Leisure ideals and values

In the previous chapter, we explored several ways in which leisure is used and could be used for existential self-determination; we had an explicit focus on edgework. In this chapter we will look at the power of leisure in processes of co-creative, communal stimulation of well-being effects, i.e. the effectiveness of leisure at the systemic level, group level, or societal level.

We do realise that this might be seen as a modern (rather than post-modern) perspective, perhaps even an idea that could emerge from the Aristotelian tradition. We do not shy away from that – consider the central role of eudaimonia in Chapter 5 on ethics. However, our point, in the previous chapter as well as this one, is that postmodern liquidity in combination with the body- and experience-focused leisure practices prevalent in today’s (Western) society open up new opportunities for idealism about the power of leisure.

Leisure policymakers, practitioners and scholars are certainly no strangers to a fair bit of idealism when it comes to the potential of leisure to have positive effects. We too readily accept responsibility for any such attitude. Once more we refer back to Chapter 5 on leisure ethics, where we claimed that leisure as art of life implies self-development, responsibility, wisdom and a strong moral centre, with eudaimonia as a life goal.

Art of life, in short, means to live well and do good. From the perspective of leisure, living well means having meaningful experiences, and doing good means creating meaningful experiences with and for others. This turns engaging in leisure activities into implementing a kind of aesthetic idealism: one can improve one’s own life by turning it into a work of art, and as such that life can serve as a source of meaningful experiences for others as well.

This is, in its core, a moral claim, in at least two ways. First, there is a meta-level normativity in play here in the sense that, according to an art-of-life attitude, it is possible to design your life in such a way that it becomes ‘better’, and leisure can be a very potent source of inspiration and activity to operationalise such an attitude. Second, an important aspect of the purported effectiveness of leisure in stimulating art-of-life-related endeavours is that leisure (e.g. sports participation) influences the development of specific moral beliefs. One of the most recognisable exponents of this ideal is the World Leisure Organization’s Charter for Leisure (World Leisure Board of Directors 2000).

Article 4 of the charter is most explicit in formulating the idealistic, well-being-directed agenda underlying the World Leisure Organization’s policies: ‘Individuals can use leisure opportunities for self-fulfillment, developing personal relationships, improving social integration, developing communities and cultural identity as well as promoting international understanding and co-operation and enhancing quality of life.’

The underlying idea of the positive effects of leisure and the right that people have to leisure can be found in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Content-wise, it is inspired by the ‘Olympic Ideal’. One of the fundamental principles of the Olympic ideology is that sports can stimulate healthy living, not just physically but also mentally and morally. Sports, then, can help promote peace and harmony throughout the world. The Olympic ideology was initially developed by Pierre de Coubertin, the ‘father’ of the modern Olympic Games, in reaction to the French educational system of the late nineteenth century, which largely ignored the benefits of physical education. De Coubertin suggested that there would need to be a close correlation between physical and moral development, which was in line with the English ‘muscular Christianity’ doctrine: physical exertion is good for body and mind – particularly morality. We can still see the echoes of these developments in the more traditional forms of sports ethics, which is basically a form of virtue ethics: specific moral values are considered to be particularly virtuous (e.g. courage, helpfulness, honesty, fairness), and there is thought to be a strong correlation between practising sports and acquiring these values (Tamboer and Steenbergen 2004).

However, the sports world is quite a bit more complex than is presupposed in this naive picture. One of the reasons is that the context within which sports (or a particular sport) is interpreted is always already value-loaded. For instance, sports activities are very rarely goals unto themselves, but are always already connected to other goals: health gains, pedagogical development, setting moral examples, public relations (as in marketing for a product, or promoting nationalistic pride), or simply and bluntly making money. This profound contextuality and organisational interconnectedness increases the ethical complexity of these activities.

A similar moral and organisational complexity can also be seen in leisure as a whole. The connection between engaging in leisure activities and achieving the purported positive goals is not straightforward. As we saw in our earlier historical explorations in this book, the classical leisure concept (broadly conceived) developed and used throughout much of the twentieth century outlined it as a domain of more-or-less freely chosen activities, contrasting it with work as an economic activity – producing money and goods. Several leisure scholars then saw a further conceptual distinction within the broad leisure concept, isolating ‘free time’ – the domain of entertainment – from actual ‘leisure’ (narrowly conceived) – serious, self-development-focused activities. Rademakers (2003: 12) mentions scholars such as DeGrazia, Huizinga, Pieper and Dumazedier supporting this perspective in various ways. ‘Serious leisure’, of course, has become a proper category of study among leisure scholars – as we noted before, Robert Stebbins (2007), for instance, has done a lot to improve our understanding of the effects of a dedicated and serious investment of time and effort into a leisure practice like a hobby or a sport.

However, undergirding the conceptual distinction between free time and leisure, and situating ‘leisure’ towards the serious end of the spectrum, is a value judgement akin to the distinction between highbrow art (as an expression of advanced aesthetic sensibilities and artistic skill) and lowbrow art (as a democratised, perhaps even vulgarised, potentially hedonistic practice focused on the consumption of entertainment products). Saying that ‘proper’ leisure is to be serious and constructive by definition indicates a sorting criterion for leisure practices based on Bildung idealism – i.e. seeing leisure as an active component in a person’s personal, intellectual and moral maturation. In this scenario, the ‘best’ leisure activity is an activity that actively contributes to personal growth.

When focusing on individuals as leisure consumers, using the Bildung ideal as a sorting criterion for leisure practices might very well result in such a hierarchical structure (with serious leisure ‘on top’). However, there are two remarks we wish to make. First, leisure practices often emerge in rather more complex arrangement of stakeholders, involving not only leisure consumers, but also leisure producers, or even extensive networks of leisure producers. Commercial leisure producers, for instance, might suggest an entirely different hierarchy, favouring criteria that are very different from those stemming from Bildung-idealism. For instance, from a business perspective, ‘low-level’ entertainment is one of the more economically relevant aspects of leisure – entertainment (presented in a particular organisational/logistic context) is what event organisers sell to their consumers, and revenue potential and aesthetic quality of entertaining performances are not necessarily positively correlated. And for the artist performing at such an event, the performance is a marketable product, and possibly also a meaningful form of creative expression. Here we can see that the success criteria, so the standards of what would count as ‘better’ or ‘more valuable’, can differ per stakeholder or per situation, and each stakeholder might consider several criteria to hold at the same time. At the very least, this means that a generalistic Bildung-value-based distinction between lowbrow entertainment and highbrow leisure does not reflect the way in which all stakeholders might value a particular leisure practice.

The second remark concerns the roles that different stakeholders assume in the creation of leisure practices. A simple producer-consumer dialectic is no longer appropriate to characterise the interaction complexity involved in creating leisure practices. Because leisure is considered to be so important as a medium for the expression and constitution of personal identity and the realisation of well-being, placing experience at the centre of a conceptualisation of leisure is a defensible position – we have certainly been doing so throughout this book. The most important thing that is created in many leisure activities is not the event (as a collection of occurrences) itself, but the shared experience that emerges in the interaction of all participants: the event’s logistic context created by the organiser, the experience components offered in the artist’s performance, and the appreciation and participation of the attendees that constitute the atmosphere of the event.

In addition, the dynamic nature and horizontal hierarchy of postmodern society (as explored in earlier chapters), plus the technological possibilities to connect to many different people when and where one desires (see Chapter 6), means that leisure activities occur less frequently in classic ‘consumer vs producer’ structures, instead emerging as self-organising and/or co-creative systems. As said, modern technology (e.g. social networks) is a powerful catalyst of this network character of leisure practices.

These considerations caused Richards (2010) to reconceptualise a person in a leisure situation not as an autonomous agent choosing activities, but as the intersection of various interactive practices, where these practices have a shared centre – usually an informal involvement in something playful or creative. These interactive practices are the leisure activities, and seeing them this way helps focus on the dynamic nature of leisure activities, rather than understanding the individuals or organisations as static entities: each activity is created by different leisure networks. In a single day, someone can partake in several very different leisure networks: from the localised and institutionalised gym she visits before work, the impromptu lunchtime walk in the park with a colleague, the night on the town with friends facilitated through online social networks, and the flash mob at the train station that is intended as marketing for a new play that is about to open in the local theatre.

There is a lot of potential in these leisure practices and networks to realise idealistic goals, but it is, sadly, not a simple two-step process – i.e. (step 1) apply leisure; (step 2) results! – to bring this potential to fruition. However, in the rest of this chapter, we will make some suggestions about what we can know and do.

Health and leisure-based social innovation

Particularly if we take the tack that leisure and art of life are closely related, we could say that leisure comprises a great variety of activities that we engage in of our own volition to make our life better, more fun and/or more beautiful. In a sense, leisure means stimulating well-being through events, the arts, sports, volunteer work, etc. In Bouwer and Van Leeuwen (2013), we already isolated this as a core aspect of leisure: the (relative) freedom to look for inspiring ideas and experiences, to be creative or to stimulate creativity, and/or to look for spiritual fulfilment, often in a social setting. Leisure can be about fun and exploring freedom, but can also be about improving the quality of life. This means that at the centre of it all, there is often a strong drive in leisure to improve personal and communal well-being. And specifically, speaking about what we can do with leisure to stimulate well-being, we stated: ‘Leisure tools (i.e. meaningful experiences by way of art, events and other creative and playful interactive encounters) can facilitate meaning-directed attunement processes, stimulating shared responsibility and the co-creation of values in a social/collaborative/interactive network’ (2013: 594). This, in a nutshell, is the dynamic that we will explore in the remainder of this chapter.

In the previous chapter, we found that leisure can be a domain within which one can become the governor of one’s own well-being. The murderball example in particular showed how people can explore activities not in terms of limitations (e.g. due to illness or injury), but in terms of remaining (or new) possibilities that they have in a particular context. We will now expand this leisure-centric approach more explicitly to social systems, rather than individuals striving to improve personal well-being, which we mainly focused on in the previous chapter.

An extremely complex but also very important context for which we believe this idea to be relevant is the healthcare sector, or the idea of health and well-being more generally. At least in some developed Western economies, there are certain trends which make a leisure-based approach to well-being very challenging, but also potentially beneficial. Van Leeuwen (2012) describes some of these trends in the Netherlands. In that country, we see that increasing life expectancy and improved diagnostic techniques are starting to increase healthcare demand, while simultaneously capacity at hospitals and care organisations is diminishing due to decreasing budgets. To escape this conundrum, government policy is focused on shunting responsibility for prevention quite explicitly to the personal (rather than the institutional or governmental) level (e.g. by expecting of citizens that they choose a healthy lifestyle). If the need for healthcare intervention does arise, organising the required treatment should take place in small-scale, local networks. Elderly patients, people with physical or mental impairments and the chronically ill are, in many of the cases that can be managed without the intervention of a medical specialist, expected to solve problems themselves, primarily by organising health support in their own social support networks (family, friends, neighbours, etc.).

What we see here is a system in transition. The government intends a transformation to take place, from the old, reliable welfare state to a new, self-supporting network in the form of a ‘participation society’, where the initial impulse in case of a problem (e.g. elderly parents needing assistance with everyday tasks) is not to ask the state or its institutions for help (e.g. put them in a subsidised rest home), but to attempt to solve one’s own problems first (e.g. children, neighbours and friends taking over some of the care tasks needed to allow these people to stay in their own house). This transition is a complex process, because some of the underlying social system resists this imposed change: people do not necessarily want this additional responsibility for autonomous problem-solving, especially if the perceived reason is government budget cuts. A rational, top-down approach, i.e. the government explaining the reasons for this policy, is not necessarily effective to overcome this resistance to change.

Zuboff and Maxmin (2004) suggest that this transition does in fact align with how people nowadays consume: they are not as susceptible any more to overt top-down manipulation attempts as is standard in marketing campaigns, or the government telling them what they should do or like. Instead, consumers nowadays are much more world-wise and wily, know what possibilities are out there (e.g. because of the Internet) and demand a solution that is tailor-made to their specifications. We can understand this as a symptom of the experience economy: people need to feel intrinsically motivated to put in the effort and accept this new situation that includes increased workload and expanded set of responsibilities. Given this array of developments and policies, there is an explicit need for innovative concepts and solutions that both safeguard (and, if possible, improve) quality and improve (cost-)efficiency of health- and well-being-related processes. What might work here, however, is a bottom-up stimulation of co-creation, problem-solving, network formation, optimism and enthusiasm – let’s call it the ‘crowdsourcing of well-being effects’.

This is not an easy task, especially considering the fact that health(care)-related processes are complex, difficult to predict and not always (purely) rational. Plsek and Greenhalgh (2001) state that even a normal work day of an ordinary general practitioner might contain a string of activities governed not by rational, step-by-step processes, but by unpredictability (e.g. when the next emergency will occur), changing plans (e.g. cancelled appointments), the need to dynamically adapt treatment approaches (e.g. an elderly patient needing a listening ear rather than medical treatment, leading to a much longer consultation and a missed lunch) and irrational, but powerful and valid emotions (e.g. patients who are scared, colleagues who, based on emotion and habit, refuse to agree to a reorganisation at the hospital). Despite careful planning in advance, there are numerous instances throughout the day in which conflicting interests of various stakeholders cause very complex, unpredictable processes. The unpredictability is exacerbated because these interests sometimes depend on emotional or irrational factors; these factors are extremely difficult, perhaps even impossible to control and/or to plan for.

A similar unpredictability can be seen in the life of patients, especially if we consider not only the patient but also the supporting network surrounding her (as the autonomy-focused policy described earlier would have us do). What we are dealing with, then, is a complex adaptive system. To understand how this works, imagine a school of fish. The school retains its general shape not due to some preplanned, rationally designed and shared strategy, but because the individual fish are instinctually focused on staying close to one another from one moment to the next. The resultant system is constantly changing at the individual fish level, but largely stays the same at the school level, and there it realises a higher-order goal, i.e. to keep (most of) the fish safe. If something disturbs the normal dynamics of the system, i.e. a predator appears and swims into the school, one or more fish may be caught and eaten, but after the predator leaves, the school will reorganise itself into the optimal bulbous shape to keep most of the fish safe.

The dynamic and reorganisational capacity is the key feature here, if we compare it to, say, a family. The members of this family get on with their daily lives, individually and collectively. Imagine a disturbance to this system: suppose the mother of the family is in a car accident and is subsequently confined to a wheelchair. Now this system, while obviously still a family, also becomes something else: a patient plus her support network. How can such a system, with all those engrained habits and ideals that sometimes align, but sometimes also clash, reorganise itself after this disturbance? This family will need to find new behavioural and social interaction formats for the patient herself, and for her support network (in an extended sense also including family, friends, etc.). Many practices that were a particular way before the accident will change, from how the mother cares for her children, to her job and leisure activities, to perhaps practical changes that need to be made to allow her wheelchair in the house, to how her children and partner need to adapt to these changing circumstances, etc. This system will, hopefully, self-organise in a different way that is adapted to these new circumstances, but will be the same in at least one important way: the individual behaviour of the family members and the collective dynamics of the system will be focused on keeping itself safe and as happy as possible. However, the circumstances within which this needs to happen, and the kinds of strategy that are likely to be effective, are now quite different.

This, of course, is an example of a very serious and far-reaching life transition, and hopefully as few people as possible will need to ever deal with something like it, but there are other such transitions that are more common – sometimes negative, sometimes positive – but also indicative of major change. These can include a disabling accident or illness, becoming a pensioner, becoming a parent, losing a job or starting a new one, moving out of one’s parents’ house to start one’s own life, and so on. At a higher aggregation level, we could be thinking of the company one is working for changing its policies, philosophies and values, requiring a new way of working of its employees; the influx of people with a different cultural background to an established neighbourhood; or, in the example that we started out with, a whole society needing to change the way it thinks about health and the healthcare system.

In the healthcare example, we already stated that for such a complex interlocking array of processes, influences and structural dynamics top-down interventions are often ineffective in realising the required change in a durable form. Instead, we suggested, we would need intrinsic, organic, bottom-up stimuli towards self-organisation of solutions to the extant problems. In the example above, we spoke of disturbances to the system (e.g. a family) in a negative sense: the disturbance, an accident and the medical aftermath, was a destructive event. There can, however, also be disturbances to such systems that are positive, that have beneficial effects. This, we suggest, is the deep conviction underlying leisure-based idealism. Sports can improve well-being, is the Olympic ideology as we discussed it at the beginning of this chapter. Given what we have learned in the interim about complex social systems, how can sports, or leisure more generally, actually do that in such a systemic context?

From a leisure policy perspective steeped in the idea that leisure implies artful living and the ideal to increase happiness and well-being, this is an important question that we will address: how can one orchestrate leisure-based ‘disturbances’ (interventions, in the form of activities, events, etc.) to force such a system to reorganise itself in a more efficient and more beneficial (more well-adjusted/adapted) form? Or, more succinctly: how can leisure increase well-being?

In innovation studies, there are various business transformation protocols that attempt to improve processes in a particular way. The approach that we will suggest was inspired by imagineering as a business transformation tool (see, e.g. Nijs and Peters (2002); Nijs (2014); Nijs and Van Engelen (2014)). Below, however, we will develop a more philosophical and conceptual analysis of the social-system-transforming powers of leisure.

What we have (not-so-inadvertently) stumbled upon here is actually a form of social innovation. Social innovation is a catch-all term for attempts to find new concepts and strategies to solve societal problems by employing the creative/innovative capacities of a social system. Instead of designing a rational solution and forcing it, top-down, upon a group of stakeholders (e.g. the employees of a company), the idea is to mobilise the stakeholders (the members of the system that needs to change) themselves and stimulate them to find solutions, bottom-up, that they can intrinsically support. This boils down to the crowdsourcing of solutions (recall that in the healthcare example above we used the phrase ‘the crowdsourcing of well-being effects’). Potential uses of this approach include collective problem-solving – i.e. the co-creation of desired end-states pertaining to socio-economic problems (as suggested above), but also to jumpstart innovation and finding new ideas in a business context.

So, generally, social innovation is about opening up processes to collective creativity – to bottom-up and intrinsic problem-solving instead of top-down solution enforcing. The potential benefits of this approach are that the stakeholders might find creative/innovative solutions, that the stakeholders experience individual and collective empowerment because of shared problem-ownership, and that the task load can be distributed across the system (because all stakeholders are mobilised). However, potential threats include the amplification of the social dimension of the process – that is, because all stakeholders contribute, disagreements, differences in vision, petty squabbles and ethical conflicts might arise.

In the sections below, we will focus on leisure-based social innovation. Specifically, we will focus on the conceptual foundations of how the behaviour of (groups of) people can be influenced by using elements/tools that are also common in leisure (e.g. meaningful experiences, stories, creative expression), or by using leisure events and activities outright as interventions in social systems. That is, as we already claimed in Bouwer and Van Leeuwen (2013), we believe that we can use leisure as a collection of best practices to design for the bottom-up stimulation of co-creation, problem-solving, network formation, optimism and enthusiasm in the face of complex societal problems.

Foundation of the leisure dynamic: narrativity and metaphor

Throughout this book, we’ve made reference to the idea that leisure and narrativity are closely connected. One obvious reason is that in some leisure practices, people explicitly tell stories, e.g. through books, television shows and movies. Events can also tell stories in a more metaphorical sense, as they convey a particular message, value or ideal, and do so by having the visitors cycle through a sequence of experiences as the event progresses. Something similar can be seen in concerts, where the set list is usually designed in such a way to establish tension arcs, to generate excitement and release at appropriate moments.

A deeper reason that leisure and narrativity are connected has to do with an idea that we’ve already referred to (e.g. in Chapter 4): leisure can stimulate or inspire people to change something about their life story. How and why does this work? How can it be the case that telling stories, or using leisure activities with narrative elements, can change how people think and act? In this section, we will explore the importance of narrativity, and the transformative power of metaphors as the core processes of such psychological/behavioural transitions; in the next section, we will expand our focus to include leisure practices and events.

Certainly, stories have been crucial throughout the history of humankind, and continue to be vital to cultural development, and child development. The oldest world views, i.e. the earliest conceptions of the universe as a totality that make some level of sense, were mythological world views, which were mixtures of accounts of actual events and interpretation, in narrative form and transmitted orally. The purpose of these myths was to explain everyday phenomena, the established social order and/or the place of humans in nature, or to provide listeners with life advice. In these myths, metaphors and symbols, narrative (as opposed to factual, objective) formats, and supernatural events involving animism and anthropomorphism were common. The Presocratic philosophers such as Thales, Anaximander, Anaximenes, Parmenides, Heraclitus and Pythagoras, the first of whom became active in the seventh century bc, supplanted this myth- and story-based approach to explaining the world with a much more methodical, structured, proto-scientific understanding of the universe: they started applying reason, developed proto-scientific cosmologies (usually involving a first principle or essence) and invented mathematics and atomism. These were the beginnings of science as we still know it today, with concepts like physical causation, the very idea of an ordered, intelligible universe, and a mathematical and geometric conceptualisation of objects and processes.

Still, stories continued – and still continue – to be extremely important. Surely, in postmodern Western culture, there is a multitude of narratives that confronts us and helps shape our moral and aesthetic sensibilities (as we argued in, e.g. Intermezzo II). Many of these narratives are encountered during leisure activities – watching television shows or movies and reading books, participating in festivals and events that evoke a wide variety of culturally and historically significant narratives (religious holidays, independence day, renaissance fairs, etc.), but also non-fiction media such as news programmes, magazines and newspapers, that commit to particular co-created narratives that are shared and perpetuated, sometimes tongue in cheek, at some level of detail (e.g. the liberal values of Northwestern Europe, the small-town conservative Christian values upheld in the US Midwest).

However, stories are not neutral entities. Just like technological artefacts (see Chapter 6), they have an effect on the user. Van der Sijde (1998) notes that literature, one of the prime carriers of the narrative tradition, is particularly important to help the reader to develop a careful, tentative openness towards the unsayable. The task of literature, Van der Sijde says, following Jacques Derrida, is to use fictionality to invent, show, or hint at ‘the other’. A work of literature, in that sense, becomes like thought experiment, helping to uncover or bring just within reach ideas that previously were unavailable. Just like in thought experiments in science one can extrapolate situations beyond empirical data, predict possible future observations and in general test the coherence of concepts, literature can open minds and expand ideas.

We saw the importance of stories to child development when we discussed Hutto (2009) and his narrative practice hypothesis in Chapter 4. His hypothesis posits the importance of stories for the development of theory of mind abilities (i.e. the ability to understand other people as having mental states). Cohen (1998) makes a similar point, namely that humans develop knowledge in compliance with an appropriate environment. That environment is human culture, and particularly the stories encapsulated in it form what he calls a make-a-human-kit, just as essential as the mother’s womb to the development of a fully functioning human from a small amount of DNA.

We can find the stories for that make-a-human-kit everywhere, also where we would perhaps not expect them – such as in science. Stewart and Cohen (1997), for instance, claim that none of the theories taught at schools or customarily used as explanations for observations in general parlance, are actually ‘true’, in most strict meanings of that concept. For example, in elementary school we explain the colours of the rainbow in terms of the refraction of rays of sunlight. As children grow older they might grow to be ready for a more sophisticated explanation involving raindrops acting like little prisms. The next stage in scientific sophistication comes when we explain that light does not consist of rays, but electromagnetic radiation at various wavelengths. Then we say that this radiation is actually to be understood as quantum wave-packets called photons. And then we explain that light can act either ‘wave-like’ or ‘particle-like’ in different contexts…. And so on. This sequence of ever more complex and sophisticated explanations does not bottom out at the indisputable, ultimate, eternal truth.

This is not necessarily a bad thing. Instead of needing the theories we share with each other to be objectively true, Stewart and Cohen claim, we should understand scientific theories as particular kinds of stories – stories that open up the minds of listeners or readers, and as such help create a shared space of the adjacent possible. Compare this to Russian pedagogical scientist Vygotsky’s (1978) ‘zone of proximal development’: sharing behavioural scripts with someone who has developed other/better tricks – e.g. mimicking an older sibling or engaging in games with a parent – will prime a child for her next stage of cognitive development, i.e. learning a new skill or acquiring a new insight.

So: the general idea is that science is a vast collection of a particular kind of stories, and telling these stories helps us synchronise our ideas and concepts in such a way that we can achieve specific concrete goals in practical contexts. This is how we, as a species but also as communities of scientists and professionals, collectively develop more insight and better solutions to practical problems.

Frigg (2010) makes a complementary case for the claim that models in science share characteristics with fiction. For instance, models contain many imaginary elements: the represented real system (e.g. an atom) is not really like the representation (e.g. the Bohr-Rutherford model of the atom, which looks like a tiny solar system with electrons circling the atom’s nucleus). This might appear to negate the ideal of objectivity in natural sciences, but fictional models are actually semantically generative: they help users generate new knowledge and insights, exactly because of this fictional content. Users are ‘invited’ to fill in the blanks and extrapolate, just like we do in stories where we attribute reasons, motivations, values and thoughts to fictional characters in accordance with the rules that apply as determined by the story’s internal logic. Furthermore, the fictionality of models creates the freedom to execute thought experiments: ‘what would happen if we changed X, or did Y?’

However, despite these narrative elements, scientific theories and models do differ from ‘proper’ stories. The key feature is that stories express ideas within a particular personally meaningful context. The meaning of a particular story changes as society changes, and/or the context within which particular stories are intended to be used changes. Zipes (1993), for instance, offers an intriguing analysis of the many forms of the fairytale Little Red Riding Hood, the oldest versions of which were considerably more gruesome than the version most of us today are familiar with, which is a thoroughly sanitised version invented by the Brothers Grimm. In the original context (the middle ages, rural Europe, common people telling each other campfire or tavern stories), the original shock elements (cannibalism, an underage girl removing all her clothing, and the swift but quickly forgotten murder of the grandmother betraying a misogynistic attitude) allowed the storyteller and his audience to co-create a particular meaning of that story, because in that setting, it fitted in with expectations.

This contextualised co-creation of meaning works if there is a kind of resonance of the story and the listener. Fulford (1999: 6–7) says that:

we will see [the events in a story] in the light of our own principles – because stories inevitably demand ethical understanding. There is no such thing as just a story. A story is always charged with meaning, otherwise it is not a story, just a sequence of events…. Stories survive partly because they remind us of what we know and partly because they call us back to what we consider significant.

That is, stories ‘work’ because they can connect to something that is personally significant to the listener. McGinn (1997) adds to this by making a distinction between an objective text (e.g. a scientific research report) which can provide clear-cut, reliable information, and a (subjective) story, which can allow the reader/listener to identify with the protagonist, to experience something by interpreting the actions and events in his own way. This act of interpretation then helps to extract the lesson from the story, e.g. a morsel of moral advice.

The fact that stories draw people in, that they invite participation and co-creation of meaning, is also the key to the transformative power that stories can have. We explored the narrative character of personal identity in Chapter 4: DeGrazia (2005), it was said, defined self-creation or self-management as the autonomous writing of self-narratives. This, and the ideas presented above, explains why storytelling comes naturally to people, and why if one uses a good, gripping tale, it is comparatively easy to get people interested in what one has to say. This is the captivating power of stories.

Once one has that attention, the main active ingredient to explain the transformative power of stories is the metaphor. A metaphor is a linguistic designation of some object, event or state of affairs involving a transformation from one semantic category into another, using a non-literal description. This transformation creates a conceptual link which can serve to highlight certain features of the initial object, event or state of affairs in a salient manner. For instance, as noted in Chapter 4, ‘a mountain of paperwork’ is not a real geological formation, but using those words expresses the monumental task that an office worker who is confronted with said mountain can look forward to. The main objective of using a metaphor is to realise a transformation of the reader or listener, to create an openness in her (recall Van der Sijde’s (1998) description of the power of literature), getting her into a receptive state, within which she can execute the effective interpretative connections herself. Understanding a metaphor can be a meaningful experience, and it can influence the reader’s or listener’s convictions and subsequent actions.

Schön (1979) describes the generative metaphor as a tool to restructure interpretation frames in readers. This reframing action involves a transformation from ‘is’ (description, the actual situation) to ‘ought’ (prescription, what it needs to become). As such, a generative metaphor is a way of generating new, locally effective stories, which is a thoroughly appropriate postmodern practice.

One of Schön’s examples will clarify how this works. Amid a wave of inner-city restructuring projects in the USA in the 1950s, policy documents spoke of these projects using the metaphor ‘blight and renewal’. The meaning here was that the neighbourhood to be restructured was blighted, diseased (the ‘is’), and would need to be cured, not by a piecemeal symptom-based approach, but by renewing, redesigning the whole area (the ‘ought’). This is where a particular kind of description, i.e. the use of this metaphor, already contains an interpretational directionality: it forces the reader to adopt a particular view of what is described, and implies a course of action. In this case: a blight needs to be removed; a disease needs to be cured, and a dysfunctional neighbourhood needs to be torn down and rebuilt. That is the transformation (of meaning, of interpretation, of attitude and consequently of behaviour) that this metaphor was intended to realise.

In the 1960s, this policy was changed, because it was found out that destroying and rebuilding neighbourhoods did not always solve the problems. Instead, the new metaphor ‘restoring the natural community’ was adopted. The idea here was that some neighbourhoods were indeed beyond redemption, but others were low-income communities which had somehow become dislocated (the ‘is’), but which had a strong social fabric that would need to be retained (the ‘ought’). The metaphor’s intended effect in this case was to present the insight that a dislocated shoulder should not be amputated, but needs to be placed back in its natural state, hence the neighbourhood would need to be restored by playing on the strengths of the social network (the ‘ought’).

The lesson here is that a metaphor can serve to frame one’s audience’s experiences in such a way that a particular transition or transformation can appear obvious – and the audience feels intrinsically motivated to follow the suggested action. Similarly, the frame used by the second Bush administration about Iraq, Iran and North Korea in the wake of the 9/11 attacks was to describe these states as an axis of evil. The ‘ought’ was that evil needs to be vanquished and these countries should be fought by any means necessary.

The effectiveness of these metaphors depends on an act of co-creation: the author/artist tweaks the parameters, but the audience needs to engage in active participation, allowing preset ideas and opinions to shift along with the metaphorical transformation. Petrie and Oshlag (1979) highlight that the generative power of what they call interactive metaphors depends on the anomalous character of the meaning that is suggested. Earlier this chapter, we conceptualised health-related systems as complex adaptive systems. Using that idea, we can describe the action of a metaphor as a disturbance or destabilisation of an interpretative system by presenting it with a metaphor that, initially, appears anomalous or dissonant to the reader or listener. This disturbance will force the system (the reader or listener) to find its own restabilisation trajectory: in light of that disturbance, the person (or group of people) needs to change something to find a solution in which everything makes sense again.

Now, an important point that we wish to make is that leisure – exciting events, engaging games, imaginative fantasy – can have a similar destabilising effect, and use similar perspective- and interpretation-shifting strategies, as metaphors. By entering a particular leisure context, someone can feel stimulated to exhibit a profound openness – to new experiences, new ideas and opinions, new relationships and new problem-solving strategies. Leisure, if properly conceived, can facilitate powerful narrative reframing processes. Leisure, in this sense, can be a practical metaphor. We have already seen the outlines of this idea earlier in this book – when we spoke about play, in Chapter 2, and the transformative power of narratives and narrative-based events, in Chapter 4. In the next sections, we will start putting together the elements that we have seeded throughout this book – people having (embodied) experiences in a playful leisure context, in which narratives of various kinds are used to stimulate metaphor-like transformations in attitudes and personal values.

Implementing leisure-based tools: experiences and events

As we have seen so far (e.g. in Chapter 4, and above), we tell stories to understand ourselves and each other, particularly to understand the reasons for our behaviour: these stories help us reconstruct decision-making processes that fit in with narrative aspects of personal identity. We also tell stories of a particular kind – scientific theories – to help ourselves and each other to understand how the world works. How we understand the world, ourselves and each other influences the decisions we make, the values we use to guide our behaviour. The interesting insight, and the point of leverage for the implementation of leisure to change social systems, is that if one can change the story, one might be able to change people’s behaviour. This is the effect that we described in Chapter 4, when we referred to the Breda Redhead Days: people with red hair have many similar experiences (can tell many similar stories about themselves), for instance about social exclusion, or prejudice. The Redhead Days as a leisure event allows these people to change that storyline, because this event uses leisure activities to create a context of (relative) freedom and playful festivity for the participants to rearrange or reinvent personal values, and to change their own life stories.

The examples of the effects of leisure in Chapter 8 focused on self-determination and self-construction, using ‘edgy’ leisure pursuits as a means towards the end of improving personal well-being, of ‘fitting in’ in life, in one’s personal situation. In this chapter so far, we have used examples that focus on health and well-being, but with a more communal, systemic focus. We will now return to this general theme – more specifically: how leisure and leisure-related interventions can help improve health and well-being. This will help us transform the fairly abstract discussion so far into a more practical account.

Earlier, we noted that Plsek and Greenhalgh (2001) defined problems in a healthcare context as problems in a complex system. For these systems, top-down, rational arguments are of limited use in solving problems if the stakeholders are not intrinsically motivated to participate in the solution co-creation process. One possible solution is to focus on quality of experience via co-creation with the primary stakeholders, i.e. the patients.

Bate and Robert (2006) follow this line of thought when they suggest that treating a patient should be much more than mechanically fixing the injury. Rather, they support the idea of experience-based co-design of healthcare processes:

This is not just about being more patient-centred or promoting greater patient participation. It goes much further than this, placing the experience goals of patients and users at the centre of the design process and on the same footing as process and clinical goals.

(Bate and Robert 2006: 308)

And:

The focus is on designing experiences, not processes or systems or just the built environment. In contrast with traditional process mapping techniques, the focus here is on the subjective pathway (the touch points) rather than the objective pathway, the internal rather than the external environment.

(Bate and Robert 2006: 309)

Of course, the actual medical expertise of the medical specialist in this process is not up for negotiation – although general practitioners will certainly recognise the shift in patient proactivity with the rise of the Internet: doctor–patient consultations and the sense of hierarchy during these meetings are very different these days because the patient now has access to large amounts of medical information and self-diagnostic websites and apps, of varying reliability. Rather, everything about the process around the medical specialist’s use of her expertise and skills can be part of this co-creation effort, and the idea that Bate and Robert propose amounts to the idea that patients and professionals (doctors, nurses, supporting non-medical staff) invest in the quality of the ‘customer journey’ of the patient. The guiding question then becomes: what do the various stakeholders, and primarily the patients, experience while they go through the treatment and healing process, and how can they increase the quality of those experiences in such a way that they contribute to the healing process? So, it is important to understand that this experience-based process is not intended to replace the medical treatment but to complement it, expressing the conviction that ‘classical’ rational and hierarchical argumentation is essential, but that people bond and work together based on experiences, on emotion-based interaction, on discovering shared values and so on, and not (just) based on argumentation about what might be scientifically (or in this case medically) correct or provable.

Interesting, in light of our previous discussion of narrativity, is that Bate and Robert make it a point to say that ‘sickness unfolds in stories’ (2006: 309). They are quite correct: as we saw in the earlier example of the family that needs to adjust to the new situation of the mother ending up in a wheelchair, injury and sickness can be decisive moments in the life history of an individual and/or her social network. They are meaningful, often transformative (e.g. because they are traumatic, or because they require a practical adjustment, as in the family example), and as such are placed in narrative structures involving past and future, memories and expectations, and many emotional elements (fear, hope, gratitude, happiness, depression, and everything else that can emerge in treatment and healing processes). Improving the quality of that storyline right at the ‘plot element’ that could cause the greatest amount of stress – the medical treatment – should help increase positive affect, one of the determinants of well-being (see the previous chapter).

The narrative character of these health-related processes makes the problems very complex, but it also holds the seed for a solution strategy in it. That is, in Bate and Robert’s health-focused idea, we see the relevance of several helpful leisure-centric concepts: the optimalisation of the quality of experiences by transforming (part of) a person’s narrative as embedded in a particular system. After all, improving the quality of experiences is what, for instance, event organisers and other leisure managers are particularly focused on and skilled at.

Warner et al. (2012) make an explicit connection to leisure in another well-being/health-related context, i.e. as part of an analysis of what kinds of strategies help with successful aging for older people who are returning home after hospitalisation (i.e. a disturbance of normal life of the kind we have seen before). In their plans for an optimistic construal of their future, respondents of their study specifically mentioned that they were looking for something meaningful to do, and wished to connect with other people. The kinds of activities that they could see themselves engaging in to realise these goals were usually leisure activities. So if we ask how we can design interventions intended to increase health and well-being, a powerful context to help increase the quality of the experience turns out to be the leisure context, which facilitates social interaction and the co-creation of meaning.

Part of the reason why leisure is such a powerful force in co-creating meaning is provided by Fitzgerald and Kirk (2009). They investigated how personal identity, shared values and social interaction habits are negotiated by young disabled people growing up in a non-disabled family. The disruptive narrative in such families was, in some cases, one of missed opportunities and unfulfilled dreams (of the child and the parents) due to the child’s disability. Their key finding was that shared leisure activities, specifically sports, played an important role in (re-)establishing healthy family relationships at several levels. Specifically, Fitzgerald and Kirk say that they found:

evidence of a range of uses of sport and other activities in the construction and constitution of legitimate and valued techniques of the body. In some cases, specific sports were a shared interest among some or all family members, and for the young people concerned provided resources to construct deeply felt embodied values. Here we found diversity of sporting capabilities and knowledge enjoying parity of esteem with non-disabled body norms, and evidence of the reverse socialisation of parents into their child’s disability sport.

(2009: 483, emphasis ours)

This finding aligns rather neatly with our analysis of the effectivity of murderball in the previous chapter, including its embodied, life-affirming aspect, in the self-emancipation of disabled people.

Chalip (2006) found an important factor that can help explain how leisure activities can support these personal and collective realignment processes when he investigated the social leverage of leisure, specifically sports events. His main finding was that the festive aspects of leisure (in his study’s case: sports events) create liminality. Liminality is a concept from anthropology, and it refers to an ambiguous state that can be part of a ritual, in which participants occupy a kind of ‘in between’ in the transformation process that this ritual is intended to facilitate. In the vernacular that we have been using in this book, perhaps we could say that a liminal state is a state of disruption, for instance due to having experienced or being in the process of experiencing a surprising, inspiring or otherwise anomalous but generative event. This liminal state usually occurs in the context of a sacred ritual (in a secular context, it is called ‘liminoid’) – what we could call a transcendental experience, or, following our exploration in Chapter 7, a spiritual experience. In the conceptual frame we have been using in this chapter, we could say that a disruption is customarily followed by the system (the individual, the social group that she is a part of, or the entire audience at the event) reorganising itself, looking for a new interpretation of this disruptive event that makes sense, that appears coherent in the broader context of the life narrative, and hence aligns with the system’s identity.

As Chalip (2006) says, an important outcome of the reorganisation process after a liminal state can be a sense of community, which anthropologists call communitas. This communitas emerges because the event’s liminal properties (e.g. celebration, fun) provide a context in which people can experiment with their identity and habitual actions and reactions. This is what we defined earlier as playfulness: leisure opens up social space for alternative, more liquid forms of social interaction by providing new narratives and festive, creative and inspiring experiences. In other words: leisure is fun, and when people have fun, they are more open to new ideas, e.g. social experimentation.

This openness facilitated by leisure is key. Regarding that point, Coalter (2010) highlights the network backbone of leisure events, where leisure is used almost as an ‘excuse’ to realise ancillary goals. In his analysis, the sports contest is the focal point of a much broader system of interacting stakeholders of structures, events and meetings, and this is where the real practical work is done. The core leisure activity sets the stage, creates the openness, stimulates the optimism for people to come together and look for common ground:

[I]t is not simple sports participation that can hope to achieve most desired outcomes, but sports plus; it is not ‘sport’ that achieves many of these outcomes, but sporting organizations; it is not sport that produces and sustains social capital, enters into partnerships and mobilizes sporting and non-sporting resources, but certain types of social organization.

(Coalter 2010: 1386)

This, in a nutshell, is how he sees sport’s potential contribution to social cohesion and the development of social capital: the leisure activity as such is not necessarily the answer, but it can be the catalyst that inspires the mobilisation of a problem-solving network. Or, to put it differently, leisure provides the (generally – but recall the shock art and black metal examples of the last chapter) benign disruption for the system to find an optimum reorganised state that makes sense to the stakeholders, that fits in with their desired individual and collective narratives.

Now we can see that leisure, metaphorically of course, is a practical metaphor: it disrupts engrained routines and habits and opens up people to new experiences, and points the way towards a new interpretation that participants are invited to explore in a playful, festive context. In an ethical/normative sense, leisure as such is an underdetermined shell, but following our exploration in Chapter 4 (embodied intuitions that lie at the basis of our identities) and Chapter 5 (leisure as art of life, focused on eudaimonia), we can see the idealism of leisure policymakers that we started this chapter with, i.e. that leisure contributes to well-being and a (psychologically and socially) healthy lifestyle, take shape. In leisure, one can become the governor of one’s own well-being.

We close this section with two additional examples, in which leisure elements were used to improve the quality of experiences, thus improving well-being in some non-trivial way. The first example is due to Chalip (2006), who relates a nice story provided by Veno and Veno (1992). They describe how during several successive editions, the yearly Australian Motorcycle Grand Prix faced crowd-control problems, fights and other disturbances. Increasing security details only managed to exacerbate the problems. At some point, an alternative approach was suggested: instead of repressing the negative aspects of the event, the organisers relinquished some of their control and invited attendees to co-organise sub-events, including a parade, demonstrations and exhibits. As such, they found a way to stimulate the positive, celebratory aspects of the event, the communitas, explicitly by mobilising the community to contribute. What this approach did was to reframe this security problem – an apparent lack of top-down control – as something else, namely an opportunity to stimulate co-creation and co-responsibility for the success and safety of the event. The invitation to the bikers to participate in the celebratory context, to reassess their identity as motorcycle-lovers, stimulated the self-organisation of an intrinsic morality structure, enabling some of the attendee groups to ‘police’ themselves, de-escalating potential problems at much earlier stages. This self-generated insight among the bikers then became the source of a solution to the practical problem (i.e. security).

The second example is quite different. Feio (2014) investigated the role of the funeral ritual in people’s acceptance of death, and the dying process. The context of her study was a Portuguese funeral home, which utilised such strict procedures (based on religious and cultural customs) to organise the funeral ritual itself that there was little room for mourners to complete their mourning process in such a way that their subjective cathartic needs were met. By collecting stories of mourners, by sharing examples of different kinds of funeral customs from all over the world, and by designing a co-creation process for people to think about their own death (in line with the co-creative experience design idea of Bate and Robert (2006)), she managed to open up the mourning process and empower people to co-create new ideas about their own mortality that were in line with their (moral) values and subjective cathartic needs. In a cultural and religious context that was not necessarily susceptible to it of its own volition, Feio reframed funerals and the funeral planning process (to be started while the person is still alive) as celebratory events infused with meaningful experiences with a role in emotional processing of personal loss, and in transforming one’s attitude towards death and dying. As such, this was a reinvigoration of the spiritual goal underlying the ritual that, in that context, had become too rigid to still be particularly effective, inspired by the optimistic transformative power of festive leisure events.

The epistemology and metaphysics of leisure-based idealism

Using leisure activities, events and programmes to bring about a different situation, either as a self-directed act, or as a community-directed policy to improve well-being, is an act of creation. Something new is made, something that did not exist before: the idealistic use of leisure involves the (co-) creation of desired outcomes by stimulating a meaningful and/or transformative (leisure) experience. We will now briefly do some philosophical housekeeping, by sketching the epistemological and metaphysical structures underlying these practices.

This is needed because what a policymaker, leisure manager or event organiser does in designing leisure-based interventions to bring about a desired future, is epistemologically complex. Something new is intended to emerge, based on limited knowledge and control of the past and current situation of the attendees, and a mostly ideologically inspired hope for the outcome of the intervention (e.g. the event). Of course, an organiser can have expectations of how the event will play out based on knowledge derived from past experiences, but if the very point of a leisure event is to infuse the system with playfulness and fun instabilities, this also means a certain measure of unpredictability is introduced into the event.

Bevolo (2016) attacks a similar problem when he considers the epistemological character of futures design: designing processes (e.g. stakeholder network cooperation plans), objects/artefacts (e.g. usable objects, like household equipment or cars), but also spaces and places (e.g. shopping districts or neighbourhoods), with the intent of structuring future behaviour of the users. In future studies, the foresight (i.e. knowledge about the future) that is generated is neither deductive nor inductive, but abductive in character.

A valid deduction, the inference from a law or general rule to a proposition about a specific case, is an analytic procedure: no new knowledge is generated, for information delivered in the consequent was already encapsulated within the premise. Induction is the inverse procedure, in which a general statement or law is drawn up on the basis of a limited number of observations. However, Charles Sanders Peirce (see Fischer 2001) came to believe that a valid induction already presupposes the law it is supposed to yield as a hypothesis. The claim is not that induction fails to generate laws, but rather that it adds no new information.

This means that we need an underlying theory of inference that includes the possibility of generating and increasing knowledge on shaky grounds. Abduction, the inferential procedure exhaustively analysed by Peirce, can perform exactly this role. Abduction, it is claimed, is the only inferential structure in which new knowledge is generated, despite the fact it is, strictly speaking, a logically invalid form of reasoning. Abduction, then, is an inference to the best explanation. Starting out with an observation, the procedure consists in formulating a hypothesised rule that, if true, provides the best explanation of the phenomenon observed. In the epistemic practice thus established, abduction yields new knowledge in the form of hypotheses, constrained by properties of the world as it exists in our (embodied) relation to it: the criterion for accepting these hypotheses is pragmatic, namely whether they provide the desired explanation or prediction, i.e. whether they ‘work’.

Abduction is generative inference: the construction of new knowledge. But, it concerns hypothetical, provisional knowledge. This means that on the level of everyday reasoning, and in its most explicit form, this procedure can look like this: starting with limited knowledge of a small number of observed phenomena, via hypotheses that appear coherent but might not be fully corroborated (based as they are on earlier abductive inferences), we arrive at a provisional explanation/prediction, that should always be kept open to revision.

This is exactly the kind of openness demanded by leisure-based planning for desired futures. The co-creative process that forms the core of a leisure experience adds to the shakiness, as it is a constant back-and-forth, a communicative process intended to generate a positive experience. The co-created outcome of the leisure-based process, e.g. an improved atmosphere and better social control in a ‘problematic’ neighbourhood after a festival in which older and newer residents got to meet each other and celebrated their community, is something new that emerged from uncertain beginnings, and this outcome is also constantly open to revision: the ‘storyline’ of this neighbourhood is open-ended. So, the logical form of the forecast and design process of the leisure policymaker or event organiser is abductive.

The resultant epistemological structure is that of social constructivism. In epistemology, social constructivism is a position that takes issue with the focus on objectivity inherent in the received (positivistic) view of science (which is based on an idealised form of natural science). The ideal there is that the scientist operates as a detached observer who registers and analyses objects and processes, and generates statements involving facts about the world. To some extent, this is a defensible position for exact sciences such as physics. However, the social constructivist will argue that dealing with people, including their feelings and choices, is usually a practice charged with subjectivity, and intersubjectivity. In most normal social situations, people co-create ideas and decisions as they interact, discuss and negotiate to find compromises in the face of practical problems. Recall that we encountered a similar criticism of the objectivist scientific endeavour in Intermezzo II, as we discussed the general characteristics of continental philosophy.

Sheila McNamee (2010) suggests that the co-creative capacity of people in a social context also extends to science. She supports a research methodology which involves a co-creative transformation process: researcher and interviewee perform a lived reality together, dependent on their respective sociocultural backgrounds and behavioural contexts. They collectively arrive at an answer to a particular question.

Similarly, we wish to suggest, any new states (e.g. increased well-being), situations (e.g. new friendships and forms of cooperation) or insights (e.g. about one’s own identity, preferences or desires) that can result from a leisure event are socially constructed. Certainly, leisure is often a social, fundamentally co-creative process, as we have argued many times throughout this book. However, that does not mean that everything is subjective, nothing is true or fixed, and everything is up for negotiation (which would be an extreme form of postmodern relativism). An extreme social constructivist claim that no explanation, judgement or theory is fixed and everything is susceptible to anthropic projection, is not true. In fact, important aspects of socially constructed reality might be ontologically subjective, but they are epistemically objective.

John Searle (1995) provides the example money. Money is ontologically subjective (‘we’ create the properties and the associated rules-of-use of these bits of metal and paper), but epistemologically objective (once it is out there and we wish to use it, we, without consciously deciding to do so, enter into a kind of social contract – but drawn up by no one in particular – that we are bound by: we have to follow the rules and do not really have much of a choice in the matter). Many features of society and the rest of the world are like this: of course ‘we’ as a species or cultural/linguistic group have co-created particular categories, concepts and practices, and in that sense these categories, concepts and processes are not the definitive and unavoidable truth. However, these co-creation processes are often not susceptible to renegotiation on an individual level. This means that the wiggle room for the social construction of ‘reality’ is limited. This is helpful for our analysis because this creates the metaphysical room for intersubjective or quasi-objective ethical norms to apply in leisure situations; recall Chapter 5, where we argued for a particular moral character for leisure (namely based on eudaimonia and art of life). We want our suggestion to be somewhat stronger than a purely subjective, merely locally applicable opinion. So, the epistemological character of the forecast and design process of the leisure policymaker or event organiser is that of a moderate social constructivism.

There are a few additional remarks about the social constructivist character of idealistic applications of leisure that we must make before we can move towards a (crude) model of this process. An important aspect is that leisure participation in the sense discussed so far is a process of group dynamics: the social constructivist process of co-creating meanings involves many instances of negotiation and moral value synchronisation. This also implies a certain measure of moral relativism: the abductive procedure of realising the desired outcomes in a co-created value system (co-created in group, given the leisure context) constrains the development of the social system. This creates a deontic dynamic (it has to be this way because this conforms to our deepest values, or because it is the most fun, or provides the most meaningful experience), but this dynamic is contingent on the context, the group composition and the experiential and narrative framing provided by the way the leisure event is organised.

Additionally, using leisure to try and solve practical, societal problems amounts to the introduction of soft determinants into that practical system, such as a focus on playfulness, meaning, pleasant experiences, social interaction, etc. The social, co-creative dimension in particular means that in such uses of leisure, practical problems are reframed partly as moral problems, since co-creation is a value-driven process of negotiation. In this case, as was the case in the co-creative experience design idea for the health contexts of Bate and Robert (2006), rationality is complemented by (embodied) moral intuition. That is, an outcome of the co-creative process, a particular way of engaging with each other in the leisure practice, is chosen because ‘it feels good’, because it results in pleasurable in-group atmosphere or social rewards. For most participants, having these positive feelings and potential for having associated meaningful experiences constitute the main point of engaging in these leisure practices.

The idea is that a practical process, in this case detecting a societal problem and designing a leisure-based intervention (e.g. an event) with the intent of realising some future state in which (part of) this problem is solved, can be analysed on its own merits: in this case, it is a rational, objectively analysable causal chain. However, what involving leisure does is to reframe this practical problem by adding a layer of experiences and narratives that add a social attunement process to the practical problem-solving process, infused with subjective significance and the co-creation of meaning. The leisure event, with the transformative power that celebratory, festive experiences, narratives and other exciting/disruptive events have, causes the personal and/or collective narrative of the attendees to change in such a way that the system’s behaviour is changed, and/or the system’s stakeholders are primed to perform the practical tasks needed to solve the problem.

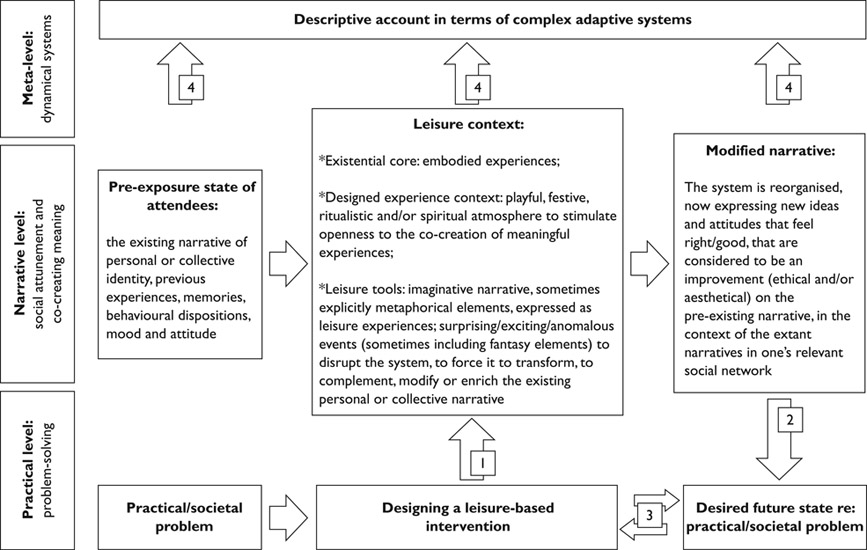

Figure 9.1 shows these leisure intervention analysis levels. Following the arrows through the various boxes takes one through the stages of a particular explanatory account, e.g. one can follow the practical causal chain for a clean, factual account, or the narrative process if one wishes to focus on the experiential dynamics of the attendees, or use all boxes in those two levels to generate an explanation of how the practical and narrative levels interact and complement each other. The explanations could then include all the concepts and ideas that we’ve presented throughout this book.

Some of the arrows are marked with numbers, as they express important additional information. The arrow marked with ‘1’ depicts the transition from the practical to the narrative analysis level, which entails a reframing of hard (practical, rational) determinants to (partly) soft (social, experience-focused) determinants: not (just) ‘what does it cost?’ but (also) ‘how does it affect me if we approach the problem this way?’; not (just) ‘what is most efficient?’ but (also) ‘what is (morally) good/the right thing to do in this situation?’; not (just) ‘what is the schedule of events or the routing on the festival terrain?’ but (also) ‘how do these experiences resonate with my own expectations and desires?’.

The arrow marked with ‘2’ depicts the inverse transition, from the narrative to the practical analysis level. What we see here is that the personal values of attendees and the storylines expressed or experienced during the leisure event constrain the evolution of the practical process to a deontic dynamic. Deontological ethics is about what ought to happen; deontic logic is about the logical structures and rules involved in reasoning about obligations. The deontic dynamic in play here, as we explored earlier, is the metaphorical mapping from ‘is’ to ‘ought’, so given the fact that the attendees’ ideas and attitudes (and the personal and/or collective narrative in which these attitudes are embedded) have shifted due to the leisure event, now something is supposed to happen pertaining to the practical problem that is in play. The process participants have now gotten a personal stake in the process itself, and its outcome, and start getting involved, i.e. start behaving to defend that stake: ‘does this process and/or its outcome align with my personal values?’.

The arrows marked with ‘3’ depict the abductive structure of the leisure organiser’s forecasting strategy – something is supposed to happen, so the design of the leisure intervention should be such that that goal is most likely to be achieved. The forward arrow is causal in character. There is also a feedback loop, and this arrow depicts a constraining influence on the leisure intervention design process: an abductive inference towards the expected and/or intended outcomes of the process reflexively determines what kinds of leisure interventions should be designed.

The arrows marked with ‘4’, finally, depict a possible descriptive level that can be added. Some of the examples throughout this chapter have been about complex adaptive systems; it is possible to provide descriptions of the complex practical-to-narrative-to-practical dynamics by using the concepts of dynamical systems theory. Dynamical systems theory is about the self-organisation of simple structures from complex processes, and originally comes from physics, but is also used more and more in disciplines like psychology (see, e.g. Van Leeuwen 2005), economics, and business innovation (see, e.g. Nijs 2014). This approach would help describe the self-organisation process of the group dynamics of a leisure event audience towards collectively desired outcomes; shared values define attractors in the state space of the dynamical system, and what the leisure organiser does is design interventions (in the form of experiences, narrative elements, surprising twists, etc.) to ‘seed’ attractors, which would facilitate the required value co-creation. This is a very difficult and ambitious endeavour that would take us far beyond the scope of this book, so we will leave it for now. However, it is good to be aware that such options exist, which is why we do mention it here.

We realise that this is quite abstract, even in light of all the examples and concepts that we’ve discussed throughout the book. Here, then, is an example to show how practical and narrative elements interact in a leisure context. The Dutch Headwind Cycling Championship (NK Tegenwindfietsen 2016) is a tongue-in-cheek event that takes place every year in the autumn. It is a cycling contest across the ‘Oosterscheldekering’, part of the Dutch Delta Works, for regular people on regular city bicycles, and it is intentionally planned to take place when the weather conditions are poor: the contestants need to cycle against a strong headwind. It is advertised on Facebook (URL in literature list) and in full-page adverts in national newspapers, with many evocative pictures of cyclists battling against the wind, mini-narratives of contestants, humorous storytelling, experience reports and references to the long fight of the Dutch against the sea (including the massive Delta Works engineering project, which protects the part of the country that lies below sea level from the destructive forces of the water).

If we look to the levels expressed in our model, a few interesting explanations and analyses fall out. At a practical level, this imaginative, strongly narrative and innovative event is a marketing campaign for energy company Eneco, to promote its product wind-generated energy. The intended practical result here is to get more customers. An additional practical aspect is that this is an awareness campaign for sustainable energy and local energy resources (the wind, as opposed to oil imported from far away). The intended practical result in this sense is environmental awareness among the participants, public and Dutch society at large.

The reason that this works, however, should be localised at the narrative level, because the event and its surrounding publicity campaign is steeped in evocative storylines and experiences. It latches on to personal narratives shared by the majority of the Dutch population: it takes the embodied memories and widely shared negative associations of cycling in gray, windy conditions, and reframes them into something with a positive connotation – namely, a fun, tongue-in-cheek competition, where being able to battle and beat the wind becomes a sign of strength, of national pride almost.

At the level of the Dutch national narrative, it taps into the deeply engrained cultural and historical idea of the Netherlands versus the water, and the pride taken in the Delta Works project through professionally shot action scenes and architectural photography of the engineered structure at the event location. Also, the clever metaphorical frame of the ‘Dutch mountain’ is used: the country has an extremely high bicycle density, but it does not have any actual mountains; the reframe is that cycling against the wind is like cycling up a mountain (in terms of the effort that is needed), which makes for a positive comparison to cycling traditions in other, geographically more diverse countries (e.g. France with its Tour de France and Italy with the Giro d’Italia). Another reframe is that it presents the wind not as something inconvenient, but as a renewable national energy source after other possibilities (specifically: the natural gas deposits in the north of the country) are depleted.

These reframing exercises utilise the narrative elements mentioned above, and more: there is also a strong romanticist correlation of man versus nature and man immersed in nature, and it answers a question common in philosophical anthropology, namely ‘what defines a human being?’, with the tongue-in-cheek ‘a Dutch person ≈ human + bike in wind/rain’.