Barn raisings are for us what the World Series is for the non-Amish.

—Amish farmer

The rites of redemption in Amish society are enmeshed in a network of social activities that knit the community together. Spontaneous visiting and informal gatherings create solidarity and generate social capital across the settlement. Somewhat like its financial equivalent, social capital provides a collective pool of resources that contribute to the well-being of the community and benefit individual members.1 The cultural values and social structures of Amish society generate many resources that bolster the common good. An Amishman described it this way: “There’s much caring and sharing in times of need, helping together to raise barns and in funeral and wedding arrangements, to plant and harvest crops if a farmer is laid up.... Much of this caring is done at a moment’s notice, when the neighbors see the crops need to be tended.”2

The traditional Amish barn raising provides a good example of how cultural and social capital are mobilized for a special need. When a barn goes up in flames, everyone in the Amish community knows exactly what will happen in the next three days, without consulting a book or looking at a Web site. Neighbors will immediately drop their work and help with the cleanup while the debris still smolders. On the next day, a hundred or more people will arrive and raise a new barn in a matter of hours. All the labor is donated. The recovery effort automatically swings into action without lengthy discussions with insurance adjustors, lawyers, and contractors. It happens spontaneously because the barn-raising habit is so tightly woven into the texture of Amish life. Everyone freely donates their time because their house or shop may be next. This simple but powerful tradition is embedded in the cultural capital—the values of mutual obligation, duty, and trust that are simply taken for granted in Amish society.

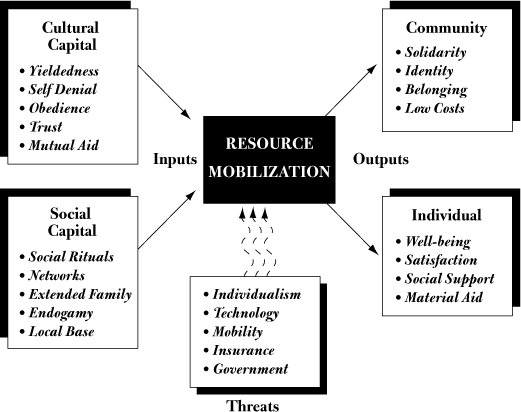

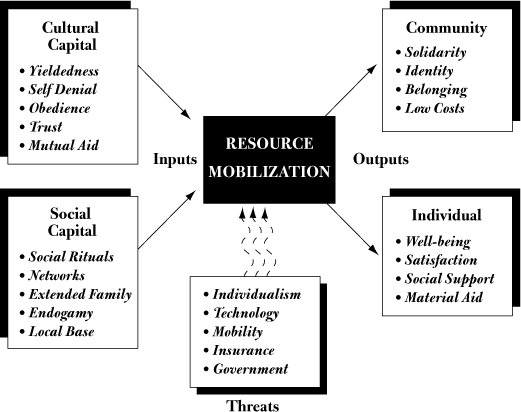

A barn raising is perhaps the most dramatic example of how the pool of social capital is mobilized in Amish society. Social capital resources include strong networks of face-to-face relationships, extended family, and longstanding traditions and rituals that support them. Both cultural values and social structures provide the raw materials, so to speak, to mobilize the resources to raise a barn as shown in Figure 6.1. Many social activities in the Amish life cycle generate and expend social capital from birth to death for the well-being of the community. And many of the decisions the elders have made over the years, decisions that may appear silly to outsiders, were in fact attempts to preserve the social capital that energizes the life of the community.

FIGURE 6.1 Cultural and Social Capital Resources

Strong social networks make it easier to generate and store social capital. An Amish child is born into a dense network of extended family relations that will surround and support her for the rest of her life. This web of siblings, cousins, aunts, and uncles—as many as a hundred or more people who are directly related to the child—provide a ready-made system of support that is already in place when the infant arrives. The newborn child does not need to develop support groups or join interest groups because an entire system awaits its arrival. The child inherits these social supports at birth and later reproduces them as an adult.

Most Amish children are born at home under the supervision of a trained non-Amish midwife. Sometimes the first child is born at a hospital, but later children typically greet the world at home. A birthing is a family affair. Increasingly, fathers attend the delivery and siblings excitedly await the arrival in an adjoining room. A physician who cares for Amish patients noted that whenever a newborn arrives, one or two adult women suddenly appear in the household. These mothers, older sisters, or aunts are experienced: they know the secrets—the wisdom of the culture. Instead of reading books on birthing, they tap the wisdom, the cultural capital afloat in the networks around them. And as children grow up, there is ample help to raise them. A young mother with two children explained that whenever she needs a babysitter, “I can just drop them off at one of my two sisters and three cousins that live within a half-mile of here.”

Unlike children who are socialized to become independent and successful in a competitive world, the Amish child is taught meekness, humility, and obedience. The child must master these virtues of Gelassenheit in order to prepare for a successful Amish life. Child-rearing practices, school curriculum, and apprenticeship in home and shop immerse children in Amish values and prepare them for adulthood. Most basic of all, the child learns to be obedient to authority—whether embodied in parents, teachers, or leaders. Such obedience is the key to shaping members who will support the habits and sentiments that generate community.

Amish youth anticipate their sixteenth birthday with great excitement. This is the moment when they can join a youth group and begin running around (rumspringa) with their friends on weekends. Rumspringa continues until they are married, typically at between nineteen and twenty-two years of age.3 During this liminal period they are betwixt and between the authority of their parents and the thumb of the church because they are not baptized. Some are baptized a year or so before they marry and others shortly before marriage. The friendships and networks that develop during rumspringa form a lifelong web of social ties across the community.

About twenty-seven youth groups, called “gangs,” ranging in size from fifty to a hundred and fifty members, crisscross the Lancaster settlement. By the age of ten, an Amish child will be able to name some of the groups—Bluebirds, Canaries, Pine Cones, Drifters, Shotguns, Rockys, and Quakers—and even describe some of their activities. Youth are free to join the gang of their choice. Young people from the same church district or family may join different groups. The gangs become the primary social world for teens before they marry, but the groups vary considerably in their conformity to traditional Amish values.

Some groups are fairly docile, but others engage in boisterous behavior that occasionally makes newspaper headlines. The reputation of the various gangs signals how Plain or rebellious a young person likely will be. The groups engage in various recreational and social activities—volleyball, swimming, ice skating, roller skating, singing, picnics, parties, and dances. For many of these activities, the more rowdy boys “dress around,” that is, shed their sectarian garb. Hatless, wearing styled hair and store-bought jackets, they may “pass” as typical youth in a bar or movie theater. Young men in some groups will have fancy reflective tape on their buggies and perhaps a hidden radio or CD player inside.

Sunday afternoon and evening is the traditional time for youth gatherings. Members of Plainer gangs will typically stay home on a Saturday night unless they are dating. The faster gangs, by contrast, may sponsor a “band hop,” attend movies, or play cards on a Saturday night. Members of the more rambunctious groups drive cars and sponsor dances, called “band hops,” featuring Amish bands with electric guitars and kegs of beer. Wilder parties often involve the use and abuse of alcohol. In one case, alcohol abuse was so consistent and flagrant that public officials wrote to church leaders asking for help to curb it.4 Youth are occasionally arrested for driving cars and buggies under the influence of alcohol.

Unlike the more sensational gangs, many groups uphold traditional Amish values—driving horses and carriages, and drinking sodas or hot chocolate. The Plainer groups focus more on group games and outdoor activities. While the faster gangs are more peer oriented, the Plainer ones are more adult-centered, with parents participating in some of their activities.5 After two nationally publicized drug arrests in 1998, some parents established several fairly Plain youth groups that have strict standards forbidding worldly clothing, cars, alcohol, and drugs. The gatherings of these gangs end earlier in the evening and have more parental involvement.

The hundred or so members of a gang will gather at a member’s farmstead on a Sunday afternoon to play volleyball or softball before a sumptuous supper prepared by some of the parents. Following the supper, their caravan of buggies will travel to another home for a singing that begins about 7:30 p.m. and continues until 10:00 P.M., followed by socializing indoors and out until midnight or later.

A dating relationship may begin when a fellow offers to take a young woman home in his buggy. Depending on how far they must travel, some lads may not return home until early dawn. One parent noted, “The groups are intermingled throughout the settlement so that some girl-hunting lads may travel twenty-five to thirty miles to win the lady of his choice. Some do it pony express style, using two horses.”6 Youth often date several persons before finding their lifelong partner.

The cohort of twelve to twenty youth that join a gang in a particular year are known as a “Buddy Bunch.” These subgroups within the gang sometimes have their own name. The primary peer groups for teens, Buddy Bunches often continue meeting throughout their lives. Within the Buddy Bunch, a teen will often have a “sidekick,” a best friend with whom to share secrets. Interaction with the Buddy Bunch slows somewhat when a couple begins serious dating, but sidekicks and Buddy Bunch members will often join the church at the same time and remain friends for life.

In some ways the struggles of Amish families are similar to contemporary ones. Parents worry about which groups their teens will join because they know that one group may invite temptation, whereas another will reinforce parental teaching. Youth inclined to rebel will deliberately join a more rowdy gang, and those with a docile heart will seek more conservative peers. But even most of the fellows who succumb to cars, alcohol, and movies eventually put away their foolishness and return to the fold prior to marriage. To enjoy the delights of the world as long as possible, some young men will delay baptism until the fall when they are married. In actuality, their decision to join the church is usually made in the late spring because candidates must attend instruction classes over the summer.

A Buddy Bunch chats together before a Sunday evening singing.

One elder thinks the crisscrossing youth groups help to unify the settlement by creating a web of extended family ties that binds the whole community together beyond local districts. In any event, the social ties that form in the rumspringa years lay a foundation for long-term networks of solidarity and support.

Weddings are held on Tuesdays and Thursdays in November at the end of the harvest season. As many as a dozen weddings may be held on the same day, and 180 may take place across the settlement in a wedding season. An individual may receive invitations to four or five weddings on the same day. The daylong affairs are held at the home of the bride and often involve 300 to 400 guests.7

The guests begin arriving at 7:00 A.M., and some may linger until midnight. The wedding ceremony is part of a three-and-a-half-hour service similar to Sunday worship. The service itself is a sober and plain event with no candles, flowers, veils, rings, tuxedos, or special music. Two couples who accompany the bride and groom constitute the wedding party. The festivities begin after the formal service. A hot lunch is eaten in several shifts, and a smaller meal is served again in the evening. Visiting, games, and singing fill the afternoon and evening hours until the last guests depart.

To orchestrate such a large gathering in a private home or shop without a catering service requires an enormous outpouring of free labor. The bride’s mother and family take the lead role in planning, but they often have someone else coordinate the events of the day itself. Neighbors in the local church district provide food and help to prepare the property and assist in various roles throughout the day—as cooks, ushers, waiters, dishwashers, table setters, and hostlers to care for the horses. This generous outpouring of goodwill celebrates one of the happiest moments in Amish life. An older couple, returning from a bankruptcy hearing for a business they sold, belatedly joined the afternoon singing and festivities of a wedding. Struck by the contrast, they marveled, “How good we have it! The outside world has no idea what they’re missing.”

The newlyweds typically spend their first night at the bride’s home and help to clean up the house the next day. Traditionally, the bride and groom live with their parents for several months until they set up their household in the spring when farm families typically move. Instead of a honeymoon, the bride and groom spend weekends with different relatives throughout the winter. During these visits the couples receive their wedding gifts and cement their relationships with the new members of their extended family. With the wedding behind them, they are now considered adults and expected to fully participate in the life of the community. In the summer following the wedding, the groom’s parents hold an infare, a celebration to thank the bride’s family and all the friends and neighbors who helped with the wedding—a way of replenishing the goodwill—the social capital—in the Amish reservoir.

A dating couple in their open courting buggy.

The Amish observe a different cultural calendar. Although they do not formally celebrate public holidays—Washington’s Birthday, Martin Luther King Day, Memorial Day, Fourth of July, or Labor Day—they do recognize Thanksgiving and New Year’s Day. They also observe sacred days that stretch back to their roots in Switzerland. In addition to Easter and Christmas, they celebrate Good Friday, Easter Monday, Pentecost Monday (Whit Monday), and a second day of Christmas on 26 December. Good Friday in the spring and St. Michael’s Day in the fall are days of fasting and prayer to prepare for holy communion.

Second Christmas, Easter Monday, Pentecost Monday, and Ascension Day are festive times for visiting and relaxing. Amish businesses close on these days, and people typically dress up as they visit with friends, families, or Buddy Groups. Youth groups will plan special outings with volleyball and a meal with their “supper crowd.” Some groups may plan a van or bus trip to another settlement in Pennsylvania on one of these holidays. Fishing is a favorite activity on Ascension Day, which comes on a Thursday, forty days after Easter. One Amish person described Ascension Day this way: “The day is for visiting and starts early for young and old alike. Uncles, cousins, and families congregate. Youth groups plan outings—softball and volleyball. Charter buses take youth and married folks to other communities 150 miles away to visit, relax, and ponder the philosophies of Amish life. With about 22,000 Amish here in Lancaster, about half of them are on the move.... If 11,000 folks move about in six per buggy that’s 1,800 horses clip clopping down the roads, so drive carefully those of you driving Detroit and imported vehicles. We appreciate it.”8

Visiting is the national sport of Amish society. It is the social glue that bonds the community together through informal ties of trust and respect. Much of the visiting occurs spontaneously when family and friends drop in unannounced for a visit. Other visiting takes place in dozens of informal gatherings, reunions, quilting parties, frolics, and picnics. Still other visiting occurs in more formal settings, after church meals, at weddings, and funerals. Some older folks complain that some young married couples are even getting together in their “off Sunday” for brunch instead of worshiping in an adjoining district or spending a worshipful day at home. Unlike more modern forms of one-on-one visiting, Amish visiting is virtually always collective, with five or six persons, if not a dozen, in a circle.

To the casual observer, visiting may appear as a waste of time, but in fact it is an important means of renewing the networks of social capital throughout the community. These relationships, rejuvenated through visiting, strengthen the informal bonds that link the community together in joy and suffering. Interpersonal relationships in Amish society are enmeshed in a concrete social context. Unlike the context-free relationships of cyberspace, Amish people interact with others in a high-context culture. They know more than just the other person’s name and e-mail address. They know the full social context surrounding the person—their parents and grandparents, their church district and ministers, their occupation and hobbies, their stature within the community—as well as their temperament. These are deeply embedded, highly contextualized relationships that are quite different from the multitude of transitory ties in modern society and cyberspace. Relationships in Amish society are full-bodied, high-context, durable connections that stretch over a lifetime.9

Unlike modern societies that segregate work and play, the Amish often blend them together. Banter and humor abound as work crews clean up after a flood. Staging a wedding for 350 guests involves a lot of hard work as well as fun. The growth of the settlement has expanded options for social involvements. “We have many more social activities today,” said one woman. “We used to have a more quiet pace of life, but now there’s so many activities. We don’t go and play tennis, but we have many more visiting activities.”

A great deal of visiting happens with frolics—typically one-day gatherings that blend work and fellowship in a variety of activities. Twenty-five people might come together to help finish and clean a new house or prepare a school and play yard for a new school year. Depending on the task, men and women may attend the frolic together or the women may go alone. Some activities fall along gender lines. A quilting party or Christmas cookie bake is for the women. Traditional farm life made it easy to participate in frolics. More recently, with more people involved in business and milking larger herds, schedules are less pliable. One frolic coordinator complained, “Today some people don’t arrive until the morning coffee break, and then they have to leave at 3:00 p.m. to begin their milking.”

A unique family tradition is “Sisters Day.” The sisters in a family, which might include five or six women, may meet monthly for fellowship and work in one of their homes. Sometimes they preserve vegetables, quilt, bake, or clean. “Oftentimes,” said one woman, “we take our sewing and just talk while the children play.” Some sisters sew comforters that are distributed to refugees in other countries through the Mennonite Central Committee.

Buddy Groups, extending from running-around days, often continue meeting through adulthood as well. The women may get together once a month for a small frolic or a quilting party much like a Sisters Day. Several times throughout the year the couples may gather for a picnic, a Christmas singing, or to sing for older folks who are homebound. One leader complained that the women are always “going away too much. They’re just not home enough.”

If the women are going away too much, the men are just as guilty. Especially in the late winter and early spring, men can often be found at auctions. A favorite place to visit with friends and neighbors, the farm auction also mingles work and play. One might have to wait all day to bid on a corn binder or drill press to get a “good buy.” Yet throughout the day of waiting, there is incessant visiting, fellowship, food, the excitement of endless bidding, and the auctioneer’s sing-song call. Amish and Old Order Mennonite youth, on opposing teams, often play corner ball in barnyards before cheering crowds of youth and adults. The longstanding auction tradition, the English equivalent of a parade or fair, provides fun and fellowship in the context of making a living.

Clusters of men often go hunting and deep sea fishing together. In addition to local small game hunting, many go deer hunting for several days in central or northern Pennsylvania. In fact, it has become popular for some groups to buy an old farmhouse upstate and convert it into a hunting lodge. Fishing in the Chesapeake Bay as well as deep sea fishing are also favorite sports. A few Amish men were tempted by golf in the 1990s, but that ended with a decree against the sport in 1997.

A lunch break during a quilting frolic.

In recent years many more couples are taking trips for a week or two out of state. Two or three couples will hire a van and driver to visit Amish settlements, national parks, or historic sites in other states. Whether fishing, frolicking, or traveling out of state, the Amish are always doing it in groups, visiting and chatting as they go. The visiting mingles moments of work and play. Some of the elders frown on the growing number of trips to faraway places and worry that they eventually will lead to costly vacations and worldly entanglements away from watchful eyes.

A variety of informal support groups have emerged in recent years that revolve around special interests. Some of these are based in Lancaster County; others stretch across the nation. They range from annual gatherings of occupational clusters to support groups for medical concerns. Still others are chatty letters that circulate within a “circle” of family and special friends.

As more Amish moved into nonfarm occupations in the last quarter of the twentieth century, special occupational groupings also emerged. These Amish versions of professional associations, often called “reunions,” are a favorite time to meet old friends from across the country. They also provide opportunities to share expertise and knowledge about tools, products, and markets—to expand the pool of social capital related to quilting or cabinetry. Since 1981 Amish woodworkers from across the country have gathered for a get-together. Several hundred woodworkers gather to reminisce and to share the latest developments in cabinetry, millwork, and furniture making. The harness makers, machine shop operators, wooden shed builders, and quilters have similar reunions as well. A harness makers’ get-together attracted some 525 people who devoured six hundred halves of chicken, eleven gallons of baked beans, eighteen dozen dinner rolls, sixty pies, and forty gallons of drink. “It got pretty hectic,” said the coordinator, “but we had a lot of fun.”10

Other gatherings focus on medical concerns. Beginning in 1963 in Ohio, individuals with various disabilities began to gather for support in what became known as the “Annual Handicap Gathering.” The reunion rotates around the country and includes some one hundred participants from Lancaster County with cerebral palsy, polio, blindness, dwarfness, multiple sclerosis, and deafness among other disabilities. The gathering provides emotional support as well as information about sources of medical care and equipment. Some Lancaster Amish also participate in the People’s Helpers, an informal network of people assisting persons afflicted with mental illness and depression.

Another form of support for individuals with special interests or needs is the old-fashioned circle letter, where each participant adds their letter to a packet of letters that circulate within a circle of friends. Letter writing is not a lost art among the Amish. Without easy access to telephones or e-mail, the circle letter provides an important source of information and affirmation for persons with similar afflictions. Examples of “circles” include couples without children, persons who have had open heart surgery, parents of children killed in accidents, individuals with a special illness (e.g., muscular dystrophy). Circle letters also rotate among persons with similar circumstances—ministers ordained in the same fall or spring, parents of twins, parents of all boys or all girls, to name but a few examples. In addition, circle letters rotate among relatives or members of Buddy Bunches who have moved away. The many circle letters help to bond the community together.

A more public form of bonding occurs among readers who follow the endless stories of local scribes who write for Die Botschaft and The Budget, Amish weekly newspapers, and for The Diary, a monthly magazine. Accounts of local happenings—church services, accidents, visiting, harvesting, travel, medical problems, and much more—are shared in these publications for Amish audiences across the country. The reunions, circle letters, and newspapers not only disburse information, they also build solidarity and confirm identity in the Amish community.

Mutual aid runs deep in the Amish soul. Church membership carries responsibility to care for the material and social needs of fellow members. An Amish farmer in another state summarized the assumptions about mutual responsibility this way: “When I am plowing in the spring, I can often see five or six other teams in nearby fields, and I know if I was sick they would all be here plowing my field.”11 When disaster strikes in the form of illness, flood, or fire, the community rallies quickly to help the family in need.

The barn raising after a fire is the classic symbol of mutual aid. In a matter of eight hours, more than a hundred men will erect a new barn, and dozens of women will prepare the food that sustains them. Under the quiet directions of a wise foreman, the complicated task flows smoothly, seemingly almost without effort.

An Amishman described it this way:

There isn’t a crane poking its long boom skyward, hook dangling. There are no white-hatted foremen dashing about with squawking radios. Now watch as, just for the last 500 years, a forty-six foot long line of straw hatted men, facing east, bend down. Forty-six feet of rear ends face westward, with all hands on the top timber of the assembled frame. All are ready to push it skyward. The moment is dramatic, everyone is quiet as several late comers rush up the barn hill to help. Reuben says, “Take her up”—not a holler, but a positive command—in a voice filled with experience. With some minor grunts the ponderous frame moves up, hands outstretched.12

The observer also noted that over the years a few things have been added—porta-potties, colorful coolers of drink, and battery-operated hand drills, for example.

Describing the clamor as dozens of men gather around a wagon loaded with coffee, hot chocolate, and cookies, one participant said, “There’s a lot of visiting going on here. There are cousins, and friends from other settlements here who haven’t seen each other for years.” By 4:00 p.m. the structure is secure and most of the tin roof and siding is finished. The barn raising not only addresses a member’s material need but also symbolizes the enormous collective resources of the community. Said one Amishman, “Barn raisings are for us what the World Series is for the non-Amish.”

Although the barn raising is the traditional symbol of mutual care, many other forms of mutual aid flourish, as well. As many Amish moved into nonfarm jobs and as the community has interacted more closely with the outside world, new patterns of aid have emerged. Because of their belief that members of the church should be accountable to and responsible for each other, leaders have strongly discouraged commercial insurance, which would undercut aid within the community and drain away the precious social capital.

A variety of informal aid programs have developed within the church to assist with special needs related to fire, storm, health care, liability, and product liability. Although some of these programs require an annual premium, most of them gather special collections within the community as major needs arise. For example, a collection may be taken to assist a farmer faced with excessive liability charges for selling spoiled milk or a family faced with an overwhelming medical bill. Adjoining church districts also help each other as needs arise. As noted in Chapter 4, the remarkable feature of all these aid programs is their spontaneous response to need without bureaucratic red tape, formal offices, or paid employees. Unlike commercial forms of insurance, transaction costs and administrative overhead are virtually nil.

The community gathers and quickly erects a new barn after a fire.

Auctions have also been used in recent years to help members with special needs. Known as “benefit auctions,” these sales of crafts, quilts, food, and barbecued chicken help families with excessive medical bills or a paraplegic injured in an accident. An annual benefit auction supports the Clinic for Special Children that provides medical care for Amish and Old Order Mennonite children. From frolics to benefit auctions, the community surrounds its members with care and in the process rejuvenates its pool of goodwill. In so doing, it distinguishes itself from the broader society, where needy individuals often have to haggle with lawyers and insurance providers to solve their problems.

The spirit of caring and sharing does not stop at the borders of Amish society. Although the Amish have historically emphasized separation from the world and shunned worldly involvements, they also extend a helping hand to those beyond their fold. By supporting local fire companies, benefit auctions, the Mennonite Central Committee, Mennonite Disaster Service, and Christian Aid Ministries, Amish care extends beyond the confines of their ethnic community.

Although the Amish typically frown on civic involvement, they have readily joined local fire companies. Indeed, in some communities as many as 75 percent of the members of local firefighters are Amish. In some townships they may own the bulk of the farms and homes protected by the fire companies. Although they don’t drive the fire trucks, they do drop their work at a beeper’s notice and scramble to fight the fires.

Many of the fire companies have benefit auctions, sometimes called “Mud Sales” because thousands of people walking on soggy fields in March can quickly turn grass into mud. The Amish donate merchandise and labor for these sales, which attract thousands of outsiders. Many people drive from eastern seaboard cities to bid on quilts, buy some shoofly pie, and witness the Amish in action. Proceeds from such a sale may generate several hundred thousand dollars. The Amish also support disaster relief auctions sponsored by the Mennonite Central Committee to aid international refugees. In addition, they support an auction for the Light House, a local rehabilitation center, and the Haiti Benefit auction for the needy of Haiti. Quilts, lovely furniture, crafts, construction materials, and farm equipment are among the many valuable items the Amish donate to these auctions as well as their labor.

As members of the larger Anabaptist family, the Amish also aid international relief and service projects organized by the Mennonite Central Committee, an international agency with headquarters in Akron, north of the city of Lancaster. One year some 1,200 Amish, in a four-day period, participated in a meat canning project for refugees in Bosnia. A mobile canner moves from area to area, utilizing local labor and donated beef. Sometimes the Amish purchase the beef and then provide the labor for canning it. “We could just buy the meat and send it there,” said one bishop, “but there’s much more satisfaction in helping to do something directly.”

Some Amish women piece comforters or sew other clothing that is donated to the Mennonite Central Committee for distribution to refugees. Many church districts send volunteers to sort and pack clothing at the Mennonite Central Committee’s warehouse in Akron. In a typical year 2,000 members from 125 church districts volunteer thousands of hours at the warehouse quilting, preparing health kits, and packing clothing to be shipped abroad for victims of disaster.

The Amish have also been active participants in Mennonite Disaster Service, a national agency that responds in Red Cross fashion to disasters in the wake of hurricanes, tornadoes, and floods. Amish crews travel by van and bus to work sites, where they clean up debris and rebuild homes for a day or week at a time.

The Amish have assisted with cleanup and reconstruction related to Hurricane Camille in 1969 and Hugo in 1989, as well as tornadoes that struck in Alabama in 1974 and Somerset, Pennsylvania, in 1998. They also contribute to “hay drives” and “corn drives” in which hay and corn are donated to drought-stricken farmers in other parts of the country or world. In addition they donate heifers to a “Heifer Relief Sale,” whose proceeds benefit refugees around the world.

In all of these ways, the Amish extend a hand of friendship and care beyond their ethnic borders, and in the process, they are replenishing their own pool of social capital. For whether it is preparing for auctions, quilting for relief, packing clothes for the needy, or building homes for the homeless, they are doing it together—chattering away, telling stories, building community. This pattern of civic service and philanthropy is much different from the lone volunteer who extends a hand on a civic project or the philanthropist who writes a check in isolation. As they serve the needy, the Amish also build community.

Members draw their final check from their social capital account at death, as the community surrounds the bereaved with care. A funeral director observed that the Amish accept death in graceful ways.13 With the elderly living at home, the gradual loss of health prepares family members for the final passage. The community springs into action at word of a death. Family and friends in the local church district assume barn and household chores, freeing the immediate family. Well-established funeral rituals unburden the family from facing worrisome choices. Three couples are appointed to extend invitations and supervise funeral arrangements—food preparation, seating arrangements for three to four hundred people, and the coordination of a large number of horses and carriages.14

A non-Amish undertaker moves the body to a funeral home for embalming. The body—without cosmetic enhancements—returns to the home in a simple hardwood coffin within five to six hours. Family members of the same sex dress the body in white garments that symbolize the final passage into a new and better life beyond. Women often are garbed in the white cape and apron worn at their wedding.

Friends and relatives visit the family and view the body in a room on the first floor of the home during two days prior to the funeral. Said one person, “People come and visit together—it’s almost a social affair.” They stay awhile and visit, with as many as one hundred in a room. Meanwhile, community members dig the grave by hand in a nearby family cemetery as others oversee the daily chores of the bereaved. Several hundred guests attend the funeral in a barn or home, typically on the morning of the third day after the death. During the simple hour-and-a-half-long service, ministers read hymns and Scripture, offer prayers, and preach a sermon. Singing and eulogies are missing, and there are no flowers, burial tents, or sculpted monuments.

The hearse, a large black carriage pulled by horses, leads a long procession of carriages to the burial ground on the edge of a farm. A brief viewing and a graveside service mark the return of dust to dust. Pallbearers lower the coffin and shovel soil into the grave as the bishop reads a hymn. A small tombstone, the size of all the rest, marks the place of the deceased in the eternal community. Following the burial, friends and family members return to the home for a meal prepared by members of the local congregation. One widower, recounting the funeral meal for his wife with tears of appreciation, repeatedly asked, “Where else could you ever get support like that?”

Community solidarity is expressed at death as a funeral procession follows a hearse.

A bereaved woman signals her mourning for a close relative by wearing a black dress in public settings for as long as a year. This symbol reminds and invites the community to respond with thoughtful care. Families who have lost a loved one will typically receive Sunday afternoon visits from friends for several months. A painful separation laced with grief, death is received in the spirit of Gelassenheit—as the ultimate surrender to God’s higher ways. Surrounded by family and friends, and comforted by predictable rituals filled with religious meaning, the separation is humane by many standards. The tears flow, but the sobs are restrained as people submit quietly to the rhythms of divine purpose. From cradle to grave, the mysteries of life and death unfold in the context of loving families and supportive ritual.

This sampler of the rhythms of Amish society demonstrates the many ways in which cultural capital and social capital are mobilized to assist individuals and bolster the common good. Longstanding Amish traditions and the organizational structure of their community provide powerful means for mobilizing collective resources for the common good. Indeed, one way to interpret Amish history and its related puzzles is to see it as an ongoing struggle to preserve social capital. Ample resources of cultural and social capital have enabled the Amish to prosper many ways—from financial to social and emotional well-being. The solidarity and identity of their community results in part from their success in thwarting four challenges that threatened to diminish social capital and weaken their community: modern education, technology, nonfarm occupations, and government intrusion. The Amish struggled with all four of these challenges in the last half of the twentieth century—challenges that we explore in the following chapters.