The Lord Speaks (38:1–41:34)

Then the LORD answered (38:1). Divine speech in Job 38 has been compared with the Egyptian name lists or catalogues of things (Onomastica).305 These start with heaven and the stars, deal with meteorological phenomena like rain and thunder, the earth and water, persons and their occupations, towns and buildings, land and products, and end with parts of animals. This tradition is also known from Mesopotamia, where there are lists of trees, domestic and wild animals, birds and fish, and food and drink;306 but the order in Job is closer to that of Egypt.

Approaching clouds in mountains of Lebanon

John Monson

Where were you? (38:4). Whereas the emphasis in Job 9 was on Job as part of creation (cf. the sidebar on “Creation and World Pictures” at 9:7), chapter 38 emphasizes that God is the Creator and Job was not present at time of creation. In the Mesopotamian poem to Erra, rhetorical questions are also used by the creator god Marduk.307

When I laid the earth’s foundation (38:4). Creation is described like the construction of a building, and the foundations and cornerstone are laid. The link between creation and building terminology is reflected in the ancient Near Eastern temple, which was seen as a reflection of the cosmos. The Egyptian temple, for example, had pillars in the form of plants, a roof decorated with stars representing heaven, the shrine that represented the primeval hill of creation, and a sacred lake called the “divine pool.”308

Measuring line (38:5). The earth’s dimensions are marked off by extending a measuring line (cf. comments on 26:10). Marduk measured and found the area for building his temple.309 In ancient Near Eastern art, deities are often depicted holding a measuring rod and line as symbols of authority, because they are builders of temples, palaces, and kingdoms.310

Morning stars sang together … angels shouted (38:7). The stars singing together at creation are here divine beings, who are used parallel with “sons of the gods” (NIV “angels”—cf. comment on 1:6), as in a Ugaritic text, where “sons of El/the gods” occurs parallel with “assembly of the stars.”311

Shut up the sea (38:8). The battle with and control of the sea312 as a symbol of chaos (see the sidebar on “The Cosmic Battle with Chaos” at 41:1) is typical of ancient Near Eastern and Old Testament cosmogonies (see also 7:12, 9:8, 13, 26:12; Ps. 65:7; 74:12ff.; Prov. 8:29; Isa. 51:10). In the Babylonian creation epic Enuma Elish (4:139–40) it is said that Marduk, after smashing Tiamat, assigns watchmen and orders them not to let her waters escape.313 The image of a baby is used in Job 38:8–11, as described by Habel as “born from a womb, wrapped in baby clothes, placed in a playpen, and told to stay in its place.”314

Morning dawn (38:12). Dawn (šaḥar)315 is personified as in Psalm 57:8 and 108:2, where it is woken up. In Ugaritic literature Shahar is a deity, the child of El, who acts with other deities such as the sun goddess.316 In 41:18 it refers to the eyes of the Leviathan.

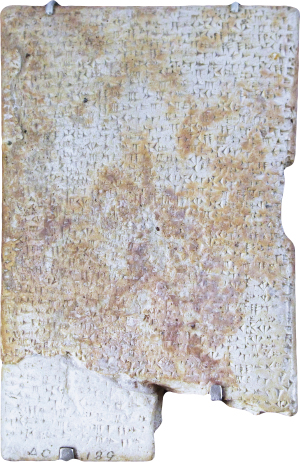

Ugaritic text: Birth of the Gracious Gods (Dawn and Dusk)

Rama/Wikimedia Commons, courtesy of the Louvre

The earth takes shape like clay under a seal (38:14–15). The image of a seal pressed on clay is used (see sidebar on “Seals and Sealing” at 14:17). In the same way as the image on the clay stands out, the earth takes shape in the growing light and the landscape becomes clearer. When the light appears, the wicked are denied light and the upraised arm is broken (v. 15); this is the time of the manifestation of God’s power, as was common in the ancient Near East.317

Gates of death (38:17). Death (māwet; see sidebar on “Death and Sheol” at 7:9) has gates like Sheol in 17:16; so does “the shadow of death” (ṣalmāwet—another word for death (cf. 24:17). Mesopotamian descriptions of the underworld tell about the seven gates, and there is even a divine gatekeeper.318

Who fathers the drops of dew? (38:28). Does the rain have a father? According to Ugaritic mythology, Baal had three daughters; the third one’s name was Tallay, meaning “dew,” or even better, “dewy.”319

Count the clouds … tip over the water jars of the heavens (38:37). An enamel tile (with color glaze) from the time of the Assyrian king Tukulti-Ninurta II (888 B.C.) shows a god (Ashur?) in a winged sundisk with drawn bow, with stylized rain and hail hanging in “bags” or water containers (RSV waterskins), as in Job, on the sides.320

The god Assur with drawn bow is surrounded by storm clouds filled with rain.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Clods of earth (38:38). Regions like Syria and Palestine, where there are no large rivers as in Egypt and Mesopotamia, are dependent on rain, without which the earth becomes dry and the clods of earth literally stick together. This idea is known from the myths of Ugarit, where when Baal is dead, the furrows of the fields are dried up.321

The wild donkey (39:5–8). The donkey/ass or onager can be differentiated from the horse because of the much shorter tail of the donkey, the shorter standing mane, and the typical larger ears.322 Here the donkey is not the dumb and lazy animal of the popular Western image but a symbol of the wild, for it cannot be tamed (v. 7; cf. Gen. 16:12; Isa. 32:14; Jer. 2:24; 14:6). Assyrian reliefs depict the hunting of such wild donkeys.323 People who break treaties are cursed to roam the desert like the wild ass, the desert symbolizing the periphery of civilization.324

The wild ox (39:9–12). This is a strong animal and difficult to tame (cf. Deut. 33:17; Ps. 92:10). In the Ugaritic texts the goddess Astarte hunts a bull, as did the Assyrian kings.325 Ox-hunting is also depicted on Assyrian reliefs, and a beautiful golden dish from Ugarit shows a king in his chariot hunting wild bulls.326

Gold plate from Ugarit depicts a hunting scene featuring wild bulls.

Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY, courtesy of the Louvre

The ostrich (39:13–18). The behavior of this running but not flying bird has always fascinated humans. It flaps its wings joyfully, and ancient people thought that the ostrich leaves its young after laying the eggs out of cruelty (cf. Lam. 4:3: “heartless like ostriches”). An ostrich egg is the size of twenty-four chicken eggs. The ostrich “laughs at horse and rider” (v. 18); this animal can outrun a horse, as already observed by Xenophon.327 Ostriches are depicted in Egyptian paintings, and the ostrich feather was the symbol of the goddess Maat. Tutankhamen is shown hunting ostriches, and an Assyrian hero pursues an ostrich.328

The horse (39:19–25). The horse was a war animal used for carrying a quiver, spear, and lance; it was familiar with the scent and cry of battle.329 Horses were used to pull chariots; riding came later. Assyrian reliefs show soldiers on horseback, but cavalry was applied on a large scale only by Alexander the Great, the Scythians, and the Parthians. In verse 20 the horse leaps like a locust, and in Joel 2:4 locusts are compared to running horses (cf. Rev. 9:7).

The hawk … the eagle (39:26–29). The last two animals described are birds of prey and large meat eaters. They have mighty wings (v. 26) extending two meters (more than six feet) in length. The young birds drink blood and, like vultures, eat corpses on the battlefield (cf. Matt. 24:28).

The thrust of the argument here is this: Does Job know how animals hunt and give birth and where their strength and movement come from? Only God as Lord-of-Animals can control them. But as Lord-of-Animals (related to šadday; see sidebar on “Almighty [šadday] and Other Divine Names” at 5:7), he does not destroy the animals but takes care of them330—even the lion is fed (38:39).

How can I reply to you? I put my hand over my mouth (40:4–5). Job refrains from answering such a powerful God by putting his hand on his mouth (cf. 21:5; 29:9). On a relief of the Persian king Darius I a Mede stands with his hand raised to his mouth as a gesture of respect in the presence of someone greater than he.331

An arm like God’s (40:9). The arm (like the hand) can indicate power and strength, as in 22:8 (lit., “man of arm”; NIV “powerful man”). In Exodus 6:6 God saves Israel with an outstretched arm. In a letter from Ugarit the hands of the gods are strong like death, and in Mari a god’s hand destroys cattle and men.332 The visual representation of deities brandishing weapons in a menacing way also reflects the power of the arm.333

Clothe yourself in honor and majesty (40:10). God challenges Job to dress himself in glory, which is ironic since only God can do this.334 God is clothed in splendor and majesty (Ps. 104:1; cf. Job 37:22). The Mesopotamian deities had power or glamor, called melammu; divine statues in the ancient Near East were clothed and deities are represented covered in light or stars.335 Marduk “wore” the auras of seven gods, and the monsters of Tiamat were again “clad” with glories.336

Behemoth (40:15). The last two animals encountered in Job are the enigmatic Behemoth (40:15–24) and the Leviathan (ch. 41). The million-dollar question that has been hotly debated and still intrigues readers and commentators alike is whether these are real and natural animals or metaphorical and symbolic animals, as the monsters and supernatural beings known from ancient Near Eastern mythology.

Related to this problem is whether they are two separate animals.337 Etymologically behēmôt is the plural of the Hebrew word for “creature” (i.e., “the beast par excellence”);338 liwyātān is related to “twist, curl, coil, wreath, the circular,” linking it to a serpent-like creature.339 In some cases the Leviathan occurs with the other sea monster, the tannin, in both the Old Testament and the Ugaritic texts.

There have been three interpretations for the Behemoth:340

• It is a natural animal, such as the hippo, elephant, or even a water buffalo.341

• There is no Behemoth, but it is merely a creation of the book of Job.342

• It is a mythological being.343

The description of these two animals is realistic and compares well with what is known of the hippopotamus (hippopotamus amphibius) and the crocodile (crocodilus niloticus); for this reason the translations “hippopotamus” (even “elephant”) for the Behemoth and “crocodile” for the Leviathan have been proposed (cf. notes to NIV). The NIV has a tail on Behemoth in 40:17 (but see “possibly trunk” in a text note, linking it with the elephant). Whereas the Behemoth is created by God (just as he created Job) and eats grass like an ox (40:15), the Leviathan spits fire (41:19), which surely makes it more than an ordinary animal. It also seems that the Behemoth is a being separate from the Leviathan, but more difficult to describe and identify, because it is disputed whether Behemoth occurs in other parts of the Bible. The Behemoth cannot be captured; only his Maker can approach him with his sword (40:19, 24).

Limbs like rods of iron (40:18). Egyptian texts refer to the god Seth, whose bones are like iron.344

Leviathan (41:1). Job 3:8 has already referred to the Leviathan as a cosmic monster. In the Hebrew Bible the Leviathan345 is a mythological sea monster defeated by Yahweh, as in Psalm 74:13–14:

It was you who split open the sea by your power;

you broke the heads of the monster in the waters.

It was you who crushed the heads of Leviathan

and gave him as food to the creatures of the desert.

In Amos 9:3 Leviathan is a snake at the bottom of the sea and in Psalm 104:26 a mere plaything of the Lord. But in the future there will again be battle with the Leviathan (Isa. 27:1—used parallel with the Tannin; see comment on Job 7:12). In Revelation 20:2–3 the ancient serpent, “who is the devil or Satan,” is thrown into the Abyss. The Leviathan in Job 41 may be a natural animal as he is described, and crocodile (also hippopotamus) hunting is well known from Egyptian paintings.346 Hippos also occurred on the Syrian coast and were hunted for their ivory, as is known from the art of Ugarit.347

However, because God is the only one that can control the Leviathan and Behemoth, as argued by Job, they can only be supernatural and should best be understood against the mythological background of the book of Job.348 The Leviathan embodies cosmic evil par excellence,349 and the combination of these two animals is also important. The hippopotamus and crocodile occur together as forces of chaos in Egyptian mythology, representing the god of confusion, Seth, who is defeated by the god Horus. This may indicate the mythological symbolism behind the texts.350

The seven-headed serpent Ltn (parallel with Yam, the chaotic ocean) is described in Ugaritic texts as being smitten by Baal:

When you smote Leviathan, the slippery serpent,

finish off the twisting serpent,

close-coiling-with-seven-heads.351

Egyptian art depicts the defeat of the god Seth by Horus, and Palestinian seal-amulets show a “master-of-crocodiles.”352

Sight of him is overpowering (41:9). Leviathan is so powerful that his very appearance makes one lie low or fall to the ground (TEV). The idea of fear is known from ancient Near Eastern mythology. In the Babylonian creation epic the gods were powerless against the might of Tiamat.353 In Ugarit when the messengers of the sea god Yam appeared, the gods lowered their heads onto their knees.354 In verse 25 when the Leviathan rises, “the mighty” (lit., “gods”) are afraid of him and retreat. This recalls cases from the ancient Near East where deities become afraid. In the Epic of Gilgamesh the deities are afraid when the flood comes.355

Firebrands … sparks of fire (41:19). The Leviathan spits fire. In the Gilgamesh Epic the monster Huwawa’s speech is fire.356

Slingstones (41:28). Stones could be projected in a slingshot (catapult) made from two cords with a pouch, as David used when he defeated Goliath (1 Sam. 17:49–50).357 This was not a primitive weapon and was still used by the Assyrian soldiers.

Slinger on orthostat from Tell Halaf

Caryn Reeder, courtesy of the British Museum

His undersides are jagged potsherds … like a threshing sledge (41:30). The potsherds are like the one used by Job in 2:8. The scales on the belly of the Leviathan leave marks like a threshing sledge—made of parallel boards with sharp stones—when it is dragged over the grain.358