C H A P T E R F O U R

C H A P T E R F O U R

C H A P T E R F O U R

C H A P T E R F O U RIN CHAPTER 3, WE ILLUSTRATED THE ARCHITECTURE of Balanced Scorecard strategy maps with a company, Store 24, that was following a customer intimacy strategy. In this chapter, we illustrate the strategy maps developed for a product leadership company, National Bank Online Financial Services, and two other companies, Fannie Mae and Nova Scotia Power, Inc., that have followed operational excellence strategies. We also present the strategy maps for an agricultural chemicals company whose strategic themes tracked the evolution of strategy over time. Collectively, these examples reveal how organizations customize their Balanced Scorecards to specific strategies.

National Bank Online Financial Services (OFS), a division of National Bank, was among the first of the major U.S. banks to offer Internet access for online banking services.1 In 1994, when the OFS division was established, only 20,000 customers used the bank’s online service, and these customers used only a limited number of services. By early 1998, OFS had grown to have 350,000 customers. Douglas Newell, the executive vice president of the OFS division, set a goal to have 1 million online customers by the end of the decade. Achieving this growth, however, would require continued investments in technology (both hardware and software). Newell knew such investments could be difficult in the National Bank cost-focused culture, especially for a division that was treated as a cost center.2 Newell felt that he needed a mechanism to communicate his strategy to both the bank’s senior management and his employees. The CFO, Jane Darcy, reflected:

We’re operating in an environment where new projects and opportunities come up continuously and our business environment and competitors are changing all the time. Alliances are constantly being forged and broken. Everyday, a newspaper story reports about a new technology, service offering or way of doing business that affects us. We needed a tool to help us synchronize our strategy with what we were doing on a daily basis and translate that into measurable results. Such a tool would enable us to communicate with senior management, with other departments in the bank and with our OFS employees.

Newell reinforced this need:

While we were very good at articulating the online vision… , we often had difficulty translating that vision into effective execution. We needed a mechanism that would help us ensure that our plans closely supported our vision, and then we needed a set of clearly articulated, objective measures of performance. In the Internet space everything is new. And we needed a better way to identify what was working and what wasn’t working to further our goals.

OFS executives turned to the Balanced Scorecard as the mechanism to address the issues noted by Darcy and Newell. OFS, in its planning process, had already established three strategic themes:

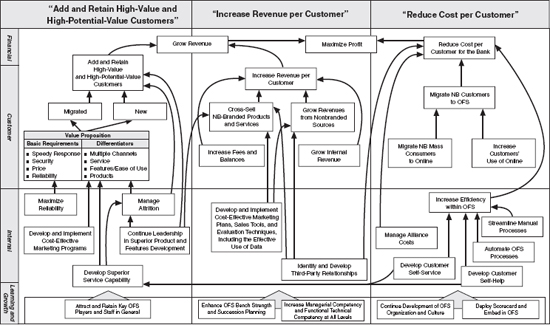

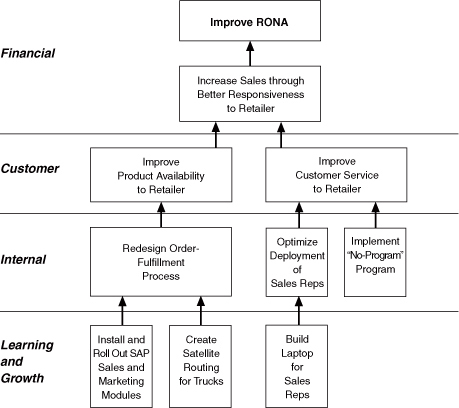

By having these three strategic themes already established, the interdepartmental project team that had been created to build the initial Balanced Scorecard had a great starting point for its task. The team worked hard to define objectives and measures for each of the three strategic themes, eventually producing the strategy map shown in Figure 4-1. The process of drawing the linkage diagrams for the three strategic themes generated extensive debate. But the process of defining and drawing the strategic themes for the scorecard enabled people from across the division to reach a consensus about the strategy and how to implement it effectively. As one participant described it, “We spent weeks getting the linkage map right. We debated where every objective fit on the map. The discussions became heated at times. However, it was good for us to have a cross-functional discussion about each objective, because it helped everyone see how interrelated all objectives are.”

We can analyze the OFS scorecard using the framework established in Chapter 3. Starting with the financial perspective, National Bank OFS identified a gap that existed between its ambitious profit targets and the profits that would be earned with the existing customer base and imbedded costs. The company used its three strategic themes to determine the specific amounts required to close the profit gap:

OFS set stretch targets for each component that, taken together, yielded the desired profit improvement. This set the stage for moving to the customer perspective.

Figure 4-1 National Bank’s Online Financial Service Strategy Map

National Bank OFS was a product leader, the first in its market to leverage emerging Internet-based electronic technology to capture a mass market of banking customers. The strategy required OFS to introduce rapidly a broad portfolio of services that could be delivered through an electronic banking relationship. The OFS value proposition (Figure 4-1) focused on the product profiles that would accelerate the development of their customer base, thus consolidating their early mover advantage. The differentiators included multiple electronic channels to provide services, superior service, ease of use to expand the number of computer-literate customers, and a broad range of financial service products. The basic requirements included speed, response, security, fair price, and reliability.

The Balanced Scorecard project team identified the customer outcomes and drivers in each of the three strategic themes. The customer outcome measures for the first strategic theme—“add and retain high-value and high-potential-value customers”—were the number of incremental and total online customers and the total bank profit per online customer. The retention of customers was measured by customer satisfaction indicators and attrition rates. The measures for the value proposition proved controversial, particularly when the team was setting targets for the internal business process objectives to “maximize reliability” and offer “superior service capability.” Newell wanted to set targets for these objectives that would be comparable to the availability and reliability that consumers experienced with their telephone service. Such targets were of a much greater magnitude than what Internet-based services were currently providing. But Newell eventually helped the entire group to understand that only by offering such dramatic improvements in reliability and access convenience would large numbers of customers shift to the Internet channel. So the process of arguing about the targets for critical Balanced Scorecard measures in the internal perspective eventually created a divisionwide consensus for breakthrough targets on availability and reliability.

The customer objectives for the second strategic theme, “increase revenue per customer,” emphasized the importance of deepening relationships with existing customers. This could come from two sources: cross selling existing National Bank financial services to the OFS customer base, and selling entirely new products and services to customers through this channel. When these customer outcomes were translated to internal processes, the team identified two critical internal processes:

As a specific example of third-party alliances, OFS customers could, with a couple of mouse clicks, send flowers to their moms on Mother’s Day and gifts to dads on Father’s Day. Such new services represented attractive revenue opportunities, as OFS retained the fees earned from these third-party transactions.

The third strategic theme—“reduce cost per customer”—was critical for success of the venture. Prices of financial services were plummeting. For example, competition from specialized discount brokerage firms had reduced online commissions from $90 to $270 per transaction down to around $10 to $25. OFS had to be able to offer this service at competitive prices and still be profitable. Also, the two other strategic themes had emphasized the premium customer, perhaps 20 percent of all banking customers, for whom OFS could become the personal banker for a range of banking, insurance, and investment products. But what about the other 80 percent of banking customers who use only a limited range of products? OFS could generate profits for National Bank if these customers would migrate from branch-based transactions that cost about $1.25 per transaction to online banking services in which transactions, under efficient operations, could be done at $0.01 per transaction. The theme to “reduce cost per customer” reflected the goal of moving customers who were marginally profitable in a bricks-and-mortar environment to profitable customers in a more efficient electronic channel. The key was to continually lower the cost of serving customers, and this included not only handling their transactions but minimizing the need for online personnel to problem-solve and troubleshoot when customers experienced difficulties. The cost reduction theme led to developing several important strategic objectives:

Increase the customer base, as most of the operating costs were “fixed,” independent of the number of customers using the

online service

3

Increase the customer base, as most of the operating costs were “fixed,” independent of the number of customers using the

online service

3

Increase the percentage of customers’ transactions done online

Increase the percentage of customers’ transactions done online

Reduce the cost of handling customer contacts, through streamlined processes

Reduce the cost of handling customer contacts, through streamlined processes

Reduce the need for customer calls, through automated processes and extensive self-help capabilities

Reduce the need for customer calls, through automated processes and extensive self-help capabilities

The last item—self-service capability—enabled customers to manage and monitor their banking transactions in much the same way that shippers can now track the progress of their package deliveries through Federal Express’s online tracking service. Customers make fewer calls for information and help when they can access transactions online. By giving customers the ability to monitor their accounts and transactions online, OFS would lower its costs of service. But online transaction monitoring also contributed to another strategic theme—enhance customer service for high-value customers. With online tracking and self-help, customers felt more in control of their accounts and transactions, so they actually preferred to monitor their transactions online rather than via telephone. Thus the online tracking capability contributed to two strategic themes: cost reduction and enhanced customer service. The team reflected this linkage (see Figure 4-1) by connecting two objectives in the cost reduction strategic theme—“develop customer self-service” and “develop customer self-help”—to the “develop superior service capability” in the add and retain high-value customers strategic theme.

With objectives for the customer perspective completed for the three strategic themes, the OFS project team could now define objectives for its three general internal processes that would deliver on the value proposition and the strategic themes. The innovation process was fundamental to sustaining their product leadership strategy. OFS had to continually lead in the development of superior products and features. Third-party relationships were another source of new products. The customer management processes sought to exploit the benefits from the new products by migrating traditional branch banking customers to the new products now available on the technology-based channel. Within this new body of electronic customers, the team sought to cultivate a set of high-value customers who would use a broader range of services, thus increasing revenue per customer. The operations process, of course, focused on continual improvements in cost and service reliability.

The National Bank OFS strategy for learning and growth (Figure 4-1) was aimed at supporting rapid growth. A relatively small number of people had responsibility for developing the innovative new products required by the strategy. To take advantage of these new products, however, OFS had to expand the size of its workforce while maintaining high levels of quality and alignment to company objectives. The learning and growth objectives were defined as follows:

Attract and retain key OFS players and staff

Attract and retain key OFS players and staff

Enhance OFS bench strength and succession planning

Enhance OFS bench strength and succession planning

Increase managerial competency and functional technical competency at all levels

Increase managerial competency and functional technical competency at all levels

Continue development of the OFS organization and culture

Continue development of the OFS organization and culture

Deploy the scorecard and embed it in OFS

Deploy the scorecard and embed it in OFS

The project team grappled with the issue of how to align these five learning and growth objectives with strategic themes, as these objectives seemed necessary to achieve each of the three strategic themes. The team eventually decided to treat the learning and growth objectives as drivers behind all three themes, instead of aligning a subset of them under any one. They also decided that they would measure the learning and growth objectives annually.

Was the National Bank OFS strategy successful? In 1998, more than 450,000 National Bank customers were paying bills, checking account balances, conducting stock and bond trades, or applying for new accounts. In August 1999, the bank celebrated its millionth customer. National Bank had also received several awards as “Best Online Bank.” On the internal measures, downtime on the OFS banking Web site decreased 71 percent from 1997 to 1998; this increased availability led to a significant decrease in customer calls for service. And the claim ratio on disputed payments also dropped by 50 percent in one year.

OFS soon began to use the scorecard to report to the National Bank chairman’s office on the division’s strategic objectives and measures. Financial measures alone could not summarize whether OFS’s strategy was being implemented successfully either for itself or, more important, for the entire bank. The chief financial officer of OFS emphasized the importance of the scorecard in keeping the organization focused on vital operational issues, even while it exploited technology and managed customer relationships:

It helped us focus on process issues, making sure that we stayed proactive and avoided problems that would create bad customer experiences. Because of our focus on processes, we get really good early warning signs and avoid some of the operational problems that E-Trade, eBay, and other Internet-based services have experienced recently.

In addition to these applications, we discuss in Chapter 11 how OFS used the Balanced Scorecard to set priorities and select initiatives to enhance its strategy.

The Balanced Scorecard has been applied successfully in virtually every industry, from long-cycle companies in pharmaceuticals to short-cycle ones in fashion retailing.4 But technology-based companies like National Bank OFS are often said to be changing at Internet speed, seven to ten times faster than the normal pace of business. Does the Balanced Score-card work in such environments? Some aspects of e-companies appear different. First, by using technology rather than real estate for infrastructure, e-companies can change their product portfolios and distribution channels seemingly overnight. Second, the industry is in a state of rapid flux and instability, so strategies are continually evolving and changing. At present, e-companies are staking out territory by attempting to compete simultaneously on price, service, customer intimacy, and innovation.

Yet e-companies that are continually evolving their strategies need a system for rapid strategy implementation even more than stable companies. These companies’ strategies are still based on differentiated value propositions with underlying strategic hypotheses. The companies must communicate their strategies and value propositions to employees, test and learn about the strategies in real time, and quickly adapt the strategies. Rapid and effective strategy implementation is exactly the task that the Balanced Scorecard management system has been designed to do. Managers can use the scorecard to communicate the stable, long-run success measures as well as the new tactics—in the value proposition and in the internal business processes—that reposition the organization in its competitive environment. If, as we believe, success comes from aligning all employees, decentralized units, and initiatives to the strategy, fast-cycle companies should find the Balanced Scorecard an ideal management tool for quickly realigning the organization to a new strategy.

For example, consider the three strategic themes developed by National Bank OFS for its Balanced Scorecard:

These three themes are applicable to a broad range of rapidly-growing, Internet-based companies. Rather than becoming obsolete in two months, the themes are actually probably relevant and applicable for many years. The tactical details for implementing these objectives may change, but the strategic themes and most of the strategic objectives, particularly in the financial and customer perspectives, would stay the same—not just quarter to quarter but year to year. Thus we believe that the Balanced Scorecard can provide considerable value, not just to slow-cycle organizations such as Mobil and CIGNA, but also for organizations operating in continually evolving competitive marketplaces, such as online products and services.

The scorecard will help e-companies communicate enduring high-level strategic themes to all employees. Senior management can use the strategic themes and objectives to screen new initiatives, as we discuss in Chapter 11. Employees will continually examine their own priorities, opportunities, and day-to-day actions to determine whether they are contributing to the organization’s strategic objectives. As employees learn about new threats, opportunities, capabilities, and technologies, they can assess what behaviors need to be modified and what new initiatives they can propose for the changed environment. At a high level, the senior management team will continually review and assess the value propositions they are offering to accomplish their high-level strategic objectives. Such reviews can lead to changes in the critical internal process objectives and measures, launching new initiatives or canceling existing initiatives. In this way, the scorecard continues to give the company a roadmap to the future, while facilitating the continual adaptation and change that must occur to cope with new opportunities and threats.

The Operations division of Fannie Mae provides an example of an operations excellence strategy. Fannie Mae, formerly a government agency but since 1968 a private shareholder-owned company listed on the New York Stock Exchange, provides financial products and services that increase the availability and affordability of housing for low-, moderate-, and middle-income Americans. Fannie Mae’s stated mission is to tear down barriers, lower costs, and increase the opportunities for home ownership and affordable rental housing for all Americans. Fannie Mae adds liquidity to the home mortgage market through two principal activities. First, it provides insurance by guaranteeing principal and interest payments on qualifying home mortgages. Second, Fannie Mae purchases home mortgages originated by local housing lenders and holds them for investments. At the end of 1999, Fannie Mae guarantees covered 23 percent of outstanding mortgage debt—a book value of $1 trillion. In portfolio, Fannie Mae held 11.7 million loans with a book value of $523 million.

The Fannie Mae Operations and Corporate Services division (OCS) handles what used to be called the “back office” for the insurance, purchase, and investment activities. It is the processing arm of the company, handling the massive quantity of principal and interest payments that flow into it each month. Traditionally, OCS had a simple mandate: soundness and safety. It had to ensure the integrity of processing operations and the security of the enormous quantity of funds that continually flowed through the company. OCS’s secondary objective was cost-efficient operations. Historically, the company had been highly profitable. Unlike the situations at Mobil, CIGNA, or AT&T Canada, described in Chapter 1, no burning platform was raging at Fannie Mae to drive change. It was well run and doing fine. But Fannie Mae recognized that there was competitive advantage to be derived from leveraging operations capability, and the head of Operations wanted to expand by offering even more attractive, efficient, and responsive processing capabilities, including the flexibility to handle new types of financial instruments. The updated strategy for OCS was as follows:

The Balanced Scorecard would play two roles in this strategy. First, it would provide a mechanism to get the executive leadership together in one room to talk about the division’s strategy rather than just how well their individual departments or functions were performing. Second, it would reposition OCS’s role within Fannie Mae beyond being a large support division doing back-office work to becoming a value-adding contributor to the company’s revenue growth strategy.

The financial perspective of OCS’s Balanced Scorecard retained the historic emphasis on low-cost processing. The soundness and safety theme would be reinforced by continued focus on productivity and low-cost processing, enabling operations to “reliably and efficiently manage the current book of business.” In addition, OCS now had a financial growth theme—to become more flexible and more customer-focused—thus enabling revenue growth to occur. This theme was based on leveraging relations with existing customers to identify new services and sources of revenue.

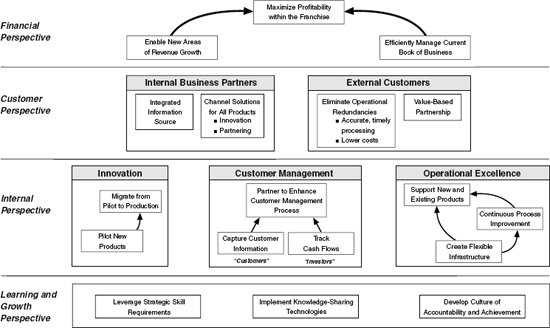

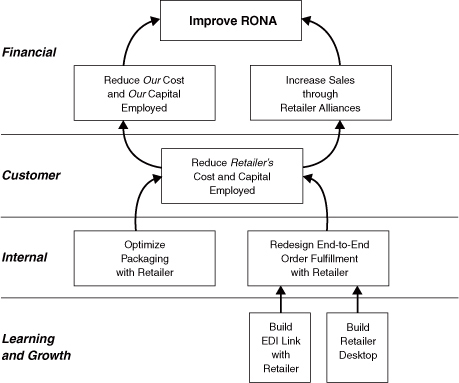

Defining the customer perspective generated extensive and interesting discussions that were primarily focused on identifying who the customer was for the operations division. Early on, it was recognized that the vast majority of external customer contact happens in Operations in the normal course of business, and Fannie Mae Operations wanted to leverage these contacts to add value in the operational channel. OCS historically thought more about functional excellence—low cost, efficient processing of a commodity product—than about customers. As an internal support organization, OCS clearly had internal customers, which it renamed “internal business partners.” For them, OCS was to provide information about external customers, be responsive and collaborate on new opportunities, and partner with marketing and sales groups to provide value to end-use customers. In addition, OCS decided to recognize explicitly how it provided value to external customers. Operations wanted to work with lenders to develop a more integrated process from the point of underwriting and loan origination through ongoing loan servicing. Initially, the management team felt that as long as it offered its commodity products and services at the lowest price in the industry, it would be delivering the desired value to its external customers. The value proposition therefore had to emphasize “accurate, timely processing” and “lower processing cost” for the customer. OCS, however, wanted to move beyond a pure low-price strategy to more value-added customer relationships that leveraged the value of the information services it provided. For this strategy—to expand revenue growth through new products and services—OCS management had to also recognize its role in supporting non-commodity products. “Innovative new products” and “information” about markets were components of the new strategy based on product leadership. The complete customer perspective is shown in Figure 4-2.

Figure 4-2 Fannie Mae’s Operational Excellence Strategy Map

For the internal business process perspective, OCS had to start with its traditional base of safety and soundness for operational excellence. The focal point for the enhanced operations process strategy was to create a more flexible infrastructure that would support growth, both from new products and from acquisition. A continuous process-improvement program for both existing and new products would be critical to the operational excellence theme. For OCS’s intent to move beyond operational excellence, the customer management process became highlighted. The knowledge gained by the OCS group about transaction volumes and complexity profiles enabled them to develop more cost-effective services for their customers. Similarly, information for investors about the timing of cash flows and their relationship to different investment vehicles created another asset to broaden the customer relationship. OCS personnel and Fannie Mae account managers would partner, using these information assets to enhance the customer management process. The management team defined two strategic themes for this process: “enable investor opportunities” and “leverage knowledge of our customer.” The innovation process at OCS focused on the piloting and migrating of the new opportunities. The strategy maps for the four internal process strategic themes are illustrated in Figure 4-2.

The learning and growth strategy at OCS defined a set of strategic skills to support each of the four strategic themes. The people perspective was critical to complete the transition from Fannie Mae being a government-type bureaucratic organization to a flexible, customer-focused one. The new strategy would require people to change behavior and responsibilities. For example, the “improve operating capability” theme required improved skills in customer relations, teaming, and communications. These tasks had to be clearly communicated, recognized, and rewarded. The technology plan focused on capturing and sharing knowledge about customers, including knowledge management of the customer database and integration with the transaction processing system. The supporting culture focused on the creation of both accountability and achievement.

Once the OCS Balanced Scorecard had been developed, Larry Barnett, vice president of security trading operations, recalled, “The heavy lifting could really begin.” It had to become imbedded in the OCS culture and management system. OCS selected “theme owners” for the four internal strategic themes. The theme owners organized discussions at which people from various departments and functions came together to talk about how they could contribute to the theme, not just report on their individual function and department. Discussions on new investments, initiatives, hiring, and skill development of existing personnel were tied back to how such actions contributed to accomplishing the strategic themes. The Balanced Scorecard became the agenda for monthly meetings and discussions. Managers helped frontline personnel to define local, departmental measures that would, in some cases, be reported daily to support the high-level divisional objectives and measures.

Another operational excellence strategy was implemented at Nova Scotia Power, Inc. (NSPI), a regulated, investor-owned utility that supplies electricity to the Canadian province of Nova Scotia. In 1998, NSPI had 1,650 employees, revenues of C$750 million, and a net margin of 12.4 percent. David Mann, formerly corporate counsel at NSPI, became CEO in July 1996, and was faced with the challenge to position NSPI for a new world of deregulation in the electric utility industry. In late 1998, NSPI was separated from nonregulated energy enterprises and placed within a newly established holding company, NS Power Holding, Inc. NSPI could not increase its prices for electricity, despite internal and external cost pressures.

Working with a strategy consulting firm, Mann’s senior management team had formulated a new strategic plan, but Mann wanted a measurement system to guide and gauge the success of the plan. In addition, NSPI had recently reorganized into SBUs, and Mann felt the need for a tool to unite the plans of the SBUs so that they would all be working toward the same overall goals. CFO Jay Forbes proposed that the Balanced Scorecard be used for these purposes. Forbes served as the executive sponsor for the development and implementation of the scorecard at NSPI.

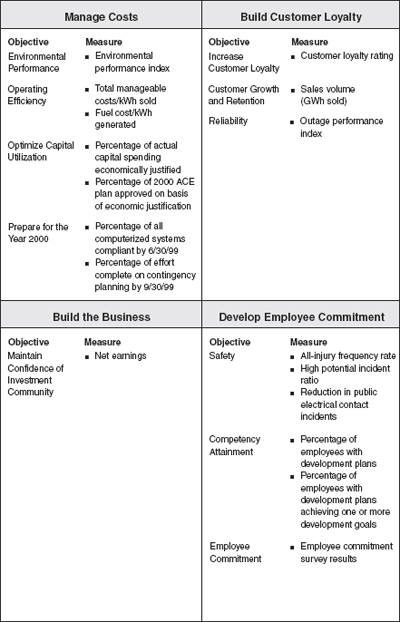

The scorecard was based on the four strategies in the NSPI plan:

The corporate-level NSPI scorecard was simple (see Figure 4-3); each of the four strategic objectives could be aligned with a Balanced Scorecard perspective. The company emphasized building customer satisfaction and loyalty and improving employee commitment while embarking on a vigorous cost-reduction program that would enable it to maintain profitability without raising rates.

The results were impressive. From 1996 to 1999, NSPI generated a sales volume increase of more than 13 percent and was able to deliver the higher revenues with 20 percent fewer employees. The combination contributed to a productivity improvement of nearly 36 percent, as measured by kilowatt-hours of sales per employee. The cost reductions were not achieved at a cost to the customer, the community, or employees. Customer satisfaction increased steadily; power interruptions and customer hours without power decreased to record low levels; environmental incidents decreased; and accidents dropped by 25 percent to a record low. Employee commitment surveys showed large year-to-year increases. Forbes commented on this performance for a regulated utility that had to absorb significant external price increases for fuel and for government-mandated pension charges:

We have held price constant since 1996 despite cost increases in some areas. We have been able to absorb these increases and earn our allowed rate of return because we’ve been able to manage our costs more effectively through the use of the Balanced Scorecard. At the same time, we’ve been able to increase our safety, improve our reliability, improve customer service, and enhance our employee commitment.

The strategy maps we have discussed so far give a snapshot of the organization’s strategy. They represent the simultaneous strands that organizations manage to achieve their strategic objectives. Companies that are introducing new technologies and radically new products and relationships must also manage strategic themes over time. Initially the company may focus on productivity and process improvements to deliver short-term cost savings. Over time, the emphasis shifts to revenue growth, with new product introductions and new relationships with customers. The strategy culminates with the company occupying a new strategic niche, providing new and powerful value-added products and services to its customers.

AgriChem, a U.S. manufacturer of agricultural chemicals, provides a good illustration of the power of managing a time-sequenced set of strategic themes.5 AgriChem blended active ingredients into packaged products. It sold the packaged chemicals to distributors, who sold and supplied farmers around the country. In 1993, AgriChem formulated an aggressive new three-year strategy to transform the value chain to its end-use customer, the farmer. The strategy consisted of five overlapping strategic themes:

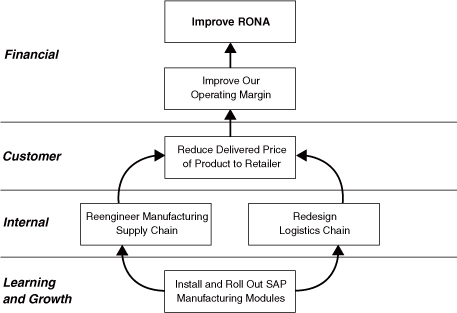

AgriChem developed separate strategy maps for each of the five themes so that it could focus on each one at the appropriate point in the three-year period. The goal was to double the company’s high-level financial metric, return on net assets (RONA).

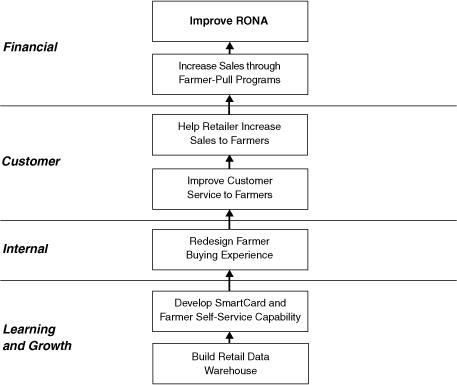

The first theme—reengineer manufacturing (see Figure 4-4)—was to deliver substantial financial benefits from cost reduction and enhanced productivity. This theme emphasized a new production planning software system (in the learning and growth perspective) that would produce efficiencies in supply and distribution (internal business process objectives). These improvements would enable AgriChem to reduce prices to its distributors (customer perspective) while still increasing its operating margins (financial perspective).

As AgriChem consolidated its gains from internal cost reduction and productivity improvements, it could start to improve the distribution system to its retailers (see Figure 4-5). Installing additional software modules that were focused on sales and marketing operations launched this second theme. The modules provided better information from retailer sales back to manufacturing operations. The close linkages enabled a breakthrough in operations. Orders from farmers came during a narrow time interval at the start of the growing season. Historically, AgriChem had to forecast how much and which products the farmers would order each year and stock retailers in advance. Even with good forecasting routines, the process still led to costly overstocks and understocks each year. If AgriChem could align its newly streamlined manufacturing processes (the first strategic theme) to orders received by its retailers from farmers, the company could manufacture much more product to order rather than to stock.

Figure 4-4 Reengineer Manufacturing

The third strategic theme (see Figure 4-6) emphasized improvements in the company’s retailers’ operations. By deploying some of AgriChem’s new information technology for retailers, the company could reduce both its own cost and capital requirements and those of its retailers. As AgriChem became the retailers’ most profitable supplier, the retailers would source more product from AgriChem, leading to higher profits for both.6

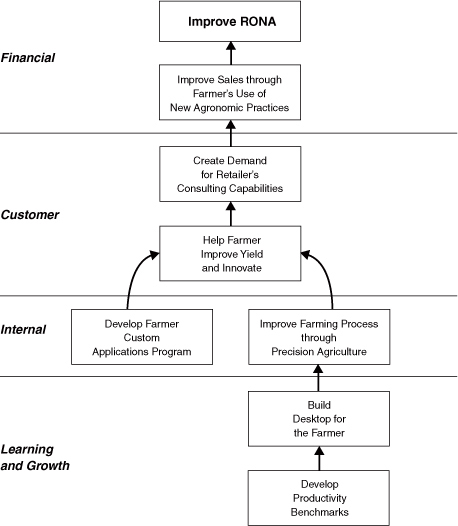

The first three strategic themes focused on improving AgriChem’s operations, AgriChem’s relationships with its retailers, and then retailers’ operations. The next breakthrough in performance would come from using information technology to create efficiencies for farmers (see Figure 4-7). AgriChem wanted to develop a SmartCard for farmers that would link to AgriChem’s extensive database on individual farmers’ operations. The farmer would interact with AgriChem’s computers and databases to select the desired chemicals for the upcoming season. The farmer could then drive to the local retailer and identify himself with the SmartCard, and the appropriate chemicals would be automatically dispensed into the farmer’s containers. This new process saved time, packaging, and inventory for the retailer and provided great convenience to the farmer.

Figure 4-5 Redesign Interface with Distributors

The fifth and final strategic theme was the most ambitious and experimental of all (see Figure 4-8). This theme deployed advanced information technology directly to the end-use consumer by providing the farmer with desktop and tractor-top capabilities. AgriChem would develop a farmers’ database enabling each farmer to forecast, at his desktop, the chemicals he could best use based on his crops, land characteristics, terrain, planting patterns, and weather trends. The final program could be loaded on the tractor itself, which would automatically dispense seeds, fertilizer, and protection, using precise positioning information from global positioning satellite equipment. This precise planting program eliminated gaps and duplication of dispensing seed and fertilizer as the farmer traversed his fields. The revolutionary farming process in this fifth strategic theme had the largest potential for increasing AgriChem’s revenue growth by forging an intense value-added relationship with end-use consumers.

Figure 4-6 Improve Distributor Operations

AgriChem’s full strategy map is shown in Figure 4-9. At its foundation were employee-focused programs to develop relationship-building skills and incentive programs and customer focus. While Figure 4-9 appears quite complex, it becomes simpler to both understand and manage when it is viewed as a sequential process moving from right to left on the diagram.7 The later themes—which are more revenue-based and closer to the end-use consumer—build on and leverage the competitive advantages from the cost reductions and distribution efficiencies achieved in earlier stages. The vertical strategic themes of Figures 4-4 to 4-8 also provide a powerful accountability model. The company appointed a manager for each of the five strategic themes with the responsibility for delivering the performance targeted for each theme.

Figure 4-7 Invent New Distributor-Farmer Interface

Company managers reported that the near-term operational improvements from the first two strategic themes yielded positive cash flow and gave employees confidence that helped to sustain investments for the more experimental revenue growth themes, especially numbers four and five. The company, in three years, doubled sales, increased RONA from 16 percent to 50 percent, and forged direct, long-term relationships with its end-use consumers.

Figure 4-8 Pioneer Precision Agriculture

Figure 4-9 AgriChem’s Strategy Map

In this chapter, we have illustrated how Balanced Scorecard strategy maps get constructed from the underlying strategy of the organization. The exemplar organizations developed and used the scorecard to translate their strategies into linked cause-and-effect relationships that could be easily understood and communicated to the entire organization. The process made the strategy transparent. Readers of the scorecard could infer the strategy from looking at the scorecard objectives and measures, and the linkages in the Balanced Scorecard strategy map.

1. Disguised company name. Quotations from National Bank personnel may not be reprinted without permission of the Harvard Business School Press.

2. The fees and interest income earned from OFS’s customers were attributed to the product divisions (checking accounts, savings accounts, credit cards, and so on). OFS covered its costs by charging nominal fees to the product groups based on customers’ online transactions.

3. See the discussion of Internet economics in Carl Shapiro and Hal R. Varian, Internet Rules: A Strategic Guide to the Network Economy (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1998).

4. See Jeffrey R. Williams, Renewable Advantage: Crafting Strategy through Economic Time (New York: The Free Press, 1998), for discussion of how competitive strategy evolves at different rates in different industries.

5. We are grateful to Francis Gouillart, president of Emergence Consulting, for this example. Mr. Gouillart has been a leader in using the time-based themes approach of the Balanced Scorecard for describing strategy.

6. One can see here the role for activity-based cost systems so that retailers can understand the relative profitability of products sourced from their various suppliers; see Robert S. Kaplan and Robin Cooper, Cost & Effect: Using Integrated Cost Systems to Drive Profitability and Performance (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1998), 203-10.

7. Of course, the earlier themes would not be forgotten once their initial targets have been achieved. AgriChem would continue to improve its internal cost and productivity, its distribution to retailers, its dealers’ processes, and its farmers’ buying experiences.