4

4

The yuefu poetry of the Han dynasty, conventionally referring to all poems reputedly collected by the Han Music Bureau, is one of the earliest poetic modes to have had a major impact on the later Chinese lyrical tradition. In Han times, the fu (rhapsody or rhyme-prose) was the dominant literary genre and arena in which the major court poets exercised their talents, while yuefu poetry, aside from ritual hymns, was basically ignored. Nonetheless, yuefu verse came to be juxtaposed with the fu as one of the two most conspicuous literary genres in the Han. To properly understand yuefu poetry as a genre, one must investigate its history, themes and content, literary conventions, and stylistic characteristics. Critical issues regarding this genre also include the origins and historical date of the establishment of the Music Bureau, the classification of yuefu, the authenticity of the extant yuefu poems, and authorship. Are yuefu poems folk ballads of simple provenance collected by the imperial court, or are they simply literati imitations by anonymous authors or court musicians? Despite these controversial issues, yuefu verse occupies an unshakable position in Chinese poetry.

Due to the several contradictory statements by the Han historian Ban Gu (32–92) in the Han shu (History of the Han Dynasty), generations of scholars had believed that the Music Bureau was established by Emperor Wu (Han Wudi [r. 140–87 B.C.E.]). However, in 1976 a bell inscribed with the word yuefu was excavated around the periphery of the tomb of the first Qin emperor, Qin Shi Huang,1 and this archaeological find has proven beyond doubt that the bureau was, at the latest, founded in the Qin (221–206 B.C.E.). Although Emperor Wu probably did not originate the institution of the Music Bureau, he certainly was the first ruler to greatly expand its functions, which included providing music for court ceremonies and state sacrifices and allegedly collecting folk songs. The bureau was abolished by Emperor Ai (Han Aidi [r. 7–1 B.C.E.]) in 7 B.C.E. because Confucian scholars had complained about the licentiousness of the regional songs and music, which had been brought into the bureau for court entertainment.2 The extant Han yuefu corpus includes two major types of songs: the first is ceremonial and sacrificial hymns, and the second is popular songs written mainly in pentasyllabic lines on a great variety of topics. The former is verifiably Han, since they are recorded in the Han shu. But the latter, attributed to the Han period, is preserved only in post-Han sources; thus it is difficult to substantiate whether these songs were originally collected by the Han Music Bureau or written by Han authors. The concept that the ruler could view the customs of his subjects and thereby learn their state of mind dates back to the pre-Qin periods. However, as early as the Southern Dynasties, Shen Yue (441–513) states in the “Yueshu” (Monograph on Music), collected in the Song shu (History of the Liu Song Dynasty), that there were no song-collecting officials in either the Qin or the Han.3 Modern scholars, East and West, have also supported this view.4 Despite this scholarly consensus, it is possible that some of the regional songs mentioned in the “Summary of Poetry and Rhapsodies” were among those collected.5

In this chapter, I discuss these ritual hymns and popular yuefu verses in order, providing the historical and cultural backgrounds of these poems and analyses of their content, style, and cultural significance.

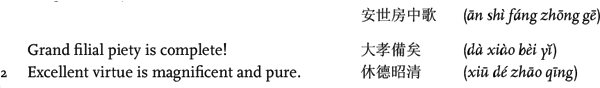

One of the two most important, extant sets of ritual songs of the Han is the “An shi fangzhong ge” (Songs to Pacify the World, for Inside the Palace). The Han shu attributes the authorship to Lady Tangshan, the wife of the Han founder, Liu Bang (Han Gaozu [r. 206–194 B.C.E.]), around 206 B.C.E.6 But both the Sui shu (History of the Sui Dynasty) and the Beishi (History of the Northern Dynasties) attribute this set of poems to the pre-Qin erudite Shusun Tong (fl. 205–188 B.C.E.).7 Later, in the Song dynasty, Chen Yang (twelfth century) emphasizes in the Yueshu (Monograph on Music) that Lady Tangshan only matched the songs with Chu music. Setting the songs in the Chu mode (surely unorthodox in the ritual tradition) would have been in order to please Liu Bang, whose hometown was in the Chu area. There are seventeen songs in total in the Han shu, although some scholars have suggested that they actually number twelve or sixteen. In 194 B.C.E., the head of the Music Bureau, Xiahou Kuan (fl. 193 B.C.E.), was ordered to arrange the songs for flute accompaniment. The name of this set of songs was then changed to “An shi yue” (Songs to Pacify the World). In terms of style, thirteen of these songs were composed in the solemn tetrasyllabic meter. This is the classical style for eulogy in the ancient Shijing (The Book of Poetry) and thus suitable for such ceremonial occasions. Written to praise the achievements of the Han ruler, the poems resemble the eulogies in the Shijing. Four of the poems are in trisyllabic meter or in an unusual mixture of seven- and three-syllable lines. The trisyllabic meter, which is rarely seen in any pre-Han poetic collections, is a special feature of the ritual hymns and other yuefu verses of the Han. The seven-syllable style is even more unusual, since it is found mainly in Han popular sayings and primers for children as a means for learning characters quickly (such as the Ji jiu pian [Primer for Quickly Learning Chinese Characters], by Shi You [fl. 48–33 B.C.E.]), and did not become widely accepted by literati until the late fifth century. The first song opens with an exclamation about filial piety, one of the central ideas of the series:

Songs to Pacify the World, for Inside the Palace, No. 1

[HS 22.1046]

The standard, punctuated Han shu version of the poem ends at line 8; however, I have followed Wang Xianqian (1842–1918) and Lu Qinli (1911–1973) by adding the four lines that, in the 1962 Zhonghua edition, belong to the second song. This first song begins by praising filial piety and continues with an elaborate depiction of the frames for musical instruments, decorative plumes, and banners. According to the commentary of Meng Kang (ca. 180–260), the “Seven Beginnings” (Qi shi [heaven, earth, the four seasons, and man]) and the “Beginning of Quintessence of Myriad Things” refer to musical pieces. Judging from their titles, they were probably used to celebrate the imperial ancestors, the beginning of the royal lineage. Scholars have pointed out that “Songs to Pacify the World” especially emphasize filial piety and virtue, which are key concepts deeply rooted in the culture of the Zhou and Qin dynasties in general. The poem therefore contains a moral message, conveyed through a combination of music, poetry, ritual, and ethical codes. Not until the last few lines is the reader informed about the arrival of the gods. It then becomes clear that the musical instruments and decorations are displayed for the purpose of sacrifices and ritual. This first song is designed to invite the gods or the ancestors to descend to the temple; thus the luxurious display of musical instruments is proper. Wang Xianqian has suggested that lines 5 and 6 do not refer to musical instruments; rather, they are descriptive of the numerous gods.8 But from the context, it seems that both interpretations are acceptable. The content of poem no. 3 further proves that this set of poems must have been written to extol the Han ancestors:

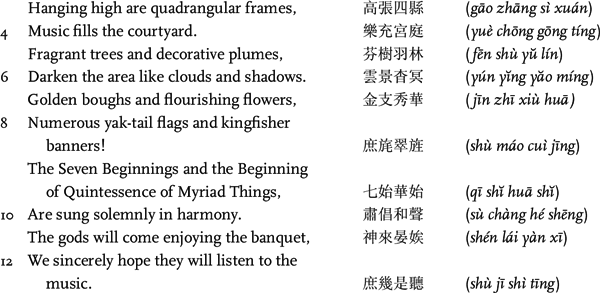

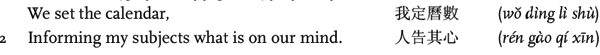

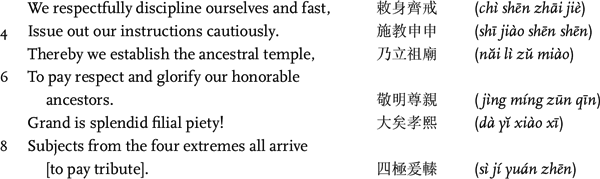

Songs to Pacify the World, for Inside the Palace, No. 3

[HS 22.1047]

This poem adopts the imperial “we,” speaking in the persona of an emperor. Setting the calendar is certainly one of the most significant actions reserved exclusively for the Son of Heaven, since an accurate calendar would have a great impact on people’s lives in an agricultural society. Some commentators have interpreted li shu in line 1 as a heavenly order by which a ruler replaces the previous ruler. In other words, the emperor in the ritual wishes to inform his subjects that it is by heaven’s mandate that he has ascended the throne. The emperor then states that he has fasted and purified himself in order to hold sacrifices at the ancestral temple. In this passage, he demonstrates filial piety toward his royal ancestors, thereby conveying a moral message to his subjects. Through this ritual act of filial piety, the ruler is capable of inspiring loyalty from all the subjects residing even in the remotest areas. Despite the fact that it is unorthodox to adopt regional music for such a solemn occasion, this set of hymns is composed in the Chu mode, stressing Liu Bang’s devotion and feeling toward his native place and ancestry.

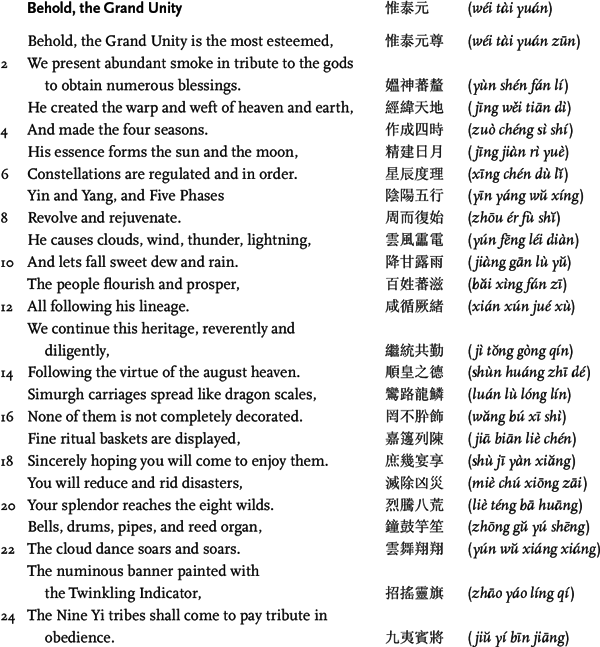

Another celebrated set of ritual hymns verifiably written in the Han are the nineteen songs of the “Jiaosi ge” (Songs for the Suburban Sacrifices), preserved in the “Monograph on Music and Rites” of the Han shu. It is recorded that Emperor Wu performed the suburban sacrifices in 133 B.C.E.; these sacrifices were ancient religious rites that reputedly had existed since the Western Zhou (1066–771 B.C.E.). According to the Han shu, at the time Emperor Wu established the suburban sacrifices, he began to worship the Grand Unity at the Sweet Spring Palace and, also at this time, established the Music Bureau.9 He ordered the bureau to collect regional songs for night chanting and appointed Li Yannian (d. 87 B.C.E.) as commandant of musical harmony to set the music. Li often presented songs and rhapsodies composed by a number of writers, such as Sima Xiangru (179–117 B.C.E.). The great historian Sima Qian (145–86? B.C.E.) commented that the lyrics of these songs were so difficult that scholars versed in only one classic could not interpret them, and it took masters in all the five classics to discuss them together in order to comprehend their general meaning. The content of this set of ritual hymns covers contemporary beliefs as well as state cults. These poems sing of the gods of the four directions and commemorate auspicious incidents or signs, such as the discovery of the sacred tripods and magical unicorns and plants. “Behold, the Grand Unity” is a poem dedicated to the highest celestial god of the Han:

[HS 22.1057]10

The first two lines are problematic in their various possible readings. The character yun in line 2, for example, can also be read as ao, meaning “old woman.” The commentators Li Qi (n.d.) and Yan Shigu (583–645) agree that yuanzun refers to heaven and aoshen to the goddess of the earth, although they disagree on the interpretation of the term fanli.11 Wang Xianqian argues convincingly that taiyuan must refer to the Grand Unity because line 3 mentions that heaven and earth are controlled by the deity, and yun refers to the abundance of the smoke created to communicate with the god.12 The poem’s opening laudatory exclamation to the deity is composed in the formal tetrasyllabic meter, appropriate to its ceremonial function. That the Grand Unity allegedly was a celestial spirit residing in the center of the polestar had tremendous influence on the formation of later Daoist beliefs in the power of this star. In this poem, he is described as the creator of the sun and the moon and as the regulator of the four seasons and the movements of the stars. The harmony of the universe and the generation of life are made possible through the Grand Unity, who transcends not only heaven and earth but also the five emperors of the five quarters. Lines 3–12 extol the awesome power of the god and his role in creation. Lines 13–18 effect a transition to the sacrificial ritual and an invitation to the god. In lines 19–24, the poem expresses the wish and supplication of the imperial house and of the people for the Grand Unity to confer blessings on them. The hymn ends with loud, triumphant music and a dance in which a banner representing the god causes the Nine Yi tribes from the remotest areas to come in surrender. The “Twinkling Indicator” refers to the star γ Boötes, which is also sometimes imagined as part of the Northern Dipper, or Big Dipper.13 According to the Shiji (Records of the Grand Scribe), when the Han dynasty was about to attack Nanyue, a ritual banner painted with the sun, the moon, the Northern Dipper, and an ascending dragon was presented to the Grand Unity during a sacrifice.14 There was probably a contemporary belief that the deity would protect the army and guarantee victory. This suggests the deity’s role as war god and protector of the dynasty. To subdue the tribes on the border areas had been the ideal and dream for nearly all Chinese dynasties. The word jiu (line 24) in classical Chinese in many cases does not mean “nine” but denotes “many.” It was during Emperor Wu’s reign that the borders of China were greatly expanded, and many more minority tribes came to pay tribute at court. In the poem’s last lines, we sense a subtle fusion of the emperor with the Grand Unity, likely one of the poem’s intended messages. By performing the sacrifice to the highest god, the emperor becomes an extension of the deity himself on earth who resides in the court, the center of China. Through him, order will reign, natural disasters will be eliminated, wars will be won, and all the people within China will live in harmony.

Despite their importance in the Han court, these sacrificial hymns had little influence on the development of Chinese poetry and functioned only within their limited religious spheres. They contain an abundance of archaic words, and they are read mostly by specialists today. Secular yuefu songs, however, became a major source of poetic influence in medieval China. The extant Han yuefu corpus, composed mainly of poems in pentasyllabic lines, covers a great diversity of themes. I shall discuss poems on various topics of ordinary life that continue to be popular and widely read by Chinese readers even in modern times. Like the ritual hymns, the secular songs are assumed to have had a close relationship with music. In the most comprehensive yuefu collection, Yuefu shiji (Collection of Yuefu Poetry), the compiler Guo Maoqian (twelfth century) classified all the Music Bureau poems under twelve musical categories.15 It is undeniable that yuefu poems must have had a musical association, since the evidence is in the titles themselves. We find many containing such musical terms as jie (stanzas), yan (prelude), qu (finale passage), and luan (envoi or coda).16 Nonetheless, we must bear in mind that since the music had been lost long before Guo’s time, the classification of his musical categories must be viewed as speculative.

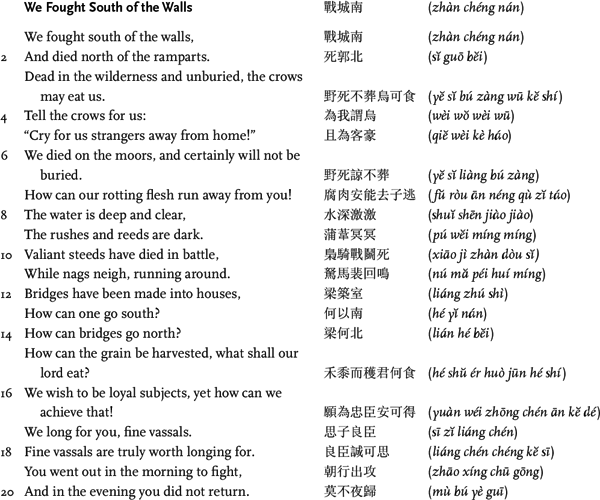

One of the best-known secular yuefu poems is “We Fought South of the Walls,” a poem that contains antiwar sentiments and social concerns:

[SS 22.641]17

This poem belongs to the category of “Duanxiao nao ge” (Songs for Short Panpipe and Nao Bell), which was originally a type of martial music of the Northern Di (a minority tribe) and was introduced to the Han court for use in palace gatherings and processions. In style, the song contains three-, four-, five-, and even seven-syllable lines. The irregular, mixed meter is a feature of the nao ge. Immediately apparent is the striking dissimilarity of the content of the poem to the ritual poems, which are imbued with a completely imperial milieu: this work deals with the life of ordinary people. The persona, represented by the monologue of a dead soldier, is especially interesting. This technique was put into constant use by later yuefu imitators, especially in the pallbearer’s songs.

Some textual problems in the poem make it open to interpretation. For example, the word liang in line 12 sometimes is understood as an empty particle, but other commentators take it as a content word meaning “bridges.” Also, many translators of the poem have adopted the third-person narrative voice, thereby rendering the poem a narrative told by an observer. I take it as spoken by the dead soldier because of the voice in line 4. This reading also creates a more dramatic effect than a third-person narrative. The world depicted in the poem is remote from that of the imperial rhapsodies and ritual hymns. Instead of employing ornate or archaic expressions, the language of the poem is straightforward and powerful. The stark misery of war is brought out by the soldier’s pitiable request to the crows to mourn for him and his fellow soldiers. The word ke (line 5) refers to a person far from home. The fact that the soldiers have traveled far away from their homes and died in a strange place without a proper burial would have been regarded as a great tragedy by the Chinese. It deeply touches Chinese sensibilities, since the ancient Chinese longed to grow old and die in their native place. That the corpses cannot run away but will surely decay and be eaten by the crows (line 7) is uttered in a heartrending voice with a bitter, sarcastic tone. Lines 13 and 14 describe the soldier’s loss of direction, illustrating his confusion and suffering in the cruel battlefield at the last moments of his life. Yet, despite the horrors, the poem has a patriotic element. The soldier expresses his wish to serve his lord with loyalty, despite his untimely death. The last four lines seem to be a response to the speaker’s patriotic wish and, at the same time, convey the poet’s sympathy toward the soldiers. The abrupt transition between lines 14 and 15 seems to indicate a corrupted text, but some scholars think that abruptness is one of the features of a folk song. A ballad of folk provenance implies an oral composition and transmission. In the process of transmission, the singer-poets could change the wording or phrasing to suit their own purposes, hence some texts may appear garbled and incoherent.18

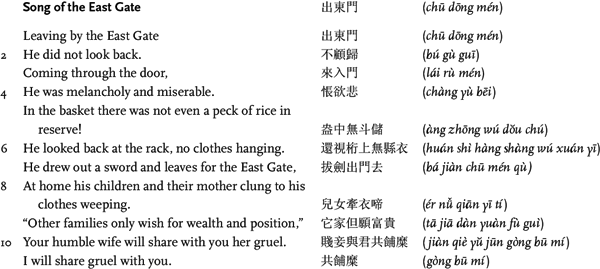

Like that of “We Fought South of the Walls,” the theme of “Song of the East Gate” is related to social hardships:

[SS 21.616]19

“Song of the East Gate” is classified as a “Xianghe ge ci” (Lyrics for Accompanied Songs), which were old Han songs performed to the accompaniment of string and reed instruments. The singer held a rhythm stick during the performance of these songs. The word xing in the title (Dongmen xing) designates some sort of song, and most modern scholars have translated it as “ballad,” which, in European literature, is rather loosely defined and seems to indicate an oral poem of unknown authorship that narrates a story and originates in folk culture. These allegedly Han yuefu poems cannot be ascertained as original folk songs; they could have been literati imitations.20 Several scholars have applied Milman Parry and Albert Lord’s theory of oral poetry to the Book of Poetry and to yuefu poetry in an attempt to prove that these poems are nonliterate folk songs. Charles Egan, however, has argued that there is no direct evidence to prove that these poems were orally or communally composed and transmitted. The more balanced view is thus to consider these poems as the products of the “symbiosis of oral and literate methods that has in fact long characterized balladry.”21 Instead of privileging a single tradition, it is more realistic to consider oral, folk literature and literati writings as being in a constantly interactive relationship.

In the Yuefu shiji, there are two versions of this poem with minor variations between them. Hans Frankel has suggested that “we need not assume that one version is correct and the other corrupt; both may be equally authentic.”22 This sort of variation is certainly a well-known phenomenon in the English ballad tradition.

In analyzing Han yuefu poetry, Cai Zong-qi discerns two major modes: the dramatic and the narrative.23 “We Fought South of the Walls” is in the narrative mode, but “Song of the East Gate” switches between these two modes. First, it contains a clear storyline in which a man in poverty decides to perform an evil act in order to support his family and is being stopped by his wife. Second, the dramatic dialogue between the protagonist and his wife forms the climax of the poem. Lines 1–4, written in a pithy trisyllabic style, convey the persona’s extreme discontent and despair. In general, the style of the song is irregular and mixed, as in “We Fought South of the Walls,” and this probably indicates an earlier stage of Chinese poetry in which the style had not yet become fixed. The song opens with a description of a dismal scene. The deplorable, poverty-stricken condition the protagonist has been reduced to is unbearable. In order to survive, he must act, regardless whether his deed is criminal or not. The wife addresses her husband as an equal and demonstrates great integrity in advising him to stay honest. She first appeals to her husband by pointing out that it is simply against heaven’s way to perform evil acts, and he will not be able to face his own children. Then she expresses her willingness to share this poverty-stricken condition with him. These appeals build up the tension of the poem and advance it to the climax. The denouement is predicted, since there is no other alternative. The only thing the wife is able to offer before her husband leaves is her words of care as a wife. The overall tone of the poem is depressing. Many scholars have read it as a social text that reflects the life of commoners during the Han. The anonymous writer certainly demonstrates a high level of concern for the common people, which completely differentiates him or her from the court poets of the Han.

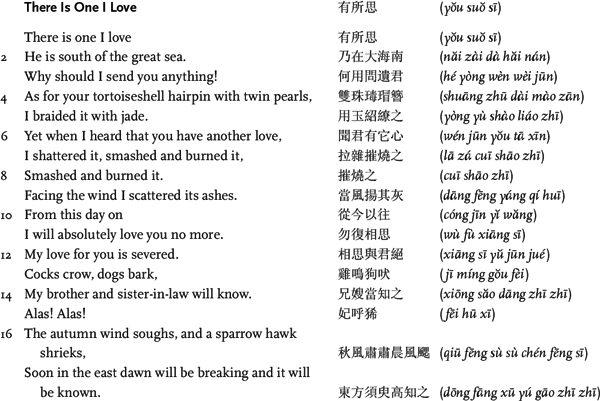

“There Is One I Love” is another example of a song dealing with a nonimperial topic. It is a famous song that falls in the thematic category of romantic love. It is classified in Guo Maoqian’s scheme under “Guchui qu ci” (Lyrics for Drum and Pipe Songs):

[SS 22.642]24

The poem begins with a forthright exclamation of the persona’s love. Even in fifth-century China, few literati would have openly written about their wives or families, still fewer about their own love affairs. Judging from this tradition, it would be hard to imagine any literati of status having written a poem like this. Here, again, it perhaps represents both an original folk song and literati revisions. Not until line 3, which contains the word jun, denoting a male in classical Chinese, does the reader realize that the poem’s persona is a woman. The woman is in love with a man who is far away in the south. When she hears that he has jilted her for someone else, she is furious and decides to burn and destroy his gift to her. The fiery character depicted in this poem is rather different from the typical female image in Chinese literature. Indeed, women in the Han perhaps enjoyed more freedom than those in the Song (960–1279) dynasty, especially in marriage. Divorce was not stigmatized, and remarriage was normal during this era. For example, the wife of Chen Ping (d. 178 B.C.E.), the strategy adviser to the first emperor of the Han, had married five times before marrying Chen—all her previous husbands had died. Overall, the female persona in the poem is a strong, energetic character who will allow no compromise in her love affair.

Line 3 has been traditionally translated as “What shall I send you?”25 Accordingly, it is understood to reveal how the woman is thinking of sending a gift to her lover in the south. But the expression he yong in Han-time usage usually represents a rhetorical “why should” or, more plainly, “do not have to.” The hairpin with pearls seems to be more appropriately understood as a gift from the man. It makes sense that, after the breakup, the woman would wish to burn the love token. The act of destroying the gift not only demonstrates how decisive she is, but also suggests how deeply she has loved the man to have such a violent response. Line 13 is an allusion to poem no. 23 in the Book of Poetry, in which a young woman begs her love to keep quiet during their tryst so that the dogs will not bark. The expression “Cocks crow, dogs bark” sounds especially rustic and perhaps too vulgar and plain for a man of letters. The word ji (cock) first appears in a poetic context in the Book of Poetry, but this is the first poem in which gou (dog) is used. The Book of Poetry contains the word quan for “dog”; gou does not seem to have been a common word until the Han. Except for this yuefu poem, “dog” appears at the earliest in another Han poem, “Jiming” (Cocks Crow), and later in the work of the famous fourth-century poet Tao Qian (Tao Yuanming, 365?–427), whose poetry was not appreciated by his contemporaries because of his unpolished style. In the closure of the poem, the woman discloses her fear that her brother and sister-in-law will learn about her affair. Anne M. Birrell has speculated concerning the woman’s fear that she “believed that the attentions of [the] young official were serious” and, now pregnant, fears that the news will soon come out.26 I doubt that we can determine the identity and status of the woman’s lover, as Birrell proposes. Birrell’s idea that the sparrow hawk is “a metaphor for the swift passage of time” is also baseless. The autumn season at the end of the poem, however, does seem to symbolize a dire future for the young woman, since her unsuccessful affair will become known to her brother. Since line 13 alludes to poem no. 23 in the Book of Poetry, in which a couple’s secret tryst is depicted, lines 13 and 14 may be read as a recollection of the lovers’ rendezvous. The last line describes the woman’s tossing and turning in her bed in anger, confusion, and fear until dawn. This is a vivid poem depicting an outspoken woman who is not afraid to express her true feelings.

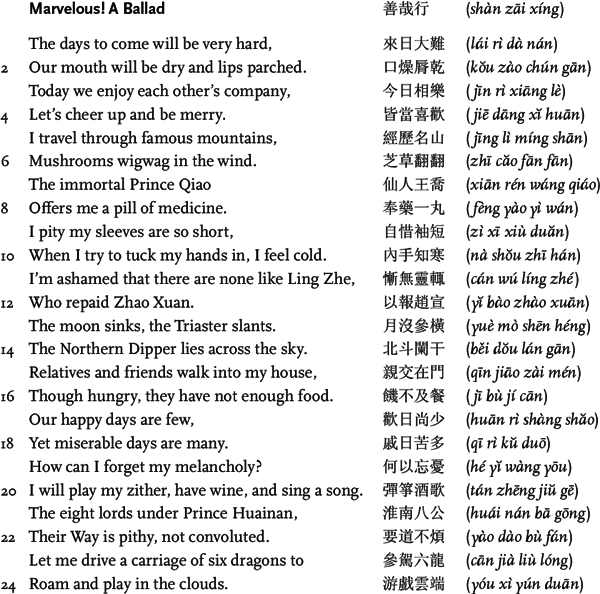

In addition to the topics of social hardships and romantic love, unconventional themes began to develop in the Han yuefu corpus. The youxian (roaming in transcendence) theme wielded great influence on the poetry of the Six Dynasties. “Marvelous! A Ballad,” categorized under “Lyrics for Accompanied Songs,” is one of the earliest poems displaying a combination of what might be called carpe diem and youxian topics:

[SS 21.616]27

The poem is composed in regular tetrasyllabic lines, a pattern that remained popular until the Later Han. The beginning of the poem laments the hardships of life, typical in works that contain the carpe diem poetic theme. The persona exhorts his audience to enjoy one another’s company as much as they can, since prospects for the future are so uncertain. But his attitude is not hedonistic because pleasure is not regarded as the purpose of his life. Rather, he is an escapist seeking distraction from harsh reality, and the cult of immortality provides a channel for him to do so. From the text, we are unable to know if the persona is a true Daoist absorbed in self-cultivation, but the worldly concerns about his own poverty and hunger have detached him from such an image. The protagonist claims that he travels through famous mountains and encounters Prince Qiao, the all-time favorite immortal in the tradition, who offers him a pill. Only when he accepts it does he suddenly realize that he is cold. This at once informs the reader of the coldness of the immortal realm and brings back to the reader’s mind a sense of reality. Although the receiver of such a wonderful gift from the immortal, the persona feels ashamed that he cannot repay him. Ling Zhe was a historical figure of the seventh century B.C.E. who was rescued from starvation by Zhao Dun (Zhao Xuan). He repaid Zhao Dun by saving him from an assassination attempt. When the persona returns to the human realm, he has to face again his dire situation. Here, again, we see an abrupt transition. Under the moonlit sky, all he sees are his poor relatives and friends, for whom he cannot even provide enough food. But this man’s solution to his poverty is drastically different from that in the previously discussed “Song of the East Gate.” Instead of resorting to crime, he chooses first wine and music and then an escape into a world of transcendence. This is typical of what many literati did later in the Six Dynasties, during which wine and music were common channels for forgetting worries. Spiritually, many literati often reverted to Daoist philosophy when their careers suffered. The “eight lords” of the poem were the honored guests invited by Liu An (179–122 B.C.E.), king of Huainan, to his kingdom. Liu was a Han prince famous for his search for immortality and his love of literature and philosophy. Legend has it that he and his guests withdrew from the world and became immortals. In this poem, the youxian theme is concerned not so much with philosophy as with literary imagination. The persona obtains a sense of delight by imagining that he roams in the fantastic world of flying immortals. Through his interstellar journey, he is able to break through the limitations of time and space and acquire a sense of relief and delight. Hence the poem ends in a playful wandering in the sky.

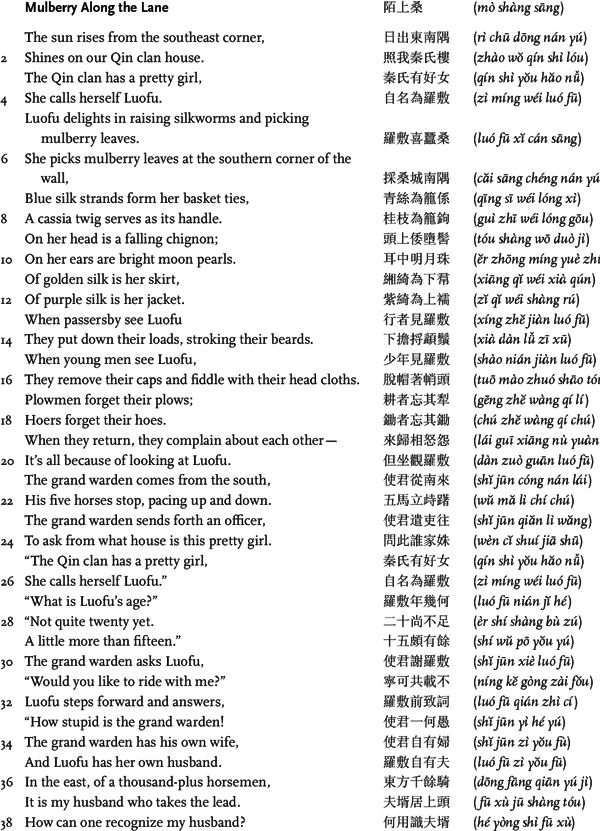

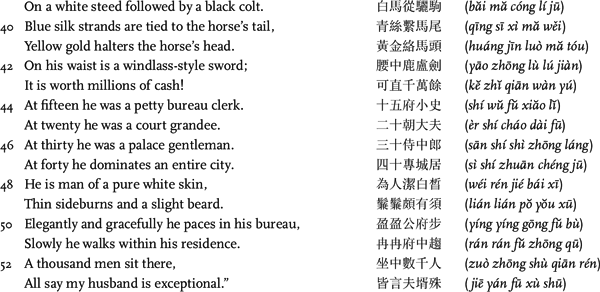

I have discussed several different poetic themes in the Han yuefu corpus, but no general essay on yuefu poetry can exclude the poem “Mulberry Along the Lane,” the most anthologized and the best-known yuefu poem among Chinese readers.28 Modern scholars have placed great emphasis on the contrast between folk songs and literary yuefu, with stress on the former, and this poem is a superb example of coexisting features of folk and literati techniques. In Guo Maoqian’s classification, it is grouped among the “Da qu” (Grand Songs) in the “Lyrics for Accompanied Songs.”

[SS 21.617]

First of all, from the consistent use of the pentasyllabic lines, the poem has been roughly dated to the Later Han, when this style became mature, despite the absence of internal evidence to support this view. Literary style can be deceiving and cannot serve as absolute evidence in dating a literary work. Basically, this song tells of a resourceful woman named Luofu who successfully rebuts the advances of a flirting governor. Traditionally this poem has been interpreted as a representation of social injustice, depicting as it does an official harassing a peasant girl. Recently, however, scholars have begun to deviate from this line of interpretation. Analyzing its form from a comparative perspective, Hans Frankel has pointed out that there is “a type of medieval European pastourelle where a shepherdess thwarts a philandering gentleman.”29 Nevertheless, “Mulberry Along the Lane” has no exact European counterparts. However tempting it might be for scholars to compare similar types of literature from different cultures, such comparisons are in danger of disregarding real cultural differences. Frankel also lists three stylistic features of the poem that, in his view, demonstrate its oral nature: formulaic language, various types of repetition, and exaggeration.30 Lines 3 and 4 (and 25–26) are considered to be instances of formulaic language, since they are similar to a passage in the famous yuefu poem “Kongque dongnan fei” (Southeast Fly the Peacocks). This view probably needs to be modified because it is difficult to ascertain cases of formulaic language with the extremely short length of Chinese poetry.31 Repetition, which is often interpreted as an aide-mémoire and a device to advance the action, is prevalent and obvious in this poem. Exaggeration (lines 38–48, where the young woman boasts of her husband) as evidence of the poem’s oral nature is the weakest, since many kinds of poetry may contain such a device. Although these features are not sufficient to prove that this work is an orally composed poem, they do remain its stylistic characteristics and serve as evidence of its possible borrowing from the folk tradition. Overall, Frankel maintains that this poem is an oral folk song elaborated “by an upper-class poet for an aristocratic audience.”32 Nonetheless, it is open to different interpretations since there is no direct evidence to definitively categorize it.

Zong-qi Cai posits five major characteristics in analyzing this poem: situational thinking, ahistorical presentation, abrupt transitions, composite structure, and repetitions.33 The poem’s composite structure is a particularly important observation. In explaining the composite structure of a folk yuefu, Cai points out that it “involves the participation of several performers who each bring to the work a different point of view, a different set of oral formulas or expressions, and probably a different style of performance as well.”34 Orally composed or not, the performative nature of this poem is clear and serves as a useful interpretative tool. Each section is like a mini-drama with an awareness of an audience.

Traditional interpretations of this poem, especially those from mainland China, usually view it as a story of a brave peasant girl resisting the advances of a lustful governor. This reading, which stresses class struggle and oppression, was typical of mainland scholarship before the 1990s. With the introduction of Western anthropological and literary theories, however, many scholars no longer support it. The tendency in more recent scholarship has been to consider it as a song of flirtation without serious moral issues. Cai, for example, has suggested that it is a work imitating the courtship rite.

This intriguing poem continues to attract different interpretations. The theme of male flirtation is not unusual in the Chinese literary tradition. For example, “Dengtuzi haose fu” (Fu on Master Dengtu, the Lecher) contains a paragraph in which a man politely presents poetry to a young lady to express his love. Qiu Hu, in the Lienü zhuan (Biographies of Various Ladies), represents another example. As Qiu Hu is returning home, he sees along the road a woman collecting mulberry leaves. He attempts to seduce her with gold but is refused. When his wife discovers the true identity of the stranger, in her shame, she drowns herself in a river. There is another story in that collection about collecting mulberry leaves, but without the theme of flirtation. In this story, the king of Qi decides to marry a woman with a big goiter because she is the only one who does not look at him and concentrates only on collecting mulberry leaves.35 From these and similar stories, we know that collecting mulberry leaves for silkworms was an important agricultural activity in ancient China portrayed in several literary texts and genres. The examples we find are all, in one way or another, related to love or the relationship between a man and a woman. Even though we have no direct evidence in this poem relevant to the courtship theory, there is little doubt that the mulberry as an image of love is deeply rooted in Chinese civilization. For example, poem no. 48 in the Book of Poetry talks about a love tryst in the mulberry grounds in the springtime.

Another significant point is Luofu’s beautiful clothes and precious jewelry, which do not suggest a peasant girl, but a woman of some social status. But why, it might be asked, would such a lady collect mulberry leaves, unless the poet is presenting such a properly dressed woman in order to appeal to an aristocratic audience. Another possible explanation is that the image of wealth and luxury expresses the hidden wishes of the common people and is an example of the device of “boastful inventiveness” common in European ballads.36

The grand warden does not appear as an oppressive figure, and that has contributed to the weakening support of the socialist theory of class struggle. The conversation between Luofu and the governor is amusing and relaxed. Luofu’s summary of her husband’s achievements is another example of boastful inventiveness. At Luofu’s refusal, the poem stops, as do the governor’s advances. Considering it a culmination of the boastful device, several scholars have suggested that, at the critical moment, Luofu invents a husband who outranks the governor.37 It is also possible that the poem, as received, is incomplete. In any case, these different interpretations are perhaps not mutually exclusive but mutually illuminating. The original poem perhaps intended to reflect social ills, but different themes could have arisen through adaptation and performance. Some readers may still see its commentary on the social reality despite its adaptations for performance and entertainment. Due to our insufficient knowledge of its textual revisions, performative context, and intended audience, all interpretations are tentative and subject to question.

In this chapter, we have considered two entirely separate sets of poems. The first, the religious hymns written during the Western Han and performed at ceremonial occasions, have had little impact on Chinese literature. The second group, however, dealing with ordinary people’s daily life, became the fountainhead of medieval Chinese poetry. Both types were generally composed by anonymous authors and were placed under the loose category of yuefu verse by later compilers. The term yuefu as a generic label did not appear until the sixth century, however, and so scholars have challenged the validity of this word as a generic label.38 Despite the lingering controversy around such questions as the origins of the Music Bureau its official functions, and authenticity, the Han Music Bureau corpus continues to play a critical role in Chinese literary history.

NOTES

1. For a detailed discussion of these issues, see Anne M. Birrell, “Mythmaking and Yüeh-fu: Popular Songs and Ballads of Early Imperial China,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 109, no. 2 (1989): 223–235.

2. Ban Gu, Han shu (History of the Han Dynasty) (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1962), 22.1071–1074.

3. Shen Yue, comp., Song shu (History of the Liu Song Dynasty) (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1965), 19.550; Charles Egan, “Reconsidering the Role of Folk Songs in Pre-T’ang Yüeh-fu Development,” T’oung Pao 86, nos. 1–3 (2000): 77.

4. Egan, “Reconsidering the Role of Folk Songs,” 78–99; Zhang Yongxin, Han Yuefu yanjiu (A Study of Han Music Bureau Poetry) (Nanjing: Jiangsu guji chubanshe, 1992), 58–63.

5. Ban Gu, Han shu 30.1754–1755.

6. Ban Gu, Han shu 22.1043.

7. Wei Zheng (580–643), ed., Sui shu (History of the Sui Dynasty), 75.1714; Li Yanshou (seventh century), ed., Beishi (History of the Northern Dynasties), 82.2757.

8. Wang Xianqian, Han shu buzhu (Complementary Annotations to the “History of the Han Dynasty”) (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1983), 1:482.

9. The Shiji (Records of the Grand Scribe) records that Emperor Wu began to present sacrifices to the Grand Unity, the highest deity in Han times, in 124 B.C.E. (Xiao Tong, comp., Wen xuan, or Selections of Refined Literature, vol. 1, Rhapsodies on Metropolises and Capitals, trans. David R. Knechtges [Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1982], 276).

10. For another translation and comments, see Anne M. Birrell, Popular Songs and Ballads of Han China (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1993), 38–39.

11. Ban Gu, Han shu 22.1057.

12. For an interpretation of ao or yun, see David R. Knechtges, “A New Study of Han Yüeh-Fu,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 110, no. 2 (1990): 312.

13. Xiao Tong, Wen xuan, 1:214.

14. Sima Qian, Shiji (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1963), 12.471.

15. Joseph R. Allen, In the Voice of Others: Chinese Music Bureau Poetry (Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, University of Michigan, 1996), 39–40.

16. Knechtges, “New Study of Han Yüeh-Fu,” 310–311.

17. For other translations, see Arthur Waley, trans., Chinese Poems: Selected from “170 Chinese Poems,” “More Translations from the Chinese,” “The Temple” and “The Book of Songs” (London: Allen and Unwin, 1946), 52, and Wu-chi Liu and Irving Yucheng Lo, eds., Sunflower Splendor: Three Thousand Years of Chinese Poetry (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1975), 35–36.

18. For a list of characteristics of the folk yuefu, see Zong-qi Cai, The Matrix of Lyric Transformation: Poetic Modes and Self-Presentation in Early Chinese Pentasyllabic Poetry (Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, University of Michigan, 1996), 29.

19. For another translation, see Birrell, Popular Songs and Ballads, 134.

20. Egan has presented systematic and strong arguments about these issues in “Reconsidering the Role of Folk Songs,” 47–99, and “Were Yüeh-fu Ever Folk Songs? Reconsidering the Relevance of Oral Theory and Balladry Analogies,” Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews 22 (2000): 31–66.

21. Egan, “Were Yüeh-fu Ever Folk Songs?” 57.

22. See Hans Frankel’s classic study “Yüeh-fu Poetry,” in Studies in Chinese Literary Genres, ed. Cyril Birch (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974), 81.

23. Cai, Matrix of Lyric Transformation, 21–59.

24. For other translations, see Waley, Chinese Poems, 54, and Birrell, Popular Songs and Ballads, 147–148.

25. Birrell, Popular Songs and Ballads, 147.

26. Birrell, Popular Songs and Ballads, 148.

27. For another translation, see Birrell, Popular Songs and Ballads, 80–82.

28. For other translations, see Waley, Chinese Poems, 65–67; Liu and Lo, Sunflower Splendor, 34–35; and Birrell, Popular Songs and Ballads, 169–173.

29. Frankel, “Yüeh-fu Poetry,” 81.

30. Hans Frankel, “Some Characteristics of Oral Narrative Poetry in China,” in Études d’histoire et de littérature chinoises offertes au Professeur Jaroslav Průšek, ed. Yves Hervouet (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1976), 97–106.

31. Egan, “Were Yüeh-fu Ever Folk Songs?” 47.

32. Frankel, “Some Characteristics of Oral Narrative Poetry,” 105.

33. Cai, Matrix of Lyric Transformation, 33–48.

34. Cai, Matrix of Lyric Transformation, 38.

35. Zhang Qi, “Han yuefu ‘Moshang sang’ xintan” (A New Study of the Han Music Bureau Poem “Mulberry Along the Lane”), Lanzhou xueyuan xuebao 3 (1995): 94–95.

36. Frankel, “Some Characteristics of Oral Narrative Poetry,” 104–105.

37. Frankel, “Some Characteristics of Oral Narrative Poetry,” 105.

38. Birrell, “Mythmaking and Yüeh-fu,” 26–27.

SUGGESTED READINGS

ENGLISH

Birrell, M. Anne. “Mythmaking and Yüeh-fu: Popular Songs and Ballads of Early Imperial China.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 109, no. 2 (1989): 223–235.

———. Popular Songs and Ballads of Han China. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1993.

Cai, Zong-qi. The Matrix of Lyric Transformation: Poetic Modes and Self-Presentation in Early Chinese Pentasyllabic Poetry. Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, University of Michigan, 1996.

Egan, Charles. “Reconsidering the Role of Folk Songs in Pre-T’ang Yüeh-fu Development.” T’oung Pao 86, nos. 1–3 (2000): 47–99.

———. “Were Yüeh-fu Ever Folk Songs? Reconsidering the Relevance of Oral Theory and Balladry Analogies.” Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews 22 (2000): 31–66.

Frankel, Hans. “Yüeh-fu Poetry.” In Studies in Chinese Literary Genres, edited by Cyril Birch, 69–107. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974.

CHINESE

Chen Yicheng 陳義成. Han Wei Liuchao yuefu yanjiu 漢魏六朝樂府研究 (Studies on Han, Wei, and Six Dynasties Music Bureau Poetry). Taipei: Jiaxin shuini gongsi wenhua jijinhui, 1976.

Luo Genze 羅根澤. Yuefu wenxue shi 樂府文學史 (The Literary History of Music Bureau Poetry). Beijing: Wenhua xueshe, 1931. Reprint, Taipei: Shijie shuju, 1974.

Wang Yunxi 王運熙. Yuefu shi luncong 樂府詩論叢 (Essays on Music Bureau Poetry). 1958. Reprint, Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1962.

Xiao Difei 蕭滌非. Han Wei Liuchao yuefu wenxue shi 漢魏六朝樂府文學史 (The Literary History of Han, Wei, and Six Dynasties History). Chongqing: Zhongguo wenhua fuwu she, 1944.

Yao Daye 姚大業. Han yuefu xiaolun 漢樂府小論 (Essays on Han Music Bureau Poetry). Tianjin: Baiyi wenyi chubanshe, 1984.

Zhang Yongxin 張永鑫. Han yuefu yanjiu 漢樂府研究 (A Study of Han Music Bureau Poetry). Nanjing: Jiangsu guji chubanshe, 1992.