If thoughts are a cycle, then it follows that we have thoughts one at a time. More specifically, we can only focus on, and attempt to impose meaning on, just one set of information at a time. But the brain does many things at once. Most of us can, as the saying goes, walk and chew gum at the same time; and also walk, chew gum and be shocked by an overheard conversation. But if our mind is locked onto the conversation, it will not simultaneously be locked onto the walking or the gum-chewing: these activities, like the control of our breathing and our heart-rate, will, in a very real sense, be mindless. These processes are precisely those that do not involve interpretation (i.e. our best attempt to imaginatively apply anything and everything that we know in order to make sense of the information that is currently in our mental ‘focus’). Such mindless, automatic processes turn out to be very limited, both in what they can do and how well they can perform (though with the occasional surprising exception, as we’ll see later).

Yet if the mind is able only to lock onto one set of information at a time, does this mean that we are effectively oblivious to anything we are not currently paying attention to? Not quite. First, automatic processes such as gum-chewing and walking can continue uninterrupted, and these require the processing of some sensory information – about the terrain in front of us, our posture, limb positions and muscle activity to make sure that we don’t topple over, or sensory information about the inner world of our own mouths, if we are not inadvertently to bite our own tongues. Secondly, there is the question of vigilance, even for information we are not currently attending to. Remember that the periphery of the retina is continually monitoring the signs of motion, flashes of light, or other abrupt changes; our auditory system is alert, to some degree at least, to unexpected bangs, creaks or voices; our bodies are ‘wired’ to detect unexpected pains or prods. In short, our perceptual system is continually ready to raise the alarm – and to drag our limited attentional resources away from their current task in order to lock onto a surprising new stimulus. But these ‘alarm systems’ don’t themselves involve the interpretation and organization of sensory input; instead they help direct our attempts to organize and interpret sensory input. So we do not know what it is that has attracted our attention until we have locked onto the unexpected information and attempted to make sense of it.1

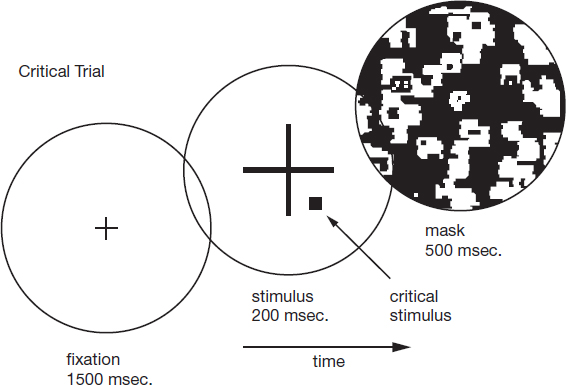

This means that we are sometimes oblivious to information to which we are not attending, even though it may be in plain view. Such ‘inattentional blindness’ seems highly counter-intuitive, but turns out to be all too real. The perceptual psychologists Arien Mack and Irvin Rock asked the participants in their experiments to fixate on a small cross in the centre of a computer screen. Then, a much larger cross appeared on the screen – and the task was to judge whether the horizontal or vertical arm of the large cross was longer. As can be seen in Figure 30, this is a fairly subtle discrimination, requiring careful attention. The large cross disappeared after one fifth of a second, before being replaced by a random black-and-white ‘mask’ pattern (on the right in Figure 30). Previous studies have shown that the mask will obliterate further visual analysis of the cross. The mask was just used to control the amount of time that people could look at the cross. If no mask was used, and the screen simply went blank, the participants would still potentially have access to an after-image of the cross on their retinas.

The viewer initially fixates on a small central cross; then comes the ‘critical stimulus’, with its large central cross. The viewer’s task is to report whether the vertical or horizontal ‘arm’ of the cross is the longer. After one fifth of a second, the critical stimulus is obliterated by a ‘mask’.

The key moment in Mack and Rock’s experiment came on the third or fourth trial, when they introduced an additional object, for example a black or coloured blob a couple of degrees away from the point of fixation (and hence projected near to, although not actually within, the fovea). In this crucial trial, Mack and Rock simply asked their participants whether they had seen anything other than the large cross.

Figure 30. Three successive stimuli in Mack and Rock’s experiment.2

Rather remarkably, about 25 per cent of people reported seeing absolutely nothing: even though the blob was fairly large, had strong contrast and was positioned as close to the fovea as the ends of the two lines that are being compared. This flagrant ‘inattentional blindness’ suggests that if people were not attending to the blob they simply didn’t see it.

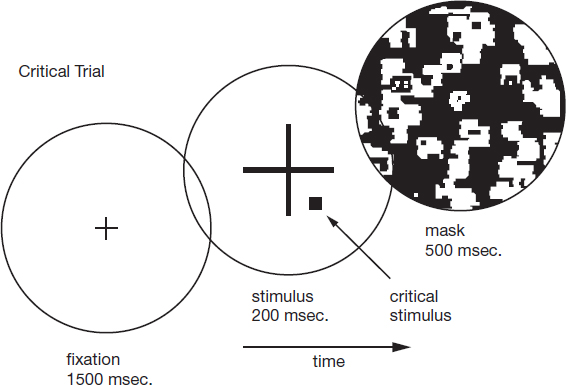

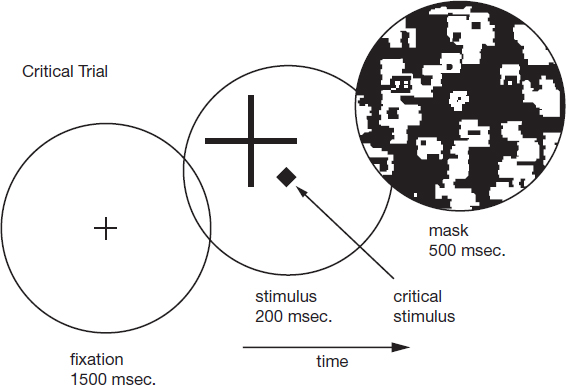

One might suspect that the blob’s slight offset from the fovea, where our visual processing is most acute, is part of the problem. If so, then there is a simple remedy: to move the large cross away from the fixation point (where the fovea is centred) and to put the blob on the fixation point – so that the participant is looking directly at the blob where their eye has the greatest possible acuity (see Figure 31). Yet incredibly, when this was done, Mack and Rock found that the rate of inattentional blindness rose, from 25 per cent to 85 per cent!

Is the strange phenomenon of inattentional blindness particular to vision? One way to find out is to replace the unexpected black blob with an unexpected sound.3 Participants carried out the visual task wearing headphones which played a continuous hissing white-noise sound – in the crucial trial, precisely at the point at which the cross-shape appeared, there was an additional, extended ‘beep’. Without any additional task, the beep was loud enough to be clearly audible – but, when people were focusing on which arm of the cross was longer, nearly 80 per cent of them denied that they had heard any such beep or, indeed, anything else unusual. So focusing on a tricky visual judgement can lead not only to inattentional blindness (even for a stimulus we are looking at directly), but also to inattentional deafness.5

Figure 31. A key variation. As before, the viewer initially fixates on a small central cross; then comes the ‘critical stimulus’, this time with a central blob and the large peripheral cross. As before, the viewer’s task is to report whether the vertical or horizontal ‘arm’ of the cross is the longer, and after one fifth of a second the critical stimulus is obliterated by the mask. Now the rate of inattentional blindness to the blob increases dramatically, even though the participant is now looking right at it.4

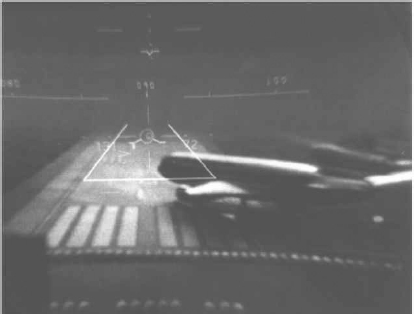

Inattentional blindness is by no means a mere curiosity. Indeed, it can be incredibly dangerous. NASA researcher Richard Haines used a realistic flight simulator to explore how pilots with many thousands of hours of flying experience were able to handle the information on the heads-up display – a transparent display on which information was presented, overlaid across the visual scene. The virtue of the heads-up display is that the pilots should, in principle, be able to take in the visual scene and read off crucial instrumentation while scarcely moving their eyes. By contrast, of course, conventional dials, screens and meters require a potentially disruptive and time-consuming shift in gaze.

Haines set the simulator so that the pilots had to land their ‘virtual plane’ at night in conditions of low visibility and hence rely almost exclusively on their instrumentation. Late in their descent, though, the plane suddenly broke through the bottom of the cloud cover, revealing a clear night-time runway scene, as shown in Figure 32. In the context of landing a plane, Figure 32 shows a mildly terrifying prospect: another plane is turning to taxi on the runway directly ahead. The majority of the pilots took rapid and drastic evasive action. A minority, though, did not – they continued their descent and landing entirely oblivious to the presence of a large, distinct, though thankfully virtual, passenger jet right in the centre of the visual field. Just like the experimental participants looking closely at the cross and missing the blob, these pilots were paying close attention to their heads-up display: attending, integrating and using this information to guide their actions. But by locking onto the heads-up display information, they were inadvertently tuning out safety-critical scene information, even though they were looking directly at it – and this was on a task with which they had hundreds of hours of practice.

Figure 32. Inattentional blindness in action. Focusing their attention on the symbols and lines of the heads-up display (shown), a significant minority of pilots were oblivious to the rest of the image and continued with a normal landing.6

The phenomenon of inattentional blindness is, in fact, familiar to all of us. Look out of the window from a brightly lit room at night. Notice how you can look at the world outside, seeing nothing of the reflections of the room; or you can examine the reflections, and find the world outside temporarily disappearing from view. Sometimes, of course, your visual system can struggle to determine which parts of the image are outside, which parts a reflection: for example, seeing a reflected light from the room as hanging in the sky (perhaps one potential source of UFO ‘sightings’). And it can create strange hybrids from bits of the exterior and interior of your home or office. But what the visual system cannot do is simultaneously ‘see’ two separate scenes at once: we can lock onto and impose meaning on (parts of) the reflected world, or the exterior world, or even a strange amalgam of the two, but we cannot do both at once. The pilots operate with the same limitations: attending to ‘display-world’ can entirely eliminate the external visual scene.

This is not necessarily disastrous news for heads-up displays, though. To the extent that the heads-up display augments, and meshes with, the external world, then the two may potentially be integrated together into a single meaningful whole, like a photograph adorned with highlights, arrows and other annotations. But if the display and external world are disconnected, rather than richly interconnected, then there is a real danger that seeing one will obliterate the other.

Consider now a path-breaking study led by one of the pioneers of cognitive psychology, Cornell University’s Ulric Neisser, participants watched videos of three people throwing a ball to one another.7 They had to press a button each time a throw occurred. But matters were not quite this simple: Neisser and his colleagues had created two different videos of the ball-passing game, and overlaid them. So now there were two teams of people (distinguished by having two different coloured shirts), and hence two types of ball-passing, one of which was to be monitored with the button pressing, the other of which was to be ignored.

Neisser’s first intriguing finding was that, from the start, people found this apparently substantial complication of the task no problem at all – they were easily able to lock their attention onto one stream of video and ignore the other. The brain was able to monitor one video almost as if the other superimposed video was not there at all. By contrast, for current computer vision systems, ‘unscrambling’ the scenes, and attending to one and ignoring the other, would be enormously challenging.

But Neisser’s second finding was the real surprise. He added a highly salient, and unexpected, event during the course of the video: a woman carrying a large umbrella strolled into view among the players, walked right across the scene, before disappearing from view. To a casual viewer of the video (i.e. to someone not counting the passes of one team or the other), the woman and her umbrella were all too obvious – indeed, her sudden appearance jumped out as both striking and bizarre. But less than one quarter of the people monitoring the ball-passes noticed anything untoward at all, even though, in following the passes, their eyes were criss-crossing the screen, passing and landing close to the large and, one would imagine, highly salient figure of the woman and her umbrella.8

What all these studies reveal is that our brains lock onto fragments of sensory information, and work to impose meaning on those fragments. But we can only lock onto and impose meaning on one set of fragments at a time. If our brains are busy organizing the lines on a heads-up display, we may miss the large aircraft turning onto the runway in front of us, in the same way that, peering through a lighted window into the garden, we can be utterly oblivious of our own reflection.

There is, according to the cycle of thought view, only one way information can enter into consciousness: through being directly attended to. But is there also a ‘back door’ to the mind, bypassing the cycle of thought, and hence conscious awareness, entirely?9 To my knowledge there is no experimental evidence for the existence of any such back door. Rather than being simultaneously able to piece together a number of distinct perceptual jigsaws, the brain is able to process only one jigsaw time.10

A single step in the cycle of thought operates, then, along the following lines. Early in each processing step, there may be some uncertainty about which information is to be locked onto and which should be ignored. The brain will initially find some basic ‘meaning’ to help pin down which information is relevant and which is not. That is, where our perceptual jigsaws have been mixed together, we need initially to look at, and analyse, pieces of both jigsaws before we can pin down which pieces are relevant to us, and which should be ignored. But as the brain’s processing step proceeds, the effort of interpretation will narrow ever more precisely on the scraps of information that helped form whatever pattern is of interest, and the processing of other scraps of information will be reduced and, indeed, abandoned. By the end of the processing step, the interpretative effort has a single outcome: the brain has locked onto, and imposed meaning upon, one set of information only. In terms of our jigsaw analogy, each step in the cycle of thought solves a jigsaw and only one jigsaw. We may, if reading text, or flicking our eyes across an image, or being subjected to a rapidly changing stream of sounds or pictures, solve several ‘jigsaws’ a second (though frequently there are hints from one jigsaw that help us solve the next – e. g. when we are scanning a scene, or reading a book, we build up expectations about what we’re likely to see, or read, next; if our expectations are confirmed, then solving the next mental jigsaw will be more rapid). But our brain is still subject to a fundamental limitation: analysing one set of information at a time. And, as we have seen, the meaning that we impose in each step in our cycle of thought corresponds with the contents of our stream of conscious awareness. So the sequential nature of consciousness is no accident: it reflects the sequential engine that is the cycle of thought.

So what is the evidence for this view of conscious experience? In particular, how do we know that the brain attempts to make sense of just one set of information at a time?11 Looking back, all the evidence we have examined for the grand illusion gives us a strong hint. We have the impression that we see pages of words, roomfuls of people, scenes full of objects rich in colour and detail – and we saw that this impression is entirely mistaken. Recall, for instance, as we discussed in Chapter 1, that when subjected to the trickery of the gaze-contingent eye-tracker, people can read fluently and normally, while entirely oblivious of the fact that, at each fixation, just twelve to fifteen letters are presented onscreen, and the rest of the text has been replaced by xs or by Latin.

If the brain was ‘secretly’ processing all, or some, of those other ‘words’, even if unconsciously, one might imagine that there would be some, and perhaps a rather dramatic, effect on reading. To my knowledge, no such effects have been reported.12

Figure 33. Visual displays in Rees et al.’s experiment.

In the grip of the grand illusion, we imagine that we simultaneously perceive great seas of words, faces and objects, all in high definition and full colour; and that we can ‘take in’ a rich soundscape of voices, music and clinking of glasses in a single perceptual gulp. The grand illusion tricks us into believing that our focus of attention is far wider than it actually is.

So we can attend to much less than we imagine; and unattended information can change dramatically (from xxxs to text to xxxs again) without our noticing. So it seems both that our attention is severely restricted, and that we have little or no access to information that is not attended to. Yet could it be that unattended information is processed elaborately, but is rapidly forgotten? Could it be that some of the apparent richness of subjective experience is real enough – but that the reason we can never reveal such experience in experiments is because the memory of all those unattended objects, colours and textures is so fragile?

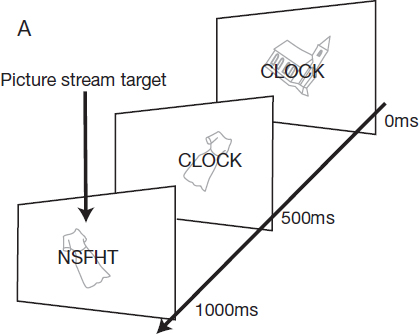

Geraint Rees, Charlotte Russell, Chris Frith and the late Jon Driver, working at one of the world’s leading brain imaging labs at University College London, found a beautifully elegant way to look at this question, by monitoring the online activity of the brain (see Figure 33).13 People were settled into a brain scanner and shown images involving a line drawing of a familiar object, overlaid by strings of letters in block capitals. These strings of letters were meaningless in some blocks of trials, but formed familiar words in others. Prior research has established that there is a characteristic frisson of brain activity associated with reading a word in contrast merely to a meaningless string of letters. So we can use this burst of activity (as it happens, towards the back left of the brain, in the left occipital cortex) as a tell-tale objective indicator that a word has been recognized – and this indicator is, of course, completely independent of subjective awareness.

Rees and colleagues showed people streams of stimuli consisting of letter strings (which might be meaningless or might form familiar words) and pictures overlaid (see Figure 33). People’s attention was directed to the word or the picture by giving them a simple task, which involved looking at just one of type of information: specifically, people were asked to monitor for immediate repetitions (i.e. pairs of successive identical stimuli) either for words, or for pictures. They could tell that people were paying attention to one type of information (letters or pictures) by checking that they successfully picked out the repetitions when they occurred. The images were presented sufficiently rapidly that people were able to report repetitions accurately only by locking their attention purely onto one type of stimulus or the other – there was no time for their attention to ‘hop’ back and forth between the letters and pictures.

When answering questions about, and hence attending to, the letter strings, the distinctive word-specific frisson of activity was present when the letter strings made familiar words – but the presence of the unattended pictures did not change the results. So far, so good. But what happened when people monitored, and hence paid attention to, the pictures? If the brain was still recognizing the unattended words as normal (i.e. if unattended information is analysed, but then ignored), then the tell-tale word-specific frisson should still be present. If, on the other hand, the brain failed to distinguish between arbitrary letter strings and words – because unattended words aren’t read at all – then the distinctive, word-specific pulse of neural activity should be absent. And, indeed, the latter possibility turned out to be correct.

The results showed that the participants were simply not reading the unattended words at all, even though they were looking directly at them. And they were not reading the words because, crucially, they were paying attention to something else: the overlaid pictures. So, roughly speaking, if you don’t pay attention to a word, you just don’t read it. Indeed, from the brain’s point of view, it isn’t there. It seems reasonable to conjecture that the same is true wherever the cycle of thought operates, not just in reading: without attention, there is no interpretation, analysis or understanding.14

I have argued that the cooperative style of brain computation is what forces us to think one step at a time. But this viewpoint has a further implication: those distinct, non-interacting networks of neurons should, in principle, be able to work independently, with each network cooperatively solving its own problem, without interference. As it happens, the brain is densely interconnected – and almost any moderately complex problem, from understanding a sentence to recognizing a face or seeing a constellation in the night sky, will typically involve activity across large swathes of the cortex. So our ability to carry out several mental activities ‘in parallel’ will be severely limited.

There are, though, tasks for which our neural ‘machinery’ is, conveniently, largely separate. One clear-cut example is the operation of the ‘autonomic’ nervous system, which runs our heart, breathing, digestion, and so on. These neural circuits are only loosely coupled with the cortex – so that, thankfully, our heart can keep beating, our lungs breathing, and our stomachs digesting, even while we focus our attention on a tricky problem or a good book. But what about more complex tasks? Perhaps if the tasks are sufficiently different, they might not use overlapping networks in the brain – and if so, perhaps they could operate independently and hence simultaneously.

This situation is rare, but it can occur. A remarkable study15 by the Oxford psychologist Alan Allport and colleagues looked at this question, asking pianists who were skilled sight-readers to combine sight-reading a new piece of music with ‘shadowing’ speech delivered through headphones (repeating the flow of speech that one is hearing, often with as little as one quarter of a second delay). Amazingly, after a fairly modest amount of practice, there was very little interference between the two tasks: people could shadow and sight-read fluently at the same time.

Shortly afterwards, a follow-up experiment by Henry Shaffer at the University of Exeter pushed this result a step further, showing that highly trained typists were able to shadow and type unseen texts with almost no interference.16 This seems particularly remarkable, as both the shadowing task and the typing task involved language – so one might imagine they would be especially likely to become entangled. But surprisingly, the typists appeared to carry out both tasks at close to normal speed and accuracy.

So it seems that the networks of neurons involved in carrying out the two tasks are indeed separate, or at least can be kept separate with practice. So, for example, perhaps a mapping from visually presented letters or words to finger movements (required for typing) can be kept distinct from a mapping between auditory words and speech (required for shadowing). If this is right, then at most one of the streams of language flowing through the participant as they simultaneously touch-type and shadow speech in Shaffer’s experiment can be processed for grammar and meaning. Indeed, this would imply that the participant can fluently touch-type and shadow speech where the linguistic material being communicated is nonsense rather than meaningful. The conscious, meaningful interpretation of language would, accordingly, apply to either the material that is being read or heard, but not to both (so that, for example, the meaning of just one stream of input would be encoded and stored in memory). It should not be possible to make sense of both linguistic inputs simultaneously any more than it should be possible to see each of two visual patterns, one superimposed upon the other or, for that matter, to see an ambiguous item as both a rabbit and a bird (see Figure 24). This line of reasoning leads logically to the prediction that people should be able to recall at most one of the linguistic inputs they were working with – only one of which can have been processed for meaning.

If this general theory is correct, the brain can carry out multiple tasks if each of those tasks draws on non-overlapping networks of neurons. But given the dense connectivity of the brain, and the multiplicity of elements involved in carrying out many tasks, this is rarely possible for tasks of substantial complexity. Usually there is some overlap in the neural networks each task recruits, which will snarl up our ability to do both tasks simultaneously. It may be that the neurons involved in walking and chewing gum are relatively distinct from each other, and from, say, doing complicated pieces of mental arithmetic (although when we need to concentrate really hard on a tricky multiplication or a crossword clue, we may find ourselves, perhaps tellingly, slowing or stopping walking, pausing our gum-chewing, and perhaps even closing our eyes).

Almost any demanding pair of tasks, then, will involve over-lapping neural circuits – so that perception, memory and imagination can only proceed one step at a time. Each step may be a ‘giant’ step, making sense of a complex visual image or a rich musical pattern, or solving a crossword clue – and will draw on the cooperative efforts of networks containing billions of neurons; but the inner workings of each step are, of course, utterly inaccessible to conscious awareness.

In this chapter, we have seen how, special cases aside, the cycle of thought provides a single channel through which we make sense of the world, step-by-step; and if the cycle of thought is locked onto one aspect of the visual world, other information (blobs, aircraft, words) can be ignored, even when in plain sight. If this is right, then the sequential nature of the cycle of thought seems to imply that conscious thought on one topic blocks out thought (whether conscious or unconscious) on any other topic (assuming, as will typically be the case, that these streams of thought would depend on overlapping brain networks). The slogan we have already encountered in Chapter 7 remains true: ‘no background processing in the brain.’

The existence of unconscious thought can therefore be considered a crucial test case for our entire account. Does it stand in opposition to the cycle of thought account? Or is it just one more mirage that disappears on closer inspection?