CHAPTER

002

The Bonds of Philadelphia

Blue-eyed, brown-haired James Bond was born into money at the dawn of the twentieth century. Unlike a certain spy of the same name, he went by “Jimmy” or “Jim” his entire life. The twentieth century would be known as the American century, shaped by two cataclysmic wars and incredible technological advances—from automobiles and airplanes to high-powered computers and a ubiquitous internet—and Bond would live through nearly nine decades of it.

The Bond family fortune was enormous, but for the youngster it was ultimately far less significant than its location—Philadelphia, a city long known as the cradle of American ornithology. Thanks to such pioneer ornithologists as author-illustrator Alexander Wilson, the legendary John James Audubon, John Cassin, and museum founder Thomas Say, Bond grew up in an environment where birds and natural history were revered.

Jim Bond was born into a long line of Bonds that dates from as early as the 1600s. His ancestors are said to include Thomas and Phineas Bond, brothers who played key roles in founding the American Philosophical Society, the University of Pennsylvania, and Pennsylvania Hospital. (Bond once told David Contosta, author of The Private Life of James Bond, that “Phineas Bond was the most important member of our family.”)

The family tree branched into Uruguay in the 1800s, when, according to Contosta’s biography, at least two Bond brothers born on the East Coast lived in Montevideo. One was Joshua Bond, the American consul there. The other was Dr. James Bond (Jim Bond’s great-grandfather), whose son Francis (Jim Bond’s grandfather) also became a doctor and married Sarita Josefa McCall, daughter of a Spanish diplomat serving in Mexico. Francis and Sarita lived in Uruguay and had three children, the youngest of whom was Jim Bond’s father, also named Francis, who moved to Philadelphia in the 1880s as a teenager.

Young Francis (Bond’s father) quickly worked his way up the social and financial ladder. In 1892, at age twenty-six, he became one of three founding partners of Edward B. Smith & Company, with a seat on the local stock exchange and connections to the wealthiest Philadelphians. Decades later, during the Great Depression, the company merged with Charles D. Barney & Co. to become Smith Barney, one of the largest investment banks in the world.

Francis Bond cemented his social and financial position in 1896 with his marriage to Margaret R. Tyson, cousin of artist John Singer Sargent and granddaughter of John A. Roebling, designer and builder of the Brooklyn Bridge. The wedding, in the heyday of the Gilded Age, was big news.

Jim Bond told author David Contosta that he was a descendant of notable early Philadelphians Phineas and Thomas Bond (above). Portrait by Kevin P. Lewellen, courtesy of the Thomas Bond House in Philadelphia

Francis E. Bond, Jim’s father, was a partner at E. B. Smith, which later became Smith Barney. Courtesy of Gwynedd Mercy University

The High-Falutin’ Phillies

In March 1903, Francis E. Bond joined a group of millionaires who purchased the Philadelphia Phillies. A Pittsburgh newspaper reporting on the sale described Bond as “cotillion leader, beau and arbiter of the exclusive assembly set that rules Philadelphia society.” Other owners of the Philadelphia Base Ball Club and Exhibition Company included W. Lyman Biddle (“He’s a Biddle, and hereabouts that’s enough”), Robert K. Cassatt (“son of the great president of the great Pennsylvania Railroad”), and James W. Pau Jr. (“of the house of Drexel”).

The Baker Bowl in Philadelphia was the scene of a tragic bleacher collapse in 1903, when Bond’s father was an owner of the team. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-DIG-ggbain-20087]

The wealthy new owners were soon mocked by an anonymous writer for the Washington Times, who wrote: “Should the venture prove successful—and there is no reason why it should not—the future game will be reported in newspapers something like this:

One of the most fashionable functions of the season was yesterday’s game at the Philadelphia Ball Park. It was the occasion of the debut of several charming West Walnut Street belles, and the toilettes observed in the pavilion were exquisite, foulards and tulles predominating.

As cards for the event had been issued under the supervision of the patronesses, the crush was not too great. Tea and bonbons were served after the fifth inning, and the affair was altogether delightful.

The game itself was very interesting. When the home team came upon the field, clad in their silk hats, frock coats and patent leather shoes, there was a ripple of applause from daintily-gloved hands.

The opposing team, which was from Chicago, met with some criticism, however, from the fact that several of its members wore evening clothes, with opera hats and russet shoes.

The umpire was attired in white flannels, canvas shoes and a yachting cap, so that the entire picture was harmonious and pleasing to the eye. . . .

The game was called in the eighth inning, as there were a number of dinner parties for the evening.”

The real Phillies fared worse that year, finishing seventh with a record of forty-nine wins and eighty-six losses. Their season was also marred by tragedy. A jerry-built balcony that was part of the third-base stands at the Huntingdon Street Baseball Grounds (later known as the Baker Bowl) collapsed on August 8 during the second game of a twin bill against the Boston Beaneaters. A dozen people died, and more than 200 were injured. Fearing lawsuits, the ownership—including Bond’s father—sold the team.

The disaster, which became known as Black Saturday, was a major influence on the design and construction of twentieth-century ballparks, which relied on reinforced concrete.

The Bonds’ four-story brick townhouse at 1821 Pine Street, a few blocks from tony Rittenhouse Square, was the scene of a raft of fancy events during the social season. Francis and Margaret had three children: Margaret (Maggie), born in 1897, Francis Jr., born in 1898, and James, born on January 4, 1900.

Summers were spent on Mt. Desert Island in Maine. So many wealthy Quaker City residents summered and partied there that it was nicknamed Philadelphia on the Rocks.

To keep track of the Bonds and their wealthy friends, one only had to read the high-society section of the local papers, where they were mentioned in connection with equestrian events, dog shows, fancy balls known as assemblies, carriage parades, and a variety of other charity events.

Young Francis Jr. and Jim dressed in seashore attire. Courtesy of David Contosta

Maggie Bond died on a family Maine vacation in 1904. Courtesy of David Contosta

In early September 1904, the Bonds’ utopia came crashing down. While Margaret Bond and the three children were vacationing in Maine, Jimmy’s older sister, Maggie, fell deathly ill from a ruptured appendix. The headline in the Thursday, September 8, Inquirer tells the story: Father Raced to Dying Daughter; Philadelphia Banker Traveled Special Train and Yacht to Maine in Time to See Her. The article concluded: “The run from Philadelphia was made in 10 hours. Mr. Bond found the little girl still alive, but the physicians had given up all hope. She died yesterday morning.”

The family never recovered. At first they reacted to the tragedy by building a bigger country mansion in Lower Gwynedd Township in Montgomery County. The enormous house was designed by distinguished Gilded Age architect Horace Trumbauer, whose commissions later included the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the flagship library at Harvard University. While their new house was under construction, the family spent the spring and autumn at a nearby country estate called Spring House Farm. The Bonds’ new Willow Brook estate was so noteworthy that it merited a fawning, seven-page spread in the October 1909 issue of American Homes and Gardens magazine. The property boasted stables and formal gardens, as well as hundreds of acres of woods and fields where Jim explored and collected butterflies and bird’s eggs.

It’s unclear when Francis Sr. began to hit the bottle and to womanize, but he retired as a special partner of Edward B. Smith & Company in December 1909 and resigned from the boards of several other companies. A brief article in the Inquirer about the “retirement”—Bond was forty-six—noted cryptically that “Mr. Bond will go abroad for a year or two.”

That winter, the Bonds made an extended trip to Europe, after which Margaret Bond and her two boys spent the summer in Maine. In early 1911, Francis trekked to Venezuela’s Orinoco delta on a three-month expedition to collect birds and other animals for Philadelphia’s Academy of Natural Sciences. He did most of the hunting, and assistants took over the bird-skinning and chores.

As Robert McCracken Peck and Patricia Tyson Stroud noted in A Glorious Enterprise, the story of the academy, “Although he was not close to his father, the young James Bond could not have helped but be impressed by the acclaim given his father’s expedition (not to mention the live howler monkeys he brought back home . . .).” It was about then that doctors diagnosed Margaret with cancer. Within the year, she was dead at age forty-one.

Although she was celebrated in her wedding notice in the Inquirer sixteen years earlier as “not only a girl of remarkable beauty but a great favorite in society,” Margaret Bond received only a brief death notice in the April 29, 1912, Philadelphia Inquirer:

“BOND—Suddenly, 27 inst [this month] at Gwynedd, Pa, Margaret R. Tyson, wife of Francis Edward Bond daughter of Carroll S. Tyson. Services at Church of the Messiah, Mon 4 p m.”

Young Jim Bond had been attending the Delancey School, one of the elite schools where proper Philadelphians living in the Rittenhouse Square area sent their sons. That autumn, he and his older brother were shipped off to the exclusive, boys-only St. Paul’s School just outside Concord, New Hampshire. The picturesque, 2,000-acre campus filled with classic brick buildings was 68 miles north of Boston and more than 350 miles from twelve-year-old Jim’s home.

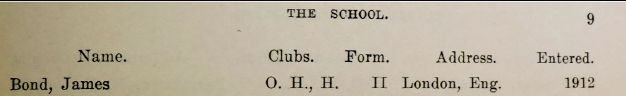

This volume of The Record of St. Paul’s School noted that Bond’s father and new wife had moved the family to England. Courtesy of St. Paul’s School

In his book Philadelphia Gentlemen, fellow Philadelphian E. Digby Baltzell, who matriculated in 1935, characterized St. Paul’s as the “oldest, largest and wealthiest of the Episcopal boarding schools,” “in the tradition of Harrow.” A noted sociologist, Baltzell may be best known for popularizing the acronym that would become synonymous with upper-crust Philadelphians—WASPs (White Anglo-Saxon Protestants).

For Jim, the school likely offered at least one major attraction. “St. Paul’s School was and is a wonderful place to bird, and it may have nurtured Bond’s interests as it perhaps did later naturalist graduates, including S. Dillon Ripley and John Hay,” says St. Paul’s alumnus Harry Armistead (more about Ripley in chapter 008, “Twitchers & Spooks”).

Noted ornithologist Francis Beach White—who taught at St. Paul’s from 1896 to 1942, kept taxidermied birds in his study and curated the school’s collection of birds from as far away as Central America and South America—was likely the perfect mentor for the young birder. A 1948 article in St. Paul’s alumni magazine noted that “those who did not have athletic practice that afternoon would perhaps go out to White’s ‘hut’ in the woods for an afternoon of observing and banding birds, or for a drive through the countryside in the old Model-T which took ruts and cross-country trails in its stride.”

Meanwhile, back in Philadelphia, Bond’s widowed father became smitten with Florence Eeles, a British widow with two children of her own. He proposed marriage and raised many Quaker City eyebrows by offering the Willow Brook estate as a wedding present. She accepted both.

The couple married in 1913 under the towering spire of St. Mary Abbots Church in Kensington, London. Florence insisted the Bonds move to England, uprooting Jim and his older brother Francis Jr. at a time when the winds of WWI billowed across Europe. A shy and lonely Jim Bond was sent off to Harrow School in North East London, where he was teased about his accent.

As David Contosta wrote in his 1993 biography, The Private Life of James Bond, “The English boys mocked his American accent, all the while insisting that America was a savage and uncouth land filled with wild Indians and the dregs of European society. The worst of the teasing stopped only after Jim became so enraged that he grabbed a pen knife and stabbed one of his tormentors in the arm. From then on, most of the boys respected him for standing up and fighting back.”

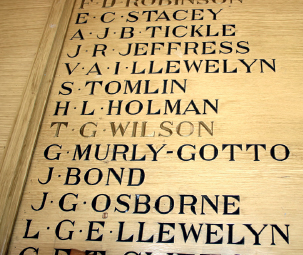

Bond’s carved name can still be seen on a wall at Harrow. Photo by Mark Ridgway

Young Bond moved to England and attended Harrow after his father remarried. Courtesy of Harrow School Archive

There are few traces of Jim Bond’s time at Harrow. He is mentioned in the school newspaper, The Harrovian, at least once, for playing on a sports team. In Druries, the house where Bond lodged, his name is carved into a board on the wall in Call Over Hall, where students assembled three times a day for roll call and notices. Druries housemaster Mark Ridgway rates Bond as a “most illustrious old boy,” along with “Lord Byron, Viscount Palmerston, Robert Peel, John Profumo, Lord Butler and a few notable cricketers.”

For most of Bond’s time at the elite school, the nation was engulfed in WWI, which claimed the lives of almost a million Britons—more than any other conflict in history. As the war raged on the mainland, it hung like a pall over Harrow. At morning assemblies the headmaster would read the names of former students on the ever-increasing lists of casualties. Bond belonged to a military training program, which put him on a track to become a junior officer. According to the Harrow School Register, Bond left in 1918 and “joined Army temporarily.”

Next, Bond enrolled at Cambridge University’s Trinity College, where he studied economics and honed his marksmanship skills as a member of a hunting club.

According to Cambridge archivist Jonathan Smith, Bond was “admitted as a Pensioner [a fee-paying student] on 8 January 1919 on the tutorial side of Gaillard Lapsley. He does not seem to have read for Honours, but for the Ordinary Degree, getting straight third classes [in examinations in history and political economy]. He graduated BA in 1922.” The archivist describes “straight third classes” as the lowest class (grade) above a fail, so Bond had done just about enough to get by.

Bond kept a hunting dog at Trinity and was the only American invited to join the Pitt Club, a small and exclusive dining club and hunting group. Future Pitt Club members included two Brits—Guy Burgess and Anthony Blunt—who went on to great infamy as part of the notorious Cambridge spy ring.

After graduating from Cambridge with a degree in economics, Jim Bond returned to his native Philadelphia in 1922 and followed his father’s career path, taking a job in the Foreign Exchange Department of the Pennsylvania Company, a major investment bank and the oldest bank in the United States. Bond was tall, thin, and handsome, with an accent that was “an amalgam of New England, British, and upper-class Philadelphia,” according to ornithologist Kenneth Parkes’s 1989 obituary of Bond.

Harry Armistead, who lived near Bond in the 1980s in Philadelphia, describes Bond’s accent as “Long Valley lockjaw—much in the same manner as the character of the millionaire spoke on the old Gilligan’s Island TV show.”

In March 1923, Bond’s father, Francis, died in England at age fifty-eight, perhaps the result of all those years of heavy drinking. Jim, the bearer of the bad family tidings, immediately notified the Philadelphia Inquirer. Years earlier, the newspaper had trumpeted Francis Bond’s every cotillion, horse show, and financial transaction. Now, the senior Bond received an obituary two paragraphs long, far longer than his first wife’s, but still a footnote. An Inquirer columnist wrote a more fitting epitaph in “Girard’s Talk of the Day” a week later: “Few men so widely known in Philadelphia only a dozen years ago dropped so completely out of it as did Francis E. Bond.”

Jim Bond at age nineteen, just before entering Cambridge University. Courtesy of David Contosta

Soon after, Jim Bond learned his father had left his entire fortune to his second wife. He was on his own, with a boring job and scant folding money in his pocket.

Bond biographer David Contosta summed up the situation: “His parents had danced at the assemblies and had been accepted into the city’s highest social circles. Jim would enjoy the same unquestioned social acceptance by Philadelphia’s social elite, a condition that he took for granted and that helped give him an air of nonchalance and social ease that few men and women ever experience. These were accumulated advantages that would assist Jim throughout his life. Yet his father’s misbehavior, his mother’s untimely death, and his own involuntary removal to England doubtlessly contributed to a shy and introspective nature.”

In short, the boy who had been an ultimate insider had become an outsider. Bond was an odd duck, to be sure, and soon to be an adventurous one.

A Remarkable Uncle

The largest influence on young Jim Bond was likely his uncle, artist Carroll Sargent Tyson Jr. (1878–1956). Tyson studied art at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts under William Merritt Chase, and then in Europe, where his friends included Mary Cassatt and Claude Monet. He began to collect their works as well as other impressionist paintings.

Tyson’s cousin was the renowned portraitist John Singer Sargent, and Tyson tried his hand at portraits as well. In 1912, he painted Helen Roebling, granddaughter of the builder of the Brooklyn Bridge. Artist and subject fell in love and got married.

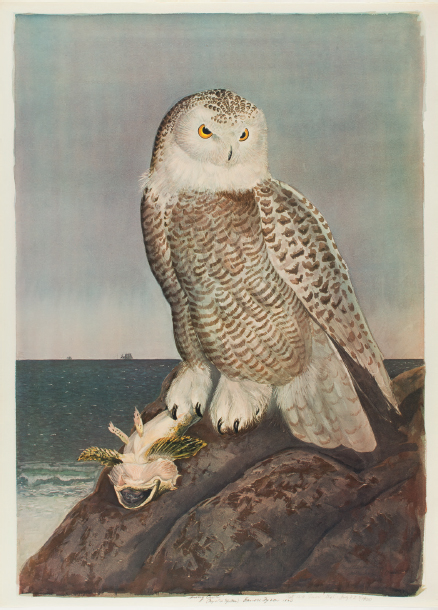

Since childhood, Tyson had spent his summers on Mt. Desert Island in Maine. After the death of Jim Bond’s mother (Tyson’s sister), Jim would join his aunt and uncle at Birchcroft, their mansion in Northeast Harbor, and Tyson’s well-appointed hunting lodge in nearby Southwest Harbor. Like his nephew, Tyson was fascinated by ornithology. In 1918, perhaps inspired by Audubon’s famous The Birds of North America, Tyson began painting watercolors of birds, both from nature and from stuffed specimens, choosing particularly those associated with his Maine environs, both native and migratory. Grandson Charles Tyson Jr. shared this family story:

Bond’s uncle Carroll Sargent Tyson Jr. was a noted artist and collector. Courtesy of David Contosta

“One summer afternoon at my grandparents’ house in Northeast Harbor, Grandmother and three of her friends were playing bridge on the covered porch when my grandfather barged through the bridge game in his usual disreputable painting garb. In a fit of pique, my grandmother berated him and said, ‘By the way, I’m sick and tired of those messy oils and the landscapes you insist on painting. Won’t you please do something else?’

Tyson’s acclaimed set of chromolithographs of the Birds of Maine included this portrait of a snowy owl. Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of Pauline Townsend Pease, 1979-130-1n. © Estate of Carroll Sargent Tyson

“The next day, she went out and bought him a set of the most expensive watercolor paints, paper, and brushes she could find, and presented them to him. Thereupon, my grandfather called Jim Bond, and the two of them cooked up the idea of an elephant folio of birds of Mt. Desert Island. Jim provided over a hundred species of birds, trapped and stuffed them, and he and my grandfather posed them in natural settings. My grandfather then made, I believe, 108 sketches, some of which were only partially finished and many were fully painted. They then selected twenty of the paintings they felt were the best. These were sent to an engraving and printing firm [Otto Hoelsch] in Milan, Italy, where plates and prints were made, eventually ending up in the portfolio. And all because of an altercation at a bridge game.”

The portfolio of twenty chromolithographs, The Birds of Mt. Desert Island, Acadia National Park, Maine, was published in a limited edition of 250 copies, after which the plates were destroyed. On Mt. Desert Island, the Wendell Gilley Museum in Southwest Harbor and the Northeast Harbor Library have complete framed sets of Carroll Tyson’s bird prints on display. Northeast Harbor summer resident T. Garrison Morfit (old-time TV personality Garry Moore) came across the portfolio in Bermuda, and he and his wife donated them to the library in Northeast Harbor. Summer resident Martha Stewart also has a complete framed set of the chromolithographs, which she describes as “extraordinary and beautiful.” Small wonder that Tyson is considered the John James Audubon of Maine, and that some of his Mt. Desert Island prints sell for thousands of dollars. Although one of Tyson’s paintings, Hall’s Quarry, is in the White House Collection, he is better known for a work that he owned—Vincent Van Gogh’s Fourteen Sunflowers, one of the seven versions of sunflower still lifes that the Dutch post-impressionist painted in 1888 and 1889. Tyson paid the princely sum of $45,000 for it on a trip to Europe in 1928—on the same day he also bought major paintings by Paul Cézanne, Édouard Manet, and Berthe Morisot.

In Martin Bailey’s The Sunflowers Are Mine, Tyson’s son-in-law, Louis Madeira IV (Bond’s cousin by marriage), recalled that Tyson hung the Van Gogh behind his chair in the dining room so he wouldn’t have to look at it while he ate. Madeira said that his father-in-law “thought the painting crude and untutored.” There is still speculation as to whether the Van Gogh was a tad too modern for Tyson’s tastes, or the story was a family joke. Many works from the Mr. and Mrs. Carroll S. Tyson Jr. Collection are on view in the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s Resnick Rotunda, including Sunflowers, Renoir’s The Large Bathers, and Monet’s The Japanese Footbridge and the Water Lily Pool, Giverny. Bond and Tyson also collaborated on the eighty-two-page Birds of Mt. Desert Island, Acadia National Park, Maine (see chapter 005).

A map of the West Indies at the turn of the twentieth century. Courtesy of the British Library