Without the Ten Wings, it is extremely unlikely that the basic text of the Changes would have become anything more than a technical divination manual, one of many such documents circulating in the late Warring States period. But as it turned out, this particular collection of commentaries, which evolved over several centuries, proved ideally suited to the political, social, intellectual, and cultural climate of China during the long and distinguished reign of Emperor Wu of the Han dynasty (r. 141–87 BCE). In the first place, the Ten Wings reflected the eclecticism, cosmology, and “Confucian” values that came to be esteemed by Emperor Wu’s scholarly advisers. But perhaps even more important, although the individual wings were quite heterogeneous and obviously the products of different periods and editorial hands, Chinese scholars in the second century BCE, including the Grand Historian, Sima Qian (ca. 145–86 BCE), ascribed them to Confucius (ca. 551–479 BCE). This now-questionable association with the Sage invested the basic text with great stature and encouraged Chinese scholars from the Han period onward to give the document particularly careful scrutiny, and to search relentlessly for the deeper significance of its hexagrams, trigrams, lines, judgments, line statements, and even individual words.

Late Zhou–Early Han Cosmology and the Ten Wings

One of the most important philosophical ideas to emerge out of the vibrant discussions and debates that took place in China during the fourth and third centuries BCE was the widely shared notion that the general goal of human activity was to harmonize with the natural patterns of change in the universe. How these patterns might be detected and understood, and what one might do to achieve this harmony, differed substantially among various schools and individual thinkers. But for many if not most Chinese intellectuals of the time, divination offered a useful, indeed essential, means by which to understand the cosmos and one’s place in it. Naturally, then, the Changes, having originated as a fortune-telling manual, came increasingly to be viewed as a potentially valuable instrument for achieving this kind of understanding. At the same time, however, the basic text had very little to say explicitly about cosmic patterns and processes. Thus it became necessary to amplify the document in ways that took into account new and compelling ideas about the relationship among Heaven, Earth, and Humanity.

The concept of “Heaven” had evolved during the Zhou dynasty from a notion somewhat similar to the Shang dynasty’s highly personalized “Lord on High” to a less personalized idea of nature and natural process, commonly referred to as the Way or Dao. Depending on one’s philosophical persuasion, the Dao could be moral or amoral, but to virtually all Chinese thinkers of the late Zhou era, it possessed cosmic creative power without being itself a creator external to the cosmos.

Most of the cosmogonies of the late Zhou and early Han periods focused on the concept of multiplicity developing out of oneness. But the idea that eventually proved most powerful philosophically was the implicitly sexual interaction between Heaven (male) and Earth (female), which generated all phenomena. This process came to be viewed in terms of the (also implicitly sexual) interaction between yin and yang. Such sexual imagery was not always implicit, however. In the Mawangdui version of the Changes, for instance, the hexagrams that correspond to Qian (“Heaven”) and Kun (“Earth”) in the canonized version (Jian and Chuan, respectively) seem to be closely identified with male and female genitalia.1

From the late Zhou period onward, yin and yang came to be conceived in three different but related ways. First, they were viewed as modes of cosmic creativity (female and male, respectively), which not only produced but also animated all natural phenomena. Second, they were used to identify recurrent, cyclical patterns of rise (yang) and decline (yin), waxing (yang) and waning (yin). Third, they were employed as comparative categories, describing dualistic relationships that were viewed as inherently unequal but almost invariably complementary. Yang, for example, came to be associated with light, activity, Heaven, the sun, fire, heat, the color red, and roundness, while yin was correlated with Earth, the moon, water, coldness, the color black, and squareness, as well as darkness and passivity.

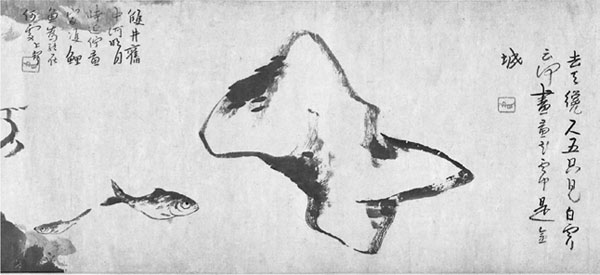

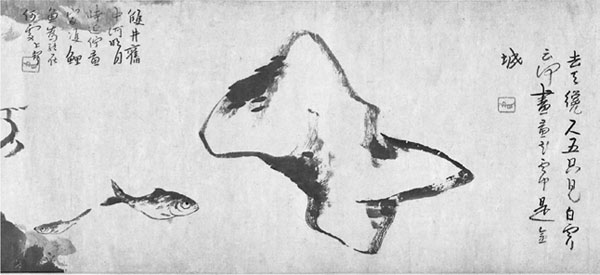

Significantly, objects or qualities that might be viewed as yang from one point of view can be seen as yin from another. For instance in figure 2.1, which shows detail from a delightful painting by Zhu Da (1624–1705), the large rock is yang, by virtue of not only predominance of light as opposed to shading but also the rock’s “superior” position and its size in relation to the fish (who seems to be staring intently at it). Yet because the rock is stationary and the fish is presumably in motion, the rock can be considered yin. And although the staring fish is clearly yin in relation to the size of the rock, it is yang in relation to the smaller fish that is swimming away from it.

For objects such as rocks and fish to exist, for patterns of movement to be detected, and for relationships to become manifest, qi was necessary. Qi, literally “breath” or “air,” is often translated as life breath, energy, pneuma, vital essence, material force, primordial substance, psychophysical stuff, and so forth. Unfortunately, no single rendering serves all philosophical and practical purposes. For now, suffice it to say that in various states of coarseness or refinement, it comprised all objects in the world and filled all the spaces between them. In late Zhou thought, “everything was assumed to be qi in some form, from eminently tangible objects like rocks and logs to more rarefied phenomena like light and heat.”2 Qi was then “simultaneously ‘what makes things happen in stuff’ and (depending on context) ‘stuff that makes things happen’ or stuff in which things happen.’”3

FIGURE 2.1

Detail from Zhu Da’s Fish and Rocks (Chinese, 1624–1705)

Handscroll; mid- to late 1600s, ink on paper, 29.2 × 157.4 cm. Copyright The Cleveland Museum of Art. John L. Severance Fund 1953.247. Reproduced with permission from the Cleveland Museum of Art.

With respect to human beings, qi in its coarser aspects becomes flesh, blood, and bones, but in its most highly refined manifestation, known as “vital essence,” it not only suffuses and animates our bodies but also becomes our “spirit.”4 “Spirit,” in late Zhou usage, had a wide range of meanings, as it does in contemporary English. But whereas in English the term almost invariably implies a sharp contrast with the material body, in classical Chinese discourse the distinction was never so clear. Spirit was viewed as an entity within the body that was responsible for consciousness, combining what Westerners would generally distinguish as “heart” and “mind.” In other words, the spiritual essence of human beings came to be viewed in terms of “the interface between the sentient and insentient, or the psychological and physical,” uniting both aspects rather than insisting on boundaries.5

The important point for our purposes is that for well over two thousand years, Chinese of various philosophical persuasions believed that by cultivating their qi to the fullest extent, and thus harnessing the highly refined spiritual capabilities of their minds, they could achieve extraordinary things. Daoist-oriented individuals, for instance, could attain immortality; Confucians, for their part, could literally “transform people” and ultimately change the world by means of ritual rectitude and moral force. According to the Doctrine of the Mean, an extremely influential work initially composed in the late Warring States period, the key to Confucian self-cultivation was sincerity—the moral integrity that enables a person to become fully developed as an agent of the cosmos: “Sincerity is Heaven’s Way; achieving sincerity is the Way of human beings. One who is sincere attains centrality without striving, apprehends without thinking.” The work goes on to assert that the person who possesses the most complete sincerity “is able to give full development to his nature, … and to the natures of other living things. Being able to give full development to the natures of other living things, he can assist in the transforming and nourishing powers of Heaven and Earth … [and thus] form a triad with them.”6 In this view, a person with fully developed sincerity can literally know the future and become “like a spirit.”

What, then, should such a cultivated individual do? The Confucian answer was to direct one’s spirit toward achieving cosmic resonance—that is, a sympathetic vibration of qi across space. This could occur between objects, the way a plucked note on one instrument resonates with the same note on another instrument, but it could also occur in the minds of human beings. In other words resonance, as a theory of “simultaneous, nonlinear causality,” was predicated on the idea that like-things could influence like-things on a cosmic as well as a microcosmic scale. Human consciousness was thus “implicit in and susceptible to the same processes of cosmic resonance that [might] affect trees, iron, magnets, and lute strings.”7 In short, harmony prevailed when like-things resonated and unlike-things were in balance.

By the early Han dynasty, these ideas had developed into a systematic philosophy of resonance and correspondence, often described in terms of “correlative thinking.” In contrast to Western-style “subordinative thinking,” which relates classes of things through substance and emphasizes the idea of “external causation,” in Chinese-style correlative thinking “conceptions are not subsumed under one another but placed side by side in a pattern”; things behave in certain ways “not necessarily because of prior actions or [the] impulsions of other things,” but because they resonate with other entities and forces in a complex network of associations and correspondences.8 Applied to cosmology, this sort of correlative thinking encouraged the idea of mutually implicated “force fields” identified, as we shall see, by highly specialized terms and linked with specific numerical values.

Han-style correlative thinking naturally centered heavily on the concepts of yin and yang, which, as indicated above, could accommodate any set of dual coordinates, from abstruse philosophical concepts such as nonbeing and being to such mundane polarities as dark and light. Another important feature of correlative thinking, though somewhat more problematical in the minds of certain scholars, was an emphasis on the so-called five agents (also translated as elements, phases, activities, and so on), identified with the basic qualities or tendencies of earth (stability), metal (sharpness), fire (heat), water (coolness), and wood (growth). Like yin and yang and the eight trigrams, each of the five agents, in various combinations and operating under different temporal and spatial circumstances, had tangible cosmic power embodied in, or exerting influence on, objects of all sorts by virtue of the sympathetic vibration of qi. Whether considered as external forces or intrinsic qualities, yin and yang and the five agents constantly fluctuated and interacted as part of the eternal, cyclical rhythms of nature. Everything depended on timing and the relative strength of the variables involved. By taking into account these variables, one could predict whether movement would be progressive or retrogressive, fast or slow, auspicious or inauspicious.

By the early Han period the five agents had come to be correlated with various seasons, directions, planets, colors, flavors, musical notes, senses, emotions, organs, grains, sacrifices, punishments, and so forth. They were also correlated with different states or phases of yin and yang. As one concrete but relatively simple illustration, let us look at the construction of calendrical time. In terms of yin and yang, the year can be divided into four parts: two solstices and two equinoxes. The winter solstice marks the point of fullest yin, when yang begins to emerge out of the cold. From this point onward, yin starts to decline and yang increases. At the spring equinox, yin and yang are in perfect balance. The process continues until the summer solstice, when yang is at its apex and yin is at its nadir. Thereafter yang declines and yin increases until the winter solstice, when the cycle begins again.

From the standpoint of five agents correlations, during the first month of the lunar calendar the power of wood prevails. This continues until the fourth month, when fire dominates. The sixth month is ruled by earth. The seventh, eighth, and ninth months are controlled by metal, and the tenth, eleventh, and twelfth months fall under the predominant influence of water. Armed with this sort of correlative knowledge, one could determine at any given time of year which directions were most auspicious, which planetary configurations were most favorable, which rituals should be performed, which foods, offerings, and medicines were most appropriate, and so on.9

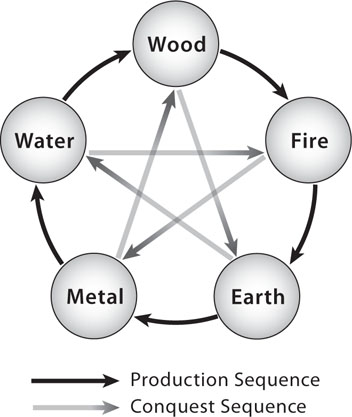

Like yin and yang, the five agents worked in sequences, but the order of displacement indicated above is somewhat unusual, for in the standard “mutual conquest” sequence of the five agents, water conquered fire, fire conquered metal, metal conquered wood, wood conquered earth, and earth conquered water. By contrast, in the “mutual production” sequence, wood produced fire, fire produced earth, earth produced metal, metal produced water, and water produced wood. There have been many explanations of how these two related processes occur in nature, some of which are fairly commonsensical and others of which involve a stretch of the imagination—for instance wood is sometimes said to overcome earth by “digging it” (as with a wooden shovel).

We shall see more of the five agents, along with several related configurations of cosmic power, later in this book. For now the important point to keep in mind is that for the Changes to flourish in this particular intellectual environment it needed philosophical flesh, something more substantial and sophisticated than the bare bones of the basic text. Body weight came in the form of the provocative, sometimes powerful, and often poetic commentaries of the Ten Wings.

FIGURE 2.2

Five Agents Sequences

The Ten Wings in the Early Life of the Yijing

As indicated at the outset of this chapter, the Ten Wings are heterogeneous in content. The first and second wings, together known as the “Commentary on the Judgments,” and the third and fourth, collectively titled the “Commentary on the Images,” probably date from the sixth or fifth century BCE. They are almost certainly the oldest systematic treatises on the basic text of the Changes. The Commentary on the Judgments explains each judgment by referring to its phrases, its hexagram symbolism, or the location of its yin (broken) and yang (solid) lines. The Commentary on the Images consists of two subsections: a “Big-Image Commentary,” which discusses the images associated with the two primary trigrams of each hexagram (lines 1–3 and 4–6, respectively), and a “Small-Image Commentary,” which refers to the symbolism of the individual lines. The two parts of the “Great Commentary,” also known as the “Commentary on the Appended Statements,” are generally described as the fifth and sixth wings. Using somewhat different rhetorical devices in each of its two sections, this commentary offers a sophisticated, although sometimes rather disjointed, discussion of both the metaphysics and the morality of the Changes, often citing Confucius for authority.

The rest of the Ten Wings lack the divided structure of the first six. The “Commentary on the Words of the Text” addresses only the first two hexagrams of the basic text, and some scholars believe that it represents fragments of a much lengthier but no longer extant work. The “Explaining the Trigrams” commentary consists primarily of correlations that suggest a conscious effort on the part of the author(s) to expand the symbolic repertoire of the Yijing. The wing titled “Providing the Sequence of the Hexagrams” aims at justifying the received order of the hexagrams, and the last, the “Hexagrams in Irregular Order,” offers definitions of hexagrams that are often cast in terms of contrasting pairs. Different editions of the Changes organize this material in different ways.10

The Great Commentary is the most philosophically interesting of the Ten Wings. It probably assumed something close to its final form around 300 BCE, and from the Han period to the present this document has received far more scholarly attention than any other single wing.11 We may think of it as an early biography of the Changes in the sense that it attempts to explain the life and fundamental meaning of the basic text, using a great many quotations from its line statements and judgments. The “Appended Statements” commentary of the Mawangdui manuscript performs a similar function, using much the same language and imagery.

The primary goal of the Great Commentary was to explain how the hexagrams, trigrams, and lines of the document duplicated the fundamental processes and relationships occurring in nature, enabling those who consult the Yijing with sincerity and reverence to partake of a potent, illuminating, activating, and transforming spirituality. By participating fully in this spiritual experience, the reader could discern the patterns of change in the universe and act appropriately. As the Great Commentary states:

Looking up, we use it [the Changes] to observe the configurations of Heaven, and, looking down, we use it to examine the patterns of Earth. Thus we understand the reasons underlying what is hidden and what is clear. We trace things back to their origins then turn back to their ends. Thus we understand the axiom of life and death…. The Changes is without consciousness and is without deliberate action. Being utterly still it does not initiate, but when stimulated it is commensurate with all the causes for everything that happens in the world. As such, it has to be the most spiritual thing in the world, for what else could possibly be up to this?12

In other words, the Yijing showed how human beings could “fill in and pull together the Dao of Heaven and Earth,” thus helping to create and maintain cosmic harmony through their spiritual attunement to the patterns and processes of nature. By using the Changes responsibly, humans could not only “know fate” but also do something about it.

The process of consulting the Changes involved careful contemplation of the “images” associated with, and reflected in, the lines, trigrams, and hexagrams of the basic text. According to the Great Commentary, sages like Fuxi “had the means to perceive the mysteries of the world and, drawing comparisons to them with analogous things, made images out of those things that seemed appropriate.”13 Initially, then, there were only hexagram images, trigram images, and line images—pure signs unmediated by language. But later on, hexagram names, judgments, and line statements appeared in written form to help explain these abstract significations. Thus subsequent sages came to use words to identify “images of things” (natural phenomena, such as Heaven and Earth, mountains, rivers, thunder, wind, and fire), “images of affairs” (social and political phenomena, including institutions, war, famine, marriage, and divorce), and “images of ideas” (thoughts, mental pictures, states of mind, emotions, and any other sensory or extrasensory experiences). Later commentators sometimes likened images to “flowers in the mirror” or “the moon in the water”—that is, reflections of things that “cannot be described as either fully present or fully absent.”14

Numbers provided an additional tool for understanding patterns of cosmic change. Indeed, the Great Commentary tells us that in conjunction with hexagrams, numbers “indicate how change and transformation are brought about and how gods and spirits are activated.”15 Vague but provocative passages such as these would later inspire an enormous amount of scholarship designed to identify and explain the complex relationship between “numbers and images,” but the main focus of the Ten Wings is on images. In fact at certain points in the text this emphasis seems to diminish the value of the written word itself. For example the Great Commentary avers that “Writing does not exhaust words, and words do not exhaust ideas…. The sages [therefore] established images in order to express their ideas exhaustively … [and] established the hexagrams in order to treat exhaustively the true innate tendencies of things.”16

Ideally, then, if one is able to grasp the meaning of the image, words become unnecessary. In fact, however, the ancient sages did their fair share of explicating. For instance the Great Commentary states that “They [the sages] appended phrases to the lines [of the hexagrams] in order to clarify whether they signified good fortune or misfortune and [they] let the hard [yang] and the soft [yin] lines displace each other so that change and transformation could appear.” According to this text, good fortune and misfortune involve images of failure or success, respectively. Regret and remorse involve images of sorrow and worry. Change and transformation involve images of advance and withdrawal. It goes on to say:

The judgments address the images [i.e., the concept of the entire hexagram], and the line texts address the states of change. The terms “auspicious” and “inauspicious” address the failure or success involved. The terms “regret” and “remorse” address the small faults involved. The expression “there is no blame” indicates success at repairing transgressions…. The distinction between a tendency either to the petty or to the great is an inherent feature of the hexagrams. The differentiation of good fortune and misfortune depends on the phrases [i.e., the line statements].17

The Great Commentary also tells us that the hexagrams “reproduce every action that occurs in the world,” and as a result, “once an exemplary person finds himself in a situation, he observes its image and ponders the phrases involved, and, once he takes action, he observes the change [of the lines] and ponders the prognostications involved.”18 Essential to this process was an acute attunement to the seminal first stirrings of change, which afford the opportunity for acting appropriately at the most propitious and efficacious time. The technical term in the Yijing for this moment is “incipience” (often described metaphorically as a door hinge, trigger, or pivot)—that “infinitesimally small beginning of action, the point at which the precognition of good fortune can occur.”19 Once again in the words of the Great Commentary, “It is by means of the Changes that the sages plumb the utmost profundity and dig into the very incipience of things. It is profundity alone that thus allows one to penetrate the aspirations of all the people in the world; it is a grasp of incipience alone that thus allows one to accomplish the great affairs of the world.”20

In short, by virtue of their spiritual capabilities and comprehensive symbolism, the sixty-four hexagrams of the Yijing provided the means by which to understand all phenomena, including the forces of nature, the interaction of things, and the circumstances of change. Like yin and yang, the five agents, the eight trigrams, and other cosmic variables, hexagrams were always in the process of transformation, but at any given time they also revealed qualities and capacities. These qualities and capacities were naturally reflected in the relationship of the two constituent trigrams within a given hexagram. For instance the Zhen (“Thunder”) trigram causes things to move, Sun (“Wind”) disperses things, Kan (“Water”) moistens things, Li (“Fire”) dries things, Gen (“Mountain”) causes things to stop, Dui (“Lake”) pleases things, Qian (“Heaven”) provides governance, and Kun (“Earth”) shelters things.21

In what other ways did the Ten Wings help to explain the cryptic basic text of the Changes? Let us look first at the Commentary on the Judgments and the Commentary on the Images, keeping in mind that the latter commentary provides an analysis of the hexagram imagery as a whole (the “Big Image”) as well as an analysis of each individual line (the “Small Image”). The focus here is on the Gen hexagram (number 52), which has already been discussed briefly in both the introduction and chapter 1.

By the early Han dynasty, if not well before, the Zhou dynasty idea that Gen might mean “to cleave” or “to glare at” had given way to a very different conception of the term. From Han times onward, the dominant meanings that came to be attached to the Gen hexagram now had to do with “stillness” and “restraint.”22 Below is a rendering of the basic text of Gen, based on a Han dynasty understanding, together with a few commentaries drawn from the Ten Wings.23

JUDGMENT: Restraint [or Stilling] takes place with the back, so the person in question does not obtain the other person. He goes into that one’s courtyard but does not see him there. There is no blame.

COMMENTARY ON THE JUDGMENTS: Gen means “stop.” When it is time to stop, one should stop; when it is time to act, one should act. If in one’s activity and repose he is not out of step with the times, his Dao should be bright and glorious. Let Restraint operate where restraint should take place, that is, let the restraining be done in its proper place. Those above and those below stand in reciprocal opposition to each other and so do not get along. This is the reason why, although “one does not obtain the other person” and “one goes into one’s courtyard but does not see him there,” yet there is no blame.

COMMENTARY ON THE IMAGES: United mountains [i.e., doubled Gen trigrams]: this constitutes the image of Restraint. In the same way, the exemplary person is mindful of how he should not go out of his position.

Line 1: Restraint takes place with the toes, so there is no blame, and it is fitting that the person in question practices perpetual perseverance.

COMMENTARY ON THE IMAGES: If “Restraint takes place with the toes,” one shall never violate the bounds of rectitude [or “stray off the correct path”].

Line 2: Restraint takes place with the calves, which means that the person in question does not raise up [i.e., rescue] his followers. His heart feels discontent.

COMMENTARY ON THE IMAGES: “The person in question does not raise up his followers,” nor does he withdraw and obey the call.

Line 3: Restraint takes place with the midsection, which may split the flesh at the backbone,24 a danger enough to smoke and suffocate the heart.

COMMENTARY ON THE IMAGES: If “Restraint takes place with the midsection,” the danger would “smoke and suffocate the heart.”

Line 4: Restraint takes place with the torso. There is no blame.

COMMENTARY ON THE IMAGES: “Restraint takes place with the torso,” which means that the person in question applies restraint to his own body.

Line 5: Restraint takes place with the jowls, so the words of the person in question are ordered, and regret vanishes.

COMMENTARY ON THE IMAGES: “Restraint takes place with the jowls,” so the person in question is central and correct.

Line 6: The person in question exercises Restraint with simple honesty, which results in good fortune.

COMMENTARY ON THE IMAGES: The good fortune that springs from “exercising Restraint with simple honesty” means that one will reach his proper end because of that simply honesty.

Although these glosses from the Ten Wings certainly did not resolve all ambiguities or eliminate all future controversies regarding the possible meanings of Gen’s judgment and line statements,25 they did underscore a radical interpretive shift that transformed the Gen hexagram from an apparent description of a ritualized sacrifice to a set of prescriptions for self-control and ethical behavior.

In many instances the Commentary on the Judgments focuses not only on the general meaning of the hexagram in question, as indicated in the example above, but also on the specific symbolism of its individual trigrams as well as the meaning of its lines and the relationship between them. For an illustration we may take Tongren (number 13). The Commentary on the Judgments states (in full):

Fellowship is expressed in terms of how a weak line [yin in the second place] obtains a position such that, thanks to its achievement of the Mean, it finds itself in resonance with the [ruler of the] Qian trigram [the yang line in the fifth place]. Such a situation is called Tongren [Fellowship]. When the judgment of the Tongren hexagram says “it is by extending Fellowship even to the fields that one prevails” and “thus it is fitting to cross the great river,” it refers to what the Qian trigram accomplishes. Exercising strength through the practice of civility and enlightenment, [the second yin line and the fifth yang line] each respond to the other with their adherence to the Mean and their uprightness: such is the rectitude of the exemplary person. Only the exemplary person would be able to identify with the aspirations of all the people in the world.26

The Big-Image Commentary tells us that “This combination of Heaven [the upper trigram, Qian] and Fire [the lower trigram, Li] constitutes the image of Tongren. In the same way the exemplary person associates with his own kind and makes clear distinctions among things.”27

Although the Big-Image Commentary supplies the overall trigram imagery for each individual hexagram—based, as we have seen, on the relationship of its two primary trigrams—the commentary known as Explaining the Trigrams establishes relationships among all eight. For instance, we are told: “As Heaven [symbolized by the Qian trigram] and Earth [Kun] establish positions, as Mountain [Gen] and Lake [Dui] reciprocally circulate qi, as Thunder [Zhen] and Wind [Sun] give rise to each other, and as Water [Kan] and Fire [Li] unfailingly conquer each other, so the eight trigrams combine with one another in such a way that, to reckon the past, one follows the order of their progress, and, to know the future, one works backward through them.”28 This passage not only indicates that there are important resonant connections among trigrams independent of whatever relationship they might have within any given hexagram; it also indicates that different systems of ordering the trigrams will yield different understandings of the past and the future.

But the Explaining the Trigrams commentary does even more: it attaches meanings to each of the eight trigrams that go well beyond the basic significations they possessed prior to the Han (as indicated in the quotation above and in chapter 1). A careful reading of this commentary reveals, for example, that the trigram Gen not only possesses the fundamental attributes of mountains (restraint, stillness, stopping, stability, endurance); it also has the nature of a dog; it “works like the hand”; it produces the youngest son (as one of the “offspring” of the Qian and Kun trigrams); it signifies maturity; it is located in the northeast; and it has features associated with footpaths, small stones, gate towers, tree fruit, vine fruit, gatekeepers and palace guards, the fingers, rats, the black jaws of birds and beasts of prey, and the attributes of trees that are both sturdy and gnarled.29

Similarly, the Sun (also known as Xun) trigram, in addition to its basic meaning of Wind (hence qualities of compliance and accommodation), has the nature of a rooster; it “works like the thigh”; it produces the eldest daughter; it is located in the southeast; and it has features associated with wood; with things that are straight, lengthy, and tall; and with carpenters, freshness, purity, and neatness. We are also told that with respect to men, Sun represents “the balding, the broad in the forehead, the ones with much white in their eyes, the ones who keep close to what is profitable and who market things for threefold gain.” At the end point of its development, Sun signifies impetuosity.30 Let us keep these kinds of trigram associations in mind as we explore the complexities of Yijing analysis later on in this biography.

Most of the other Ten Wings say comparatively little about lines or trigrams, although the Great Commentary offers a few general interpretive points to keep in mind. It tells us, for example, that the three odd-numbered (yang) trigrams—Zhen, Kan, and Gen—each of which has one “sovereign” and two “subjects” (i.e., one solid line and two broken lines), show the way of the exemplary person, while the three even-numbered (yin) trigrams—Sun, Li, and Dui—each of which has two “sovereigns” and one “subject” (i.e., two solid lines and one broken line), illustrate the way of the inferior person. The Great Commentary also states that “The first lines [of a hexagram] are difficult to understand, but the top lines are easy, because they are the roots and branches, respectively [i.e., the beginnings and endings]…. The second lines [of a hexagram] usually concern honor, while the fourth lines usually concern fear…. The third lines usually concern misfortune, while the fifth lines usually concern achievement.”31

The Providing the Sequence commentary explains the developmental logic of the received order of the hexagrams, but in a rather forced and unconvincing way. It begins:

Only after there were Heaven [Qian, number 1] and Earth [Kun, number 2] were the myriad things produced from them. What fills Heaven and Earth is nothing more than the myriad things. This is why Qian and Kun are followed by Zhun [number 3]. Zhun here signifies repletion. Zhun is when things are first born. When things begin life, they are sure to be covered. This is why Zhun is followed by Meng. Meng [number 4] here indicates juvenile ignorance, that is the immature state of things.32

In the Hexagrams in Irregular Order commentary, some of the symbolism is expressly oppositional. Thus, for example, the Qian hexagram (number 1) is represented as hard and firm while Kun (number 2) is described as soft and yielding; Bi (number 8) involves joy while Shi (number 7) indicates dismay. Zhen (number 51) means a start while Gen (number 52) involves a stop. Dui (number 58) means “to show yourself” while Sun (number 57) means “to stay hidden.”33 These interpretations from the Hexagrams in Irregular Order differ significantly from the “demonstrations” and “provisions” laid out in the following passage from the Great Commentary:

Sun [“Compliance,” number 57] demonstrates how one can weigh things while yet remaining in obscurity. Lü [“Treading,” number 10] provides the means to make one’s actions harmonious. Qian [“Modesty,” number 15] provides the means by which decorum exercises its control. Fu [“Return,” number 24] provides the means to know oneself. Heng [“Perseverance,” number 32] provides the means to keep one’s virtue whole and intact. Sun [“Diminution,” number 41] provides the means to keep harm at a distance. Yi [“Increase,” number 42] provides the means to promote benefits. Kun [“Impasse,” number 47] provides the means to keep resentments few. Jing [“The Well,” number 48] provides the means to distinguish what righteousness really is. Sun [“Compliance,” number 57] provides the means to practice improvisations.34

Sometimes the Great Commentary organizes hexagrams according to themes, such as the following cluster pertaining to virtue: Lü (“Treading,” number 10) “is the foundation of virtue.” Qian (“Modesty,” number 15) “is how virtue provides a handle on things.” Fu (“Return,” number 24) “is the root of virtue.” Heng (“Perseverance,” number 32) “provides virtue with steadfastness.” Sun (“Diminution,” number 41) “is how virtue is cultivated.” Yi (“Increase,” number 42) “is how virtue proliferates.” Kun (“Impasse,” number 47) “is the criterion for distinguishing virtue.” Jing (“The Well,” number 48) “is the ground from which virtue springs.” Sun (“Compliance,” number 57) is the controller of virtue.35

From the relatively small sample of interpretive possibilities mentioned above, it should be clear that a hexagram like Sun (number 57) might provide several kinds of guidance: (1) how (or why) “to stay hidden,” (2) how to weigh things “while yet remaining in obscurity,” (3) how to practice improvisations, and (4) how to control virtue. And if we factor the Mawangdui version of the Sun hexagram into the equation, yet another variable appears: the idea of making “calculations” rather than being “compliant.”36 Moreover, as we shall see, the guidelines discussed abosve are only the beginning of Yijing consultation. We have not, for example, begun to explore systematically the meaning(s) of Sun’s doubled trigrams, their relationship with other trigrams (especially Zhen, “Thunder,” as indicated above), the developmental structure of Sun’s six lines, or the ways that Sun might be related to its “opposite” hexagram, Dui (number 58).

In short, the Ten Wings of the Yijing, even without the alternative readings provided by the Mawangdui manuscript and other versions of the Changes, vastly enhanced its symbolic repertoire. Although the content of the classic became fixed in 136 BCE, for the next two thousand years scholars and diviners enjoyed an enormous amount of latitude in interpreting the work. In the meantime the Great Commentary became the locus classicus for virtually all discussions in China of time, space, and metaphysics, investing the Yijing with extraordinary philosophical authority. In addition this amplified and state-sanctioned version of the Changes became a repository of concrete symbols and general explanations that proved serviceable in such diverse realms of knowledge as art, literature, music, mathematics, science, and medicine.