‘Yet another victory!’ Kutuzov wrote to his wife with touching swank the day after he let Napoleon slip through to Orsha. ‘On your birthday we fought from morning till evening. Bonaparte himself was there, and yet the enemy was smashed to pieces.’ His report to Alexander was more measured, but it did state that he had wiped out Davout and cut off Napoleon at Krasny, and it was backed up by his despatch to St Petersburg of the defeated Marshal’s baton.1 Alexander had the splendid velvet-covered and eagle-studded baton paraded in public as a trophy, but neither he nor anyone else was particularly impressed – a real victory would have been followed by the arrival of at least one captive Marshal of France, not just a few of his baubles.*

Vassili Marchenko, a civil servant who arrived in St Petersburg from Siberia in the first week of November, had found the city eerily quiet and gloomy. Many people had fled and the streets were empty. ‘Whoever was able to, kept a couple of horses at the ready, others had procured themselves covered boats, which waited, cluttering the canals,’ he wrote. ‘This sad state of affairs, uncertainty about the future, and the autumnal weather itself tore at the heart of good Alexander.’3

This was all the more unwarranted as good news had been pouring in for the past four weeks. On 26 October there had been a solemn ceremony of thanksgiving for the victory at Polotsk. The following day the city resounded to the sound of gun salutes and church bells announcing the victory of Vinkovo and the reoccupation of Moscow. On the twenty-eighth Alexander and the Empress Elizabeth, accompanied by the Dowager Empress and the Grand Dukes Constantine and Nicholas, had driven in state to the cathedral of Our Lady of Kazan for a solemn celebration, and he had been cheered wildly by the crowds. ‘Courage is returning at the gallop, people have stopped sending away their effects, and I believe that some are even unpacking them,’ Joseph de Maistre had noted.4

But there was still much uncertainty. Kutuzov’s rivals and their supporters implied that he had bungled the operations and that in his place they could easily have defeated and captured Napoleon. As the various commanders in the field had their partisans at court, St Petersburg was the scene of endless debates and recrimination. ‘To the foreign observer,’ recorded de Maistre, ‘it appears as either a farcical tragedy or an embarrassing comedy.’5 Alexander himself was by now mistrustful of anything he heard from Kutuzov, and he was receiving contradictory reports.

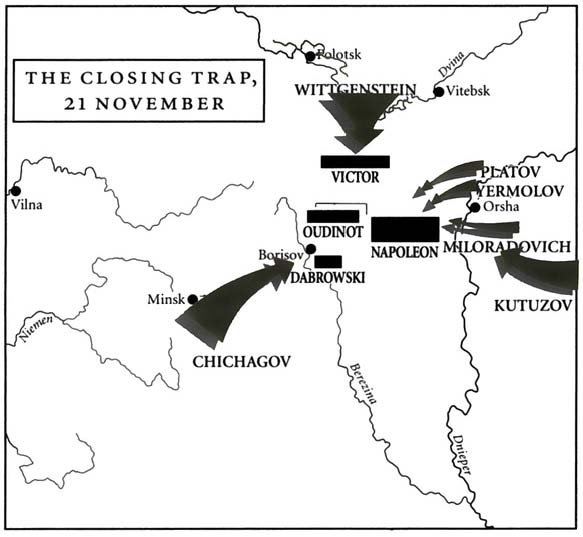

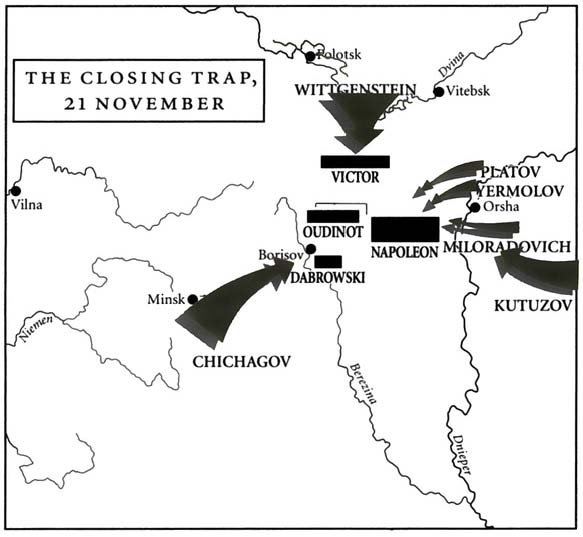

As he surveyed the map and digested the information coming in from his various armies it seemed clear to him that Vinkovo had not been followed up properly, that Maloyaroslavets had been a missed opportunity, and that a number of chances of cutting off and destroying Davout, Ney, Prince Eugène, Poniatowski and, finally, Napoleon himself had been thrown away. ‘It is with extreme sadness that I realise that the hope of wiping away the dishonour of the loss of Moscow by cutting the enemy’s line of retreat has vanished completely,’ he wrote to Kutuzov, barely concealing his anger, and complaining of the Field Marshal’s ‘inexplicable inactivity’. But he could also see that Napoleon was now stumbling straight into a trap, with Chichagov and Wittgenstein poised to cut off his retreat and Kutuzov coming up to destroy him from behind.6

Kutuzov had sent news of Vinkovo to the Tsar through Colonel Michaud, who also delivered the Field Marshal’s invitation to Alexander to come and take command of the army himself. The Tsar had declined, but after four more weeks of apparent failures on Kutuzov’s part, he was growing increasingly anxious that Napoleon might actually manage to get away if he did not take a serious hand in the matter. He bestowed the title of Prince of Smolensk on the Field Marshal for the alleged victories of Viazma and Krasny, but also summoned Barclay to St Petersburg.

Alexander briefly thought of going to take command of Wittgenstein’s army, bringing about a juncture with Chichagov’s and putting himself in a position to deal the final blow. On paper it looked as though he could not fail to destroy the Grande Armée and capture Napoleon, a tempting prospect for the frustrated warrior-Tsar lurking in Alexander.7 But on balance it is probably a good thing as far as his reputation was concerned that he did not, for the situation as seen on paper and that on the ground were very different.

The long march that had all but destroyed the Grande Armée had also taken its toll of the pursuing Russians. They did enjoy various advantages over the French, as they were better clothed, received fairly regular distributions of food and forage, and had the initiative, so they could stop and rest when they needed to. But although they were better equipped to endure it, they were not immune to the weather. They were deft at building shelters, as Lieutenant Radozhitsky recorded: ‘It was hard and sad to watch as, having stopped near some small village, each regiment would send out a detail to fetch firewood and straw. Fences would shatter, roofs fall in and whole houses disappear in a flash. Then, like ants, the soldiers would carry their heavy loads to the camp and proceed to build a new village.’ But when there was no village nearby or they did not have the time, half of the men would spread their greatcoats on the snow and the other half use theirs as overblankets as they lay down, pressed together for warmth.8

After the first weeks of the pursuit, distributions of food became more erratic. The men could only expect hard-tack or the occasional thin gruel which they brewed up themselves. They had to rely more and more on sending out foraging parties. ‘It is wrong to blame only the French for burning and looting everything along the road,’ wrote Nikolai Mitarevsky, who had trouble feeding his artillery horses. ‘We did the same … When we went out foraging, those soldiers who in time of peace passed for scoundrels and cheats became extremely useful. Nothing escaped their eagle eye.’ By the time they had crossed the Dnieper they felt little compunction about taking everything from the locals, whom they did not regard as Russians and suspected of having sided with the French.9

If the French were moving along a devastated road, the Russian units were mostly marching cross-country, which made progress difficult, particularly for the artillery. Bennigsen suggested to Kutuzov that they leave behind four hundred of their six hundred guns, which would have speeded up the advance, but Kutuzov dismissed this along with all the General’s other advice.10

‘Men and horses are dying of hunger and exhaustion,’ noted Lieutenant Uxküll on 5 November. ‘Only the cossacks, always lively and cheerful, manage to keep their spirits up. The rest of us have a very hard time dragging on after the fleeing enemy, and our horses, which have no shoes, slip on the frozen ground and fall down, never to get up … My underclothes consist of three shirts and a few pairs of long socks; I’m afraid to change them because of the freezing cold. I’m eaten up with fleas and encased in filth, since my sheepskin never leaves me.’11

Under such conditions the army melted away quickly. By the end of the fighting around Krasny, Kutuzov had lost 30,000 men, and as many again had fallen behind, leaving him with only 26,500 available for action. Mitarevsky found that by the time they had reached Krasny almost all the reinforcements, men and horses alike, that he had received at Tarutino had died or fallen behind. Their morale was inevitably affected by the horrors they witnessed as they followed in the wake of the Grande Armée. ‘Despite their being our enemies and destroyers, our desire for revenge could not stifle feelings of humanity to the point where we could not pity their sufferings,’ wrote Radozhitsky. But he found Kutuzov’s bombastic proclamations a source of comfort and strength in his weariness and misery, likening them to ‘manna from heaven’.12

Kutuzov certainly had a better understanding of his soldiers’ needs than the parade-ground martinet Grand Duke Constantine, who had rejoined the army. Appalled at the sight of the dirty men wrapped in sheepskins, he held a review with the intention of smartening them up and appeared in full dress uniform without an overcoat in order to make his point. ‘He wanted to set an example, but we felt cold just looking at him,’ recalled Captain Pavel Pushchin of the Semyonovsky Life Guards.13

But even those soldiers who worshipped him ‘started saying that it would be good if our Field Marshal grew a little younger’, according to Mitarevsky. After allowing the French to slip through at Krasny, he held a service of thanksgiving instead of pressing on with the pursuit. The more merciful pointed to his age and his poor health – he was often bent double with lumbago and suffered from acute headaches; others speculated as to his true motives. Several in his entourage, perhaps repeating each other’s testimony (or possibly just their assumptions), report him as saying that his intention was not to destroy Napoleon but to provide him with ‘a golden bridge’ out of Russia. Wilson recorded a conversation in which he claimed the Field Marshal told him that by toppling Napoleon Russia would gain little, while Britain would take over as the dominant power in Europe, which would not be in Russia’s interests.14

Others, like Yermolov and Woldemar von Löwenstern, believed that what Kutuzov feared was a cornered and desperate Napoleon, even if he only had 30 or 40,000 fighting men with him. He knew that the Emperor was a better general than him, that his marshals and generals were superior to his own bickering subordinates, and that the soldiers of the Grande Armée would outfight his own, a huge proportion of whom were peasants who had been conscripted a couple of months before. Napoleon’s orders, written out by Berthier with the usual formality, still mentioned corps, divisions and regiments as though they were fully operational fighting forces, and since many of these orders were now falling into the hands of the Russians, Kutuzov could only have formed the impression that they were.15

The most probable explanation for Kutuzov’s behaviour is a combination of these motives. He hoped to wear Napoleon down further before taking him on. When he gave Yermolov a unit to command, he begged him to be prudent. ‘Little dove,’ he said with his usual familiarity, ‘be careful and avoid any actions in which you might suffer losses in men.’ He instructed Platov to harry the French and to ‘create incessant night alarms’.16 He himself would, by marching alongside them, force the French to hurry lest he cut them off, which would prevent them from regrouping.

Kutuzov was not the only one to err on the side of caution. Denis Davidov, a confident commander with a well-tried unit, would not take on anything more organised than a band of stragglers or an isolated platoon. Even when the retreating column looked temptingly disorganised, other Russian commanders took nothing for granted. ‘Groups of ten or twenty men would form up and refuse to let us scatter them,’ wrote Woldemar von Löwenstern. ‘Their bearing was admirable. We would let them continue their march and fall instead on other groups which did not put up any resistance.’ There was little point in the Russians exposing themselves, as they could take baggage and cannon without a fight, and as thousands of starving soldiers would come to their bivouacs at night to give themselves up anyway.17

Kutuzov probably preferred to take no chances and to wait until he could be certain of success. He was counting on the relatively fresh armies of Chichagov and Wittgenstein to cut off the French line of retreat along the Berezina. Napoleon’s forces would be weakened by fruitless attempts to break through, which would allow Kutuzov to come up from behind and take the Emperor himself. And if Napoleon should get away, it could be blamed on one or both of the other generals.

Chichagov, whose army of Moldavia had been swelled by Tormasov’s forces to a total strength of some 60,000 men, was moving fast to meet Napoleon head-on. On 16 November, the day Napoleon entered Krasny, the Admiral seized Minsk, Napoleon’s best-stocked supply base. He then carried on towards Borisov, where a Polish division under General Dabrowski was guarding the only bridge over the river Berezina. A couple of days’ march to the north, Wittgenstein hovered threateningly with his 50,000 men over Napoleon’s line of retreat, about halfway between Orsha and Borisov.

Although he still knew nothing about the fall of Minsk and assumed that Schwarzenberg was at least keeping Chichagov in check, Napoleon was nervous. ‘Things are going very badly for me,’ he said to General Rapp, whom he called to his side at one o’clock on the morning of 18 November at Dubrovna. According to Caulaincourt, he guessed that the Russians were planning to encircle him along the Berezina, and that that was why Kutuzov had so far avoided engaging him.18

That same day he sent urgent orders to Dabrowski to concentrate his forces at Borisov in order to protect the town and the crossing over the Berezina. He ordered Oudinot to join him there with his 2nd Corps and then move on to Minsk and make that safe. Victor was to make some feint attacks against Wittgenstein in order to give the impression that the Grande Armée was about to move against him. Napoleon realised that he could not afford to linger in Orsha as he had hoped to do, and decided to fall back on Minsk and try to hold the line of the Berezina.

‘Will we get there in time?’ he rhetorically asked Caulaincourt, and began turning over in his mind various plans for making a dash for it with what was left of the cavalry of the Guard. As if anticipating him, Chichagov had, on 19 November, published a physical description of Napoleon, with an injunction to all loyal subjects of the Tsar to apprehend him if he attempted to sneak through.19

Eager to cover the hundred kilometres that still separated him from Borisov, Napoleon moved from Orsha to Baran in the afternoon of 20 November, and it was there that he heard of Ney’s miraculous escape and appearance at the French outposts that morning. The news electrified the army. ‘Never has a victory caused such a sensation,’ recalled Caulaincourt. ‘The joy was universal; we were intoxicated; everyone was in motion, coming and going in order to announce the news; telling everyone they met … Officers, soldiers, everyone felt that neither the elements nor fortune could hurt us any more, and we felt that the French were invincible!’20 Although Napoleon is unlikely to have been quite so carried away, the news was welcome, and he appreciated its value as a morale-booster.

The distribution of rations at Orsha had brought a number of men back to the colours and the two-day pause had allowed stragglers to catch up. Those who had lost or thrown away their muskets were issued with fresh ones from the stores, which also contained sixty-two cannon. The remains of Ney’s corps were thus able to replace the equipment they had left behind on the bank of the Dnieper. As luck would have it, there was also among the supplies waiting at Orsha a convoy of wagons carrying a long pontoon bridge. This was of no apparent further use to Napoleon, but the hundreds of fresh horses were invaluable. Napoleon ordered the pontoons to be burnt and the horses given to the artillery.

The weather was fine, with a light frost and a blue sky, as the Grande Armée marched out of the town on 21 November, and the road was straight and even. While Caulaincourt’s assertion that Ney’s escape had ‘restored to the Emperor all the faith in his lucky star’ is perhaps a little wide of the mark, the whole army had been cheered, and ‘we set off once more with more gaiety’.21 It could hardly have been more misplaced.

The first leg of the retreat, between Maloyaroslavets and Smolensk, had been disastrous because it was unprepared in every way, and the arrival of the cold weather on 6 November had taken everyone by surprise. As the retreating columns struggled into Smolensk over the next three or four days, tens of thousands of men and horses died as much from undernourishment and exhaustion, both physical and moral, as from hypothermia: the temperature varied from –5°C (23°F) to not much lower than –12°C (10.4°F), which should have presented no problem to an organised army.

Even though the temperature dropped drastically while they were there, the army’s short stay in Smolensk did give the men an opportunity to adapt to the circumstances. They adjusted their clothing as best they could, jettisoned some of the more ambitious booty they had set out with, and in most cases tried to provide themselves with personal reserves of food and drink. The first hardships had killed off the least resistant and prompted the weak-willed to give themselves up to the Russians, leaving the more determined and resilient to continue the march. And these gradually grew more used to the cold and the lack of food, becoming more resistant with every day.22

The next stage of the retreat, the five-day march from Smolensk to Orsha, was executed in far more difficult conditions than the first, with the temperature varying from – 15°C (5°F) to – 25°C (—13°F) and regular Russian forces harrying every step. It was dominated by the fighting around Krasny, with each unit having to run the gauntlet. And although the French were generally victorious, the five days of fighting around Krasny had emasculated the army of Moscow. Possibly as many as 10,000 of the best soldiers had been killed or wounded, over 20,000 (many of them civilians) had been taken prisoner and more than two hundred guns had been lost.23

As it marched out of Orsha to continue its retreat, the remnant of the army of Moscow was left alone by regular Russian forces. But stragglers were harried by the ubiquitous cossacks and the detachments of Davidov, Figner and Seslavin, and even by bands of French deserters who had settled in this part of the country and were now withdrawing alongside the army. Conditions remained difficult, with weariness and uncertainty about the future sapping the will. In spite of this, a nucleus kept going, displaying an astonishing degree of resilience.

They would set off at first light, as the short winter days of the north gave them little marching time. ‘We were always in a hurry to leave the frozen bivouacs where we had spent the night, and the hope of being more comfortable on the following night gave us the strength to bear the fatigues of the day,’ according to Colonel Griois. ‘It is in this way that for almost two months the hope of an improvement which never came kept us from succumbing to exhaustion.’24

‘We pursued our road in silence; one could hear only the sound of horses being struck and the sharp but frequent curses of the drivers when they found themselves on an icy incline which they could not climb,’ wrote Cesare de Laugier as he left Smolensk. ‘The whole road is covered in abandoned caissons, carriages and cannon that nobody has even thought of blowing up, burning or spiking. Here and there dying horses, weapons, effects of every sort; broken-open trunks, disembowelled bags mark the way taken by those who precede us. We also see trees at the feet of which people attempted to build fires and, around these trunks, which have been transformed into funerary monuments, the bodies of those who expired while trying to warm themselves. At every step there are dead bodies. The drivers of wagons use them to plug ditches and ruts, to even out the road. At first, we shuddered at such practices, but we soon became accustomed to them.’25

‘With his head bowed, his hands dug deep into his clothes and his eyes fixed on the ground, each one sullenly and silently followed the unfortunate who walked ahead of him,’ recalled Adrien de Mailly. ‘The plaintive screech of the wheels on the hardened snow and the croaking of the swarms of crows, of northern rooks and other birds of prey which always followed our army were the only sounds we heard.’ B.T. Duverger, paymaster to the Compans division, draws a similar picture. At Krasny he had tried to sell the paintings he had looted in Moscow, all neatly rolled up, but there were no takers, so he dumped them in the snow next to a fine collection of books beautifully bound in red morocco which a friend had also tried to sell. He then followed the flow passively. ‘I was neither gay nor sad,’ he wrote. ‘I had become quite indifferent to the circumstances and had decided to accept whatever destiny held in store.’26

As they moved slowly, they did not cover much ground. But as they had to prepare shelter and fire for the night, they did not get much time to sleep either, and when they did their rest was interrupted by the need to keep the fire going or to move in order to keep warm. Dr Heinrich Roos noted that the younger soldiers, who needed more sleep, suffered this deprivation keenly, and that they were also prone to fall into such a deep slumber when they did get time to rest that they were more likely to freeze to death where they lay than older men.27

Every effort was made to keep the men together and under the colours. As the command of a given regiment stopped for the night, the drummers would start beating its signal. ‘This beating of the drum, dull in tone but audible a long way off, with its particular pattern of rolls and individual beats, slowing and quickening, made up a cadenced melody which was etched on the memory of the foot-soldier as distinctly as the sound of the village church bell on the ear of the rural inhabitant,’ explained Lieutenant Paul de Bourgoing of the Young Guard. ‘In time of war, the soldier has no other parish than his regiment, no church steeple other than his colours; when, lost in the night, exposed at every step to come up against enemy patrols or stumble into the midst of one of his columns, he can hear from far away the sound of the drum he recognises, and it is as though he heard a friendly voice egging him on through the murk and the distance.’28

Sensible men realised that their best chance of survival lay in staying with the colours, and even when regiments were all but destroyed, a kernel stuck together, sometimes no more than a couple of dozen men clustered around their colonel and their eagle. When the number fell below that, they would generally take measures to safeguard the colours. Dr La Flise watched as, just after Krasny, the handful of officers and men of the 84th of the Line left alive unscrewed the eagle from the top of the staff and, wrapping it carefully, strapped it to the Colonel’s back. Then, detaching the flag, they folded it and he buttoned it up under his uniform over his chest. After this they ceremonially embraced and set off, with the Colonel in the middle.29

Even cavalrymen who had lost their mounts and were obliged to follow on foot did everything to rejoin their mounted comrades for the nightly stop, although it meant making superhuman efforts, as they knew that they would find sustenance, both physical and emotional, among them. Some cavalry units decided to branch out and march parallel to the main road, as this made it easier for them to stay together. General Hammerstein took his remaining hundred West-phalian troopers off the road, and thanks to that kept them together successfully.30

Sergeant Bourgogne, who developed a fever after Krasny and fell behind his unit, provides a good example of what could happen to stragglers. He suddenly found himself walking alone along the road, in a gap between marching echelons, and although he was lucky enough not to encounter any cossacks, he saw many corpses of men who had evidently just been killed and stripped of their possessions. When a blizzard engulfed him he got lost and floundered despairingly through knee-deep snow, stumbling over the corpses of men and horses. He was famished, but could not hack away any part of the horse carcases he came across, since they were frozen rock-hard, and had to content himself with a handful of snow which had some horse’s blood in it. He was soon reduced to a whimpering wreck, and would have perished if he had not been rescued by a comrade.31

Even small gaps between the marching columns were dangerous, as the hovering cossacks were ready to pounce wherever there was no danger to themselves. A wagon whose harness broke and required a pause for repairs was virtually doomed if these could not be completed before the tail of the column it was marching in passed. A soldier or a small group who stopped to chop up a dead horse or make a fire were similarly liable to be taken.

The fate of prisoners grew more dire as the retreat continued into its second month. On their capture they would be robbed. The large numbers of irregular cossacks had no interest in the war beyond looting, and they took anything and everything that might possibly have some value. Towards the end of the campaign one could see cossacks with a couple of dozen fob-watches strung around their necks, wearing several rich uniforms and coats, bedecked with gold epaulettes, a variety of resplendent plumed hats, with an array of booty of every kind strung from their cushion-like saddles. In the baggage left behind at Krasny one cossack found Ney’s dress uniform, which he promptly donned, and thereafter French pickets were occasionally treated to the spectacle of what looked like a hirsute Marshal of France trotting up on a cossack pony and sticking his tongue out at them before galloping off.32

Regular cossacks, militia and even troops of the line also saw the war as a unique opportunity to make some money, and this included officers. They could not carry cumbrous booty, and would content themselves with money and valuables. So when the French surrendered to regular troops they were merely robbed of these. But this was of little comfort, as they would be relieved of everything else when they were handed over to the cossacks whose duty it usually was to escort them back into Russia.

Sub-Lieutenant Pierre Auvray of the 22nd Dragoons and four comrades had fallen behind on the march, and were captured by cossacks. ‘First they took my horse, which I had been fortunate enough to preserve from the rigours of the winter and which served to carry the personal effects of myself and my comrades,’ he wrote. ‘They looted our possessions and got hold of my portmanteau, which held some precious underclothes and a small box of jewels I had managed to procure in Moscow. Then they searched us and, finding no money on my person, they presumed that my wound must be concealing things that might satisfy their cupidity. They tore away my dressing with such violence that it caused me horrible pain. But so much suffering did not soften their hearts, and they undressed us and beat us with the wooden staves of their lances; we remained in this dreadful position in the snow, in this icy climate for some time, until the cossacks took fright at the approach of some French troops marching in force.’33

Major Henri Everts of the 33rd Light Infantry in Davout’s corps was taken prisoner at Krasny. He was stripped to the skin on the very battlefield by the Russian infantry to whom he had surrendered, and every single item of value was taken from him – they came to blows over his watch. When he and other officers were brought into the Russian camp they complained to an officer, and General Rosen found him an overcoat and gave him a drink in order to comfort him. The following day he set off in a column of 3400 prisoners, of whom no more than about four hundred reached the provincial town in which they were to be held. The escorting cossacks did not give them any food, and let the local peasants torment them whenever they stopped for the night.34

Colonel Auguste Breton, one of Ney’s aides-de-camp, was also taken at Krasny, having been wounded, but he was lucky in that he was taken under Milaradovich’s gaze. The Russian General actually bound his wound up himself before sending him off to Kutuzov’s headquarters, where the Field Marshal treated him amiably. But the moment he left headquarters he and his comrades were stripped and robbed by the escorting cossacks, who pocketed the money meant for the prisoners, gave them little food and took pleasure in gratuitous cruelty, such as not allowing them to drink when they reached a stream or not permitting them to make fires at night. Prisoners were force-marched, and if a man stopped to tie up his leggings or answer the call of nature he would be beaten and, if he did not rejoin the column fast enough, killed. They were sometimes given food and clothing by sympathetic landowners and even peasants as soon as they moved out of the area affected by the war, but this would often be taken from them by their escorts. Of one convoy of eight hundred, only sixteen were alive in June 1813.

As a rule, the later they were taken the worse the lot of the prisoners. When the cold became more intense, the cossacks found it amusing to strip prisoners and stragglers to the skin and leave them naked in the snowbound wilderness. The survival rate had never been good, but it grew much worse as the men were now weaker when taken and there was less food, clothing and shelter at the disposal of the Russians. And the further west they were taken, the longer the march back to the place of detention in Russia.

For many, the only hope of salvation was in establishing some connection that would take them out of the regular convoy. L.G. de Puybusque was captured by Platov’s men, not far from Orsha. Platov was impressed by Ney’s daring escape (and secretly delighted that Miloradovich had been made an ass of), and therefore treated him well. He was sent on to Yermolov’s headquarters, which was a stroke of luck. ‘I had met him in the drawing rooms of Paris,’ recalled Puybusque. ‘And although, by order of our respective sovereigns, we had become enemies, and I found myself among the vanquished, he was the first to remind me of the circumstances in which we had met, which so many others in his position would have pretended to have forgotten. If he allowed me to see the extent of his authority, it was only by giving many orders to ensure that I should enjoy while in his company all the advantages of the most generous hospitality, and that I should have all my needs and those of my companion in misfortune catered for.’

General Pouget, who had been the French military governor of Vitebsk, was fortunate enough to be taken not far from there, so that although he was robbed and beaten up by cossacks in the normal way on capture, he was then sent back into the city, where the inhabitants, to whom he had been fair and kind during his reign, interceded for him and recovered most of his possessions.35

For those remaining with the army the greatest affliction was now the cold, which added to their troubles at every level. Those fortunate enough to own a horse or carriage could not ride for long periods but had to dismount and walk in order to keep their circulation going. The roadway, churned up on a warmer day, turned into a terrifying ankle-twisting obstacle course and a lacerater of feet and worn boots when the ruts froze hard into jagged-edged canyons.

An unexpected consequence of the hard frost was that there was no water. Ice had to be melted over a fire, which meant that the labour involved in getting something to drink could be prodigious, requiring as it did both a fire and a vessel of some sort. Men and horses became dehydrated, which weakened them and contributed to their death – all the more effectively as they did not expect it at such a temperature.

This affected every function, as fingers grew clumsy and troops struggled with leather straps, harnesses and other pieces of equipment, which were stiff with cold. Even the soles of their boots had to be gradually softened, or they might snap. Men who walked to the side of the road and unbuttoned their pants in order to answer the call of nature, a frequent one since many of them had diarrhoea, would find to their horror that they were unable to button them up again. ‘I saw several soldiers and officers who could not button themselves up,’ wrote Major Claude Le Roy. ‘I myself helped to dress and button up one of these unfortunates, who was weeping like a child.’36

Another consequence of the cold was a plague of frostbite. Most of the men who made up the Grande Armée came from climates where this phenomenon is entirely unknown, and they could therefore neither take elementary precautions, recognise the signs nor react in the appropriate way. They would try to get as warm as possible in a cottage, or heat their hands and faces at a fire, before setting off into the cold, little realising that this only made the exposed parts more vulnerable. When they did feel a numbness or someone pointed out that their nose had gone a telltale white, they would naturally seek the warmth of a house or rush up to a fire. This would induce instant gangrene. The affected part of the body would go a livid hue of purple and snap off as the sufferer tried to rub it. The only way of preventing damage of this sort is by rubbing the afflicted part vigorously with snow until circulation is restored, attended by excruciating pain. But few, apart from the Poles, the Swiss and some of the Germans, knew this, with terrible consequences. ‘To amuse the ladies, you can tell them that very probably half their acquaintances will return without noses or ears,’ Prince Eugène wrote to his wife.37 But it was no laughing matter.

Captain François watched in disbelief as one of his friends unwrapped his feet from his improvised footwear as they settled down for the night. ‘As he took off the cloth and leather in which they were wrapped, three toes came away,’ he wrote. ‘Then, removing the rags from the other foot, he took the big toe, twisted it and tore it off without feeling any pain.’38 Once a man had lost all his toes, he could no longer walk without assistance; once he had lost his fingers, he was not only incapable of handling weapons, he could not get at any food, other than by tearing at the carcase of a horse with his teeth and sucking its blood.

The freezing temperatures made even this impossible. The horses, which had managed to keep going by eating tree bark and any bush or weed that pierced through the snow and by munching snow where there was no water, could not tear off the frozen bark or crunch the ice, so they died in their thousands. But a dead horse became rock hard in minutes, and its meat could not be cut up. So it was essential to find one that was still alive in order to be able to cut meat out of it.

It was but a short step from there to slicing steaks off a horse’s hindquarters while its owner was not looking. The beasts did not feel the pain on account of the cold, and the blood froze instantly. They could carry on for days with such gashes in their hindquarters, but eventually the wounds would fester and start oozing pus, which itself froze. Another resource was to cut a horse’s vein and suck out the blood, or collect it in a vessel and boil it up with melted snow to add nourishment to some thin gruel. Some would cut out and devour the tongue of the still-living horse. But the best nourishment was to be had by ripping open its belly and tearing out its heart and liver while they were still warm, and this was what increasingly befell those which, unable to go any further, were abandoned by their owners.39

From the moment the retreating army passed Ladi it was in former Polish lands, which meant the towns and villages were inhabited. Even in these dire times the ubiquitous Jewish shopkeepers could be relied on to lay their hands on the necessities of life – but only at a price. And the inhabitants were fearful of accepting anything which, if found in their possession later, might lay them open to reprisals on the part of the Russians.

Most currencies had lost their value. Dr Heinrich Roos remembered seeing a Württemberg soldier sitting by the roadside outside Orsha with a silver ingot in his lap, begging to exchange it for the slightest scrap of food, but nobody was prepared to part with lifesaving rations in order to acquire a heavy piece of currency which would only have worth once he had got home. The only reaction he elicited from the men shuffling past him was a litany of cruel jokes. Even the last resort of the women – prostitution – was proving worthless in the circumstances. ‘There was no amorous intent in my action,’ Boniface de Castellane noted after having given a woman some chocolate. ‘We are all so tired that everyone is saying they would rather have a bottle of bad Bordeaux than the prettiest woman on earth.’40

Those who did not manage to remain with their colours and had no money were obliged to pilfer. With the loss of so much of the baggage, the scope for this was greatly reduced, so the thieving often turned into violent robbery, and many a man was killed for a horse’s liver, a crust of bread or any other kind of food. An isolated man with something to eat would carefully choose his moment to consume it when nobody was watching, otherwise he might get a bayonet in the back. But by the time Colonel Lubin Griois had found a safe place to consume the wonderful little loaf of white bread he had miraculously managed to acquire, it was frozen rock hard, and he wept as his teeth scraped ineffectually on the crust.41

Outside the units which had stayed together, all sense of camaraderie and solidarity had vanished. The various nationalities grew more resentful of each other, with the Germans cursing the French for having dragged them into the war, and the French cursing the Poles for supposedly being its cause. In the struggle for survival another’s life meant nothing. ‘Many times, the implacable, frenzied rabble would shoot at each other when looting, when foraging, over a place to sleep, over a bowl of milk, over a shirt, over a pair of worn-out shoes,’ wrote Lieutenant Józef Krasinski.42

Anything left unguarded for a moment would vanish. An officer walking along with his horse’s rein passed through his arm would look around to find that the rein had been cut and the horse taken. Men had their hats stolen from under their heads and the cloaks which covered them purloined as they slept. The length of the retreat and the loss of the baggage meant that their clothing, inadequate from the start, had reached a critical condition.

‘My socks had given out a long time ago; my boots were worn out and all but sole-less; I had swathed them in straw which, with the aid of pieces of string, held the whole thing just about together,’ wrote Julien Combe. ‘My grey trousers and my uniform jacket were holed and worn threadbare, and I had been wearing the same shirt for the past month.’ To ward off the cold, Jean-Michel Chevalier, an officer in the Chasseurs à Cheval of the Guard, wore a flannel vest under his shirt, four waistcoats, one of them of sheepskin, his uniform, a frock-coat and a large cloak, four pairs of trousers or breeches over his underpants, and a bearskin busby.43 But so many layers made walking, let alone fighting, difficult.

Colonel Griois was more sensible. Under his shirt he wore a flannel vest. His uniform consisted of a red woollen waistcoat, woollen trousers with no underwear, a tailcoat of light wool, and a light overcoat. On his feet he wore a pair of calf-high boots and cotton socks. He managed to get hold of an additional overcoat, but this was stolen. He tried to wear the bearskin cloak he had acquired in Moscow, but while this was excellent for sleeping in, it was far too heavy to march in. He therefore let his horse carry it during the day. But he did cut a strip off it to fashion into a muff, which he suspended from his neck by a string. He used another strip of the bearskin as a muffler, attached by string at the back of his head. ‘It is in this singular array, my head barely covered by a hat in shreds, my skin chapped by the cold and blackened by smoke, my hair covered in hoar frost and my moustaches bristling with icicles, that I covered the two or three hundred leagues from Moscow to Königsberg, and, in the crowd which flowed along the road, I stood out as one of those whose costume still conserved something of the uniform; the majority of our unfortunate companions looked more like ghosts dressed up for a masquerade. If they had kept elements of their military dress, one could not see it, covered as they were by the warmest clothing they could find. Some, lucky enough to have preserved their greatcoat, had turned it into a kind of habit with a hood, tied around their body with a piece of string; others had used woollen blankets or women’s skirts for the same purpose. Many wore on their shoulders women’s pelisses lined with precious furs, relics from Moscow and originally intended for sisters and mistresses. There was nothing at all unusual in seeing a soldier with a blackened and disgusting face dressed in a coat of pink or blue satin, lined with swansdown or Siberian fox, scorched by campfires and covered in grease stains. Most of them had their heads wrapped in filthy kerchiefs under the remains of forage caps, and in place of their worn-out footwear they had strips of cloth, blankets or leather. And it was not only the common soldier whom misery forced to such travesty. Most of the officers, colonels, generals were dressed in ways no less ridiculously beggarly, and one day I saw Colonel Fiéreck wrapped in an old soldier’s greatcoat and wearing on his head, on top of his forage cap, a pair of breeches buttoned under his chin.’44

Much of this carnivalesque frippery was quite useless, and those who survived best were often those who were most sensibly dressed. ‘I had no fur over my uniform, only a blue wool cloak with a very worn collar,’ wrote Planat de la Faye. ‘My boots, which I did not take off after Smolensk, had holes in their soles; and to protect my ears I had tied around my head a cambric kerchief, which had become as black as the shako which I kept over it. It is in this attire that I made the whole retreat, and yet I did not suffer any frostbite.’45

It goes without saying that these clothes were in most cases in shreds and covered in dirt, as were the men, although some made heroic efforts to shave and keep clean. Their faces were filthy, blackened with smoke and smeared with the blood of the animals they ate, with long beards covered in hoar frost which hid the remains of food and saliva. ‘The most ragged beggars inspire pity, but we could have inspired only horror,’ wrote Colonel Boulart.46

They were also crawling with lice. ‘As long as we were out in the cold and walking,’ wrote Carl von Suckow, ‘nothing stirred, but in the evening, when we huddled round the campfires life would return to these insects, which would then inflict intolerable tortures on us.’ Colonel Griois also remembered the unpleasant duty that had to be got through every evening. ‘While our tasteless pottage was on the fire, we would take advantage of this first moment of rest to hunt down the vermin with which we were covered,’ he wrote. ‘This kind of affliction, which one has to have experienced in order to have an idea of it, had become a veritable torture which was made all the more powerful by the disgust which it inspired. In spite of all the precautions of cleanliness available on campaign, it is almost impossible, when one has to remain for several days and often entire weeks on end without leaving one’s clothes, to preserve oneself entirely from these inconvenient guests. So from our very entry into Russia few of us had escaped this disagreeable inconvenience. But from the beginning of the retreat it had become a calamity; and how could it have been otherwise as we were obliged, in order to escape the deathly cold of the nights, not only not to take off any of our clothes, but also to cover ourselves with any rag that chance laid within our reach, since we took advantage of any free space by a bivouac which had been vacated by another, or in the miserable hovels in which we were able to find shelter? These vermin had therefore multiplied in the most fearful manner. Shirts, waistcoats, coats, everything was infested with them. Horrible itching would keep us awake half of the night and drive us mad. It had become so intolerable that as a result of scratching myself I had torn the skin of a part of my back, and the burning pain of this horrible and disgusting wound seemed soothing by comparison. All my comrades were in the same condition, and we showed no shame in our dirty searches and could perform them in front of each other without blushing.’47

Such delicacy marks him out – it should not be forgotten that the overwhelming majority of the men marching down that road had been plucked from the most primitive backgrounds. Whatever feelings of shame they might have entertained vanished as quickly under the strain as their strength of character.

Some became helpless sheep, swept along in the general flow, incapable of helping themselves. In the evenings they would stand behind those who had made themselves campfires and were sitting around them. ‘Soon they would flag under the weight of fatigue, fall to their knees, then sit and then involuntarily lie down,’ wrote Louis Lejeune. ‘This last movement would be for them the precursor of death; their dull eyes would look up to heaven; a happy grin would convulse their lips; and one might have thought that a divine consolation was attenuating their agony, which was betrayed by an epileptic salivating.’ Hardly had that man died than another would come and sit down on his body, until he too fell into a stupor and died.48

Indifference to the suffering of others became general. Jean-Baptiste Ricome, a twenty-three-year-old sergeant, recalled how at the start of the retreat he felt agonies of pity when he heard dying men calling for their mothers, and how the familiarity of such cries gradually bred indifference. The struggle for survival hardened the kindest hearts, and men trudged on as their comrades slipped and fell on the ice. ‘In the beginning, they would find help,’ wrote Colonel Boulart, ‘but as the same fate threatened everyone and the frequently repeated falls suggested the futility of assisting them, one passed by these hapless men, who lay on their bellies on the ice, making vain efforts to get up, or scratching the ground in front of them as they battled with death, and one did not stop!’49

‘This campaign became all the more frightening as it affected our very nature, giving us vices which had until then been unknown to us,’ wrote Eugène Labaume. On one occasion several hundred men crammed themselves into a large barn for the night, in the course of which the fires they had made set fire to the thatch of the roof and eventually to the whole structure. The rapidity with which the blaze spread made it impossible to save more than a couple of dozen, and the rest perished, saluted only, as Colonel Lejeune observed, by the discharges of the cartridges going off in their loaded muskets. Comrades who had rushed to their aid could only look on in horror. But within a couple of weeks they would simply come up and warm themselves when this kind of thing happened. Such fires were sometimes started on purpose out of miserable fury by men who could find no shelter, and those who stood around warming themselves would make jokes about the quality of the fire.50

One night Davout’s headquarters found shelter in a large peasant cottage in a deserted village, only to discover that there were three babies still alive lying in the hay in the stable shed, wailing from hunger. Colonel Lejeune told Davout’s butler to give them something to eat, which he did. The babies nevertheless continued to wail, preventing them all from sleeping. Lejeune did fall asleep, and when he awoke it was time to move off. As all was quiet he did not think of the babies, but when he enquired about them of the butler later that day he was told that, being able to stand it no longer, he had taken an axe, broken the ice on the drinking trough and drowned them.51

According to Captain François, ‘Anyone who allowed himself to be affected by the deplorable scenes of which he was a witness condemned himself to death; but the one who closed his heart to every feeling of pity found strength to resist any hardship.’ It certainly took character, as well as fitness, to survive. ‘A small number of us, with exceptionally strong characters, supported by youth and a solid constitution, resisted all the elements conspiring to our destruction and came out of it well,’ wrote Louis Lagneau, a surgeon with the Young Guard. ‘I was thirty-two years old, my health was perfect, I was very used to walking long distances, and as a result I bore everything without any unfortunate results.’52

Another who bore it all remarkably well was Napoleon himself. He did have the benefit of a regular supply of food and wine, not to mention other comforts. An officer would ride ahead to select a place for the Emperor to stop for the night, which, be it a devastated country house or a peasant hovel, would be made amenable. The iron camp bed would be set up, a rug spread on the floor and the nécéssaire containing razors, brushes and toiletries brought in. A study would also be improvised, in the same room if no other could be found, with a table covered in green cloth, the Emperor’s travelling library in its case and the boxes containing maps and writing instruments. A small dinner service would be unpacked so that he could eat off plate.

‘He bore the cold with great courage,’ recalled his valet, Constant, ‘but one could see that he was physically very affected by it.’ Even though he did have the luxury of a change of clothes, and despite the resources of the nécéssaire, Napoleon also had lice. And despite the comfort of his camp bed, he suffered from insomnia – no doubt caused by uncertainty as to what lay ahead and a feeling of responsibility for his army. ‘Those poor soldiers make my heart bleed, yet I can do nothing for them,’ he said to Rapp one evening.53

Their faith in him remained unshaken. Many grumbled and cursed him, but while some became insolent and insubordinate with their officers and even with generals, they would fall silent and respectful whenever he appeared. ‘Soldiers lay dying all along the road, but I never heard one complain,’ recalled Caulaincourt. ‘Although this man was, rightly, regarded as the author of all our misfortunes and the unique cause of our disaster,’ wrote Dr René Bourgeois, who held profoundly anti-Napoleonic political views, ‘his presence still elicited enthusiasm, and there was nobody who would not, if the need arose, have covered him with their body and sacrificed their lives for him.’ The degree of their devotion is well illustrated by Sergeant Bourgogne, who watched as an officer accompanied by a couple of grenadiers came up to a bivouac asking for some dry wood for Napoleon. ‘Everyone eagerly proffered the best pieces he had, and even those men who were dying raised their heads to whisper: “Take it for the Emperor!”,’ he recalled. Such devotion was not universal, it is true. On one occasion when Napoleon wanted to stop and warm himself by a fire surrounded by stragglers, Caulaincourt walked over to them but, after exchanging a few words, came back suggesting that perhaps it might not be a good idea to stop there.54

Paymaster Duverger, who not being a combatant felt nothing of the soldier’s devotion to his chief, still agreed that ‘his prestige, that kind of aura that surrounds great men, dazzled us; everyone gathered in confidence and obeyed the slightest indication of his will’. It is true that Napoleon represented their best chance of getting out of the mess they were in. ‘His presence electrified our downcast hearts and gave us a last burst of energy,’ wrote Captain François. ‘The sight of our overall chief walking along in our midst, sharing our privations, at some moments even brought out the enthusiasm of more victorious times.’ Whatever their nationality, and whatever their political attitude to him, men and officers alike realised that only he could keep the remains of the army together, and that only he was capable of snatching some shreds of victory from the jaws of defeat.55

But there was more to it than that. A German artillery officer who might have been expected to curse the foreign tyrant who had brought him to this as he tramped past Napoleon, standing at the side of the road, expressed feelings which, surprising as they were, were not uncommon. ‘He who sees real greatness abandoned by fortune forgets his own suffering and his own cares, and as a result we filed past under his gaze in gloomy silence, partially reconciled to our harsh fate.’56

Ségur sought a metaphysical explanation of this phenomenon. They should have blamed Napoleon but did not because he belonged to them as much as they to him, he argued. His glory was their common property, and to diminish his reputation by denouncing him and turning away from him would have been to destroy the common fund of glory they had built up over the years and which was their most prized possession. This seems to be borne out by the fact that even when they were taken prisoner, the soldiers of the Grande Armée refused to say a word against Napoleon. According to General Wilson, they ‘could not be induced by any temptation, by any threats, by any privations, to cast reproach on their Emperor as the cause of their misfortunes and sufferings’.57

Spirits rose when, as they approached Borisov, the army of Moscow met up with Oudinot’s 2nd Corps and other units that had been stationed in the rear and had therefore not suffered all the rigours of the retreat. Lieutenant Józef Krasinski, retreating with the bedraggled remnants of the Polish 5th Corps, burst into tears of joy when he saw Dabrowski’s division near Borisov, properly uniformed and marching behind its band. Reactions on the other side were correspondingly painful.

Grenadier Honoré Beulay, who had only recently marched over from France, was incredulous as he watched the retreating units tramp by. ‘We stood there with our mouths open, wondering whether we were not mistaken, whether these men who hardly resembled human beings were really Frenchmen, soldiers of the Grande Armée!’ he wrote. The appearance of the army of Moscow had an unsettling effect on Oudinot’s and Victor’s corps. ‘It had been hoped that our example would exert a salutary influence,’ noted Oudinot. ‘Alas! it was quite the opposite that prevailed.’58

What was far more unsettling, however, were the terrifying rumours that flew through the army to the effect that Borisov had fallen to the Russians and that they were now cut off.

* Davout’s ceremonial uniform fell to a couple of officers who happened to be brothers, and they sent it home to their mother, who in turn donated it to the local church, where the gold braid was unpicked and used for a new chasuble.2