In the present article we will apply everything we said earlier about reproduction under concrete capitalism to an analysis of equilibrium in the present-day Soviet economy. But before we move directly to the situation today, let us say a few words about the period of "War Communism." We in the Soviet Union often underestimate the legacy that the New Economic Policy (NEP) received from War Communism in the sphere of interrelations between the state and private sectors of the economy. Thus, it would not be out of place to recall the true magnitude of the changes that were introduced into the interrelations between the private and state sectors by the transition to NEP.

The most characteristic feature of the period of War Communism in the sphere of interrelations between the state and private sectors of the economy was, if we may put it thus, the economically separate existence of petty production (primarily peasant production) on the one hand and the state economy on the other. No regular market exchange existed between these two sectors, although generally speaking an illegal and semilegal market did continue to exist throughout War Communism. The exchange that occurred in the form of requisitions on the one hand and deliveries of goods from urban production to the countryside through the People's Commissariat of Supply on the other was of a highly specific nature. The specific features of the interrelations between city and country, to the extent that they were regulated by the state, derived from the general political and economic conditions of War Communism. The principal goal of all production and distribution at that time (a goal that was imposed upon rural petty production from the outside) was not expanded reproduction within the state and private sectors. Rather, the aim was to produce the maximum amount of consumer goods for the army, the urban proletariat, and the rural poor and to produce arms for defense, without any concern for depreciation. Planned distribution of existing stocks played an equally important role in the economy. This distribution, too, was subordinate to the needs of defense rather than to the tasks of expanded reproduction. This was the economy of a beleaguered city that was pursuing the goal of holding out as long as possible to win a war, not the goal of normal reproduction in the economy. Disregarding the type of production relations, our economy under War Communism was one of declining reproduction: it thus resembled the declining capitalist production in Europe during and after the world war, which we discussed above. But in our case—speaking now of the state sector—this was declining reproduction in a socialist economy, and herein lies the uniqueness of this stage of our economic history.

Now, is it possible to illustrate the exchange within this economy—an economy marked by declining reproduction and a widening gap between its state and private sectors—by the same arithmetical schemes that we used in analyzing capitalist and petit bourgeois reproduction?

In principle, such an illustration is impossible. We must remember that what we want to illustrate here is by no means a process of reproduction of a commodity capitalist society where all operations are subject to the law of value. Rather, we are dealing with exchange based on other law-governed regularities, primarily the needs of defense, with total disregard for any sort of equivalency whatsoever, whether in the exchange of the total sum of articles of consumption of rural origin against urban products or in the internal distribution of the goods that the peasantry received according to the plans of the People's Commissariat of Supply. Marx's schemes are not suitable for illustrating reproduction in an economy of this type: Marx used his arithmetical examples to illustrate equilibrium conditions of exchange of values under pure capitalist reproduction. His schemes are no longer applicable once an economy has become "naturalized" and has largely ceased to be a money economy, when equilibrium in the exchange of values has been replaced by proportionality in the distribution of the material elements of production in kind, when measurements in terms of value are being replaced by measurements of labor time or by substitutes for that measurement, and when, finally, production is subordinate not to the needs of accumulation or even to those of simple reproduction but rather to the task of consuming constant capital with deliberate intent and converting it into articles of consumption and armaments. For this reason, the categories of value are not appropriate for a scientific analysis of the concrete economy of War Communism. However, we know at the same time that our economy under War Communism had been in existence for too short a time to have worked out the accounting methods that were organically inherent in it, that is, an accounting of the material elements of the economy and the means of consumption, elements that could in the final analysis be reduced to labor costs and thus be rationally measured by labor time—in other words, those that could be measured in a socialist manner. Under War Communism we used surrogate devices for socialist accounting, such as the prewar ruble, the commodity ruble, and grain and other rations (forms of accounting in kind). We used a quantitative accounting of industrial output, a quantitative accounting of what had been received from requisitions on peasant production, and so on. This measurement in kind had no value parallel, as it does now, but rather constituted the basis for all our calculations. If we could draw up even an approximate balance for the national economy of Soviet Russia for each year of War Communism, that is, in part for 1918 but primarily for 1919 and 1920, we would discover that these were not annual balances of reproduction. We would establish the following basic economic facts:

(l)The complete elimination of capitalist production and capitalist trade from the economy left us with only two sectors: the sector of the state economy and the sector of petty production, which to a considerable extent had lost the character of commodity production because of the "naturalization" of the peasant economy and the collapse of craft and artisan industry.

(2) Only a very minor portion of the fixed capital of the state sector that was used up during each year of War Communism was replaced. Consequently, it was systematically eroded. The fact that all production in the state sector was earmarked for consumption had its consequences: since the fixed capital of light industry, which emerged from production in the material form of articles of consumption, was not replaced, the net result was an increase in the production of means of consumption at the expense of compensation for wear and tear on existing equipment. This situation radically upset the relation between the rate at which the fixed capital part of lie was being consumed in department II and the rate at which it was being reproduced in material form in department I. Not only did the resulting imbalance preclude expanded reproduction, it did not even meet the requirements of simple or even slowly declining reproduction. On the other hand, the part of the petty economy's means of production that previously had been produced in department I of the capitalist sector (or had been imported) was now also being consumed without replacement in department I of the state sector. Finally, the means of production of department I of the state sector that consisted of fixed capital were not replaced within that same sector, insofar as they were worn out in producing arms, including military transport vehicles. That is, they were swallowed up by nonproductive military consumption. All this meant the paralysis, above all, of the section of heavy industry whose function was to replace the fixed capital of IIc of the state and private sectors.

(3) The part of constant capital of the state sector that consisted of fuel, imported raw materials, and raw materials of peasant origin could not be reproduced in sufficient proportions, since we had lost control of basic fuel-producing regions (the Donets Basin and Baku) for long periods during the war; we were subjected to blockades; and the peasants had cut back production of industrial crops at the same time as they began processing more of these same crops for their own use.

(4) As regards exchange between city and country, the single most important fact explaining the inevitability of the entire system of War Communism is the following: Even if normal market exchange had taken place between the city and the countryside, an overall reduction of peasant production to 50 percent of its prewar level would have prevented the peasant economy from supplying the city—on the basis of exchange—with the quantities of articles of consumption, industrial raw materials, and direct labor (freight transportation and so on) needed by the state during the Civil War. And, conversely, even if the countryside had been able to supply all these values through normal market exchange, then state production, considering that the volume of its output was at a minimum whereas nonproductive consumption brought about by the war was enormous, would have been objectively unable to replace the goods that it received from the peasantry, even through grossly nonequivalent exchange and even with a high monetary tax on the countryside. This becomes quite obvious if we take the total production of means of consumption in state industry (in prewar rubles), subtract what was consumed by the city and the military, and then compare what might have been left over for exchange with the value (also in prewar rubles) of everything that was obtained through the requisitions on the peasantry. Although the discrepancy was not so great during the first year of War Communism —the Soviet government still had available old, prewar stocks—by 1920, the year that most typified War Communism, the peasantry was already delivering much more to the cities than it was getting in return. This demonstrates that market exchange relations between the state economy and petty production were completely impossible in that period.

The fact that the economy of that period was geared to military consumption was expressed in another way as well. When industrial products were supplied to the countryside in accordance with the state plan, the Committees of Poor Peasants distributed these goods among the rural inhabitants in a special way: it was not the strata that had supplied the greatest amounts to the state under the requisition that received the most in return. Rather, it was just the opposite. It was the poorest peasants who got the most, the peasants who had given nothing material to the state but who were lending it their political and military support in the Civil War. Hence, distribution of urban products was doubly nonequivalent, first in the sense that much less was returned to the countryside than had been obtained from it, and second in the sense that there was a principle of unequal distribution within the countryside itself. This class-based distribution, which ignored the exigencies of reproduction in the peasant economy, was countervailed to some extent by illegal exchange between the city and country, "bag trading," as it came to be called.1 Here, the countryside took a measure of revenge, as it were, upon the distribution system that had been imposed upon it by the city. By exchanging grain, potatoes, and other foodstuffs, it bought for a mere trifle the cloth, footwear, furniture, and other items that had been stored in the cities for years.

The contradiction between city and country grew, and the peasant uprisings in late 1920 and early 1921 brought attention to bear on the urgent question of how the system of exchange in the Soviet economy could be adapted to the conditions of commodity production in agriculture. This adaptation took place with the transition to NEP. But the reasons for going over to NEP were rooted within the state economy itself, since it was entering into a peaceful period of existence. In our peasant country, the transition of the state economy from the declining reproduction of wartime to the expanded socialist reproduction of peacetime required changes in the relations between proletarian industry and the peasant sector. It demanded a market system of exchange and incentives for the production of peasant raw materials needed for state industry, the growth of exports, and so on. In examining these changes, however, we must be careful to distinguish between two different categories. First, certain changes were made in the methods of managing the state economy in order to squeeze everything of value from the usual capitalist techniques of accounting, calculation, and so on in the first stages of socialist construction; in other words, these were changes introduced in the interests of the state economy itself at a given level of socialist culture. These changes in the country's economy must not be confused with those that were imposed upon the state economy by the predominance of petty commodity production in the country. Had it been a question of the first years or the first decade of socialist construction in a country such as contemporary Germany, then the general conditions of development of a socialist economy might perhaps have required us, too, to maintain a market system of exchange until the methods of distribution appropriate to the socialist form of production had been discovered through experience. We, too, would perhaps have left not only petty trade but also medium-scale trade where the state sector still had dealings with the relatively insignificant private economy. But the conditions conducive to the development of commodity relations, i.e., the development of private capital in its various forms, would not have existed. However, in the USSR such a development, especially in agriculture, is an unavoidable fact, imposed upon the country's economy by the enormous preponderance of petty commodity production combined with the relative weakness of the state sector. This fact forces the state economy into an uninterrupted economic war with the tendencies of capitalist development, with the tendencies of capitalist restoration, which are reinforced by the outside pressure exerted on our economy by the world capitalist market. For this reason, our economic system cannot enjoy the internal stability that characterized the countries of youthful capitalism as it dissolved feudal relations and subordinated petty commodity production to itself. This solitary battle, waged by the socialist elements of the economy against the capitalist elements that are buttressed by the huge block of petty commodity production, leads as well to a dualism in the sphere of control or, in other words, to specific equilibrium conditions within the system as a whole.

An analysis of equilibrium conditions in the present-day Soviet economy necessitates the division of the economy into three sectors: (a) the state sector, (b) the private capitalist sector, and (c) the sector of simple commodity production. The nature of the investigation, however, will frequently require us to counterpose the first sector to the other two taken together, since the two combined represent the private economy as a whole, and the lack of necessary data on the capitalist sector means that the only way to make a concrete study of reproduction is to divide the economy into two sectors.

The second feature—and this is what makes the investigation so difficult—is the fact that equilibrium of the system is not attained on the basis of the law of value of equivalent exchange, but rather on the basis of a clash between the law of value and the law of primitive socialist accumulation. For this reason we cannot, in analyzing equilibrium, start from Marx's assumption that commodities are usually sold at their value. In volume II of Capital, Marx, in posing the question of analyzing reproduction, makes the following reservation in connection with this point:

It is furthermore assumed that products are exchanged at their values and also that there is no revolution in the values of the component parts of productive capital. The fact that prices diverge from values cannot, however, exert any influence on the movements of the social capital. On the whole, there is the same exchange of the same quantities of products, although the individual capitalists are involved in value-relations no longer proportional to their respective advances and to the quantities of surplus-value produced singly by every one of them.2

As we have already shown, this assumption by Marx is quite correct when one is analyzing equilibrium in a capitalist economy. However, when we analyze reproduction in our system, we start from the rule that prices diverge from values, as a rule, when we compare our domestic prices with world prices. From the standpoint of equilibrium, the distinguishing feature of our economy during the period of primitive socialist accumulation is precisely that it lacks the equivalent exchange toward which a capitalist economy naturally gravitates, and which it attains with greater or lesser deviations, primarily on the basis of free competition and by giving free rein to the law of value in the distribution of social labor. Under capitalism equivalent exchange may be considered the dominant tendency, no matter how numerous the variations in the general pattern and no matter how much these deviations accumulate historically as capitalism enters its monopoly stage. In the Soviet economy, on the other hand, during the period when the entire technological basis of the state sector is being replaced, the rule is nonequivalent exchange. This nonequivalence underlies the whole existence of the state economy, and it constitutes one of the most important features of our system at the present stage of its development. War Communism meant, first, nonequivalence of exchange (razmen)*3 of the products of state industry for the products of the countryside alienated from the peasantry through requisitions and second, absence of the market, commodity-money form of such exchange (razmen), that is, the absence of market exchange (obmen). Under War Communism the level of development of the productive forces in both the state and the peasant sectors was so low, and nonproductive military consumption so high, that the market form of exchange (obmen) would not have stood up under the pressure of the redistribution of national income necessitated by the Civil War. Conversely, if the market system of exchange (obmen) had held up, then the specific pattern of income distribution demanded by wartime conditions could not have been sustained, and with that the chances for victory might have been destroyed. As regards the period of NEP or, more precisely, the period of primitive socialist accumulation, the development of the productive forces in both sectors not only permits but even demands a market form of exchange (obmen) capable of guaranteeing the state economy the necessary conditions for its existence and development. But exchange (razmen) of the products of the state and private sectors, especially between state industry and the peasant economy, can still not be equivalent, either in terms of relating the labor actually expended on the products exchanged or in terms of their relation to the proportions of exchange (obmen) prevailing in world economy. Our system could not have sustained an equivalent exchange (obmen) controlled by the world market, and the whole process of reconstruction of the state economy would have necessarily come to a halt.

Thus, economic equilibrium in the Soviet system during the period of primitive socialist accumulation differs from the period of War Communism in two respects: we have now reestablished the link between the state and private sectors on a market basis and, additionally, the capitalist sector has reappeared on the scene. On the other hand, the present system resembles War Communism in the nonequivalence of exchange, which continues to exist, although in a much less extensive form as compared with 1919—20. This circumstance does not hinder all those investigators who build an unbridgeable gulf between War Communism and NEP and are incapable of scientifically establishing the historical continuity between the two forms of economic regulation. Apart from the fact that NEP did not in the slightest alter the system of ownership of large-scale industry and transportation, it retained a continuity with the era of War Communism and maintained an attenuated version of nonequivalence of exchange. To uncritically hold War Communism responsible for things that spring from the general economic backwardness of our country amounts to no more than childish stupidity and a failure to understand cause and effect in our economic history. To whom, indeed, is the complaint addressed that the level of development of the productive forces in our country was low and will continue to be so for a long time to come? One has to understand the consequences to which this leads at various stages of the existence of the Soviet system.

However, although during the period of primitive socialist accumulation we hold to nonequivalent exchange (obmen), using it for the reconstruction of our technological base, that does not mean that we will hold out for very long in such an extreme position if we do not overtake capitalism but continue to lag behind it or, while moving forward, nevertheless maintain the same relative distance from it in technology and in the development of our productive forces. Nonequivalent exchange (obmen), with all the apparatus for safeguarding it, such as the foreign trade monopoly, planned imports and rigid protectionism, may be an obligatory condition for the existence of the Soviet economy, with its state sector, but if our economy is to continue to exist, it is just as necessary that nonequivalence be gradually overcome and that our productive forces be brought to the level of the most advanced capitalist countries. These are the two equilibrium conditions of our system, insofar as they are connected with expanded reproduction of socialist relations, that is, with precisely that which distinguishes us from capitalist economy, and insofar as it is a question of the reproduction of capitalist relations in an economically backward country at a time when that backwardness is in the process of being overcome.

We must now make some preliminary observations on the capitalist sector of the Soviet economy. We have seen that as long as our economy lags behind capitalism both economically and technologically the existence of the state sector is the main source of nonequivalent exchange (which essentially comes down to a tax on the whole economy for the benefit of socialist reconstruction). But it is quite incorrect to infer from this that the capitalist sector of the Soviet economy, taken as a whole, is the domain of equivalent exchange or that it in general has inherent tendencies toward more equivalent exchange even within the bounds of the Soviet economic system. We must bear in mind that the commercial and industrial segment of the capitalist sector on the one hand and its agrarian segment on the other do not gravitate toward equivalent exchange to the same degree. The basic proportions of the domestic price structure are established by the interplay between state industry and transportation and the peasant economy. Private industry is incapable of altering these proportions, nor is it the least bit interested in doing so. It plays a passive, parasitic role here. Whereas nonequivalent exchange is for the state sector the material source of technological reconstruction and a prerequisite for the development of the productive forces in coming years, private industry merely clings fast to the existing situation. It finds its way into the pockets of nonequivalent exchange between large-scale Soviet industry and the countryside in order to accumulate, but without ever embarking upon productive industrial accumulation. Hence it can itself never help lower production costs, nor can it ever begin to compete with state industry in a positive manner. The only place where private industry successfully competes with state industry is in a few branches of light industry where expensive machinery does not yet play an important role or is inapplicable and where the role of personal initiative and energy, of personal involvement in the business, is relatively great. And even in these industries, the private entrepreneur's success rests chiefly on the extreme exploitation of labor power, often that of his own family. The bourgeoisie prefers to keep its accumulated resources in money form and feels that it is risky to convert them into the hard and fast form of new instruments of production. This is precisely the predicament in which private merchant capital finds itself. When a goods famine is compounded by poorly organized distribution in the state system of cooperatives (especially when that system has only existed for a few years), the private trade apparatus takes advantage of market trends to augment its normal profit and, in general, trades at higher prices than the state cooperative system. Here too, private capital plays chiefly a parasitic role in the sense that it takes advantage of the favorable economic situation provided by nonequivalent exchange—a situation that it itself did not create—while doing nothing to help attain greater equivalence.

The agrarian half of the capitalist sector, represented by the kulak and the well-to-do peasant, who is already halfway along the road toward systematic exploitation of the labor of others, finds itself in a different situation. Later on we will discuss the relative influence of this element of the capitalist sector and its growing importance in the country's economy. For now, let us merely note that the main weight of the capitalist sector, insofar as it will develop at all, will undoubtedly shift to its agrarian segment, where accumulation occurs in the form of means of production and of land leased from the poor peasants. It is the agrarian capitalism of the Soviet system that suffers first and suffers most from nonequivalent exchange, because the kulak buys more than the middle peasant and hence overpays more at our domestic prices as compared with world prices. The kulak sector sells more, and expanded reproduction within that sector can take place only through market exchange. Only through market exchange can the kulak sell the growing volume of his output, including the part that constitutes his surplus value. That is why the kulak is so pointedly and consciously hostile to the present economic order, although indeed to a certain extent the entire peasantry suffers from nonequivalent exchange insofar as it is dependent on the market and has not withdrawn into the shell of a natural economy. The kulak tries to offset the nonequivalence of exchange with the town, hoping that by not selling in months when the poor and middle peasant strata are marketing grain at the prices fixed by the state, he can thereby drive up grain prices in the spring. He experiments with replacing certain crops with other, more profitable ones. He tries to avoid the market and accumulate in kind by raising more livestock and poultry from his own production, by constructing new farm buildings, and so on. But the possibilities for such economic maneuvers are not very great, and in the end the kulak is forced into a confrontation with the entire Soviet system. And the longer it takes for this confrontation, the more the kulak will be inclined to seek a solution to the problem not by economic means within the Soviet system, not in a partial adjustment of the equilibrium in his favor, but by attempting to force his way through to the world market by counterrevolutionary means. Here, the problem of economic equilibrium rests squarely on the problem of social equilibrium, that is, the relation of class forces for and against the Soviet system. Two systems of equilibrium are struggling for supremacy: on the one hand, equilibrium on a capitalist basis—which means participation in the world economy regulated by the law of value—by abolishing the Soviet system and suppressing the proletariat, and on the other hand, equilibrium on the basis of temporarily nonequivalent exchange serving as the source of socialist reconstruction and inevitably signifying the suppression of capitalist tendencies of development, particularly in agriculture.

Marx's analysis of proportional distribution of labor under pure capitalist reproduction began with equivalent exchange as a necessary premise. In our own earlier analysis of equilibrium under concrete capitalism, we also began with this same premise. But from what we have just said above it is clear that the investigation of reproduction in the economy of the USSR that we are about to begin must start with nonequivalent exchange, even though the latter is to be gradually and systematically eliminated. But this means that we always have to assume that the entire process is based upon the existence of two different systems of ownership of the means of production, and two different regulators of economic life, that is, the law of value and the law of primitive socialist accumulation.

If we take the terminology Marx used to describe the capitalist economy and apply it in a conditional sense to the state economy and to the petit bourgeois sector, we will obtain the following algebraic scheme for the three sectors of the economy:

State Sector

Department I. c + v + surplus product. (surplus product

Department II. c + v + surplus product ' from other sectors)

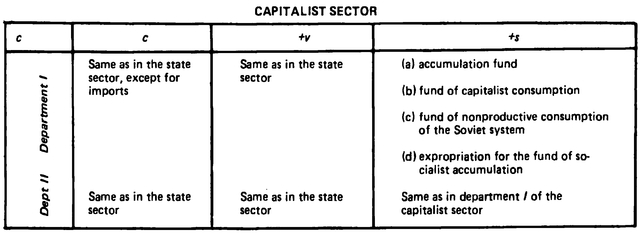

Capitalist Sector

Department I. c + v + s

Department II. c + v + s

Petit Bourgeois Sector

Department I. c + consumption fund + surplus product

Department II. c + consumption fund + surplus product

However, the above scheme is inadequate for our purposes, because it fails to give an idea of how the individual magnitudes are broken down from the standpoint of their exchange with different departments of different sectors. A more detailed scheme, which we will use in the rest of this discussion (although we will often be taking the two private sectors together), would need to have the following form: [see pp. 182-83].

Let us say a few words to clarify this scheme, which even in the form presented far from exhausts all the various directions along which exchange proceeds in expanded reproduction in our system.

From the standpoint of exchange, the constant capital of department I of the state sector can be broken down into three parts: the first part is reproduced within the department itself; the second is reproduced by exchange with department I of the capitalist and petit bourgeois sectors; the third is reproduced by imports of means of production from abroad.

Wages of department I of the state sector are divided into two parts: one part is exchanged for means of consumption produced in department II of the state sector; the second part is reproduced by exchange with departments II of both the capitalist and petit bourgeois sectors.

The surplus product of that same department can be broken down into (1) an accumulation fund that is distributed proportionally between c and v, with the appropriate exchange of the additional v for means of consumption, and (2) a nonproductive consumption fund. The latter fund is consumed in natura in the same department only in the form of means of production for war industry, whereas the remaining part is exchanged with departments II of all sectors.

The constant capital of department II of the state sector is reproduced in the following ways: by exchange of means of consumption against one part of the wages fund of department I of the state sector, by exchange with the consumption fund4 of the capitalist and petit bourgeois sectors (chiefly for peasant raw materials), or by imports of means of production (in the form of both machinery and raw materials such as cotton, wool, rubber, and hides).

The wages of department II of the state sector are reproduced in part within the department itself, in part by exchange with the consumption fund of the petit bourgeois sector, and in part by mutual exchange for IIv of the capitalist sector.

The surplus product of department II of the state sector can be broken down in the same way as the surplus product of department I, that is, it consists of an accumulation fund and a nonproductive consumption fund. The latter is consumed in natura; the former can be broken down into two parts: one consists of additional v and is reproduced on the lines of the entire IIv of the state sector; the other, which is earmarked for the purchase of means of production, is reproduced on the lines of IIc of the state sector.

We will not make a detailed examination of exchange between the capitalist sector and the other sectors, since this process is clear from the above analysis of the departments of the state sector, The difference lies in the apportionment of the surplus value. Here we have two additional elements: the consumption of the capitalist class, which modifies the exchange of means of production for the means of consumption produced in the individual

sectors; and the deduction from s for the socialist accumulation fund, which also complicates the analysis of reproduction.*

The means of production for department I of the petit bourgeois sector, which consist of machinery, cattle, seed, fertilizer, and so on of peasant farms engaged in producing technical crops, as well as of the equipment and raw materials of a certain part of handicraft industry, are divided into two parts. One part is reproduced within the department itself; the other may be obtained by internal exchange for Ic of the state sector or (at least in part) by imports.

The consumption fund of department I of the petit bourgeois sector, which has the material form of means of production, is exchanged in two directions: for IIc of the state sector and the capitalist sector on the one hand and for a part of the means of production fund of department II of the petit bourgeois sector itself on the other.

The surplus product of department I of the petit bourgeois sector is divided into three main parts: (a) an accumulation fund; (b) a nonproductive consumption fund,5 whose size is determined by the extent to which the department in question is compelled to help cover it; and (c) a socialist accumulation fund, which goes into the state sector.

The accumulation fund, in turn, consists of (a) additional means of production produced within the department itself, which go to increase its own c in natura, by way of internal redistribution, that is, without engaging in exchange with other sectors; (b) means of production that are exchanged for means of production produced in department I of the state and capitalist sectors; (c) means of production in natura, which serve as an extra consumption fund for new workers and which therefore, in order to be consumed, must be exchanged for means of consumption from the departments II of all three sectors in the same proportions as the overall consumption fund of this particular department.

The nonproductive consumption fund, which is similar to the nonproductive consumption fund of department I of the state sector (excluding means of production for war industry), must be transformed into articles of consumption by exchange in the correct proportions with departments II of all three sectors, replacing their constant capital.

The portion of the surplus product that goes into the fund of socialist accumulation consists, first of all, of the part of taxes levied on petty production that is destined not for the nonproductive consumption of the employees of the state and the trade network but rather for increasing the capital funds of the state sector, including state funds for agricultural credit. Secondly, it includes the part of the fund of primitive socialist accumulation formed by exchanging the export fund of petty (chiefly peasant) production, which is valued in terms of domestic prices (which are lower than world prices), for the import fund of means of production for the state sector, also valued in terms of domestic prices (which are much higher than world prices).6 If we consider the entire process of reproduction in the USSR in terms of the value relationships of the world market, we have to include in this fund the entire balance resulting from the exchange7 of state output for private output, taking the output of both the state sector and the private sectors in terms of world market prices and deducting from the total the part that is absorbed by nonproductive comsumption.

The means of production of department II of the petit bourgeois sector consist of four parts. The first and largest part is reproduced in department II itself, since we are concerned primarily with peasant agriculture. Included here are seeds set aside from the harvest, the peasant's production of his own work stock, his own production of feed for his livestock, his own fertilizer, his own buildings, and so on. The second part is reproduced by exchange for the consumption fund of department I of the petit bourgeois sector or for part of Iv of the capitalist sector. The third part is exchanged for part of the wages fund of department I of the state sector. The fourth part is reproduced through imports.

The consumption fund of department II of the petit bourgeois sector consists of two parts: the first and by far the greater part is reproduced within the department itself; the second, considerably smaller part is exchanged for part of the wages fund of department II of the state and capitalist sectors.

As regards the fund of surplus product of department II of the petit bourgeois sector, it can be broken down into the same four parts as the surplus product of department I of that sector; the difference consists in all the changes in the system of exchange that are associated with another material form of the aggregate product. More precisely, the accumulation fund is divided, above all, proportionally between the extra consumption fund and a fund of additional means of production, where the extra consumption fund has the same composition as the basic consumption fund. The distinction between the process of reproduction of this fund and the reproduction of the same fund in department I of the petit bourgeois sector consists in the fact that in department I, before exchange occurs, this fund has the material form of means of production, all of which must be exchanged for means of consumption, whereas here—that is, in department II—this fund has, from the very beginning, the natural form of means of consumption, and the bulk of it is also consumed here. Only its minor part is exchanged for means of consumption of the other two departments II. The fund of extra means of production, in turn, has the same composition as the means of production of that department in general. This means that part of the fund of extra means of production is created in the petit bourgeois sector itself, whereas the other part is obtained through exchange with other sectors.

Here, as earlier, we use the term "nonproductive consumption" to mean the part of the surplus product of a given sector that enters into the income of groups in Soviet society that represent nonproductive consumption: expenditures for the state apparatus, the army, the nonproductive part of expenditures on trade, and so on. The difference between the second and first departments of the petit bourgeois sector is that in department II the nonproductive consumption fund has, from the very outset, the material form of articles of consumption and is not subject to further exchange with other departments, as is inevitable for the nonproductive consumption fund that consists in natura of means of production.

As regards the surplus product destined for the fund of socialist accumulation, everything that we have said with respect to department I of the petit bourgeois sector applies without change to department II as well.

The scheme of reproduction in the system of the USSR that we have just presented enables us to define the general conditions of proportionality in an economy of the particular type and in the particular period of its existence that we are investigating. We must define these general conditions before we use the above scheme to analyze numerical data from specific years and before we attempt to replace the algebraic symbols with specific arithmetical figures, such as those of the economic years 1925-26 or 1926-27.

Let us begin with the conditions of equilibrium between the entire state sector and the two sectors of the private economy taken together, from the standpoint of ensuring expanded reproduction in the state sector. For the time being we abstract from the material composition of the output being exchanged.

Let us assume that the gross annual output of the state sector is equal to 12 billion chervonets rubles (in present prices) and that it can be broken down as follows: 8c + 2v + 2 surplus product. (In 1925—26 the gross output of the state economy, in producer prices, together with revenue from transport, communications, municipal services, and forestry, plus the gross output of construction, was 14.35 billion rubles, not including some minor items.)

Let us further assume that the exchange fund with private production as a whole totals 3 billion rubles, that is, that the state sector sells means of production, articles of consumption, and transportation services for 3 billion chervonets rubles to the private economy and obtains from the latter an equivalent amount of means of production (chiefly peasant raw materials), articles of consumption, and an export fund.8 We thus have an even balance of exchange between the two sectors, that is, without any one-sided accumulation of undisposed-of commodity surpluses. Let us now assume that the entire economy of the USSR is integrated into the world economy on the basis of the free operation of the law of value, and that world market prices are forcibly imposed upon our industry, which maintains the same volume of exports and imports—that is, we disregard, for the time being, the possibility of changes in foreign trade flows. The entire equilibrium will then be upset, particularly that between the state sector as a whole and the sector of the private economy. To be more precise, let us assume that the entire output of the state sector is now valued at world market prices, that is, at one-half—or less—the prices it is valued at now. If within the state sector the part of the output of department I that goes to replace part of the constant capital of department II (machinery, fuel for the production of means of consumption) is approximately equal to the part of department II's output that in turn goes into department I (that is, textiles, shoes, sugar, and so on), then the forced lowering of prices will not essentially change the material proportions of exchange within the state sector itself, provided that the relative price increase on the output of heavy and light industry of the state sector does not differ appreciably from the relative price index of heavy and light industry of the world economy (if, say, means of consumption produced in our state industry are twice as expensive as the output of light industry in the world economy, and the prices of machinery are twice as high as the prices of machinery produced abroad). To take a hypothetical example, if one of our machine-building trusts now sells its machines to our textile industry at half the present price, then the textile industry will in turn sell its textiles, which are earmarked for the consumption of the workers and employees of the machine-building industry, at half the present price as well. In short, since the purchasing power of money changes simultaneously for both sides, the material balance of exchange will remain the same as if they valued their output not in terms of 1927 chervonets rubles but in another monetary unit, say, in terms of the purchasing power of the pound sterling on the world market. All this may entail gains or losses for particular branches whose prices are either less than or more than twice world prices. In such an event, when exchange between departments I and II of the state sector does not balance and the remainder is covered by exchange with private production, the principal loss is borne by the department of the state sector that proves to be more dependent on exchange with the private sectors.

In this particular case, however, the most important change occurs in the interrelations between the state sector as a whole and private production as a whole. The link between the state sector and the whole of private production is by no means limited by the size of the balance that is not covered internally, that is, through exchange within the state sector. Department I of the state sector must under all circumstances sell to private production a quantity of means of production equal in price to the part of the wages of its workers that is used to purchase consumer goods of peasant origin plus a corresponding part of means of production to compensate for a portion of the nonproductive consumption of department I of the state sector, excluding means of production for war industry. The volume of exchange between department II of the state sector and the private economy is even larger. By means of this exchange, this department replaces a considerable part of both its constant capital and its wages fund. In our example, which is numerically close to the actual figures for exchange between the state sector and the private economy during the economic year 1925-26, purchases by the private sector from the state sector and those by the state sector from the private sector each came to a total of 3 billion rubles.

If the private economy sold this 3 billion of its output at world market prices, then sales by the state sector to the private economy at world market prices—that is, at half-price—would mean that the state sector would make only 1.5 billion rubles on its output instead of 3 billion. That is, the state sector would receive only half of what it would obtain in an economic year in which conditions of nonequivalent exchange prevailed. A mere glance at our numerical example shows quite clearly the kind of disruption this would create in all aspects of reproduction in the state sector. The shortage of 1.5 billion absorbs, first of all, the entire accumulation fund. Secondly, it affects a certain part of nonproductive consumption. Thirdly, it makes it impossible later on to properly amortize fixed capital, as well as to replace the part of circulating capital that consists of peasant raw materials. On the whole, this would mean total breakdown of the process of expanded reproduction and, as long as nonproductive consumption remains substantial, could preclude the possibility of even simple reproduction at the previous year's level.

An even greater disturbance would occur if the establishment of world market prices on raw materials and means of consumption produced in the private economy would mean an effective price rise as compared to the way things stand now.

We thus arrive at a first and most highly significant conclusion: Given a discrepancy between world industrial prices and domestic industrial prices in the USSR, that is, when domestic prices of Soviet industry are much higher than world prices, an economic equilibrium that will ensure expanded reproduction in the state sector can only be brought about on the basis of nonequivalent exchange with the sectors of private production.* This means that, given this sort of price discrepancy, the law of primitive socialist accumulation is the law that maintains the equilibrium of the entire system, above all in its relations with the world economy. This law must of necessity operate until we have overcome the economic and technological backwardness of the economy of the proletarian state as compared to the advanced capitalist countries.

Let us now proceed to the next condition of equilibrium of the system, once again confining our attention for the time being to the interrelations between the state sector as a whole and private production as a whole.

Let us take our numerical scheme for the state sector and assume that a new economic year starts out with the results of the previous year's accumulation. We assume, therefore, that if we have a surplus product of 2 billion in the state sector—of which half goes to nonproductive consumption and half to productive accumulation—and if the exchange fund with private production increases from 3 billion rubles to 3.25 billion,9 equilibrium in the entire economic system will be ensured. Let us now consider the opposite case, namely, that actual accumulation for some reason—either because of a sharp drop in disposal prices not justified by costs of production or because of a growth of nonproductive consumption—is only 700 million rubles instead of 1 billion. What will be the inevitable consequences of this underaccumulation in the state sector?

It is quite obvious that this will upset the proportionality between the state and private sectors of the Soviet economy. Underaccumulation by 300 million rubles will mean that the reproduction of c cannot be expanded within the bounds required in both departments: there will be a deficit of 240 million rubles in means of production. At the same time, the expansion of v in both departments of the state sector will be 60 million rubles below normal, which, in addition to everything else, will mean a slower increase in the number of workers employed in production and therefore a relative increase in unemployment. Finally, this would result in a 60-million-ruble decrease in the surplus product in the state economy as a whole. With respect to the total output of the state sector, we will have at the end of the year a shortage of production of 360 million rubles as compared to the first example. 10 If, as we have said, the share of the state sector's output absorbed by the private sector is 3.25 billion rubles, that is, almost one-quarter of the total gross output of the state sector, a shortage of 360 million rubies in production can mean a shortage of goods for the private sector of at least 90 million rubles.*But this will give rise to that well-known phenomenon we call the goods famine. If two-thirds of this 90 million rubles represents means of consumption produced in the state sector, the failure to satisfy the effective demand of the private economy, above all, that of the peasant sector, will mean a forced cutback in the peasantry's individual consumption of the products of state light industry and to the substitution of domestic handicraft output for factory products—that is, it will encourage the processing of raw materials (leather, wool, flax, and hemp) by primitive domestic methods and thus tend to delay economic development in this sector. Second, the peasants will refrain from selling their output for export and will consume more of their own foodstuffs themselves. Third, this disproportion will increase the discrepancy between retail and wholesale prices in the trade network, especially in private trade. As regards the remaining one-third, which consists of unmet demand for means of production, the disproportion will have much more harmful consequences: one cannot, after all, smelt metal, produce complicated agricultural machinery, and so on by handicraft methods. Under conditions of expanded reproduction, peasant agriculture will not be able to increase the quantity of machines, stocks, and other means of production it needs. In both departments of the petit bourgeois sector, recurrent goods famines will inevitably—since sales cannot be followed by purchases—cause the peasantry to refrain from selling a part of its output and will encourage the appearance of the familiar phenomenon of accumulation of unsold stocks in kind in the peasant economy. This disproportion can be alleviated only by monetary accumulation in the peasant economy, which is generally possible only if there is either a stable currency or if the purchasing power of money is rising because of falling prices. However, it is self-evident that such accumulation, insofar as it corresponds to the part of the peasant economy's reserves that ought to have been converted into means of production produced in the state sector, inevitably means an artificial delay in the process of expanded reproduction in the peasant economy as compared to the possibilities for expansion that actually exist within it.

It follows quite clearly from this discussion that (1) the volume of accumulation in state industry at a given price level is not an arbitrary magnitude but is subject to iron laws of proportionality, the revealing of which constitutes one of the most important tasks of a theory of the Soviet economy and of the practice of planned management of economic life, and (2) any perturbation in the necessary minimum of accumulation not only is a blow to the state economy and to the working class but also retards the development of the peasant economy by artificially slowing the pace of expanded reproduction in agriculture.

Let us now look at the same question, but from a different angle: let us look at what some economists, who draw an uncritical analogy between the Soviet system and capitalism and who fall into petit bourgeois Philistinism, at one time tended to call "over-accumulation in state industry" and "industry running ahead." To begin with, we have to decide what we mean by the term "over-accumulation." If by overaccumulation we mean a relationship between production and consumption throughout society such that new means of production put into operation in both departments lead in the final analysis to so sharp an increase in the production of means of consumption that these goods cannot be absorbed by the consumer market at existing prices, as a result of which the corresponding accumulation in department I proves to be useless—well, then, such a phenomenon is quite well known in capitalist economy and must inevitably lead to a sales crisis, the ruin of numerous enterprises in both departments, a forced lowering of prices, and a fall in the rate of profit. If, in a theoretically conceivable case, our state economy were on the basis of the previous year's accumulation to turn out means of consumption in excess of the effective demand of both the workers and the entire state economy at given planned prices, then the situation would be much less serious than in a capitalist economy. The reason for this is as follows. Dynamic equilibrium in our system presumes among other things: (1) a growth of workers' wages, (2) a gradual decline in industrial prices, (3) reequipment and expansion of the entire technological base of the state economy. The appearance of a sales crisis may, under such conditions, mean one of three things:

(1) We have miscalculated the time needed to carry out the first two points of the program. In this case, equilibrium can be attained either by raising wages above the levels called for in the program or, more radically, by lowering the general level of prices on articles of consumption produced in the state sector more rapidly than the program calls for. In that case the disproportion may be overcome very quickly and without any special perturbations, and "overaccumulation" will prove to be a crisis in the production plan only in the sense that the plan incorrectly estimated the time needed to fulfill the first two tasks. Moreover, we must not forget that, given our general shortage of reserves in the areas of credit, production and trade, the disproportion cannot long continue to build up in hidden form, as is usual under capitalism, and that its elimination must inevitably begin much earlier, before the whole process goes too far. The harmful consequences of this sort of planning error will reveal themselves later, in that there will be a delay in fulfilling the third task mentioned above.

(2) The sales crisis may mean that we have miscalculated the time needed to carry out the third task. That is, we have expanded the production of means of consumption, at prevailing prices, too far and too fast: the technological base of the state economy and the degree of rationalization of labor that has been achieved are inadequate to permit a lowering of the cost of production, a lowering of selling prices or, in the worst case, even just an increase in wages. In this situation, "overaccumulation" proves to be the result of an incorrect distribution of the productive forces within the state economy, the result of the fact that the process of technological reequipping of industry has lagged behind the overall development of the economy as a whole. What we have here is an internal disproportion within the state sector, not overaccumulation in terms of the interrelations between the state economy and private production. Solving this crisis by lowering prices—a lowering of the cost of production for which the economic basis has not been prepared—could temporarily delay the entire process of expanded reproduction, just as it would be delayed if we tried to solve the problem by letting a part of production remain in the form of a nonliquid fund while maintaining the prevailing price level. This lack of correspondence would continue until a redistribution of productive forces restored equilibrium.

(3) The reequipping of fixed capital, which proceeds unevenly, draws so many means of production into the production of means of production that themselves do not begin turning out goods until several years later, that all this retards the growth of the population's consumption fund and, with the occurrence of a goods famine, arrests the process of lowering prices. In that case we will have not general over accumulation (otherwise a goods famine could occur, even if only with respect to means of consumption) in the state sector but a temporal disproportion in the particular tasks of expanded reproduction. We would then be confronted not so much with an error in drafting the plan as with the natural result of the transition from the restoration process to the reconstruction process. We would be confronted with the natural consequences of the situation wherein the country's fixed capital, which had been severely depleted by the failure to make up for the depreciation losses of previous years, was being renewed under conditions of limited ties with the world economy and of a general shortage of internal accumulation in the material form of means of production. What appears superficially as overaccumulation in heavy industry is merely a special form of underaccumulation throughout the state economy, taken as a whole. The very nature of the renewal of fixed capital under the conditions we have described is such that this process must necessarily occur unevenly. To expand the annual production of means of consumption in state light industry by, let us say, 100 million rubles, we first have to increase the production of means of production by 400—500 million. This may temporarily slow down the necessary rate of production of means of consumption, bring about a special kind of goods famine, and delay the lowering of prices, especially in the case when a shift in the structure of the peasant budget leads to a heavier demand for means of consumption than before the war. But in return, it will within a few years enable us rapidly to reduce the cost of production, lower selling prices, and rapidly increase the consumption fund. Instead of a systematic lowering of prices (let us say, 2—3 percent per year), and a systematic increase in the production of means of consumption (let us say, 6-7 percent per year), the same program can be carried out in three to four years, only in more uneven form. If we disregard the political difficulties of this period, the harmful economic consequences of such a development of the state economy will essentially amount to the fact that production of export crops will be slowed down in the peasant economy and the production of industrial crops will prove to be lower than the demands made upon it by the rapid development of state light industry. For the most part, this latter difficulty for our economy still lies before us, whereas the artificial cutback in peasant exports is already at hand. In terms of the overall progress of the state economy, the case we are examining will imply not a crisis of overaccumulation and overproduction in the strict sense but simply the material impossibility of harmoniously coordinating the development of all aspects of expanded reproduction with respect to time. In the transition from restoration to reconstruction this will, generally speaking, be unavoidable, because the transition itself, as we will see in more detail below, implies a sharp change in the overall proportions of distribution of the country's productive forces. The fact that new plants do not start turning out goods until three to four years after their construction has begun is more the result of technical than economic necessity. An initial delay and then a forward jump are inevitable. The only possibility of partially evening out this jump is through greater exports and foreign credits. But these latter alternatives are impossible precisely because in the Soviet Union we have not merely expanded production but expanded socialist production of industry—a process that world capitalism is not inclined to assist.

Thus, we arrive at the conclusion that the volume of accumulation in the state economy in any given year is not an arbitrary magnitude, but that a certain minimum of accumulation is harshly dictated to us by the overall proportions of the distribution of the productive forces between the state and private sectors, as well as by the extent of our ties with the world economy. Second, we arrive at the conclusion that overaccumulation in the state sector, given the tremendous task of rapid reequipment and expansion of the fixed capital of industry (a task that will take decades to complete), is an absolute impossibility. This reequipping constitutes essentially a domestic market of colossal capacity, not to mention the growth of the domestic market on account of increased demand from the private sectors of our economy. Rather than talk about a crisis of overaccumulation in the state economy, a sector that does not have as its goal the production of surplus value, we can speak of a colossal underaccumulation, which is reflected in the peasant economy as well, in that it slows down its development. We may also speak of insufficient accumulation in the sphere of peasant production of industrial raw materials. We will deal with this sort of disproportion when we analyze the material composition of exchange between state and private production.

It must also be noted at this point that the two general conditions of equilibrium that we have so far examined differ from one another in the following respect. Equilibrium of nonequivalent exchange when there is a gap between domestic prices and world prices—that is, equilibrium of an economy regulated by the law of primitive socialist accumulation in struggle with the law of value—is a distinguishing feature of our economy; it is the law of our existence as a Soviet system throughout the entire period of struggle to overcome our economic backwardness relative to advanced capitalism. Here, equilibrium is attained as a result of the constant struggle waged by still backward collective production, the struggle waged by the only country with a dictatorship of the proletariat, against the capitalist world and against the capitalist and petit bourgeois elements in its own economy. Equilibrium of this type is the unstable equilibrium of a struggle between two systems; it is not attained through the workings of a world-wide law of value but on the basis of constant violation of this law, on the basis of constant violation of the world market, on the basis of the withdrawal—if not complete, then partial—of an enormous economic area from under the regulatory influence of the world market.

Things are considerably different when we talk about the second condition of equilibrium, that is, the proportions of accumulation in the state sector needed to maintain equilibrium in the economic organism after the first condition of equilibrium has already been met for a certain length of time. Maintaining equilibrium within an economic organism that is divided into a system of collective production and a system of private production brings state planning policy, guided by the law of primitive socialist accumulation, into a different sort of conflict with the law of value. If we do not in planned fashion hit upon the required proportions of distribution of the productive forces, given the existing correlation between domestic and world price levels, the law of value will burst through with elemental force into the sphere of regulation of economic processes and, forcing the planning principle into a disorderly retreat, will thereby encroach upon those specific proportions of the distribution of labor and means of production that will have been created as a result of the existence of the collective sector of the economy—those specific proportions that guarantee not merely expanded reproduction, but expanded reproduction in a system of the Soviet type.

Let us now go on to the third condition of equilibrium, which has to do with the extent of our participation in the world division of labor and the specific conditions under which this participation takes place.

Let us take our previous numerical example relating to reproduction in the state sector. Now, however, the nature of the question we must answer requires us to divide the annual production of the state sector into two departments. Let us assume that the distribution of the productive forces and of the output between the two departments is as follows: department I, 40 percent; department II, 60 percent.* To stick to reality, let us assume further that the organic composition of capital in department I is lower than in department II (in contrast to Marx's scheme; details on this later). The ratio c:v in department I is 3:2, whereas in department II it is 2:1. Let us further assume that the surplus product equals 100 percent of the wages and that it is broken down in both departments into two equal parts: one part goes to accumulation in the same department, and the other goes into the nonproductive consumption fund of Soviet society. The entire scheme will then have the following form:

| I. | 2,100c + l,400v + 1,400 surplus product (700 to the accumulation fund; 700 to the nonproductive consumption fund) | = 4,900 |

| II. | 3,550c + 1,775v + 1,775 surplus product (887.5 to the accumulation fund; 887.5 to the nonproductive consumption fund) | = 7,100 |

Even a cursory glance at this scheme shows a major difference as compared to the corresponding schemes used by Marx to illustrate capitalist production. Not only is IIc of the state sector considerably greater than wages and nonproductive consumption in department I of the state sector, but it is also greater than the wages plus the entire surplus product of department I. All this is quite natural in a peasant country where a very large part of IIc of the state sector is reproduced by exchange with the the petit bourgeois economy, which provides our light industry with such means of production as cotton, flax, hemp, hides, wool, sugar beets, oil seeds for the oil-extraction industry, grain for the mills, and potatoes for the alcohol industry. Let us assume that half of IIc of the state sector, or 1,775c, is reproduced through exchange with private production.11 That is, we choose in advance a figure that exceeds the actual size of what IIc reproduces through exchange with petit bourgeois economy. The question now arises: How can the other half of IIc be reproduced?

For the reproduction of that half, we have first of all a wages fund of department I that is equal to 1,400. However, not all of this sum can go to replace half of IIc, because part of the wages of department I must be exchanged for peasant means of consumption. Let us assume that the latter exchange required one-third *of 1,400, or 466.6. A fund of 933.4, which has the material form of means of production, then remains for exchange against IIc. Furthermore, since 700 of the surplus product goes to accumulation in department I, a nonproductive consumption fund of 700 remains from the surplus product to be exchanged with departments II of the other sectors. If we take the same proportion of exchange of that fund with department II of the state sector on the one hand and with the private economy on the other, as we did with Iv—that is, if we assume that two-thirds, or 467, goes to department II of the state sector, whereas the remaining 233 goes to private production—then the entire exchange fund of department I of the state sector that goes to replace half of IIc will be equal to 933.4 + 467 = 1,400.4 or, rounding off, 1,40G.12 However, the amount to be replaced was equal to 1,775. Thus, there is a deficit of means of production in the state sector to the tune of 375 million.

Let us go further. If we assume that this deficit is somehow covered, then all we need do is construct a scheme of expanded reproduction for the following year on the basis of the data of the initial scheme in order to see how the disproportion that we have noted will persist, decreasing somewhat under certain conditions, increasing under others. To be precise, of the 887.5 of surplus product in department II that is subject to accumulation, 295.8 will go to increase v, and 591.7 to increase c. Thus, IIc will now equal 4,141.7, whereas the part of it that must be covered by exchange with department I will be equal to 2,070.8. At the same time, as a result of the growth of v and of nonproductive consumption, the exchange fund of department I increases proportionately, and the part of it that must go to replace IIc will now be 1,680 instead of 1,400. This means that in the following year the deficit of means of production will equal 2,070.8-1,680 = 390.8 million instead of 375—with the same rate of growth of nonproductive consumption.13 Conversely, maintenance of the same absolute volume of nonproductive consumption must necessarily increase the disproportion because maintenance of the old volume, or a reduction of the rate of growth of nonproductive consumption, will cause a depletion of the exchange fund of department I of the state sector at the same time that IIc of the state sector is growing in relative terms.14 The question arises whether the disproportion that we have discovered is the result of the numerical relationships we have chosen as an illustration (although the proportions are close to the actual ones) or whether it represents a real disproportion in our economy.

There can be hardly any doubt that the example we have chosen illustrates precisely the real disproportion that exists in our economy and that is caused by (1) the suspension of foreign capital investment in our industry; (2) the reduction of the nonproductive consumption of the bourgeois class; (3) the failure to make up for depreciation losses on fixed capital in previous years; (4) the withdrawal of a part of the means of production for the construction of new plants that have not yet begun to yield any output; (5) the general necessity of more rapid accumulation in department I during a period when the country is undergoing industrialization.15

Thus, we observe a sharp and continuously growing deficit of means of production in our state economy. The question now arises: What role in eliminating this disproportion can be played by foreign trade, which we must now introduce into our analysis? This role is an extremely important one. Let us assume that the deficit of means of production in department II signifies a deficit of machinery for light industry, the electric power industry, the basic chemical industry, and so on, and that the deficit in heavy industry expresses itself in a shortage of equipment in the fuel industry, in engineering plants, high-power turbogenerators, air compressors, and other equipment of ferrous and nonferrous metallurgy. What is the effect of introducing foreign trade?

The introduction of imports achieves the following:

(1) Light industry will not be arrested in its development and will not have to wait for the moment when department I can, on the basis of its own development, provide it with the elements of c that are in short supply. Instead, it can cover its deficit immediately from abroad. That is, the problem of time is solved. In contrast, trying to solve the problem by the long, roundabout way of developing our own department I would lead to a growing crisis and to one difficulty piling up on top of another, including those in the area of exchange between the state sector and private production. In this connection we must keep in mind another extremely important circumstance: To increase its output by 100 units, light industry must expend its constant capital correspondingly—in the present case the part of c that is reproduced in department I of the state sector. But if in that department there happens to be a general deficit of means of production required by light industry, then the additional demand of light industry can be satisfied only by constructing new enterprises in heavy industry. This construction, however, necessitates each year the withdrawal—for the entire construction period—of resources from the general accumulation fund of the state economy that far exceed the value of the means of production needed to supply light industry with additional elements of fixed capital. The addition of a new 100c to the constant capital of department II may require a simultaneous investment of 400 to 500 in new capital in department I. Yet, if we turn to the world market we can solve this problem, directly and without delay, by importing the necessary amount and type of means of production for department II.

(2) Heavy industry will not have to wait until its own deficit of means of production is covered by its internal development, nor will it have to equip new industries with machinery of its own production, which would mean an extreme delay in putting new enterprises into opeartion and lead to a crisis within department I itself, as well as in its exchange relations with department II. Instead, heavy industry can cut through the contradictions by importing equipment that, if produced domestically, would intensify the crisis by channeling an already inadequate accumulation into enterprises whose construction is hardly of primary importance as long as we have links with the world economy.

(3) Both light and heavy industry solve not only the temporal problem of developing their production, but also, to a certain extent, the problem of accumulation at the expense of the private economy. Let us illustrate this concretely. In our example, the state sector has a shortage of 400 million rubles, calculated in domestic prices, in means of production for replacing fixed capital. To cover this deficit, our state has only to export, let us say, consumer goods from the peasant economy for 200 million rubles or $100 million and buy foreign equipment for that same sum. This foreign equipment, which in world prices costs $ 100 million or 200 million chervonets rubles, costs 400 million rubles inside our country, if we consider the difference between our domestic industrial prices and foreign prices. Thus, thanks to the import of means of production, we profit by the difference between world prices and domestic prices and automatically accumulate fixed capital in our developing industry.

Thus, the link with the world market, which solves the temporal aspect of the problem of reconstruction and expansion of fixed capital of both departments in the state sector, also solves to a certain degree the material aspect of the problem of accumulation, specifically, by methods of primitive socialist accumulation.

In addition to the case we have just examined, however, there is another disproportion that can also be solved by imports. This involves replacing a certain part of the elements of IIc in their material form, since our own domestic production of raw materials is insufficient in certain areas. We would probably retard the normal development of our textile industry by a decade if we were to wait for our own cotton production to develop to the point where it could satisfy the entire demand of this industry for raw materials.

In addition to the cases we have just listed, reliance on imports is an absolute necessity in cases where, for natural reasons, we simply do not produce a particular raw material (for example, natural rubber) or certain means of consumption (for example, coffee). But I deliberately avoid going into that aspect of our link with the world economy, because in that case participation in the world division of labor is advantageous and necessary for us in general, regardless of the structure of the economy and the degree of its development. Rather, I am speaking of the import of those means of production that we can, in general, produce ourselves and whose domestic production we will in fact expand, but which, at the present stage of the state economy's development, we have to import—first to maintain equilibrium in the system of expanded socialist reproduction, and second to promote the accumulation of fixed capital.

Thus we arrive at the conclusion that the third precondition for equilibrium in our system is the closest possible link with the world economy, built upon the very distinctive nature of our exports and imports. When there is a general deficit of domestic production of means of production, in particular, when heavy industry is underdeveloped relative to the demands of the domestic state and private market and relative to the overall rate of industrialization necessary for the country, our planned import of means of production must he of such a volume and material composition as to serve, so to speak, as an automatic regulator of the entire process of expanded reproduction without ceasing to be a source of accumulation. *