16

16

Song Poems (Sanqu) of the Yuan Dynasty

During the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368), popular literature flourished. A new verse form, the sanqu (song poem), which had close ties with music and drama, became the most energetic poetic genre of the time.

The sanqu belongs to the tradition of song verse. Like the ci, sanqu originally were verses set to music. The tunes or the metrical patterns used in song poems, however, are different from those in the ci, because the sanqu tunes were nurtured by the music of a different time with special features of its own. To understand this, one need only note that the genre grew in the north. Its origin can be traced back at least to the folk songs, with their distinctive local color, that were popular in the Jin dynasty (1111–1234), when northern China was under the rule of the Jurchens. The genre came to full blossom in the Yuan dynasty under Mongol rule, which witnessed intense interaction between traditional Chinese culture and the cultures of the non-Han peoples from the north and west.

The typical language of song poems is the northern vernacular Chinese, with its vigorous colloquial flavor so characteristic of the genre. Although most of the songs written by the versifiers from the streets and entertainment quarters have been lost, and the great majority of the song poems handed down to us were actually works of literati poets, here and there in these poems the fresh and pungent idioms and the spicy and rambunctious humor, accompanied by a vivacious flow of everyday speech, unmistakably tell of the genre’s origins. The following observation by a modern scholar, therefore, seems not far from the truth: “Unless a chü [sanqu] had at least a modicum of vulgar speech, it was thought to be a less than satisfactory example of the genre.”1

The verse form of the song poems is basically the same as that of the arias in the zaju, the Yuan variety plays, which also developed in the north. The blood link between the two genres is evident from the name sanqu itself, which literally means “dispersed [dramatic] songs.” It comes as no surprise, then, that most of the Yuan playwrights were also masters of the song poem.

The Mongol rulers of the Yuan were not enthusiastic about traditional Chinese mores, nor were they promoters of serious literature. Ironically, their negligence of cultural affairs proved to be a blessing to the development of the song poem and other forms of popular literature. Writers felt less restricted by the traditional ethical code. Also, many scholars, well versed in the classics and literature but not able to—or reluctant to—join the civil service because of the political situation of the time, diverted their talent to the writing of song poems and variety plays.2 The pluralistic style and the wide range of subject matter of the song poem well reflect the genre’s humble origins as well as the influences on the genre from the powerful poetic tradition of Chinese high literature. At one end of the spectrum are song poems dealing with the time-honored poetic topics so often found in the shi and the ci, like meditations on the past, reflections on seasonal changes, or celebration of the quiet life of a recluse; at the other are found witticisms, mockery, lighthearted parodies, and nonsensical jokes. However, love songs of various kinds, often cliché-ridden but sometimes enlivened by bold and witty expressions and graphic descriptions, outnumber songs of other categories.

MUSIC AND PROSODY

The early song poems were really “song words” created to fit the music. As the tunes themselves got lost with the passage of time, only the word or verse formulas—the tune patterns, as they are called—remained, and the practice of sanqu writing became a matter of composing verses to fit the existing tune patterns. Each tune pattern belongs to a certain musical mode. The mode differs from the tune in that the latter can be defined as the metrical pattern informed with the melodic spirit of the music, whereas the former is the key or the tonality of the music, reflecting such values as the pitch and color of notes as well as their interval patterns, all of which were believed to have had a significant impact on the tone and mood of song poems in the early days of the genre, when they were meant to be sung. The extant corpus of the nondramatic song poems includes more than two hundred tune patterns but only nine musical modes in common use. A considerable number of the tune patterns used in the composition of song poems are also found in the arias in the Yuan variety plays.

There are two forms of sanqu: the single song poem (xiaoling) and the song suite (santao). The single song could be expanded by a reprise or combined with one or two other single songs of different tunes to form a bigger unit. It was also a common practice for songwriters to compose several single songs to the same tune but with different titles and put them together in a loosely connected sequence. A song suite consisted of the integration under one title of a group of single songs in the same mode and with the same rhyme. The number of songs included in a song suite could be as few as a couple or as many as two to three dozen. Each song suite is usually introduced by a “head” composed of one or two short stanzas and concludes with a coda.

To better understand sanqu prosody, let us look at two song poems and examine their metrical patterns and rhyme schemes. The first is “Fat Couple,” by Wang Heqing (fl. 1246):

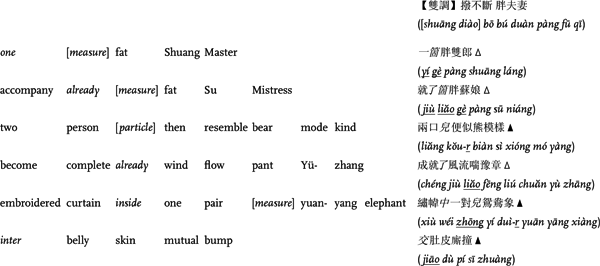

To the Tune “The Unbreakable String” [shuangdiao key]: Fat Couple

A rather obese Master Shuang

2 Bore off an overweight Miss Su-niang

(Each one of that pair

4 Was the size of a bear!)

On the wings of romance, off they sped,

6 But paused a while at Yü-chang to pant—

These lovebirds the size of an elephant—

8 And bang their bellyskins in bed!

[QYSQ 1:47]3

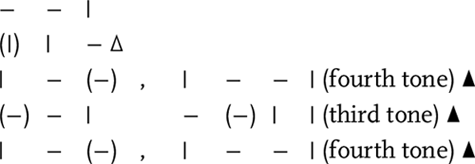

With its lines of irregular length, this song poem looks very much like a stanza taken from a ci. Indeed, it “sounds” like a ci, too. The novel rhythmic effect resulting from the alternation of the long and short lines we have seen in the ci can also be strongly felt in this sanqu. If we ignore the italicized syllables in the song, we can extract the skeleton of its tune pattern:

The tonal patterns of the three-, four-, and seven-character lines are no different from those found in commonly used ci lines. Indeed, the types of seven-character lines in this poem are exactly the same as typical seven-character ci lines, which were actually “inherited” by the ci from the lüshi (regulated verse).5

This similarity, however, is not always the case. The second example, a poem by Ma Zhiyuan (1250?–1323?), clearly illustrates this:

To the Tune “The Song of Shouyang” [shuangdiao key]

Things in my heart,

2 To him I did impart.

“It’s finished between us!” his reply came quick, as always.

4 How can such cruel words be “just a joke,” as you said.

Should I not be afraid?

[QYSQ 1:247]

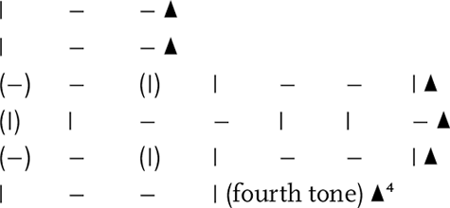

Again, we can ignore the italicized syllables and extract the tune pattern of the song:

The tonal patterns of lines 3 and 5, │ ─ (─), │ ─ ─ │ (fourth tone) ▲, and of line 4, (─) ─ │ ─ (─) │ │ (third tone) ▲, are common in seven-syllable lines of the song poem, but are not found in those of the ci and the lüshi. One cannot but wonder if it was not the different characteristics of the musicality of the song poem that brought about these new types of seven-syllable lines, whose tonal patterns deviate so much from the norms of the ci and the lüshi.

The rhyme scheme of the song poem also claims our attention. As can be seen from the two preceding examples, only one rhyme is allowed in a song poem. Since the Yuan sanqu writers used the northern vernacular, they did not follow the archaic rhyme categories used in the lüshi and the ci but adopted a new system that reflected more accurately the realities (not the least of which was the disappearance of the entering tone) of the living language. Unlike in the lüshi and the ci, level tones and oblique tones can be rhymed in song poems. This did not mean, however, that a sanqu composer could disregard the difference between the level and the oblique tones. On the contrary, some tune patterns strictly stipulated that certain rhymed words could be in only certain tones. For instance, in “The Unbreakable String,” the rhymed word in the last line had to be in the fourth tone; in “The Song of Shouyang,” the rhymed words in lines 3 and 5 had to be in the fourth tone, and the rhymed word in line 4 could be in only the third tone. A possible reason for this is that rhymed words with carefully chosen tones better matched the music underlying the tune patterns.

The italicized syllables in the two preceding poems, which we ignored in order to see the basic tune patterns, should not be overlooked. They are the “padding words,” or extrametrical syllables (chenzi). It is in them that we see the most important difference between the meters of ci lines and sanqu lines. A sanqu composer could add to any verse line—almost at will, although not at the end of the line—extrametrical syllables and thus further vary the shape of the verse. There was no limit to the number of syllables that could be added. For example, there is the following line from “Not Giving In to Old Age” (Bufu lao), by Guan Hanqing (ca. 1220–ca. 1307):

I am a jingling tingling bronze bean that remains hard after being steamed, raw after being stewed, that bounces under a big hammer and will not pop when being baked.

我是個蒸不爛煮不熟錘不匾炒不爆響璫璫一粒銅豌豆

wŏ shì gè zhēng bú làn zhŭ bù shóu chuí bù biăn chăo bú bào xiăng dāng dāng yí lì tóng wăn dòu

[QYSQ 1:173]

Only the first two and the last five syllables—“I am a bronze bean”—are required by the tune pattern; the other sixteen are all padding syllables! With the help of the extrametrical syllables, composers of song poems could alter the pace and rhythm of the verses in imitation of the natural flow of everyday speech. This may partly explain why, compared with ci verses, song poem verses are more complete in their syntactic structure and read more like sentences from spoken language. Where one finds poetic ellipsis in a shi or a ci poem, one often finds padding words in a song poem.

Besides the colloquial nature of the language of song poems, the musical origin of the genre can also shed some light on its abundant use of the extrametrical syllables. Inasmuch as the tune patterns are the vestiges of the original music, it is only natural that, even after the tunes themselves were lost, the intrinsic musical quality of the tune patterns would prompt the later song poem composers to fill in the gaps left by the silence of the lost melodies.

POEMS ON NATURAL SCENERY AND HUMAN SENTIMENT

A favorite theme of song poems is natural scenery and the poet’s reflection on it. The following example happens to be the single best-known sanqu work by arguably its best writer, Ma Zhiyuan. Ma Zhiyuan is one of the four great Yuan dramatists, but he is better known for his sanqu works. His mastery of the art is exemplified by “Autumn Thoughts,” in which a series of carefully chosen images establish the mood. His meditative song poems on the quiet life of seclusion reveal the influence of Daoism, and they are considered by many to be too pessimistic. His works in this genre generally are representative of the more refined literati style, and yet there is no lack of the freshness and verve seen in works of the popular style.

To the Tune “Sky-Clear Sand” [yuediao key]: Autumn Thoughts

Withered vines, old trees, crows at dusk,

2 A small bridge, flowing water, people’s homes,

An ancient road, the west wind, a lean horse.

4 The evening sun goes down in the west.

One heartbroken man at the end of the earth.

[QYSQ 1:242]

The imagistic nature of this song is obvious. Except for the word xia (goes down) at the end of line 4 in the original, the whole song contains no active verb but only descriptive noun phrases. To compare it to a picture and say that “the poet unfolds a scene like a scroll of Chinese painting”6 might, however, oversimplify the poetic experience and miss the real spell of the piece. Indeed, the poet does not encourage readers to view as onlookers the picture of a traveler on an autumn evening; rather, he invites them to identify with the traveler. Thus by the end of the song, the traveler’s homesickness comes to readers not as a trite sentiment but as a personal experience with a heartrending freshness.

The identical verse structure of the first three lines often leads the unwatchful eye to read them together as a parallel triplet. A close examination of the values carried by the three clusters of images embedded in these lines, however, reveals that, as far as the poetic narrative is concerned, lines 1 and 2 form a thematic unit, while line 3 functions on a different level. The “withered vines, old trees,” and flocks of black crows present a wild and repellent—if not threatening—nature, whereas the “people’s homes” and “small bridge” (which, as a man-made object, evokes everyday human activity), with the gurgling water under it, create a congenial ambience. The implication of the contrast between these two sets of images, however, renders itself fully only when readers come to line 3.

Compared with the concrete images (although not without their symbolic connotations) in the two foregoing lines, the images in line 3 are less specific and appear more like symbols. The ancientness of the road, something not actually discernible, leads readers beyond the scope of the scene at hand and lets them see in their mind’s eye the endless road extending into other spaces and other times. The “west wind” not only indicates the time of year but also implies the sadness felt during the season of decay—that is, all the burden carried by the image of autumn in the Chinese literary tradition. Most significantly, the synecdochical use of the “lean horse,” in turn, puts readers in the place of a weary traveler in order to feel the hardship he endures. Line 3 thus allows readers—from a traveler’s point of view—to interpret and comment on the situation presented in the couplet preceding it:7 the homey scene in line 2 appears so inviting simply because it is a familiar scene that the weary traveler sees, however, in an unfamiliar and forbidding setting (represented by the images in line 1) in his journey. It touches off his memory of home; yet, paradoxically, it also reminds him that his own home and its comforts are in another place far beyond reach.

The sight of the crows at dusk at the end of line 1 makes clear the time of day. As if this were not enough, however, the time is pronounced again in line 4: “The evening sun goes down in the west.” This line is the shortest in the song, and it contains the only action verb, whose function is to convey with a sense of urgency and inevitability the message: the day is running out, just as the year is approaching its end. It is at such times that the traveler most keenly feels he should be home. But, alas, everything he sees tells him that home is at the other “end of the earth.”

The following song poem is by Zhang Yanghao (1269–1329), whose reputation as an upright high-ranking official perhaps threatens to eclipse his literary achievements. His rich personal experience, on the one hand, empowers his sanqu works with an insight into history and human suffering and, on the other, makes his song poems on withdrawal and retirement seem more genuine and sincere.

To the Tune “Sheep on Mountain Slope” [zhonglü key]: Meditation on the Past at Tong Pass

Peaks and ridges press together,

2 Waves and torrents rage,

Zigzagging between the mountains and the river runs the road through Tong Pass.

4 I look to the Western Capital,

My thoughts linger.

6 It breaks my heart to come to the old place of the Qin and the Han.

Now palaces and terraces have all turned to dust.

8 Dynasties rise,

The common folk suffer;

10 Dynasties fall,

The common folk suffer.

[QYSQ 1:437]

The poet begins the song by directing the reader’s eye to the road that runs through Tong Pass, which guards the passage to the ancient Western Capital and has witnessed numerous bloody battles. Two verbs—“press” and “rage”—are used in lines 1 and 2 to personify the ruggedness of the geography. The static mountains are thus set in motion, and the irresistible force of the running river is vividly brought forth, suggesting the fierceness of the military conflicts staged in this locale in ancient times. The personification also lends feelings to the mountain ridges and the river waves, so much so that it seems as though they are responding to the poet’s thoughtful gaze. The phrase “between the mountains and the river” in line 3 is a quote from the classic Zuo zhuan (Zuo Commentary on the “Spring and Autumn Annals”), in which a military strategist uses the phrase to illustrate the impregnability of his country’s natural defense. The allusion gives the images the weight of its 2,000-year-old history. It is they, “the mountains and the river,” that bear witness to the rise and fall of dynasties.

Meditation on the past (huaigu) is an old poetic tradition. Numerous poems on the subject were written before—and after—Zhang Yanghao, yet this modest piece stands out as one of the most frequently anthologized huaigu poems. A possible explanation can be found in the poet’s skill in turning the formal restrictions of the poetic form of the song poem to advantage. The eight short lines—two of them have only one syllable each—are combined with the three long lines to form a rhythmic and easy-to-memorize sound flow. The most forceful and unforgettable are the four concluding lines. Each of the two monosyllabic lines—“[Dynasties] rise” and “[Dynasties] fall”—is followed by the same refrain: “The common folk suffer.” The idea that, whatever the case, the people suffer could never have been expressed with such clarity and emphasis had the poet not had this terse contrastive formal structure at his disposal.

The fact that the thematic content of “Meditation on the Past at Tong Pass” is necessarily sustained by its formal properties can be seen even more clearly if we examine the eight other songs by Zhang Yanghao written to the same tune on the same subject. Each of the eight songs uses a historical site as the vantage point from which the poet contemplates the past, and each exploits the tight antithetic structure at the end required by the metrical pattern to drive home its message. The following examples show how some of these huaigu songs end the same way as “Meditation on the Past.” The tone of sententious certainty, tinged with resignation, is hard to miss:

[Kingdoms] win, / They turn to dust; / [Kingdoms] lose, / They turn to dust.

贏 都變做了土 輸 都變做了土

yíng / dōu biàn zuò liăo tŭ / shū / dōu biàn zuò liăo tŭ

[QYSQ 1:436]

[Dynasties fall] sooner, / Heaven makes it so; / [Dynasties fall] later, / Heaven makes it so.

疾 也是天氣差 遲 也是天氣差

jí / yĕ shì tiān qì chāi / chí / yĕ shì tiān qì chāi

[QYSQ 1:438]

The King? / Sacrificed in vain; / The subjects? / Sacrificed in vain.

君 乾送了 民 乾送了

jūn / gān sòng liăo / mín / gān sòng liăo

[QYSQ 1:436]

Glory, / It does not last; / Fame, / It does not last.

功 也是不長久 名 也是不長久

gōng / yĕ shì bù cháng jiŭ / míng / yĕ shì bù cháng jiŭ

[QYSQ 1:437]

Zhang Yanghao’s creative use of the tune pattern of “Sheep on Mountain Slope” is but one example of how a song poem master can turn the restrictive formal requirements of a sanqu matrix into powerful devices for thematic expression. I return to this issue later in the chapter.

POEMS ON THE LIFE OF A RECLUSE

Let us look at two song poems by Qiao Ji (1280–1345), a master songwriter who was very conscious of the technique of sanqu composition. Qiao Ji’s best song poems are fresh, with sharp images and novel expressions, and the aesthetic finish of his works is not achieved at the expense of natural simplicity and ease.

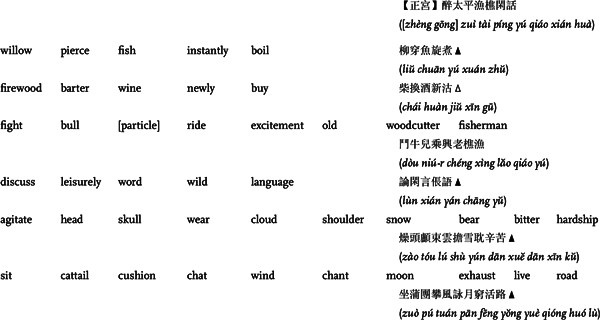

To the Tune “Drunk in a Peaceful Time” [zhenggong key]:

Idle Chats of the Woodcutter and the Fisherman

The fish, skewered on a willow twig, is cooked without delay.

2 The wine was newly obtained by bartering the firewood away.

Now the old woodcutter and the old fisherman have the leisure to watch fighting bulls,

4 And exchange gossip and idle hearsay.

The hardship of going through rain and snow troubles their heads,

6 Yet they make the best of their meager living by chanting of the moon and discussing the wind on a straw mat,

And with blurry eyes, they talk about heaven and earth over a wine gourd.

8 What a painting of mountains and rivers!

[QYSQ 1:574]

The two images at the beginning of the song, the fisherman’s fresh catch from the river and the wine that the woodcutter purchased with the worth of a day’s labor, conjure up a bright picture of the callings of the two men. Their lives are spontaneous, free, and self-sufficient. However, had the poet not skillfully suggested the pleasant freshness of the fish and the “newness” of the wine, which appeal to both the reader’s palate and mind, the images could well have projected a very different view: of two poor fellows barely able to eke out their existence by living from hand to mouth. Throughout the song, in fact, it is the poet’s selective candidness and light tone that make readers see the ease and satisfaction in an otherwise hard and scanty life. So even when the hardship that the two men have to endure is presented (line 5) side by side with the leisure they enjoy (lines 6–7), readers nonetheless feel that the physical hardship is more than compensated for by the richness of their spiritual enjoyment.

As mentioned, Qiao Ji was a conscious stylist who concerned himself with the art of writing. He is said to have set certain rules for the composition of song poems. A good song, according to him, should have “the head of a phoenix, the belly of a pig, and the tail of a leopard”8—that is, a beautiful beginning, a substantive middle section, and a powerful ending. Judging from what we have seen so far, “Idle Chats of the Woodcutter and the Fisherman” seems to have an eye-catching beginning and a healthy body. How about its ending?

The poet brings his description to a sudden stop with the authorial comment that the idyllic life he has presented would fit perfectly in a landscape painting. The scene he has depicted instantly becomes an object within a frame to be admired. This unexpected move concluding the song is, indeed, as powerful as a leopard. It forces readers—now the viewers of a painting—to step back and look at the woodcutter and the fisherman in perspective and to realize that they are no ordinary woodcutter and fisherman, but symbols of certain values that deserve to be treasured dearly.

The woodcutter and the fisherman had long been used as stock images of the recluse and were a favorite topic of Yuan sanqu writers.9 It is interesting to note that actual woodcutters and fishermen could not read and write and did not know the beauty of being in a “painting of mountains and rivers.” It was the educated elite who narcissistically saw themselves in the idealized recluse images they created.

Hu Zhiyu (1227–1293) must have had this in mind when he wrote two songs on the subject. The first is about an educated fisherman; the second, a pair of illiterate woodcutter-fishermen recluses.10 Hu Zhiyu took pains to show the differences between the two types of recluse. The first piece uses elegant language and is replete with allusions to literary and classical texts, giving a learned appearance; the second is colloquial in tone and, in syntactic structure, imitates the easy flow of everyday speech through its lavish use of extrametrical syllables. But language aside, there is no other clue to any major differences between the literate recluse and his illiterate counterparts in these two songs. For instance, what the literate fisherman does all day in the first song is exactly the same as what the unlettered woodcutter and fisherman do in the second, which is to engage in high-minded talk about the vicissitudes of life. The poet creates two kinds of recluse in the two songs in an attempt to give some legitimacy to the scholar-official recluse under the guise of the woodcutter-fisherman. But one can see that, educated or not, the personae in the two songs are not those who really cut wood and catch fish; rather, they are transfigured images of what the poet imagines he himself could be.11

In another song eulogizing the life of a recluse, Qiao Ji speaks in the voice of an “I”:

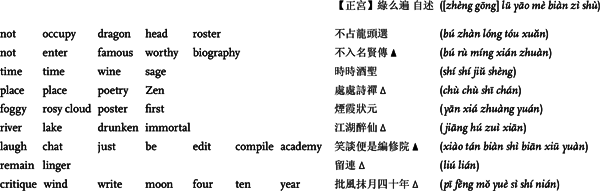

To the Tune “Lüyaobian” [zhenggong key]: Of Myself

I was not chosen to head the dragon list,

2 Nor was my name entered into the biography of worthies

From time to time I’m a sage of wine,

4 Finding everywhere the Zen of poetry—

Highest graduate of the college of clouds and mists,

6 Drunken angel of rivers and lakes,

My talks and jokes are fit for the Imperial Academy of Compilation.

8 Loitering,

I’ve been writing commentaries on the wind and the moon for forty years.

[QYSQ 1:574–575]12

With its ostentatious celebration of the freedom from the burdens of officialdom, this song also belongs to the tradition of recluse literature. Seldom do we see in similar works written before it the carefree playfulness it demonstrates.13 The persona in this song does not disguise himself as a woodcutter or a fisherman. On the contrary, he makes no secret of his impressive educational background in this humorous poetic version of his curriculum vitae. Of most interest about this retired scholar is that, in order to articulate his rejection of the civil service examination system, he has to borrow a whole set of vocabulary from that system. For instance, to thumb his nose at the academic honor, he boasts of the honor of not being honored for academic success. He titles himself the “highest graduate of the college of clouds and mists,” only to show how little he cares about the same title in the mundane world. Even when he is drunk, he remains sober enough to claim himself the “sage of wine,” trusting that his readers will see the new meaning of “sage,” a loaded term in the Confucian tradition.

The poet’s tongue-in-cheek tactic is quite effective. By using the discourse of the established value system to attack the system itself, he makes his stance very clear that success in a public career means nothing to him and all he wants is the simple life of a recluse. It is hard to doubt his sincerity when he talks about the joy of “finding everywhere the Zen of poetry,” which could not be found in the busy world of officialdom. However, when he compares, in line 7, the talking and joking in his leisurely life with the official duties in the Imperial Academy of Compilation (a more literal translation of the line reads, “Talks and jokes are my Imperial Academy of Compilation”), a problem arises: the poet cannot simply relish the joy of his life without comparing his leisure with the burdens of official duties. The last line brings this out more sharply. Granted that the expression “writing commentaries on the wind and the moon” is a cliché connoting the literary elite’s elegant enjoyment of nature, the kinetic details suggested by the two verbs—pi (to correct with a writing brush) and mo (to write or to cross out), meaning “to comment”—are reactivated by their contextual association with the daily routine in the Imperial Academy (line 7). It is amazing that the poet, not a bureaucrat himself in real life, would know so well the thrill of wielding an editorial brush. The wit of the metaphor drives his point home, yet one cannot but wonder why, to illustrate the pleasure of a recluse, the natural beauty of the wind and the moon should be turned into lifeless papers and documents. Does the poet know of no other way to define his life besides keeping an anxious eye on what the social climbers—whom he despises so much—are doing and gloating over their misfortune? Shouldn’t a true recluse, who has nothing to do with the world of fame and gain, be more confident in the value of his quiet and plain life and leave alone the world he considers inferior and undesirable? The semantic field that Qiao Ji carefully builds in “Of Myself” betrays some inner conflict: his unconscious obsession with the value he consciously, and vigorously, rejects.

There is a reason for the perhaps overzealous scrutiny of the inner realities of a self-glorifying recluse. Although eremitism has a long tradition in Chinese literature, the disproportionately great number of songs in this category found in the bulk of sanqu works reflects the awkward situation in which Yuan intellectuals found themselves. Unlike other non-Han peoples before them, who embraced Chinese culture after taking over the control of the heartland of China, the Mongol rulers never really trusted the Han populace. It was very difficult for Confucian scholars to enter, as their Song predecessors had, the civil service, even after the examination system had been restored after a long hiatus.14 For many of the scholarly class, therefore, giving up their ambitions for a public career and settling down into a quiet private life was more a necessity than a choice. It should not be surprising, then, to see the lofty ideal of the recluse’s life complicated by the new social and political realities of the time.

LOVE SONGS

Love songs account for a great portion of the extant sanqu works. Except for their greater boldness in depicting the sensual pleasures of love, which has caused some critics to regard this group of songs as erotic, song poems do not tell us much more about love’s ennui and other boudoir sentiments than the song lyrics of the Huajian tradition. It is in their freshness of poetic expression, reminiscent of the voice of the folk songs of the period of the Great Division (420–581), that song poems stand alone. The following three love songs all show some influence of this folk tradition.

The author of the first song is Guan Hanqing, generally considered the best and certainly the most productive Yuan dramatist. His skill as a playwright can be seen in many of his sanqu works. His description of scenes of parting and longing, when at its best, is often combined with a subtle revelation of the inner lives of the lovers. Guan Hanqing’s keen sense of the living language of his day enabled him to employ different voices to suit different poetic situations.

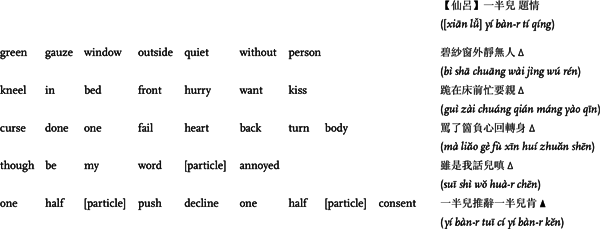

To the Tune “A Half” [xianlü key]: On Love

All was quiet outside the green-gauze window curtain;

2 He knelt down in front of my bed and wanted to get intimate.

I just called him an ingrate and turned my back on him.

4 Though there was annoyance in what I said,

Half of it meant to reject; the other half, consent.

[QYSQ 1:156]

Using his skills as a playwright, the author is able to create a dramatic scene in this poem with economy. The persona does not explain why her lover deserves to be called an “ingrate.” It could be that she is just playing a game with him so as to heighten the pleasure of lovemaking. More probably, her lover has a fickle heart, and she decides that his frivolity should not pass unpunished. Still, she finds it hard to reject him.

The bittersweet experience of love is captured in the dialectic structure at the end. It should be noted that the metrical tune title of the song, “A Half,” requires that any piece written to the tune end with “half …; half …” In fact, “On Love” is selected from a quadruple song sequence, each poem of which deals with one aspect of a complicated love affair. In the first song, the persona tells that her relationship with her “cute wretch sweetheart” (which is itself an excellent example of the “half … half” contradiction) has been “half pain and half fun.” In another, she complains that, because of her lover’s absence, her bed is “half-warm and halfcold,” just like their unstable relationship. In the last song of the sequence, she simply admits that there is no way to know his heart, for “half of it is true while the other half is false.”15

We thus have another example showing how the formal properties of the tune patterns became an integral part of the poetic expression of sanqu works. Statistics support this observation. Of the forty-three extant song poems written by eleven poets to the tune “A Half,” thirty-nine take love and boudoir sentiments as their subjects. Twenty-nine of these bear thematic titles, of which thirteen use the word “love,” seven use “spring” in the amorous sense of the word, and the rest are about the lovelorn sentiments of female personae touched off by fallen flowers or wine, and tears over tokens of love like a kerchief or a letter, and so on. All of them fully exploit the ambivalent “half … half” in the coda, which is stipulated, or, rather, guaranteed, by the tune pattern. Unique as it might be, the case of songs composed to the tune “A Half” provides a wonderful example of the interaction between the thematic content and the formal pattern in the creation of sanqu. On the one hand, the special features of a tune pattern (which originated in music) facilitated and encouraged the use of the pattern for certain topics; on the other, songwriters’ conscious experimentation with the pattern sharpened (or, paradoxically, in less successful cases, stylized or fossilized) the expressive power of such special formal features.

The second love song is by Guan Yunshi (1286–1324), also known by his Uighur name, Sewinch Qaya, the most outstanding of several non-Han sanqu poets, whose achievements compare with those of other poets on an absolutely equal footing. His versatile style enabled him to show distinctive personal traits in his treatment of such conventional subjects as romantic love and the celebration of rustic life. His mastery of language, especially his ability to use individual speeches to enliven dramatic scenes, sets him apart from other sanqu writers.

To the Tune “Clear River, a Prelude” [shuangdiao key]:

If I meet him again,

2 This live message I will deliver to him:

Not that I didn’t want to write,

4 Nor that I ain’t talented and bright—

I circled along the Clear River, but could not find a piece of sky-size paper.

[QYSQ 1:370]

The persona is rehearsing what she will say when she sees “him” again: she did not write to him precisely because she loves him too much! She could not find a piece of paper large enough to contain all her thoughts and feelings.

Does the girl mean that, had she written to him, her love for him would have been less? The logic behind her explanation seems hard to follow, but it makes perfect sense to those in love. The “live message” in line 2 means a spoken “letter.” In the Chinese, the adjective “true” modifies “message.” Not lifeless ink on paper but the living words from the girl’s mouth, delivered in person with charm, are what express her true love. Her true and living “letter” will contain so much love that—if her claim of an attempted purchase of paper is to be believed—its contents would fill up the space between heaven and earth. The girl’s forceful argument is itself ample proof that she is not without talent (line 4). No matter how incredulous her lover might be, one can well imagine that his heart will be tender with the joy of love when he hears her witty explanation.

Although short, “On Separation, No. 4,” is greatly expressive. Every word, every image counts. The “if” at its beginning, for example, tells that what it depicts has not yet happened. It sets a vivid scene of the persona engaged in intense mental communication with her lover at the moment when we come upon her. This attests to the truthfulness of the claim she makes, by implication, later: although she did not write to him, she thinks about him all the time. The “Clear River” in the last line cannot, therefore, be taken as simply a proper noun. It does not matter whether it is the name of a town or a river—the crystal clarity of the image, together with the cleanness of the image of the “sky-size paper,” symbolize the purity, hence chastity, of the persona. The transparency of the two images best exemplifies the song’s unornamented, colloquial language and its straightforward tone.

Like Guan Hanqing, Bai Pu (1226–after 1306), the author of the next love song, was one of the great dramatists of the Yuan. His descriptive song poems are full of bright colors and fresh images, while those on romantic love are alive with dramatic scenes depicted in the language of everyday speech and yet free from the bawdiness frequently seen in similar sanqu.

To the Tune “Spring Song” [zhonglü key]: On Love

Laughing, I block out the silver candlelight with a red sleeve,

2 And forbid my erudite dear one to read books.

Nestling together, we have such fun.

4 Isn’t that only about exams?

Who cares even if you pass?

[QYSQ 1:195]

Although the translation adopts a first-person female voice, there are other ways to read the song, because not a single personal pronoun is used in the original, and it is hard to tell if this is “my” story or “his” or “her” story. Readers can choose to take the first three lines as a third-person narration and the last two lines as a direct quote from the girl, or even to treat the whole piece as a third-person story, with the two concluding lines being the poet’s authorial comment. In any case, no one will miss the message conveyed by this lighthearted love song.

The girl’s “laughing” (depicted by a verb in the original) at the beginning of the song sets the tone for everything that follows. The coquettish laugh makes the girl’s move a loving gesture when she tries to prevent her lover from reading and gives him no excuse to get annoyed. It also brings out the naïveté in her undisguised refutation of his worldly ambitions (lines 4–5) and makes her exhortation sound somewhat pleasing. The charm and sweetness of the female character, which can be palpably felt between the lines, is living proof that the joy of love is far more desirable than success in one’s official career. Judging from the intensity of the love scene in the middle of the song (line 3), the “red sleeve” successfully overcomes the “silver candlelight” (line 1).

The word “silver,” which modifies “candle,” refers either to the color of the candle or of the light it casts or to the material of the candle stand. The only thing that matters is the original meaning of the word: “money.” The blocking out of the silver candle by the red sleeve—whose symbolic meaning is evident—is therefore a metonymy standing for the conflict between two values. The conflict is further complicated by the “books” (line 2) the girl’s lover reads, since it is with them that she must compete for his attention.

The entanglement can be explained by a possible subtext in the poem, a popular saying that enjoys the same status as that of the best-known nursery rhymes in the Chinese language. It reads like a lampoon definition of the civil service examination system: “In books there are thousands of bushels of grain; in books there is no lack of golden mansions; in books there are girls as beautiful as jade.” The argument that concludes the poem takes the same utilitarian approach. Isn’t it just about money and women? Whether one can find such things in books is questionable. But just look at the “red sleeve” that is close at hand, the argument urges; the girl “as beautiful as jade” is right in front of you. Therefore, “who cares even if you pass?” (line 5). The rhetorical question forcefully declares that the “red sleeve” should outweigh the “books.” (Had the question been posed as “who cares even if you fail?” it would have implied that success is the first choice and the “red sleeve” only the comforting compensation one gets after failing the exam.) Seen in this light, besides the alternatives previously mentioned, perhaps there is yet another way to interpret the point of view of “On Love.” The concluding lines could be the exclamation uttered by the male character, who has just been enlightened by the education of love and wants to throw away his books for good.

POEMS OF RAMBUNCTIOUS WIT AND IMPUDENT HUMOR

Any survey of representative sanqu works, no matter how brief, cannot leave out song poems of witticisms and humor. The following poem is by a poet whose hallmark can be easily seen from even a casual glance at the list of his songs: “On Baldness,” “Big Fish,” “Turtle with Green Hair,” “Long-Haired Little Dog,” “Sister Wang Got Beaten in the Bathroom,” and “Fat Couple,” presented in the introductory section as an example of sanqu prosody.

The poet Wang Heqing is known almost exclusively for his raw and exuberant humor. His works on trivial, “vulgar,” and erotic subjects are worthy of inclusion in any survey of sanqu works because they tell about the cultural milieu of their time and are among the best reminders of the genre’s origins in the streets, marketplaces, and entertainment quarters. The following song poem is about a big butterfly.

To the Tune “Heaven in a Drunkard’s Eye” [xianlü key]:

Having emerged from Zhuangzi’s dream,

2 With its two wings mounting on the spring wind,

It empties three hundred gardens in one gulp.

4 Can this be the gallant breed?

How it scares away the flower-chaser bees!

6 With a gentle flap of its wings

It blows the flower vendors to the east side of the bridge.

[QYSQ 1:41]

The song is a parody of the yongwu (poetry on things). Anecdote has it that in the early 1260s there appeared in the grand capital Dadu (present-day Beijing) a gigantic butterfly, and it is believed that the insect gave the poet an excuse to write this song.

Since the poet tells us unmistakably that his butterfly flies directly from Zhuangzi’s famous dream, this is a good place to examine how a seemingly simple sanqu ditty, in the plain language of everyday speech and on a flippant subject that appeals more to the unlettered, can also be charged, or riddled, with allusions, a game any lettered practitioner of traditional classical poetry was good at.

According to Zhuangzi’s famous dream, the philosopher does not know whether he is his own self taking the form of a butterfly in a dream, or a butterfly dreaming that it is Zhuangzi. The original message is that there is no hard-and-fast demarcation between reality and illusion. But, with the passage of time, the butterfly dream has become a fable reminding people of the illusory and ephemeral nature of human life: it is but a dream. The poet borrows the powerful image from Zhuangzi and then remolds it into a clichéd metaphor of a two-winged pleasureseeker (lines 2–3), which itself alludes to numerous “flower-picking” verses exemplifying the Chinese version of carpe diem.16 In this way, Wang Heqing defends with disarming wit the dissolute lifestyle of a womanizer; using the simplistic, yet popular, interpretation of Zhuangzi’s philosophical butterfly, he repeats the adage that life is short and one should pick the flower while it is in blossom.

The image of the butterfly’s “two wings mounting on the spring wind” (line 2)—with the literal “east wind” standing for springtime—does not merely imply the high time for flower picking and emphasize the sense of urgency in the carpe diem motif. The image is also meant to convey the sensual pleasure that the butterfly experiences in its carefree “sweeping” of the flowers. The thrill and sense of freedom in the airborne pose is reminiscent of the well-known image of the Big Roc (Peng bird) in the Zhuangzi, whose two wings are as big as clouds and “mount on the back of the wind” in its “ninety-thousand-mile journey.” The title of the chapter from which this image comes is, as it happens, “Free and Easy Wandering,” and it has become a set phrase used to describe total, unlicensed freedom. The reading of this hidden allusion into the image can be justified with further internal evidence in the song. The big butterfly “shames to death”17 small-time flower chasers, like the honeybees (line 5), with his enviable virile feats (line 3), in exactly the same manner in which Zhuangzi’s Big Roc thwarts the small creatures, like the little doves and quails with his size and movement of heavenly proportions.

Wang Heqing ends the song by making, as if effortlessly and in passing, yet one more allusion to old texts. The “flower vendors” (line 7) allude to a Song dynasty poem, “On Butterfly,” in which flower sellers, urged on by the excitement of the beautiful spring scene, “one after another, rush to the other side of the bridge.”18 In this new context, the role played by the “flower vendors” changes. Can they be those who sell the flower—that is, pimps? By having them fanned across the bridge, the poet seems to allow the big butterfly one more chance to demonstrate his capability “with a gentle flap of its wings” (line 6)—the butterfly requires no help from matchmakers of any kind.

The travesty of the Zhuangzi images carries, in this song, only the positive note. The poem totally transfigures the otherwise disdainful and distasteful playboy image of the butterfly and makes it glow with the luster of the carefree spirit of the original butterfly of the Zhuangzi and the ease and the elegant, condescending air of the Big Roc from the same text. One can label the butterfly “gallant” (fengliu) (line 4), but just as the term fengliu can mean anything from “debauched” and “dissolute” to “talented” and “elegant,” even “heroic,” the butterfly’s true color is open to anybody’s interpretation. Judging from the way the poet presents the butterfly, the apparent uncertainty and puzzlement expressed by the inquisitive phrase nandao (couldn’t we say …? isn’t it …?) at the beginning of line 4 actually betrays his admiration for and wonder at the amazing creature he has created.

The carefree playfulness of the butterfly and the poet’s appreciative attitude toward it thus tell us much about the cultural milieu of the time when the sanqu and its sister genre, the zaju (variety play), flourished. Those who might be surprised by the bold message of this song need only read the following selections from the song suite “Not Giving In to Old Age” to see that the impudence of “On the Big Butterfly” was by no means abnormal in its time. The author of this song suite is none other than Guan Hanqing (whose work is discussed earlier in this chapter), the greatest playwright of the time and a close friend of Wang Heqing:

I’ve plucked every bud hanging over the wall,

and picked every roadside branch of the willow.

The flower I plucked had the softest red petals,

the willows I picked were the tenderest green.

A rogue and a lover, I’ll rely

on my picking and plucking dexterity

’til flowers are ruined and willows wrecked.

I’ve picked and plucked half the years of my life,

a generation entirely spent

lying with willows, sleeping with flowers.

I’m champion rake of all the world,

The cosmic chieftain of rogues.

…………………………………..

You think I’m too old!

Forget it!

I’m the best known lover anywhere….

[QYSQ 1:172]19

The persona is thus an even bigger, and much more brazen, butterfly. He certainly will “shame to death” the small crooks:

You boys are baby bunnies

from sandy little rabbit holes

on grassy hills,

caught in the hunt

for the very first time;

I’m an ol’ pheasant cock plumed with gray;

I’ve been caged,

I’ve been snared,

a tried and true stud

who’s run the course.

[QYSQ 1:172–173]20

The whole song suite, from which the preceding quotes are taken, consists of the libertine’s monologue only, modified by no editorial frame or authorial intrusion. There is no sign in it suggesting that the persona is cast in the light of a villain. On the contrary, from the confidence expressed in his shameless flaunting, one can see that he expects himself to be the object of everybody’s envy and admiration. The image of such an antihero had never been seen in Chinese literature.21

Guan Hanqing’s experience with the zaju partly explains his success in his characterization of the colorful and rambunctious rogue. The format of the sanqu song suite, which is similar to the zaju song suite used as the basic structural unit in the variety plays, also helped by providing him with ample space to elaborate on the topic. Due to the limits of space, only a small portion of the suite has been quoted. So just imagine that the same voice brags and babbles on for five times as long, telling you that the speaker is a “tough old bronze bean” that will not be softened by cooking, or smashed, and that he will not cease his flower picking until he is summoned by the King of Hell.

NOTES

1. James I. Crump, Song-Poems from Xanadu (Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, University of Michigan, 1993), 10.

2. Under Mongol rule in the Yuan, the populace fell into four hierarchical categories. The Mongols were ranked on top, followed by various ethnic groups from the west and the northwest, while northerners of Chinese origin and the subjects of the former Southern Song and their descendants were at the bottom of society and denied opportunities to advance in public service. Some scholars believe that this deprivation of opportunities forced many educated Chinese to turn their attention to popular literature.

3. Crump, Song-Poems from Xanadu, 44. This song is a parody of a well-known love story, said to have taken place in the city of Yuzhang. The poet borrows the names of the two lovers in the story, Mr. Shuang and Miss Su, and reassigns them to the fat couple in the poem.

4. For an explanation of the symbols used here, see p. xxv.

5. For discussions of the prosodies of regulated verse and song lyrics, see chapters 8 and 12.

6. James J. Y. Liu, The Art of Chinese Poetry (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962), 42.

7. Regarding this song, Wayne Schlepp observes that “without verbs there is no question of the poet’s interpreting the scene,” and “the reader feels he can experience [the scene] directly” (San-ch’ü: Its Technique and Imagery [Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1970], 125).

8. For a biographical note on Qiao Ji, see Sui Shusen, Quan Yuan sanqu (Complete Song Poems of the Yuan) (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1964), 1:573.

9. A well-informed and comprehensive discussion of the topic is in James I. Crump, “Tales by Woodsman for the Fisher’s Ear,” in Songs from Xanadu: Studies in Mongol-Dynasty Song-Poetry (San-ch’ü) (Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, University of Michigan, 1983), 81–105.

10. Sui, Quan Yuan sanqu, 1:69.

11. It might not be irrelevant to note here that Hu Zhiyu was one of only a few of those Han Chinese who was able to serve in an office of the Yuan government and rose to a high position.

12. Qiao Ji, “Of Myself,” trans. Sherwin S. S. Fu, in Sunflower Splendor: Three Thousand Years of Chinese Poetry, ed. Wu-chi Liu and Irving Yucheng Lo (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1975), 437–438.

13. The following lines by Liu Yong from the Song dynasty, whose works are discussed in chapter 13, might come close:

Since I fail to soar high,

Why not just indulge in pleasure?

There’s no need to talk about loss and gain—

A talented songwriter

Is no doubt a high minister in plain robe. (QSC 1:57)

14. For a detailed discussion of this issue, see Frederick W. Mote, “China Under Mongol Rule,” in Imperial China, 900–1800 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1999), 474–513, especially 474–477, 504–507.

15. Sui, Quan Yuan sanqu, 1:156.

16. The best example of these verses is in “Jin lü yi” (The Garment Embroidered with Gold Thread), by an anonymous Tang author:

Treasure not the garment embroidered with gold thread,

But seize the young spring day.

Just pick the flower when you see one—

You’ll have no time to regret when there’s none. (QTS 11:8862)

17. There is no translation that can better capture the meaning of the verb at the beginning of line 5 than this rendition by Crump, in Songs from Xanadu, 14.

18. Xie Wuyi (1068–1112), “On Butterfly,” in Quan Song shi (Complete Shi Poetry of the Song) (Beijing: Beijing daxue chubanshe, 1991–1998), 22:14858.

19. Guan Hanqing, “Not Giving In to Old Age,” in An Anthology of Chinese Literature: Beginnings to 1911, trans. and ed. Stephen Owen (New York: Norton, 1996), 729.

20. Guan Hanqing, “Not Giving In to Old Age,” 730.

21. The term “antihero” is used by Owen in his comment on the song suite in Anthology of Chinese Literature, 728.

SUGGESTED READINGS

ENGLISH

Crump, James I. Song-Poems from Xanadu. Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, University of Michigan, 1993.

———. Songs from Xanadu: Studies in Mongol-Dynasty Song-Poetry (San-ch’ü). Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, University of Michigan, 1983.

Johnson, Dale R. Yüan Music Dramas: Studies in Prosody and Structure and a Complete Catalogue of Northern Arias in the Dramatic Style. Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, University of Michigan, 1980.

Liu, Wu-chi, and Irving Yucheng Lo, eds. Sunflower Splendor: Three Thousand Years of Chinese Poetry. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1975.

Mair, Victor H., ed. The Columbia Anthology of Traditional Chinese Literature. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.

Nienhauser, William H., Jr., ed. The Indiana Companion to Traditional Chinese Literature. 2 vols. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984.

Owen, Stephen, trans. and ed. An Anthology of Chinese Literature: Beginnings to 1911. New York: Norton, 1996.

Schlepp, Wayne. San-ch’ü: Its Technique and Imagery. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1970.

———. “Yüan San-ch’ü.” In The Columbia History of Chinese Literature, edited by Victor H. Mair, 370–382. New York: Columbia University Press, 2001.

CHINESE

Cheng Ch’ien 鄭騫. Beiqu xin pu 北曲新譜 (A New Version of Formulas for Northern Songs). Taipei: Yiwen yinshu guan, 1973.

Li Tien-k’uei 李殿魁. Yuan Ming sanqu zhi fenxi yu yanjiu 元明散曲之分析與研究 (An Analytical Study of the Sanqu of the Yuan and Ming Dynasties). Taipei: Zhongguo wenhua xueyuan, 1965.

Sui Shusen 隋樹森. Quan Yuan sanqu 全元散曲 (Complete Yuan Dynasty Sanqu). 2 vols. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1964.

Tang Guizhang 唐圭璋. Yuanren xiaoling gelü 元人小令格律 (The Prosody of Yuan Dynasty Xiaoling). Shanghai: Guji chubanshe, 1981.

Wang Jide 王驥德. Qulü 曲律 (Qu Prosody). Beijing: Zhongguo xuqu chubanshe, 1960.

Wang Li 王力. Qulü xue 曲律学 (Qu Prosody). Beijing: Zhongguo renmin daxue chubanshe, 2004.

Zhao Yishan 趙義山. Yuan sanqu tonglun 元散曲通論 (A General Discussion on Yuan Dynasty Sanqu). Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 2004.

Zhou Deqing 周德清. Zhongyuan yinyun 中原音韻 (Rhymes and Sounds from the Central Plains). Beijing: Zhongguo xiqu chubanshe, 1959.