On 22 November Napoleon reached Tolochin, where he took up quarters in a disused convent. He had not been there long when he heard, from a rider sent by Dabrowski, that Minsk had fallen to Chichagov six days before. ‘The Emperor, who by that one stroke lost his supplies and all the means he had been counting on since Smolensk in order to rally and reorganise his army, was momentarily struck with consternation,’ according to Caulaincourt.1

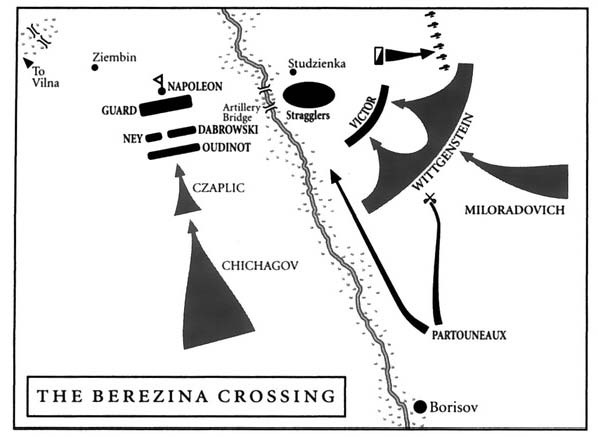

He had been expecting Chichagov to manoeuvre himself into a position to be able to join up with Kutuzov so they could attack him with overwhelming force, not to move into his rear and attempt to cut him off. As it happens, Chichagov was operating in the dark. He had received only scanty orders from Kutuzov, who had instructed him to move into Napoleon’s rear and to prevent the French from linking up with Schwarzenberg. Wittgenstein was supposed to cross the Berezina further north and link up with him, so that between them they covered a long stretch of the western bank of the river.2

That night Marshal Duroc and Intendant Daru were on duty at the Emperor’s bedside, and the three of them sat up late. They discussed the situation at length, and Napoleon allegedly reproached himself for his own ‘foolishness’. He dozed off for a while, and when he woke he asked them what they had been talking about, to which they answered that they had been wishing they had a balloon. ‘What on earth for?’ he asked. ‘To whisk Your Majesty away,’ one of them replied. ‘The situation is not an easy one, it is true,’ he admitted, and they discussed the possibility of his falling into Russian hands. General Grouchy was instructed to gather all the cavalry officers who still had good mounts into a ‘dedicated squadron’ whose purpose would be to spirit Napoleon to safety in an emergency. But the Emperor remained sanguine, and if he did order the burning of some state papers before they set off in the morning, that was more to lighten the load than anything else – he also ordered the burning of more non-essential carriages. He appeared confident that he would be able to fight his way through.3

What he did not know was that while he was digesting the news of the fall of Minsk, Borisov had also fallen to Chichagov. The Admiral, who had a healthy respect for him, was apparently unaware that he was on a collision course with Napoleon, whose whereabouts he did not know, but whose forces he assumed to be at least 70,000. In the event, his advance guard had moved quickly, surprised and defeated the detachment of Dabrowski’s division holding the bridgehead on the western bank of the Berezina and swept into Borisov itself, which it occupied after a stubborn resistance. The Russians then made themselves at home, and their commander, Count Pahlen, sat down to a copious dinner. He had hardly swallowed a mouthful when the alarm was sounded. An advance unit of Oudinot’s corps, consisting of five hundred men of Colonel Marbot’s 23rd Chasseurs à Cheval, had burst into the town and fallen upon the unsuspecting Russians. No more than about a thousand of them managed to save themselves by fleeing back across the river, leaving behind up to nine thousand dead, wounded and prisoners, ten guns and all their luggage.4

But the fleeing Russians had had the presence of mind to fire the long wooden bridge, the only crossing over the Berezina. Napoleon had reached Bobr when he heard of this, and he must have rued the decision to burn the pontoon bridge at Orsha three days before. The boggy trough of the Berezina ran between him and freedom; cold as it was, a slight thaw had broken up the ice on it, and it represented a considerable obstacle. ‘Any other man would have been overwhelmed,’ wrote Caulaincourt. ‘The Emperor showed himself to be greater than his misfortune. Instead of discouraging him, these adversities brought out all the energy of this great character; he showed what a noble courage and a brave army can achieve against even the greatest adversity.’5

Napoleon momentarily entertained a plan to gather up all his forces, march northwards, knock out Wittgenstein and then make for Vilna, bypassing the Berezina altogether. But he was advised that the terrain was unfavourable for such operations. Instead, he decided to fight his way across the river at Borisov. This would involve repairing the existing bridge and building new ones under enemy fire. In order to reduce the resistance, he decided to disperse Chichagov’s forces by giving him the impression that he was planning to cross elsewhere. He sent a small detachment southwards to make a demonstration of activity at a possible crossing point further downstream, and even managed to misinform some local Jewish traders that he was intending to cross there, expecting them to pass the news on.6

Everything depended on speed: Wittgenstein and Kutuzov would be coming up behind him in a couple of days, and what would happen if he were caught in the rear by them while attempting to force a passage across the river did not bear thinking about. Napoleon seemed to be energised by the crisis, and did not appear downcast. ‘The Emperor seemed to have made his mind up with the calm resolve of a man about to embark on an act of last resort,’ noted his valet, Constant.7

The forward units and large numbers of fugitives poured into Borisov on the night of 23 November. The town was strewn with dead bodies and debris from the previous night’s fighting. ‘This countless mass of wagons, with women, children, unarmed men had packed into Borisov in the conviction that the bridge would be repaired and that the crossing would be made there,’ wrote Józef Krasinski of Poniatowski’s 5th Corps, which had also entered the town. ‘The streets of Borisov were so jammed with this wagon train that it was impossible to pass through them without pushing and crushing people. As a result the streets were covered in mauled bodies, shattered wagons, smashed baggage, and all one could hear were shouts, calls, wails and lamentation … I remember that on one of the streets I pulled from beneath the horses’ hooves a baby lying in the middle of the road in its swaddling clothes, and further along I saw, by a small bridge, a cantinière’s wagon lying in the water into which it had been pushed by the French troops marching before us, and on that wagon the poor woman with a child in her arms was calling for help which none of us could give her.’8

When General Eblé and his pontoneers reached Borisov and saw the state of the river they were discouraged. It was wider than they had anticipated, and the recent thaw meant that large blocks of ice were being swept down it by a slow but strong current. General Jomini, who was with Eblé, suggested that they cross further north, at Vesselovo, where there had been a bridge which might still be standing. But Oudinot had already identified a better place. One of his cavalry brigades, General Corbineau’s, which had been clearing the western bank of the Berezina of cossacks during the previous week, had just rejoined his corps having found a ford by the village of Studzienka, a dozen kilometres upstream from Borisov.

Oudinot had immediately informed Berthier of the existence of the ford, recommending it as the best place for a crossing. But Napoleon stuck to his intention of forcing a passage at Borisov, meaning to defeat Chichagov and then make a dash for Minsk, from where he hoped to be able to make contact with Schwarzenberg. From Loshnitsa at 1 a.m. on 25 November he repeated his orders to Oudinot, urging him to make haste so they could start crossing that very night. Oudinot, who had already ordered some of his units to Studzienka in anticipation, begged Napoleon to reconsider, and sent Corbineau to see him in person. It was only after he had discussed the matter with Corbineau that Napoleon accepted Oudinot’s suggestion, and he set off for Studzienka himself late that night.9

A few hours earlier, Chichagov had moved off with his main forces in the opposite direction along the other bank of the river. He had been anxious about the possibility of Napoleon outflanking him to the south, and the combination of the reports of French activity to the south of Borisov and the information brought to him by three Jews from Borisov convinced him that this was indeed where the French were planning to cross. He left General Langeron with 1200 infantry and three hundred cossacks at Borisov, and General Czaplic with a few hundred men between there and Vesselovo, while he marched off southwards with the rest of his forces. When the first reports of French activity around Studzienka did reach him on the following day, he assumed this to be a feint meant to deceive him, and continued on his way. The course of the Berezina north of Borisov should in any case have been covered by Wittgenstein, and he had left orders with Czaplic to pull back his outlying units in the area.

But Wittgenstein had no intention of placing himself under Chichagov’s orders, which he would have had to do if he had linked up with him on the western bank. And he too was less than eager to take on Napoleon himself, preferring to spar with Victor, so he ignored Kutuzov’s orders to cross the river and cut the French line of retreat. In doing so he not only left the Berezina itself unguarded, he did not, as would have been the case if he had followed his orders, cover the other point at which Napoleon’s retreat could have been cut. A few kilometres west of the Berezina, at Ziembin, the road ran through a boggy area along a number of wooden bridges, and could effectively be cut by a platoon of cossacks with a tinderbox.10

Oudinot had sent General Aubry with 750 sappers to Studzienka on 24 November to start making struts for a bridge, and followed with his main forces on the evening of the following day. They were joined there by General Eblé with four hundred pontoneers, mostly Dutchmen. Although Napoleon had ordered the pontoon bridge they were accompanying to be burnt at Orsha, Eblé had wisely hung on to six wagons of tools, two field smithies and two wagons of charcoal. The sappers dismantled the wooden houses of Studzienka, sawing the thick logs into appropriate lengths, while the pontoneers forged nails and braces, and turned the logs into trestles.11

The riverbed itself, which at this point is less than two metres deep, is no more than about twenty metres across, but its banks are low and boggy, and cut by shallow arms of the main river, so any bridge would need to extend for some distance at either end. A major disadvantage of this as a crossing point was that the western bank, held by the Russians, rose steeply, and any troops occupying it would be in a position to rake the crossing with artillery fire.

Oudinot had placed his men behind a small rise, so they would be out of sight of the cossacks patrolling the western bank, and instructed them to work in silence. But Captain Arnoldi, commanding the Russian field battery of four light guns that had been positioned by General Czaplic to observe the possible crossing points near Studzienka, noticed the French activity on the opposite bank and sent urgent reports to his superior warning that they were preparing to cross the river there. He convinced Czaplic, who came to see for himself and then sent a messenger to Chichagov.12

For his part, Oudinot stayed up all night, urging on the sappers and pontoneers, and nervously watching the other bank. ‘The aspect of the countryside was gripping; the moon lit up the ice floes of the Berezina and, beyond the river, a cossack picket made up of only four men,’ noted François Pils in his journal. He was a grenadier in Oudinot’s corps, but in civilian life he was a painter, which explains his sensitivity to the view. ‘In the distance beyond, one could see a few red-tinged clouds seemingly drift over the points of the fir trees; they reflected the campfires of the Russian army.’13

The magnificent sight left Ney, for one, cold. ‘Our position is impossible,’ he said to Rapp. ‘If Napoleon succeeds in getting out of this today he is the very Devil.’ Murat and others were putting forward various plans to save the Emperor by sending him off with a small detachment of Polish cavalry while the rest of them made a heroic stand. ‘We shall all have to die,’ he affirmed. ‘There can be no question of surrender.’14

In the early hours of the next morning, 26 November, the troops sitting around the Russian campfires began to withdraw, and Arnoldi’s four guns were limbered up and dragged away. Oudinot could hardly believe his eyes. Napoleon, who had reached Studzienka a little earlier, was jubilant: according to Rapp, his eyes sparkled with joy when he saw that his ploy had worked and Chichagov was off on his wild goose chase.

He ordered Colonel Jacqueminot to muster a squadron of Polish lancers and some Chasseurs, each of whom was to take a voltigeur riding pillion, and ford the river. Once across, the riders fanned out and, followed by the voltigeurs, chased off the few remaining cossacks and took possession of the west bank. Captain Arnoldi, who had clearly seen the French set up a battery of forty guns to cover both banks of the river, had sent a final despairing report to headquarters before withdrawing, expressing his conviction that this was the spot they had chosen for their crossing. But while Czaplic had delayed carrying out the order to withdraw, he did not dare defy it outright. Nor did he have the sense to send a troop of cavalry to hold and, if need be, burn the bridges at Ziembin.15

Shortly after the withdrawal of the Russians, at eight o’clock, Captain Benthien and his Dutch pontoneers waded into the icy water and began installing the first trestles. They had stripped down to their pants, and struggled manfully in the strong current, which was carrying with it great blocks of ice up to two metres across. Every so often one of them would lose his foothold on the slimy riverbed and be swept away. They were only allowed to remain in the water for fifteen minutes at a time, but many nevertheless succumbed to hypothermia. They had been offered a bonus of fifty francs per man, but that was surely not the motive that drove them. ‘They went into the water up to their necks with a courage of which one can find no other example in history,’ recorded grenadier Pils. ‘Some fell dead, and disappeared with the current, but the sight of such a terrible end did nothing to weaken the energy of their comrades. The Emperor watched these heroes without leaving the riverbank, where he stood with the Marshal [Oudinot], Prince Murat and other generals, while the Prince de Neuchâtel [Berthier] sat on the snow expediting correspondence and writing out orders for the army.’16

‘At this solemn moment Napoleon himself recovered all the elevation and energy that characterised him,’ recalled Lieutenant Colonel de Baudus. There are accounts of him looking dejected, and the story of his ordering the eagles of the Guard to be burnt in a fit of despair surfaces here and there. But most witnesses agree that he displayed remarkable self-possession throughout what continued to be a knife-edge situation, and far from ordering the eagles to be burnt, kept enjoining the men to cling to them in order to keep the semblance of a fighting force in existence. Some thought he actually appeared detached as he stood on the riverbank watching the pontoneers at their work.17

Major Grünberg, a cavalryman from Württemberg, was struck by this as Napoleon caught sight of him marching past, carrying in the folds of his cloak his beloved greyhound bitch. The Emperor called him over and asked if he would sell the animal to him. Grünberg replied that she was an old companion whom he would never sell, but that if His Majesty so wished, he would give her to him. Napoleon was touched by this and replied that he would not dream of depriving him of such a close companion.18

The bridge was completed around midday. It was just over a hundred metres long and about four metres wide, and rested on twenty-three trestles varying in height from one to three metres. There was not enough planking available, so the round logs laid across the top which made up the causeway were covered with flimsy roof slats taken from the houses of Studzienka topped with a dressing of bark, branches and straw. ‘As a work of craft, this bridge was certainly very deficient,’ noted Captain Brandt. ‘But when one considers in what conditions it was established, when one thinks that it salvaged the honour of France from the most terrible shipwreck, that each of the lives sacrificed in the building of it meant life and liberty to thousands, then one has to recognise that the construction of this bridge was the most admirable work of this war, perhaps of any war.’19

Napoleon, who had hurriedly swallowed a cutlet for breakfast while standing on the bank, walked over to the head of the bridge, where Marshal Oudinot was preparing to march his corps across. ‘Do not cross yet, Oudinot, you might be taken,’ the Emperor called out to him, but Oudinot waved at the men drawn up behind him and answered: ‘I fear nothing in their midst, sire!’20 He led his corps across, to shouts of ‘Vive l’Empereur!’ uttered with a conviction that had not resounded in the imperial presence very often of late. Turning left, he began to deploy his troops in a southerly direction in order to ward off any potential attack by Chichagov. They were quickly lost to sight in the snow that had begun to fall again.

Meanwhile Captain Busch and another team of Dutch pontoneers had been working on a second bridge, fifty metres downstream of the first. This one, built on sturdier trestles and with a causeway of plain round logs, was intended for the artillery and baggage, and it was ready by four o’clock in the afternoon.* While troops continued to trudge across the lighter bridge in an orderly fashion, Oudinot’s artillery, followed by the artillery of the Guard and the main artillery park, trundled across the other. At eight o’clock that evening two of the trestles of the heavy bridge subsided into the muddy bed of the river, and the pontoneers had to abandon their firesides, strip off and wade into the water once again. The bridge was reopened at eleven o’clock, but at two in the morning of 27 November three more trestles, this time in the deepest part of the river, collapsed. Once again Benthien’s men abandoned whatever shelter they had found for the night and went into the water. After four hours, at six in the morning, the bridge was operational once more.

For the whole of that day the Grande Armée trudged across the Berezina in the lightly falling snow. The Guard began crossing at dawn, then came Napoleon with his staff and household, then Davout with the remainder of his corps, then Ney and Murat with theirs, then, in the evening, Prince Eugène, with the few hundred remaining Italians of the 4th Corps. The bridge was low, barely above the level of the water, and it swayed, so the men crossed on foot, leading their horses. The surface coating of branches and straw had to be firmed up by the sappers from time to time. Even so, the bridge subsided in places, and those crossing it sometimes had water up to their ankles. The sheer weight of numbers and the state of the bridge meant that there was some pushing and shoving, men fell over and horses collapsed, causing obstructions and leading to fights. It was not a pleasant crossing.

Meanwhile a steady flow of guns, caissons, supply wagons and carriages of every kind trundled across the other bridge, with a two-hour interruption while the pontoneers repaired two more broken trestles at four o’clock that afternoon. Here too there were jams and outbreaks of violence. The surface of the bridge was scattered with debris and corpses, and a number of horses broke their legs by getting them caught between the round logs making up the causeway. The next vehicles, themselves being pushed on from behind, would try to drive over the struggling and kicking horses rather than stop and wait for them and their vehicles to be heaved over the side. But most of the guns and materiel of the organised units, the treasury, the wagons carrying Napoleon’s booty from Moscow, and a surprising number of officers’ carriages made the crossing successfully. Madame Fusil, the actress from Moscow, drove across in the relative comfort of Marshal Bessières’ carriage.21

The approaches to the bridges were guarded by gendarmes who only allowed active units onto them and ordered all stragglers and civilians, and even wounded officers travelling in various conveyances, to wait. A large number of these non-combatants had begun to arrive in the late afternoon of 27 November, cluttering the approaches to the bridge. As they could not cross immediately they settled down, built fires and began to cook whatever they had managed to pick up, scrounge or steal.

Victor’s 9th Corps also arrived in the late afternoon and took up defensive positions covering the approaches to the bridges. It had left one division, about four thousand men under General Partouneaux, outside Borisov to mislead the Russians, and this was to follow on under the cover of night.

As most of the army was across by that evening, the gendarmes opened the bridges to the stragglers, cantinières, wounded and civilians. But having settled down by their fires, and seeing that their encampment was defended by Victor’s men, most did not avail themselves of the opportunity, preferring to spend a peaceful night where they were. Some, like the cantinière of the 7th Light Infantry who had gone into labour that evening, had no choice. ‘The entire regiment was deeply moved and did what it could to assist this unfortunate woman who was without food and without shelter under this sky of ice,’ wrote Sergeant Bertrand. ‘Our Colonel [Romme] set the example. Our surgeons, who had none of their ambulance equipment, abandoned in Smolensk for lack of horses, were given shirts, kerchiefs and anything people could come up with. I had noticed not far away an artillery park belonging to the corps of the Marshal Duc de Bellune [Victor]. I ran over to it and, purloining a blanket thrown over the back of one of the horses, I rushed back as fast as I could to bring it to Louise. I had committed a sin, but I knew that God would forgive me on account of my motive. I got there just at the moment when our cantinière was bringing into the world, under an old oak tree, a healthy male child, whom I was to encounter in 1818 as a child soldier in the Legion of the Aube.’22

A remarkable degree of order and even normality reigned over the Grande Armée as it settled down for the night on both sides of the river. A key factor was undoubtedly the presence of the Emperor and the fact that he had visibly taken the initiative, which led everyone to expect great things and kept spirits high. ‘We are still capable of fun and a good laugh,’ noted Jean Marc Bussy, a Swiss voltigeur sitting around a campfire with his comrades on the western bank of the river. One cannot but admire him. ‘When night fell, each soldier took his knapsack for a pillow and the snow as a mattress, with his musket in his hand,’ wrote his comrade Louis Begos of the 2nd Swiss Regiment. ‘An icy wind was blowing hard, and the men pressed up against each other for warmth.’23

All that day Napoleon had anxiously listened for the sound of cannon announcing the approach of the Russians. But there was still no sign that Chichagov had realised his mistake. The note he penned to Marie-Louise that evening shows no trace of anxiety.24

What he might have heard, had it not been over ten kilometres away, was the end of one of Partouneaux’s brigades, which had been holding Borisov. The Partouneaux division, which had only entered Russia recently, had suffered the depressing effects of the conditions in rapid order. The men had been in fine spirits when they had reached Borisov a few days before. At one point they were charged by some Russian cavalry and formed squares. One of the Russian officers, unable to control his wounded mount, had crashed into the middle of the square, where he was pinned to the snow under the thrashing animal. A couple of French soldiers pulled him clear, dusted the snow off his uniform and then went back to their posts in the firing line. The officer bided his time until the French were occupied by another Russian charge and, slipping between them, ran, hopping through the deep snow, to rejoin his own men, at which the entire French square burst into laughter.

But a couple of days later, as they camped out in a windswept spot without fires or food, their mood was very different. ‘Some wept, crying out plaintively to their parents; some went raving mad; some died under our eyes after a horrible agony,’ according to one of them. Having held Borisov as long as was necessary, the division had begun to withdraw on the afternoon of 27 November. But one of its brigades lost its way and walked straight into the midst of Wittgenstein’s army. After a running battle in which it lost half its number, it was forced to surrender. The men were stripped, beaten and marched off into captivity. One of its regiments, the 29th of the Line, was made up largely of men who had only recently been released from prison hulks in England, having been captured in Saint-Domingue in 1801. ‘Luck, one has to admit, seems to have abandoned these poor fellows,’ remarked Boniface de Castellane.25

Chichagov had by now realised that he had been duped. Most of his men were still at Borisov and points further south, but he ordered Czaplic to attack the French forces which had already got across the Berezina, promising to send reinforcements. But his men, who had been force-marched some fifty kilometres south and were now ordered to hurry back, made slow progress through the heavy snow. There was much grumbling and even the threat of mutiny. ‘One of the regiments I had ordered to go and reinforce Czaplic hesitated and then refused outright to move,’ Chichagov recorded. ‘My exhortations having produced no effect, I was obliged to have recourse to the threat of firing on it. I had cannon unlimbered and levelled at it from behind.’ Some of Chichagov’s units did however come up to reinforce Czaplic that night, and more were on the way.26

Before dawn on 28 November, as Oudinot finished gulping down the warming soupe à l’oignon his staff had cooked up at their campfire, the first shots resounded on the western bank of the Berezina as a reinforced Czaplic pushed northward under a strong artillery barrage. Oudinot organised a defence, and led his men out under murderous fire from the Russian guns, but he was hit by a shell splinter – his twenty-second wound. Napoleon, who was on the scene, put Ney in command with orders to hold the Russians back at all costs in order to cover the retreat of the remainder of the Grande Armée, the stragglers and, finally, Victor’s men.

It was a tall order. Czaplic and Chichagov had over 30,000 fresh troops who had not suffered any serious military losses, and all Ney could put up against them were 12 to 14,000 emaciated and half-frozen remnants: all that was left of Oudinot’s 2nd Corps, the Dabrowski division and a few survivors from Poniatowski’s 5th Corps, the Legion of the Vistula, and a handful of other units (his own 3rd Corps had all but ceased to exist, with one regiment numbering forty-two men, another only eleven, and the 25th Württemberg Division’s six regiments of infantry, four of cavalry and divisional artillery park down to a grand total of 150 men). Three-quarters of them were not even French. Almost half were Poles, there were four regiments of Swiss, a few hundred Croats of the 3rd Illyrian Infantry, some Italians, a handful of Dutch Grenadiers and Colonel de Castro’s 3rd Portuguese Regiment. This motley bunch rose to the occasion magnificently.27

The Russians under General Czaplic, a Pole in Russian service, advanced in force through the wooded terrain, but Ney sent in Dabrowski’s Poles, who forced them back to their starting positions. Two more divisions sent by Chichagov then arrived on the scene, Voinov’s and Shcherbatov’s. They launched a massed attack, supported by an artillery bombardment which sent splinters of pine and fir shooting murderously through the ranks of the Poles. Dabrowski was wounded and handed over command to General Zajaczek, who was soon carried off the field himself with a shattered leg, leaving General Kniaziewicz in command, but he too was put out of action. As the Poles fell back in hand-to-hand fighting among the trees, Ney reinforced them with whatever units came to hand.

Although these were numerically weak, they displayed barely believable spirit. The 123rd Dutch Light Infantry regiment, down to eighty men and five officers, cheered as it went into action. At one point a cannonball shattered the trunk of a huge tree heavy with snow, which came crashing down and buried a dozen men of the French 5th Tirailleurs, but they all clambered out from under the snow laughing like children amidst the bursting shells. When, a few moments later, a shell killed their Colonel’s horse, throwing him to the ground, they rushed forward to his aid, but he sprang up and shouted at them: ‘I am still at my post, so let everyone remain at theirs!’28

In order to relieve the pressure on them, Ney sent in General Doumerc with his cuirassiers and three regiments of Polish lancers. They charged the Russians, sowing panic and driving them back. Czaplic was wounded and General Shcherbatov was captured, along with two thousand others and a couple of standards. A countercharge by Russian hussars and dragoons steadied the situation, but the Swiss regiments, which had now taken over the French front line, supported by the Dutch, the Croats and the Portuguese, held their ground.

The battle raged all day, with the Swiss making no fewer than seven bayonet charges when they ran out of cartridges. ‘It was worse than a butchery,’ noted Jean Marc Bussy. ‘There was blood everywhere on the snow, which had been trampled as hard as a beaten earth floor by all the advancing and retreating … One hardly dared to look to right or left, out of fear of seeing that a comrade was no longer there.’ The fighting was so hot that they forgot about the freezing temperatures, and they kept their spirits up with shouts of ‘Vive l’Empereur!’ As death closed in around them in the icy wood, the Swiss broke into the strains of the old mountain lied ‘Unser Leben Gleicht der Reise’.29 The fighting did not stop until eleven o’clock that night, when the Russians, having failed to push the defenders back one step from their morning positions, finally gave up.

It was a magnificent victory for the French, but a bitter one. As they made fires and dragged in their wounded to dress them as best they could, they knew that they would have to leave them behind the following day. The four Swiss regiments had lost a thousand men, and mustered no more than three hundred between them. ‘We hardly dare speak to each other, for fear of hearing of the death of another of our comrades,’ recalled Bussy. Of the eighty-seven voltigeurs in his company who had laughed around their campfires the previous night, just seven were left alive. The 123rd Dutch Light Infantry had ceased to exist. The Dutch Grenadiers were down to eighteen officers and seven other ranks.30

Their heroics were honourably matched by Victor’s men defending the crossings on the other bank. They numbered no more than eight thousand men, mostly Badenese, Hessians, Saxons and Poles, and were facing an army over four times that. But here too morale was unaccountably high. They were attacked at nine o’clock in the morning and held their positions until nine that evening against overwhelming odds.

Wittgenstein’s first attacks were concentrated on the Baden brigade, commanded by the twenty-year-old Prince Wilhelm of Baden, which was holding the right wing of the French defence perimeter. Prince Wilhelm’s men had been greatly cheered when, three days before, they had come across a convoy from Karlsrühe with food and supplies of every sort. The men were able to exchange worn-out uniforms, overcoats and boots for new ones, and to help themselves to food and delicacies. ‘Every officer had received something from home and everyone jumped on the packages destined for them,’ wrote Prince Wilhelm. ‘Thus it was that I saw Colonel Brucker, standing on one of the wagons, open up a large box which I assumed to be full of victuals, and from it he drew a wig and, quick as a flash, he removed the old one he had on his bald head and donned the new one, trying to mould it to his head with his hands.’ Prince Wilhelm himself was in a good mood that morning as his greyhounds had caught a hare, which he had eaten and washed down with wine that had come in the convoy.31 Although they were now attacked by overwhelming forces, he and his men stood firm, at the cost of terrible losses.

Hoping no doubt to break the determination of the defenders, Wittgenstein established a strong battery beyond the left wing of Victor’s line, and began shelling the area behind it. This was by now occupied by a dense mass of thousands of people, horses and vehicles, up to four hundred metres deep, stretching for over a kilometre along the riverbank. Shortly after midday, Russian shells began to rain down on this vast encampment, bringing hideous destruction as they exploded among the mêlée, killing and maiming people and horses, sending splinters of wood and glass from shattered carriages flying through the air. It was the end of the road for many of the civilians. Captain von Kurz watched in horror as a beautiful young woman with a four-year-old daughter had the horse she was riding killed and her thigh shattered by a Russian shell; realising that she could go no further, she untied the blood-soaked garter from her leg and, after kissing her tenderly, strangled her child and, clutching her in her arms, lay down to await death. Seeing her wagon stuck, Baska, the cantinière of the Polish Chevau-Légers, cut her horse free and, taking her small son in her arms, rode into the Berezina on it. She got more than halfway across before the horse began to drown and sank beneath the surface, throwing her and her son into the water, from which only she was able to wade ashore.32

Panic broke out, and a mad rush for the bridges ensued, with people driving their wagons and horses over the corpses of men and beasts, over the wreckage of carriages and abandoned luggage. This merely served to compact the mass pressing around the bridge-ends like a flock of frightened sheep, and now every Russian shell found a target. The massacre continued until Victor managed to mount an attack on the Russian batteries which forced them to pull back out of range.

Although the shelling had stopped, that did not relieve the pressure on the crossings. A mass of people, horses and vehicles converged on the bridges, with those behind pushing forward continuously, so that it was not possible to avoid trampling those who stumbled and fell. ‘Anyone who weakened and fell would never rise again, as he was walked over and crushed. In this dense mass even the horses were so hard-pressed that they fell over, and, like the men, they too could not get up again,’ remembered Sergeant Thirion. ‘By the efforts they made to do so they brought down men who, being pushed from behind, could not avoid the obstacle, and neither men nor horses ever rose again.’33

Lieutenant Carl von Suckow had become separated from his fellow Württembergers and was caught in the crush. ‘I found myself being dragged along, jostled and even borne along at some moments – and I do not exaggerate,’ he wrote. ‘Several times I felt myself being lifted off the ground by the mass of people around me, which gripped me as though I had been caught in a vice. The ground was covered in animals and men, alive and dead … At every moment I could feel myself stumbling on dead bodies; I did not fall, it is true, but that was because I could not. It was only because I was held up on every side by the crowd which pressed in on me. I have never known a more horrible sensation than that I felt as I walked over living beings who tried to hold on to my legs and paralysed my movements as they attempted to raise themselves. I can still remember today what I felt on that day as I placed my foot on a woman who was still alive. I could feel the movements of her body, and I could hear her scream and moan: “Oh! take pity on me!” She was clinging to my legs when, suddenly, as a result of a strong thrust from behind, I was lifted off the ground and wrenched from her embrace.’ As he found himself being forced back and forth near the entrance to the bridge, he experienced ‘the first and only real moment of despair I had felt during the entire campaign’. He finally grabbed the collar of a tall cuirassier who was clearing a path for himself with a mighty stick, and was dragged onto the bridge and over the river.34

As those caught in the throng could not see in front of them, many found that they came to the river not at the head of one of the bridges, but on the bank. Since they were still being pushed from behind by others they were forced into the water, through which they tried to wade over to the bridges and clamber on from the side. The crush on the bridges themselves was just as great, and those walking in the middle were pressed from both sides as those at the sides moved along facing outwards and pushing inwards with their backs in order not to be thrown into the water.

Those who could not stand up for themselves did not have much of a chance, and many who had somehow managed to make it thus far perished here. A Saxon under-officer named Bankenberg, who had had both legs amputated above the knee after Borodino, had been rescued from Kolotskoie by his comrades. He had been tied onto a horse, and survived all the tribulations of the retreat with courage, but they lost sight of him at the Berezina, and he was never seen again.35

In the afternoon Wittgenstein mounted a second assault on Victor’s defences, and the Baden brigade was finally forced to give ground. But Victor sent in the Brigade of Berg, made up of Germans and Belgians, and then his remaining cavalry. This, consisting of Hessian chevau-légers and Badenese hussars as well as French chasseurs, no more than 350 men in all, was led into the charge by Colonel von Laroche with such dash that it routed the Russians. A countercharge by Russian cavalry virtually annihilated the Germans, but the French defences had been saved, and as night fell Victor’s men were occupying the same positions as they had that morning.

Many of those still hoping to cross found themselves blocked by the barricades of abandoned vehicles, dead horses and human corpses which impeded access to the bridges, and as night began to fall and the fighting died down, they too began to settle down for the night, in the hope that crossing might be easier in the morning.

Victor received the order to withdraw, but seeing the numbers of non-combatants still on the eastern bank, he decided to hold it until daybreak, thus giving them a chance to cross. General Eblé and 150 of his pontoneers cleared the bridges of the corpses, carcases and vehicles that had accumulated on them in the afternoon rush. In order to clear the approaches they dragged many of the abandoned vehicles onto the bridges and then pushed them into the water, and unharnessed and led to the west bank as many of the abandoned horses as they could. They had to drag away or push over carriages and wagons that could not be wheeled away, heaving the carcases of horses and human corpses to the side to create a kind of trench between two banks of dead men and beasts.

At nine o’clock that evening Victor began sending some of his units, his supply wagons and his wounded across, and by one o’clock in the morning of 29 November he had only a screen of pickets and a couple of companies of infantry left with him on the east bank. He and Eblé urged the remaining stragglers to cross, warning them that the bridges would be burnt at first light, but most of them were either too tired or too apathetic. ‘We no longer knew how to appreciate danger and we did not even have enough energy to fear it,’ wrote Colonel Griois, who remained by his fireside along with other comrades from Grouchy’s corps. Others were apparently too absorbed by other preoccupations, and the surgeon Raymond Pontier swore that he saw two officers fighting a duel instead of crossing.36

At about five o’clock in the morning, Eblé ordered his men to start setting fire to wagons and carriages still littering the eastern bank in order to wake up the non-combatants, and to shout loudly that the bridges would only be open for a couple of hours. A few availed themselves of this, but at six o’clock, when Victor withdrew his pickets and marched across, the remainder began to realise that their last chance had come. A mass of them swarmed onto the bridges, pushing and shoving to get over. Sergeant Bourgogne, who had come back to see if he could pick up any stragglers from his regiment, watched as a cantinière, holding onto her husband who had their child on his shoulders, was pushed into the icy water, dragging her family with her, and as a wagon with a wounded officer was tipped over, horse and all, to disappear instantly beneath the ice floes.

Eblé had orders from Napoleon to burn the bridges at seven o’clock, as soon as Victor’s last man was across, but he could not bear to leave so many of his countrymen stranded, so he delayed the execution of the order until 8.30. By then Wittgenstein’s men could be seen advancing towards the bridges on the opposite bank, and groups of cossacks were already picking over the booty left behind in the wagons and carriages littering the approaches. As Eblé fired the bridges, some of those still on them tried to struggle through the flames, others threw themselves into the water in order to swim the last stretch, while hundreds of others were pushed into it by the pressure of those behind who did not know the bridges now led nowhere.37

The morning after the French had marched off, Chichagov rode up to the scene of the crossings. He and his entourage would never forget the grim spectacle. ‘The first thing we saw was a woman who had collapsed and was gripped by the ice,’ recalled Captain Martos of the engineers, who was at his side. ‘One of her arms had been hacked off and hung only by a vein, while the other held a baby which had wrapped its arms around its mother’s neck. The woman was still alive and her expressive eyes were fixed on a man who had fallen beside her, and who had already frozen to death. Between them, on the ice, lay their dead child.’38

Lieutenant Louis de Rochechouart, a French officer on Chichagov’s staff, was deeply shaken. ‘There could be nothing sadder, more distressing! One could see heaps of bodies, of dead men, women and even children, of soldiers of every formation, of every nation, frozen, crushed by the fugitives or struck down by Russian grapeshot; abandoned horses, carriages, cannons, caissons, wagons. One would not be able to imagine a more terrifying sight than that of the two broken bridges and the frozen river.’ Peasants and cossacks were rummaging through the wreckage and stripping the corpses. ‘I saw an unfortunate woman sitting on the edge of the bridge, with her legs, which dangled over the side, caught in the ice. She held to her breast a child which had been frozen for twenty-four hours. She begged me to save the child, not realising that she was offering me a corpse! She herself seemed unable to die, despite her sufferings. A cossack rendered her the service of firing a pistol at her ear in order to put an end to this heartbreaking agony!’ Everywhere there were survivors on their last legs, begging to be taken prisoner. ‘“Monsieur, please take me on, I can cook, or I am a valet, or a hairdresser; for the love of God give me a piece of bread and a shred of cloth to cover myself with.”’39

Estimates of the numbers left behind on the eastern bank of the river vary wildly, from Gourgaud’s dismissive assertion that only two thousand stragglers and three guns failed to get across, Chapelle’s estimate of four to five thousand along with three to four thousand horses and six to seven hundred vehicles, to Labaume’s of 20,000 and two hundred guns, which is certainly too high. Chichagov recorded that nine thousand were killed and seven thousand taken prisoner, which seems closer to the mark. Most are now agreed that during the three days the French lost up to 25,000 (including as many as 10,000 non-combatant stragglers) on both banks, of which between a third and a half were killed in action. Russian losses, all inflicted in the fighting, were around 15,000.40

The crossing of the Berezina was, by any standards, a magnificent feat of arms. Napoleon had risen to the occasion and proved himself worthy of his reputation, extricating himself from what Clausewitz called ‘one of the worst situations in which a general ever found himself’. His soldiers had fought like lions. But it was above all a triumph for Napoleonic France, and its ability to create out of the rabble of a score of nations armies which were in every way superior to their opponents, which fought intelligently as well as loyally, and which in this instance did so as though they had been defending their own wives and children. ‘The strength of his intellect, and the military virtues of his army, which not even its calamities could quite subdue, were destined here to show themselves once more in their full lustre,’ as Clausewitz put it.41

* The original plan had been to construct three bridges, but a shortage of materials prevented the third being built.