldness and distance in their hearts,’ according to Barclay’s chief of staff Yermolov. Bagration’s Second Army was only a day’s march behind him, and he graciously placed himself and it under Barclay’s command.20

‘This news filled everyone with extraordinary joy,’ recalled Nikolai Mitarevsky, a fledgling artillery officer in General Dokhturov’s corps. ‘We thought there would be no more retreating and the war would take on a different character.’ The very look of the Second Army buoyed up the spirits of the men of the First, as Yermolov explained: ‘The First Army, exhausted by the retreat, had begun to mutter and had given rise to disorders, a sure sign of the collapse of discipline. The unit commanders had cooled towards the commander, the lower ranks felt their confidence in him shaken. The Second Army was fired by a completely different spirit! The constant sound of music, the ubiquitous strains of singing coming from them, revived the spirits of the soldiers.’21

The anti-Germans and russophiles expected the brave spirit of Bagration to dominate, and the consciousness that they were now standing in defence of old Russian lands was expected to have an effect as well. ‘The spirit of the nation is awakening after a two-hundred-year slumber, feeling the threat of war,’ wrote Fyodor Glinka, a passionately russophile officer, alluding to the Polish wars of 1612. Songs and odes were composed in honour of what was to be a heroic and successful stand at Smolensk.22 Others talked of taking the offensive and chasing the French out of Russia.

The Russians were now in a stronger position than they had been at any time since the start of the war. They had, it is true, given up a vast part of their territory, lost up to 20,000 men, a couple of dozen guns and huge stores of supplies. But they now had some 120,000 men grouped in the centre, with two forces, of 30,000 in the north and 45,000 in the south, threatening Napoleon’s flanks. From their own intelligence and the questioning of prisoners, they knew about the difficult conditions in the French army, whose main attacking force they now estimated, somewhat conservatively, at about 150,000.

Yet, as Clausewitz pointed out, their new strength was a strategic rather than a tactical one, and the French would still be bound to win a pitched battle. But the ability of the French to operate effectively was reducing with every day. There was, as a result, no point whatsoever in the Russians taking the offensive at this stage.23 Yet that is exactly what they were determined to do. The whole army, from the top down to the last ranker, was fed up with the continuous retreat. They had been told of brilliant victories won by Tormasov, Wittgenstein, Platov and others, and they could not conceive why they were themselves giving up territory without a battle. Now that Bagration had joined forces with Barclay, there seemed to be no further excuse for retreating, and there was a universal desire to stand and fight.

Barclay, who realised the pointlessness of giving battle at this stage, was being put under great pressure to do just that, from above by Alexander himself, and from below by everyone down to the ranks, and he was in no position to oppose. On 3 August he wrote to Alexander that he was going to attack the exposed corps of Ney and Murat. But everything points to the fact that he was still hoping to be able to avoid giving battle. On 6 August he held a council of war at which he argued his case, but he was powerfully outnumbered by the hawks, and reluctantly agreed to the attack, urging everyone to proceed with extreme caution.

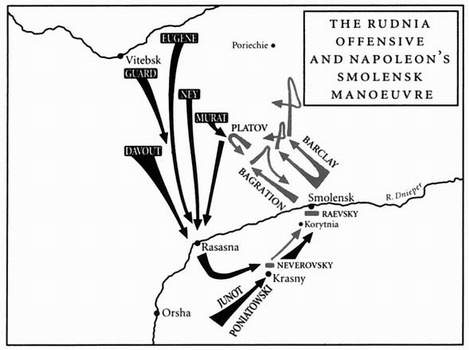

They set out on the morning of the following day, 7 August, in three columns, which were to attack and overwhelm Murat’s cavalry and Ney’s corps, encamped around Rudnia, ahead of the rest of the French forces. The enterprise could have been successful had it been carried out with speed and determination. It would have made no difference to the strategic situation, yet it would have raised the morale of the Russian troops and made it more difficult to retreat again afterwards (which they would have to do anyway), so in this case success would have had mixed benefits. In the event, success was not going to be an issue.

On the night of 7 August, at the end of the first day of the offensive, Barclay received intelligence, inaccurate as it turned out, that a large French force had occupied Poriechie, to the north of his line of attack. This could only be either an attempt at outflanking him or an exposed enemy unit which could be easily cut off. He therefore ordered his three columns to wheel round to face in a northerly direction. Bagration did not understand the thinking behind this order, and obeyed only with extreme reluctance. But the order never reached the cavalry, under Platov and Pahlen, and while Barclay and Bagration marched northwards on the following day, the cavalry continued to move westwards. At Inkovo it stumbled on General Sebastiani’s cavalry division, which it surprised and routed, taking a couple of hundred prisoners, but it was subsequently beaten back by a French counterattack.

When Napoleon learned of the Russian attack the next day, he deduced that Barclay had decided to fight in defence of Smolensk. But he was by now wary of the Russians. Determined to make sure that they would not escape this time, he put into action a plan to encircle them and strike them in the back. He instructed Prince Eugène to move south and join Ney in keeping an eye on the area where he assumed the Russian army to be, and ordered all other units in the Vitebsk area to make for Rassasna on the Dnieper. They were to cross the river and join Junot’s and Poniatowski’s corps, then sweep into a presumably unoccupied Smolensk, recross the river and appear behind Barclay’s back.

But Barclay’s forces were by now in a state of such confusion that Napoleon need not have bothered. After assuring himself that there were no French at Poriechie, Barclay had marched back to his starting position and ordered Bagration to do the same, intending to implement the original plan of a frontal attack on Rudnia. But when Bagration, who was sullenly trudging back towards his starting positions, got what was now his third order to about turn and march in a different direction, he was beside himself with irritation. ‘For the love of God,’ he wrote to Arakcheev, ‘give me a posting anywhere away from here – I’ll even accept command of a regiment, in Moldavia or the Caucasus if necessary – I just cannot stand it here any longer; headquarters is so full of Germans a Russian cannot survive there.’24

He was so angry that he resolved to ignore Barclay’s order. He was moving in the direction of Smolensk, and he decided to keep going. So while two of the three Russian columns were now wheeling back to march on the French, the third was resolutely moving away in the opposite direction. This act of wilful insubordination was to save the Russian army.

All the changes of order had added to the usual degree of confusion surrounding the movements of an army, with the result that the area in front of the French forces was covered in Russian units marching and countermarching in different directions, some of them lost, most of them confused, and all of them increasingly fed up. ‘As this was the first time we had advanced after so many retreats, the joy felt by the whole corps, which was longing to be able to attack the enemy at last, would be hard to convey,’ wrote Lieutenant Simansky of the Izmailovsky Life Guards.25 The change of plan, which they assumed to herald a new retreat, was therefore greeted with fury.

Junior officers like Simansky wondered whether their commanders knew what they were doing. ‘Our lack of experience in the art of war reveals itself at every step,’ Captain Pavel Sergeevich Pushchin of the Semeonovsky Life Guards noted in his diary on 13 August. The feeling that the commander-in-chief was out of his depth was gaining ground. Staff officers were railing against ‘Germans’, and the word ‘treason’ was being muttered more and more frequently. The iron discipline gripping the Russian soldier was beginning to relax, and instances of desertion and looting multiplied.26 Had Napoleon delivered an energetic frontal attack at that moment, both Russian armies would have been annihilated.

But Napoleon was busy implementing his own plan. At dawn on 14 August the divisions of Davout’s, Murat’s, then Ney’s and Prince Eugène’s corps began to cross the Dnieper at Rassasna on three bridges constructed during the night. The troops then took the great Minsk – Smolensk highway, a wide straight road running between rows of silver birches, laid out by Catherine the Great for the rapid movement of mail and troops. They were joined along this road by Junot’s Westphalians and Poniatowski’s Poles, coming up from Mogilev. In the early afternoon they stumbled on General Neverovsky’s 27th Division, which Bagration had left covering the southern approaches to Smolensk at a place called Krasny.*

Neverovsky had no more than about 7500 men, many of them raw recruits, with which to face Murat’s entire cavalry corps. But he did not lose his head. He sent his cavalry and his guns back to cover his retreat, and formed his men into an extended square formation. Luckily for him, Murat did not deign to stop and wait for his artillery to come up, but threw his cavalry at the Russians, meaning to sweep them out of the way. Where any other army would have laid down its arms or scattered, Neverovsky’s peasant soldiers retreated in a solid mass. ‘The very lack of experience of those Russian peasants making up this unit gives it a force of inertia which amounts to resistance,’ Baron Fain mused. ‘The dash of the cavalrymen was cushioned by this crowd which clung together, pressing and filling every gap. The most brilliant valour was exhausted by striking this compact mass which they could only hack at without breaking up.’27

Neverovsky retreated nearly twenty kilometres under constant pressure from Murat’s cavalry, which delivered some thirty charges. He lost about two thousand men and seven guns, but he reached Korytnia, where he was reinforced on the following morning by troops sent out of Smolensk, and escorted into the city. He also lost one of his regimental bands, which some French grenadiers found cowering in the ruins of a burnt-out church, brandishing their instruments as a mark of their peaceful intentions and begging for mercy in the broken French of one of their number, a native of Tuscany.28

That evening, 15 August, Napoleon reached Korytnia, and was greeted by a hundred-gun salute – it was his birthday. But he had nothing to celebrate. His manoeuvre had failed. He had hoped to find Smolensk undefended, which would have permitted him to occupy the city and use the bridges across the Dnieper to penetrate into Barclay’s rear. As it was, the city was garrisoned – thanks to the insubordination of Bagration.

Napoleon vented his irritation on Poniatowski, whose 5th Corps had just rejoined the main force of the Grande Armée. When the Prince came to Napoleon’s bivouac to pay his respects, the Emperor unleashed a string of gross insults at him, shouting for all to hear, accusing him and his Poles of cowardice and laziness, and saying that the only thing they were good at was playing with Warsaw whores. At the same time, he was furious when he heard that the Poles were down to 15,000 men – some units had lost half of their effectives through forced marches, sickness and fighting. He taunted Poniatowski, and said he and his Poles would have a chance to show their mettle at Smolensk on the following day.29

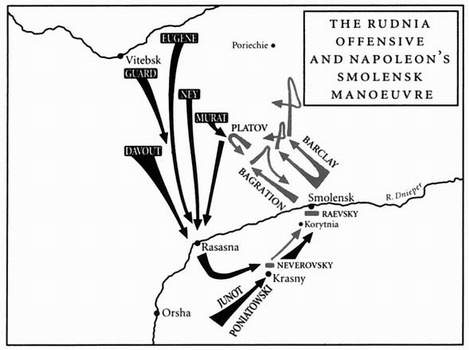

Smolensk was a city of 12,600 inhabitants, and had no particular economic or strategic importance. It did have a certain spiritual significance, as one of its churches housed a renowned miraculous icon of the Virgin, and the city had been the scene of several desperate struggles for dominion over the area between the Poles and the Russians, who had finally wrenched it back 150 years before. It was surrounded by massive brick walls twenty-five feet high and fifteen feet thick, with a deep dry ditch in front, and strengthened by thirty massive bastion towers.30 There was no advantage for Napoleon in taking Smolensk, as his real aim was to defeat the Russian army, and since the chance of crossing the Dnieper and penetrating into their rear had been denied him here, he should have immediately gone in search of a crossing point further east. Had he done so, he would have forced the Russians to fight and would certainly have won Smolensk without a blow, probably with its magazines intact. He did send Junot off up the Dnieper in search of a crossing. But he had willed himself to believe that the Russians would come out and face him in defence of their holy city, so he decided to attack it. In doing so he committed, according to Clausewitz, his greatest error of the whole campaign.31

Murat and Ney reached Smolensk early on the morning of 16 August and launched a first attack. This was successfully beaten off by General Nikolai Raevsky with his 7th Corps, and at midday the defenders were reinforced with more of Bagration’s troops. In the afternoon the French could see large columns of Russian troops coming into view on the opposite bank of the Dnieper, their bayonets glinting. It was Barclay, who had been obliged to abandon his attack on Rudnia by Bagration’s refusal to cooperate with him. He had heard of Napoleon’s crossing of the river on the night of 14 August and had hurried back to Smolensk. On seeing this, Napoleon, according to some, rubbed his hands, saying: ‘At last! Now I’ve got them!’32

Barclay was under tremendous pressure to defend the city. He realised that it was a hopeless position, which could have been held at most for a week or two, at immense cost and to no advantage. But his authority was by now so shaky that even though his instinct told him to fall back, he had to make a show of defending Smolensk. As he was afraid that Napoleon might try to cross the Dnieper further east, and no doubt also to be rid of him, he sent Bagration down the Moscow road towards Dorogobuzh, with orders to prevent any French crossing the river and to keep the line of retreat open. On the evening of 16 August he relieved Raevsky with 30,000 men under Dokhturov, who were to hold the city. He stationed the rest of his forces and set up his batteries on the north bank.33

On the morning of 17 August the French attacked the outlying suburbs outside the city walls. In hand-to-hand fighting they managed to push back Dokhturov’s men, but were counterattacked by a large force and fell back. Napoleon hoped that this Russian sortie meant the whole Russian army was going to come out of the city to face him, but he was disappointed.

The action had taken up most of the morning, and was accompanied by heavy shelling of the Russian positions by French artillery. At midday there was a lull in the fighting. Lieutenant Hubert Lyautey of the artillery of the Guard had been in action all morning, and he took the opportunity to lead his horses down to the river for watering. The Russian batteries on the opposite shore had come to do the same. ‘The Russians drank on one side, we on the other, we communicated with each other with words and gestures, we exchanged drinks, tobacco, in which we were richer and more generous,’ Lyautey wrote in a letter home. ‘Soon afterwards, these good friends were exchanging cannon shots.’34

At 2 p.m., seeing that the Russians were not going to come out and give battle, Napoleon gave the order for a general assault on the city. Over two hundred guns opened up, and three corps of the Grande Armée went into action. It was an unforgettable sight for those present. The city of Smolensk lies on a slope descending to the river Dnieper, on the side of a great amphitheatre, the other side of which is made up by the slope rising from the other side of the river. This was occupied by Barclay’s army, which could see the whole city across the river and the French attacking it from three sides. As the French attackers went into action, their comrades watched from the top of the slope, cheering them on. The weather was fine, the troops were in full dress uniform, and they went into the attack with their bands playing. It was a magnificent spectacle.

In the centre were Davout’s three divisions, under Generals Morand, Gudin and Friant; on the left Ney with two divisions, one of them of Württembergers; on the right Poniatowski with two divisions, and on his right General Bruyère’s cavalry division; a total of some 50,000 men. The French columns lumbered forward. Bruyère’s horsemen charged a body of Russian dragoons under General Skallon and swept them off the field, killing their commander. The infantry penetrated the suburbs and forced the defenders to retreat. The Russians attempted a counterattack, but this was beaten back in fierce hand-to-hand fighting. ‘On both days at Smolensk, I attacked with the bayonet,’ recalled the Russian General Neverovsky. ‘God preserved me, and I only had three bulletholes in my coat.’35 Eventually the French reached the city walls, which they then tried, vainly, to escalade. They had no ladders, so all they could do was attempt to climb them.

Auguste Thirion of the 2nd Cuirassiers went to get a better view from the emplacement of one of the French batteries, which was being shelled by Russian guns from the heights on the other side of the river. ‘I cannot conceive how a single man or a single horse could escape that mass of cannonballs coming from two sides and crossing in the midst of those batteries,’ he wrote, but it did not prevent him enjoying the spectacle. ‘We also saw at our feet infantry laboriously descending into the ditches, or rather the ravines which made up the moat of the fortress. It was a Polish division which was trying to storm those rocks with a courage, a desperation worthy of greater success; these brave men tried to scale them by climbing on each other’s shoulders. But the nature of the terrain would not permit of success, and it was a unique and curious spectacle to see that ant-like mass of men crawling over the rocks in such a picturesque manner while above their heads the cannon which were the object of their efforts thundered against their brothers in arms. Opposite them, the French batteries fired projectiles which occasionally fell short, showering the rocks with a mass of fragments of the walls.’36

Charles Faré, a lieutenant in the 1st Grenadiers of the Old Guard, told his mother in a letter home that he had never seen French troops fight with greater dash. Ney himself said that the attack by one battalion of the 16th Regiment of the Line was the bravest feat of arms he had ever seen. But not everyone was cheering. General Eblé and his colleague the cartographer of the Grande Armée, General Armand Guilleminot, could see no point to the grand frontal assault on the city walls. They knew that the twelve-pounder field guns Napoleon had brought up were of no use, as their cannonballs were simply absorbed by the soft brick fortifications, and that they could not make a breach in the massive walls. ‘He always wants to take the bull by the horns!’ exclaimed Eblé, shaking his head. ‘Why doesn’t he send the Poles off to cross the Dnieper two leagues upstream of the city?’37

Others who were not enjoying the spectacle were the citizens of Smolensk. In the morning the inhabitants of the suburbs had taken weapons from the bodies of dead soldiers and made up gaps in the ranks of the defenders; priests holding crucifixes aloft placed themselves at the head of the militiamen and died with them. When the troops were beaten back, the civilians tried to follow. ‘The inhabitants fled in horror, dragging their valuables; here I saw a good son, bearing on his shoulders an infirm father, there a mother making her way along a safe path towards our positions clutching her little ones in her arms, having sacrificed everything else to the enemy and to the fire,’ recalled one artillery officer.38

Their fate was not much more to be envied when they did manage to get into the old city within the walls, according to a fifteen-year-old officer in the Simbirsk Infantry Regiment. ‘What an awful confusion I witnessed within the walls: the inhabitants, believing that the enemy would be repulsed, had remained in the city, but that day’s strong and violent attack had convinced them that it would not be in our hands by the morrow. Crying out in despair, they rushed to the sanctuary of the Mother of God, where they prayed on their knees, then they hurried home, gathered up their weeping families and left their houses, crossing the bridge in the utmost confusion. How many tears! How much wailing and misery, and, in the end, how many victims and blood!’39

The grandiose spectacle of the afternoon turned into a scene from hell as the evening drew in. The mortar shells that the French had been lobbing into the city had set many of the predominantly wooden houses on fire, and this spread rapidly. Baron Uxküll of the Russian Chevaliergardes speaks for many who watched impotently as one of their old cities and its inhabitants were engulfed in the flames. ‘I was standing on the mountain; the carnage was taking place at my very feet. Shadows heightened the brilliant sheen from the fire and the shooting,’ he wrote. ‘The bombs, which displayed their luminous traces, destroyed everything in their path. The cries of the wounded, the Hurrahs! of the men still fighting, the dull confused sound of the rocks that were falling and breaking up – it all made my hair stand on end. I shall never forget this night!’40

The French onlookers were equally gripped by the ‘sublime horror’ of the spectacle; thoughts turned to the fall of Troy. ‘Dante himself would have found here inspiration for the hell he set out to depict,’ according to Captain Fantin des Odoards. As the French still tried to storm the walls, much of the city was on fire, and the defenders showed up as black silhouettes against the flames behind them, looking for all the world ‘like devils in hell’, as Colonel Boulart of the artillery put it. Similar thoughts were going through the head of Caulaincourt as he stood in front of Napoleon’s tent, watching. Suddenly he felt a slap on his shoulder. It was the Emperor, who had come out to watch, and who compared the sight to an eruption of Vesuvius. ‘Don’t you think, Monsieur le Grand Écuyer, that this is a fine spectacle?’ he added. ‘Horrible, Sire,’ was Caulaincourt’s only answer.41

Grand spectacle or not, Napoleon had nothing to be pleased about. As the fighting died down that night it became apparent that the French had gained nothing and lost at least seven thousand men in dead and wounded. Barclay too had little to rejoice over. Aside from the satisfaction of denying the French an easy victory, he had achieved nothing, beyond the loss of over 11,000 men and two generals.

Barclay realised that he could not stay where he was much longer, as it was only a matter of time before Napoleon crossed the Dnieper upstream and cut him off. He had made a symbolic gesture in defending Smolensk for two days, and it was now time to think of saving the army. He therefore ordered Dokhturov to evacuate the city after setting fire to all remaining stores and anything else that could be of use to the enemy, and to destroy the bridges after him. The holy icon of the Virgin of Smolensk had already been removed from its shrine, placed on a gun carriage and escorted over the bridge to the northern bank of the river.

Barclay’s orders for the city to be abandoned provoked a general outcry. ‘I cannot express the indignation that prevailed,’ wrote General Sir Robert Wilson, who had just arrived to take up his post as British ‘commissioner’ at Russian headquarters. A succession of senior officers came to beg Barclay to reconsider his decision, or, if he were determined to retreat, to allow them to fight on to the last drop of blood. Bagration wrote him a note demanding that Smolensk be defended regardless of cost. Bennigsen, in stark contradiction to his earlier assertion that there was no point in a battle at this point in the retreat, came out in favour of a last-ditch stand. He stormed into headquarters, accompanied by Grand Duke Constantine and a bevy of generals, demanding that Barclay change his plans. The Grand Duke virtually commanded him to rescind his ‘cowardly’ order and launch a general attack on the French. ‘You German, you sausage-maker, you traitor, you scoundrel; you are selling Russia,’ he shouted at Barclay for all to hear. ‘I refuse to remain under your orders,’ he added, saying he would move the Guards corps under Bagration’s command. He continued to heap invective on Barclay, who eyed him in silence. ‘Let everyone do their duty, and let me do mine,’ he finally interjected, cutting short the argument. That evening Constantine received an order from Barclay to take an important letter to the Tsar and hand over command of the Guards to General Lavrov.42

Two hours before dawn the last of Dokhturov’s men trudged back across the bridges and set fire to them. A short while earlier, a voltigeur company of the 2nd Polish Infantry managed to make a breach in the walls and entered the blazing city. In the morning, once one of the gates had been opened and its approaches cleared of the dead and dying bodies heaped around it, the French made their entry into the city.

It was a veritable charnelhouse, its streets strewn with corpses, mostly blackened by fire. In the ruins of houses that had been engulfed by fire lay the remains of inhabitants or wounded soldiers who had taken refuge inside. ‘One had to walk over debris, dead bodies and skeletons which had been burned and charred by fire,’ recalled one French officer. ‘Everywhere unfortunate inhabitants, on their knees, weeping over the ruins of their homes, cats and dogs wandering about and howling in the most heart-rending way, everywhere only death and destruction!’ The Russian wounded had been laid out in makeshift hospitals, which had then been swept by fire as their comrades evacuated the city. ‘These unfortunates, abandoned in this way to a hideous death, lay in heaps, calcinated, shrunken, conserving only just a human form, amidst the smoking ruins and burning beams,’ in the words of Lieutenant Julien Combe of the 8th Chasseurs à Cheval. He was not the only one to notice that the bodies of the burnt soldiers had shrunk; some thought they were those of children. ‘Soldiers who had wanted to flee had fallen in the streets, asphyxiated by the fire, and had been burned there,’ observed Dr Raymond Faure. ‘Many no longer resembled human beings; they were formless masses of grilled and carbonised matter, which the metal of a musket, a sabre, or some shreds of accoutrement lying beside them made recognisable as corpses.’43

One German soldier could hardly believe what he saw as he tramped up streets carpeted with human remains. ‘Like thousands of others, I was marching along when, between two burnt-out houses, I saw a small orchard whose fruit had been carbonised, underneath the trees of which were five or six men who had been literally grilled,’ he wrote. ‘They must have been wounded men who had been laid out in the shade before the fire started. The flames had not touched them, but the heat had contracted their nerves and pulled up their legs. Their white teeth jutted from between their shrivelled lips and two large bloody holes marked the place where their eyes had been.’44

All this had a profound effect on the army. ‘It marched through these smouldering and bloodied ruins in good order with martial music and its habitual pomp, triumphant on these deserted ruins, and having nobody but itself as a witness to its glory!’ in the words of Ségur. ‘Spectacle without spectators, victory practically without fruit, bloody glory, of which the smoke which surrounded us, and which seemed to be our only conquest, was the only too faithful emblem!’45

The city was not in fact entirely deserted. A considerable number of the inhabitants had not managed to get away, and they cowered among the ruins or thronged the churches, which, being of brick and stone, were refuges from the fire. There were also thousands of wounded Russian soldiers, and as the French prepared to march into Smolensk a delegation from the city authorities came out to ask Napoleon to help take care of them. He detailed sixty physicians and medical staff to go into the city and organise hospitals.46

This was easier said than done. Several large buildings such as monasteries and warehouses were designated for the purpose and the wounded were brought in, but there were no beds or mattresses to lay them on, and it was days before straw could be found to place on the floor under them. The lightly wounded were laid side by side with the sick, and infection spread quickly as they lay sweating in what even Napoleon termed ‘dreadfully hot’ weather. The sheer numbers of the wounded meant that many were not dressed for a day or two, by which time supplies had run out. Surgeons were sewing up wounds with tow in lieu of thread and dressing them with strips torn from their own uniforms and paper taken from the city archives. ‘Without medicines, without broth, without bread, without linen, without lint and even without straw, they had no other consolation as they lay dying other than the sympathy of their comrades,’ in the words of General Berthézène. Napoleon sent Duroc around the hospitals to give the wounded money, but while in Austria or Italy this would have meant they would have been able to procure food and other necessities for themselves, here they would be able to buy nothing, while the possession of the coins made them vulnerable to robbery and murder.47

‘That is the hideous side of war, the one to which I shall never grow accustomed,’ noted Captain Fantin des Odoards of the Grenadiers of the Guard as he walked through the city on the following day. ‘To see so much misery and not to be able to provide assistance is torture.’ Seasoned soldiers could not afford to dwell on such thoughts if they were to survive. General Dedem de Gelder, whose division bivouacked on the main square that night, did his best. ‘I spent the night on a very luxurious settee which the men had found in one of the neighbouring town houses,’ he recalled, and he dined on jam, stewed fruit, two fresh pineapples and some peaches. ‘I would have preferred a good soup, but in war, one eats what one finds.’48

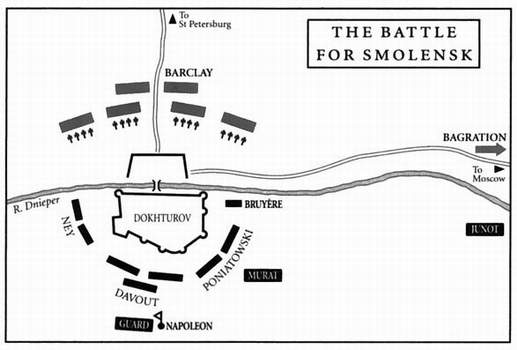

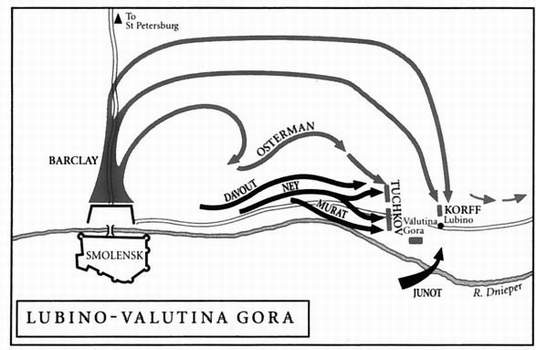

Barclay had remained on the north bank of the Dnieper throughout the day of 18 August, holding the suburb on that side of the river and preventing the French attempts at rebuilding the burnt bridges. But that night he withdrew. As the road to Moscow ran for several miles along the north bank within range of French guns, he set a course that started in a northerly direction, gradually swinging round to rejoin the Moscow road at Lubino. So as to avoid encumbrance along the small country roads they would have to use, he divided his force in two. But this only complicated matters, as during the first stage of the withdrawal, on the night of 18 August, several units lost their way. Progress was slower than expected, with guns and supply wagons getting stuck at the crossing of the many streams dissecting the roads. The inclines were so steep that in several places guns and heavy wagons rolled down, dragging their teams of horses and men to a nasty death at the bottom of a ravine, and in turn obstructing progress further.

In the meantime, Ney had repaired the bridge at Smolensk, crossed the river and started to advance down the Moscow road, while Junot had begun to cross further upstream, at Prudichevo. Fearing that they might reach it before his retreating men did, Barclay had sent General Pavel Alekseievich Tuchkov with a small force to Lubino to cover the point at which the wheeling Russian columns were to rejoin the Moscow road.

Ney, who began to move along the Moscow road in the morning, was checked by what he thought was a counterattack developing on his left flank. In fact it was Ostermann-Tolstoy’s division, which had got lost in the night, and after marching in a circle for ten hours reappeared outside Smolensk. Ney deployed against it, which gave Tuchkov some time, but soon the French were pushing the Russians back along the Moscow road.

On hearing of the fighting, Napoleon rode out to the scene. Assuming that this was no more than a rearguard action, he ordered Davout to back up Ney with one of his divisions. Together they pushed Tuchkov back, but he too was reinforced by other units and the timely arrival of Barclay himself, who rallied the troops and steadied the situation. Wilson was impressed by Barclay, who ‘seeing the extent of the danger to his column, galloped forward, sword in hand, at the head of his staff, orderlies, and rallying fugitives, and crying out, “Victory or death! we must preserve this post or perish!” by his energy and example reanimating all, recovered possession of the height, and thus under God’s favour the army was preserved!’49

The Russians took up strong positions at Valutina Gora. Junot with his Westphalians was actually behind their left wing, and could have taken them in the back, which indeed Napoleon ordered him to do. But the usually fearless Junot, who had been acting strangely and complaining of heat stroke, made a number of incoherent replies and would not move, even when Murat galloped up in person to tell him to attack.

‘If we had attacked, the Russians would have been routed, so all of us, soldiers and officers, were eagerly awaiting the order to attack,’ wrote Lieutenant Colonel von Conrady, a Hessian in Junot’s corps. ‘Our ardour to go into battle was expressed vociferously, with whole battalions shouting that they wanted to advance, but Junot would not listen, and threatened those who were shouting with the firing squad … Grinding our teeth, we were reduced to the role of spectators, while honour and duty beckoned. Never was an opportunity to distinguish oneself more shamefully lost! Several officers and soldiers in my battalion wept with despair and shame.’50

There were by now some 20 to 30,000 Russians facing, and outflanked by, as many as 50,000 French. According to Barclay’s aide-de-camp Woldemar von Löwenstern, Tuchkov rode up and asked for permission to fall back, to which Barclay allegedly replied: ‘Return to your post and get yourself killed if you must, for if you fall back I shall have you shot!’ Aware that the fate of the Russian army was in his hands, he held on, but it was touch and go. At one point Yermolov, who was watching, seized his aide-de-camp by the elbow. ‘Austerlitz!’ he whispered in horror.51

If the French had been able to defeat Tuchkov, they could have sliced through the middle of the Russian forces on the march, and these would have stood no chance. ‘Never had our army been in greater danger,’ Löwenstern later wrote. ‘The fate of the campaign and of the army should have been sealed on that day.’52

It was unlike Napoleon not to sense the reason behind the Russian stand, but at about five o’clock in the afternoon he left Ney to get on with it and rode back to Smolensk. ‘He seemed to be very annoyed, and broke into a gallop when he came up with us, whose acclamations appeared to importune him,’ noted an officer of the Legion of the Vistula who watched him ride by.53

Tuchkov stood his ground, and his men fought like lions. Ney’s divisions, supported by Davout’s Gudin division, also fought with dash and determination, and the battle developed into a massacre which only ceased when darkness fell. The field was strewn with seven to nine thousand French and nine thousand Russian dead and wounded, but the living lay down to sleep among them, too exhausted to build a camp.54

The following morning, Napoleon rode out to the scene. ‘The sight of the battlefield was one of the bloodiest that the veterans could remember,’ according to one of the Polish Chevau-Légers who escorted him.55 He took the salute of the troops drawn up on this field of death and proceeded to enact one of the rituals that made him such a brilliant leader of men. He had decreed that he would award the coveted eagle that topped the standards of regiments which had proved their valour to the 127th of the Line, made up largely of Italians, which had distinguished itself on the previous day. ‘This ceremony, imposing in itself, took on a truly epic character in this place,’ in the words of one witness. The whole regiment was drawn up as if on parade, the men’s faces still smeared with blood and blackened by smoke. Napoleon took the eagle from the hands of Berthier and, holding it aloft, told the men that it was to be their rallying point, and that they must swear never to abandon it. When they had sworn the oath, he handed the eagle to the Colonel, who passed it to the Ensign, who in turn took it to the centre of the élite company, while the drummers delivered a deafening roll.

Napoleon then dismounted and walked over to the front rank. In a loud voice, he asked the men to give him the names of those who had particularly distinguished themselves in the fighting. He then promoted those named to the rank of lieutenant, and bestowed the Légion d’Honneur to others, giving the accolade with his sword and giving them the ritual embrace. ‘Like a good father surrounded by his children, he personally bestowed the recompense on those who had been deemed worthy, while their comrades acclaimed them,’ in the words of one officer. ‘Watching this scene,’ wrote another, ‘I understood and experienced that irresistible fascination which Napoleon exerted when he wanted to, and wherever he was.’56

By this extraordinary ceremony, Napoleon managed to turn the bloody battlefield into a field of triumph, sending those who had died to immortality and caressing those who had survived with kind words and glorious rewards. But many asked why he had not been there himself to direct the battle. And his entourage wondered what, if anything, had been achieved by the past four days of bloodletting.57

* The town is referred to by diarists and historians by a variety of names, most commonly ‘Krasnoie’. I give the spelling used by the contemporary local historian Voronovsky.