2

2

Chuci (lyrics of Chu) is a type of poetry that flourished in the Chu region during the Warring States period (403–227 B.C.E.). The poems were collected in the anthology Chuci zhangju (Commentary Edition of Chuci), edited by Wang Yi (fl. 114–119) of the Han dynasty. It contains nearly sixty poems, which can be divided into two groups. The first group is composed of the earlier poems, written and compiled, according to Wang Yi and other Chinese scholars, by Qu Yuan (340?–278 B.C.E.), a statesman and nobleman of the Chu state (it should be noted that there is a great deal of controversy regarding the authorship of these works). The second group consists of poems written by later poets (including Wang Yi himself) in imitation of the earlier works. The most significant poem in this anthology is “Lisao” (On Encountering Trouble), presumably composed by Qu Yuan. It represents the crowning achievement of the genre. Sao, the second character of its title, is often used to refer to the entire Chuci repertoire and any work written in the Chuci style.

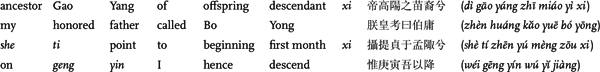

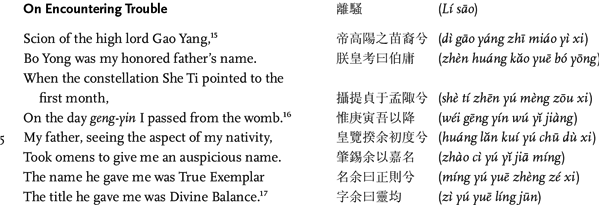

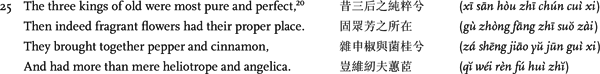

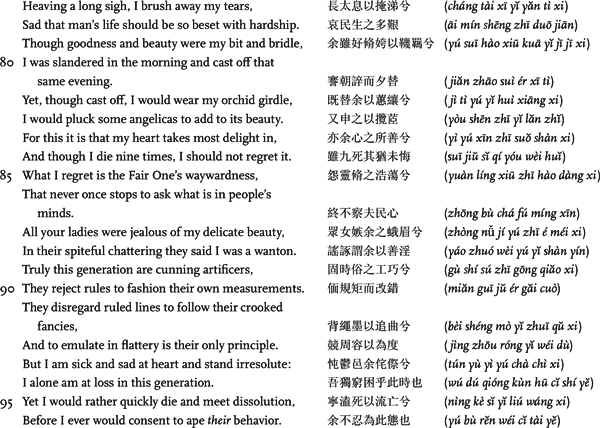

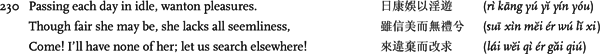

As a product of the Chu culture in the south, Chuci poems demonstrate considerable differences from those in the Shijing (The Book of Poetry), in both content and form. In content, the influence of shamanism is most remarkable, as many of the early poems in this genre, especially the “Jiuge” (Nine Songs), apparently portray its rituals and performances. This is even evident in many passages of “On Encountering Trouble,” a long narrative poem with a discernible and unprecedented autobiographical framework and voice. In form, Chuci poems adopt a format that is marked by longer lines than those in the Shijing. The following sample is from “On Encountering Trouble”:

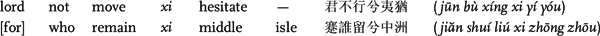

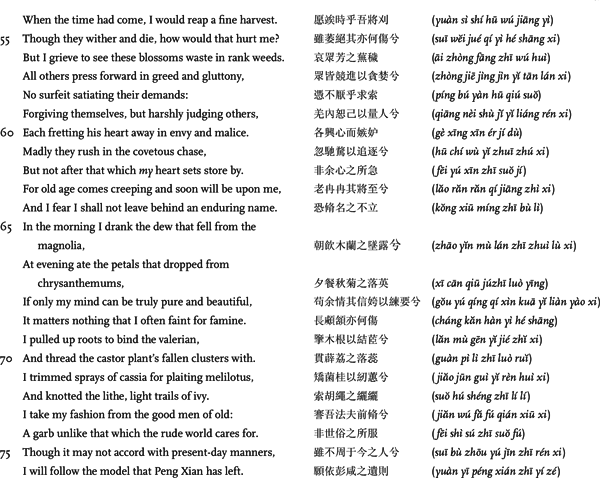

The length of these four lines alternates between six and seven characters. This is the dominant pattern in “On Encountering Trouble,” although there are quite a few exceptions. In other poems, however, the lines can be either shorter or longer. Another prominent formal feature in the Chuci is the use of the refrain word xi. Although this usage also occurs in the Shijing and other earlier texts, it was rather sporadic. In the Chuci, it became a constant, although its positions in the poems belonging to this genre also varies. In “On Encountering Trouble,” as evident in the example, it appears at the end of odd-numbered lines, but in the “Nine Songs,” it is placed within each line, as is illustrated by the following two lines from “Xiang jun” (The Lord of the Xiang River):

The function of xi is thought to be mostly musical, since as a word it does not have much meaning except to indicate a drawn-out sound similar to the a in modern Chinese. As in the poems of the Shijing and later periods, rhyming in the Chuci takes place in the last word of even-numbered lines. For example, the rhyming words in the earlier passage from “On Encountering Trouble” are yōng and jiàng, pronounced in archaic Chinese as λiwoŋ and γeuŋ, respectively. In some short poems, one rhyme is used throughout, but in “On Encountering Trouble,” the rhyme changes several times.

During the early Han dynasty, there was a tremendous interest in the Chuci, thanks to the dynasty’s early rulers, who came from the Chu region. Han Gaozu (r. 206–194 B.C.E.), the founding emperor of the Han, wrote his famous “Dafeng ge” (Song of the Great Wind) in Chuci meter. Han Wudi (r. 140–87 B.C.E.), another powerful monarch of the dynasty, was also a practitioner of the genre. Several princes of the royal family were actively involved in studying, editing, and composing Chuci poems. Liu An (179–122 B.C.E.), the prince of Huainan, for example, wrote the first commentary on “On Encountering Trouble.” Critical views of the Chuci varied from the early Han on. While most critics emphasized its continuity with the Shijing tradition and praised Qu Yuan for his steadfast loyalty to his state, others expressed uneasiness. Ban Gu (32–92), the author of the Han shu (History of the Han Dynasty), accused Qu Yuan of being arrogant and self-flaunting and of using a poetic language filled with “empty words” (xuwu zhi yu).1 Liu Xie (ca. 465–ca. 522), the author of the Wenxin diaolong (The Literary Mind and the Carving of Dragons), arguably the greatest work of literary criticism ever written in China, listed several features in “On Encountering Trouble” that conform to and stray from the classics and characterized it as “extraordinary writing” (qiwen). He also criticized Qu Yuan’s decision to commit suicide (for more on this, see the later discussion of “On Encountering Trouble”) as “narrow-minded.”2 Throughout Chinese literary history, though, the Chuci and its main hero, Qu Yuan, have proved to be an enduring presence and influence. In time, Qu Yuan became a national hero of China, and Shi-Sao (the Shijing and “Lisao,” the Chuci writ large) came to represent the very foundation of the Chinese poetic tradition.

This chapter presents two poems from the “Nine Songs” and an excerpted version of “On Encountering Trouble.”3

The “Nine Songs” are generally believed to be songs that were performed at shamanistic rituals. There are in fact eleven songs in this group, and with the exception of two, each is dedicated to a particular deity. They are thought to have been compiled and polished by Qu Yuan. The state of Chu, situated along the Yangtze River in southern China, was known for its shamanistic practices. Ban Gu once observed that the people of Chu “believe in the power of shamans and spirits and are much addicted to lewd religious rites.”4 The Chinese word for “shaman,” wu, originally referred to someone who could summon gods and spirits through dancing and singing. One of the essential qualities that shamans claimed to possess was the ability to communicate with these supernatural beings. Shamans also maintained that they often had to leave their physical bodies to meet with such beings, either above in heaven or down on earth. Thus a journey or flight is a recurrent motif in the “Nine Songs” and, to a lesser extent, in “On Encountering Trouble.”

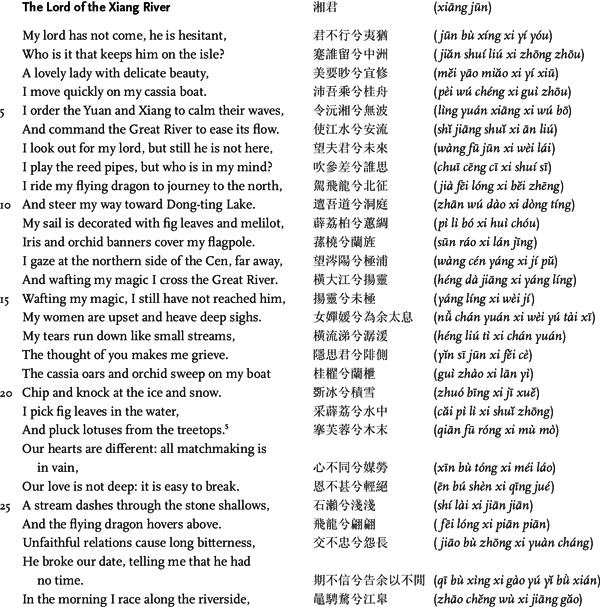

[CCBZ, 59–64]

As I have indicated, many uncertainties and ambiguities characterize the “Nine Songs.” In this poem, one of the most beautiful in the group, these uncertainties and ambiguities start from its title. Since the Chinese word jun is ambivalent in its indication of gender, the poem may be read as addressing either a male or a female deity. Here I have adopted the opinion that this poem and the next, “The Lady of the Xiang River,” form a dialogic exchange between the two deities of the Xiang River, the largest river in the Chu region. As parts of a shamanistic ritual, they were spoken and performed respectively by a female (in “The Lord of the Xiang River”) and a male (in “The Lady of the Xiang River”) shaman in search of each other.6

Several important features of this poem were further developed by Qu Yuan in “On Encountering Trouble.” First of all, the central motif of the poem is a love quest. The quest is conducted in a peculiarly shamanistic style: the protagonist rides on supernatural creatures, crosses between heaven and earth, and commands the natural world to be at her service. The quest, however, fails because her lord breaks his promise.7 This failure produces a profound melancholy that informs the entire verse. It also causes a temporary estrangement from her lover-deity; yet, despite all the disappointment, she remains loyal to him in the end. As we shall see, Qu Yuan appropriated this motif in “On Encountering Trouble” and made it into the central metaphor of his relationship with his monarch and state. Also noteworthy is the use of floral imagery in this poem. Beautiful flowers and plants are important components of a shamanistic ritual; they represent the sincerity, beauty, and solemnity of a religious performance. In the hands of Qu Yuan, however, this feature was given a moral dimension; it became a vital part of his symbolism in “On Encountering Trouble.”

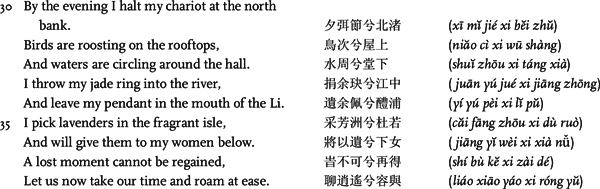

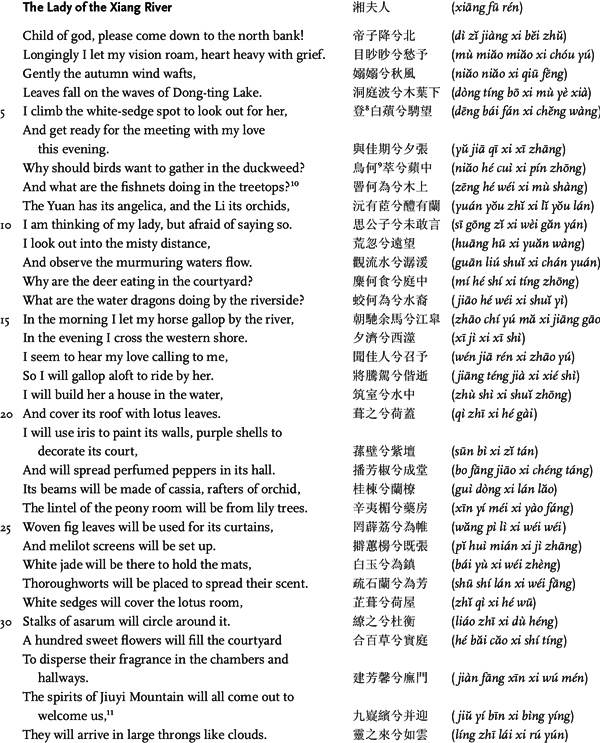

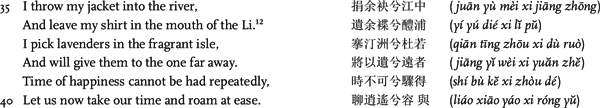

The companion piece, “The Lady of the Xiang River,” demonstrates many similar features. Its central motif is also the quest for a lover-deity. One noticeable difference is the section describing Dragon steeds, heavenly birds, the much-expanded floral imagery used to portray it (lines 19–32). Another similarity is that the last section of the verse (lines 35–40) is nearly identical to that of the “Lord of the Xiang River.” This has prompted some critics to claim that, unlike the main body of the two verses, which were performed by individual shamans, this part must have been sung by a choir.

[CCBZ, 64–68]

As I mentioned, in “On Encountering Trouble,” Qu Yuan appropriated some important features of these two poems, in particular their central motif of a love quest and floral imagery, and transforms them into an integral part of its symbolism. “On Encountering Trouble” is informed by an autobiographical voice that presumably belongs to Qu Yuan, and so, before turning our attention to this long poem, a brief consideration of his life will be useful.

Much of what we know about Qu Yuan is subject to controversy.13 According to his disputed biography in the Shiji (Records of the Grand Scribe), compiled by Sima Qian (145–86? B.C.E.), Qu Yuan was a member of the royal house of Chu and once served as a high minister under King Huai (Chu Huai Wang, d. 296 B.C.E.). He was a man of great learning and a talented statesman and diplomat. At first he enjoyed the trust of King Huai, but later, the king succumbed to the vicious slander and accusations against Qu Yuan from his political rivals at court. As a result, Qu Yuan fell out of favor. After the death of King Huai, his successor, King Qingxiang (Qingxiang Wang, r. 298–263 B.C.E.), continued the persecution of Qu Yuan and eventually banished him. Qu Yuan spent a few years in exile and finally drowned himself in the Miluo River.14

The most prominent feature of “On Encountering Trouble” is that it revolves around a poetic persona, whose experience and contemplation dominate and structure this otherwise convoluted poem. The persona integrates shamanism, ancient history, and events and philosophical ideas of Qu Yuan’s time to form a unique symbolism, one that serves as a powerful tool of self-expression.

This section is crucial in setting the tone for the entire poem. By informing the reader of his family background at the very start, the poet firmly establishes himself as the center of the poem. He is signaling to his audience that what follows will be about him, a noble descendant from a glorious clan in the state of Chu. This rhetorical gesture was unprecedented in Qu Yuan’s time (it later became common practice). Most of the poems in the Shijing are anonymous. In the few pieces where the author’s identity is indicated, none goes to such length to establish the poet as the center. For this reason, Qu Yuan has been called China’s first poet.18 Note that the first-person pronoun (zhen 朕, wu 吾, yu 余) is repeated six times in this eight-line excerpt. Such frequent use of the first-person pronoun in a very limited space is unusual in Chinese poetry, where the pronoun is often omitted. Qu Yuan is taking great pains to draw his audience’s attention to himself.

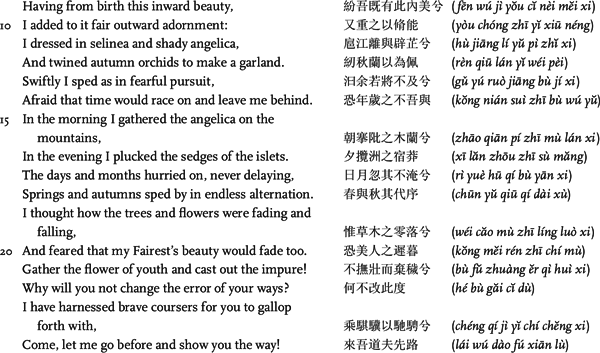

Having introduced his noble family background, Qu Yuan consolidates it in this section with his own moral cultivation. This is described in the context of the quick passage of time, the poignant sense of loss it causes the poet, and his inability to use his moral quality to serve his wrongheaded king.

This section introduces several motifs that are elaborated throughout the poem. The first, the most enduring trademark of the Chuci, is the trope or convention of “fragrant plants and fair one” (xiangcao meiren). Qu Yuan makes it clear that the selinea, autumn orchid, rare angelica, and other fragrant plants that he adorns himself with are for the purpose of complementing an “inward beauty,” thus establishing their symbolic significance. In other words, beautiful plants are objective correlatives of fine subjective qualities, and the act of gathering and applying them is meant to be understood as a symbol or metaphor for moral cultivation.

The interpretation of “Fairest” (meiren) has caused a lot of controversy. In ancient Chinese, the phrase is ambiguous in gender. Some scholars regard it as a reference to King Huai, while others maintain that it refers to the poet himself. On a textual level, both interpretations seem to work. This ambiguity is characteristic of the allegorical nature of “On Encountering Trouble” in that, like the “fragrant plants and fair one” in these stanzas, many of its sections clearly invite understanding at another level. Chinese critics have been eager to demonstrate the usage’s affiliations with the Shijing. They regard this rhetorical device as being identical with the bi-xing (compare and evoke) convention in the Shijing (chap. 1). Since the subject is important to our understanding of the allegorical and symbolic framework of the poem, it is necessary to consider the matter in some detail.

Bi (to compare) usually refers to an explicit comparison of two things or situations, and xing (to evoke) refers to an image or a situation that evokes certain associations in the reader’s mind. Both bi and xing relate to comparisons between two things, but the former is associated with the more obvious, whereas the latter is concerned with the subtler. The boundary between the two, however, is sometimes not clear-cut. In the Shijing, objects or situations are merely juxtaposed. Any connections between them are evoked by their proximity, and there is no attempt in the text to direct our interpretation in a certain way. In the preceding and other passages in “On Encountering Trouble,” however, the poet explicitly informs his audience that a certain object or situation is intended to be compared with another. If xing is the dominant trope in the Shijing, “On Encountering Trouble” presents bi as its central device.

Since early times, critics have identified this xiangcao meiren trope as the central symbolic device in “On Encountering Trouble” and have used it as a guide to their allegorical readings of the poem. Wang Yi, for example, claimed that “On Encountering Trouble” “draws on types to make comparisons. Thus fine birds and fragrant plants [are used to] equate loyalty and steadfastness, wicked creatures and foul objects [are used to] compare with slanderous and villainous people, and godly and fair ones [are used to] equate with the monarch…. Dragon steeds, heavenly birds, and phoenixes [are used to] represent gentlemen, and whirlwinds and clouds [are used to] refer to villains.”19 This method of symbolic presentation has had tremendous influences on both the creation and the interpretation of Chinese poetry.

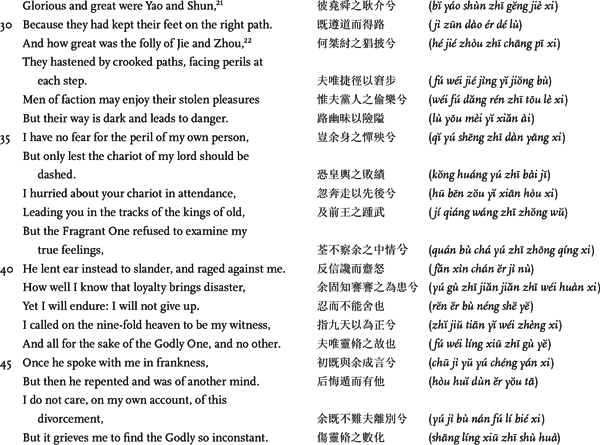

At the end of this section, the poet offers himself as a guide to “show the way” to his king. This prepares us for the numerous journeys on which the poet will take us throughout the poem in his quest for his ideals:

The poet, however, is denied the chance to guide his king because the king has “refused to examine [the poet’s] true feelings.” Not only that, he has “lent ear instead to slander, and raged against” the poet. In order to persuade his king to change his way, Qu Yuan looks back in history. He cites both positive and negative examples from the past so that his king may learn a lesson from them. Historical references such as these have found acceptance among critics. Liu Xie, for example, singled them out and praised their adherence to the classics. In this passage, the poet also provides some information about his relationship with King Huai, whom he addresses variously as the “Fragrant One” (quan) and “Godly One” (lingxiu). Quan is a kind of fragrant plant, and ling is often used to refer to matters related to a shaman or shamanism in the Chuci. As we shall see in the poem, Qu Yuan draws heavily on these two sources for his symbolism:

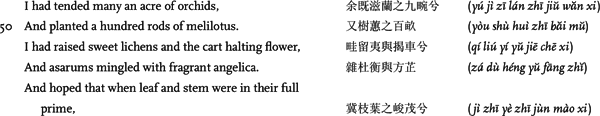

This section continues to develop the theme of moral cultivation in conjunction with the floral symbolism introduced earlier, but with a twist. The various flowers and plants mentioned in lines 49–52 seem to represent not only the poet himself but also his former comrades. Despite his constant efforts in “cultivating” them, most in the end failed him, making him “grieve to see these blossoms waste in rank weeds.” But the poet is undeterred by their shameful transformation and forges ahead with his good care of the fragrant flowers (lines 69–72). Lines 64 and 65 take up again the introduced motif of the quick, irrevocable passage of time, but this time the poet specifies for us the fear that it causes in him, which is that he may not be able to “leave behind an enduring name.” This reiterates his desire to “show the way” to his king and serve his state, which was regarded as one of the best means of passing one’s name down to posterity in ancient China. But then a few lines later, his alienation from the world around him causes him to ponder another radical alternative: to leave it behind altogether. The reference to Peng Xian in line 76 is ambiguous because of his duality as a historical figure and a shaman master. The dominant view, advanced by Wang Yi, is that Peng Xian was an upright minister during the Shang dynasty. When his loyal advice to his king was ignored, he drowned himself in protest. Another view is that he was a master shaman in the ancient past and that the reference to him indicates Qu Yuan’s desire to leave the world behind him by becoming a shaman. Qu Yuan’s reference to Peng Xian may be a signal to the reader that he, too, would commit suicide in protest, but the dual identity of Peng Xian illustrates the close link between the historical and shamanistic aspects of the poem. This will be further illustrated as we journey with the poet into the historical past and to the supernatural heavens.

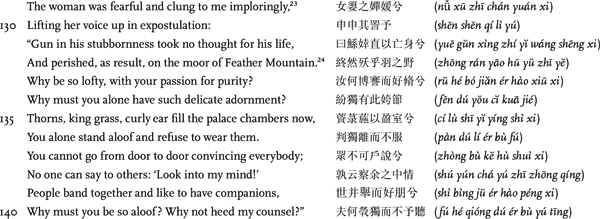

The couplet that begins this section (lines 77–78) conjures up the image of someone deeply saddened by the hardship of ordinary people. It is this image that has helped to make Qu Yuan into a national hero of China, whose long history has been filled with human suffering. In lines 87 and 88, the poet explicitly compares himself with a woman slandered by other women because of jealousy of her outstanding beauty. This is a further elaboration of the equation of beauty (represented by various flowers in earlier passages) with virtue. In Chinese culture, there is an ancient tradition of comparing a government minister with a wife: a minister is to a monarch as a wife is to a husband. Thus Qu Yuan’s deliberate twist of gender identity is not new. What is new is his effort to make this an integral part of his symbolism in general. Indeed, “On Encountering Trouble” demonstrates a keen interest in exploiting the ambiguities caused by dual identities. We have already seen this in the poet’s allusion to his king as both the “Fair One” and the “Godly One,” and in the historical and shamanistic dimensions of Peng Xian. We will see more such examples later in the poem.

In lines 97–128 (omitted), Qu Yuan continues to emphasize his alienation from society. He also repeats his determination to follow his principles and not to compromise his integrity, even though it means the sacrifice of his life. But in lines 111 and 112, Qu Yuan seems to indicate another, less radical solution to his dilemma. If he cannot help his king (jin [literally, to enter] is often used to refer to gaining a post in the government), he might as well retire (tui [to retire or withdraw]) so that he can pursue his love and cultivation of beauty and virtue—that is, become a recluse: “I could not go in to him for fear of meeting trouble, / And so, retired, I would once more fashion my former raiment” (lines 111–112).

Up to now, there has been little movement in the poem. What we have had so far is a long speech or monologue of the poet. Starting from this section, however, the poet becomes increasingly restless, trying to decide what step to take next. We find him

… halted, intending to turn back again—

To turn about my chariot and retrace my road

Before I had advanced too far along the path of folly. (lines 107–109)

At one point, he “suddenly turned back” to let his “eyes wander,” and “resolved to go and visit all the world’s quarters” (line 121). The text is signaling to us that more dramatic passages will follow.

This passage further develops and emphasizes one of the dominant themes of the poem: the poet’s alienation from society. However, inasmuch as it is cast in the form of a speech by a sympathetic woman, it allows us to see the alienation from another perspective. It demonstrates that it is not just his king and political enemies who do not understand him; even those who are clearly concerned with the poet’s well-being have misgivings about his principles. The woman’s advice for Qu Yuan to follow society’s tides is similar to that given to him by a fisherman, as recorded by Sima Qian in his biography of the poet. At another level, the introduction of a speech by another character briefly interrupts the poet’s lengthy monologue. It brings in a certain dramatic element and relieves the poem’s monotony. The woman’s speech attempts to bring about an exchange with the poet, but this potential does not materialize because, as we shall see, instead of answering the woman’s questions and concerns, the poet turns his attention elsewhere. The woman disappears from the poem.

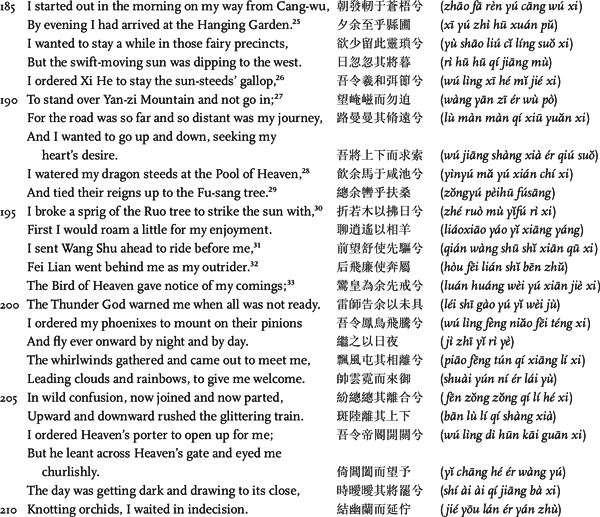

In the next section, lines 141–182 (omitted), the poet, as if aware of the difficulty of explaining his situation to a contemporary, takes his case directly to Shun, one of the most revered ancient sage-rulers. He tells Shun that, unlike in the past, when justice was rewarded and evil punished, his own time is thoroughly out of order. Then, the poet “yoked a team of jade dragons to a phoenix-figured car / And waited for the wind to come, to soar upon my journey” (lines 183–184). What follows is the poem’s first heavenly trip, one of the most fantastic sections in the poem:

As I have noted, spiritual and imaginary journeys (or “flights,” to use David Hawkes’s term) are essential components of shamanistic rituals. In order to seek help from the supernatural realm (in finding love, curing the sick, summoning back the dead, obtaining blessings of spirits, and so on), shamans often would engage in a performance and depart from their bodies to meet with the spirits. “The Lord of the Xiang River” and “The Lady of the Xiang River” describe such journeys. In fact, what we seem to have in this and other passages of “On Encountering Trouble” is further elaborations on those earlier models. Since, for whatever reason, these flights often end in frustration and melancholy, they have a thematic affinity with Qu Yuan’s poem—which is about “encountering trouble.” As we shall see, Qu Yuan takes advantage of this connection and uses it to accentuate his theme, which is his loneliness and total alienation from the world.

The rich style, fantastic imagery, and great imaginativeness of this section are unprecedented in the Chinese poetry of Qu Yuan’s time. They make the poems in the Shijing look sober and restrained in comparison. Many critics, such as Wang Yi, have tried to tame the poem and its special characteristics through allegorical readings. Others have found the poem’s style objectionable. Liu Xie, for example, accused such writing of being “outlandish” and regarded it as an “aberration from the classics.” However, this poem came to represent one of the Chuci’s most enduring influences and greatest contributions to Chinese poetry.

Undaunted by his failure to enter heaven, the poet continues his search, but now he is looking for something different:

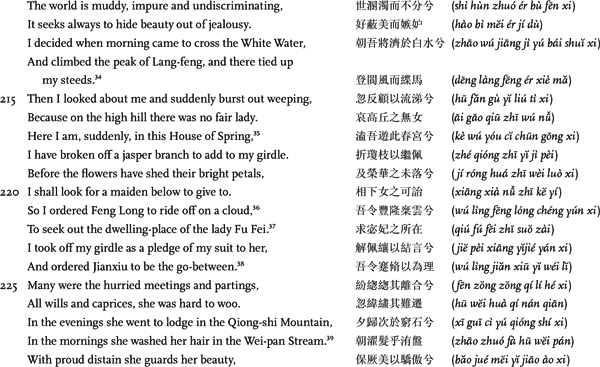

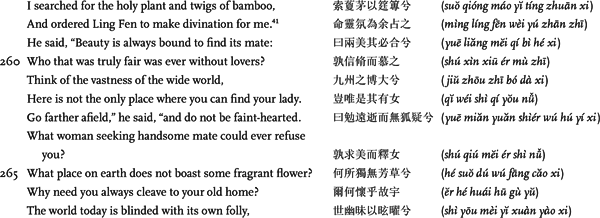

His frustrations in heaven make the poet return his attention to the world, but what a “muddy, impure” place he finds it to be! To escape it, he embarks on another journey, but this time the object of his search is Fu Fei, the beautiful goddess of the Luo River. His hoped-for result fails, however, because, despite all her beauty, Fu Fei turns out to be “wanton” and “lacks all seemliness.”

With the change of the search object in this section, the poem’s metaphor changes as well, and, with it, the speaker’s gender. Now the search is presented as a courtship, a man seeking his female mate. This reverses the gender relationship that the poet had with the “Godly One,” where he compared himself with a female of outstanding beauty slandered by jealous court ladies. This inevitably causes confusion in the allegorical framework of the poem and has generated much debate among commentators. The Song dynasty critic Zhu Xi (1130–1200) maintained that the women (Fu Fei and the other two women in the next section) “are divine women, and they therefore represent virtuous rulers.” But You Guoen and other modern scholars have regarded this and the following “courtship searches” as allegories of the poet’s efforts to find someone close to the king who could help to bring him back to the capital.40 Whatever the case may be, the gender relationships in the poem become increasingly complex. The complexity, though, does not seem to distract from the central motif of the poem: the poet is still searching for someone who shares his ideals.

In lines 233–256 (omitted), the poet continues his search for a “fair lady.” The object in this section is the “lovely daughter of the Lord of Song.” This search also fails because the poet finds “my pleader was weak and my matchmaker stupid” (line 249). At the end of this passage, Qu Yuan draws a parallel between these failed searches and his inability to wake up his “wise king.”

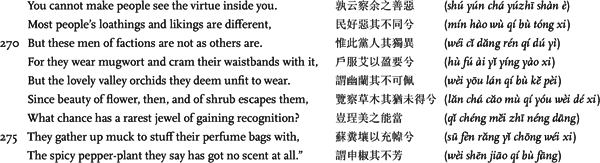

Somewhat baffled by his failures, the poet decides to seek help from divination:

Master Ling Fen’s oracle essentially repeats what Qu Yuan has been saying all along—that he possesses outstanding beauty, but this “blinded” world simply fails to appreciate it. The advice he offers is similar to that given by the woman earlier: he should not be too stubborn in the pursuit of his ideals, for if he is flexible in his mind, he will surely find what he wants. This flexible attitude, however, entails forgoing the poet’s loyalty to his monarch and his attachment to his “old home.” As we shall see, this is the ultimate sacrifice that the poet is unable to make.

It is noteworthy that Ling Fen’s criticism of the world is presented in floral images and metaphors similar to those that the poet has used in describing his differences from the rest of the world. He and Qu Yuan are nearly of the same mind, except for their different attitudes regarding one’s relation to the state. This again helps to emphasize the poet’s outstanding quality and the alienation it causes him.

In the next section, lines 277–332 (omitted), the poet, although desiring to follow Ling Fen’s words, “faltered and could not make up his mind” (line 277), so he seeks advice from Wu Xian, the master shaman. Wu Xian’s counsel essentially echoes that of the others: “As long as your soul within is beautiful, / What need have you of a matchmaker?” (lines 289–290). Wu Xian’s message is conveyed through several examples from ancient Chinese history. This combination of shamanism and history again blurs the boundary between the two.

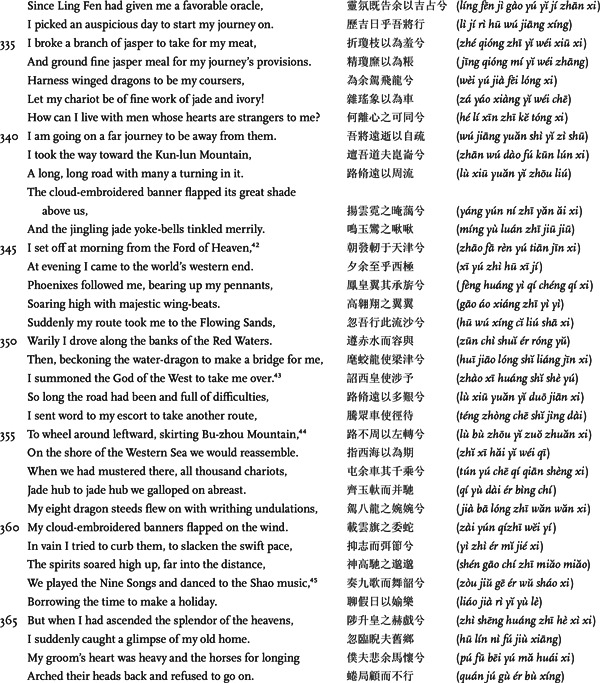

The counsels of Ling Fen and Wu Xian cause the poet to contemplate his life. What follows is a reflective passage that repeats the main themes and motifs introduced earlier: his steadfast pursuit of beauty and virtue and the rifts this pursuit has caused between him and the world, whose only aim is self-advancement. In this passage, the poet weaves yet another twist in his floral symbolism. Now, the beautiful and fragrant flowers are portrayed as undergoing transformations not from budding to blooming to fading, which would be natural, but from “fragrant plants” to “worthless mugwort”: “Why have all the fragrant flowers of days gone by / Now all transformed themselves into worthless mugwort?” (lines 309–310). It is evident that the poet is speaking metaphorically, and we are thus led to read this part of the text allegorically. Critics have interpreted this section as the poet’s deploring the shameful vacillations of his former comrades in their power struggles at court. Disillusioned, the poet finally decides to heed the counsels of Ling Fen and Wu Xian and to “travel around looking both high and low” for the “lady” who has eluded him in his previous journeys. This introduces the last shamanistic flight of the poem:

The purpose of this “far journey,” the poet informs us, is “to be away from” the blinded world and its benighted people. For a moment, the poet seems to have done just that. Pulled by his dragon steeds, accompanied by phoenixes and other supernatural creatures, the poet travels much farther this time, to the extreme far west of the world. At the peak of this dazzling journey, however, just as the poet “had ascended the splendor of the heavens,” he cannot but suddenly look down at his “old home.” This seemingly inadvertent act causes the sudden halt and subsequent collapse of this most fantastic “far journey.” Despite all the power and majesty, heavenly trips such as this pale in comparison with the poet’s mundane longing for his “old home.” Such supernatural flights are intended to transcend the world and its imperfections, but in the end, they serve to foreground the poet’s stubborn and powerful attachment to it. In other words, the splendid paraphernalia of shamanism are appropriated by the poet to promote a fundamentally humanistic theme, which is his profound engagement with the human world.

[CCBZ, 3–47]47

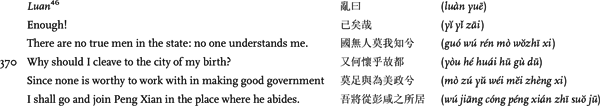

The last section, which is equivalent to a coda in a musical performance, sums up the theme of the poem. The poet reiterates his alienation from the world and states again his wish to “join Peng Xian in the place where he abides.” As indicated earlier, most critics regard this to be Qu Yuan’s statement of his intention to commit suicide, although some consider it to be the expression of his desire to become a shaman and spend the rest of his life as a recluse. It is important to note that what prompts this act is the poet’s realization that in this world “none is worthy to work with in making good government.” This situates the poem in the context of the human world. It also helps to “naturalize” or render normal the fantastic and unconventional elements of the poem, such as those inspired by shamanism and its rituals.

“On Encountering Trouble” is one of the longest poems in the Chinese poetic tradition, but, as we have seen, it is also repetitive in many of its sections. The repetitiveness of the text seems to serve a purpose, which is to stress the poet’s constant efforts to uphold his principles in the face of constant persecution by his enemies. It also helps to emphasize the difficult decisions that he had to make in a world he saw as unjust. Throughout Chinese history, many intellectuals often found themselves in similar situations. For those familiar with “On Encountering Trouble,” the poem portrayed an experience with which they could identify. Its beautiful language and dazzling journeys provided them with momentary relief from the pressing hardships of life. Qu Yuan’s railings against the injustice of the world offered them a means to vent their frustrations and anger, especially in later ages, when such relief often could be had only vicariously through a text. And, finally, Qu Yuan’s example demonstrated to them that virtue and beauty often go unappreciated, and that they were not alone in their misfortunes, thus making the sufferings of life more bearable. In sum, “On Encountering Trouble” provided both poetic inspiration and emotional catharsis to later generations. This has ensured it a major place in the history of Chinese literature.

NOTES

1. Quoted in Wang Yi and Hong Xingzu, eds., Chuci buzhu (Further Annotated Edition of the “Chuci”) (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1983), 49. Unless indicated otherwise, all citations of the Chuci are from this edition.

2. Fan Wenlan, ed., Wenxin diaolong zhu (Annotated Edition of “The Literary Mind and the Carving of Dragons”), 2 vols. (Beijing: Renmin wenxue chubanshe, 1978), 46–47.

3. The English translation of the first two poems is mine. The translation of “Lisao” is from David Hawkes, ed. and trans., The Songs of the South: An Anthology of Ancient Chinese Poems by Qu Yuan and Other Poets (New York: Penguin, 1985), 67–95, with minor changes. For the translation, I have also consulted Burton Watson, trans. and ed., The Columbia Book of Chinese Poetry: From Early Times to the Thirteenth Century (New York: Columbia University Press, 1984), 54–66, and Stephen Owen, trans. and ed., An Anthology of Chinese Literature: Beginnings to 1911 (New York: Norton, 1996), 162–175. To facilitate reading and discussion, I have broken “Lisao” into sections. The romanizations of Chinese characters in this poem were added by the editor.

4. Ban Gu, Han shu (History of the Han Dynasty) (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1962), 28b.1666, quoted and translated in Hawkes, Songs of the South, 18.

5. Fig trees grow on land, lotuses in water, and thus the speaker is saying that her search for her lord is bound to be fruitless.

6. Most Chinese scholars agree on this. Another view of these two poems is that they are about the two daughters of the ancient sage-ruler Yao, who gave them to his successor, Shun, in marriage. According to the legend, they drowned in the Xiang River when they heard that their Shun had died. Hawkes, who holds this view, states that “the words in both of these songs are sung throughout in propria persona by a male shaman who is pretending to be out in a boat looking for the goddess among her island haunts” (Songs of the South, 106).

7. David Hawkes discusses this theme in “The Quest of the Goddess,” in Studies in Chinese Literary Genres, ed. Cyril Birch (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974), 42–68.

8. Wang and Hong, Chuci buzhu, does not have this character but notes that it was here in another edition. It is included in other editions I consulted.

9. Wang and Hong, Chuci buzhu, does not have this character but notes that it was here in another edition. It is included in other editions I consulted.

10. Compare with lines 21 and 22 in “The Lord of the Xiang River.”

11. Jiuyi Mountain is the burial place of Shun.

12. Ma Maoyuan believes that these are presents of love given to the Lord of the Xiang by the Lady of the Xiang. Citing some examples from ancient texts, he further maintains that exchanging clothes between lovers was an ancient custom (Ma Maoyuan, ed., Chuci xuan [Selections from the “Chuci”] [Beijing: Renmin wenxue chubanshe, 1998], 63).

13. Hawkes discusses the inconsistencies in the accounts of Qu Yuan in early texts (Songs of the South, 51–66).

14. Sima Qian, Shiji (Records of the Grand Scribe) (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1963), 84.2481–2491.

15. Gao Yang, also known as Zhuan Xu, was a legendary lord (di). Qu Yuan’s ancestors were said to be his descendants.

16. Geng-yin is the twenty-seventh day of the month in the ancient Chinese system of calculating days.

17. According to the Shiji, Qu Yuan’s name (ming) was Ping and his title (zi) was Yuan. “True Exemplar” and “Divine Balance” are said to be illustrations of his real name and title.

18. Hawkes, Songs of the South, 27.

19. Wang and Hong, Chuci buzhu, 2–3.

20. Commentators disagree on who these “three kings of old” were. Most adopt Wang Yi’s view, that they refer to King Yu, founder of the Xia dynasty; King Tang, founder of the Shang dynasty; and King Wen of the Zhou dynasty.

21. Yao and Shun were sage-rulers in antiquity.

22. Jie and Zhou were the infamous last rulers of the Xia and Shang dynasties, respectively.

23. The identity of the “woman,” which is my rendering of the Chinese word nüxu (Hawkes translates it as “My Nü Xu”), has been debated for a long time. Wang Yi has claimed, although without offering any evidence, that she was Qu Yuan’s sister. I follow the opinion advocated by You Guoen and others: You regards nüxu as a “common reference to woman” (Lisao zuanyi [Collected Commentaries of “Lisao”] [Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1980], 188).

24. Gun was the father of King Yu, founder of the Xia dynasty. According to ancient legends, Shun entrusted Gun with the task of controlling the flood that was devastating China at that time. He failed, and as a punishment, he was put to death by Shun. Most commentators regard this story to be the source of the reference here. Ma Maoyuan, however, has pointed out another source, which seems more relevant. In chapter 13 of the Han Feizi, it is noted that when “Yao wanted to abdicate to Shun, Gun advised against it, saying, ‘Inauspicious indeed! Who would give up the world to a commoner?’ Yao ignored Gun’s words and put him to death in the plains around Yu Mountain” (Chuci xuan, 18).

25. Cangwu is Shun’s burial place. The “Hanging Garden” is said to be on Mount Kunlun, in the far west.

26. Xi He is the charioteer of the sun.

27. Yan-zi Mountain is where the sun sets in the far west.

28. The Pool of Heaven is a constellation in the western sky. The sun is said to bathe there before setting.

29. Fu-sang is a tree that grows in the far east. The sun shines through it when it first rises in the morning.

30. Ruo is a tree that grows in the far west on Mount Kunlun.

31. Wang Shu is the charioteer of the moon.

32. Fei Lian is the god of the wind.

33. “Bird of Heaven” is Hawkes’s rendering of luan, a supernatural bird that looks like a rooster with brilliant colors.

34. White Water is said to flow from Kunlun Mountain, one of whose peaks is Lang-feng.

35. The House of Spring is the residence of the Green God in the east.

36. Feng Long is the master of the clouds; another view holds that he is also the master of thunder.

37. Fu Fei is the goddess of the Luo River. It is said that she was the daughter of Fu Xi, a leader of an ancient tribe. She drowned in the Luo River and later became its guardian.

38. Wang Yi has claimed, although without providing support, that Jianxiu was a minister of Fu Xi, Fu Fei’s father.

39. Qiong-shi was the home of Lord Yi, a master of archery. In “Heavenly Questions,” another work attributed to Qu Yuan, there is a legend about Lord Yi shooting the god of the Yellow River and abducting the Luo goddess to be his wife. Some commentators, among them Hawkes, regard the reference to Qiong-shi Mountain and the Wei-pan Stream as a suggestion that Fu Fei led a wanton lifestyle (Songs of the South, 91).

40. You, Lisao zuanyi, 290, 294.

41. Ling Fen was a master of divination.

42. The Ford of Heaven is a constellation in the eastern sky.

43. According to Chinese mythology, the God of the West, also known as Shao Hao, presides over the western regions.

44. According to ancient myths, Bu-zhou Mountain is northwest of Mount Kunlun.

45. The Nine Songs are the music of heaven. According to legend, Shao music was the music of the sage-ruler Shun.

46. Luan (literally, disorderly) is a musical term designating the final section of a song. It is so called because it sounded disorderly when all the instruments were played together at the end of a piece.

47. Hawkes, Songs of the South, 68–78.

SUGGESTED READINGS

ENGLISH

Hawkes, David, ed. and trans. The Songs of the South: An Anthology of Ancient Chinese Poems by Qu Yuan and Other Poets. New York: Penguin, 1985.

Qu Yuan. The “Nine Songs”: A Study of Shamanism in Ancient China. Edited by Arthur Waley. 1955. Reprint, San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1973.

Waters, Geoffrey R. Three Elegies of Ch’u: An Introduction to the Traditional Interpretation of the “Ch’u Tz’u.” Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985.

Yu, Pauline. The Reading of Imagery in the Chinese Poetic Tradition. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1987.

CHINESE

Jiang Liangfu 姜亮夫. Chuci lunwenji 楚辭論文集 (Studies of the “Chuci”). Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1984.

Ma Maoyuan 馬茂元, ed. Chuci xuan 楚辭選 (Selections from the “Chuci”). Beijing: Renmin wenxue chubanshe, 1998.

You Guoen 游國恩. Chuci lunwenji 楚辭論文集 (Studies of the “Chuci”). Beijing: Gudian wenxue chubanshe, 1957.

———. ed. Lisao zuanyi 離騷纂義 (Collected Commentaries of “Lisao”). Beijing: Zhonghua shuji, 1980.