Convoys, Cruisers and ‘Station Ships’

THE ORIGINAL MEANINGS of the words‘convoy’and‘cruiser’ were lost in later years, when they came to be applied in rather different ways. In the seventeenth century the ‘convoy’ was the warship (or warships) escorting merchantmen, not the merchantmen themselves; a ‘cruiser’ was literally a warship that cruised in a certain sea area, so it could be of any rate or size. Of the two, the cruiser had the longer history. Deploying warships to protect the trade passing into or out of busy‘choke points’ and sea areas was a long-established principle. It was reflected in the names given to the groups of ships fitted out for service each year, the ‘summer guard’ and ‘winter guard’, a nomenclature that dated back well into Tudor times. Charles I had built a class of smaller warships, the ‘Lions’ Whelps’, to cruise in home waters for the defence of trade. Many merchants, particularly Londoners involved in the rich trades with the Mediterranean and the Baltic, believed that these measures were insufficient to protect their interests, and from the 1640s onwards they were increasingly strongly represented in Parliament and the naval administration.* In 1650 the Commonwealth responded to these concerns by instituting the first system of Mediterranean convoys.1 From then on, particularly important trades had warships specifically allocated to their defence. The system was eventually put on a statutory footing in 1694, when the depredations of French privateers, and concerns that the navy had too few warships of the Fourth Rate and below that could undertake trade protection, led to the passing of a ‘Convoys and Cruisers Act’. Guardships and guardboats also became established parts of the navy during this period, as did ‘station ships, though that term is anachronistic as they were not known as such until many years afterwards.

Ludolf Backhuysen’s drawing of a yacht and warships off Plymouth in 1679, with Mount Edgecumbe in the centre and Cawsand Bay to the left.

(© TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM)

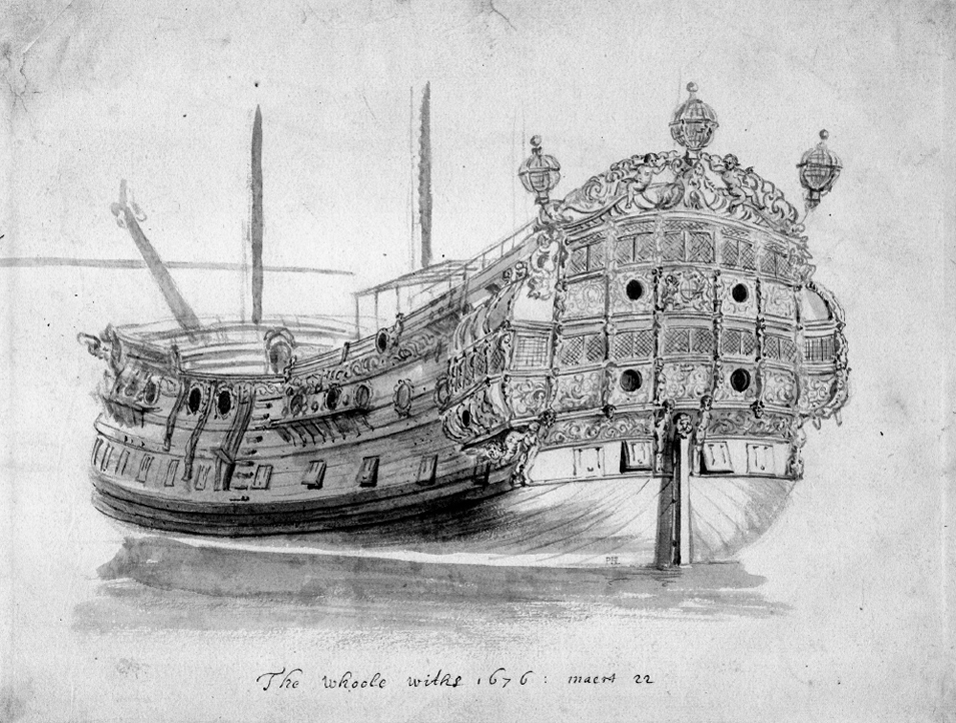

The fourth rate Woolwich, launched at her namesake dockyard in 1675, was often employed on convoy duty during the 1670s and 1680s, particularly in the Mediterranean.

(© TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM)

DEPLOYMENT

Naturally, the precise deployment of ships to certain trades or sea areas varied over the years as priorities changed, new trade routes became favoured, or old trades declined. The old distinction between ‘summer and winter guards’ became increasingly difficult to keep up as the navy’s commitments became more diverse and ships needed to be deployed more flexibly; it fell increasingly into disuse from the mid-1670s onwards.2 Nevertheless, certain principles governing the deployment of warships became established. At least one ship (usually a Fourth or Fifth rate) was stationed permanently in the Downs, and from 1674 the senior captain there was entitled to fly a broad pennant to identify himself.3 Other ships were always to the westward, in the Soundings and the mouth of the Channel, to protect incoming trade, and by the 1670s these had become a properly constituted ‘Western Squadron’ with its own base at Plymouth.4 Ships were deployed to cruise in the Channel, to guard the collier route along the east coast of England, and to defend the Iceland and Yarmouth fisheries. The Newfoundland convoy both protected the fishermen from attack as they plied their trade on the Banks, and then escorted them to the Mediterranean to sell their catches. A small number of ships were always allocated to Ireland, and individual vessels were stationed in the West Indies. Convoys were allocated to particularly lucrative overseas trade, notably those to and from the Levant and Baltic. From the early 1670s onwards, these were also given to the incoming merchant fleets from Virginia and Barbados, whose safe arrival was almost as important an economic and psychological bellwether for Britain as that of the East Indies fleet was for the Dutch or the plate fleet for the Spanish.5 In wartime, convoys would be allocated to coastal trades, especially to the Newcastle collier fleets, which were often vast affairs consisting of 200 ships or more. In April 1665, for example, seven Fifth and Sixth rates, along with four hired ships of twenty to thirty guns, were allocated to convoy duty in the Channel, and another four ships were intended for the colliers on the east coast.6

Many disposition lists survive for the period, and these provide valuable ‘snapshots’ of what the navy’s ships were doing at particular times. Chance survivals of individual lists from the 1650s and 1660s suggest that these were kept on a monthly basis throughout the period, but a complete run of monthly disposition lists survives only from the latter stages of the third Dutch war; they were then maintained religiously by the Admiralty until well into the nineteenth century.7 On 1 July 1673, the first date to be recorded in the surviving run, one Fourth Rate and one Sixth were cruising in the Soundings, three Fifths were cruising off the Firth of Forth, off Cape Clear and between Dublin and Bristol, while three Sixths were off King’s Lynn, the Suffolk Coast and the Isle of Wight and between Yarmouth and Tynemouth. Convoys to Dublin and from Portsmouth were being provided by Fourth Rates, while Fifths were convoying to Milford and Morlaix, and three Sixths or smaller to Hull and Whitby. By the following January the squadron in the Soundings had been expanded to three Fourth Rates (and a Third had served in it during the autumn, when particularly important merchant fleets were due). Four ships, included three Fourth Rates, were guarding the Newcastle colliers, reflecting the greater importance of that trade in the depths of winter. A Sixth Rate was convoying Welsh colliers, and two frigates were escorting trade from Morlaix. One Fifth Rate was in Ireland, and doggers were cruising off the North Foreland, the North Norfolk coast and the mouth of the Humber. No vessels were now required for the fisheries, as their former escorts had been ordered back to port in November when the season finished.8 Although there were certain immutable commitments, such as the deployments in the Soundings and on the east coast, ships were also deployed in response to short-term developments. In the summer of 1677 two ships were kept off Ostend to restrict the activities of the town’s privateers, ‘the principal (if not only) disturbers’ of the peace at that time, while two others were to be sent to the Hastings fishery to ward off French interlopers.9

CRUISERS

In peacetime, small squadrons were kept in the Channel and the Soundings, with the latter’s cruising ground being defined as 49° 30′ latitude, forty or fifty leagues west of the Lizard. These acted as a deterrent, particularly to Dunkirk or Barbary corsairs, but could also escort outgoing and incoming merchantmen. Individual ships were regularly detached to convoy ships down to Spain, Portugal, the Canaries or Madeira.10 Deploying cruisers in the Channel and Soundings in this way, and sending them off on convoy duty as and when necessary, continued during wartime. The activities of the Mary Rose in 1672–3 were typical for a large cruiser on war service in home waters. In December 1672 and January 1673 she was cruising between Dungeness and Cap de la Hogue, as ordered. This was an endless round of stopping ships to check their identities, interspersed with a couple of unsuccessful pursuits of actual or suspected Dutch privateers. From February to April she convoyed the Canary fleet. Off the Lizard on her return voyage, she encountered the Western Squadron, consisting of the Third Rate Dunkirk, the Fourth Newcastle and the Fifths Nightingale and Success. The Dunkirk was then detached to convoy a merchant fleet to the Downs, while the Mary Rose herself went off to join the main fleet, taking part in all the battles of the 1673 campaign.11

CONVOYS

Two convoys in particular, those that served the Levant trade and the Newfoundland fishery, were at the heart of the navy’s peacetime deployments. By the 1670s the former followed a well-established pattern. The warship and her charges called at most, and usually all, of Cadiz, Tangier, Malaga, Alicante, Genoa, Leghorn, Naples, Messina, Gallipoli, Zante, Constantinople, Smyrna and Scanderoon before turning round and repeating the voyage in reverse. At each port, some merchantmen would be left behind and others would join, a method that has been described neatly as ‘an elaborate bussing service’.12 Thus in 1680 the Leopard and Foresight had eighteen sail under their escort when they left the Downs, but by the time they passed Cape Passaro only five Levant Company ships were left, three of which went into Smyrna with one of the escorts while the other two went on to Constantinople with the other warship. They sailed on the return leg with five vessels, but by the time they left Cadiz three months later they were escorting twenty-eight.13 Meanwhile, the Newfoundland convoy went out to the fishing grounds in the summer, and escorted the laden ships to the Mediterranean by the onset of autumn, to provide Catholic Europe with its fish for the winter. These convoys, which could be huge affairs of sixty or seventy ships, went to the same ports in the western Mediterranean as the Levant convoys, although they went no further east than Leghorn.14 Ships were also sometimes assigned to the Italian and Canary trades, and to the herring and Iceland fisheries.15

During wartime, overseas trade and its escorting convoys largely ceased in the spring and resumed again in the autumn. This was due both to the perceived threat to trade from enemy action and to the need to prioritise the manning of the fleet. In March 1672 the Ruby, Antelope and Fanfan were ordered to ply off Heligoland to await the Hamburg ships and then bring them home before the third Anglo-Dutch war got properly under way. Foreign trade then largely ceased until November, when the Newcastle and Richmond were ordered to Bilbao to convoy home the many merchant ships waiting there, while the Hampshire was ordered to convoy the trade to Nantes, La Rochelle and Bordeaux.16 In home waters during wartime, formal orders to ships to convoy from A to B were supplemented by ad hoc arrangements, made in response to circumstances. In 1653 Captain David Dove of the Tenth Whelp had just brought a merchant convoy from Spurn Head to Orford Ness when he was ordered by a senior officer to return north to ply between Yarmouth and Newcastle, ‘to convoy as opportunity shall present’.17 In the summer of 1673 the convoy of an important cargo of tin to Havre de Grace was entrusted to the first warship that happened to sail eastwards past Portsmouth, while the Holmes was sent to the Firth of Forth to protect trade there and was placed under the operational orders of the Earl of Rothes, Chancellor of Scotland. The Fourth Rate Dartmouth, along with the Well and Dove doggers, were to escort coasters to Hull, Tynemouth and Leith, then returning to Tynemouth to pick up the colliers for the Thames.18 The fisheries were given strong protection. In September 1673 a small squadron of five ships, led by the Fourth Rate Phoenix, was sent out to protect the herring fishery during the entire fishing season, with one of them escorting the fishing boats back to their home ports at the end of the season.19 The Garland went to the Americas in 1673. After escorting fifteen merchantmen bound from Barbados to England as far as 17° (latitude), she returned to cruise among the Leeward Islands, then escorted forty-five ships to Boston. After convoying the return fleet, she resumed her cruising duties before returning to England in the summer of 1674, convoying home seven lucrative cargoes from Barbados.20

No matter how effective a system of convoys the government put in place, it depended entirely on the willingness of the owners and masters of merchant ships to make use of them. Individual merchants often requested convoys for valuable cargoes being shipped on their accounts, and some occasionally put forward elaborate suggestions for convoy timetables that seemed to pay little regard to the vagaries of wind and tide.21 But other merchants were often unwilling to wait for a warship to come to them, and equally unwilling to sail in company with perhaps dozens of other ships. Many were willing to run the risk of capture in order to get their cargoes more quickly to their destinations (and their profits), and throughout the period naval officers and administrators had to deal with recalcitrant civilians who were unwilling to ‘comply by staying for convoy and keeping with it when given’.22 The same was true of their willingness to stay in formation. In 1670 one convoy commander organised his seven charges by placing them in two parallel lines of three ships, half a cable’s length apart, with his warship leading them (rather than sailing to windward of them, which was the norm) and the strongest merchantman at the rear, but this sort of system was often wishful thinking.23

‘STATION SHIPS’

Deploying ships to defend a particular geographical or political entity and its trade became a necessity by the middle of the seventeenth century. The acquisition of colonies in the Americas, such as Virginia (1624), Barbados (1625) and Jamaica (1655), was usually undertaken in the teeth of Spanish or other opposition, and the Royalist success in using the early colonies as bases long after their cause had been defeated in Britain emphasised their vulnerability. After the Restoration it became common to have a ship at Jamaica (from 1667), at Barbados (from 1677) and in the Leeward Islands (also from 1677); at least one frigate was normally based at Jamaica, and this provision was extended to the Leewards in the 1680s as an anti-piracy measure.24 Ketches were stationed in Virginia from 1684 (although a frigate had been ordered to Chesapeake Bay in 1667 to guard the trade of those waters25), and New York had a warship from 1691. These tended to spend longer on station than the ships in the Caribbean, where the region’s notorious problems of disease, lack of supplies and the teredo worm all took their toll. In peacetime the ships on these American stations were invariably Fifth Rates or smaller vessels, but in war larger ships were sent out.26 These postings tended to be unpopular, and the ships had difficulties in attracting good officers and sufficient numbers of men. Several captains were undoubtedly incompetent; the captain of the Quaker Ketch, based in the Leewards in 1679, was said to be ‘a mere brute unfit to live among men, daily quarrelling and as often baffled’.27 But even he was outmatched by John Crofts, captain of the Deptford Ketch in Virginia in the 1680s. Crofts had a long and relatively unblemished career as a lieutenant going back to the third Dutch war, but command and/or Virginia transformed him into an abusive drunk who argued incessantly with his equally erratic wife, who once threw blazing embers across the deck with no regard for the proximity of the powder magazine; Admiral Lord Dartmouth’s tongue was presumably not in his cheek in 1688 when he recommended Crofts for the command of a fireship.28 Additionally, warships were occasionally sent out to deal with interlopers on the African coast, who threatened to undermine the Royal African Company’s monopoly: these were the Phoenix in 1674, the Hunter in 1676, the Norwich in 1678 and the Mordaunt and Orange Tree in 1684. Although the Hunter was technically hired out to the company, this was actually academic, as the company’s shareholders were essentially synonymous with Charles II’s family and ministers.29

‘Station ships’ were also required closer to home. Several ships were based in Ireland, even in peacetime, but the station was often neglected. In 1665 several ships that had been sent there to intercept Dutch trade going ‘northabout’ were diverted into the Soundings instead, and even the Lord High Admiral himself admitted that the four small ships that were left were inadequate to protect Ireland.30 Plans to expand the Irish squadron had to be shelved because the ships were needed elsewhere.31 A similar problem occurred during the third war, when the navy struggled to spare three frigates for Ireland because of the need to set out the largest possible fleet, and subsequent proposals to create a dedicated ‘Irish navy’ of up to twenty-five ships proved to be pure fantasy.32 Even so, Ireland was better provided for than Scotland, which was served only by an occasional token deployment of one or two ships, such as that of the Holmes in 1673. Although Scots privateers made up the shortfall to some extent in wartime,* the coast and Scottish trade remained markedly vulnerable, and the country usually had no dedicated naval cover at all during peacetime, although occasional east-coast convoys went as far north as Leith. This situation changed rapidly after 1689, reflecting the new Jacobite threat. By the autumn of that year sixteen warships, including three Fourth Rates, were cruising off the west coast of Scotland, where they joined the two newly hired warships of the minuscule Scots navy.33

The Channel Islands were theoretically neutral territory that should not have required British naval protection, but this status was always highly debatable.34 It may be a sign of the true extent of King Charles II’s trust of his cousin Louis XIV that the regular stationing of warships in the islands began during the third Anglo-Dutch war, when Britain and France were officially allies. Admittedly, the ships involved were invariably very small, and the first was commissioned as a private initiative. The Hatton Ketch, stationed at Guernsey in 1672, was owned by the island’s governor, Lord Hatton, who had hired her out to the navy for exactly that purpose. The ketch was used to defend the island against Dutch capers and to convoy local trade to and from St Malo.35 During the 1670s and 1680s the islands were served by a succession of Sixth Rates and sloops, but when the French war began in 1689 the vessels based there were nothing more than yachts, the Charlotte at Guernsey and the Isabella at Jersey. They were gradually superseded by other ships, but these were often prizes or other lesser craft: purpose-built warships went to the main fleet or the main cruiser and convoy duties. In 1691–2 the Julian Prize, a 14-gun French Sixth Rate captured in 1690, was based at Guernsey. Her case indicates one of the major obstacles to a sustained naval presence in the Channel Islands, the lack of a sufficient infrastructure to support warships: the Julian, like other vessels before and after her, had to retire to Southampton for victualling and repair.36

Landport Gate, built by Bernard de Gomme as part of his improvements to the defences of Portsmouth in the late 1660s and 1670s.

(AUTHOR’S PHOTOGRAPH)

GUARDSHIPS

The idea of stationing guardships to defend dockyards predated the Dutch attack on the Medway in 1667, but at first it was not applied with much planning or consistency. In 1659–60, just before and after the Restoration, the ‘guard of the Medway’ was provided by two 16-gun ships which had been placed there to prevent shallops running upstream to fire the dockyard.37 These were paid off in 1663 to save money, and a guard was maintained aboard the Sovereign instead.38 By 1673, though, the Medway was again being protected only by a Sixth Rate and a prize ship; throughout this period Portsmouth had no guardship at all, but by 1674 it had the Wivenhoe.39 Guardships were kept rigged and armed for the purpose, and their crews exercised regularly with small arms. They were meant to challenge any vessel that approached the ‘great ships’ in their harbours, especially at night.40 There were some unfortunate accidents; in 1675 a boat approaching the Portsmouth guardship late at night refused to give an account of itself, the guardship fired, and the carpenter of the Oxford – presumably returning to his ship after a bibulous ‘run ashore’ – was shot dead.41

The selection of guardships seems to have depended on what was available (naturally, much less in war than in peace) and on cost, with a reduction in guardship provision being an obvious economy measure for a cash-strapped ministry. The Second Rate French Ruby served as the guardship at Sheerness in 1673–4, but from 1678 to 1688 that role was filled by the Eagle Fireship; in 1678 the First Rate Royal James was employed as guardship at Portsmouth. The years after 1679 saw another period of retrenchment, which led to a reduction in the size of the crews carried and to the employment as guardships of a motley collection of three prizes and hired ships each at Portsmouth and Chatham.42 Thanks to the programme of naval reconstruction undertaken by Pepys and King James II, these were replaced in 1685 by two Thirds and two Fourths at each yard.43 Guardships had larger crews than the ships in ordinary, but considerably smaller ones than those at sea; the Algerine prize Golden Horse, one of the guardships at Chatham in 1685, had a crew of five officers (excluding the captain) and seventy-three men.44

Guardships provided employment for officers and men who would otherwise be forced out of immediate naval service, but they also formed part of a massive programme of enhanced defences for the dockyards and naval bases that followed the Dutch raid on the Medway in 1667, and which also witnessed the construction of the Royal Citadel at Plymouth and de Gomme’s defensive lines at Portsmouth. The new defences were complemented in 1675 by the introduction of a system of guardboats, supplementing the larger and less flexible guardships. There were initially ten at Portsmouth, with one dedicated exclusively to the Royal Charles and another to the Royal James. Each boat was numbered and carried a crew of about a dozen, who would be summoned to their rendezvous by specially devised calls.45 By 1685 the guardboat establishment had expanded to twelve at Portsmouth and twenty at Chatham, each armed with six firelock muskets and six half-pikes. They were now manned from the guardships, rather than from the ordinary as before, and one was selected at random as the duty boat for any given evening. The duty boat was to hail every warship in the harbour, to look out for naked flames or signs of drunkenness aboard them, and to check the shores for enemy craft or (more likely) the boats of thieves and embezzlers.46

* See Part One, Chapter 3, p25.

* See Part Five, Chapter 20, p119-20.