The Allied war effort in the Pacific was carried out by predominantly American forces. By mid-1944, the American Pacific Fleet had developed into a vast and powerful striking force capable of operating for months at a time in the western Pacific without returning to a fixed shore base such as Pearl Harbor. It was a fleet that repeatedly proved itself fully capable of protecting American marines and infantry from air or surface attack during the amphibious landings of the Central Pacific drive. While that campaign was under way, the land-based U.S. Army Air Forces were attacking Japanese shipping, harbors, and shore installations throughout the Central, South, and southwest Pacific areas with great success. This was an American theater of operations. Consequently, the Combined Chiefs of Staff delegated the control of day-to-day events there to the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff. The instructions of the Joint Chiefs were, in turn, carried out by the two theater commanders in the Pacific—Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet and Pacific Ocean Areas, and General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Allied Commander, Southwest Pacific Area.1

This is not to imply that the Combined Chiefs of Staff as a whole were out of the picture as far as the Pacific War was concerned. Large strategic issues, such as whether and when to begin a campaign in the Central Pacific, were debated at Combined Chiefs of Staff meetings. Indeed, at the same time that the Combined Chiefs of Staff was being set up at the Arcadia Conference in Washington, in late December 1941 and early January 1942, its members set the initial tone for the Pacific. It was during the Arcadia discussions that the British received a pledge from the Americans to put the war against Germany first in order of priority, an idea that had already been accepted in principle by the Americans even before Pearl Harbor, in the “ABC-1” report, which had been ratified during British-American military discussions held in Washington between January 29 and March 27, 1941.2 The Combined Chiefs had the right of approval over what in the way of supplies, munitions, and troops would be sent to the Pacific theater. This was similar to the manner in which, in August 1943, the British Chiefs of Staff were given direct control over operations in the newly created Southeast Asia Command, while the Combined Chiefs of Staff as a whole were to allocate supplies and decide on overall strategic objectives there.3

Admiral Nimitz, who took command of the U.S. Pacific Fleet on December 31, 1941, was perhaps the most capable of the theater commanders with whom the Combined Chiefs of Staff interacted during the war. The gentle demeanor and gracious good humor that Nimitz projected belied the strategic genius and gifts of command that lay beneath. Nimitz had all of the interpersonal skills of Eisenhower, coupled with real ability as a strategist.4 Samuel Eliot Morison has paid eloquent tribute to the calming influence Admiral Nimitz immediately began to have upon the personnel of the Pacific Fleet when he arrived at Pearl Harbor a few weeks after the devastating Japanese attack of December 7, 1941:

Chester Nimitz was one of those rare men who grow as their responsibilities increase. . . . Ever calm and gentle in demeanor and courteous in speech, he had tow-colored hair turning white, blue eyes and a pink complexion that gave him somewhat the look of a friendly small boy, so that war correspondents, who expected admirals to pound the table and bellow as in the movies, were apt to wonder “Is this the man?” He was the man. No more fortunate appointment to this vital command could have been made.5

The example of Nimitz shows that not every success that accrued to the Western Allies during the war can be credited to the Combined Chiefs of Staff. Admiral Nimitz was selected for the Pacific Fleet command by President Roosevelt, in consultation with Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox, on December 17, 1941—before the Combined Chiefs of Staff had even been set up. In May 1942, it was Nimitz who retained Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher in command of Task Force 17 (the carrier Yorktown and its escorts) despite doubts harbored by Admiral King regarding Fletcher’s abilities after what King considered to have been Fletcher’s lackluster performance in the battle of the Coral Sea. It was Nimitz who accepted Vice Admiral William F. Halsey’s recommendation that Rear Admiral Raymond Spruance be named as Halsey’s replacement as commander of Task Force 16 (carriers Enterprise and Hornet and their escorts) when Halsey had to be hospitalized for a serious skin ailment just prior to the battle of Midway. The wisdom of Nimitz was shown when Fletcher and Spruance proved to be an excellent team indeed at Midway in June 1942. It was also Nimitz who was quick to understand the significance of the information being provided to him by code breakers who, prior to Midway, had succeeded in cracking part of the Japanese military code and thereby determining that Midway was indeed the Japanese target. Indeed, Nimitz was ahead of Admiral King in correctly interpreting the intelligence data as indicating that the next Japanese attack would occur in the Central Pacific (specifically, at Midway), as opposed to the South Pacific. In a move that would greatly aid the American effort at Midway, it was again Nimitz who determined that the carrier Yorktown, which had been badly damaged in the Coral Sea, could be patched up and made ready for action in seventy-two hours instead of the three months predicted by the repair specialists at the Pearl Harbor navy yard.6

Later in the war, during the Central Pacific drive, Admiral Nimitz made skillful use of Ultra code-breaking intelligence when planning the invasion of the Japanese-held Marshall Islands that began on January 31, 1944. Nimitz correctly interpreted the intelligence indications that the Japanese defenses in the center of the Marshalls chain were unexpectedly weak. Therefore, he surprised Admiral Spruance, by now the commander of the U.S. Fifth Fleet, by ordering him to bypass the eastern Marshalls and invade Kwajelein Atoll, the largest atoll in the world and the heart of the Marshalls chain. The Marshalls campaign was highly successful, and Admiral Nimitz deserves much of the credit for that.7

Therefore, in highlighting the crucial role of the Combined Chiefs of Staff in the success of the Western alliance, it is not my intention to in any way downplay the significance of the contributions to victory of talented field commanders like Admiral Nimitz or the undeniable sagacity shown by FDR in appointing such gifted men.

If American public opinion was galvanized by the Pearl Harbor attack into fully supporting war against Japan, opinion in England was equally outraged by humiliating British defeats at the hands of the Japanese, such as the fall of Singapore. However, in the deliberations of the Combined Chiefs in 1942 it was the Americans, in particular Admiral King, who pressed for immediate expansion of the war effort against Japan. This idea made the British extremely nervous in 1942, as did the fact that by December 1942 there were already 346,000 American troops in the Pacific theater, the equivalent of more than seventeen divisions of infantry and marines, while only 170,000 American soldiers had arrived in England by that time.8 It is interesting to note that “Germany first” notwithstanding, it was at Guadalcanal, in the Solomon Islands of the South Pacific, on August 7, 1942, that American ground forces were first committed to battle in World War II.

The British could do little during 1942 to resist the American desire to carry out offensive, and not merely defensive, operations against Japan. This was due to a profound transformation in the character of the Alliance that took place that year. In short, during 1942 the Americans proved that they would be overwhelmingly the more powerful of the two Western Allies. American military strength grew very rapidly in 1942. By January 1943 the strength of the U.S. Army stood at seventy-three divisions, while the British army comprised fewer than thirty. At this time, Britain was getting a whopping three-fourths of its destroyers, destroyer escorts, and corvette-type submarine-hunting ships from the United States. The Americans were also supplying Britain with vast quantities of light bombers, such as the excellent Douglas A-20. Further evidence of this power shift became apparent in March 1942, when the president and the prime minister divided the globe into three areas of strategic responsibility. All of the Pacific became an American zone; the two nations were to share responsibility for the Atlantic Ocean and Western Europe, while the Mediterranean, the Middle East, and India would be Britain’s responsibility. Under this arrangement, the United States became responsible for the defense of the self-governing British dominions of Australia and New Zealand. This, incidentally, gave the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff leverage against the British when planning operations in the Solomon Islands and in New Guinea. The Americans could simply claim that they had to protect the lines of communication between the United States and Australia. Even from Singapore westward, the British were forced to ask for American equipment and supplies to such an extent that it really became an inter-Allied, rather than a strictly British, zone.9

The British members of the Combined Chiefs of Staff have been characterized as constantly opposed to devoting resources to the war against Japan. According to this school of thought, the British chiefs wanted the Americans simply to conduct a holding action against Japan until after the Allies had vanquished Germany.10 Only then would it be acceptable to conduct full-scale war against Japan.

This certainly was the British attitude at the outset of the British-American alliance. There is evidence that in 1942 the British chiefs fought hard against the American “pull toward the Pacific.” British resistance, however, began to weaken in 1943. There are several reasons for this. The British were certainly up against a great deal of American public, as well as military, opinion that favored all-out war against Japan to avenge Pearl Harbor. However, there is more to it than that. The British chiefs had by the end of 1943 come to believe that full-fledged operations against Japan would not be an undue drain upon resources for the war against Germany and that such operations represented a militarily sound course of action. This sentiment, which the British chiefs began to display in the spring of 1943, received a boost when Admiral Cunningham became a member of the Combined Chiefs of Staff in October. From that time onward, the British chiefs not only looked with more sympathetic interest at ambitious American plans for the Pacific theater but began to desire an active part for Britain in those plans as well.

In short, Cunningham persuaded the British Chiefs of Staff of the viability of the Pacific strategy—a plan to send British forces, particularly naval forces, to the Pacific to operate with the Americans. This brought the British chiefs into conflict with Churchill, who wanted the British to concentrate their naval forces for the war against Japan in the Indian Ocean. The evidence shows that it was the British Chiefs of Staff, and not Churchill, who were instrumental in getting a British battle fleet into the Pacific in December 1944, and it also shows that this was the correct strategy. The fact that the British chiefs could clearly see the value of the Central Pacific drive may have made it easier for the American Joint Chiefs to quietly give precedence to that campaign in early 1944, at the expense of MacArthur’s southwest Pacific advance.11

Christopher Thorne examines closely in his pioneering work, Allies of a Kind: The United States, Britain and the War against Japan, the grave differences that existed between British and American war aims in Asia. Thorne points out very effectively that the Americans were constantly pressing for action to retake Burma from the Japanese as a way to reopen land communications with China, while the British gravitated away from Burma and toward Singapore. This certainly describes the attitudes of such British politicians as Churchill and Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden, as well as that of Vice Admiral Mountbatten and the British military personnel serving under him in the Southeast Asia Command. However, it would seem that at the time that SEAC was created, in August 1943, the outlook of the British members of the Combined Chiefs of Staff as they turned away from Burma was geared more toward the Pacific, as opposed to Singapore and Malaya.

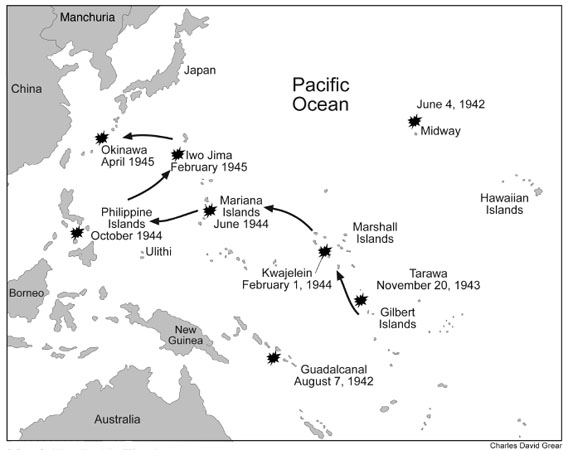

The trend on the part of the Americans of substantially increasing the resources committed to the war in the Pacific continued on a much larger scale during 1943.12 The Americans could claim sole title to Guadalcanal from February 1943, having driven the last Japanese forces from the island. Meanwhile, MacArthur’s forces in the southwest Pacific had taken the eastern half of New Guinea from the Japanese. In addition, on November 20, 1943, the Central Pacific drive got under way when American marines and infantry landed at Tarawa and Makin in the Gilbert Islands. Both had been British possessions before being taken by the Japanese a few days after the Pearl Harbor attack. The Gilberts campaign, known as operation Galvanic, was a furious three-day battle. At Tarawa a thousand American marines and approximately 4,500 Japanese naval infantry and Korean laborers were killed.

At the end of 1943, with Galvanic a costly success and Nimitz’s forces poised to move from the Gilberts to the Marshalls, there were 1,878,152 American service personnel—navy, army, and air combined—involved in the war against Japan. This is slightly more than the 1,810,367 Americans who were deployed against Germany at that time.13

At the Casablanca Conference, in January 1943, the long-simmering differences between the Allies over the war in the Pacific broke into the open. The Combined Chiefs of Staff were thus forced to hammer out a compromise agreement. Clearly, at the time of the Casablanca Conference the British chiefs were still firmly wedded to the idea of maintaining a strictly defensive posture against Japan while focusing almost everything on the defeat of Germany.14 Their dismay at the unwillingness of the Americans to accept any delay in offensive actions against the Japanese was evident when the British Joint Planning Staff reported in December 1942 that in the “U.S. Navy’s opinion ‘There is no such thing as strategic defensive in the Pacific.’”15

The American Joint Chiefs of Staff clearly had two strategies in the Pacific War, one for dealing with the Japanese and one for dealing with opposition from their British colleagues. From mid-1942 onward, the Americans operated under a liberal interpretation of the instructions that had been periodically set out for them in Combined Chiefs of Staff memoranda. These instructions were that the Allies must “maintain and extend unremitting pressure against Japan with the purpose of continually reducing her military power and attaining positions from which her ultimate surrender can be forced.”16 Through mid-1943, the British interpreted this to imply limited offensives, only to prevent consolidation of Japanese positions. The Americans interpreted these instructions as a blank check.

Admiral King reported at Casablanca to his colleagues on the Combined Chiefs that only 15 percent of Allied resources were currently being used against Japan and that this was not enough to prevent the Japanese from consolidating the gains they had made in the wake of the Pearl Harbor attack. As a solution, General Marshall suggested a split in Allied resources of 70 percent for Europe, 30 percent for the Pacific.17

The Combined Chiefs of Staff discussions at the Casablanca Conference were one of many occasions on which General Marshall outlined his strategic views. At Casablanca, Marshall made clear that in his heart he believed Germany to be the principal enemy and that it had to be beaten first. Nevertheless, he backed King at Casablanca by urging immediate offensive action in the Pacific. The reason for this seeming incongruity is that Marshall dreaded a sudden American reverse in the Pacific that would necessitate American abandonment of all commitments in Europe until the Pacific situation could be put right.18 Marshall had already had some scares. For example, in the autumn of 1942 the crisis in the South Pacific, particularly the agonizingly drawn-out American effort to seize Guadalcanal, had been so tense that the Americans had seriously considered, but thankfully ultimately rejected, the idea of withdrawing the sizeable American contingent of troops, aircraft, and ships that had been earmarked for the joint Anglo-American Torch landings in North Africa, scheduled to begin in November. The Guadalcanal operation had been planned hurriedly and carried out on a shoestring; Marshall urged that more U.S. troops and equipment be sent to the Pacific because he felt that the Guadalcanal-style “hand-to-mouth policy” was dangerous for the Allies.19 General Marshall told his colleagues on the Combined Chiefs of Staff at Casablanca “that the United States could not stand for another Bataan”—a reference to the way in which American forces had been run out of the Philippines by the Japanese in the spring of 1942.20 Therefore, while Marshall was most interested in the war in Europe, he knew that planning for operations in Western Europe could not go forward unless it was accompanied by Allied success against Japan.

As stated previously, British military opinion underwent a dramatic transformation during the course of 1943 in regard to the war against Japan. At the beginning of the year, General Brooke vehemently opposed the American pull toward the Pacific.21 This is interesting in light of the way in which the British chiefs later came to support the idea of the American Central Pacific drive and even wanted to participate in it. Never one to compromise easily, Brooke in early 1943 wanted to use all Allied resources against Germany alone;22 he was alarmed at Casablanca to see Marshall backing King and the Pacific so heavily. From the time of Casablanca onward, Generals Brooke and Marshall would often find themselves at odds. They seemed to personify British-American differences of strategic viewpoint.23

During the course of the Casablanca Conference, Field Marshal Dill and Air Chief Marshal Portal were sympathetic to the American viewpoint. Dill and Air Vice Marshal Sir John C. Slessor (an aide to Portal) brokered an agreement on the Pacific that Brooke and the Americans could accept. It involved taking the fortified Japanese South Pacific air and naval base at Rabaul in New Britain, as well as bases in the Marshall and Caroline Islands. This plan was adopted with the proviso that these operations must not slow down the pace of the war against Germany. The spirit of compromise exhibited by Portal, Slessor, and Dill at Casablanca was reassuring to the Americans and may have helped to pave the way for the more in-depth agreements over Pacific strategy at which the Combined Chiefs of Staff would arrive later in the year.24

The Americans saw justification for the adoption of full-scale operations in the Pacific at an early date in plans outlined in July 1942 by the Combined Chiefs of Staff in one of their better-known papers, referred to as “CCS 94.” The Americans interpreted this document to be something of a green light for the Pacific. CCS 94 all but committed the Western Allies to a descent upon the coast of northwest Africa (Torch) that autumn, precluding an invasion across the English Channel until after 1943. Added perhaps as a palliative to the American Joint Chiefs of Staff, who were adamantly opposed to the whole idea of what they regarded as a wasteful diversion to North Africa, was a provision that fifteen groups of American aircraft that had been destined for the buildup in England were to be diverted to the Pacific theater instead. Included were seven groups of bombers, four of transport planes, and two each of fighters and observation planes.25 The arrangement outlined in CCS 94 was confirmed in September 1942. The Americans therefore concluded that if the British were not serious about the cross-channel invasion, it was time to reverse the Arcadia decisions and concentrate on the war against Japan. (Incidentally, the decision for Torch—one of questionable validity in terms of overall strategy—was a rare instance of a major military campaign being framed more by the president and the prime minister rather than by the Combined Chiefs of Staff. Opposition came mostly from the American chiefs, while Brooke, Pound, and Portal gave their cautious support to the Torch plan, although General Brooke was slower in warming to the idea than were Pound and Portal.)26

Part of the reluctance of the British to commit Allied forces to the Pacific theater during 1942 was their conception of the vast naval forces that would be required to defeat Japan and what that would mean to the Battle of the Atlantic. The British Chiefs of Staff felt that an aggressive Allied strategy in the Pacific would so strip the Atlantic of naval forces that the security of the British Isles and the Atlantic shipping lanes would be in grave danger. The American warships most needed by the British in the Atlantic were the small ships that excelled in submarine hunting, such as destroyers and escort carriers.27 In the summer of 1942, Dill wrote to Brooke in reference to the war against Japan that “it is only by building the authority of the Combined Chiefs of Staff that we can do anything to curb the tendency of the U.S. Chiefs of Staff to take unilateral action without consultation.”28

The defeat of the U-boats in the Atlantic by the summer of 1943 and the American successes at Midway and on Guadalcanal seem to have had considerable effect upon the views of the British members of the Combined Chiefs of Staff in regard to the war in the Pacific. This new attitude became apparent at the Trident Conference, in Washington in May 1943. There the British chiefs agreed to an American plan that involved the following objectives:

1. |

Conduct of air operations in and from China |

2. |

Ejection of the Japanese from the Aleutians |

3. |

Seizure of the Marshall and Caroline Islands |

4. |

Seizure of the Solomons, the Bismarck Archipelago, and Japanese-held New Guinea |

5. |

Intensification of operations against enemy lines of communication.29 |

In addition to ongoing success against the U-boats, the British chiefs at Trident were in a generous mood in regard to the ambitious American plans for the Pacific theater because, according to Sir Michael Howard, by the spring of 1943 the availability of Allied resources, such as shipping, aircraft, and munitions, had caught up with Allied strategic planning.30 This point is, however, in need of qualification. Specifically, the British Chiefs of Staff were now aware that simultaneous American offensives in the Central and South Pacific areas would not interfere with limited Allied operations in the Mediterranean, such as the exploitation of Torch. However, Allied resources in spring 1943 would, in the view of the British Chiefs of Staff, still not be sufficient to allow for a 1943 Overlord. The knowledge that the warships of the Royal Navy were more than adequate to deal with any surface action that the German navy might offer prevented the British chiefs from becoming unduly alarmed that new American heavy warships, such as the Essex-class large aircraft carriers, were being sent to the Pacific.31 Also, whereas the primary fear of the British Chiefs of Staff in regard to Overlord was that the Allied armies would not prove large or powerful enough to defeat the German forces stationed in France, the early phases of the Central Pacific drive did not require large numbers of troops. It is true that as the islands Nimitz attacked became larger (e.g., Saipan, Okinawa), he used more and more infantry of the U.S. Army. However, Nimitz also accomplished a great deal with a modest number of marines, of which he never had more than six divisions’ worth. Most of the fighting by American forces on Guadalcanal was carried out by the 1st Marine Division. Similarly, in the Gilberts, Tarawa was seized by the 2nd Marine Division, while the 27th Infantry Division took Makin. Clearly resources, in the form of numbers of troops, went further in the Pacific than they did in Europe.32

The U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff were to get even greater concessions from the British in regard to strategy in the Pacific. At the Quadrant Conference, at Quebec in August 1943, the Americans received British sanction for “the seizure of the Eastern Carolines as far west as Woleai and the establishment of a fleet base at Truk[, and] . . . [t]he capture of the Palaus, including Yap[, as well as] the seizure of Guam and the Japanese Marianas.”33

This British support for operations in the Pacific is in marked contrast to the concerns of the British members of the Combined Chiefs of Staff while the North African campaign was being planned. A few weeks before the Torch landings Dill had written to Brooke about American concerns in the Pacific in a much more conservative vein: “Americans very anxious about Guadalcanal. . . . If things go badly at Guadalcanal, as well they may, I fear a still greater drain on resources for Pacific, though call of Pacific strategically may wane as difficulty of doing the job without our full assistance becomes apparent.”34

The call of the Pacific never waned for the Americans. By the beginning of 1944, the Americans were on the offensive everywhere in the Pacific theater. The preparations for the February 1944 assault on the Marshalls indicate the vast naval and amphibious power upon which the Americans were able to draw by that time. To seize three atolls in the Marshalls—Kwajelein, Majuro, and Eniwetok—Admiral Raymond Spruance’s Fifth Fleet had at its disposal twelve aircraft carriers, eight battleships, six cruisers, thirty-six destroyers, 85,000 troops, and more than a thousand combat aircraft (both carrier- and shore-based). As in the Gilbert Islands, the fast new American aircraft carriers were crucial to the success of these operations. American carrier-based aircraft destroyed every Japanese airplane in the Marshall Islands on the first full day of the assault (February 1, 1944).35

For Admiral King, the path through the Central Pacific seemed obvious. It had figured prominently in discussions and war games at the Naval War College, in Newport, Rhode Island, in the 1920s and 1930s. The results had led to the formulation of a series of what were known as “Orange” plans (Japan having been referred to as “Orange” in the games). By the mid-1920s, it was clear to American naval planners that in the case of war against Japan the first order of business for the United States would be to build up an overwhelming superiority of naval strength in the western Pacific. Also inherent in these interwar American plans was the idea that the island bases that had been mandated to Japan after World War I, such as the Marshalls and the Carolines, would have to become advanced bases for American forces.36 King referred to these twenty-year-old plans when he began stressing the need to advance through the Central Pacific. As early as July 1942 King began telling Nimitz that following the successful conclusion of American operations in the South and southwest Pacific, he should prepare to seize the Japanese fleet base at Truk in the central Carolines, as well as Guam and Saipan in the Japanese-held Marianas. King was determined in the wake of the Casablanca Conference to maintain the initiative in the Pacific, believing it crucial to keep the Japanese off balance.37 At Trident, King fought for and got, with the help of Admiral Pound, a draft statement allowing “a vigorous prosecution of the Pacific war.”38

King liked the idea of a Central Pacific drive, which, he felt, would interfere with Japanese communications, allow the United States to come to grips with the Japanese fleet, and possibly “provide bases from which to bomb the Japanese home islands.”39 His insistence on the Central Pacific drive at a time when American forces were already advancing through the Solomons and in New Guinea shows King’s mastery as a strategist. When the Guadalcanal campaign ended in February 1943, Admirals Nimitz and Halsey were both opposed to the idea of operations in the Central Pacific. They believed it would be better to press on in the Solomon Islands.40 This seems to have been one of the rare occasions when the brilliant Nimitz needed to be nudged in the right direction by Admiral King. According to Grace Person Hayes, in her official history of the war against Japan, “To Admiral King the Pacific commanders seemed to be missing the point. It was quite necessary, he thought, to attack in the Central Pacific as well as in the Southwest Pacific in sufficient strength and at such a time that the two areas could support each other. At least an attempt should be made [as King put it] ‘to whipsaw enemy rather than enable him to concentrate in Solomons or attack on Jaluit–Gilbert–Samoa line or on Midway–Pearl Line.’”41

The firm backing by the Chief of Naval Operations for the Central Pacific drive also demonstrated his appreciation of practical realities. King believed it was essential to get the United States heavily committed to the Central Pacific as a way to put an end to British complaints about the transfer of American naval vessels from the Atlantic.42 This ability of the British members of the Combined Chiefs of Staff to influence the amount of supplies flowing to the Pacific theater sometimes had a hand in determining strategy there. Nimitz risked bad tides at Tarawa because King wanted to get the Central Pacific drive under way before the British could go back on their Quadrant pledge to devote more Allied resources to the war in the Pacific. Consequently, American casualties at Tarawa’s Betio Island were heavier than they might have been, as many marines were forced to wade ashore under fire in chest-deep water because their landing craft were unable to float over the coral reef surrounding the island. In late December the tide would have been higher in the Gilberts.43

The way was made easier for King in dealing with the British over the Pacific issue in that, as Thorne writes, while the Central Pacific drive was getting under way, “little or no progress was being made on the ground during this period either in China or Southeast Asia.”44 From September 1942 to February 1943 British and Indian forces under Field Marshal Sir Archibald Wavell had conducted an offensive against the Japanese in the Arakan, but with disappointing results. Wavell’s forces ended up back where they started. At that point, the Allies seem to have given up on traditional military operations in Southeast Asia for a time, turning instead to Brigadier Orde Wingate’s “Chindit” operations. The first of Wingate’s guerrilla campaigns took place from February to April 1943.45

MacArthur’s advance in the southwest Pacific was steady but slower than what the wide-open spaces of the Central Pacific promised. The situation facing MacArthur was complicated. In addition to the strategic necessity of defeating Japanese forces on New Guinea, MacArthur had been instructed by the Joint Chiefs of Staff in July 1942 to take the key Japanese naval and air bases at Rabaul and Kavieng, in the Bismarck Archipelago. Consequently, MacArthur and his staff devised the Elkton plan of April 1943, a two-pronged advance to surround both Japanese bases. MacArthur’s own forces were to move along the north coast of New Guinea and onto nearby islands, such as Woodlark and Trobriand. Meanwhile, the right arm of the pincer, consisting of Admiral Halsey’s South Pacific forces, were to move north through the Solomon Islands from Guadalcanal. Halsey was under the command of Admiral Nimitz. However, since many of his operations, such as those against the Green Islands in February and March 1944, took place in the Southwest Pacific Area, Halsey cooperated closely with MacArthur. This unusual arrangement worked out well, because Halsey turned out to be one of the few naval officers MacArthur was able to get along with. In the end, it was possible to bypass rather than invade Rabaul and Kavieng. Halsey took Emirau, in the St. Mathias group, in March 1944 in an unopposed landing. By that time, MacArthur’s forces had gone ashore on Manus, in the Admiralty Islands. These two operations provided the Americans with adequate substitutes for Rabaul and Kavieng, thus obviating the need to invade the Japanese strongpoints.46

By the summer of 1944, the overall plan being articulated by the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff for defeating Japan called for air and sea blockade, bombing, and destruction of the Japanese air force and navy, to be followed by invasion.47 Clearly, the scale of the war against Japan had by then increased dramatically, such that the American Joint Chiefs felt it necessary to reassure the British chiefs that the Pacific campaign would not lessen the American commitment to Overlord (cross-channel) and Anvil (southern France) as the paramount operations for 1944.48 There is a certain irony here, for at Trident and Quadrant it had been the JCS (especially Marshall, with his frustration at the British penchant for operations in the Mediterranean) who had pressed the British chiefs to give “overriding priority” to Overlord as the principal Allied campaign for 1944.49 There was, however, a great deal of difference between the American views of operations in the Pacific and in the Mediterranean. As we shall see in chapter 5, Marshall and the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff felt that Allied operations in the Mediterranean were contributing very little (and at great Allied cost) to the defeat of Germany. The American successes in the Central Pacific, on the other hand, were clearly contributing a great deal to the defeat of Japan.

The British Chiefs of Staff were firmly against Culverin, Churchill’s pet plan for an attack against the Japanese in Sumatra. Instead, the British chiefs were by February 1944 strong supporters of operations in the Pacific, particularly the Central Pacific drive. The British chiefs felt that the Central Pacific would provide greater benefits than the southwest Pacific. They saw the latter as difficult terrain and allowing only slower advances, although they conceded that the southwest Pacific drive would require smaller naval forces than would the Central Pacific campaign.50 This British preference for the Central Pacific may have helped Admiral King to bring Marshall, Leahy, and Arnold around to his view of its paramount importance.

Clearly, the absence of British objections to American plans for the Pacific theater after mid-1943 was due not to a surrender by the British to American pressure, as is sometimes claimed, but rather to a dawning realization that those plans were sound and feasible. Another incorrect but prevalent view is that the British, once behind the idea of offensive operations against Japan concurrent with the war in Europe, were only interested in operating British forces in the South and southwest Pacific. While it is true that the British intended to establish a naval base, or bases, in Australia, where space for docking and repair facilities was much more plentiful than in the Central Pacific, where only limited land area was available, it appeared to the British Chiefs of Staff superfluous to continue slugging it out in the southwest Pacific when there was the opportunity to advance by leaps and bounds in the Central Pacific.51 By early 1944, all the members of the Combined Chiefs of Staff seem to have been united as to how the Pacific War should be run, namely, by using both lines of advance in the Pacific, preeminently the Central Pacific route. Growing Allied power had made it clear that, in contrast to the strategy laid out earlier at the Arcadia Conference, full-scale operations against Japan in the Pacific need not await the defeat of Germany.

The creation in spring 1942 of two separate theater commands in the Pacific had certainly been due, at least in part, to interservice rivalry and the need to handle Douglas MacArthur delicately rather than to strategic vision. Neither the Joint Chiefs of Staff nor the president were willing to inform MacArthur (with his monumental ego and his seniority) that his command should be a part of the vast Pacific Ocean Areas command of Admiral Nimitz. Intensely jealous of the proportion of American resources, such as ships and aircraft, being sent to Nimitz, MacArthur fought even the slightest hint that the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff might be trying to place his advance into a supporting role with respect to that of Nimitz.52 This is part of the explanation as to why MacArthur was allowed to conduct offensive, rather than strictly defensive, activities. According to Hayes, in April 1942, when MacArthur’s Southwest Pacific Command was set up, the U.S. Joint Chiefs “did not contemplate large-scale offensives under General MacArthur’s command or, indeed, in the Southwest Pacific Area. Moreover, the demands of other theaters precluded allocating to that area equipment or forces sufficient for an extensive program.”53

While the existence of two theater commands in the Pacific may not have been the most efficient type of command structure, the system provided some unexpected benefits to the Allies. One of these was additional protection for Australia and New Zealand, which, as we have seen, was an American responsibility. Also, with two lines of advance in the Pacific, MacArthur’s and Nimitz’s forces were able to protect each other’s flanks and made it necessary for the Japanese to disperse their own forces.54

The attitude of the Combined Chiefs as a whole in regard to the value of the Central Pacific drive had come around to King’s way of thinking by the late summer of 1943. The decisions made by the Combined Chiefs of Staff at the first Quebec Conference (Quadrant) were heavily weighted toward the Central Pacific, as opposed to MacArthur’s southwest Pacific advance.55 This represented a significant change in the views of the Combined Chiefs of Staff. King—according to his biographer, Thomas B. Buell—in pressing the Central Pacific drive after Trident “was alone in supporting Nimitz over MacArthur.”56 In view of the great rewards that the Central Pacific strategy was to bring, it seems clear that Admiral King was easily the most gifted strategist among the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and probably of the Combined Chiefs of Staff as well.

The Central Pacific drive really picked up steam during the first eight months of 1944. Through the adroit use of the fast carriers, Nimitz’s forces under Admiral Spruance were able to bypass strong points, such as Truk, in the Caroline Islands, and jump straight to the Marianas after the Marshalls campaign. This was an advance of a thousand miles westward in less than four months. MacArthur’s forces in the southwest Pacific could not match the spectacular pace of the Central Pacific drive. In April 1944 MacArthur was still on the northern coast of New Guinea. He had been moving westward along that coast since January 1943.57

By spring 1944, the British Chiefs of Staff were discussing with Churchill three different strategies for the war against Japan. The first was the prime minister’s Bay of Bengal strategy, aimed at restoring British prestige by moving against Japanese-occupied portions of the empire, such as Malaya and Singapore, using northern Sumatra as a jump-off point.58 The second option was the Pacific strategy, which the British Chiefs of Staff preferred. This would involve, as stated by the British chiefs, “The concentration of all available British naval, amphibious, land and air forces to strengthen the main drive in the Pacific.”59 The third option, referred to as the “middle strategy,” envisaged a British and Dominion campaign that would use Australia as a base for an advance on Borneo. The next step in this plan was flexible; it could be a British move north into the Pacific to assist the Americans or, depending upon the situation, operations against Malaya or Singapore. The British chiefs were lukewarm about the middle strategy, proposing it because (as we shall see) they were desperate to get Churchill away from the Bay of Bengal strategy.60

The desire of the British members of the Combined Chiefs of Staff to put a British battle fleet into the Pacific, as opposed to the Indian, Ocean brought them into conflict with both Admiral King and their own prime minister. King wanted the Royal Navy to leave the Pacific to the Americans and fight the Japanese in the Indian Ocean only. It seemed clear to the British that King perceived the potential of a British fleet in the Pacific as a threat to his ability to control day-to-day operations there.61 According to Admiral Cunningham, Churchill’s desire to put the fleet in the Indian Ocean was based on his desire to reoccupy lost parts of the British Empire, as well as the need to help Mountbatten, whose Southeast Asia Command had not initially been given enough troops and equipment to carry out large-scale offensives.62 European imperialism was never a popular subject in the United States during the war.63 Therefore, such an emphasis upon politics and recovering parts of the empire lost to Japan led to the derisive comment in the American military that SEAC really stood for “Save England’s Asian Colonies.”64

It was in the autumn of 1943, shortly after Admiral Cunningham had taken Pound’s place with the Combined Chiefs of Staff, that the idea of putting a British fleet into the Pacific really took hold among the British chiefs. There was a precedent for this. Early March 1943 had found the British aircraft carrier HMS Victorious riding at anchor in Pearl Harbor, having been temporarily loaned to the Americans for operations in conjunction with the U.S. Pacific Fleet.65 The idea for a powerful, all-British battle fleet to operate against Japan in the Central or South Pacific, or both, had originated with Admiral Cunningham. He correctly realized that it was in the Pacific that the war against Japan was being decided, not on the ground in China or Burma, and not in the Indian Ocean. It was in the Pacific, therefore, that the British could make their greatest contribution to victory in the war against Japan. It would also be much easier for Britain to provide logistical support for a fleet in the Pacific, rather than in the Indian Ocean. In addition to contributing materially to Allied victory over Japan, Cunningham knew that the Pacific strategy would give Great Britain leverage in any peace talks and in the postwar world. Brooke and Portal supported Cunningham’s views fully in regard to a British Pacific fleet.66

Churchill’s opposition was vigorous. Cunningham would recall in a postwar interview that Churchill’s objections were so stubborn that “when at the Quebec Conference in September 1944 Mr. Churchill offered Mr. Roosevelt the British fleet for use in the Pacific (under American command) it came as a great surprise to the British Chiefs of Staff.”67 The offer was accepted by the president, a decision about which King was not happy. From the way Churchill had talked leading up to the conference, the British chiefs had no idea that they had finally succeeded in convincing him.68 Cunningham claimed that “it was mainly due to Lord Portal’s eloquence in debate that . . . Mr. Churchill finally agreed to the Pacific Strategy.”69 In fact, although both Churchill and Ismay soft-pedal the issue in their respective memoirs, there was apparently a real threat that the British chiefs, and perhaps Ismay as well, would have resigned if Churchill had persisted in his Bay of Bengal strategy.70

At the height of this crisis—in the summer of 1944, when the British chiefs were thoroughly at odds with the prime minister as to where the British fleet should fight Japan—Cunningham made a revealing entry in his diary explaining why he found Churchill’s Bay of Bengal strategy so outrageous. He wrote that at a meeting with Churchill, Eden, Attlee, and Oliver Lyttelton (minister of production) the British Chiefs of Staff “had hoped to get some decision on Far Eastern strategy but we were treated to the same old monologue of how much better it was to take the tip of Sumatra & then the Malay Peninsula & finally Singapore then it was to join with the Americans & fight Japan close [to] home in the Pacific. The attitude of mind of the politicians about this question is astonishing. . . . They will not lift a finger to get a force into the Pacific. They prefer to hang about the outside and recapture our own rubber trees.”71

In the same entry, Cunningham notes that Churchill’s obsession with recovering lost parts of the empire seemed due to a desire not only to repair British prestige in the Far East but also to forestall the Americans. Cunningham felt that Churchill was overly concerned that the anticolonial Americans might declare immediate independence for Malaya and Singapore if Japan should surrender before Britain could reoccupy its prewar Asian territories.72 Here is a parallel to Churchill’s Balkan strategy in Europe. As with the Balkans, vis-à-vis the Russians, Churchill wanted to be on the ground in Asia with British forces for positioning purposes when the war ended. In this way he could outmaneuver a former ally (the Americans) who, like Russian forces in the Balkans, might have different ideas about the postwar fate of the territories concerned. As Thorne has pointed out, the heightened sense of anticolonial feeling that had become apparent in the United States during the war was a highly divisive issue between Churchill and Roosevelt and between the British and American elements of the Combined Chiefs of Staff.73

What Cunningham, Brooke, and Portal found so exasperating about Churchill’s plans in the Far East is that those plans had no basis in strategic reality. The British Chiefs of Staff also felt that Churchill failed to perceive that the correct strategic option for Britain—the Pacific strategy—would quite likely bring political benefits to England as a by-product. Under this line of thinking, it seemed to the British chiefs, especially Cunningham, that the Americans would be far more likely to accede to postwar British wishes for Asia if Britain had provided concrete assistance in the final campaigns against Japan. The best way to provide such concrete assistance was to get a British fleet into the Central Pacific at the earliest opportunity.74

Not surprisingly, it seems that Admiral Cunningham came to despise the prime minister while serving on the Combined Chiefs of Staff.75 This sentiment shows up repeatedly in Cunningham’s diary, often in relation to the debates over the Pacific strategy. For instance, in regard to a report written by the British Chiefs of Staff for the Americans, just before the second Quebec Conference, in regard to the Pacific strategy, Cunningham’s contempt for Churchill’s abilities as a strategist is readily apparent: “Message to USCOS drafted this morning came back after dinner as amended by the P.M. As usual full of inaccuracies, hot air & political points. Not the sort of business like message we should send to our opposite numbers.”76

The First Sea Lord suspected duplicity even when Churchill was brought around to the viewpoint of the British members of the Combined Chiefs of Staff. There is evidence that Churchill’s offer to the Americans at the Octagon Conference of a British Pacific fleet did not indicate an actual change of heart on the part of the prime minister. The Chief of the Naval Staff recorded in his diary that at Quebec there was “one good political point he [Churchill] wishes to make. He wants to be able to have on record that the US refused the assistance of the British Fleet in the Pacific. He will be bitterly disappointed if they don’t refuse!!!”77 Churchill’s hopes were dashed when President Roosevelt showed that he agreed with the British Chiefs of Staff by accepting the idea of a British fleet for operations in the Pacific. Had FDR refused the offer, Churchill could conceivably have gained leverage to coerce the British chiefs into approving the Culverin operation against Sumatra.78

According to Sir David Fraser in his biography of Brooke, with American acceptance at the second Quebec conference of a British fleet for operations against Japan, “the ‘Pacific Strategy’ quietly died.”79 He is apparently referring to the facts that the British Pacific fleet would operate under American control and that there would be no British land-based air or amphibious (infantry) components involved.80 However, as far as the British Chiefs of Staff were concerned, the fact that a British battle fleet, including two battleships and four aircraft carriers, took up station with the American Pacific Fleet in December 1944 meant that the Pacific strategy was very much alive. The British Chiefs of Staff had hopes that their fleet would operate in the Central Pacific. At Okinawa, it did.81

In pressing so hard for a British fleet in the Pacific, the British Chiefs of Staff were motivated by an urgency that grew out of American accusations that the British were following a “go-slow” policy in the war against Japan. Portal, Cunningham, and Brooke were eager to convince their American colleagues on the Combined Chiefs of Staff that this was not the case at all. As we have seen, American successes in the Pacific had caused the British members of the CCS to feel more optimistic about the potential for full-scale operations there. According to Grace Person Hayes, the situation among the Allied high command at the close of the Quadrant Conference in August 1943 was such that “there was no longer talk of [merely] holding a line in the Pacific until Germany should be defeated.”82

Some of these accusations were reported to Cunningham by his staff. As director of plans at the Admiralty, Captain Charles Lambe, RN (a future Admiral of the Fleet and First Sea Lord), served as presiding member of the British Joint Planning Staff. He was thus very much a part of the Combined Chiefs of Staff Organization, and a close adviser to Admiral Cunningham.83 Like Sir John Dill, Captain Lambe was sympathetic to the American viewpoint in regard to the war against Japan. Lambe kept Cunningham informed about American doubts as to Britain’s resolve in that theater. Such information underlay Cunningham’s motivation to press so vehemently for a British Pacific fleet. In a searching two-page analysis to Cunningham entitled “Anglo-American Relations,” Lambe reported in February 1944 several areas where the Americans were extremely upset with British actions or lack of action. He felt that the Americans had good reason to be upset with British conduct of the war against Japan to date:84

Seen from their angle, [the Americans] have during 1943: |

|

1. |

Watched U.S. built Escort Carriers handed over to us and not used anywhere for months (modifications, etc.). |

2. |

Heard at Trident, Field Marshal Wavell make long defeatist monologue about India and Burma. The impression given was disastrous. |

3. |

Seen the only offensive carrier borne air operations of 1943 undertaken in the whole Atlantic carried out by [USS] Ranger while she was on loan. . . . |

4. |

Heard us pressing for our Fleet Carriers to go to the Pacific but asking in the same breath for the Americans to give us 100% maintenance service in the area.85 |

Lambe further suggested that as a desperate remedy to dispel this negative image in the eyes of the Americans “C in C [Commander in Chief] Eastern Fleet should be ordered to carry out an operation with F.A.A. [Fleet Air Arm] aircraft regardless of its importance during the next six weeks.”86 Lambe clearly saw the need for quick action. He advised Cunningham that to do nothing would be to play into the hands of Churchill, with his bad ideas about how to fight the Japanese (e.g., Culverin). Lambe also urged Cunningham to meet face to face with Admiral King—privately, away from the formality of a Combined Chiefs of Staff meeting—in order to resolve this issue.87

Captain Lambe made a good impression on Admiral Cunningham, who decided that Lambe was the right man to help energize the British war effort against Japan. In mid-1944, Lambe was put in command of the aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious, which, after striking Japanese-held targets in the Dutch East Indies, moved into the Pacific. There the Illustrious and three other British carriers operated alongside American carriers during the Okinawa campaign as part of the newly constituted British Pacific Fleet, which became a subsidiary of the massive U.S. Fifth Fleet.88

Cunningham was getting similar advice from the British Admiralty Delegation of the Joint Staff Mission in Washington. From Washington Admiral Noble informed the First Sea Lord that Admiral King was very unhappy about the results of the Sextant (Cairo/Teheran) Conference of November–December 1943. King apparently blamed the lack of enthusiasm he felt the British chiefs exhibited in regard to Allied operations in the Far East for the cancelation of Operation Buccaneer, a proposed Allied assault to oust the Japanese from the Andaman Islands in the Bay of Bengal. The Americans had seen this operation as a prerequisite for a campaign to drive the Japanese out of Burma and thus reopen overland communication with China.89 The serious conflicts that erupted between the British and the Americans over strategic planning for operations against Japan on the Asian mainland have already been described elsewhere by historians in eloquent detail;90 there is no need to repeat them here. However, it is interesting to note that the cancelation at Cairo of the Andamans campaign served not only to infuriate the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff but also, as Christopher Thorne points out, to “put the weight of the Allied attack against Japan into the two Pacific spearheads.”91 This may have been a factor in the increasing support the British members of the Combined Chiefs of Staff displayed during 1943 in regard to expanded American operations in the Pacific. For them, such a course of action may have provided a welcome alternative to an extensive land campaign in Burma.92

Noble also forwarded to Cunningham the views of British and American staff officers in Washington in regard to American accusations of the British “going slow” against Japan. A member of Noble’s staff at the British Admiralty Delegation of the Joint Staff Mission in Washington, Commander Richard Smeeton, RN, wrote after serving as an observer aboard the new American aircraft carrier Essex during Galvanic, “As a personal note I must confess that the recent Galvanic operations left a slightly bitter taste in my mouth; while our own carriers were apparently inactive, I did not enjoy seeing our Ally employing nineteen aircraft carriers in a hard fought battle for the Gilberts, where incidentally we promptly installed a British administrator!”93

An American friend of Smeeton’s in Washington, Captain Artie Doyle, USN, expressed similar views from the American side. Doyle was a naval aviator who would go on to command the Essex-class carrier USS Hornet during the final year of the war in the Pacific.94 While attending the Sextant Conference as a member of King’s staff, Doyle was alarmed by the extremely pessimistic attitude shown by some members of the British delegation in regard to operations against Japan. Doyle felt the British were far too cautious, even defeatist. Doyle wrote Smeeton that it had been his impression at the Sextant Conference that the admirals of the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm high command had been sadly lacking in any kind of initiative, due to excessive war weariness.95 Perhaps he was struck by the contrast between those officers and the American “aviator admirals,” such as Marc Mitscher, Frederick C. “Ted” Sherman, J. J. Clark, and Arthur Radford, who were always very aggressive and eager to show what their aircraft carriers could do. Doyle informed Smeeton that, due to his frustration over British pessimism during the Cairo/Teheran sessions, he “finally challenged a statement that 150 CV based VF [carrier-based fighter-plane squadrons] weren’t enough to cover an amphibious landing. How the hell could Halsey and MacArthur have got anywhere with that attitude?”96 (In naval parlance, VF refers to a fighter squadron. However, it is possible that Doyle was referring here to 150 fighter aircraft, total.)

The British Chiefs of Staff apparently took such criticisms to heart. It is very interesting that, apparently under Cunningham’s tutelage, the British chiefs ultimately eschewed peripheral strategies and opted for a plan “to strike at the centre and, if necessary, to invade Japan.”97 It is interesting that the British chiefs were here acting the way the U.S. Joint Chiefs did with Overlord. That is, the British chiefs used the Pacific strategy to battle Churchill’s colonial and peripheral Bay of Bengal idea just as Marshall and the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff argued forcefully against British ideas for peripheral, diversionary campaigns in the Mediterranean and the Balkans because such sideshows would have endangered the primacy of Overlord in Allied planning.98 This seems to indicate that by the spring of 1944 Cunningham’s influence with his British Chiefs of Staff Committee colleagues had grown considerably. In view of the dislike of peripheral strategies that he demonstrated during the debate over the Pacific strategy, it is interesting to speculate whether the British Chiefs of Staff would have come out at Casablanca for an early Overlord had Cunningham been with them then.