EARLY BLACKFACE ACTS, THE BODY, AND SOCIAL CONTRADICTION

Jim Crow … is made to repeat nightly, almost ad infinitum, his balderdash song …

—PHILIP HONE

In January 1831 William Lloyd Garrison founded the Liberator in Boston, setting in motion one of the great radical movements in American history. A little more than a year later, twenty-four-year-old T. D. Rice toured the northeastern seaboard with his celebrated “Jim Crow” act, landing in New York in November 1832.1 These twin instances of white racial discourse, one middle class and one working class, were dialectical partners not only in their literal coincidence but also in their shared ambivalences. For just as Garrison’s abolitionism was marred by a good deal of paternalist condescension toward the people he wished to liberate, so Rice’s blackface acts mixed equal parts of ridicule and wonder in regard to blacks and black culture. Both ambivalences, moreover, arose from class as much as racial feeling, and it was indeed the way these social categories merged with and repelled each other that defined the political moment in which abolitionism and blackface minstrelsy appeared.

As the blackface acts of Rice, George Washington Dixon, and others hit northeastern cities, they began to register and reaccent the varieties of social unrest that were already the hallmark of industrializing centers. The decade that followed, as historians have constructed it, was one of virtual class war, marked especially by working-class militancy—vehement, collective responsiveness to a class structure that was rigidifying at an alarming rate. In this setting minstrel representations in their inaugural fifteen years after 1830 told a complex tale of gendered class and racial subjectivity. Before the depression at the turn of the 1840s helped mute and redirect class resentment, white male workers targeted both employers and black workers, reformers (often wealthy or evangelical whites) and their “fashionable” black associates—the historical referents of minstrelsy’s oft-remarked capacity to ridicule upward in class as well as downward in racial direction.2 Yet these very spatial metaphors inscribe the interpenetrations of race and class that, as we have seen, constituted the political struggles of this period no less than minstrelsy’s mediations of them; indeed, it was never completely clear just who at any given moment was being combated. Even in the antiabolitionist rioting that gives this decade another claim on our attention, concerns of class and race were jumbled together. In fact, the political confusions of these years seem to me largely ones of representation, and I will argue that the complexities of minstrelsy are to be discovered in its distorted attempts to graph a situation finally quite resistant to such attempts.

By the same token, the distortions and displacements of minstrel representations acknowledged the possibility of a working-class racial radicalism even as they diagnosed the factors making it unlikely. A central figuration of this unlikelihood in public discourse and in minstrelsy, as we shall see, was the urban black “dandy,” an ideological fiction through which certain of this decade’s conflicts were lived. The broadest context for all of this, however, was the simple, undeniable presence of “black” male bodies in the public sphere, and it is with this new presence that I begin.

Until the first blackface band formed in 1843, minstrelsy was an interstitial art: performers appeared between the acts of “respectable” theatrical productions, or as afterpieces to them; they also shared the stage with many comic acts in the pleasure gardens, circuses, museums, and “vaudevilles” newly sprung up to meet the demands of a growing urban working population. Accordingly, the phenomenon consisted largely of solo dancers, banjoists, singers, burlesque playlets, comic impersonations, and various kinds and combinations of duos.

Yet we have seen that for all their scattered presentation, minstrel acts immediately secured “blackness” a public hearing. The urgency that attended its appearance is notable in P. T. Barnum’s tussle with the blackface convention in 1841. Thomas Low Nichols (Walt Whitman’s editor at the New York Aurora in the early 1840s) tells the story of the blackface dancer John Diamond’s quitting Barnum’s organization and leaving the cultural entrepreneur, early in his career, with a problem:

In New York, some years ago, Mr. P. T. Barnum had a clever boy who brought him lots of money as a dancer of negro break-downs; made up, of course, as a negro minstrel, with his face well blackened, and a woolly wig. One day Master Diamond, thinking he might better himself, danced away into the infinite distance.

Barnum, full of expedients, explored the dance-houses of the Five Points and found a boy who could dance a better break-down than Master Diamond. It was easy to hire him; but he was a genuine negro; and there was not an audience in America that would not have resented, in a very energetic fashion, the insult of being asked to look at the dancing of a real negro. To any man but the originator of Joyce Heth, the venerable negro nurse of Washington, and the manufacturer of the Fiji Mermaid, this would have been an insuperable obstacle.

Barnum was equal to the occasion. Son of the State of white oak cheeses and wooden nutmegs, he did not disgrace his lineage. He greased the little “nigger’s” face and rubbed it over with a new blacking of burnt cork, painted his thick lips with vermillion, put on a woolly wig over his tight curled locks, and brought him out as the “champion nigger-dancer of the world.” Had it been suspected that the seeming counterfeit was the genuine article, the New York Vauxhall would have blazed with indignation. (369–70)

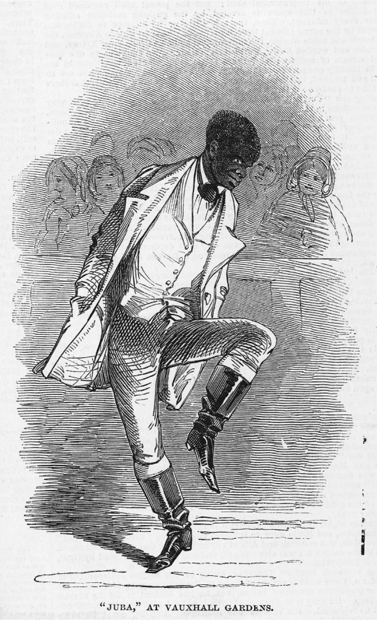

It is easy to remark here that blackface was simply less objectionable than the appearance of black people onstage, particularly given the caricatures that resulted. Yet I would emphasize two things: not only that the idea of black representation had definite limits, was considered offensive or outrageous, worked against the grain; but also that it was possible for a black man in blackface, without a great deal of effort, to offer credible imitations of white men imitating him. That is to say, some blackface impersonations may not have been as far from this period’s black theatrical self-presentation as we tend to believe—and so much the worse, the reader might add: no doubt the standard was set by whites. On this occasion, however, far from easily falling into a prefitted stereotype, the hired black “boy” seems to have been Juba (William Henry Lane), who would a few years later become the most famous—and, significantly, nearly the only—black performer to appear in white theaters in the mid-1840s (see Fig. 4). Dickens celebrated him in chapter 6 of American Notes (1842) as the best popular dancer of the day; even “Master Diamond” (after an 1844 dance competition with Juba that left Diamond the loser) believed him to be the preeminent dancer in antebellum America (Winter 47).

The primary purpose of the mask, then, may have been as much to maintain control over a potentially subversive act as to ridicule, though the double bind was that blackface performers’ attempts at regulation were also capable of producing an aura of “blackness.” The incident suggests the danger of the simple public display of black practices, the offering of them for white enjoyment. The moments at which the intended counterfeit broke down and failed to “seem,” when the fakery evaporated, could (as we have seen) result in acts of unsettling authenticity, even if a white man were inside. From this perspective we might say that the elements of derision involved in blackface performance were not so much its raison d’etre as an attempt to “master” the power and interest of black cultural practices it continually generated. As a figure for early blackface acts, “the seeming counterfeit” is perfectly apt. To the extent that such acts merely seemed, they kept white involvement in black culture under control, indeed facilitated that involvement; but the power disguised by the counterfeit was also often invoked by it, suggesting the occasional ineffectiveness, the mere seeming, of the counterfeit itself.

It is well known that Diamond, Rice, and other early blackface performers laid claim to such power through the predominantly black dances in their acts. Even those most skeptical of the blackface phenomenon commonly accepted the authenticity of the dances (though these, too, as we have seen, were predictably miscegenated). We should notice, however, that whites subtly acknowledged the greater power of the genuine article, a fact that also illuminates the purpose of the diminished copy. Again, the counterfeit was a means of exercising white control over explosive cultural forms as much as it was an avenue of racial derision (though to say the one is perhaps also to say the other). Advertising himself as the “BEST DANCER LIVING,” Diamond boasted in early 1840s playbills of his “skill at Negro Dancing,” which audiences surely enjoyed more than mocked. But in challenge dance contests he would tempt only “any other white person” (perhaps foreseeing his defeat by the expert Juba), a particularly good way of regulating the black threat to his own reputation and to that of his profession while making a living from just that threat. It was paramount that the culture constantly being called up also be kept safely under wraps. This was made plain in a playbill for a New York performance in 1845, by which time Juba’s already legendary stature allowed him to appear regularly on the stage: “The entertainment to conclude with the Imitation Dance, by Mast. Juba, in which he will give correct Imitation Dances of all the principal Ethiopian Dancers in the United States. After which he will give an imitation of himself—and then you will see the vast difference between those that have heretofore attempted dancing and this WONDERFUL YOUNG MAN.”3

This performance seems, and probably was, astonishingly bold: the trusted counterfeiters mocked in return by a representative of those from whom they had stolen; a public display of black irony toward whites, all stammers and jerks and gracelessness, who had tried to become better blacks. Yet it also foregrounds minstrelsy as a safely imitative form: the notion of the black dancer “imitating himself” indicates minstrelsy’s fundamental consequence for black culture, the dispossession and control by whites of black forms that would not for a long time be recovered. Dickens catches this simulacral dilemma almost unawares in his account of Juba when he says, in a final flourish, that the dancer “finishes by leaping gloriously on the bar-counter, and calling for something to drink, with the chuckle of a million of counterfeit Jim Crows, in one inimitable sound!” (139). It was hard to see the real thing without being reminded, even unfavorably, of the copy, the “cover version” that effectively did its work of cultural coverage.4 Nor, just as surely, could the copy be seen without reminding one of the real thing; as Eileen Southern has remarked, “No one forgot that the black man was behind it all” (Music 92). This simultaneous production and subjection of black maleness may have been more than a formal consequence of wearing blackface; it may indeed have been the minstrel show’s main achievement, articulating precisely a certain structure of racial feeling. The very real instability of white men’s investment in black men, however, seems often to have exceeded this happy ambiguity, giving rise to a good deal of trouble. Much of the trouble, as in Dickens’s account, had to do with the black male body.

FIGURE 4 Juba (William Henry Lane)

Courtesy of the Harvard Theatre Collection

Dickens, among many others, marked the male body as the primary site of the power of “blackness” for whites. All that separates his record of Juba from other such commentary (on both white and black performers) is literary skill, by which I mean the ability to disguise his own skittish attraction to the dancer’s body. In New York City, circling toward the center of the wretched Five Points district, Dickens “descends” into Almack’s, “assembly-room of the Five Point fashionables” (138). A lively scene of dancing begins to flag, when Juba makes his appearance:

Suddenly the lively hero dashes in to the rescue. Instantly the fiddler grins, and goes at it tooth and nail; there is new energy in the tambourine; new laughter in the dancers; new smiles in the landlady; new confidence in the landlord; new brightness in the very candles. Single shuffle, double shuffle, cut and cross-cut; snapping his fingers, rolling his eyes, turning in his knees, presenting the backs of his legs in front, spinning about on his toes and heels like nothing but the man’s fingers on the tambourine; dancing with two left legs, two right legs, two wooden legs, two wire legs, two spring legs—all sorts of legs and no legs—what is this to him? (139)

The brilliant dancing calls forth a brilliant mimetic escalation: a sharp focus on simple steps of the feet shifts to jump cuts of fingers, eyes, knees, legs, and bodies that blur into fingers, then to curious industrial metaphors (legs of wood, wire, spring) for the dynamo energy of this “heroic” display. All of it is of course a tribute to such display; the escalation is one of enlarging circles or areas of kinesis. But the energy and artistry are finally distanced; the escalation is away from the dancing; the metaphors dwarf what they are called on to describe. The whole passage reads as though Dickens did not really know what to do with such energy, where to put it. He ends up producing an account that lacks an immanent purpose. All he will venture is that the dance is so dazzling that everything finally seems like something else, not itself—body into fingers, legs into no legs. And once this move is made, the black man’s body has been contained even as it is projected into public, something minstrel performers themselves had somehow to accomplish.

The “black” body’s dangerous power was remarked by nearly all observers of the minstrel phenomenon; it was probably mainly responsible for minstrelsy’s already growing reputation for “vulgarity.” Those conscious of minstrelsy’s counterfeit, for example, resorted to suggestive language to describe its distance from the true coin. The actress Fanny Kemble, in her plantation memoirs of the 1830s, clinched such an observation—that “all the contortions, and springs, and flings, and kicks, and capers you have been beguiled into accepting as indicative of [blacks] are spurious”—by ending the list of adjectives with the inevitable sexual parry “faint, feeble, impotent—in a word, pale Northern reproductions of that ineffable black conception” (96). It required little imagination from the audience to make blackface itself “ineffable,” for dancers made much of the sexual exaggeration that came so easily to such performances, and song sheet illustrations unfailingly registered, in muted form, this recurring preoccupation. Dancers relied on vigorous leg-and footwork, twists, turns, and slaps of toe and heel. The body was always grotesquely contorted, even when sitting; stiffness and extension of arms and legs announced themselves as unsuccessful sublimations of sexual desire (see Fig. 9). (In “Coal Black Rose” [1827], the cuckolded lover sings, “Make haste, Rosa, lubly dear,/I froze tiff as poker waitin here.”)5 Banjos were deployed in ways that anticipated the phallic suggestions of rock ’n’ roll (see Fig. 5). Kemble’s frank fascination with what “these people [slaves] did with their bodies” (96) was carried to the stage, where, for instance, dancers would exploit the accents of sexuality and of sexual ambiguity; the “jaybird wing,” perhaps similar to a frontier dance of the same name, was considered highly indecent for someone in skirts—perhaps even more so if this someone were male (Nathan 91).

We are justified in seeing early blackface performance as one of the very first constitutive discourses of the body in American culture. Certainly minstrelsy’s commercial production of the black male body was a fundamental source of its threat and its fascination for white men, anticipating Harriet Beecher Stowe’s famous “vision” that the whipping of Tom would prove the most potent image of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The problem this cultural form faced was how to ensure that what it invoked was safely rerouted, not through white meanings—for even the anarchic, threatening associations of black male sexuality were created by white cultural meanings—but through a kind of disappearing act in which blackface made “blackness” flicker on and off so as simultaneously to produce and disintegrate the body. Nineteenth-century observers of the minstrel show offer a clue to this dialectic. After a flurry of evidence documenting the authentic nature of early minstrel songs, theater historian T. Allston Brown suggests that most of them (“Long Tail Blue,” “Sich a Getting up Stairs”) “were taken from hearing the darkies of the South singing after the labor of the day was over on the plantation. The verses and airs were altered, written and arranged as I have described” (“Origin” 6). Another commentator believed minstrel songs to be the “veritable tunes and words which have lightened the labor of some weary negro in the cotton fields, amused his moonlight hours as he fished, or waked the spirits of the woods as he followed in the track of the wary racoon” [sic].6 The fact is that minstrel songs and dances conjured up not only the black body but its labor, not only its sexuality but its place and function in a particular economy.

FIGURE 5 Courtesy of the Free Library of Philadelphia

The body, Richard Dyer has argued, becomes a central problem in justifying or legitimating a capitalist (or indeed slave) economy. The rhetoric of these economies must insist either that capital has the magical power of multiplying itself or that slaves are contented, tuneful children in a plantation paradise; in reality, of course, it is human labor that must reproduce itself as well as create surplus value. In these societies the body is a potentially subversive site because to recognize it fully is to recognize the exploitative organization of labor that structures their economies. Cultural strategies must be devised to occlude such a recognition: reducing the body purely to sexuality is one strategy; colonizing it with a medical discourse in which the body is dispersed into discrete parts or organs is another. Shackling the body to a discourse of racial biology is still another, and in western societies the black body in particular has, in Dyer’s words, served as the site of both “remembering and denying the inescapability of the body in the economy,” a figuration of the world’s body and its labor, easily called up and just as easily denied.7 In antebellum America it was minstrelsy that performed this crucial hegemonic function, invoking the black male body as a powerful cultural sign of sexuality as well as a sign of the dangerous, guilt-inducing physical reality of slavery but relying on the derided category of race finally to dismiss both.

The minstrel show as an institution may be profitably understood as a major effort of corporeal containment—which is also to say that it necessarily trained a rather constant regard on the body. Indeed, performers still took care to deflect the wayward valences of the body as they were offered, for there was certainly more at stake than flushes and heavy breathing. Specifically, there were the twin threats of insurrection and intermixture, the consequences, to white men’s minds, of black men’s place in a slave economy. Blackface performers accordingly devised further strategies to counter the various bodily powers they wanted to, and did, evoke.

It will surprise no one familiar with minstrel-show origin tales that insurrection and intermixture effectively mapped minstrelsy’s transgressive range. Early minstrel songs simultaneously produced and muted the physical power of black men coded by such events. Exaggerations or distortions of dialect, for example, or gestures meant to underscore the complete nonsense of some songs might effectively dampen any too boisterous talk, such as that which characterizes one of the earliest versions of “Jim Crow.” And all of the unspoken connotations of this bodily power were clearly wedded to an “inferior” people, played moreover by white men who could easily demarcate the ironic distance between themselves and their personae. Still, the power was made quite available, and could be provocative. “Ching a Ring Chaw,” or “Sambo’s ‘Dress to He’ Bred’rin” (1833), in a caricatured West Indian dialect, marks a white fascination with the insurrectionary imperative:

Broder let us leabe, Bucra Ian for Hettee [Haiti].

Dar you be receibe Gran as La Fayette;

Make a mity show, wen we lan from steamship

I be like Munro, You like Louis Philip.

Oh dat equal sod, hoo no want to go-e

Dare we feel no rod, dar we hab no fo-e

No more carry hod, no more oister ope-e,

No more dig de sod, no more krub de shop-e

No more barrow wheel all about de street-e,

No more blige to teal, den by massa beat-e.8

I am not one of those critics who see in a majority of minstrel songs an unalloyed self-criticism by whites under cover of blackface, the racial parody nearly incidental. Nevertheless, it is hard to resist seeing this invocation of the Haitian republic (whose revolution in the 1790s resonated long after as “a symbol of wild retribution,” as T. W. Higginson termed the Nat Turner insurrection [“Nat” 326]) as anything but a kind of ineffectually controlled historical anxiety; and the song is structured by a burden of “no mores,” not a form designed, it would seem, to control the fantasies of revolt it probably unleashed. A contemporary ominously said of it that it had “the ringing sound of true metal” (“Black” 107): currency again. This is one of the frankest early minstrel tunes about the weight of slavery, more a reminder than a denial of the black male body in the economy.9

More often the reminders came in sexual form. White men were routinely encouraged to indulge in fantasies about black women—which, however, highlighted, and implicitly identified them with, the salacious black male characters who “authored” the fantasies, confusing the real object of sexual interest. Consider the tantalizingly titled “Jumbo Jum” (1840):

There was a nigger wench and I thought I’d die,

For when she looked at me she give such a sigh,

I made an impression on the wenches feeling,

That I set the coloured lady in a big fit a reeling.

She dropt right down on the floor,

In a state of agony you know,

I kissed her gently on the chin,

Says she pray do dat agin.

(Dennison 79)

It might be difficult to add any more insinuations of orgasm than already pack these two stanzas. No doubt performers were adroit at manipulating their bodies in order to bring forth the sexual weight of black men’s “impression” on “colored wenches” (played, again, by men). Song sheet illustrations captured the phallic sources of such lyrics over and over by showing coattails hanging prominently between characters’ legs, and personae were often pictured with sticks or poles strategically placed near the groin or with other appendages occasionally hanging near or between the legs (see Fig. 6; see also Fig. 11).

However strong the attempts at suppression, then, and whatever the ostensible song content, black men were conjured up for the various delectations of white male audiences (even the female characters offered an ambiguous sexuality). Implicit or explicit appreciation of black male sexuality could always slip into homoerotic desire. But the very fact that virulently heterosexual “black” stand-ins were pictured here, and in the theater committed such acts on behalf of the audience, tended further to complicate the whole business. Their potency may have been momentarily attractive (or merely racist typing); but it often shaded inevitably into a suggestion of the “wrong” kind of miscegenation, as in one version of “Zip Coon” (1834): “O my ole mistress is very mad at me,/Because I wouldn’t go wid her and live in Tennessee” (Dennison 61). And in the famous “Long Tail Blue” (1827), a song that refers to the “Uncle Sam” coat of the black dandy, the persona sings:

FIGURE 6 Courtesy of the Free Library of Philadelphia

Some Niggers they have but one coat,

But you see I’ve got two;

I wears a jacket all the week,

And Sunday my long tail blue.

Jim Crow is courting a white gall,

And yaller folks call her Sue;

I guess she back’d a nigger out,

And swung my long tail blue.10

Safe enough pieces of language to us, perhaps; but anyone who has sifted through minstrel song sheets and songbooks knows the seeming scandal, the jealous white male fears, of miscegenation. And since the black male seems the real object of scrutiny here, it is difficult (perhaps even pointless) to distinguish those fears from homosexual fantasies, or at the very least envy, of black men. I have remarked before that white men’s investment in the black penis appears to have defined the minstrel show. As in “Jumbo Jum,” however, that investment took varied and overlapping forms, encompassing homosexual attraction, male identification, and male rivalry, for which the apparent concern with miscegenation is a kind of summa. Ideologies of miscegenation were indeed the primary defense against this psychic tangle, and they surfaced in minstrel songs so often as to suggest repeatedly the unconscious material they strained to master.

Worse yet, stage devices such as malapropism, used to control the black male body’s threat, could themselves become threatening agencies. Given the popularity of women and blacks as sources for public masking, it is interesting that stage malapropism has historically been associated with working-class white women and black men. From Sheridan’s Mrs. Malaprop in The Rivals (1775)—“Sure, if I reprehend any thing in this world, it is the use of my oracular tongue, and a nice derangement of epitaphs!”—to minstrel-show stump speeches, malapropism figures as a kind of witless orality signifying nothing beyond itself. But such self-conscious orality usually has a sexual subtext, as in Mrs. Malaprop’s remark; and the real interest (though perhaps not the literal sense) of this blackface “lecture” on phrenology is fairly transparent: “Colored frens, dar’s one bump dat ought to be on toder side ob de head. (pointing to the nose.) Now, sir, if you keep yourself perfectly docile, I will felt ob your semi-intellectual organs ob your organic, galvanic, elifantic, horse-marine, mud-puddle, flounder-flatten, sculpology.”11 Working-class women (white and black) and black men in bourgeois cultural fantasy are figures for a thrilling and repellent sexual anarchy. If in an age of separate spheres women were responsible for household order and spiritual hygiene, all that was dirty, disruptive, and disorderly was projected onto working-class women. The 1870s cross-class relationship of Arthur J. Munby and a domestic servant, Hannah Cullwick, which fully exploited men’s erotic interest in social domination, female dirtiness, and sexual debasement—not least in Cullwick’s occasional blacking up for Munby, the man she called “Massa”—amply demonstrates the attraction of this kind of Otherness.12 If in an age of industry men were supposed to be frugal and productive, black men quite evidently came to represent laziness and license, the determining factor in white men’s dread of miscegenation; Faulkner’s Quentin Compson in Absalom, Absalom! is probably America’s greatest literary product of this obsession. Onstage these fantasies were partly represented by a vexing and unmeaning linguistic creativity, a proliferation of huge, ungainly, and onomatopoeic words that were meant to ridicule the speaker but which also called attention to the grain of voices, the wagging of tongues, the fatness of painted lips. Through them could be relived the forgotten liberties of infancy—the belly and the sucking of breasts, a wallowing in shit. And while the equation of sexual anarchy with political disorder is an overworked and easy one, it is nevertheless true that minstrelsy’s liberties had varied social and political effects. Which is to say that one of the devices that was supposed to dissolve the more threatening, chaotic, and subversive aspects of the black body could instead provide an avenue through which they returned.

It is equally clear, however, that the cultural form responsible for the insurrection had a built-in structure of disavowal. If the black threat became too grave, audiences merely amplified the insult. A continual acknowledgment of minstrelsy’s counterfeit obviously accompanied the illusion of “blackness” onstage—not only accompanied it but was politically necessitated by it. As Philip Cohen has written in another context, denigrated features (like the reduction of black men to sexuality) could all too easily become secret sources of male identification, cultural myths reversed into male fantasy; the irony of the counterfeit was therefore necessary to construct and preserve the hegemonic “misrecognition” of black people.13 The desperate racial ambivalence that minstrelsy’s audiences shared, in other words, depended on ridicule to counter the sort of attraction or fear we have repeatedly witnessed. To get at the structure of racial feeling exemplified by this dialectic of response, it is first necessary to clarify it, and then to find a social history to account for it.

In the third chapter of Melville’s Confidence-Man, as I have noticed, a splenetic, limping man accuses the beggar Black Guinea of being a counterfeit. Several chapters into the book the confidence man, now disguised as a collector for a “Widow and Orphan Asylum,” engages the accuser in a tête-à-tête, defending what we suspect is one of his earlier disguises:

“Tell me, sir, do you really think that a white could look the negro so? For one, I should call it pretty good acting.”

“Not much better than any other man acts.”

“How? Does all the world act? Am I, for instance, an actor? Is my reverend friend here, too, a performer?”

“Yes, don’t you both perform acts? To do, is to act; so all doers are actors.”

“You trifle.—I ask again, if a white, how could he look the negro so?”

“Never saw the negro-minstrels, I suppose?”

“Yes, but they are apt to overdo the ebony; exemplifying the old saying, not more just than charitable, that ‘the devil is never so black as he is painted.’” (39)

Moments such as this recall Harry Levin’s remark that Melville’s novel is structured like a cross between the minstrel show and Lucian’s Dialogues of the Dead (192). I for one am not sure that the limping man trifles at all. It is indeed this novel’s strategy continually to dissolve the various meanings of “act” into one another, such that all doers become fakes, role players in a competitive marketplace.14 But in an aporia that locates the power of blackface counterfeits, this very logic undercuts the man’s argument: if all doers are mere masqueraders, minstrels are no different from anyone else; their falseness is the only reality there is. The confidence man’s argument likewise self-deconstructs, for he cites the impossibility of a convincing minstrel performance (the ironic “overdo the ebony”) in order precisely to suspend disbelief in his own earlier such performance. The man of spleen who disbelieves the con man’s fakery succeeds in proving the minstrel show’s possibility; the man of irony who argues its impossibility succeeds in proving minstrelsy’s power.

This scene is, one might say, an allegory of audience response: mordant irony and suspension of disbelief were simply inextricable moments of white participation in the minstrel show. The racial predispositions loosely attached to those moments, I would suggest, were disavowal or ridicule of the Other and interracial identification with it, though belief in the authenticity of blackface called forth ridicule easily enough; indeed, the valuations and subject positions tend to multiply when one attempts to sketch them out. I am interested precisely in this “play of pronoun function,” which film theorists insist characterizes our experience of the cinema, as we successively identify, across gender lines, with logical screen representatives of ourselves (heroes, victims), then with seeming adversaries (villains, killers), and so on: a destabilized structure of fascination, a continual confusion of subject and object.15 The blackface phenomenon was virtually constituted by such slippages, positives turning to negatives, selves into others, and back again. There was in minstrelsy an unsteady but structured fluctuation between fascination with (or dread of) “blackness” and fearful ridicule of it, underscored but not necessarily determined by a fluctuation between sympathetic belief in the authenticity of blackface and ironic distance from its counterfeit representations—within a single audience, and even within individual audience members.

An illustration has come down to us that suggests this pattern in more concrete and historically specific fashion. It is an engraving of T. D. Rice “jumping Jim Crow” at the Bowery Theatre in 1833, very early in the minstrel show’s history (see Fig. 7). The illustration is evidence of a most telling kind—audience response about audience response—and indicates the complex, interrelated interests called forth by such performances. Indeed, to call it a drawing of Rice already understates the case. With only a fiddler by his side, Rice performs center stage. He is the only “black” person in the theater. A crowd has thronged to the foot of the stage and overflowed onto the boards. It is a crowd of some variety, except for the almost total absence of women: workers in smocks and straw hats rub elbows with militiamen; clerks ape the betters they hope one day to become; a few respectable men intervene in scuffles that have broken out in two places on the stage. The picture frame is tightly packed with spectators; the frame extends beyond the boxes on the left to include four more tiers of people. The crowd has become both background and foreground—it is not too much to say that it has become the spectacle itself, so much is Rice dwarfed by the crowd’s interest in its own activities. For the singular thing about this audience is that many members of it do not seem to be looking at Rice at all.

FIGURE 7 T. D. Rice as “Jim Crow,” 1833

Courtesy of the New-York Historical Society, New York City

There is a circle of attention directly surrounding Rice, and down in front there are scattered faces turned in his direction. Beyond them, however, all is up for grabs. Much of the crowd is interested in the brawl at stage left, or in conversation among themselves; some of those conversations seem concerned with the brawl, not Rice. The worker behind Rice’s fiddler being held back from the fight suggests either an artistic confusion about the real matter of interest or a trick of the pen meant to unsettle us about it: his legs point directly, foursquare, toward Rice, while his torso is turned full toward the fight. It is an impossible contortion even were verisimilitude a secondary goal here. The fight indeed attracts as much if not more attention than Rice’s act, as does the confusion stage right, a grand collective lunge toward the performer which has itself taken on theatrical interest. In the lunge, a stout gentleman has been put in the dark by the descent of his top hat over his eyes; the lunge’s theatricality has allowed a dandy to appropriate the stage for himself.

One of the earliest pictorial appraisals of this startling new theatrical phenomenon—the caption says this was Rice’s fifty-seventh night in his “original and celebrated extravaganza of JIM CROW”—is thus extremely interested in its audience’s contradictory responses. In this rendition at least, blackface minstrelsy hosts a variety of attentions. While some frankly indulge in Rice’s “blackness,” others involve themselves in the class values articulated through what dime novels sometimes called a “fistic duel.”16 Most striking is the illustration’s assertion, literalized in the contorted worker, that this audience is seeing the performance and performing onstage at the same time, indulging both in “blackness” and in a kind of ironic self-presentation or self-promotion. It is as if the two indulgences were quite compatible—as if the minstrel show encouraged white audiences to find themselves represented in it.17 As I have already hinted, two moments of white participation are apparent here: both have to do with minstrelsy’s status as a predominantly male arena, preoccupied with matters of the body; and both have roots in working-class culture and ideology.

Take the “fistic duel,” for example. What is the significance of working-class brawling onstage at a blackface performance? Why should it be this that sums up Rice’s fifty-seventh night? One might say, with Tocqueville, that “[i]n written productions the literary canons of aristocracy will be gently, gradually, and, so to speak, legally modified; at the theater they will be riotously overthrown” (85). Yet there is more going on here than mere riotousness. Several social historians of the nineteenth century have determined the importance of physical “manliness” and bravery to working-class life, viewing it as an ambiguous force of “lived” class resistance.18 Women no doubt bore the brunt of this kind of physical pride; the construction of masculinity in a capitalist dynamic where power in the body substituted for power in the workplace was obviously only partly transgressive.19 The same can be said for its racial import. Philip Cohen has suggested that working-class men live their class subjection by dissociating themselves from the structural position of their labor and assuming “imaginary positions of mastery linked to masculine ‘prides of place’” (27). This assumption is clearly one moment of the drawing: the fighting workingmen assert their mastery and define their superiority in relation to, and over the body of, a “black” man.

FIGURE 8 Courtesy of the Free Library of Philadelphia

Black men, however, lived their subjection in quite similar ways, which white men recognized and wildly exaggerated in their fantasies of black male aggression. The quarrel between two black men, for instance, was a staple of many early minstrel songs and playlets; often the quarrel was over a woman, as in “Coal Black Rose” (1827) or Rice’s burlesque playlets O Hush! or, The Virginny Cupids (1833) and Bone Squash (1835) (see Fig. 8). Mark Twain’s chief pleasure in minstrel productions as he remembered them was indeed the “happy and accurate imitation of the usual and familiar negro quarrel” (Autobiography 60). The important point is that if white and black men assumed mastery and superiority through similar mechanisms of male rivalry, such similarity, in Cohen’s words, implied “some recognition that black and white [were] peers of the same proletarian public realm” (27). The very activities white male workers used to assert that they were not at the bottom, that they were somebody, could produce instances of solidarity with black men. That is the second moment of the drawing—the fascination with Rice—and it is the second moment of early minstrel productions generally. White workers evinced split perceptions in regard to race, identifying, for example, with individual black men and tolerating various kinds of interracial practice, but disavowing ideally, and ideologically, all modes of intercourse with black people, from “amalgamation” to abolitionism, although this is not the only split one might construct on the basis of the evidence.20 The minstrel show was a form that at some “imaginary” level negotiated and attempted to resolve such contradictions in antebellum American culture, contradictions that stalled organized interracial labor radicalism in the 1830s and early 1840s. Not only were both moments of the contradiction present in minstrelsy, as we have seen in the equivocal character of its representations; but they were also responsible for and infused the ambiguous form of the show itself.21

This view might help reaccent recent debates around white working-class racial tendencies in the years of these first minstrel productions. I have already pointed up a seemingly direct correspondence between public masking rituals, minstrelsy, and the widespread racial hostility among working-class white men. It has been a commonplace of antebellum labor history that such hostility was generated in part out of the extreme competition for work in the earliest stage of “initial proletarianization” in America, though it is now clear that the myth of black competition was a cover story for white workers’ precipitous descent in the class structure.22 Cover story or not, white workers labored to preserve the dignity of work by keeping out the “degrading” presence of blacks. This is one context for the beating of the soon-to-be fugitive slave Frederick Douglass in a Baltimore shipyard by a group of white workers fearful that blacks “would soon take the trade into their own hands” (Narrative 100). It is also one context for antebellum violence such as the 1834 New York antiabolitionist rioting, much of which involved young male workers.23 And it is of course one context for the minstrel show. Several historians, however, have complicated such notions of working-class racism with subtler inquiries into the contradictions of labor’s racial attitudes and ideologies.

A new phrase crept into political discourse in the 1830s to describe the condition of at least the artisan portion of the working class: “wage slavery.” Eric Foner observes that this succinct overlapping of racial and class codes embodied fears about a diminished respect for labor, a loss of economic independence, and the emergence of “European” social conditions, all of which tore at the central ideas and values of artisan radicalism—liberty, democracy, equality. Moreover, Foner says, this term’s metaphorical equation of northern workers with southern slaves carried within it a “critique of the peculiar institution as an extreme form of oppression,” only one indication that the “entire ideology of the labor movement was implicitly hostile to slavery” (“Abolitionism” 61). While such rhetoric was to be put to less emancipatory uses in the hard times of the 1840s, a decade which also witnessed an alliance between Mike Walsh’s “shirtless democracy” and proslavery Democrats, evidence for this earlier period suggests it was a useful strategy.24 The only public New York defense of the Nat Turner insurrection, for example, was published by George Henry Evans’s Daily Sentinel, an organ of the Workingmen’s party: “They were deluded, but their cause was just.” In words that evoke the concept of wage slavery, Evans goes so far as to argue that

we have been negligent in relation to [the slaves’] cause, and our only excuse is, that the class to which we belong, and whose rights we endeavor to advocate, are threatened with evils only inferior to those of slavery…. [W]e are now convinced that our interest demands that we should do more, for EQUAL RIGHTS can never be enjoyed, even by those who are free, in a nation which contains slaveites enough to hold in bondage two millions of human beings.25

Working-class newspapers (and certain minstrel songs) may have been merciless in their ridicule of wealthy evangelical abolitionists such as the Tappan brothers, but, when not distracted by the class makeup of some abolitionist organizations, they were quite ready to hear the merits of antislavery.

Indeed, the largest single group advocating immediate abolition in the 1830s was that of artisans, not professional reformers; artisans were far more widely represented in abolitionist organizations than in antiabolitionist rioting.26 Key figures of “artisan republican” ideology such as Robert Dale Owen and Frances Wright were, after all, well-known antislavery advocates. Jacobin radicalism predisposed labor toward abolitionism, as did evangelical religion, though the latter was a limited source of antislavery support and in some cases worked against it.27 Generally speaking, the hostility to the equation of workers and slaves came as often from the abolitionists, who saw no oppression in northern labor conditions, as from workingmen. The very first issue of the Liberator attacked the New England Association of Farmers, Mechanics, and other Workingmen for unnecessarily exciting the working classes against the “more opulent,” whereas William West, president of the New England Association, wrote in 1831: “I think there is a very intimate connection between the interests of the workingman’s party and [the abolitionists’] own.”28 If minstrelsy had another, more positive moment besides or in addition to racial ridicule, this sympathetic identification between black and white, represented by an inchoate artisan abolitionism, was its political correlative. The minstrel show no doubt supported and was supported by working-class racism; and even an advocacy of abolitionism did not preclude individual racist responses. But opposition to abolitionism did not necessarily mean an acceptance of slavery, either, and minstrelsy also rested on certain kinds of lived interracial identification. These two tendencies within working-class culture were both to be found in blackface, and they shaped the double political valence of the form.29

It is plausible but mistaken to suspect that this duality was a mark of the class unevenness of the minstrel show’s audience, of racial feeling unequally distributed by class fraction, rather than of generalized racial ambivalence. It could also be objected that contradictions in working-class racial feeling owed simply to Alan Dawley and Paul Faler’s cultural and ideological antinomy of “rebels” sympathetic to radical organizing and “traditionalists” indifferent or opposed to it; minstrelsy might then be seen as a form catering not to the restless rebel minority, who rarely went to the theater anyway, but to the traditionalist racist majority—perhaps, in this view, the same men who perpetrated New York’s antiabolitionist riots. Actually, however, there was more contradictory race and class feeling here, which it was minstrelsy’s task to mediate; at least one of those arrested at the scene of the 1834 riots, for example, was a trade union member, and union men were not unfamiliar with the Bowery milieu (Wilentz 264, 270).

The dichotomy of pro-and antiabolitionist workers was itself shot through with ambivalence. The first working-class penny daily newspapers, as I have remarked, voiced highly contradictory attitudes in regard to slavery. Despite their typical advocacy of Democratic party policy, which championed national expansion in alliance with southern slaveholders, papers such as the New York Transcript and the New York Sun, not unlike the Democrats nationally, were split in their views on racial issues—the same kind of split visible in white workers who attended minstrel performances.30 The Transcript, for example, hurled angry denunciations at antislavery agitators while also defending their freedom of speech. The Sun, as abolitionism gathered force, on the one hand printed various kinds of antislavery material and on the other printed anecdotes about racial brawls in which white men were scornfully victorious. What interests me about such ambivalences is that they disallow simplistic ascriptions of racism to the working class and discourage easy dichotomies of working-class culture. They also capture the structure of feeling that made an interracial labor movement falter. Certainly it is this kind of complexity that gives historical concreteness to the equivocations and ambiguities we have seen in the minstrel show.

It bears reiterating that abolitionism’s Whiggish association with wealthy merchants (such as Arthur Tappan), precisely those who were held responsible for the erosion of working conditions, was a major reason for working-class ambivalence toward the movement.31 Also, the association of abolitionism with the evangelical impulse (most frequently in the person of Arthur Tappan’s Sabbatarian brother, Lewis) was read as the “Church and State Party’s” cabal to reform Tom Paine’s republic out of all recognition.32 Neither Tappan hesitated to use his socioeconomic power for purposes of coercion. On one occasion, when a tailor would not sign Lewis Tappan’s petition against Sunday mail delivery, Tappan threatened the artisan that he would get no more business from his brother Arthur’s mercantile firm.33 The Tappans had also founded the New York-based Journal of Commerce, a staunch foe of the trade unions. Artisan ambivalence toward abolitionism was in part a case of class resistance overdetermining and blocking what appears, from the evidence of the minstrel show at least, to have been a real, if tenuous, interest in black people; it was also, of course, merely racist, an expression of white cultural fears. But the sources of identification remained, and were implicit even in minstrelsy’s critiques of antislavery reform. True to the popular anticlericalism of which they formed a part, minstrel songs made frequent reference to the supposed amalgamative tendencies of a “Tappan”—it mattered not which—and rumors flew for a decade that one of the Tappans was about to marry, had married, or was encouraging others to marry, a black.34 Even so, early minstrelsy left occasional interracial recognitions intact by grasping this class resistance to reform even as it took racial parody for granted. This is, as a matter of fact, a succinct way of stating the social complications that wrecked the potential for a labor abolitionism in these years.

Perhaps the severest test of my argument about such contradictions was the seemingly unalloyed racism of the infamous 1834 antiabolitionist riots. If minstrelsy could negotiate the contradictions I have outlined, the riots made for far rougher going; yet the same ideological complexities were at work in both social texts. Indeed, blackface minstrelsy illuminatingly glosses this other bit of riotousness from the Bowery crowd.

Occurring in the midst of a long year of violent public disturbances throughout the Northeast, the New York riots witnessed four nights of extensive violence in a variety of locations.35 More than seven churches—those associated with “amalgamationist,” that is to say abolitionist, ministers—and a dozen houses, many of them belonging to blacks, sustained damage. Skilled “native” workers, rather than the more prominent mercantile and professional men recent historians have fingered as perpetrators of much antebellum rioting, seem to have been largely responsible for the violence.36 On one night of the riots (July 9) there were three separate disturbances that contemporary observers (among them a former mayor, Philip Hone) believed to have been not only linked but attributable to the same mob.37 That perception demands our attention; it amounts to a kind of narrative. Early in the evening a crowd of two to three thousand gathered at the Chatham Street Chapel (an old theater that Arthur Tappan had converted into a church for Charles Grandison Finney) to break up an integrated antislavery meeting; when the meeting did not materialize (the group had been forewarned), certain of the crowd broke into the chapel and passed resolutions in favor of Negro deportation (one young man, wrote The Man, preached “in mock negro style” while his fellows “struck up a Jim Crow chorus”).38 Then a number of them left for the Bowery Theatre, intending to ruin a benefit for its English stage manager, George Farren, whose allegedly anti-American remarks had become associated with Britain’s attacks on American slavery and with British aid to the Tappans’ American Anti-Slavery Society. Meanwhile, a separate mob of about one hundred had converged upon the home of Lewis Tappan himself, smashing windows and doors and burning artwork and fine furniture in the street. One rioter discovered a portrait of Washington, and when a friend insisted, “For God’s sake, don’t burn Washington,” the portrait was gently put aside (Harlow 292). This crowd met the overflow of the Chatham Street crowd at the Bowery. Four thousand people finally stormed the theater, and five hundred to a thousand of them broke in and drove Edwin Forrest and the cast of Metamora from the stage. The rioters were calmed only when the theater manager, Thomas Hamblin, ran in from the wings apologizing for the Farren benefit, waving two American flags, and summoning a performer to sing “Yankee Doodle” and “Zip Coon” (Wilentz 265).

It does not trivialize the violence and destructiveness of the riots to see them as complex events, essentially like all cultural forms: intentional, overlapping weaves of social codes and signifying systems whose larger, “narrative” designs transcended the goals of single individuals. The New York riots were indeed purposive, their targets carefully chosen; they were planned and undertaken with consequence, though abolitionist artisans, together with editors such as George Henry Evans, claimed they merely united the “head” and “tail” of society, revealing the “aristocracy of the North” (merchants and politicians) to be in league with the “penniless profligates.” Some have taken this very perception by “rebel” mechanics to signify their break not only with the elite but also with “traditionalist” workers suddenly using age-old mobbing practices against their own rightful allies.39 Yet there did emerge from the rioters’ actions a complicated tale of republicanism, blending “traditionalist” racism and “rebellious” class resistance in distorted and allegorized ways—a tale related to the ones that occurred in minstrelsy.

The principal part of the night of rioting I have recounted involved three main sites: Lewis Tappan’s house, the Chatham Street Chapel, and the Bowery Theatre. The class logic behind the juxtaposition of these sites ought to be clear from the foregoing pages. And the “recapture” of the Bowery Theatre not only mimics the rowdiness one had come to expect from the shows that played there but also yokes minstrelsy to the ugly purposes of the mob in the form of “Zip Coon.” One should note, too, the variousness of the signs conjoined in the rioters’ expressions of white supremacy, class resistance, and plebeian patriotism: colonizationist speeches (performed in near-blackface in “amalgamationist” churches), Washington’s portrait, “Yankee Doodle,” “Zip Coon.” Washington in this context seems a familiar artisan-republican standard, as does “Yankee Doodle,” talismans meant to keep the British and reformist, that is to say class as well as abolitionist, threats to the republic at bay. Colonizationist speechifying, “in character,” directly controverts abolitionist ideology. But the logic of these anti-amalgamationist rioters’ being calmed by one of the several minstrel songs about the miscegenating proclivities of black “dandies” is somewhat unfathomable. What are we to make of the odd contiguity of celebrated black dandies (“Zip Coon”) and hated “amalgamationist” reformers (the Tappans)? What was the regulative social type of the dandy, who was widely rumored to have been on the loose during the riots advancing racial intermarriage, a figure for—aside, indeed, from amalgamation? What was amalgamation itself a figure for? As with “Jim Crow,” there was certainly racist confirmation here, as if the song sealed the fate of the rioters’ black targets. But we have seen that such racial feeling was part of a more complex dynamic, and I would argue that the early minstrel show provides the best clue to its inner workings. If the riots confirm our suspicion that the amalgamationist prospect of blacks on top, so often played with in minstrelsy, was an intolerable threat in antebellum America, it is also true that minstrel productions such as burlesque playlets clarify the wayward impulses generating the riots.

In these short dramatic interludes, black mechanics combat self-satisfied black dandies who have begun to consider themselves better than the rest. In the most popular playlet, Rice’s O Hush! or, The Virginny Cupids (first presented at the Bowery Theatre in 1833),40 a bootblack named Sambo Johnson who has won the lottery becomes an object of scorn for the “‘spectable,” hardworking bootblacks who rally behind their boss, Cuff (played by Rice). They ridicule Johnson for putting on airs and reading the newspaper (upside down); Johnson’s first riposte to them is to read (that is, pretend to read) an ad for some bootblacks on Canal Street who are underselling them. In what becomes another male-rival plot, it turns out that both Cuff and Johnson are courting Rose (the plot derives directly from the song “Coal Black Rose”). Cuff hides in Rose’s cupboard when Johnson comes to call, and foils the visit by tumbling down from a high shelf—covered with flour—when Johnson tries to kiss Rose. Rose protests to Johnson that Cuff (now unrecognizable) is “noffin’s else but trash … a runaway from de nullifying States,” so Cuff shows his free papers, fights with Johnson, and is hit on the head by Rose with a frying pan. When the men are pulled apart, everything seems settled and all begin to dance. As Rose and Johnson dance, however, Cuff breaks a fiddle over Johnson’s head, Rose faints, and, as the final stage direction has it, “CUFF stands with uplifted hands.”

This is obviously in part a fantasy about social class, in which honest mechanics are vindicated at the expense of those who taunt them with cheap threats and class insults. The dandy who hints that the bootblacks are being undersold is defeated in the end, as is the woman who dismisses Cuff as a slave. It is not too difficult to recognize here the kind of cross-racial identification we have seen before; though the respectable mechanics are black, the plot invokes certain aspects of the “republicanism” so central to white working-class culture—independence, virtue, equality, and so on. There is even an oblique play on “wage slavery,” a charge against which Cuff vigorously defends himself; his “free” papers are more a certification of “manly” integrity than a document of status. The plot in fact underscores the identification of black stage mechanic with white audience mechanic in certain of its devices: Cuff’s momentary whiteness by way of the flour; the pugilistic male rivalry; and the wish fulfillment of sudden riches through the lottery (variants of which, in inheritance plots and millionaires incognito, would become central to the dime novel). Yet this curious figuration of white class conflict through black characters, a formal recognition that white and black cohabited the “same proletarian public realm” (Cohen 27), is even more complex than it may appear, and takes us straight to the riots.

The class object of this narrative of hostility has a racial component that is far from self-evident. The class animus is directed not, as we might expect, at Cuff the boss but at someone outside the master-journeyman nexus, Johnson the black dandy. This racial object certainly illustrates the class limit to interracial identification—and insofar as it echoes the rioters’ call for “Zip Coon” it is an excuse for racist fun. But I believe this character’s condensation of race and class to be a figuration of the antislavery reformer; if the class counterpart of Cuff is the white mechanic, the class counterpart of Johnson is a “Tappan,” the only current social type combining a superior class position with racial overtones. Johnson the dandy indeed occupies the structural position given to the Tappans in many minstrel songs; “amalgamationist” threat, he interposes himself between Rose and the rightful suitor, Cuff. And the association in the rioting of abolitionism with black dandies, not to mention amalgamation, was so strong as to mark a confusion of one hated object with another. For weeks preceding the New York riots there circulated rumors of two basic kinds: one that charged abolitionists with promoting amalgamation, and one that charged black dandies with the wooing of white women.41 Even if the black dandy figure referenced an increasing population of middle-class blacks in the urban Northeast, the animus toward it was not only racial but also class-fueled—a substitute, as one black newspaper put it, for less permissible outlets of class hatred.42 The black dandy literally embodied the amalgamationist threat of abolitionism, and allegorically represented the class threat of those who were advocating it; amalgamation itself, we might even say, was a partial figuration of class aspiration.43 Hence the dandy’s downfall in the playlets and in the rhetoric of the riots, and hence his song at one of the riots’ conclusion. Ironically, the rioters’ targeting of the dandy seems to have achieved one desired outcome: merchants and professionals withdrew from abolitionism in droves, leaving the movement for the most part to artisans and shopkeepers.44

Apparent here, as in the other texts, are the ways in which white men lived an antebellum structure of racial feeling: interracial solidarity was briefly and intermittently achieved through male rituals of rivalry; such solidarity was hampered by the cultural presence of class superiors removed from these rituals, whether in the guise of a wealthy reformer or a black “dandy”; and such solidarity, in any case, was always tenuous and fleeting. We do well to remember, in addition, that even the emancipatory moment of the blackface act was conducted in the realm of male mastery—courtship plots at best, misogynist joking at worst—in other words, over the bodies of women. The plots, types, and disguises to which this structure gave rise might properly be termed minstrelsy’s “dream-work of the social,” in Michael Denning’s phrase, its fantastic figurations of the racial tendencies in antebellum culture (Mechanic 81). In condensed and somewhat displaced form, minstrel productions suggested the class obstacle to a labor abolitionism while they relied, in making that suggestion, on an interracial identification it was the purpose of the riots to negate. Riot and blackface both scapegoated the figure of the black dandy because the latter, I would submit, glossed not only the racism that was one response to the political tensions of antebellum New York, but also the working-class hatred of reformers seen as responsible for the republic’s impending ruin. Here anti-capitalist frustrations stalled potentially positive racial feelings and significations, revealing in the end the viciously racist underside of those frustrations. Yet minstrel productions symbolically and momentarily resolved these contradictions of antebellum white racial feeling.

Readers of Edmund Morgan will have noted a final turn of the screw: the black dandy, in another sense a representative of black maleness as such, was scapegoated to foster the bond between journeyman and master, essentially the argument of Morgan’s American Slavery—American Freedom. This aspect of minstrel productions, of course, was never absent. It returned as if to refute the burgeoning cross-racial interest so manifest in blackface performance in the 1830s. And it leaves us with a question that would be answered in the next decade: to what extent would white workingmen identify with their masters, and to what extent was it possible to do so with their potential black allies?