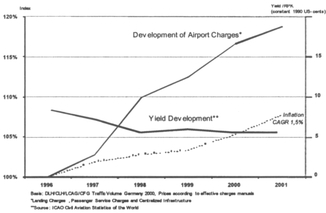

Figure 9.1 Cost/Yield - development

Michael Klenk

Airlines have long been used to the cyclical nature of their industry given that economic upswings and downswings in world economy have increased in both frequency and amplitude while at the same time air traffic demand has tripled in the last 35 years. Current trends and developments seem to indicate that the route will become even more turbulent. In the year 2002 we have seen two major US carriers - United Airlines and US Airways - having to undergo Chapter 11 procedures. Taking a look at the performance of European Airlines in 2002 is also sobering. Passenger kilometres of AEA1 Airlines was 4.6 per cent below the disastrous 20012 levels - although some like Air France, Lufthansa and in continental Europe Ryan Air were able to deliver satisfactory results. European tour operators (Thomas Cook, TUI, My Travel etc.) are facing their biggest crises ever with turnovers and customers down by 8-10 per cent compared with 2001. The tourist sector is especially suffering from weakening economies - headed by Germany - in some of the member states of the European Union, as well as international conflicts.

The increasingly globalised world seems to have entered an apparently longer period of political instability with war and terror risks becoming an almost "daily" and very burdensome "routine" on a worldwide scale; burdensome especially for enterprises involved in aviation. The instability is reflected in a second Gulf War, military action in Afghanistan, conflicts between Pakistan/India, North Korea/US, and the politically destabilised countries in South America such as Venezuela, Bolivia and Argentina, the loss of major destinations for many tour operators due to terrorist threats in Indonesia, Tunisia, Morocco and Egypt have shattered the industry's global perspective tremendously. On top of these, the outbreak of the SARS vims has lead to an almost complete breakdown of international air traffic from and to China.

Airlines in the European Union are not only facing these above-mentioned challenges but also a regulatory policy, promoted strongly by the European Commission, in the environmental and security sector that has two effects: higher costs and lower productivity for airlines as well as airports.3

Furthermore, the airline market has become increasingly competitive, with Low Cost Carriers successfully entering and expanding in the domestic markets of established network carriers such as British Airways and Lufthansa. With their point-to-point operations in geographically confined markets they are obviously less prone to global economical and political distortions. Whereas many airports by and large still seem profitable and resilient to the overall industry sector's upheaval, the entrepreneurial survival of airlines has become more obvious than ever before with more than 30 airlines worldwide having to undergo insolvency procedures since September 2001.4

Overall, one can certainly argue that the air traffic sector as a whole is facing significantly higher risks with regard to the demand of its products and a substantial lower amount of planning reliability.

In light of the given economic, political and specific market background, the question arises as to whether the commercial relations between airports and airlines need to be adapted to the changing environment. Such a change may be necessary in order to provide a long-term sustainable business strategy for both. The significance of the question becomes apparent when taking a closer look at the nature of this relationship as not being one of an ordinary supplier and its customer. What is different in comparison to other commercial relations is the high mutual dependence on each other - one cannot exist without the other and each produces an indispensable "upstream" or "downstream" product for the other's business activity: The airport is providing the necessary infrastructure for the operation of an aircraft, which cannot be operated outside an airport's facilities, and it is the airlines' aircraft which deliver the essence - dare one say the spirit - to almost 100 per cent single purpose sites. And it is without doubt that the airlines' schedules shape the corporate position of most airports - a fact that holds true for Low Cost Carriers and even more for the networking carriers. Together the airports' and the airlines' respective services - basically infrastructure on one side, and air transport on the other - are actually combined to the joint product "air travel". The relation may as well be characterised as a "System Partnership".5

Another specific trait of their co-existential link is that both are living from the same primary revenue source - which is the passenger.6 The revenue stemming from a passenger's purchase of a ticket has inter alia of course to cover a flight's operational expenses, amongst which airport charges play an important role. Being significant costs for airlines on one side, charges deliver a crucial income source for the airport on the other side. But it is also the departing or landing passenger who provides for an airport's non-aviation revenues when spending money at retail shops - thus stimulating concession fees - or using an airport's parking sites for example.

However, delivering a joint product and living from the same revenue source does not mean that airports and airlines gain their proceeds under the same conditions. Actually the conditions differ considerably.

With regard to the airports - at least when referring to the most common charges regulated in European Countries - it is evident that they are entitled to calculate their aviation revenues according to the cost-plus-regime. Cost plus is understood as a method to calculate prices solely on the basis of cost incurred plus a certain amount of return on the capital employed without the need to set prices according to competitive influences. Basically, in most regulatory systems there is no incentive for airports to conduct any target costing approach in the process of setting charges.7

On the other hand, airlines are facing growing and intensive competition and have to earn their revenues under lull market conditions. It is the market which defines the ticket prices (= revenues) and establishes what is affordable. As aircraft capacity will be operated where the best cost/revenue ratio can be found and with airport costs having a decisive impact on this ratio, competitive airport costs have become more relevant for the entrepreneurial survival of both airlines and airports.8 However, since the mid 1990s, steadily declining yields and a continuous increase in airport charges have been shown to be a critical path for airlines (see Figure 9.1).

Hence, commonly applied airport pricing schemes not only seem to fail to provide for a balanced mitigation of interests, but they also constrain the ability of the whole aviation system to respond to the ever increasing ups and downs of the economic cycle. These business cycle fluctuations will become even more important in the future. In the long run this does not follow the idea of a sustainable partnership. Therefore, an alignment of the commercial relations seems to be due. New models for risk- and profit-sharing have to be found.

We have argued above that the incumbent systems fail in delivering balanced results for both system partners and they especially lack the necessary flexibility to adapt to the changing market requirements. As the degree of exposure to market forces is different between airports and airlines, one conclusion might be to bring in more market-based elements in the commercial relationship.

The most significant market element we know is the demand for air travel, expressed as the number of enplaning/deplaning passengers using an airport.9 This provides an opportunity for an airport to shift from solely cost-based airport charges to more market oriented ones. The natural linkage is to the development of the number of passengers. Today, in most cases, airport charges are already linked to the number of passengers being on board the departing or landing aircraft. At the same time, many airports also levy charges according to a fixed aircraft weight the so-called Maximum Take Off Weight (MTOW) which is laid down in the aircraft's certificate. However, it is questionable, if the current structure of charges adequately reflects the market conditions. The following example may illustrate this.

Figure 9.1 Cost/Yield - development

In Germany, the average ratio between passenger-related charges and fixed MTOW related charges accounts for 50:50.10 Admittedly this is simplified but in the end it is still true: This means that 50 per cent of the revenues could still be earned by the airport even if not a single passenger was on board the departing or landing aircraft in a respective period and given no schedule adjustments were made by the airline. In other words: Whereas an airline would operate without any revenue an airport may be relatively lucky to obtain at least half of what was expected. In a state of growing fluctuations and on a long term scale, even more extreme volatility of air travel demand adjustments seem to be appropriate in order to find a new balance.

Therefore, one element of a new approach might be to design the structure of charges schemes to be more variable, i.e. more on a per passenger base. Of course, some may argue that this simply means economically shifting market risks onto the airports. It certainly cannot be denied that a greater participation of an airport in the market risk would be the case. But would the only consequence of such a change be to make airports more susceptible to an economy's downturn effects? Or could there even be benefits for both airports and airlines, a so-called win-win situation?

Without in-depth discussion a more variable design of charges might have the following features.

Figure 9.2 Commercial perspectives of more variable charges

Passenger-related environmental airport charges - especially if they are made visible in airline tickets or even in catalogues of tour operators - could accomplish numerous effects; they make the external costs of air travel visible to those who demand travel - thus following the often-postulated concept of polluter pays environmental cost pricing.

This would be in contrast to concepts currently discussed on a European Union level,14 which propose inter alia to introduce in addition to already existing environmental charges, en route charges for CO2-emissions15 and link noise charges exclusively to engine performance, and fixed charges.

In contrast to these ideas a more variable system for environmental charges would have several advantages:

It goes without saying that such a concept is not to be misunderstood as simply another source of tax revenue. Given the current business environment it would, from an airline perspective, only be feasible and acceptable, if the implementation was revenue (cost) neutral with regard to the individual airport concerned. The fault critics often seem to find with this approach is a clear incentive function. This is not convincing as airlines - due to competition - have a natural business habit to keep operating expenses as low as possible and are therefore interested in a good environmental performance. This holds true for all costs, whether they are fixed or variable. The decisive difference in the current widespread concepts of fixed environmental charges is that, in a variable system, airlines are only burdened if a corresponding revenue exists.

Although not being perfect and certainly to be developed further, a concept of variable environmental charges seems at least to be a feasible approach in reconciling environmental objectives with economic interests - which is not often accomplished nowadays.16 The latter - self-explanatory - is in the mutual interest of airports and airlines, both being confronted more and more with regulatory issues in the environmental sector.

Summing up the basic features of a more variable approach to charges schemes one may draw the following conclusions.

It may therefore be a worthwhile approach to be taken in the commercial relations between airports and airlines.

In April 2002, Frankfurt Airport (Fraport) and the Board of Airline Representatives in Germany (BARIG),17 the German Air Carrier Association (ADL)18 and Lufthansa signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on the future development of airport charges for the term between the year 2002 and 2006. The MoU concluded negotiations of more than one and a half years. These negotiations had been severely interrupted twice: first, when Fraport unilaterally suspended talks in early summer 2001 with regard to its ongoing Initial Public Offering (IPG) with roughly 30 per cent of the airport stake being transferred to private owners.19 Second, only a couple of days after talks had been resumed, the events of 9/11 led to a suspension until January 2002. Those interruptions show that the genesis of the MoU was anything but a smooth one. The parties were able to finally conclude the MoU more than 8 months after 9/11, despite the substantial blurring of the economic perspective of air traffic from a clear growth scenario to a rather clouded outlook 20 The MoU has certainly been catalysed by the regulation of Hamburg Airport which was established in 2000 in the course of the privatisation process.21 Similar to Hamburg, it was important to the airlines that along with privatisation of Frankfurt Airport a mechanism was established to prevent monopoly abuse and make privatisation acceptable.

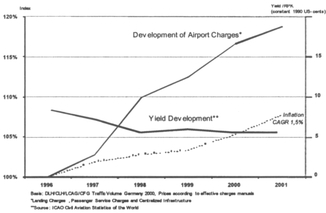

Legally the MoU can be perceived as a multilateral contract under private law. In Germany, the commercial relation between airports and their users is also subject to private law. Airport charges and the respective services connected to them hence share the same legal nature. Nevertheless, airport charges are subject to a formal approval by the local government.22 In the case of Frankfurt, the responsible body is the state of Hessia's ministry of economic affairs.23 The approval of charges by the local authority, in contrast to the commercial relation between airport and airlines, belongs to the public law regime. In consequence, the granted or missing approval of charges is only effective in the relationship between the authority and the airport and relates the question of supervision. The regulatory approval of airport charges legally is not constituent for their effectiveness in commercial relations between an airport and its users. 24

Therefore, Fraport and the negotiating airlines first sought to settle matters in a private law contract, the MoU.25 The contents of this contract subsequently have to be fully transferred - into an additional 5 year public law contract - to be concluded between the regulator and the airport. The public law contract replaces the formerly needed yearly governmental approval of the charges level for the duration of 5 years (2002- 2006).26 The structure of charges is later subject to the consent of a special panel, called the Review Board, in which the airlines, the government and the airport are represented. If no agreement between airport and airlines can be reached about structural changes, the airport can launch, as in the past, a formal request for approval to the local government (Figure 9.3).

The key elements and, in many respects, new approaches of the Frankfurt Charges Framework are the following.

(a) The scope of the framework comprises all aviation revenues that the airport is entitled to levy according to the respective national legal stipulation which is § 43 Luftverkehrszulassungsordnung (§ 43 LuftVZO). Practically, it includes the fixed, the variable and the parking charges. However, it does not (yet) contain rules concerning the charges for centralised infrastructures according to the EC Directive 96/67 on the liberalisation of the ground handling market in the European Union.27

As their nature is a clear monopolistic one and they are not subject to any governmental approval it would have been desirable from an airline perspective to have them under the contract, too. So far, the parties have agreed to negotiate as to how to incorporate charges for centralised infrastructure into the contract. Explicitly not included are any potential additional costs of the airport's extension programme for a fourth runway and new terminal in Frankfurt.28 Here, too, the opening of the scope of the agreement to such costs was agreed upon with the provision that the exact implementation is a matter for future negotiations at due time.

Figure 9.3 Frankfurt charges model: history and construction

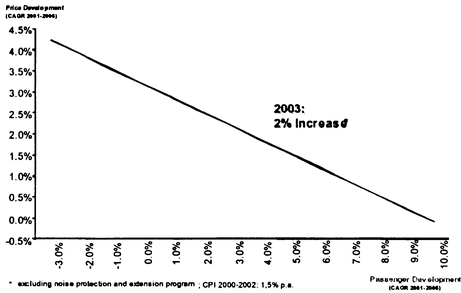

(b) The heart of the Frankfurt charges framework is the price setting formula. Unlike Hamburg, which has a CPI-x formula, the negotiating parties chose a risk-sharing model that strongly links the level of charges to the development of passenger demand. The basic characteristics are as follows.

Airlines have a 33 per cent share in additional revenues generated due to extra passenger volume compared to the parties' projections. This amounts to a 67 per cent windfall profit for the airport. The other way round, i.e. in times of traffic decline, the airlines bear the risk of a passenger shortfall merely to the extent of 33 per cent, which limits the airport's right to compensate for loss of traffic through potential increases in charges.

Figure 9.4 Frankfurt - Model

The effects of the formula are illustrated in Figure 9.4. In contrast to formulas at other places such as Hamburg or Vienna, which link the development of the charges level to the passenger volume only after certain thresholds are reached, the Frankfurt Model provides a continuous sliding scale.

(c) A special Review Board was established in which the negotiating airlines, the airport and the local government are represented. The Review Board meets regularly and has the task of providing in-depth, efficient and transparent consultation on the contract. All matters concerning the implementation of the agreement shall be discussed here such as, for example, possible structural shifts of charges or the application of the formula, and brought to a settlement. Special provisions are laid down to ensure that comprehensive data are provided by the airport with regard to development of traffic, productivity and investments in order to accomplish a meaningful consultation process.

(d) The framework also contains provisions for a noise protection fund which the local government obliged Fraport to establish effective 2002. The final settlement of this matter was preceded by bleak expectations on the funding and its conditions. Four months after 9/11 the airlines saw themselves economically incapable of bearing the full financial burden of the programme until certain conditions had been met. Among which, the conclusion of the MoU and the incorporation of the funding formula in the contract were the most important. The parties finally agreed upon the following conditions:

(e) In addition, the framework contains a clause in which airlines are waiving any legal action against the level of charges. It has addressed the issue of quality with a commitment by Fraport to maintain and develop a competitive level of quality complying with the international standards of a hub airport, but leaves the definition of detailed parameters to a working group.

The Frankfurt charges framework shall be briefly assessed from three different angles - from a regulatory, economic and political perspective.

(a) From a regulatory point of view the Frankfort model shows that even within an entrenched legal environment new and future oriented solutions are possible. What is necessary is a common will of all parties involved and a mutual understanding of the overall benefits of the chosen approach. This definitely is easier said than done: if there had not been a certain bargaining momentum at the beginning of the talks between Frankfurt airport and the airlines, which gave the latter a certain wind of opportunity - triggered by a mixture of political issues simmering around the public discussions of the airport extension, some hard economic facts, legal disputes at other airports and the publicly well noticed privatisation process29 - the Frankfurt framework would not have been possible. Once talks had started the local government - to the surprise of the airlines - began to support the conclusion of the MoU and finally acted as a facilitator in some matters. So the route to the charges agreement in Frankfurt was definitely not - unlike Hamburg - a well coordinated "top down" approach to establish a new mechanism of economic regulation. It was indeed a rather itinerant journey, which showed that a commonly accepted culture of such solutions was not yet existing. Therefore, discussion and promotion of models for independent regulation are still necessary and needed, given the fact that the Hamburg as well as the Frankfurt system are time limited.

(b) Evaluating the economic aspects of the Frankfurt framework in retrospect one can clearly see that Frankfurt is one step beyond Hamburg. Times have changed since the Hamburg contract was concluded at the beginning of 2000 and therefore the parties had to find a solution to cope with the effects of traffic decline. They actually dispensed with the famous CPI-x formula and found other ways to put their commercial relationship on a new platform. One year after implementation, it seems too early for an in-depth economic analysis of the framework, but some general remarks may be made.

The depicted variable elements - also in the environmental sector - better reflect the idea of a joint product air travel than the old regime. They have largely facilitated the funding of the noise insulation programme and help airports and airlines to better mitigate environmental concerns with regard to the planned extension. The whole set of stipulations in their combination and mutual effects seem to provide for a - albeit not perfect - time adequate and certainly more comprehensive commercial approach. It remains to be seen whether the parties are able to reap the benefits to the sake of each other's prosperity.

(c) Assessing the political implications, a difference has to be made between an internal view, i.e. in a closer sense the psychological effects between the negotiating partners, and an external look at the matter, i.e. the significance of the Frankfurt model for the discussion at other airports in Europe and for air transport policy.

Growing cyclical fluctuations in the air traffic sector in combination with the, to be expected, vast changes of the worldwide political agenda, demand - from airports, airlines and governmental authorities - more willingness and speed to adapt. This is essential if one is to sustain the economic welfare of air traffic for the economy as a whole and to acknowledge international mobility of people (and goods) as a fundamental and necessary principle in a globalised world. As recent developments are very likely to become long term trends, it seems high time to re-align commercial relations between airports and airlines according to current market demands. Although confronted with a difficult environment in Frankfurt a path has been chosen that seems to provide a setting of parameters that might be suited for the airport and its users to weather looming difficulties in their common stride ahead.

1 Association of European Airlines (AEA).

2 Association of European Airlines official press release, February 5, 2003

3 White Book of the European Commission on Transport, 2000.

4 United Airlines and US Airways are currently undergoing Chapter 11 procedures; American Airlines, the world largest airline, is still jeopardized to be subjected to Chapter 11 procedures. Air Canada, the largest Canadian airline, also faces similar procedures at the moment.

5 P. Gerber, Journal of Air Transport Management 8 (2002) p. 29-36 (36).

6 Cargo provides revenue to airports and passenger airlines but the proportions are relatively low in comparison to passenger revenue.

7 H.M. Niemeier, Journal of Air Transport Management 8 (2002) p. 37-48 (42).

8 Airport charges which are subject to § 43 LufVZO and equivalently comprised of the Frankfurt charges model account for up to 16 per cent of direct operational costs of a domestic flight and 6 to 10 per cent of intra-European and international flights. Taking into account total turn around costs at an airport (airport charges, charges for centralised infrastructures, handling fees, security fees; see footnote 13) including ATC charges, the ratio would be the following: total turnaround costs on domestic flights: up to 40 per cent; intra-European and domestic: between! 8 to 30 per cent. All figures refer to Lufthansa traffic in the year 2002.

9 Other measurements of demand could be movements of aircraft, take off weight or cargo transported. However, the author chose the measurement of passengers using an airport since this is still the most important economic value driver for airlines as well as for airports.

10 Aircraft parking charges are not specifically taken into account but treated as MTOW charges. As aircraft parking charges do not correlate to the number of passengers their economic effects are the same as MTOW charges: they are fixed and not variable.

11 H.M. Niemeier, Journal of Air Transport Management 8 (2002) p. 37-48 (38).

12 Ideally airports and airlines agree on a risk and profit sharing model. This is what the "Frankfurt Charges Model" comes close to.

13 It has to be stated clearly that in competition among airlines, respectively between airline alliances - especially when competing for transfer passengers - the total cost of an aircraft's turn around at an airport are decisive. Total turnaround costs consist of all costs incurred when an aircraft lands at an airport, picks up passengers and departs. Total turn around costs include: airport charges, charges for centralised infrastructures, handling fees, security fees, rents. Therefore, passenger charges can not "endlessly" be passed through to the passenger without producing a competitive disadvantage in the composition of the ticket price. Actually there are clear hints that even small differences in the ticket price between competing airlines influence a passenger's choice for an airline and can only to a limited extent be compensated by an airline's "premium" (Frequent Flyer Programmes, reputation etc).

14 White Book of the European Commission on Transport, 2000, p. 45. To avoid misunderstandings: the criteria for defining the exact level of a passenger-related environmental charge and a necessary differentiation would still have to be found (long haul versus short haul aircraft, gaseous emissions during take off and landing cycle etc). Once such criteria are set up the author proposes to express and levy the price on a per passenger base.

15 These are to be administered by a European body - perhaps Eurocontrol.

16 It would be even conceivable that variable airport charges are used to recycle their revenue into environmental projects (noise insulation programmes, environmental protection measures etc), if certain criteria were cumulatively met, such as: competitive level of charges, transparent use of proceeds, equal financial participation of airport (with non-aviation revenues), means of last resort to avoid strict operational restrictions.

17 BARIG represents 107 German and foreign air carriers that are operating services in Germany.

18 ADL represents the German charter and leisure carriers.

19 In fact the MoU was yet ready to be signed at the end of April 2001 when Fraport Executive Board decided not to sign the fully negotiated text of the agreement and suspended talks. As a result, relations between airlines and airport worsened substantially until talks were taken up again.

20 It deserves notion that the negotiating parties on behalf of the airport in the end managed to overcome scepticism towards the agreement within their own organisation.

21 H.M. Niemeier, Journal of Air Transport Management 8 (2002) p. 37-48.

22 H.M. Niemeier, Journal of Air Transport Management 8 (2002) p. 37-48 (40).

23 It has to be noted that the state of Hessia owns a 31 per cent stake in Frankfurt airport and keeps the chair in the supervisory board of Frankfurt Airport - as do many other approval bodies for airport charges in Germany at other airports. German private corporate law obliges members of the supervisory board not to act against the interest of the represented company. From an airline perspective, this regulatory setting is an ambivalent one that cannot be perceived as independent and "neutral".

24 It has to be conceded that the approval, despite the described legal implications does have a strong factual effect in a way that airports usually in Germany have so far not commercially implemented charges unless they had governmental approval.

25 In Hamburg, the price cap regulation introduced in 2000 - the first ever in Germany - was nota bene established without prior civil law contract. As the acceptance of the price cap regulation was an obligatory requirement in the tender for Hamburg Airport's privatisation and hence strictly enforced by the Ministry of Economic Affairs, no prior contractual agreement between airport and airlines was necessary.

26The full text of both agreements, the public contract as well as the MoU, are published in the Journal "Nachrichten fur Luftfahrer" Part I NfL 328/02, http://www.dfs.de/dfs/deutsch/inhalt/aviation_services_business.

27Article 8 of EC Directive 96/67 defines Centralised Infrastructure Facilities as follows;

Official Journal of the European Communities:

"1. Notwithstanding the application of Articles 6 and 7, Member States may reserve for the managing body of the airport or for another body the management of the centralised infrastructures used for the supply of groundhandling services whose complexity, cost or environmental impact does not allow of division or duplication, such as baggage sorting, deicing, water purification and fuel-distribution systems. They may make it compulsory for suppliers of groundhandling services and self-handling airport users to use these infrastructures.

2. Member States shall ensure that the management of these infrastructures is transparent, objective an non-discriminatory and, in particular, that it does not hinder the access of suppliers of groundhandling services or selfhandling airport users within the limits provided for in this Directive".

28 However, in the meantime the parties have already taken arrangements on how to handle costs incurred with the airport's necessary planning procedures and audits with the competent external agencies for the extension programme. They are considered to be preliminary costs that have to be regarded separately from financing the extension itself.

29 Adding to that, the privatisation of Amsterdam Schiphol which Fraport is linked to in the so-called "Pantares" Alliance, was put off by parliament in the Netherlands. "Pantares" is the name for the alliance between Fraport and Schiphol it was postponed.

30 Worth noticing in this context is the fact that some airports announced vigorously they were not to accept a "price cap" regulation but showed interest to conclude a MoU like the Frankfurt one.