1

Covid & the Culling

The Culling of the Herd: The Strong Get (Much) Stronger

One of the most surprising aspects of the Covid crisis has been the resilience of the capital markets. After a brief plunge when the outbreak graduated to pandemic, the major market indexes (Dow Jones, S&P 500, NASDAQ Composite) roared back. By summer, they had regained most of the lost ground, despite over 180,000 U.S. deaths, record unemployment, and no sign of the virus receding. Bloomberg Businessweek called it “The Great Disconnect” in a June cover story.1 Even the “Wall Street pros,” the magazine declared, were “flabbergasted.” Two months later, at the time of this writing, the virus is killing a thousand Americans per day, and market indexes continue to climb.

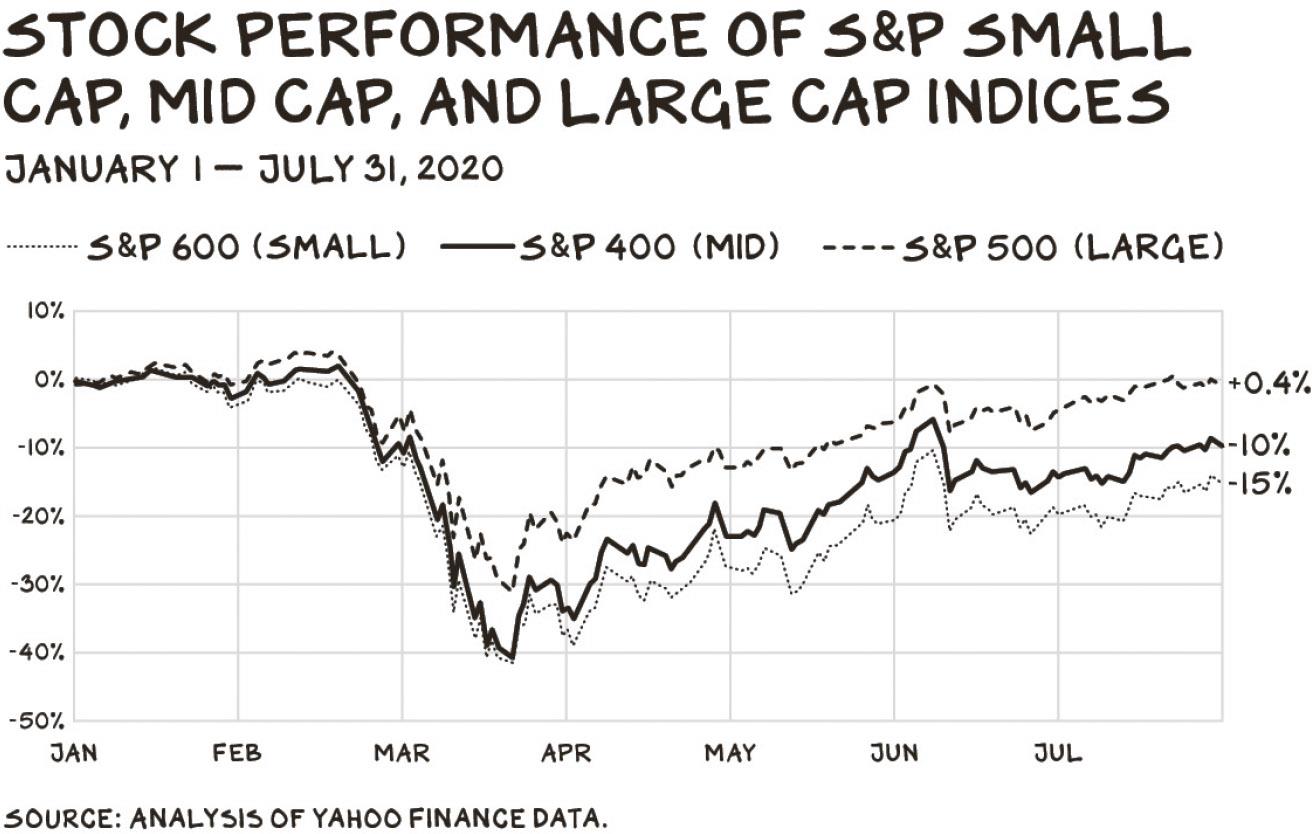

Market indexes can be misleading, however. The “recovery” has been the product of outsized gains by a few firms, notably the big tech companies and other major players. It’s not reflected in the broader public markets. From January 1 through July 31, 2020, the S&P 500, which tracks the 500 largest public companies, was just positive on the year. But companies in the middle, mid-caps, were down 10%. And the 600 small-cap companies tracked in the S&P 600 were off 15%.

While the media has been distracted by shiny objects like big tech and large-cap indexes, a relentless culling of the herd is well underway. The weak are not merely falling behind, they are being slaughtered. The list of bankruptcies is long and shocking: Neiman Marcus, J.Crew, JCPenney, and Brooks Brothers; Hertz (which owns Dollar and Thrifty) and Advantage; Lord & Taylor, True Religion, Lucky Brand Jeans, Ann Taylor, Lane Bryant, Men’s Wearhouse, and John Varvatos; 24 Hour Fitness, Gold’s Gym, GNC, Modell’s Sporting Goods, and the XFL; Sur la Table, Dean & DeLuca, and Muji; Chesapeake Energy, Diamond Offshore, and Whiting Petroleum; California Pizza Kitchen, the U.S. arm of Le Pain Quotidien, and Chuck E. Cheese.2 “BEACH” stocks (booking, entertainment, airlines, cruises and casinos, hotels and resorts) are down 50–70% on average.3

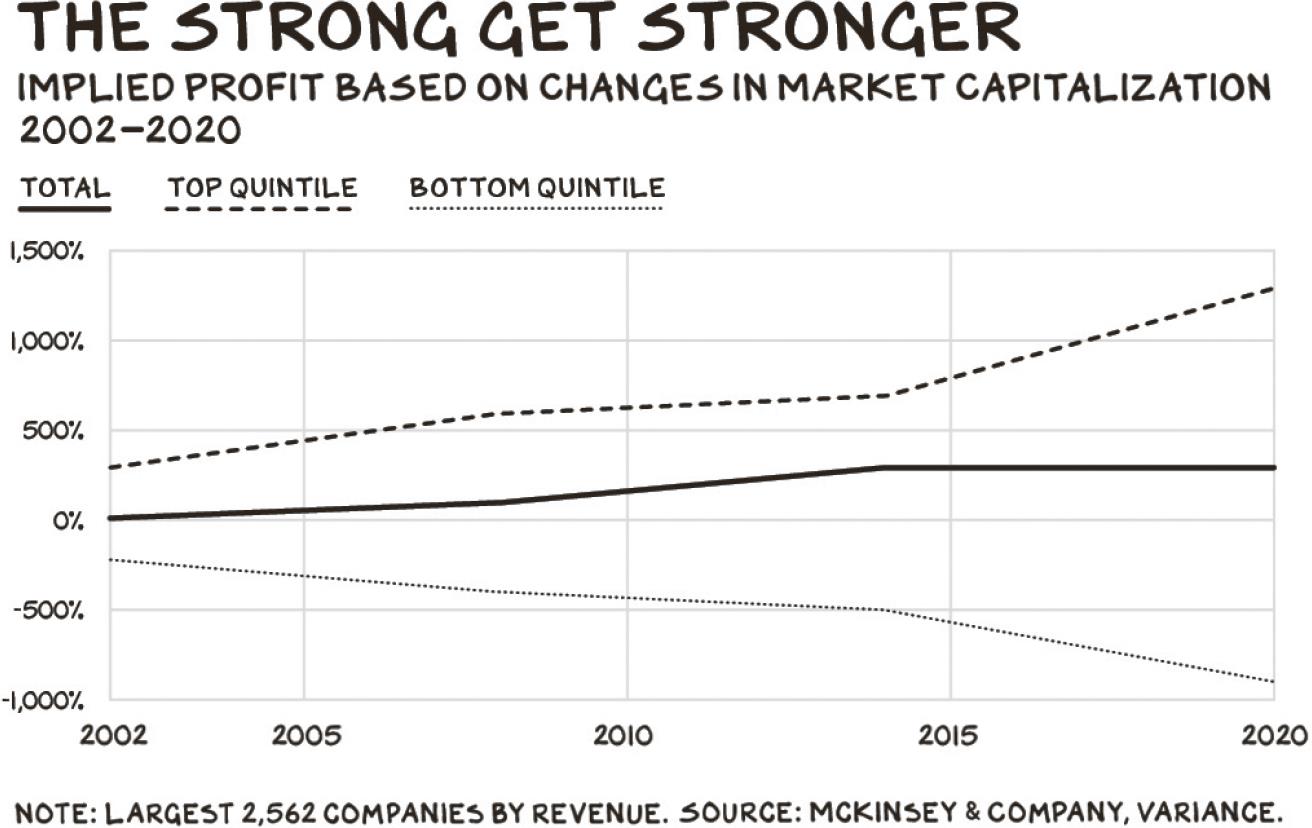

This helps explain the strong performance of the market leaders. A firm’s valuation is a function of its numbers and narrative. Right now, size can feed a narrative not just about how a company will survive the crisis, but how it will thrive in the post-corona world. Post culling, when the rains return, there is more foliage for fewer elephants. Companies with cash, with debt collateral, with highly valued stock will be positioned to acquire the assets of distressed competitors and consolidate the market.

The pandemic is also boosting an “innovation” narrative. Firms deemed innovators are receiving a valuation that reflects estimates of cash flows 10 years from now, and discounted back at an incredibly low rate. Investors appear to be focused on a firm’s vision, its narrative about where it could be in a decade. That’s how Tesla’s value now exceeds that of Toyota, Volkswagen, Daimler, and Honda combined. That’s despite the fact that in 2020 Tesla will produce approximately 400,000 vehicles, while the other four companies will build a combined 26,000,000.

The market is making bold bets about the post-corona environment, and we are seeing both big gains and steep declines. At the end of July, Tesla was up 242% on the year, while GM was down 31%. Amazon was up 67%, and JCPenney was bankrupt. This “disconnect”—between the big and the small, the innovative and the old fashioned—is as important as the more talked-about gap between the market and the broader economy. Today’s winners are judged tomorrow’s bigger winners, and today’s losers appear doomed.

The thing about capital market predictions is that they are to an extent self-fulfilling. By deciding that Amazon, Tesla, and other promising companies are winners, the markets lower those companies’ cost of capital, increase the value of their compensation (via stock options), and enhance their ability to acquire what they cannot build themselves. And there is an incredible amount of capital looking for a home right now. The U.S. government has poured $2.2 trillion into the economy, and because of some terrible policy decisions (more on that later) a huge amount of that is going right into the capital markets. So companies that were doing well before the pandemic hit have benefited remarkably from this worldwide crisis. They found funding available to absorb revenue losses, bulk up against the competition, and expand into the new opportunities the pandemic is opening up. Meanwhile, their weaker competitors have been shut out of the capital markets and will see their debt ratings cut, the holders of their payables come calling, and customers skittish about long-term deals.

There is a non-economic arbiter to who perishes, survives, or thrives: government support. Airlines, for example, are in no kind of shape to survive this pandemic in their current form. It’s difficult to envision a product more conducive to the spread of a virus than an airplane. The pandemic accelerates remote work and obviates business travel, the industry’s cash cow. In addition, airlines have huge overhead and difficulty reducing costs when revenues drop. Several smaller domestic airlines, not seen as national champions, and a number of foreign carriers, including Virgin Atlantic, have declared bankruptcy. But I suspect we won’t see a single major U.S. carrier go under, because the airlines have a death grip on the U.S. Congress. In April 2020, the government gave them $25 billion, and they will likely get more. A combination of good lobbyists and PR people, high consumer awareness, and a deep connection to national pride can save an industry by giving it a capital lifeline from history’s deepest pocket.

Surviving the Culling: Cash Is King

For the last decade, the markets have replaced profits with vision and growth when determining the value of a company. Blitzscale, at any cost. Costs are just investment, and profits or dominance will come. Why not? Cash flow is irrelevant when equity investors are lining up to invest more capital, and with a history of taking very little debt and thriving on intangible assets, tech balance sheets in particular received little scrutiny.

In the pandemic, however, cash is king, and cost structure is the new blood oxygen level. Strong balance sheets mean capital to get through the lean times. Companies with cash, low debt or cheap debt, high-value assets, and low fixed costs will likely survive.

Costco is well positioned to buck the ugly trends in retail for a number of reasons, including 11 billion of them sitting in its bank account. Honeywell’s $15 billion will likely carry it into a post-corona land of milk and honey. Johnson & Johnson has nearly $20 billion—it’s not going anywhere. Every one of these companies will have their pick of the assets and customers left behind when their weaker competitors shut down. In every category, there will be more concentration of power in the two or three companies with the strongest balance sheets.

There’s been a lot of talk in the past few years about the problem of share buybacks—companies using earnings to purchase their own shares. That juices the stock price, often leading to large bonuses for senior management, but at no benefit to the underlying businesses. As we crash into a recession, management is going to have second thoughts about this strategy. They are going to want that cash back, but it’s too late. Share buybacks have always been ticking time bombs, trading the long-term future of the company for short-term investment returns, and now those bombs are detonating. These firms should be allowed to fail. Not to let them fail is to decide, as an economy, that we favor equity over debt, as the debt holders should own these assets.

The biggest toll will be on bigger companies with a lot of employees that had a bad balance sheet. I said in March 20204 that Ann Taylor will go away, and by July its operator, Ascena, filed for bankruptcy, owing $10–$50 billion to 100,000 lenders, mostly real estate owners. Chico’s will also go away. Failure to innovate and attract a younger, more online customer base has been lethal to traditional retail even pre Covid. Medium and large companies with weak balance sheets will create the most damage from an economic standpoint. This is the challenge with owning a restaurant. A large fixed cost—your lease—and little or nothing you can do about it, and because it’s a low-margin business with few sources of funding, there’s typically no capital cushion to survive lean times.

Crisis Management 101

At the outset of addressing this crisis, it’s essential to understand where a company is on the strategic spectrum of the pandemic. The right moves for the biggest elephant in the herd are not the smart play for a “sickly gazelle” (how Jeff Bezos once described small book publishers). Sector plays a big role here: some are doing great (technology), some are just okay (transportation, healthcare), and some are struggling (restaurants, hospitality). Within sectors, relative strength in key metrics (brand, management, balance sheet) call for different strategies. Even in the weakest sector, someone will come through the other side.

But many won’t. Stubbornness is a virtue to a point, but companies in hard-hit sectors that are not in a position to feast on weaker competitors need to think well outside the box. Is there a pivot available? An asset that can be bridged to a new business? For example, I’m an investor and on the board of the nation’s largest yellow pages company. Now, they are morphing into a customer relationship management (CRM) company. They’re taking advantage of their strongest asset—their relationship with hundreds of thousands of small businesses—to offer them a CRM, SaaS-based product. It’s working.

If the strongest asset is the brand, but the business is in structural decline, think seriously about milking the brand until it dies. As much as we humanize them, brands are not people—they are assets to be monetized. Letting one die is only a bad thing if you don’t get all the value out of it in its golden years. Too many managers try to Botox their aged brands into a semblance of youth, when they should be letting them go to a profitable hospice. Use those last profits to ease the transition for the real people who made the brand valuable, the employees and customers. In sum, the best that many second-tier players with no rainy-day fund can do is look for a graceful exit that protects employees and doesn’t leave customers in the lurch.

OVERCORRECT

For those with a path to the post-corona future, however narrow, the watchword for how to respond in a crisis is overcorrect.

The paradigmatic example is Johnson & Johnson’s response to the Tylenol scandal. The reason Johnson & Johnson is one of the most valuable companies in the world is that, in 1982, when a handful of Tylenol bottles were poisoned after leaving the factory, presumably with the intent of extortion, the company didn’t say it wasn’t their fault and let the police handle it. Instead, J&J cleared 31 million bottles of Tylenol off the shelves, established a hotline, offered rewards for information about the crime, and replaced purchased bottles. Was the poisoning J&J’s fault? No. Did the company overreact? Yes. Did it assure the health of the public and restore the credibility of the company? Yes and yes.

Dr. Mike Ryan, who leads the World Health Organization’s Health Emergencies Programme, put it well, a lesson that applies to all emergencies: “If you need to be right before you move, you will never win. Perfection is the enemy of the good when it comes to emergency management. Speed trumps perfection. And the problem we have in society is that everyone is afraid of making a mistake.”

For companies in a weak position, survival will depend on radical cost cutting. We are seeing that even with the discovery of a vaccine, getting back to “normal” will be slow and unpredictable. Nearly everyone is facing revenue shortfalls, and companies that won’t be getting an infusion of equity capital, cheap debt, or government largesse need to tighten belts like they never have before. There’s an old adage in retail: your first markdown is your best markdown. Better to sell something at 80% of your budgeted price than to wait another month and have to dump it at 60%. Waiting to take action only makes the problem worse.

Go through your expenses as a company and as a team. Get to the lowest cost base you can, fast. If you have a landlord, call and say, “I need to suspend payments.” Cut compensation, starting with yourself first, then your highest earners—they can afford it, and it sends a message. Find alternative means of compensation—equity, deferred compensation, vacation time—anything that doesn’t require cash out the door. There’s one exception though: severance. You can’t protect jobs, but you can protect people. You have to be fairly Darwinian and harsh around job cuts, but then do everything you can to provide good severance.

Clean up the deadwood. Now is the time to take away the “semi”-retired founder’s corner office, cancel the fourth and fifth magazine subscription for the lobby, and tighten up the travel and late-night-meal policy. In June 2020, Microsoft went big on this front, taking a $450 million charge to get out of the brick-and-mortar retail business, a legacy of the Ballmer era.

GOING ON OFFENSE

Besides cutting costs, where can you do more with the assets you can’t shed? I spent a lot of time in summer 2020 on the phone with leaders in higher education who are feeling intense pressure from the pandemic, but because of tenure, strong unions, and facilities, have little cost-cutting flexibility. So what they are doing is trying to decrease their costs per student by reaching more students. A modest investment in technology allows them to expand class sizes without corresponding physical facilities.

For 10 years, I’ve taught Brand Strategy in the fall to a full auditorium of 160 people at the NYU Stern School of Business. It’s a popular class, and more students would take it, but that’s our largest classroom. In 2020, however, Stern went virtual, and so that limit was lifted. Now there will be 280 students in my virtual auditorium for Fall 2020. That means some additional fees to Zoom, and we’ll hire some additional TAs, but my salary doesn’t change, and it doesn’t require more Manhattan real estate.

Companies fortunate enough to be in a position of strength should be flexing their pandemic muscles. Microsoft’s interest in acquiring TikTok is only the beginning of an M&A (mergers and acquisitions) environment that may be the most robust in a decade. Big tech and the innovator class are playing with fully valued/inflated currency, meaning almost any acquisition is accretive. It takes only a sliver of equity to make a generous stock offer, and cash deals can add more market value by virtue of the multiples new product lines can earn. For example, Lululemon spent $500 million in cash to buy Mirror, and the markets rewarded the company, recognizing the work(out)-from-home movement had leapt a decade, juicing its value $2 billion the next day.

The post-corona world will prize contactless transactions of all kinds. We’ll be dumping business travel, business dinners, and business golf (thank god) in favor of more efficient email, phone, and video communication, and what we all need more of—dinner at home and time to unwind. Rethink the benefits you offer your employees—a pet stipend may be more welcome than a gym membership. Flexibility around working from home may be by far the most appreciated perk you can offer. Listening to employees will not only help make the most effective decisions, but it also builds trust, a scarce quantity during a crisis.

Safety and survival are your main goals, and that may mean not just tweaking but entirely rethinking your business model. Are you a restaurant in a nice part of town? That key experience aspect has been severely degraded in favor of safety and convenience. Can you rethink your menu and space so you can offer takeout and “provisions,” as one New York restaurant did,5 still maintaining an air of luxury while being brutally obsessed with survival? Are you a rare books brick and mortar with not much of a website? Time to amp up digital. I got a used book on Amazon that was so well packaged, I had to find the bookseller. I did, and then bought more, directly from their website, because the gift wrap and the experience were so great. In terms of digital, anything you can do to save your customers time will build your NPS (Net Promoter Score) more than flowery marketing language about “these unprecedented times.” Cut to the chase, make your site as efficient as possible, save me time.

For every business, this is a good time to forget what you’ve learned and make the hard changes necessary to position yourself for a post-corona world. Start with a clean sheet of paper. Freed from legacy decisions, how would you change how you go to market, figure out the right size and composition of your labor force, and decide on your ideal compensation strategies? You get cloud cover to make big decisions, big investments, and bold bets in a global pandemic—no playbook and a lot fewer guardrails.

Where to place those bets? The biggest opportunities will be in areas where the pandemic is accelerating change.

The Covid Gangster Move: Variable Cost Structures

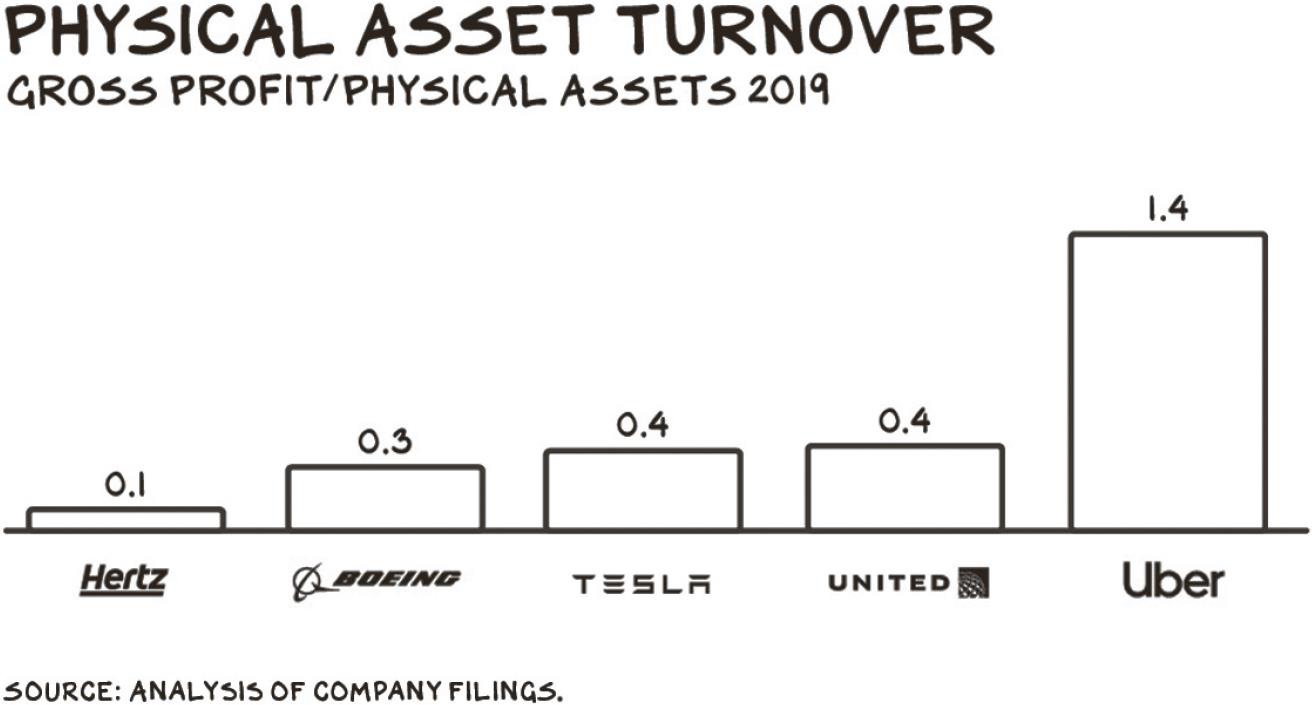

Cash is great for survival purposes, but the real gangster move is to be capital light, that is, to have a variable cost structure. Uber is the paradigm of this new model. The way the company leverages other people’s assets is why its share price held its value, despite the near collapse of its core business in the early days of the pandemic. Uber rents space in other people’s cars, driven by non-employees (in the eyes of the law, anyway). The second an Uber car stops making the company a profit, it effectively disappears and costs the company nearly nothing. Revenue can go to zero in a crisis, and Uber can take its cost down 60–80%. Hertz, on the other hand, owns its cars and went bankrupt. Boeing has $10 billion in cash, but if its revenue goes down 80%, they can take costs down maybe 10%, maybe 20%. Tesla can furlough its workforce, but it still owes hundreds of millions of dollars on leased properties (factories, retail stores, charging stations), billions of dollars in purchase commitments to feed those factories, health insurance payments for its workforce, and has to provide warranty service on nearly a million Teslas on the road today.

The Uber model is exploitative, to be sure. Uber’s “driver partners” still have to make their car payments and insurance premiums. The model is akin to United Airlines telling its flight crews to bring their own 747 if they want to get a paycheck. But it’s a model that works. For Uber.

Airbnb is another well-positioned player, despite being in an industry that virtually disappeared for a few months. They monetize other people’s property, which means someone else is responsible for the mortgage payments. Their business will rebound well, since renting private spaces is going to look attractive long before people are comfortable returning to hotels, amusement parks, or cruise ships. As more and more unemployed people consider joining the gig economy, it will be a good time to rent that extra room, or even move in with your parents for a while and rent your whole apartment.

The gig economy is attractive for the same reasons that it’s exploitative. It preys on people who have not been casted into the information economy, as they didn’t have access to the requisite credentialing or can’t work a traditional job—they might be a caregiver, have a health condition, or just not speak great English. Uber preys on the disenfranchised, and offers subminimum wage work that is flexible and has few start-up costs. Is this a failure of character and code on the part of Uber management and their board, or an indictment on our society, which has allowed these cohorts of vulnerability to form in the millions? The answer is yes.

The Great Dispersion

Covid-19 is accelerating dispersion across many economic sectors. Amazon, of course, took the store and dispersed it to our front door. Netflix took the movie theater and put it in our living room. We’re going to see this dispersion across other industries, including healthcare.

Most people who survived Covid-19 never set foot in a doctor’s office. During the pandemic, people with psychological conditions saw their therapists and had medications adjusted without leaving home. This was enabled by changes to insurance rules, which had largely frowned on telemedicine and remote prescribing. Those changes are not likely to be undone, and a flood of innovation and capital will pour into the opportunity well they have drilled. The high-def camera on your mobile phone is a decent diagnostic tool already, but it’s a small step to consumer-friendly diagnostic tools arriving on our doorsteps, used, and shipped back. Specialists will be consulted across town, across the country. Teladoc Health, the largest independent U.S. telemedicine service, is adding thousands of doctors to its network.6 The transition to electronic health records was a major thrust for Obamacare and may be the program’s most lasting and important legacy, as electronic records enable a dispersal of an industry ripe for disruption.

We’ve seen a shift toward dispersion in grocery take place with unheard-of speed. While pre pandemic, most people preferred to pick out their own food, especially produce, stay-at-home advisories have taught us it’s okay not to squeeze the avocado. From the beginning of March to the middle of April, online grocery sales increased roughly 90%, while food-delivery sales melted up 50%.7 The infrastructure this shift has inspired, from warehouses to entrenched customer relationships, will survive the pandemic and change our food system. Habits that should have taken a decade to acquire are a new normal.

WORKING FROM HOME

Of everything wrought by the pandemic, perhaps the most visible and widespread trend acceleration is the radical transition to working from home. The dispersal of work has arrived. It’s a double-edged sword, to be sure. Like so much else in the pandemic, its greatest benefits are being reaped by the already wealthy, who have home office setups, childcare help, or other means of making money during lockdown. Most working-class people, on the other hand, can’t do their jobs at home, since they are tied to the store, warehouse, factory, or other place of work. And for those who can do it, it may free us from commutes and office coffee, but it imposes burdens as well.

As a business owner, I’ve long been skeptical of work-from-home cultures. Ideas need to flirt and fight with one another, and that happens best in person. Just as some things are better said in a phone call than an email, meetings can be more productive and lead to more camaraderie than Zoom calls. Presence is also great for accountability—visual cues help build trust. Also, proximity is key to relationships, which are key to the culture of any organization.

But presence is also expensive. Office space, commuting, dry cleaning, overpriced sandwiches—the costs add up. Meanwhile, the tech that enables virtual interactions keeps getting better and less expensive. The trillion-dollar question is whether tech can disperse our workforce without reducing a culture of innovation and productivity. Six months ago, I still thought it could not. The virus doesn’t care about my management theories, however, and so here we are.

Despite stereotypes that telecommuting breeds slacking, early data suggests productivity is up, at least at some companies.8 As of June 2020, 82% of corporate leaders plan to allow remote working at least some of the time, and 47% say they intend to allow full-time remote work going forward.9 We are still early in the WFH experiment. High stress levels, distractions from family, and improvised tech aren’t a great match. We all have Zoom fatigue, but new tech is emerging that can improve team interactions. We crave contact, but not surveillance. This is a massive opportunity for innovation. Zoom, for instance, announced its first dedicated at-home videoconferencing system, a 27-inch monitor with microphones and wide-angle cameras. The start-up Sidekick offers an always-on tablet aimed at small teams that want constant and spontaneous communication among coworkers, simulating sitting together all day long.10

Anecdotally, I think working from home has been harder, not easier, for most people—certainly for parents of young children—and the coveted work-life balance seems further away. But the overwhelming reason for that is that we are also trying to do K–12 school from home, and that’s a difficult but likely prospect short-term. As K–12 goes back to 100% in person by 2021, the benefits of WFH will hopefully loom larger (no commuting, no morning rush, less time getting ready, working from several spots in your house).

This is an opportunity for employers to come up with new perks and new ways to support employees. Companies in big cities could spend $2,000 a month for office snacks. (At L2 it was $20,000 a month.) Now that we’re not buying those, at my new start-up, Section4, we are giving employees monthly grocery debit cards. They can buy their own snacks. Many people don’t have home setups comfortable enough to spend eight to ten hours a day in. Do you do an audit of home office needs and buy a few people good chairs? Do those who already have chairs get a speaker? Do you buy everyone a good mic or just give them gift cards for office supply stores? The options will depend on the size of your team and your budget. The important thing is to show awareness and support.

Working from home on Fridays used to be a perk few people enjoyed. Post corona, working from home on Friday (or Monday, Wednesday, and Friday) will be a new normal.

SECOND-ORDER EFFECTS OF THE DISPERSION OF WORK

Some retailers stand to benefit. If I’ll spend another 10–20% of my waking hours at home, I’ll get the great couch from CB2 or invest in Sonos. Home improvement purchases were up 33% in March, even as much of the country went into lockdown—if people are going to be stuck in their homes, working from home, it’s time to tackle those home improvement projects.

The normalization of work from home may help create greater opportunities for women. Women under 30 who don’t have children have closed the pay gap with their male counterparts. Once women have kids, they go to 77 cents on the dollar relative to their male counterparts. Part of our ability to create the same career trajectory for women with kids is to create more options and flexibility around where they work from. Part of working from home is the ability to work at different hours than the rest of your team, allowing for family needs like caretaking, side gigs, or hobbies that contribute to a work-life balance. It may be time to unroll the yoga mat or dust off the drum set in the garage, instead of spending 225 hours, or 9 full days, a year commuting.11

However, there are risks to working from home. If your big tech job can be moved to Denver, there’s a decent chance it can be moved to Bangalore. Also, as great as it is to work from your couch, we are an unequal society in which women still do more housework and caretaking than men. As a result, especially as schools are reluctant to reopen, if extended childcare or homeschooling is required, the more likely parent to drop out of work will be the woman. This is especially true for the lower income brackets.

Career advancement is often the result of in-person, informal communications, like drinks after work or impromptu lunches. Presence has implications for who is top of mind for a promotion, or whom an executive is most familiar and comfortable with. This calls for companies to make extra efforts to include employees working from home in meetings, informal communications, and advancement decisions. Judge performance, not the schedule.

Even with the best efforts, it will be difficult to avoid a disparity in opportunities between those who can come to the office five (or more) days a week, and those who cannot, whether because of childcare or other dependent-care obligations (more likely to be women), because they are immunocompromised, or because they live a thousand miles away. This is unfair to employees, but it’s an employer’s loss—the very obstacles that interfere with office attendance can forge skills and discipline. In the nine firms I’ve founded, my experience has been that employees who are also mothers have often mastered a level of efficiency that noticeably outstrips their peers who are fathers.

I’ll talk more about this in chapter 5, but we can’t ignore the fact that remote work will be a means of increased income inequality. Sixty percent of jobs that pay over $100,000 can be done from home, compared to only 10% of those that pay under $40,000. This is a major contributor to the pandemic’s disparate impact across income levels (low-income workers are nearly four times as likely to have been laid off or furloughed as high-income workers). Post corona, the benefits of increased flexibility that come with remote work alternatives will flow to the already well off.

There’s an intra-class dynamic here as well, though this is more about comfort than fundamental inequality. Working from home can mean a lot of different things. Senior people with big houses in the suburbs have dedicated office rooms and equipment, many have even worked out full-time childcare, or their kids are old enough they don’t need constant supervision. Junior people, on the other hand, are more likely to live in cramped apartments and starter homes that don’t have dedicated workspaces.

Those frustrations spell opportunity, however. The same tech that enables working from home also enables working from satellite and temporary offices. I was, to put it mildly, a WeWork bear,12 but I’m actually bullish on the underlying concept. Flexible spaces where people can work alone or in teams, distributed throughout cities and beyond, sounds like the future.

The second-order effects of a shift toward much more working from home—or working from remote offices—are fascinating. What happens to cities in a world where you don’t need to live in them?

It’s a trend worth watching, but I wouldn’t write the obituary of cities just yet. Forty years ago, it was fashionable to predict the death of the city, but they came roaring back, and not because people had to live in them for their jobs. Young people brought cities back because they wanted to live near other young people and to get access to culture and entertainment. Indeed, those draws have proven so strong that many cities, New York first among them, have become so desirable that young people—in many cases the children of those who saved cities in the first place—can no longer afford to live there. Best case, we see the midlife professional move out to leafy, charming villages with great schools, and let the twentysomethings come back to the Village.

The Brand Age Gives Way to the Product Age

At my first firm, Prophet, we roamed the world preaching to Global 500 companies that a firm’s ability to provide above-market returns depended on their ability to develop a compelling brand identity, and then treat this ID as a religion, nodding to the identity with every action and investment. And the way that was done was through the awesome power of broadcast advertising.

From the end of WWII until the introduction of Google, the gangster algorithm for shareholder value was simple—create an average, mass-produced product and infuse it with intangible associations. You then reinforce those associations through cheap broadcast media, which occupied the average American for five hours a day. The Brand Age grabbed the baton from an out-of-breath manufacturing sector. Firms like McKinsey, Goldman Sachs, and Omnicom built the workforce and infrastructure for a booming services economy. The Brand Age created gurus, marketing departments, and CMOs, and kept black town cars lined around the headquarters of Viacom and Condé Nast. Emotion injected into a mediocre product (American cars, light beer, cheap food) was the algorithm for creating hundreds of billions in stakeholder value. Kodak moments and “teaching the world to sing”13 translated to irrational margins based on an emotional response to inanimate products.

Don Draper lived the high life. The ad business saw creatives who dyed their hair in their forties and wore cool glasses as the messiahs of the last half of the twentieth century. The ad industry brought brand to washing machine and minivan manufacturers. Brand was a new kind of pixie dust that offered an exceptional lifestyle to average businesspeople. Believers in the advertising industrial complex would be blessed with sacrosanct margins despite products void of differentiation.

I made a nice living preaching this. And then … the internet.

I sold my stake in Prophet in 2002. I had started hating the services industry. Success in the services industry is a function of your ability to communicate ideas and develop relationships. I loved the former and despised the latter—managing colleagues and being friends with people for money. The services industry is prostitution, minus the dignity. If you spend a lot of time at dinners with people who aren’t your family, it means you’re selling something that is mediocre.

I got lucky and got out. The Brand Age was drawing to a close. There’s no one moment, but a series of opportunistic infections: Google, Facebook, and technology that liberated the affluent from ads. If you want to mark the beginning of the end, you could do worse than Tivo. Launched, fittingly, in the last few months of the twentieth century, Tivo allowed those with extra disposable income to trade it for something even more valuable: their time. Once you owned a Tivo, with just a little patience and prior planning, you never had to watch a commercial again. Advertising became a tax that only the poor and technologically illiterate had to pay.

Just as Tivo was giving us a preview of a world without commercials (at least for those who could afford it) a slew of other new products were coming along that were ridiculously better than what we used before (Google vs. classified ads, Kayak vs. travel agents, Spotify vs. CDs). They don’t need to interrupt Succession every ten minutes.

If Tivo marks the beginning of the shift from the Brand Age to the Product Age, the summer of 2020 saw the Brand Age’s end. The killing of George Floyd and subsequent protests briefly displaced the pandemic in the front and center of our national consciousness, making obvious the passing of the Brand Age into history. Seemingly every brand company did what they always do when America’s sins are pulled out from the back of the closet where we try to keep them hidden: they called up their agencies and posted inspiring words, arresting images, and black rectangles. Message: We care. Only this time, it didn’t resonate. Their brand magic fizzled.

First on social media, then tumbling from there onto newspapers and evening news, activists and customers started using the tools of the new age to compare these companies’ carefully crafted brand messages with the reality of their operations. “This you?” became the Twitter meme that exposed the brand wizards. Companies who posted about their “support” for black empowerment were called out when their own websites revealed the music did not match the words. The NFL claimed it celebrates protest, and the internet tweeted back, “This you?” under a picture of Colin Kaepernick kneeling. L’Oréal posted that “speaking out is worth it” and got clapped back with stories about dropping a model just three years earlier for speaking out against racism. The performative wokeness across brands felt forced and hollow. Systemic racism is a serious issue, and a 30-second spot during The Masked Singer doesn’t prove you are serious about systemic racism. That’s always been true, about ads on any issue, but social media and the ease of access to data on the internet has made it much harder for companies to pretend.

WELCOME TO THE PRODUCT AGE

Paying lip service to social causes is a sideline for brand builders, of course, but those digital tools are damaging the core business as well. In the Brand Age, a wealthy traveler new in town tells his cabdriver to take him to the Ritz, because that’s the brand he knows. In the Product Age, this valuable customer checks her phone as she gets off the plane, learns that the Ritz is being renovated and that reviewers believe it is overpriced, and she crowdsources a recommendation for a new boutique hotel in a hipper neighborhood.

The losers in this transition are the media companies that provided platforms for the big and bold brand-building advertising of the Brand Age, and the creative-driven ad agencies that made them. If you make your living on the back of 30-second spots featuring award-winning ad copy and talented actors connecting emotions to products, this is not the future you were hoping for. Twenty years ago, Levi Strauss & Co. asked three outside advisers to sit in on their board meetings: two advertising agency icons, Lee Clow and Nigel Bogle, and yours truly, the brand strategist. That’s how important creative and advertising was to the company. I’ve been in perhaps 150 board meetings since those Levi’s days, and I don’t think I’ve heard a director ask what the ad agency thought about anything. Their time has passed.

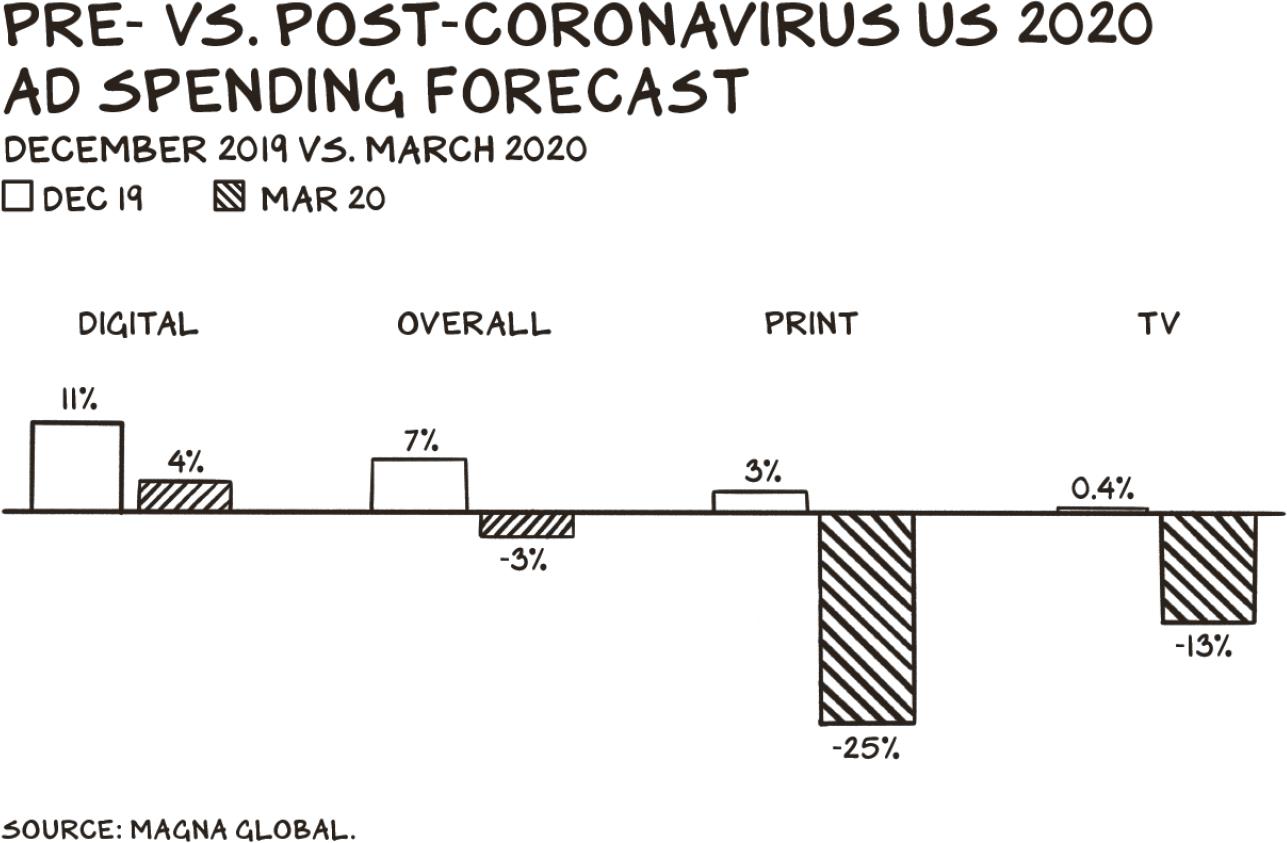

Troubled economic times always mean a pullback in ad dollars, and that is initially affecting the online and traditional players. Search terms and ads on Google and Facebook plunged 20% in the month after George Floyd’s killing. But the pullback in traditional media was even steeper. The recovery will be equally bloody. Because when the tide comes back in, it will flow only to the advertising media of the Product Age, not the old guard of the Brand Age. The Google-Facebook duopoly’s share of the digital ad market is predicted at 61% in 2021.14

In 2012, I was doing work with the Four Seasons. Great firm—nice people, Canadian (redundant). During the Great Recession, the luxury hotel brand had to cease all print advertising as revenue per room had declined 25%. And a strange thing happened when demand returned: the absence of print marketing didn’t seem to make any difference. Multiply this phenomenon by a million, and you have what will happen—thousands of the biggest advertisers globally are about to use this forced abstinence from broadcast media (with business down 30–50%) to kick the habit, and never return.

The two largest radio firms, iHeartRadio and Cumulus Media, will likely be Chapter 11 (again) by summer 2021. Radio advertising is projected to decline 14% in 2020.15 Covid-19 has a mortality rate of 0.5–1% in the U.S.16 Among U.S. media firms, the death rate will be ten times higher. Firms ranging from Condé Nast to Viacom have furloughed and laid off people as Facebook and Google have ramped up hiring. How do you identify the best people at News Corp, Time Warner, and Condé Nast? Simple, they will soon be working at Google.

Even harder hit are the digital marketing firms that aren’t Facebook or Google. BuzzFeed and Yelp have seen display ads on site decline 40–70% in 2020 vs. 2019 and are in the ICU. Vox, HuffPo, and Vice will follow. Some will make it out. Some.

Red and Blue

There are two fundamental business models. One, a company can sell stuff for more than the cost of making it. Apple takes about $400 worth of circuits and glass, imbues it with the promise of status and sex appeal through brilliant advertising, and charges me $1,200 for an iPhone. Two, a company can give stuff away—or sell it below cost—and charge other companies for access to its product: the consumer’s behavioral data. NBC hires Jerry Seinfeld to write a TV show, films dozens of episodes on a studio lot in LA made to look like a sanitized version of Manhattan, then beams it out for free to anyone with a subscription to watch. But every eight minutes, NBC interrupts the witty banter with several minutes of ads, for which it charges the advertisers, who are its actual customers. The product, of course, is you.

Some businesses combine both. The NFL gets about a third of its revenue from the first model: selling tickets to fans at the games and selling clothes and other items with NFL logos on it. And it gets about two-thirds of its revenue from selling access to those fans to advertisers, from 5-million-dollar Super Bowl ads to the corporate logos plastered over every available square foot in the stadium.

As we move into a tech-based economy, however, that second business model becomes both more lucrative and more troubling. In the old days of advertising, we only had to give up some of our time and attention to get the free stuff the advertising paid for. But when our relationships are online, the companies giving us this supposedly free stuff suddenly have all this data about us—what we read, where we shop, who we talk to, what we eat, where we live. And they are using that data to make more money off of us. We used to trade time for value. Now we trade our privacy for value.

Furthermore, the companies that accumulate this data are getting more sophisticated at using it to capture more of our data, and more of our time. NBC could only send out one program at a time, and it had to do its best to gauge what mix of programming over the course of the week would net it the most valuable audience to sell to its advertisers. But Facebook can customize its programming for every single one of its advertising attention resource units (what you and I call “people”) to keep them clicking through screens, thus generating more inventory for Facebook’s advertising machine.

Industries will increasingly bifurcate along this line of division. We’ve already seen this in mobile. Android versus iOS offers you a choice between a decent product for low or no upfront cost, but the sacrifice of your data and privacy, versus a higher quality, better-branded product, for much more cash up front, but much less exploitation on the back end. Android phones poll 1,200 data points a day from their users and send that back to the Google data-mining mother ship. iOS phones pull 200, and Apple bends over backward to emphasize that data is not being used for profiteering. “The truth is,” Apple CEO Tim Cook said in 2018, “we could make a ton of money if we monetized our customers, if we made our customers our product. We’ve elected not to do that.”17

The entire world is bifurcating into Android or iOS. Android users are the masses who trade privacy for value. iOS are the wealthy who enjoy the luxury of privacy and status signaling by shelling out $1,249 plus tax (more than one month’s household income in Hungary) in exchange for $443 in sensors and chipsets (what it costs to make an iPhone).18

You can get your video entertainment on YouTube for free, but it’s a mishmash of content, and the algorithm that is supposed to help you sort through it pushes you toward whatever retains your interest. And unless you’re a modern-day saint, there’s a good chance you’ll be served inflammatory, provocative content, whether it’s conspiracy theories, violence, or political extremism. Google tracks your views, associates it with everything else it knows about you (quite a lot), and uses all that data to sell ads to you and the many cohorts you are part of.

Netflix, on the other hand, operates a blue/iOS model. You pay, and you get content. You are the customer, and the content is excellent. YouTube, on the other hand, is worse in quality but free—if you don’t mind the data mining and the chance your children will be turned into white nationalists.

Expect this divide to deepen as the two models become increasingly incompatible. The NFL can operate in both worlds, since its advertising revenue streams don’t undermine the premise of its ticket and merchandise streams. The same isn’t true for a company like Apple, however. Tim Cook has promised us that Apple won’t harvest our data. “Privacy is a fundamental human right,” he said. But Apple receives $12 billion a year for making Google the default search engine for iOS. Apple will likely divorce from Google, even though it will cost them $12 billion a year, plus the billions it will take to build or buy their own search engine. Apple will not be able to monetize search to nearly the same extent as Google, since it can’t make Tim into a liar. But they can survive without Google. Just as they can get us to watch Murphy Brown at $15 million per episode (The Morning Show), they’ll be able to shove a search engine that’s 80% as good as Google down our throats. They own the rails. I know, you’re thinking they need to do a better job with maps first. Fair point.

RED AND BLUE SOCIAL MEDIA

Right now, social media is all red in terms of their approach to data vs. privacy. Free services, grossly exploitative, sometimes in ways we don’t even realize. In June 2020, it was revealed that TikTok scans the user’s clipboard every few seconds, even when the app is running in the background.19 The company promised to stop doing this (after a new iOS security feature caught it in the act), but if you used TikTok before the summer of 2020, you can assume that everything you’ve copied and pasted on your phone since you started using the app is now stored on a database in China under your name. Using Facebook might not get your personal data uploaded to the CCCP’s cloud, but given Facebook’s track record of protecting the privacy of its users, that’s only because the Chinese will be outbid by a Ukrainian teenager juiced up on bitcoin and looking to bring down democracy.

There’s a huge opportunity here for one or even several players to become the iOS of social media. The best opportunity to go blue, and capture a smaller but more valuable audience, is Twitter’s. Twitter has been trying to take the red/Android pill, but it isn’t working. And while management insists on losing money trying to exploit users by building another rage machine, those users are exploiting Twitter to build their own brands and businesses. It’s time for Twitter to come over to the blue/iOS world and start charging for value. Twitter doesn’t have the scale to compete on an ad model, and their ad tools are substandard.

After months of public lobbying on this front by a brave (and handsome!) NYU Stern professor of marketing,20 Twitter finally announced in July 2020 that it would “explore” a subscription model. The market loved it. Despite Twitter’s admission, in the very same earnings call, that ad revenue had dropped 23%, the stock was up 10%. If Twitter had a full-time CEO, they would have come to this conclusion in half the time.

I can save Twitter another year of “exploring” the subscription model. Subscription fees should be based on the number of followers. If @kyliejenner can earn $430,000 per promoted tweet, she’ll pay $10,000 a month to maintain her revenue stream, and @karaswisher (1.3 million followers), I’m pretty sure, would pay $250 a month. Verified accounts with <2,000 followers would remain free to maintain critical mass.

The B2B market alone would be huge, as Twitter has replaced PR, news agencies, and IR firms. What firm wouldn’t pay $2,000 a month to announce their new SaaS/diet/keto/hemp product? Twitter could take a 40% hit to top-line revenue over the short term, and triple their stock in the next twenty-four months as they move to subscription.

Going vertical would buttress the subscription offering. Twitter should acquire several of the remaining independent media properties (Lee, McClatchy, Condé Nast, Hearst, etc.) or assets from them.

The subscription model offers a free gift with purchase—identity. People are less awful when their name and reputation are attached. Ad-supported platforms are incentivized to allow bots and Russian interference, and to provide more oxygen to ideas that lack merit but are incendiary. Rage equals engagement, which translates to more Nissan ads. Remember that time when Netflix or LinkedIn really pissed you off? That was Twitter or Facebook.

Also, Twitter has the added benefit of being terrible at advertising. A move to a subscription model would forfeit dramatically less revenue than Facebook, which monetizes users at a higher rate than Twitter.21 Twitter could also hold on to much of their ad revenue during the transition phase, or even settle on a hybrid model that cleans up 90% of the carcinogens.

While Twitter is figuring this out at half-CEO speed, Microsoft should launch their own microblogging platform as a sub-brand of LinkedIn. If there is any doubt that media is nicotine (addictive) but advertising is what gives us cancer (tobacco), compare and contrast the most successful media firms of the last decade: Google, Facebook, Netflix, and LinkedIn. Two are tearing at the fabric of society, the other two … are not. The difference? Facebook and Google run on rage as an engagement model; Netflix and LinkedIn are powered on a subscription model (note: approximately 20% of LinkedIn revenues come from advertising).22

LinkedIn is much of the great taste of Twitter, an interesting feed full of connections and discovery, without the calories—bots pumping Tesla, death and rape threats, and antivaxers. LinkedIn is the social media platform we’re all hoping Facebook and Twitter would become.

RED AND BLUE SEARCH AND BEYOND

Search has also been red, but blue search is coming. Apple’s proprietary iOS search is inevitable. Expect Apple to buy DuckDuckGo or roll out their own soon. Beyond that, Sridhar Ramaswamy, former head of Google’s ad business, recently launched Neeva, a new Google competitor that will be using a subscription model. On the company’s website, one of the first links is for a bill of rights: “Your information belongs to you.” If you are willing to pay for it. Neeva recognizes the soft costs of Google may have created a white space for the anti-Google Google.

Likewise, the most innovative firm of the last decade seized on Amazon’s abuse of their customers (third-party retailers). Shopify’s value proposition is simple, and powerful: we are your partner. You control the data, the branding, and custody of the consumer. Brand building is the science of building goodwill that can be monetized. A lot of innovation is monetizing ill will. In this case, Amazon had abused their power to such an extent, they created an opportunity the size of Ottawa. Shopify’s is now worth as much as Boeing and Airbus combined.

Expect to see this divide emerge in more and more industries. Low-cost players from airlines to fast food will seek to take advantage of customer data and pass the savings on to their advertising resource units … oops, I mean customers. Premium players will wrap themselves in the blue flag of privacy and collect a nice margin for the courtesy of not exploiting their customers’ data.