We try to keep the brakes on social change, you know, a little bit.

—Amish craftsman

Amish society is not a social museum; it is dynamic and evolving. Consider some of the household changes in the last fifty years. Amishwomen no longer wash clothes in hand-operated machines. They use washing machines powered by hydraulic pressure or gasoline engines. Gas refrigerators have replaced iceboxes, indoor flush toilets have replaced outdoor privies, hydraulic water pumps have replaced windmills, and gas water heaters have replaced the fire under wrought-iron kettles. Modern bathtubs have superseded old metal tubs. Kerosene lanterns have given way to gas lights. Wood-fired cookstoves have yielded to modern gas ranges. Hardwood floors and no-wax vinyl have replaced linoleum and rag carpets. Spray starch, detergents, paper towels, instant pudding, and instant coffee have eased household chores. Permanent-press fabrics have lifted the burden of incessant ironing. Although canning still predominates, some foods are preserved by freezing. Air-powered sewing machines are replacing treadle machines. Battery-powered mixers do the job of hand-operated egg beaters, and air-powered food processors have replaced hand grinders. The list goes on, but despite all these changes, wall-to-wall carpets, electric appliances, air conditioners, telephones, and electronic media have not entered Amish homes.

Things have changed outside the house as well. Many newer homes have attractive landscaping. In Amish shops, hand tools have given way to large air- or hydraulic-powered equipment, but the shops remain unhooked to public utility lines. Battery-powered drills and screwdrivers do the job of hand-turned tools. Amish farmers no longer milk their cows by hand but use modern vacuum milkers powered by diesel engines instead. Automatic-reset riding plows have replaced old-fashioned walk-behind plows. But horses still pull the new hydraulic plows. Modern hay balers towed by horses have superseded wheel-driven hay loaders. But the sophisticated balers, running on steel wheels, do not carry automatic bale loaders. Weeds and insects are sprayed by horse-drawn sprayers. Hybrid corn, grown with chemical fertilizer, is cut and picked by horse-drawn equipment.

An Amishman born in 1943 described the changes he witnessed in the last half of the twentieth century:

You’re halfway over the hill in the Pequea when you can tell your children and grandchildren about things you never had when you were their age. Never had sisters day, brothers day, etc. only work days, no fruit pizza, no cheese pizza, in fact no pizza at all. No bathrooms, no phone shanty, no church melody books. Our outside toilets then were smaller than today’s phone shanty. No compressed air or hydraulic tools. No Botschaft, no Diary, no Pathway Magazine. No $100 scooters or rollerblades. No trampolines, no gang mowers, no outdoor grills. Balers and binders put hay bales and corn bundles on the ground. No Amish school board, teachers, or Amish schools in Leacock Township. No cheese dip or pretzel dip. In fact the only dip we knew was swimming in the Pequea Creek. No fire company sales, no benefit sales, no school sales. You never heard, “yeah right,” or “have a good one.” No hot air balloons, no seat belts.1

These examples and dozens of others illustrate the fact that Lancaster’s Amish have changed dramatically in recent decades and that they have regulated the change within prescribed limits. They have avoided divisions within their church for nearly forty years despite the rapid change. Moreover, their growing population makes it ever more difficult to manage change in a uniform fashion. The riddle of social change is perplexing: Why do some aspects of Amish life change while others remain stuck in tradition? By what formula are some innovations accepted and others rejected?2

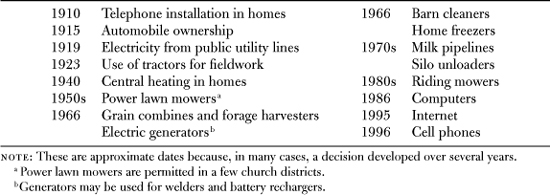

TABLE 12.1

Technological Restrictions by Approximate Date

The Amish view social change as a matter of moving cultural fences—holding to old boundaries and setting new ones. This dynamic process involves negotiating symbolic boundaries in the moral order. Church members who are moving too fast are “jumping the fence” and getting too involved with the outside world. Cultural fences mark the lines of separation between the two worlds. Coping with social change involves fortifying old fences as well as moving fences and building new ones. But regardless of whether they are old or new, cultural fences must remain if Amish ways are to persist.

No single principle or value regulates change in Amish society; it is a dynamic process, and the outcome is always uncertain. A variety of factors impinges on any decision to accept or reject a particular practice. Decisions to move symbolic boundaries always emerge out of the ebb and flow of a fluid social matrix. The factors shaping a particular decision vary greatly. With some seventy-five bishops, it is impossible to maintain uniform standards across the entire settlement. This diversity of practice, camouflaged by common symbols—horse, dress, lantern, dialect—increases as the settlement grows.

The acceptance of new products and the relaxation of old standards often occur by default. One Amishman said: “Well, change just kind of happens. Sometimes it is reviewed at a Ministers’ Meeting but then it just kind of happens by itself.” Leaders rarely plan or initiate social changes. The establishment of Amish schools is an example of intentional change. Yet even with that a consensus did not emerge for a decade. More typical are collective decisions to resist change. If a questionable practice—the use of computers or wall-to-wall carpet—begins to gain broad acceptance, the bishops may deliberately curtail it. Using biblical images, the bishops understand their role as “watchmen on the walls of Zion,” responsible for guarding the flock. They are on the lookout for “little foxes” of worldliness that dig under the walls of Zion and undermine the welfare of the church. The bishops are not a source of innovation; instead, their duty is to inspect impending changes and resist the detrimental ones.

Change in Amish society typically comes, not from the top or the center of the social system, but from the periphery. It is often instigated by those living on the edge of the cultural system who try to stretch the boundaries. So called “fence jumpers” or “fence crowders,” push against the traditional fences to test the limits. They experiment with new gadgets—a fax machine, a corn harvester, a mixer powered by air, a computer plugged into an inverter, or a Web site for their business. If someone complains and church leaders make a visit, the deviant may make a confession and “put away” the questionable item. Although Amish society has changed, it has also experienced painful steps backward when deviant practices were arrested and conveniences put away. Tractors have been recalled from the field. Bathrooms have been torn out on bishops’ orders, only to be permitted two decades later. Rubber tires have been taken off machinery; electric wires and light bulbs have been ripped out. Computers have been sold and telephones disconnected.

The fence jumpers usually know what is likely to “pass inspection.” If a new item—a calculator, disposable diapers, or a cash register—is adopted by others and no one complains too much, eventually the practice will creep into use by default. Leaders have to be careful to uproot deviant practices before they become too widely accepted and thus impossible to stop. The metaphors “walls of Zion” and “fence jumpers” suggest that the community has a clear understanding of Amish cultural boundaries. Many members explore the boundaries, “crowd the fence,” or “test the waters” under a hundred watchful eyes.

A preacher described the importance of keeping the fences around “the Lord’s vineyard” in good repair:

The Savior warned against the little foxes that dig their way into the Lord’s vineyard. I often think of the Lord’s vineyard and compare it with a good fence around the church of Christ, how it is like a good Ordnung. If the little foxes dig their way in and are not dealt with at once, or if they are allowed to remain, there is great danger that still more will come in. And finally, because they are allowed to remain and are not chased out, they grow bigger and become used to being there.… It is just the same with permitting little sins to go on till they are freely accepted as the customary thing and have taken a foothold. Wickedness takes the upper hand, and then, as the Savior says, the love of many becomes cold.3

The Amish are slow to make decisions regarding the adoption of new practices. They will act quickly if a technical development is obviously off limits—a video camera, for example. Borderline practices, such as artificial insemination of cows or the use of telephones, may be tolerated—put on probation—for several years to assess their long-term impact. Eventually a practice may grow by default, as it did with artificial insemination, or leaders may decide to forbid it. There is a delicate line of no return. It is one thing to ask a half-dozen people to “put away” their calculators but quite another thing to forbid calculators if dozens of members have used them for several years. Some probationary practices, for example the use of power lawn mowers, may continue for years within the district of a lenient bishop. Change sometimes speeds up or reverses with the ordination of a new bishop.

“When people are testing the lines,” an Amish leader explained, “the leaders don’t want to act too quick and harsh, so they just let it ride a little bit until they see what happens, or till they can get a picture of what might happen if they let it go. They clamp down if it’s something that we don’t need, that would disrupt the community, the closeness.” The division of 1966 erupted when the bishops tried to eradicate several pieces of farm equipment that had been in use for ten years in several church districts. “The problem came,” said one person, “when too many things were let go too many years.” Questionable practices must be banned before they slip into widespread use. The fate of new products or practices is weighed cautiously, for once engraved in the Ordnung, taboos are difficult to change. A rash decision may appear foolish with hindsight and bring a painful loss of face a few years later.

Once drawn, lines become hard to erase. The Amish believe it is better to keep a few taboos consistently than to revise a host of them with each new whim of progress. Thus, it is easier to accept a new practice, never inscribed in the Ordnung, than to change an old taboo. It is difficult, for instance, to relax the taboo on power lawn mowers but relatively easy to accept new hand-held weed cutters powered by tiny gasoline engines. Side-by-side on an Amish lawn, the old-fashioned push mower and the modern weed cutter appear incongruous to the outsider. Although their functions are similar, the portable weed cutter can be accepted without embarrassment because it was never prohibited by the Ordnung.

This new upscale home reflects increasing wealth among the Amish. A horse barn is in the center, and a shop on the right.

Symbolic considerations are important in the change process. The popular adage of a senior bishop in the 1950s, “If you can pull it with horses, you can have it,” is highly instructive. There are two levels of meaning in this statement. On the practical level, the old bishop understood that horses keep farming operations rather small. But in essence he was also saying, “You can use modern equipment in the field as long as you pull it with horses.” All sorts of new farm equipment were permissible in the shadow of the horse, for the horse marked off the symbolic boundaries of Amish life. In the same way, the unwritten rule in Amish shops, “If you can do it with air or hydraulic [power], you can do it,” creates cultural boundaries.

The verbal explanations given for accepting or rejecting new practices often mask the real reasons that are not stated. The labels “too worldly,” “too modern,” “too liberal,” or “too handy,” frequently cited as reasons for rejection, may hide underlying factors such as economic issues, gender roles, labor implications, or social capital questions related to social interaction or family integration. One businessman made the connection between the outward label of “worldly” and the underlying reasons for rejecting tractors:

Our people will always come out with the statement in the Bible that says “be not conformed to this world.” Any good Amishman will always say that the tractor’s worldly, the automobile’s worldly, the radio’s worldly, and the telephone and electricity. But why? If we allowed tractors, we would be doing like the Mennonite people are doing, grabbing each other’s farms up out there, mechanizing, and going to the bank and loaning $500,000, and later worrying about paying it off, putting three other guys out of business and sending them to town for work, away from their home. Do you follow? So we take the position, why do that? Let’s put a guideline on our faith and say that it’s [the tractor] not necessary; it’s too worldly.

Technological advances rejected by the Amish are, surprisingly, not considered immoral, and few of them are forbidden by Scripture. Owning a car, using a tractor in the field, and flying in an airplane are not considered evils in and of themselves. The evil lies in where a new invention might lead. The Amish ask: What will come next? Will other changes be triggered by this one? How will a new practice affect the welfare of the community over the years? Describing the taboo on the telephone, a craftsman said: “If we allow the telephone, that would be just a start. People would say, ‘Okay, now we’ll push for this and then we’ll push for that . . .’ It would be a move forward that might get the wheel rolling a little faster than we can control it, if you know what I mean.” A bishop reflected: “I might have a car and it wouldn’t hurt any, but for the oncoming generation you oughta be willing to sacrifice for them.” Such selective modernization, rather than being highly moralistic, is strikingly reflective, rational, and calculating—indeed, it is quite modern!

Finally, acceptable changes often have the appearance of compromise—a willingness to edge toward progress, but not too far; a willingness to accept some new gadgets, but with limits. Indeed the compromises create the riddles—riding scooters (halfway between walking and riding a bicycle), using modern bathrooms without electricity, riding in cars but not driving them, using public transportation but not air travel, voting but not running for office, pulling modern machinery with horses, using permanent-press fabric for traditional garb, and working in Amish shops that permit some modernization but not too much. In each instance, social change is simply a matter of setting new fences—but setting fences nevertheless. All of these factors create a zigzag pattern of change that baffles outsiders.

The response to a new practice may follow several scenarios: (1) It may be terminated by the leaders in a local district. (2) If not extinguished at first, it may spread to several other districts. (3) A “friendly” change may gradually creep into practice by default in a large number of districts and eventually spread throughout the settlement. (4) A “hostile” change may become an “issue,” provoking debate and controversy. The ordained leaders may then decide to overlook it and allow it to slip into practice. (5) The “issue” may come before the bishops’ meeting, and if they agree to prohibit the practice, local congregations will be asked to support the taboo. (6) If the bishops cannot reach agreement, the issue may simmer for months or years and eventually find de facto acceptance, or it may trigger renewed debate and new attempts to forbid it.

An issue like the appropriate use of telephones has sparked controversy for decades. Playing baseball on local league teams, an issue for several years, was finally forbidden by the bishops in 1995. Maintaining old fences and setting new ones is a delicate process, for as one leader said, “If we’re not tolerant, we’ll have more splits, but too much tolerance can wreck the whole thing too.”

The mix of factors that determines the fate of a new cultural practice or product is always in flux. Decisions about symbolic boundaries emerge within a dynamic matrix of social forces. It is hopeless to search for a simple cultural formula to predict the destiny of a new practice. However, we can identify the regulators, the forces in the ever-changing cultural equation that may influence the outcome.

What are the regulators that govern social change in Amish life? A single factor will rarely be adequate to explain a particular outcome. Decisions to move cultural fences arise from the convergence of many social forces. The following propositions identify the cultural regulators that often influence the decision-making process.

1. Economic impact. Changes that produce economic benefits are more acceptable than those that do not. “Making a living” takes priority over pleasure, convenience, or leisure. Thus, a motor on a hay mower in the field is more acceptable than one on a lawn mower.

2. Visibility. Invisible changes are more acceptable than visible ones. Using fiberglass in the construction of buggies is easier to introduce than changing the external color of the carriage itself. Permanent-press fabrics, in old styles and colors, are more acceptable than completely changing styles. Working as a cook in the back kitchen of a restaurant is more acceptable than working as a waitress in public areas.

3. Relationship to Ordnung. Changes that overturn previous Ordnung rulings are more difficult than ones that are free from previous rules. Musical instruments, consistently forbidden by the Ordnung, are less likely than calculators to be accepted. Power weed trimmers are more accepted than power mowers, which were forbidden in the past.

This booming machine shop grew beyond the appropriate limits of size and was sold to a non-Amish owner.

4. Adaptability to Ordnung. Changes that are adaptable to previous Ordnung rulings are more acceptable than those that are not. New tools that can be converted to hydraulic power or new farm machinery that can be pulled by horses are more acceptable than television, which cannot be grafted to the Ordnung in any conceivable way.

5. Ties to sacred symbols. Changes unrelated to key symbols of ethnic identity—horse, buggy, and dress—are more acceptable than ones that threaten sacred symbols. Using a modern forklift in a shop is more acceptable than using a tractor in the field, an obvious threat to horses. Jogging shoes and rollerblades are more acceptable than new hat styles because headgear for both men and women is a key identity symbol.

6. Linkage to “worldly” symbols. Changes linked to worldly symbols are less acceptable than those without such ties. Computers, with monitors similar to television screens, are rejected, whereas gas-fired barbecue grills are acceptable because they have no tie to a worldly object.

7. Sacred ritual. Changes unrelated to worship practices are more acceptable than those that threaten sacred ritual. Changing the Ordnung for nonfarm work is easier done than changing the ritual patterns of singing, baptism, and ordination. Old Order ritual changes very slowly.

8. Limitations. Changes with specified limits are more acceptable than open-ended ones. Hiring vehicles primarily for business on weekdays is more acceptable than hiring them any time for any purpose.

9. Interaction with outsiders. Changes that encourage regular interaction with outsiders are less acceptable than those that foster ethnic ties. Serving as a hostess in a public restaurant is less acceptable than working as a clerk in an Amish retail store. A business partnership involving outsiders is more questionable than one involving church members.

10. External connections. Changes that open avenues of influence to modern life are less acceptable than those that do not. Membership in public organizations and the use of mass media are less acceptable than subscriptions to ethnic newspapers and participation in church activities.

11. Family solidarity. Changes that threaten family integration are less acceptable than those that support the family unit. Forms of work and technology that fragment family life are less acceptable than changes that strengthen family interaction. Bicycles are less acceptable than tricycles. Working away from home is less esteemed than working at home.

12. Ostentatious display. Decorative changes that attract attention are less acceptable than utilitarian ones. Landscaping a lawn is less acceptable than lovely kitchens. Fancy window drapes are less acceptable than modern bathtubs and commodes.

13. Size. Changes that enlarge the scale of things are less acceptable than those that reinforce small social units. High-volume business enterprises are less acceptable than small family-run businesses. One-room schools are welcomed over multi-room buildings, and forty-cow herds over larger ones.

14. Individualism. Changes that elevate and accentuate individuals are less acceptable than those that promote social equality. Higher education and public recognition are less acceptable than correspondence courses and informal affirmation of achievement.

15. Social capital. Changes that threaten to deplete social capital are less likely to be accepted than those that produce it. Amish schooling is more highly endorsed than public education. Throwing horseshoes at family reunions is more esteemed than playing golf on a public course.

None of these factors operate alone or in isolation. The question of playing golf involves not only family, leisure, and travel, but interaction with outsiders as well—an easy target for a taboo. The use of computers is contentious because it involves making a living, connecting to the outside world, and accessing communicative technology. Change becomes especially volatile in cases where both positive and negative forces intersect.

Apart from the cultural values that regulate the acceptance of a new practice, there are many political considerations. In some cases, internal political factors may play as important a role as cultural ones.

1. Status of innovators. The status of the innovators—the “fence jumpers”—within the Amish community plays a key role in determining the acceptability of a new practice. If insulated ice coolers in contemporary colors are used by respected church members at family picnics, they will likely spread rapidly throughout the community. However, when the innovators occupy marginal positions on the fringe of Amish society, new practices are more likely to fail or to spread very slowly.

2. Leadership. The opinion and diplomatic style of the senior bishops regulate the acceptance of major changes that come to their attention. The influence of the ranking bishop and his senior colleagues is especially important. If elderly bishops have a strong aversion to a practice, its acceptance may need to await their death. Thus, the prevailing sentiment of the senior bishops is crucial in determining the reception of a new practice. The folklore surrounding the decision to accept weed trimmers shows the political influence of a senior bishop who apparently did not fully understand the issue under discussion at a Bishops’ Meeting. During lunch, when he realized that his colleagues had been discussing weed trimmers, he reportedly said, “Oh, weed pigs—well, I have one and I think it’s pretty nice.” After lunch the issue was dropped, and power weed trimmers were here to stay, despite the taboo on power lawn mowers.

3. Rate of change. The Amish sometimes talk of how fast the wheel of change is spinning. “We are all moving,” said one member. “Some are just moving faster than others, but we’re really moving in Lancaster County.” The rate of change within the community may also determine the acceptability of a particular item. The divisions of both 1910 and 1966 came at times of rapid change, and some practices may have been rejected then to simply slow the rate of change. In the early 1960s the ordained leaders placed taboos on six technological innovations after other ones, modern hay balers and gas appliances, had just been accepted. It was simply a case of how much change could be absorbed in a short period of time. Furthermore, restrictions on some of the six innovations were gradually relaxed over the years. Thus, the acceptability of a particular item may hinge on whether it comes during an era of rapid change, as well as on the number of other recently adopted practices.

4. External pressure. Legal and political pressure from the larger society has an obvious impact on moving Amish fences. Highway codes were responsible for adding electric lights, signals, red flashers, and large fluorescent triangles to Amish buggies. Dairy inspectors pressed for indoor toilets for sanitary reasons in the 1950s. In another instance, pressure from public health officials encouraged massive vaccinations following the outbreak of polio among the Amish in 1979. Zoning ordinances in some townships have limited the size and location of Amish businesses. External constraints like these have produced some of the changes in Amish life.

5. Cultural lag. Cultural lag occurs in a society when the pace of technology races ahead of traditional beliefs—for example, if the ability to clone humans outpaces ethical guidelines. Although within their society the Amish have tried to control technology, they deliberately want to lag behind the larger world. By imposing limits on some practices, they maintain symbolic separation between their subculture and modern life. While change is necessary and acceptable, unrestricted change would erode the symbolic boundaries and close the gap with the outside world.

Thus, new practices are often accepted with limits to protect Amish identity and maintain symbolic separation. Permitting changes with restrictions signals that, true to their role, the Amish are still lagging behind modern society. A modern kitchen without a dishwasher, wallpaper without designs, a shop without a telephone, a silo without an unloader, and a hay baler without a bale thrower are all ways of maintaining symbolic separation while still permitting change. Although the Amish are pleased to lag behind modern life, they have avoided the cultural lag that often plagues societies when technology leaps ahead of human values. By holding a tight rein on technology, the Amish have kept it subservient to community goals and thus have minimized cultural lag within their society.

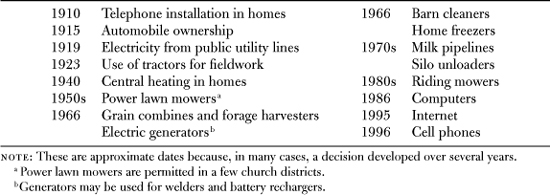

The emergence of business enterprises in Amish society illustrates the interactive process of social change as shown in Figure 12.1. Amish culture contained both resources and restraints for the development of entrepreneurial activity. The resources and restraints, interacting together, often in opposition to each other, produced the hundreds of microenterprises described in Chapter 10. Their development, in turn, has acted back upon the traditional culture to produce a variety of cultural revisions.

The resources included both cultural and social capital—the values, norms, and customs, as well as the kinship networks across the settlement that were available to empower the work of prospective entrepreneurs.4 These resources provided various forms of capital for underwriting the new commercial ventures. Cultural resources for entrepreneurship in the Amish community included frugality, a vigorous work ethic, and managerial skills forged on the farm. The social capital came in the form of strong kinship networks, large and stable family units, and an ample supply of cheap labor. A longstanding emphasis on practical education—especially apprenticeship—also facilitated the development of microenterprises. All of these resources floating in the ethnic reservoir provided cultural and social capital for the formation of Amish businesses.

FIGURE 12.1 An Interactive Model of Social Change

However, not all the commodities in a cultural tradition are beneficial for entrepreneurial development. Indeed, many restraints in the Amish cultural warehouse impede entrepreneurial activity. These cultural restraints, stowed away in the heritage of the community, include historic values, norms, taboos, customs, and practices. The church’s longstanding prohibitions against litigation, politics, individualism, commercial insurance, higher education, and involvements with the outside world all hinder the development of business. Moreover, restrictions on technology—motor vehicles, telephones, computers, and electricity—also levy constraints on entrepreneurs. The esteemed virtues of Gelassenheit—modesty and humility—as well as age-old taboos on pride, restrain advertising and promotional efforts. Many of these cultural constraints on entrepreneurship are at odds with other resources in the Amish heritage that can empower business activity. Thus, the rise of microenterprises often involved delicate negotiations between the cultural resources and restraints of the ethnic community.5

Consequently, the emergence of microenterprises has produced cultural revisions in the traditional patterns of Amish life. Business involvements are reshaping old cultural values and social arrangements, and these changes will inextricably alter the face of Amish society in the years to come. The shops and stores that were developed because of certain deeply held Amish beliefs are now acting back upon—indeed, revising—the cultural values that gave rise to them in the first place. Signs of modernity—growing individualism, control, efficiency, rationality, mobility, and occupational specialization—are clearly more and more in evidence. The rise of microenterprises is, in short, transforming the traditional culture of Amish society.

Social change is rarely simple or comfortable for any group, and the Amish are no exception. The pace of change in Amish society is typically slow, but the Lancaster settlement, sitting on the edge of the eastern megalopolis, is especially vulnerable to change. At the dawn of the twenty-first century, a variety of stress points emerged as the community struggled with rapid growth and change in the midst of an urbanizing region.

1. North vs. south. In the last decades of the twentieth century, tensions surfaced between the old historic center of the settlement and the newer, more conservative sector in southern Lancaster County. Some districts in the north had a more tolerant Ordnung, shaped by greater interaction with outsiders. The southern flank was more rural, plain, and traditional. All things considered, the more rural the setting, the plainer the church district. The north-south differences were driven not only by the external environment but by self-selection as well. Some families who wanted a plainer Ordnung moved south. The north-south tension, if not mediated carefully by the settlement-wide Bishops’ Meetings, has the potential to divide the settlement.

2. Farm vs. business. A related but not identical point of tension surfaced in Ordnung differences for farm and shop. The rules for farming, developed over many decades, were more traditional and thus more difficult to change. Because business enterprises have developed so recently, they faced fewer constraints in the Ordnung. The rules for business had to be created from scratch, and some farmers complained that the Ordnung for shops was too liberal, too flexible. Why should shop owners have so much freedom when farmers had faithfully followed the traditional restrictions for years? In response, the business owners asked why they should be restrained by old-fashioned rules designed for a barnyard when they were involved in manufacturing. Said one young shop worker, “Farmers and shop owners bicker like Democrats and Republicans.” A young farm wife whose parents own a business said, “The farm and shop are two different worlds.” The tension between these two worlds stretches across the entire settlement and is accented by the north-south cleavage.

Gazebos, storage sheds, and playhouses produced in Amish shops are shipped across the country. The growth of shops has accelerated social change in Amish life.

3. Plain vs. fancy. The foray into business created a new social class of entrepreneurs. Their resources, expertise, and lifestyle often challenge the traditional, Plain patterns of the past. Upscale homes, finer furnishings, longer trips, and greater use of technology set the commercial class apart from their more rural compatriots. The emergence of a wealthier class challenges communal values and authority as well as many traditional practices. Will the fast and fancy elite be willing to bend to the common order and use their wealth to support community life, or will they disrupt the entire system? That touchy question stalks the community.

The Amish have been a people of separation—embodied by dress, dialect, and social distance from the outside world. As we have seen, the social distance is shrinking in many ways. They are interacting more and more with outsiders on a daily basis. This growing contact dilutes the dialect, exposes them to technology, and erodes the traditional boundaries. Worried about these trends, some leaders argue for a Plainer, more separatist lifestyle.

These points of tension are propelled by two factors: occupational change and geographic location. The entry into business and the fact the Lancaster Amish community is encircled by an urban culture that is encroaching upon them at every turn have heightened the points of stress. In other words, some of the tensions would fade if the Amish were farming in secluded rural areas. But the Lancaster Amish are not. And the big question is whether church elders can mediate the tensions and hold the settlement together.

If home is a fitting metaphor for preindustrial society and if the factory reflects the realities of the modern world, the theater, with its fleeting images of reality, perhaps best captures the postmodern ethos. In many ways the Amish are preindustrial people anchored at home. Their protest against progress has focused on the modern world with its cities, factories, and mechanical products—cameras, cars, tractors, and telephones. And as we have seen, the modern world with its mechanical ethos often decontextualized social life, yet the boundaries were rather clear. All of that has changed in the postmodern context, where lines and borders suddenly become quite fuzzy.

These developments raise new challenges for a separatist people. In the modern era, telephone lines could actually be seen. The tie with the outside world was clear. Telephones could easily be banned from the home and restricted to a community phone shanty. In recent years, with cordless and cellular phones, the old boundaries have suddenly evaporated. Cellular phones can easily be concealed and carried anywhere, oblivious to all borders. In the past, television was an easy target for the Old Orders to censure.6 An agent of entertainment, television was easily banned by the church. However, computers are another story because they mix entertainment and business. The lines are becoming fuzzy, but the taboo on electricity nevertheless helps the Amish to hold computers at bay. However, the old lines were erased once again by battery-operated laptops that can be carried anywhere, mocking the old borders. Moreover, laptops can be easily tucked under a bed or hidden in a closet. Worse yet, they can be hooked up to the Internet and bring vile images and raunchy music into Amish barns and bedrooms.

Thus, the old taboos that forbade public electricity and sanctioned battery-operated gadgets face new challenges in a postmodern context. In short, the old rules of the Ordnung, designed for fixed lines and mechanical boundaries, are challenged by the amoebic web of worldwide telecommunications where everything blends into everything else. How will an Old Order people fare in a postmodern world? That, of course, is the new riddle emerging in Amishland.7

The Amish encounter with modernity involved a process of negotiation—with give and take on all sides. On some issues, the Amish surrendered to the demands of modernity; at other times, the agents of change conceded to the Amish. And as we have seen, compromise was often the order of the day as bargains were negotiated between the stewards of tradition and the proponents of progress. In a few cases, the Amish refused to negotiate—to place certain things on the bargaining table. Thus, in broad strokes, four outcomes can be identified: concessions by the Amish, concessions to the Amish, compromises, and nonnegotiables.

The first outcome, concessions by the Amish, reveals aspects of their culture that have undergone modernization. Some concessions were internally induced changes that the Amish permitted by default—modern-looking homes, milking machines, washing machines, state-of-the-art tools, cash registers, and rollerblades. These changes enhance productivity, convenience, and comfort. Other changes came about because of external pressure—legal, political, economic—from the outside world. Examples include the acceptance of bulk milk tanks, lights and signals on buggies, zoning regulations, sanitary standards for breeding kennels, and school attendance through the eighth grade, to name but a few. Some concessions—indoor toilets, for example—were prompted by a desire for convenience as well as by ultimatums from milk inspectors. In any event, these adaptations represent areas in which the Amish have conceded to outside pressures for a variety of reasons. The following is a sample of the concessions made by the Amish:

lights, signals, and reflectors on buggies bulk milk tanks

farm management techniques large dairy herds

artificial insemination of cows

chemical fertilizers

insecticides and pesticides

nonfarm employment

use of advertising in business

power tools for manufacturing

indoor bathroom facilities

modern kitchen cabinetry

contemporary house exteriors

use of professional services (lawyers, physicians, etc.)

modern medicine

Concessions to the Amish are found on the other side of the bargaining table. Here the agents of modernity made allowances for the Amish by lax enforcement, exemptions, or special legislation. In these instances, the Amish were able to achieve their cultural objectives. The Supreme Court endorsement of Amish schooling exemplifies the most dramatic concession. Other examples include the exemption from Social Security, the waiver of the hard hat regulation, and no Sunday milk pickups on Amish farms. Capitulations to the Amish include:

alternative service for conscientious objectors

waiver of school certification requirements

waiver of school building requirements

waiver of minimum wage requirements for teachers

Worker’s Compensation exemption

unemployment insurance exemption

alteration of zoning regulations (by various townships)

horse travel on public roads

lax enforcement of child labor laws

This former tobacco shed, was converted to a gift shop for tourists. It tells the story of social change among the Amish of Lancaster County.

A third outcome of the cultural bargaining sessions involves the riddles—the cultural compromises. These agreements reflect a mixture of tradition and modernity, for they typically involve some give-and-take on both sides. They symbolize a delicate balance between tradition and modernity. The distinction between the use and ownership of motor vehicles and the use of electric freezers in a neighbor’s home reflect the delicate tension. The rise of Amish businesses, halfway between farm work and factory work, is a structural compromise. Some bargains—the vocational school, for example—represent an attempt to save face for both parties. The following sampler lists some of the many cultural compromises:

the vocational school

selective use of telephones

modern machinery towed by horses

engines mounted on field equipment

tractors used at barns and shops

air and hydraulic power

hiring of cars and vans

modern gas appliances

selective use of electricity

electrical inverters

nonfarm work based at home

permanent-press fabric for traditional garb

contemporary materials for carriage construction

Amish-owned-and-operated businesses

Amish-owned tourist stands

Finally, the nonnegotiables are traditional aspects of Amish life that have remained largely untarnished by modernity. These staunch features of Amish culture have never appeared on the bargaining table. They remain in their traditional form despite the press of progress. Amish liturgy, ritual, and music, as well as the subordination of the individual to collective goals, remain intact. Limiting education, using horses, and speaking the dialect are just a few of the mainstays of Amish culture that have withstood the massive sweep of history. Some of the nonnegotiable items include:

small church districts

worship in homes

worship service format

confession, excommunication, and shunning

traditional authority structure

lay ministers

mutual aid

limited education

horse-drawn farm equipment

horse and carriage transportation

traditional styles of dress

Pennsylvania German dialect

traditional gender roles

large extended families

small social units

We have explored the many ways in which the Amish have coped with modernity. These excursions have solved some of the smaller riddles and unraveled clues to the big one: How is a tradition-laden group thriving in the midst of modern life? Their dual strategy of resistance and negotiation has worked, for they have indeed flourished. What cultural secrets have enabled them to preserve their identity as a peculiar people for more than thirty decades? They have successfully blended numerous ingredients into their cultural recipe. One ingredient alone cannot explain their growth, and eliminating a single factor would not spoil their good fortune. A variety of factors offer clues to solving the riddle of their success.8

A snow couple faces an uncertain future.

1. Reproduction. Large families and strong retention have enabled the Amish to replenish their population and grow their community. Minimal use of birth control, the labor needs of farming, the use of modern medicine, and certain religious values have all contributed to sizeable families. Childhood socialization, private education, nonfarm work, and controlled interaction with the outside world have held young people within the ethnic community and encouraged its spiraling growth.

2. Flexibility. The Amish have been willing to negotiate. They have agreed to technological concessions that have reaped handsome financial rewards. While holding firm to some taboos, they have not allowed religious practices to stifle the economic growth of their community. Indeed, their flexibility has energized their fiscal and the cultural vitality.

3. Gelassenheit. Despite their flexibility, the Amish have insisted on the primacy of community concerns over individual rights. Excessive individualism, which would splinter the collective order, is simply not tolerated. In both childhood and adulthood, individuals remain subordinate to the moral order of the community.

4. Ethnic organizations. The rise of Amish schools and businesses has created a circle of ethnic institutions that surrounds people throughout their lives. Many interlocking networks shelter individuals from contaminating relationships with the larger world. This web of ethnic ties provides ample social capital and reconfirms Amish views through daily interaction.

5. Social control. Small-scale units, ethnic symbolism, traditional authority, and religious legitimacy enable the church to exercise pervasive social control. Behavior within the community as well as interaction with the outside world is regulated in harmony with cultural values. The ritual of confession and the practice of shunning are powerful forms of control that contribute to the vitality of the community.

6. Small scale. Small-scale units, from church districts to farms and from schools to businesses, have boosted Amish success. Small social units increase interaction, enhance social control, and encourage social equality. Moreover, they preserve the individual’s identity and integration within the larger collective order.

7. Managing technology. Part of the Amish genius is the careful management of technology. They are neither enamored by it nor afraid to tame it. Able to perceive both its detrimental and its productive consequences, they have tried to selectively use technology in ways that complement and reinforce community goals and build social capital.

8. Restricting consciousness. By encouraging a practical education that ends with the eighth grade, the Amish are, in essence, restricting consciousness. Critical thinking that fosters independent thought and analysis would surely spur individualism and fragment the community. Filtering the flow of ideas and social ties with outsiders through private schooling has helped to preserve Amish society.

9. Symbolizing core values. Key symbols—horse, dress, carriage, and lantern—articulate core values of simplicity, humility, submission, and separation. These everyday symbols, used over and over again, become ubiquitous reminders of Amish realities. They objectify cultural boundaries and confer an ethnic identity on individual members. The preservation of these symbols has helped to fortify the community.

10. Managing social change. Amish survival pivots on the astute management of social change. It involves a delicate balance—allowing enough change to keep members content without destroying their core commitments. It requires selective cooperation with modernity without relinquishing cultural identity. The Amish have shown a remarkable ability to allow change while setting new symbolic boundaries to preserve the lines of separation from the world. Pulling out old stakes without planting new ones would quickly erode Amish identity.

Faced with dramatic changes in their social environment, the Amish have survived by carefully managing their cultural fences. While holding firmly to some ancient markers, they have permitted discreet change in the shadows. In other cases, they have moved old fences to keep up with the times. Moreover, they have also staked out new borders. Whether moving old fences or erecting new ones, the secret of their success lies in their insistence on keeping fences. They have discovered that good fences are imperative to preserving a people, so they move their fences rather than discard them.