16 |

Enhancing Education at School and at HomeMETHODS FOR SUCCESS FROM KINDERGARTEN THROUGH GRADE 12with Linda J. Pfiffner, PhD |

16 |

Enhancing Education at School and at HomeMETHODS FOR SUCCESS FROM KINDERGARTEN THROUGH GRADE 12with Linda J. Pfiffner, PhD |

Now that you’ve found the best possible setting for your child’s education, you can begin to look at specific techniques for maximizing school success on a day-to-day basis. Here is another area where you must become an expert; it may very well be up to you to help plan the intervention and train the teacher(s) in the effective use of classroom modifications and child behavior management programs. It is certainly up to you to see that your child’s education is enhanced by what goes on at home. This chapter goes into detail on general principles and specific methods for helping a child with ADHD succeed in school. Even though it focuses on the classroom, this chapter contains many suggestions that could easily be adapted for use at home by parents in getting work done at home and improving the home behavior of a child with ADHD. So as you read it, keep this alternative use of these methods in mind.

Remember to try to involve your child in this process of improving his school success to increase the child’s motivation to succeed. Include any child over age 7 in some of your initial planning meetings with a teacher. This gives the child some input into setting goals and determining appropriate and valuable rewards and penalties for behavior. Among the important products of such meetings are behavioral contracts that outline the details of the programs and can be signed by parent, teacher, and child to help maintain the consistent use of the program over time and to clarify each person’s role.

GENERAL PRINCIPLES FOR SCHOOL MANAGEMENT

Whether or not medication is used, a number of important principles are helpful to keep in mind in developing classroom management programs for your child with ADHD. These stem from the theory presented in Chapter 2 that ADHD involves an impairment in your child’s executive abilities and self-regulation. They are also founded on the principles for managing your child at home given in Chapter 11.

1. Rules and instructions must be clear, brief, and (wherever possible) represented physically in the form of charts, lists, and other visual reminders. Relying on the child’s memory and on verbal reminders is often ineffective. Encourage the child to repeat instructions out loud and even to utter them softly to himself while following through on the instruction.

2. Rewards, punishments, and feedback used to manage the child’s behavior must be delivered swiftly and immediately, and the entire approach to using consequences must be well organized, systematic, and planned.

3. Frequent feedback or consequences for following the rules are crucial to maintaining the child’s compliance.

4. Children with ADHD are less sensitive to social praise and reprimands, so the consequences for good or bad behavior must be more powerful than those needed to manage the behavior of children without ADHD.

5. Rewards and incentives must be put in place before punishment is used, or your child will come to see school as a place where she is more likely to be punished than rewarded. Make sure the teacher waits a week or two after setting up a reward program at school before starting to use punishment. Then make sure the teacher gives away two to three rewards for each punishment. When punishment fails, first determine whether the extent to which rewards are available is insufficient; when it is, punishment will not control your child’s behavior.

6. Token reward systems can be kept effective over an entire school year with minimal loss of power, provided that the rewards are changed frequently. Children who have ADHD become bored with particular rewards faster than other children, and teachers who fail to recognize that fact often give up on a token program too soon, believing it has stopped working when it is just boredom with the specific privileges children can purchase with their tokens that is the problem.

7. Anticipation is the key with children who have ADHD, especially during times of transition. To ensure that your child is aware of an impending shift, ask the teacher to follow the strategies presented in Chapter 12: (a) review the rules before going into the new activity; (b) have the child repeat these rules, including rewards for good behavior and punishment for misbehavior; and (c) follow through on this plan once the activity begins. Think aloud, think ahead is the important message for educators here.

You can also share some of the principles from Chapter 9 with your child’s teachers: (1) strive for consistency, (2) do not personalize the child’s problems, (3) maintain a disability perspective on the child, and (4) practice forgiveness. With these rules in mind, a creative teacher can easily devise an effective management program for your child with ADHD.

8. But sometimes children with ADHD may need extra help outside of school to stay on pace with typical children in getting school homework done or keeping up their academic skills and knowledge. Some parents step in and play the role of tutor to the child, which in some cases can work very well. We have found, however, that many parents make poor tutors or find that issues between the parent and child that arose in other situations carry over to adversely affect the time set aside for this tutoring. For these reasons, and others, we often encourage parents to hire a formal tutor to work with their child several times a week. In addition to such a tutor, or instead of one, parents should check out the self-taught courses on the Internet at Khan Academy (www.khanacademy.org). These are courses designed for children and teens to complete on their own and cover many of the academic subjects that children and teens are likely to be taking at school. They use a better and self-paced format that seems beneficial for the child with ADHD. Parents (or a tutor) can also work together with the child or teen on these courses initially. The courses are free.

BEHAVIOR MANAGEMENT METHODS FOR THE CLASSROOM

Positive and negative consequences are the most effective tools for behavior management in the classroom, just as they are at home. Positive consequences usually include praise, tokens and tangible rewards, and special privileges. Punishments commonly are ignoring, verbal reprimands, fines or penalties in a token system, and time-out. The greatest improvement in classroom behavior and academic performance is likely to come only from a combination of strategies.

Using Positive Consequences

Teacher Attention

Praise and other forms of positive teacher attention such as a smile, nod, or pat on the back are some of the most basic management tools teachers have at their disposal. Positive attention is valued by most children, including your child, though attention alone is rarely enough to manage all of the problems children with ADHD may have at school.

“The teacher asked me, ‘Why should I give your child lots of rewards for behaving well when I don’t do this for the children who behave normally? They’ll resent it.’ How can I respond?”

Giving praise and acknowledgment may seem simple, but the organized and systematic use of such attention requires great skill. The teacher must be specific about what is praiseworthy and must convey genuine warmth. Praise must be delivered quickly and must vary in wording to have the best strategic effect. Effective use of praise also requires increased monitoring or supervision, so the teacher can “catch the child being good” more often and give the positive consequences earned. But this is easier said than done. The demands on a teacher’s time and attention in the average classroom are considerable. Supervising your child more closely inevitably competes with monitoring all the other children and teaching the curriculum. Some teachers may even feel that your child does not deserve this extra attention and supervision—that the other children in the class do not get this kind of attention for behaving well, so it is not fair to give it to your child for misbehaving. If your teacher makes such remarks, share your knowledge as discussed in Chapter 15, so the teacher understands that ADHD is a disability—not simply naughtiness or laziness. Society often makes exceptions for people with disabilities, and in this case children with ADHD are no exception. Also, note that other children may not require so much feedback to continue to perform well, while the child with ADHD may fall behind and do poorly in school without it. The fact that we don’t need a ramp to get over a curb in the roadway or up the stairs into a building doesn’t mean that people with physical disabilities shouldn’t have them available, nor does it mean we will resent such people with disabilities for having them available. So this line of argument by a teacher really doesn’t make any sense.

Using Cues to Provide Consequences

Several devices can be used to help a teacher remember to provide frequent feedback to a child with ADHD: (1) Smiley face stickers can be placed about the classroom at points where the teacher may frequently glance, as reminders to check out what the student with ADHD is doing and praise the child if it is at all positive. (2) The teacher can also set the timer on her smart phone or even set a simple spring-wound cooking timer to go off periodically as another reminder to stop and monitor the ADHD student. (3) A soft tone can be put onto a digital recorder at random intervals (more frequently for the first week or two and then spaced out farther) over a 90-minute or 120-minute period to remind the teacher to check on the student and provide praise as appropriate. For students 8 years old and up, the teacher can even use this type of cueing program to teach self-monitoring. The student gets a small white file card divided down the middle to form two columns with a plus sign (+) or smiley face over the left column and a minus sign (–) or frowny face over the right column. Whenever the child hears the tone, he can record a point (hash mark) in the plus column for obeying instructions or one in the minus column for being off-task. The teacher’s job is to check quickly on the child’s behavior when the tone sounds and make sure the student is recording accurately. Self-monitoring is enhanced when an easel at the front of the classroom lists five or so rules for each class period, so the teacher can flip to the appropriate page throughout the day. (4) The teacher can also start a class period with about 10 bingo chips in, say, a left pocket, moving a chip to the right pocket whenever positive attention has been given to your child. The goal is to move all 10 chips to the right pocket by the end of that class period.

Tangible Reward and Token Programs

Despite the usefulness of praising good behavior and ignoring misbehavior, these procedures are often not enough by themselves. A variety of more powerful rewards, often in the form of special privileges such as helping the teacher, earning extra recess, playing special games, having computer time, and doing art projects, can be given. It’s important that a long list of choices be available to prevent boredom. Also, because frequent rewards are important to helping a child with ADHD, some of these rewards should be possible to earn a few times a day. More valuable rewards, like a pizza party or special class outing, should be earned over longer periods of time, such as weekly.

Using token, point, or chip programs to earn rewards can also be very effective (see Chapter 11). The teachers may find it helpful to interview the child with ADHD about the kinds of activities or other rewards the child would like to earn, as well as selecting some based on observation of the child. If few powerful enough rewards are available at school, you may have to set up a home-based reward program, as discussed later in this chapter. Or you could donate a favorite type of toy or piece of play equipment from home for the teacher to use with a classroom reward system.

One very powerful reward kids seem to like these days is to be allowed to play video games. We have been successful in approaching local civic clubs for donations of such games or some funds to offset the expense of buying handheld inexpensive ones by giving presentations on the seriousness of classroom behavioral problems and the critical need for such rewards in the management of disruptive children. Teachers can also check the local Goodwill store for any used older generation gaming systems and games that may still be quite desirable to have in the classroom as a source of rewards, or parents can find them at such stores and donate them to the classroom.

Token programs can also be used for a group of children, with all class members earning rewards based on the behavior of one or more of the classmates or of the entire group. Group programs can be particularly effective when peers are rewarding a child with ADHD for disruptive behavior by laughing or joining in the inappropriate conduct. In some group programs, the performance of a student with ADHD serves as the standard for determining how much reward is given to the entire class. In other cases, tokens or points are given to each child in the classroom, including the child with ADHD, based on how the student with ADHD has done. This has the advantage of motivating the other children in the class to help the student with ADHD behave well, follow the rules, and get work done. A different form of this program involves breaking the class up into small teams, which earn or lose points depending on their behavior. The team with the greatest number of positive points or fewest negative points earns privileges for that entire team. The group approach has the advantage of not singling out the child with ADHD, but this benefit must be weighed against the potential for the child with ADHD to be vilified for causing the whole class to be penalized when the student with ADHD does poorly.

Token programs can also be used to increase your child’s academic productivity and work accuracy. In one program we set up, the token system involved children earning checks on an index card for each correct answer, with the checks redeemable for a large variety of backup rewards at school (such as candy, free time, school and art supplies, picnics in the park, etc.) later in the day. This program sharply increased math and reading scores, and it reduced disruptive behavior to a level similar to that seen when the children had previously been on medication.

In another, very novel program, tokens were given for successful completion of four tasks: two that involved learning to read and using new vocabulary words in sentences and two that involved teaching these tasks to another student, called peer tutoring. When a token had been earned for completion of each of these four tasks, it was exchanged for 15 minutes of play on a pinball machine or electronic game in the classroom. Additional game time was earned whenever a child passed a subject’s unit test, such as a chapter in the reading assignment. This token program dramatically increased both the completion of schoolwork and the accuracy of the work. It also improved the students’ performance on the school district’s weekly reading exams. This program was carried out by just a single teacher.

The types of goals selected for token programs are critical to their success. Giving rewards for outstanding performance works for other children, but many children with ADHD need affirmation for lesser achievements. At the start, therefore, rewards should be given for smaller accomplishments—such as for completing a part of the work when the child has a long history of failing to complete work or for being quiet for part of the day when the child is often disruptive throughout the day.

Tokens also need to be adjusted for the age of the children involved. Tangible tokens, such as poker chips, are very important in managing 4- to 7-year-olds, while points, numbers, or hash marks on a card can be used through high school. With preschool or kindergarten children, however, using plastic chips may actually serve as a distraction, so we have often used a small fabric pocket pinned to the back of a child’s clothing. When tokens are dispensed, the teacher reaches out to the child, slips the token into the child’s “knapsack,” and gives a light affectionate squeeze to the child’s shoulder. Several times each day, the pocket is removed and emptied, and the child can exchange the tokens for various classroom privileges.

Using Negative Consequences

Ignoring

Ignoring is often used as one of the first treatments for mild misbehavior, especially when children’s misbehavior seems to be encouraged by teacher attention. Unfortunately, it is not easy to distinguish the cases when a child with ADHD is trying to get attention by misbehaving from those in which the child is not. Most misbehavior stems from your child’s biological deficits in inhibiting behavior and sustaining attention. Ignoring does not mean simply failure to monitor a child’s behavior; it means contingent withdrawal of teacher attention when the misbehavior occurs. It works best in combination with praise—for example, praising the children who stay in their seats while withdrawing attention from a child with ADHD who is wandering around the classroom. But even when a powerful reward program is used as well, ignoring may not be sufficient punishment to teach a child with ADHD to stop misbehaving. In these cases, additional negative consequences appear necessary. Ignoring is also not indicated in cases of aggression or destruction—acts of misconduct that deserve swift, certain punishment to discourage their repetition in the future.

Reprimands

The reprimand is probably the most frequently used negative consequence in the classroom, but its effectiveness can vary considerably. Brief, specific reprimands given swiftly, without much emotion (business-like), and consistently backed up with other punishment if not heeded can be effective for your child with ADHD. Reprimands that are vague, delayed, long-winded, emotional, and not backed up with other consequences are not helpful. Reprimands mixed with positive feedback also fail, as do inconsistently delivered reprimands. For example, children who are sometimes reprimanded for calling out but other times responded to as if they had raised their hands are apt to continue, if not increase, their calling out. Reprimands also appear to be more effective when delivered with eye contact in close proximity (nearby) to a child. In addition, children respond better to teachers who deliver consistently strong reprimands at the outset of the school year than to teachers who gradually increase the severity of their discipline over time. In summary, reprimands, like praise, are not always sufficient to change your child’s behavior. More powerful backup consequences may be necessary.

Behavior Penalties or Fines

Penalties, or what professionals call response cost, involve the loss or removal of a reward based on the display of some misbehavior. Lost rewards can include a wide range of privileges and activities or even tokens in a token system (fines). Fining can easily be adapted to a variety of behavior problems and situations; it is more effective than the use of reprimands alone and seems to increase the effectiveness of reward programs.

In one research study, the teacher deducted one point every time she saw a child not working. Each lost point meant a loss of 1 minute of free time. A digital counter was placed at each child’s desk to keep track of the child’s point totals. One child’s counter consisted of numbered cards that could be changed to a lesser number each time a point was lost. The teacher had an identical counter on her desk where she kept track of point losses. The child was instructed to match the number value on his counter with that of the teacher’s frequently during the class. A second child had a battery-operated electronic “counter” with a number display, called the Attention Trainer (you can see it at www.addwarehouse.com or just enter the name in your Internet search engine, like Google, to learn more about it). The teacher simply took away points for off-task behavior on the display by using a remote transmitter like that used in an electronic garage-door opener.

Both of these methods increased the time the children paid attention to their work and their academic performance. The results were almost as good as when the children had been on stimulant medication. The swiftness with which the consequences were delivered in either procedure certainly helped to make the program work. In addition, these procedures were very easy to use, practical, and efficient for the teacher.

As with other punishments, however, the use of fines or penalties has raised some concerns about possible negative effects. Ways to reduce these are discussed later in the chapter. We have found that giving lots of rewards in class and avoiding unreasonably strict standards can reduce the number of penalties that need to be used.

Time-Out

Time-out was discussed for use at home in Chapter 11. The term really means the time during which positive reinforcement or rewards are not available. It is frequently recommended for use at school with children who have ADHD and are particularly aggressive or disruptive. Time-out can be applied in several ways. One of these, often called social isolation, involves placing the child in a chair in an empty room for a few minutes. It has come under much criticism lately. Now professionals generally recommend just removing the child from the area of rewarding activities rather than from the entire classroom. This may involve having the child sit in a three-sided cubicle or sit facing a dull area (for example, a blank wall) in the classroom. In other cases, children may be required to put their work away (which eliminates the opportunity to earn rewards for academic performance) and to put their heads down (which reduces the opportunity for rewarding interaction with others) for brief periods of time.

Another time-out procedure uses a good-behavior clock. Rewards (penny trinkets, candy, etc.) are earned by a child and by the class based on that child’s behaving appropriately for a specified period of time. A clock runs whenever the child is paying attention, working, or behaving appropriately. The clock is stopped for a short period of time when the child is disruptive or off-task. Studies have found dramatic decreases in hyperactive and disruptive behavior as a result of this method.

Most time-out programs set specific rules that must be fulfilled before the child can be released from time-out. Typically, these rules involve the child being quiet and cooperative for a specified period during time-out. In some cases, extremely disruptive or hyperactive children may fail to comply with the typical procedure. They may refuse to go to time-out or escape from the time-out area before finishing their penalty period. To reduce problems in these cases, children may earn time off their penalty period for good behavior or for complying with the procedure (that is, the length of the original time-out is reduced). Alternatively, when a child refuses to follow the time-out rules, the length of the original time-out may be increased for each rule infraction. In another approach, the child may be removed from the class to serve the time-out elsewhere (for example, in another class or in the principal’s office). Failure to comply with time-out may also be responded to with a penalty or fine in the class token system. For instance, activities, privileges, or tokens may be lost for uncooperative behavior in time-out. One strategy that may be particularly effective for reducing uncooperativeness with time-out involves having children stay after school to serve their time-out when they are not cooperative in following time-out rules during school hours. The use of this procedure, however, depends on having staff members available to supervise after school.

Some teachers may keep children in from recess to serve time-out or to complete their schoolwork when it has not been completed during normal class time. We do not recommend this procedure because children with ADHD need their periodic physical exercise as much as or more than typical children and because research shows that physical exercise can help to reduce subsequent ADHD symptoms for a while.

There are cases when a child’s problem behavior typically increases during time-out. This requires the teacher to intervene or restrain the child to prevent harm to the child, to others, or to property. Alternative procedures to time-out may be needed. Most schools have some guidelines for the types of punishment they permit. Parents may want to ask for copies of these so they can be familiar with what limits the school district may place (or not place!) on these methods.

School Suspension

Suspension from school (usually from 1 to 3 days) is sometimes used as punishment for severe behavior problems, but it should be used with much caution. Many children may find staying at home or in full-day day care more enjoyable than being in school. Suspension is also undesirable when the parents both work and cannot supervise the child when they are at home during suspension, when they may not have the management skills needed to enforce the suspension, or when they are overly punitive or abusive to a child due to the suspension. Given that many parents now work during school hours, it is better for a school to develop an in-school suspension program where students who are suspended for a day or two for misbehavior can go to an alternative location in the school that is under stricter supervision and with work that must be done in order to be returned to the regular classroom.

How to Limit the Effects of Punishment

Despite the overall effectiveness of punishment, some unpleasant side effects may occur if it is used improperly. These unwanted effects include the escalation of the problem behavior, the child’s dislike of the teacher, or (in rare cases) the avoidance of school altogether. Drs. Lee Rosen and Susan O’Leary from Stony Brook University, offer several guidelines to reduce possible adverse side effects:

1. Punishment should be used sparingly. Excessive criticism or other forms of punishment may also make the classroom unpleasant or aversive. Frequent harsh punishment may even increase a child’s defiance. This is especially likely in cases where a teacher mistakenly serves as an aggressive model—that is, the teacher’s use of punishment teaches the child to be aggressive like the teacher.

2. When negative consequences are used, children should be taught and rewarded for alternative appropriate behaviors that are not compatible with the inappropriate ones. This practice will help by teaching the children appropriate skills, as well as by decreasing the potential for the occurrence of other problem behaviors.

3. Punishment involving the removal of a reward or privilege is to be preferred to punishment involving the use of an aversive event, such as isolation or physical punishment. In fact, the use of physical punishment is often limited in schools for ethical and legal reasons.

Getting Results to Last and Carry Over to Other School Situations

Despite the substantial success of behavioral methods in school, there is little evidence that the gains made by children under these programs last once the programs are stopped. Also, the improvements that may occur in one setting where the programs are used (say, reading class) often do not carry over to settings where the programs are not being used (say, math class or recess). This can be very disappointing to both parents and teachers.

One current solution is to use management programs wherever the child’s behavior is a problem, but this approach has practical limits. Most programs won’t be easy to carry out at recess, for example. Instead, withdrawing the management methods gradually—by reducing the frequency of feedback (fading from daily to weekly rewards) and substituting more natural rewards such as praise and regular activities for token rewards—may increase their endurance. One study found that the abrupt removal of punishment, even when a powerful token program was in use, led to a dramatic deterioration in class behavior, but when punishment was removed gradually, high levels of paying attention and hard work were maintained.

One particularly effective way to fade out a management program involves changing the places in school where the programs are in effect on any given day. The child is never quite sure when or where the programs will be used and learns that the best bet in these circumstances is to keep behaving well.

Even though research continues on these issues, the difficulties have not been resolved. Specially arranged treatment programs for children with ADHD simply may be required across most school settings. For now we know these must be kept in place for long periods of time over the course of a child’s education to be helpful. This observation may seem discouraging, but given our view that ADHD is a fairly chronic developmentally disabling condition, it is no surprise.

Having Classmates Help with Behavior Management

The disruptive behavior of children with ADHD often prompts their peers to respond in ways that promote or maintain the problem behavior. On the one hand, classmates may reward such a child’s clowning and silliness with smiles and giggles. On the other hand, they may also retaliate against the child’s teasing or intrusiveness. Either way, the child gets a bad reputation among peers. As discussed previously, using group-based reward programs may be effective in counteracting peer attention for misbehavior by a child with ADHD. However, some studies show that classmates can also intervene directly to produce good behavior in a fellow student with ADHD.

One of the most powerful ways classmates can help is by being encouraged to ignore the disruptive and inappropriate behavior of the child with ADHD. Peers can also increase this child’s appropriate behavior by giving the child praise and positive attention for it. We see this in action during sporting events, when team members cheer and congratulate each other for successful plays, and it can be extended to praising one another for being a good sport, getting a high grade on an exam (or accepting a low grade without a tantrum), contributing to a class discussion, or helping another student. Token programs, in which classmates monitor the behavior of the child with ADHD and give or take away tokens for good or bad behavior, can also be successful as long as they are supervised by a teacher.

Of course, these classmates should usually be rewarded for their own efforts. Otherwise, what’s in it for them? In some cases praise is sufficient, but the teacher can also use tangible rewards or a token program. Rewarding these children not only reinforces their efforts, but also ensures that the program is carried out well.

The use of classmates as “behavior sheriffs” has practical advantages. It provides an alternative to the teacher being compelled to observe everyone all the time, and it may require less time than traditional teacher-mediated programs. It may also serve to improve the behavior of the “sheriffs” and to encourage the transfer of the improved behavior into other situations where the same peers are present. However, programs carried out by classmates are successful only to the extent that these classmates have the ability and interest to learn the methods and to carry them out accurately. The teacher should train and supervise classmates carefully and should not let them get involved in the punishment aspects of any program.

HOME-BASED REWARD PROGRAMS

In a home-based reward program, the teacher sends home an evaluation of how the child with ADHD behaved in school that day and the parents use it to give or take away rewards available at home. This method has been effective in modifying a wide range of problems that children with ADHD have at school. Because of its ease of application and the fact that it involves both the teacher(s) and parents, it is often one of the first interventions you should try.

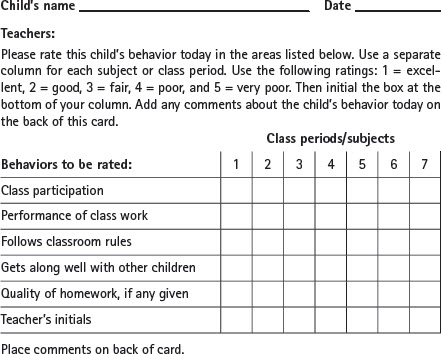

Behavior Report Card

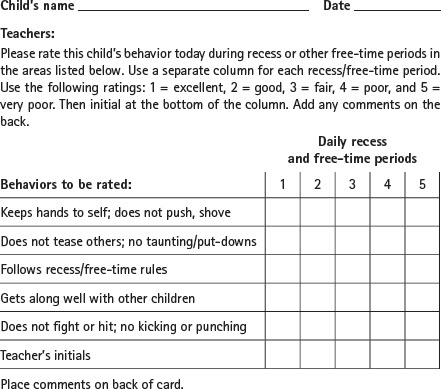

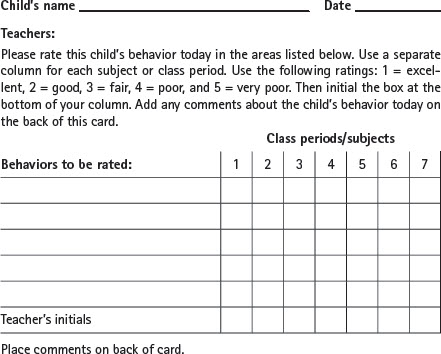

The teacher’s report can consist of either an informal note or a more formal report card. We recommend the use of a behavior report card. The card should show the “target” behaviors that are to be the focus of the program listed on the left side. Across the top should be numbered columns that correspond to each class period at school. The teacher gives a number rating reflecting how well the child did for each of these behaviors for each class period. Examples of daily school behavior report cards are shown in Figures 3, 4, and 5. Figure 3 illustrates a card designed to assist in managing classroom behavioral problems. Figure 4 shows a card designed to help with a child who has behavioral problems during free time, such as recess or lunchtime. And Figure 5 is a blank card that can be tailored to whatever behavioral problems parents and teachers wish to focus on in this type of treatment program. Parents can feel free to photocopy these figures for use with their own children, with permission of the publisher. These teacher reports are typically sent home daily. In some cases, notes are sent home only when a child has met certain goals for behavior or academic work that day. In other cases, a note can be sent home on both “good” and “bad” days. As the child’s behavior improves, the daily reports can be reduced to twice weekly, then weekly, and then twice monthly, finally being phased out altogether.

A variety of home-based programs may be developed and tailored for your child. Some of the behaviors targeted for the program may include both social conduct (sharing, playing well with peers, following rules) and academic performance (completed math or reading assignments). Targeting low academic performance (poor production of work) may be especially effective. These home-based school report cards have resulted in improvements in both academics and social conduct. Examples of behaviors to target include completion of all (or a specified portion) of the work, staying in an assigned seat, following teacher directions, and playing cooperatively with others. Negative behaviors (for example, aggression, destruction, calling out) may also be included as target behaviors to be reduced by the program. In addition to targeting class performance, homework may be included. Children with ADHD often have difficulty remembering to bring home their homework assignments. They may also complete their homework but forget to return the completed work to school the next day. Each of these areas may be targeted in a note-to-home program.

We suggest that you target only four or five behaviors to work on. Start out by focusing on just a few behaviors you wish to change to help maximize your child’s success in the program. When these behaviors are going well, you can add a few more. The daily ratings of each behavior may be global and subjective (for example, “poor,” “fair,” “good”). However, it helps to make them more specific and objective (for example, frequency of each behavior or the number of points earned or lost for each behavior). We recommend including at least one or two positive behaviors that the child is currently doing well with, so that the child will be able to earn some points during the beginning of the program.

Typically children are monitored throughout the school day. However, to be successful with frequent problem behaviors, you may want to have your child rated for only a portion of the school day at first. As the child’s behavior improves, the ratings may be increased gradually to include more periods/subjects. In cases where children attend several different classes taught by different teachers, the program may involve some or all of the teachers, depending on the need for intervention in each class. When more than one teacher is included in the program, a single report card may include space for all teachers to sign. Different report cards may be used for each class and organized in a notebook for children to carry between classes. Again, the cards shown in Figures 3, 4, 5 can be helpful, because they have columns that can be used to rate the child by the same teacher at the end of each subject or by different teachers if more than one is involved.

The success of the program depends on a clear, consistent method for translating teacher reports into consequences at home. Some programs involve rewards alone; others use both positive and negative consequences. Some studies suggest that a combination of positive and negative consequences may be most effective. One advantage of home-based programs is that a wide variety of consequences can be used—praise and positive attention as well as tangible rewards, both daily and weekly.

Overall, home-based reward programs may be even more effective when combined with classroom-based programs, which give the parents frequent feedback, remind parents when to reward a child’s behavior, and forewarn parents when behavior is becoming a problem at school. Furthermore, the type and quality of rewards available in the home are usually far more extensive than those available in the classroom—a factor that may be critical for children with ADHD, who need more powerful rewards. Aside from these benefits, note-to-home programs generally require much less time and effort from your child’s teacher than do classroom-based programs. As a result, teachers who have been unable to start a classroom management program may be far more likely to cooperate with a note-to-home program. Despite the impressive success of note-to-home programs, the effectiveness of such a program depends on accurate evaluation of the child’s behavior by the teacher. It also hinges on the fair and consistent use of consequences at home. In some cases children may attempt to undercut the system by failing to bring home a report. They may forge a teacher’s signature or fail to get certain teacher signatures. To discourage these practices, missing notes or signatures should be treated the same way as a “bad” report (for example, a child fails to earn points or is fined by losing privileges or points). The child may even be grounded for the day (no privileges) for not bringing the note home.

Daily School Behavior Report Card

FIGURE 3. A daily school report card for managing ADHD behavior problems during class time at school, used with a home-based token reward system.

From Barkley, R. A., & Murphy, K. R. (2006). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Clinical Workbook (3rd ed.). Copyright 2006 by The Guilford Press. Reprinted in Taking Charge of ADHD (3rd ed.). Copyright 2013 by The Guilford Press.

Daily Recess and Free-Time Behavior Report Card

FIGURE 4. A daily school report card for managing ADHD behavior problems during free time at school, to be used with a home-based token reward system.

From Barkley, R. A., & Murphy, K. R. (2006). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Clinical Workbook (3rd ed.). Copyright 2006 by The Guilford Press. Reprinted in Taking Charge of ADHD (3rd ed.). Copyright 2013 by The Guilford Press.

Daily School Behavior Report Card

FIGURE 5. A blank daily school report card for managing ADHD behavior problems at school, to be used with a home-based token reward system. The problem areas can be filled in beforehand by parents or teacher(s), so as to focus the card system on whatever specific behavior problems are of concern for a particular child.

From Barkley, R. A., & Murphy, K. R. (2006). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Clinical Workbook (3rd ed.). Copyright 2006 by The Guilford Press. Reprinted in Taking Charge of ADHD (3rd ed.). Copyright 2013 by The Guilford Press.

Some Examples of Note-to-Home Programs

The cards shown in Figures 3, 4, 5 contain five areas of potential problems for children with ADHD. Columns are provided for up to seven different teachers to rate a child in these areas or for one teacher to rate the child many times across the school day. We have found that the more frequent the rating, the more effective is the feedback to the child and the more informative is the program to you. The teacher initials the bottom of the column after rating the child’s performance during that class period, to ensure against forgery. When getting the correct homework assignment home is a problem for a child, the teacher can require the child to copy the homework for that class period on the back of the card before completing the ratings for that period. In this way the teacher merely checks the back of the card for accuracy of copying the assignment and then completes the ratings on the front of the card. For particularly negative ratings, we also encourage teachers to provide a brief explanation. Teachers rate children using a 5-point system (1 = excellent, 2 = good, 3 = fair, 4 = poor, and 5 = very poor).

The child takes a new card to school each day. These can be kept at school and a new card given out each morning, or you can provide the card as your child leaves for school, whichever is most likely to be done consistently. Upon returning home, you should immediately inspect the card, discuss the positive ratings first with your child, and then proceed to a neutral, business-like (not angry!) discussion with your child about any negative marks and the reason for them. Your child should then be asked to formulate a plan for how to avoid getting the negative mark tomorrow. You are to remind your child of this plan the next morning before your child departs for school. You should then award your child points for each rating on the card and deduct points for each negative mark. For instance, a young elementary-age child may receive five chips for a 1, three chips for a 2, and one chip for a 3, while being fined three chips for a 4 and five chips for a 5 on the card. For older children, the scale might be 25, 15, 5, –15, and –25 points, respectively, for marks 1 to 5 on the card. The chips or points are then added up, the fines are subtracted, and the child may then spend what is left on privileges from the home reward menu.

As these cards illustrate, virtually any child behavior can be the target for treatment.

TRAINING CHILDREN WITH ADHD TO THINK ALOUD, THINK AHEAD

Many treatment programs for children with ADHD have used methods that teach the children to talk to themselves out loud, give themselves instructions on what they should be doing, and reward themselves verbally for how they did. These methods are often called cognitive behavior modification, self-instruction, or self-control programs.

One such program involves teaching children a set of self-directed instructions they should follow when they are doing their work. Self-instructions include (1) having the children say out loud to themselves what the task or problem is they have been assigned to do; (2) saying what plan of attack or strategy they will use to approach the problem; (3) keeping their attention on the task; (4) describing their plan as they follow it through to completion; and (5) telling themselves how they think they have done. This may also include giving themselves a reward, such as a point or token, for getting the problem correct. In the case of an incorrect answer, the children are taught to say something encouraging to themselves, such as “Next time I’ll do better if I slow down.”

At first an adult trainer typically shows a child how to do the self-instruction while performing the work. The child then performs the same task while the trainer provides the instructions. Next, the child performs the task, repeating the self-instructions aloud. This talking aloud is then faded to silent speech (or whispering). Rewards are typically provided to the child for following the procedure as well as for selecting the correct solutions. Children can use these methods for virtually any type of schoolwork or even on their homework.

Despite the apparent promise of these methods for children with ADHD, who are obviously impaired in self-control, many research studies have failed to show strongly positive results. In general, the results of these programs are modest or do not seem to last once the program is stopped. The results also do not carry over into other classes, places, or situations where the methods are not being taught or where the children are not rewarded for their use.

For these reasons, we strongly recommend that this approach never be the only program used, that it not be the principal approach in the child’s classroom, and that it be used in the classroom by the teacher—not taught by someone else outside the classroom, where it is not likely to carry over back into the classroom.

MANAGING THE ACADEMIC PROBLEMS OF ADOLESCENTS WITH ADHD

All of the recommendations made so far apply as much to adolescents with ADHD as to younger children. However, the changes that take place in high school—the greater number of teachers involved with each student, the shorter class periods, the increased emphasis on individual student responsibility, and the frequent changes in class schedules from day to day—are likely to result in a dramatic drop in educational performance as many children with ADHD enter high school. This is compounded by the fact that there is little or no accountability of teachers for a particular student at this level of education. Only when a teen’s misbehavior becomes sufficiently serious to attract attention, or academic deficiencies are grossly apparent, will someone take notice. Usually the response of the school is punitive rather than constructive.

“You say that my daughter needs more structure and supervision in high school, but the principal says this is just coddling her, that if we keep doing this she will never learn self-discipline or self-management. She says it is time for Sarah to sink or swim, to experience the natural consequences of her mistakes and disorganization. Is that true?”

It is very easy for average adolescents with ADHD to fall through the cracks at this stage unless they have been involved with the special educational system before entering high school. Those who have will have been “flagged” as in need of continuing special attention. But the others are likely to be viewed merely as lazy and irresponsible. It is at this age level that educational performance becomes the most common reason adolescents with ADHD are referred for professional help.

“Our son won’t go for extra help from his teachers. He says he doesn’t need it, that he can bring up his grades on his own. He refuses the medication you recommended too. What can we do?”

Dealing with large schools at this age level can be frustrating for parents and for a teenager with ADHD alike. Even the most interested teacher may have difficulties mustering sufficient motivation among colleagues to be of help and keep the adolescent out of trouble at school. Here are a few ideas that may help:

1. If your teenager is failing or doing poorly and has never had special education, immediately request a special education evaluation if one has not been done before or within the past 3 years. Federal law (the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act) requires a reevaluation every 3 years that a child is in special education. Special educational services will not be forthcoming until this evaluation is completed, and this can take up to 90 days or longer in some districts. The sooner it is initiated, the better.

2. Adolescents with ADHD usually require counseling about the nature of their disability. Although many have already been told that they are “hyperactive” or have ADHD, a lot of them have not come to accept that they actually have a disability. Counseling can help these teenagers learn to accept their limitations and find ways to prevent their disability from creating significant problems. Such counseling is difficult, requiring sensitivity to the adolescents’ desire to be independent and to form their own opinions of themselves and their world. It often takes more than a single session to succeed, but patience and persistence can pay off. Find a counselor or other professional who knows about ADHD and ask this professional to spend a few sessions counseling your teen about the disorder. Your teen is more likely to listen to the professional than to you.

3. Counsel the adolescent on the advantages of returning to medication if it has been used successfully in the past. Medication can improve school performance and help the teen obtain those special privileges at home that may be granted as a result of such improved performance (use of the car, later curfew, higher allowance, etc.). Adolescents who are concerned about others learning that they are on medication should be reassured that only they, their parents, and the physician will be aware of this. Be prepared for resistance to the idea of medication and consider setting up a behavior contract by which the teen earns certain rewards (money, extra free time, etc.) for taking the medication daily.

4. Schedule a team meeting at the beginning of each academic year, and more often as needed, at the teenager’s school. This meeting should be attended by the teachers, school psychologist, guidance counselor, principal, parents, and the adolescent with ADHD. Take with you a handout describing ADHD to give to each participant. If you think it is helpful, ask a professional to go along with you to give advice. Briefly review the nature of the adolescent’s disorder and the need for close teamwork among the school, parents, and teen if the teen’s academic performance is to be improved. Get the teachers to describe the current strengths and problems of the teen in their classes, and to make suggestions as to how they think they can help with the problem. Some of these might include being available after school a few days each week for extra assistance; reducing the length of written homework assignments; allowing the teen to provide oral means of demonstrating that knowledge has been acquired, rather than relying on just written, timed test grades; and developing a subtle reminder system to alert the teen when she is not paying attention in class without drawing the whole class’s attention to the fact.

At this conference, the teen then makes a public commitment to doing specific things to improve school performance. The team should agree to meet again in 1 month to evaluate the success of the plans and troubleshoot any problem areas. Future meetings may need to be scheduled depending on the success of the program to date. Meetings should be scheduled at least twice a year to monitor progress and keep the school attentive to the needs of this teen. The adolescent always attends these meetings.

5. Introduce a daily home–school report card as described earlier. These are often more critical for teens than for any other age group to provide daily feedback. Also, a home point system must be set up that includes a variety of desired privileges that the teen can purchase with the points earned at school. Points can also be set aside in a savings book to work toward longer term rewards. Remember, however, that it is the daily, short-term privileges and not these longer term rewards that give the program its motivational power. So don’t overweight the reward menu with long-term rewards.

Once the adolescent is able to go for 3 weeks or so with no 4’s or 5’s (negative ratings) on the card, the card is cut back to once or twice a week. After a month of satisfactory ratings, the card can either be faded out or reduced to a monthly rating. The adolescent is then told that if word is received that grades are slipping, the card system will be reinstated.

6. Get the school to provide a second set of books to you, even it means putting up a small deposit, so that homework can be done even if the teen leaves a book at school. These books can also be helpful to any tutor you’ve hired.

7. Get one of the teen’s teachers, the homeroom teacher, a guidance counselor, or even a learning disabilities teacher to serve as the “coach,” “mentor,” or “case manager.” This person’s role is to meet briefly with the teen three times a day for just a few minutes to help keep him organized. The teen can stop at this person’s office at the start of school. At this time, the manager checks to see that the teen has all the homework and books needed for the morning’s classes. If a behavior report card is being used with this teen, it can be given to the teen at this time. At lunch, the teen checks in again with the manager, who checks that the teen has copied all necessary assignments from the morning classes, to help the teen select the books needed for the afternoon classes, and then to see that the student has the assignments that are to be turned in that day for these afternoon classes. If the behavior report card is being used, it can be reviewed by the “coach” at this time and discussed with the teen. At the end of school, the teen checks in again with the manager to see that he has all assignments and books needed for homework. Again, the behavior report card can be reviewed by the coach and discussed with the teen before sending it home for further review by parents and conversion into the home point system. Each visit takes no more than 3–5 minutes, but, interspersed as they are throughout the school day, these visits can be of great assistance to organizing the teen’s schoolwork.

8. If you feel you can’t help with homework, then consider a private tutor as discussed above or have your teenager attend any extra help periods that the school requires the teachers to hold at the end of the school day. The student can go to one extra help period per week for each course. And don’t forget about the Internet self-taught courses at Khan Academy (www.khanacademy.org) discussed above that can be as beneficial for teens as for children with ADHD.

9. Set up a special time each week to do something alone with your teen that is mutually pleasurable. This provides opportunities for parent–teen interactions that are not work-oriented, school-related, or fraught with the tensions that work-oriented activities can often involve for teens with ADHD. These outings can contribute to keeping your relationship with your teen positive. They can also counterbalance the conflicts that school performance demands frequently bring to families. You’ll find more on making sure you don’t stress schoolwork at the expense of your relationship with your child in the next chapter.