Athens and Sparta had cooperated in the fight against Xerxes’ great invasion of Greece in 480–479 B.C., but by the middle of the fifth century B.C. relations between the two most powerful states of mainland Greece had deteriorated to such a point that open hostilities erupted. The peace they made in 446–465 to end these battles was supposed to endure for thirty years, but the conflicts between them in the 430s led once again to an insupportably high level of tension. The resulting Peloponnesian War lasted twenty-seven years, from 431 to 404, engulfing most of the Greek world at one time or another during its generation-long extent. Extraordinary in Greek history for its protracted length, the deaths and expenses of this bitter Greek-on-Greek conflict shattered the social and political harmony of Athens, sapped its economic strength, decimated its population, and turned its citizens’ everyday lives upside down. The war exposed sharp divisions among Athenian citizens over how to govern the city-state and whether to keep fighting as the bodies and the bills piled up higher than they could handle. Their homegrown disagreements were expressed most eloquently and bitingly in the comedies that Aristophanes (c. 455–385 B.C.) produced during the war years. There were other fifth-century comic authors whose plays also exposed the stresses of war at Athens, but Aristophanes is the only one for whom we have comic dramas whose texts have survived intact. Even after the active bloodshed of the war died out with Athens’s surrender in 403, the trial and execution of the philosopher Socrates in 399 revealed that the bitterness and recriminations dividing Athenians lived on.

433 B.C.: Athens and Corinth clash over former Corinthian ally.

432 B.C.: Athens imposes economic sanctions on Megara.

431 B.C.: War begins with first Spartan invasion of Attica and Athenian naval raids on the Peloponnese.

430–426 B.C.: Epidemic strikes Athens.

429 B.C.: Pericles dies in epidemic.

425 B.C.: Athenians commanded by Cleon capture Spartan hoplites at Pylos; Aristophanes’ comedy The Acharnians produced at Athens.

424 B.C.: Aristophanes’ comedy The Knights produced at Athens.

422 B.C.: Cleon and Brasidas killed in battle of Amphipolis.

421 B.C.: Peace of Nicias reestablishes prewar alliances.

418 B.C.: Athenians defeated at Mantinea; war with Sparta resumes.

416 B.C.: Athens attacks the island of Melos.

415 B.C.: Athenian expedition launched against Syracuse on the island of Sicily; Alcibiades defects to Sparta.

414 B.C.: Aristophanes’ comedy The Birds produced at Athens.

413 B.C.: Destruction of Athenian forces in Sicily; establishment of Spartan base at Decelea in Attica.

411 B.C.: Athenian democracy temporarily abolished; Aristophanes’ comedy Lysistrata produced at Athens.

410 B.C.: Alcibiades commands an Athenian naval victory over the Spartans at Cyzicus; democracy is restored at Athens.

404 B.C.: Athens surrenders to Spartan army commanded by the Spartan general Lysander.

404–403 B.C.: Reign of terror of the Thirty Tyrants at Athens.

403 B.C.: Overthrow of the Thirty Tyrants in civil war and restoration of Athenian democracy.

399 B.C.: Trial and execution of Socrates at Athens.

By 393 B.C.: Rebuilding of Long Walls of Athens completed.

The losses that Athens suffered in the Peloponnesian War show the sad, if unanticipated, consequences of the repeated unwillingness of the male voters in the city-state’s democratic assembly to negotiate peace terms with the enemy: By insisting on total victory they lost everything. The other side of the coin, so to speak, is the remarkable resilience that Athenians demonstrated in recovering from their wartime defeats and severe losses of manpower. The magnitude of the conflict and the unprecedented, if controversial, contemporary analysis of it provided by Thucydides justify the high level of attention that modern historians and political scientists have devoted to studying this conflict and its effects on the people who fought it.

Most of our knowledge of the causes and the events of this long and bloody war depends on the history written by the Athenian Thucydides (c. 460–400 B.C.). Thucydides served as an Athenian commander in northern Greece in the early years of the war. In 424 B.C., however, the assembly exiled him for twenty years as punishment for failing to protect a valuable northern outpost, Amphipolis, from defecting to the Spartan side. During his exile, Thucydides was able to interview witnesses from both sides of the conflict. Unlike Herodotus, Thucydides concentrated on contemporary history and presented his account of the events of the war in an annalistic framework—that is, according to the years of the war, with only occasional divergences from chronological order. Like Herodotus, however, he included versions of direct speeches in addition to the description of events. The speeches in Thucydides’ annals, usually longer and more complex than those in Herodotus’s, vividly describe and analyze major events and issues of the war in complex and dramatic language. Their contents usually present the motives of the participants in the war. Scholars disagree about the extent to which Thucydides has put words and ideas into the mouths of his speakers, but it seems indisputable that the speeches deal with the moral and political issues that Thucydides saw as central for understanding the Peloponnesian War as well as human conflict in general. Thucydides’ own comments offer broad, often-pessimistic interpretations of human nature and behavior. His perceptive chronicle of events and disturbing interpretation of human motivations made his book a pioneering work of history as the narrative of disturbing contemporary events and power politics.

The Peloponnesian War, like most wars, had a complex origin. Thucydides reveals that the immediate causes centered on disputes between Athens and Sparta in the 430s concerning whether they could each set their own independent courses in dealing with the city-states allied to the other. Violent disputes broke out concerning Athenian aid to Corcyra (an island naval power in conflict with Corinth, a principal Spartan ally), the economic sanctions imposed by Athens against the neighboring city-state of Megara (a Spartan ally located immediately west of Athenian territory), and the Athenian blockade of Potidaea (a strategically positioned city-state in northern Greece formerly allied to Athens but now in revolt and seeking help from Corinth). The deeper causes involved the antagonists’ ambitions for hegemony in Greece, fears of each other’s power, and determination to remain free from interference by a strong and hostile rival.

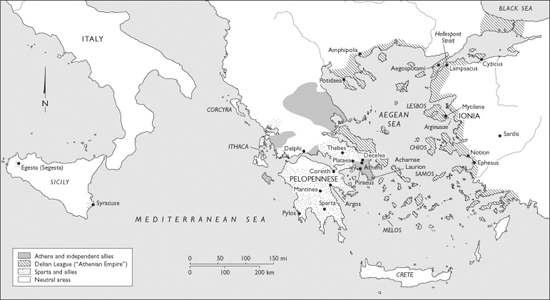

Map 6. The Peloponnesian War

The outbreak of the war came when the Spartans issued ultimatums to Athens that the Athenian assembly rejected at the urging of Pericles. The Spartans threatened open warfare unless Athens lifted its economic sanctions against Megara and stopped its military blockade of Potidaea. The Athenians had prohibited the Megarians from trading in all the harbors of the Athenian Empire, a severe blow for Megara, which depended on the revenue from seaborne trade. The Athenians had imposed the sanctions in retaliation for alleged Megarian encroachment on sacred land along the border between Megara and Athens. Potidaea retained ties to Corinth, the city that had originally founded it, and Corinth, a Spartan ally, had protested the Athenian blockade of its colony. The Corinthians were by this time already angry with the Athenians for supporting the city-state of Corcyra in its earlier quarrel with Corinth and for making an alliance with Corcyra and its formidable navy. The Spartans issued their ultimatums in order to placate the Megarians and, more importantly, the Corinthians with their powerful naval force. The Corinthians had bluntly informed the Spartans that they would withdraw from the Peloponnesian League and add their ships to the Athenian alliance if the Spartans delayed any longer in backing them in their dispute with the Athenians over Potidaea; this threat forced the Spartans to draw a line in the sand with Athens.

That line was drawn when the Spartans demanded that the Athenians rescind the Megarian Decree, as the economic sanctions are called today, or face war. In answer to this demand, Pericles is said to have replied frostily that the Athenian assembly had passed a law barring anyone from taking down the inscribed panel on which the text of the sanctions against Megara had been publicly displayed. “All right, then,” exploded the head of the Spartan delegation, “you don’t have to take the panel down. Just turn its inscribed side to the wall. Surely you have no law prohibiting that!” (Plutarch, Pericles 30). This anecdote about the Megarian Decree bluntly exposes the rancor that had come to characterize Spartan-Athenian relations in the late 430s. In the end, then, the actions of lesser powers pushed the two great powers, Athens and Sparta, over the brink to open conflict in 431.

The dispute over Athenian sanctions against Megara, as well as over its use of force against Potidaea and alliance with Corcyra, reflected the larger issues of power motivating the hostility between Athens and Sparta. The Spartan leaders feared that the Athenians would use their superiority in long-distance offensive weaponry—the naval forces of the Delian League—to destroy Spartan control of the Peloponnesian League. The majority in the Athenian assembly, for their part, resented Spartan interference in their freedom of action. For example, Thucydides portrays Pericles as making the following arguments in a speech to his fellow male citizens: “If we do go to war, harbor no thought that you went to war over a trivial affair. For you this trifling matter is the assurance and the proof of your determination. If you yield to the enemy’s demands, they will immediately confront you with some larger demand, since they will think that you only gave way on the first point out of fear. But if you stand firm, you will show them that they have to deal with you as equals. . . . When our equals, without agreeing to arbitration of the matter under dispute, make claims on us as neighbors and state those claims as commands, it would be no better than slavery to give in to them, no matter how large or how small the claim may be” (The Peloponnesian War 1.141).

Thucydides’ rendition of Pericles’ strongly worded “slippery slope” argument, to the effect that compromise inevitably leads to “slavery,” certainly has a ring of truth. (It is no accident that historians criticize the English prime minister Neville Chamberlain for giving in to Adolf Hitler’s demand in A.D. 1938 to annex Czechoslovakia’s Sudetenland, because it only encouraged the Nazi dictator to undertake even bolder takeovers.) People still quote the saying “Give ’em an inch and they’ll take a mile!” because that is often the reality. At the same time, surely there are times and places when compromise with an opponent makes sense as a way to avoid a destructive and unpredictable war. But is that dishonorable, even if prudent? Would it matter if it was? Were the Athenians, when they were persuaded by Pericles in 431 B.C. to reject the Spartan ultimatum, remembering their reply to the Spartans during the Persian Wars in 479, when they said there was no offer from the Persian king that could induce them to collaborate in reducing the Greeks to “slavery”? If so, were the circumstances actually analogous? Was the notion of “slavery” the right metaphor to characterize what would have resulted if the Athenians had negotiated one more time in 431? Or did the Spartans truly give them no option except to go to war? The ambiguity of the circumstances leading up to the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War and Thucydides’ brilliant dramatization of the motives of the Athenians and the Spartans provide, it seems to me, a fascinatingly provocative example of how ancient Greek history can be “good to think with” on the enduring issue of when we can compromise with our opponents and when we cannot.

In assigning formal blame for the war, it is important to remember that the Athenians had offered to submit to arbitration to resolve the Spartan complaints, the procedure officially mandated under the sworn terms of the peace treaty of 446–445 B.C. Despite the oath they had taken then, the Spartans nevertheless refused arbitration because they could not risk the defection of Corinth from their alliance if the decision went against them. The Spartans needed Corinth’s sizable fleet to combat Athens’s formidable naval power. The Spartan refusal to honor an obligation imposed by an oath amounted to sacrilege. Although the Spartans continued to argue that the Athenians were at fault for having refused all concessions, they felt deeply uneasy about the possibility that the gods might punish them for breaking their sworn word. The Athenians, on the other hand, exuded confidence that the gods would favor them in the war because they had respected their obligation under the treaty.

Athens’s large fleet and stone fortifications made its urban center and main harbor at Piraeus impregnable to direct attack. Already by the 450s B.C. the Athenians had encircled the city with a massive wall and fortified a broad corridor with a wall on both sides leading all the way to Piraeus some four miles to the west (see plan 1 in chapter 6). In the late 460s Cimon had spent great sums to lay the foundations for the first two Long Walls, as they were called, and Pericles had seen to their completion in the early 450s, using public funds. A third wall was added about 445. The technology of military siege machines in the fifth century B.C. was not advanced enough to break through fortifications of stone with the thickness of Athens’s Long Walls. Consequently, no matter what level of damage Spartan invasions inflicted on the agricultural production of Attica in the farm fields outside the walls around the city center, the Athenians could feed themselves by importing food on cargo ships through their fortified port; they could guard the shipping lanes with their incomparable fleet. They could pay for the food and its transportation with the huge financial reserves they had accumulated from the dues of the Delian League and the revenue from their silver mines at Laurion; they minted that silver into coins that were highly desired as an internationally accepted currency (fig. 8.1). The Athenians could also retreat safely behind their walls when the Spartan infantry attacked their own less-powerful land army. From their unassailable position, they could launch surprise attacks against Spartan territory by sending warships from the fortified harbor to land troops behind enemy lines. Like aircraft in modern warfare before the invention of radar warning systems, Athenian warships could swoop down unexpectedly on their enemies before they could prepare to defend themselves. Pericles therefore devised a two-pronged war strategy for Athens: Avoid set battles on land with the Spartans’ infantry, even when they ravaged Athenian territory, but use the fleet to attack the Spartans’ countryside and that of their allies. In the end, he predicted, the superior resources of Athens in money and men would enable it to win a war of attrition. What was required was consistent guidance from Athens’s leaders and firm dedication from its people. They would all suffer, but they would survive to prevail in the end—if they had the will to stay the course.

Fig. 8.1: Silver coins minted at Athens became a widely accepted currency because people everywhere trusted the quality of their precious metal; as a reassurance to the international market, the Athenians did not change the design for centuries. This fifth-century B.C. example, like all the rest, features a profile of Athena on the front and an owl, her sacred bird, on the back; in slang, the coins were called “owls.” Courtesy of the American Numismatic Society.

The gravest difficulty in carrying out Pericles’ strategy was that it required the many Athenians who resided outside the city center to abandon their homes and fields to be pillaged and burned by the Spartan army during its regular invasions of Attica each year. As Thucydides reports, people hated coming in from the countryside, where “most Athenians were born and bred; they grumbled at having to move their entire households [into Athens] . . . and abandoning their normal way of life, leaving behind what they regarded as their true city” (The Peloponnesian War 2.16). In 431 B.C. the Spartans opened hostilities by invading Attica for the first time and proceeded to destroy property in the countryside, hoping to force the Athenians into an infantry battle. The country dwellers of Attica became fiercely angry when, standing safely on Athens’s walls, they watched the smoke rise from their homes and fields as they burned. The men of Acharnae, the most populous deme of Attica and visible just to the north from the city walls, were particularly furious; Pericles barely managed to stop the citizen-militia from rushing out in a rage to take on the Spartan hoplites in a land battle. Somehow he managed to prevent the assembly from meeting to authorize this change in strategy; Thucydides does not reveal precisely how Pericles blocked normal democratic procedures at this critical moment. The Spartan army returned home from this first attack on Athenian territory after staying only about a month in Attica because it lacked the structure for resupply over a longer period and could not risk being away from Sparta too long from fear of a helot revolt. For these reasons, the annual invasions of Attica that the Spartans sent in the early years of the war never lasted longer than forty days. Even in this short time, however, the Spartan army could inflict losses on the countryside, which the citizens of Athens, holed up in their walled city, felt personally and painfully.

The innate unpredictability of war soon undermined Pericles’ strategy for Athenian victory when an epidemic began to ravage Athens’s population in 430 B.C. and raged on for several years with disastrous consequences. The disease struck while the Athenians from the countryside were jammed together with the city’s usual residents in unsanitary conditions behind the city walls. The failure to provide adequate housing and sanitation for this new influx of population into the city was a devastating oversight by Pericles and his fellow leaders. The symptoms of the disease, described in detail by Thucydides, were gruesome: vomiting, convulsions, painful sores, uncontrollable diarrhea, and fever and thirst so extreme that sufferers threw themselves into water tanks vainly hoping to find relief in the cold water. The rate of mortality was so high that it crippled Athenian ability to man the naval expeditions that Pericles’ wartime strategy demanded. Pericles himself died of the disease in 429. He apparently had not anticipated the damage to Athens’s conduct of the war that the loss of his firm leadership would mean. The epidemic also seriously hampered the war effort by destroying the Athenians’ confidence in their relationship with the gods. “As far as the gods were concerned, it seemed not to matter whether one worshipped them or not because the good and the bad were dying indiscriminately,” Thucydides wrote (The Peloponnesian War 2.53).

The epidemic hurt the Athenians materially by devastating their population, politically by removing their foremost leader, Pericles, and psychologically by damaging their self-confidence and weakening communal social and religious norms. Nevertheless, they refused to give up. Despite the loss of manpower inflicted by the deadly disease, Athenian military forces proved effective in several locations. Potidaea, the ally whose rebellion had worsened the hostility between Athens and Corinth, was compelled to surrender in 430 B.C. The Athenian navy won two major victories in 429 off Naupactus in the western Gulf of Corinth under the general Phormio. A serious revolt in 428–427 of allies on the island of Lesbos, led by the city-state of Mytilene, was forcefully put down. One of the most famous passages in Thucydides is the set of vivid speeches on the fate of the people of Mytilene presented by the Athenian orators Cleon and Diodotus (The Peloponnesian War 3.37–48). The opposing speeches respectively argued for capital punishment based on justice and clemency based on expediency. Their arguments represent stirring and provocative positions that bear on larger political and ethical questions about the effectiveness of punishment as a deterrent more than on the immediate issue of what to do about the rebels of Mytilene.

Equally impressive and even more disturbing is Thucydides’ report of the civil war that broke out on the island of Corcyra in 427 B.C., when the opposing factions in the city-state there, one supporting Athens and one Sparta, tried to gain advantage by appealing to these major powers in the Peloponnesian War. Thucydides’ blunt analysis describes how civil war can bring out the worst features of human nature and inflame deadly emotions, even among people who have lived all their lives as neighbors:

[The citizens supporting democracy in the civil war in the city-state of Corcyra] captured and executed all their enemies whom they could find. . . . They then proceeded to the sanctuary of Hera and persuaded about fifty of the suppliants [from the opposing faction] who had sought sacred refuge there to agree to appear in court. The democrats thereupon condemned every last one of the erstwhile suppliants to death. When the other suppliants who had refused to go to trial comprehended what was going on, most of them killed each other right there in the sanctuary. Some hanged themselves from trees, while others found a variety of ways to commit suicide. [For a week] the members of the democratic faction went on slaughtering any fellow citizens whom they thought of as their enemies. They accused their victims of plotting to overthrow the democracy, but in truth they killed many people simply out of personal hatred or because they owed money to the victims. Death came in every way and fashion. And, as customarily occurs in such situations, the killers went to every extreme and beyond. There were fathers who murdered their sons; men were dragged out of the temples to be put to death or simply butchered on the very altars of the gods; some people were actually walled up in the temple of Dionysus and left there to die [of starvation].

In numerous Greek cities these factional struggles produced many catastrophes—as happens and always will happen while human nature remains what it is. . . . During periods of peace and prosperity, cities and individuals alike adhere to more demanding standards of behavior, because they are not forced into a situation where they have to do what they do not want to do. But war is a violent teacher; in stealing from people the ability to fulfill their ordinary needs without undue difficulty, it reduces most people’s temperaments to the level of their present circumstances.

So factional conflicts erupted in city after city, and in cities where the struggles took place at a later date than in other cities, the knowledge of what had already happened in other places led to even more inventiveness in attacking rivals and to unprecedented atrocities of revenge. In accordance with the changes in conduct, words, too, exchanged their customary meanings to adapt to people’s purposes. What had previously been described as a reckless act of aggression was now seen as the courage demanded of a loyal co-conspirator in a faction; to give any thought to the future and not take immediate action was simply another way of calling someone a coward; any suggestion of moderation was just an attempt to cover up one’s cowardice; ability to understand different sides of an issue meant that one was wholly unsuited to take action. Fanatical enthusiasm was the defining characteristic of a real man. . . . Ties of family were weaker obligations than belonging to a faction, since faction members were more prepared to go to any extreme for any reason whatsoever.

—(The Peloponnesian War 3.81–82)

The manpower losses caused by the great epidemic prevented Athens from launching as many naval expeditions as would have been needed to make Periclean strategy effective, and the annual campaigns of the war in the early 420s B.C. brought additional losses to both sides without any significant opportunity for one side to overcome the other decisively. In 425, however, Athens stumbled upon a golden chance to secure an advantageous peace, when the Athenian general Cleon won an unprecedented victory by capturing some 120 Spartan warriors and about 170 allied Peloponnesian troops after a protracted struggle on the tiny island of Sphacteria at Pylos in the western Peloponnese. No Spartan soldiers had ever before surrendered under any circumstances. They had always taken as their soldiers’ creed the sentiment expressed by the legendary advice of a Spartan mother handing her son his shield as he went off to war: “Come home either with this or on it” (Plutarch, Moralia 241F), meaning that he should return either as a victor or as a corpse. By this date, however, the population of Spartan male citizens was so diminished that to lose even such a small group was perceived as intolerable. The Spartan leaders therefore offered the Athenians favorable peace terms if they would return the captured warriors. Cleon’s unexpected success at Pylos had vaulted him into a position of political leadership, and he advocated a hard line toward Sparta. Thucydides, who apparently had no love for Cleon, called him “the most violent of the citizens” (The Peloponnesian War 3.36). At Cleon’s urging, the Athenian assembly refused to make peace with Sparta: He convinced his fellow citizens that they could win even more, and they took the gamble.

The lack of wisdom in the Athenian decision became clear with the next unexpected development of the war: a sudden reversal in the traditional Spartan policy against waging extended military expeditions far from home. In 424 B.C. the Spartan general Brasidas led a land army on a daring campaign against Athenian strongholds in far northern Greece hundreds of miles from Sparta. His most important move came when he succeeded in getting the defection to the Spartan side of the strategic city Amphipolis, an important Athenian colony near the coast that the Athenians regarded as essential to their strategic position. This coup by Brasidas robbed Athens of access to gold and silver mines and a major source of timber for warships. Even though Thucydides was not directly responsible for Athens’s having lost Amphipolis, the Athenian assembly stripped him of his command and forced him into exile because he had been the commander in charge of the region when this catastrophe took place.

Cleon, the most prominent and influential leader at Athens after the Athenian victory at Pylos in 425 B.C., was dispatched to northern Greece in 422 to try to stop Brasidas. As events turned out, both he and Brasidas were killed at Amphipolis in 422 in a battle won by the Spartan army. Their deaths deprived each side of its most energetic military commander and opened the way to negotiations. Peace came in 421, when both sides agreed to resurrect the balance of forces as it had been in 431. The agreement made in that year is known as the Peace of Nicias, after the Athenian general who was instrumental in convincing the Athenian assembly to agree to a peace treaty. The Spartan agreement to the peace revealed a fracture in the coalition of Greek states allied with Sparta against Athens and its allies, because the Corinthians and the Boeotians refused to join the Spartans in signing the treaty.

The Peace of Nicias failed to quiet those on both sides of the conflict who were pushing for a decisive victory. A brash, rich, and young Athenian named Alcibiades (c. 450–404 B.C.) was especially active in agitating against the uneasy peace. He was a member of one of Athens’s wealthiest and most distinguished families, and he had been raised in the household of Pericles after his father had died in battle against allies of Sparta in 447, when Alcibiades was only about three years old. By now in his early thirties—a very young age at which to have achieved political influence, by Athenian standards—Alcibiades rallied support in the Athenian assembly for action against Spartan interests in the Peloponnese. Despite the formal agreement of peace between Sparta and Athens, he managed to cobble together a new alliance among Athens, Argos, and some other Peloponnesian city-states that were hostile to Sparta. He evidently believed that Athenian power and security, as well as his own career, would be best served by a continuing effort to weaken Sparta. Since the geographical location of Argos in the northeastern Peloponnese placed it astride the principal north–south route in and out of Spartan territory, the Spartans had reason to fear the alliance created by Alcibiades. If the alliance held, Argos and its allies could virtually pen the Spartan army inside its own borders. Nevertheless, support for the coalition seems to have been shaky in Athens, perhaps because the memory of the ten years of war just concluded was still vivid. The Spartans, recognizing the threat to themselves, met and defeated the forces of the coalition in battle at Mantinea in the northeastern Peloponnese in 418. The Peace of Nicias was now a dead letter, even if the war was not yet formally recommenced. When an Athenian force later raided Spartan territory, it flared into the open once again. Thucydides remarked that in his opinion the Peloponnesian War had never really ceased, despite the Peace of Nicias; the hostility between Athens and Sparta had grown too deep and too fierce to be resolved by a treaty. Someone had to win for the war truly to be over.

In 416 B.C. an Athenian force besieged the tiny city-state situated on the island of Melos in the Mediterranean Sea southeast of the Peloponnese. The Melians were sympathetic to Sparta but had taken no active part in the war, although an inscription has been interpreted to mean that they had made a monetary contribution to the Spartan war effort. (It is possible, however, that this text in fact refers to events after the fall of the city in this siege, at a time when refugees from Melos gave small amounts of money to try to win Spartan favor.) In any case, Athens had long considered Melos an enemy because Nicias had led an unsuccessful attack on the island in 426. The Athenians now once again demanded that the Melians support their anti-Spartan alliance voluntarily or face destruction, but the Melians refused to submit despite the overwhelming superiority of the Athenian force. What the Athenians hoped to gain by this campaign is not clear, because Melos had neither much property worth plundering nor a strategically crucial location. At bottom, the Athenians simply may have been infuriated by the Melians’ refusal to join their alliance and comply with their wishes. When Melos eventually had to surrender to the besieging army of Athenian and allied forces, its men were killed and its women and children sold into slavery. An Athenian community was then established on the island. Thucydides portrays Athenian motives in the siege of Melos as concerned exclusively with the amoral politics of the use of force, while the Melians he shows as relying on an expedient concept of justice that they insisted should govern relations between states. He represents the leaders of the opposing sides as participating in a private meeting to discuss their views of what issues are at stake. This passage in his history (The Peloponnesian War 5.84–114), called the Melian Dialogue, offers a chillingly realistic insight into the clash between ethics and power in international politics and remains timeless in its insight and its bluntness.

There was no question about the war being on again when in 415 B.C. Alcibiades convinced the Athenian assembly to launch a massive naval campaign against the city-state of Syracuse, a Spartan ally on the large and prosperous island of Sicily. This wealthy city near the southeastern corner of the island represented both the richest prize and the largest threat to Athenian success in the war if the Syracusans sent aid to the Spartans. With this expedition, the Athenians and their allies would pursue the great riches awaiting conquerors in Sicily and prevent any cities there from supporting their enemies. In launching the Sicilian expedition, the Athenians’ stated reason for acting was that they were responding to a request for military protection from the Sicilian city of Egesta (also known as Segesta), with which the Athenians had previously made an alliance. The Egestans encouraged the Athenians to prepare a naval expedition to Sicily by misrepresenting the extent of the financial resources that they would be able to contribute to the military campaign against Athens’s enemies on the island.

In the debate preceding the vote on the expedition, Alcibiades and his supporters argued that the numerous warships in the fleet of Syracuse represented an especially serious potential threat to the security of the Athenian alliance because they could sail from Sicily to join the Spartan alliance in attacks on Athens and its allies. Nicias led the opposition to the proposed expedition, but his arguments for caution failed to counteract the enthusiasm for action that Alcibiades generated with his speeches. The latter’s aggressive dreams of the glory to be won in battle appealed especially to young men who had not yet experienced the brutal realities of war for themselves. The assembly resoundingly backed his vision by voting to send to Sicily the greatest force ever to sail from Greece.

The arrogant flamboyance of Alcibiades’ private life and his blatant political ambitions had made him many enemies in Athens, and the hostility to him reached a crisis point at the very moment of the expedition’s dispatch, when Alcibiades was suddenly accused of having participated in sacrilegious events on the eve of the sailing. One incident involved the herms of Athens. Herms, stone posts with a sculpted set of erect male genitals and a bust of the god Hermes, were placed throughout the city as guardians of doorways, boundaries, and places of transition. A herm stood at nearly every street intersection, for example, because crossings were, symbolically at least, zones of special danger. Unknown vandals outraged the public by knocking off the statues’ phalluses just before the fleet was to sail. When Alcibiades was accused of having been part of the vandalism, his enemies immediately upped the ante by reporting that he had earlier staged a mockery of the Eleusinian Mysteries. This was an extremely serious charge of sacrilege and caused an additional uproar. Alcibiades pushed for an immediate trial while his popularity was at a peak and the soldiers who supported him were still in Athens, but his enemies cunningly got the trial postponed on the excuse that the expedition must not be delayed. Alcibiades therefore set off with the rest of the fleet, but it was not long before a messenger was dispatched telling him to return alone to Athens for trial. Alcibiades’ reaction to this order was dramatic and immediate: He defected to Sparta.

The defection of Alcibiades left the Athenian expedition against Sicily without a strong and decisive leader. The Athenian fleet was so large that it won initial victories against Syracuse and its allies even without brilliant leadership, but eventually the indecisiveness of Nicias undermined the attackers’ successes. The Athenian assembly responded to the setbacks by authorizing large reinforcements led by the general Demosthenes, but these new forces proved incapable of defeating Syracuse, which enjoyed effective military leadership to complement its material strength. Alcibiades had a decisive influence on the quality of Syracusan military leadership because the Spartans followed his suggestion to send an experienced Spartan commander to Syracuse to combat the invading expedition. In 414 B.C. they dispatched Gylippus, who proved himself the tactical superior to the Athenian commanders on the scene. As what the Spartans called a mothax (“someone who doesn’t stick to his place in society”), Gylippus was a self-made man, so to speak, a member of a special class of “half-caste” citizens born to a Spartan father and a helot (or desperately poor citizen) mother. The population decline at Sparta had become so critical during the Peloponnesian War that the Spartans were allowing wealthier citizens to sponsor talented boys from these mixed backgrounds in joining the common messes, to bolster the number of men being raised as warriors and potential commanders.

The Spartans and their allies in Sicily eventually trapped the Athenian forces in the harbor of Syracuse, completely crushing them in a climactic naval battle in 413 B.C. When the survivors of the attacking force tried to flee overland to safety, they were either slaughtered or captured, almost to a man, including Nicias. The Sicilian expedition ended in inglorious defeat for the Athenian forces and the crippling of their navy, the city-state’s main source of military power. When the news of this catastrophe reached Athens, the citizens wept and wailed in horror.

Despite their fears, the Athenians did not give up, even when more troubles confronted them in the wake of the disaster in Sicily. Alcibiades’ defection caused Athens yet more problems when he advised the Spartan commanders to establish a permanent base of operations in the Attic countryside; in 413 B.C. they at last acted on his advice. Taking advantage of Athenian weakness in the aftermath of the enormous losses in men and equipment sustained in Sicily, the Spartans installed a garrison at Decelea in northeastern Attica, in sight of the walls of Athens itself. Spartan forces could now raid the Athenian countryside year-round; previously, the annual invasions dispatched from Sparta could never stay longer than forty days at time in Athenian territory, and only during the months of good weather. Now the presence of a permanent enemy garrison in Athenian territory made agricultural work in the fields dangerous and forced the Athenians huddling behind the city’s fortification walls to rely even more heavily than in the past on food imported by sea. The damage to Athenian fortunes increased when twenty thousand slaves sought refuge in the Spartan camp. Some of these fugitives seem to have come from the silver mines at Laurion, which made it harder for Athens to keep up the flow of revenue from this source. So immense was the distress caused by the crisis that an extraordinary change was made in Athenian government: A board of ten officials was appointed to manage the affairs of the city. The stresses of a seemingly endless war had convinced the citizens that the normal procedures of their democracy had proved sadly inadequate to the task of keeping them safe. They had lost confidence in their founding principles. As Thucydides observed, “War is a violent teacher” (The Peloponnesian War 3.82).

The disastrous consequences of the Athenian defeat in Sicily in 413 B.C. became even worse when Persia once again took a direct hand in Greek affairs on the side of Sparta. Athenian weakness seemed to make this an opportune time to reassert Persian dominance in western Anatolia by stripping away Athens’s allies in that region. The satraps governing the Persian provinces in the area therefore began to supply money to help the Spartans and their allies construct and man a fleet of warships. At the same time, some disgruntled allies of Athens in Ionia took advantage of the depleted strength of their alliance’s leader to revolt from the Delian League, instigated by the powerful city-state of the island of Chios in the eastern Aegean. Once again it was Alcibiades who was getting his revenge on his countrymen: He had urged the Ionians to rebel from Athens when the Spartans had sent him there in 412 to stir up rebellion. Since Ionia provided bases for attacking the shipping lanes by which the Athenians imported the grain from the fertile shores of the Black Sea to the northeast and from Egypt to the southeast, which they needed to survive, losing their Ionian allies threatened them with starvation.

Even in the face of these mounting hardships and dangers, the Athenians continued to demonstrate a strong communal will and refusal to stop fighting for their independence. They devoted their scarce resources to rebuilding their fleet and training new crews to row the triremes, drawing on the emergency reserve funds that had been stored on the Acropolis since the beginning of the war. Astonishingly, by 412–411 Athenian naval forces had revived sufficiently that they managed to prevent a Corinthian fleet from sailing to aid Chios, to lay siege to that rebellious island ally, and to win other battles along the Anatolian coast. “Never say die” was evidently their national motto.

Despite this military recovery, the bitter turmoil in Athenian politics and the steep decline in revenues caused by the Sicilian disaster opened the way for a group of men from the social elite, who had long harbored contempt for the broad-based direct democracy of their city-state, to stage what amounted to an oligarchic coup d’état. They insisted that a small group of elite leaders was now needed to manage Athenian policy in response to the obvious failures of the democratic assembly. Alcibiades furthered their cause by sending messages home that he could make an alliance with the Persian satraps in western Anatolia and secure funds from them for Athens—but only on the condition that the democracy abolish itself and install an oligarchy. He apparently hoped that this abrupt change in government would pave the way for him to return to Athens. Alcibiades had reason to want to return, because his negotiations with the satraps had by now aroused the suspicions of the Spartan leaders, who rightly suspected that he was intriguing in his own interests rather than theirs. He had also made Agis, one of Sparta’s two kings, into a powerful enemy by seducing his wife.

By holding out the lure of Persian gold, Alcibiades’ promises helped the oligarchic sympathizers in Athens to play on the assembly’s fears and hopes. In 411 B.C. the Athenian oligarchs succeeded in having the assembly members turn over all power to a group of four hundred men; the voters had been persuaded that this smaller body would provide better guidance for foreign policy in the war and, most importantly, boost Athens’s finances by doing a deal with the Persian king. These four hundred Athenians were supposed in turn to choose a group of five thousand men to act as the city’s ultimate governing body, creating a broad rather than a narrow oligarchy. In fact, however, the four hundred kept all power in their own hands, preventing the five thousand from having any effect on government. This duplicitous regime soon began to fall apart, however, when the oligarchs struggled with each other for dominance; none of them could tolerate appearing to bow to the superior wisdom of a fellow oligarch. The end for this revolutionary government came when the crews of the Athenian war fleet, which was stationed in the harbor of the friendly island city-state of Samos in the eastern Aegean, threatened to sail home to restore democracy by force unless the oligarchs stepped aside. In response, a mixed democracy and oligarchy, called the Constitution of the Five Thousand, was created, which Thucydides praised as “the best form of government that the Athenians had known, at least in my time” (The Peloponnesian War 8.97). This new government voted to recall Alcibiades and other prominent Athenians who were in exile, hoping that these experienced men could improve Athenian military leadership and carry the war to the Spartans.

With Alcibiades as one of its commanders, the revived Athenian fleet won a great victory over the Spartans in early 410 B.C. at Cyzicus, in Anatolia, south of the Black Sea. The victorious Athenians intercepted the plaintive and typically brief dispatch sent by the defeated Spartans to their leaders at home: “Ships lost. Commander dead. Men starving. Do not know what to do” (Xenophon, Hellenica 1.1.23). The pro-democratic fleet demanded the restoration of full democracy at Athens, and within a few months after the victory at Cyzicus, Athenian government returned to the form and membership that it had possessed before the oligarchic coup of 411. It also returned to the uncompromising bellicosity that had characterized the decisions of the Athenian assembly in the mid-420s. Just as they had after their defeat at Pylos in 425, the Spartans offered to make peace with Athens after their defeat at Cyzicus in 410. The Athenian assembly once again refused the terms, however. Athens’s fleet then proceeded to reestablish the safety of the grain routes to the port at Piraeus and to compel some of the allies who had revolted to return to the alliance.

Unfortunately for the Athenians, their successes in battle did not lead to victory in the war. The aggressive Spartan commander Lysander ultimately doomed Athenian hopes by using Persian money to rebuild the Spartan fleet and by ensuring that this new navy had expert commanders. When in 406 B.C. he inflicted a defeat on an Athenian fleet at Notion, near Ephesus on the Anatolian coast, the Athenians blamed Alcibiades for the loss, even though he had been away on a mission at the time. He was forced into exile for the last time. The Athenian fleet won a victory later in 406 off the islands of Arginusae, south of the island of Lesbos, but a storm prevented the rescue of the crews of wrecked ships. Emotions at the loss of so many men ran so high at Athens that the commanders were put on trial as a group, even though that decision contradicted the normal legal guarantee of individual trials. They were condemned to death for alleged negligence. And then the assembly again rejected a Spartan offer of peace, guaranteeing the current state of things. Lysander thereupon secured more Persian funds, strengthened the Spartan naval forces further, and finally and decisively defeated the Athenian fleet in 405 in a battle at Aegospotami, near Lampsacus on the coast of Anatolia. Athens was now defenseless. Lysander blockaded the city and compelled its citizens to surrender in 404; they had no other choice but starvation. After twenty-seven years of near-continuous war, the Athenians found themselves at the mercy of their enemies.

Fortunately for the Athenians, the Spartan leaders resisted the demand made by their allies the Corinthians, the bitterest enemy of Athens, that the defeated city be totally destroyed. The Spartans feared that Corinth, with its large fleet and strategic location on the isthmus, potentially blocking access to and from the Peloponnese, might grow too strong if Athens were no longer in existence to serve as a counterweight. Instead of ruining Athens, Sparta installed a regime of anti-democratic Athenian collaborators to rule the conquered city. This group became known as the Thirty Tyrants. These Athenians came from the wealthy elite, which had always included a faction admiring oligarchy and despising democracy. Brutally suppressing the opposition from their fellow Athenians and stealing shamelessly from people whose only crime was to possess valuable property, these oligarchs embarked on an eight-month-long period of terror in their homeland during 404–403 B.C. The metic and famous speechwriter-to-be Lysias, for example, whose father had earlier moved his family from their native Syracuse at the invitation of Pericles, reported that the henchmen of the Thirty seized his brother for execution as a way to steal the family’s valuables. The plunderers even ripped the gold earrings from the ears of his brother’s wife in their pursuit of loot.

The rule of the Thirty Tyrants became so violent and disgraceful that the Spartans did not interfere when a pro-democracy resistance movement came to power in Athens after a series of street battles during a civil war between democrats and oligarchs in 403 B.C. To put an end to the internal strife that threatened to tear Athens apart, the newly restored democracy proclaimed a general amnesty, the first known in Western history. Under this agreement, all legal charges and official recriminations concerning crimes committed during the reign of terror were forbidden from that time onward. Athens’s government was once again a functioning democracy. Its financial and military strength, however, was shattered, and its society preserved the memory of a lethal divisiveness among its own citizens that no amnesty could completely dispel.

The Peloponnesian War drained the state treasury of Athens, splintered its political harmony, and devastated its military power. But that was not all the damage that it did. The nearly thirty years of war also exacted a heavy toll on Athenians’ domestic life. Many people both from the city and the countryside found their livelihoods threatened by the economic dislocations of the war. Women without wealth whose spouses or male relatives were killed in the war experienced particularly difficult times because dire necessity forced them to do what they had never done before: look for work outside the home to support themselves and their children.

The many people who made their homes outside the walls of the urban center suffered the most ruinous personal losses and disruptions during the war. These country dwellers periodically had to take refuge inside the city walls while the Spartan invaders wrecked their houses and barns and damaged the crops in their fields. If they did not also own a house in the city or have friends who could take them in, these families had to camp in public areas in Athens in cramped and unsanitary conditions, looking for shelter, food, cooking facilities, and water every day on the fly. The load that their presence put on Athens’s limited urban infrastructure inevitably caused friction between the refugees and the residents who were full-time city dwellers.

The war meant drastic changes in the ways that many households in Athens made their livings. The changes affected both those whose incomes depended on agriculture and those who operated their own small businesses. Wealthy families that had money and valuable goods stored up could weather the crisis by spending their savings, but most people had no financial cushion to fall back on. When the enemy destroyed harvests in the countryside, farmers used to toiling in their own fields outside the walls had to scrounge for work as day laborers in the city. Such jobs became increasingly scarce as the pool of men looking for them swelled. Men who rowed the ships of the Athenian fleet could earn wages for the time the ships were at sea, but they had to spend long periods away from their families in uncomfortable conditions and faced death in every battle and storm. Men and women who worked as crafts producers and small merchants or business owners in the city still had their livelihoods, but their income levels suffered because consumers had less money to spend.

The pressure of war on Athenian society became especially evident in the severe damage done to the prosperity and indeed the very nature of the lives of many comfortably well-off women whose husbands and brothers died during the conflict. Women of this socioeconomic level had traditionally done weaving at home for their own families and supervised the work of household slaves, but the men had earned the family’s income by farming or practicing a trade. With no working male to provide for them and their children, these women were now forced to take the only jobs open to them in such low-paying occupations as wet nurse, weaver, or even vineyard laborer, when there were not enough men to meet the need in the fields. These circumstances involved more women in activities conducted outside their homes and brought them into more contact with strangers than ever before, but this change did not lead to a woman’s movement in the modern sense or to any inclusion of women in Athenian political life. After the war, Aristophanes produced a comedy, The Assemblywomen (c. 392 B.C.), that portrayed women disguising themselves as men to take over the assembly and revolutionize Athenian government to spend its resources prudently, following the principles of financial planning that women used to manage their families’ household accounts. In the play, most of the men of Athens in the end have to admit that the women will do a better job running the city-state than they have. In real life, this vision of politically empowered women remained a fantasy confined to the comic stage.

The financial stability of the city-state of Athens declined to a desperate state during the later stages of the Peloponnesian War as a result of the many interruptions to agriculture and from the reduction of income from the state’s silver mines, which occurred after the Spartan army took up a permanent presence in 413 B.C. in Athenian territory in a fortified base at Decelea. Now that the enemy was present year-round, the lucrative mining, so important to the city-state’s treasury, could not operate as reliably, because the mines and smelting facilities were at Laurion, which was located within easy raiding distance of the invader’s position. Some public building projects in the city itself were kept going, like the Erectheum, a temple to Athena on the Acropolis, to demonstrate the Athenian will to carry on and also as a device for infusing some money into the crippled economy by paying construction workers. But the demands of the war depleted the funds available for many nonmilitary activities. The great annual dramatic festivals, for example, had to be cut back. The financial situation had become so critical by the end of the war that Athenians were required to exchange their silver coins for an emergency currency of bronze thinly plated with silver to be used in local circulation. The regular silver coins, along with gold coins that were minted from golden objects borrowed from Athens’s temples, were then used to pay war expenses. This creation of what could be called a “scrip” currency, which has no intrinsic worth, to replace in the domestic economy the precious-metal coins that did have intrinsic value, signaled that Athens was very nearly a bankrupt political state.

The plots and characters of Athenian comedies produced during the Peloponnesian War reflected the growing stresses of everyday life during these three decades of death, destruction, and despair. Comedy was very popular in ancient Greece, as in every other human society, and it existed in various forms (fig. 8.2). At Athens, comic plays were the other main form of public dramatic art besides tragedies. Like tragic plays, comedies were composed in verse and had been presented annually in the city since early in the fifth century B.C. They formed a separate competition in the Athenian civic festivals in honor of Dionysus in the same outdoor theater used for tragedies. The ancient evidence does not make clear whether women could attend the performances of comedies, but if they could see tragedies, it seems likely that they could attend comedies as well. The all-male casts of comic productions consisted of a chorus of twenty-four members in addition to regular actors. Unlike tragedy, comedy was not restricted to having no more than three actors with speaking parts on stage at the same time. The beauty of the soaring poetry of the choral songs of comedy was matched by the ingeniously imaginative fantasy of its plots, which almost always ended with a festive resolution of the problems with which they had begun. For example, the story of Aristophanes’ comedy The Birds, produced in 414 B.C. as the war in Sicily raged on, has two men trying to escape the wrangles and disappointments of current everyday life at Athens and the regulations of the Athenian Empire by running away to seek a new life in a world called Cloudcuckooland that is inhabited by talking birds, portrayed by the chorus in colorful bird costumes. Unfortunately for the avian residents of this paradise, the human immigrants turn out to be eager to take over for their own pleasure and advantage, which can include bird sacrifices.

The author’s immediate purpose in writing a comic play was to create beautiful poetry and raise laughs at the same time, in the hope of winning the award for the festival’s best comedy. The plots of fifth-century Athenian comedies primarily dealt with contemporary issues and personalities, while much of their humor had to do with explicit references to sex and bodily functions, and much of their dialogue included uncensored and highly colorful profanity. Insulting verbal attacks on prominent men, such as Pericles or Cleon, the victor of Pylos, were a staple of the comic stage. Pericles apparently tried to impose a ban on this sort of comic criticism in response to scathing treatment that he received in the dialogues of comedies produced after the revolt of Samos in 441–439 B.C., but the measure was soon rescinded. Cleon later was so outraged by the way he was portrayed on the comic stage by Aristophanes that he sued the playwright. When Cleon lost the case, Aristophanes responded by pitilessly parodying him as a degenerate foreign slave in The Knights, of 424 B.C. Even prominent men who were not portrayed as characters on stage could nevertheless fall prey to insults in the dialogue of comedies as sexually effeminate and cowards. Women characters who are made figures of fun and ridicule in comedy, however, seem to have been fictional and not avatars of actual women from Athenian society.

Fig. 8.2: This deep vase, for mixing wine with water at drinking parties, is decorated with a painting of a comic actor from Magna Graecia wearing a mask with prominent facial features and a padded costume with an exaggerated shape. Ancient Greek comedy took various forms, with parody, farce, and criticism of politicians being popular features of the shows. Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY.

Slashing satire directed against the mass of ordinary citizens seems to have been unacceptable in Athenian comedy, but fifth-century comic productions often criticized governmental policies by blaming individual political leaders for decisions that the assembly as a whole had in fact voted to implement. The strongly critical nature of comedy was never more evident than during the war. Several of the popular comedies of Aristophanes had plots in which characters arranged peace with Sparta, even though the comedies were produced while the war was still being fiercely contested and the assembly had rejected all such proposals. In The Acharnians of 425 B.C., for example, the protagonist arranges a separate peace treaty with the Spartans for himself and his family while humiliating a character who portrays one of Athens’s prominent military commanders of the time. In other words, the triumphant hero in this play was a traitor who got away with betraying Athens. The play won first prize in competition for comedies that year, a fact that underlines the strength of the freedom of public speech in Classical Age Athens and suggests just how much many citizens yearned to end the war and return to “normal” life.

The most striking of Aristophanes’ comedies are those in which the main characters, the heroes of the plot, are women, who use their wits and their solidarity with one another to compel the men of Athens to overthrow basic policies of the city-state. Most famous of Aristophanes’ comedies depicting powerfully effectual women is Lysistrata of 411 B.C., named after the female lead. It portrays the women of Athens compelling their husbands to end the Peloponnesian War. The women first use force to blockade the Acropolis, where Athens’s financial reserves are kept, and prevent the men from squandering the city-state’s money any further on the war. The women then beat back an attack on their position by the old men who have remained in Athens while the younger men are out on campaign in the war. When their husbands return from the battlefield, the women refuse to have sex with them. Teaming with the women of Sparta on this sex strike, which is portrayed in a series of sexually explicit comic episodes, they finally coerce the men of Athens and Sparta to agree to a peace treaty.

Lysistrata presents women acting bravely, aggressively, and with international cooperation against men who seem bent both on destroying their family life by staying away from home for long stretches while on military campaign and on ruining their city-states by prolonging a pointless war. In other words, the play’s powerful women take on masculine roles to preserve the traditional way of life of the community. Lysistrata herself emphasizes this point in the very speech in which she insists that women have the intelligence and judgment to make political decisions. She came by her knowledge, she says, in the traditional way: “I am a woman, and, yes, I have brains. And I’m not badly off for judgment. Nor has my education been bad, coming as it has from my listening often to the conversations of my father and the elders among the men” (Lysistrata, lines 1124–1127). Lysistrata is here explaining that she was educated in the traditional way, by learning from older men. Her old-fashioned training and good sense allowed her to see what needed to be done to protect the community. Like the heroines of tragedy, Lysistrata is a reactionary: She wants to put things back the way they were in the past when everything was better. To do that, however, she has to act like a revolutionary. The play’s message that Athenians should concern themselves with preserving the old ways before all was lost evidently failed to impress the male voters in the assembly, as they failed to end the war despite Lysistrata’s having shown them how to make that happen. Somehow, we can guess, the desire to maintain the city-state’s political independence and international power trumped the wish for peace. We can also wonder what role notions of pride and honor played in the decision to not work toward a negotiated settlement. History shows over and over how important those sentiments are to human beings, for better or for worse.

The losses of population, the ravages of epidemic disease, and the financial damage caused by the war created ongoing problems for Athenians. Not even the amnesty that accompanied the restoration of Athenian democracy in 403 B.C. could quench all the social and political hatreds that the war and the rule of the Thirty Tyrants had enflamed. Socrates, the famous philosopher, became the most prominent casualty of this divisive bitterness. His trial for impiety in 399 ended with him being sentenced to death. Through it all, however, the traditional institution of the Athenian household—the family members and their personal slaves—survived the war as the fundamental unit of the city-state’s society and economy. Gradually, postwar Athens recovered much of its former prosperity and its role as leader of other Greek city-states, but in the end it never recovered fully. Athens’s lesser financial and military power in the fourth century B.C. was going to prove extremely consequential for the city-state’s freedom and its place in the world when the threat of domination by the kingdom of Macedonia seemingly came out of nowhere during the reign of Philip II in mid-century, as we will see in the next chapter.

Many Athenian households lost fathers, sons, or brothers in the Peloponnesian War, but resourceful families in the opening decades of the fourth century B.C. following the end of the war found ways to compensate for the economic strain that these family tragedies created. An Athenian named Aristarchus, for example, is reported by the writer Xenophon (c. 428–354 B.C.) to have experienced financial difficulty because the turmoil of the war had severely reduced his income and also caused his sisters, nieces, and female cousins to come live with him. He found himself unable to support this expanded household of fourteen plus slaves. Aristarchus’s friend Socrates thereupon reminded him that his female relatives knew quite well how to make men’s and women’s cloaks, shirts, capes, and smocks, “the work considered the best and most fitting for women” (Memorabilia 2.7.10). Previously, the women had always just made clothing for their families and never had to try to sell what they made for profit. But other people did make a living by selling such clothing or by baking and selling bread, Socrates pointed out, and Aristarchus could have the women in his house do the same. The plan was a financial success, but the women complained that Aristarchus was now the only member of the household who ate without working. Socrates advised his friend to reply that the women should think of him as sheep did a guard dog: He earned his share of the food by keeping the wolves away from the sheep.

Most Athenian manufactured goods were produced in households like that of Aristarchus or in small shops, although a few larger businesses did exist. Among these were metal foundries, pottery workshops, and the shield-making factory employing 120 slaves owned by the family of Lysias (c. 459–380 B.C.); commercial enterprises larger than this were apparently unknown at this period. The metic Lysias had to use his education and turn to writing speeches for others to make a living after the Thirty Tyrants seized his property in 404 B.C. Metics could not own land in Athenian territory without special permission, but they enjoyed legal rights in Athenian courts that other foreigners lacked. In return, they paid taxes and served in the army when called upon. Lysias lived near the harbor of Athens, Piraeus, where many metics took up residence because they played a central role in the international trade in such goods as grain, wine, pottery, and silver from Athens’s mines, which passed through Piraeus. The safety of Athenian trade was restored to prewar conditions when the Long Walls that connected the city with the port, demolished after the war as punishment, were rebuilt by 393. Another sign of the improving economic health of Athens was that by the late 390s the city had resumed the minting of its famous and valuable silver coins to replace the worthless emergency coinage produced during the last years of the war.

The importation of grain through Piraeus continued to be crucial for meeting the food needs of the population of Athens. Even before the war, Athenian farms had been unable to produce enough of this dietary staple to feed the whole population. The damage done to farm buildings and equipment during the Spartan invasions of the Peloponnesian War made the situation worse. The Spartan establishment of a year-round base at Decelea near Athens from 413 to 404 B.C. had given these enemy forces an opportunity to do much more severe damage in Athenian territory than the usually short campaigns of Greek warfare allowed. The invaders had probably even had time to cut down many Athenian olive trees, the source of olive oil, which was widely used at home and also provided a valuable export commodity. Olive trees took a generation to replace because they grew so slowly. Athenian property owners after the war worked hard to restore their land and businesses to production, not only to rebuild their incomes but also to provide for future generations, because Athenian men and women felt strongly that their property, whether in land, money, or belongings, represented resources to be preserved for their descendants. For this reason, Athenian law allowed prosecution of men who squandered their inheritance.

Most working people probably earned little more than enough to clothe and feed their families. Athenians usually ate only two meals a day, a light lunch in midmorning and a heavier meal in the evening. Bread baked from barley or, for richer people, wheat, constituted the main part of the diet. A family could buy its bread from small bakery stands, often run by women, or make it at home, with the wife directing and helping the household slaves to grind the grain, shape the dough, and bake it in a pottery oven heated by charcoal. Those few households wealthy enough to afford meat often grilled it over coals on a pottery brazier shaped much like modern portable barbeques. Vegetables, fruit, olives, and cheese provided the main variety in their diet for most people, with meat available to them only from the large animal sacrifices paid for by the state or wealthy citizens. The wine that everyone drank, usually much diluted with water, came mainly from local vineyards. Water from public fountains had to be carried into the house in jugs, a task that the women of the household had to perform themselves or see that the household slaves did. The war had hurt the Athenian state economically by giving a chance for escape to many of the slaves who worked in the silver mines in the Attic countryside, but few privately owned domestic slaves tried to run away, perhaps because they realized that they would simply be resold by the Spartans if they managed to escape their Athenian masters. All but the poorest Athenian families, therefore, continued to have at least a slave or two to do chores around the house and look after the children. If a mother did not have a slave to serve as a wet nurse to suckle her infants, she would hire a poor free woman for the job, if her family had money for the expense.

The most infamous episode in Athenian history in the aftermath of the Peloponnesian War consisted of the trial, conviction, and execution of Socrates (469–399 B.C.), the most famous philosopher of the fifth century B.C. Socrates had devoted his life to combating the idea that justice should be equated with the power to work one’s will over others. His passionate concerns to discover valid guidelines for leading a just life and to prove that justice is better than injustice under all circumstances gave a new direction to Greek philosophy: an emphasis on ethics. Although other thinkers before him, especially the poets and dramatists, had dealt with moral issues, Socrates was the first philosopher to make ethics and morality his central concern. Coming as it did during a time of social and political turmoil after the war, his death indicated the fragility of the principles of Athenian justice when put to the test in the crucible of lingering hatred and bitterness over the crimes of the Thirty Tyrants.

Compared to the financially most successful sophists, Socrates lived in poverty and publicly disdained material possessions, but he nevertheless managed to serve as a hoplite in the army and support a wife and several children. He may have inherited some money, and he also received gifts from wealthy admirers. Nevertheless, he paid so little attention to his physical appearance and clothes that many Athenians regarded him as eccentric. Sporting, in his words, a stomach “somewhat too large to be convenient” (Xenophon, Symposium 2.18), Socrates wore the same cheap cloak summer and winter and went without shoes no matter how cold the weather (fig. 8.3). His physical stamina was legendary, both from his tirelessness when he served as a soldier in Athens’s army and from his ability to outdrink anyone at a symposium.

Whether participating at a symposium, strolling in the agora, or watching young men exercise in a gymnasium, Socrates spent almost all his time in conversation and contemplation. In the first of these characteristics he resembled his fellow Athenians, who placed great value on the importance and pleasure of speaking with each other at length. He wrote nothing; our knowledge of his ideas comes from others’ writings, especially those of his pupil Plato (c. 428–347 B.C.). Plato’s dialogues, so called because they present Socrates and others in extended conversations about philosophy, portray Socrates as a relentless questioner of his fellow citizens, foreign friends, and various sophists. Socrates’ questions had the unsettling aim of provoking those with whom he spoke to examine the basic assumptions of their way of life. Employing what has come to be called the Socratic method, Socrates never directly instructed his conversational partners; instead, he led them to draw conclusions in response to his probing questions and refutations of their cherished but unexamined assumptions.

Fig. 8.3: This statuette portrays the controversial Athenian philosopher Socrates. He was famed for, among various other prominently idiosyncratic behaviors, wearing the same clothes all year round and going barefoot. Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY.

Socrates typically began one of his conversations by asking someone for a definition of an abstract quality, such as happiness, or an excellence, such as courage. For instance, in the dialogue Laches, named after the Athenian general who appears as one of the speakers in the dialogue, Socrates asks Laches and another distinguished military commander what makes a citizen a brave soldier. Socrates then proceeds by further questioning to show that the definitions of courage and instances of courageous behavior that they are now presenting actually contradict their other beliefs about what sort of behavior constitutes courage. In other words, he shows them that they really do not know what they are talking about, even though it concerns the very center of their expertise as military leaders.

This indirect but pitiless method of searching for the truth often left Socrates’ conversational partners in a state of puzzlement and unhappiness because they were forced to admit that they were ignorant of what at the start of the conversation they had assumed they knew perfectly well. They were forced to the uncomfortable admission that the principles by which they said they lived could not withstand close examination. Socrates insisted that he too was ignorant of the best definition of excellence but that his wisdom consisted of knowing that he did not know. He was trying to improve rather than undermine his companions’ personal values and their beliefs in morality, even though, as one of them put it, a conversation with Socrates made a man feel numb, just as if he had been stung by a stingray. Socrates wanted to discover through reasoning the universal standards that justified morality. He especially attacked the sophists’ view of conventional morality as the “shackles that bind nature” (Plato, Protagoras 337d), asserting that it equated human happiness with power and “getting more.”

Socrates passionately believed that just behavior was literally better for human beings than injustice: It created genuine happiness and well-being. Essentially, he seems to have argued that just behavior, which he saw as true excellence, was identical to knowledge, and that true knowledge of justice would inevitably lead people to choose good over evil and therefore to have truly happy lives, regardless of their level of financial success or physical comfort. In his view, the poor could be genuinely happy, too, perhaps more easily than the rich could, with their inevitable concerns for managing and increasing their wealth, none of which contributed to a life lived with real justice. Since Socrates believed that knowledge itself was sufficient for happiness, he asserted that no one knowingly behaved unjustly, and that behaving justly was always in the individual’s interest. It might appear, he maintained, that individuals could promote their interests by cheating or using force on those weaker than themselves, but this appearance was deceptive. It was in fact ignorance to believe that the best life was the life of unlimited power to pursue whatever one desired. Instead, the most desirable human life was concerned with excellence and guided by rational reflection about justice. This pure moral knowledge was all one needed for the good life, as Socrates defined it.

Despite Socrates’ laserlike focus on justice and his refusal, unlike the sophists, to offer courses and take fees for teaching young men, his effect on many people was as perturbing as had been the impact of the relativistic doctrines of the sophists. Indeed, Socrates’ refutation of his fellow conversationalists’ most treasured beliefs made some of them extremely upset. Unhappiest of all were the fathers whose sons, after listening to Socrates reduce someone to utter bewilderment, came home to try the same technique on their parents. Men who experienced this reversal of the traditional hierarchy of education between parent and child—the father was supposed to educate the son, not the other way round—had cause to feel that Socrates’ effect, even if it was not his intention, was to undermine the stability of society by questioning Athenian traditions and inspiring young men to do the same with the hot-blooded enthusiasm of their youth.

We cannot say with certainty what Athenian women thought of Socrates, or he of them. His views on human capabilities and behavior could be applied to women as well as to men, and he perhaps believed that women and men had the same basic capacity for justice. Nevertheless, the realities of Athenian society meant that Socrates circulated primarily among men and addressed his ideas to them and their situations. Xenophon reports, however, that Socrates had numerous conversations with Aspasia, the courtesan who lived with Pericles for many years. Plato has Socrates attribute his ideas on love to a woman, the otherwise unknown priestess Diotima of Mantinea. Whether these contacts were real or fictional remains uncertain.

The suspicion of many people that Socrates presented a danger to the traditions that held conventional society together gave Aristophanes the inspiration for his comedy The Clouds, of 423 B.C., so named from the role played by the chorus. In the play Socrates is presented as a cynical sophist, who for a fee offers instruction in his school in the Protagorean technique of making the weaker argument the stronger. When the protagonist’s son is transformed by Socrates’ instruction into a rhetorician able to argue that a son has the right to beat his parents—and then proceeds to do just that to his father, the protagonist ends the comedy by burning down Socrates’ “Thinking Shop.”