An investigation of the problem of proportionality under declining capitalist reproduction is of more than theoretical interest. Our reasons for undertaking this investigation have nothing to do with wanting pedantically to complete our analysis of simple and expanded capitalist reproduction by examining "all possible cases." Ever since capitalism entered the stage of collapse, ever since a number of capitalist countries experienced years of declining reproduction (after the outbreak of the imperialist war)—an economic situation in which some of them, such as Great Britain, still find themselves today—ever since it became possible that one or another sector of the world capitalist economy might at any given moment embark upon a rapid economic decline, an analysis of the conditions of declining reproduction and its consequences has taken on tremendous practical interest. Especially in view of the growing ties between our economy and the world economy, such an investigation is also necessary for an understanding of certain specific conditions of our existence, of our economic development. It is only unfortunate that I have to limit the investigation of this problem to the most essential aspects, so as not to stray too far from my basic topic.

The theoretically possible—and most characteristic—cases of declining reproduction are the following: (1) when, with a given and constant rate of nonproductive consumption by capitalist society, there is either (a) a steady reduction of the productively employed working population, (b) a drop in the productivity of labor of the same mass of labor power at the same level of wages, or (c) a simultaneous reduction of productively employed labor power and a drop in the productivity of labor; and (2) when, with a constant— or even temporarily growing—employed working population and a constant or rising level of the productivity of labor, the nonproductive expenditures of capitalist society grow so fast that they not only devour the part of the annual surplus value that is to be accumulated but also eat up each year part of the fixed and circulating capital of production. This will then necessarily lead to a year-to-year decrease in the volume of variable capital and hence to a year-to-year decrease in the surplus value created.

The difference between the first and second cases is that in the first case the surplus value diminishes as a result of the reduction of v, whereas the rate of exploitation remains constant. If nonproductive consumption continues at the same rate, there comes a point when this nonproductive consumption becomes greater than the entire quantity s, and erosion of the country's fixed capital begins. In the second case, nonproductive consumption grows faster than v and the newly created surplus value; the country passes through a period of a falling rate of accumulation, and it finally arrives at the same result as in the first case: that is, erosion of fixed capital begins, circulating capital is contracted, the level of variable capital is reduced, and the additional consumption increasingly exceeds accumulation.1

In both cases the point may be reached when the economy has collapsed so far that the "normal" volume of nonproductive consumption that prevailed at the onset of the collapse will exceed the amount of annual surplus value created under conditions of "normal" exploitation of the given number of workers, and the collapse will automatically continue. At that point it will be absolutely impossible to return to the conditions of expanded capitalist reproduction without a drastic cutback in nonproductive consumption and a drastic increase in the rate of exploitation.

The economies of the belligerent countries of Europe at the outbreak of the world war provide examples of a combination of both these cases: (1) labor power used in production was generally reduced as a result of repeated mobilizations; (2) the productivity of labor dropped, since some of the skilled workers who had been mobilized were replaced by untrained workers, women, and children; (3) the productivity of labor dropped as a result of inferior raw materials and the reduction of capital outlays for reequipping industry, that is, as a result of the deterioration of the instruments of production; and (4) first fixed and then circulating capital were used up without being replaced in natura, including a failure to maintain sufficient supplies of raw materials and the exhaustion of normal stocks.

In the interests of simplifying the investigation, we shall in our analysis examine the equilibrium, in value terms, of reproduction under conditions where nonproductive consumption grows so quickly that it eats up the entire surplus value of society and necessitates a systematic erosion of its fixed and circulating capital. We shall proceed from the following assumptions: ordinary nonproductive consumption remains the same, in absolute figures, as at the onset of the economic decline; the rate of exploitation and the productivity of labor are the same as before; and all the changes that take place in the economy are due to a sharp growth in nonproductive consumption beyond the normal limits of the society in question. This case is not entirely typical of the European economies during the war, since it simplifies the situation; however, it does provide the broad outlines for understanding the processes that occurred in the European economy during the war and created the postwar situation in the West. In Europe we had a reduction of variable capital, but owing not so much to a reduction of capital used in production as to the mobilizations. The results, however, were the same; the reduction of variable capital and surplus value caused by the drop in the quality of labor power and the reduced wages paid for it tended to have the same effect. Fixed and circulating capital was also eroded at an enormous rate as nonproductive expenditures sharply exceeded the amount of surplus value created each year. The characteristic feature of this erosion, however, was that the nonproductive consumption appeared not only as the squandering of created values but also as an increase in the production of values—as well as in the apparatus for their production—exclusively for nonproductive spending; we have in mind here the war industry. It would not be particularly difficult to introduce, in addition to the two standard departments used by Marx, a sector of war industry for the economy of belligerent Europe, that is, a sector for the specific form in which the productive forces of society were primarily used up. However, there is scarcely a need for this if we allow in advance for the fate of the fixed capital of the war industry when we speak of the conditions of postwar reconstruction of the European economy. Or, to put it more precisely, if in addition to the usual nonproductive consumption of society, we recognize that society must cover a new, extraordinary amount of nonproductive consumption resulting from the war, then we have to ask (1) where can this sum be taken from? and (2) in what form will it be spent? If society maintains its usual rate of nonproductive consumption and rate of exploitation, the first source for covering this extraordinary expense will be the part of the surplus value that previously was accumulated and used for expanded reproduction. The second source, if one disregards the depletion of stocks, is to consume the constant capital used in production without replacing it. Specifically, if for each 1 million in value of output in a certain branch of industry the depreciation charges on fixed capital are 300,000 and raw material costs 500,000, then failure to pay the depreciation charges on fixed capital will release all or most of this 300,000 and leave it prey to nonproductive consumption. If in a period of declining reproduction the circulating capital of industry is also reduced, then a certain part of this 500,000 will also be transferred into the fund of nonproductive consumption. Given an actual decline in reproduction, part of the capital that goes to advance the wages fund is also released. This is why, in constructing a scheme for declining reproduction, we can simply subtract the sums that exceed the accumulation fund from the value of the annual product and reduce the volume of constant and variable capital of both departments of the capitalist economy by this amount.

At this point we are left with only the extremely complex question of the interrelations between the total fixed capital of a country and the part of it that is worn out each year. If, for example, of 1,000c that is replaced annually under conditions of simple or expanded reproduction only 900c is replaced under declining reproduction, this does not always mean that a new cycle must begin with a 10 percent reduction in the total fixed capital (capital O actually at work.2 The matter is, in fact, much more complicated. If for a year or two no depreciation allowance (in the economic sense, rather than the bookkeeping sense) is made for a machine that has six working years left, that is, if the machine is not replaced by an appropriate level of machine-building in the country but serves instead for a couple of years past the time when it would normally have been replaced, this means that temporarily a somewhat greater volume of fixed capital can function in production that can be embodied in the numerical schemes for the actual restoration of fixed capital. What we will have is a unique type of loan from society's total stock of fixed capital. None of this, however, is significant in the long term, but only for periods shorter than the average length of service of the country's fixed capital. Hence, despite its practical importance, we can ignore this question altogether in our theoretical analysis of the conditions of declining reproduction and purposely simplify the problem by deducting the entire unrestored part of the functioning capital from the active capital of production. This will be the correct approach for understanding how the process we are studying tends to operate over the long term. But we shall return to this question below, since the whole problem will become clearer once we have set forth a numerical scheme to illustrate declining reproduction.

Now another question arises: What happens to the distribution of labor in society when a certain part of the total sum of previously functioning capital is not replaced each successive year?

If in our example 100c of the 1,000c is not replaced, and of this 100, fixed capital accounts for 70 and circulating capital in its material form (that is, raw materials, fuel, and so on) accounts for 30, this means that the number of workers that were required to restore 70c by producing machines, constructing buildings, and so on are no longer employed in department I. The same is true of the number of workers needed to replace the 30c of raw materials, fuel, and so on.* In other words, a rise in nonproductive consumption to the point that it erodes society's capital means, in the present case, a reduction in the number of productively employed workers and an increase in the nonproductive army of labor. In the case at hand, this can mean an increase in the number of unemployed, whereas during wartime it is expressed primarily in an increase in the number of workers called into active military service, and finally, in an increase in the number of workers engaged in war industry, producing weapons.

This last circumstance must be studied in somewhat greater detail. It might seem strange to put workers in war industry in the same category as the army of the unemployed or as those in active military service, since these workers are employed in production, even though it is, to use Comrade Bukharin's term, "negative expanded reproduction." This is nevertheless a correct procedure. Workers in war industry do produce values, but they are values that are destroyed. They produce neither articles of individual consumption, nor articles of productive consumption, nor the means of production of articles of consumption. Workers in war industry also produce surplus value, but that surplus value has the material form of those same instruments of war, that is, they are values that are directly destroyed. Before its realization, the capitalists' surplus value exists in the in natura form of cannons, machine guns, rifles, artillery shells, equipment for combat engineers, ammunition, and so on. And its realization consists in the exchange of all this for money or bonds of various types and time limits received from the government, that is, for money or titles to income. When means of production are purchased for war industry and consumer goods bought for its workers and capitalists, there is a one-way withdrawal of values from the country's resources: these values are not replaced in their in natura form either by means of production or by means of consumption for other branches of social reproduction and consumption. Under these conditions, the surplus value produced by the workers of war industry plays the following role: the machines, metal, fuel, and workers' means of consumption destined for war industry are not simply destroyed, but they are destroyed after they have been augmented by the value of the surplus labor of the workers. A record of this surplus value is very important for keeping account of military spending, but it is entirely unimportant for analyzing the conditions of proportionality of social reproduction as a whole, because the surplus value of war industry plays no part in that reproduction. All the expenditures for raw materials, for worn-out fixed capital, and for workers' consumption go into the column of society's nonproductive expenditures.

After what has been said, we still must mention what happens to the material values that are taken away from society's capital during declining reproduction, as well as what happens to the surplus value of branches other than war industry. The values that have the in natura form of means of consumption go to maintain armies of various types and into the consumption fund of the workers and capitalists of war industry. The values that have the in natura form of means of production, whether they be machines for the production of arms and ammunition or whether they be metal or fuel, act as constant capital in the reproduction of implements of war and military supplies and, once they have been processed through that stage, are subject to destruction. In those cases where the war industry itself produces means of production whose in natura form enables them to serve in production during normal periods, these means of production figure in the expenditures of society to the extent of their actual wear or consumption.

From the above discussion, the reader can see why, even in a case as familiar as the period of the world war, we do not feel it necessary to supplement the usual two Marxist schemes of social reproduction with a third, a scheme for war industry, in studying the equilibrium conditions of declining reproduction. This type of nonproductive consumption, which takes the form of nonproductive reproduction, may be studied within the schemes for reproduction of society as a whole simply as a direct squandering of means of production and consumption. A study of the war economy of a particular country would be a different matter: there an analysis in value terms would be quite inadequate, and we would have to study the proportionality of the material elements of exchange as well. Moreover, the decline in reproduction in departments I and II would never prove to be anywhere near uniform.

Let us now turn our attention to arithmetical schemes, which should most graphically illustrate the process of declining reproduction as expressed in terms of value.

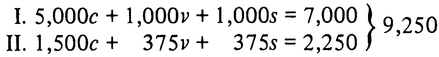

As our initial scheme we shall take the production of a normal prewar year, distributed as follows:

Of this amount—that is, society's gross income—its net income (from the standpoint of society, not of the capitalist class) is equal to v + s of both departments, or 2,750.3 The organic composition of capital—which we assume remains constant throughout the entire period of declining reproduction—is higher in department I (5:1) than in department II (4:1). Likewise we assume that the absolute figure for the consumption of the capitalist class also remains constant throughout, that is, it remains equal to 500 for department I and 375/2, or 187.5, for department II. We make this assumption not only for the sake of simplicity but also because—as experience in Europe during and after the war has shown—the nonproductive expenditures of capitalist countries are only gradually amenable to reduction. Though they may be reduced by cutting the salaries of government employees, they are increased as a result of other factors directly or indirectly connected with the war, such as the growth of the state apparatus and the splitting up of territories formerly part of one large state. Furthermore, we assume a constant rate of exploitation of the working class, taking it equal to 100 percent, as in Marx's schemes. In economic terms this means that in the version of declining reproduction that we shall first examine, production does not decline as a result of a drop in the productivity of labor and a decrease in accumulation for each worker employed in production. The cause of the decline is different: in the present case, it results from the decrease in productively employed labor power (workers being called into active military service or recruited into war industry) and the simultaneous withdrawal from production each year of a certain part of the capital that had functioned in production before the war.

Let us now assume that in the first year 40 percent is withdrawn from the total national income of society—that is, 1,100 of the 2,750 in our initial prewar scheme. Let us assume that this amount is withdrawn proportional to the net income of each department; in other words, 800 is withdrawn from the income of department I and 300 from department II. But each of these sums is greater than the surplus value of the respective departments.4 Therefore, withdrawal of the indicated sum from the national income entails the withdrawal of part of the functioning capital of both departments. Now, of the 1,000 in surplus value of department I, 500 goes to cover the usual expenses of the capitalist class and all the people whom the capitalists support with their consumption fund; and, as we have already stipulated, this figure remains constant for the entire period of declining reproduction. The remaining 500, which earlier (in the period of expanded reproduction) served as the accumulation fund, is now totally devoured by nonproductive consumption as well. This still leaves 800 – 500, or 300, to be covered. This 300 is taken from the capital of department I proportional to the distribution of constant and variable capital in that department. From the standpoint of the distribution of labor in society, the removal of part of the variable capital of I means a corresponding transfer of part of the workers into the army of the nonproductive. Thus, Iv, which was 1,000 in the initial scheme, has now shrunk by 50 to 950, whereas Ic has dropped proportionally from 5,000 to 4,750.

Exactly the same thing occurs in department II except that 300, rather than 800, is withdrawn from its income. This then requires that 300 – 187.5 be withdrawn from the capital of II (that is, 300 minus the surplus value that previously was accumulated but now, during the war, passes into exceptional, nonproductive consumption). Hence, 112.5 is withdrawn from the capital: 22.5 from the variable capital (leaving 352.5 IIv) and 90 from the constant capital (leaving 1,410 IIc).

After all these withdrawals, the distribution of social capital for the first year of declining reproduction will be as follows:

If we compare the amount of variable capital plus the consumption fund of department I with the constant capital of department II, that is, the magnitudes that must be equal to maintain proportionality in the economy, we see that there is a disproportion here. Namely, 950 + 500 = 1,450, which exceeds 1,410 by 40. The cause of this disproportion under the given conditions of a decline in reproduction is quite obvious. Department II has a lower organic composition of capital than department I—hence its constant capital is relatively less than its variable capital, and its net income is relatively greater. Therefore, if a uniform "war tax" is imposed on the incomes of both departments, the withdrawal made from the capital of department II is a heavier burden for II and takes a larger bite out of its constant capital, whereas the "normal" consumption fund of the capitalist class of department I remains at a constant 500 throughout.5 We shall see below that what we have here is not the fortuitous disproportion of a single year but rather a constant process, characteristic of a gradual transition to the proportions of simple reproduction. Consequently, under the conditions of declining reproduction that we have set for ourselves in this example, disproportion lies at the very foundation of the process. What we have here is the direct opposite of the law that we established for expanded reproduction when the organic composition of capital was rising and department II had a lower organic composition of capital (and hence faster accumulation) than department I. In that case, equilibrium was established by transferring capital from II to I, whereas in the present case it can be attained by the reverse operation: by a faster withdrawal of capital from I and a slower withdrawal from II (provided that the total amount to be withdrawn is a fixed quantity).

Let us now see what this whole process that we have just described means for the economy of society, A reduction of Ic by 250 means, first of all, that this 250 in its material form of machines, metal, fuel, raw materials, and so on, is withdrawn from the functioning capital of department I and passes into nonproductive consumption; that is, it is buried in the ground as artillery shells, converted into the constant capital of war industry, consumed as fuel for troop transports, and so on. Second, it means that this 250 will not be reproduced in the economy of society even in the future—a fact that in turn entails the reduction of Iv by 50, or 5 percent. This 5 percent, in the form of money capital advanced for a corresponding 5 percent of v, is now released; taken in its in natura form, on the other hand, it represents means of production that are cast away into the pit of war. Finally, 5 percent of the workers themselves are either called into active military service or recruited to work in war industry. Even if they do not directly produce instruments of war, but merely the means of production for war industry, they have still been cut off, as it were, from the production apparatus of society and cease to exist for it for a certain period.

It goes without saying that in the eyes of the accountant—looking at the depreciation of the fixed capital in the individual enterprises in I, for example—all this may appear quite different. Indeed, as we intimated above, withdrawing 250 from little c of department I does not have to mean reducing the actually functioning fixed capital by that full amount: the reduction may actually be less, because part may be offset from the reserves of C (capital C), that is, from the fixed capital of society as a whole (insofar as we are dealing with fixed capital). Hence, the failure to restore fixed capital can assume the form of a temporary loan from the country's fixed capital assets.

As regards department II, a withdrawal of 90 from II can have the following consequences in economic terms. This 90 has the in natura form of means of consumption (textiles, foodstuffs, and so on). Normally it would pass into department I and exchange for an equal quantity in value of the means of production that II requires—that is, machines, raw materials and fuel. Now, in the form of means of consumption, it falls to the disposal of a belligerent state and is nonproductively consumed at the front. On the other hand, it cannot be exchanged for means of production from I anyway: I has cut back its exchange fund by reducing the number of workers, and hence part of the fund Iv in its natural form of means of production is no longer being reproduced. But here, too, it is possible that functioning capital is not actually reduced by the full 90, even though the entire 90 has already been nonproductively consumed. What may in fact happen is that the part of IIc that consists of raw materials and fuel can no longer be replaced from I, whereas the fixed capital of IIc can still be used for a certain period without being replaced. The fixed capital crisis occurs all the more forcibly later on, that is, it occurs on a scale that far exceeds the amount of uncompensated wear and tear during that one particular year. A reduction of IIv means decreased production of new values in the form of means of consumption, a corresponding failure to replace part of the variable capital, and a corresponding transfer of part of the workers into the army of the nonproductive. However, if it is impossible to reduce production of means of consumption to the extent dictated by the withdrawal of capital from II, then that reduction can be postponed by rearranging capital within II: the total amount of capital withdrawn from II remains the same, but less is withdrawn from IIv. More capital can then be taken from fixed capital reserves to make up the difference. Thus, one can maintain a balanced exchange of I(v + s/x) for He and still minimize the inevitable reduction of the gross production of means of consumption—a prime goal precisely in a war economy.

Contrary to expectations at the outbreak of the war, European capitalism proved to be highly flexible and elastic in overcoming the difficulties that the war presented—precisely because it drew so very heavily from its fixed capital reserves without replacing them. For example, it converted machines, buildings, and so on into means of production and means of consumption to a much greater extent than would have been possible under conditions of normal depreciation. It thereby also released a corresponding mass of labor power to be used at the front or in war industry.6

Let us now take another look at our scheme. At the end of the first year of declining reproduction, the contraction of production (with the same rate of exploitation) yields the following:

The volume of gross production has dropped as compared to the initial scheme, but the drop is considerably less if we compare our 8,765 with the total we would have obtained had we taken the same initial scheme under conditions of expanded reproduction.

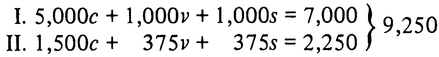

Let us now assume further that before the new year begins, an even greater amount than before is withdrawn from the national income, that is, 50 percent rather than 40 percent is removed from the net income of the initial prewar scheme. In other words, production resumes after 1,375 has been withdrawn (as is known, expenditures increased from year to year in the belligerent countries of Europe). We now make deductions similar to those we made above. However, in order not only to eliminate the disproportion of the first year but also to prevent a disproportion for the second year, we withdraw from department II 105 less than called for by the net income of II. Thus, we end up with the following distribution of capital for the second operating year of declining reproduction:

KI. 4,200c + 840v + 500 consumption fund

KII. 1,348c + 337v + 187.5 consumption fund

With this volume of social capital, we shall obtain at the end of the year:7

If we were to continue in the following years to withdraw the same or a slightly larger quantity of value from the gross income, we would very quickly—within three or four years—find that the variable capital of both departments would be reduced so much that the mass of surplus value created by all the workers of the country, given the same rate of exploitation would drop down to and then below the normal consumption fund of the capitalist class (that is, below 500 in department I and below 187.5 in department II). In that case, even a complete cessation of the exceptional war expenditures and related outlays of social capital and of the reduction of the number of productively employed workers would not prevent the automatic collapse of capitalist society. Unless the nonproductive consumption of the capitalist class were stopped or the rate of exploitation raised, the productive forces would be destroyed without any war—merely on the basis of a discrepancy between "normal" nonproductive consumption and the amount of newly created surplus value. Capitalist society would automatically come to ruin.

The process of declining reproduction that we have outlined here has two important critical points that should be noted: the point of simple reproduction at the prewar level of productive forces and the point of simple reproduction at a considerably lower level. During the course of this whole process, the equilibrium conditions change as follows: (1) the initial scheme begins with the equilibrium of expanded reproduction; (2) nonproductive consumption then begins to grow, reaching a point where there is simple reproduction on the level of the last year of expanded reproduction. In our scheme we began directly with a rate of declining reproduction such that not only was the entire accumulation fund absorbed in the first year, but part of the capital of society was also used up without replacement. But we can return to our initial scheme and reconstruct this first critical point that changes the conditions of equilibrium.

We have in the beginning

I. 5,000c + 1,000v + 1,000s

II. 1,500c + 375v+ 375s

Let us assume that nonproductive consumption, which in a normal prewar year under conditions of expanded reproduction is equal to (1,000/2) + (375/2), or 687.5, now doubles, whether for reasons connected with war expenditures or for other reasons. The entire surplus value of society, 1,375 will then be absorbed by this nonproductive consumption, and accumulation will cease. But in this case not only will expanded reproduction cease, but the distribution of capital between departments I and II will have to change radically. Under simple reproduction I(v + s) must equal IIc. But in our example l,000v + 1,000s is greater than 1,500c. For the economy of society to be held in check at or near the level of simple reproduction for a certain period of time, there must inevitably be a major rearrangement of the productive forces. Given the same volume of capital that we have in our scheme, the cessation of accumulation and a transition to simple reproduction must lead to a reduction of capital used in department I and an increase of capital in department II.

In fact, the entire capital of both departments (that is, 7,875) will now be distributed as follows:8

I. 4,632.6c + 926.4v

II. 1,852.8c + 463,2v

and at the end of the year, under simple reproduction, the product is

I. 4,632.6c + 926.4v + 926.4s

II. 1,852.8c + 463.2v+ 463.2s

The surplus value, now completely consumed by capitalist society, will be 1,389.6 instead of 1,375 owing to the lower composition of capital and faster accumulation in II, because the increment in IIv and accumulation in II more than compensate for the drop in accumulation resulting from the reduction of Iv.

From this example we can draw two conclusions. First, if the growth of nonproductive consumption compels society to pass from expanded to simple reproduction, this changes the equilibrium conditions within the economy as a whole, inevitably reducing the relative share of the sector of the production of the means of production. Second, under expanded reproduction the problem of new markets is very acute. Sometimes this is due to an overaccumulation in the sphere of production of means of consumption, sometimes to the swelling of the production apparatus and overproduction in department I—which in turn result from the periodic changes of fixed capital that stem especially from widespread technological improvements. With the transition to simple reproduction the problem of the market loses its acuteness and assumes an entirely different meaning and significance. For an individual country the question of markets may, of course, appear differently, since reproduction within that country is dependent upon the worldwide division of labor. Or, more concretely, it may need certain imports which in turn requires corresponding exports to foreign markets.

Thus, the transition from expanded to simple reproduction— a transition that occurs because nonproductive consumption grows but the total volume of capital remains the same as in the last year of expanded reproduction—is the first critical point in the regression of capitalist reproduction that we are examining here. Beyond that point, nonproductive consumption grows to the point at which it begins devouring the capital of society. And at this stage, as we have shown, equilibrium conditions cause a faster devouring of capital in department I (assuming that proportionally equal amounts are subtracted from the net income of both departments), as long as the organic composition of capital in department II is lower than in department I and normal nonproductive consumption in I remains unchanged.

If despite its exceptional, temporary character the growth of nonproductive consumption continues long enough to upset the productive forces of society so severely that the newly created surplus value is only capable of making good society's normal nonproductive expenditures, then the economy will approach a new critical point. If this point is passed, not even a complete halt in the exceptional nonproductive consumption can save the productive forces from further ruin. The only salvation lies in a reduction of the normal nonproductive consumption of bourgeois society, or intensified exploitation of the working class, or both.

We have examined one possible version of declining reproduction, where nonproductive consumption grows because of enormous military expenditures, the capital of society is being devoured, and the productively employed labor power is being simultaneously cut back.

Let us now briefly examine how the same situation can result from other causes, taken separately or together.

Let us look at our initial scheme once again.

Since the total variable capital in both departments equals l,375v, the surplus value produced annually is equal to 1,375s. If we assume that all the conditions that entail a cessation of accumulation and a decline of reproduction will be operating, we can obtain a situation of declining reproduction even without the acute and sudden growth of nonproductive, war-related consumption that figured in our previous example.

First, let ordinary nonproductive consumption grow, but no more than 10 percent, let us say, of the "normal." Such a growth may be due, as we see from the example of postwar Europe, to increased expenditures on the army, to a larger number of states and state apparatuses after the war, to increased numbers of disabled workers, to payments of war debts and reparations, and so on. This yields an increase in the consumption fund of the capitalist class from 687.5 to 824, or 136.5.9

Let us further assume that there is a drop in the productivity of labor caused by the irrational use of industry within the new national boundaries, by inferior raw materials and wear and tear on equipment, by inferior quality of labor power and a decline in the intensity of labor, and so on. As a result of this drop in the productivity of labor, annual output falls by 15 percent, or 412.5. If in addition there is a reduction in the productively employed population by 15 percent, that is, in proportions that are not too far from the actual chronic unemployment figures in Europe, then we shall have a situation where society stands on the verge of passing from expanded to simple reproduction or of plunging outright into the first stage of declining reproduction. Finally, we can add to all this the difficulties that individual countries have as a result of the world division of labor, when they require raw materials that cannot be supplied locally—that is, difficulties that arise in reproducing part of the circulating capital, especially in the case of an unfavorable balance of payments vis-à-vis raw-materials-producing countries. We shall then have in certain sectors of the world economy even more conditions that pave the way to simple or even declining reproduction.

This brief theoretical outline of the conditions of declining reproduction and of the new equilibrium conditions of the economic system under this type of reproduction may also be of practical value. It can be used to one degree or another in an analysis of the European economy during and after the war. Moreover, since world capitalism in general is in a state of collapse, certain of its sectors are bound to pass from a retarded process of expanded reproduction to simple and then declining reproduction for causes other than those directly connected with the consequences of the war. In all these cases, the theory of declining reproduction can serve as an auxiliary tool for studying the concrete economy of particular countries. It can also aid in gaining a deeper understanding of the situation when one sector of the world economy is experiencing expanded reproduction at the same time that others are either regressing or standing still in their economic development. In particular, it is only through a theoretical analysis of expanded reproduction with a steadily decelerating rate of accumulation and an analysis of declining reproduction in the different sectors of world capitalism and in particular periods that one can understand the nature of current industrial crises.

Let us now try to apply the results of our theoretical analysis to understand some of the basic processes that we have observed in the economy of Europe during and after the war.

First of all, there was a reduction in productively employed labor power in all the belligerent countries, owing to the mass mobilizations of the proletariat for the front and for service in war industry. This development was accompanied by a drop in the productivity of labor resulting from the use of women, youths, and insufficiently skilled workers to replace those who had been called up. This in turn led to a general reduction of variable capital and to a decrease in the total mass of surplus value created in the countries that were at war.

In all the belligerent countries an enormous proportion of the gross income was wasted—far in excess of the amount of surplus value. This inevitably led to the depletion of normal production reserves and to the consumption of fixed—and, to some extent, circulating—capital without replacement. Essentially, any one of these causes taken by itself would have been capable of causing declining reproduction. A reduction of productively employed labor power can at a certain point put part of the social capital out of operation and lead to the stage of declining reproduction. Conversely, a rapid erosion of fixed capital through its conversion into means of consumption for the army, into implements of war, or into the means of production for war industry can, at a certain point in this process, make part of the labor power idle (although generally speaking this result can be greatly delayed and restricted by using fixed capital reserves to the limit). During the war, both these processes occurred simultaneously. On the one hand, workers were routinely pulled from production even in cases where the existing volume of capital would have permitted their use in the production process. And simultaneously with the reduction in the number of productively employed, the fixed and circulating capital of the belligerent countries was also being eroded.

As regards the volume of production of coal, pig iron, and steel, one must at the same time bear in mind the rate of consumption of these means of production by war industry. Here, production was to a considerable degree merely the first stage of nonproductive consumption. The production of coal, pig iron, iron, etc. directly for war needs might rightly be excluded from the overall production of a country as a form of nonproductive consumption, were it not for the fact that a number of other branches of production were to some extent in the same situation and that at the end of the war the entire production apparatus of these branches was automatically included in the production apparatus of the peacetime economy.

Our schemes of declining reproduction based on a sharp rise in nonproductive consumption give a general idea of the actual process of the destruction of productive forces that we saw in the belligerent countries of Europe. However, this picture is too general and does not capture a number of the specific features of the European war economy. Here we are faced with a problem that always arises in the transition from a general theoretical analysis of reproduction to a study of reproduction in a concrete country or group of countries during a particular historical period. A theoretical analysis of equilibrium in value terms only provides the groundwork for such a study, whereas now we must study equilibrium from the standpoint of the material composition of reproduction, the balance of payments with other countries, monetary relations, debts and credits, and so on.

In particular, our scheme—even if it accurately depicted the year-to-year movement of gross production —would require the study of a number of other important processes: (1) the rate at which fixed capital reserves were used; (2) changes in the conditions of the supply of raw materials to the belligerent countries, which included not only interruptions in their supply and sharp rises in their prices but also the total stoppage in the supply of certain types of raw materials and a transition to processing related or imitation products (a circumstance that, of course, inevitably altered the distribution of productive forces within the country as compared to the prewar situation); (3) a reduction of exports or an almost total cessation of exports for certain countries, which, when war loans and commercial loans were being contracted abroad, resulted in a one-way flow of values into the country from the outside, at the expense of the nation's future income. All these processes taken together strikingly altered the equilibrium conditions that had existed before the war. They created a special economic system that is almost completely unamenable to study on the basis of the law of value, insofar as the action of this economic regulator was itself so extremely distorted by the intensification of state capitalist tendencies and the profound disorganization of the world market.

But let us assume that we have the ideal investigation of the European economy during the world war, where a value analysis—within the limits of its applicability—is accompanied by an analysis of the material composition of exchange and by all the adjustments that arise from the existence of state-capitalist tendencies. Let us assume that the investigation provides us with an exhaustive description of the entire production apparatus of European capitalism as it emerged from the war; it establishes the link between European and world capitalism with respect to markets and the supply of raw materials and to new liabilities resulting from war debts, reparations, and so on. The question arises, Can we study the European economy from 1919 onward as an economy of expanded capitalist reproduction? Let us pose the question more concretely. If we take the total volume of European production in 1919 and compare it with the year in the past that most closely resembled 1919 in terms of gross production, will we find a process of reproduction that is at all similar to the expanded reproduction of, say, 1890 or 1900?

The answer to this question can only be negative. The European economy from 1919 onward, with its unstable equilibrium, its convulsions provoked by monetary breakdown, the lack of markets, and interruptions in the supply of raw materials, the gaping disproportion between heavy and light industry, the sharp rise in nonproductive consumption as compared to before the war, and so on, in no sense lends itself to study on the basis of the equilibrium conditions of capitalist expanded reproduction. Even the instances of reconstruction that we can see are by no means expanded reproduction of the normal type. In other cases, what we have is simple reproduction on the basis of decreased production of surplus value and a tremendous rise in nonproductive consumption, with intermittent dips toward declining reproduction. When the reconstruction process seems to prevail and the curve of gross production begins to attain its prewar level—even surpassing it in certain countries such as France, Italy and Belgium—the successes attained prove to be highly tenuous, caused as they are by the increased exploitation of labor power and the ruin of the petite bourgeoisie, and they are called into question if and when the currency is stabilized.

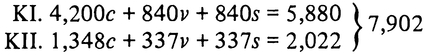

We shall look first of all at the reconstruction process. Equilibrium of the reconstruction process is quite different from equilibrium of expanded reproduction for the following reason. Owing to the enormous development of war industry, the production apparatus of heavy industry in Europe, mainly metallurgy and machine building, had swollen beyond proportion. When reconstruction began, heavy and light industry had to develop under different conditions, from the standpoint of the equilibrium of the economy as a whole. Let us illustrate this situation with an arbitrary scheme. Let us assume that, instead of the initial scheme we used above, production in the capitalist countries of Europe during the first stage of reconstruction is characterized by the following figures, leaving the capitalist consumption fund at its prewar level:

I. 3,000c + 600v + 500 consumption fund

II. 1,100c + 275v + 187.5 consumption fund

It is already apparent from this scheme that reducing v while keeping the consumed portion of s at its prewar levels brings the entire economy of the society down close to simple reproduction and that this in turn increases the relative weight of department II as a whole. Further, if reconstruction is initiated, department I, which now accumulates only 100 of its surplus value instead of the prewar total of 500, is nevertheless able to expand its reproduction to a much greater extent, because it has greater reserves of fixed capital. If we had here the usual process of expanded reproduction and if each department were to expand solely on the basis of its own accumulation fund, then given the fact that expansion required the creation of new constant capital, the 100 in new capital of department I would be distributed between c and v in the proportions of 5:1, and we would have a total of 3,083.6c + 616.4v for the new year—that is, a very small increase of v. But in our case, if most of the additional c is drawn from fixed capital reserves, that is, if inactive blast furnaces, the idle equipment of machine-building factories, and so on are set into motion, then the 100 in new capital now goes to increase the part of c that consists of circulating capital, and to a much greater degree to increase v. If 80 out of 100 goes to v, then we shall have a slight disproportion with IIc, even in this year, and an even greater disproportion the year after. In light industry, on the other hand, fixed capital reserves shrank during the war, and the part of the surplus value that previously went to increase IIv must now be siphoned off and used to plug up the leaks in IIc caused by the war, since no other capital is available in money form. But this is bound to widen the disproportion between departments I and II even further.10

The unfavorable position of light industry is further aggravated by the fact that it must buy part of its raw materials outside Europe (if we are speaking of capitalist Europe as a whole) or abroad (if we are speaking about one particular European capitalist country). As a result, even if the expansion of production in I fully absorbed that part of the additional product of department II that goes to cover the additional IIc, this would by no means solve the question of reproduction for department II. Department II does not merely have to sell; it has to sell so that it acquires the currency of countries that can supply light industry with raw materials. If heavy industry sells in the same countries, the problem is solved at both ends at the same time. Conversely, when light industry itself encounters difficulties in realizing its products abroad at the same time that heavy industry also fails to find sufficient foreign markets, then the internal exchange between departments I and II—guaranteed by definite proportions between IIc and I(v + s/x)—cannot fully take place either. Even if the magnitudes of exchange balance out in terms of value, which is possible when the links between both departments and the world economy are normal, the exchange of values will be hampered by a new factor: a lack of correspondence in the material elements of exchange. As a result of all this, the situation arises in which light industry cannot replace its c proportional to what it might do under the given conditions (with the given I[v + s/x]) of accumulation—that is, it cannot sell consumer goods in I and abroad for an amount equal to the increment of c. Department I then has overproduction for two reasons. First, since its reserve fixed capital has entered into the production process, it already has overproduction because the exchange fund I(v + s/x) exceeds IIc. But in addition, it cannot sell enough means of production in department II even to ensure the necessary growth of IIc, since the replacement of IIc is associated with a definite material composition of means of production, part of which under any conditions must be purchased outside Europe (cotton, rubber, wool, and so on).11

Herein lies the origin of the chronic crisis of the reconstruction process in Europe that has characterized its economic life ever since the end of the war. This crisis of heavy industry—which also hindered the development of light industry, owing to the dynamic links between both departments of social production—was, among other things, expressed in value terms in the constant, higher price index on products of light industry. It is enough just to look at the prices of textiles: their relative growth cannot be explained solely by the rise in raw material prices. As a result, the European economy for seven years now has represented a whole tangle of glaring contradictions. Despite the enormous exhaustion of the fixed capital of light industry during the war, machine-building remains, with the temporary exception of France and Belgium, in a state of permanent crisis. Despite the drop in per capita consumption of the products of light industry, the latter continues a very slow and painful growth. Chronic unemployment has driven several million workers out of production. Exports are expanding only in countries with depreciating currencies, whereas in Great Britain, a country that has gone over to a provisional gold standard, foreign trade is falling from year to year. All this is occurring while the equipment of heavy industry is running at slightly more than half capacity.

It is interesting at the same time to observe the specific forms taken by the reconstruction process in countries that went through a period where their currency was depreciating. In general, the depreciation of currencies in Europe had its origin in the war. But once the currency has started to depreciate, the reconstruction process follows its own peculiar paths and itself becomes one of the conditions that perpetuates the state of monetary chaos.

What distinguishes reproduction during inflation from reproduction when the currency is stable?

The principal difference lies in the fact that in the former case we do not have reproduction in the strict sense; rather, the country's labor power and the fixed capital of production are sold off below their value. 12 We can best see what happens here if we apply inflationary conditions to the scheme of the reconstruction process in Europe that we have just examined. If exchange takes place on the basis of value, then both departments together will have the following gross production to be realized:

4,100c + 875v + 875s = 5,850

Now, if we assume that the entire gross product is sold not at its value but at 10 percent below its value, then the total production will bring in only 5,265 instead of 5,850. If the deficit is distributed equally over c, v, and s, this will mean 410 of the constant capital will not be replaced, and the wages fund and surplus value will be cut by 87.5 each. If the surplus value does not suffer but 410 of the constant capital is not replaced, real wages will have to fall by 20 percent, rather than 10 percent, to produce the same result. On the other hand, if under inflationary conditions there is not a decline in reproduction but rather a process of reconstruction, the 410 of the constant capital that is eroded will affect only the fixed capital, and not the part consisting of circulating capital (fuel, raw materials, and so on). We can see from the example of Germany that during an inflation a country's labor power is sold off at bargain prices that are much lower than 20 percent below its value. In 1919 the real wages of skilled workers in Germany were 75.4 as compared to a prewar index of 100. By 1922-23 they had sunk to 62.2. In other words, in the years when inflation was at its peak, that is, in 1922 and 1923, the wages fund had dropped 37.8 percent from its prewar level. During that time, fixed capital was also being used up without replacement in a number of branches (at the same time that it was being accumulated in others).*13 In Italy, on the other hand, wages fell only slightly more than 10 percent by 1925. In France, the drop by that same year was even less, but here one has to keep in mind the growth of relative surplus value brought about by the extensive reequipping of French industry, which in turn makes a comparison with the prewar level quite incorrect. This applies to some extent to Italy as well.

Now let us pose the question, What was and is the economic significance of selling labor power and fixed capital below their value in an inflationary period?

If we take the part of reproduction that is limited to the exchange of values within the country, then here the same branches that lose as sellers gain as buyers, and only the workers lose in all cases. The balance of losses and gains may vary widely from one particular branch of production to another, but from the standpoint of the national economy as a whole, an inflationary decline in prices14 leads only to a general fall in the gold index of domestic, as compared to world, prices (at the same time, of course, that prices in paper money are rising). In the part of the economy that comes into contact with the world market, on the other hand, a leak is formed through which a mass of commodities flows out onto the world market below the value of its production (taking the cost of v in terms of the prewar index) and below world prices, and hence the products of national production are bargained away at a loss. However, after America had captured Europe's world markets and industrialization of the colonies had intensified, this selling off at bargain prices provided the only serious means (not counting commercial loans) for Europe to force its way back onto the markets it had lost. In particular, it was the only way Europe had to increase trade with America and to in general acquire the necessary foreign exchange reserves and begin expanded reproduction of the part of circulating capital consisting of foreign raw materials. As we have seen above, Europe's heavy industry has a hypertrophied production apparatus. When the expansion of production encounters difficulties, first of all in increasing circulating capital, and above all in increasing the part of it that consists in natura of foreign raw materials, the sale of excess fixed capital—materialized into commodities—at prices considerably lower than its cost (not to mention the bargaining away of labor power, which never grieves capital) represents a patently favorable operation under the given conditions, since this is the only way that circulating capital can be expanded. Such was the significance of inflation for the reconstruction process in Germany, France, Belgium, and Italy.

There is still another side to this whole process. Selling off fixed capital below cost is highly advantageous for capitalism wherever this capital is in any case becoming obsolete and where selling it, along with labor power, at bargain prices enables the capitalists to renew their fixed capital with minimal losses, Without a doubt, this was a partial cause of the inflationary bargain sale in Germany, where low wages permitted considerable work to be done in reconstructing the instruments of production and adapting them to modern technological requirements. This process played an even greater role in France, where the postwar inflation saw a rapid reequipping of French industry and selling off the old fixed capital accomplished two goals simultaneously: France could reenter the world economy and obtain resources for buying raw materials, and she could sell cheaply the equipment that would have had to be scrapped in any case.

From this brief excursion into the sphere of the European economy we see that not only during the war (which is quite obvious) but during the entire postwar period it is impossible to study the economic equilibrium of Europe from the angle of ordinary expanded reproduction and on the basis of the regularities of an economy of that type. The reconstruction process here has its own laws of unstable equilibrium, which are most clearly evident in the inflationary period and which continue to find their expression in the disproportion between heavy and light industry and in the impossibility of Europe once again finding a place on the world market commensurate with its level of industrialization.

One of the most characteristic features of the postwar European economy is chronic unemployment, which represents the result not of an ordinary protracted capitalist crisis but of a crisis of European capitalism as a whole. Great Britain, which was the first country to prove itself incapable of reassuming its prewar position in the world division of labor, has already experienced seven years in which about 1.5 million of its workers have been permanently cast into the ranks of the excess population. After the inflationary speculative boom in German industry, the same process began there as well. Now that the currency is stabilized and the limits of Germany's share of the world market established, unemployment hovers around 2 million. We shall see exactly the same process in France once the franc has stabilized, that is, after France has been allotted its "normal" share of the world market. The process of casting several million European workers—apparently permanently—into the army of the nonproductive is being intensified even more as a result of the rationalization of production that is currently taking place, primarily in Germany. This rationalization, in contrast to what happened under developing capitalism, rarely pushes a country beyond the limits of its fixed share of the world market and leads first and foremost to a rise in unemployment, as well as to a combination of American methods of exploiting workers with European wages. In contrast to the preceding period of capitalist history, when technological progress and the reduction in the cost of production and prices were accompanied by a growth in the number of workers being drawn into production, the present rationalization has meant a reduction in the number of employed workers, and without any drop in prices.15 An increasingly large sector of the working class of Europe is permanently put out of the running. It is as though Marx foresaw the theoretical possibility of such a dead end for capitalism when he wrote in volume III of Capital.

A development of productive forces which would diminish the absolute number of laborers, i.e., enable the entire nation to accomplish its total production in a shorter time span, would cause a revolution, because it would put the bulk of the population out of the running. This is another manifestation of the specific barrier of capitalist production, showing also that capitalist production is by no means an absolute form for the development of the productive forces and for the creation of wealth, but rather that at a certain point it comes into collision with this development.16

The European working population is clearly put out of the running, precisely because the European sector of the world economy has come up against "the specific barrier of capitalist production" in general.

The second problem facing European capitalism is to reconquer the markets it lost during the period of declining reproduction and which still elude the grasp of countries such as Great Britain, which have already set one foot firmly on the foundation of an economy experiencing declining reproduction. But this task is very difficult for old Europe to accomplish: its enormous nonproductive consumption and relatively modest resources for accumulation are insufficient for the expensive reconstruction of the entire economy that is needed to compete successfully on the world market.

In conclusion, it should be pointed out that for the era of declining reproduction or for an economy wavering around the level of simple reproduction, the fascist type of state is in many countries the most appropriate order for preventing further decline and trying to initiate expanded reproduction at the expense of the working class. In its socioeconomic base, fascism is a new discipline of labor in addition to the existing forces—the scorpions of hunger and the buying and selling of labor power on the basis of the law of value—that drive the working class to the capitalist factory and place it within the definite framework of bourgeois exploitation.

We cannot go into this topic at length in this connection. We are also compelled to forego an answer to the question of what must happen within the sphere of the capitalist economy in the period when the capitalist form has exhausted itself from the standpoint of the development of the productive forces but a historically higher form has not arrived to replace it. An investigation of this sort would already mean moving from economics to sociology and politics—fields that are not included in our present task.

*If it is a question of the economy of an individual country, then things are more complex. Specifically, failure to replace 30 in circulating capital in its in natura form may in some cases mean a reduction of imports, or it may give rise to a reduction of imports because of a drop in exports.

*The following method may be used to calculate whether Germany was using up or accumulating fixed capital during the inflationary period as a whole. Take the gross product measured in world-market prices in gold. Subtract from that figure the gross product measured in domestic prices in gold. Take the share of the gross product that is spent on wages and calculate the amount of underpayment to the wages fund. Calculate the size of personal domestic consumption and export. If the underpayment of wages is higher, then this means that the constant capital grew by the difference between the two figures. If the underpayment of wages is lower, then an amount of constant capital equal to the difference was used up without replacement.

1 The way in which Preobrazhensky has used the term "circulating capital" here implies that it refers only to various types of means of production, a usage inconsistent both with Marx and with Preobrazhensky's other writings. For Marx what distinguishes fixed from circulating capital are not the physical characteristics of the commodities involved, but the way in which their value is transferred to the value of the annual product. Fixed capital is that part of the productive capital whose value remains to a greater or lesser degree embodied, or fixed, in particular means of production outside the value of the annual product. Its value is transferred to that of the product only gradually, over more than one production period. Circulating capital is capital whose value is transferred completely to that of the product in the course of a single production period, so that its entire value circulates as part of that of the commodity-product in whose production it participates. Marx's reason for defining fixed and circulating capital in this way is that they are fixed or circulating capital only insofar as they function in production as capital, that is, as a value relation. The distinction is not one of physical properties. On the basis of this definition Marx divided constant capital into two components: a fixed component, such as plant, machinery, some fertilizers or seed, and any means of production that retain part of their value by virtue of their ability to function beyond only one production period, and a circulating component, such as raw materials, fuels, and intermediary products, whose value is completely imparted within one production period to the commodities they go to produce. On the basis of this distinction Marx further divided circulating capital itself into two parts: a constant capital portion, consisting of means of production, which function as circulating capital, and the variable capital portion, since variable capital is a capital value advanced in the course of production whose value is transferred wholly to that of the commodities created by the workers. Thus, the differentiation between fixed and circulating capital is not between different kinds of means of production, nor is it between means of production and means of subsistence. It is also worth noting that the distinction between fixed and circulating capital is one entirely within productive capital, a point that Marx considered it especially necessary to stress given the frequently encountered confusion (in Adam Smith, for example) of circulation capital, or money capital and commodity capital (which are the functional forms that industrial capital assumes in its path of circulation), with circulating capital (capital that is distinguished by the manner in which it transfers its value to the value of the product, something that can only be done in production, where capital has the functional form of productive capital). In Preobrazhensky's other writings, especially in Zakat kapitalizma , where the functional distinctions between fixed and circulating constant capital form a major topic of discussion, his use of terminology is more precise, and when talking of circulating capital he referred to either its constant or variable component, as appropriate. For Marx's treatment of fixed and circulating capital see Capital, vol. II, English edition, chaps. VIII, X, and XI.

2 Preobrazhensky has here introduced the notation of capital C to designate the total stock of fixed capital in society, as opposed to little c, the symbol for the constant capital component of the value of the annual product. Little c represents only the value that passes into that of the product, rather than the total value of the means of production engaged in production. Thus, it includes the value of the entire circulating portion of constant capital plus the value equivalent of the fixed capital depreciation for that year. Using Preobrazhensky's symbols, C will most certainly be a good deal larger than c, since only a fraction of the value of the fixed capital used in production actually is lost in wear and tear in the course of a year, and it is only this fraction that shows up in c. We should not confuse Preobrazhensky's notation with that of Marx in vol. III of Capital, where Marx used C to represent the total capital used in production, that is, C = c + v.

3 What Preobrazhensky here calls the net income of society is the newly created value of a given year. The aggregate value of society's commodity-product breaks down into c, v, and s. Of these, c, the constant capital component, is not value newly created in that year, but old value, created in some past production period and merely transferred to the value of current production. The newly created value is that which is added by the laborers, which itself breaks down into two parts: one covering the value of the means of subsistence needed to restore the laborer's ability to work in the next period (variable capital v), and the other over and above this magnitude, or surplus value. In other words, it is not just s that represents newly added value, or net income. Marx discusses this problem in some detail in Capital, vol. II, English edition, pp. 433-37.

4 This is obviously not the case. The sums withdrawn from the income of each department are greater than s/2, that is, what is available out of s for accumulation after allowing for what Preobrazhensky calls here "normal" capitalist consumption.

5 Actually there are two phenomena at work here. Department II must cut the level of IIc, leaving Is/x unchanged, giving rise to a relative overproduction in department I. This is responsible for the disproportion Preobrazhensky has just described. In addition to that, however, we have the fact that II's organic composition of capital is lower than that in department I. This in turn means that IIv will fall faster than Iv if the demands of this exceptional nonproductive consumption continue. But the faster fall of IIv means also a more rapid fall in IIc. Thus II's surplus value can sustain relatively less of the burden of nonproductive consumption, which can only mean that the rest must necessarily come out of II's capital, including IIc, which will decline faster than the consumption fund of department I and deepen the tendency to overproduction in I.

6 We should be clear that when Preobrazhensky is talking about "loans" of fixed capital or taking from fixed capital reserves he is not talking about the actual physical transfer of machines from one department to another (although this may occasionally take place) or their physical conversion to other uses. In the example he gives above, dealing with department I, that department will sell its annual product for a given monetary sum. Of this a certain portion would normally have gone to replace used-up fixed capital. If instead those machines that would have been scrapped are kept in operation, this money can be put to other uses. In the case of nonproductive expenditures, department I will sell an equivalent of this product—which exists physically as means of production—to war industries or to other branches of the economy whose output does not figure in the future reproduction of society but is squandered as nonproductive consumption. Even if it is able to retain the money received from these sales rather than losing it in various forms of taxes, department I could not apply these funds to the purchase of replacement fixed capital, since the machines, buildings, and so on that would have been devoted to this purpose have now been sold to the military and are no longer available for sale either within department I or to department II. Thus, this much fixed capital will not be restored, and production will fall proportionately. What Preobrazhensky is here arguing is that under normal circumstances the loss of this fixed capital will entail further reductions of production, since machines no longer functioning in production are not able to work up raw materials and do not require any workers for their operation. As a result, a corresponding amount of circulating constant capital will not be purchased and a corresponding number of workers will be laid off. They, too, will enter the production process of war industry, along with the "transferred" fixed capital. This is why in his previous numerical examples Preobrazhensky assumed that a cut in department I's capital owing to increased social expenditure on nonproductive consumption would be shared proportionally by fixed and circulation constant capital and by variable capital. However, as he explains here, this is not obligatory.

In his scheme on p. 142, department I cut its constant capital by 250 and its variable capital by 50. This left Ic at 4,750. Suppose that one-quarter of this amount (1,187.5) represents means of production intended to replace worn-out fixed capital, and three-quarters (3,562.5) is to restore used-up circulating constant capital. Suppose further that the cut in Ic breaks down into this same proportion of used-up fixed to used-up circulating constant capital, that is, 62.5 and 187.5, respectively. If out of the 1,187.5 in machines, buildings, and so on that were to be scrapped and replaced, department I keeps 237.5 of them in operation, it could, at least hypothetically, sell 50 of them to department II in exchange for means of subsistence and thereby make up the cut in its variable capital (assuming it could find replacement workers for those called into war industry or to the front). It could use the other 187.5 to restore the used-up circulating constant capital that would otherwise have gone unreplaced. The problem here is that these means of production would exist in the wrong physical form, as fixed capital, whereas department I would need raw materials, fuel, processed steel, and so on. Department I could perhaps escape from this bottleneck if it could export this 187.5 in machines (unlikely in time of war) to raw-materials-producing countries in exchange for means of production of the correct material form. In reality, as the experience of the major imperialist countries during both world wars shows (especially that of Germany prior to and during World War II), it would more likely be able to keep some of its expiring fixed capital functioning while relying on reserves or alternative sources of raw materials, on the one hand, and drawing into production members of the population previously excluded from it, on the other. But it would not be able to avoid a situation of declining reproduction altogether; and the erosion of its fixed capital in this way would strike the economy particularly hard later on, when masses of fixed capital would need renewal more or less simultaneously. This, of course, is precisely what occurred in the Soviet Union following World War I and the Civil War, and we can safely presume that Preobrazhensky's example here was chosen to highlight just this fact.

The situation with department II would be similar, but with fewer problems from the point of view of the physical makeup of II's product and its needs for means of production. Department II's product exists physically as means of consumption. If its capital is cut by 112.5, this means that this much in means of consumption that it would have sold either to department I in exchange for means of production (90) or to its own laborers as means of subsistence (22.5) is no longer available for these purposes. This leaves it with 1,410 in means of consumption that, if sold, will go to restore II's constant capital. Suppose that II's constant capital also divides up into one-quarter (or 352.5) replacement fixed capital and three-quarters (or 1,057.5) replacement circulating constant capital. If department II can keep 90 of this 352.5 expiring fixed capital in service, it either does not have to sell this equivalent in means of consumption, or it can use the money it receives from such sales for purposes other than buying fixed capital. It could, for example, take 22.5 of these means of production and use them within the department to restore the loss of means of subsistence that formed part of IIv (as with department I, this presumes that II can either find new workers or increase the productivity of those still employed). This would leave it with 1,387.5 in means of consumption that it could sell to department I, out of which it could replace 262.5 fixed capital and 1,125 constant circulating capital—exactly what this portion of IIc was before declining reproduction set in.

We should note one result of this that Preobrazhensky does not mention. If either department I or department II, or both of them together, relies on reserves of fixed capital to mitigate the effects of declining reproduction, this will worsen the disproportion that already exists between the two departments—that is, it will exacerbate the relative overproduction in department I. From department I's side, using its fixed capital reserves will allow it to increase its variable capital and hence its demand for means of subsistence from department II. If department II also uses its fixed capital reserves, it will lower its demand for means of production from I, at least to the extent that it shifts part of its product to maintaining IIv at or near its old level.

7 Preobrazhensky's calculations for department II in both of these schemes are incorrect. The relative shares of departments I and II in the total income of society are about 73 percent and 27 percent, respectively. Thus, of the 1,375 to be withdrawn from society's net income, 1,004 will come from I and 371 from II. However, we have the further condition that 105 of department II's burden is to be transferred to department I. Department I must, then, absorb a fall of 1,109. It can cover 450 of this out of the accumulated portion of its surplus value, since this is what is left after we deduct the 500 in capitalists' consumption from the 950 Ls. This leaves 659 to come out of I's capital: 549.2 out of Ic and 109.8 out of Iv. Rounding off these figures to 550 for Ic and 110 for Iv (which is what Preobrazhensky did) we have

I. 4,200c + 840v + 500 consumption fund

In working out the figures for department II, however, Preobrazhensky has made an error. II must lose 371 – 105, or 266. The accumulated part of II's surplus value is 352.5 – 187.5 capitalists' consumption fund = 165, and II can use this to cover 165 of its nonproductive consumption burden. This leaves 101 to come out of II's capital: 80.8 out of IIc and 20.2 out of IIv.

Rounding off these figures to 81 for IIc and 20 for IIv, we have

II. 1,329c + 332.5v + 187.5 consumption fund