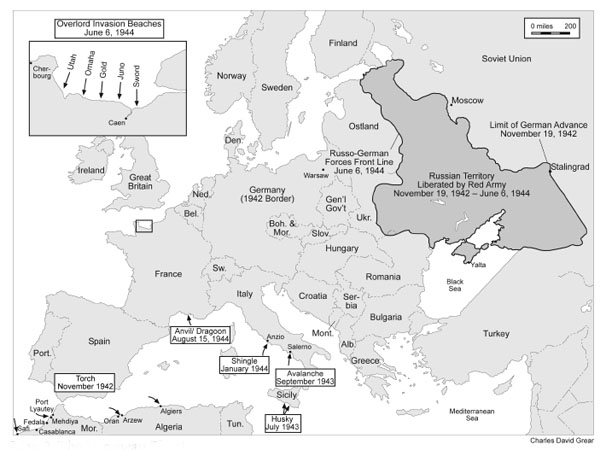

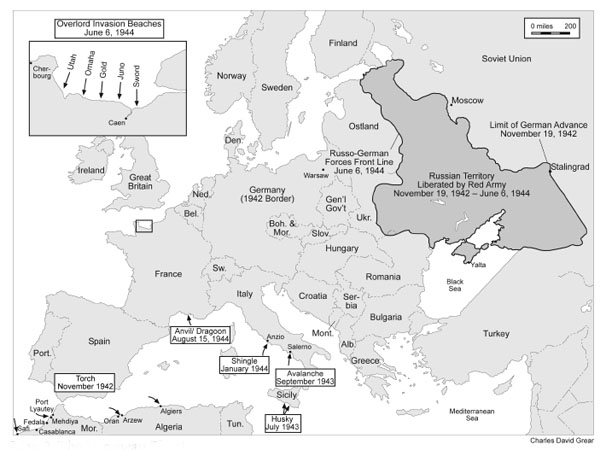

Everything about the planning for the Overlord cross-channel invasion was agonizing, even the process of choosing its commanding officer. The classic cross-channel versus Mediterranean controversy among the Allies can be summed up by saying that General Marshall wanted the Allies to invade across the English channel in late 1942 but that the British, particularly General Brooke, would not hear of this and pressed instead for Allied operations in the Mediterranean. The first large-scale result of this impasse was the Torch campaign in North Africa, which commenced on November 8, 1942. Torch caused the cross-channel invasion to be delayed until June 6, 1944. Historians have long debated whether or not Torch and other Allied Mediterranean operations were necessary and whether a 1942 or 1943 Overlord could have taken place had Torch not been undertaken. It is generally considered that a 1942 cross-channel attack by the Western Allies would have been a disaster and thus that Brooke was undoubtedly correct in believing that the Allies were simply not ready at that time.1 However, 1943 was another matter altogether.

Nobody ever would have heard of Dwight D. Eisenhower had it not been for General George C. Marshall. Indeed, many people are surprised to learn that there was an American general who outranked Eisenhower during the war. Actually, early in the war several generals outranked Eisenhower. In fact, Eisenhower did not even have his first general’s star at the time George C. Marshall attained four-star rank in September 1939. It was Marshall’s system as army Chief of Staff of promoting officers based on merit rather than seniority that allowed Eisenhower to jump from absolutely unknown colonel in the summer of 1941 to five-star general and national hero three and a half years later. Then, in the most dishonorable act of his life, Eisenhower repaid his mentor and former boss by acceding to Senator Joseph McCarthy’s request that he, Eisenhower, remove supportive references to General Marshall (who was the witch-hunting McCarthy’s target du jour at the time) from a speech that Eisenhower was preparing to deliver in Wisconsin during the 1952 presidential election campaign.2

General Eisenhower was by no means the first choice for the command that made him a legend—that of Supreme Commander, Allied Expeditionary Force.3 Generals Marshall and Brooke, Field Marshall Dill, and Lieutenant General Frank Andrews (who had taken over command of American forces in Western Europe while Eisenhower was serving in the Mediterranean) were all considered by the president, the prime minister, and the Combined Chiefs of Staff for the command of the cross-channel assault.

General Marshall had seemed like the most logical choice for this command. The Allied invasion of northwestern Europe had been his idea more than anyone else’s. He was widely respected by the British and American staff officers who would be involved in the detailed planning for Overlord. In addition, Marshall wanted the job badly and was supported in his quest for it by Secretary of War Henry Stimson. In the summer of 1943, the secretary of war had become convinced that only with General Marshall as its commander could British objections to Overlord be overcome. There were also those in Washington, such as FDR and Stimson, who were worried that Marshall’s contribution to Allied victory in the war would be forgotten if he remained in Washington instead of taking on the Overlord command. They, and others, felt that it was imperative that General Marshall not share the fate of the U.S. Army Chief of Staff during World War I, General Peyton C. March, whose name had quickly been forgotten by the public while everyone remembered the name of General Pershing because of the latter’s role as commander of the American Expeditionary Force in Europe in 1917–18.4

There were also, however, strong pressures to keep Marshall in Washington. The strongest such pressure came from General Marshall’s colleagues on the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who helped to convince the president that Marshall’s work as a member of the Combined Chiefs of Staff was so important that it could not be done by anyone else. General Arnold and Admirals King and Leahy urged the president to find another commander for Overlord and thus retain Marshall as army Chief of Staff. On this the president was somewhat torn. He needed Marshall in Washington as his preeminent military adviser, while realizing that Marshall was fully entitled to what was certainly the war’s most prestigious field command for an American army officer. In the end, FDR was forced to concede that General Marshall was irreplaceable as a member of the Combined Chiefs of Staff.5 The president broke the news to General Marshall in December 1943, in a manner that showed how vitally important the Combined Chiefs of Staff had become to the Allied war effort: he used the oft-quoted expression, “I feel I could not sleep at night with you out of the country.”6 It has been suggested that what this interchange really signified was that Marshall himself, not the Combined Chiefs of Staff, had become indispensable.7 Without meaning to detract in any way from General Marshall’s greatness as an individual, I believe that the existence of the Combined Chiefs of Staff organization gave General Marshall a forum in which his talents could shine at least a little bit more brightly than they would have had the CCS never been set up.

Initially hoping to reward General Brooke for his efforts as CIGS by giving the cross-channel command to him, Winston Churchill had changed his mind by late summer 1943. At the Quadrant (Quebec) Conference in August 1943, the prime minister informed President Roosevelt that since American ground troops would greatly outnumber British in the cross-channel campaign, its commander should be an American. At that point Churchill fully expected that the American named would be none other than General Marshall.8 Thus, at Quadrant, Brooke was informed by Churchill that he would not be getting the Overlord command. General Brooke was greatly disappointed to learn that a command that Churchill had frequently promised him had slipped from his grasp. The official reason, that because the Americans would provide a far greater number of the troops for Overlord than the British it seemed only fair that the commander be an American, is certainly a valid one.9 In retrospect, however, it seems odd that Brooke should have been at all surprised at having been rejected for command of an operation that he had tried time and again to kick into the tall grass. Indeed, it seems surprising that Brooke had even wanted the Overlord command, in view of his consistently morose outlook on the whole idea of a cross-channel attack. The Americans were appalled at the prospect of the Overlord command going to Brooke, whose views about the operation had never seemed enthusiastic and often downright obstructionist.10 Secretary Stimson was undoubtedly referring to Brooke when he bluntly summed up the American view just prior to Quadrant in a memorandum to FDR: “We cannot now rationally hope to be able to cross the Channel and come to grips with our German enemy under a British commander.”11 The hypothetical scenario of Brooke commanding Overlord and supervising American generals like Patton and Bradley, who undoubtedly knew that Brooke had no stomach for the operation, is a frightening one.

While both Marshall and Brooke were disappointed that they did not receive the Overlord command, and Brooke’s considerable baggage aside, the fact is that by late 1943 the Combined Chiefs of Staff had become essential for global Allied strategic planning. Accepting a field command would have been a demotion of sorts for any of its members. Taking up the Overlord command would have required Marshall or Brooke to exchange the global outlook they had acquired in strategic thinking in order to become, in the words of General Arnold “just another Theater Commander.”12

General Andrews, a U.S. Army Air Forces officer, was highly regarded by General Marshall. The fact that Andrews had earned the trust of the Chief of Staff, coupled with the fact that he had already proven—in the Caribbean Defense Command and as the commander of the European Theater of Operations of the United States Army (ETOUSA)—that he could handle a theater command, made Andrews a serious contender for the Overlord appointment. Tragically, however, in May 1943 a plane in which General Andrews was returning to the United States crashed while attempting to land in Iceland, killing Andrews and all but one of the other passengers and crew.13

It is vital to keep in mind that by the time Overlord took place in June 1944, the Russians had already won their war. The great Russian victories at Moscow, Stalingrad, and Kursk had set the stage for Operation Bagration, the all-out Russian offensive against German Army Group Center in the summer of 1944. Army Group Center was the only German army group in Russia that could still claim to be a cohesive fighting force in early summer 1944. This Russian offensive, which began a few weeks after the Normandy landings, resulted in the complete destruction of Army Group Center, which had been Hitler’s strongest force in the East. During the Russian summer 1944 offensive, German casualties in Russia were averaging 200,000 men per month.14

Thus, while the planning and launching of the Overlord D-Day landings of June 6, 1944, are considered by many historians to constitute the crowning achievement of the Combined Chiefs of Staff, it needs to be put into perspective. The war in Russia makes clear that Hitler’s armies were already beaten (although still possessed of a nasty sting) by the summer of 1944.15 What Overlord did, perhaps, rather than defeating Germany, was to help define the magnitude of Germany’s defeat. Without a cross-channel invasion, would the Russians have been content to expel Hitler’s armies from Russian soil, gain control of Poland as a buffer state, and then negotiate a peace that left a greatly weakened Nazi regime in power in Germany and perhaps still in possession of occupied France? Was it Overlord that made the difference between a German defeat on the above lines and what actually occurred, that is, the complete destruction of the Nazi regime, the liberation of France and the Low Countries, and the military occupation of Germany by Allied troops? These are hypothetical questions that cannot be definitively answered. The role of the Combined Chiefs of Staff in planning Overlord can, however, be explored.

Part of the opposition of Brooke and Churchill to an Allied cross-channel invasion may have been simply that it was not a British idea. General Marshall was the primary sponsor of the cross-channel strategy, but the British wished to utilize American resources without ceding to the Americans the right to dictate strategy.16 If true, perhaps this feeling (the Americans would call it stubbornness) arose from British resentment that the Americans were relative latecomers when it came to active belligerency in both world wars. Why should these Johnny-come-latelies get to run the show? Indeed, Churchill and Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden found highly insulting a 1942 suggestion by FDR that perhaps the best way for the Allies to approach Stalin would be through personal diplomacy on the part of the American president. The implied exclusion of the British from these proposed inter-Allied negotiations enraged Eden, because, as Warren Kimball writes, “To the foreign secretary, Europe was Britain’s business since the Americans could not be trusted to abandon isolationism and make a permanent political commitment to the region.”17 The feeling that the Americans needed to be tutored by their British allies shows up in a comment made in April 1945 by Churchill’s great friend, and South Africa’s premier, field marshal Jan Smuts, that, as Churchill’s private secretary Jock Colville recorded in his diary, “the Americans were certainly very powerful, but immature and often crude.”18 Future prime minister Harold Macmillan expressed similar sentiments about the Americans during the war.19 If anything, the sentiment felt by Churchill and his military and civilian advisers that “Britain knew best” increased as victory drew nearer. From at least the time of the Teheran Conference onward, Churchill was alarmed about Russian postwar plans for Eastern Europe and about Britain’s declining strength vis-à-vis the two emerging superpowers, the United States and Russia.20

Also undoubtedly on Brooke’s mind were the lingering feelings of inferiority among the British high command, mentioned in chapter 1, regarding the quality of the British army as opposed to that of the German army. In this regard, Alex Danchev has noted that “not until the end of 1942 was it possible convincingly to refute Neville Chamberlain’s laconic aside to Anthony Eden, then secretary of state for war, in the dark days of 1940—‘I’m sorry Anthony, that all your generals seem to be such bad generals.’”21 Portal on at least one occasion said that Winston Churchill shared Brooke’s doubts about the fighting quality of the British army in World War II.22

Then there was the issue of airpower. Marshall seems to have had a better understanding than Brooke of how overwhelming Allied airpower could do much to prevent a recurrence of the trench warfare that Brooke remembered from World War I.23 For instance, General Marshall had been informed by the U.S. Joint Staff planners in May 1943 that in the May 1944 cross-channel assault he envisioned, the Allies would enjoy air superiority of eight to one over the Germans in the vicinity of the invasion area. Indeed, tactical air strikes during the Normandy invasion by Allied fighter-bombers such as the Hawker Typhoon and Lockheed Lightning used in the role of flying artillery disrupted German transportation and supply operations in frontline areas on a massive scale and in a manner that would have been impossible in World War I.24

The most fundamental issue dividing the Western Allies on Overlord was that Brooke believed that it could succeed only after aerial bombing from the West, Allied victories in the Mediterranean, and Russian victories in the East had destroyed the ability of Germany to conduct coordinated military operations.25 He seemed to feel that the war might end in a manner reminiscent of World War I—that is, with a sudden, unexpected German collapse. Brooke saw Overlord as a way to take advantage of such a collapse. Marshall and the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff did not believe that the German armed forces were going to collapse. They felt that Overlord, as an adjunct to the great victories being achieved by the Russians, was essential to ensure the defeat of Germany.26 This feeling among the American members of the CCS was backed up by the U.S. Joint Intelligence Committee, which advised the Joint Chiefs of Staff in October 1943 that the prospect of a sudden German collapse was highly unlikely and that British reports to the contrary were painting an overly optimistic picture.27

Brooke’s attitude was very frustrating to Marshall, because, as Brooke’s biographer points out, for Brooke “the invasion of Western Europe must not take place before those preconditions had been met which would ensure its success.”28 Brooke later spelled out what he felt some of those preconditions had been when he replied to questions posed by J. R. M. Butler and Sir Michael Howard in regard to sections of the Grand Strategy series that he had reviewed. Brooke believed that the Western Allies should use their powerful navies to pursue a maritime strategy.29 This would have meant a return to Britain’s strategy in the Napoleonic Wars, that of maintaining control of the seas, limiting Britain’s commitment of troops on the continent, and outlasting the opponent. This older British strategy may have appealed to Brooke because he had seen in World War I the way British casualties could increase exponentially when Britain enlarged upon its historic maritime strategy in order to become a major European land power—and Britain had been a major land power in World War I. Indeed, by the end of World War I, the British Empire had placed more than 9,000,000 men under arms.30 The majority of these were British-controlled troops on the western front. Brooke further stated to the Grand Strategy authors that a cross-channel invasion in World War II could take place only after “we . . . clear North Africa, open the Mediterranean and regain 1,000 tons of shipping, eliminate Italy, bring in Turkey.”31 (Brooke probably meant to say a million tons here. That was the figure he usually used when discussing the shipping deficit that needed to be made good.)

For General Marshall, such a proliferation of conditions that had to be satisfied before Brooke would consent to a cross-channel assault had a strong air of unreality. It certainly did not seem to represent the outlook of a man who really believed in the operation. It seemed that Brooke wanted to wait until Germany was completely exhausted by its war against the Soviet Union and only then finally undertake Overlord, merely as a means to move an occupation force across the channel to take up garrison duty in an already defeated Germany. It must have seemed to the Americans that Brooke’s strategy would make the war in Europe last until 1948 or 1949.32 Marshall seemed to be more keenly aware than Brooke that in war, you do not always get to choose when you want to fight. The Russians had counter-attacked against the invading Germans outside Moscow (only twelve miles from Red Square) in December 1941 not because they had been ready or eager to do so but because they had had to. The Russians had not had the luxury of waiting until they were completely ready before undertaking the Moscow counteroffensive.

The Russian victory at Kursk in July 1943 seemed to vindicate the American line of thinking that a 1943 cross-channel operation would have been quite feasible. Kursk presented the Western Allies with a golden opportunity (but one that Torch and Sicily prevented them from taking advantage of) to open a second front successfully in Normandy in 1943. Admittedly, Allied casualties in a 1943 invasion of Western Europe would have been heavy. This is especially evident in light of the fact that although the June 1944 Overlord landings took place after the strength of the German air force had been broken, the campaign in Normandy was still a bloody and difficult fight.

British intransigence about Overlord was intensely irritating for both Marshall and King. During the Arcadia Conference in Washington in December 1941 and January 1942, the British had extracted a renewal of the American pledge to concentrate first on the defeat of Germany. That much was perfectly in keeping with General Marshall’s own views. However, after formalizing the “Germany first” pledge, the British rejected Marshall’s plan for a 1942 cross-channel attack and seemed less than sanguine about an attack in 1943, yet insisted that during all of this inaction in Western Europe the United States must keep the war against Japan on the “back burner,” to the disgust of Admiral King.33

Certainly, one of General Brooke’s greatest contributions to the Allied war effort was his ability to neutralize the ill-conceived schemes of the prime minister, such as Churchill’s abortive Jupiter plan to launch an offensive against German forces in Norway in 1943. In such cases, Brooke’s cautious approach to warfare was an important asset to the Allies. To Marshall, King, Arnold, and Leahy, however, Brooke’s desire to agree only to those operations that seemed guaranteed of success beforehand appeared inconsistent with qualities demanded of officers entrusted with strategic decision making for war on a global scale. Admiral Cunningham, Brooke’s colleague on the British Chiefs of Staff Committee, understood that American entry into the war meant that the resources available to the Allies would increase exponentially. Perhaps Brooke was not as successful as was Cunningham in making the transition from thinking in terms of Britain fighting alone to thinking about Britain as part of a coalition with tremendous resources at its disposal. Brooke seemed preoccupied with not losing the war. Marshall was obsessed with winning it.34

Despite the conflict it aroused during CCS meetings, Overlord would never have been possible without the Combined Chiefs of Staff. At the instigation of General Marshall, the War Department in Washington had by the spring of 1942 prepared plans for both the Roundup operation (as the proposed large-scale cross-channel attack was then designated) and the requisite process of building up large American forces in England (known as Bolero).35 From that time on, Marshall pressed relentlessly for the cross-channel invasion to be given top priority. In this effort, the Chief of Staff was backed by his colleagues on the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Arnold being particularly vigorous in his support for Overlord. In-depth planning for the operation began in April 1943 under Combined Chiefs of Staff auspices when a British officer, Lieutenant General Frederick E. Morgan, was appointed by the Combined Chiefs of Staff to serve as chief of staff to the Supreme Allied Commander of the Allied invasion of Western Europe (who, in a perfect example of the complicated and difficult nature of Overlord planning, had not yet been named). The organization Morgan thus set up, commonly referred to as COSSAC, was charged by the Combined Chiefs with responsibility for carrying out the detailed advance planning for a May 1944 cross-channel assault.36

Morgan and his COSSAC staff did much to make Overlord a reality. In addition to Morgan’s ability to solve some of the most difficult planning questions for the operation, the very presence of a British officer working in London to prepare the Overlord plan did a great deal to get the British Chiefs of Staff and their prime minister finally to show some enthusiasm for the undertaking.37 Morgan himself certainly believed in the soundness of Overlord as a strategic concept. His appointment took on greater significance after the Trident Conference of May 1943, at which the U.S. Joint Chiefs received formal British approval for a May 1944 Overlord.38 The positive influence that General Morgan had upon the British members of the Combined Chiefs of Staff goes to show that the subordinate committees, staffs, and organizations of the CCS organization were so important that without them the principals never would have been able to carry out successful coalition warfare on a global scale.

At Trident, the Combined Chiefs decided that Morgan could plan on having twenty-six Allied infantry and three airborne divisions for the assault and set a target date of May 1, 1944. Morgan was also told that after the initial assault phase was complete, a minimum of three divisions per month would be added to the Allied force in France. The Combined Chiefs wanted to see COSSAC’s outline plan by August 1, 1943.39

Morgan made his deadline, completing his plan in July. It was Morgan and his COSSAC staff, keeping in mind the resources that had been allocated by the Combined Chiefs of Staff at Trident, who chose the Caen region in Normandy as the assault area.40 According to Maurice Matloff, Morgan selected the stretch of the Normandy coast running from the River Orne to the Cotentin Peninsula “partly . . . on the grounds that the sector was weakly held, the defenses were relatively light, and the beaches were of good capacity and sheltered from the prevailing winds.”41

While it is true that General Eisenhower and his staff worked out many of the details of the actual landings and directed the operations of Allied forces once they were ashore in France, it is important to note that when Overlord received the CCS stamp of approval in May 1943, Eisenhower was involved in a completely different campaign—the command of Allied forces in North Africa. By December 1943, when Eisenhower was appointed to command Overlord, planning for the operation had been under way by Morgan’s COSSAC staff for seven months. Thus, the Combined Chiefs of Staff had already settled almost all of the largest issues of the operation. They told Eisenhower exactly what forces would be at his disposal, as well as when and where his troops would land on the French coast. Eisenhower did make one critical contribution to the overall plan, which was to insist that the landings take place on a wider front than the three-beach/three-division front envisioned by General Morgan and the COSSAC planners. Eisenhower’s idea, which may have originated with General Montgomery, was to land on five beaches, which would mean at least five divisions landed by sea on the first day.42

One reason for Brooke’s lack of enthusiasm for the cross-channel attack was his sense that the Americans did not understand how vast an operation Roundup/Overlord would have to be. Marshall’s desire to undertake the operation, at least in limited fashion, in 1942 seemed to Brooke the height of fantasy. Brooke noted during Marshall’s April 1942 visit to London that Marshall had urged that the Western Allies put troops ashore on the coast of France in September 1942. Marshall promised that American forces would be available for such a campaign. However, Brooke was astounded to learn that the Americans would be able to make available only two and a half of their own divisions for a September 1942, assault.43 Brooke concluded justifiably that this would be “no very great contribution. . . . Furthermore they had not begun to realize what all the implications of their proposed plan were!”44 It should be noted, however, that the pace of the Bolero transfer of American forces to England in preparation for operations on the continent was expected to increase dramatically in late 1942 and early 1943. The Combined Staff planners stated in May 1942 (before the planning for the North African invasion, Torch, threw such plans into disarray) their opinion that there would be 51,000 American troops in England by July 1942 and that these troops could be ready to participate in a campaign in France in September. By September 1, 1942, available shipping would allow 105,000 American troops to be transported to England, and at least 794,000 American troops would have arrived by April 1, 1943.45

With the aforementioned doubts on his mind, it is therefore strange that a few days after he had complained about Marshall’s two and a half divisions, Brooke and his colleagues on the British Chiefs of Staff Committee would, in what Brooke referred to as a “momentous meeting,” agree to Marshall’s plans for a cross-channel invasion in 1943 at the latest, perhaps even a limited campaign in 1942.46 The proposed limited operation to seize a foothold in France in 1942 was known as Operation Sledgehammer. Marshall therefore returned home thinking that he had secured British agreement to, at the very least, an April 1943 cross-channel assault involving roughly forty-eight American and British divisions. Brooke’s biographer admits that this was an odd promise for the CIGS to give, in that Brooke was by no means convinced at that time that a 1943 Overlord was the correct strategy for the Allies to follow. Such a strategy entailed large risks, a situation Brooke found intolerable.47

Part of this ambiguity may have been due to the fact that while their common language was invaluable in forging the close alliance between Britain and the United States, differences in the way they expressed themselves caused problems between the British and American members of the Combined Chiefs of Staff. According to Sir David Fraser, “When the British, having considered the American proposals at the level of prime minister and Chiefs of Staff, returned their final answer they gave an impression of more harmony than really existed. It is a British characteristic to find a formula of agreement in order to preserve some sort of unity in an organization, while postponing a crunch of opinion until real decisions on action have to be taken. It is an American characteristic to take at literal value the written word.”48

Brooke apparently hoped to postpone the “crunch of opinion” for a very long time. After the war he reiterated that he had never had any intention of allowing British troops to participate in a cross-channel attack in either 1942 or 1943, unless Germany were to undergo a sudden collapse beforehand. Brooke found it frustrating that Marshall regarded Allied operations in North Africa and Italy not as stepping-stones toward a coup de grâce against Germany but rather as separate campaigns, undertaken seemingly to mark time. The CIGS felt that Marshall did not appreciate the benefits that might accrue to the Allies from a maritime, Mediterranean strategy.49 Indeed, at the Quadrant Conference General Brooke pressed for Allied troops to advance into northern Italy, which was farther north than Marshall and his American CCS colleagues wanted to go in the Italian campaign. The British themselves were not united on the northern Italy idea. Sir Charles Portal favored confining Allied operations to seizing the airfields in southern Italy and invading Sardinia. Brooke was perplexed and disappointed that General Marshall did not share his own view that the Italian campaign would be complementary to Overlord, by way of pulling German troops into Italy, troops that the Germans would then be unable to use to repel the cross-channel invasion.50 Perhaps Marshall’s view that the Italian campaign was a distraction from, rather than a benefit to, Overlord would have been more clear to the CIGS had Brooke taken a moment to ponder an irony of his view of the supposedly related nature of Italy and Overlord—the fact that, as Mark Stoler has written in regard to a critical stipulation demanded by the British, the Overlord commander’s brief would extend only to controlling Allied forces in “northwest Europe, as the British insisted the Mediterranean remain a separate theatre and be under British command.”51

Indeed, it was the American attempt to obtain a unified command in Western Europe and the Mediterranean that caused Sir John Dill’s name to be put forward in regard to the command of Overlord in November 1943 by the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff. The Americans reasoned that the British Chiefs of Staff could have no objection to giving their colleague Dill such a truly unified supreme command. For their part, the Americans felt that Dill was the one British officer whom they would have no hesitation whatsoever in accepting as an overall commander for Overlord.52 In pointing out his capabilities for such a command, the Joint Chiefs of Staff praised Dill to the president in a memorandum authored by Admiral Leahy, saying that “Sir John Dill is well known to our officials and to the American public. He has worked on an intimate personal basis with the U.S. Chiefs of Staff since our entry into the war. We have the highest opinion of his integrity of character and singleness of purpose. He understands our organization, our characteristics, our viewpoint on many subjects, and our way of doing business.”53

The suggestion of Dill by the Americans as commander of operations that would include the cross-channel attack was also undoubtedly a manifestation of the fact that he was infinitely more palatable to the Americans than Brooke. Everything about General Brooke seemed to bother the Americans, not just his foot-dragging in regard to the cross-channel attack. Andrew Roberts has noted that the French-born Brooke had always been bilingual. His manner of speaking immediately put Americans on guard when they first made his acquaintance. In regard to French and English, Roberts notes, Brooke “spoke both languages very fast, something that some Americans were to come to dislike and mistrust.” Then, as now, fast talkers make people nervous.54

Putting Dill forward as a possible super-commander in Europe coordinating Overlord and Mediterranean operations was also undoubtedly a bribe on the part of the Americans, an attempt to stop British backsliding in the form of the continuing post-Trident and post-Quadrant doubts expressed by Churchill and the British Chiefs of Staff about the cross-channel attack. Marshall’s biographer Forrest C. Pogue and General Ismay in his memoirs both say that British refusal to combine the Mediterranean and Overlord commands was a major reason why General Marshall did not get the Overlord command. President Roosevelt apparently feared that the American press and public might think a general of Marshall’s seniority and stature was being unfairly punished if he were to have his responsibilities restricted to one part of the European theater—even though Marshall himself dearly wanted the appointment.55

General Marshall clearly did not see North Africa and Italy as part of any comprehensive strategy. For him, they were wasteful diversions. Why then during the Trident Conference in Washington in May 1943 did Marshall concur in a Combined Chiefs of Staff decision that seemed to make an Allied campaign in Italy inevitable—or perhaps more appropriately, unavoidable? In a directive prepared by the Combined Staff Planners at the end of Trident, General Eisenhower, then commanding the Allied forces in North Africa, was “instructed, as a matter of urgency, to plan such operations in exploitation of HUSKY [Sicily] as are best calculated to eliminate ITALY from the war and to contain the maximum number of German forces.”56 The directive went on to say that Eisenhower’s plans to detach Italy from the Axis camp had to be made with the understanding that they were secondary to, and in support of, a major Allied campaign to land twenty-nine Allied divisions in northwestern France on May 1, 1944. The Combined Chiefs wanted to see Eisenhower’s plans by July 1, 1943.57

Andrew Roberts speculates that at a CCS “closed session” meeting during the Trident conference the Americans engaged in some horse trading: the British got approval for an Allied campaign in Italy, while the Americans forced the British to put in writing that the cross-channel attack was not only “on” for spring 1944 but would be the paramount Allied campaign in the European theater that year. Trident marked the first occasion on which the Combined Chiefs employed a closed session—no witnesses present or minutes taken. The practice would become more common at future Allied summit conferences as debates between British and American Combined Chiefs of Staff members became more bitter.58

Much of Marshall’s bitterness over the decision to undertake Torch, which had received final approval by FDR and Churchill on September 5, 1942, stemmed from a feeling that he had been badly manipulated by the British and his own president. Marshall’s efforts via Bolero to concentrate U.S. troops in England for an early cross-channel attack only made it easier to carry out Torch, an operation he opposed.59 Marshall had intended that the British Isles would serve as a staging area for a cross-channel attack, not for operations in North Africa or the Mediterranean. Historians have noted that for political reasons President Roosevelt felt it imperative to get American troops into action against German troops somewhere—indeed, anywhere—before the end of 1942 and that this helps to explain FDR’s approval of Torch.60 However, for the president, there may have been more than politics involved. After Allied troops were ashore in northwest Africa, FDR began to feel that Allied operations in the Mediterranean might be a good way to get at Germany after all.61 According to Mark Stoler, “Unlike the JCS, Roosevelt saw the Mediterranean as a vital part of the European theater where military gains against Germany were quite possible.”62

The U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff saw no value in the Torch operation. Marshall saw the CCS 94 document (see chapter 3) and Torch as a surrender to a peripheral strategy in Europe only for the time being and so that fifteen American air groups could be released from Europe to the Pacific Theater in the summer of 1942.63 The British Chiefs of Staff, on the other hand, felt that Torch was a viable operation. Brooke had been skeptical at first about the validity of Torch but changed his mind during the summer of 1942 and joined Pound and Portal in supporting the operation.64 Brooke’s diary entries between June and September 1942 demonstrate the evolution of the thinking of the CIGS in regard to Torch.65 British forces were already heavily engaged in North Africa, and much of British strategy in 1940–42 had been geared toward the Mediterranean area in general. A fundamental issue here was that, as Matloff and Edwin Snell put it, “Torch . . . fitted easily into British strategy; American strategy had to be fitted to Torch.”66

In the autumn of 1943, after the date for Overlord had already been set by the Combined Chiefs of Staff as May 1, 1944, General Marshall wrote for the president a report outlining what he perceived as British reluctance to participate in an Allied campaign against the Japanese in Burma. The reasons Marshall identified go a long way toward explaining the very different approach taken by the British and American members of the Combined Chiefs of Staff to strategic planning in general, and the question of Overlord in particular. Thus Marshall’s report, although primarily concerned with Burma, helps explain the bitterness of the Anglo-American debate about Overlord. In regard to Burma, and under the heading “British Pessimism Retards All-Out Support,” Marshall informed FDR that British forces in India seemed to want no part of a campaign in Burma. The Chief of Staff claimed that the British had little or no faith in the fighting abilities of the Chinese and Indian infantry divisions that would be needed for such an operation and that this had made the British overly pessimistic.67 The crux of Marshall’s argument, however, was that in regard to British forces in India, “their approach appears to be that of the Quartermaster rather than that of the General. Whereas we determine upon a strategic operation as being necessary and then move heaven and earth to support it, the British staff in India appear too sensitive to logistical limitations and too indifferent to means of removing them.”68 Although Marshall intended this to be a criticism of high-ranking British military officials in India, such as Field Marshal Sir Archibald Wavell, it seems also to describe perfectly Marshall’s sense of the reasons behind the reluctance of the British members of the Combined Chiefs of Staff to undertake a cross-channel invasion at the earliest possible moment.

Two qualifications should be made in regard to Marshall’s complaint. In the case of operations in Burma, the great success of American forces in the Central Pacific proved that the British were most likely correct in viewing Burma as the wrong theater for full-scale operations against the Japanese. Secondly, the different approaches taken by the British and the Americans to the planning of any operation were related to the fact that the United States possessed unlimited resources while Britain did not. The latter point is well illustrated by Admiral Cunningham’s experiences in the Mediterranean theater. His operations there in 1940 and 1941 had been very difficult, because ships, personnel, aircraft, and supplies were always in short supply. The situation was much different when Cunningham returned from the British Joint Staff Mission in Washington in the summer of 1942 to take up his post as Allied naval commander for Torch. Vast American resources were at his disposal in a combined operation, and Cunningham found that he could have anything he needed. This was a welcome improvement. However, it was also a situation that required Cunningham to make an adjustment in his thinking, to adapt to a new and unexpected situation.69 General Brooke was less successful in doing so.

In his biography of Brooke, Sir David Fraser gives the impression that Pound and Portal were as dead set against an early Overlord as Brooke. This does not in fact seem to have been the case, particularly in regard to Portal. The chief of the Air Staff indicated during the spring of 1942 that he considered Sledgehammer a “real possibility” for 1942.70 A month later, Portal indicated that he would not be opposed to undertaking Roundup/Overlord in 1943.71 In fact, during the summer of 1942 Portal informed the COS Committee that for a 1943 cross-channel campaign, he was prepared to accept a situation in which “virtually the entire Metropolitan Air Force [i.e., RAF units based in southeastern England] will be engaged in effect on Army Support in the widest sense, including the achievement of air superiority over the battle area [in France].”72 This open-mindedness on the question of the cross-channel invasion reflected in Portal’s reports also goes against the view of his biographer, Denis Richards. According to Richards, the chief of the Air Staff agreed with General Brooke that it would be unwise for the Western Allies to launch a cross-channel attack in either 1942 or 1943.73 It is possible, however, that Portal’s enthusiasm for an early campaign in France may have been dampened somewhat once the final decision was taken in September 1942 that Operation Torch was “on” for 1942. At this point, Admiral Pound and Field Marshall Dill seemed to be the British CCS members whose views were most in accord with those of the Americans. Admiral Pound sympathized with General Marshall and Admiral King in their disappointment upon realizing that undertaking the Torch operation in 1942 meant that their would be no cross-channel attack in 1943.74

Field Marshall Dill and the British Joint Staff Mission in Washington, perhaps falling under American influence, seemed also to be more optimistic than Brooke in regard to a 1943 cross-channel campaign. They suggested in June 1942 that a supreme commander for such an operation should be appointed as soon as possible and that this individual should be supported by a combined, interservice, British-American staff.75

In the spring of 1942 Admiral King was not opposed to the Bolero transfer of American forces in the British Isles in preparation for an early cross-channel campaign. However, King did feel that it was pointless and dangerous to send American forces to Europe until the Pacific situation was at least stabilized. He saw the Pacific as more urgent, something that had to be dealt with right away. Douglas MacArthur was trying to make the same point, although his reasoning was somewhat weak—MacArthur portrayed the Pacific as a second front that would help Russia.76 In one sense, MacArthur was accurate, in that being embroiled in a war with the United States kept the Japanese from taking advantage of the Russo-German war by invading maritime Siberia.

One reason that the American members of the Combined Chiefs pressed hard for an early cross-channel assault is that they were keenly aware of the terrible struggle in which their Russian ally was engaged. While the Western Allies allowed the summer of 1943 to pass with no cross-channel attack, the Russians and the Germans deployed between them in July some three thousand armored vehicles at Kursk in what would be the largest tank battle in history. Roughly 25,000 German soldiers were killed on the first day at Kursk (July 5)—a death toll that would rise dramatically in the next two weeks. In addition, hundreds of German aircraft and tanks were to be destroyed. The Russians’ own losses were also heavy, but Kursk was a great victory for them. After the battle at Kursk ended on July 25, 1943, German forces in Russia would know only retreat until the end of the war.77 Unlike his American CCS colleagues, however, Brooke had little sympathy for the Russians. Andrew Roberts summarizes Brooke’s anti-Bolshevik sentiments nicely; after dismissing claims that the British expected the Americans to fight Hitler on their own, Roberts writes that “a much fairer criticism of Churchill and Brooke was that they were willing to fight not to the last American, but rather to the last Russian.”78 From the very beginning of Barbarossa, the Russians were compelled to engage the bulk of the troop strength of the German army. Indeed, 80 percent of the casualties sustained by the German army in World War II occurred in the war with Russia.79 Alex Danchev illuminates this disparity by noting that “in December 1942, with the echo of Alamein still ringing in the ears, the Western Allies engaged some six German divisions. The Soviets faced 183.”80

Allowing the defeated German forces no respite, the Russians immediately followed up their victory at Kursk by liberating Belgorod on August 5 and Kharkov on August 23. These victories were greatly aided by the fact that by summer 1943, the Russian air force was coming of age. Indeed, at the time of Kursk, the Russian air force (administratively divided into “air armies,” signifying the close air support that Russian combat aircraft provided to the Red Army during the war) outnumbered Luftwaffe aircraft by a margin of almost three to one. The German air force on the Eastern Front was weakening rapidly, while greatly expanding Russian aircraft production was beginning to tell.81 The momentum of the Russian advance would increase dramatically during 1944. In July of that year, when German Army Group Center had finally been destroyed in the Bagration campaign, Russian armies of the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Belorussian Fronts crossed the Polish frontier. For the remarkable achievement of expelling German forces from almost all Russian territory the Wehrmacht had occupied in 1941 and 1942, the Red Army had required only two months to push the Germans four hundred miles to the west.82

As they rapidly moved westward during 1944, the soldiers of the Red Army found plentiful evidence of the atrocities inflicted upon Russian civilians by the German army. Historians such as Omer Bartov have vividly chronicled the barbarity of German occupation policy in Russia.83 Indeed, the mountain of such evidence makes it difficult to know where to begin when choosing examples. For instance, in the span of just two days in late September 1941 more than 33,000 Russian Jews from Kiev in the Ukraine were shot by SS and regular German army firing squads and were buried in a ravine at Babi Yar.84 There is no shortage of official German documents outlining the savage occupation policy to be followed by German forces in Russia. Field Marshal Walter von Reichenau issued a chilling order to the German troops (that is, regular army troops) under his command in Russia on October 10, 1941: “In the eastern sphere the soldier is not simply a fighter according to the rules of war, but the supporter of a ruthless racial (völkisch) ideology and the avenger of all the bestialities which have been inflicted on the German nation and those ethnic groups related to it. . . . For this reason soldiers must show full understanding for the necessity for the severe but just atonement being required of the Jewish subhumans.”85

Whether it was during the advances made by the German army into Russia in 1941–42 or in that same army’s retreats after Stalingrad and Kursk, looting, arson, rape, and murder were indiscriminately inflicted upon Russian civilians by the Wehrmacht, to say nothing of the more than 3,000,000 Russian prisoners of war who died of abuse, starvation, and exposure in German captivity.86 The fate of Russian prisoners in German hands is a particularly heinous crime, because prisoners of war are not supposed to die at all. They are supposed to be cared for and treated humanely. The number of Russian POWs who died in German captivity is more than six times the total number of Americans killed in the war and is still only a fraction of the 27,000,000 Russians who died. German troops often did not even bother to take prisoners, instead simply shooting out of hand any Russian soldier who tried to surrender. The ethnic groups earmarked for destruction in von Reichenau’s field order quoted (in part) above went beyond Russian Jews to include Slavic peoples in general, who had been declared by Hitler to be “subhumans.” This mind-set ensured that the German army, in its invasion of the Soviet Union, would be conducting a genocidal campaign that would claim the lives of millions of Jewish and non-Jewish Russian civilians, to say nothing of the millions of Russian soldiers who were killed in combat or died in squalid open-air POW camps into which they were forced in the dead of winter.87

Holocaust historian Richard Rhodes vividly describes how routine became mass shootings of Russian civilians, Jewish and non-Jewish, by the German invaders during Barbarossa. One eyewitness account, which mentions an SS officer named Friedrich Jeckeln, describes a mass execution of Jews in the Ukrainian town of Schepetovka during the summer of 1941: “Women and children were among those shot. Jeckeln said: ‘Today we’ll stack them like sardines.’ The Jews had to lie layer upon layer in an open grave and were then killed with neck shots from machine pistols, pistols and rifles. That meant they had to lie face down on those previously shot [whereas] in other executions they were shot standing up and fell into the grave or were dragged in.”88

So terrible was the savagery of the German army toward the Russian people that, Omer Bartov suggests, after the war German veterans of the Eastern Front had to engage in a form of “collective amnesia” in order to disguise from themselves the fact “that they [i.e., regular German army troops, not just the SS] had all taken part in a huge criminal undertaking.”89 Whatever Stalin’s own crimes, the Russian people certainly had done nothing to deserve such a horrific fate. Yet Churchill and Brooke were content to let them wait for their second front.

A 1943 Overlord would have been like Guadalcanal—a bitter, drawn-out campaign with a greater risk of failure than the campaign that was actually launched on June 6, 1944. The Allies had air superiority in Western Europe by June 6, 1944, but they did not yet have it a year earlier. In a 1943 Overlord, British and American fighter pilots would have had to establish air superiority over the beachhead dogfight by dogfight against the Luftwaffe. However, the proximity to the invasion beaches of the unsinkable aircraft carrier that was England would have made this task possible. The Allies had plenty of fighter aircraft in mid-1943; the problem was that most of them were deployed in the Mediterranean.90 What the Allies did not yet have was the American long-range P-51 Mustang fighter, which throughout 1944 enabled American heavy bombers flying from England to enjoy effective protection all the way to Berlin and back. Nonetheless, and even without Mountbatten’s Habbakuks but sans the Mediterranean diversion, the range handicap of the P-47, P-38, Spitfire, and Typhoon fighters the Allies would have employed in a 1943 Overlord would have been offset by the availability of refueling facilities just across the channel in England. Then, once a beachhead was established in France, forward airfields could be set up there—as was actually done when Overlord took place.

The Guadalcanal analogy seems especially apt in regard to a 1943 Overlord. One of the reasons, perhaps the most important reason, Admiral King favored undertaking the Guadalcanal operation in the South Pacific in August 1942—a time when American forces were actually far from ready to take the offensive anywhere—was that, as he himself wrote that spring, “the best defense is offense.” In the same document, King went on to say that “no fighter ever won his fight by covering up” and absorbing blows. You have to fight aggressively and offensively as best you can, regardless of how unprepared you are.91 Marshall, Arnold, and King were willing to employ such a philosophy in regard to Overlord. Brooke definitely was not.

By the time of the Trident Conference in May 1943, President Roosevelt had come to agree with the idea put forth by the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff that the cross-channel assault should have precedence over any other Allied activity in Europe during 1944, but the British Chiefs were getting mixed signals from the prime minister. According to Fraser, “Churchill sometimes argued for early invasion when under great Allied or Parliamentary pressure, but he greatly feared a costly disaster in the West and he was always half-ready to be persuaded [to abandon the idea].”92

At the Trident Conference, the U.S. Joint Chiefs estimated that the Allies would be able to field thirty-six divisions for an April 1944 Overlord.93 A few months earlier, the British Joint Planning Staff had pointed out that because the American Bolero buildup of forces in England had been reoriented toward the Torch operation, the bulk of the troops for any 1943 cross-channel campaign would have to be British, as would most of the landing craft and their crews.94 This left Marshall with precious little room to maneuver, and it demonstrates how harmful the logistical inroads made by the Torch campaign were to the planning process for the cross-channel assault. As it turned out, the forces involved in the initial landings at Normandy on June 6, 1944, comprised equal numbers of British and American troops. (The “British” total included, on the first day, one Canadian division. Of the entire twenty-nine Allied divisions involved in Overlord, four were Canadian.) However, because of the massive buildup that followed, the vast majority of the Allied troops participating in the liberation of France and the invasion of Germany from the west were, in fact, American.95

In March 1943 the British Joint Planning Staff began to evince in regard to Overlord a guarded optimism that would become more apparent by the time of Trident. Echoing the sentiments of the British Joint Staff Mission in Washington, the British Joint Planning Staff recommended that a director of planning for a 1944 cross-channel assault be appointed forthwith. The British planners also felt that such an assault had become feasible under two possible scenarios. The Allies could carry out this operation in 1943 should Germany collapse suddenly, or in 1944 even against a vigorous defense.96 The British Joint Planning Staff therefore seems, in this instance, to have been more enthusiastic and flexible about Overlord than were the principal British members of the Combined Chiefs of Staff. This was no doubt due at least in part to the efforts of the senior member of the British Joint Planning Staff, Captain Charles Lambe, RN, who, as we have seen in regard to the debate over strategy in the Pacific, had proven to be a very farsighted individual who, like Dill, was always capable of understanding the point of view of his American allies.

At the Quadrant Conference at Quebec in August 1943, the Combined Chiefs of Staff gave their approval to the outline plan for the cross-channel assault that had been prepared by General Morgan and his COSSAC Staff. Even then, however, it was a full-time job for the American CCS members to keep their British counterparts convinced as to the paramount stature of Overlord for 1944. The American members of the Combined Chiefs of Staff constantly pressed the point that nothing must interfere with Overlord or Anvil. (The latter operation, subsequently known as Dragoon, was the plan to support Overlord by landing Allied troops in the south of France from the Mediterranean.) Both operations were initially set for May 1944.97 The hand of the Americans, in terms of insisting on a 1944 Overlord, had been immeasurably strengthened by the summer of 1943 by the rapid expansion of their army and the flood of supplies and weapons from their factories; the Americans could insist on controlling the Western Allied agenda for 1944 and beyond. Indeed, by January 1944, aside from the large numbers of American troops in the Pacific theater, the number of American troops deployed against the German army finally exceeded the British total.

Most importantly, the United States had not yet exhausted its manpower reserves, while Britain had. When the Teheran Conference convened in late November 1943, Stalin took the side of the Americans against Britain by insisting on a 1944 Overlord, with the Anvil invasion of southern France in support thereof. At Teheran Stalin embarrassed both FDR and Churchill by obliging them to admit that a commander for Overlord had not yet been appointed.98 In the wake of the conference the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff wished to curtail operations in the Mediterranean (except, of course, Anvil/Dragoon), as soon as possible in order to counter a disturbing trend, namely, that the Mediterranean campaigns tended to absorb far more resources than the Americans had hoped. For example, to provide air cover for Torch, the Americans had been forced to strip their Eighth Air Force, based in England, of most of its aircraft, to the detriment of the American bombing campaign from England against Germany that began in January 1943.99

As early as November 1942, the British Joint Staff Mission in Washington pointed out to the British Chiefs of Staff that the Americans were already very nervous about exploiting the Torch campaign in North Africa, fearing that it would lead the Allies into an open-ended Mediterranean commitment. This warning to their masters in London is contained in a document that has become either legendary—or notorious, depending on one’s point of view—because in it the members of the British delegation admit that the Americans “think that they have been led up the Mediterranean garden path” by their devious British allies.100

Until the time the Overlord landings actually took place, this fear of being saddled with wasteful Mediterranean commitments never abated for the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff. They wrote shortly after the Quadrant Quebec Conference that they were appalled to see the British Chiefs of Staff “renounce what they call the ‘sanctity of Overlord’ principle.”101 What had incensed the Joint Chiefs to this extent was a report prepared by the British Chiefs of Staff in November 1943 that in a rather convoluted fashion seemed to withdraw British backing for a firm target date, in particular, and generally for Overlord as the Allied campaign for 1944. The British chiefs indicated that they wanted to see Overlord reevaluated from month to month in the light of continuing Russian victories and Allied successes in the Mediterranean, such as the withdrawal of Italy from the Axis bloc. With this in mind, the British chiefs expressed reservations about withdrawing troops and equipment from the campaign in Italy in order to prepare for Overlord. The British disliked being tied to an ironclad timetable, set at Trident and reaffirmed at Quadrant, committing the Western Allies to a cross-channel assault in May 1944.102

The Americans viewed this news from their British colleagues as a severe affront. It seemed that the British Chiefs of Staff wanted to scrap the plans for combined operations in northwest Europe—plans that had been so difficult to formulate. The Americans called the attention of the COS Committee to the British promises that had recently been given, stating that “the British Chiefs of Staff [have recently] reaffirmed and accepted that it is part of our basic strategy that we ‘concentrate maximum resources in a selected area as early as practicable for the purpose of conducting a decisive invasion of the Axis citadel’ (CCS 319/5). However, the U.S. Chiefs of Staff must now construe the subject British memorandum as a denial of this principle.”103

The British countered by claiming that they had no desire to cancel the cross-channel attack out of hand. Instead, they wanted to put it back on the limited footing that had been discussed for it in 1942 (i.e., a Sledgehammer-type operation to seize a foothold on the French coast or to hastily move large numbers of Allied troops into France to take advantage of a German collapse).104 Brooke, Portal, and Cunningham were anxious to get out of a situation in which they claimed they were forced to “regard Overlord on a fixed date as the pivot of our whole strategy on which all else turns.”105 One aspect that particularly enraged the British was the American insistence, grudgingly accepted by the British Chiefs of Staff Committee at Trident, that seven Allied divisions be pulled out of the line in Italy in the fall of 1943 and sent back to England in order to prepare for their upcoming role in Overlord, a move that definitely tossed Mediterranean operations into the back seat as far as Allied planning was concerned. The Americans insisted at Quadrant that the wavering British reaffirm this part of the Overlord plan.106

The British did not seem to feel that the Allies needed one paramount campaign for 1944. They felt that there could be a limited cross-channel assault to complement Allied operations in the Mediterranean—an ironic view for the British to take, in that a limited cross-channel assault was exactly what they had refused to consider in 1942. To the British chiefs this now seemed like a good plan, because it would mean engaging German forces on a broad front, forcing the Germans to disperse their resources.107 The American viewpoint was just the opposite. The Joint Chiefs of Staff favored concentration of the bulk of Allied resources at one point, northern France. For them, Allied operations in the Mediterranean were to be only subsidiary to, and diversions to assist, Overlord. The Americans were alarmed that as late as the Cairo Conference, which had immediately preceded Teheran, the British had seen no need to allot either a specific date or specific numbers of troops, aircraft, ships, etc., to the Overlord plan.108 The U.S. Joint Chiefs spelled out their position as follows: “We are of the opinion that changes in the situation since Quadrant militate for, not against, the launching of Overlord on or about 1 May 1944, and we cannot agree that a firm target date is not essential to its success. . . . We believe that extensive operations in the Eastern Mediterranean will weaken and indefinitely postpone the decisive operation in northwestern France. This would be unacceptable to us.”109

The hand of the American members of the Combined Chiefs had been strengthened during the Trident Conference in May 1943 by the fact that, like them, the president had had enough of the Mediterranean and was ready to back fully their plans for a spring 1944 cross-channel assault.110 In the months that followed, FDR proved willing to support all of the ideas of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in regard to Overlord, including the operation designed to support it by landing Allied troops in southern France (Anvil/Dragoon). The Americans encountered opposition from the British Chiefs of Staff and Churchill in regard to Anvil as well as Overlord. A few weeks after the Normandy landings began on June 6, 1944, the prime minister begged Roosevelt to reconsider the operation against southern France, hoping to convert him to the British alternative of expanded operations in Italy and the Balkans.111 The president remained unmoved. He declared to Churchill, “On balance I find I must completely concur in the stand of the U.S. Chiefs of Staff.”112 The president went on to say that the British plan to devote Allied resources in the Mediterranean almost exclusively to an attempt to move through northern Italy into the Balkans was unacceptable. He, like the U.S. Joint Chiefs, favored the principle of the concentration of Allied forces. The British plan entailed dispersion of effort. Overlord must have priority, said the president, and Anvil must be mounted from the Mediterranean to support it. The Anvil/Dragoon landings in southern France duly took place on August 15, 1944.113

The British made one last effort to kill the Anvil operation. The British Joint Staff Mission in Washington prepared in August 1944 a report on behalf of Brooke, Pound, and Cunningham that proposed using the forces detailed to the southern France operation for a descent upon the coast of Brittany, nearer the action in Normandy.114 The Americans prepared their veto on the same day: the U.S. Joint Chiefs claimed that it would be reckless and unnecessary to change the landing area for the Anvil forces from the Riviera to Brittany. They informed the British chiefs that General Eisenhower was already capable of moving reinforcements into northern France through the Normandy beachhead that he controlled. Moving the Anvil force to Brittany would, the Americans felt, change the character of that operation from an independent assault designed to draw German forces away from the Normandy beachhead area into a secondary operation that would serve only to move Allied reinforcements into northern France.115

It was extremely frustrating and bewildering to the Americans to find that after they had bowed to what they viewed as a British obsession with operations in the Mediterranean by delaying Overlord so as to participate in Mediterranean campaigns of questionable strategic necessity (i.e., Torch, then Sicily, then the Italian campaign), the British would so vehemently oppose the one Mediterranean operation, Anvil, that seemed to promise immediate concrete gains in the war against Germany. That such serious debates about the Overlord campaign should persist even after the operation was under way shows what a volatile issue the cross-channel campaign proved to be for the Combined Chiefs of Staff. The resiliency of the CCS organization was, in turn, displayed by the fact that despite the widely differing viewpoints of its members and the overall bitterness of the debate, an effective Overlord plan and campaign emerged. Of course, the Combined Chiefs of Staff did not operate in a vacuum. That Overlord took place at all was due to the persistence of General Marshall and his U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff colleagues in the face of British opposition; to the support the Americans received at Teheran from Stalin; to the waning of FDR’s interest in Mediterranean operations; and to the fact that by early 1944 the United States was definitely the senior partner in the Western alliance.