The Utilities folder (inside your Applications folder) is home to another batch of freebies: a couple of dozen tools for monitoring, tuning, tweaking, and troubleshooting your Mac.

The truth is, you’re likely to use only about six of these utilities. The rest are very specialized gizmos primarily of interest to network administrators or Unix geeks who are obsessed with knowing what kind of computer-code gibberish is going on behind the scenes.

Tip

Even so, there’s a menu command and a keystroke that can take you there. In the Finder, choose Go→Utilities (Shift- -U).

-U).

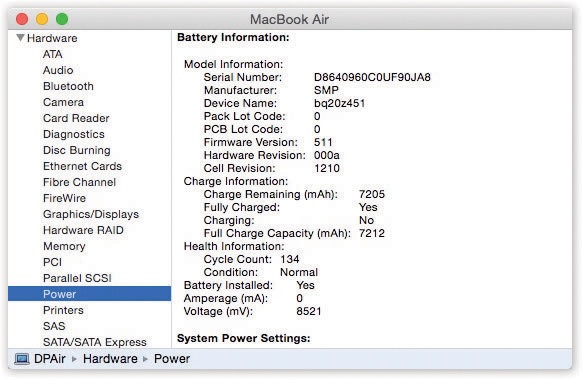

Activity Monitor is designed to let the technologically savvy Mac fan see how much of the Mac’s available power is being tapped at any given moment.

Even when you’re running only a program or two on your Mac, dozens of computational tasks (processes) are going on in the background. The top part of the window, which looks like a table, shows you all the different processes—visible and invisible—that your Mac is handling at the moment.

Check out how many items appear in the Process list, even when you’re just staring at the desktop. It’s awesome to see just how busy your Mac is! Some are easily recognizable programs (such as Finder), while others are background system-level operations you don’t normally see. For each item, you can see the percentage of the CPU being used, who’s using it (either your account name, someone else’s, or root, meaning the Mac itself), whether or not it’s been written as a 64-bit app, and how much memory it’s using.

Or use the View menu to see views like these:

All Processes. This is the complete list of running processes; you’ll notice that the vast majority are little Unix applications you never even knew you had.

All Processes, Hierarchically. In Unix, one process launches another, creating a tree-like hierarchy. The big daddy of them all is the process called launchd. Here and there, you’ll see some other interesting relationships: For example, the Dock launches DashboardClient.

My Processes. This list shows only the programs that pertain to your world, your login. There are still plenty of unfamiliar items, but they’re all running to serve your account.

System Processes. These are the processes run by root—that is, opened by macOS itself.

Other User Processes. Here’s a list of all other processes—“owned” by neither root nor you. Here you might see the processes being run by another account holder, for example (using fast user switching), or people who have connected to this Mac from across a network or the Internet.

Active Processes, Inactive Processes. Active processes are the ones that are actually doing something right now; inactive are the ones that are sitting there, waiting for a signal (like a keypress or a mouse click).

Windowed Processes. Now, this is probably what you were expecting: a list of actual programs with actual English names, like Activity Monitor, Finder, Safari, and Mail. These are the only ones running in actual windows, the only ones that are visible.

At the top of Activity Monitor, you’re offered five tabs that reveal intimate details about your Mac and its behind-the-scenes efforts (Figure 12-43):

CPU. As you go about your usual Mac business, opening a few programs, playing QuickTime movies, playing a game, and so on, you can see the CPU graphs rise and fall, depending on how busy you’re keeping the CPU. You see a different graph color for each of your Mac’s cores (independent subchips on your processor), so you can see how efficiently macOS is distributing the work among them.

Tip

You may also want to watch this graph right in your Dock (choose View→Dock Icon→Show CPU Usage) or in a bar at the edge of your screen (choose Window→Floating CPU Window→Horizontally).

Finally, there’s the View→Show CPU History command. It makes a resizable, real-time monitor window float on top of all your other programs, so you can’t miss it.

Memory. Here’s a glorious revelation of the state of your Mac’s RAM at the moment.

The graph shows “memory pressure”—how much your programs are straining the Mac’s memory. If, when your Mac is running a typical complement of programs, this graph is nearly filled up, then it’s time to consider buying more memory. You’re suffocating your Mac.

Energy. How much battery power is each of your programs responsible for sucking away? This fascinating tab tells all—including which programs are currently enjoying an App Nap (Up to Speed: Where Your Free Hour of Battery Life Came From).

Top: It can be a graph of your processor (CPU) activity, your RAM usage at the moment, your disk capacity, and so on. Usually, only the processes listed here with tiny icons beside their names are actual windowed programs—those with icons in the Finder, the ones you actually interact with.

The top-left Quit Process button (

) is a convenient way to jettison a locked-up program when all else fails.

) is a convenient way to jettison a locked-up program when all else fails.Bottom: If you double-click a process’s name, you get a dialog box that offers reams of data (mostly of interest only to programmers) about what that program is up to. (The Open Files and Ports tab, for example, shows you how many files that program has opened, often invisibly.)

Figure 12-43. The many faces of Activity Monitor.

Disk. Even when you’re not opening or saving a file, your Mac’s hard drive or flash storage is frequently hard at work, shuffling chunks of program code into and out of memory, for example. Here’s where the savvy technician can see exactly how frantic the disk is at the moment.

Network. Keep an eye on how much data is shooting across your office network with this handy tsunami of real-time data.

You use the AirPort Utility to set up and manage AirPort base stations (Apple’s wireless Wi-Fi networking routers).

If you click Continue, it presents a series of screens, posing one question at a time: what you want to name the network, what password you want for it, and so on. Once you’ve followed the steps and answered the questions, your AirPort hardware will be properly configured and ready to use.

This program has a split personality; its name is a description of its two halves:

Audio. When you first open Audio MIDI Setup, you see a complete summary of the audio inputs and outputs available on your Mac right now. It’s a like the Sound pane of System Preferences, but with a lot more geeky detail. Here, for example, you can specify the recording level for your Mac’s microphone, or even change the audio quality it records.

For most people, this is all meaningless, because most Macs have only one input (the microphone) and one output (the speakers). But if you’re sitting in your darkened music studio, humming with high-tech audio gear whose software has been designed to work with this little program, you’ll smile when you see this tab.

There’s even a Configure Speakers button, for those audiophilic Mac fans who’ve attached stereo or even surround-sound speaker systems to their Macs.

Tip

Using the

menu at the bottom of the window, you can turn your various audio inputs (that is, microphones, line inputs, and so on) on or off. You can even direct your Mac’s system beeps to pour forth from one set of speakers (like the one built into your Mac), and all other sound, like music, through a different set.

menu at the bottom of the window, you can turn your various audio inputs (that is, microphones, line inputs, and so on) on or off. You can even direct your Mac’s system beeps to pour forth from one set of speakers (like the one built into your Mac), and all other sound, like music, through a different set.MIDI. MIDI stands for Musical Instrument Digital Interface, a standard “language” for inter-synthesizer communication. It’s available to music software companies who have written their wares to capitalize on these tools.

When you choose Window→Show MIDI Window, you get a window that represents your recording-studio configuration. By clicking Add Device, you create a new icon that represents one of your pieces of gear. Double-click the icon to specify its make and model. Finally, by dragging lines from the “in” and “out” arrows, you teach your Mac and its MIDI software how the various components are wired together.

One of the luxuries of using a Mac that has Bluetooth is the ability to shoot files (to colleagues who own similarly clever gadgets) through the air, up to 30 feet away. Bluetooth File Exchange makes it possible, as described in Via Bluetooth.

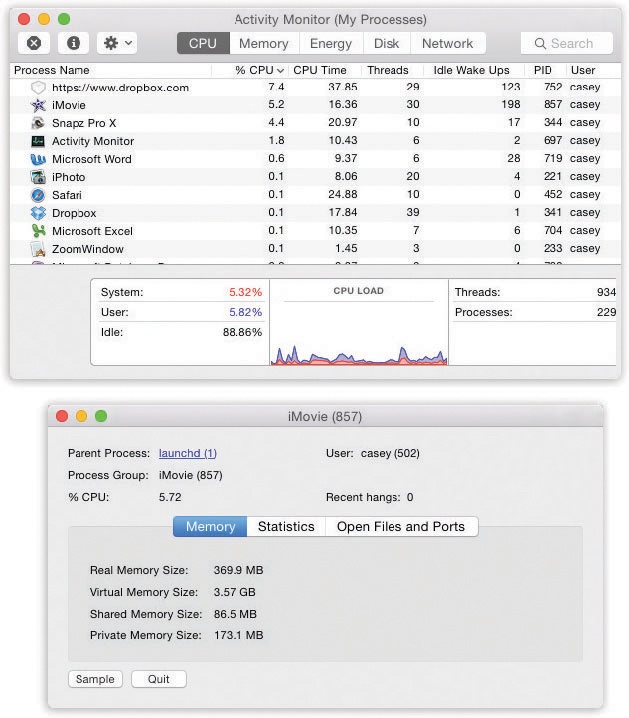

Since 2006, Macs have come with Intel chips inside, meaning that Macs and PCs use exactly the same memory, hard drives, monitors, mice, keyboards, networking protocols, and processors. With just a little bit of setup, therefore, your Mac can run Windows and Windows programs!

Think of all the potential switchers who are tempted by the Mac’s sleek looks, yet worry about leaving Windows behind entirely. Or the people who love Apple’s productivity programs but have jobs that rely on Microsoft Access, Outlook, or some other piece of Windows corporateware. Even true-blue Mac fans occasionally look longingly at some of the Windows-only games, websites, or movie download services they thought they’d never be able to use.

Today, there are two ways to run Windows on a Mac:

Restart it in Boot Camp. Boot Camp Assistant lets you restart your Mac into Windows.

At that point, it’s a full-blown Windows PC, with no trace of the Mac on the screen. It runs at 100 percent of the speed of a real PC, because it is one. Compatibility with Windows software is excellent. The only downsides: Your laptop battery life isn’t as good, and you have to restart the Mac to return to the familiar world of macOS.

Open Parallels or Fusion. The problem with Boot Camp is that every time you switch to or from Windows, you have to close down everything you were working on and restart the computer. You lose 2 or 3 minutes each way.

There is another way: an $80 utility called Parallels Desktop for Mac (www.parallels.com), or its rival, VMware Fusion (www.vmware.com). These two programs let you run Windows and macOS simultaneously; Windows hangs out in a window of its own, while the Mac is running macOS. You’re getting about 90 percent of Boot Camp’s Windows speed—which is plenty fast for everything but 3D games.

Having virtualization software on your Mac is a beautiful thing. You can be working on a design in iWork, duck into a Microsoft Access database (Windows only), look up an address, copy it, and paste it back into the Mac program.

You can even install Boot Camp and Parallels/Fusion. They coexist beautifully on a single Mac and can even use the same copy of Windows.

Both techniques require you to provide your own copy of Windows.

Since Boot Camp comes with the Mac, here’s a quick rundown.

To set up Boot Camp, you need the proper ingredients:

A copy of Windows 8 or later. It has to be the 64-bit version of Windows, and it has to be a full installation copy—not an upgrade version. And you need the ISO (disk image) of the Windows installer. (If you got Windows on a flash drive instead, then download the ISO from Microsoft and use the serial number that came with the flash drive.)

At least 55 gigs of free hard drive space on your built-in hard drive, or a second internal drive. Windows is not svelte, and you can’t install Windows on an external drive using Boot Camp.

The keyboard and mouse that came with your Mac. You can also use a generic USB keyboard and mouse; what you can’t use is a non-Apple cordless keyboard and mouse.

A USB flash drive, 16 GB or bigger. The Boot Camp installer may require this, depending on your Mac model.

Before you install, Apple strongly recommends that you back up your Mac, make sure it’s running the latest version of macOS Sierra, and acquire the latest version of Boot Camp (visit www.apple.com/support/bootcamp). If you’re using a laptop, plug it in for the surgery.

The step-by-steps for installation are long, and they vary according to your Mac model and whether you’re doing a fresh installation of Windows or upgrading to a newer version.

Fortunately, Apple has written out detailed instructions for you here: https://support.apple.com/en-us/HT201468.

When it’s all over, a crazy, disorienting sight presents itself: your Mac, running Windows. There’s no trace of the desktop, Dock, or  menu; it’s Windows now, baby.

menu; it’s Windows now, baby.

Walk through the Windows setup screens, creating an account, setting the time, and so on.

At this point, your Mac is actually a true Windows PC. You can install and run Windows programs, utilities, and even games; you’ll discover that they run really fast and well.

Most of your Mac’s features work in Windows: Ethernet and Wi-Fi networking, audio input and output, built-in camera, brightness and volume keys,  key, multitouch trackpad gestures, Bluetooth, and so on. You’ll also discover a new Control Panel icon and system-tray pop-up menu, as described later in this section.

key, multitouch trackpad gestures, Bluetooth, and so on. You’ll also discover a new Control Panel icon and system-tray pop-up menu, as described later in this section.

Note

Once you’re running Windows, you might wonder: How am I supposed to right-click? I don’t have a two-button mouse or two-button trackpad!

Yes, you do. See Notes on Right-Clicking for a panoply of options.

From now on, your main interaction with Boot Camp will be telling it what kind of computer you want your Mac to be today: a Windows machine or a Mac.

Presumably, though, you’ll prefer one operating system most of the time. Figure 12-44 (top and middle) shows how you specify your favorite.

Middle: To open the Boot Camp control panel, choose its name from its icon in the Windows system tray.

Bottom: This display, known as the Startup Manager, appears when you press Option during startup. It displays all the disk icons or partitions that contain bootable operating systems. Click the one you want, and then click the up-arrow button.

Figure 12-44. Top: To choose your preferred operating system—the one that always starts up unless you intervene—choose  →System Preferences. Click Startup Disk, and then click the icon for either macOS or Windows. Next, either click Restart (if you want to switch right now) or close the panel. The same controls are available when you’re running Windows.

→System Preferences. Click Startup Disk, and then click the icon for either macOS or Windows. Next, either click Restart (if you want to switch right now) or close the panel. The same controls are available when you’re running Windows.

Tip

If you’re running Windows and you just want to get back to macOS right now, you don’t have to bother with all the steps shown in Figure 12-44. Instead, click the Boot Camp system-tray icon and, from the shortcut menu, choose Restart in macOS.

From now on, each time you turn on the Mac, it starts up in the operating system you’ve selected.

If you ever need to switch—when you need Windows just for one quick job, for example—press the Option key as the Mac is starting up. You’ll see something like the icons shown in Figure 12-44 (bottom).

Now, if you really want to learn about Windows, you need a book like Windows 10: The Missing Manual.

But suggesting that you go buy another huge book would be tacky. So here’s just enough to get by.

First of all, a Mac keyboard and a Windows keyboard aren’t the same. Each has keys that would strike the other as extremely goofy. Still, you can trigger almost any keystroke that Windows is expecting by substituting special Apple keystrokes, like this:

Windows keystroke | Apple keystroke |

Ctrl+Alt+Delete | Control-Option-Delete |

Alt | Option |

Ctrl key | |

Backspace | Delete |

Delete (forward delete) | |

Enter | Return |

Num Lock | Clear (laptops: fn-F6) |

Print Screen (PrtScn) | F14 (laptops: fn-F11) |

Print Active Window (Alt+PrtScn) | Option-F14 (laptops: Option-fn-F11) |

The keyboard shortcuts in your programs are mostly the same as on the Mac, but you have to substitute the  key for the Ctrl key. So in Windows programs on the Mac, Copy, Save, and Print are now

key for the Ctrl key. So in Windows programs on the Mac, Copy, Save, and Print are now  -C,

-C,  -S, and

-S, and  -P.

-P.

Tip

You know that awesome two-finger scrolling trick on Mac laptops? It works when you’re running Windows, too.

If you really want to understand how your Mac keyboard corresponds to a PC keyboard, don’t miss Apple’s thrilling document on the subject at http://support.apple.com/kb/HT1167.

When you’ve started up in one operating system, it’s easy to access documents that “belong” to the other one. For example:

When you’re running macOS, you can get to the documents you created while you were running Windows, which is a huge convenience. Just double-click the Windows disk icon (called NO NAME or Untitled), and then navigate to the Documents and Settings→[your account name]→My Documents (or Desktop).

You can only copy files to the Mac side, or open them without the ability to edit them.

When you’re running Windows, you can get to your Mac documents, too. Click Start→Computer. In the resulting window, you’ll see an icon representing your Mac’s hard drive partition. Open it up.

You can see and open these files. But if you want to edit them, you have to copy them to your Windows world first—onto the desktop, for example, or into a folder. (The Mac partition is “read-only” in this way, Apple says, to avoid the possibility that your Mac stuff could get contaminated by Windows viruses.)

Tip

If you did want to edit Mac files from within Windows, one solution is to use a disk that both macOS and Windows “see,” and keep your shared files on that. A flash drive works beautifully for this. So does a shared drive on the network, or an Internet-based disk like Dropbox, Microsoft’s OneDrive, or even Apple’s iCloud Drive (Tip). You can make each of these show up in both Mac and Windows.

If you use ColorSync, then you probably know already that this utility is for people in the high-end color printing business. Its tabs include these two:

Profile First Aid. This tab performs a fairly esoteric task: repairing ColorSync profiles that may be “broken” because they don’t strictly conform to the ICC profile specifications. (International Color Consortium profiles are part of Apple’s ColorSync color management system.) If a profile for your specific monitor or printer doesn’t appear in the Profiles tab of this program when it should, then Profile First Aid is the tool you need to fix it.

Profiles. This tab lets you review all the ColorSync profiles installed on your system. The area on the right side of the window displays information about each ColorSync profile you select from the list on the left.

The other tabs are described in ColorSync.

Console is a viewer for all of macOS’s logs—the behind-the-scenes, internal Unix record of your Mac’s activities.

Opening the Console log is a bit like stepping into an operating room during a complex surgery: You’re exposed to stuff the average person just isn’t supposed to see. (Typical Console entries: “kCGErrorCannotComplete” or “doGetDisplayTransferByTable.”) You can adjust the font and word wrapping using Console’s Font menu, but the truth is that the phrase “CGXGetWindowType: Invalid window -1” looks ugly in just about any font!

Console isn’t useless, however. These messages can be of significant value to programmers who are debugging software or troubleshooting a messy problem, or, occasionally, to someone you’ve called for tech support.

For example, your crash logs are detailed technical descriptions of what went wrong when various programs crashed, and what was stored in memory at the time.

Unfortunately, there’s not much plain English here to help you understand the crash, or how to avoid it in the future. Most of it runs along the lines of “Exception: EXC_BAD_ACCESS (0x0001); Codes: KERN_INVALID_ADDRESS (0x0001) at 0x2f6b657d.”

DigitalColor Meter can grab the exact color value of any pixel on your screen, which can be helpful when matching colors in web page construction or other design work. After launching the DigitalColor Meter, just point anywhere on your screen. A magnified view appears in the meter window, and the RGB (red-green-blue) color value of the pixels appears in the meter window.

Here are some tips for using the DigitalColor Meter to capture color information from your screen:

To home in on the exact pixel (and color) you want to measure, drag the Aperture Size slider to the smallest size: 1 pixel.

Press

-X (View→Lock X) to freeze your cursor at its current horizontal position; you can now move it only horizontally. Or press

-X (View→Lock X) to freeze your cursor at its current horizontal position; you can now move it only horizontally. Or press  -Y (View→Lock Y) to freeze your cursor at its current vertical position. You can also lock the cursor in both directions. (Press the keystroke again to unlock.) The idea is to make it easier for you to snap to exactly the pixel you want.

-Y (View→Lock Y) to freeze your cursor at its current vertical position. You can also lock the cursor in both directions. (Press the keystroke again to unlock.) The idea is to make it easier for you to snap to exactly the pixel you want.When the Aperture Size slider is set to view more than one pixel, DigitalColor Meter measures the average value of the pixels being examined.

This important program has two key functions:

It serves as macOS’s own disk-repair program: a powerful administration tool that lets you repair, erase, format, and partition disks. You’ll probably use Disk Utility most often for its First Aid feature, which solves a number of weird little Mac glitches. But it’s also worth keeping in mind in case you ever find yourself facing a serious disk problem.

Disk Utility also creates and manages disk images, electronic versions of disks or folders that you can exchange electronically with other people.

Note

In 2015, Apple put Disk Utility on a bit of a diet. A few features are no longer part of the program, including burning a CD from a disk image and formatting RAID drives. Most shocking of all, there’s no longer a Repair Permissions button, a powerful troubleshooting tool that used to be one of Disk Utility’s most important functions; it could fix all kinds of weird Mac glitches. Apple says macOS now checks and repairs disk permissions automatically every time you install a system update.

The following discussion tackles the program’s two personalities one at a time.

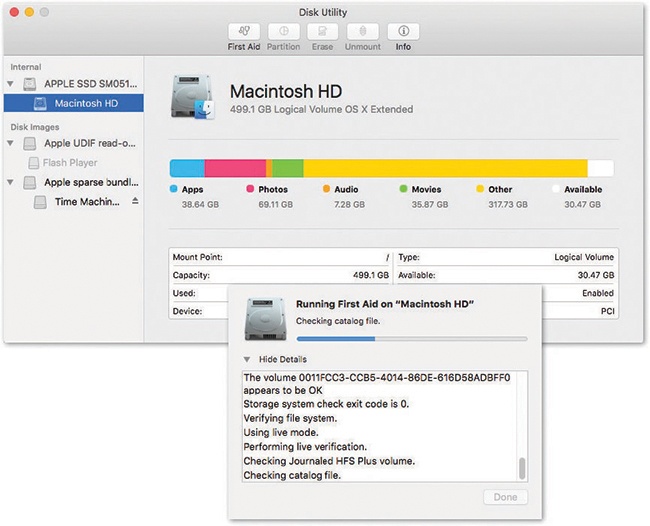

When you first open Disk Utility, you see, at a glance, what kinds of files are eating up your disk space (see Figure 12-45).

When you click the name of your hard drive’s mechanism, like “500 GB Hitachi iC25N0…” (not the “Macintosh HD” volume label below it), you see five buttons, one for each of the main Disk Utility functions:

Figure 12-45. Top: The left Disk Utility panel lists your hard drive and any other disks in or attached to your Mac at the moment.

First Aid. This is the disk-repair part of Disk Utility, and it does a terrific job at fixing many disk problems. When you’re troubleshooting, Disk Utility should be your first resort.

To use it, click the icon of a disk and then click First Aid. After asking for confirmation (click Run), this function scours every single file on your drive, checking for corruption, flakiness, or trouble spots on the disk (Figure 12-45, bottom).

If Disk First Aid reports that it’s unable to fix the problem, then it’s time to invest in a program like DiskWarrior (www.alsoft.com).

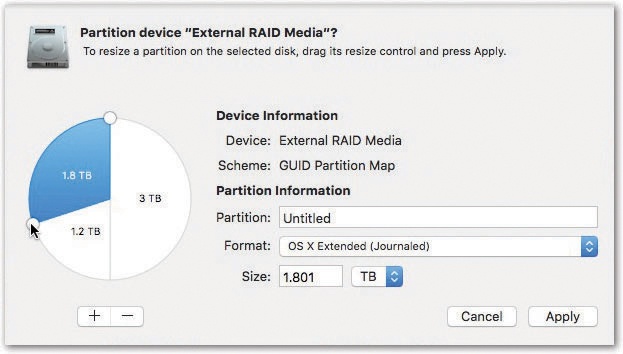

Partition. With the Partition tools, you can erase a hard drive in such a way that you subdivide its surface. Each chunk will be represented on your screen by another hard drive icon (Figure 12-46).

There are some very good reasons not to partition a drive these days: A partitioned hard drive is more difficult to resurrect after a serious crash, requires more navigation when you want to open a particular file, and offers no speed or safety benefits.

On the other hand, there’s one very good reason to do it: Partitioning is the only way to use Boot Camp, described starting in Bluetooth File Exchange. When you’re using Boot Camp, your Mac is a Mac when running off of one partition, and a Windows PC when starting up from another one. (But you don’t use Disk Utility in that case; you use Boot Camp Assistant.)

Erase. Select a disk, choose a format—always macOS Extended (Journaled), unless you’re formatting a disk for use on a Windows PC—give it a name, and then click Erase to wipe a disk clean.

Tip

Click Security Options to view a slider. It can strike four spots on the spectrum from the speed of the disk erasing to the security of it. At the far-left position, macOS erases the drive quickly, but a recovery app could recover the files. At the more secure settings, macOS performs various additional time-consuming scrubbing tasks, writing over your old files with randomized gibberish, making file recovery impossible. Something to remember if you sell your Mac!

Unmount. This button ejects whatever disk you’ve selected in the left-side list.

Info. Click to view a little table of super-technical details about the selected drive.

Disk images are very cool. Each is a single icon that behaves precisely like an actual disk—a flash drive or hard drive, for example—but can be distributed electronically. For example, a lot of macOS apps arrive from your web download in disk-image form.

Disk images are popular for software distribution for a simple reason: Each image file precisely duplicates the original master disk, complete with all the necessary files in all the right places. When a software company sends you a disk image, it ensures that you’ll install the software from a disk that exactly matches the master disk.

As a handy bonus, you can password-protect a disk image, which is the closest macOS comes to offering the ability to password-protect an individual folder.

It’s important to understand the difference between a disk-image file and the mounted disk (the one that appears when you double-click the disk image). If you flip back to Downloading Compressed Files and consult Figure 6-2, this distinction should be clear.

Tip

After you double-click a disk image, click Skip in the verification box that appears. If something truly got scrambled during the download, you’ll know about it right away—your file won’t decompress correctly, or it’ll display the wrong icon, for example.

You can create disk images, too. Doing so can be very handy in situations like these:

You want to create a backup of an important CD. By turning it into a disk-image file on your hard drive, you’ll always have a safety copy, ready to burn back onto a new CD. (This is an essential practice for educational CDs that kids will be handling soon after eating peanut butter and jelly.)

You want to replicate your entire hard drive—complete with all its files, programs, folder setups, and so on—onto a new, bigger hard drive (or a new, better Mac), using the Restore feature described earlier.

You want to back up your entire hard drive, or maybe just a certain chunk of it, onto an iPod or another disk. (Again, you can later use the Restore function.)

You want to send somebody else a copy of a disk via the Internet. You simply create a disk image, and then send that—preferably in compressed form.

Here’s how to make a disk image.

To image-ize a disk or partition. Click the name of the disk in the list, where you see your currently available disks. (The topmost item is the name of your drive, like “484.0 MB MATSHITA DVD-R” for a DVD drive or “74.5 GB Hitachi” for a hard drive. Beneath that entry, you generally see the name of the actual partition, like “Macintosh HD,” or the CD’s name as it appears on the screen.)

Then choose File→New Image→Disk Image from [the disk or partition’s name].

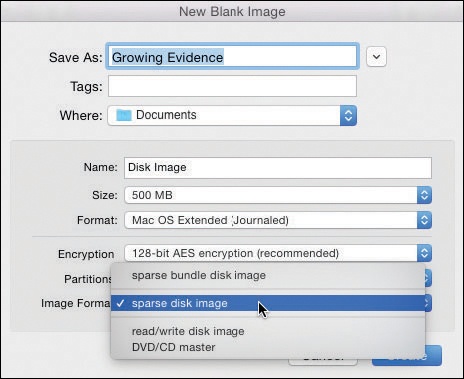

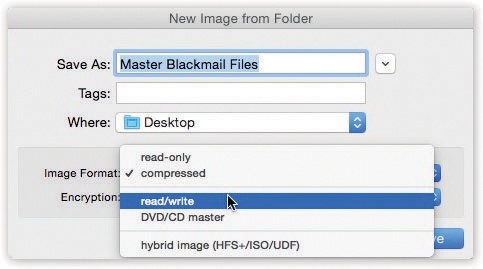

To image-ize a folder. Choose File→New Image→Disk Image from Folder. In the Open dialog box, click the folder you want, and then click Image. Either way, the next dialog box (Figure 12-47) offers some fascinating options.

Image Format. If you choose “read/write,” your disk image file, when double-clicked, turns into a superb imitation of a hard drive. You can drag files and folders onto it, drag them off of it, change icons’ names on it, and so on.

If you choose “read-only,” however, then the result behaves more like a CD. You can copy things off of it but not make any changes to it.

The “compressed” option is best if you intend to send the resulting file by email, post it for web download, or preserve the disk image on some backup disk for a rainy day. It takes a little longer to create a simulated disk when you double-click the disk image file, but it takes up a lot less disk space than an uncompressed version.

Finally, choose “DVD/CD master” if you’re copying a CD or a DVD. The resulting file is a perfect mirror of the original disc, ready for copying onto a blank CD or DVD when the time comes.

Encryption. Here’s an easy way to lock private files away into a vault that nobody else can open. If you choose one of these two AES encryption options (choose AES-128, if you value your time), you’ll be asked to assign a password to your new image file. Nobody can open it without the password—not even you. On the other hand, if you save it into your Keychain (The Keychain), then it’s not such a disaster if you forget the password.

Save As. Choose a name and location for your new image file. The name you choose here doesn’t need to match the original disk or folder name.

When you click Save (or press Return), if you opted to create an encrypted image, you’re asked to make up a password at this point.

Otherwise, Disk Utility now creates the image and then mounts it—that is, turns the image file into a simulated, yet fully functional, disk icon on your desktop.

When you’re finished working with the disk, eject it as you would any disk (right-click or two-finger click it and choose Eject, for example). Hang on to the .dmg disk-image file itself, however. This is the file you’ll need to double-click if you ever want to recreate your “simulated disk.”

Grab takes pictures of your Mac’s screen, for use when you’re writing up instructions, illustrating a computer book, or collecting proof of some secret screen you found buried in a game. You can take pictures of the entire screen (press  -Z, which for once in its life does not mean Undo) or capture only the contents of a rectangular selection (press Shift-

-Z, which for once in its life does not mean Undo) or capture only the contents of a rectangular selection (press Shift- -A). When you’re finished, Grab displays your snapshot in a new window, which you can print, close without saving, or save as a TIFF file, ready for emailing or inserting into a manuscript.

-A). When you’re finished, Grab displays your snapshot in a new window, which you can print, close without saving, or save as a TIFF file, ready for emailing or inserting into a manuscript.

Now, as experienced Mac enthusiasts already know, the Mac operating system has long had its own built-in shortcuts for capturing screenshots: Press Shift- -3 to take a picture of the whole screen, and Shift-

-3 to take a picture of the whole screen, and Shift- -4 to capture a rectangular selection. (See Screen-Capture Keystrokes for all the details.)

-4 to capture a rectangular selection. (See Screen-Capture Keystrokes for all the details.)

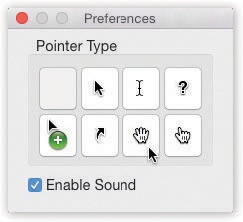

Figure 12-48. Unlike the Shift- -3 or Shift-

-3 or Shift- -4 keystrokes, Grab lets you include the pointer/cursor in the picture—or hide it. Choose Grab→Preferences and pick one of the pointer styles, or choose to keep the pointer hidden by activating the blank button in the upper-left corner.

-4 keystrokes, Grab lets you include the pointer/cursor in the picture—or hide it. Choose Grab→Preferences and pick one of the pointer styles, or choose to keep the pointer hidden by activating the blank button in the upper-left corner.

Tip

Don’t forget that you can choose different, easier-to-remember keyboard shortcuts for these functions, if you like. Just open System Preferences→Keyboard→Keyboard Shortcuts, click Screen Shots, click where it now says Shift- -3 (or whatever), and then press the new key combo.

-3 (or whatever), and then press the new key combo.

So why use Grab instead? In many cases, you shouldn’t. The Shift- -3 and Shift-

-3 and Shift- -4 shortcuts work like a dream. But there are some cases when it might make more sense to opt for Grab. Here are two:

-4 shortcuts work like a dream. But there are some cases when it might make more sense to opt for Grab. Here are two:

Grab can make a timed screen capture (choose Capture→Timed Screen, or press Shift-

-Z), which lets you enjoy a 10-second delay before the screenshot is actually taken. After you click the Start Timer button, you have an opportunity to activate windows, pull down menus, drag items around, and otherwise set up the shot before Grab shoots the picture.

-Z), which lets you enjoy a 10-second delay before the screenshot is actually taken. After you click the Start Timer button, you have an opportunity to activate windows, pull down menus, drag items around, and otherwise set up the shot before Grab shoots the picture.With Grab, you have the option of including the cursor in the picture, which is extremely useful when you’re showing a menu being pulled down or a button being clicked. (MacOS’s screenshot keystrokes, by contrast, always eliminate the pointer.) Use the technique described in Figure 12-48 to add the pointer style of your choice to a Grab screenshot.

Tip

If you’re really going to write a book or manual about macOS, the program you need is Snapz Pro X; a trial version is available from this book’s “Missing CD” page at www.missingmanuals.com. It offers far more flexibility.

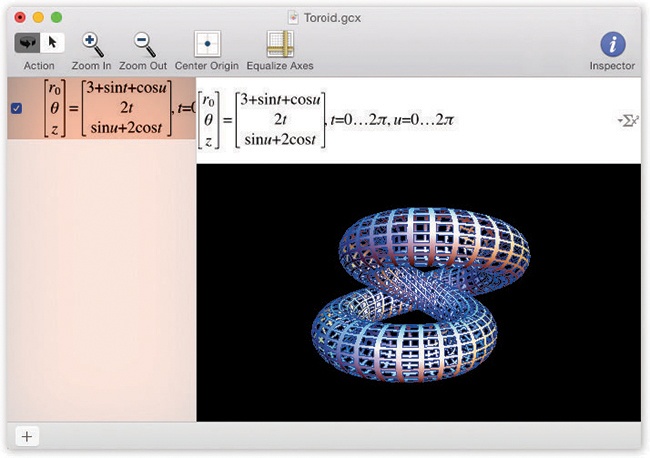

This little unsung app is an amazing piece of work. It lets you create 2D or 3D graphs of staggering beauty and complexity.

When you first open Grapher, you’re asked to choose what kind of virtual “graph paper” you want: two-dimensional (standard, polar, logarithmic) or three-dimensional (cubic, spherical, cylindrical). Click a name to see a preview; when you’re happy with the selection, click Open.

Now the main Grapher window appears (Figure 12-49). Do yourself a favor. Spend a few wow-inducing minutes choosing canned equations from the Examples menu and watching how Grapher whips up gorgeous, colorful, sometimes animated graphs on the fly.

When you’re ready to plug in an equation of your own, type it into the text box at the top of the window. If you’re not such a math hotshot, or you’re not sure of the equation format, work from the canned equations and mathematical building blocks that appear when you choose Equation→New Equation from Template or Window→Show Equation Palette (a floating window containing a huge selection of math symbols and constants).

Tip

If you don’t know the keystroke that produces a mathematical symbol like π or θ, you can just type pi or theta. Grapher replaces it with the correct symbol automatically.

Figure 12-49. In general, you type equations into Grapher just as you would on paper (like z=2xy). If in doubt, check the online help, which offers enough hints on functions, constants, differential equations, series, and periodic equations to keep the A Beautiful Mind guy busy for days.

Once the graph is up on the screen, you can tailor it like this:

To move a 2D graph in the window, choose View→Move Tool and then drag; to move a 3D graph,

-drag it.

-drag it.To rotate a 3D graph, drag in any direction. If you add the Option key, you flip the graph around on one axis.

To change the colors, line thicknesses, 3D “walls,” and other graphic elements, click the

button (or choose Window→Show Inspector) to open the formatting palette. The controls you find here vary by graph type, but rest assured that Grapher can accommodate your every visual whim.

button (or choose Window→Show Inspector) to open the formatting palette. The controls you find here vary by graph type, but rest assured that Grapher can accommodate your every visual whim.To change the fonts and sizes, choose Grapher→Preferences. On the Equations panel, the four sliders let you specify the relative sizes of the text elements. If you click the sample equation, the Fonts panel appears, so you can go to town fiddling with the type.

Add your own captions, arrows, ovals, or rectangles using the Object menu.

When it’s all over, you can preserve your masterpiece using any of these techniques:

Export a graphic by choosing File→Export.

Copy an equation to the Clipboard by right-clicking or two-finger clicking it and choosing Copy As→TIFF (or EPS, or whatever) from the shortcut menu. Now you can paste it into another program.

Export an animated graph by choosing Equation→Create Animation. The resulting dialog box lets you specify how long you want the movie to last (and a lot of other parameters).

Finally, click Create Animation. After a moment, the finished movie appears. If you like it, choose File→Save As to preserve it on your hard drive for future generations.

Keychain Access memorizes and stores all your secret information—passwords for network access, file servers, FTP sites, web pages, and other secure items. For instructions on using Keychain Access, see The Keychain.

This little cutie automates the transfer of all your stuff from another Mac or even a Windows PC, to your current Mac: your Home folder, network settings, programs, and more. This comes in extremely handy when you buy a newer, better Mac—or when you need Time Machine to recover an entire dead Mac’s worth of data. (It can also copy everything over from a secondary hard drive or partition.) The instructions on the screen guide you through the process (see Appendix A).

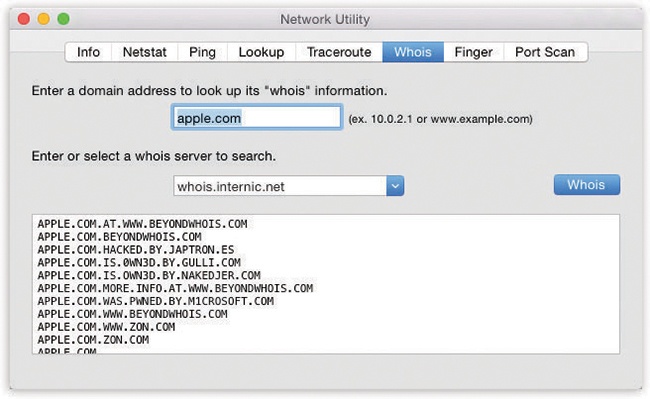

Network Utility isn’t actually in your Utilities folder. It now lives in a deeply nested folder where you’d never think to look (System→Library→CoreServices→Applications). But you can quickly find and open it with a Spotlight search, or from within System Information, described below (choose Window→Network Utility).

In any case, it gathers information about websites and network citizens. It offers a suite of standard Internet tools like netstat, ping, traceroute, DNS lookup, and whois—advanced tools, to be sure, but ones that even Mac novices may be asked to fire up when calling a technician for Internet help.

Otherwise, you probably won’t need to use Network Utility to get your work done. However, Network Utility can be useful when you’re doing Internet detective work:

Use ping to enter an address (either a web address like www.google.com or an IP address like 192.168.1.110), and then “ping” (send out a “sonar” signal to) the server to see how long it takes for it to respond to your request. Network Utility reports the response time in milliseconds—a useful test when you’re trying to see if a remote server (a website, for example) is up and running. (The time it takes for the ping to report back to you also tells you how good your connection to it is.)

Whois (“who is”) can gather an amazing amount of information about the owners of any particular domain (such as apple.com)—including name and address info, telephone numbers, and administrative contacts. It uses the technique shown in Figure 12-50.

Figure 12-50. The whois tool is a powerful part of Network Utility. First enter a domain that you want information about, and then choose a whois server (you might try www.whois.networksolutions.com). When you click the Whois button, you get a surprisingly revealing report about the owner of the domain, including phone numbers and contact names.

Traceroute lets you track how many “hops” are required for your Mac to communicate with a certain server (an IP address or web address). You’ll see that your request actually jumps from one trunk of the Internet to another, from router to router, as it makes its way to its destination. You’ll learn that a message sometimes crisscrosses the entire country before it arrives. You can also see how long each leg of the journey took, in milliseconds.

This little program, formerly called AppleScript Editor, is where you can type up your own AppleScripts. You can read about these programmery software robots in the free online appendix to this chapter, “Automator & AppleScript.” It’s available on this book’s “Missing CD” page at www.missingmanuals.com.

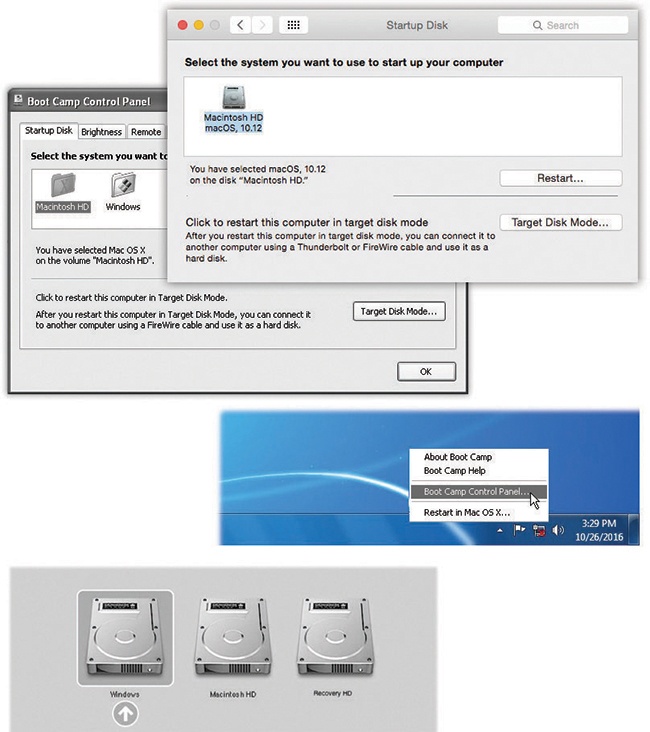

System Information (formerly called System Profiler) is a great tool for learning exactly what’s installed on your Mac and what’s not—in terms of both hardware and software. The people who answer the phones on Apple’s tech-support line are particularly fond of System Profiler, since the detailed information it reports can be very useful for troubleshooting nasty problems.

There are actually two versions of System Information: a quick, easy snapshot and a ridiculously detailed version:

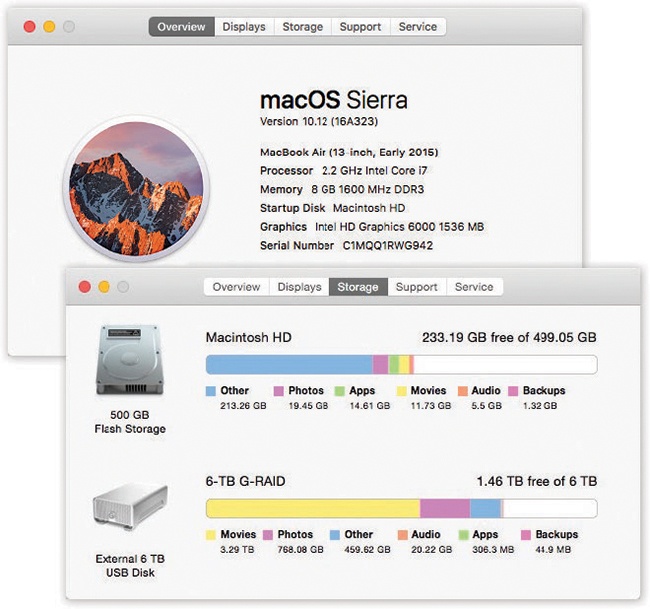

Snapshot. Choose

→About This Mac. You get a concise, attractive summary info screen that reveals your macOS version, your Mac’s memory amount, its serial number, what processor it has inside, and so on (Figure 12-51, top).

→About This Mac. You get a concise, attractive summary info screen that reveals your macOS version, your Mac’s memory amount, its serial number, what processor it has inside, and so on (Figure 12-51, top).Tip

If you click your macOS version number in the About box, you get to see its build number—something primarily of interest to programmers and people who beta-test macOS.

Figure 12-51. This dialog box gives you a plain-English display of the Mac details you probably care the most about: memory, screen, storage, serial number, macOS version, and so on. (Click the tabs across the top for more details.) To proceed from here to the full System Information program, click System Report.

The tabs across the top reveal similarly precise details about your Displays and Storage. The Support tab offers links to various sources of online help, and the Service tab reveals your options for getting the Mac fixed.

Ridiculously detailed. Open Applications→Utilities; double-click System Information. (You can also open the System Information program from inside the About This Mac dialog box shown in Figure 12-51; just click System Report.)

When System Information opens, it reports information about your Mac in a list down the left side (Figure 12-52). The details fall into these categories:

Hardware. Click this word to see precisely which model Mac you have, what kind of chip is inside (and how many), how much memory it has, and its serial number.

If you expand the flippy triangle, you get to see details about which Memory slots are filled and the size of the memory module in each slot; what kind of Disc Burning your Mac can do (DVD-R, DVD+R, and so on); what PCI Cards are installed in your expansion slots; what Graphics/Displays circuitry you have (graphics card and monitor); what’s attached to your SATA bus (internal drives, like your hard drive); what’s connected to your Thunderbolt, USB, and FireWire chains, if anything; and much more.

Network details what Wi-Fi components you have, what Internet connection Locations you’ve established, and so on.

Software shows which version of macOS you have and what your computer’s name is, as far as the network is concerned (“Pat’s Computer,” for example).

The Applications list documents every program on your system, with version information. It’s useful for spotting duplicate copies of programs.

Similar information shows up in the Extensions panel. Extensions are the drivers for the Mac’s various components, which sit in the System→Library→Extensions folder. Whatever is in that folder is what you see listed in this panel. Other categories include self-explanatory lists like Fonts, Preference Panes, and Startup Items.

Finally, the Logs panel reveals your Mac’s secret diary: a record of the traumatic events that it experiences from day to day. (Many of these are the same as those revealed by the Console utility; see Console.)

To create a handsomely formatted report that you can print or save, choose File→Export as Text, and then choose Rich Text Format from the File Format pop-up menu. Note, however, that the resulting report can be well over 500 pages long. In many cases, you’re better off simply making a screenshot of the relevant Profiler screen, as described in Screen-Capture Keystrokes, or saving the thing as a PDF file.

Underneath its shiny skin, macOS is actually Unix, one of the oldest and most respected operating systems in use today. But you’d never know it by looking; Unix is a world without icons, menus, or dialog boxes. You operate it by typing out memorized commands at a special prompt, called the command line. The mouse is almost useless here.

Wait a minute—Apple’s ultramodern operating system, with a command line? What’s going on? Actually, the command line never went away. At universities and corporations worldwide, professional computer nerds still value the efficiency of pounding away at the little C: or $ prompts.

You never have to use macOS’s command line. In fact, Apple has swept it pretty far under the rug. There are, however, some tasks you can perform only at the command line.

Terminal is your keyhole into macOS’s Unix innards. There’s a whole chapter on it waiting for you on this book’s “Missing CD” page at www.missingmanuals.com.

For details on this screen-reader software, see Figure 10-4.