4

Markets: Guided by an Invisible Hand or Foot?

Adam Smith and his modern disciples see markets working as if they were guided by a beneficent, invisible hand, providing consumers freedom of choice while allocating scarce productive resources and distributing goods and services efficiently. Critics, on the other hand, see markets often working as if they were guided by a malevolent, invisible foot, misrepresenting people’s preferences and misallocating resources to the detriment of social needs. After explaining the basic laws of supply and demand on which economists of all stripes more or less agree, this chapter explains the logic behind these opposing views and points out what determines where the truth lies.

If we leave decisions to markets about what to produce, how to produce it, and how to distribute it, what will happen? Only after we know what markets will do can we decide if they are leading us to do what we would choose to do, or instead, misleading us to do things we would not choose to do.

A market is a social institution in which participants can exchange a good or service with one another on terms they find mutually agreeable. It is part of the institutional boundary of society located in the economic sphere of social life. If a good is exchanged in a “free” market, anyone can play the role of seller by agreeing to provide the good for a particular amount of money. And anyone can play the role of buyer by agreeing to purchase the good for a particular amount of money. The market for the good consists of all the potential buyers and sellers. Our analysis of the market consists of examining all the potential deals these buyers and sellers would be willing to make and predicting which deals will occur and which ones will not. We do this by using four “laws” concerning supply and demand.

The first “law” we use to analyze a market is called the “law of supply” which states that we usually expect the number of units of the good suppliers will offer to sell to increase if the price they receive for the good is higher. There are two reasons for this: (1) At higher prices there are likely to be more suppliers. That is, at a low price some potential suppliers may choose not to play the role of seller at all, but at a higher price they may decide it is worth their while to “enter the market.” So, at higher prices we may have a greater number of individual suppliers. (2) Individual suppliers who were already selling a certain quantity at the lower price may wish to sell more units at the higher price. If the individual seller produces the good under conditions of rising cost a higher price means they can produce more units than before whose cost will be covered by their selling price. Or, if the seller has a fixed amount of the good in hand they may be induced to part with a larger portion of it once the price is higher. In any case, the “law of supply” tells us to expect the quantity of a good potential suppliers will be willing to supply to be a positive function of price.

The second “law” is the “law of demand” which states that we usually expect the number of units of the good demanders will offer to buy to decrease if the price they have to pay is higher. There are two reasons for this as well: (1) At the higher price some who had been buying before may become unable or unwilling to buy any of the good at all and may therefore “drop out of the market.” So at higher prices we may have a smaller number of individual demanders. (2) Individual demanders who continue to buy may wish to buy fewer units at the higher price than they did at the lower price. If the usefulness of the good to an individual buyer decreases the more units they already have, the number of units whose usefulness outweighs the price the buyer must pay will decrease the higher the price the buyer must pay. So the “law of demand” tells us to expect the quantity of a good that potential buyers will be willing to buy to be a negative function of price.

It is important to understand that these so-called “laws” should not be interpreted like the laws of physics. No economist believes that the demand of every individual demander in every market decreases as market price rises, or that the amount every seller offers to supply in every market increases as market price rises. In other words, economists recognize that individuals may well “disobey” these “laws” of supply and demand. Moreover, there may be particular markets that disobey these laws at particular times so that the market supply fails to rise, or market demand fails to fall when market price rises. Markets for stocks and markets for currencies, for example, display annoying propensities to violate the “law of supply” and “law of demand.” A rise in the price of Amazon.com stock can unleash a rush of new buyers who demand more of the stock anticipating further increases in price, and can shrink the supply of sellers who become even more reluctant to part with Amazon.com while its price is increasing. The “laws” of supply and demand do not help us understand market “bubbles” and “crashes.” In 1997 a drop in the price of Thailand’s currency, the baht, triggered the East Asian financial crisis when buyers disappeared from the market not wanting to buy baht while its price was falling, and sellers flooded the market hoping to unload their baht before it fell even farther in value. Clearly the “laws” of supply and demand are not going to help us understand the logic behind currency crises.

We will take up these annoying “anomalies” when participants interpret changes in market prices as signals about what direction a price is moving in when we examine disequilibrating forces than can operate in markets later in this chapter. But for now it is sufficient to note that the “laws” of supply and demand should be interpreted simply as plausible hypotheses about the behavior of buyers and sellers in many markets under many conditions.

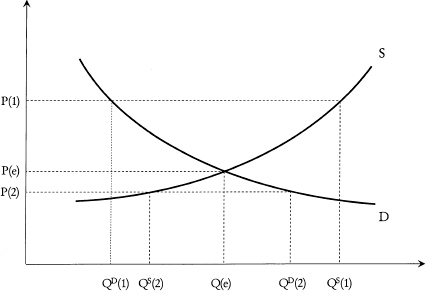

At this point economists invariably use a simple graph to illustrate the laws of supply and demand. We plot market price on a vertical axis and the quantity, or number of units all potential suppliers, in sum total, would be willing to supply in a specified time period on the horizontal axis. According to the law of supply as we go up the vertical axis, at ever higher prices, the number of units all potential suppliers would be willing to supply in a given time period, or the “market supply,” increases. This gives us an upward sloping market supply curve, or in different words a market supply curve with a positive slope. Similarly, we plot market price on a vertical axis and the quantity, or number of units all potential demanders, in sum total, would be willing to buy in a given time period on the horizontal axis. According to the law of demand as we go up the vertical axis, at ever higher prices, the number of units all potential demanders would be willing to buy, or the “market demand,” decreases. This gives us a downward sloping market demand curve, or in different words, a market demand curve with a negative slope.

While these are logically two separate graphs, illustrating two different “laws” or functional relationships, since the vertical axis is the same in both cases, and the horizontal axis is measured in units of the same good supplied or demanded in the same time period, we can combine the two graphs into one with an upward sloping market supply curve and a downward sloping market demand curve. In this most familiar of all graphs in economics one must remember: (1) the independent variable is price, and this is measured (unconventionally) on the vertical axis, while the dependent variable, quantity supplied or demanded by market participants, is measured (unconventionally) on the horizontal axis. (2) When using the market supply curve the horizontal axis measures the number of units of the good all potential suppliers would be willing to sell at different prices. (3) When using the market demand curve the horizontal axis measures the number of units of the good all potential demanders would be willing to buy at different prices. (4) There is an implicit time period buried in the units of measurement on the horizontal axis. For example, the supply and demand curves and the graph will look different if the horizontal axis is measured in bushels of apples supplied and demanded per week than if it is measured in bushels of apples supplied and demanded per month.

The “law of uniform price” says that all units of a good in a market will tend to sell at the same price no matter who are the buyers and sellers. This might seem surprising since some of the deals struck will be between high cost producers and buyers who are very desirous of the good, and some of the deals will be struck between low cost producers and buyers who are luke warm about buying at all. Nonetheless, the law of uniform price says a good will tend to sell at the same price no matter who the seller and buyer may be. The logic of this law can be illustrated by asking what would happen if some buyers and sellers were arranging deals at a lower price than others for the same good. In this case it would pay for anyone to enter the part of the market where the good was selling at the lower price as a buyer and buy up all they could, and then enter the part of the market where deals were being struck at the higher price as a seller to re-sell at a profit. This activity is called “arbitrage,” and in a free market where any who wish can participate as buyers or sellers the activity of arbitrage should drive all deals to be struck at the same price. Where prices are lower arbitrage increases demand and raises price, and where prices are higher arbitrage increases supply and lowers price – driving divergent prices for the same good in a market closer together. Of course, this assumes that “a rose is a rose is a rose is a rose” in the words of one of the great French literati, Gertrude Stein – that is, that there are no qualitative differences between different units of the good. But subject to this assumption, and the energy levels of those who would profit from doing nothing other than buying “cheap” to sell “dear,” economists expect all units of a good that is bought and sold in a “well ordered” market to sell more or less at the same price.

The Micro “Law” of Supply and Demand

I call the last “law” the “micro law of supply and demand” to distinguish it from a different law we study in Chapter 6 that I call the “macro law of supply and demand.” The micro law of supply and demand states that in a free market the uniform market price will adjust until the number of units buyers want to buy is equal to the number of units sellers want to sell, i.e. until quantity demanded is equal to supplied. In terms of the supply and demand graph in Figure 4.1, the micro law of supply and demand says that the market will settle at the price across from where the market supply and demand curves cross, and at the quantity bought and sold beneath where the supply and demand curves cross. This price and this quantity bought and sold are called the equilibrium price and equilibrium quantity, so another way of stating the micro law of supply and demand is: markets will settle at their equilibrium prices, and if left to the free market the quantity of any good that will be produced and consumed will be the equilibrium quantity.

The rationale for the micro law of supply and demand is as follows: Suppose the going market price, P(1), is higher than the equilibrium price, P(e). In this case if we read across from this price to find out how much buyers are willing to buy, QD (1), as compared to how much suppliers are willing to sell, QS (1), we discover from the market demand and supply curves that buyers are not willing to buy all that sellers are willing to sell at this price, QD (1) < QS (1). In other words, at this price there will be excess supply in the market for the good. What can we expect sellers to do? In conditions of excess supply sellers fall into two groups: those who are happily succeeding in selling their goods at P(1) and those who cannot sell all they want and are therefore frustrated. Those who are not able to sell their goods have an incentive to lower their asking price below the going market price in order to move from the group of frustrated sellers to the group of successful sellers, thereby driving the market price down in the direction of the equilibrium price. Buyers also have an incentive to only agree to buy at a price below the going market price when they notice there is excess supply in the market since they know that there are some frustrated sellers out there who should be willing to accept less than the going market price, providing another reason market price should start to fall in the direction of the equilibrium price.

On the other hand, suppose the going market price, P(2), is lower than the equilibrium price, P(e). If we read across from this price to find out how much buyers are willing to buy, QD (2), as compared to how much suppliers are willing to sell, QS (2), we discover from the market demand and supply curves that sellers are not willing to sell all that buyers are willing to buy this price, QS (2) < QD (2). In other words, at this price there will be excess demand in the market for the good. What can we expect buyers to do? In conditions of excess demand buyers fall into two groups: those who are happily able to buy all the good they want at P(2), and those who are not able to buy all they want and are therefore frustrated. Those who are not able to buy all they want have an incentive to raise their offer price above the going market price in order to move from the group of frustrated buyers to the group of successful buyers, thereby driving the market price up in the direction of the equilibrium price. Sellers also have an incentive to only agree to sell at a price above the going market price when they notice there is excess demand in the market since they know that there are some frustrated buyers who should be willing to pay more than the going market price, providing another reason market price should rise in the direction of the equilibrium price.

So for actual market prices above the equilibrium price there are incentives for frustrated sellers to cut their asking price and buyers to offer a lower price, driving the market price down toward the equilibrium price. And as the market price drops the amount of excess supply will decrease, since the law of supply says that supply decreases as price falls and the law of demand says that demand increases as price falls. And for market prices below the equilibrium price there are incentives for frustrated buyers to raise their offer price and for sellers to raise their asking price driving the market price up toward the equilibrium price. And as the market price rises excess demand will decrease, since the law of demand says that demand decreases as price rises and the law of supply says that supply increases as price rises. So according to the micro law of supply and demand, the only stable price will be the equilibrium price because self-interested behavior of frustrated sellers or buyers will lead to changes in price under conditions of both excess supply and excess demand, and only at the equilibrium price is their neither excess supply nor excess demand. This particular kind of self-interested behavior of buyers and sellers – individually rational responses to finding oneself unable to sell or buy all one wants at the going market price – can be thought of as “equilibrating forces” that economists expect to operate in markets. So the micro law of supply and demand can be thought of as a “law” explaining why there should be equilibrating forces at work in markets. We will discover below that market enthusiasts and critics disagree about how strong these “equilibrating forces” are compared to “disequilibrating forces” the micro law of supply and demand does not alert us to that operate alongside equilibrating forces. There are a few things worth noting at this point:

(1) There are different senses in which buyers or sellers are “satisfied.” All buyers would always like to pay a lower price, and all sellers would always like to receive a higher price. So in that sense, neither buyers nor sellers are ever “satisfied” no matter what the price. But when the price is above the equilibrium price, while successful sellers will be pleased, there will be unsuccessful sellers who will be displeased. Moreover, there is something the non-sellers can do about their frustration: they can offer to sell at a lower price. Similarly, when the price is below the equilibrium price, while successful buyers will be pleased, there will be unsuccessful buyers who will be displeased. And what the non-buyers can do about their frustration is offer to pay a higher price.

(2) It is always the case that the quantity bought will be equal to the quantity sold no matter what the price, and whether or not the market is in equilibrium. This follows because every unit that was bought was sold and every unit that was sold was bought! But that is not the same as saying that the quantity demanders want to buy at the going price is equal to the quantity suppliers want to sell at the going price. There is only one price at which the quantity demanded will equal the quantity supplied – the equilibrium price. At all other prices there will be either excess supply or excess demand.

(3) Since not all markets are always in equilibrium, how much will be bought and sold when a market is out of equilibrium? This is where the assumption of non-coercion in our definition of a market comes in: buyers cannot be forced to buy if they don’t want to, and sellers can’t be forced to sell if they don’t want to. When there is excess supply the sellers would like to sell more than the buyers want to buy at the going price. So under conditions of excess supply it is the buyers who have the upper hand, in a sense, and they will determine how much is going to be bought, and therefore sold. In Figure 4.1 when market price is P(1) and there is excess supply buyers will only buy QD (1) and therefore, that is all sellers will be able to sell. When there is excess demand the buyers would like to buy more than the sellers want to sell. So under conditions of excess demand it is the sellers who have the upper hand and will determine how much is going to be sold, and therefore bought. In Figure 4.1 when market price is P(2) and there is excess demand sellers will only sell QS (2) and therefore, that is all buyers will be able to buy.

Elasticity of Supply and Demand

The law of demand just says that as price rises we expect the quantity demanded to fall. It doesn’t say whether demand will fall a lot or a little. If a 1% increase in price leads to more than a 1% fall in quantity demanded, we say that market demand is elastic. If a 1% increase in price leads to less than a 1% fall in quantity demanded, we say that market demand is inelastic. Similarly, the law of supply just says that as price rises we expect the quantity supplied to rise, it doesn’t say whether supply will rise a lot or a little. If a 1% increase in price leads to more than a 1% rise in quantity supplied, we say that market supply is elastic. If a 1% increase in price leads to less than a 1% rise in quantity supplied, we say that market supply is inelastic.

The elasticities of supply and demand allow us to predict how much prices of goods and quantities bought and sold will change when a demand or supply curve shifts. Elasticity also holds the key to how revenues of sellers will be affected by changes in supply. For example, the demand for corn is usually elastic. So when a drought hits the corn belt and the supply curve for corn shifts back to the left, the price will rise and the equilibrium quantity bought and sold will fall. But the percentage fall in sales will be greater than the percentage increase in price because demand for corn is elastic. Since the revenue of corn farmers is simply equal to the market price times the quantity sold, the fact that sales drop by a greater percent than price rises means revenues must fall. On the other hand, the demand for oil is usually inelastic. So if war breaks out in the Middle East and a country such as Iraq, Kuwait, Iran, Libya, or Saudi Arabia is temporarily eliminated as a potential supplier, the world supply curve for oil shifts back to the left, and the price will rise and the equilibrium quantity bought and sold will fall as before. But because demand for oil is inelastic the percentage fall in sales will be less than the percentage increase in price. In this case the revenue of oil suppliers will increase because the rise in price outweighs the drop in sales when supply decreases.

You can use your understanding of elasticity to predict whether more or less involuntary unemployment will result from a rise in the minimum wage, and whether more or fewer shortages in rental units will result from lowering the price ceiling under rent control. Readers should draw a labor market diagram with one “flat” (elastic) labor demand curve and one “steep” (inelastic) labor demand curve where both demand curves cross the labor supply curve at the same point. Where both demand curves cross the supply curve determines the equilibrium wage rate and the equilibrium level of employment. Now draw in a minimum wage above the equilibrium wage and see what happens to employment as buyers (employers) determine the quantity that will be bought and sold in a market with excess supply. Notice that the drop in employment is greater if the demand for labor is more elastic, and smaller if the demand for labor is more inelastic.1 Readers should also draw a diagram for rental units with one “flat” or elastic supply curve and one “steep” or inelastic supply curve where both supply curves cross the demand curve for rental units at the same point. Where both supply curves cross the demand curve determines the equilibrium rental price and the equilibrium quantity of rental units. Now draw a price ceiling below the equilibrium price and see what happens to the supply of rental units when suppliers determine the amount that will be sold and bought in a market with excess demand. Notice that the shortage of rental units is greater if the supply curve for rental units is more elastic, and smaller if the supply is more inelastic.

The principal factors that determine the elasticity of market demand are the availability and closeness of substitutes for the good, and the organization and bargaining power of potential buyers. The principal factors that determine the elasticity of market supply are the time period under consideration, the mobility of productive factors into and out of the industry, and the organization and bargaining power of potential sellers.

The Dream of a Beneficent Invisible Hand

Adam Smith noticed something strange but wonderful about free markets. He saw competitive markets as a kind of beneficent, “invisible hand” that guided “the private interests and passions of men” in the direction “which is most agreeable to the interest of the whole society.” Smith expressed this view in perhaps the most widely quoted passage in all of economics in The Wealth of Nations published in 1776:

Every individual necessarily labours to render the annual revenue of the society as great as he can. He generally, indeed, neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it. He intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for the society that it was no part of it. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it. . . . It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their self-interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity, but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our necessities, but of their advantages.

In the words of Robert Heilbroner:

Adam Smith’s laws of the market are basically simple. They show us how the drive of individual self-interest in an environment of similarly motivated individuals will result in competition; and they further demonstrate how competition will result in the provision of those goods that society wants, in the quantities that society desires.2

But how does this miracle happen?

Suppose consumers’ taste for apples increases and their taste for oranges decreases – for whatever reason. Assuming consumers know best what they like, how would we want the economy to respond to this new situation? If there were an omniscient, beneficent God in charge of the economy she would shift some of our scarce productive resources – land, labor, fertilizer, etc. – out of orange production and into apple production. What would a system of free markets do? These changes in consumer tastes would shift the market demand curve for apples out to the right indicating that consumers would now like to buy more apples than before at each and every price of apples. And they would shift the market demand curve for oranges back to the left, indicating that consumers are now only willing to buy fewer oranges than before at each and every price of oranges. This would lead to excess demand for apples and excess supply of oranges at their old equilibrium prices. The micro law of supply and demand would drive the price of apples up until the excess demand for apples was eliminated and the price of oranges down until the excess supply of oranges was eliminated. At the new higher price of apples the law of supply tells us former apple growers, and any new ones drawn into the industry by the higher price of apples, would increase production of apples by purchasing more land, labor, fertilizer, etc. At the new lower price of oranges the law of supply tells us orange growers would decrease their production of oranges by using less land, labor, and fertilizer, etc. to grow oranges. Bingo! As if guided by an invisible hand, without anyone thinking or planning at all, the free market does what a beneficent God would have done for us!

Or, suppose agronomists develop a new strain of apple that can be grown with less land between the trees than before. This is a technical change that reduces the amount of a scarce productive resource it takes to grow apples compared to the past. An omniscient, beneficent God would have consumers buy more apples and fewer oranges now that apples are less socially costly than previously. What will free markets do? The cost-reducing change in apple growing technology will shift the market supply curve for apples out to the right because apple growers can cover the cost of growing more apples than before at each and every price, producing excess supply of apples at the old equilibrium price. The micro law of supply and demand will lower apple prices until the excess supply is eliminated and we reach the new equilibrium in the apple market. And the law of demand tells us that consumers will buy more apples at the lower price. Meanwhile, over in the orange market, the fall in the price of apples leads some fruit buyers to substitute apples for oranges which shifts the demand curve for oranges back to the left indicating that fewer oranges will be demanded at each and every price of oranges now that the price of apples is lower, creating excess supply in the orange market. This will lead to a fall in the price of oranges and lower levels of orange production. Bingo! The free market will bring about an increase in apple production and consumption and a decrease in orange production and consumption when the social cost of producing apples decreases relative to the social cost of producing oranges – just what we would have wanted to happen.

We can combine Figure 2.3: The Efficiency Criterion (p. 35) and Figure 4.1: Supply and Demand (p. 85) to see what Smith’s conclusion that markets harness individually rational behavior to yield socially rational outcomes amounts to. According to the micro law of supply and demand, the market outcome will be the equilibrium outcome, and the number of apples produced and consumed can be found directly below where the market supply curve crosses the market demand curve. According to the efficiency criterion, the optimal number of apples to produce and consume can be found directly below where the marginal social cost curve crosses the marginal social benefit curve. So the market outcome will yield the socially efficient outcome if and only if the market supply curve coincides with the MSC curve and the market demand curve coincides with the MSB curve. Another way to put it is that if and only if market supply closely approximates marginal social cost and market demand closely approximates marginal social benefits will free market outcomes be socially efficient outcomes.

But do market supply and demand reasonably express marginal social costs and benefits? That is one way to see the debate between those who see market allocations as being guided by an invisible hand versus those who see them as being misguided by an invisible foot. If market supply and demand closely approximate true marginal social costs and benefits then the individually rational behavior of buyers and sellers and the workings of the micro law of supply and demand would be working in the social interest because they would be driving production and consumption of goods and services toward socially efficient levels. Moreover, whenever conditions changed social costs or benefits these equilibrating forces would move us to the new socially efficient outcome. In other words, markets would yield efficient reallocations of scarce productive resources. On the other hand, if there are significant discrepancies between market supply and marginal social costs, and/or market demand and marginal social benefits, individually rational behavior of buyers and sellers and the micro law of supply and demand work against the social interest by driving us to produce too little of some goods and too much of others. In other words, by relying on market forces we would consistently get inefficient allocations of productive resources.

Mainstream and political economists agree on one part of the answer before parting company. They agree that what market supply captures and represents are the costs borne by the actual sellers of goods and services; and what market demand represents are the benefits enjoyed by the actual buyers of goods and services. We call these private costs and private benefits. A rational buyer will keep buying more of a good as long as the private benefit to her of an additional unit is at least as great as the price she must pay for it. In other words, her marginal private benefit curve is her individual demand curve. Since the market demand curve is simply the summation of all individual demand curves, the market demand curve is simply the sum of all marginal private benefit curves. A rational seller will keep selling more of a good as long as the cost to her of producing another unit of output is no greater than the price she will get from selling it. In other words, her marginal private cost curve is her individual supply curve. Since market supply is simply the summation of all individual supply curves, the market supply curve is simply the sum of all marginal private cost curves. So the question becomes when do private costs and benefits differ from social costs and benefits?

In fairness to Adam Smith, the distinction between private and social costs and benefits was not clear in his life time. Smith, and the “classical economists” who lived and wrote after him as well, conflated social and private costs and benefits and never asked if anyone other than the seller bore part of the cost of increased production, or anyone other than the buyer enjoyed part of the benefit of increased consumption of different kinds of goods and services. The modern terminology for differences between social and private costs of production is a production externality. And the name for the difference between social and private benefits from consumption is a consumption externality. These external effects can be negative if someone other than the seller suffers a cost associated with production, in which case social costs exceed private costs, or if someone other than the buyer is adversely affected by the buyer’s consumption, in which case private benefits exceed social benefits. Or external effects can be positive if the private costs of production exceed the social costs or social benefits of consumption exceed private benefits. Adam Smith’s vision of the market as a mechanism that successfully harnesses individual desires to the social purpose of using scarce productive resources efficiently hinges on the assumption that external effects are insignificant. And, indeed, this is precisely the un-emphasized assumption that lies behind the mainstream conclusion that markets are remarkable efficiency machines that require little social effort on our part. In fact, the mainstream view today is a strident echo of Adam Smith’s conclusion that the only “effort” required on our part is the “effort” to resist the temptation to tamper with the free market and simply laissez faire.

The Nightmare of a Malevolent Invisible Foot

Mainstream economic theory teaches that the problem with externalities is that the buyer or seller has no incentive to take the external cost or benefit for others into account when deciding how much of something to supply or demand. And mainstream theory teaches that the problem with public goods is that nobody can be excluded from benefiting from a public good once anyone buys it, and therefore everyone has an incentive to “free ride” on the purchases of others rather than reveal their true willingness to pay for public goods by purchasing them in the marketplace. In other words, mainstream economics concedes that the market will lead to inefficient allocations of scarce productive resources when public goods and externalities come into play because important benefits or costs go unaccounted for in the market decision-making procedure. If anyone cares to listen, standard economic theory predicts that if decisions are left to be decided by market forces we will produce too much of goods whose production and/or consumption entail negative externalities, too little of goods whose production and/or consumption entail positive externalities, and much too little, if any, public goods. We can see the problem of negative externalities by looking at the automobile industry, and the problem of public goods by considering pollution reduction.

Externalities: The Auto Industry

The micro law of supply and demand tells us how many cars will be produced and consumed if we leave the decision to the free market. The price of cars will adjust until there is neither excess supply nor excess demand at which point the “equilibrium” number of cars will be produced and consumed. The question is whether this will be more, less, or the same number of cars that is socially efficient, or optimal to produce and consume. As we saw, the socially efficient level of auto production and consumption is where the MSB curve crosses the MSC curve. If the market supply curve for cars coincides with the MSC curve for cars, and if the market demand curve for cars coincides with the MSB curve for cars, the market outcome will be the efficient outcome. Otherwise, it will not be.

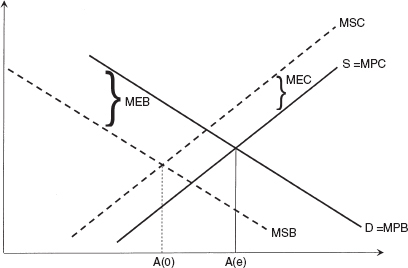

Let us assume that the market supply curve for cars does a reasonably good job of approximating the marginal private costs the makers and sellers of cars incur. If they can get a price for a car that is something above what it costs them to make it, presumably they will produce and sell the car. So the market supply curve, S, equals the marginal private cost curve for making cars, MPC: S = MPC. But if there are costs to external parties above and beyond the costs of inputs car makers must pay for, there is no reason to expect the sellers of cars to take them into account. So if the corporations making cars in Detroit also pollute the air in ways that cause acid rain, the costs that take the form of lost benefits to those who own, use, or enjoy forests and lakes in Eastern Canada and the United States will not be taken into account by those who make the decisions about how many cars to produce. Nevertheless, along with the cost of steel, rubber and labor – which are costs borne by car manufacturers – the costs of acid rain are part of the social costs of making cars even if they are not borne by car makers. To the cost of steel, rubber, and labor that comprise the private costs of making a car must be added the damage from acid rain that occurs when we make a car if we are to have the full cost to society of making a car. In other words, the marginal social cost of making a car, MSC, is equal to the marginal private cost of making the car, MPC, plus the marginal external costs associated with making the car, MEC: MSC = MPC + MEC. Since MEC is positive for automobile production marginal social costs always exceed marginal private costs, which means the marginal social cost curve for producing cars lies above the marginal private cost curve for cars, which is roughly equal to the market supply curve for cars: MSC = MPC + MEC = S + MEC with MEC > 0.

When car buyers consider whether or not to purchase a car they presumably compare the benefit they expect to get in the form of ease and speed of transportation with the price they will have to pay out of their limited income. If the private benefit exceeds the price, they will buy the car, and if it does not, they won’t. This means the market demand curve, D, represents the marginal private benefit curve from car consumption, MPB, reasonably well: D = MPB. But I am not the only person affected when I “consume” my car. When I drive my car the exhausts add to the greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and contribute to global warming. When I drive from the suburbs through inner city neighborhoods I contribute to urban smog, noise pollution, and congestion. In other words, when I consume a car there are others who suffer negative benefits which means that the social benefit of consuming another car is less than the private benefit of consuming another car. So even if the market demand curve for cars reasonably represents the marginal private benefits of car consumption, it overestimates the marginal social benefits of car consumption because it ignores the negative impact of car consumption on those not driving them. The marginal social benefit from consuming another car, MSB, is equal to the marginal private benefit to the car buyer, MPB, plus the external benefits to others, MEB: MSB = MPB + MEB. But in the case of car consumption the marginal external “benefits,” MEB, are negative. This implies that the marginal social benefit curve lies somewhere below the market demand curve for automobiles: MSB = MPB + MEB = D + MEB with MEB < 0.

Figure 4.2 Inefficiencies in the Automobile Market

But as can be seen in Figure 4.2, if the MSC curve lies above the market supply curve, and the MSB curve lies below the market demand curve for cars, MSC and MSB will cross to the left of where the market supply and demand curves cross. Therefore the socially efficient, or optimal level of automobile production and consumption, A(0), will be less than the equilibrium level of production and consumption, A(e), which the micro law of supply and demand will drive us toward. In other words, the market will lead us to produce and consume more cars than is socially efficient, or optimal. The market will produce too many cars because sellers and buyers decide how many cars to produce and consume and they have no reason to take anything other than the costs and benefits to them into account. They have no incentive to consider the external effects of producing and consuming cars. In fact, they have good reason to ignore these external effects because taking them into account would make them individually worse off. Not surprisingly we discover that if decision makers ignore negative consequences of doing something – in this case the negative external effects of car production and consumption on people other than the car producer and buyer – they will decide to do too much of it – in this case they will decide to produce and consume too many cars.

External effects are notoriously hard to measure in market economies. This is of great significance since their magnitude tells us how inefficient a market will be, and how large a pollution tax must be to correct the inefficiency. In a 1998 report the Center for Technology Assessment estimated that when external effects are taken into account the true social cost of a gallon of gas consumed in the US might have been as high as $15. In that same year when I filled up my car in St. Mary’s County Maryland I paid a little over one dollar a gallon. That price already included some hefty federal and state gasoline taxes, but obviously they were not nearly hefty enough!

Public Goods: Pollution Reduction

A public good is a good produced by human economic activity that is consumed, to all intents and purposes, by everyone rather than by an individual consumer. Unlike a private good such as underwear that affects only its wearer, public goods like pollution reduction affect most people. In different terms, nobody can be excluded from “consuming” – or benefiting from the existence of the public good. This is not to say that everyone has the same preferences regarding public goods any more than people have the same preferences for private goods. I happen to prefer apples to oranges, and I value pollution reduction more than I value so-called national defense. There are others who place greater value on national defense than they do on pollution reduction, just as there are others who prefer oranges to apples. But unlike the case of apples and oranges where those who prefer apples can buy more apples and those who like oranges more can buy more oranges, all US citizens have to “consume” the same amount of federal spending on the military and federal spending on pollution reduction. We cannot provide more military spending for the US citizens who value that public good more, and more pollution reduction for the US citizens who value the environment more. Whereas different Americans can consume different amounts of private goods, we all must live in the same “public good world.”

What would happen if we left the decision about how much of our scarce productive resources to use to devote to producing public goods to the free market? Markets only provide goods for which there is what we call “effective demand,” that is, buyers willing and able to put their money where their mouth is. But what incentive is there for a buyer to pay for a public good? First of all, no matter how much I value the public good, I only enjoy a tiny fraction of the overall, or social benefit that comes from having more of it since I cannot exclude others who do not pay for it from benefiting as well. In different terms: Social rationality demands that an individual purchase a public good up to the point where the cost of the last unit she purchased is as great as the benefits enjoyed by all who benefit, in sum total, from her purchase of the good. But it is only rational for an individual to buy a public good up to the point where the cost of the last unit she purchased is as great as the benefit she, herself enjoys from the good. When individuals buy public goods in a free market they have no incentive to take the benefits others enjoy when they purchase public goods into account when they decide how much to buy. Consequently they “demand” far less than is socially efficient, if they purchase any at all. In sum, market demand – the sum of all individual demands – will grossly under represent the marginal social benefit of public goods.

Another way to see the problem is to recognize that each potential buyer of a public good has an incentive to wait and hope that someone else will buy the public good. A patient buyer can “free ride” on others’ purchases since non-payers cannot be excluded from benefiting from public goods. But if everyone is waiting for someone else to plunk down their hard earned income for a public good, nobody will demonstrate “effective demand” for public goods in the market place. Free riding is individually rational in the case of public goods – but leads to an effective demand for public goods that grossly underestimates their true social benefit. In Chapter 5 we explore this logic formally in “the public good game.”

What prevents a group of people who will benefit from a public good from banding together to express their demand for the good collectively? The problem is there is an incentive for people to lie about how much they benefit. If the associations of public good consumers are voluntary, no matter how much I truly benefit from a public good, I am better off pretending I don’t benefit at all. Then I can decline membership in the association and avoid paying anything, knowing full well that I will, in fact, benefit from its existence nonetheless. Even if membership is not voluntary there is a problem if contributions are based on how much members declare they benefit. In this case it would be in the interest of every member of the coalition to underreport how much they benefit, and difficult to know when to challenge a member’s declaration since we know not all truly do benefit to the same extent. So even if the coalition of consumers does include all who benefit, if its effective demand is based on member’s individually rational underrepresentations, it will still underrepresent the true social benefits people enjoy from the public good, and consequently demand less than the socially efficient, or optimal amount of the public good.

In sum, because of what economists call the “free rider” incentive problem and the “transaction costs” of organizing and managing a coalition of public good consumers, market demand predictably under represents the true social benefits that come from consumption of public goods. If the production of a public good entails no external effects so that the market supply curve accurately represents the marginal social costs of producing the public good, then since market demand will lie considerably under the true marginal social benefit curve for the public good, the market equilibrium level of production and consumption will be significantly less than the socially efficient level. In conclusion, if we left it to the free market and voluntary associations precious little, if any, of our scarce productive resources would be used to produce public goods no matter how valuable they really were. As Robert Heilbroner succinctly put it: “The market has a keen ear for private wants, but a deaf ear for public needs.” Which is why, when the need for some particular public good is painfully obvious and failure to provide it would be seriously dysfunctional, even governments most devoted to free market principles have found it necessary to substitute a completely different decision-making procedure for the market mechanism – the “draft!” In effect the government “drafts” everyone into the public good consumer coalition and collects taxes from members to pay for the public goods according to some formula not based on what members report they would be willing to pay.

The fact that pollution reduction is a public good has important implications for green consumerism in market economies. There are a number of cheap detergents that get my wash very white but cause considerable water pollution. “Green” detergents, on the other hand, are more expensive and leave my whites more gray than white, but cause less water pollution. Whether or not I end up making the socially responsible choice, because pollution reduction is a public good the market provides too little incentive for me to make the socially efficient choice. My own best interests are served by weighing the disadvantage of the extra cost and grayer whites to me against the advantage to me of the diminution in water pollution that would result if I use the green detergent. But presumably there are many others besides me who also benefit from the cleaner water if I buy the green detergent – which is precisely why we think of “buying green” as socially responsible behavior. Unfortunately the market provides no incentive for me to take their benefit into account. Worse still, if I suspect others may consult only their own interest when they choose which detergent to buy, i.e. if I think they will ignore the benefits to me and others if they choose the green detergent, by choosing to take their interest into account and consuming green myself I risk not only making a choice that was detrimental to my own interest, I risk being played for a sucker as well.3

This is not to say that many people will not choose to “do the right thing” and “consume green” in any case. Moreover, there may be incentives other than the socially counterproductive market incentives that may overcome the market disincentive to consume green. The fact that I am a member of several environmental organizations and fear I would be ostracized if a fellow member saw me with a polluting detergent in my shopping basket in the checkout line is apparently a powerful enough incentive in my own case to lead me to buy a green detergent despite the market disincentive to do so. (Admittedly I have only a slight preference for white over gray clothes, and who knows how long I will hold out if the price differential increases!) But the point is that because pollution reduction is a public good, market incentives are perverse, i.e. lead people to consume less “green” and more “dirty” (dirty environment, not clothes) than is socially efficient. The extent to which people ignore the perverse market incentives and act on the basis of concern for the environment, concern for others, including future generations, or in response to non-market, social incentives such as fear of ostracism is important for the environment and the social interest, but does not make the market incentives any less perverse.

The Prevalence of External Effects

In face of these concessions – markets misallocate resources when there are externalities and public goods – how do market enthusiasts continue to claim that markets allocate resources efficiently – as if guided by a beneficent invisible hand? The answer lies in an assumption that is explicit in the theorems of graduate level microeconomic theory texts but only implicit in undergraduate textbooks and in the advice of most economists. The fundamental theorem of welfare economics states that if all markets are in equilibrium the economy will be in a Pareto optimal state only if there are no external effects or public goods. The assumption that there are no public goods or external effects is explicit in the statement of the theorem that is the modern incarnation of Adam Smith’s two hundred year-old vision of an invisible hand – because otherwise the theorem would be false! Since everyone knows there are externalities and public goods in the real world, the conclusion that markets allocate resources reasonably efficiently in the real world therefore rests on the assumption that external effects and public goods are few and far between. This assumption is usually unstated, and its validity has never been demonstrated through empirical research. It is a presumption implicit in an untested paradigm that lies behind mainstream economic theory – a paradigm that pretends that the choices people make have little effect on the opportunities and wellbeing of others.

If we replace the implicit paradigm at the basis of mainstream economics with one that sees the world as a web of human interaction where people’s choices often have far reaching consequences for others, both now and in the future, the presumption that external effects and public goods are the exception rather than the rule is reversed. Since political economists have long seen the world in just this way, and everything we have learned about the relation between human choices and ecological systems over the past thirty years reinforces this vision of interconnectedness, there is every reason for political economists to expect external and public effects to be the rule rather than the exception. What is surprising is that so few political economists have recognized the far reaching implications of their own beliefs when it comes to assessing the efficiency of markets. One stellar exception is E. K. Hunt. In an article remarkable for its lack of impact on other political economists when published in June 1973 in the Journal of Economic Issues, Hunt stated the “reverse” assumption as follows:

The Achilles heel of welfare economics [as practiced by mainstream pro-market economists] is its treatment of externalities. . . . When reference is made to externalities, one usually takes as a typical example an upwind factory that emits large quantities of sulfur oxides and particulate matter inducing rising probabilities of emphysema, lung cancer, and other respiratory diseases to residents downwind, or a strip-mining operation that leaves an irreparable aesthetic scar on the countryside. The fact is, however, that most of the millions of acts of production and consumption in which we daily engage involve externalities. In a market economy any action of one individual or enterprise which induces pleasure or pain to any other individual or enterprise . . . constitutes an externality. Since the vast majority of productive and consumptive acts are social, i.e., to some degree they involve more than one person, it follows that they will involve externalities. Our table manners in a restaurant, the general appearance of our house, our yard or our person, our personal hygiene, the route we pick for a joy ride, the time of day we mow our lawn, or nearly any one of the thousands of ordinary daily acts, all affect, to some degree, the pleasures or happiness of others. The fact is . . . externalities are totally pervasive. . . . Only the most extreme bourgeois individualism could have resulted in an economic theory that assumed otherwise.

If the social effects of production and consumption frequently extend beyond the sellers and buyers of those goods and services, as Hunt argues above, and if these external effects are not insignificant, markets will frequently misallocate resources leading us to produce too much of some goods and too little of others. By ignoring negative external effects markets lead us to produce and consume more of goods like automobiles than is socially efficient. By ignoring positive external effects markets lead us to consume less of goods like tropical rain forests that recycle carbon dioxide and thereby reduce global warming than is socially efficient – instead we clear cut them or burn them off to pasture cattle. And while markets provide reasonable opportunities for people to express their preferences for goods and services that can be enjoyed individually with minimal “transaction costs,” they do not provide efficient, or what economists call “incentive compatible” means for expressing desires for goods that are enjoyed, or consumed socially, or collectively – like public space and pollution reduction. Instead, markets create perverse free rider disincentives for those who would express their desires for public goods individually, and pose daunting transaction costs for those who attempt to form a coalition of beneficiaries. In other words, markets have an anti-social bias.

Worse still, markets provide powerful incentives for actors to take advantage of external effects in socially counterproductive ways, and even to magnify external effects or create new ones. Increasing the value of goods and services produced, and decreasing the unpleasantness of what we have to do to get them, are two ways producers can increase their profits in a market economy. And competitive pressures will drive producers to do both. But maneuvering to appropriate a greater share of the goods and services produced by externalizing costs and internalizing benefits without compensation are also ways to increase profits. Competitive pressures will drive producers to pursue this route to greater profitability just as assiduously. Of course the problem is, while the first kind of behavior serves the social interest as well as the private interests of producers, the second kind of behavior does not. Instead, when buyers or sellers promote their private interests by externalizing costs onto those not party to the market exchange, or internalizing benefits without compensation, their “rent seeking behavior” introduces inefficiencies that lead to a misallocation of productive resources and consequently decreases the value of goods and services produced.

Questions market admirers seldom ask are: Where are firms most likely to find the easiest opportunities to expand their profits? How easy is it to increase the quantity or quality of goods produced? How easy is it to reduce the time or discomfort it takes to produce them? Alternatively, how easy is it to enlarge one’s slice of the economic pie by externalizing a cost, or by appropriating a benefit without compensation? In sum, why should we assume that it is infinitely easier to expand profits by productive behavior than by rent seeking behavior? Yet this implicit assumption is what lies behind the view of markets as efficiency machines.

Market enthusiasts fail to notice that the same feature of market exchanges primarily responsible for small transaction costs – excluding all affected parties but two from the transaction – is also a major source of potential gain for the buyer and seller. When the buyer and seller of an automobile strike their convenient deal, the size of the benefit they have to divide between them is greatly enlarged by externalizing the costs onto others of the acid rain produced by car production, and the costs of urban smog, noise pollution, traffic congestion, and greenhouse gas emissions caused by car consumption. Those who pay these costs, and thereby enlarge car maker profits and car consumer benefits, are “easy marks” for car sellers and buyers because they are geographically and chronologically dispersed, and because the magnitude of the effect on each of them is small and unequal. Individually they have little incentive to insist on being party to the transaction. Collectively they face transaction cost and free rider obstacles to forming a voluntary coalition to represent a large number of people – each with little, but different amounts at stake.

Moreover, the opportunity for socially counterproductive rent seeking behavior is not eliminated by making markets perfectly competitive or entry costless, as is commonly assumed. Rent seeking at the expense of buyers or sellers may be eliminated by making markets more competitive, i.e. increasing the number of sellers for buyers to choose from and the number of buyers for sellers to choose from. But even if there were countless perfectly informed sellers and buyers in every market, even if the appearance of the slightest differences in average profit rates in different industries induced instantaneous self-correcting entries and exits of firms, even if every economic participant were equally powerful and therefore equally powerless – in other words, even if we embrace the full fantasy of market enthusiasts – as long as there are numerous external parties with small but unequal interests in market transactions, those external parties will face greater transaction costs and free rider obstacles to an effective representation of their collective interest than faced by the buyer and seller in the exchange. And it is this unavoidable inequality that makes external parties easy prey to rent seeking behavior on the part of buyers and sellers.

Even if we could organize a market economy so that buyers and sellers never faced a more or less powerful opponent in a market exchange, this would not change the fact that each of us has smaller interests at stake in many transactions in which we are neither the buyer nor seller. Yet the sum total interest of all external parties can be considerable compared to the interests of the buyer and the seller. It is the transaction cost and free rider problems of those with lesser interests that create an unavoidable inequality in power, which, in turn, gives rise to the opportunity for individually profitable but socially counterproductive rent seeking on the part of buyers and sellers even in the most competitive markets. A sufficient condition for the opportunity to profit in socially counterproductive ways from maneuvering, rent seeking, or cost shifting behavior is that each one of us has diffuse interests that make us affected external parties to many exchanges in which we are neither buyer nor seller – no matter how competitive markets may be.

But socially counterproductive rent seeking behavior is not only engaged in at the expense of parties external to market exchanges. The real world bears little resemblance to a game where all buyers and sellers are equally powerful, in which case it would be pointless for sellers or buyers to try to take advantage of one another. In the real world it is often easier for powerful firms to increase profits by lowering the prices they pay less powerful suppliers and raise the prices they charge powerless consumers than it is to search for ways to increase the quality of their products. In the real world there are consumers with little information, time, or means to defend their interests. There are small, capital poor, innovative firms for giants like IBM, Microsoft, and Google to buy up instead of tackling the hard work of innovation themselves. There are common property resources whose productivity can be appropriated at little or no cost to be over exploited at the expense of future generations. And finally, there is a government run by politicians whose careers rely largely on their ability to raise campaign money, begging to be plied for tax dodges and corporate welfare programs financed at taxpayer expense. In other words, in the real world where buyers and sellers are usually not equally powerful, the most effective profit maximizing strategy is often to out maneuver less powerful market opponents and expand one’s slice of the pie at their expense rather than work to expand the economic pie.

To the extent that consumer preferences are endogenous the degree of misallocation that results from uncorrected external effects in market economies will increase, or “snowball” over time. As people adjust their preferences to the biases created by external effects in the market price system, they will increase their preference and demand for goods whose production and/or consumption entails negative external effects, but whose market prices fail to reflect these costs and are therefore lower than they should be; and they will decrease their preference and demand for goods whose production and/or consumption entails positive external effects, but whose market prices fail to reflect these benefits and are therefore higher than they should be. While this reaction, or adjustment is individually rational it is socially irrational and inefficient since it leads to even greater demand for the goods that market systems tend to overproduce, and even less demand for the goods that market systems tend to underproduce. As people have greater opportunities to adjust over longer periods of time, the degree of inefficiency in the economy will grow, or “snowball.”4

Nobody knows where the equilibrium price in a market is. What the micro law of supply and demand says is that self-interested behavior on the part of frustrated sellers when there is excess supply because the actual price is higher than the equilibrium price, and self-interested behavior on the part of frustrated buyers when there is excess demand because market price is below the equilibrium price, will tend to move markets toward their equilibria. But as long as a market is out of equilibrium the quantity bought and sold will be less than the quantity that would be bought and sold if the market were in equilibrium. Since the equilibrium quantity is the same as the socially efficient quantity to produce and consume in absence of external effects, this means markets do not yield efficient outcomes when they are out of equilibria even in absence of external effects. So the first problem is the slower markets equilibrate the more inefficiency we will endure while they do.5

The second problem is if market participants interpret changes in prices as signals about further changes in prices it is unlikely they will obey the “laws” of supply and demand. If I believe that even though the price of apples just rose, any further change in the price of apples is just as likely to be down as up, that is, if I do not interpret the rise in price as a signal that the price is rising, I will probably demand fewer apples at the new higher price as the law of demand predicts. But if I think that because the price just rose it is more likely to go up than down the next time it changes, I should buy more apples now that I think the chances are greater than I thought before that the price of apples will rise. If I want to consume apples I should buy more apples now before they become even more expensive later. And even if I don’t want to consume apples myself, I should buy more now and sell them tomorrow when the price is even higher. Similarly, if sellers in a market interpret price changes as signals of what direction prices are headed in, they should offer to sell more when the price falls and sell less when it rises, the law of supply notwithstanding.6 In this case, when actual buyers’ behavior is represented by an upward sloping demand curve and actual sellers’ behavior is represented by a downward sloping supply curve, self-interested behavior on the part of frustrated buyers when there is excess demand will raise a price that is higher than the equilibrium price, not lower it. And self-interested behavior on the part of frustrated sellers will lower a price that is lower than the equilibrium price, not raise it. In other words, there will be disequilibrating forces in the market pushing it farther away from equilibrium, not toward it.

A rising price that becomes, at least temporarily, a self-fulfilling prophesy is commonly called a market “bubble,” and a falling price that becomes a self-fulfilling prophesy is often called a market “crash.” This kind of disequilibrating dynamic occurs more often than market enthusiasts like to admit. Until recently enthusiasts liked to pretend that bubbles and crashes were few and far between and largely confined to financial markets – currency markets, stock markets, bond markets, etc. – with little effect on normal people. But the prominent role played by the bubble and crash in the US housing market in the latest economic crisis, and similar housing bubbles and crashes in Spain and Ireland, have made it increasingly difficult to pretend that market disequilibria are not a serious problem. Moreover, even when they occur in financial markets where most of us are not players they often have disastrous effects on what is called the “real economy,” i.e. on employment, investment, and production and consumption of goods and services, as model 9.2 demonstrates. Finally, there can be a different kind of disequilibrating dynamic that operates between markets that are connected in a particular way. In Chapter 6 we will see how the market for labor and the market for goods in general can interact in a way that pushes both markets farther away from their equilibrium. Recognizing this particular disequilibrating dynamic was one of Keynes’ greatest insights, and allowed him to explain why production and employment may keep dropping in a recession even though there are more and more workers willing to work, if only someone would hire them, and more and more employers anxious to produce goods, if only someone would buy them.

Conclusion: Market Failure Is Significant

In sum, convenient deals with mutual benefits for buyer and seller should not be confused with economic efficiency. When some kinds of preferences are consistently underrepresented because of transaction cost and free rider problems, when consumers adjust their preferences to biases in the market price system and thereby aggravate those biases, and when profits can be increased as often by externalizing costs onto parties external to market exchanges as from productive behavior, theory predicts free market exchange will often result in a misallocation of scarce productive resources. Theory tells us free market economies will allocate too much of society’s resources to goods whose production or consumption entail negative external effects, and too little to goods whose production or consumption entail positive external effects, and there is every reason to believe the misallocations are significant. When markets are less than perfectly competitive – which they almost always are – and fail to equilibrate instantaneously – which they always do – the results are that much worse.

Markets Undermine the Ties That Bind Us

While political economists criticize market inefficiencies and inequities, many others have complained, in one way or another, that markets are socially destructive. In effect markets say to us: You cannot consciously coordinate your economic activities efficiently, so don’t even try. You cannot come to efficient and equitable agreements among yourselves, so don’t even try. Just thank your lucky stars that even such a hopelessly socially challenged species such as yourselves can still benefit from a division of labor thanks to the miracle of the market system. Markets are a decision to punt in the game of human economic relations, a no-confidence vote on the social capacities of the human species. Samuel Bowles explained market’s antisocial bias eloquently in an essay titled “What Markets Can and Cannot Do” published in Challenge Magazine in July 1991:

Even if market allocations did yield Pareto-optimal results, and even if the resulting income distribution was thought to be fair (two very big “ifs”), the market would still fail if it supported an undemocratic structure of power or if it rewarded greed, opportunism, political passivity, and indifference toward others. The central idea here is that our evaluation of markets – and with it the concept of market failure – must be expanded to include the effects of markets on both the structure of power and the process of human development. As anthropologists have long stressed, how we regulate our exchanges and coordinate our disparate economic activities influences what kind of people we become. Markets may be considered to be social settings that foster specific types of personal development and penalize others. . . . The beauty of the market, some would say, is precisely this: It works well even if people are indifferent toward one another. And it does not require complex communication or even trust among its participants. But that is also the problem. The economy – its markets, work places and other sites – is a gigantic school. Its rewards encourage the development of particular skills and attitudes while other potentials lay fallow or atrophy. We learn to function in these environments, and in so doing become someone we might not have become in a different setting. . . . By economizing on valuable traits – feelings of solidarity with others, the ability to empathize, the capacity for complex communication and collective decision making, for example – markets are said to cope with the scarcity of these worthy traits. But in the long run markets contribute to their erosion and even disappearance. What looks like a hardheaded adaptation to the infirmity of human nature may in fact be part of the problem.

Markets and hierarchical decision making economize on the use of valuable but scarce human traits like “feelings of solidarity with others, the ability to empathize, the capacity for complex communication and collective decision making.” But more importantly, markets and hierarchical relations contribute to the erosion and disappearance of these worthy traits by rewarding those who ignore democratic and social considerations and penalizing those who try to take them into account. It is no accident that despite a monumental increase in education levels, the work force is less capable of exercising its self-management potential than it was a hundred years ago, or that people feel more alone, alienated, suspicious of one another, and rootless than ever before. Robert Bellah, Jean Bethke Elshtain, and Robert Putnam among others have documented the general decay of civic life and weakening of trust and participation across all income and educational levels in the United States. There is no longer any doubt that “the social fabric is becoming visibly thinner, we don’t trust one another as much, and we don’t know one another as much” in Putnam’s words.7 While it is easier to blame the spread of television than a major economic institution, the atomizing effect of markets as they spread into more and more areas of our lives bears a major responsibility for this trend.

Market prices are systematically biased against social activities in favor of individual activities. Markets make it easier to pursue wellbeing through individual rather than social activity by reducing the transaction costs associated with the former compared to the latter. Private consumption faces no obstacles in market economies where joint, or social consumption runs smack into the free rider problem. Markets harness our creative capacities and energy by arranging for other people to threaten our livelihoods. Markets bribe us with the lure of luxury beyond what others can have and beyond what we know we deserve. Markets reward those who are the most efficient at taking advantage of his or her fellow man or woman, and penalize those who insist, illogically, on pursuing the golden rule – do unto others as you would have them do unto you. A mathematics instructor at a small college in Liaoyang China who had doubled his income running a small fleet of taxis summarized his experience with marketization as follows: “It’s really survival of the fittest here. If you have a cutthroat heart, you can make it. If you are a good person, I don’t think you can.”8

Of course, we are told we can personally benefit in a market system by being of service to others. But we know we can often benefit more easily by tricking others. Mutual concern, empathy, and solidarity are the appendixes of human capacities and emotions in market economies – and like the appendix, they continue to atrophy as people respond sensibly to the rule of the market place – do others in before they do you in.

This is the standard treatment of the effect of minimum wages in all mainstream textbooks, which thereby conclude that raising the minimum wage must necessarily reduce employment to some extent. However, this treatment and conclusion is quite misleading, as will be discussed in Chapter 11. Note that this conclusion is based on microeconomic considerations alone. Macroeconomic theory, on the other hand, suggests it is quite possible that raising the minimum wage can cause a significant increase in the aggregate demand for goods and services, which can, in turn, cause an increase in the demand for labor to produce more goods. This “macro” effect of a higher minimum wage would be represented as a shift in the labor demand curve to the right, which would increase employment, counteracting the employment reducing “micro” effect of moving to a point higher up on the labor demand curve. So while all agree that the size of the employment shrinking micro effect depends on how elastic the labor demand curve is, when the employment enhancing “macro” effect is also taken into account it is impossible to predict based on theory alone whether or not raising the minimum wage will reduce or increase employment. |

|

Robert Heilbroner, The Worldly Philosophers (Simon and Schuster, 1992). |

|

Most detergents call for a full cup per load of wash. Church & Dwight canceled a 1/4 cup laundry detergent product when consumer demand for this “green” product proved insufficient. Christine Canning, “The Laundry Detergent Market,” in Household and Personal Products Industry, April 1996. |

|

For a rigorous demonstration that endogenous preferences imply snowballing inefficiency when there are market externalities see theorems 7.1 and 7.2 in Hahnel and Albert, Quiet Revolution in Welfare Economics (Princeton University Press, 1990). |

|

The technical name for this is “false trading” whenever deals are struck at a price other than the equilibrium price. Moreover, whenever we have false trading, and inefficiency in one market, we will have false trading and inefficiencies in related markets as well. In general when markets are out of equilibrium there will be disequilibrating “quantity” adjustments as well as equilibrating “price” adjustments. The degree of inefficiency in a market economy due to “false trading” depends on the relative speeds of price and quantity adjustments, and only if price adjustments are infinitely fast so that no quantity adjustment, i.e. false trade, ever takes place, would we avoid these inefficiencies. |

|

Mainstream texts persist in treating such behavior as if it was not the obvious violation of the “laws” of supply and demand that it clearly is. Instead of admitting that demand is not always negatively related to market price, and supply is not always positively related to market price, mainstream texts resort to the subterfuge of saying that the change in expectations about the likely direction of future price changes shifts demand curves and supply curves that still do obey the laws of supply and demand, yielding actual results that contradict what those laws lead us to expect. This is sophistry at its worst. |

|

Putnam made this remark when interviewed at the 1995 annual meeting of the American Association of Political Scientists in Chicago. The Washington Post, September 3, 1995: A5. |

|

Reported in “With Carrots and Sticks, China Quiets Protesters,” The Washington Post, March 22, 2002: A24. |