Minorities from Other Regions: Chinese, Japanese, and French Canadians

During the century of immigration more than 90 percent of all immigrants were Europeans, and for many writers the words European and immigrant were all but interchangeable. Africans, so numerous in the formative years of the American colonies and the new nation, were kept out of the immigrant canon by definition; later, many authors did the same for Chinese, arguing that they were mere “sojourners” and thus not immigrants at all. These arguments have little attractiveness today; few scholars any longer deny the relevance of the Afro-American and Asian American experience for immigration history, and the once-overwhelming Eurocentricity of the field has weakened significantly. This chapter will examine the early experience of the first two Asian immigrant groups to come, Chinese and Japanese, along with the major discrete group from Canada, the French Canadians. Two other groups that might have been treated here, the Mexicans and the Filipinos, will be treated in later chapters because, although their immigration began before 1924, it continued thereafter and was not affected by the quota system—Mexicans because they came from the Western Hemisphere, Filipinos because they were considered American nationals. Also not treated here are English-speaking immigrants from Canada—what contemporary writers call “Anglophones.” The 1910 “mother tongue” census showed them more than twice as numerous as French Canadians—781,000 to 385,000—but, as we have seen, many were immigrants who had merely paused in Canada en route to the United States. Even more important, except for clusterings in towns and cities along the border, and later in the National Hockey League, there were no English-speaking Canadian communities until, in recent years, they began to develop in retirement areas of Florida. Even more than Charlotte Erickson’s English, these Canadians were invisible immigrants.

Chinese

If we do not count the ancestors of the Amerindians, who presumably crossed what is now the Bering Strait in prehistoric times, Chinese are the first immigrants from Asia. Although a few Chinese were present in Mexico in the seventeenth century, presumably having arrived on the annual Manila galleons, and others came to eastern U.S. ports in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, meaningful Chinese immigration to the United States begins roughly with the California gold rush of 1849. This identification of California—and America—with gold was so prevalent in the Chinese mind that the characters that came to stand for California in the Chinese language may also be read as “gold mountain.” When, in the next decade, another gold rush took Chinese, some of them veteran miners from California, to Australia, the characters for that country could be read as “new gold mountain.” It is beyond dispute that these Chinese and their immediate successors came, like so many Europeans, with the intention of sojourning and returning with a nest egg. Yet despite the similarity between European and Chinese sojourners, some scholars do not like to call these Chinese immigrants. What still bothers some scholars about nineteenth-century Chinese Americans is the false and essentially racist notion that they—and perhaps other Asians in that period—were, somehow, different from the other immigrants. It is a variant of the notion that while involuntary white persons brought to America were immigrants, involuntary black persons so brought were not. Such notions are simply no longer tenable. By the definition used in this book, which has gained growing acceptance among scholars in the field, it is now beyond dispute that Chinese were also immigrants. If any nineteenth-century migration qualified as a “change of residence involving the crossing of an international boundary,” the ocean journey from Canton or Hong Kong to San Francisco or other western ports certainly did. And it is the basic principle of this book that all immigrants to the New World in historic times have faced the same kinds of challenges and that the things that various immigrant groups have in common are as important as those that differentiate them.1

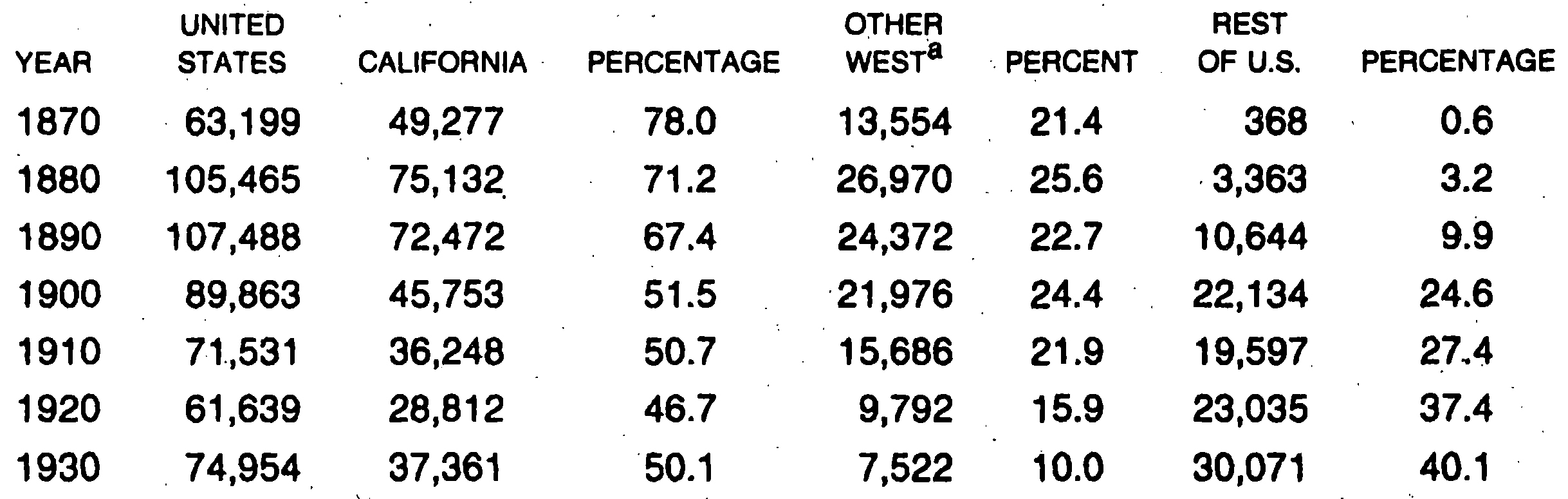

Between the beginnings of Chinese migration in 1848 and the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, perhaps three hundred thousand Chinese entered the United States. As was the case with European sojourners, there was much coming and going, so that, in all probability, the Chinese American population hit an intercensal peak of perhaps one hundred twenty-five thousand in the early 1880s. The census data, along with some indication of Chinese American distribution within the United States, are given in Table 9.1.

The Chinese had a migratory tradition long before any came to the United States, chiefly involving migration to Southeast Asia—the region the Chinese call Nanyang or South Seas. At the beginning of the nineteenth century Western entrepreneurs, with the help of Chinese middlemen, began importing unfree Chinese labor to various parts of the plantation world, largely as surrogates for African slaves. This “coolie trade,” as it came to be called, first brought Chinese to Trinidad in the Caribbean in 1808. The major New World destinations were Cuba and Peru, but few nations or colonies in the Caribbean and Latin America were untouched by it. It was a brutal and infamous system that in some ways was worse than slavery, in that some employers literally worked their coolies to death before their indentures ran out. This was particularly true in the guano islands off the coast of Peru, where that was the fate of the overwhelming majority.2

Table 9.1

Chinese in the Contiguous United States, 1870–1930

NOTE: Chinese in the U.S. Census was a racial definition and included both immigrants and their descendants.

aOther West here means the states or territories of Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, Nevada, Arizona, and New Mexico.

There is no evidence that any coolies were ever brought to the United States and, after the Civil War, coolie contracts would have been unenforceable at law. In the 1850s American consular officials in China explained to Washington the differences between immigrants and coolies. Based on this and other information, a report of the U.S. House of Representatives in 1860 distinguished between

the “Chinese coolie trade” . . . a servitude in no respect practically different from . . . the . . . African slave trade [and the flow to] California, a Chinese emigration which has been voluntary and profitable to the contracting parties. The discovery of gold in Australia divided the migration, which hastened to both places at the option of the immigrants themselves.3

The financing of emigration is a crucial problem. Well into the nineteenth century, as we have seen, Western Europeans indentured themselves to American employers in order to have their passage paid. Chinese, who in the early days of the migration expected to work for themselves in the “diggings,” borrowed from Chinese moneylenders. A British official in China in the early 1850s reported to London that some Chinese were borrowing seventy dollars (fifty dollars for the ticket and twenty dollars for expenses) and obligating themselves to pay back two hundred dollars. Some would have been able to draw on family resources, while others would utilize various kinds of rotating credit mechanisms then prevalent in South China. In any event, hundreds of thousands of Chinese got the money to come, and, since the credit ticket and other devices described above persisted into the twentieth century, we must assume that most of the money owed was paid, although we are not clear about the methods employed, kinds of security accepted, and so on. Clearly there were defaulters, just as some indentured servants ran away and just as today some people don’t pay their credit card bills, but shrewd lenders always try to build a certain margin for loss into their interest rates. If all the above seems relatively simple—and I think it does—it did not seem so to anti-Chinese American officials in the 1870s and 1880s or to generations of later historians who made the system—or rather a caricature of it—seem a sinister plot to undermine American standards of living and even the republic itself.

Emigration from China to America was, for almost a century, not so much Chinese as Cantonese emigration. Well over 90 percent of the immigrants of that era were not only from Canton in South China but from a very few counties centered on the Pearl River Delta there. And, although male migration was characteristic of many groups, among no large group of immigrants to nineteenth-century America was the sex ratio as skewed as it was among the Chinese. By the 1880s, according to the censuses of 1880 and 1890, Chinese males outnumbered females by more than twenty to one. (In Australia the imbalance was incredible: In Victoria in 1857 there were 25,421 Chinese males and just 3 females!)

Within the United States, as table 9.1 shows, Chinese were concentrated in the West in general and in California in particular, although the percentage in the rest of the United States grew steadily after 1870. Within California there was concentration as well. Initially centered in the mining districts of the Sierras and their foothills, Chinese soon made San Francisco, the port of entry for most of them, the dai fou, or big city, with more than a fifth of all Chinese Americans recorded as living there by the 1880 and 1890 censuses. These probably significantly understate the Chinese population, as many were migratory workers who lived in San Francisco when not on the road. Wherever they lived, Chinese Americans were increasingly urbanites, and big city urbanites at that. In 1880 just over one in five lived in large cities, those with more than one hundred thousand population. By 1910 almost half of Chinese Americans did, and by 1940, more than seven out of ten.

In those large cities they lived almost exclusively in ethnic enclaves known as Chinatowns. Unlike the enclaves of European immigrants, the populations of Chinatowns of any size were almost totally Chinese. “Little Italies,” by contrast, had much lower concentrations of Italians: In Chicago, for example, only a few blocks had a concentration of as high as 50 percent. Only the black neighborhoods of twentieth-century American cities have the kinds of concentration found in the big-city Chinatowns of the nineteenth century.

San Francisco’s Chinatown was the first and most important: It was replicated in large cities across the United States as far away as Boston and, even though today there are more Chinese in New York than in San Francisco, the latter retains its cultural primacy. One of the remarkable things about San Francisco’s Chinatown has been its geographical stability; in the 1850s an immigrant community was formed in the area centering on the intersection of Dupont and Stockton Streets, and for almost a century and a half of growth, earthquake, fire, and urban renewal it has remained in that neighborhood with only slight variation, mostly expansion. While Chinatowns have become tourist attractions, that is largely a twentieth century phenomenon, although some whites went to nineteenth-century Chinatowns for “thrills,” including prostitutes and opium. Chinatowns were primarily places where Chinese Americans lived, worked, shopped, and socialized. They were overcrowded slum areas, but as such were not too different from other immigrant enclaves except that the well-to-do urban Chinese lived there too. The classic pattern of ethnic succession, by which one group moved out of the slums while another group or groups moved in, did not work for “colored” immigrants. And despite the restrictiveness of the larger society that kept Chinese confined, as it were, within the enclave, there were for Chinese, as for other ethnic groups, positive aspects to life in an ethnic community. In San Francisco and the other urban Chinatowns there were shops, services, communal organizations, and entertainment—all provided by and for Chinese.

Economically the Chinese were at first largely occupied in mining; in California alone, about a fifth of Chinese workers were so engaged as late as 1880. Another fifth in that year were laborers; a seventh, in agriculture; another seventh were in manufacturing, mostly of shoes and clothing; yet another seventh were domestic servants, and a tenth were laundry workers. The thirty thousand Chinese workers outside of California in 1880 were concentrated in mining, common labor, and the service trades. In the 1860s as many as ten thousand Chinese workers were engaged in building the western leg of the Central Pacific Railroad. Most Chinese on the railroad payroll seem to have received thirty-five dollars a month. Since food costs were estimated at fifteen to eighteen dollars a month, and the railroad provided shelter, such as it was, a frugal workman could net close to twenty dollars a month. Not all Chinese were laborers. Sucheng Chan has shown that hundreds of Chinese owned or operated farms and that they played a vital entrepreneurial role in California agriculture, introducing new crops and pioneering distribution systems.4 As early as 1870, one Chinese farmer in Sacramento County produced a crop worth nine thousand five hundred dollars. Most Chinese, in agriculture or anywhere else, made much less. Most of those in manufacturing, for example, made a dollar a working day or less, but 1880 census data indicate that 8 percent of Chinese cigar workers in San Francisco made four hundred dollars a year or more, well above the sweatshop level. At the very top of the Chinese American economic pyramid were the merchants who became the power elite of the community. We know very little and are never likely to know much about them. Many came with some capital and presumably had ties with Canton mercantile houses. Merchants made money in a number of ways: by normal international trade and the importation of the exotic goods desired by the Chinese American community; many also had a “piece” of the credit ticket system and served as labor contractors. A merchant who provided labor to the Central Pacific or other employers of large numbers of Chinese often was able to make an additional profit by selling rice and other foodstuffs and opium to the employer or to the laborers themselves. I suspect, but cannot demonstrate, that there were proportionately more individuals of real affluence within the Chinese American community in the late nineteenth century than there were in any other contemporary immigrant group.

The communal life of Chinese America was distinctly different from that of most other immigrant groups in that churches were not major organizations. This was because the focus of most Chinese religion was the family. (There were, to be sure, a small but growing number of Chinese who came here as Christians or who were converted after they arrived.) For most immigrant Chinese the family association or clan was the most important organization. These associations united all those who had a common last name—all the Lees or Lis, for example—and thus presumably a common ancestor. In small Chinese villages the clans tended to be village or intervillage associations based on real as opposed to theoretical kinship, but by migrating—either to a large Chinese city or to America—Chinese broke the original village relationship. All Chinese in America were also—in theory—members of a district association based on the regions of Kwangtung Province from which almost all of them came. Without tempting to trace the evolution of these groups, suffice it to say that they were soon governed by a new institution made in America, a still-existing umbrella group called the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, popularly known as the “Chinese Six Companies.” These were clearly landsmanschaftn type of organizations, but with Chinese American variations. They were run by the Chinese American power elite, the merchants, and they became the spokesmen for the entire Chinese American community and its intermediary to the white establishment. When, for example, a congressional investigating committee came to San Francisco in 1876 to look into Chinese immigration, it was the Six Companies that hired Caucasian attorneys to conduct a “defense” of the community. And the word benevolent in its title was not mere window dressing: In an age when government assumed few of the obligations of what is now called the welfare state, the Six Companies, like other associations all over ethnic America, assumed them; it helped new arrivals find jobs and housing, fed the hungry, nursed the sick, buried the dead, and—a uniquely Chinese function—arranged for their bones eventually to be sent back to China for burial in the appropriate ancestral cemetery.

And, as is the case with most benevolent associations as well as with the contemporary welfare state, the Six Companies served to exercise some forms of what sociologists call “social control”: That is, they encouraged their members to conform to certain community norms, with the implied loss of benefits or protection for those who deviated from them. The merchant-run association naturally encouraged Chinese to pay their debts and to pay their dues to the association, which helped defray the costs of the welfare system. It tried to see that every returning Chinese was checked at the dock to make sure that he was debt free and had paid his “tax”: it was not a fail-safe system, but, since steamship companies often cooperated, it was at least partially effective. Since most Chinese planned to return to China, this presumed check on returnees was a real threat to the sojourner’s security. The association also settled disputes between individuals and groups within the community and otherwise assumed roles that, in the larger community, were assumed by government. This led to the charge, not without truth, that the Six Companies were an “invisible government.” The adjective invisible was plain silly: Its headquarters was one of the most prominent buildings in Chinatown. But anti-Chinese Caucasians gave the word a sinister spin that was inappropriate. Actually, they should have welcomed the association’s role as it insured more order in the community than would have existed without it.

In addition to the establishment and public family associations and the Six Companies, there were the antiestablishment and private organizations known as tongs. Tongs became notorious as criminal organizations, with links to Chinese American crime—prostitution, gambling, and drugs. They used thugs known as “hatchet men,” who soon became Americanized and used guns. But the tongs, about which we have very little reliable evidence, had other functions as well. The tongs parallel, and may have had direct relations with, the Triad Society, an anti-Manchu, antiforeign secret society that flourished in South China. Like so many revolutionary organizations elsewhere, it also had a criminal side. While the Chinese American tongs seem to have had some political connections—funds for Sun Yat-sen and other anti-Manchu leaders were probably funneled through them—they were primarily criminal.

In all these matters the structure of the Chinese American community was, in essence, a variation on the American ethnic pattern, showing differences in degree but not in kind. What makes the Chinese experience unique in American ethnic history was not what they did but what was done to them. What was done to them includes both discrimination and extralegal violence and a whole series of discriminatory ordinances and statutes from the municipal to the federal level. The details of this discrimination will be treated in the next chapter, but two specific federal statutes must be briefly noted here: the Naturalization Act of 1870 and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. The first, which limited naturalization to “white persons and persons of African descent,” meant that Chinese immigrants were in a separate class: They were aliens ineligible for citizenship and would remain so until 1943. (When other Asian groups came, they too were in this category, some until 1952.) The second, which was the first significant inhibition on free immigration in American history, made the Chinese, for a time, the only ethnic group in the world that could not freely immigrate to the United States.

The Exclusion Act, in effect, froze the Chinese community in its 1882 configuration, a configuration that included, as has been noted, a highly imbalanced sex ratio, which was characteristic of most American immigrant communities in the later nineteenth century. As Table 9.1 shows, the Chinese population of the United States went into a long decline that ended only in the 1920s. The act ossified the gender structure of the Chinese community for more than half a century, making it an essentially bachelor society and one in which old men always outnumbered young men. The resourceful immigrant community devised ways to replenish itself, however. Not only was there a significant but incalculable amount of illegal border crossing, but Chinese also created the elaborate system of immigration fraud the community called “paper sons,” exploiting the combination of an anomaly in American law and a natural disaster. Although Chinese could not become naturalized citizens, the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which had been passed in 1868 to protect the rights of newly freed blacks, made “all persons born . . . in the United States” citizens. Chinese born here were thus citizens, although there were not very many of them. Such citizens could travel to China, marry, and have children. These children—but not their mothers—could come to the United States because they were children of an American citizen. The great San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906 destroyed birth records. This enabled many Chinese to make fraudulent but successful claims of American citizenship. Some of these citizens traveled to China and brought back their own children, almost always sons. Others, however, stayed there and sold the “slots” their trips created to other Chinese who then brought over their own relatives. Victor and Brett de Barry Nee, in their brilliant book Longtime Californ’, interviewed some paper sons in the 1960s as part of their oral history of San Francisco’s Chinatown. One told them:

In the beginning my father came in as a laborer. But the 1906 earthquake came along and destroyed all those immigration things. So that was a big chance for a lot of Chinese. They forged themselves certificates saying they were born in this country, and when the time came they could go back to China and bring back four or five sons just like that! They might make a little money off it, not much, but the main thing was to bring a son or a nephew or a cousin in.5

How the Chinese American community would have evolved if there had been no Exclusion Act is impossible to say, but there is reason to believe that it would have come to resemble other immigrant groups, in that those men who decided to stay and had some degree of success would have sent for a wife or gone back to China to get married. And, although we speak of Chinese America before World War II as essentially a bachelor society, large numbers of the “bachelors” were married men: Their wives, however, lived in China. One of the arguments for the Exclusion Act, an argument that would be used later against other Asian immigrant groups and against many European groups as well, was that they were “unassimilable” and/or did not wish to assimilate to American life and American standards. Since family formation was a major vehicle of acculturation and Americanization, it is obvious that American law helped to retard this process. But some nineteenth-century Chinese immigrants did both acculturate and assimilate into American life. Two examples follow, one from the lower social levels of the immigrant generation, the other from the very highest.

The first, Sing On, was born about 1860 somewhere in China. In 1873 the teenager somehow showed up in Montana Territory, where he supported himself and attended school. He then moved to Chouteau and then to Teton County, where he farmed 480 acres. In 1879, at his request, the Montana Territorial Assembly passed an act changing his name to George Taylor, which he later embellished to George Washington Taylor. In 1890 he married Lena Bloom, also an immigrant, from Sweden, and they had seven children, four boys and three girls. In 1917, when the Taylor family appears fleetingly in the national historical record, their eldest son, Albert Henry Taylor, was serving with American troops on the Mexican border, part of General Pershing’s “punitive expedition” seeking Pancho Villa. The Taylor family history up to that time may be found in a formal petition of the Montana legislature asking that Congress grant citizenship to the elder Taylor, described as an “honorable . . . and upright man . . . opposed to anarchy and polygamy.” Congress did not grant the petition, and I know nothing more of the Taylor saga.

The second was the most famous Chinese to live in nineteenth-century America and the first to publish an autobiography in English, which I had reprinted some years ago. Yung Wing (1828–1912) was the first Chinese to graduate from an American college and thus the forerunner of tens of thousands of immigrant students. Born near Macao, he came under the tutelage of Christian missionaries and attended one of their schools in Hong Kong. He arrived in America in 1847, entered Yale College in 1850, and received a bachelor’s degree four years later. In the meantime he had joined a Christian church and, in 1852, became a naturalized American citizen. (This was contrary to the law, which then restricted naturalization to “free white persons,” but naturalization procedures were chaotic until reform took place in Theodore Roosevelt’s administration.) After graduation he was involved in large business transactions on both sides of the Pacific and at one time had the Gatling gun concession for all of China. For eighteen years, 1863–81, he performed missions for the Chinese government abroad, including investigating the coolie trade in Latin America. His most celebrated task was serving as codirector of the Chinese Educational Mission of 1872–81, which brought 120 men to Connecticut for a Western education, some of whom were able to follow in his footsteps at Yale. For the last six years of that period he was also assistant minister of China to the United States. In 1875 he married a native-born American citizen, Mary L. Kellogg, in a Christian ceremony. After 1881 Yung was out of favor with the Chinese government, which had closed down the educational mission, but remained active in transpacific commercial activity. In 1898, again in China, he applied to the American minister for assistance and, as a result, had his citizenship cancelled by the American secretary of state, John Sherman, who admitted that, since Yung had been a citizen for twenty-three years, it “would on its face seem unjust and without warrant” to cancel his citizenship, but that is exactly what he ordered done. This meant that Yung could not legally return to the United States. Nevertheless he did so in 1902—we don’t know how—and lived in Connecticut until his death.6

George Washington Taylor and Yung Wing were clearly exceptional persons, but so are all the nineteenth century immigrants we know anything about: Most immigrants are simply represented statistically in what Abraham Lincoln called the short and simple annals of the poor. Some native-born Chinese Americans also demonstrated that the American environment had had its way with them. In 1895, for example, a group of Californians formed an American-style rather than a Chinese-style benevolent association and called it Native Sons of the Golden State, a title deliberately mimetic of an established and virulently anti-Chinese organization, the Native Sons of the Golden West. The desire to be “American” can be seen in this clause from its initial constitution:

It is imperative that no members shall have sectional, clannish, Tong or party prejudices against each other or to use such influences to oppress fellow members. Whoever violates this provision shall be expelled.7

Immigrant women, too, show the influence of America. One Chinese woman, the wife of a merchant, remembered, years later:

When I came to America as a bride, I never knew I would be coming to a prison. Until the [1911] Revolution, I was allowed out of the house but once a year. That was during New Year’s when families exchanged . . . calls and visits. . . . After the Revolution . . . I heard that women there were free to go out. When the father of my children cut his queue [Chinese men were required to wear a queue by the Manchu dynasty] he adopted new habits; I discarded my Chinese clothes and began to wear American clothes. By that time my children were going to American schools, could speak English, and they helped me buy what I needed. Gradually the other women followed my example. We began to go out more frequently and since then I go out all the time.8

While other Chinese were and remained classic sojourners—working and scrimping only to be able to improve their lot in China, as did countless thousands of European immigrants, such as the Hungarian couple Lajos and Hermina P., many thousands of Chinese remained in America either by choice or by necessity. All of them, no matter how deeply embedded they were in Chinese enclaves, which some of them hardly ever left, were affected by the American environment, and many soon began to relate to American as well as Chinese cultural patterns. That more of them did not do so was at least as much the fault of the American society that rejected them as it was due to the deep hold that Chinese culture had on most of its members, even the emigrants. American society seemed so closed to Chinese that even ardent Americanizers among its first generation leadership, such as Ng Poon Chew (1866–1931), often despaired of an American future for the American-born second generation. Toward the end of his life this pioneer Chinese American editor could write that perhaps “our American-born Chinese will have to look to China for their life work” as there were simply no appropriate jobs for educated Asians in white America between the world wars.9

Japanese

Although Chinese and Japanese were linked in the American mind as Oriental immigrants, and each group eventually suffered exclusion on the grounds of its race, their history and immigration experience are at least as different from one another as those of Germans and Poles. Unlike China, Japan had no long emigrant tradition; by the time Japanese began to immigrate to the United States in significant numbers in the 1890s, Japan was a nascent imperial power with aspirations to the leadership of East Asia, while China was a victim of imperialism, some of it Japanese.

The first group of Japanese to come were political refugees in 1869, who founded a short-lived agricultural colony near Sacramento. In the same year about 150 Japanese were brought to Hawaii to work on sugar plantations, where large numbers of Chinese were already employed. The Japanese immigration to Hawaii was renewed in 1884, and about thirty thousand Japanese were brought there under contract to plantation owners. After 1898, when the United States annexed Hawaii, many of these workers emigrated to the American West Coast. In the meantime, beginning in the 1890s, small but significant numbers of Japanese arrived directly from Japan at North American Pacific ports such as San Francisco, Seattle, and Vancouver. In the years prior to 1924 fewer than three hundred thousand Japanese came to the continental United States; many returned and many others made more than one trip. Table 9.2 gives the census data, along with an indication of Japanese American geographical distribution. As that table shows, the concentration of Japanese on the Pacific Coast and in California increased with each census, and would continue to do so until the United States government forcibly removed them to interior concentration camps in 1942. The Chinese, as we have seen, were more dispersed with each census.10

Table 9.2

Japanese in the Contiguous United States, 1900–1930

NOTE: Japanese in the U.S. census was a “racial” definition, and included both immigrants and their descendants.

aPacific Coast here means California, Oregon, and Washington.

But the most important differences in the demography of the two communities do not appear in those tables: They were gender and age distribution, which are illustrated in charts 9.1 and 9.2.

These charts show that, as of 1920, the Chinese American community was not only still predominantly male (87.4 percent) half a century after significant numbers were recorded in the census, but also that it was still a bachelor society with the two largest cohorts being men in their fifties. The small female population (12.6 percent), conversely, was relatively young, with the two largest cohorts being girls under ten years of age. In the same census, by contrast, the Japanese American community had a more “normal” look, just two decades after significant numbers were recorded in the census, although it still bore some of the hallmarks of the immigrant bachelor society. Males still predominated, but they were “only” 65.5 percent of the population, and the largest male cohort was in its late thirties. Females were just over a third of the population, and almost a quarter of them were under five years of age, as were almost a seventh of the males. If we look at that youngest cohort comparatively, we see that 17.1 percent of all Japanese Americans were under five years of age, as compared to 4.7 percent of all Chinese Americans. This last set of data prefigured what would happen demographically in both communities during the next two decades, when no significant immigration occurred: The Japanese would become younger and more native born; the Chinese would change much more slowly. As of 1940 more than two-thirds of the 125,000 Japanese Americans were native-born citizens, as against a bare majority of the 75,000 Chinese Americans. Furthermore significant numbers of that majority of Chinese Americans—those with forged birth certificates and the “paper sons” those certificates brought in—were persons acculturated in China rather than America. How and why these differences came about, largely as a result of American law, is a fascinating story.

Chart 9.1

Age and Sex Distribution of Chinese Americans, 1920

Source: United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, 1920 Census of Population I, tables 4, 5, and 10, pp. 157, 166–67.

Chart 9.2

Age and Sex Distribution of Japanese Americans, 1920

Source: United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, 1920 Census of Population I, tables 4, 5, and 10, pp. 157, 166–67.

The early years of Japanese immigration to the American mainland were marked by a heavily male immigration. In the 1880s and 1890s many and perhaps a majority of Japanese worked at urban occupations but, by 1900 their economic focus was in agriculture where it remained. In the last decades of the century of immigration they were the only sizable ethnic group to have such a concentration. Initially most Japanese worked as agricultural laborers, in part replacing aging Chinese who were becoming more urban, in part meeting some of the ever-increasing demands of California agriculture for cheap labor. Soon Japanese began to acquire farmland. Large numbers of Japanese immigrants were from farm families who were being squeezed by the industrialization of Japan, just as German and other European peasants had been squeezed in the earlier nineteenth century. And, to be sure, the scarcity of arable land was even more pronounced in Japan than it had been in Europe. By 1904 Japanese were already farming more than fifty thousand acres in California alone; by 1909 it was more than one hundred fifty thousand acres and by 1919 more than four hundred fifty thousand acres. This latter figure represented only about 1 percent of all California agricultural land, but on it Japanese farmers, utilizing a labor-intensive style of agriculture, grossed about sixty-seven million dollars in that year, about a tenth of the total value of all California produce. While most were small family-style operations, one spectacular California entrepreneur, George Shima (1863–1926), ran a huge operation of the type that journalist-historian Carey McWilliams would later style “factories in the field.” Born Kinji Ushijima in Fukuoka Prefecture, he came to the United States in 1889 with some capital he later described as less than one thousand dollars. Within twenty years he was the most famous Japanese in America, described in the press as the “Potato King,” from the crop he introduced in California on the drowned islands of the Sacramento Delta. In 1913 Shima and his associates controlled twenty-eight thousand acres and through marketing agreements with other Japanese farmers sold the produce grown on other thousands of acres. His work force in that year was more than five hundred persons, including agronomists, boat captains, engineers, and common labor and its supervisors. When Shima died his pallbearers included David Starr Jordan, the chancellor of Stanford University and James Rolph, Jr., the mayor of San Francisco. Shima’s success, and the early successes of most of his compatriots, came in Northern California, but soon Los Angeles became the quintessential city of Japanese America. By 1930 more than 35,000 Japanese lived there—more than a quarter of the nation’s Japanese population.

John Modell, the historian of Japanese Los Angeles, has described the unique ethnic economy that developed there and demonstrated that “agriculture was the foundation of much of the enterprise and prosperity” of that ethnic community, and this holds true for Japanese communities all up and down the Pacific Coast and as far east as Colorado, and even to a small community in Florida. In Los Angeles, Japanese dominated the production of fresh green vegetables and some fruit crops, particularly strawberries. They not only grew the produce but organized the wholesale marketing of it for local consumption, while white wholesalers controlled most of the produce shipped elsewhere for sale. In the City Market of Los Angeles a few of the large Japanese-owned operations grossed a million dollars or more, but most were small stall operations. By the late 1930s there were radio programs in Japanese that reported market prices. Although initially almost all labor on Japanese agricultural enterprises in Los Angeles was Japanese, by the 1930s there were more Mexicans and Mexican Americans in the local agricultural labor force than there were Japanese, and Japanese growers’ attitudes toward labor were similar to those of the entrepreneurial classes everywhere.11

Obviously, by American standards, Japanese immigrants and their children were highly successful. They made a significant contribution to the growth of California in particular and much of the West in general. But Japanese, whatever their other virtues, were not white people, and Californians and other Westerners lobbied vigorously and well-nigh unanimously for their exclusion beginning in the early years of the twentieth century. Although the details of the anti-Japanese movement will be treated in the next chapter, it is important to note here that if Japan had been a weak nation such as China, it is clear that something very much like the Chinese Exclusion Act would have been directed against Japanese in about 1906 or 1907. But Japan was not weak and few Americans were more aware of her military might than President Theodore Roosevelt, who raged, in a private letter, about the “foolish offensiveness” of the “idiots” of the California legislature, and who publicly pointed out that the “mob of a single city [he had the anti-Japanese mobs of San Francisco in mind] may at any time perform acts of lawless violence which would plunge us into war.” Roosevelt successfully headed off anti-Japanese federal legislation and negotiated an agreement with Japan—the so-called Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907–8—which ended the immigration of Japanese laborers to the United States by having the Japanese government refuse to issue passports to such persons. The Gentlemen’s Agreement did provide for family unification through a provision that allowed passports to be issued to “laborers who have already been in America and to the parents, wives, and children of laborers resident there.”

The Gentlemen’s Agreement forced Japanese immigration into an essentially female mode: Between its adoption and its abrogation by Congress in 1924, some twenty thousand adult Japanese women migrated to the United States. A few were wives whom Japanese immigrants had left at home, but most were newly married women. Some married men who went back to Japan for the ceremony but most were married in Japan by proxy to men they saw for the first time only after they landed in America. Often there would be a second ceremony in the United States. This custom, called “picture bride marriage,” was consonant with Japanese tradition and was not unknown among European migrants to the United States, but it seemed to anti-Japanese Californians as a plot to flood the Golden State with Japanese. But, because of it, the Japanese American gender ratio was much less distorted than it was among Chinese Americans or among certain other heavily male ethnic groups.

The Japanese American community thus developed along sharply differentiated generational lines. The immigrant generation, the Issei (literally first generation) came in two echelons: most males between the 1890s and 1908; most females between 1918 and 1924. Their children, the Nisei (literally, second generation) were born into families in which the father was usually a decade older than the mother. When, in 1942, the government incarcerated the West Coast Japanese and got a detailed count, in the typical Japanese family children had been born in the years 1918–22, and the surviving male parents were in their late fifties, the females in their late forties.

Economically the population was heavily engaged in agriculture and other outdoor activities. In 1940 slightly more than half of all employed Japanese males and a third of working Japanese women worked in agriculture, forestry, and fishing. In the Pacific Coast states where most of them lived those sectors employed only one worker in eight. Unlike Chinese Americans, who by 1940 were more than 90 percent urbanized, just a little over half Japanese Americans were urbanized (54.9 percent), which was slightly below the national figure. Most of the rest of Japanese Americans were in wholesale and retail trade (about a quarter) and personal service (more than a sixth).

The cultural organizations of the immigrant generation were unique in that the most important of them were sponsored by the Japanese government. As part of its responsibilities under the Gentlemen’s Agreement the Japanese government caused the Japanese Association of America to be founded, with headquarters in San Francisco, the cultural capital of both Japanese and Chinese America, with local and regional associations developing wherever significant numbers of Japanese settled. Tokyo delegated to this organization and its branches the issuing of documents necessary for immigrants who had continuing relations with Japan. The most important of these were the documents needed to get a passport for an existing wife or bride. It may seem that the Japanese government took what appears to be an inordinate interest in the lives of its citizens in America until one realizes two things. First of all, like Chinese and other Asians, they were aliens ineligible for citizenship in the United States, so that if Japan didn’t look out for them, no government would or could. Second—and even more important from the point of view of Tokyo, which was not much given to worrying about the welfare of its peasantry—was the fact that it was convinced that its prestige as a nation was, in part, dependent on the respect given to Japanese abroad. The nightmare, for Japanese diplomats and officials from the 1890s on, was that there might eventually be a “Japanese Exclusion Act,” along the lines of the Chinese Exclusion Act. When Japanese exclusion finally came, in a different form, in 1924, there were riots and even a suicide or two as part of Tokyo’s deep resentment. A few Chinese diplomats, conversely, made the odd protest, but it was never a cardinal point of Chinese diplomacy. The redoubtable Wu Ting-fang (1842–1922), the Chinese minister in Washington around the turn of the century, for example, complained of the constant abuse Chinese Americans received in the press: “Why can’t you be fair? Would you talk like that if mine was not a weak nation? Would you say it if Chinese had votes?”12

The Japanese government, through the Japanese associations, encouraged Japanese to acculturate: to adopt Western dress and, above all, to educate their children. One of the first of the diplomatic crises over the immigration issue between the United States and Japan was the so-called San Francisco School Board Affair. In 1906 the local authorities tried to force the Japanese students in San Francisco—then fewer than a hundred—to attend the already established segregated school for Chinese, which was quite proper under California law and the American Constitution as then interpreted. Only intervention by President Theodore Roosevelt got the San Francisco authorities to rescind their order. This stress on acculturation and education from the top at a time when most contemporary immigrant groups were indifferent—or worse—to anything more than a rudimentary education for most of their children, was an important influence within the community and was surely one of the factors that led, within a generation, to native-born Japanese having more years of education than the average American.

Religious organization among the Japanese Americans was diverse. A majority of the first generation continued to practice Buddhism (the church in America, and in other countries where there were overseas Japanese, was subsidized by Japan), but a large minority were or became Christians. Japanese attitudes toward religion tended to be more plastic than those of many immigrant groups whose loyalty to the religion of their fathers has been pronounced. Not atypical were these remarks of an Issei resident of Seattle:

I told my children that it didn’t matter whether they went to a Christian church or a Buddhist church but that they should go to some kind of church. Since their friends were going to the Methodist Church, they went there, but after I joined the Congregational Church, I transferred them to the latter.13

Eventually, the majority of the second generation became Protestant Christians; in Brazil, a majority of its Nisei became Roman Catholics; and in Utah a significant percentage of Japanese living there have become Mormons.

However successful the acculturational strategies pursued by most Japanese Americans eventually were, as far as Tokyo was concerned they were a failure. In the final analysis, by 1924, Chinese, whose acculturation was slow, and Japanese, whose acculturation was quite rapid, were dumped into the same ignominious category: They were not only “aliens ineligible for citizenship” but also, as such, inadmissible to the United States as immigrants. The two-decade delay in Japanese exclusion was in no way due to any qualities demonstrated by the Japanese American people but rather to the respect inspired by Japan’s military power. A contemporary analogy can be seen in the way that South Africa treats Asians: Most—and all regular residents there—are nonwhites: Japanese businessmen, however, are “honorary” white people.

French Canadians

In 1881 Carroll D. Wright (1846–1909), then Massachusetts commissioner for labor statistics and a major figure in American reform movements, launched a diatribe at one immigrant group:

The Canadian French are the Chinese of the Eastern States. They care nothing for our institutions, civil, political, or educational. They do not come to make a home among us, to dwell with us as citizens, and so become a part of us; but their purpose is merely to sojourn a few years as aliens, touching us only at a single point, that of work, and, when they have gathered out of us what will satisfy their ends, to get them from whence they came, and bestow it there. They are a horde of industrial invaders, not a stream of stable settlers. Voting, with all that implies, they care nothing about. Rarely does one of them become naturalized. They will not send their children to school if they can help it, but endeavor to crowd them into the mills at the earliest possible age.14

The comparison with Chinese seemed particularly ominous to French Canadian leaders—Congress was in the process of enacting Chinese exclusion—and, some months later, a delegation of editors, priests, and other community leaders met with Wright in an attempt to show him that their people were not as he had said. To his credit, when confronted with evidence, Wright withdrew some of his remarks, or at least tempered them. (Not surprisingly, no one attempted to speak up for the Chinese: Rather the thrust was that the French Canadians were not at all like the Chinese.)

What was it that caused an intelligent man like Wright to link the French Canadians and the Chinese, two groups that in most characteristics were quite dissimilar? To answer that question it is necessary to examine the history of French Canadian migration to the United States, chiefly to New England. It was, like most migrations to the United States economically motivated, and it was unique in just one respect: The French Canadians are the only ethnic group whose migration was chiefly accomplished by rail.

The French-speaking population of Quebec, which numbered only about sixty thousand as late as 1763, had multiplied by 1871 to more than a million persons. This growth was entirely due to natural increase: There was no significant French-speaking immigration to Quebec, and there had been steady outmigration—to other parts of Canada and to the United States—from the time of conquest. Although Quebec is a huge province, nearly six hundred thousand square miles, more than twice the size of Texas or France, the combination of hardscrabble soil and a short growing season made agriculture difficult. The same factors that caused millions of Norwegians and Swedes to migrate to the United States and some eight hundred thousand New Englanders to migrate to western farmlands in the thirty years after 1790 impelled hundreds of thousands of Quebecois to come to the United States between the end of the Civil War and the turn of the century. It has been pointed out that they did not so much displace native New Englanders as replace them. While a few went from Quebec agriculture to New England agriculture, and thus shifted from one marginal farming area to another, most went into the textile mills and other factories that were the heart of New England’s economy. Just how many French Canadians came is all but impossible to determine, as enumeration at the land boundaries was at best erratic and the ebb and flow of individuals and families back and forth across the border only compounds the difficulty.15

The census data can give us some approximations of the numbers involved. Table 9.3 shows foreign-born and foreign-stock French Canadians as reported in the census between 1890 and 1920.

We can get an excellent notion of the attractions and realities of the New England mill towns for Quebecois in the 1870s from the first French-Canadian-American novel, Jeanne la Fileuse (Jeanne the Mill Girl) published in 1878 by an immigrant journalist, Honoré Beaugrand (1849–1906). Essentially what we would call today a docudrama, it is not great literature but is very useful for the student of history who wants to get a feel for how some contemporaries viewed industrial conditions. Jeanne, a sixteen-year-old orphan and her adopted family, the Dupuis, leave Montreal at four in the afternoon and arrive at Fall River, Massachusetts by train at two the following afternoon. Their tickets cost ten dollars each. They have to change trains twice, at Boston and at Lowell, but the railroad has provided bilingual personnel to help immigrants, and it ships and delivers their baggage as well. One member of the family, a seventeen-year-old son, has already been working in Fall River for a year, and has arranged for jobs for the whole family and a flat in a company tenement. The family arrives with thirty dollars, with which they purchase furniture and pots and pans. Beaugrand provides a capsule history of French Canadians in Fall River; they had been coming there only since 1868 but already number some six thousand persons, about an eighth of the population. There is already an established immigrant community and a newspaper, L’Echo du Canada, which the elder Dupuis reads, and French Canadian tradesmen. Since the Dupuis are in company housing, their rent is deducted from their wages. Their assured jobs mean they can get instant credit from the butcher, the baker, and the grocer until payday at the end of every month.

Table 9.3

French Canadians in the United States, 1890–1920

YEAR |

FOREIGN BORN |

FOREIGN STOCK |

TOTAL |

1890 |

302,496 |

224,483 |

526,934 |

1900 |

394,461 |

435,874 |

830,335 |

1910 |

385,083 |

547,155 |

932,238 |

1920 |

302,675 |

545,643 |

848,309 |

The father and the older children, including Jeanne, begin work in the mills. The three youngest children, aged eight, ten, and twelve, must, under Massachusetts law, attend school a minimum of twenty weeks a year, but, as soon as that minimum has been met, they too go to work in the mills. Everyone arrives at the mill at 6:30 A.M. When the mills are running at capacity a sixty-hour week is the rule. Mill workers were paid about $1.22 a day; children, depending on age and ability, get from twenty-eight cents to a dollar a day. By the third monthly payday—even before the three youngest children are able to work—the Dupuis family is beginning to put money in the bank, money they believe will buy them a farm in Quebec.

In other hands the Dupuis saga could have been a savage expose of the conditions of exploitive capitalism, but to Beaugrand the Dupuis are an American success story. To be sure, he admits that the work is not only drudgery but also that the conditions are somewhat like slavery, with the workers suffering from domination by foreigners, regimentation, and strict supervision. Beaugrand, however, looks at the positive side, as most French Canadian mill workers seem to have done at first as they fiercely resisted unionization. He sums up his treatise on conditions by insisting: “One is very unhappy the first weeks but when payday arrives, this unhappiness generally changes into satisfaction at the prospect of receiving regular wages, which is only natural.”

Beaugrand shows that the immigrants lived, worked, and socialized almost exclusively among their own kind. They attend a Catholic church, Saint Anne’s, with a Quebecois priest; the father not only reads a French-language newspaper but belongs to a French Canadian sodality, the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste, while the already established eldest son is a member of the Cercle Montcalm, a local cultural organization. The novel, originally serialized in a French Canadian newspaper, was read and apparently approbated by the very population it describes.

An essentially family migration, like that of the Dupuis, moved hundreds of thousands of French Canadians from Quebec to New England between the 1860s and the 1920s and, in the process, helped to change the face of New England. Arriving between the onset of the Irish and the coming of Southern and Eastern Europeans, the French Canadians experienced constant cultural reinforcement, both from continued migration and remigration and from being able to visit their homeland almost at will. Thus their acculturation has, in some respects, been slower than that of other groups.

The French of New England’s French-Canadian-American second and subsequent generations has persisted much more significantly, for example, than the Italian of New England’s Italian Americans. As late as 1970 more than half of those nearly 2.6 million Americans who reported French as a mother tongue were described by the census as “native born of native parentage”; in the same census fewer than 15 percent of those reporting Italian as a mother tongue were so described. In the same census nearly a million New Englanders, about a tenth of the population, reported French as a mother tongue. Part of this language persistence must be attributed to the constant reinforcement from Quebec, but part of it is also due to the fierce determination of the Quebecois, after their conquest by the British, to keep their language alive.

“Let us worship in peace and in our own tongue,” they said. “Let us read and write in our own tongue. All else may disappear, but this must remain our badge.”

With a century of this tradition behind them before they came to the United States, it would not be easily shed after a short train trip.

All over New England, but particularly in the mill towns where “les petits Canadas” were established, French-speaking priests were to be found, almost all of them missionary priests from Quebec who treated New England as other religious groups treated Africa or China. Not surprisingly the French Canadians clashed with the Irish-dominated hierarchy, as Germans had done before them and Poles would do after them. The key issues over which they struggled were, first, the appointment of non-French-speaking priests; second, Irish as opposed to Quebecois forms of worship; and, third, relative parish autonomy, traditional in Quebec but frowned upon in the Irish American church. Although both the French and Irish were seen in New England as “papist interlopers” by nativists, they rarely united to face their common enemies. French Canadian Catholics worshiped in three different kinds of parishes: the national parish, in which they were the dominant group and had a Quebecois priest, with the main or even all services in French; the mixed parish, with a large number (often a majority) of French Canadians, bilingual services, but no Quebecois priest; and parishes in which all services were in English despite a substantial French Canadian membership.

The worst conflicts were, classically, in the small- to medium-size mill towns and cities. In Fall River, for example, the very stronghold that Beaugrand chose to write about, the Quebecois missionary priest died in 1884 and the Irish bishop appointed an Irish successor despite the fact that French Canadians were some 85 percent of the parish. The Quebecois withdrew from the parish in a bloc and the bishop placed them all under an interdict. Rome, however, intervened, and urged the bishop to appoint a French Canadian. Similar struggles took place elsewhere. In Maine, during the incumbency of Louis S. Walsh, appointed bishop of Portland in 1906, the struggle was over attempts of the laity to control church property and again resulted in an interdict being pronounced against those who resisted his authority. On this issue Rome did not intervene and, although the Quebec hierarchy tried to, it was to no avail. The climax of these struggles came after the appointment of William Hickey as bishop of Providence, Rhode Island, in 1921. Here the struggle was over lay control of church property and, more ominously for most Quebecois, the Americanization of their parochial schools, forcing them to shift from French to English as the language of instruction. Around the turn of the century four out of ten parochial schools in New England were taught in French and had more than fifty thousand pupils. One French-Canadian-American newspaper went so far as to argue that:

A parish without a church is preferable to a parish without a Catholic school for the excellent reason that where the second is lacking, the first often becomes useless.

Bishop Hickey’s drive to Americanize was thus seen as an attack on the vital center of Quebecois culture in the United States. The cudgels were taken up by two important French Canadian national organizations: The Union St. Jean-Baptiste d’Amérique (USJB), the largest of them all, took the side of the bishop, while the Association Canado-Américaine (ACA) supported his rebellious parishioners. The last straw came when the bishop began to levy funds from unwilling parishes to support English-language parochial schools and other of his pet programs. His opponents called for more national parishes, bilingual schools—which meant, for them, French as the main teaching language—and the inviolability of parish funds. After an appeal to Rome failed, the most determined of the bishop’s opponents tried unsuccessfully to get the Rhode Island courts to block the bishop’s levies. After he won in the civil courts, the bishop hauled out the big gun: excommunication of the rebellious leaders. Despite extensive support from Quebec and the community, virtually all the leaders, including Elphège Daignault, president of the ACA, capitulated by early 1929.

The relatively slow acculturation of the French Canadians may also be seen in the political arena, where, for a long time, their potential influence, as reflected in the number of French Canadians elected to political office, was decidedly lower than either their numbers or degree of concentration would have predicted. Elliott R. Barkan, a leading authority on ethnicity and naturalization, has pointed out that French Canadians had one of the lowest naturalization rates of any American ethnic group. In 1910, for example, only 45 percent of all French Canadian males over twenty-one were naturalized and only 37 percent in the core area of New England, substantially lower than among other Canadians, Irish, English, and Scandinavian adult males. Such disparities continued for decades, and by 1930 a majority of French Canadians were still unnaturalized and their rates were well behind Italians and Poles, most of whom arrived later, as well as most other immigrant groups. In addition, the relatively slow increase in the number of native-born French Canadians, as reflected in Table 9.3, reflects the high emigration rate of French Canadians born here. The Canadian census of 1931 showed more than fifty thousand persons of French Canadian descent who were born in the United States living in Canada. This meant that the political impact of eligible French Canadian voters was lessened.

Not surprisingly, the rate of intermarriage by French Canadians was very low: Even the thought of such a thing was to many French Canadian leaders “a crime against God and a national abomination.” (One suspects that for some the second was more important than the first.) In 1880, for example, 66 percent of second-generation French Canadians had both parents born in Quebec, and about 7.5 percent had either a foreign-born mother or father of a different ethnic group. The rest had one Quebecois and one U.S.-born parent, most of whom were certainly second-generation French Canadians. One 1926 study showed that in Woonsocket, Rhode Island, the “Quebec of New England,” only 11 percent had married out, and that most of those spouses were Irish and presumably Catholic. Rates for Fall River, an early settlement area, were considerably higher: In 1880 the rate was 14 percent; it was 30 percent by 1912, 50 percent by 1937, and 80 percent by 1961, one-fifth of which were unions with non-Catholics. As Barkan notes, “even in the self-styled ‘third French city in America,’” after Montreal and Quebec City, the process of acculturation was all but irresistible.