Chapter 3

Kinematics of Robotic Systems

In this chapter, the general principles of kinematics in Chapter are applied to robotics to help model their geometry and enable the construction of dynamic models. Applications of these principles are diverse and include the study of industrial robotic manipulators, the design and analysis of ground vehicles, the creation of models of flight vehicles, and the development of models of space vehicles. This chapter introduces the special structure that the principles of kinematics can take in the study of robotic systems that have the form of a kinematic chain or are constructed from assemblies of kinematic chains that do not form closed loops. Robotic systems having a tree topology are an example of the latter class. Upon the completion of this chapter, the student should be able to:

- Define and use homogeneous transformations to represent rigid body motion.

- Define and use homogeneous coordinates to represent position vectors.

- Define the assumptions underlying the Denavit–Hartenberg convention.

- Use the Denavit–Hartenberg convention to model a kinematic chain.

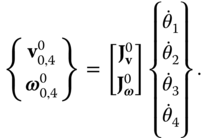

- Derive the Jacobian matrix relating derivatives of the generalized coordinates to the velocity and angular velocity.

- Derive and use the recursive

formulation of kinematics.

3.1 Homogeneous Transformations and Rigid Motion

Sections 2.1 and 2.4 in Chapter discuss the fundamental properties ofrotation matrices and their use in change of basis formulae. In applications to robotics, however, information about both the rotation and the translation of coordinate systems is often required. This section will show thathomogeneous transformations are a succinct way of describing theserigid body motions.

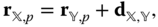

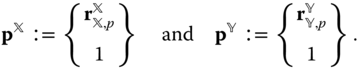

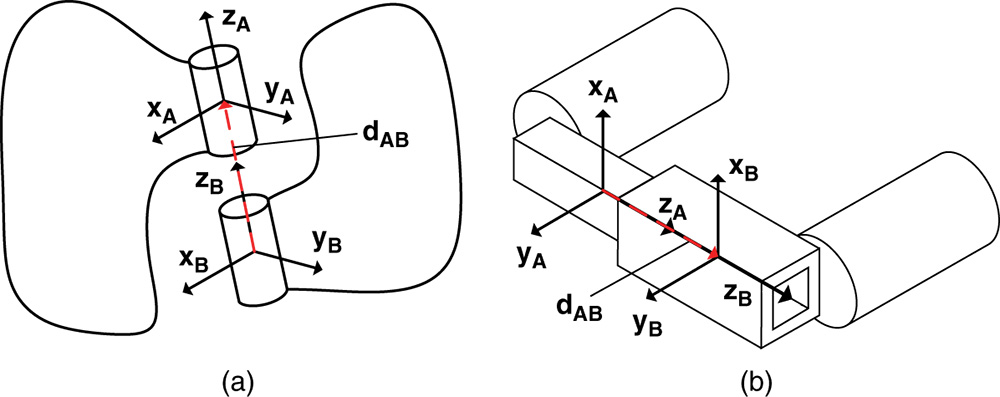

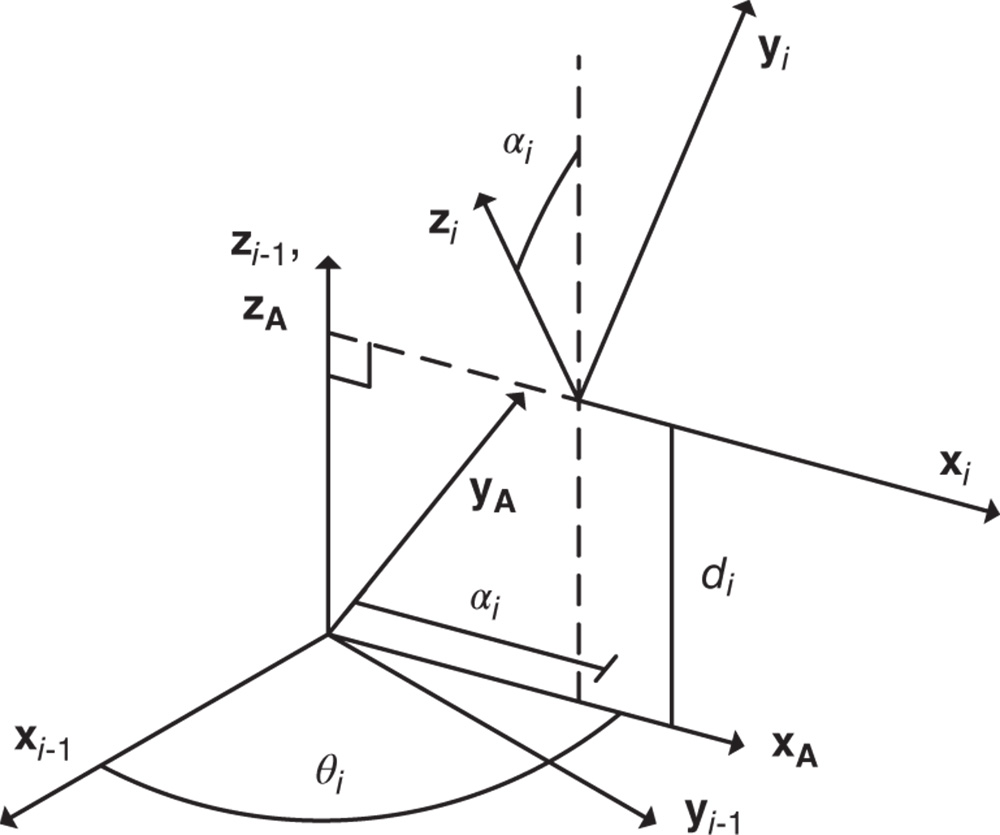

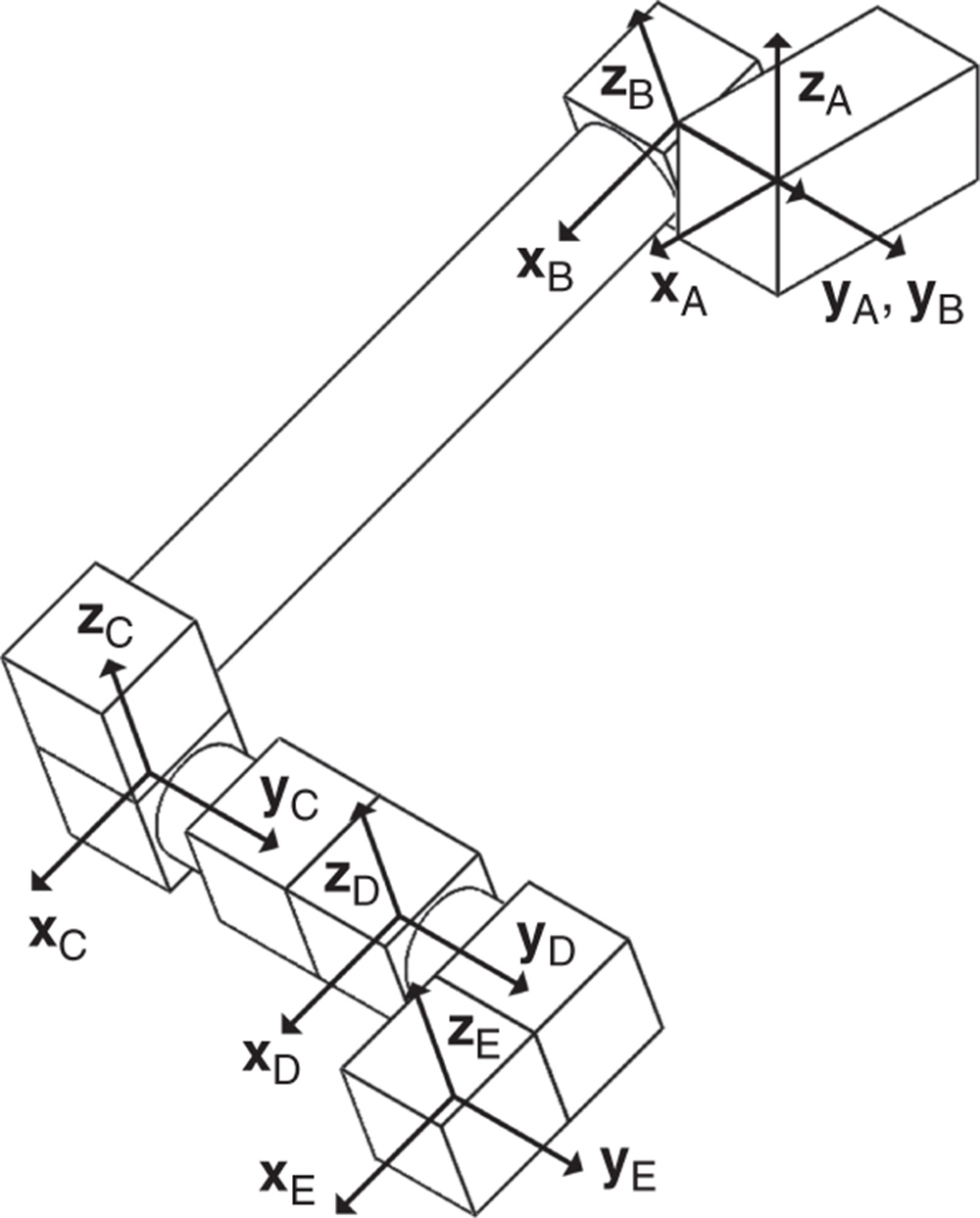

Suppose there are two bodies with body fixed frames  and

and  , respectively, as shown in Figure 3.1. The location of a generic point

, respectively, as shown in Figure 3.1. The location of a generic point  with respect to the two different frames

with respect to the two different frames  and

and  is defined through the vector identity

is defined through the vector identity

which is defined in Figure 3.1. In this equation  is the position of the point

is the position of the point  relative to the frame

relative to the frame  , while

, while  is the position of the point

is the position of the point  with respect to the frame

with respect to the frame  . The vector

. The vector  is the relative offset between the origin of the

is the relative offset between the origin of the  frame and the

frame and the  frame.

frame.

Figure 3.1 Two rigid bodies, body fixed frames, and position vectors.

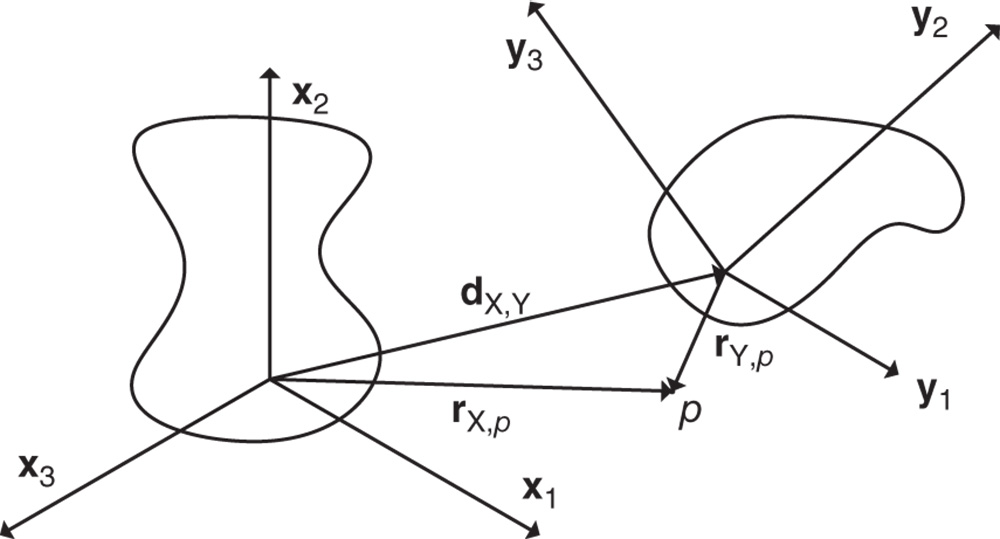

No particular basis is implied in Equation 3.1: it is an equation in terms of vectors. If the vectors that appear in Equation 3.1 are expressed in terms of coordinates relative to their respective body fixed frames,

where  is the rotation matrix relating the frames. This identity follows from the fundamental definitions and properties of rotation matrices.

is the rotation matrix relating the frames. This identity follows from the fundamental definitions and properties of rotation matrices.

Note that the position  is expressed in terms of the

is expressed in terms of the  basis, and the position

basis, and the position  is expressed in terms of the

is expressed in terms of the  basis. This convention is common in robotics and is the foundation of many of the approaches in this chapter that are tailored to the study of robotics. It is desirable to relate the coordinate representations

basis. This convention is common in robotics and is the foundation of many of the approaches in this chapter that are tailored to the study of robotics. It is desirable to relate the coordinate representations  and

and  , so the

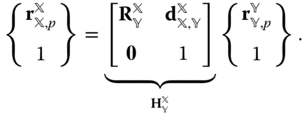

, so the  homogeneous transformation matrix

homogeneous transformation matrix  is introduced in Equation (3.3) to cast Equation (3.2) in the form of a matrix equation.

is introduced in Equation (3.3) to cast Equation (3.2) in the form of a matrix equation.

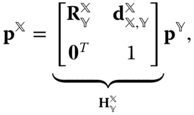

In contrast to the techniques associated with  rotation matrices and the change of basis formulae introduced in Chapter , the homogeneous transformation operates on 4‐tuples ofhomogeneous coordinates

rotation matrices and the change of basis formulae introduced in Chapter , the homogeneous transformation operates on 4‐tuples ofhomogeneous coordinates

and

and  of the point

of the point  , such that

, such that

It is a standard convention in robotics literature to suppress all the subscripts in the definition of the homogeneous coordinates. However, it is important to keep in mind that the homogeneous coordinates are implicitly associated with a specific choice of both the origin of position vectors and basis. In this text, although the notation is cumbersome, the subscripts and superscripts will be retained to make explicit the origins and bases used.

The final form of the transformation that represents a rigid body motion can be expressed as

or more succinctly as,

The notation in Equation (3.4) closely resembles the matrix equation that relates the coordinates  and

and  of a vector

of a vector  under a rotation of basis,

under a rotation of basis,

While notation has been chosen such that Equations (3.4) and (3.5) have the same appearance, there is a substantial difference between the matrices  and

and  . A homogeneous transformation is not an orthogonal transformation. That is, in general,

. A homogeneous transformation is not an orthogonal transformation. That is, in general,  . Instead, the inverse of a homogeneous transformation is explicitly derived in Theorem 3.1.

. Instead, the inverse of a homogeneous transformation is explicitly derived in Theorem 3.1.

The following example shows how the use of homogeneous transformations and homogeneous coordinates can facilitate the study of typical robotic subsystems.

3.2 Ideal Joints

Before introducing some specific conventions and algorithms for studying the kinematics of robotic systems, a few preliminaries are required that go beyond the fundamental theorems of kinematics introduced in Chapter . The specialized principles of kinematics and dynamics employed for robotic systems fall within the broader study ofmultibody dynamics. Multibody dynamics is the study of the dynamics of mechanical systems that are comprised of several interconnected bodies. The most common assumption in classical multibody dynamics is that the bodies are rigid, but generalizations that consider flexible bodies have also been developed. An account of the fundamentals of multibody dynamics can be found in [45]. In this book, the bodies under consideration are assumed to be rigid.

Just as models for the individual bodies can vary in their complexity, so too can the nature of the mathematical constraints that relate their motion. Later in Chapter , a common, general form for constraints on permissible motions will be defined. This chapter will focus on specific constraints induced byideal joints (e.g., Figure 1.6 from Chapter ) that connect two rigid bodies.

Suppose there are two rigid bodies denoted  and

and  undergoing independent motions. From prior study of rigid motions, it is known that for the most general motions of the rigid bodies

undergoing independent motions. From prior study of rigid motions, it is known that for the most general motions of the rigid bodies  and

and  , three translation variables and three angles are required to define the location and orientation of each body. 12 variables in total are required to describe the kinematics of the two independent bodies. However, when considering robotic systems, bodies will be interconnected. When the two bodies are interconnected, the number of variables required to describe the location and orientation of both bodies is reduced in number. For example, suppose the bodies are “welded” together. If the position and orientation of one of the bodies is prescribed as a function of time, the location and orientation of the other body is also known as a function of time. In this case, only six variables that depend on time are required to describe the constrained motion of the system that consists of two rigid bodies.

, three translation variables and three angles are required to define the location and orientation of each body. 12 variables in total are required to describe the kinematics of the two independent bodies. However, when considering robotic systems, bodies will be interconnected. When the two bodies are interconnected, the number of variables required to describe the location and orientation of both bodies is reduced in number. For example, suppose the bodies are “welded” together. If the position and orientation of one of the bodies is prescribed as a function of time, the location and orientation of the other body is also known as a function of time. In this case, only six variables that depend on time are required to describe the constrained motion of the system that consists of two rigid bodies.

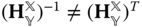

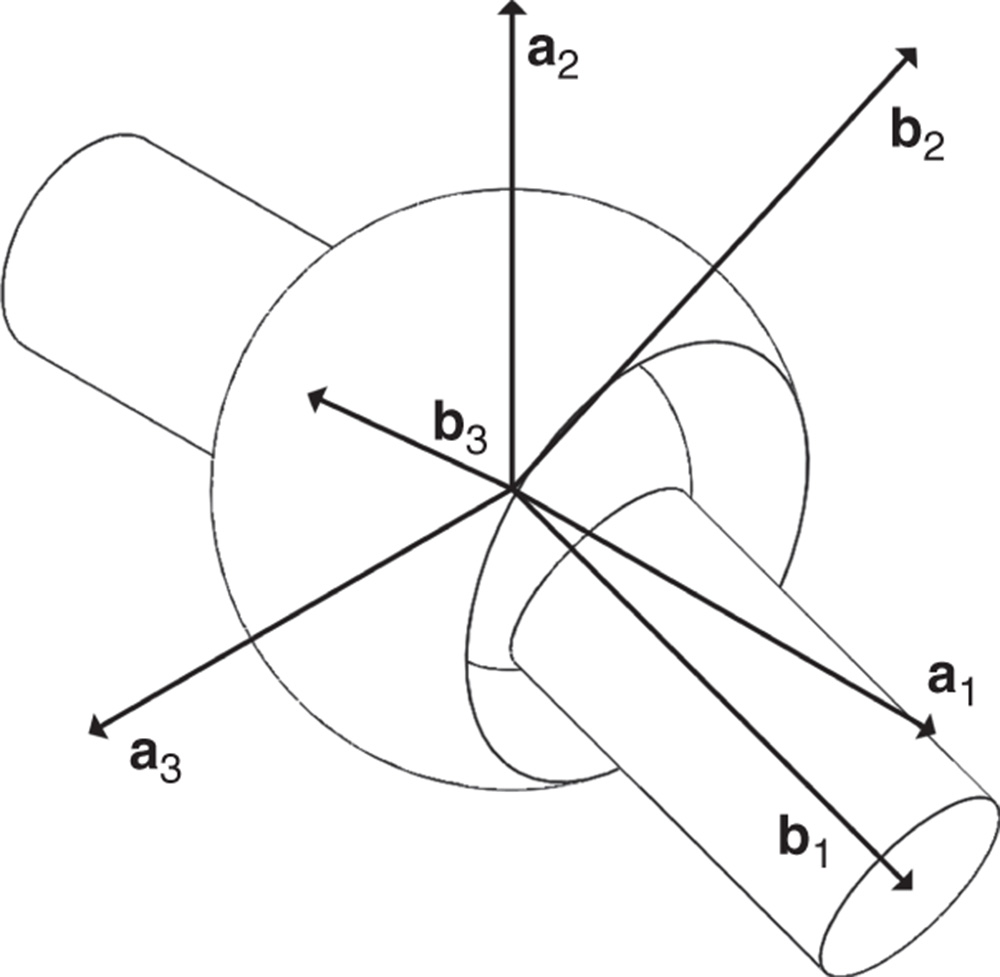

It is possible to expand on this idea and study more complicated notions of the ways the two bodies can interact with one another. The discussion of constraints between bodies will describe how different frames  and

and  that are fixed in each rigid body can move relative to each other. The frames

that are fixed in each rigid body can move relative to each other. The frames  and

and  will be referred to asjoint coordinate systems orjoint frames since they will be used to define precisely the manner in which the two bodies can interact. The joint coordinate systems are used to relate how the joint frames

will be referred to asjoint coordinate systems orjoint frames since they will be used to define precisely the manner in which the two bodies can interact. The joint coordinate systems are used to relate how the joint frames  and

and  may rotate relative to one another, or how the origins of the the two frames can translate relative to one another. A schematic figure of the two bodies with their joint coordinate systems before enforcing any constraints is given in Figure 3.4.

may rotate relative to one another, or how the origins of the the two frames can translate relative to one another. A schematic figure of the two bodies with their joint coordinate systems before enforcing any constraints is given in Figure 3.4.

Figure 3.4 Two rigid bodies with joint coordinate systems prior to constraint.

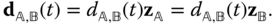

Figure 3.5 Ideal prismatic joint. (a) Line drawing. (b) CAD example.

3.2.1 The Prismatic Joint

Aprismatic joint is an ideal joint that only allows relative translation along a single direction that is fixed in each of the joint frames  and

and  . Schematics of a typical prismatic joint are shown in Figures 3.5a and 3.5b, with the direction of translation along the

. Schematics of a typical prismatic joint are shown in Figures 3.5a and 3.5b, with the direction of translation along the  axis of the two coordinate frames

axis of the two coordinate frames  and

and  . This joint does not allow change in the relative orientation of the two bodies. The direction of relative translation is fixed and constant relative to each of the bodies

. This joint does not allow change in the relative orientation of the two bodies. The direction of relative translation is fixed and constant relative to each of the bodies  and

and  . Since no change in the relative orientation is permitted between the two bodies, the rotation matrix

. Since no change in the relative orientation is permitted between the two bodies, the rotation matrix  relating the joint coordinate systems is constant.

relating the joint coordinate systems is constant.

This constraint is equivalent to requiring that the three relative rotation angles that parameterize the relative rotation matrix are held constant. Frequently, the two joint coordinate systems are chosen such that they are aligned, making  the identity matrix.

the identity matrix.

Suppose that  is the direction of relative translation permitted by body

is the direction of relative translation permitted by body  and that

and that  is the direction of relative translation permitted by body

is the direction of relative translation permitted by body  . The relative offset vector relating the origins of the joint frames must satisfy

. The relative offset vector relating the origins of the joint frames must satisfy

The definitions above imply that the homogeneous transform relating the joint coordinate systems

relating the joint coordinate systems and

and  is given by

is given by

for all time  . Analogous expressions can be derived if the 1 or 2 axes are used to define the degree of freedom. The task of deriving the homogeneous transforms in these cases is an exercise.

. Analogous expressions can be derived if the 1 or 2 axes are used to define the degree of freedom. The task of deriving the homogeneous transforms in these cases is an exercise.

Altogether, there are five independent scalar conditions implied by Equation (3.7) and the requirement that  is a constant matrix. Three constraints arise from the requirement that the frames do not rotate relative to one another, and two more constraints enforce the condition that no translation perpendicular to the

is a constant matrix. Three constraints arise from the requirement that the frames do not rotate relative to one another, and two more constraints enforce the condition that no translation perpendicular to the  axis occurs. Since there are five constraints imposed on the motion of the two bodies, the prismatic joint is a single degree of freedom ideal joint. The homogeneous transformation that characterizes the relationship between the two joint coordinate systems can be written in terms of a single time varying parameter,

axis occurs. Since there are five constraints imposed on the motion of the two bodies, the prismatic joint is a single degree of freedom ideal joint. The homogeneous transformation that characterizes the relationship between the two joint coordinate systems can be written in terms of a single time varying parameter,  . The relative translation, or displacement,

. The relative translation, or displacement,  is thejoint variable for the prismatic joint.

is thejoint variable for the prismatic joint.

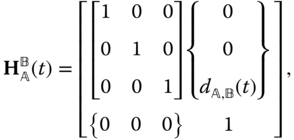

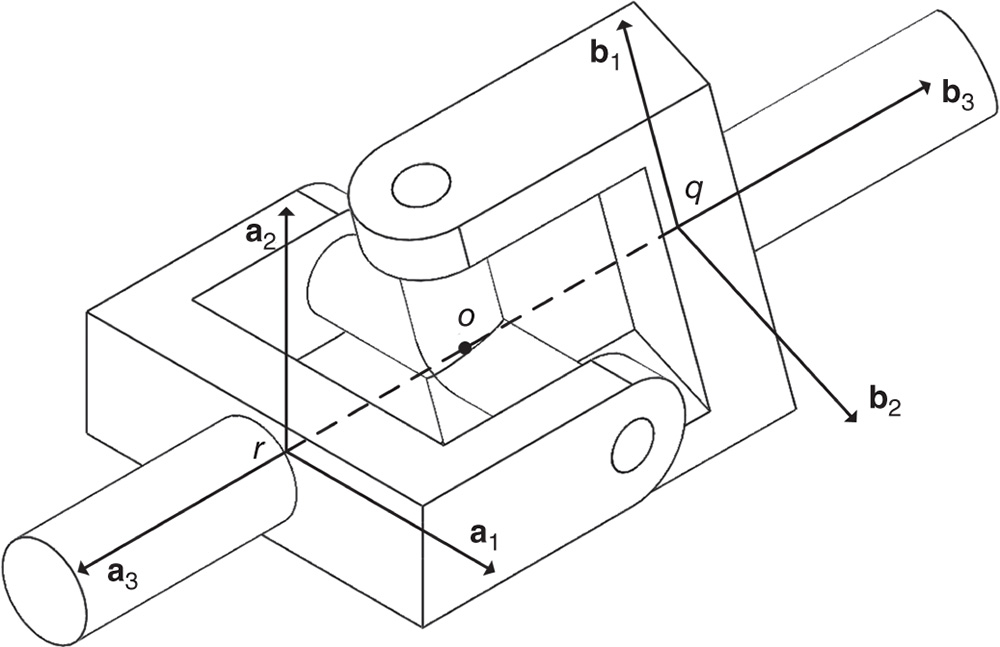

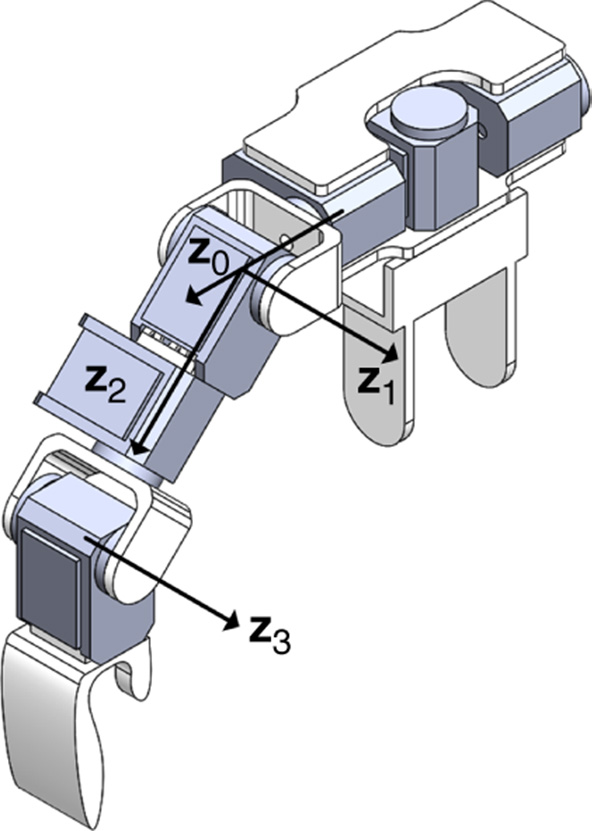

3.2.2 The Revolute Joint

In the last section, the prismatic joint was seen to constrain the motion of two bodies so that only translation along a single direction is possible. Therevolute joint is an analogous single degree of freedom ideal joint that constrains the motion of two bodies so that only rotation about a single axis is possible. A schematic of a typical revolute joint is given in Figures 3.6a and 3.6b with the axis of rotation fixed along the  axis of frames

axis of frames  and

and  .

.

Figure 3.6 Ideal revolute joint. (a) Line drawing. (b) CAD example.

The mathematical relationships that describe this physical constraint can, again, be expressed in terms of the joint coordinate frames  and

and  . The revolute joint restricts the translational motion of the two bodies by requiring that the origin of the joint frames

. The revolute joint restricts the translational motion of the two bodies by requiring that the origin of the joint frames  and

and  differ by a constant vector, which is often selected to be zero. In the case that the origins coincide for all time,

differ by a constant vector, which is often selected to be zero. In the case that the origins coincide for all time,  .

.

The bodies are able to rotate relative to one another about a single, common joint axis. Suppose that the common axis of rotation is  . The rotation matrix

. The rotation matrix  that maps the joint frame

that maps the joint frame  into the joint frame

into the joint frame  must have the form

must have the form

for all times  . Again, similar expressions can be derived if the axis of rotation is selected to be the 1 or 2 axes. These derivations are left as an exercise.

. Again, similar expressions can be derived if the axis of rotation is selected to be the 1 or 2 axes. These derivations are left as an exercise.

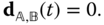

Equation (3.9) and the fact that  imply that the homogeneous transform that relates the joint coordinate systems is given by

imply that the homogeneous transform that relates the joint coordinate systems is given by

Equation (3.9) and the condition  induce a total of five scalar constraints on the motion of bodies

induce a total of five scalar constraints on the motion of bodies  and

and  . Three of the scalar constraints result from the condition

. Three of the scalar constraints result from the condition  , which prevents relative translation. The rotational restraint in Equation (3.9) imposes two additional scalar relationships. The revolute joint is a one degree of freedom ideal joint. The angle

, which prevents relative translation. The rotational restraint in Equation (3.9) imposes two additional scalar relationships. The revolute joint is a one degree of freedom ideal joint. The angle  is the joint variable for the single degree of freedom revolute joint.

is the joint variable for the single degree of freedom revolute joint.

3.2.3 Other Ideal Joints

In this book, the robotic systems that are considered are constructed from collections of rigid bodies, or links, that are connected by either prismatic joints or revolute joints. It is possible to construct other ideal joints using these two joint primitives by introducing one or more “zero length links” that are connected by revolute and/or prismatic joints. Any ideal joint having between 1 and 6 degrees of freedom can be derived in this way. Alternatively, it is also possible to derive directly the form of the homogeneous transformation that represents an ideal joint. The next example carries this out for theuniversal joint.

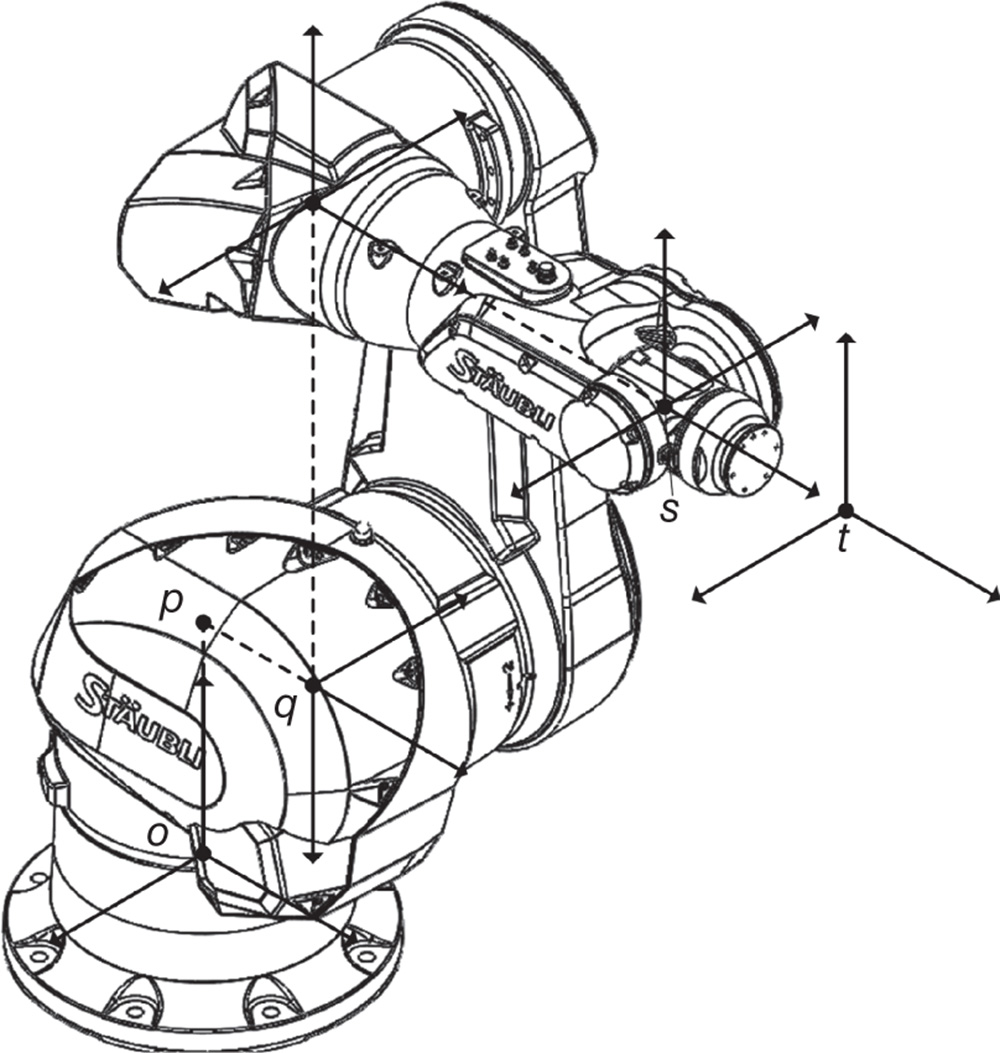

3.3 The Denavit–Hartenberg Convention

Section 3.1 introduced homogeneous transformations and showed that they can be used to represent rigid body motion. Each homogeneous transformation is specified in terms of a rotation matrix describing the orientation and a vector describing the translation of a rigid body motion. No particular framework was introduced for the selection of the frames of reference that are implicit in the definition of a homogeneous transform. It is always possible to choose the orientation and origin of the frames to fit the problem at hand.

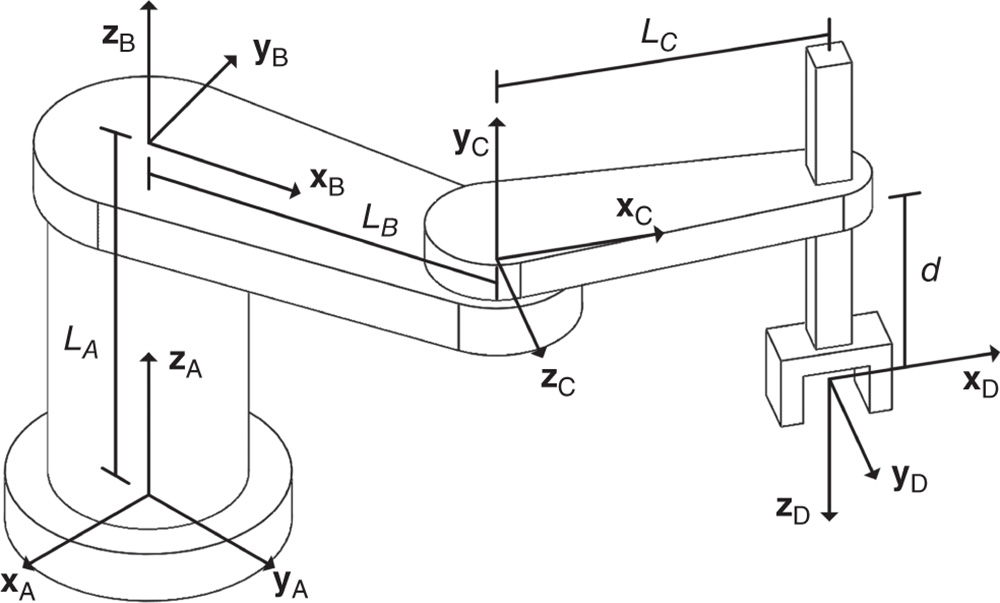

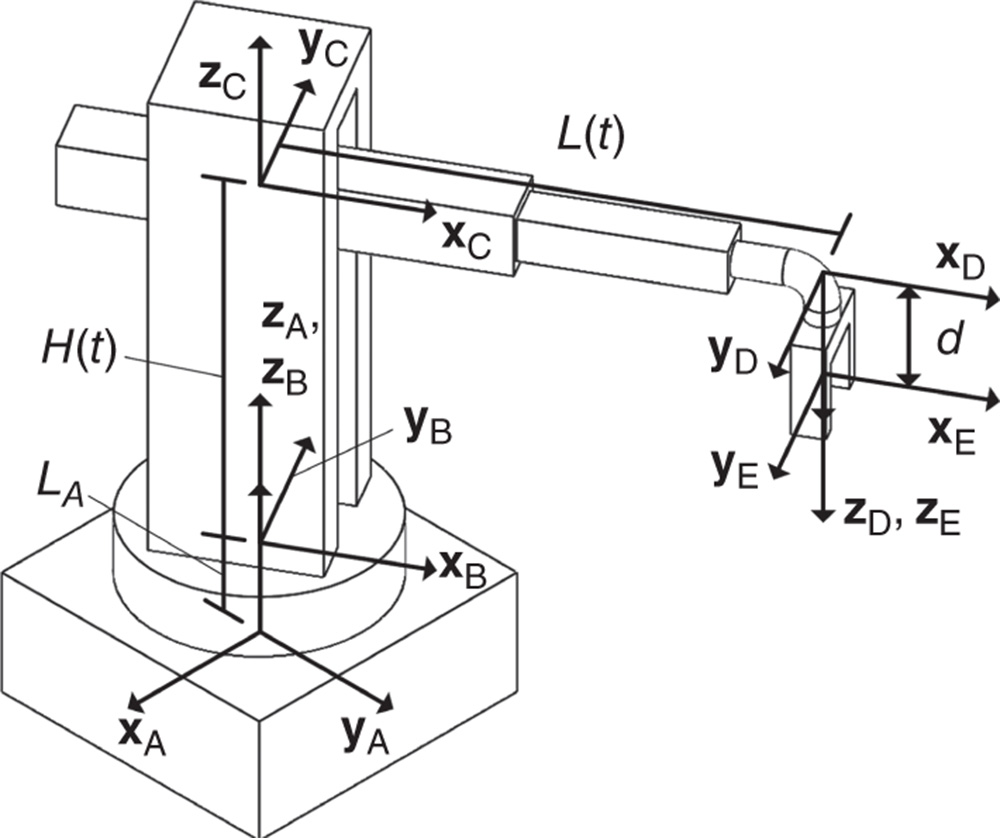

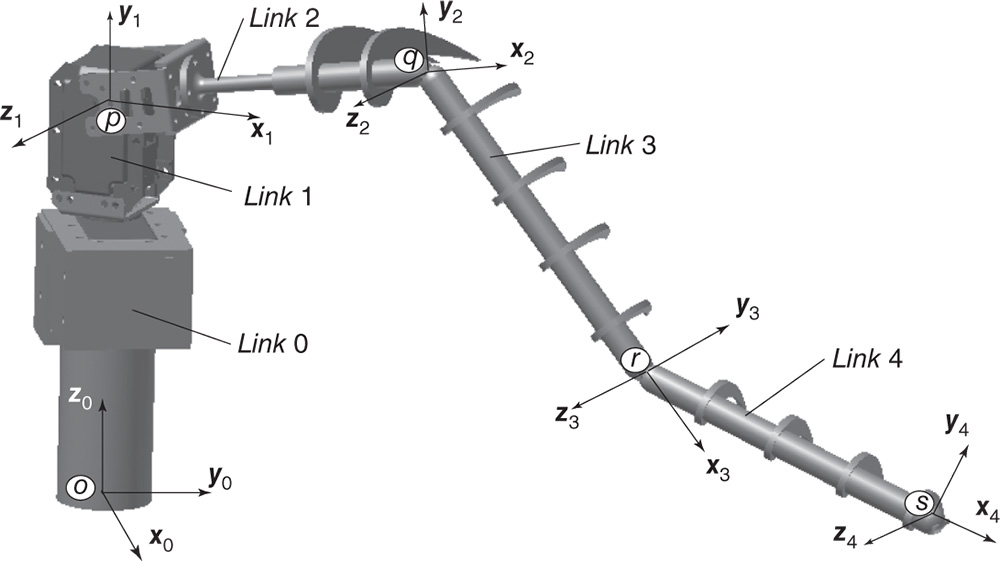

This section describes theDenavit–Hartenberg (DH) convention, one of the most popular conventions for the construction of homogeneous transformations associated with robotic systems. This convention is used to model robots that have the structure ofkinematic chains. A wide variety of robotic systems are included in this class, including the SCARA robot (Problem 3.1), cylindrical robots (Problem 3.2), and modular robots (Problem 3.3).

Even if the robotic system under consideration does not have the form of a kinematic chain, it is often possible to analyze subsystems of the robotic system using the DH convention. If the system has the connectivity of atopological tree, the DH convention can be used without modification to model the kinematics of any of the branches of the tree relative to the core body. The anthropomorphic robot in Figure 2.3 is an example of a robotic system that has the connectivity of a topological tree.

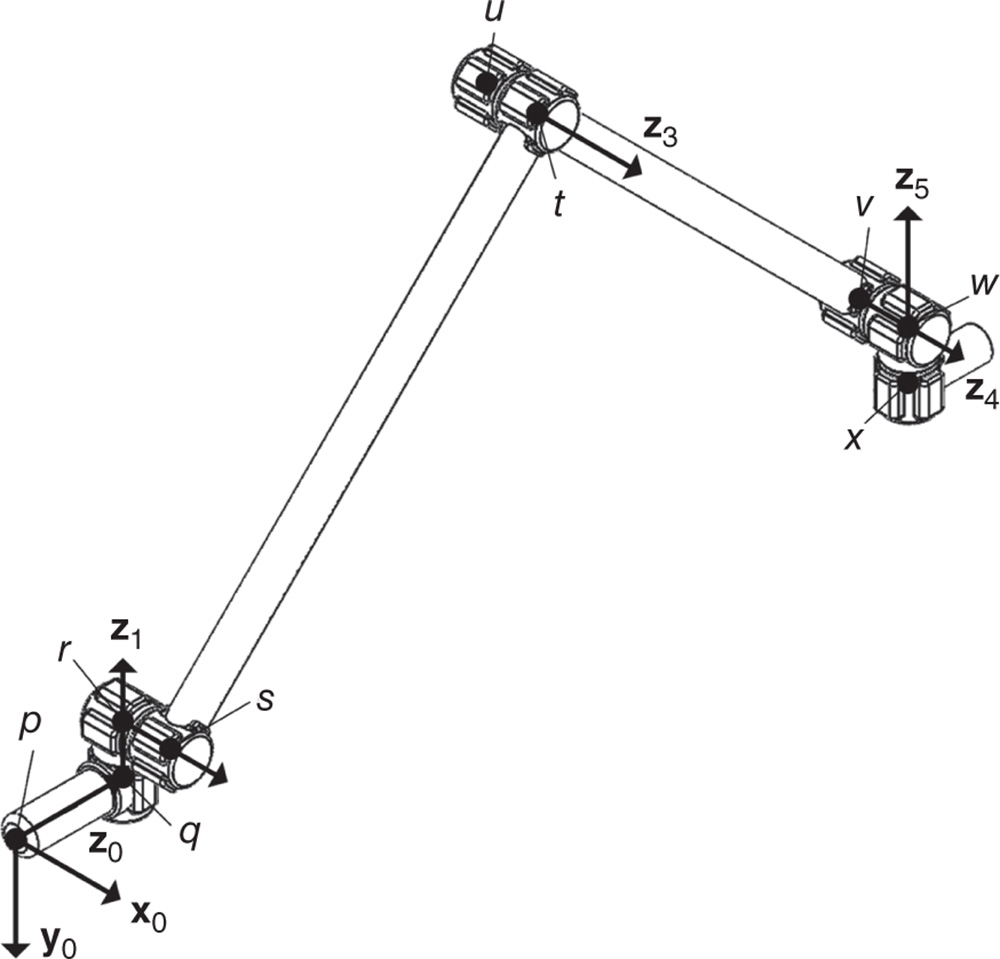

3.3.1 Kinematic Chains and Numbering in the DH Convention

The description of the connectivity of general robotic systems can be complex. Connectivity of robotic systems is often categorized into three classes of systems: those that (1) form kinematic chains, (2) form topological trees, and (3) contain closed loops. It is possible to define connectivity in abstract form via the introduction of the connectivity graph of the system. The interested reader is referred to [46] for a detailed account. In this book, the following definition will suffice.

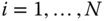

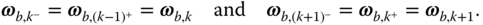

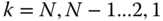

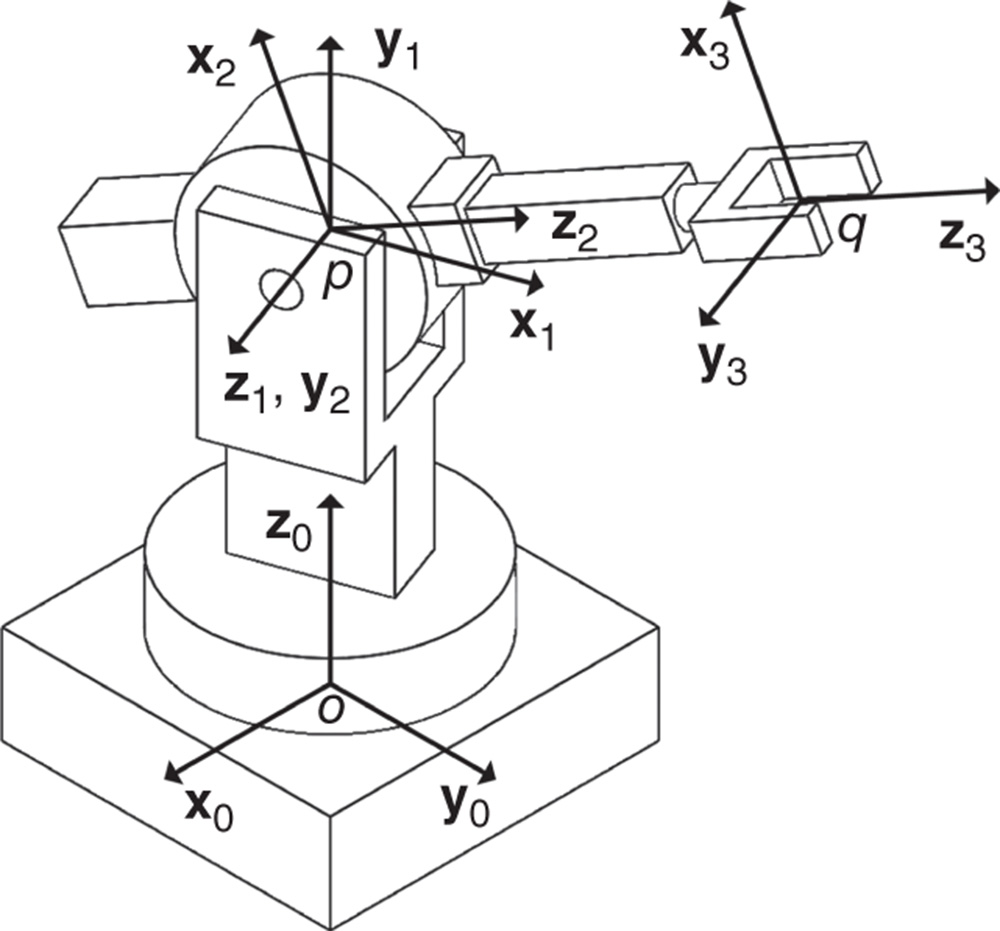

In practice, there should not be a problem identifying a kinematic chain. However, there are a few other conventions that are followed for describing the kinematics of a chain. In the DH convention, each body  has a body fixed frame designated simply by

has a body fixed frame designated simply by  for

for  . Frame 0 is denoted theroot frame,core frame or thebase frame of the kinematic chain. Often the root frame is identified with the ground or inertial frame, as is the case for a robotic manipulator that is located along an assembly line. However, there are some common exceptions to this rule. In the case of a system having connectivity of a topological tree, the frame 0 is often identified with the central body. The anthropomorphic robot is an example of this case. Frame 0 may also not be fixed in an inertial frame. For example, when constructing a model of the space shuttle remote manipulator system (RMS), the shuttle is usually selected as the base frame. For the RMS, the shuttle would be denoted the root frame.

. Frame 0 is denoted theroot frame,core frame or thebase frame of the kinematic chain. Often the root frame is identified with the ground or inertial frame, as is the case for a robotic manipulator that is located along an assembly line. However, there are some common exceptions to this rule. In the case of a system having connectivity of a topological tree, the frame 0 is often identified with the central body. The anthropomorphic robot is an example of this case. Frame 0 may also not be fixed in an inertial frame. For example, when constructing a model of the space shuttle remote manipulator system (RMS), the shuttle is usually selected as the base frame. For the RMS, the shuttle would be denoted the root frame.

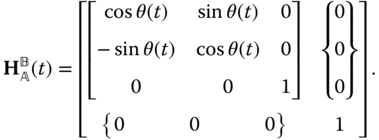

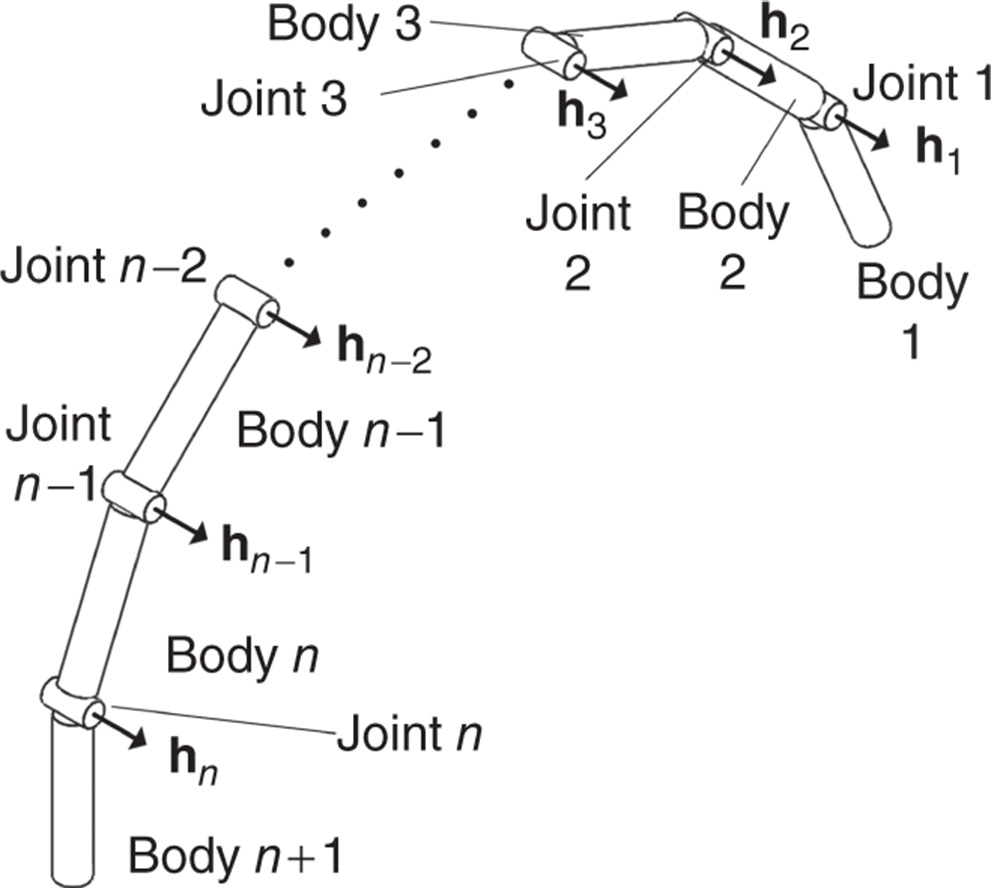

Another convention followed in this book is based on the assumption that each joint in the kinematic chain shown in Figure 3.8 is either a revolute joint or a prismatic joint. The generic symbol  for

for  is used to denote the joint variable. In other words,

is used to denote the joint variable. In other words,

By definition, joint variable  describes how frame

describes how frame  is articulated, or actuated, for

is articulated, or actuated, for  . For example, if joint

. For example, if joint  is a revolute joint, the joint variable

is a revolute joint, the joint variable  defines how frame

defines how frame  rotates relative to frame

rotates relative to frame  . Joint variable

. Joint variable  is said to actuate frame

is said to actuate frame  or link

or link  .

.

Finally, the vectors  are defined in the basis for frame

are defined in the basis for frame  as the direction associated with the degree of freedom associated with joint

as the direction associated with the degree of freedom associated with joint  , for

, for  . For example,

. For example,  is the direction of the degree of freedom

is the direction of the degree of freedom  in joint 1,

in joint 1,  is the direction of the degree of freedom

is the direction of the degree of freedom  in joint

in joint  , etc. The numbering of joints, links or bodies, frames and axes of the degrees of freedom for a kinematic chain is depicted in Figure 3.8.

, etc. The numbering of joints, links or bodies, frames and axes of the degrees of freedom for a kinematic chain is depicted in Figure 3.8.

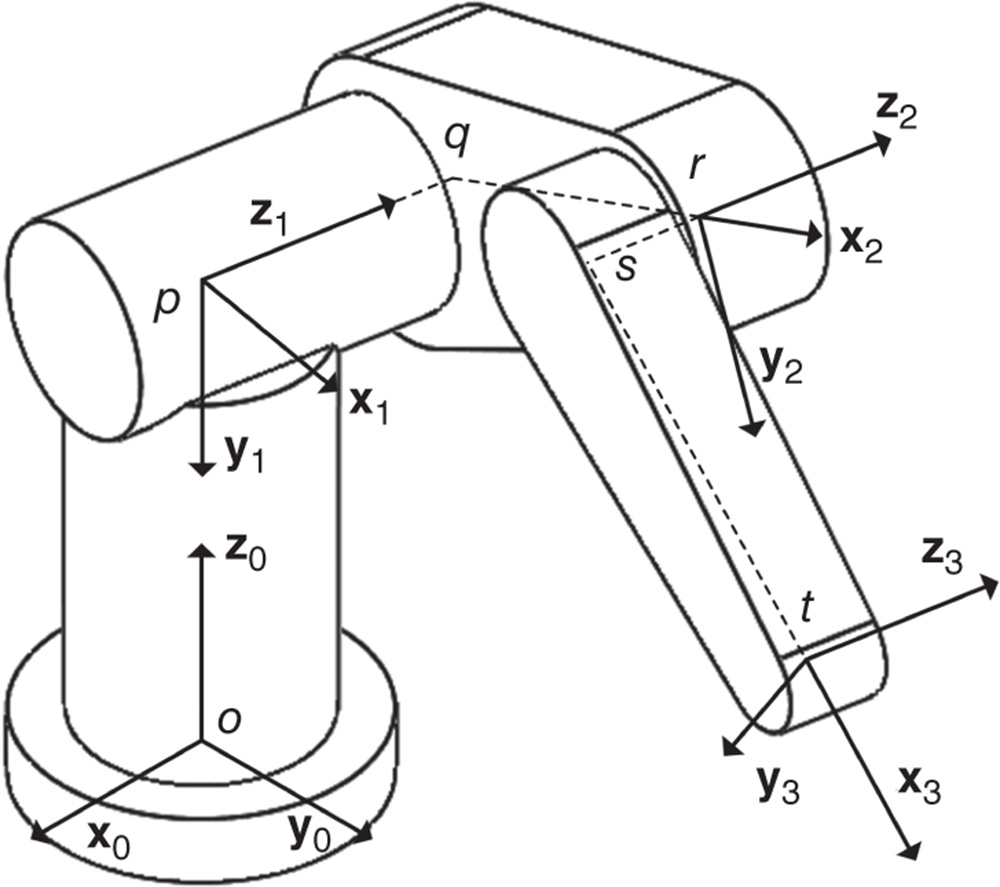

Figure 3.8 Body and joint numbering of a kinematic chain for the DH convention.

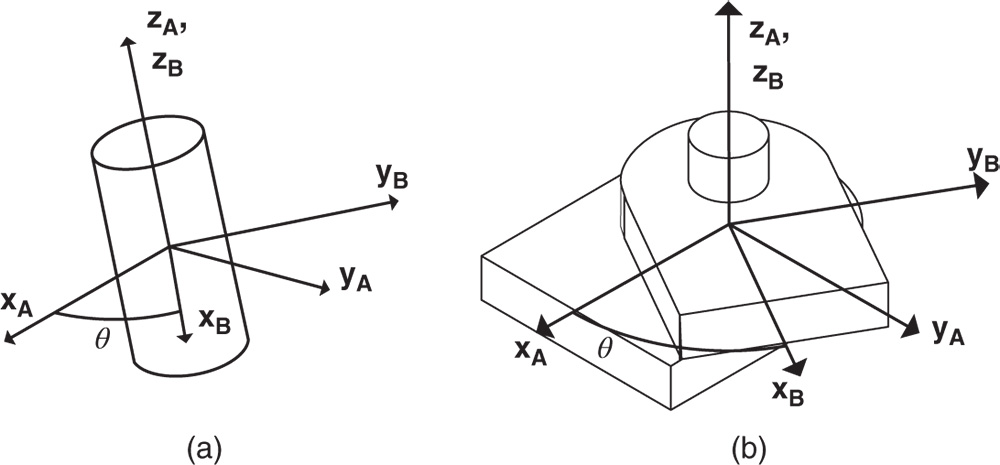

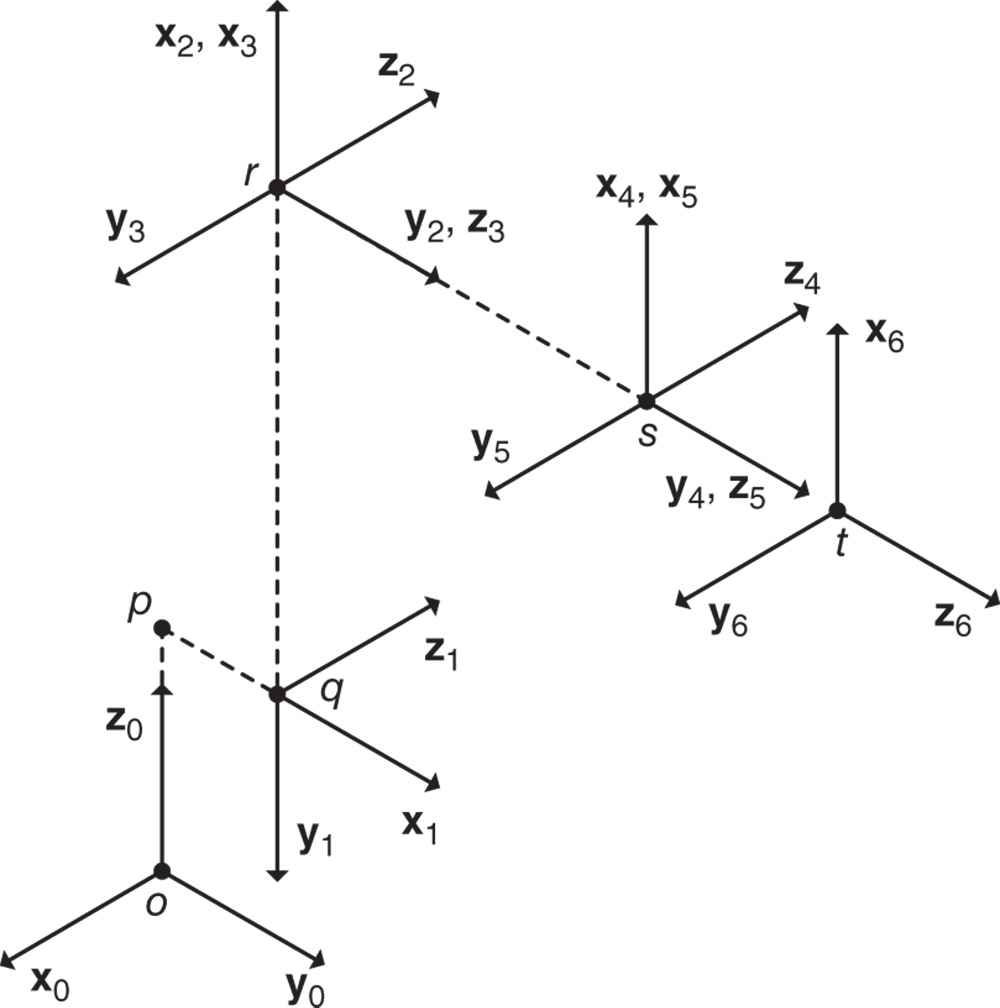

3.3.2 Definition of Frames in the DH Convention

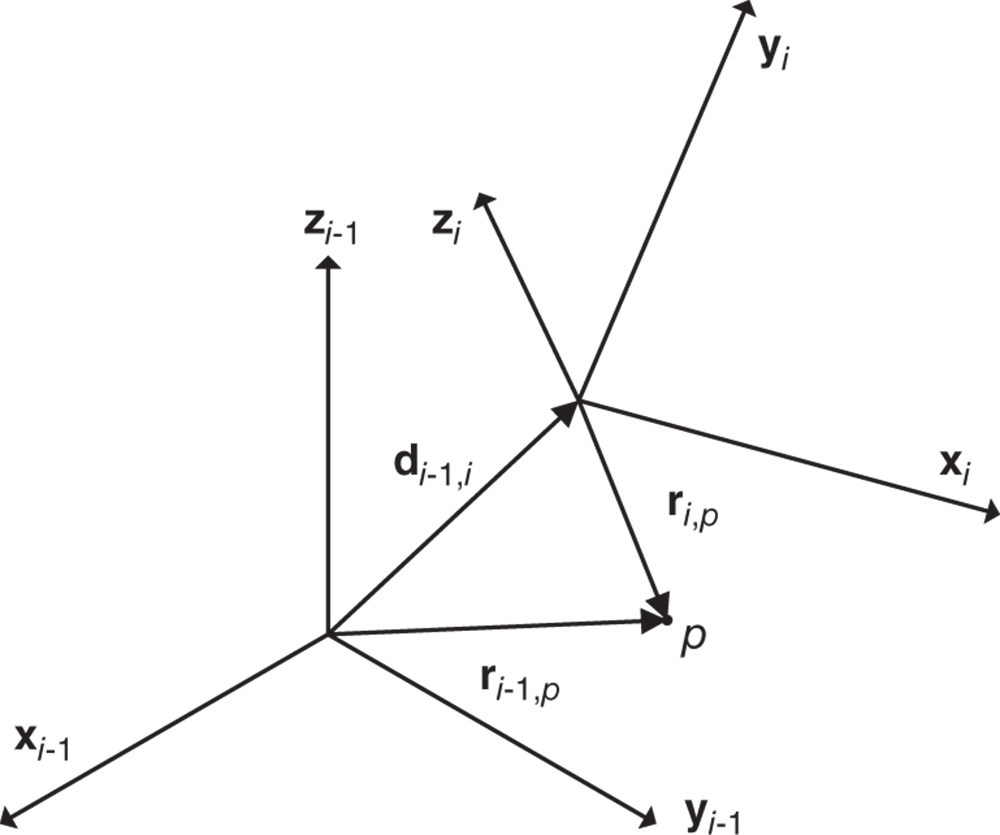

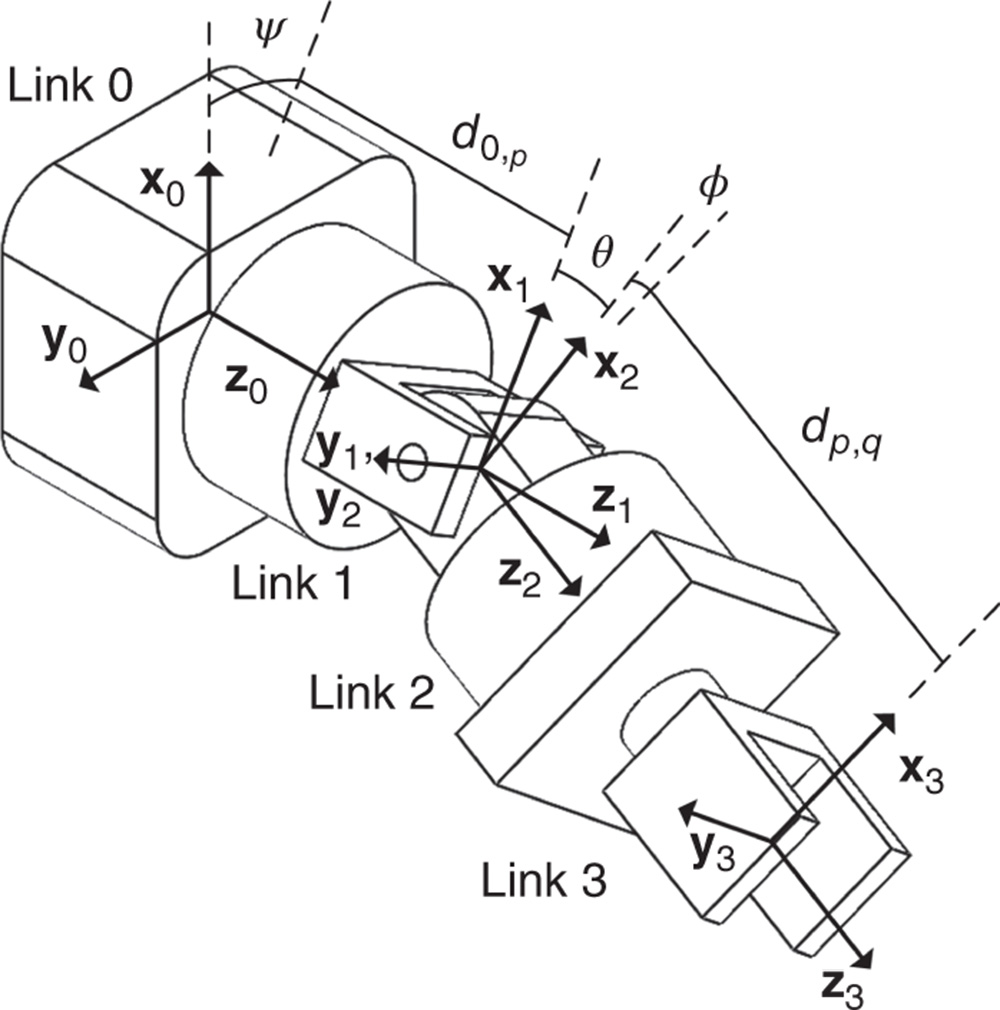

The definition of a homogeneous transformation associated with some arbitrary rigid body motion generally requires six parameters. If the frame under consideration is located with an arbitrary origin position with an arbitrary orientation with respect to a base frame, it will require in general three independent translational variables and three independent rotational angles to map the frame onto the base frame, or vice versa. The DH convention defines a specific set of criteria followed when selecting the frames that are used to describe a kinematic chain. Between a given pair of bodies, two successive frames in the chain are oriented as depicted in Figure 3.9. With these restrictions on the choice of the relative origin positions and relative orientations of the successive frames, the DH convention uses four parameters to characterize the homogeneous transform between pairs of frames.

Figure 3.9 Geometry of the DH convention.

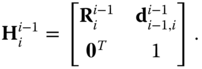

The DH convention relates each pair of body fixed frames  and

and  in the kinematic chain using a homogeneous transform with a specific structure. The frames in the kinematic chain are selected so that they take the configuration shown in Figure 3.9. The basis vector

in the kinematic chain using a homogeneous transform with a specific structure. The frames in the kinematic chain are selected so that they take the configuration shown in Figure 3.9. The basis vector  is chosen so that it intersects and is perpendicular to the basis vector

is chosen so that it intersects and is perpendicular to the basis vector  . This is the fundamental assumption underlying the DH convention.

. This is the fundamental assumption underlying the DH convention.

3.3.3 Homogeneous Transforms in the DH Convention

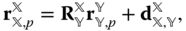

If the frames  satisfy the DH convention in Definition 3.2, it is possible to derive the corresponding transformation that maps homogeneous coordinates in frame

satisfy the DH convention in Definition 3.2, it is possible to derive the corresponding transformation that maps homogeneous coordinates in frame  onto the homogeneous coordinates in frame

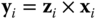

onto the homogeneous coordinates in frame  . Consider Figure 3.11 in which the position vectors

. Consider Figure 3.11 in which the position vectors  and

and  are shown, along with the relative offset

are shown, along with the relative offset  between the origin of frames

between the origin of frames  and

and  . The homogeneous transformation that relates these two frames follows from the general definitions discussed in Section 3.1. The homogeneous transformation

. The homogeneous transformation that relates these two frames follows from the general definitions discussed in Section 3.1. The homogeneous transformation  is defined such that

is defined such that

The following theorem gives a succinct expression for the homogeneous transform  between two consecutive frames in a kinematic chain that are constructed according to the DH convention.

between two consecutive frames in a kinematic chain that are constructed according to the DH convention.

Figure 3.10

Intermediate frame  in the DH convention.

in the DH convention.

Figure 3.11 Construction of the Homogeneous Transform in the DH Convention

Example 3.3 in the MATLAB Workbook for DCRS creates a function that calculates homogeneous transformations that map between adjacent frames in a kinematic chain using the DH convention.

3.3.4 The DH Procedure

The DH Convention can form the foundation for a systematic procedure for determining the model of a kinematic chain. Suppose a kinematic chain is under consideration in which the bodies are numbered from 0 to  , and the joints are numbered from 1 to

, and the joints are numbered from 1 to  as described in Definition 3.1. The first step in the procedure assigns the unit vectors

as described in Definition 3.1. The first step in the procedure assigns the unit vectors  through

through  to the axes of the degrees of freedom for each of the joints. If the

to the axes of the degrees of freedom for each of the joints. If the  th joint is a revolute joint,

th joint is a revolute joint,  is assigned to the axis of rotation of the joint. If the

is assigned to the axis of rotation of the joint. If the  th joint is a prismatic joint,

th joint is a prismatic joint,  is assigned to the direction of translation in the joint.

is assigned to the direction of translation in the joint.

After axes  through

through  have been assigned to the directions of the degrees of freedom, the origins of the frames are selected. The origin of frame 0 can be chosen to be any convenient point along the

have been assigned to the directions of the degrees of freedom, the origins of the frames are selected. The origin of frame 0 can be chosen to be any convenient point along the  axis. The origin of each of the remaining frames for

axis. The origin of each of the remaining frames for  must be selected so that successive pairs of frames are configured as illustrated in Figure 3.9.

must be selected so that successive pairs of frames are configured as illustrated in Figure 3.9.

The remaining origins are selected recursively, starting from  using the previously defined

using the previously defined  , then

, then  using

using  , and continuing through

, and continuing through  . The origin of the frame

. The origin of the frame  must be selected so that the vector

must be selected so that the vector  intersects and is perpendicular to

intersects and is perpendicular to  . Carefully adhering to this procedure ensures that the kinematic model is consistent with the DH convention. The selection of

. Carefully adhering to this procedure ensures that the kinematic model is consistent with the DH convention. The selection of  and the origin of the

and the origin of the  frame depends on the relative orientation of the vectors

frame depends on the relative orientation of the vectors  and

and  .

.

If  and

and  are not coplanar, there is a unique direction normal to both vectors. The origin of frame

are not coplanar, there is a unique direction normal to both vectors. The origin of frame  must be chosen so that

must be chosen so that  aligns with this unique normal. Frame

aligns with this unique normal. Frame  is then completed by defining

is then completed by defining  to ensure the frame is dexterous.

to ensure the frame is dexterous.

If the vectors  and

and  are coplanar, there are two cases to consider, leading to two possibilities for the choice of the origin. The first case is when the coplanar vectors

are coplanar, there are two cases to consider, leading to two possibilities for the choice of the origin. The first case is when the coplanar vectors  and

and  are parallel. In this case there are an infinite number of vectors that intersect and are perpendicular to both

are parallel. In this case there are an infinite number of vectors that intersect and are perpendicular to both  and

and  . In principle, it is possible to choose the origin of frame

. In principle, it is possible to choose the origin of frame  in this case so that the

in this case so that the  axis aligns with any of the infinite number of common normals. The second case is when the coplanar vectors

axis aligns with any of the infinite number of common normals. The second case is when the coplanar vectors  and

and  intersect at a single point. In this case the vector

intersect at a single point. In this case the vector  is defined to be normal to the plane spanned by

is defined to be normal to the plane spanned by  and

and  , and the origin of frame

, and the origin of frame  is chosen as point of intersection of

is chosen as point of intersection of  and

and  .

.

The procedure above is summarized in procedure shown in Figure 3.12.

- Number the links in the kinematic chain from

, and number the joints in the kinematic chain from

, and number the joints in the kinematic chain from  .

. - Assign the unit vectors

to the axes of the degrees of freedom for joints

to the axes of the degrees of freedom for joints  .

. - Choose the origin of the 0 frame along the

axis.

axis. - Repeat the following for

:

:

- If the vectors

and

and  are not coplanar, select the origin of frame

are not coplanar, select the origin of frame  so that

so that  is aligned with the common normal to

is aligned with the common normal to  and

and  .

. - If the vectors

and

and  are parallel, choose the origin

are parallel, choose the origin  at any convenient location along the

at any convenient location along the  axis. Choose

axis. Choose  along one of the infinite number of common normals to

along one of the infinite number of common normals to  and

and  .

. - If the vectors

and

and  intersect, choose the origin

intersect, choose the origin  at the point of intersection. Select

at the point of intersection. Select  to be perpendicular to the plane spanned by

to be perpendicular to the plane spanned by  and

and  .

. - Choose the axis

to satisfy the right hand rule given

to satisfy the right hand rule given  and

and  selected above.

selected above.

- If the vectors

- Choose the last frame so that

intersects and is perpendicular to

intersects and is perpendicular to  . Otherwise, choose the frame so that it is aligned with the problem at hand.

. Otherwise, choose the frame so that it is aligned with the problem at hand.

Figure 3.12 DH procedure for kinematic chains.

The DH procedure, as summarized in Figure 3.12, is not a simple process, and the frames generated by the procedure can be counter intuitive. An experienced analyst might choose frames in a completely different manner. However, the advantage of the DH procedure is that it facilitates communication: anyone familiar with the procedure can reconstruct how the unknowns have been selected from a simple table oflink parameters. The following examples show how the procedure can be used in practical problems with a simple model that utilizes two body fixed frames.

The last example required only two frames, but it is not uncommon that dozens of frames are required in models of realistic robotic systems. The next example considers a single leg of a humanoid robot model that utilizes five different frames.

3.3.5 Angular Velocity and Velocity in the DH Convention

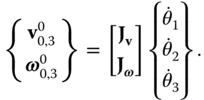

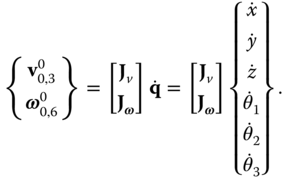

So far in Chapter , general principles of kinematics for three dimensional, complex systems have been introduced. This section adapts some of these principles to the analysis of robotic systems that form kinematic chains and for which the DH convention applies. This section introduces theJacobian matrices that relate the velocity of specific points of interest and the angular velocity of the bodies on which they lie to the time derivative of the joint variables.

The superscript on  is used to denote that the velocity

is used to denote that the velocity  and angular velocity

and angular velocity  are expressed in components relative to the

are expressed in components relative to the  frame, such that

frame, such that

By extension, the change of basis operation for the Jacobian may be defined as

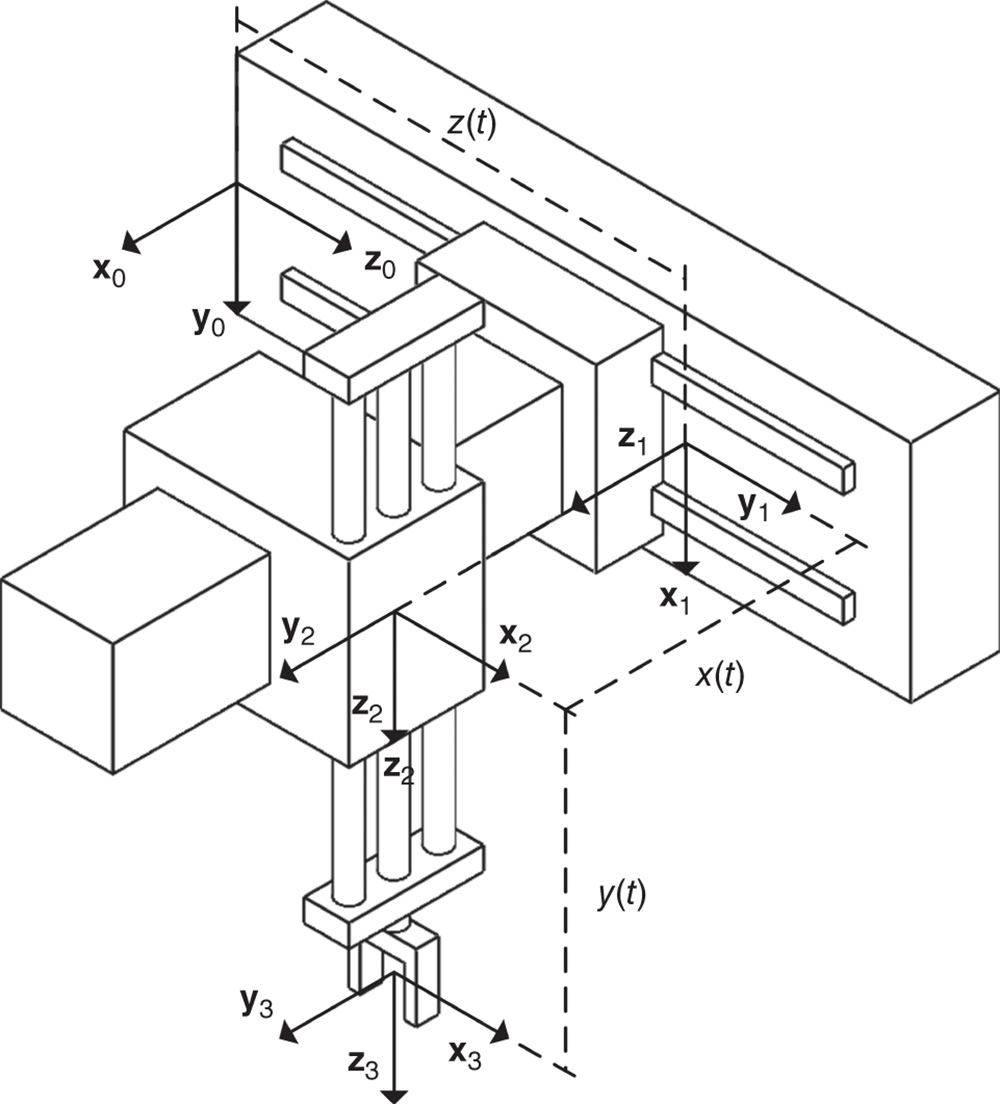

3.4 Recursive Formulation of Forward Kinematics

The DH procedure is one of many strategies that can be used to formulate the kinematics of robotic systems. This section will introduce an alternative approach for modeling the kinematics of robot systems. This technique is an example of arecursive formulation of the kinematics of a robotic system. Numerous variants of these formulations have appeared in the literature. The text [14] gives a comprehensive account of this approach by one of the early developers of the method. The specific variant presented in this text of this family of methods is based on the family of papers [38], [37], [22], [39], [16], [25], [26] because they provide a unified approach to both kinematics and dynamics.

These papers deduce the recursive algorithms for kinematics and dynamics of robots by employing the similar structure of techniques in estimation and filtering theory. For example, [38] explains that recursive formulations can be interpreted in the framework of Kalman filtering and smoothing. Kalman filtering is a well known procedure in estimation theory that derives recursive updates of estimates, as well as associated efficient numerical techniques for their computation. One of the major contributions of the family of papers inspired by [38], and its immediate successors in [22], [23], [39], [25], and [26] has been to show how certain factorizations that appear in the context of Kalman filtering can be used directly to solve problems in dynamics and control of multi‐body systems. This chapter covers the recursive formulations of forward kinematics, while Chapter discusses the extension of these techniques to forward dynamics.

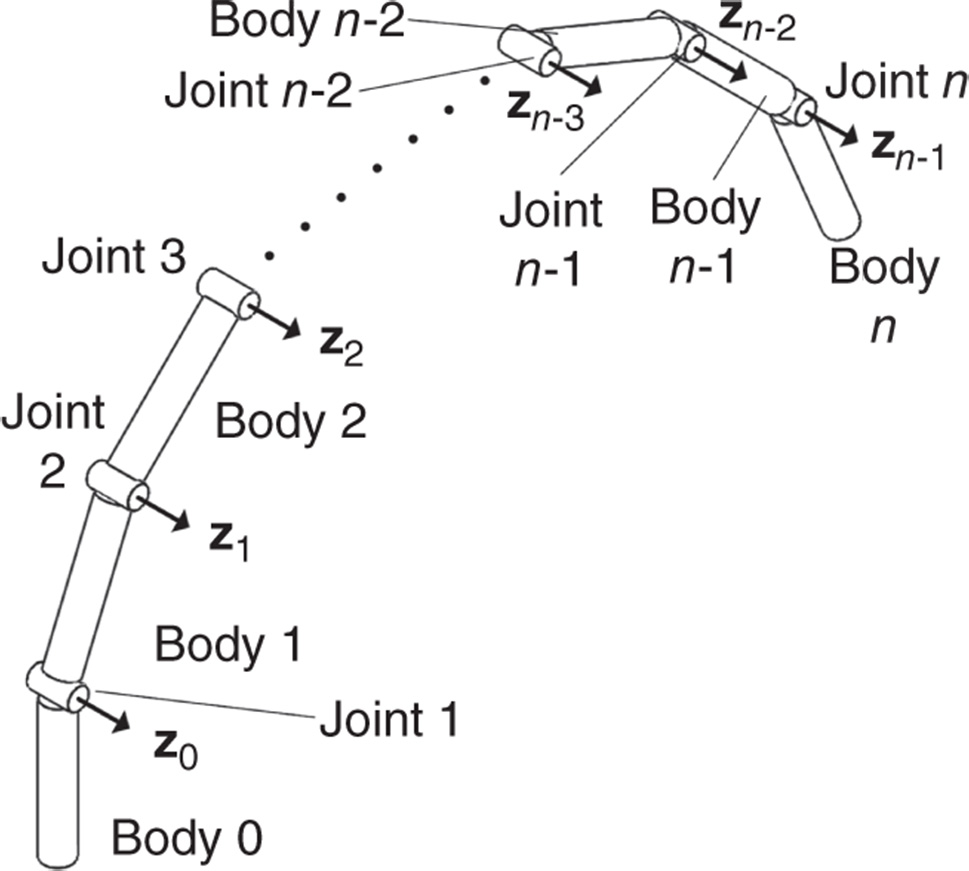

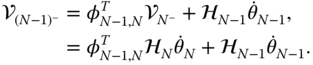

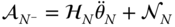

Figure 3.20 depicts a kinematic chain for which the kinematic equations will be derived. This kinematic chain is comprised of  links numbered from

links numbered from  to 1, which are connected with

to 1, which are connected with  joints numbered

joints numbered  to 1.

to 1.

Figure 3.20 Body and joint numbering of a kinematic chain for the recursive formulation.

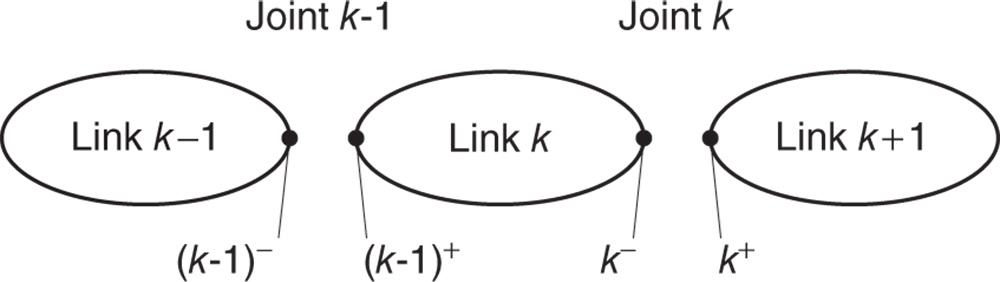

Figure 3.21 Joint side labeling of a kinematic chain for the recursive formulation.

In contrast to the DH convention, the links and joints are numbered from the tip of the kinematic chain to the root. This section and Chapter will show that this methodology of numbering the bodies and joints yields system matrices that can be factored as products of block lower triangular, diagonal and upper triangular factors. It is the special structure of these matrices that enables fast and recursive solution procedures to be devised. The numbering of consecutive joints in the kinematic chain is shown in Figure 3.21. The notation  will be used to refer to thebase body, that is link

will be used to refer to thebase body, that is link  .

.

The two sides of joint  are denoted by

are denoted by  and

and  . Specifically, the notation

. Specifically, the notation  refers the point at joint

refers the point at joint  fixed on body

fixed on body  . By definition, point

. By definition, point  is on the outboard side of joint

is on the outboard side of joint  , toward the free end of the kinematic chain. The notation

, toward the free end of the kinematic chain. The notation  refers to the point at joint

refers to the point at joint  fixed on body

fixed on body  . The point

. The point  is on the inboard side of joint

is on the inboard side of joint  , toward the base body of the kinematic chain.

, toward the base body of the kinematic chain.

Each joint  is defined by a vector

is defined by a vector  that describes the direction of the degree of freedom at joint

that describes the direction of the degree of freedom at joint  . For a revolute joint,

. For a revolute joint,  is along the rotational axis, while for a prismatic joint,

is along the rotational axis, while for a prismatic joint,  is along the translational axis. In the following discussion, it will be assumed that all joints under consideration are revolute. Modifications for prismatic joints are discussed in Problem 3.3.

is along the translational axis. In the following discussion, it will be assumed that all joints under consideration are revolute. Modifications for prismatic joints are discussed in Problem 3.3.

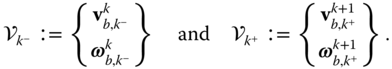

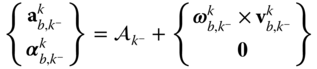

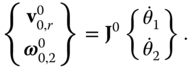

The velocities and angular velocities are collected in  vectors

vectors  and

and  , and the derivatives of the velocities and angular velocities are collected in the vectors

, and the derivatives of the velocities and angular velocities are collected in the vectors  and

and  . This section will address the evaluation of

. This section will address the evaluation of  and

and  , whereas

, whereas  and

and  will be treated in Section 3.4.3. In this convention the superscript

will be treated in Section 3.4.3. In this convention the superscript  or

or  denotes on which side of joint

denotes on which side of joint  the quantity is calculated. The subscript is used to specify the joint at which the velocities or their derivatives are calculated. These velocity vectors are defined as

the quantity is calculated. The subscript is used to specify the joint at which the velocities or their derivatives are calculated. These velocity vectors are defined as

By definition  is the velocity vector of point

is the velocity vector of point  in the base frame

in the base frame  , and

, and  is the angular velocity vector of the body that contains point

is the angular velocity vector of the body that contains point  relative to the base frame

relative to the base frame  . The term

. The term  contains the components relative to the basis for frame

contains the components relative to the basis for frame  of the velocity vector

of the velocity vector  . The term

. The term  contains the components relative to the basis for frame

contains the components relative to the basis for frame  of the angular velocity vector

of the angular velocity vector  . While this notation may seem unnecessarily complex, the following observations may help make it easier to interpret the entries in

. While this notation may seem unnecessarily complex, the following observations may help make it easier to interpret the entries in  and

and  .

.

- The velocity and angular velocity vectors that are contained in

and

and  refer to the points

refer to the points  and

and  , respectively.

, respectively. - The components of the velocity and angular velocity vectors that are contained in

are given with respect to the frame

are given with respect to the frame  in which the point

in which the point  is fixed. The components of the vectors in

is fixed. The components of the vectors in  are given with respect to frame

are given with respect to frame  in which the point

in which the point  is fixed.

is fixed.

Finally, it should be noted that the notation  and

and  is somewhat misleading. In general, the vector

is somewhat misleading. In general, the vector  is defined in Definition 2.9 as the angular velocity vector of the frame

is defined in Definition 2.9 as the angular velocity vector of the frame  in the frame

in the frame  . Because the frames

. Because the frames  and

and  are often fixed in some rigid body,

are often fixed in some rigid body,  is often described as the angular velocity of body

is often described as the angular velocity of body  relative to body

relative to body  . The vectors

. The vectors  and

and  are the angular velocities of “the frame containing point

are the angular velocities of “the frame containing point  ” or “the frame containing point

” or “the frame containing point  ” relative to the base frame. That is

” relative to the base frame. That is

Since this notation is common in the literature, this convention will be utilized when describing recursive formulations of kinematics and dynamics in Sections 3.4 and 4.8.

3.4.1 Recursive Calculation of Velocity and Angular Velocity

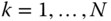

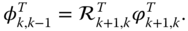

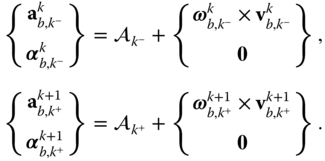

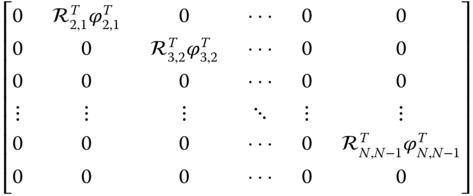

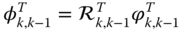

The following theorem summarizes the matrix equation that enables recursive calculation of velocities and angular velocities based on the numbering of bodies from the tip to the base of the chain.

The structure of Equation (3.13) facilitates a recursive algorithm for the solution of velocities and angular velocities in the kinematic chain. Suppose the joint angular rates  ,

,  ,...

,...  are given for each of the joints in the kinematic chain. From Equation (3.13),

are given for each of the joints in the kinematic chain. From Equation (3.13),  can be computed from the last row as

can be computed from the last row as

Next, from the  row,

row,  may be calculated as

may be calculated as

Continuing this process from the inboard joints to the outboard joints provides a solution for all the velocities and angular velocities in the kinematic chain. These steps are summarized in Figure 3.22.

- Number the joints and links in the kinematic chain from

starting at the base and moving to the tip.

starting at the base and moving to the tip. - Assign the unit vectors

to the joint degrees of freedom for

to the joint degrees of freedom for  .

. - Define the relative position vectors

for

for  .

. - Iterate from inboard to outboard joints for

.

.

- Form the transposed transition operator

- Calculate the velocity and angular velocity

- Form the transposed transition operator

Figure 3.22 Table Recursive algorithm for velocities and angular velocities.

3.4.2 Efficiency and Computational Cost

It is not necessary to form the entire matrix appearing in Equation (3.13) in practice. The recursive algorithm can be used in either symbolic or numerical calculations. It is efficient and fast. To help gauge the efficiency of the above algorithm in general terms, a few standard metrics of computational workload for typical tasks in linear algebra will be reviewed. One common unit of computational work is thefloating point operation, orflop, which is defined as the computational work required to perform a multiplication of two real numbers and addition of two real numbers. Suppose that  is the computational cost of a given algorithm measured in flops. An algorithm is said to require on the order of the function

is the computational cost of a given algorithm measured in flops. An algorithm is said to require on the order of the function  , or

, or  , flops whenever

, flops whenever

For many common numerical tasks the function  is some polynomial of

is some polynomial of  . For example, it is easy to show that the dot product of two

. For example, it is easy to show that the dot product of two  ‐tuples requires on the order of

‐tuples requires on the order of  flops. The multiplication of a general, full

flops. The multiplication of a general, full  matrix times an

matrix times an  ‐tuple requires on the order of

‐tuple requires on the order of  floating point operations. The solution of a set of

floating point operations. The solution of a set of  linear matrix equations, in comparison, requires on the order of

linear matrix equations, in comparison, requires on the order of  floating point operations when the associated coefficient matrix is full. Additional discussion of computational workload can be found in [18], as well as specifications of cost for various common numerical algorithms.

floating point operations when the associated coefficient matrix is full. Additional discussion of computational workload can be found in [18], as well as specifications of cost for various common numerical algorithms.

This description gives information about the asymptotic cost of an algorithm as  becomes large. The value of the constant is of interest when making finer comparisons of the computational workload. The recursive algorithm above requires on the order of

becomes large. The value of the constant is of interest when making finer comparisons of the computational workload. The recursive algorithm above requires on the order of  floating point operations. In other words, the computational cost grows like a linear function of the number of unknowns. This algorithm is one of the several variants ofrecursive

floating point operations. In other words, the computational cost grows like a linear function of the number of unknowns. This algorithm is one of the several variants ofrecursive

formulations of kinematics and dynamics for robotic systems. The reduction in computational workload that is afforded via recursive

formulations of kinematics and dynamics for robotic systems. The reduction in computational workload that is afforded via recursive  formulations, in comparison to alternatives that require either the multiplication or inversion of full matrices, can be critical in applications involving the robotic system control. This topic will be discussed in further detail in Chapter.

formulations, in comparison to alternatives that require either the multiplication or inversion of full matrices, can be critical in applications involving the robotic system control. This topic will be discussed in further detail in Chapter.

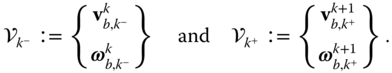

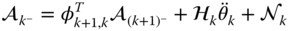

3.4.3 Recursive Calculation of Acceleration and Angular Acceleration

This section derives recursive algorithms for calculating the acceleration and angular acceleration of the bodies in a robot that form a kinematic chain. In Section 3.4.1 the velocities and angular velocities have been collected in the  arrays

arrays

In this section the following derivatives of the velocities with respect to the link frame

will be considered as the unknowns in the recursive formulation

will be considered as the unknowns in the recursive formulation

It is assumed that the vectors  and

and  have been written in terms of components relative to the frames

have been written in terms of components relative to the frames  and

and  , respectively. The

, respectively. The  and

and  notation that describes the basis used to define the components is suppressed in these definitions.

notation that describes the basis used to define the components is suppressed in these definitions.

The entries in the vectors  and

and  do not contain the linear accelerations

do not contain the linear accelerations  and

and  of the points

of the points  and

and  in the base frame. In most applications these accelerations

in the base frame. In most applications these accelerations  and

and  in the base frame are the primary focus of the analysis, not the accelerations in the body fixed frames. However, the linear accelerations in the base frame can be calculated from the entries in

in the base frame are the primary focus of the analysis, not the accelerations in the body fixed frames. However, the linear accelerations in the base frame can be calculated from the entries in  and

and  . The derivative Theorem 2.12 results in

. The derivative Theorem 2.12 results in

However, the vectors  and

and  do contain the angular accelerations in the base frame of the links

do contain the angular accelerations in the base frame of the links  and

and  , since by definition

, since by definition

These calculations can be organized into a pair of  vectors as follows once the derivatives of velocities

vectors as follows once the derivatives of velocities  and

and  are known

are known

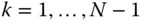

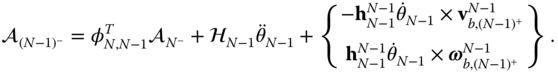

A set of matrix equations analogous to those presented in Theorem 3.4 can be obtained for the derivatives of the velocities and angular velocities of a kinematic chain. These algorithms can be derived using the matrix equation given in the following theorem.

It is important to note that the coefficient matrix

on the right side of Equation (3.43) is identical to that in Equation (3.13). It is the structure of this matrix that enables a recursive calculation of the derivatives of the velocities. Suppose the joint rates  ,

, and the joint accelerations

and the joint accelerations  ,

, are given; the associated velocities and angular velocities for the kinematic chain may be calculated using the recursive algorithm from Figure 3.21. Then, using these results, the derivatives of the velocity may be calculated. The last row in Equation (3.30) does not depend on the other rows, enabling the solution of the equation

are given; the associated velocities and angular velocities for the kinematic chain may be calculated using the recursive algorithm from Figure 3.21. Then, using these results, the derivatives of the velocity may be calculated. The last row in Equation (3.30) does not depend on the other rows, enabling the solution of the equation  for

for  .

.

All of the terms on the right hand side of this equation are known. For example, the equation

may be evaluated immediately since the velocity of the base body is assumed to be given; it is equal to zero when the base  is stationary.

is stationary.

Next,  is calculated from the equation

is calculated from the equation  , so that

, so that

As before, the right hand side of this equation is known since the velocities and angular velocities have already been solved for, along with  . The algorithm continues recursively from the inboard to the outboard joints, until all the derivatives of velocity

. The algorithm continues recursively from the inboard to the outboard joints, until all the derivatives of velocity  ,

, ...

... are known. These steps are summarized in Figure 3.24.

are known. These steps are summarized in Figure 3.24.

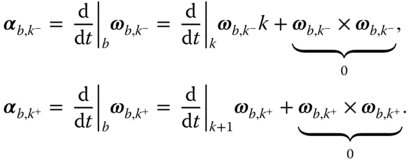

- Find the velocities and angular velocities using the algorithm in Section 3.4.1.

- Iterate from inboard to outboard joints for

, do the following:

, do the following:

- Form the transposed position operator

- Calculate the bias acceleration

- Calculate the derivative of the velocity

- Calculate the accelerations and angular accelerations in the base frame.

- Form the transposed position operator

Figure 3.24 Recursive algorithm for calculation of accelerations and angular accelerations.

The recursive  formulationdoes not impose restrictions on the selection of the degrees of freedom as does the DH convention. For example, while it is always the case that the axes

formulationdoes not impose restrictions on the selection of the degrees of freedom as does the DH convention. For example, while it is always the case that the axes  define the directions of the degrees of freedom in the DH convention, the directions of the degrees of freedom

define the directions of the degrees of freedom in the DH convention, the directions of the degrees of freedom  in the recursive

in the recursive  formulation can be any axes. In fact, it is an easy matter to solve for the velocities, accelerations or forces using the recursive

formulation can be any axes. In fact, it is an easy matter to solve for the velocities, accelerations or forces using the recursive  formulation for a system whose kinematic variables have been selected in accordance with the DH convention; the only modification required is to reorder the degrees of freedom and the frames used in the recursive order

formulation for a system whose kinematic variables have been selected in accordance with the DH convention; the only modification required is to reorder the degrees of freedom and the frames used in the recursive order  formulation. This is shown in the next example.

formulation. This is shown in the next example.

3.5 Inverse Kinematics

The general tools in Chapter and the early sections of this chapter can be employed to derive fast and systematic methods for the analysis of problems offorward kinematics. As discussed in Chapter , however, applications abound in which problems ofinverse kinematics must also be solved. The synthesis of the flapping motion based on camera measurement of the wings of a bird is an example of a problem of inverse kinematics. There are several reasons why problems of inverse kinematics can be significantly more difficult to solve than those of forward kinematics for a kinematic chain. First, it can be difficult to determine if there exists any solution at all to some inverse kinematics problems. Second, even if there is a solution, the solution may not be unique. Third, it is not uncommon that the solution of an inverse kinematics problem is determined by the roots of a transcendental, nonlinear set of algebraic equations for which the determination of the roots of these equations is far from trivial. Fourth, many inverse kinematics problems arise as part of a more complex task. If a controller must be designed to drive a robotic arm so that the tool follows some prescribed trajectory, corresponding perhaps to a weld on an automotive frame, it may be necessary to solve the inverse kinematics problem every few milliseconds. The solution of the tracking control problem uses the solution of the inverse kinematics problem. In fact, the solution of the inverse kinematics problem is also often used during the robotic design process. These optimization based techniques can be used effectively in design studies, where the solution of the inverse kinematics problem need not be solved in real time.

Because of these considerations, two general approaches, analytical and numerical, to the solution of inverse kinematics problems will be studied in this section. The advantages of analytical methods are that they are faster to execute and are therefore amenable to applications, wherein the inverse kinematics problem has to be solved inreal time. These applications include problems of tracking control in which the inner loop defines a set of joint variables that must be tracked, and the outer loop induces feedback that depends on the tracking error. This control architecture is quite common in robotic applications and is discussed in some detail in Chapter . However, an analytical solution cannot be guaranteed in the general case for a kinematic chain. In contrast, numerical techniques are significantly more general than analytical techniques, but can be much more time consuming than the analytical methods owing to the use of an iterative approach to estimate the solution, as opposed to a deterministic approach to calculate the solution.

3.5.1 Solvability

In the study of inverse kinematics, the goal is to determine the values of the joint variables defining a manipulator configuration that will place the end effector at a desired position and orientation. If the manipulator arm is a kinematic chain, the solution is usually given relative to the base. In particular, if the DH parameterization is used, the solution is specified in terms of the link displacements, offsets, twist, and rotation angles, and by the location of the base frame in the world coordinate system.

In considering a general inverse kinematics problem, it may always be the case that no solution exists for a specified target end effector location and orientation. For example, suppose the kinematic chain is constructed solely of revolute joints and has a maximum total length while “stretched out” of 1 m. Now imagine that the target location and orientation of the end effector is sought at a distance 2 m from the base of the robotic arm. There is no choice of joint variables that can attain the desired end effector location and pose due to the geometric limitations of the robotic arm. In this case the desired, or target, position and orientation of the end effector is not feasible or consistent for the robot arm under consideration. Clearly, the desired pose of the end effector must lie in the workspace of the robotic arm, or the inverse kinematics problem is inconsistent or unfeasible. The general study of which end effector poses yields well posed inverse kinematics problems that can be quite subtle and falls under the topic of accessibility, attainability, or controllability in nonlinear control theory 10,33,41.

Suppose an  degree of freedom kinematic chain is under consideration that consists of revolute and prismatic joints. The inverse kinematics problem seeks to determine the values of joint rotations or displacements for

degree of freedom kinematic chain is under consideration that consists of revolute and prismatic joints. The inverse kinematics problem seeks to determine the values of joint rotations or displacements for  , given the numerical value of the homogeneous transformation matrix

, given the numerical value of the homogeneous transformation matrix  . If the dimension of the task space is

. If the dimension of the task space is  , then there are

, then there are  independent equations with

independent equations with  unknown joint variables in this formulation. Any of the following three situations may arise:

unknown joint variables in this formulation. Any of the following three situations may arise:

-

: There are enough equations to solve for the unknowns, if they are consistent. However, these equations are nonlinear. Hence, there may be one or more solutions to the inverse kinematics problem. The number of solutions is finite.

: There are enough equations to solve for the unknowns, if they are consistent. However, these equations are nonlinear. Hence, there may be one or more solutions to the inverse kinematics problem. The number of solutions is finite. -

: The number of robot degrees of freedom is not sufficient to account for all possibilities of end effector position and orientation. Hence, the inverse kinematics problem may or may not have a solution.

: The number of robot degrees of freedom is not sufficient to account for all possibilities of end effector position and orientation. Hence, the inverse kinematics problem may or may not have a solution. -

: There are more degrees of freedom than required to provide the desired end effector position and orientation. Hence, there may be an infinite collection of solutions to the inverse kinematics problem. In this case the robotic arm is said to be redundant.

: There are more degrees of freedom than required to provide the desired end effector position and orientation. Hence, there may be an infinite collection of solutions to the inverse kinematics problem. In this case the robotic arm is said to be redundant.

The cases discussed above are illustrated in the following example, which clarifies the qualitative differences between the three cases.

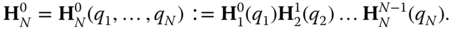

The inverse kinematics problem studied in this chapter can be developed in terms of homogeneous transforms. It is assumed that a robotic manipulator that has the form of an  degree of freedom kinematic chain is given. The goal is to position the terminal (or tool) frame of the arm at a prescribed position and orientation in the workspace. The position and orientation of the tool frame in the ground frame is represented by the usual product of homogeneous transforms

degree of freedom kinematic chain is given. The goal is to position the terminal (or tool) frame of the arm at a prescribed position and orientation in the workspace. The position and orientation of the tool frame in the ground frame is represented by the usual product of homogeneous transforms

Each homogeneous transform  is a function of one of the joint variables

is a function of one of the joint variables  , and the composite transform

, and the composite transform  that maps the tool frame

that maps the tool frame  to the ground frame 0 is a function of all

to the ground frame 0 is a function of all  joint variables. Each joint variable

joint variables. Each joint variable  is either a rotation angle or displacement, depending on whether it corresponds to a revolute or prismatic joint.

is either a rotation angle or displacement, depending on whether it corresponds to a revolute or prismatic joint.

The inverse kinematics problem assumes that a desired location and orientation of the tool frame is given that is represented by a homogeneous transformation  . A solution

. A solution  of the inverse kinematics problem therefore must satisfy the matrix equation

of the inverse kinematics problem therefore must satisfy the matrix equation

Since the last row of this matrix is identically equal to 0 or 1, there are 12 scalar equations in this matrix equation. There are  unknowns. Nine of these scalar equations arise from the rotation matrix that appears as a submatrix of the homogeneous transformation, and three of these scalar equations that arise from the offset vector contained in the homogeneous transform. As discussed in Chapter , a general rotation matrix is characterized by three independent angles; therefore, six of the nine scalar equations arising from the rotation matrix six are redundant. This matrix equation can generates at most six independent scalar equations that relate the joint variables to the pose of the end effector.

unknowns. Nine of these scalar equations arise from the rotation matrix that appears as a submatrix of the homogeneous transformation, and three of these scalar equations that arise from the offset vector contained in the homogeneous transform. As discussed in Chapter , a general rotation matrix is characterized by three independent angles; therefore, six of the nine scalar equations arising from the rotation matrix six are redundant. This matrix equation can generates at most six independent scalar equations that relate the joint variables to the pose of the end effector.

Two general strategies will be studied to solve this inverse kinematics problem: analytical and computational methods. Analytical methods are investigated in Section 3.5.2, while the computational approaches are presented in Section 3.5.3.

3.5.2 Analytical Methods

Analytical methods for solving inverse kinematics problems often are tailored to a particular problem at hand, and a specific strategy adopted for one robot may not be applicable to a different robot. However, general templates have been developed to guide the construction of analytical solutions based on algebraic or geometric strategies. These approaches are discussed in Section 3.5.2.1 and 3.5.3, respectively.

3.5.2.1 Algebraic Methods

This section presents an algebraic method for generating a solution of an inverse kinematics problem based on a guideline that loosely applies to all robots. Although it does not prescribe a specific answer for a given problem, it guides the process by which an analytical solution is developed.

For an  degree of freedom manipulator, the steps for constructing an analytic solution of an inverse kinematics problem are as follows:

degree of freedom manipulator, the steps for constructing an analytic solution of an inverse kinematics problem are as follows:

- Solve the forward kinematics problem: (i) assign the DH parameters and link coordinate frames, (ii) derive the homogeneous transformation matrices

, and (iii) obtain

, and (iii) obtain  as a function of joint variables.

as a function of joint variables. - Symbolically compute the following matrix equation:

and equate corresponding elements of the matrices on both sides of the above equation to search for “simpler” trigonometric equations for solving joint variables.

- If required, continue repeating this process (multiplying each side by the next joint's inverse homogenous transform), until the joint variables are solved:

As discussed, the algebraic approach summarized above does not prescribe a specific set of equations that must be solved at each step of the procedure. The structure and sparsity of the homogeneous matrix equations in each step must be studied carefully to determine specific relationships between joint variables and end effector pose. This process is illustrated in the next two examples that illustrate the use of the methodology for simple robotic manipulators.

In addition, given the large number of trigonometric functions present in many of these examples, a shorthand is used. The functions  and

and  will instead be represented as

will instead be represented as  and

and  , respectively.

, respectively.

Table 3.4 DH parameters for the robotic arm.

| Joint | Displacement

|

Rotation

|

Offset

|

Twist

|

| 1 | 0 |

|

0 |

|

| 2 | 0 |

|

|

0 |

| 3 |

|

|

|

0 |

The analytical techniques employed in this book are based on the fact that many commercially available robotic manipulators terminate in a spherical wrist that carries a payload or tool. This general topology allows the inverse kinematics problem to be decomposed into two sub‐problems: (i) positioning the wrist center, and (ii) orienting the end effector through the wrist. The decomposition of the general inverse kinematics problem into the independent problems of locating the wrist center and orienting the tool frame is known askinematic decoupling.

The following two examples illustrates this process for six degree of freedom robotic manipulators.

3.5.2.2 Geometric Methods

An alternative approach for generating the analytical model for a kinematic chain's inverse kinematics is the geometric approach. In many kinematic chains, equations for one or more of the kinematic variables may be found using geometric and/or trigonometric identities based on the structure of the robot. Common identities used in this process include the laws of sines and cosines and the Pythagorean theorem. However, this approach depends entirely on the geometry of a given kinematic chain and cannot be generalized into a systematic algorithm for automated analysis. The following provides an example of geometric analysis on a three degree of freedom kinematic chain.

3.5.3 Optimization Methods

The last example showed that kinematic decoupling can be used to derive the solution of inverse kinematics problems via analytical methods. Still there exist many other robotic system and inverse kinematics problems that are not amenable to analytic solution. Such problems can often be tackled by using numerical techniques for the approximate solution of optimization problems. There is an extensive literature that studies these techniques, and most introductory numerical methods courses taught in an undergraduate curriculum include some discussion of the fundamentals. The details of the underlying numerical algorithms will not be covered in this book, but rather concentrate on casting the inverse kinematics problem in a canonical form. Any of a variety of standard approaches can then be used to approximate the solution of the inverse kinematics problem.

The classical problem ofoptimization theory that concerns this book seeks to find the extremum of a real valued function  over some admissible subset

over some admissible subset  . The extrema of the function

. The extrema of the function  are the set of points at which the function has a local minima or local maxima, or at which it has an inflection point. The vector

are the set of points at which the function has a local minima or local maxima, or at which it has an inflection point. The vector  is said to be alocal minimizer of

is said to be alocal minimizer of  if there is a neighborhood

if there is a neighborhood  containing

containing  such that

such that

for all  . If the neighborhood

. If the neighborhood  can be taken to be all of

can be taken to be all of  ,

,  is aglobal minimizer of

is aglobal minimizer of  over

over  . The form

. The form

can be used to designate the minimizer of  over the neighborhood

over the neighborhood  . Equations (3.65) or (3.66) state a problem ofconstrained optimization. It is required that the optimal

. Equations (3.65) or (3.66) state a problem ofconstrained optimization. It is required that the optimal  exists in the admissible set

exists in the admissible set  . If the admissible set

. If the admissible set  , the problem is anunconstrained optimization problem. The general conditions that dictate when the extrema of a given function

, the problem is anunconstrained optimization problem. The general conditions that dictate when the extrema of a given function  exist and when they are unique can be very complex. The derivation of equations that characterize the solutions of suchoptimization problems can also be found in the literature. The interested student is referred to the large number of good references on this subject, typical ones being [35] or [47]. This book aims to cast the problems of inverse kinematics into the form of the problem in Equation (3.65) or (3.66).

exist and when they are unique can be very complex. The derivation of equations that characterize the solutions of suchoptimization problems can also be found in the literature. The interested student is referred to the large number of good references on this subject, typical ones being [35] or [47]. This book aims to cast the problems of inverse kinematics into the form of the problem in Equation (3.65) or (3.66).

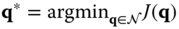

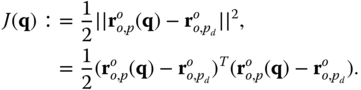

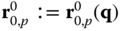

The first step in posing the inverse kinematics problems as an optimization problem consists of defining an appropriate error or cost functional that must be optimized. For example, to solve an inverse kinematics problem and find the joint variables  that locate a point

that locate a point  fixed on the robot at some desired point

fixed on the robot at some desired point  in the inertial frame, the cost functional

in the inertial frame, the cost functional  could be defined to be

could be defined to be

In this expression the position  of the point

of the point  on the robot depends on the value of the joint variables

on the robot depends on the value of the joint variables  , but the position of the desired point

, but the position of the desired point  does not. This quadratic function is common in applications, but many alternative functions could also be used. In general, a good cost functional is constructed so that

does not. This quadratic function is common in applications, but many alternative functions could also be used. In general, a good cost functional is constructed so that

- (1) (1) it is a differentiable function of the unknowns

,

, - (2) (2) it is non‐negative, and

- (3) (3) it has a minimum value at the desired configuration.

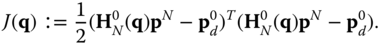

Ideally, the minimum value is unique, but many problems of inverse kinematics are structured such that there are many possible solutions. Example 3.15 discussed below is of this type. Differentiable cost functions are chosen, if possible, because many algorithms have been developed that can exploit derivatives in approximating the solution of the extremization problem. Generally speaking, smooth cost functions lead to more efficient solution techniques. Both the theory and collection of numerical methods for optimization of smooth functionals are more mature and well developed than that for non‐smooth functions. In addition, the cost functional can often be expressed efficiently in terms of the specialized kinematics formulations already developed for robotic systems. If  are the homogeneous coordinates of point

are the homogeneous coordinates of point  in the tool frame

in the tool frame  and

and  are the given homogeneous coordinates of the desired point

are the given homogeneous coordinates of the desired point  in the ground frame, the cost functional

in the ground frame, the cost functional  can be written as

can be written as

For this choice of the cost functional, the problem of inverse kinematics is that of finding  where

where

for some neighborhood  where

where  is the set of admissible joint variables.

is the set of admissible joint variables.

3.5.4 Inverse Velocity Kinematics

Just as inverse kinematics allows the calculation of joint angles given an end effector position and orientation, inverse velocity kinematics allows for the calculation of joint angle velocities based on a given end effector velocity and angular velocity. The solvability of the inverse velocity kinematics problem depends on the number of specified task space velocity parameters  and the number of

and the number of  joint velocities to be calculated. As with the inverse kinematics problem, there are three cases to consider:

joint velocities to be calculated. As with the inverse kinematics problem, there are three cases to consider:

-

, where the robot does not have a sufficient number of independent joint variables to provide all possible end effector movements. As a result, the inverse velocity kinematics problem may not have a solution.

, where the robot does not have a sufficient number of independent joint variables to provide all possible end effector movements. As a result, the inverse velocity kinematics problem may not have a solution. -

, where the robot possesses more degrees of freedom than are required to generate the desired end effector solutions. As a result, there are infinite solutions to the inverse differential kinematics problem. As before, this case is called redundancy.

, where the robot possesses more degrees of freedom than are required to generate the desired end effector solutions. As a result, there are infinite solutions to the inverse differential kinematics problem. As before, this case is called redundancy. -

, where the robot possesses equal numbers of degrees of freedom and end effector workspace.

, where the robot possesses equal numbers of degrees of freedom and end effector workspace.

Unlike inverse kinematics, the mapping from the joint angle velocities into the end effector velocity and angular velocity is known to be linear. As discussed in Section 3.3.5, this mapping is called the Jacobian matrix. When  , the Jacobian matrix is square. If the determinant of this matrix is non‐zero, the matrix is invertible, providing a straightforward solution for the joint angle velocities, such that

, the Jacobian matrix is square. If the determinant of this matrix is non‐zero, the matrix is invertible, providing a straightforward solution for the joint angle velocities, such that

The Jacobian matrix represents the geometry of the robotic arm at a given configuration. At some configurations, the determinant of the Jacobian may become zero. By definition, the inverse of a matrix does not exist if that matrix's determinant is zero. The geometric cause of a Jacobian's determinant becoming zero is singularity.

3.5.4.1 Singularity