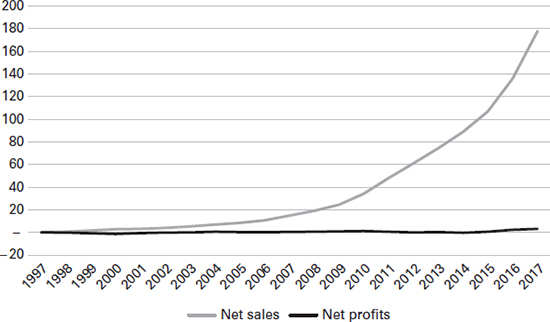

Figure 2.3 Playing the long games: Amazon sales vs profits

SOURCE Author research; Amazon 10-Ks

In the early years, however, a whole lot of people were betting against Amazon. By 2000, the year the dot-com bubble burst and Amazon’s sixth in operation, the retailer had yet to report a profit and was haemorrhaging millions of dollars in losses. Wall Street analysts were convinced Bezos was building a house of cards,18 with Lehman Bros analyst Ravi Suria predicting Amazon would run out of cash in a matter of months unless it could ‘pull another financing rabbit out of its rather magical hat.’19 Suria wasn’t alone here. The same year, finance magazine Barron’s put out a list of 51 internet companies that were expected to go bust by the end of 2000. The Burn Rate 51 included now-forgotten names like CDNow and Infonautics – and Amazon.

Headlines such as ‘Can Amazon Survive?’20 and ‘Amazon: Ponzi Scheme or Wal-Mart of the Web?’21 illustrated doubts over Amazon’s future. Amazon was expected to be yet another victim of the dot-com bubble.

Despite the broader scepticism and genuine befuddlement over its unconventional business model, Amazon managed to persuade enough shareholders by telling a compelling story. He requested their patience and surprisingly they agreed. ‘I think it comes down to a consistent message and consistent strategy, one that doesn’t deviate when the stock goes down or goes up’, said Bill Miller, the Chief Investment Officer at Miller Value Partners.22 Today, investors are often confused when Amazon reports the occasional profit – they’ve come to expect Amazon to recycle any cash back into the business.

Former Amazon executive Brittain Ladd believes that companies either play a finite or infinite game. With a finite game, the company believes it can beat their competitors. It is characterized by an agreed set of rules and clearly defined mechanisms for scoring the game.

Speaking to the authors, Ladd commented:

Amazon, however, plays an infinite game where the goal is to outlast competitors. Amazon understands that competitors will come and go. Amazon understands that it can’t be the best at all things. Amazon has made a strategic decision to place its focus on outlasting its competitors by creating an ecosystem that flawlessly meets and serves the needs of consumers across an ever-expanding array of products, services and technology.

Cheap capital and sustainable moats

Amazon clearly play by their own set of rules. Without Bezos’ vision, they wouldn’t have earned the confidence of the investment community. Without the confidence of their shareholders, they wouldn’t have been able to invest in the necessary infrastructure for the core e-commerce business or to innovate well beyond the borders of retail, adding those critical spokes to the flywheel. There would be no AWS, no Prime, no Alexa. Amazon wouldn’t be Amazon.

Speaking at a logistics conference in 2018, Sir Ian Cheshire, Chairman of Debenhams, noted that the average retailer reinvests 1–2 per cent of its revenues into systems. Amazon reinvests 6 per cent. ‘That’s a factor of 5:1 which is going back into a better toolkit, testing and infrastructure’, he said.23

NYU professor Scott Galloway takes this one step further with this assertion that Amazon is ‘playing unfair and winning’. He explains: ‘They have access to cheaper capital than any company in modern history. Amazon can now borrow money for less than the cost of what China can borrow money [for]. As a result, they’re able to throw up more stuff against the wall than any other firm.’24

As a competitor, how can you possibly keep up with a company that has zero obligation to report a profit? A company whose primary expectation from their investors is to keep ploughing money into new areas of growth?

‘You really develop very sustainable moats around a business when you run it at low margins’, says Mark Mahaney, RBC Capital Managing Director who has covered internet stocks since 1998. ‘Very few companies want to come into Amazon’s core businesses and try to compete with them at 1 per cent margins or 2 per cent margins.’25

And that’s just the retail business. Many of Amazon’s ‘non-core’ businesses are in fact loss leaders. Prime subscription fees may now be a healthy top-line contributor, but most analysts agree that Amazon is likely still losing money on postage in a bid to encourage more frequent shopping.26 Meanwhile, its devices such as Kindles and Echos27 are typically sold at cost price or at a loss. Like Google, Amazon aims to lock in as many shoppers as possible and then make money on the content purchased through the device28 (as well as gain valuable data about buying habits). Given that Echo owners spend 66 per cent more than the average Amazon shopper, the retailer is very clearly incentivized to subsidize sales29 of its devices.

Uneven playing field: tax

We can’t talk about Amazon’s competitive advantages without mentioning tax. Over the past 15 years (2002–17), Walmart paid $103 billion in corporate income tax. That is 44 times the amount Amazon paid during the same period.30

Amazon is now the third-largest retailer in the world, in revenue terms, and, in 2018, became the second company in the US (following Apple) to hit $1trillion in market value.31

But companies don’t pay tax on revenues – they pay tax on profits. Amazon’s unconventional profit-sacrificing strategy has allowed them to minimize, sometimes even eliminate, their tax burden. In 2017, they reported $5.6 billion in profits but paid zero in federal taxes, the result of various tax credits and tax breaks for executive stock options.32

As an online retailer, Amazon has historically – and controversially – benefited from a 1992 Supreme Court ruling – Quill Corp. vs North Dakota – that prevented states from collecting sales tax from e-commerce companies unless those retailers have a physical presence in that state (in the form of an office or warehouse, for example). This is one of the reasons why Bezos was initially attracted to Washington as Amazon’s headquarters: the state had a small population and its capital Seattle was becoming a technology hub. It’s worth pointing out here that Bezos’ first choice is said to have been a Native American reservation near San Francisco, which would have presented generous tax breaks had the state not intervened.

Amazon spent its early days building warehouses in small states like Nevada and Kansas, allowing them to deliver to nearby populous states like California and Texas, but without collecting sales taxes.33 For years, the ability to sell stuff tax-free gave Amazon and other online retailers a gargantuan edge over bricks and mortar rivals. However, as Amazon continued to expand and its focus shifted to ever faster delivery, it had little choice but to open more fulfilment centres in closer proximity to its customers. ‘When that strategy no longer became tenable, and as Amazon wanted to add more warehouses in more states to support its growing Prime two-day delivery program, the company often negotiated to get the taxes delayed, deferred, or reduced as a condition of collecting them’,34 Jeremy Bowman of the Motley Fool wrote in 2018.

Many states subsequently signed on to an agreement that allowed retailers to voluntarily collect sales tax. By 2017, Amazon was collecting sales tax from all 45 states that have a state-wide sales tax,35 which meant that by the following year, when the Supreme Court finally overturned the 1992 ruling, the impact on Amazon was fairly minimal. It did, however, mean that Amazon’s third-party merchants had to begin charging sales tax on their products (Amazon had previously only collected tax on the items it owned).36