3

Other Disruptors

The Disruptability Index

The Four have made the jump to light speed and enjoy monopoly/duopoly power that results in hegemony of distribution, cemented by cheap capital, rendering them difficult to challenge. However, it’s a big global economy, and there are other industries sticking their chins out. Again, the pandemic is accelerating these opportunities, making chins bigger and fists of stone fleeter.

The opportunity for disruption in an industry can be correlated to a handful of factors—a disruptability index. The key signal is dramatic increase in price with no accompanying increase in value or innovation. This is also known as unearned margin. The poster child for this is my sector, higher education. Consider a university lecture. Whether you are 19 or 90, you likely picture the same thing. An auditorium, an older person at the front, a group of young people in the seats, lecture, notes, teaching assistants. Almost nothing has changed in forty years, or even eighty. But there has been one dramatic change—the price. College tuition has increased 1,400% in the past 40 years.1 A red flag for disruption.

Another industry ripe for disruption: healthcare. It’s true that healthcare can claim significant quality improvements in certain sectors—advanced procedures, drug treatments, devices. But many outcomes, like life expectancy and infant mortality, have not improved dramatically. The consumer experience has not improved for most of us. Meanwhile, costs have exploded. The average premium for family coverage has increased 22% over the last five years and 54% over the last ten years, significantly more than wages or inflation.2

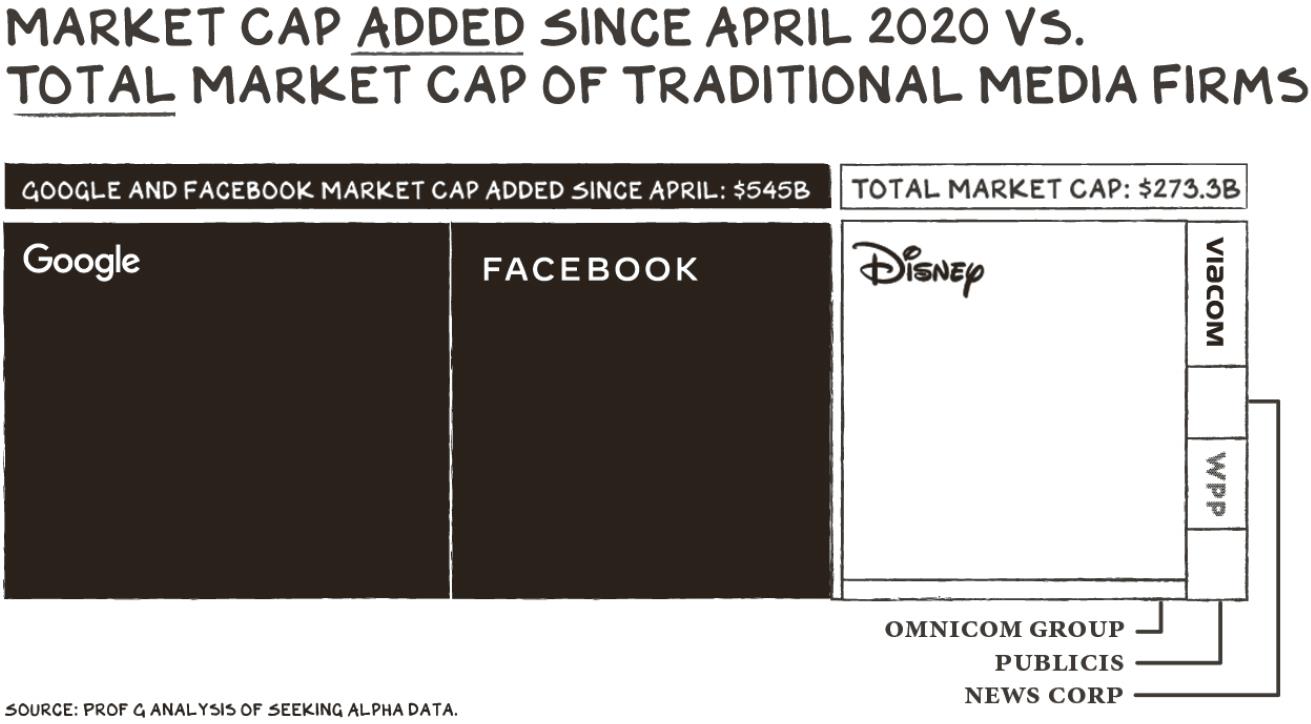

Another factor of disruptability is a reliance on brand equity divorced from the quality of the product, its distribution, or support. The transition from the Brand Age to the Product Age will erode the competitive advantage once possessed by many of the dominant firms of the twentieth century. Many companies sell essentially the same mass produced, mediocre product, but registered a premium due to a multigenerational investment in brand building. Digital technologies unleashed a torrent of innovation that brought differentiation, or not, to almost every consumer category. The temptation to ignore start-ups with better materials/ingredients, mastery of new platforms, distribution, or communities, and to default to brand building is best reflected in the near-irrelevance of the Masters of Yesterday—communications holding companies.

The chaser here is a reservoir of consumer ill will. Many firms and industries have fostered an adversarial relationship with consumers. Insurance comes by this naturally, as the business model consists of charging a consumer indefinitely and deploying resources to avoid ever delivering the benefit. Despite its noble mission and the talent the sector attracts, healthcare also suffers from a bitter aftertaste. Much of this is because our experience with healthcare is mediated through insurance firms and regulation, which create obstacles between need and care. Much of the industry centers its operations on the insurance payer and the doctor/institution provider. Disruptive health clinics, including One Medical and ZOOM+Care, and online pharmacy Capsule, are centering on the consumer/ patient.

Industries become ripe for disruption when existing players fail to adopt technological change to improve quality and value, as it may threaten their core business. A decent signal an industry is vulnerable is the presence of pseudo innovation—the addition of features that add no real value to the product; membership clubs that don’t deliver any real savings or convenience; movie theaters whose online ordering is more of a hassle than buying the ticket at the venue; colleges investing in luxury accommodations instead of educational resources. Those are the home remedies of a management team that knows the patient requires surgery but doesn’t want to endure real cost and pain.

The pandemic has laid bare the soft tissue of sectors whose major innovation has been price increases. The weaknesses of the U.S. healthcare system are a national tragedy. Among the myriad shortcomings, our reliance on centralized facilities, emergency room services in particular, might catalyze a tsunami of innovation around remote medicine and telehealth.

To survive, companies have scaled different dimensions of their business up or down with incredible agility. If a restaurant did a small amount of takeout, they’ve made it a priority, adjusting the menu, layout, and hours. In many places, third-party delivery services, including Seamless and Postmates, filled the need, took custody of the customer relationship, and now they have restaurants by the throat.

If your company was already adept at click and collect, as Home Depot was, the pandemic is more a speed bump than a meteor. If your store was not ecommerce competent (T.J.Maxx, Marshalls), you’ve suffered, as the world a decade from now (i.e., now) is unforgiving of sub-par direct-to-consumer offerings.

The Burning of the Unicorn Barn

Today’s tech “start-ups” are more often well capitalized, professionally staffed operations, with access to enough capital that, with some market receptivity, can become formidable forces in their sectors in months, compared to what used to take years or even decades. Until very recently they were typically headed by a charismatic founder, long on vision, shadowed by an operator.

There is always a tension between capital and management. However, it appears we have reached peak founder worship, a transition that is being accelerated by the pandemic. In the 1990s on Sand Hill Road, founder-CEOs at tech start-ups were considered necessary evils—crazy, eccentric young white men with a vision who would eventually be sidelined as an older, more experienced executive would be brought in to scale the firm.

The power resided with capital—with the slightly older, much less eccentric white men on Sand Hill Road. And it was verboten for a founder to cash out of a company before the VCs managed to get their own liquidity. Founders’ equity was dead equity until an acquisition or IPO.

I tried bucking the rules and did a secondary offering at one of my early companies, Red Envelope—I sold a million dollars of my own stock to an outside investor. Within 24 months, the company was going sideways, and I was forced to reinvest that full million dollars or be washed out by my lead VC, Sequoia Capital.

However, in the late 1990s and early 2000s the power began to swing back toward founders. Entrepreneurs started to be seen as the secret sauce within companies. Why? Two reasons: Bill Gates and Steve Jobs. Bill Gates was the first to prove the same person could found a company and take it to $100 billion in value. Gates grew Microsoft to $600 billion over 14 years.

Jobs built Apple to $600 million in value over the company’s first five years. But that was then, and he was forced out in 1985 on the basis of being eccentric, stubborn, and mercurial. There are few things that indicate an information age jerk more than a CEO wearing a black turtleneck and telling people to find their passion. However, Jobs was in fact a genius, and none of the gray hairs that followed—Scully, Spindler, or Emilio—could grow the company. Twenty years after Jobs returned to Apple, the firm had increased in value by 200 times.

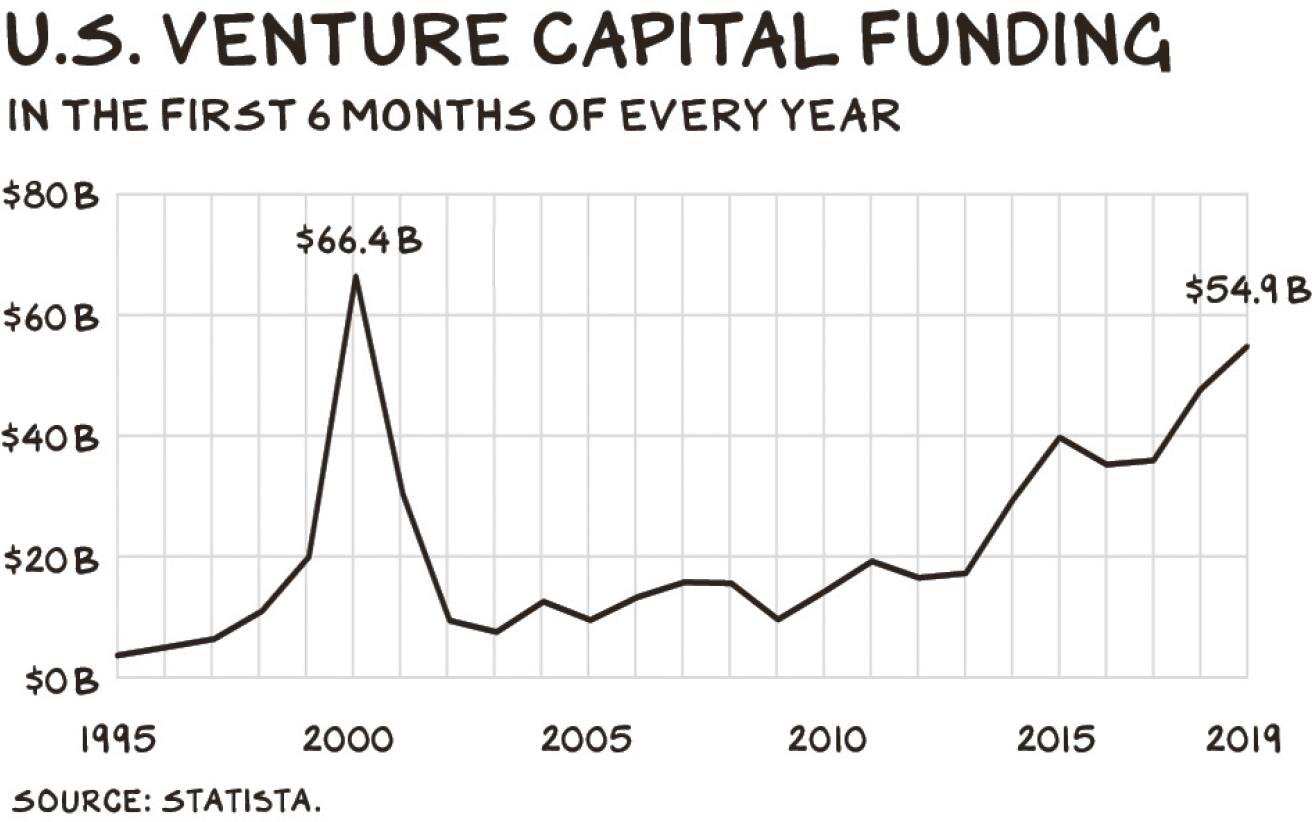

With those proof points, founders became more assertive. And as the tech boom roared on, supply and demand shifted in their favor. In 1985, the Valley was full of geniuses with world-changing ideas, but capital was hard to come by. In 2005, we weren’t making that many more true geniuses, but available capital began to increase exponentially. VCs jockeying to fund successful founders devised term sheets that included secondary sales, two-class shareholder structures, and other founder-friendly terms.

The situation would only get more out of balance. The NASDAQ quadrupled in ten years, everybody wanted in on the boom, but the pool of talent has not kept pace. Markets abhor a vacuum, and this one was filled by fake prophets, who’ve managed to coax a flock into thinking they are the next Jesus Christ of our economy—the next Steve Jobs.

Two other factors pushed the founder-worship era to greater heights. The sheer amount of capital meant that companies could pursue capital-driven growth strategies. That is, they could buy market share by selling at a loss, while raising subsequent rounds of capital, at increasing valuations, due to growth that was fueled by cheap capital. And with all this private capital available, companies could stay on this money-losing merry-go-round longer before going public (and subjecting itself to the scrutiny of the public markets). The number of U.S. IPOs has declined 88% from 1996 to 2016. It also takes much longer for companies to get public. The average age of a company up for IPO increased from three to eight years over the last 20 years. The two dynamics fed on one another, and “visionary” founders feasted. A new species of start-up emerged: the unicorn.

ENTER THE UNICORN

Way back in 2013, when billion-dollar start-ups were actually rare beasts, venture capitalist Aileen Lee coined the term unicorn to describe them.3 She found 39 such companies and reported that new ones came along at a rate of about 4 per year. Estimates put the number today at around 400, with 42 born in 2019 alone.

Not every unicorn runs on hype, though several bought into the philosophy of “fake it till you make it” and achieved only one of those things. From criminality (Theranos) to consensual hallucination (WeWork) to just overvalued businesses (Casper), these are companies that relied on a combination of sycophantic business media, FOMO-infected investors, and cynical faith that multiple rounds with stepped-up valuations would create enough momentum to carry the firm through a sale of their shares to a greater fool.

It’s always going to be “different this time.” People love WeWork and Uber as I loved Pets.com and Urban Fetch. A 60-pound bag of dog food and a pint of Ben & Jerry’s delivered the next day or hour for less than cost was awesome, except for shareholders. Value is a function of growth and margins. As they did in the ’90s, many of today’s unicorns have deployed massive capital to achieve the former while not demonstrating the value proposition to achieve the latter.

The pandemic finds the start-up world at a unique juncture. Never before has there been so much capital and so many built-out, well-positioned companies, just as the mother of all accelerants is creating disruption opportunities left and right. The difference this time is that most unicorns will survive in one form or another, but the value destruction may be greater, as the valuations have become so extraordinary.

SOFTBANK’S $100 BILLION UNICORN BUFFET

Foremost among the suppliers of cheap capital has been SoftBank, whose $100 billion Vision Fund was disruptive on several levels. The case study we’ll be teaching for decades in B-schools around the world about the Vision I disaster writes itself. The strategy was (wait for it) capital as a strategy. Specifically, more of it, so you could win deal flow and be the fuel that helps portfolio firms make the jump to light speed, leaving competitors behind and befuddled. The pitch from SoftBank to entrepreneurs was simple and compelling. “You aren’t thinking big enough. We want to invest three times your planned raise, and if you don’t do a deal with us, we’ll inject these liters of growth hormone capital into your biggest competitor.” Well, okay then.

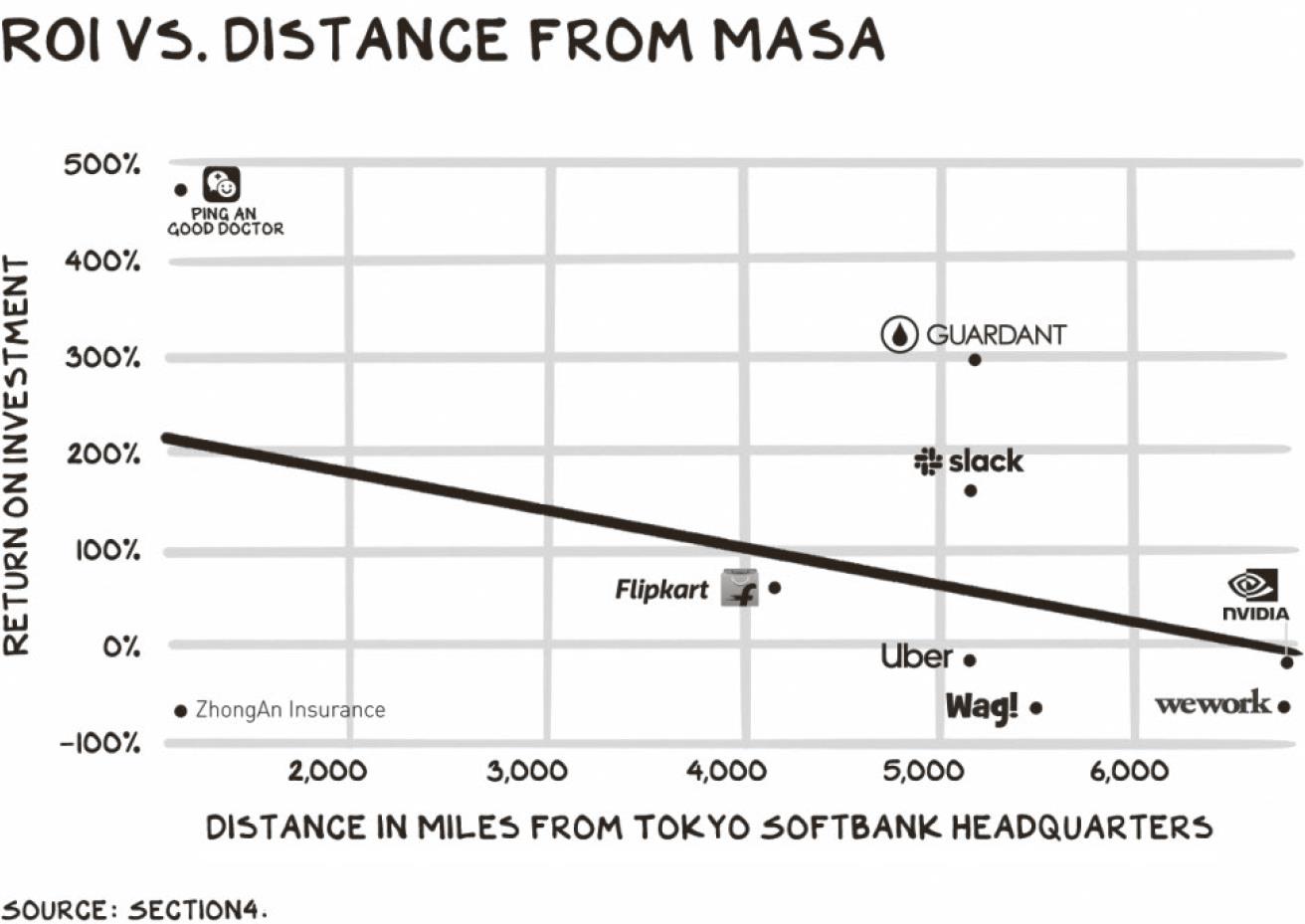

Capital is in fact a weapon in private equity, where only a few firms can bid for the truly great, proven assets with enormous cash flows. However, in venture, and growth, the secret sauce is dislocation, a market ripe for disruption, and crazy genius founders who are too stupid to know they will fail. When your ability to deploy billions into a concept becomes the priority, as it does when you have $100 billion to deploy, your returns go down. This is evident across SoftBank’s portfolio.

My NYU colleague Professor Pankaj Ghemawat published gangster research showing business and trade are, despite rumors of the death of distance, a function of geography. A retail store’s profitability is correlated with proximity to HQ. Sequoia Capital was the lead investor in my second firm, and the partner on our board told me a key tenet was they would not invest in a firm the partner could not drive to. Note: as they’ve raised bigger funds, tier-1 VCs make investments all over the world but often open local offices.

Masayoshi Son and Adam Neumann would agree to meet in-between their 13 time zones (I think that’s Hawaii). Similar to when the Japanese acquired U.S. movie studios and golf courses in the 1980s, SoftBank will leave with fewer yen than it came with. If you found the previous sentence uncomfortable, racist even (as I initially did), you’ve fallen victim to the same monoculture PC virus infecting our universities. Japan did buy U.S. golf courses, and their currency is in fact the yen.

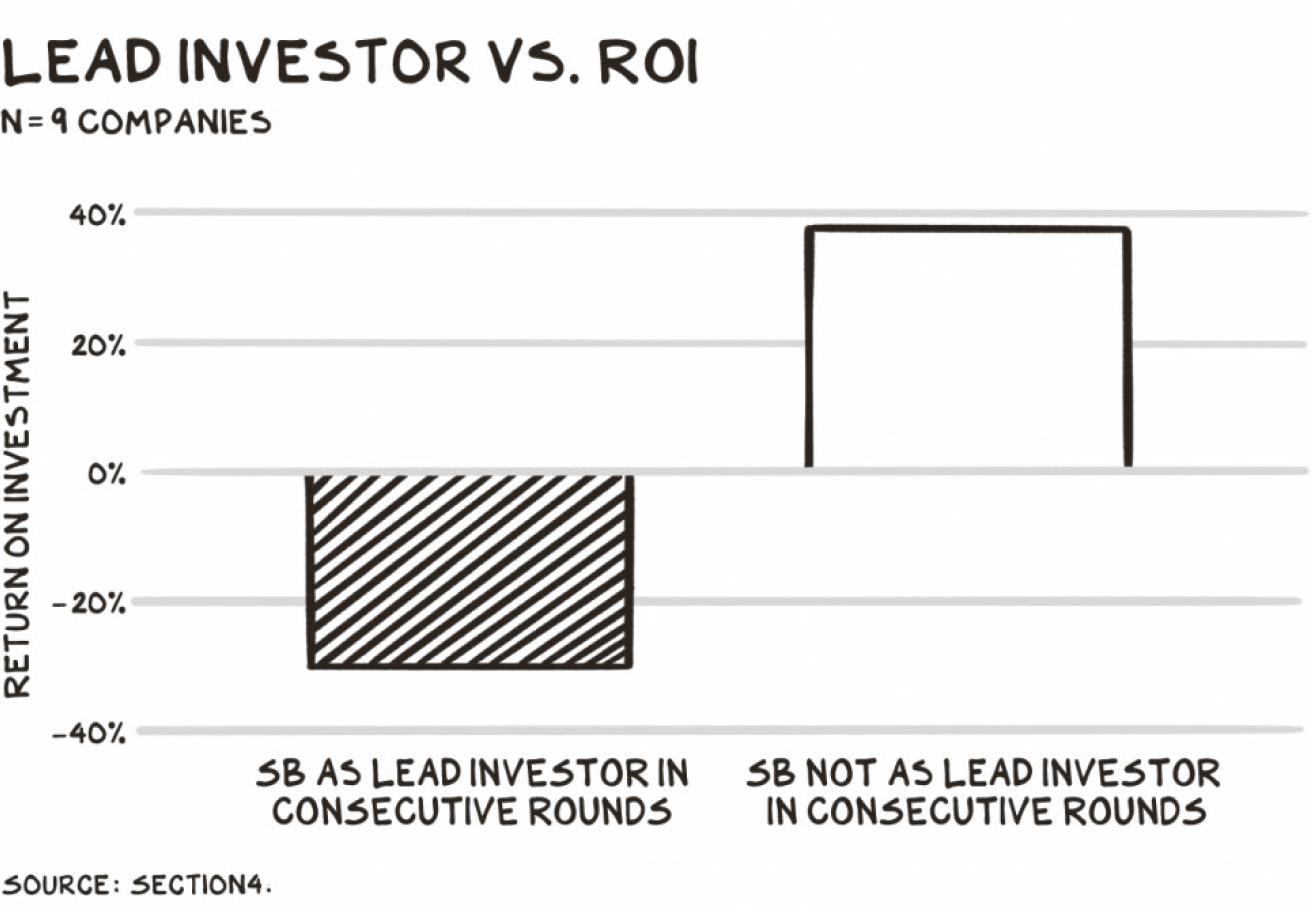

Another tenet of venture, expressed by every investor I’ve raised money from (General Catalyst, Maveron, Sequoia, Weston Presidio, JPMorgan, Goldman Sachs, and others), is they do not like to lead subsequent rounds. Good investors resist the temptation to “smoke their own supply” (lead multiple rounds) and require third-party, arms-distance validation of the firm’s value here and now. SoftBank was the only lead investor in WeWork, through multiple rounds, since 2016.

Ironically, the real damage on the capital side will be on SoftBank employees, as they own common stock in Vision I. Saudi Arabia Public Investment Fund and Mubadala own preferred stock that captures a 7% (preferred) return each year, siphoning returns from the few winners in the portfolio. So, Vision I has pneumonia, but the common equity holders in Vision I are on a ventilator.

The availability of capital is not correlated with the availability of good places to invest the capital. Good investments—disruptive start-ups with the potential to grow into sustainable multibillion-dollar enterprises—will always be scarce. The alchemy of crazy brilliant entrepreneurs who have unique visions of how new technologies can solve problems or make our lives better, coupled with fat and happy incumbents, is a story of hunting for unicorns. But capital is wealth in motion, and like the sharks that deploy it, it has to stay in motion—or it dies. So, when good companies seem to have retreated to the forest, capital will convince itself that a bear is a unicorn.

YOGABABBLE

Too much capital and not enough talent is the cue for the rise of the charismatic founder. All things being equal, a charismatic founder is an asset. They not only attract capital, they attract great employees, sell the product, and provide a halo for the company when it faces threats. But in a capital-soaked environment, nobody has time or interest in the serious analysis of financial statements or diligence on a start-up’s idea. It’s easier to invest hundreds of millions with the guy with long hair who has a plan to live forever and (presumably sooner) solve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, as he’s a “visionary,” and we (capital) “back people, not companies.”

The charismatic founder speaks in a characteristic dialect: yogababble. That’s our term for abstract or spiritual-sounding language in IPO’s S-1s, a company’s formal disclosure before going public. Besides listing the required financial disclosures, the company amplifies the yogababble with the power of the corporate communications executive. This is an affliction at real companies (according to LinkedIn, there are more corporate comms personnel working for Bezos at Amazon (969) than journalists working for Bezos at The Washington Post (798)), but it becomes a core competency at the charismatic-founder, capital-driven growth company. When firms are still searching for a viable business model, the temptation to go full yogababble gets stronger, as the truth (numbers, business model, EBITDA) needs concealer. When I show up at MSNBC, they put some crazy foundation syrup in a plastic bottle attached to a hose, ask everyone to stand back, and (no joke) spray my face and head as if the makeup artist were the last line of defense against the reactor 4 at Chernobyl. And I look awesome … for a while. But similar to yogababble, the concealer wears off.

Yogababble basically translates to “We are fascinating people,” rather than “This is a solid company that makes sense for the following reasons.”

We recently looked at the S-1 language of a bunch of tech firms and made a qualitative assessment of the level of bullshit—their willingness to depart from the fundamentals of balance sheets and flee into the realm of the mysterious. Their attempt to captivate by dimming the lights, as it were. Then we looked at their performance one year post IPO—what happens when the lights come on. We believe there is an inverse correlation between the two, and that may be a forward-looking indicator for a firm’s share performance.

Yogababble scale 1–10:

1/10: I’m a professor of marketing who likes dogs.

5/10: I’m the Big Dawg.

10/10: I am a Spirit Dawg that unlocks self-actualization.

Zoom

Mission: “To make video communications frictionless.”

This is accurate. Zoom is a video communications company. It offers less friction, as demonstrated by a higher NPS score (62) than Webex (6).

Bullshit rating: 1/10

Stock return 6 months post IPO: +122%

Spotify

Mission: “To unlock the potential of human creativity by giving a million creative artists the opportunity to live off their art and billions of fans the opportunity to enjoy and be inspired by these creators.”

OK, sort of. But hard to see how Celine Dion is unlocking human creativity.

Bullshit rating: 5/10

Stock return 1 year post IPO: +9%

Peloton

Mission: “On the most basic level, Peloton sells happiness.”

Nope, similar to Chuck Norris, Christie Brinkley, and Tony Little, you sell exercise equipment.

Bullshit Rating: 9/10

Stock return 1 day post IPO: –11%. Granted, after being mostly even for the first 6 months since its IPO, Peloton has shot up during the pandemic as people move to working out from home.

I can relate to the mix of hubris, success, and Christ complex that leads you to believe your business efforts deserve a vision worthy of your genius—if not to distract you and your investors from the reality of how hard it is to build an entity that takes in more money than it spends, while growing. When the board, CEO, and bankers transfer the vicious hangover to retail investors, the distraction becomes malfeasance.

My new firm, Section4, was going to “Restore the Middle Class.” My colleagues rolled their eyes so hard I wondered if they’d been coached by my twelve-year-old son. Then we were “NSFW Business Media” or “Streaming MBA.” We’re trying to figure it out. Eventually, I told the board we had assembled a group of talented people, and will deliver elite business school marketing and strategy electives for 10% of the price. We’ll go from there. I’ve come to the realization that we’re not bringing joy to the universe. We are not Chipotle.

THOROUGHBRED VS. UNICORN

As we enter the last quarter of 2020, VCs are raising record funds and valuations appear to be ripping higher after a brief (hot-minute) pause during the first half of 2020. But while funding has survived and even accelerated, I believe there will be an enduring impact on valuations. Firms cast as innovators have registered valuations that will be unsustainable when the markets realize. Fine print on my predictions, however: in March 2019, in front of a large audience at SXSW, I predicted Tesla’s stock would decline from $300 to less than $100. It began 2020 at $430, and by August, surpassed $2,000 per share. In any event, it’s possible the market will continue to overvalue recent IPOs, but to me many of these companies have valuations that don’t make sense.

A company can be a good business with solid prospects valued at $200 million, and an embarrassment to the markets valued at $1.1 billion. Casper went public in February 2020. Casper is a nice brand in a growing market—the sleep economy. Sure, call it that. The incumbents, mattress stores, are the stuff of Tarantino movies: you expect a guy with a sawed-off shotgun to roll in and take hostages. One of the key factors in a company’s success isn’t the company itself but the incompetence of the incumbents. It appears that hundreds of people were stirred from their slumber with the same vision. There are 175 online mattress retailers besides Casper. (Think about that.)

Casper’s numbers illuminate signals of a frothy economy: firms that should be sold in the private market doing a kabuki dance (“technology” mentioned over 100 times in a prospectus), asking people to suspend their disbelief until the founders, VCs, and bankers sell their shares and get their fees. Here too, yogababble plays a starring role: “We believe we are the first company that understands and serves the Sleep Economy in a holistic way.”

However, when reviewing the financials, it doesn’t feel holistic or especially relaxing. On a per-mattress basis, Casper captures $1,362 in revenue. But it spends $761 on the mattress, $480 on sales and marketing, and an impressive $470 on administrative overhead. That’s a loss of $349 per mattress. Does that sound like a billion-dollar business? It did to its venture backers, who bid it up to $1.1 billion in 2019.

I said Casper shouldn’t go public and that if it did, the stock would shed 30%+ in the first year. In fact, I told the management team to sell in 2017. My advice was to sell to a retailer, like Target (one of their investors) or any middle-aged retailer looking for Botox, as Jet was to Walmart. The acquisition would provide the acquirer momentum in the sleep category, domain expertise in direct to consumer, and Casper would have a better chance of achieving the scale they don’t have and need. Did they listen to the Dawg? They did not. Casper went public in February 2020, squeezing out the door at a valuation below their most recent funding as a private company, $1.1 billion—and fell 30% in the first week of trading—where it sits as I write this in August 2020.

To be fair, Casper saw an opportunity (so did the other 175 online mattress retailers) and pursued it with a combination of tech and narrative (mostly narrative). But it has struggled to develop any real differentiation, instead reverting to the Brand Age, and trying to wrap an undifferentiated product with aspirational associations.

When the Smoke Clears

So, what does the start-up environment look like for would-be disruptors that can offer more than a dreamy founder with a good rap? Abundant capital remains, and the life cycle of a start-up has become a closed loop for a lot of companies.

Private investors—traditional venture capitalists, but also institutional investors whose appetite for risk has increased with their assets under management—are signing up for more and larger financing rounds, and using the public markets as an exit, instead of as a financing event.

Abundant capital permits a heft of financing rounds previously only available in the public markets, and a robust secondary market provides liquidity to shareholders. A major reason we are seeing so many unicorns is companies stay private longer. This has the benefit of reduced overhead and regulatory compliance costs, as well as less scrutiny. The company captures more of the upside for its private-market backers.

Another change has been the increased potential for another form of high-return exit—acquisition by one of the mega tech companies like the Four. Also, ten or twenty years ago, exit by acquisition was typically a consolation prize for a venture-backed company. It could certainly make the founders money, but the real cabbage and fame was in an IPO. Now, just as the private capital markets can match the public markets, big acquirers can as well.

Apple has cash worth 200 unicorns ($200 billion) on its balance sheet. Google has $120 billion. But it’s not just that the Four can pay IPO valuations—their dominance of markets (and ability to move aggressively into new ones) makes their offers difficult to refuse. The July 2020 congressional antitrust hearings revealed that Mark Zuckerberg had made Instagram an offer they couldn’t refuse (“join or die”). The founders and investors typically do well in an acquisition. The 12 unicorns that exited in the first half of 2020 did so at a 91% premium to their last private valuation.4 However, it’s bad for the economy and job growth, as the ecosystem is less robust and the consolidation of the market makes it increasingly difficult for start-ups to get out of the crib.

The pandemic may birth the best-performing IPO class in several years, as the market’s valuations are based on a firm’s perceived performance 10 years ahead. The same is true of the downside: as firms that are struggling are issued a do-not-resuscitate order from the markets and are valued at their (remaining) cash flows. The cheap capital economy that offers disruptors the opportunity to pull the future forward sucks oxygen from the incumbents, who are forced to retrench (layoff, cuts in CapEx) as the new kids on the block can lean into new investments and hiring. It becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy—incumbents are forced to play defense in order to maintain profits their investors have become addicted to. This further weakens the incumbents, giving the disruptors more momentum as market share gains become easier with sector elders weakened.

So what’s the recipe of disruption? First, the industry you are entering is the crucial context. Sectors that have raised prices faster than inflation, without an equivalent increase in innovation, are the sectors where disruption is more likely. The DNA of a disruptor can be mapped via the disarticulation of key attributes of firms that have added hundreds of billions in stakeholder value in years vs. decades.

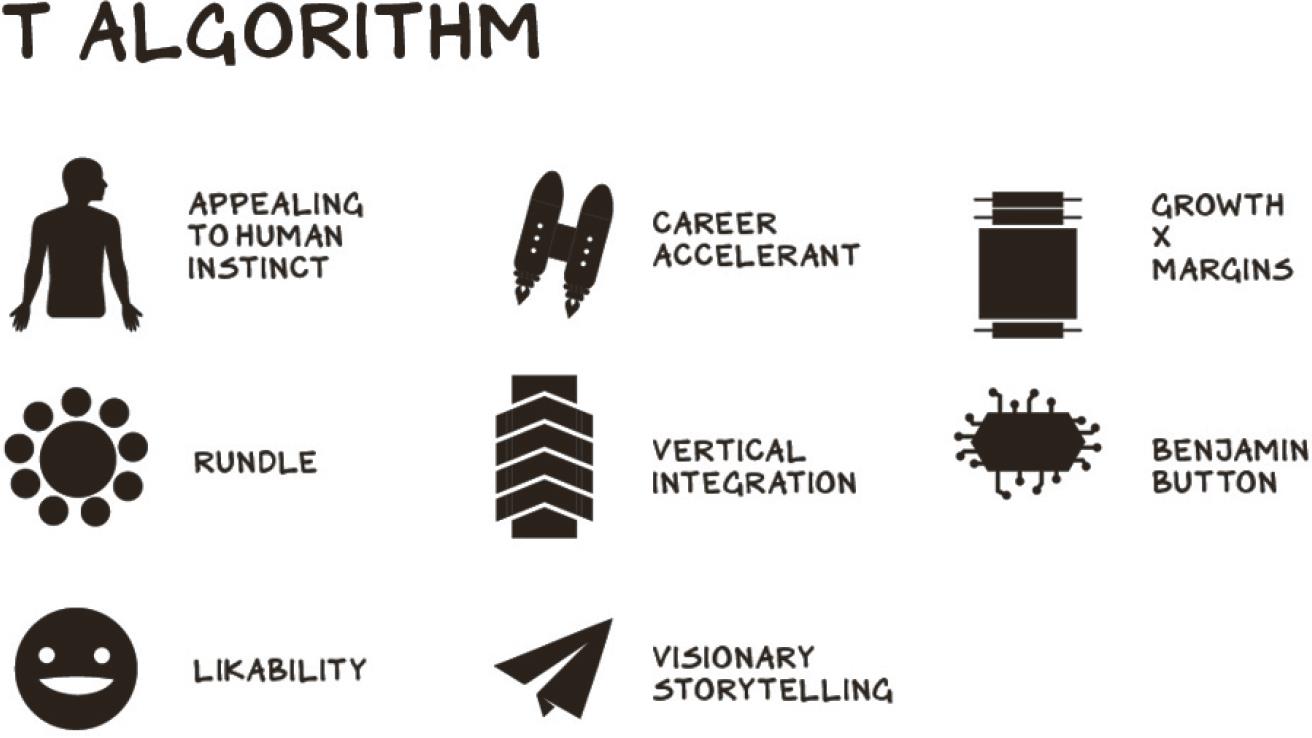

The T Algorithm, which I developed in The Four, and have refined since, defines some of these key qualities. The T stands for “trillion”—these are the traits that give a company a chance at a trillion-dollar valuation. The eight elements of the T Algorithm are as follows:

- Appealing to human instinct

- Accelerant

- Balancing growth and margins

- Rundle

- Vertical integration

- Benjamin Button products

- Visionary storytelling

- Likability

Appealing to human instinct. As humans, we are hardwired to share a set of biological needs. The most powerful firms have found ways to serve and exploit these instincts. We can break them down into four main categories, going down the torso. First, the brain instinct: we are constantly looking for answers to help explain our experiences and the world around us (Google). Bargains (Walmart) and rational claims (Dell, Microsoft) appeal to the brain. Margins tend to be small in brain-appealing businesses—there is one lowest price or fastest processor. Second, the heart: we have an innate desire to connect with the people around us. “Choosy moms choose Jif.” Caring for those around you makes you more willing to spend. Third, the gut: ever since our caveman days, we have worked to accumulate the most resources for the least output. Our modern lives depend on a steady supply of stuff. Finally, the genitals: one of our most primordial instincts, that of propagating our species. We are motivated to buy products and services that make us feel more successful and good-looking, so we can attract better mates. We pay irrational margins for products that improve our sex appeal. Contrast rational companies Walmart and Amazon (the brain and the gut) to Ferrari and Louboutin (the genitals).

Accelerant. A firm that serves as an incredible springboard for a person’s career. Other than intellectual property or defensible IP, a firm’s ability to attract talented employees is one of the most important contributors to success.

Balancing growth and margins. Today’s most successful firms maintain explosive growth and strong margins. Typically speaking, margins are in conflict with growth. There are some companies that take very low margins, like Walmart, and as a result are able to grow faster because they don’t charge much additional margin for their value-add. In contrast, if a firm has high margins, it usually has lower growth and lower potential for scaling. Only some exceptional firms, like the Four, are able to combine high growth with high margins.

Rundle. A bundle of goods and/or services that justifies recurring revenue. This strategy exploits one of our key weaknesses as human beings: we are terrible at estimating the value of time. Firms that convince consumers to enter into a monogamous relationship with them are positioned to accumulate more value over time than firms that interact with consumers transactionally. An example of a rundle: Apple currently offers music and streaming video subscriptions, but it could bundle both of those products, plus news, plus annual iPhone upgrades, into a bigger recurring revenue bundle.5 Disney could bundle Disney+, parks, cruises, and other perks into several tiers of packages based on recurring revenue, or a multiple-product subscription.

Vertical integration. A firm’s ability to control the end-to-end customer experience by controlling as much of the value chain as possible. Companies that control distribution reap huge benefits. Take Apple. By controlling the App Store and the iPhone, the firm takes a cut of every dime spent on third-party apps. It sells its products through 500 brand temples known as Apple Stores, and over the next two years will shift to designing all its key silicon in-house.

Benjamin Button products. Products or services that age in reverse (get more, rather than less, valuable to users over time) due to network effects. Unlike traditional products, like cars or toothpaste, which depreciate in value almost immediately after purchase, Benjamin Button products get more valuable with time and with additional users. For example, on Spotify, more artists means more users, which means more personalization of playlists, including sharing your playlists with friends, which makes it that much more fun for you to be on Spotify, which draws more artists, etc.

Visionary storytelling. The ability to articulate or demonstrate progress against a bold vision for the company to shareholders and stakeholders. Telling a compelling story unites employees and attracts top talent and cheap capital. But it’s not enough only to inspire—the firm has to actually deliver on its promises.

Likability. The ability of a company’s leaders to insulate the firm from government and media scrutiny, strike favorable partnerships, and attract top talent. Consumers tend to personify brands, and those that can take on positive, animate characteristics tend to reap outsized benefit.

THE SHINIEST UNICORNS IN THE HERD

Using the T Algorithm, and considering the disruptability of their industries, here are some companies, both public and private, that I’m following:

Airbnb. In 2018, I said Airbnb was the most innovative consumer tech firm of the year, monetizing the largest asset class in the world (U.S. real estate) without owning or maintaining the asset—this enables it to spend more on customer acquisition in social and search, resulting in more web traffic than hotel peers. Unlike Uber, Airbnb is monetizing a fallow asset vs. drivers’ need for flexibility and their willingness to accept low wages and no benefits.

The pandemic’s immediate impact on Airbnb was a significant decline in revenue, but its asset-light model means the disruptor’s costs can be variabilized, since unlike hotel firms, they have no interest on mortgages, upkeep costs, or expensive employee benefits costs. In sum, Airbnb can roll with the punches, while peer hotels just get punched. After a 67% drop in revenue in Q2, Airbnb saw more nights booked for U.S. listings between May 17 and June 3 than the same period in 2019, and a similar boost in domestic travel globally.6 Airbnb is expected to file to go public before the end of 2020, and we believe it will likely be one of the most valuable firms in travel/hospitality on the offering. The space demands global supply and demand (people from all over the world book places to stay in Austin), and Airbnb has it. This is the definition of a moat.

Brooklinen. In 2015, one of my students asked me to invest in his business. He was sourcing cotton in Egypt, milling it in Israel, and then landing a set of sheet sets, duvets, and pillows in Brooklyn for $79 that he would sell for $129. The value proposition was clear: bedding that sold elsewhere at $400, for a lot less. The Fulops, a husband-and-wife team, had secured orders online before the cotton was purchased. This is the definition of good marketing and business strategy—finding products for your consumers vs. finding consumers for your products (piling stuff high in a store and hoping people buy). Streamlining the supply chain to offer better value on a better product is gangster. Today, their company, Brooklinen, is profitable, and sold to Summit Partners in March at a multiple of revenues—rare for retail. Nice sheets, too.

Carnival. Not a disruptor, but nonetheless a company to watch post corona. In the months before the pandemic, Carnival was trading around $50 a share, but in August, it was under $14. For good reason—the company’s operations are entirely shut down, until at least October 31. But there will be a post-pandemic world, and as long as we keep making old people, cruise lines will be fine. The cruise industry was the fastest-growing segment in the leisure travel market, with demand increasing 62% between 2005 and 2015. And cruisers just want to keep on cruising. Back when it was an option, 92% of cruisers said they would book a cruise as their next vacation. What’s powering that is a combination of demographics (more old people) and a classic value proposition: edited selection. Rookie marketers think people want choice. Consumers don’t want more choice, but more confidence in the choices presented. Choice is a tax on time and attention. Customers want someone else to do the research and curate the options for them. You could try to merchandise a better itinerary on a boat through Southeast Asia (hotels, meals, activities, planes, trains, cars), or you can let Carnival figure it out for you.

The stock has taken a substantial hit, and there’s a chance the pandemic will last longer than Carnival can stay liquid. But the stock triples if the firm survives, making it an interesting cyclical vs. structural trade. The demand destruction in cruises is cyclical, vs. airline travel or restaurant patronage, which is likely structural, as we’ll be home more for a long time.

Lemonade. A quintessential 2020 disruptor. (Disclosure: I’m an investor.) The firm’s sector—insurance—has not changed its offering in decades and has amassed an ocean of consumer ill will. Digitizing the supply chain sheds expensive distribution costs (like insurance salespeople), and the firm is using artificial intelligence to achieve better loss ratios (i.e., better risk assessment). Incumbents don’t seem worried, as Lemonade is now just a small renters-insurance operation, barely nipping at the heels of the big players. But even a small improvement in customer experience is an edge, and the capital markets will provide Lemonade the resources to turn that edge into dragon stone.

Lemonade appeals to the brain—you can get insurance quotes in minutes. It meets our desire for answers and for efficiency of information, similar to Google. It also, stay with me here, foots to our instinct to procreate. Herding with “innovators” is similar to hanging with the cool kids at lunch as you hope some of that sheen makes you more attractive to others. And Lemonade has a rundle, a recurring revenue relationship with customers, who pay monthly premiums. Its likability is strong—the CEO has deftly incorporated a social mission that refunds unused reserves for claims to a charity of the customer’s choosing. The net/net is higher NPS compared to legacy insurance providers including State Farm, Liberty Mutual, Allstate, etc. In June I said that Lemonade’s IPO would be a “monster,” and it was the best performing IPO (to date) of 2020, repricing up just before it issued, and still increasing 140% in the first two days of trading.7

Netflix. Streaming video during a pandemic is a good place to be. The space has attracted incremental investment that rivals the defense budgets of G7 countries. But Netflix has made equally staggering investments over the last decade. The streaming video firms accomplished something only Amazon has managed in recent years: first they achieved a near-zero cost of capital through exceptional storytelling, then they maintained that superpower while shifting from a growth story to a margin story. This is hard. It’s relatively easy to get super-low-cost capital when you’re growing like a weed. The challenge is when the growth peaks and capital markets begin looking at the bottom of the income statement.

Netflix has used that capital not just to build out its streaming infrastructure (which is impressive enough), but to recast what “value” means in entertainment: For every dollar per month, the consumer receives a billion dollars’ worth of content. A $10 movie ticket to a $100-million movie gets you a mere $10 million per dollar, and you can only access it for two hours. Netflix gives you a 100 times the value with on-demand access in a theater that has captured more capital investment and innovation than any chain of multiplexes: your living room.

It’s unlikely you will watch 1% of what’s available (note: I’m trying), but the most prevalent application of AI (the Netflix recommendation engine) brings a Facebook/Google-like cocktail of scale and targeting that makes the Los Gatos firm the Herschel Walker of tech—enormous, yet fast. Netflix innovates around the notion of scale better than any content company. At its production facility in Madrid, the firm has assembled a content machine 10,000 people strong. Yet the model is such that Netflix Madrid will produce the content of an even larger operation. Same story, screenwriting, cinematography, set, and costume design, but several scenes shot with the “it” actors from various regions produces more relevant content, faster. Again, Herschel Walker. Netflix has busted free from the narcissistic U.S. belief that the world wants to keep seeing American actors. No, they want American scale and cheap capital with regionalized talent.

In 2011, I bought a lot of shares (for a professor) of Netflix at $12 a share. That’s the good news. The bad: I sold at $10 a share to take the tax loss and never repurchased. The shares hover around $500 as I write. I want to clone myself, find a time machine, go back in time, and slap myself in the face. But I digress.

Okay, what about a firm you likely haven’t heard of?

One Medical. I think One Medical is a disruptor and has many of the features that signal potential for extraordinary returns. Some of the weapons of mass entrenchment in healthcare (like HIPAA compliance) have been somewhat eroded due to the urgent need to streamline healthcare delivery. Just as retail added hundreds of billions in value via the adoption of multichannel, healthcare’s embrace of smartphones, cameras, and speakers will unlock staggering value.

Imagine you’re camping and your kid steps on a wasp and his foot starts to swell. You immediately want to pull someone up on your phone and then have them give you the confidence to say, “Okay, you need to pack up the tents and get here.” Or say, “No. You’re fine. Wash the area with soap, and then soak his foot in that cold mountain lake behind you. Tomorrow drive into town and get this antihistamine, the prescription has been electronically sent to a pharmacy geolocated to your phone.” Less cost, more time with family, and peace of mind.

The aspects of healthcare that stands to recognize the greatest benefits of Covid-inspired innovation are those where change has been resisted through inertia. Innovative service delivery is one such area. One Medical offers healthcare through the channels the industry has resisted—specifically, the handheld phone. The technology removes friction, costs, stigma, and increases privacy.

Peloton. This rally will outlive the coronavirus. The $1 billion revenue firm defines the T Algorithm: I initially felt the firm was overvalued, and then … Covid hit.

YOY growth of 69%. Recurring revenue is at the heart of its business model, and there’s nothing like a $2,000 bike to make a $39 monthly fee seem reasonable. Benjamin Button (network) effects are at work—the more customers, the greater the benefits from the (rabid) community.

Peloton is approaching 1 million connected subscribers, with a Netflix/Prime-like 93% retention rate,8 better margins than Apple, and vertical control over its offering. Because it can leverage its instructors across so many more customers, Peloton is a career accelerant for its instructors, whom it poaches from the likes of SoulCycle and Equinox, offering triple the compensation, equity, and a platform that offers exposure to thousands online.

Investing Apps: Public and Robinhood. Financial services is an industry ripe for disruption, and the pandemic has boosted personal stock trading activity as many people have more time on their hands, and an additional $1,200 in their bank accounts. Robinhood is the big name here, and when it introduced commission-free trading, established players were forced to respond and abolish commissions. This likely prompted the merger of industry leaders Charles Schwab and TD Ameritrade. Robinhood also added fractional share trading, letting its mostly young user base buy into expensive stocks they might not otherwise own. More than half of the app’s users are first-time investors, and the interface is gamified in a way that encourages more time on the app. Splashy visuals, random rewards (badges, high-yield checking accounts unlocked if you tap on this icon 100 times, etc.), the dopa hits of a video game—or casino. The company embodies big tech’s evolution from innovation (better products) to exploitation (depressed teens, gamification, addicting young people to variable rewards). Why not, it works for Facebook. Gamification is an exploitation algorithm, as is the enragement algorithm that controls the Facebook newsfeed.

Public is taking a different approach to commission free, user-friendly, fractional-share trading apps. (Disclosure: I’m an investor.) But Public views itself as a social network that provides stock trading, and emphasizes communication among users in public forums and private chats. At sufficient scale, a network of connected users becomes an asset, and one that—at a certain scale—competitors will struggle to match.

How about a firm that is all show and no go?

Quibi. The most compelling content from Quibi is … Quibi. This debacle is worth watching, as it illuminates several insights about our ecosystem. First, tech entrepreneurship is a young person’s game (ageist … and true). One of Quibi’s advertised strengths was the leadership of Meg Whitman and Jeffrey Katzenberg. And why not? They are first-ballot Hall of Famers in tech and storytelling, respectively. However, to my knowledge, there’s never been a successful media-tech firm founded by people in their sixties. The young brain is crazy, creative, and willing to work 80 hours a week—young people think they’ll live forever. People in their sixties are not blessed or cursed with any of these things, which makes them decent leaders, great mentors, and lousy entrepreneurs. Second, you can’t compete against the Four without either a 10 times better product or access to capital that dwarfs the incumbents. I’m sure $1 billion (increased to $1.75 billion) felt like a lot to Hollywood veteran Katzenberg when he signed on. However, at Amazon, $1.75 billion is “a pretty good day,” and it’s what Netflix spends on original content in 5 weeks.9

Shopify. Shopify is the most impressive tech company of the last decade, and perhaps the most courageous. The Canadian firm recognized the huge white space to become the anti-Amazon Amazon. Similar to Amazon’s Pay and FBA (Fulfillment by Amazon) products, Shopify provides payment and fulfillment for third-party retailers. Unlike Amazon, however, Shopify’s CEO could honestly tell Congress it doesn’t use the data it collects from third-party retailers to inform its own competitive product sales. Shopify disrupts Amazon by offering customers the service and value of Amazon without the data and branding exploitation. The result? A $131 billion market cap, up 6 times since the beginning of 2019. Shopify has outperformed Amazon stock YTD (+250% vs. +72%).

Spotify. Spotify boasts global reach, product differentiation, and likability. It lacks vertical integration and is perpetually punished for that by Apple, which skims 30% in App Store commission. In 2018, I predicted the stock would double in 12 months. I was wrong, it took 30. But Spotify still has all the makings of a potential trillion-dollar firm. They have recurring revenue and a Benjamin Button product—it ages in reverse and appreciates, rather than depreciates, with time and increased use.

But even with these assets, Spotify’s stock hasn’t reached big tech status with a market cap of $47 billion. What’s holding the Swedish firm back? Apple Music. The Cupertino giant has half the paid subscribers and inferior NPS scores. But most of the music available on Spotify is also available on Apple Music, and Apple Music has a key advantage—it’s vertical, controlling its own distribution.

The gangster move? Netflix and Spotify merge and acquire Sonos for vertical integration. The two mob families of subscription media consolidate to control video and music. Gangster. They acquire Sonos (with the sweat of their Tiger10 brow at $1.3 billion) and establish a vertical beachhead of devices in the wealthiest homes in America.

Tesla. Appealing to human instinct: Tesla has several points of differentiation—Elon Musk’s vision and storytelling, combined with a tangibly better product, have provided the firm with capital at a cost that renders other automobile manufacturers flaccid, as they can’t make the same forward-leaning investments as the Alameda firm. While Ford is running commercials on NFL reruns on TNT, Elon has NASA astronauts drive a Tesla Model X to the launch pad, where they will board a SpaceX Dragon spaceship. The firm is also vertical, selling cars directly. Does anybody really miss going to an auto dealership? But Tesla’s true kryptonite is its best-in-class ability to command irrational margins by appealing to a core human instinct—procreation. Buying a Tesla is the ultimate status symbol. Most products indicate one of two things: “I’m rich” or “I have a conscience.” But Tesla does what only philanthropy offers … both. Plus, it says: I’m an innovator. I’m ahead of the curve. Put another way, I have genes paramount to the survival of the species; you have a biological imperative to mate with me. And the bad-boy image adds to the procreation-instinct appeal of the car. That tax lawyer driving a Model S isn’t a tax lawyer, he’s a visionary rebel.

Tesla appeals to the genitals through every aspect of its strategy: pricing, production, marketing, and even its leadership. Elon Musk is a genius. I don’t respect many of his personal choices: market manipulation (“funding secured”), calling the Thai cave diver “a pedo,” then insisting he was right, and tweets questioning Covid measures. The founder of a firm on which thousands of livelihoods depend should be more measured and mindful—I know, “ok boomer.”

I’ve said for years (and been wrong) that Tesla is overvalued. Now I prefer to say that it is “fully valued.” Keeps the hate mail down. Yes, Musk is a genius. Yes, Tesla has changed the world for the better through alternative energy. However, at the end of the day, it’s bending steel, and that’s not a business that can support a (double checking my notes) 128 times multiple of EBITDA.

Aswath Damodaran, my colleague at the NYU Stern School of Business, who is dubbed the “Dean of Valuation,” says, “I’ve always thought of Tesla as a story stock. It’s the story that drives the price, not the news, and not the fundamentals …. If you’re trading Tesla based on expected earnings or cash flow, you’re trading it for the wrong reasons. People trade Tesla based on mood and momentum.” Tesla is benefiting from the fact that Covid-19 has had a disproportionately negative effect on older, capital-intensive companies. In a sense, the virus has handicapped Tesla’s competition. That explains why the young electric-car companies are doing better than the established automobile companies, which have lots of debt and huge capital intensity. That’s exactly it—Tesla is in the auto sector, and in that sector, valuations like these don’t make sense. “People who buy Tesla aren’t irrational, it’s just not a rationality I buy into,” Professor Damodaran said. “Tesla is an implausible story but not an impossible story. There is a story you can tell that will justify a $1,500 stock price, but it’s not a story I want to bet on.”11

Twitter. (Disclosure: I am a shareholder.) If Twitter commanded the space it occupies, it would be a $100-billion-dollar company (vs. $30 billion). The microblogging platform has become an iconic brand and the global heartbeat for our information age. The only firms with the reach and influence of Twitter (Tencent, Facebook, and Google) register 17, 24, and 39 times the market capitalization, respectively. This is an embarrassment, and management is to blame. Half to blame, since CEO Jack Dorsey is only part time. Or does that make him doubly to blame?

Twitter has a lot of negatives: fake accounts, GRU-sponsored trolls, algorithms that promote conspiracies and junk science, and inconsistent application of the terms of service, to name a few. Users regularly refer to it as a hellsite and being on it as doomscrolling. But none of these are why it can’t turn on the profit engines. All this and worse hasn’t stopped Facebook. The problem is the model. Twitter is stubbornly clinging to an advertising business, but it doesn’t have the scale or the tools to compete with Facebook and Google. As a result it has all the problems of being in the free/red/Android camp, without the scale advantages.

In December 2019, I purchased 330,000 shares and wrote an open letter to Twitter’s board of directors, which can be found at profgalloway.com/twtr-enough-already.

Shocker: I didn’t get a response. However, a couple of months later Elliott Management (a hedge fund with $38 billion under management) informed me they had essentially signed my letter with a $2-billion pen, and 3 weeks later they were granted 3 seats on the board. In the world of activist investing, securing 3 seats in 3 weeks means the company knows it doesn’t have a leg to stand on (see above: part-time CEO). I am advising Elliott, and my advice has been well publicized.

Twitter needs to go iOS—charge for value vs. exploit for data. It needs to move to a subscription model, as I described in chapter 1. Free for accounts under 2,000 followers, then a sliding scale that starts small, but as the value to the user of having a big audience starts to kick in, the subscription fees rise accordingly.

I had been calling for Twitter to do this for months when Jack announced a move toward subscription in July 2020. The stock popped 4%. A full-time CEO would have figured it out sooner.

Uber. Ride hailing is the tobacco of the gig economy and the most recent battle waged by the lords against the serfs in the U.S. We’ve sequestered the mostly non-white, mostly non-college-educated drivers (3.9 million of them) from the mostly white, mostly college-educated employees (22,000 of them) at HQ, who will split, with their investors, the value of BMW and Ford. By the way, BMW and Ford employ 334,000 people. Pretty sure most have health insurance. The average hourly wage at Ford is $26 an hour. At Uber, it’s $9 an hour.

Unlike Lyft, which will either be acquired or go out of business, Uber has a global brand and has demonstrated a flywheel—Uber Eats. With the purchase of Postmates in July 2020, amid the pandemic, the flywheel gets stronger. If Uber leverages their formidable brand, culture of innovation, and flywheel, it could be worth $40 billion, even $50 billion—a 50% decline from its pricing on the eve of the IPO. In its favor during Covid is its ability to variabilize costs. Uber’s capacity to extend beyond ride hailing is key, because ride hailing is a difficult business. But even a bad business can be a flywheel if you get big enough and develop a sufficiently lucrative business model. Contrast with Lyft, which is actually trying to make a business out of ride hailing, sub-scale. Acquired, most likely in 2021.

Uber has a Benjamin Button effect—the more people that use the algo, the better it gets. The more drivers, the lower the rates, and the more accurate the maps, time estimates, and other aspects of the algorithm. In terms of likability, Uber has had quite a bit to repair after the founding CEO, Travis Kalanick, wrecked the brand’s image with a bro culture made famous by a young female engineer, Susan Fowler. Leather jackets for all employees … except women.12 Dara Khosrowshahi has been a vast improvement and has dealt with a row of crises in a resolute manner. In terms of vertical integration, Uber’s strength (minimal CapEx) is also its soft tissue, as it doesn’t own cars or have exclusive driver contracts. Many, if not most, Uber drivers also drive for Lyft. Uber’s growth has been strong. Even if it’s not currently profitable, margins are improving.

Warby Parker. The incumbent (EssilorLuxottica) has raised prices and not innovated—offering hundreds of millions, maybe billions, in unearned margin up for grabs. Despite a sector, specialty retail, that’s been hammered, Warby will be a rare retail IPO of 2021.

Warby is the least bad start-up in specialty retail, a sector that has been a wonderful place to shop and a terrible place to invest or work. The firm tells a great story that garners huge PR, as evidenced by Casper and Away needing to pay to generate traffic while Warby Parker gets nearly 80% of its traffic organically. Warby looks to have the muscle (vertical distribution, differentiated product) and fat (access to cheap capital) to survive an Amazon winter and emerge stronger.

WeWork. No, really. The concept works (coworking) but needs to be right-sized. Restructuring may be in store for many unicorns who have a decent business at their core, but just got way over their skis. They need to think like the real estate business they are. For example, hotels are usually separate LLCs so one hotel can declare bankruptcy without taking down the whole company. Smart. If WeWork can shed its bad assets (step one, fire the founder, done) coworking has a bright post-pandemic future. Many of America’s office workers have been freed of the office, but not everyone wants to work at their kitchen table. Expect to see “Remote with Cowork Stipend” appearing on the comp line of more and more job descriptions, and companies limiting their permanent footprints drastically, relying instead on flexible space arrangements with partners like WeWork 2.0. We was never worth $47 billion, but it may be worth more than its Covid valuation.

TikTok. I’m less certain about what will happen with Tik Tok than what will not happen. Despite a lot of sound and fury in the summer of 2020, the Chinese will not be bullied by the Trump administration into selling a global internet asset on the cheap. For one thing, China has ample means to counterattack against Trump’s threat to ban TikTok. Imagine if President Xi Jinping announced, “The iPhone circumvents Chinese security protocols. Apple must sell its operations in China, intellectual property rights, and supply chain agreements to a Chinese firm within 45 days.” Goodbye, NASDAQ recovery. Not to mention people like TikTok. Including quite a few people who vote. And indeed, even as this book goes to press, Trump has already extended his 45-day deadline for TikTok’s U.S. assets to be sold to an American company to a 90-day deadline. The Chinese government has positioned itself to call Trump’s bluff by requiring TikTok to get its approval before selling to a foreign company, and Microsoft, the likeliest and most logical suitor, has dropped out of the bidding. This chapter of the saga will likely be over by the time you read this, but right now, the best Trump can hope for is a face-saving “partnership” between Oracle and ByteDance with vague terms designed to placate Beijing, not Washington.

In the meantime, the furor has been a great chance for companies to juice their stock prices by letting rumors circulate about their own supposed interest in the company. Twitter’s stock jumped 5%, only to slide back once investors did the math and realized any deal would mean that ByteDance would effectively be buying Twitter, in light of Twitter’s relatively small valuation. You have to love the unintended consequences there—trying to acquire TikTok for an American company, Trump could have ended up facilitating Twitter’s sale to a Chinese one.

The bottom line is that TikTok has a great product. The algorithm is brilliant at surfacing new, relevant content, and the content creation tools ensure there is plenty such content queued up. This is not easy—look at Reels, Facebook’s (predictable) rip-off feature recently added to Instagram. New York Times internet culture writer Taylor Lorenz tried it for five days and concluded: “I can definitively say Reels is the worst feature I’ve ever used.”13 Great products find their way into great businesses, and whether as a Microsoft product (and Redmond, to its credit, has managed not to ruin Minecraft, Skype, or LinkedIn, all high-profile acquisitions that continue to thrive) or on its own, TikTok has a bright potential future. Similar to the poorly executed trade war, China will not blink first, as they blink less often—they think in 50-year time horizons.

VENTURE CAPITAL INVESTMENTS have largely recovered to pre-Covid levels.14 We’ve been in a slow-moving technology revolution for most of my adult life, but only recently has the infrastructure and technology advanced to the point where the widespread disruption we’ve been expecting for decades started to shake the roots of the largest consumer sectors in the economy. As opportunities arise, the private markets are flush with capital, the public markets are hungry for growth stories, and the potential acquirers have deeper pockets than ever (though antitrust may dampen the ardor of big tech acquisitions for a while). Again, I believe the 2020–21 IPO class will be one of the best-performing vintages of the last several years. The successes will wallpaper over an uncomfortable truth: some of the fastest-growing sectors in our economy have scant start-up funding, as the incumbents have not been subject to the same antitrust or regulatory scrutiny as firms in the past.

You’ve likely noticed that a key to a firm’s success is the inertia of the incumbents. There are few industries as big and immobile as higher education in the U.S.