1

Introduction

Success is not final, failure is not fatal: it is the courage to continue that counts.

Winston Churchill

This book arose as a result of my fascination with computers and programming with the C++ language. It is also a result of my over 20 years of teaching the basics of computer science and particularly the C++ language to the students of the faculties of electrical engineering as well as mechanical engineering and robotics at AGH University of Science and Technology in Krakow, Poland. I have also worked as a programmer and consultant to several companies, becoming a senior software engineer and software designer, and have led groups of programmers and served as a teacher for younger colleagues.

Learning programming with a computer language is and should be fun, but learning it well can be difficult. Teaching C++ is also much more challenging than it was a decade ago. The language has grown up significantly and provided new exciting features, which we would like to understand and use to increase our productivity. As of the time of writing, C++20 will be released soon. In the book, we use many features of C++17, as well as show some of C++20. On the other hand, in many cases, it is also good to know at least some of the old features as well, since these are ubiquitous in many software projects, libraries, frameworks, etc. For example, once I was working on a C++ project for video processing. While adjusting one of the versions of the JPEG IO libraries, I discovered memory leaks. Although the whole project was in modern C++, I had to chase a bug in the old C code. It took me a while, but then I was able to fix the problem quickly.

The next problem is that the code we encounter in our daily work is different than what we learn from our courses. Why? There are many reasons. One is legacy code, which is just a different way of saying that the process of writing code usually is long and carries on for years. Moreover, even small projects tend to become large, and they can become huge after years of development. Also, the code is written by different programmers having different levels of understanding, as well as different levels of experience and senses of humor. For example, one of my programmer colleagues started each of his new sources with a poem. As a result, programmers must not only understand, maintain, and debug software as it is, but sometimes also read poems. This is what creates a discrepancy between the nice, polished code snippets presented in classes as compared to “real stuff.” What skills are necessary to become a successful programmer, then?

Why did I write this book, when there are so many programming Internet sites, discussion lists, special interest groups, code examples, and online books devoted to software development? Although all of these frequently are great and highly useful as instant references, it is sometimes difficult to find places or sources that lead us step-by-step through the learning process. It is even more difficult to find good examples that teach key programming techniques and at the same time are short, practical, and meaningful. So, I would like to share with you the synergy of theory descriptions underpinned with project examples that I have collected during my years of programming and teaching.

Let us now look at a short overview of the main subject of this book. The C++ programming language is one of the most influential, commonly used, and fascinating languages, initially developed by Bjarne Stroustrup in the 1980s. In the last decade, it has undergone vast and fundamental changes. The roots of C++ are in the C and Simula programming languages (Stroustrup B., Evolving a language 2007) (Stroustrup B., The C++ Programming Language 2013). As we will see, basic constructions such as expressions and statements, for instance, are almost the same for the two. Also, for years, all C++ compilers have been able to swiftly compile C code. C is the language that greatly influenced our technological revolution, proving to be a key tool in the development of the highly influential Unix operating system, followed by all the other OSs, including Windows, Linux, and Android. Due to its multiplatform compatibility and light footprint, C is still used in embedded systems, field-programmable gate array (FPGA) devices, and graphics cards (graphics processing units GPUs), as well as in code acceleration on parallel platforms. There are also tons of libraries written with C and still in use, such as those with efficient numerical algorithms or for image processing, to name a few. Simula, on the other hand, was one of the first languages equipped with classes, and it fostered the methodology of object-oriented software development. This became a cornerstone of the majority of technological endeavors. Hence, paraphrasing, C++ inherited from these two: from C in public, and from Simula in private.

Although there are many programming languages, learning C++ is worth the effort, especially for people planning to work or already involved in any kind of computer programming, especially for systems and performance. To grasp the main features of C++, it is sufficient to read this book; we will explore them in depth. However, as an introduction here, let us briefly list the most characteristic ones, as follows.

- Programmer freedom and wealth of features – Both low-level and highly abstract constructions can be used in many contexts. As with a Swiss army knife, there is a danger of misuse, but freedom and a wealth of features lead to the highest productivity level in various contexts and broad applications. But most of all – freedom is what we love

- High performance – This has always been a primary goal of the language. The key point in this respect is to be able to adjust many programming features to a particular need without much overhead. C++ was designed to meet this requirement – it can be paraphrased as “Don't pay for what you don't use.” As always, there is a price to pay, though, such as uninitialized variables and un-released resources. However, the new features of modern C++ make these less severe, still placing C++ code in the top-performing league

- System low-level and high-levelobject-oriented programming (OOP) on the same platform – C++ has been used to implement systems requiring low-level access. Many times, C++ is used to construct bridges between other languages: for example, in a numerical domain, to Fortran; and in systems programming, to C and Assembly. On the other hand, the same language has been used to implement high-level applications, such as word processors, CAD platforms, databases, and games. C++ is a strongly object-oriented (OO) language, fulfilling all the OO paradigms such as abstraction, encapsulation, inheritance, polymorphism, operator overloading, etc. These features, augmented with templates and design patterns, constitute strong support in software development, especially for large systems

- Strongly typed language – Each object is characterized by its type. This strong type requirement leads to code that is verified by a compiler, not by a user at runtime, as is the case with some languages that do not possess this feature. Nevertheless, objects can be converted from a type to another type due to built-in or user-provided conversion operators. Also, the relatively new type-deduction mechanism with the

autokeyword has greatly simplified the use of types and simply lets us save on typing - Exception handling – How to handle computational problems at runtime has always been a question. For example, what should be done in code if a file with crucial settings cannot be opened, or a division by zero is encountered? The solid exception handling system, with a built-in stack unwinding mechanism, greatly facilitates management in such situations

- Input-output (IO) – C++ was the first language that beat its competition in providing a clear, extensible, and highly efficient hierarchy of IO objects, as well as getting control over dozens of formatting styles and flags. This feature, although not without some limitations and criticism, can be used to add IO abilities to user-defined types in a fast and elegant way, with the help of overloaded operators

- Move semantics – One of the primary goals of C++ has always been performance. A large number of processed objects negatively affects this, especially if the objects are large and extensively copied. However, in many cases, object copying is not necessary, since data can be simply and efficiently swapped. This is the data-swapping mechanism behind the highly efficient move semantics available in modern C++, which have also increased the quality of the generated code

- Lambda expressions – This relatively new way of writing expression-like functions greatly improved the process of passing specialized actions or traits to algorithms. Together with

auto, lambdas lead to more elegant code and increased productivity - Smart pointers – Although smart pointers are among dozens of programming constructions from the Standard Library (SL), they changed the way C++ operates with system resources. For years, possible memory leaks that could easily happen in carelessly written C or C++ code were claimed as the main reasons against approving C++ code in high-security systems, as well as in network and web programming. Smart pointers impressively changed this picture – if consistently used, they can prevent memory leaks with no need for mechanisms such as memory garbage collectors, which negatively influence system performance

- Templates and generic programming – When writing massive code, it has been observed that many structures and functions repeat themselves, with almost the same arrangement and only a few types changed. Templates alleviate the problem of repeating code by allowing us to write functions and classes for which concrete types and parameters can differ and be provided just before such a construct needs to be instantiated. Because of this, code has become more generic, since it is possible to code components that can operate with various types – even those not known when the components are implemented. A good example is the

std.::vectorclass from the SL, representing a dynamically growing array of objects; it is able to store almost any object that can be automatically initialized - Libraries – The SL has dozens of data containers, algorithms, and sub-libraries for regular expression search, parallel programming, filesystems, and clock and time measurements. There are also other high-performance libraries for computations, graphics, game programming, image processing and computer vision, machine learning and artificial intelligence, sound processing, and other utilities. This resource frequently comes with an open-access policy

- Automatic code generation by a compiler – This also touches on metaprogramming and is due to the recent constant-expression mechanism, which allows us to compile, and execute parts of code in order to enter the results of these operations into the destination code

- Rich programming toolchain – This includes compilers, linkers, profilers, project generators, versioning tools, repositories, editors, integrated development environment (IDE) platforms, code analysis tools, software design CADs, and many more

This is just a brief overview of the characteristics of the C++ language. In many discussions, it is said that the price we pay for all these features is language complexity, which also makes the learning curve relatively steep. That can be true, but let us remember that we do not need to learn everything at the same time. That is, paraphrasing Oprah Winfrey, when you learn C++ features, “You can have it all. Just not all at once.”

You may have also heard of the 80/20 rule, also called the Pareto principle. It says that 80% of the CPU time will be spent on 20% of the code, or that 80% of errors are caused by 20% of the code, and so on. The point is to recognize that the majority of things in life are not distributed evenly, and usually 20% of the effort will be responsible for 80% of the effect. With respect to learning C++, my impression is that, to some extent, we can apply the Pareto principle. The goal of the first two chapters of this book is just to provide the necessary basics. How many programs can be written with this knowledge? Hopefully, many. However, this does not mean the rest of the book is not important. On the contrary, the introductory parts give us a solid foundation, but the more advanced features provide the top gears we need to take full advantage of C++ and to become professional software designers and programmers. How do we achieve these goals? As in many other disciplines, the answer is practice, practice, and practice! I hope the book will help with this process.

Here are some key features of the book.

- The goal is to present the basics of computer science, such as elementary algorithms and data structures, together with the basics of the modern C++ language. For instance, various search algorithms, matrix multiplication, finding the numerical roots of functions, and efficient compensated summation algorithms are presented with C++ code. Also, the basic vector and string data structures, as well as stacks, lists, and trees are described with C++ code examples

- Special stress is laid on learning by examples. Good examples are the key to understanding programming and C++. However, the most interesting real cases usually happen in complicated production code that frequently contains thousands of lines and was written by different people during years of work. It is barely possible to discuss such code in a book of limited size, aimed at students. So, the key is the nontrivial, practical code examples, which sometimes come from real projects and are always written to exemplify the subjects being taught

- Regarding the editorial style, the goal was to use figures, summaries, and tables, rather than pages of pure text, although text is also provided to explain the code in sufficient detail. The tables with summaries of key programming topics, such as C++ statements, operators, the filesystem library, SL algorithms, etc. should serve as useful references in daily programming work

- Basic containers and algorithms of the C++ SL are emphasized and described, together with their recent parallel implementations

- Special stress is laid on understanding the proper stages of software construction, starting with problem analysis and followed by implementation and testing. It is also important to understand software in its execution context on a modern computer. Although the top-down approach is always presented, topics such as the organization of code and data in computer memory, as well as the influence of multi-core processor architectures with layered cache memories, are also discussed

- Software construction with object-oriented design and programming (OOD, OOP) methodologies is emphasized

- The methodology and key diagrams of the Unified Modeling Language (UML) are explained and used

- Some of the most common and practical design patterns, such as the handle-body and adapter, are presented in real applications

- We do not shy away from presenting older techniques and libraries that may still be encountered in university courses on operating systems or embedded electronics, as well as in legacy code. For this purpose, a self-contained section in the Appendix provides a brief introduction to the C programming language, as well as to the preprocessor, as always with examples

- A separate chapter is provided with an introduction to the various number representations and computer arithmetic, with a basic introduction to the domain of floating-point computations and numerical algorithms. This information will be useful at different levels of learning computer science

- The software development ecosystem, with special attention devoted to software testing and practical usage of tools in software development, is presented with examples

- The chapters are organized to be self-contained and can be read separately. However, they are also in order, so the whole book can be read chapter by chapter

The book is intended for undergraduate and graduate students taking their first steps in computer science with the C++ programming language, as well as those who already have some programming experience but want to advance their skills. It is best suited for programming classes for students of electrical engineering and computer science, as well as similar subjects such as mechanical engineering, mechatronics, robotics, physics, mathematics, etc. However, the book can also be used by students of other subjects, as well as by programmers who want to advance their skills in modern C++. The prerequisites to use the book are modest, as follows:

- A basic introduction to programming would be beneficial

- Mathematics at the high school level

The book can be used in a number of scenarios. As a whole, it best fits three or four semesters of linked courses providing an introduction to programming, OOP, and the C++ programming language in particular, as well as classes on advanced programming methods and techniques. The book can also be used in courses on operating systems and embedded systems programming, and it can serve as supplementary reading for courses on computer vision and image processing. This is how we use it at the AGH University of Science and Technology.

On the other hand, each chapter can be approached and read separately. And after being used as a tutorial, thanks to its ample summaries, tables, figures, and index, the book can be used as a reference manual for practitioners and students.

1.1 Structure of the Book

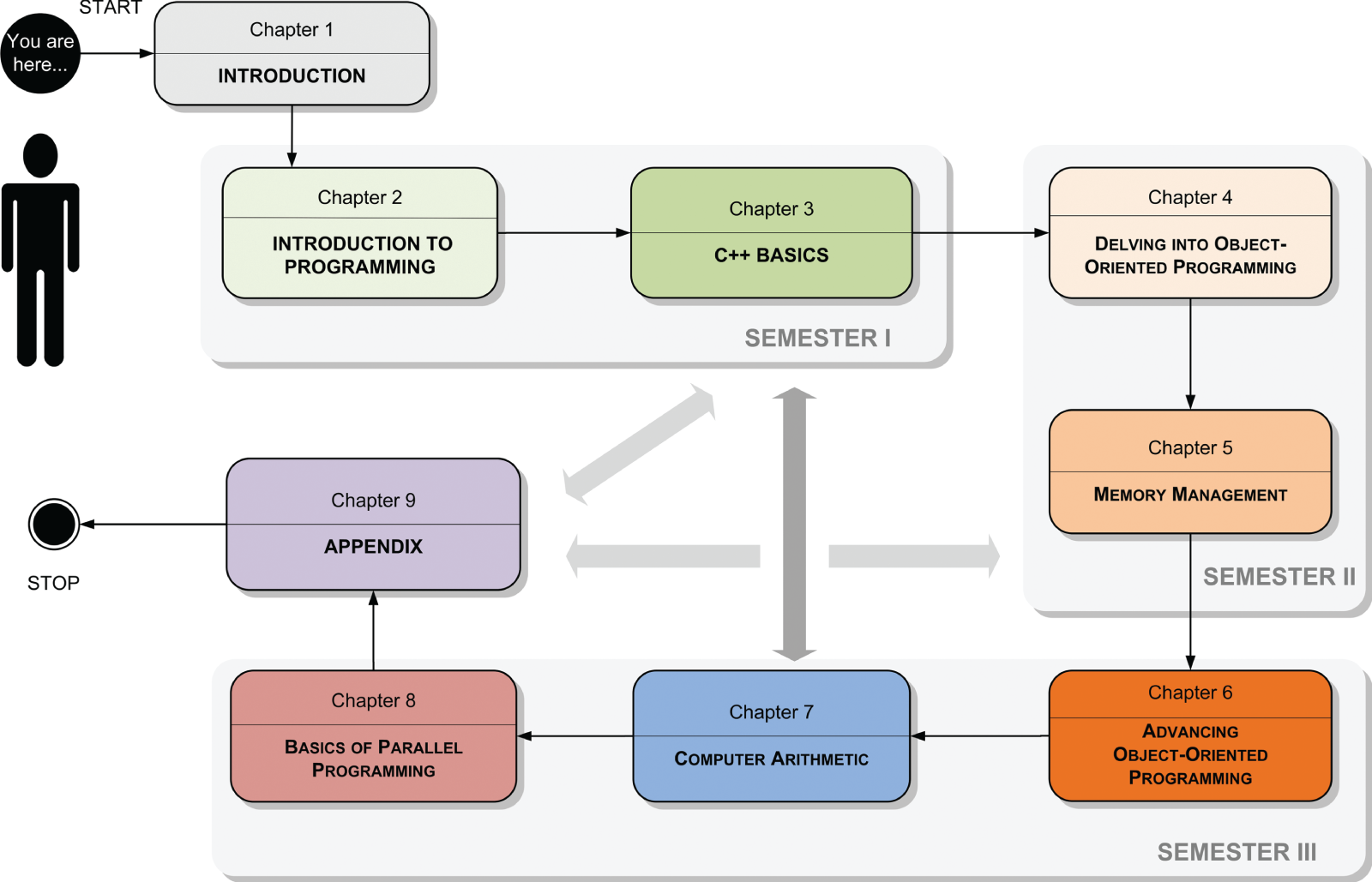

The diagram in Figure 1.1 shows the organization of the book and possible paths for reading it. The following list describes the contents of the chapters:

- Chapter 2: “Introduction to Programming” – A basic introduction to programming. We start by presenting the hardware model, which is useful to understand what computer programs do. Then, the goal is to present the C++ development ecosystem, available online compilers, and integrated development environment (IDE) platforms, followed by three example projects, mostly focused on computations in a single

mainfunction with a very limited set of statements and operators. The ubiquitousstd::coutandstd::cinobjects from the SL, representing output to the screen and input from the keyboard, respectively, are presented. In the last example,std.::vectorandstd.::stringare introduced, for a dynamic array and a text string representation, respectively. Although limited, the set of C++ mechanisms introduced in this section allows us to write a fairly large group of simple programs

Figure 1.1 The structure of the book, shown as a state diagram in Unified Modeling Language (UML). Chapters 2 and 3 introduce the subject. The advanced level is built from Chapters 4, 5, and 6. These are followed by Chapter 7, on computer arithmetic, and Chapter 8, dealing with parallel programming. The Appendix can be referred to from each of the previous chapters.

- Chapter 3: “C++ Basics” – Provides a solid introduction to the basic but very important features of programming with C++. First, the built-in data types and their initialization methods are discussed. Then,

std::vectorandstd::stringare approached again, with a greater degree of detail. The following sections present theautokeyword, an introduction to some SL algorithms, structures and classes, fixed-size arrays withstd::array, references, pointers, statements, functions (including lambda functions), tuples withstd::tuple, and structured binding, as well as operators. Along with many small examples, three relatively simple but complete projects are presented: representation of matrices, a class to represent quadratic equations, and a project containing two custom classes for the representation and exchange of various currencies. The aim of the examples and this chapter is to teach how to properly create and use a single class with its data and function members - Chapter 4: “Delving into Object-Oriented Programming” – Leads to mastering intermediate and advanced techniques of C++ with special stress on OOD and OOP. After discussing the main paradigms of OOD and OOP, the anatomy of a class with access rules is presented. Then, operator overloading is introduced and immediately trained on an example class for representing complex numbers. After that, special class members are discussed, with such topics as shallow vs. deep copying, as well as the benefits of move semantics. An introduction to templates and generic programming follows, as always deeply underpinned with examples. After that, class relations are analyzed, followed by the presentation of class hierarchies and dynamic, as well as static, virtual mechanisms. The “has-a” vs. “is-a” relation is then analyzed, including some hints about when to use each one

- Chapter 5: “Memory Management” – Devoted to various aspects of object lifetime and scope, as well as to object creation, access, and disposal. The vast majority of this chapter is dedicated to smart pointers. Code examples are provided for constructing a list with shared smart pointers, as well as the factory design pattern

- Chapter 6: “Advanced Object-Oriented Programming” – Presents a few additional, highly practical programming techniques and methods. The aim is to practice the methods presented in the previous chapters, as well as to become acquainted with functional objects, pattern matching with regular expressions, implementation of the state machine and the handle-body design pattern, filesystem, system clock and time measurement, ranges, and the user interface. Also, such programming techniques as expression parsing, tree building, and traversing with the visitor design pattern are presented, as well as interpreting expressions with the interpreter design pattern

- Chapter 7: “Computer Arithmetic” – This chapter is divided into two subsections devoted to fixed-point and floating-point numbers, respectively. It starts with very basic information about computer arithmetic, such as byte interpretation, systems conversions, etc. So, it can also be used as an introductory lesson after Chapter 2. However, it includes much more than simple computations. We delve into important topics such as roundoff errors, catastrophic cancelation, and the IEEE 754 floating-point standard. We also investigate some advanced programming techniques, e.g. when a compiler can generate code during compilation, as well as how to compute function approximations and how to properly sum up buffers with big data

- Chapter 8: “Basics of Parallel Programming” – Enters the realm of parallel computations. First, new phenomena are explained associated with the concurrent operation of many cores at once and accessing shared objects. Then, we present and test three software components for parallel computations. The simplest calls a parallel version of the algorithms from the SL. However, C++ contains a separate library that allows parallel computing – in this respect, asynchronous tasks are presented. The last is the OpenMP library. With it, we test how to write parallel sections, how to parallelize

forloops, and how to measure execution time with examples of matrix multiplication - Appendix – Presents different programming topics. We start with a short presentation of the preprocessor, followed by a brief introduction to the C language. Although learning C++ does not require prior knowledge of C, the latter helps with understanding some features of the former. For example, the parameters of the

mainfunction, simple arrays, unions, and C-like string representations are encountered in daily programming life. Other topics, such as linking and binary organization of C/C++ programs, graphical user interfaces (GUIs) available to C++ programs, software testing, and a programming toolchain composed of CMake, Git, and GitHub, as well as the Profiler, are also presented

As already mentioned, the book does not need to be read linearly. The chapters are organized in such a way as to facilitate their separate use. The book's Appendix and many summaries and references can also be used independently when working on the code projects.

In addition, it is important to realize that presenting highly detailed programming topics in a linear fashion is basically impossible. Therefore, some constructions, although used in a given context, may not be well understood on first reading but are explained in later sections.

1.2 Format Conventions

For easier navigation, a few different formats are used in this book, as follows:

- Bullets are used at the beginning and end of some sections to present key programming constructs and/or techniques that will be introduced in that section

- C++ code is written using color to emphasize different language categories. It is then presented on a light blue background and with numbered lines, as in the following example

The output in the terminal window (also known as the console or command line) is then presented, also on a color background, as follows:

Code on a white background is either older legacy code in C, such as that presented in Appendix A.2, or code that for some reason is not recommended to be used in C++ but is shown as part of the explanation of some phenomenon. This way, we can easily distinguish between the two types of code.

At the beginning of each code snippet is a caption, such as Listing 1.1 in the previous example. It describes the intention of the code and – if the code comes from one of the project files – includes the name of the file containing this code, in parentheses and written in italics, such as main.cpp. For better readability, long sections of code are frequently split into a number of shorter code snippets. In such cases, a caption is included only once, above the first snippet, and the line numbering continues until the end of the entire code component.

- The lines are numbered in most of the code listings. These numbers are then referred to using square braces []. For example, in Listing 1.1, the standard iostream header is included in line [1], the

mainfunction is defined in lines [3–8], and lines [5, 6] contain comments, which in C++ start with double slashes//. To emphasize the importance of the latter, comments are in red - Code such as the

std::coutobject, which represents a screen, is written with a special monospaced font. On the other hand, file names – such as iostream and main.cpp – are in an italic font - Many functions and objects are presented that belong to the Standard Library. These can be easily distinguished by the

std::prefix, as we have already seen. However, the prefix can be omitted as for exampleendlif theusing std::endl(meaning “end-of-line”) directive is placed at the top of the code. Hence, two versions are used in the presented code, depending mostly on the context, but also on the available space - There are two types of sections:

- Sections presenting new material

- Example project sections, built around self-contained projects with the goal of practicing specific programming techniques

- Sections that contain additional or advanced material, but do not necessarily need to be read immediately in the current presentation context, are marked with

- The ends of sections with important material frequently have a “Things to Remember” list, as follows

- To represent algorithms in pseudo-code, the following format is used

- There are two types of references:

- Chapters end with “Question & Exercise” sections (Q&E), which usually contain extensions to the presented techniques

- If special keys are mentioned, they are indicated, such as

Ctrl+Alt+T(which opens a terminal window in Linux)

1.3 About the Code and Projects

As alluded to previously, the book contains dozens of code examples. The learning process relies on making the code run and understanding why and what it does. So, here are some hints on how to use the code:

- All of the code is available online from the GitHub repository (https://github.com/BogCyg/BookCpp). A short intro to GitHub is in Section A.6.2

- Although the code can be easily copied, compiled, and executed, the best way to learn programming skills is to write the code yourself. This can involve simple retyping or, better, after understanding the idea, attempting to write your own version. Once you have done so, try to make it run; and if you are not sure about something, refer to an example from the book. Then update your solution and try again

- The fastest way to compile the code and see what it does is to copy the code (only the code, not the formatting characters or line numbers) to one of the online compilation systems – more on this in Section 2.4.2. This works well, but only for relatively small projects. Also, online platforms have some limitations with regard to input and output actions, such as writing to a file, for example

- For larger projects, a recommended approach is to build the project yourself on your computer with your programming tools. To do this, two things are necessary: a relatively new C++ building environment, such as an IDE, as presented in Sections 2.4 and 2.5; as well as the CMake tool, described in Appendix A.6.1. Although the projects can be built locally with only an IDE, CMake greatly facilitates this process, considering many operating systems, programming platforms, tools, source versions, etc. It is also a de facto industry standard that is good to know. In addition, some IDEs include CMake

- Since software constantly evolves, there may be differences between the code in the book and the code in the repository. Therefore, for an explanation of programming techniques and C++ features, the code from the book should be referenced. However, to build an up-to-date version of a project, the code from the repository should be used

Modern C++ compilers are masterpieces. For instance, prior to the construction of the complete executable, a modern compiler can even precompile parts of the code; these can be then immediately executed by the compiler to compute any results obtainable at this stage, which can be then directly put into the final code to avoid computations at runtime. We will also discuss how to benefit from these features. However, if something is incorrect and the code does not compile, sometimes it is not easy to figure out the cause and, more important, how to solve it. A compiler tries to tell us precisely what is wrong. But because errors can happen everywhere and at different levels, an error message can be a real mystery. Compilers are still far from being able to tell us exactly how to get out of trouble. Maybe AI will bring new possibilities in this area. At the moment, such language features as concepts in C++20 are available. As always, some experience and contact with worldwide programming colleagues are the best resources to help.

So, what do we do if code does not compile? – Here are some hints for beginners:

- First of all, do not write long sections of code without checking whether it compiles. A much better approach is to organize your code, if possible, even in a slightly nonlinear way: e.g. write an empty function with only parameters provided, and then compile. Then write a few lines, also nonlinearly (e.g. an empty loop), and see if it compiles. Add more lines, compile, and so on. At each stage, check for errors; if they appear, modify the code to make it compile

- When you encounter compilation (or linker) errors, always scroll the error pane to the top and check only the first error. Frequently, the rest of the errors are just the result of the compiler stumbling on the first one

- Carefully read each error message. If necessary, copy it to an editor and split it into parts so you can understand it better. Error messages include codes, so you can always look them up on the Internet by citing such a code: for example, “

error C2628: 'MonthDays' followed by 'void' is illegal (did you forget a ';'?).” Yes, indeed, I forgot the semicolon;just after a definition of theMonthDaysstructure. Adding the missing;fixes the problem in this case. But that was easy - Sometimes the cause of an error is a letter, line, function, etc. just a few lines before the erroneous line indicated by the compiler. If you stumble due to an error, try to verify a few lines before the indicated place

- Search for clues on the Internet. Pages such as http://stackoverflow.com, http://codeguru.com, etc. offer a lot of practical advice from skillful programmers. However, always check the date of a given post – there is a lot of outdated information on the Web as well!

- If a section of code persistently does not compile and you have no idea what's going on, disable it temporarily. This can be done either by commenting it out, i.e. placing

//in front of a line, or by enclosing the code with#if 0 temporarily_disabled_code #endifdirectives. If the rest compiles, then narrow the disabled area, and check again - Code can be written in many ways. For example, there are many types of loops; the

switch-casestatement can be written withif-else, etc. However, do not abandon non-compiling code before you find out and understand why it does not compile. It can take some time, but this way, you learn and avoid losing time in the future when you encounter a similar problem. Only after you understand what you did wrong should you consider using another or better language construction - Last but not least, consult your colleagues at college or working at the next desk, or ask your teacher – send them an e-mail, ask for advice, etc. It is always good to communicate