RACIAL PLEASURE AND CLASS FORMATION IN THE 1840S

The discovery that one has it in one’s power to make someone else comic opens the way to an undreamt-of yield of comic pleasure and is the origin of a highly developed technique.

—SIGMUND FREUD

Sometime in the winter of 1842–43 four irregularly employed circus and minstrel men, in one of the numberless small hotels that lined the Bowery, hit upon the idea of a blackface minstrel band. The band would soon be called the Virginia Minstrels, and it was the first troupe of its kind to form in New York City. Although the story is variously told, all accounts agree that this happy occurrence came about quite by accident. Sitting in the North American Hotel, Dan Emmett, Billy Whitlock, Dick Pelham, and Frank Brower one day decided to descend upon the Bowery Circus with fiddle, banjo, tambourine, and bones and treat one of its proprietors to what Emmett termed a “charivari.” “Without any rehearsal,” according to Emmett, “with hardly the ghost of an idea as to what was to follow,” they crossed the street and “‘browbeat’ Uncle Nate Howes into giving them an engagement, the calculation being that he would succumb in preference to standing the horrible noise” the men made. Intrigued, Howes challenged them to sing a song, whereupon they lit into “Old Dan Tucker,” Emmett singing and the others joining in the chorus. “The four minstrels were as much surprised at the result as was Uncle Nate,” Emmett later told the New York Clipper. “After singing some more songs for him, they returned to the North American, where they resumed their ‘horrible noise’ in the reading-room, which was quickly filled with spectators.”1

Suspect as such accounts typically seem, Emmett’s tale immediately roots us in the culture of early 1840s New York—not least in its crowding of the reading room with the culture of amusements. Above all it situates the activities of the minstrel show in a tradition of “rough music” and charivari that we associate with a moral economy of “natural rights,” the right to bread and work, and a time-honored misogyny dedicated to regulating women’s courtship and sexual practices.2 Regarding the first of these, the minstrel show appears to have taken form most immediately as a response to unemployment, as a means of importuning a prospective employer for a job. Although the response of Emmett and his fellows was undoubtedly influenced by a recent trend toward larger minstrel groups, not to mention “singing families” such as the Hutchinsons, its accidental nature suggests that they simply cast about for the best possible solution to a pressing need. The depression following the 1837 panic had indeed devastated theatrical employments as well as most of the trades. One of the Virginia Minstrels, Billy Whitlock, had once been a printer’s compositor; now the second of his chosen employments was in jeopardy (Rice 12).

It is fitting that the minstrel “show” began in this way, for its institutional popularity may be said to have sprung up as part of the crisis of hegemony brought about by the forward march of capital in the early republic. If early minstrelsy’s contradictory appeal had been subtended by the class warfare that marked most of the 1830s, its plots and types already hinted at the uses of minstrel acts for whites insecure about their whiteness. Working people hit hard by economic disaster in the 1840s were to turn even more urgently to the new minstrel shows. Because the economic slump came amid the enormous shocks that northeastern capitalist consolidation was dealing to the apprentice system of labor, it fostered a profound sense of unease among the popular classes. Their response was a much muted sense of class resistance, an attempt to shore up “white” class identities by targeting new enemies such as immigrants, blacks, and tipplers. This decade’s chiliastic sects, its working-class subcultural styles, its nativist and temperance movements are cited by historians as products of a turn to what David Montgomery calls “cultural politics” in the 1840s. The minstrel show was a key player in the turn, and served a crucial new social purpose.

I focus here on the role of blackface in what one might call, after Gramsci, the production of racist consent. I am after the ways in which a new formal achievement in New York entertainment answered and helped promote an 1840s shift in the structure of racial feeling which had emerged with the onset of metropolitan industrialization. Blackface acts did not merely confirm an already existent racism—an idealist assumption that ignores the ways in which culture is reproduced. Social feelings and relationships are constantly generated and maintained, regulated and fought over, in the sphere of culture and elsewhere, and giving due attention to the minstrel show reveals the straitened contours of racial feeling it helped produce in the hard years of the early 1840s. For even as the new shows continued to sponsor a variety of social contradictions, they began to ease the friction among various segments of the working class, and between workers and class superiors, by seizing on Jim Crow as a common enemy. The alliance at which Rice’s burlesque playlets had hinted in their effigies of the black dandy soon became commonplace in policing the capitalist crisis of the post-panic years.3

Not only had early blackface acts confronted less extreme ideological demands, but they had taken much of their inspiration from class struggle, implicitly coupling the interests of plebeian black and white while mirroring the ways in which class fissures helped destroy interracial coexistence. The minstrel show, as it developed into a night-long entertainment in its own right, met the crisis of the early 1840s with an intensified white egalitarianism that, for all its real instability, buried class tensions and permitted class alliances along rigidifying racial lines, a vital need in this period of seeming disintegration. In what follows I specify the formal and social mechanisms in blackface performance that were congenial to this complex development. If the minstrel show was invented at the very moment when workingmen’s nativist, prosouthern, and temperance groups began to form, we shall see that it fostered this chilly climate with an unusual set of racial and sexual fantasies and representations. To address the other aspect of Emmett’s charivari, we must indeed attend to the intersecting lines of class and race as they were worked out across the body, often in transvestism. And while we shall also see that the new acts, many of them, were not as racially clear-cut as the white egalitarian alliance might have wished, they ultimately turned matters of the body to racist account.

From the start it appeared that a sort of general illicitness was one of the organized minstrel show’s main objectives. So much is suggested, at least, by the lengths to which reviews and playbills typically went to downplay (even as they intimated) its licentious atmosphere:

First Night of the novel, grotesque, original, and surpassingly melodious ethiopian band, entitled the VIRGINIA MINSTRELS. Being an exclusively musical entertainment, combining the banjo, violin, bone castanetts, and tambourine; and entirely exempt from the vulgarities and other objectionable features, which have hitherto characterized negro extravaganzas.4

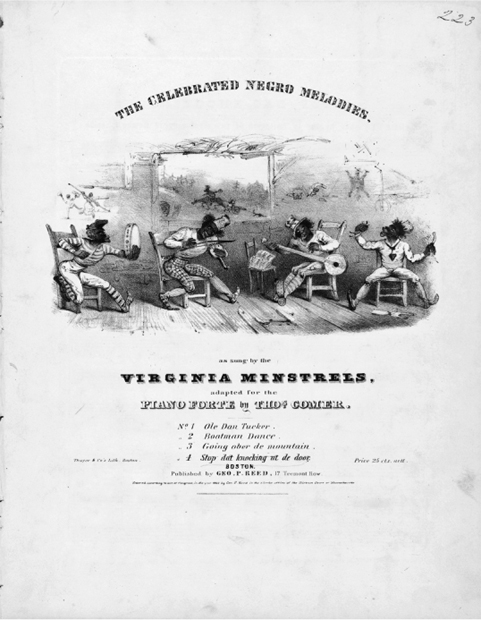

One wants to know more about those other objectionable features. Whatever they were, nobody took very seriously their alleged absence from the minstrel show, as an 1843 song sheet illustration of the Virginia Minstrels only begins to suggest (see Fig. 9). Brower the bone player with legs splayed wide; Pelham on the verge of forced entry of the tambourine; Whitlock in ecstasy behind a phallic banjo: unlike in the engraving of Rice, there is no attempt at realism here. The whole scene has rather the air of a collective masturbation fantasy—accurate enough, one might guess, in capturing the overall spirit of the show. That spirit depended at the very least on the suggestion of black male sexual misdemeanor. And the character of white men’s involvement in this institutional Other of genteel culture bears some scrutiny, for as often as not, audiences were themselves inscribed in advertisements of companies such as the Virginia Minstrels, the “able delineators of the sports and pastimes of the Sable Race of the South … who have won for themselves a popularity unprecedented and the patronage of the elite of Boston” (quoted in Nathan 121). What, in these years, did this spurious “elite” get out of blackface? And what should we make of the obfuscations here, the hints and denials of vulgarity, or the strained attempts to code the popular classes as elite?

FIGURE 9 The Virginia Minstrels, 1843

Courtesy of the Harvard Theatre Collection

The form of the early minstrel show gives us some necessary clues. What the early show was not is as important as what it was. Narrative, for instance, seems to have been only a secondary impulse, even though Rice’s burlesque afterpieces had been tremendous successes in the 1830s. In their first performances the Virginia Minstrels gave what they termed “Negro Concerts,” containing certain burlesque skits, to be sure, but emphasizing wit and melody; the skits themselves, like Emmett’s “Dan Tucker on Horseback,” seemed little more than overgrown circus acts. An 1844 playbill publicizing a “Vocal, Local, Joke-all, and Instrumental Concert” conveys both the tenor and the substance of early minstrel shows (quoted in Odell 5:33). In “sporting saloons” and indeed circuses, among other Bowery leisure sites, the Virginia Minstrels featured burlesque lectures, conundrums, equestrian scenes, and comic songs, finally settling into an early version of the show form that would become standard minstrel procedure. The evening was divided in two; both parts consisted mainly of ensemble songs interspersed with solo banjo songs, and were strung together with witticisms, ripostes, shouts, puns, and other attempts at black impersonation. There was as yet no high-minded interlocutor at whom some of the jokes were later directed. Frequently at least one of the songs was sung by a female impersonator, a figure that would prove enormously popular in the 1840s.5 Very soon the program’s first part came to center on the now institutionalized northern dandy, while its second put the southern slave at center stage. In the late 1840s and early 1850s, as the first part began to be devoted to more sentimental music (sometimes performed without blackface), Emmett’s and other companies added a stirring middle or “olio” section containing a variety of acts (among them a stump speech), the third part then often comprising a skit situated in the South. Seated in a semicircle, the Emmett troupe placed the bones and tambourine players at either end of the band, and though originally all were comic performers, these two endmen began to assume chief importance in most minstrel companies, particularly after the addition of the interlocutor—genteel in comportment and, popular myth notwithstanding, also in blackface.6

The early emphasis, then, was on what film theorists have called spectacle rather than on narrative. The first minstrel shows put narrative to a variety of uses, but relied first and foremost on the objectification of black characters in comic set pieces, repartee, and physical burlesque. If the primary purpose of early blackface performance had been to display the “black” male body as a place where racial boundaries might be both constructed and transgressed, the shows that developed in the mid-1840s were ingenious in coming up with ways to fetishize the body in a spectacle that worked against the forward motion of the show, interrupting the flow of action with uproarious spectacles for erotic consumption, as Laura Mulvey has suggested of women in cinema (19). With all their riot and commotion, contortion and pungency, performers in these first shows exhibited a functional unruliness that, in one commentator’s words, “seemed animated by a savage energy,” nearly wringing minstrel men off their seats—their “white eyes roll[ing] in a curious frenzy” and their “hiccupping chuckles” punctuating the proceedings (Ethiopian 22). Here was an art of performative irruption, of acrobatics and comedy, ostensibly dependable mechanisms of humorous pleasure.7 “Black” figures were there to be looked at, shaped to the demands of desire; they were screens on which audience fantasy could rest, and while this purpose might have had a host of different effects, its fundamental outcome was to secure the position of white spectators as superior, controlling figures. “I am stating a simple fact,” wrote an early admirer of Christy’s Minstrels,

when I say that so droll was the action, so admirable the singing, so clever the instrumentation, and so genuine was the fun of these three nigger minstrels, that I not only laughed till my sides fairly ached, but that I never left an entertainment with a more keen desire to witness it again than I did the first Christy Minstrel concert I had had the pleasure of assisting at…. The staple of E. P. Christy’s entertainment was fun—mind, genuine negro fun … the counterfeit presentment of the southern darkies they personally wished to illustrate, and whose dance and songs, as such darkies, they endeavored to reproduce. (quoted in Nathan 145)

Assertions of the genuine fun these vulgar counterfeits inspired turn up with some frequency in the commentary on blackface, and they offer compelling evidence of the kind of pleasure minstrelsy afforded—so supremely infectious that it begged to be repeated. While we know a fair amount about the overt ideological meanings produced in blackface acts, their more immediate and embodied effects remain poorly understood, as does the relationship of these pleasurable effects to ideology itself. It is not always the case that pleasure, what Roland Barthes once called the “formidable underside” of cultural products (Pleasure 39), entirely coincides with ideological intention: it has an underestimated ability to take its captives in wayward political directions, as we have seen, and this held true throughout the antebellum years of the minstrel show. Behind all the circumlocution going on in descriptions of mid-1840s blackface performance, where the celebrations of “fun” and the aspersions against “vulgarity” intersect, we must begin to glimpse the white male traffic in racial degradation whose cardinal principle was yet a supreme disorderly conduct—a rather equivocal means of racial containment. In this affair “blackness” provided the inspiration as well as the occasion for preposterously sexual, violent, or otherwise prohibited theatrical material—material that could result in a somewhat unsettling spectacle of black power, but which, in this social climate, went a great distance toward the subjection of “blackness.” Indeed, such material and the guilty pleasure it permitted helped clinch popular racist feeling in these years, if unevenly, and in no area was it so bold and unguarded as in minstrelsy’s greatly elaborated staple element, humor.

The function of race in blackface comedy has tended to defeat critics of the minstrel show, particularly when it comes to the subject of racist pleasure. So officially repugnant now are the attitudes responsible for blackface joking that the tendency has been simply to condemn the attitudes themselves—a suspiciously respectable move, and an easy one at that—rather than to investigate the ways in which racist entertainment was once fun, and still is to much of the Caucasian population of the United States. It will hardly do to nod toward ideology as a sufficient explanation for such pleasure, as though it were inherently enjoyable to have one’s prejudices confirmed, or indeed as though cultural products were mere reiterations of ideology. The sources of minstrel acts were more complex than that; and the complexity of racist pleasure was precisely that it was labile enough occasionally to outwit Jacksonian ideological prescription. This observation is, by the way, intended to make it perfectly clear that racial feeling was intrinsic to minstrel joking; more than one misguided critic has seen blackface as an only incidentally racialized example of the burlesque impulse.8 While it is true that audiences in the mid-1840s appear to have been drawn principally to the scabrous fun, it is also true that a special kind of racial pleasure proved so irresistible to minstrel-show audiences. That racist pleasure has proven so resistant to analysis is perhaps only symptomatic of the scandal of pleasure itself, which is notoriously difficult to domesticate and very often goes against the grain of responsible social practice. In pursuing the neglected roots of minstrelsy’s offensive humor, therefore, we should also be prepared to find in and alongside them certain dangerous moments of pleasurable disorder that sometimes offended the racial regime of antebellum America. It might even be said that such titillating ambiguity as to the place and proper function of minstrel comedy was one source of its extreme popularity in the mid-1840s, though this ambiguity was, as I say, increasingly circumscribed. And the promise of racially suspect pleasure for whites in the ostensibly right-minded black comedy of our own time is perhaps blackface humor’s legacy and equally scandalous analogue, an area of complicitous fun whose formation and sedimentation is mightily clarified by investigating the minstrel show.9

Let me emphasize first that the implicitly triangulated, derisive structure of minstrel comedy, in which blackface comic and white spectator shared jokes about an absent third party, usually resolved to a configuration of two people, the joker personifying the person being joked about. The central component of mimicry in minstrel acts was just this aggressive triangulation (the basic situation in Freud’s account of the joking process) masked as an intimate but no less objectifying affair of two. “Entering the theatre,” wrote the Knickerbocker of a T. D. Rice performance, “we found it crammed, from pit to dome, and the best representative of our American negro that we ever saw, was stretching every mouth in the house to its utmost tension. Such a natural gait!—such a laugh!—and such a twitching-up of the arm and shoulder! It was THE negro, par excellence. Long live JAMES CROW, Esquire!”10 Distensions and all, this comic strategy was vital in generating salacious interest in “our” Negroes. Such responses, moreover, begin to point to the affective origins of racist pleasure—the degree to which the scarifying vision of human regression implicit, for whites, in “blackness” was somewhat uneasily converted through laughter and humor into a beloved and reassuring fetish.11

The Knickerbocker is clearly delighted with “blackness” as spectacle, a delight that, in nineteenth-century terms, might border on benignity, but which here seems unpalatable even in those terms. The intermittent illusion of black performers’ presence was especially convenient because in this way white ridicule could be passed off as “naive” black comedy, the sort of comedy, according to Freud, in which spectators indulge in lost moments of childish pleasure evoked by the antics of children, or of “inferior” people who resemble them (Jokes 182–89). The great infectiousness of minstrel performances, I maintain, owed much to these childish sources. For a good deal of the minstrel show’s “vulgarity” approximated life in the nursery, whether it was the nonsense in songs and puns or tirelessly absurd physical antics. Minstrelsy’s stump speeches reached back to long-prohibited pleasure in nonlogical modes of thinking and speaking, or simply to the child’s helplessness before its bodily demands: “Den I ’gin to sweat so … I sweat half de clothes off my back—tumbled ober a sweat-cloth—took a bite ob dar steaks in de bottom ob my pocket—and absquatulated, just for all de world like a California feverite when he’s bound for de gold region!”12 Elsewhere Freud remarks that children tend to expect homonyms to have the same meaning (Jokes 120)—not the worst definition of minstrel puns, which on the page are so weak (Mark Twain professed great exasperation with them) that only the most wizened professional could have brought them to life, let alone to a high pitch of naughtiness:

Why is a fiddle like a handsome young lady? Because it ain’t no use without a bow—(beau.)

Why can a ship’s crew always have fresh eggs when they are out at sea? Because the captain can make the ship lay-to whenever he pleases.13

The oversized clothes performers typically wore, their enormous shooting collars and shoes several sizes too big, had the infantilizing effect of arresting “black” people in the early stages of childhood development.

This is the sense in which “the African,” a “child in intellect” and a “child in faith,” in the words of one Journal of Music minstrel-show fan (“Songs” 51), might become an object of screaming fun and games, as in Emmett’s extraordinarily popular “Old Dan Tucker” (1843):

I come to town de udder night,

I hear de noise den saw de fight,

De watchman was a runnin roun,

Cryin Old Dan Tucker’s come to town,

So get out de way!

Get out de way!

Get out de way! Old Dan Tucker,

Your too late to come to supper.

Tucker is a nice old man,

He use’d to ride our darby ram,

He sent him whizzin down de hill,

If he had’nt got up he’d laid dar still.

Tucker on de wood pile—can’t count ’lebben,

Put in a fedder bed—him gwine to hebben,

His nose so flat, his face so full,

De top ob his head like a bag ob wool14

Those who have heard this plantation trickster’s song know that it conveys the inspired abandon of childhood. What it wished most to provide for its first audiences was the giddiness reliably generated by “Negro” high jinks. Its contribution to racist ideology, like the jokes just cited, is therefore obvious; yet since, as Freud says, naive comedy requires taking the “producing person’s psychical state into consideration, put[ting] ourselves into it and try[ing] to understand it by comparing it with our own” (Jokes 186), one attraction of such joking seems to have been its ability to reduce not only black people but white spectators themselves to children.

This effect perhaps explains the regularity with which observers resorted to the word “fun” to describe their enjoyment of blacks and of blackface acts, a repetition which, congruent with repeated returns to the minstrel show, may suggest (in Freud’s words) “the child’s peculiar pleasure in constant repetition” that is a primary wellspring of jokes (Jokes 226). In fact the disorder conjured out of wayward portrayals of “black” regression also exuded a certain danger; the evidence indicates that spectators duly arrested in infancy experienced something of its terrors as well as its pleasures. This experience comes through, for instance, in Twain’s reminiscences of blackface. The way in which he chooses to celebrate the “genuine nigger show”—he devotes an entire chapter in his autobiography to it—is through a complicated narrative that involves escorting his mother to a Christy’s Minstrels performance in St. Louis. This doubled comic situation, in which Twain pays tribute to the fun of blackface acts with a dose of superadded humor at his mother’s expense, not only places Twain himself in the position of son but also evokes from him a certain amount of oedipal hostility. His mother is an adherent of the church, and while she delights in all sorts of novelties, she must also square these with her religious proclivities. She is, writes Twain, “always ready for Fourth of July processions, Sunday-school processions, lectures, conventions, camp meetings, revivals in the church—in fact, for any and every kind of dissipation that could not be proven to have anything irreligious about it” (Autobiography 62). Twain means to immerse his mother in some real dissipation—a desacralizing impulse on the part of the son inspired by the unease minstrelsy has provoked in the writer.

Twain gets his mother and one Aunt Betsey Smith to go to the minstrel show by telling them it is an exhibition of African music by some lately returned missionaries:

When the grotesque negroes [Twain here gets carried away with his own conceit] came filing out on the stage in their extravagant costumes, the old ladies were almost speechless with astonishment. I explained to them that the missionaries always dressed like that in Africa.

But Aunt Betsey said, reproachfully, “But they’re niggers.” (62)

Of course the novices are soon merrily enjoying themselves, “their consciences … quiet now, quiet enough to be dead,” Twain writes. They gaze on “that long curved line of artistic mountebanks with devouring eyes” (63), finally reinvigorating with their laughter the whole house’s response to a stale joke from the endmen. As is so often the case in accounts of the minstrel show, Twain’s actually reproduces standard elements of blackface joking, here at the expense of blacks and women both. Indeed, the linking of these humorous objects is registered in the syntactical ambiguity as to who possesses the devouring eyes, and this double threat, along with the aggression Twain aims at his mother, points toward the sources of pleasure involved. Twain’s enjoyment of blackface fooling and funning arises from a source of humor Freud calls “degradation to being a child” (Jokes 227). This, of course, was neither the first nor the last time white male affection for blacks, (self-) degradation, and infantile pleasure were conjoined by way of an imaginary racial Other.

This ambivalent atmosphere quite evidently lent itself to a widespread preoccupation in minstrel acts with oral and genital amusement. One might speculate with Melanie Klein, for example, that Twain’s infant sadism owed to blackface’s engendering of a longing for oral bliss whose absence he felt was his mother’s fault and the “devouring” privilege of which was hers alone (267–77, 282–338). Twain stands out neither in his veiled rage nor in his distinct uneasiness. Carl Wittke reports that there was among some blackface performers a superstition regarding the makeup of the mouth, whether painted red or left a sharp, unpainted circle of white around the lips; if this bit was badly managed it was bad luck to take the stage (141). This anxiety not only instances again the mystic or tabooed air that clung to blackface evocations of “blackness” but also attests to the importance the minstrel show accorded certain strategic bodily zones. Fat lips, gaping mouths, sucks on the sugarcane; big heels, huge noses, enormous bustles: here is a child’s-eye view of sexuality, a “pornotopia,” these fetish images recurring so dutifully that minstrelsy comes to seem nothing less than a carnival space devoted precisely to excesses outgrown in the service of workday rationality (see Figs. 5 and 9).15 Twain has Jim sing the protuberant “Lubly Fan Will You Cum Out To Night?” in a book for boys, Tom Sawyer (chap. 2), a scene which again conjoins the naked powers of blackness and femaleness: Jim sings the song as he discovers Tom painting his aunt’s fence in punishment for his truancy. The black and female goads to this childlike ambivalence naturally came together in blackface representations of black women, who generally fared far worse than Twain’s mother. The reader will recognize “Lubly Fan” (1844) as “Buffalo Gals,” though not, perhaps, its original lyrics:

Den lubly Fan will you cum out to night,

will you cum out to night,

will you cum out to night,

Den lubly Fan will you cum out to night,

An dance by de lite ob de moon.

I stopt her an I had some talk,

Had some talk,

Had some talk,

But her foot covered up de whole side-walk

An left no room for me.

Her lips are like de oyster plant,

De oyster plant,

De oyster plant,

I try to kiss dem but I cant,

Dey am so berry large.16

The singer on the Musical Heritage Society’s collection of popular American music gets the ambiguous, almost uncontainable edge of that rising last phrase exactly right.17 Dey am so berry large: allusive promise and exaggerated threat; desire so deep and consequential that it scarcely bears uttering, revulsion so necessary that utterance is ineludible.

What Mikhail Bakhtin called “grotesque realism,” which in Rabelais and His World provides the occasion for so much antibourgeois celebration, here offers up its less than liberatory effects. This song is, to be sure, antibourgeois, but it is again black people, black women, who are the world’s body. While minstrel grotesquerie surely had some hand in constructing a raceless popular community ideal of the “low” and vulgar, it was in this sense more historically useful to some of the people than to all of them. Whether because images of black women abetted the return of rowdy audiences to the pleasures of childhood—to the totalizing, and thus terrorizing, connectedness of pre-oedipal bliss—or because their excess, troubling enough in itself, seemed additionally activated by black male potency, blackface performers tilted their staves at the black female power they simultaneously indulged. To appreciate the force of those charges of “vulgarity,” one must attend to the way certain material—and, we should recall, performers themselves—pressed home a sort of violent corporeal reality:

The other day while riding

With two ladies by my side,

I hardly knew which one to chose

To make my happy bride;

I took them into Taylor’s shop

To get some ginger beer—

They flirted up and down the room—

The white folks they looked queer.

One swallow’d six milk punches,

Half a dozen eggs as well;

But fore de bill was brought to pay

This darkey thought he’d shell.

The other ate six mince pies,

Twelve juleps quickly sped;

And when dey axed me for de tin,

Now what do you think I said?18

The immediacy of the object supervising a loss of the spectatorial subject—the horror of engulfing female bodies, gorging women depleting the bankbook—seems immanent in the most extreme minstrel representations. Here, it seems, the extraordinary energy of antebellum misogyny, perhaps even that contempt for white women intermittently repressed through men’s “protection” of them from savage black manhood, was displaced or surcharged onto the “grotesque” black woman. These images indeed make Klein’s point that the child’s longing for union with the absent mother—a longing both precipitated and symbolized, it seems to me, by certain blackface images—is inextricable from its primitive desire for vengeance against her, in this case the black woman as the world’s mother.19 Yet even within its oppressive outlines, minstrelsy clearly marketed certain “objectionable features” (to recall the first shows of the Virginia Minstrels) which, for all their aggression, were conducive to frightful disorder if not to racial or gender harmony. Why might this experience have been pleasurable at all?

Fredric Jameson has noted that “the aesthetic reception of fear … the enjoyment of the shock and commotion fear brings to the human organism” (“Pleasure” 72), is well-nigh central to the experience of pleasure. From eighteenth-century notions of the sublime to Barthes’s jouissance, Jameson argues, the dissolution of the subject in a paroxysm of threatened menace constitutes one way of transforming “sheer horror” into “libidinal gratification.” How much more must this have been the case when, as in minstrelsy, the horror itself was based on a libidinal economy; when the threat of blackface acts was precisely their hint of pre-oedipal suffocation, or their promised undoing of white male sexual sanctity. If all the hilarity here seems suspicious, it is perhaps because it was both a denial and a pleasurable conversion of a hysterical set of racial fears. Images of the body may be of particular help in this project, offering a symbolic map of psychic, spatial, and social relationships, or a site for the concerns of these realms to be secured or dissolved.20 By way of the “grotesque” (black) body, which, in the words of Peter Stallybrass and Allon White, denied “with a laugh the ludicrous pose of autonomy adopted by the subject” and reopened the normally repressive boundaries of bodily orifices (183–84), the white subject could transform fantasies of racial assault and subversion into riotous pleasure, turn insurrection and intermixture into harmless fun—even though the outlines of the fun disclose its troubled sources. Minstrelsy’s focus on disruptions and infractions of the flesh, its theatrical dream work, condensed and displaced those fears, imaged in the “black” body, that could be neither forgotten nor fully acknowledged.

Yet we ought not overlook an equally present historical referent of the “ecstatic surrender,” in Jameson’s phrase, of blackface minstrelsy’s fearsome pleasure in the early and middle 1840s. The overt rudenesses of minstrel performance seem to me calculated recollections of the pleasures workingmen were at least putatively required to abandon in a society experiencing overwhelming industrial change and an emphasis on workplace discipline and abstemiousness. Whether through coercion or suasion, employers increasingly insisted on the “morality” of their workers.21 The blackface body figured the traditional, “preindustrial” joys that social and economic pressures had begun to marginalize.22 Minstrelsy’s subversively joking focus on bodily degradation, which tainted white spectators themselves, rubbed their noses in foul fluids and anointed them with mud and manure, were splendid transformations of a constricted world into images of imaginary communion and raging excess. The tortured and racist form of this pleasure indicates the ambivalent attitude toward enjoyment itself that industrial morality encouraged.

In rationalized societies such as the one coming into being in the antebellum years, the Other is of prime importance in the organization of desire. Whites’ own “innermost relationship with enjoyment,” writes Slavoj Žižek, is expressed in their fascination with the Other; it is through this very displacement that desire is constituted. Because one is so ambivalent about and represses one’s own pleasure, one imagines the Other to have stolen it or taken it away, and “fantasies about the Other’s special, excessive enjoyment” allow that pleasure to return. Whites get satisfaction in supposing the “racial” Other enjoys in ways unavailable to them—through exotic food, strange and noisy music, outlandish bodily exhibitions, or unremitting sexual appetite. And yet at the same time, because the Other personifies their inner divisions, hatred of their own excess of enjoyment necessitates hatred of the Other.23 Ascribing this excess to the “degraded” blackface Other, and indulging it—by imagining, incorporating, or impersonating the Other—workingmen confronting the demand to be “respectable” might at once take their enjoyment and disavow it. Hence indeed the air of sheepish degradation that hangs over so much of this “fun.” All the standard elements in the repertoire of inversion—filth, scatology, racial marking itself—returned here to assault the white subject whose self-possession had been constituted by their disavowal. The material capacity of burnt cork or greasepaint, mixed with sweat and smearing under the flickering gaslights, to invoke coal, dirt, or their excremental analogues was often acknowledged, as in Tom’s humiliating escape, for instance, in the “Whelp-hunting” chapter of Dickens’s Hard Times (1854), a blacking-up that is a not-quite tarring and feathering. Likewise, it was said of Rice that his reputation depended “upon his blackface; and how he contrives to keep it white, might be matter of grave debate, begrimed as it has been for the last ten years, at least three hours in each of the twenty-four.”24 The pleasurable force of minstrelsy’s suffocating degradation was an ambivalent protest against the new moral order.

Chief among the dissenters were the immigrant Irish, with whom such “black” behavior was already widely associated; removed from the land and from less rigidified rural work rhythms, and cramped in the most crowded sections of northern cities, the Irish clung to old habits and customs by way of entertainments such as brawling, drinking, and minstrelsy. Newly arrived, uncertainly “industrialized” Irish workers appear to have relished and identified with the stage peccadillos they necessarily projected onto blacks.25 Moreover, if, as Paul Gilje suggests, antebellum working-class racism was sometimes only a more focused instance of disgust with unskilled workers and their work habits, then traditionalist practices paraded as “black” in the minstrel show helped displace tensions within the working class even as they made certain objectionable pleasures available to its least reformed members (165–66). In any case, white pleasure in minstrelsy was a kind of social responsiveness; difficult as it may be to acknowledge, this cheap racist libidinal charge was also a willed attempt to rise above the stultifying effects of capitalist boredom and rationalization, especially when the latter meant not increasingly meaningless work but no work at all. It was a rediscovery, against the odds, of repressed pleasure in the body—vulgar enough in taste, and worse in politics, but nonetheless a measure of what Jameson calls the “deeper subject,” the “libidinal body … and its peculiar politics, which may well move in a realm largely beyond the pleasurable in that narrow, culinary, bourgeois sense” (“Pleasure” 69). Codes of industrial morality, or indeed any kind of morality, were utterly negated. I would, however, certainly pause before identifying the pleasure of racist impersonation as some utopian prefiguration; the important point about minstrel-show vulgarity, rather, is that it inevitably connected a local struggle for working-class freedom with the politics of American pleasure. Minstrel comedy forces us to recognize the extent to which comic fun in America is bound up with intimate crises of racial demarcation.

These minstrel types, that is to say, were also black, and much of the disorder was peculiarly orderly after all. If the minstrel show’s “black” body offered a terrible return to the gorging and mucus-mongering of early life (witness, indeed, the lingering resonance of the black mammy figure), it did so in the form of “Othered” images of exhibition. As much as blackface types were sometimes menacing vehicles of fantasy, they were made, even in the terms of menace itself, into levers of mere vulgarity and fun. This may recall the common charge, leveled most compellingly by Nathan Huggins in Harlem Renaissance, that minstrel characters were simply trash-bin projections of white fantasy, vague fleshly signifiers that allowed whites to indulge at a distance all that they found repulsive and fearsome. I would take this line of thinking much further; for, as Stallybrass and White argue, “disgust bears the impress of desire” (77), and, I might add, desire that of disgust. In other words, the repellent elements repressed from white consciousness and projected onto black people were far from securely alienated; they are always already “inside,” part of “us.” Hence the threat of this projected material, and the occasional pleasure of its threat. (I do not assume that black people escape such splits, only that these occur by different means.) It is important to grasp that for white Americans the racial repressed is by definition retained as a (usually eroticized) component of fantasy. Since the racial partitioning so necessary to white self-presence opens up the white Imaginary in the first place, the latter’s store of images and fantasies is virtually constituted by the elements it has attempted to throw off. Which is to say that white subjectivity, founded on this splitting, was and is (in the words of Stallybrass and White) a “mobile, conflictual fusion of power, fear and desire” (5) absolutely dependent on the Otherness it seeks to exclude and constantly open to transgression, although, in wonderfully adaptive fashion, even the transgression may be pleasurable. And if only to guarantee the harmlessness of such transgression, racist “Othering” and similar defenses must be under continual manufacture.26 This is the color line Du Bois was to speak of a half century later, more porous and intimate than his graphic metaphor allowed, and it is the roiling jumble of need, guilt, and disgust that powered blackface acts. It should therefore come as no surprise that minstrel comedy took great strides to tame the “black” threat through laughter or ridicule, or that, on the contrary, the threat itself could sometimes escape complete neutralization. Blackface representations were something like compromise formations of white self-policing, opening the color line to effacement in the very moment of its construction. Three further examples, two based on songbook images and one on the dynamics of theater spectatorship, will make my meaning plain.

The real urgency of white self-policing is evident in the outright aggression of many blackface jokes. Even the ugly vein of hostile wish fulfillment in dime minstrel songbooks reads as a sort of racial panic rather than confident racial power (though, to be sure, the result was hegemonic enough). We are still in the world of the child, the fantasies of omnipotence barely concealing the vulnerability they mask. One notes in particular the relentless transformation of black people into things, as though to clinch the property relations these songs fear are too fluid. The sheer overkill of songs in which black men are roasted, fished for, smoked like tobacco, peeled like potatoes, planted in the soil, or dried and hung up as advertisements is surely suspicious; these murderous fantasies are refined down to perfect examples of protesting far too much. Here is “Gib Us Chaw Tobacco”:

Natur planted a black baby,

To grow dis weed divine,

Dat’s de reason why de niggers

Am made a ’baccy sign.

(Negro 90)

Although this verse comes on in the mimed accents of a cut-rate Aesop, self-buttressing fairy tales such as this one are so baroque that one imagines their concoction requiring a considerable amount of anxious attention. They are not unlike the “atrocious misrepresentations” (as John Quincy Adams called them) in the infamously rigged 1840 U.S. Census, its imagined North populated with frightful hordes of black lunatics and idiots (quoted in Litwack 45). Indeed, in “My Ole Dad,” another oedipal scenario, the ridiculous titular figure mistakenly throws his washing in the river and hangs himself on the line; he goes in after his clothes but drowns. His son subsequently uses fishing line to catch him, a bloated ghost who returns at song’s end, interestingly enough, to haunt his mistress (Negro 30). In the realm of blackface impersonation, one might say, the house was always haunted; the disavowals were never enough to halt the (parental) Other’s encroachment on white self-identity. The continual turn to the mask itself, its obvious usefulness, suggests as much.

Some songs came even closer to the heart of the matter. More successfully prophylactic than “My Ole Dad” is “Ole Tater Peelin”:

Oh, yaller Sam, turn’d a nigger hater,

Ah, oo! ah, oo!

An’ his skin peeled off like boiled potatoe,

Ah, oo! ah, oo!

(Negro 102)

The protagonist of this little rhyme is called “Tater Peelin”; blacks snub him because he becomes colorless, neither “yellow, blue, nor black.” Finally hogs eat him, and plant his bones. (The end result of this particular planting is not specified.) It is difficult to say whether one’s speechlessness before this sort of thing owes more to its merciless brutality or its perverse inventiveness—both significant elements, in my recollection, of schoolyard culture. Again, that is to say, there is the imprint of the panicky child. The concern with fluid, not to say skinless, ego boundaries, together with the imagined introjection of objectified black people, acknowledges precisely the fragility of the racial boundaries the song attempts to police. Obviously the dilemma of “race” is a matter of the marking not of white people themselves but only, in particular, of the liminal “yaller” man produced by intermixture, signifier of the crossed line, of racial trespass. In such songs it is as though whites were at a loss for a language to embody the anxiety that in effect constituted the color line, and indicates how extreme the consequent defensiveness must have been.

Racial defensiveness was imaged in this period in more disguised ways as well. Minstrelsy’s obsession with the penis and with the world’s mother seems to have given rise to an inordinate amount of anxiety and fantasy regarding the threat of castration. Blackface fetish images indeed substituted in complex ways for the threat of the (b)lack.27 Especially instructive examples in this regard are the many songs in which black women get their eyes put out, as in “Old Blind Josey,” whose violent protagonist is already (perhaps revealingly) blind:

But den one night he [Josey] danced so high,

He run his heel in a black gal’s eye—

Oh! Golly me, but didn’t she cry!

Unlucky Old Blind Josey.28

Repeated ad infinitum, such representations signify, if we are to take seriously Freud’s connection of Oedipus’ blinding and castration. It is perfectly clear, moreover, that this fantasy resonated against the erotic white male looking inherent in “black” theatrical display. So variable are the possibilities of spectator identification in the theater, however, that we might inquire as to just whose castration was being constantly bandied about. On the most immediate level, collective white male violence toward black women in minstrelsy not only tamed an evidently too powerful object of interest, but also contributed (in nineteenth-century white men’s terms) to a masculinist enforcement of white male power over the black men to whom the women were supposed to have “belonged.” Indeed, the recurrence of this primal scene, in which beheeled black men blind black women, certainly attests to the power of the black penis in American psychic life, perhaps pointing up the primary reason for the represented violence in the first place. Yet it is still puzzling that black women were so often “castrated,” even if, to follow the metaphor, they were allegorical stand-ins for white men whose erotic looking was undone by the black men they portrayed as objects of their gaze. (No doubt this racial undoing, phallic competition and imagined homosexual threat both, was the fear that underlay the minstrel show tout court.) Or perhaps, if one may extrapolate from Lacan, to castrate the already “castrated” woman was to master the horrifying lack for which she stood.

The elastic nature of spectator identification suggests another possibility, one which does not contradict the general air of male vulnerability being managed or handled here. The blackface image, I have suggested, constituted black people as the focus of the white political Imaginary, placing them in a dialectic of misrecognition and identification. And this dialectic was achieved by a doubled structure of looking; black figures (male and female) became erotic objects both for other characters onstage and for spectators in the theater, with a constant slippage between these two looks. It follows that white men found themselves personified by “black” agents of desire onstage, as in Rice’s O Hush!; and this was of course an equivocal ideological effect because, in allowing white men to assume imaginary positions of black male mastery, it threatened an identification between black men and white men that the blackface act was supposed to have rendered null. “Old Blind Josey,” conversely, uses white men’s imaginary “blackness” to defend them against black male power. The song calls on tricks of (cross-racial) disguise that Michael Denning has shown to be endemic to working-class cultural production in order to make the black male figure of “Old Blind Josey” a representative of white men—already unfortunately castrated, as I have noted—striking out at a black woman who seems not only female but also a cover for black maleness.29 Her typically jutting protuberances and general phallic suggestiveness bear all the marks of the white-fantasized black men who loomed so large in racialized phallic scenarios. It makes perfect sense that castration anxieties in blackface would conjoin the black penis and the woman, as not only in “Old Blind Josey” but “Gal from the South” and other songs. Another referent for whites of Lacan’s threatening (m)Other, Frantz Fanon argued, is precisely the black male—an overlap too pressing to ignore in songs such as these (161).

Thus the “castration” scene played out so often in minstrel songs of the 1840s was an iterative, revealingly compulsive rebuttal of black men by momentarily empowered white men. Such dream-work disguises are telling proof of minstrelsy’s need to figure black sexual power and white male supremacy at one and the same time. In fact, their imaginary resolutions speak perfectly to the structure of feeling behind them: the violence against black women vicariously experienced but also summarily performed; the spectacle of black male power hugely portrayed but also ridiculed and finally appropriated. Just as attacker and victim are expressions of the same psyche in nightmares, so were they expressions of the same spectator in minstrelsy. This dynamic of mastery was both the genesis and the very name of pleasure in the minstrel show.30

One might, after Laura Mulvey, call this dynamic the “pale gaze”—a ferocious investment in demystifying and domesticating black power in white fantasy by projecting vulgar black types as spectacular objects of white men’s looking. This looking always took place in relation to an objectified and sexualized black body, and it was often conjoined to a sense of terror. But the political character of the mid-1840s seems to have held the terror in check. The pale gaze reigned supreme: by 1847 the Spirit of the Times rated the increasingly popular Ethiopian Serenaders, recently returned from serenading English royalty, far below the Christy troupe, who were firmly entrenched down at Mechanics’ Hall:

The performance of the Ethiopians as a delineation of Negro eccentricities is a failure. It is entirely too elegant. The singing is very fine and very agreeable for a time, but its very excellence is an objection to it…. [W]e listen and are pleased, but leave with little desire to return. At the Mechanic’s Hall [sic], we listen and laugh, and have a desire to go again, and again. (October 9, 1847)

The theater historian George Odell expressed legitimate surprise that performers of modest talent, best suited for the circus, could within a few years’ time occupy center stage in blackface minstrel acts (4:478). Odell’s perplexity is a useful reminder that the localizing of “vulgarity” in minstrel shows and other popular forms coincided with their gain in visibility and importance toward the mid-1840s. It should also remind us that nothing intrinsic to minstrelsy accounted for its popularity; it was less the performers than working-class demands and preoccupations that brought blackface into the limelight. The chief reference point for such matters was the depression and its effect on the popular classes.

Historians have long held that the depression, unlike its twentieth-century counterpart, temporarily quieted the claims of class struggle. In contrast to the class vehemence of the 1830s, which resulted, for example, in General Trades’ Union strikes in several cities in 1835–36 and furnished a broad lexicon of class disgust at evangelical reformers and other usurpers of the republic, the post-panic 1840s produced different antagonisms, other investments. David Montgomery has argued that the Philadelphia working class in the mid-1840s divided along ethnic and religious rather than class lines; a “counterpoint of class and ethnic conflict” found disaffected nativist workingmen more often than not siding with their masters against Irish workers, and Irish workers with their masters against nativists rather than “the Catholic weaver, the Methodist shoemaker and the Presbyterian ship carpenter [uniting] as members of a common working class” (“Shuttle” 45, 52, 68). Others have similarly noted the coincidence in this decade of working-class proletarianization—new depredations of “outwork” (piecework done in the home, often for middlemen) and divisions of labor—and the disruption by ethnic segmentation of class militancy.31

Yet, as historians have also acknowledged, class resistance hardly went away. It was injected into popular movements such as land reform, temperance, public education, and “self-improving” mutual aid societies which usually brought together participants from a diversity of class positions. Sean Wilentz has deftly shown how class energies both fueled and bifurcated these movements, a phenomenon that ought to make us attentive to the way racial, ethnic, and other preindustrial conflicts actually masked and provided displaced terrain for the ever-volatile politics of class. To be sure, reform movements such as nativism and temperance did, in Wilentz’s words, define “a new mood in the [New York] trades, an apparent quieting of the class turbulence of the 1830s and a more conservative approach to social and personal problems” arising from workers’ “fears of dependence, from the search for an adjustment to what looked like permanent hard times.” But the decline of mass trade unionism amid reformist impulses indicated only “a change in emphasis and a loss of apparent unity—a return, in most instances, to the broader terms of social conflict, of ‘producer’ versus ‘nonproducer’ rather than of workers versus employers, compounded by a deflection of purpose and new ethnic stratification and tensions” (324, 357). The appearance of lowered class consciousness after the panic was in large part just that, an appearance marred by Mose at the Olympic Theatre, seriously threatened by the b’hoys at Astor Place, and abolished altogether by striking New York tailors in 1850.

In these years of evangelical crusades and ethnic hatred, however, most working-class people were not disposed to look toward an exclusively workers’ millennium, or were but in the name of other enthusiasms. It is thus possible to speculate on the sources and cultural usefulness of the minstrel show’s pleasures. The social contradictions of the 1830s, in which class conflict both permitted and overruled certain radical racial impulses, here became an even more complex bog of social needs, tensions, and feelings. Minstrelsy’s markedly elaborated form in the 1840s amounted to racial rather than more multiply determined aggression; it is interesting, for example, that the interlocutor, that “codfish aristocrat,” was not yet a permanent fixture.32 The minstrel show, as with other kinds of cultural politics in this period, brought various classes and class fractions together, here through a common racial hostility. Minstrelsy was still propelled by, and in many ways hosted, the angry energies of class disaffection; indeed there was always the chance that class disdain might become a liberatory alliance across racial lines against capitalist elites. But there is also a good deal of evidence that in these years, unlike in the 1830s, even the class anger capable of disrupting the white egalitarian alliance was directed at racial targets.33

Certainly the tensions between labor and abolitionism had never been so great; the early and mid-1840s offer a depressing narrative of failed schemes and scuttled allegiances. The entrepreneurial outlook of most antislavery activists made for distinctly uneasy relations between opponents of slavery and opponents of capital.34 The notion of slavery as a metaphor for both black and white oppression, which in the form of “wage slavery” had seemingly harbored much antiracist potential in the 1830s, increasingly led to the ranking of oppressions, distancing rather than relating the conditions of slaves and workers. Wendell Phillips, for instance, would have no part of the idea of wage slavery, perhaps understandably, because for him the condition of slaves was not analogous to that of the masses of workingmen; freedom meant precisely self-ownership. When in 1843–44 the abolitionist John A. Collins, a socialist, began to insist that slavery was only symptomatic of a deeper ill—private property—Garrison and Douglass both heaped scorn on what Douglass later termed his “communistic ideas” (Life 228). Abolitionists were hardly the sole culprits. Working-class politics had so little room to maneuver in hard times that racial sympathy was shoved aside. In a famous 1844 public correspondence with the abolitionist Gerrit Smith, labor reformer George Henry Evans spoke for many labor leaders when he declared himself “formerly” an advocate of abolition: “This was before I saw that there was white slavery.” Figures such as Robert Owen and Horace Greeley were saying much the same thing. Indeed, in the mid-1840s, as David Roediger has shown, “white slavery” came to displace “wage slavery” in labor rhetoric, a figure concerned less with twinning the plight of white worker and slave than with privileging the former over the latter.35 The tenor of the times was evident in one thoroughgoing attempt at a labor abolitionism, Nathaniel P. Rogers’s proposed alliance of northern and southern workers against all the exploiters of labor, which unfortunately gave more attention to the northern capitalist than to the slave owner, perhaps confirming the suspicions of the abolitionists. Workers were rarely proslavery, but, for a variety of reasons, abolitionism was less and less their chosen reform.36

These incidents highlight the familiar ways in which class oppression hampered working-class abolitionism. Yet in these years such class-resistant impulses were very often expressed or lived as racial distaste and white self-validation, a convenient displacement of class anger not at all unlike the nativist or temperance versions of class collaboration. In contrast to the previous decade, there was now little worker abolitionism to offset such a result, and it had to compete in any case with alliances such as that between the working-class rebels behind Mike Walsh and proslavery Calhoun Democrats (no matter that low-tariffism and anti–Van Burenism helped this alliance along [Wilentz 333]). What class rhetoric remained, moreover, was vented as much at abolitionists as at other class enemies. The general result was to substitute racial hostility for class struggle, which at least temporarily, and in at least this sense, settled accounts between artisans and laborers, ethnics and natives, workingmen as a class and their employers: a crucial development amid the disarticulation of capital in antebellum America.37

In the racial chill, then, two main working-class impulses were nourished. On the one hand there was an assumption of broad cross-class agreement on racial tenets, on the other a sense of class disaffection that in the present climate had lost its capacity to extend across racial lines. These impulses marked the relations not only between workers and those above them but also between various fractions of the working class. The minstrel show appealed to workingmen because it relied on a shared (though largely empty) “whiteness” even as its rowdiness differentiated worker from bourgeois. Workers on the very bottom may have negotiated the cementing of their class position beneath the artisan class by denying that position through celebrations of their free-white status as well as embracing it through unseemly—and unrepublican—activities such as racist mobbing and other forms of public racial antagonism.38 Thus did popular racism aid the formation of the white working class: “whiteness” was capacious enough to allow entry to almost any nonblack worker, and resilient enough to mask the class tensions that were worked out in the modality of race. Racial hostility in itself was no badge of class difference; quite the contrary. But the way in which racism was manifested may have helped mark such differences as were coming to characterize the white-egalitarian world of American workingmen no less than the American republic.

It was just here that the first minstrel shows were situated. Insisting on the whiteness of all upstanding workers, blackface minstrelsy still occupied a very uneasy class space—as we saw in chapter 3, the “dark” side of working-class culture. For while minstrelsy began to issue a sort of racial rallying cry across the classes, it stressed its “vulgarity” in ways that made class difference, and therefore the whole business of class formation, uncomfortably apparent. The grasping after the label “elite” in minstrel playbills and newspaper ads suggests that working-class identities in these years of muted class expression were established not only in the realm of race and other non–class-based associations but by way of variable relations to entertainment forms that bore the marks of class. Minstrel-show partisanship, in other words, had class-related implications, however monochromatic its racial design. One might claim one’s rowdy allegiance, or finesse it through the language of respectability, but one’s ultimate class relationship to such forms could not be ignored. A significant amount of jostling among the classes occurred in the officially homogeneous medium of minstrelsy’s racial representations.

In light of these developments, one begins to remark another sort of spectacle going on in minstrelsy, one that showcased the vulgar themselves. Spec-tatorship, we might even say, was bound up in the early minstrel show with surveillance. Blackface’s sponsoring of what we have seen to be white as well as black infantilization had its analogue in the way it displayed not only “black” figures but white working-class spectators as well. This exhibition, surely, was the point of the whole genre of journalistic theater-crowd observation which proved so valuable in fixing the class allegiances of the minstrel show. Its often ironic discourse was dedicated precisely to locating working-class “pathologies” of theater behavior. Recall the Spirit of the Times’s portrait of the Bowery pit as

a vast sea of upturned faces and red flannel shirts, extending its roaring and turbid waves close up to the foot-lights on either side, clipping in the orchestra and dashing furiously against the boxes—while a row of luckier and stronger-shouldered amateurs have pushed, pulled and trampled their way far in advance of the rest, and actually stand with their chins resting on the lamp board, chanking peanuts and squirting tobacco juice upon the stage. (February 6, 1847)

The body on display here is white; and class is on display in the form of bodies and bodily behaviors. Such writing serves not only to localize class values in theatrical spectacles of the body such as the minstrel show, but to scrutinize the way working-classness itself was lived in the body—scandalous enough in an age bent on devising bourgeois codes of self-abnegation.39 The minstrel show’s display of spectators’ bodily activity had the effect of securing rowdy class meanings and significations in a context which pressed for their absence, for if the body is notoriously an object of regulation and control, the form and placement of activities such as spitting, eating, or yawning may become areas of refusal to conform to the dictates of propriety. Norbert Elias observes that such “personal” habits and behaviors, while seeming the most natural and automatic things we do, are in fact the most “cultural” (150). Which is to say, of course, that there are class modes of these behaviors, shaped by their relation—their opposition—to other class modes. Given that most minstrel playbills warned audience members against spitting, chewing loudly, or “beat[ing] time with their feet, as it is unpleasant to the audience and interrupts the Performers,” one must guess that the prevalence of these displays attested to the persistence of working-class self-definition by means other than labor activism.40

The reported outrageousness of working-class spectators in accounts such as the one from the Spirit of the Times is attributable to the roving eye of the distanced bystander who speaks either for the shocked bourgeoisie (the high-minded quarterly, the cultural reformer) or the respectable portion of the working class (the penny press). If such accounts involve a good deal of class projection in their details, they also capture a significant and self-conscious set of audience rituals. In fact they describe a certain fraction of theatergoers who know their behavior is under scrutiny, and who agree that the spectacle of minstrel comedy includes their own performance. We must, then, read this critical genre itself as a class break—a break disguised in the context of early 1840s reformist politics. Pierre Bourdieu has drawn our attention to different class-inflected modes of spectatorship; where bourgeois (or bourgeois-aspirant) involvement is often pure disembodied gaze, working-class involvement often takes the form of demonstrative engagement (Distinction 4). One sees precisely this break in journalistic accounts of minstrel-show audiences. It is a break that minstrelsy both encouraged and bridged. For not only did blackface performance give class meanings a local habitation at a time when ideologies of reform denied them a name; but for the length of a night, at least, it resolved the contradiction between the working-class push against the master and the post-panic impulse toward an alliance with him. Purveying racial ideologies over which the classes could bond, the minstrel show offered them in a guise and in a place that all but the most abject of respectable men might find troubling.

As for these men in contradictory class locations—artisans on the rise into the master class, clerks with working-class cultural links—not all of them, of course, were put off by new developments such as blackface minstrelsy. Working-class culture and minstrelsy both were more complex and multilayered than that. The diversity of the minstrel show’s audience depended in part on the fact that upwardly mobile men retained some “low” cultural associations even as they kept a necessary distance from the rites of workingmen. T. J. Clark has detected a kind of knowing connoisseurship in nineteenth-century French petit-bourgeois café-concert spectators, an attitude that helped establish a useful irony toward working-class cultural forms while clearly depending on a oneness with and delight in the forms themselves (Painting 237). Embourgeoisement is in fact undertaken in relation to cultural choices, through, among other things, a “superior” appreciation of popular forms such as blackface—a perspective that in antebellum America was constructed by the “elite” view in the ironic press account. To read the protestations of respectability in minstrel ads is indeed to witness the process of class formation. Having a place in which to be “elite” was a petit-bourgeois necessity; as if in response to this need, popular theatrical forms hosted rituals of class differentiation as well as class solidarity. When the b’hoys screamed that they were “sons of freedom,” the shopkeeper raised a shout he may have retracted with a raised eyebrow. Amusement at the antics of the vulgar distanced them; petit-bourgeois mastery of minstrel-show spectatorship, which included taking in the spectators as part of the show, was precisely the power of one class over another. This dynamic was a theatrical correlative of the contradictory class politics of the 1840s. Indulging the racial vulgarity, small masters and other respectables masked their own social mobility by playacting working-classness among their former associates. Enjoying the show at one remove, they just as surely reveled in the injuries of class.41

We must now turn to blackface transvestism, the supreme form of “vulgarity” in the popular theater and the most difficult to assess. The immense popularity of cross-dressing in the blackface theater suggests that this was one “objectionable feature” no self-respecting troupe of vulgarians could do without. We have already seen many instances of minstrel-show misogyny, and in part the blackface “wench” character was just a more extravagant form in which to achieve the same result. According to one commentator, the female impersonator had “a hair-trigger sort of voice” and an “unholy laugh” capable of hurrying “little innocent children … into premature graves” and convincing wicked unbelievers that “there must, at least, be a hell.” This observer further comments that such performances featured fiendish dances, much show of leg, and silly confidences uttered in parody of womanhood, extending to imitations of popping corks, descriptions of the size of “her” last meal, and tales involving hapless boyfriends who must pawn their clothes. In fine, the female impersonator, this expert notes, “makes you wish the journey of life were ended and you were laid away in a nice, cozy little tomb somewhere under the weeping willows.”42

As this rather extreme account indicates, however, burlesque was wrested from a good deal of anxiety. This is the language of defensiveness, and the first of its referents is the apparently profane and murderous power of women. One outcome of the class formation we have been witnessing was indeed a reorganization of gender roles in and out of the home. “In a period when the productive household economy [men and women working side by side in the patriarchal home] was disappearing and the family wage economy [the pooled earnings of men, women, and children from their separate spheres] had yet fully to take shape,” writes Christine Stansell, many forms of gender strife constituted “a great renegotiation of what, exactly, men and women owed each other” (81). Because the “shocks of the wage system” were so often registered in the form of familial adjustments, she argues, some of the most painful effects of the emerging order were lived as rearrangements in the expectations for men and women (77). Ill-paid, irregular, or nonexistent work made husbands ineffectual breadwinners, weakening cherished patterns of patriarchal control, while wage work offered women some new means of self-support; such developments helped set in motion an epochal battle for rule of the home. Workingmen many times sought to redress the erosion of their authority with abusiveness and violence. Quarrels over household arrangements, domestic service, family loyalty, even female drunkenness pitted self-styled male disciplinarians against “their” women. Tenement women were partially fortified against male hegemony by their extensive involvement in one another’s lives—from neighborly rounds of drinks and shared domestic tasks to emergency eavesdropping on battered wives. As it turned out, says Stansell, certain masculinist traditions were loosening: young women on the Bowery, for example, flaunted a newfound sense of power by way of stylistic excesses that paralleled the cult of the b’hoy. Counterparts of Mose’s Lize, indifferent to bourgeois decorum, they not only dressed in “fancy” clothes—“a light pink contrasting with a deep blue, a bright yellow with a brighter red, and a green with a dashing purple or maroon,” wrote a bemused George Foster—but pursued the city’s parks, promenades, and amusements (including the theater), using commercial leisure to redraw the boundaries of male privilege and ultimately forcing some enlargement of the proletarian public sphere.43

Men threatened by these developments at least had the solace of the minstrel show’s popular misogyny. The “wench” role was made famous in the 1840s by performers such as Barney Williams and George Christy, who vied for the title of originator; many performers (such as a “Master Marks” of Charley White’s Minstrels) probably engaged in similar displays. The most renowned of “wench” performances centered on the song “Miss Lucy Long” (1842), of which there were numerous variations, the most prominent being that of Williams. As best one can tell, the “wench” (despite a “hair-trigger” voice) usually did not sing the songs she starred in; the songbook headnote to Charley White’s version, “The Dancing Lucy Long,” for instance, says that the piece was danced by Master Marks and sung by the band, and Ralph Keeler remembered dancing rather than singing “Lucy Long.”44 The “wench” became the lyric and theatrical object of the song, exhibiting himself in time with the grotesque descriptions. The earliest version of “Lucy Long” includes these verses:

I’ve come again to see you,

I’ll sing another song,

Jist listen to my story,

It isn’t very long.

Oh take your time Miss Lucy,

Take your time Miss Lucy Long.

Oh! Miss Lucy’s teeth is grinning,

Just like an ear ob corn,

And her eyes dey look so winning

Oh! would I’d ne’er been born.

If she makes a scolding wife,

As sure as she was born,

I’ll tote her down to Georgia,

And trade her off for corn.

An 1848 version interpolates this verse:

Miss Lucy, when she trabels,

she always leaves de mark

Ob her footsteps in de gravel,

you can see dem in de dark.45

In such performances coquette was reduced to coon and scolding wife “mastered,” though just what it meant to have footprints that were visible in the dark is anyone’s guess.

It is interesting to note that psychoanalysts consider one form of cross-dressing in men to be a way of warding off castration anxiety, of recovering the phallus for heterosexuality. Having experienced a “feminizing” disturbance in early life, some men allay fears of castration by paradoxically enacting a fantasy in which they become a woman who is genitally male. This identification with the “phallic” woman (the mother) who once threatened them is an attempt at mastery; there is no desire to be a woman, only to “prove” that feminization will not take away their maleness, that there can be such a thing as a woman with a penis. Unlike gay cross-dressers, they wear women’s clothes as a fetish substitute for the (hetero)sexual object, never losing sight of the fact that they are male: on the contrary, they do it to preserve male potency. As Robert Stoller writes, “If females are evidence [to the transvestite] of a state of penislessness, the cause is not hopeless if there are women with penises. What better proof can there be of this than if one is such a creature oneself?”46

Even if it were plausible, as it probably is not, to suggest that blackface “wenches” were so motivated, we must ask whether this logic appealed to their fans. Evidence that it might have is to be found in the kind of pornography that caters to transvestites. It comprises primarily representations of the “phallic” woman—physically large and strong, with gigantic appendages and oversized shoes or boots, the insignia of maleness peeping through the womanly pretense. It is not too far from this preoccupation to spectatorial interest in the theatrical female impersonator, the “funny ole gal” of the minstrel show. “Clad in some tawdry old gown of loud, crude colors,” writes Olive Logan, “whose shortness and scantness display long frilled ‘panties’ and No. 13 valise shoes … the funny old gal is very often a gymnast of no mean amount of muscle, as her saltatory exercises in the break-down prove.”47 This description practically insists on the “phallic” womanhood of the blackface cross-dresser, who, as in the pornographic fantasy and the transvestite’s private behavior, converted men’s gender anxiety into a source of pleasure, in this case comic pleasure. The attraction of all such representations appears to consist in portraying “masculinized,” powerful women, not in order to submit but, through the pleasurable response, to take the power back. The “wench” figure, beyond its rather obvious gender insults, salvaged “potency, power, and masculinity from an originally castrating event” (Stoller 206, 214): offering up a “woman with a penis,” the “wench,” as in other areas of blackface minstrelsy, deflated the threatening, “castrating” power of women.

The theatrical effects the “wench” reached after, however, were sexually variable. The retreat from women into drag tended, of course, to compromise the masculinity that was so hard-won. Indeed, even without female dress the economy of white male looking in blackface spectatorship was apt to convert sexual defensiveness into same-sex desire. This important fact, as I have suggested, asserts itself long before one encounters such desire in cross-dressing. Freud’s suggestive notion that jokes allow access to culturally prohibited sources of pleasure may mean that another of the minstrel show’s purposes was to allow something besides racism onto the American stage (Jokes 101). Antebellum whites scarcely needed a separate institution to indulge their racism; and that racism appears often to have provided the occasion for a wider preoccupation with sexuality, not least homosexuality. Black male genitalia were invoked readily, if coyly:

I don’t like a nigger,

I’ll be dogged if I do,

Kase him feet am so big

Dat he can’t war a shoe.

Oh, I does hate a nigger,

Tho’ its colour ob my skin,

But de blood ob dis nigger

Am all white to de chin.

I war coloured by de smoke,

In de boat war I war borned,

And de gals say my gizzard,

Am as white as de corn.

(Negro 70–71)

These were not the most common lyrics of “Boatmen Dance”—along with “Lubly Fan” and “Old Dan Tucker” one of the most frequently performed songs of the mid-1840s. But in throwing Victorian caution to the wind, they may have gestured toward minstrelsy’s true purposes, in “Boatmen Dance” and elsewhere.

Nowhere was this clearer than when minstrel writers verged on pornographic representations of black men, as in “Astonishing Nose,” which depicts “an ole nig wid a bery long nose”:

Like an elephant’s trunk it reached to his toes,

An wid it he would gib some most astonishing blows

No one dare come near, so great was his might

He used to lie in his bed, wid his nose on de floor,

An when he slept sound his nose it would snore,

Lik a dog in a fight—’twas a wonderful nose,

An it follows him about wherever he goes.

De police arrested him one morning in May,

For obstructing de sidewalk, having his nose in de way.

Dey took him to de court house, dis member to fine;

When dey got dere de nose hung on a tavern sign.

(Fox 74–75)