The first task in creating a biographical sketch of the Combined Chiefs of Staff is to determine just who was included in the principal membership of that organization. There is some debate on this issue. On the British side, everyone agrees that Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke, Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Charles Portal, and respective Admirals of the Fleet Sir Dudley Pound and his successor Sir Andrew B. Cunningham were full members of the Combined Chiefs of Staff. For the Americans, Generals George C. Marshall and Henry H. Arnold and Admirals William D. Leahy and Ernest J. King were, of course, full members. The problem lies in how to define the exact status of five high-ranking British officers: Lieutenant General Sir Hastings Ismay, chief of staff to the minister of defence (Churchill); Vice Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, chief of Combined Operations—and his successor in that post Major General Robert E. Laycock; Field Marshal Sir John Dill, head of the British Joint Staff Mission in Washington; and Field Marshal Sir Henry Maitland Wilson, Dill’s successor. Also problematic is the exact status of American admiral Harold R. Stark, King’s immediate predecessor as Chief of Naval Operations.

Andrew Roberts claims that both Ismay and Mountbatten were full members of the British Chiefs of Staff Committee and therefore also of the Combined Chiefs of Staff, while Mark Stoler argues that Ismay was a full member and Mountbatten “a de facto member.”1 Both of these scenarios are perfectly plausible, and either may well be correct. Personally, the view I favor as regards full membership in the Combined Chiefs of Staff is: Dill, yes; Mountbatten, Laycock, Ismay, Wilson, and Stark, no. My plan of campaign is to first provide thumbnail sketches providing basic biographical information for each of the principal members of the Combined Chiefs of Staff and then to briefly explain why I left out those I have omitted.

Table 1-1 provides a brief outline, in national rather than combined format, of the rank and age (in early 1942) as well as the date of appointment to the head of their respective service for each of the Combined Chiefs of Staff principals.

Table 1-1. Rank, Age, and Appointment Date of CCS Principals

| Age (in January 1942) Appointed | ||

| British Chiefs of Staff | ||

| General Sir Alan Brooke | 58 | November 1941 |

| Air Chief Marshal Sir Charles Portal | 48 | October 1940 |

| Admiral of the Fleet Sir Dudley Pound | 64 | June 1939 |

| Adm. of the Fleet Sir A. B. Cunningham | 58 | October 1943 |

| British Joint Staff Mission in Washington | ||

| Field Marshal Sir John Dill | 61 | January 20, 1942* |

| U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff | ||

| General George C. Marshall | 61 | September 1939 |

| Lieutenant General Henry H. Arnold | 55 | September 1938 |

| Admiral Ernest J. King | 63 | December 1941 |

| Admiral William D. Leahy | 66 | July 1942** |

* In the case of Dill, this is the date on which he was appointed head of the British Joint Staff Mission.

** Leahy was a retired CNO. This date is his appointment to the Joint and Combined Chiefs of Staff.

Personalities

In this section, in contrast to table 1-1, I have listed the members of the Combined Chiefs of Staff in alphabetical order rather than by nationality, in keeping with the combined nature of the organization and of this account.

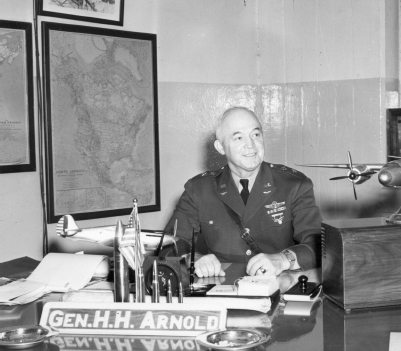

General of the Army Henry H. Arnold, Commanding General of the U.S. Army Air Forces

Hap Arnold prior to Pearl Harbor as a major general. U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

American. Born: June 25, 1886, Gladwyne, Pennsylvania. Died: January 15, 1950, near Sonoma, California. While it is true that General Arnold was a lieutenant general at the inception of the Combined Chiefs of Staff and that he was technically General Marshall’s subordinate, any doubts as to “Hap” Arnold’s status as a full member of the Combined Chiefs of Staff were removed in December 1944, when Arnold and the other three American members of the Combined Chiefs of Staff were promoted to five-star rank.2 Well before then, in March 1943, General Marshall, in recommending Arnold for promotion to four-star rank, had reminded President Roosevelt of Arnold’s status, writing that General Arnold “sits as a member of the United States Chiefs of Staff.”3

Henry H. (Hap) Arnold graduated from West Point in 1907, after which he served a tour of duty as an infantry officer in the Philippines. One of America’s first military aviators, Arnold learned to fly in 1911 in Dayton, Ohio. His instructor, Al Welsh, was employed by the Wright brothers themselves. Arnold’s tour of duty as a fledgling pilot in Dayton regularly included Sunday dinners at the Wright brothers’ home.4 He married Eleanor “Bee” Pool in September 1913; they would have three sons and one daughter.5 As his nickname “Hap” indicates, Arnold was friendly, gregarious, and easygoing—what today would be called a “people person.” But the strain of World War II would take a terrible toll on General Arnold. His constant travels during the war and his workaholic nature put a great strain on his marriage; the marital trouble was exacerbated by the fact that Mrs. Arnold was simultaneously driving herself much too hard, doing volunteer Army Air Forces relief work.6 At just under six feet in height and with a muscular frame, Hap Arnold looked fit. In actuality, he was anything but, suffering a number of serious heart attacks during and after the war, including the one that killed him in 1950.7 The strain of preparing for big wartime conferences greatly exacerbated Arnold’s heart troubles. Indeed, General Arnold missed both the Trident Conference in Washington in May 1943 and the Yalta Conference of February 1945, because on each occasion he was in hospital recovering from a heart attack. Arnold suffered at least four heart attacks during the war years alone—all before he had reached the age of sixty. Arnold was intensely loyal to General Marshall; he was a humble man who was not at all certain that he deserved a fifth star when he was promoted to that exceedingly rare rank in December 1944.8

Arnold gave his active and enthusiastic support to the first American program to train female pilots to fly military aircraft—the WASPs, Women’s Airforce Service Pilots. However, Arnold’s then-progressive view of gender roles did have its limits. While female pilots logged thousands of flying hours during the war ferrying combat aircraft, by Arnold’s personal order WASP activity was confined to the continental United States. America’s female pilots were prohibited from serving overseas during World War II, even in noncombat roles.9

Arnold’s membership in the Joint Chiefs of Staff from the outset had been Marshall’s idea.10 Marshall and Arnold trusted each other implicitly and were good friends. Marshall was farsighted enough to recognize the importance of airpower and sensible enough to realize that Hap Arnold, as commanding general of the U.S. Army Air Forces, knew how to mobilize that power.11 Arnold’s efficiency in managing the air war was greatly appreciated by the Chief of Staff. In his 1942 Christmas greeting, Marshall wrote to Arnold that “the tremendous problems of expansion, together with the complications of the ferry service and air operations in various corners of the world, have been met with efficient direction. You have taken these colossal problems in your stride but still have managed to retain some remnants of a golden disposition.”12

Hap Arnold has sometimes been unfairly branded as a lightweight in terms of his abilities as a strategist. (See below for Admiral King’s dismissive attitude regarding Arnold’s intellect.) Airpower truly came of age as a decisive weapon during World War II. General Arnold realized its potential very early in his career—much earlier than King did. When Hap Arnold qualified as a pilot, in 1911, the U.S. Navy did not even have an aircraft carrier. Admiral King, on the other hand, and for all his obvious brilliance, learned to fly only in 1927, almost as an afterthought, when he was forty-eight years old. Indeed, Arnold’s biographer has suggested that King’s sensitivity over his own tardiness in realizing the importance of airpower was one reason why King tended to belittle Arnold.13

Arnold understood aircraft design, and he was heavily involved in production issues. Arnold knew the directors of aircraft manufacturers like Boeing and Douglas, and he visited their factories frequently. Aviation tycoon Donald Douglas admired Arnold for always looking ahead and seeing the big picture. In his untiring efforts to get the giant Boeing B-29 bomber into service during World War II, Arnold learned a lot about engines—which on the B-29 were particularly troublesome. Admiral King’s assertion that, unlike Portal, Arnold knew nothing about engineering was almost certainly unfair and wrong.14

Recognizing talent is a form of genius in itself. In that regard, General Arnold’s deep respect for Marshall shows that Arnold was not at all lacking in intellectual ability.15 In his efforts to be of service to General Marshall, Arnold seems to have felt guilty about his own heart trouble. Indeed, Arnold felt that by suffering a heart attack just before Trident he had failed Marshall badly. Arnold wrote from his bed at Walter Reed Army Hospital to General Marshall, on May 10, 1943, “This is one Hell of a time for this to happen. My engine started turning over at 160 when it should have been doing 74 to 76. For this I am sorry. Back to normal now.”16

Some who met the genial, always smiling Arnold underestimated his willpower. Most people didn’t know that the man who as his biographer writes is “universally acknowledged as the father of the modern American Air Force” had to overcome an overwhelming fear of flying. That fear had taken hold after he was almost killed early in his career when a plane he was piloting at Fort Riley, Kansas, suddenly and inexplicably became uncontrollable, causing Arnold to make a terrifying and risky forced landing.17 The experience left him deeply shaken—so shaken that it would be four years after his near-death experience of November 4, 1912, before Arnold would again take the controls of an airplane. So deep was Arnold’s sudden-onset fear of flying that he actually rejoined the infantry, doing a second tour of duty in the Philippines—where, incidentally, he met a young officer named George C. Marshall for the first time.18 With the approach of American entry into World War I and the concomitant need to train aviators, Arnold was coaxed back into the air service in 1916 by William “Billy” Mitchell, then a major, who would become an important influence on Arnold. Sent to an army airfield at San Diego that year, Arnold went as a supply officer, not a pilot, because he was still not over the trauma of his near-fatal 1912 flight and was not ready to take to the air again even as a passenger. Being stationed at an airfield, however, soon had the effect desired by his superiors, and Arnold became determined to overcome his fear of flying. By the end of 1916 he was not only flying again but was back in the cockpit, taking up planes on his own.19

A lieutenant general when the Combined Chiefs of Staff was inaugurated in January 1942, Arnold was promoted at General Marshall’s instigation to four-star rank on March 19, 1943.20 Hap Arnold respected General Marshall so much that he said, “If George Marshall ever took a position contrary to mine, I would know I was wrong.”21

General Arnold and Admiral King were on friendly terms overall but sparred over certain issues. As he did with Marshall, King did not feel that Arnold knew much about the navy and resented the fact that Arnold automatically backed Marshall on all major issues. The Chief of Naval Operations felt that the requests put forth by the Army Air Forces in terms of budget, personnel, and equipment were not based upon what was really needed but represented instead arbitrary and unnecessary maximums.22 The subject of land-based aircraft for submarine hunting was a contentious issue for Arnold and King. In early 1942 King endeavored to put Army Air Forces aircraft that were operating in coastal areas of the United States under the control of the navy for the purposes of maritime patrol.23 This was an especially urgent question in the first half of 1942, because German submarines were then scoring their greatest successes against American merchant shipping along the eastern coast of the United States. A few weeks later, King was able to report with satisfaction in a letter to one of his sea frontier commanders, “You now know that we have had success in attaining ‘unity of command’ in the sea frontiers which can be expected to improve matters in that you can now tell the army air units what to do instead of asking them to do it.”24

Despite their differences, the views of King and Arnold had, by the spring of 1944, converged upon the issue of the Mariana Islands in the western Pacific. King wanted to seize Guam, Saipan, and Tinian as the lynchpin of his Central Pacific drive. General Arnold came to support this idea, because the Marianas could provide bases for the hundreds of B-29 Superfortress bombers that he was planning to use for the strategic bombing campaign against Japan. The Army Air Forces high command had come to appreciate the difficulties involved with basing the B-29s in China or India. The Marianas were within relatively easy B-29 striking distance of Tokyo and were much easier to supply than was any base on the Asian mainland.25 In September 1947 the U.S. Air Force was officially separated from the army. On June 3, 1949, Arnold’s official title was formally changed from “General of the Army” to “General of the Air Force.”26 Hap Arnold remains the only American air force officer ever to attain five-star rank.

Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke, Chief of the Imperial General Staff

British. Born: July 23, 1883, Bagnères-de-Bigorre. Died: June 17, 1963, Hartley Wintney, Hampshire. Born in France, Brooke’s permanent family home and heritage was Northern Ireland. General Brooke became Field Marshal Brooke effective January 1, 1944. In this account I have tried to use the title for him appropriate to when he is being cited or mentioned.

General Sir Alan Brooke was appointed Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS) in November 1941, when Admiral Pound was chairman of the British Chiefs of Staff Committee. In March 1942, Brooke became chairman of the British Chiefs of Staff Committee, although Pound remained on the COS Committee as First Sea Lord and chief of the Naval Staff, posts that Pound had held since the summer of 1939.27 Field Marshal Dill, who had been Brooke’s predecessor as army chief, was technically the senior British member of the Combined Chiefs of Staff. Dill may well have exercised more influence overall in the British-American alliance than did Brooke.28 However, in day-to-day dealings in London with Winston Churchill, Brooke was clearly the most influential member of the British Chiefs of Staff Committee. Brooke, like Pound and Portal, harbored no resentment over Dill’s unique position in Washington. As Sally Lister Parker points out, “the British Chiefs trusted Dill implicitly as their representative.”29

Brooke’s personality—his brusque and rather dour mannerisms—earned him the instant and lasting enmity of the Americans, particularly General Marshall. What was most responsible for that reaction was aptly articulated by the CIGS himself: in correspondence with J. R. M. Butler and Sir Michael Howard during the preparation of the Grand Strategy series, Brooke wrote that in his opinion, “Any idea of a cross Channel operation was completely out of the picture during 1942 and 43 except in the event of the German forces beginning to crack up, which is very unlikely.”30

Brooke had served heroically in battle in both world wars, never displaying the slightest concern for his own personal safety.31 How then, does one explain the attribute for which Brooke is most known during World War II, his deep reluctance to undertake Operation Overlord, the cross-channel invasion? Why would a fighter shy away from a fight? Brooke, of course, had terrible memories of the slaughter on the western front during World War I. Also, historians have noted that there was a feeling in the British army in World War II, particularly early, when defeats were common, that Britain’s soldiers in this war were simply not as good as those who had served in the British Expeditionary Force during World War I.32 For instance, Alex Danchev has noted that in World War II “there were deep reservations in the British high command about the capacity of their own soldiers pitted against the Germans, and in particular about the quality of British military leadership.”33 General Brooke fully shared this pessimism and lack of confidence. For example, in March 1942 Brooke confided to his diary that he felt that British forces in general were not currently fighting with enough determination:34 “Half our Corps & Divisional Commanders are totally unfit for their appointments, and yet if I were to sack them I could find no better! They lack character, imagination, drive & power of leadership.”35 Here Brooke is talking about lieutenant generals and major generals. Thus, if his comment was accurate, the British army really was in trouble. Brooke’s biographer has written that early in World War II, Brooke was convinced that the British army as a whole, both officer corps and enlisted ranks, was not up to Great War standards.36

Brooke was an expert ornithologist and avid trout fisherman. Yet despite his love of watching and studying birds, Brooke was not above killing a few on occasion. For instance, Brooke and Churchill spent a day hunting partridge just after the Casablanca Conference.37 A parallel between Brooke and Marshall is that both men lost a beloved first wife but remarried happily shortly thereafter. Brooke’s first wife, Janey, was killed in 1925 in a car accident in which Brooke was driving—a circumstance that undoubtedly left him with lasting feelings of guilt as well as grief. He married Benita Lees in 1929, which happened to be less than a year before Marshall’s second marriage. Brooke was more fortunate than Marshall in one respect—that both of his wives were capable of bearing children. Brooke had two children by each of his wives.38

One of the major stressors on Brooke during World War II was, of course, the person of Winston Churchill. A September 1944 entry in Brooke’s diary amply demonstrates how difficult it was for the orderly and extremely self-disciplined Brooke to work for a loose cannon like Churchill. Of his boss Brooke wrote, “Three quarters of the population of the world imagine that Winston Churchill is one of the strategists of history, a second Marlborough, and the other quarter have no conception of what a public menace he is, and has been throughout this war. . . . Without him England was lost for a certainty. . . . [W]ith him England has been on the verge of disaster time and again. . . . Never have I admired and despised a man simultaneously to the same extent.”39 The dual challenges of keeping the prime minister “on the rails” and of the increasingly bitter debate in regard to the cross-channel versus Mediterranean controversy between Brooke and Marshall ensured that Brooke had a very difficult and unpleasant job during World War II.40

Developing strategic ideas and plans and setting them down on paper were never Brooke’s strong points. He was more apt to refine and champion those submitted to the Combined Chiefs by the planning staffs that he thought had merit.41 One of Brooke’s greatest contributions to the smooth functioning of the Combined Chiefs of Staff was his ability to handle effectively some of the difficult personalities, both civilian and military, with whom he was forced to consort. Brooke’s role in this regard has been spelled out accurately by Sir James “P. J.” Grigg, the British secretary of state for war: “Above all [Brooke] was the man who managed to restrain Mr. Churchill from embarking on fruitless and costly operations. This was no easy task.”42 Similarly, after the war Mountbatten claimed that one of Brooke’s great contributions as CIGS was that Brooke had seemed to be the only person in the Allied high command whom the vainglorious General Bernard Montgomery respected. Despite his reputation for tactlessness in formal conference, Brooke was apparently quite skillful in resolving the disputes that grew out of Montgomery’s insulting manner toward Churchill, thereby preventing Montgomery from being fired. One such episode occurred in early January 1945, during the Battle of the Bulge, when Montgomery attempted (unsuccessfully) to prevent Churchill from visiting Allied troops at the front.43

One of Brooke’s wartime aides has pointed out that one reason for Brooke’s success as CIGS is that he understood how to delegate, which is of course an essential skill for effective management. He did not get caught up in the details of day-to-day military operations (something which could not be said of the prime minister). Therefore, Brooke was able to concentrate on the larger issues being discussed by the Combined Chiefs of Staff.44

Brooke made a poor first impression upon his COS colleague Sir Charles Portal when the two first met in 1940, owing to Brooke’s abruptness and lack of interpersonal skills. Portal noticed that whether dealing with politicians such as Churchill or with other members of the Combined Chiefs of Staff, Brooke expressed his views forcefully, loudly, and frequently without any sense of tact. Nonetheless, in spite of initial doubts about whether Brooke would be effective as Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Portal quickly came to admire Brooke, and the two became good friends.45

The same could never be said for Brooke’s relations with his American CCS counterparts. Portal felt that “right to the end of the war . . . Brooke ‘jarred’ on the U.S. Chiefs of Staff. They did not understand him and disliked his abrupt manner and aloofness.”46 The chief of the Air Staff also felt that the Americans were getting under Brooke’s skin.47 Portal could see that without the good offices of Sir John Dill, “who smoothed things out and interpreted Brooke to the Americans,” the work of the Combined Chiefs of Staff would have been much more difficult and much less productive.48

Just how much Brooke “jarred” on the Americans was made clear by General Joseph Stilwell, who recorded in his diary a contretemps between General Brooke and Admiral King at the Cairo (Sextant) Conference in November 1943. Stillwell recorded, “Brooke got nasty and King got good and sore. King almost climbed over the table at Brooke. God he was mad. I wish he had socked him.”49

Brooke’s first visit to Washington, in June 1942, allowed him to get to know General Marshall (whom he had met for the first time the previous April) a little better. While in Washington Brooke had his first meeting with Admiral King. From that interview Brooke formed a clear impression that General Marshall was primarily concerned with an early second front in Europe but that Admiral King was focused on shifting the war against Japan into high gear. Brooke did not feel that the Americans had at this time reached a very high level of interservice cooperation.50 (As we will see, he was right about that.) In the light of these observations, Brooke noted in his diary, “There is no doubt that Dill is doing wonderful work and that we owe him a deep debt of gratitude.”51

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Andrew B. Cunningham, First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff

British. Born: January 7, 1883, Dublin. Died: June 12, 1963, London. Great Britain has had many great admirals in its history, but only one, Sir Andrew B. Cunningham, is considered to have been in the same league with Lord Nelson. While commanding the British Mediterranean Fleet early in World War II, Admiral Cunningham was to the Italian navy what Sir Francis Drake had been to the New World settlements of Philip II’s Spain—that is, its worst nightmare. Cunningham was without peer as a seagoing commander. He disliked the periodic spells ashore in which he was required to do staff work; however, his performance as a staff officer was better than is sometimes realized.52

Cunningham was a fighter—literally. As a young naval cadet, he had never been shy about engaging in fistfights. As a cadet, Cunningham was on hand during the Diamond Jubilee naval review held in honor of Queen Victoria in the Spithead channel between Portsmouth and the Isle of Wight on June 27, 1897.53 While there Cunningham undoubtedly witnessed, or at least heard about, what is perhaps the greatest public relations coup of all time, namely, the demonstration staged by one Charles Parsons, a brilliant engineer who charged through the anchored fleet in his specially designed steam launch Turbinia, a vessel built to prove the superiority of the new steam-turbine engine Parsons had developed. Parsons was hugely successful. British and foreign naval dignitaries were astounded to see Turbinia’s slender hull sprinting across the roadstead at well over thirty knots, an unheard-of speed for any seagoing vessel of the 1890s.54 The advent of the steam turbine and its undoubted superiority over piston engines marked one of many changes the world’s leading navies were undergoing at the close of the nineteenth century. The Royal Navy that Cunningham would lead as an Admiral of the Fleet in World War II would be heavily reliant on steam-turbine technology.

As Cunningham’s biographer has noted, all was not well with the Royal Navy at the end of the nineteenth century. Lord Nelson a century before had encouraged junior officers to think for themselves. However, by the time of Cunningham’s formative years as a young midshipman, “the essence of Nelson’s success had been forgotten.”55 By 1900 and well into World War I at least, officers in the Royal Navy, even officers at the rank of rear admiral, waited to be told what to do by senior admirals in charge. For instance, late at night on May 31, 1916, during the closing stages of the battle of Jutland, the crew of the British battleship HMS Malaya actually saw elements of the German battle fleet passing astern of the British fleet. The Malaya’s captain, Algernon Boyle, did not open fire, because, not expecting the Germans to try such a move, the British fleet commander, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, had given no orders for the battleships bringing up the rear of his formation to be on the lookout for and if possible engage German battleships in a night action. In 1916, captains of British warships were reluctant to open fire unless an admiral ordered them to do so. But Jellicoe had no idea that the enemy fleet was passing astern of his formation; he thought the bulk of the German forces were out in front of him somewhere, and he intended to renew the battle the next day. Nobody bothered to inform Jellicoe that the German fleet was not where it was supposed to be. The Malaya’s captain informed the commander of the division to which his ship belonged, Rear Admiral Sir Hugh Evan-Thomas, but the latter not only refrained from ordering an attack but also failed to relay the report to Jellicoe.56 Everyone assumed that the senior admiral was fully aware of everything that was going on and that there was no need for any subordinate to make a decision.57 Nelson would have been appalled. The aggressive leadership that Admiral Cunningham would display during World War II in his assignments afloat and ashore would do much to show the world that the Royal Navy had by then fully regained its aggressive spirit.

Early in his naval career, Cunningham became expert in the handling of destroyers (and their steam-turbine engines) and commanded one, HMS Scorpion, in the Mediterranean during World War I. Later, he served as captain of the battleship HMS Rodney. He was an avid golfer, gardener, and fisherman. Cunningham married Nona Byatt in December 1929; they were both in their forties at the time and would have no children.58

During World War II, under Cunningham’s command, the British Mediterranean Fleet carried out the daring November 1940 raid on the Italian fleet anchorage at Taranto in which British torpedo planes flying from the aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious sank three Italian battleships (although two of these were subsequently raised from the harbor bottom, pumped out, repaired, and eventually put back into service). In March 1941, at the battle of Cape Matapan, Cunningham struck again, and hard. A Royal Navy pilot flying from the aircraft carrier HMS Formidable dropped a torpedo that damaged the Vittorio Veneto, one of Italy’s newest battleships. Then Cunningham led his three battleships and a squadron of cruisers in a night action in which three Italian heavy cruisers were sunk. Later that spring, Admiral Cunningham won the undying admiration of the British army by ignoring intense German air attacks in order to evacuate over 20,000 British and New Zealand troops from Crete.59

Admiral Cunningham served a brief tour of duty as the leader of the British Admiralty Delegation element of the British Joint Staff Mission in Washington in 1942. In that posting, Cunningham proved to be quite equal to the task of arguing with the volatile Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral King. In arguments that usually revolved around trying to get King to relent enough in his obsession with the war against Japan to devote more American resources to the Battle of the Atlantic, King recognized the fighter in Cunningham and grew to respect him for it.60

General Marshall too thought highly of Cunningham. Indeed, Marshall’s biographer has written that “Marshall spoke for himself as well as for his colleagues, when he wrote, ‘he enjoys our complete confidence.’”61 Admiral Cunningham had without complaint accepted his posting as Dwight D. Eisenhower’s subordinate in the billet of commander of Allied naval forces in the Mediterranean during Operation Torch and subsequently during Husky (the invasion of Sicily), as well as in the beginning of the Allied campaign in Italy. This showed character and forbearance, because it could be argued that Cunningham’s brilliant combat performance in the Mediterranean in 1940–41, coupled with his highly successful tour of duty with the British Joint Staff Mission in Washington, made him far more qualified than Eisenhower to be the supreme commander of Torch and Husky. In fact, however, Eisenhower and Cunningham became good friends and worked extremely well together.

For the purposes of this study, Cunningham’s most important characteristic was the fact that he was a vigorous proponent of operations in the Central Pacific. He shared Admiral King’s view that the Central Pacific drive was the key to defeating Japan. Cunningham had no sympathy for retaking Hong Kong or Singapore, which Britain would get back automatically when Japan surrendered anyway. This position put Cunningham deeply at odds with Churchill, who was very eager to restore British prestige in the Far East through such means as marching British troops back into Hong Kong and Singapore before Japan surrendered. For Cunningham, unlike Churchill, it did not matter how the Japanese were defeated, as long as they were defeated.62

Field Marshal Sir John Dill, Head of the British Joint Staff Mission in Washington

British. Born: December 25, 1881, Lurgan (near Galway, Ireland). Died: November 4, 1944, Washington, D.C. Great friend of General Marshall and Brooke’s immediate predecessor as Chief of the Imperial General Staff, it was probably a blessing in disguise that Field Marshal Sir John Dill’s tenure as CIGS early in the war was unsuccessful. Otherwise, he would not have been cashiered from the position and could not have taken up the post of head of the British Joint Staff Mission in Washington. Churchill neither liked nor respected Dill. Churchill probably did not “like” Brooke either, but the prime minister respected Brooke far more than he did Dill. Appointed by Churchill as CIGS in May 1940, Dill served in that post until December 1941. Part of the reason that Dill’s tenure as uniformed head of the British army was a torment that probably shortened his life is that Dill took over command of the army at a time when Britain’s military situation appeared hopeless.63

Dill’s efforts to keep the prime minister grounded in reality incurred Churchill’s wrath, but as Alex Danchev has noted, Dill’s tenure as Chief of the Imperial General Staff was actually more successful than is sometimes realized: “It was above all Dill who responded to the imperative of the moment and established the wearying but constructive adversarial relationship between Churchill and the Chiefs of Staff on which Brooke, blessed with new allies and augmented resources, so successfully built in 1942 for the duration of the war.”64

General Brooke certainly did inherit the task of short-circuiting the prime minister’s wilder ideas. The unending conflict that characterized Dill’s relations with Churchill in London inevitably made his tenure relatively short. In November 1941, it was announced that Field Marshal Dill would retire as CIGS the following month, to be given the sinecure post of governor of Bombay. World events changed all that—Dill never made it to India. The turnover of his duties as army chief to the new CIGS, General Sir Alan Brooke, coincided with American entry into the war. Dill therefore accompanied Winston Churchill to the Arcadia Conference in Washington in December 1941 as a lame-duck CIGS. Dill had by then struck up a friendship and correspondence with General Marshall, whom he had met at the Atlantic Charter Conference at Argentia, Newfoundland, in August 1941.65

After the Arcadia discussions in Washington wrapped up in January 1942, Churchill left Dill in Washington, an idea that had originated with General Brooke, to head up the British Joint Staff Mission there. This was undoubtedly one of the best decisions Churchill made during the war. In Washington, Dill’s close friendship with General Marshall contributed greatly to reducing, although certainly not eliminating, turmoil in the Western alliance.66 In addition to being the head of the British Joint Staff Mission, Dill was instructed by Churchill, in a memorandum written on February 6, 1942, to consider himself Churchill’s personal representative in day-to-day dealings in Washington with the Americans. Interestingly, in regard to the “personal representative” part, Churchill had apparently needed to be prodded by President Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) before he agreed to grant this much power to Dill, undoubtedly due to lingering bad feelings.67 The misunderstandings that already existed between Churchill and Dill, and those that were just beginning between Generals Brooke and Marshall, would persist. However, as Danchev writes, “The change wrought by Dill’s removal to Washington was that the tensions became creative.”68

The importance to the Anglo-American alliance of the close friendship between Field Marshal Dill and General Marshall has been thoroughly chronicled by others.69 There is ample evidence in the archives to support the contention that with the possible exception of Arnold, Dill was Marshall’s closest colleague among the Combined Chiefs of Staff.70 In an address he gave at an award ceremony honoring Dill at Yale University, General Marshall paid warm tribute to his good friend, characterizing him as “single-minded in the sincerity of [his] efforts to promote the unity of our two great nations.”71 Dill in fact got on very well with all the U.S. chiefs. He called Arnold by his nickname “Hap.” Even Admiral King, whose relations with his British allies were sometimes rocky, was on excellent terms with Dill. King visited Dill frequently when the field marshal was lying ill at Walter Reed and served as an honorary pallbearer at his funeral in November 1944.72 Dill explained his recipe for successful Anglo-American relations: “To have different views even on major questions of policy need not embitter relations. The great thing on both sides is to be completely frank and when we or Americans have political as opposed to purely military factors influencing action to explain that they are.”73

As mentioned earlier, Dill was the senior British representative on the Combined Chiefs of Staff. A bit of qualification is called for here. General Brooke, as chairman of the British Chiefs of Staff Committee from March 1942, was certainly Churchill’s closest military adviser, while Dill was three thousand miles away in Washington, D.C. Perhaps it could be said that just as Admiral Leahy was nominally the senior member of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, where he was completely overshadowed as a strategist by Marshall and King; so Dill was nominally the senior British member of the Combined Chiefs of Staff, even though General Brooke clearly had greater influence with Churchill. Where Field Marshal Dill did have plenty of influence was in Washington with the Americans. Indeed, Brooke’s proportionately greater influence with Churchill and Dill’s proportionally greater influence with the Americans made not only Dill and Marshall a good team but also Dill and Brooke.74

Field Marshal Dill was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Medal by the United States. His efforts in Washington were also praised in a joint resolution issued by Congress on December 20, 1944. The latter was an honor never before bestowed upon a person who was not an American citizen.75 Also unusual, but entirely fitting, was that Dill was buried in Arlington National Cemetery, just across the Potomac from Washington, D.C., the city where he had achieved his greatest successes as a soldier and a diplomat.

Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King, Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet and Chief of Naval Operations

Ernest J. King late in the war as a fleet admiral. U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

American. Born: November 23, 1878, Lorain, Ohio. Died: June 25, 1956, Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Ernest Joseph King commanded in World War II the largest and most powerful navy the world is ever likely to see. That and Admiral King’s global strategy-making responsibilities as a member of the Combined Chiefs of Staff make him the most powerful naval officer in American history.76 After graduating from the Naval Academy in 1901, King became known, as he would be throughout his career, to be extremely ambitious and extremely bright. He was also arrogant, competitive, and stubborn. King made many enemies, but few doubted his brilliance. Married in October 1905 to Martha “Mattie” Egerton, King had six daughters and one son. While he was harsh with naval personnel who served under him, King appears to have been a somewhat indulgent father. His marriage proved to be a mismatch, however, and by the time he became a member of the Combined Chiefs of Staff, King and Mattie were living very separate lives. A renowned philanderer, King enjoyed parties, and when he went to one he was always on the lookout for attractive women he might seduce.77

For all of his adult life Admiral King was a heavy drinker. Misbehavior while drunk had resulted in reprimands by his superiors on several occasions as a young officer.78 Aware of the trouble that alcohol was causing him, King shifted from hard liquor to beer, wine, and sherry as his drinks of choice during World War II. That may not have solved his problem, however, which seemed to be volume consumed rather than type. For instance, during the war King could easily knock back six glasses of beer in one evening. Therefore, the label of “functional alcoholic” is probably appropriate for King both before and during the war. He also smoked. Probably the only thing King had in common with FDR other than a love of the navy was that both men used old-fashioned cigarette holders. King’s other hobbies included reading and crossword puzzles.79 He was thought to be humorless, but not by those who knew him well. For instance, King was highly amused to hear that even before Pearl Harbor many thought him “so tough that he had to shave with a blowtorch.”80

In his rise to the top of the navy, King’s intelligence and ambition led him to be always on the lookout for new challenges. He was versatile, having served in destroyers, a cruiser, and battleships. During World War I, King served in Europe on the staff of Vice Admiral Henry T. Mayo. After the war, he served in submarines and commanded the submarine base at New London, Connecticut. This position led to some of the most challenging work of King’s pre–World War II career, when he was called upon to oversee the salvage of the wrecks of two submarines, the S-51 and the S-4, which had sunk as the result of training accidents in New England waters.

After qualifying as a naval aviator in 1927, King was given command of the aircraft carrier USS Lexington in 1930. The Lexington always enjoyed the reputation of being a happy ship. The men who served on board the Lexington loved their ship deeply. King was no exception. When the Lexington was sunk by air attack in the battle of the Coral Sea in May 1942, King took the loss of his old command personally. Indeed, King seemed to blame Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, the American commander on the scene, more than the Japanese naval aviators who had launched the bombs and torpedoes. Many of the men serving on the Lexington at the time she was sunk had served under King. Indeed, so popular was the Lexington that many members of her crew during the Coral Sea battle were “plank owners,” who had been with the ship since it joined the fleet back in 1927. The loss of the Lexington and King’s dissatisfaction with the way Fletcher later handled other carriers during the Guadalcanal campaign brought out King’s mean streak. King, now the fleet commander and in a position to send admirals wherever he wanted them, was largely responsible for Admiral Fletcher’s being “beached” in late 1942 to fly a desk in Seattle as commander of the Northwestern Sea Frontier for a year. Fletcher was eventually given command of the North Pacific Area, but by that time, the autumn of 1943, the area was a quiet backwater, and the job was still at a desk—this time on the windswept, bleak island of Adak in the Aleutians chain off Alaska rather than in Seattle. True, Admirals Nimitz and King also had desk jobs, but theirs were highly influential and interesting postings.81

King certainly required efficiency from his staff. He himself always got to the point quickly in discussions and in memoranda and expected the same from others. Still, he was, as stated previously, not without a sense of humor.82 One of his former aides wrote that “to those who worked directly for him [King] was thoughtful and kindly—but you had to produce.”83 Nevertheless, it is safe to say that many of the personnel working in the Navy Department building on Constitution Avenue in Washington greatly preferred dealing with Admiral King’s chief of staff, Rear Admiral Richard S. Edwards, instead of King if at all possible. Edwards’ efficiency and kindness were greatly appreciated by King’s staff, and by Admiral King as well. Edwards had been hand-picked for the job of chief of staff by King himself, but his billet was not an easy one.84 King’s biographer amply sums up the volatility of working conditions under Ernest J. King: “Despite King’s dependence upon Edwards, King could still be a bastard. After weeks of work Edwards once submitted a plan to King for approval. King returned it with a red-penciled notation, ‘Take this to the head with you.’”85 The contradiction between King’s volatile personality and the consummate gentlemanliness of General Marshall could not have been more apparent. Indeed, Admiral King was a study in contrasts. He too could be a perfect gentleman when he wanted to be, but the enfant terrible mode suited him just as well.86

Admiral King was highly confident of his own abilities. He considered himself to be the brightest member of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff. King’s ranking system placed the other members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in the following descending order of ability after himself: Marshall, Leahy, Arnold.87

For Admiral Raymond Spruance, who commanded most of the campaigns involved with the Central Pacific drive, Admiral King would always be associated with the idea of seizing the initiative early and never relinquishing it.88 Spruance wrote King, “It seemed to me that this was always uppermost in your mind whenever you were considering operations in the Pacific.”89

Although they worked together very effectively during the war, King and Marshall did have a few differences of opinion. For example, King felt that Marshall had been slow to realize the value of seizing the Mariana Islands, while the navy had been discussing the possibility of such an operation as far back as the 1920s. King also felt that the reasoning behind Admiral Leahy’s appointment as senior member of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff was that the president had not felt that General Marshall knew enough about sea power.90 King appreciated Marshall’s courteous nature, however, and the latter’s sincere efforts to learn more about the navy. In July 1943, General Marshall was King’s guest during a brief shakedown cruise aboard the brand-new Essex-class aircraft carrier Lexington. King was later pleased to report that “Marshall inspected all parts of the ship from engine room to gun turrets and bridge.”91

Like Marshall, King found General Brooke a difficult person to deal with. King respected Brooke, however, and perhaps for the very stubbornness that Marshall found so exasperating. In addition to finding a good friend in Admiral Pound, King also thought highly of Air Chief Marshal Portal (as did the Americans in general). He rated Portal ahead of Cunningham and Brooke as regarded the abilities of the British Chiefs of Staff Committee;92 King in fact offered praise for the British Chief of the Air Staff at the expense of King’s American colleague Hap Arnold: “Portal, the air man on the British Chiefs, had real brains, and understood strategy and engineering. He was very much broader in his views than Arnold. Portal would talk about anything that was important or interesting. . . . Arnold was not in the same class as Portal as to brains or abilities.”93

Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy, Chief of Staff to the Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States

William D. Leahy. U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

American. Born: May 6, 1875, Hampton, Iowa. Died: July 20, 1959, Bethesda, Maryland. A retired Chief of Naval Operations who had served as American ambassador to Vichy France, William D. Leahy assumed a role as a member of the Combined Chiefs of Staff that was half political, half military. Leahy graduated from the Naval Academy in 1897 and gained experience in destroyers, ordnance, and battleships.94 Leahy married Louise Tennent Harrington in February 1904. The couple had one son. Louise died in 1942, shortly before Admiral Leahy departed Vichy to return to the United States; Leahy brought his wife’s remains home to the United States for burial. The death of Louise was one of several reasons why the post of U.S. ambassador to Vichy France was a very difficult assignment for Leahy. The other main reason was the collaborationist nature of that regime and the question as to whether America should have had any relations at all with it.95

Both the president and General Marshall had wanted Leahy to join the new U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff organization when he returned from France in mid-1942. The president had been quite happy with Leahy’s tenure as Chief of Naval Operations in the late 1930s and trusted his judgment implicitly. General Marshall hoped that Admiral Leahy would be a neutral referee who could mediate disputes between Marshall and King. He feared that once Admiral Stark left Washington for London in March 1942, Admiral King might feel outnumbered on the Joint Chiefs of Staff by the two army generals, Arnold and himself. By suggesting Admiral Leahy to the president as a chairman, Marshall thought he had hit on the perfect solution—King was sure to have no objection to a fourth member being added to the U.S. Joint Chiefs if that member was another admiral.96

Unfortunately for General Marshall, the president threw a wrench into the gears of the plan. Instead of being an impartial chairman of the Joint Chiefs, the president seemed to want Admiral Leahy to serve as his personal liaison to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, much as General Ismay served as Winston Churchill’s liaison to the British Chiefs of Staff Committee. The result was that Admiral Leahy was unable to devote all his attention to military matters.97 With an office in the White House, Leahy, who had no political ambitions whatsoever, found himself dealing with many purely political matters that he found highly awkward and distasteful.98

One of these occurred in the run-up to the 1944 presidential election. As we have seen, Admiral King had two titles during the war—Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet, and Chief of Naval Operations (CNO). Of the two titles, King seemed to prefer the former.99 In King’s papers are numerous letters written on letterhead bearing at the top the legend, “United States Fleet: Headquarters of the Commander in Chief.” This is a reference to Admiral King, not the president. Shortly before the 1944 election, Admiral Leahy informed Admiral King that the president would be happy if King would refrain from using the title “Commander in Chief.” Apparently, FDR was nervous that voters might forget just who had ultimate control over the navy. The prickly King replied that he would accede to Leahy’s request only if it were transmitted to him personally by the president. Given FDR’s loathing of confrontation, that, of course, never happened, and King used both titles for the remainder of the war.100 Admiral King did, however, think it was wasteful to have two titles, especially since each office came with its own staff. He was in favor of consolidating the COMINCH and CNO posts, and this was done by executive order in December 1945, when Admiral Nimitz succeeded King as the navy’s most senior admiral. It is interesting to note, however, that the title retained for the newly consolidated position and bestowed upon Admiral Nimitz in 1945, and on every subsequent uniformed head of the U.S. Navy, has been that of “Chief of Naval Operations.” No other admiral since King has been allowed to call himself “Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet.”101

In regard to Admiral Leahy’s distaste for the political aspects of his job, Admiral King’s biographer Thomas Buell has written that “Leahy was so bewildered by watching Roosevelt during the 1944 presidential elections that the president joked that, when it came to politics, the Admiral belonged in the Middle Ages. Leahy thought that the Dark Ages would have been a more appropriate description.”102 Unlike King, Admiral Leahy was not an aviator and as CNO in the late 1930s had seemed to feel that the navy’s future lay with battleships rather than aircraft carriers. The carrier would become the “queen of the fleet” during World War II, but during his tenure as CNO Admiral Leahy had a hand in providing the navy with the six modern battleships of the North Carolina and South Dakota classes. These ships all gave good service during World War II, and Leahy had seen to it that they were outfitted with 16-inch guns. Doing that was not as easy as it may seem. The North Carolina and the Washington, construction of which began in 1937, were the first new American battleships to be laid down after the end of the fifteen-year “building holiday” on battleships imposed by the Washington and London Naval Treaties. However, these were still in theory “treaty” battleships, restricted to 35,000 tons displacement each and to guns of no larger than 14-inch caliber. However, the London Naval Treaty of 1936 included an escalator clause stipulating that if any signatory to the naval treaties breached the terms by adding larger guns, the other parties could “up-gun” their own battleships from fourteen to sixteen inch. As rumors began circulating in the late 1930s that Japan was building new battleships with very large main batteries, Admiral Leahy insisted that the new American battleships carry 16-inch guns.103

Leahy’s wisdom in this regard can be seen in a brief comparison between the battleships he sponsored and the British battleships of the King George V class, built at about the same time as the North Carolinas and the four South Dakotas (i.e., Massachusetts, Alabama, Indiana, and South Dakota). The British attempted to adhere strictly to treaty limits. Thus, HMS King George V and her four sister battleships each carried ten 14-inch guns. Two of this class—King George V and Prince of Wales—were to participate in the hunt for and destruction of the German battleship Bismarck in May 1941. The King George V class were certainly good ships, but the new American battleships were better.104

During meetings of the Joint and Combined Chiefs of Staff, Leahy often proved an effective mediator of differences of opinion that arose between Marshall and King.105 Indeed, Leahy’s presence in Washington seems to have had a calming influence in general. For instance, the admiral helped to settle a late-1942 dispute over the control of American merchant shipping between Lewis Douglas of the American War Shipping Administration (WSA) and Lieutenant General Brehon Somervell, head of the U.S. Army’s Services of Supply (better known as the Army Service Forces).106

General of the Army George C. Marshall, U.S. Army Chief of Staff

General Marshall wearing five stars. U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

American. Born: December 31, 1880, Uniontown, Pennsylvania. Died: October 16, 1959, Washington, D.C. General George C. Marshall was a man who never laughed at the president’s jokes and who bristled when the president, or almost anyone else, called him by his first name. Marshall was determined that FDR’s considerable charm never sway him from bringing up unpleasant issues that he felt needed presidential attention. These issues included weekly, face-to-face recitations to the president of the latest American casualty figures. This was medicine FDR certainly did not enjoy taking but that Marshall felt was needed to ensure that the president did not become hardened to the human toll of war. Marshall had excelled as a staff officer throughout his career. Words like “cold,” and “distant” are often used to describe General Marshall’s demeanor during the war.107 General Ismay has written of him that “it was impossible to imagine his doing anything petty or mean, or shrinking from any duty, however distasteful. He carried himself with great dignity.”108

Marshall attained the rank of temporary colonel during World War I, but it was not until 1920, eighteen years after he joined the army, that his permanent rank was raised to captain. Marshall was promoted to brigadier general on October 1, 1936. After having waited thirty-four years to attain his first general’s star, Marshall made the jump from one-star to four-star rank in one day when on September 1, 1939, he officially became army Chief of Staff (he had been acting Chief of Staff since July 1). President Roosevelt appointed General Marshall over the heads of thirty-four other generals senior to him. Marshall’s biographer has added the qualification that most of the generals senior to Marshall were too close to retirement age to be serious contenders for the job and that Marshall was actually fifth on a short list of five candidates.109 However, with the crisis of impending war it is doubtful if President Roosevelt would have let age be a barrier to appointing the man he wanted, as long as the candidate was physically and mentally fit. Indeed, Admiral King was less than a year from the supposedly mandatory retirement age of sixty-four at the time of his appointment as Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet. Although the always-ambitious King was distraught over the possibility that he might be retired in the midst of the most interesting and challenging posting of his career, he felt it his duty to remind the president in October 1942 that his sixty-fourth birthday was fast approaching. FDR laughed off any suggestion of retiring Admiral King and kept him on for the duration.110

Ismay was right about Marshall’s inability to be petty. As Chief of Staff, Marshall was immune from the feeling expressed by some business executives and others in positions of responsibility toward their subordinates—“I went through it, so they have to go through it”—in regard to his own long-delayed promotions. It became a fundamental goal for the new Chief of Staff to do away forever with the arcane system of promoting officers on the basis of seniority. Marshall was determined that in an army he was leading, officers would be promoted upon merit alone.111

Despite his reputation for reticence, Marshall’s humanity was vibrant and palpable. He had no biological children of his own, but always found time for children who wrote him letters during the war. Indeed, in March 1944 General Marshall wrote a detailed reply to a class of middle-school students in Virginia who had written the Chief of Staff seeking firsthand information on the war from the man in charge. The students were particularly eager to know how General Marshall maintained what the children had heard was a photographic memory.112 General Marshall corrected this misinterpretation: “Mrs. Marshall tells me that my memory is seriously defective in some respects, frequently to her inconvenience.”113 In April 1943, General Marshall learned that a seven-year-old boy named Mark Reed had waited for him, hoping for an autograph, at an airfield near Asheville, North Carolina, during a visit by the general that had been advertised in the local newspaper. Mark was unable to get close enough for an autograph, and the boy’s mother wrote to General Marshall to express her son’s disappointment.114 The general swung into action, dispatching the following letter on April 29:

My dear Mark: I was very sorry to learn that you were disappointed in your kind effort to greet me at the airport south of Asheville last Sunday afternoon, also that you did not get the autograph you desired. I am sending you a sketch with my best wishes and I hope you will accept this in lieu of the meeting which failed to materialize.115

After graduating from the Virginia Military Institute (VMI) in 1901, Marshall married the beautiful Elizabeth (Lily) Carter Coles on February 11, 1902, shortly before he shipped out as a second lieutenant of infantry for a tour of duty in the Philippines. The marriage was a happy one, but Lily suffered from a chronic heart ailment that apparently made the strains of pregnancy and childbirth out of the question for her. The couple remained childless, which was a disappointment since she loved children as much as he did. Marshall served in France during World War I as a staff officer in the U.S. 1st Division under Major General William L. Sibert. During the war, Marshall’s diligence and willingness to speak his mind made a good impression on General John J. Pershing, who would become a lifelong friend and mentor. Lily’s heart problems grew worse in the 1920s, and she died in September 1927.116

Marshall married again in October 1930, a marriage that, like his first, was quite happy. His second wife, Katherine Tupper Brown, was a widow with three children. Marshall greatly enjoyed his role as stepfather to Clifton, Molly, and Allen Brown. Marshall and Allen, the youngest child, were particularly close. When Allen joined the army after Pearl Harbor, both he and Marshall made strenuous efforts to see to it that nobody learned of the connection between them. They were in complete agreement that Allen’s success in the army should be measured on the basis of merit alone. Consequently, Allen Brown, stepson of the Chief of Staff, entered the army at the exalted rank of private.117

Marshall and Allen were not entirely successful in keeping their relationship—for all intents and purposes that of father and son—secret. Sometimes a well-meaning commander would try to do Allen a favor, thinking General Marshall would approve. When this happened, the officer in question would quickly be disabused of the notion that greasing the skids in any way for the Chief of Staff’s stepson was a good idea. For instance, Major General Alvan C. Gillem Jr. wrote to General Marshall in June 1943 asking if the general would be the speaker at the upcoming graduation ceremony at Fort Knox, Kentucky, for officer candidates (in this instance including one Allen Tupper Brown) who had completed a course of instruction in armored warfare and were to be commissioned as second lieutenants.118 General Marshall was appalled at the idea. In his reply Marshall not only declined the invitation but, no doubt knowing that Allen would be in complete agreement with him, essentially ordered Gillem “to see that [Allen’s] graduation bears no comment on his connection with me.”119 Mrs. Marshall’s daughter Molly had two children of her own, to whom General Marshall was delighted to be honorary grandfather.120

General Marshall’s biographer admits that there was something of the “New England Yankee” in General Marshall. This was a reference to his often stiff formality and to Marshall’s personal habits, such as that he was always careful to keep his finances in order. Perhaps the only vice Marshall ever had was that he smoked cigarettes until in his fifties, when he quit. His hobbies included horseback riding, gardening, canoeing, and fishing.121

As he did for children, General Marshall would sometimes drop formality completely with adults as well. During the war an official car with a Women’s Army Corps chauffeur might pull up to a bus stop in the Washington, D.C., area, and a distinguished-looking officer in the back seat would roll down a window and offer a lift to the commuters waiting there on their way to work. Total strangers would suddenly find themselves getting rides to their jobs from the Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army.122 Such gestures were undoubtedly especially appreciated by the beneficiaries in view of the facts that gasoline was under wartime rationing and that even if they owned cars civilians could not legally purchase items like new tires, the rubber of which was also a closely rationed commodity.

Although General Marshall’s strictly merit-based system for promotions and his personality made it useless for acquaintances to petition the Chief of Staff for promotions, Marshall did occasionally do favors.123 One that shows his humanity quite nicely occurred in June 1944, when Marshall wrote to Lieutenant General Jacob L. Devers, who was then serving in Italy as commander of the U.S. Sixth Army. An Italian-American barber whom Marshall patronized in a shop on the concourse at the Pentagon, Joe Abbate, was terribly worried about his uncle, who was trapped in wartorn Italy. The Chief of Staff offered to intercede, and in a letter that reads partly as a request and partly as an order, Marshall asked Devers to find the uncle, deliver to him a letter (written by the barber’s wife) and some cash from Joe Abbate, and to see if he, Devers, could give the old man a paying job.124 Since Marshall’s entire life had been the absolute antithesis of cronyism, he seems to have felt a bit guilty about using his influence in this matter. He confided to Devers, “I don’t know how much trouble I am imposing on you but if you have any contact with Messina I should appreciate your helping out in this. Incidentally, Joe had no idea of my taking this action. He was merely telling me the story of his uncle when I offered to get a letter through, and money, if he cared to send it.”125

Devers duly located the uncle, delivered the money, and got the man a job in the reconstituted, post-Mussolini Italian government. The younger Abbate was known to Devers as well as Marshall, because in addition to his barber shop at the Pentagon, Joe Abbate had been something akin to the official army barber at Fort Myer, Virginia, where General Marshall lived and where Devers had once resided.126

Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Charles Portal, Chief of the Air Staff

Sir Charles Portal. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

British. Born: May 21, 1893, Hungerford. Died: April 22, 1971, Chichester. Charles Portal became Britain’s most distinguished Air Force officer of all time, ending his days as Viscount Portal of Hungerford and a Marshal of the Royal Air Force. The latter title is the equivalent of an American five-star general. His biographer, Denis Richards, speculates that Portal’s lifelong love of hawking; i.e., training and using a falcon to hunt smaller birds for him, helped Portal decide to become a military pilot during World War I.127 Richards notes that directing the Royal Air Force during World War II and hawking both involved Portal in “nature’s timeless routines of the pursuer and the pursued, the soaring and the broken wing, combat, blood and death.”128

Portal married Joan Margaret in 1919. They had two daughters.129 Portal had joined the COS Committee in October 1940 when he became Chief of the Air Staff.130 Portal was brilliant and very well liked by the Americans. Always courteous, Portal dealt politely but firmly with explosive personalities like Winston Churchill and Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur “Bomber” Harris. Indeed, Churchill and Portal got along quite well together.131

Like Brooke, Portal was an avid trout fisherman. Indeed, after the first Quebec Conference in August 1943, Portal and Brooke went on a fishing trip to a lake in Quebec Province and landed close to two hundred trout between them. They were apparently superb anglers. As to type of trout caught, it can be surmised that most were (very appropriately) eastern brook trout, which are native to those waters and, like the general, are often referred to by the sobriquet “brookie.” Portal recorded that they donated their catch to a hospital in Quebec where the “patients probably got a bit tired of a fish diet.”132 Portal, Brooke, and Admiral Cunningham returned to the same area in September 1944 after the second Quebec Conference; Cunningham had to depart early, but Brooke and Portal this time caught over two hundred trout combined.133 (Most fishermen would consider a hundred trout caught during an entire six-month season of weekend fishing to be an excellent haul.) At the end of this trip, the two men received a telegram from Churchill who had been unable to join the party, but who was keenly interested in its progress. This message shows that not all of Portal’s and Brooke’s interactions with the prime minister were unpleasant: “Following for CIGS and CAS from Prime Minister. Please let me know how many captives were taken by land and air forces respectively in Battle of Snow Lake.”134 The reply Portal drafted showed that the Chief of the Air Staff was every bit the equal of the prime minister in terms of wit and dry humor: “Casualties inflicted by our land and air forces were approximately equal and totaled about 250 dead including the enemy general who surrendered to Land forces on Tuesday afternoon. In a short rearguard action at Cabane de Montmorency our air forces accounted for the largest submarine yet seen in these waters.”135

In addition to being a much-needed friend to Brooke, Portal got along well with Admiral Pound, but he felt that Pound was often unable to look beyond strictly naval matters in order to see the big picture in terms of grand strategy.136 Portal was known for the gentlemanly demeanor with which he treated everyone. However, this did not mean he was a pushover in the councils of the Combined Chiefs of Staff. Because he seems to have avoided overt clashes, Portal’s steadfastness shows up best, perhaps, in the context of dealings with the senior commanders who reported to him. He was not afraid to show his subordinates who was boss if he felt they needed reminding. This was true even if the person who needed reminding was someone as powerful as the Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris, commander in chief of RAF Bomber Command. Harris’ command was to become quite large and he himself very influential, enjoying direct access to the prime minister. In addition to driving energy, Harris was also known for his biting sarcasm. This latter quality showed up forcefully in a September 1942 letter to Portal in which Harris complained bitterly after having been ordered by the chief of the Air Staff to send some of his bombers to the Middle East, thus taking them temporarily out of the bombing campaign against Germany. Portal rebuked Harris in no uncertain terms: “I feel bound to tell you frankly that I do not regard it [the letter] as either a credit to your intelligence or a contribution to the winning of the war. . . . I am sure that great benefit would be gained if you could manage to take a rather broader view of the problems and difficulties confronting the Air Ministry and the other Commands and if this could be reflected in the tone and substance of your letters in future.”137

The Arnold-Portal airman-to-airman relationship was critically important. They liked each other and worked together quite well, frequently in highly productive one-on-one meetings.138 Getting on well himself with the Americans, Portal could not help but sense what he called a “political undercurrent” in British dealings with the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff. To Portal it seemed that the reason the Americans constantly argued against British plans for operations in the Balkans was a belief that the British were attempting to replace the empire they were losing in the Far East with one in the Balkans.139 According to the chief of the Air Staff, “At times the British Chiefs of Staff felt that in addition to the defeat of the Axis, the U.S.A. policy was to cripple the British Empire regardless of the consequences.”140

Portal agreed with Brooke and disagreed with Marshall by supporting Allied landings in Italy to follow the Sicilian campaign. However, Portal differed from Brooke and Churchill in that Portal never intended that Allied troops should slug it out all the way into northern Italy. The air-conscious Portal wanted the airfields around Foggia in southern Italy to be available for use by Allied aircraft. He also favored the seizure of Sardinia.141 History has since shown that if there had to be an Italian campaign, Portal’s idea of confining the operation to seizing the airfields in southern Italy was the way to go.

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Dudley Pound,

First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff

British. Born: August 29, 1877, Isle of Wight. Died: October 21, 1943, London. Admiral Pound may have suffered from narcolepsy, as he appeared to nod off frequently during meetings.142 Whether it was narcolepsy or some sort of epileptic seizure disorder that was causing Pound’s temporary blackouts, the situation enraged General Brooke. A spring 1942 entry in Brooke’s diary shows to good advantage Brooke’s contempt for the Chief of the Naval Staff: “I went near to losing my temper with old Dudley Pound. I feel it almost impossible to stir him up. . . . [H]e is always lagging about 5 laps behind even when he is not sound asleep.”143 The fact was that Pound had at that time only a little over a year left to live; the possibility that he was seriously ill never seems to have occurred to Brooke.

Pound married Betty Whitehead on October 14, 1908. They had two sons and a daughter. Of Betty Pound’s biographer writes, “She was to prove the ideal naval wife, devoted to her husband’s career and their children, always ready to make a new home and move at a moment’s notice.”144 Like Portal and Brooke, Pound was a devoted angler, and he also enjoyed wing shooting. Those who worked for Pound found him somewhat aloof, not unlike General Marshall. However, Pound was capable of spontaneous acts of kindness toward his staff. On one occasion, Pound remembered that one of his junior intelligence officers was interested in naval history and presented him with a book about Admiral Sir George Anson.145

Like Brooke, Pound had combat experience, having served as captain of the battleship HMS Colossus at Jutland in May 1916. Keeping up with Churchill’s hours during World War II and putting up with his outbursts definitely took a toll on Pound. For a man who knew so many people, Winston Churchill seems to have had comparatively few friends. Yet Pound was one of them.146 With his usual eloquence, Alex Danchev explains how Pound and Churchill were in many ways kindred spirits: “Like Portal, but unlike Dill or Brooke or Cunningham, [Pound] was congenial to Churchill. The two men used to meet in the early hours of the morning for an insomniac whisky in the Admiralty Map Room. A more propitious circumstance for nurturing a relationship with Churchill can scarcely be imagined.”147 Insomnia indeed lends credence to the possibility that Pound suffered from narcolepsy.

In contrast to the tension between Brooke and Pound, it is clear that Admirals King and Pound had a very high regard for each other.148 In spite of his reputation for gruff ill humor and occasional downright nastiness, Admiral King regularly wrote letters of condolence to Admiral Pound in regard to the sailors killed when British warships were sunk in action.149 The surviving correspondence between Pound and King has an invariably friendly tone. Pound prefaced his letters to King with “My Dear Admiral,” “My Dear Ernest,” or “My Dear Commander in Chief.” King’s letters to Pound always begin “Dear Dudley.”150

If, as stated earlier, relations were between Portal and Pound were good, the two men did have some polite disagreements. These often had to do with the best use for long-range bombers. Pound was adamant about the necessity to use long-range land-based bombers to provide air cover for convoys operating in mid-Atlantic, one of the most dangerous areas in terms of U-boat attack. Portal, on the other hand, was reluctant to release long-range aircraft from the bombing campaign against German industrial cities. Pound was desperate to protect the Atlantic sea-lanes, by which troops and supplies were being transported from the United States to England. Similarly, Pound struggled to convince Portal and the Air Staff in 1941 to resume attacks by RAF bombers against German U-boat bases, such as those at Lorient and St. Nazaire, on the French coast.151

Admiral Pound’s relations with his eventual successor, Admiral Cunningham, were excellent. It was apparently Pound who urged Cunningham to accept the posting as head of the British Admiralty Delegation in Washington in the summer of 1942.152 While it would probably be inaccurate to say that Pound “handled” Churchill, it does seem that he had more patience when it came to attempting to head off Churchill’s wilder ideas than would Cunningham. Like General Brooke, Pound chose his fights with Churchill carefully. Usually, instead of trying to derail a bad Churchillian idea directly, Pound would have his staff make a formal study of whatever pet project Churchill was peddling to the Admiralty and then commission a comprehensive report showing in an evenhanded fashion the logistical and strategic inroads Churchill’s idea would make on other, ongoing operations.153 In the end, according to one of Pound’s wartime assistants, Churchill would often say, “Who thought up this damn fool project anyway”?154

Pound worked hard at finding common ground with his colleagues on the British Chiefs of Staff Committee. He believed it to be vital that the three British service chiefs cooperate, and he was willing to compromise on occasion to achieve this.155 Much has been made of the fact that unlike Portal and Brooke, Admiral Pound was an operational commander as well as a staff officer.156 However, it should be noted that it was not unheard of for Portal or Brooke too to get involved in operational matters once in a while. For instance, Portal’s insistence that RAF Bomber Command create the Pathfinders unit was a decision that had important operational results. The American members of the Combined Chiefs of Staff also had operational responsibilities. Admiral King, for instance, kept a close watch on operations in the Pacific theater, and King and Nimitz met face to face remarkably frequently (considering that they were based four thousand miles apart) during the war to discuss them.

As a manager, Pound appears to have had some difficulty in delegating responsibility. Throughout his career, Pound took too much work upon himself. This is one possible explanation for the terrible mistake he made in July 1942 in ignoring the views of on-scene commanders and ordering from London that convoy PQ-17, then off the North Cape on its way to Archangel, scatter to avoid what Pound feared to be an imminent attack by the German battleship Tirpitz.157

Also-Rans

Lord Louis Mountbatten is a good person with whom to start a list of people who don’t quite make the cut as principal members of the Combined Chiefs of Staff. While it is true that Sir John Dill was able to attend the Casablanca Conference only as the guest of General Marshall, not as an official member of the British delegation (although he sat on the British side of the table during the conference), there is evidence that the British members of the Combined Chiefs saw Dill as much more their equal than Mountbatten. As mentioned earlier, Mountbatten attended COS Committee meetings only when combined operations were being discussed.158 This is quite different from the position of say, Portal, who attended COS Committee meetings even if air operations were not on the agenda. As a vice admiral, Mountbatten lagged at least one grade in rank behind the full British members of the Combined Chiefs of Staff. Mountbatten was a trained naval officer who had had highly eventful combat experience as a destroyer captain early in the war. Upon being named Chief of Combined Operations, Mountbatten was promoted to vice admiral in his home service, the Royal Navy, and also to honorary ranks of lieutenant general and air vice marshal in the British army and the Royal Air Force, respectively.159