The two economic engines that have powered the world through the global recession that set in after 2001 have been the United States and China. The irony is that both have been behaving like Keynesian states in a world supposedly governed by neoliberal rules. The US has resorted to massive deficit-financing of its militarism and its consumerism, while China has debt-financed with non-performing bank loans massive infrastructural and fixed-capital investments. True blue neoliberals will doubtless claim that the recession is a sign of insufficient or imperfect neoliberalization, and they could well point to the operations of the IMF and the army of well-paid lobbyists in Washington that regularly pervert the US budgetary process for their special-interest ends as evidence for their case. But their claims are impossible to verify, and, in making them, they merely follow in the footsteps of a long line of eminent economic theorists who argue that all would be well with the world if only everyone behaved according to the precepts of their textbooks.1

But there is a more sinister interpretation of this paradox. If we lay aside, as I believe we must, the claim that neoliberalization is merely an example of erroneous theory gone wild (pace the economist Stiglitz) or a case of senseless pursuit of a false utopia (pace the conservative political philosopher John Gray2), then we are left with a tension between sustaining capitalism, on the one hand, and the restoration/reconstitution of ruling class power on the other. If we are at a point of outright contradiction between these two objectives, then there can be no doubt as to which side the current Bush administration is leaning, given its avid pursuit of tax cuts for the corporations and the rich. Furthermore, a global financial crisis in part provoked by its own reckless economic policies would permit the US government to finally rid itself of any obligation whatsoever to provide for the welfare of its citizens except for the ratcheting up of that military and police power that might be needed to quell social unrest and compel global discipline. Saner voices within the capitalist class, having listened carefully to the warnings of the likes of Paul Volcker that there is a high probability of a serious financial crisis in the next five years, may prevail.3 But this will mean rolling back some of the privileges and power that have over the last thirty years been accumulating in the upper echelons of the capitalist class. Previous phases of capitalist history—one thinks of 1873 or the 1920s—when a similarly stark choice arose, do not augur well. The upper classes, insisting on the sacrosanct nature of their property rights, preferred to crash the system rather than surrender any of their privileges and power. In so doing they were not oblivious of their own interest, for if they position themselves aright they can, like good bankruptcy lawyers, profit from a collapse while the rest of us are caught most horribly in the deluge. A few of them may get caught and end up jumping out of Wall Street windows, but that is not the norm. The only fear they have is of political movements that threaten them with expropriation or revolutionary violence. While they can hope that the sophisticated military apparatus they now possess (thanks to the military industrial complex) will protect their wealth and power, the failure of that apparatus to easily pacify Iraq on the ground should give them pause. But ruling classes rarely, if ever, voluntarily surrender any of their power and I see no reason to believe they will do so this time. Paradoxically, a strong and powerful social democratic and working-class movement is in a better position to redeem capitalism than is capitalist class power itself. While this may sound a counter-revolutionary conclusion to those on the far left, it is not without a strong element of self-interest either, because it is ordinary people who suffer, starve, and even die in the course of capitalist crises (examine Indonesia or Argentina) rather than the upper classes. If the preferred policy of ruling elites is après moi le déluge, then the deluge largely engulfs the powerless and the unsuspecting while elites have well-prepared arks in which they can, at least for a time, survive quite well.

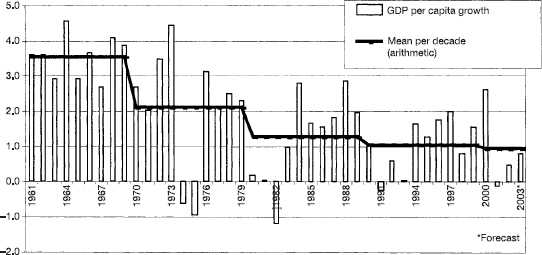

What I have written above is speculative. But we can usefully scrutinize the historical-geographical record of neoliberalization for evidence of its powers as a potential cure-all for the political-economic ills that currently threaten us. To what degree, then, has neoliberalization succeeded in stimulating capital accumulation? Its actual record turns out to be nothing short of dismal. Aggregate global growth rates stood at 3.5 per cent or so in the 1960s and even during the troubled 1970s fell only to 2.4 per cent. But the subsequent growth rates of 1.4 per cent and 1.1 per cent for the 1980s and 1990s (and a rate that barely touches 1 per cent since 2000) indicate that neoliberalization has broadly failed to stimulate worldwide growth (see Figure 6.1).4 In some cases, such as the territories of the ex-Soviet Union and those countries in central Europe that submitted to neoliberal ‘shock therapy’, there have been catastrophic losses. During the 1990s, Russian per capita income declined at the rate of 3.5 per cent annually. A large proportion of the population fell into poverty, and male life expectancy declined by five years as a result. Ukraine’s experience was similar. Only Poland, which flouted IMF advice, showed any marked improvement. In much of Latin America neoliberalization produced either stagnation (in the ‘lost decade’ of the 1980s) or spurts of growth followed by economic collapse (as in Argentina). And in Africa it has done nothing at all to generate positive changes. Only in East and South-East Asia, followed now to some extent by India, has neoliberalization been associated with any positive record of growth, and there the not very neoliberal developmental states played a very significant role. The contrast between China’s growth (nearly 10 per cent annually) and Russian decline (−3.5 per cent annually) is stark. Informal employment has soared worldwide (estimates suggest it rose from 29 per cent of the economically active population in Latin America during the 1980s to 44 per cent during the 1990s) and almost all global indicators on health levels, life expectancy, infant mortality, and the like show losses rather than gains in well-being since the 1960s. The proportion of the world’s population in poverty has, however, fallen but this is almost entirely due to improvements in India and China alone.5 The reduction and control of inflation is the only systematic success neoliberalization can claim.

Figure 6.1 Global growth rates, annually and by decade, 1960–2003

Source: World Commission on the Social Dimension of Globalization, A Fair Globalization.

Comparisons are always odious, of course, but this is particularly so for neoliberalization. Circumscribed neoliberalization in Sweden, for example, has achieved far better results than sustained neoliberalization in the UK. Swedish per capita incomes are higher, inflation lower, the current account position with the rest of the world better, and all indices of competitive position and of business climate superior. Quality of life indices are higher. Sweden ranks third in the world in life expectancy compared to the UK’s ranking of twenty-ninth. The poverty rate is 6.3 per cent in Sweden as opposed to 15.7 per cent in the UK, while the richest 10 per cent of the population in Sweden gain 6.2 times the incomes of the bottom 10 per cent, whereas in the UK the figure is 13.6. Illiteracy is lower in Sweden and social mobility greater.6

Were these sorts of facts widely known the praise for neoliberalization and its distinctive form of globalization would surely be much muted. Why, then, are so many persuaded that neoliberalization through globalization is the ‘only alternative’ and that it has been so successful? Two reasons stand out. First, the volatility of uneven geographical development has accelerated, permitting certain territories to advance spectacularly (at least for a time) at the expense of others. If, for example, the 1980s belonged largely to Japan, the Asian ‘tigers’, and West Germany, and if the 1990s belonged to the US and the UK, then the fact that ‘success’ was to be had somewhere obscured the fact that neoliberalization was generally failing to stimulate growth or improve well-being. Secondly, neoliberalization, the process rather than the theory, has been a huge success from the standpoint of the upper classes. It has either restored class power to ruling elites (as in the US and to some extent in Britain—see Figure 1.3) or created conditions for capitalist class formation (as in China, India, Russia, and elsewhere). With the media dominated by upper-class interests, the myth could be propagated that states failed economically because they were not competitive (thereby creating a demand for even more neoliberal reforms). Increased social inequality within a territory was construed as necessary to encourage the entrepreneurial risk and innovation that conferred competitive power and stimulated growth. If conditions among the lower classes deteriorated, this was because they failed, usually for personal and cultural reasons, to enhance their own human capital (through dedication to education, the acquisition of a Protestant work ethic, submission to work discipline and flexibility, and the like). Particular problems arose, in short, because of lack of competitive strength or because of personal, cultural, and political failings. In a Darwinian neoliberal world, the argument went, only the fittest should and do survive.

Of course there have been a number of spectacular shifts of emphasis under neoliberalization and these give it the appearance of incredible dynamism. The rise of finance and of financial services has been paralleled by a remarkable shift in the remuneration of financial corporations (see Figure 6.2) as well as a tendency for the larger corporations (such as General Motors) to fuse the two functions. Employment in these sectors has burgeoned remarkably. But there are serious questions as to how productive this has been. Much of the business of finance turns out to be about finance and nothing else. Speculative gains are perpetually being sought, and to the degree that they can be had all manner of shifts in power can be accomplished. So-called global cities of finance and command functions have become spectacular islands of wealth and privilege, with towering skyscrapers and millions upon millions of square feet of office space to house these operations. Within these towers, trading between floors creates a vast amount of fictitious wealth. Speculative urban property markets, furthermore, have become prime engines of capital accumulation. The rapidly evolving skylines of Manhattan, Tokyo, London, Paris, Frankfurt, Hong Kong, and now Shanghai are marvels to behold.

Along with this has gone an extraordinary burst in information technologies. In 1970 or so investment in that field was on a par with the 25 per cent going into production and to physical infrastructures respectively, but, by 2000, IT accounted for around 45 per cent of all investment, while the relative shares of investment in production and physical infrastructures declined. During the 1990s this was thought to betoken the rise of a new information economy.7 It in fact represented an unfortunate bias in the path of technological change away from production and infrastructure formation into lines required by the market-driven financialization that was the hallmark of neoliberalization. Information technology is the privileged technology of neoliberalism. It is far more useful for speculative activity and for maximizing the number of short-term market contracts than for improving production. Interestingly, the main arenas of production that gained were the emergent cultural industries (films, videos, video games, music, advertising, art shows), which use IT as a basis for innovation and the marketing of new products. The hype around these new sectors diverted attention from the failure to invest in basic physical and social infrastructures. Along with all of this went the hype about ‘globalization’ and all that it supposedly stood for in terms of the construction of an entirely different and totally integrated global economy.8

Figure 6.2 The hegemony of finance capital: net worth and rates of profit for financial and non-financial corporations in the US, 1960–2001

Source: Duménil and Lévy, Capital Resurgent, 111, 134. Reproduced courtesy Harvard University Press.

The main substantive achievement of neoliberalization, however, has been to redistribute, rather than to generate, wealth and income. I have elsewhere provided an account of the main mechanisms whereby this was achieved under the rubric of ‘accumulation by dispossession’.9 By this I mean the continuation and proliferation of accumulation practices which Marx had treated of as ‘primitive’ or ‘original’ during the rise of capitalism. These include the commodification and privatization of land and the forceful expulsion of peasant populations (compare the cases, described above, of Mexico and of China, where 70 million peasants are thought to have been displaced in recent times); conversion of various forms of property rights (common, collective, state, etc.) into exclusive private property rights (most spectacularly represented by China); suppression of rights to the commons; commodification of labour power and the suppression of alternative (indigenous) forms of production and consumption; colonial, neocolonial, and imperial processes of appropriation of assets (including natural resources); monetization of exchange and taxation, particularly of land; the slave trade (which continues particularly in the sex industry); and usury, the national debt and, most devastating of all, the use of the credit system as a radical means of accumulation by dispossession. The state, with its monopoly of violence and definitions of legality, plays a crucial role in both backing and promoting these processes. To this list of mechanisms we may now add a raft of techniques such as the extraction of rents from patents and intellectual property rights and the diminution or erasure of various forms of common property rights (such as state pensions, paid vacations, and access to education and health care) won through a generation or more of class struggle. The proposal to privatize all state pension rights (pioneered in Chile under the dictatorship) is, for example, one of the cherished objectives of the Republicans in the US.

Accumulation by dispossession comprises four main features:

1. Privatization and commodification. The corporatization, commodification, and privatization of hitherto public assets has been a signal feature of the neoliberal project. Its primary aim has been to open up new fields for capital accumulation in domains hitherto regarded off-limits to the calculus of profitability. Public utilities of all kinds (water, telecommunications, transportation), social welfare provision (social housing, education, health care, pensions), public institutions (universities, research laboratories, prisons) and even warfare (as illustrated by the ‘army’ of private contractors operating alongside the armed forces in Iraq) have all been privatized to some degree throughout the capitalist world and beyond (for example in China). The intellectual property rights established through the so-called TRIPS agreement within the WTO defines genetic materials, seed plasmas, and all manner of other products as private property. Rents for use can then be extracted from populations whose practices had played a crucial role in the development of these genetic materials. Biopiracy is rampant and the pillaging of the world’s stockpile of genetic resources is well under way to the benefit of a few large pharmaceutical companies. The escalating depletion of the global environmental commons (land, air, water) and proliferating habitat degradations that preclude anything but capital-intensive modes of agricultural production have likewise resulted from the wholesale commodification of nature in all its forms. The commodification (through tourism) of cultural forms, histories, and intellectual creativity entails wholesale dispossessions (the music industry is notorious for the appropriation and exploitation of grassroots culture and creativity). As in the past, the power of the state is frequently used to force such processes even against popular will. The rolling back of regulatory frameworks designed to protect labour and the environment from degradation has entailed the loss of rights. The reversion of common property rights won through years of hard class struggle (the right to a state pension, to welfare, to national health care) into the private domain has been one of the most egregious of all policies of dispossession, often procured against the broad political will of the population. All of these processes amount to the transfer of assets from the public and popular realms to the private and class-privileged domains.10

2. Financialization. The strong wave of financialization that set in after 1980 has been marked by its speculative and predatory style. The total daily turnover of financial transactions in international markets, which stood at $2.3 billion in 1983, had risen to $130 billion by 2001. The $40 trillion annual turnover in 2001 compares to the estimated $800 billion that would be required to support international trade and productive investment flows.11 Deregulation allowed the financial system to become one of the main centres of redistributive activity through speculation, predation, fraud, and thievery. Stock promotions, ponzi schemes, structured asset destruction through inflation, asset-stripping through mergers and acquisitions, the promotion of levels of debt incumbency that reduced whole populations, even in the advanced capitalist countries, to debt peonage, to say nothing of corporate fraud, dispossession of assets (the raiding of pension funds and their decimation by stock and corporate collapses) by credit and stock manipulations—all of these became central features of the capitalist financial system. Innumerable ways exist to skim off values from within the financial system. Since brokers get a commission for each transaction, they can maximize their incomes by frequent trading on their accounts (a practice known as ‘churning’) no matter whether the trades add value to the account or not. High turnover on the stock exchange may simply reflect churning rather than confidence in the market. The emphasis on stock values, which arose out of bringing together the interests of owners and managers of capital through the remuneration of the latter in stock options, led, as we now know, to manipulations in the market that brought immense wealth to a few at the expense of the many. The spectacular collapse of Enron was emblematic of a general process that dispossessed many of their livelihoods and their pension rights. Beyond this, we also have to look at the speculative raiding carried out by hedge funds and other major institutions of finance capital, for these formed the real cutting edge of accumulation by dispossession on the global stage, even as they supposedly conferred the positive benefit of ‘spreading risks’.12

3. The management and manipulation of crises. Beyond the speculative and often fraudulent froth that characterizes much of neo-liberal financial manipulation, there lies a deeper process that entails the springing of ‘the debt trap’ as a primary means of accumulation by dispossession.13 Crisis creation, management, and manipulation on the world stage has evolved into the fine art of deliberative redistribution of wealth from poor countries to the rich. I documented the impact of Volcker’s interest rate increase on Mexico earlier. While proclaiming its role as a noble leader organizing ‘bail-outs’ to keep global capital accumulation on track, the US paved the way to pillage the Mexican economy. This was what the US Treasury–Wall Street–IMF complex became expert at doing everywhere. Greenspan at the Federal Reserve deployed the same Volcker tactic several times in the 1990s. Debt crises in individual countries, uncommon during the 1960s, became very frequent during the 1980s and 1990s. Hardly any developing country remained untouched, and in some cases, as in Latin America, such crises became endemic. These debt crises were orchestrated, managed, and controlled both to rationalize the system and to redistribute assets. Since 1980, it has been calculated, ‘over fifty Marshall Plans (over $4.6 trillion) have been sent by the peoples at the Periphery to their creditors in the Center’. ‘What a peculiar world’, sighs Stiglitz, ‘in which the poor countries are in effect subsidizing the richest.’ What neoliberals call ‘confiscatory deflation’ is, furthermore, nothing other than accumulation by dispossession. Wade and Veneroso capture the essence of this when they write of the Asian crisis of 1997–8:

Financial crises have always caused transfers of ownership and power to those who keep their own assets intact and who are in a position to create credit, and the Asian crisis is no exception… there is no doubt that Western and Japanese corporations are the big winners… The combination of massive devaluations, IMF-pushed financial liberalization, and IMF-facilitated recovery may even precipitate the biggest peacetime transfer of assets from domestic to foreign owners in the past fifty years anywhere in the world, dwarfing the transfers from domestic to US owners in Latin America in the 1980s or in Mexico after 1994. One recalls the statement attributed to Andrew Mellon: ‘In a depression assets return to their rightful owners.’14

The analogy with the deliberate creation of unemployment to produce a labour surplus convenient for further accumulation is exact. Valuable assets are thrown out of use and lose their value. They lie fallow until capitalists possessed of liquidity choose to breathe new life into them. The danger, however, is that crises might spin out of control and become generalized, or that revolts will arise against the system that creates them. One of the prime functions of state interventions and of international institutions is to control crises and devaluations in ways that permit accumulation by dispossession to occur without sparking a general collapse or popular revolt (as happened in both Indonesia and Argentina). The structural adjustment programme administered by the Wall Street–Treasury–IMF complex takes care of the first while it is the job of the comprador state apparatus (backed by military assistance from the imperial powers) in the country that has been raided to ensure that the second does not occur. But the signs of popular revolt are everywhere, as illustrated by the Zapatista uprising in Mexico, innumerable anti-IMF riots, and the so-called ‘anti-globalization’ movement that cut its teeth in the revolts at Seattle, Genoa, and elsewhere.

4. State redistributions. The state, once neoliberalized, becomes a prime agent of redistributive policies, reversing the flow from upper to lower classes that had occurred during the era of embedded liberalism. It does this in the first instance through pursuit of privatization schemes and cutbacks in those state expenditures that support the social wage. Even when privatization appears to be beneficial to the lower classes, the long-term effects can be negative. At first blush, for example, Thatcher’s programme for the privatization of social housing in Britain appeared as a gift to the lower classes, whose members could now convert from rental to ownership at a relatively low cost, gain control over a valuable asset, and augment their wealth. But once the transfer was accomplished housing speculation took over, particularly in prime central locations, eventually bribing or forcing low-income populations out to the periphery in cities like London and turning erstwhile working-class housing estates into centres of intense gentrification. The loss of affordable housing in central areas produced homelessness for some and long commutes for those with low-paying service jobs. The privatization of the ejidos in Mexico during the 1990s had analogous effects upon the prospects for the Mexican peasantry, forcing many rural dwellers off the land into the cities in search of employment. The Chinese state has sanctioned the transfer of assets to a small elite to the detriment of the mass of the population and provoking violently repressed protests. Reports now indicate that as many as 350,000 families (a million people) are being displaced to make way for the urban renewal of much of old Beijing, with the same outcome as that in Britain and Mexico outlined above. In the US, revenue-strapped municipalities are now regularly using the power of eminent domain to displace low- and even moderate-income property owners living in perfectly good housing stock in order to free land for upper-income and commercial developments that will enhance the tax base (in New York State there are more than sixty current cases of this).15

The neoliberal state also redistributes wealth and income through revisions in the tax code to benefit returns on investment rather than incomes and wages, promotion of regressive elements in the tax code (such as sales taxes), the imposition of user fees (now widespread in rural China), and the provision of a vast array of subsidies and tax breaks to corporations. The rate of corporate taxation in the US has steadily declined, and the Bush re-election was greeted with smiles by corporate leaders in anticipation of even further cuts in their tax obligations. The corporate welfare programmes that now exist in the US at federal, state, and local levels amount to a vast redirection of public moneys for corporate benefit (directly as in the case of subsidies to agribusiness and indirectly as in the case of the military-industrial sector), in much the same way that the mortgage interest rate tax deduction operates in the US as a subsidy to upper-income homeowners and the construction industry. The rise of surveillance and policing and, in the case of the US, incarceration of recalcitrant elements in the population indicates a more sinister turn towards intense social control. The prison-industrial complex is a thriving sector (alongside personal security services) in the US economy. In the developing countries, where opposition to accumulation by dispossession can be stronger, the role of the neoliberal state quickly assumes that of active repression even to the point of low-level warfare against oppositional movements (many of which can now conveniently be designated as ‘drug trafficking’ or ‘terrorist’ so as to garner US military assistance and support, as in Colombia). Other movements, such as the Zapatistas in Mexico or the landless peasant movement in Brazil, are contained by state power through a mix of co-optation and marginalization.16

To presume that markets and market signals can best determine all allocative decisions is to presume that everything can in principle be treated as a commodity. Commodification presumes the existence of property rights over processes, things, and social relations, that a price can be put on them, and that they can be traded subject to legal contract. The market is presumed to work as an appropriate guide—an ethic—for all human action. In practice, of course, every society sets some bounds on where commodification begins and ends. Where the boundaries lie is a matter of contention. Certain drugs are deemed illegal. The buying and selling of sexual favours is outlawed in most US states, though elsewhere it may be legalized, decriminalized, and even state-regulated as an industry. Pornography is broadly protected as a form of free speech under US law although here, too, there are certain forms (mainly concerning children) that are considered beyond the pale. In the US, conscience and honour are supposedly not for sale, and there exists a curious penchant to pursue ‘corruption’ as if it is easily distinguishable from the normal practices of influence-peddling and making money in the marketplace. The commodification of sexuality, culture, history, heritage; of nature as spectacle or as rest cure; the extraction of monopoly rents from originality, authenticity, and uniqueness (of works or art, for example)—these all amount to putting a price on things that were never actually produced as commodities.17 There is often disagreement as to the appropriateness of commodification (of religious events and symbols, for example) or of who should exercise the property rights and derive the rents (over access to Aztec ruins or marketing of Aboriginal art, for example).

Neoliberalization has unquestionably rolled back the bounds of commodification and greatly extended the reach of legal contracts. It typically celebrates (as does much of postmodern theory) ephemerality and the short-term contract—marriage, for example, is understood as a short-term contractual arrangement rather than as a sacred and unbreakable bond. The divide between neoliberals and neoconservatives partially reflects a difference as to where the lines are drawn. The neoconservatives typically blame ‘liberals’, ‘Hollywood’, or even ‘postmodernists’ for what they see as the dissolution and immorality of the social order, rather than the corporate capitalists (like Rupert Murdoch) who actually do most of the damage by foisting all manner of sexually charged if not salacious material upon the world and who continually flaunt their pervasive preference for short-term over long-term commitments in their endless pursuit of profit.

But there are far more serious issues here than merely trying to protect some treasured object, some particular ritual or a preferred corner of social life from the monetary calculus and the short-term contract. For at the heart of liberal and neoliberal theory lies the necessity of constructing coherent markets for land, labour, and money, and these, as Karl Polanyi pointed out, ‘are obviously not commodities… the commodity description of labour, land, and money is entirely fictitious’. While capitalism cannot function without such fictions, it does untold damage if it fails to acknowledge the complex realities behind them. Polanyi, in one of his more famous passages, puts it this way:

To allow the market mechanism to be sole director of the fate of human beings and their natural environment, indeed, even of the amount and use of purchasing power, would result in the demolition of society. For the alleged commodity ‘labour power’ cannot be shoved about, used indiscriminately, or even left unused, without affecting also the human individual who happens to be the bearer of this peculiar commodity. In disposing of man’s labour power the system would, incidentally, dispose of the physical, psychological, and moral entity ‘man’ attached to that tag. Robbed of the protective covering of cultural institutions, human beings would perish from the effects of social exposure; they would die as victims of acute social dislocation through vice, perversion, crime and starvation. Nature would be reduced to its elements, neighborhoods and landscapes defiled, rivers polluted, military safety jeopardized, the power to produce food and raw materials destroyed. Finally, the market administration of purchasing power would periodically liquidate business enterprise, for shortages and surfeits of money would prove as disastrous to business as floods and droughts in primitive society.18

The damage wrought through the ‘floods and droughts’ of fictitious capitals within the global credit system, be it in Indonesia, Argentina, Mexico, or even within the US, testifies all too well to Polanyi’s final point. But his theses on labour and land deserve further elaboration.

Individuals enter the labour market as persons of character, as individuals embedded in networks of social relations and socialized in various ways, as physical beings identifiable by certain characteristics (such as phenotype and gender), as individuals who have accumulated various skills (sometimes referred to as ‘human capital’) and tastes (sometime referred to as ‘cultural capital’), and as living beings endowed with dreams, desires, ambitions, hopes, doubts, and fears. For capitalists, however, such individuals are a mere factor of production, though not an undifferentiated factor since employers require labour of certain qualities, such as physical strength, skills, flexibility, docility, and the like, appropriate to certain tasks. Workers are hired on contract, and in the neoliberal scheme of things short-term contracts are preferred in order to maximize flexibility. Employers have historically used differentiations within the labour pool to divide and rule. Segmented labour markets then arise and distinctions of race, ethnicity, gender, and religion are frequently used, blatantly or covertly, in ways that redound to the employers’ advantage. Conversely, workers may use the social networks in which they are embedded to gain privileged access to certain lines of employment. They typically seek to monopolize skills and, through collective action and the creation of appropriate institutions, seek to regulate the labour market to protect their interests. In this they are merely constructing that ‘protective covering of cultural institutions’ of which Polanyi speaks.

Neoliberalization seeks to strip away the protective coverings that embedded liberalism allowed and occasionally nurtured. The general attack against labour has been two-pronged. The powers of trade unions and other working-class institutions are curbed or dismantled within a particular state (by violence if necessary). Flexible labour markets are established. State withdrawal from social welfare provision and technologically induced shifts in job structures that render large segments of the labour force redundant complete the domination of capital over labour in the marketplace. The individualized and relatively powerless worker then confronts a labour market in which only short-term contracts are offered on a customized basis. Security of tenure becomes a thing of the past (Thatcher abolished it in universities, for example). A ‘personal responsibility system’ (how apt Deng’s language was!) is substituted for social protections (pensions, health care, protections against injury) that were formerly an obligation of employers and the state. Individuals buy products in the markets that sell social protections instead. Individual security is therefore a matter of individual choice tied to the affordability of financial products embedded in risky financial markets.

The second prong of attack entails transformations in the spatial and temporal co-ordinates of the labour market. While too much can be made of the ‘race to the bottom’ to find the cheapest and most docile labour supplies, the geographical mobility of capital permits it to dominate a global labour force whose own geographical mobility is constrained. Captive labour forces abound because immigration is restricted. These barriers can be evaded only by illegal immigration (which creates an easily exploitable labour force) or through short-term contracts that permit, for example, Mexican labourers to work in Californian agribusiness only to be shamelessly shipped back to Mexico when they get sick and even die from the pesticides to which they are exposed.

Under neoliberalization, the figure of ‘the disposable worker’ emerges as prototypical upon the world stage.19 Accounts of the appalling conditions of labour and the despotic conditions under which labourers work in the sweatshops of the world abound. In China, the conditions under which migrant young women from rural areas work are nothing short of appalling: ‘unbearably long hours, substandard food, cramped dorms, sadistic managers who beat and sexually abuse them, and pay that arrives months late, or sometimes not at all’.20 In Indonesia, two young women recounted their experiences working for a Singapore-based Levi-Strauss subcontractor as follows:

We are regularly insulted, as a matter of course. When the boss gets angry he calls the women dogs, pigs, sluts, all of which we have to endure patiently without reacting. We work officially from seven in the morning until three (salary less than $2 a day), but there is often compulsory overtime, sometimes—especially if there is an urgent order to be delivered—until nine. However tired we are, we are not allowed to go home. We may get an extra 200 rupiah (10 US cents)… We go on foot to the factory from where we live. Inside it is very hot. The building has a metal roof, and there is not much space for all the workers. It is very cramped. There are over 200 people working there, mostly women, but there is only one toilet for the whole factory… when we come home from work, we have no energy left to do anything but eat and sleep...21

Similar tales come from the Mexican maquila factories, the Taiwanese- and Korean-operated manufacturing plants in Honduras, South Africa, Malaysia, and Thailand. The health hazards, the exposure to a wide range of toxic substances, and death on the job pass by unregulated and unremarked. In Shanghai, the Taiwanese businessman who ran a textile warehouse ‘in which 61 workers, locked in the building, died in a fire’ received a ‘lenient’ two-year suspended sentence because he had ‘showed repentance’ and ‘cooperated in the aftermath of the fire’.22

Women, for the most part, and sometimes children, bear the brunt of this sort of degrading, debilitating, and dangerous toil.23 The social consequences of neoliberalization are in fact extreme. Accumulation by dispossession typically undermines whatever powers women may have had within household production/marketing systems and within traditional social structures and relocates everything in male-dominated commodity and credit markets. The paths of women’s liberation from traditional patriarchal controls in developing countries lie either through degrading factory labour or through trading on sexuality, which varies from respectable work as hostesses and waitresses to the sex trade (one of the most lucrative of all contemporary industries in which a good deal of slavery is involved). The loss of social protections in advanced capitalist countries has had particularly negative effects on lower-class women, and in many of the ex-communist countries of the Soviet bloc the loss of women’s rights through neoliberalization has been nothing short of catastrophic.

So how, then, do disposable workers—women in particular— survive both socially and affectively in a world of flexible labour markets and short-term contracts, chronic job insecurities, lost social protections, and often debilitating labour, amongst the wreckage of collective institutions that once gave them a modicum of dignity and support? For some the increased flexibility in labour markets is a boon, and even when it does not lead to material gains the simple right to change jobs relatively easily and free of the traditional social constraints of patriarchy and family has intangible benefits. For those who successfully negotiate the labour market there are seemingly abundant rewards in the world of a capitalist consumer culture. Unfortunately, that culture, however spectacular, glamorous, and beguiling, perpetually plays with desires without ever conferring satisfactions beyond the limited identity of the shopping mall and the anxieties of status by way of good looks (in the case of women) or of material possessions. ‘I shop therefore I am’ and possessive individualism together construct a world of pseudo-satisfactions that is superficially exciting but hollow at its core.

But for those who have lost their jobs or who have never managed to move out of the extensive informal economies that now provide a parlous refuge for most of the world’s disposable workers, the story is entirely different. With some 2 billion people condemned to live on less than $2 a day, the taunting world of capitalist consumer culture, the huge bonuses earned in financial services, and the self-congratulatory polemics as to the emancipatory potential of neoliberalization, privatization, and personal responsibility must seem like a cruel joke. From impoverished rural China to the affluent US, the loss of health-care protections and the increasing imposition of all manner of user fees adds considerably to the financial burdens of the poor.24

Neoliberalization has transformed the positionality of labour, of women, and of indigenous groups in the social order by emphasizing that labour is a commodity like any other. Stripped of the protective cover of lively democratic institutions and threatened with all manner of social dislocations, a disposable workforce inevitably turns to other institutional forms through which to construct social solidarities and express a collective will. Everything from gangs and criminal cartels, narco-trafficking networks, minimafias and favela bosses, through community, grassroots and nongovernmental organizations, to secular cults and religious sects proliferate. These are the alternative social forms that fill the void left behind as state powers, political parties, and other institutional forms are actively dismantled or simply wither away as centres of collective endeavour and of social bonding. The marked turn to religion is in this regard of interest. Accounts of the sudden appearance and proliferation of religious sects in the derelict rural regions of China, to say nothing of the emergence of Fulan Gong, are illustrative of this trend.25 The rapid progress of evangelical proselytizing in the chaotic informal economies that have burgeoned under neoliberalization in Latin America, and the revived and in some instances newly constructed religious tribalism and fundamentalism that structure politics in much of Africa and the Middle East, testify to the need to construct meaningful mechanisms of social solidarity. The progress of fundamentalist evangelical Christianity in the US has some connection with proliferating job insecurities, the loss of other forms of social solidarity, and the hollowness of capitalist consumer culture. In Thomas Frank’s account, the religious right took off in Kansas only at the end of the 1980s, after a decade or more of neoliberal restructuring and deindustrialization.26 Such connections may seem far-fetched. But if Polanyi is right and the treatment of labour as a commodity leads to social dislocation, then moves to rebuild different social networks to defend against such a threat become increasingly likely.

The imposition of short-term contractual logic on environmental uses has disastrous consequences. Fortunately, views within the neoliberal camp are somewhat divided on this issue. While Reagan cared nothing for the environment, at one point characterizing trees as a major source of air pollution, Thatcher took the problem seriously. She played a major role in negotiating the Montreal Protocol to limit the use of the CFCs that were responsible for the growing ozone hole around Antarctica. She took the threat of global warming from rising carbon dioxide emissions seriously. Her environmental commitments were not entirely disinterested, of course, since the closure of the coalmines and the destruction of the miners’ union could be partially legitimized on environmental grounds.

Neoliberal state policies with respect to the environment have therefore been geographically uneven and temporally unstable (depending on who holds the reins of state power, with the Reagan and George W. Bush administrations being particularly retrograde in the US). The environmental movement, furthermore, has grown in significance since the 1970s. It has often exerted a restraining influence, depending on time and place. And in some instances capitalist firms have discovered that increasing efficiency and improved environmental performance can go hand in hand. Nevertheless, the general balance sheet on the environmental consequences of neoliberalization is almost certainly negative. Serious though controversial efforts to create indices of human well-being including the costs of environmental degradations suggest an accelerating negative trend since 1970 or so. And there are enough specific examples of environmental losses resulting from the unrestrained application of neoliberal principles to give sustenance to such a general account. The accelerating destruction of tropical rain forests since 1970 is a well-known example that has serious implications for climate change and the loss of biodiversity. The era of neoliberalization also happens to be the era of the fastest mass extinction of species in the Earth’s recent history.27 If we are entering the danger zone of so transforming the global environment, particularly its climate, as to make the earth unfit for human habitation, then further embrace of the neoliberal ethic and of neoliberalizing practices will surely prove nothing short of deadly. The Bush administration’s approach to environmental issues is usually to question the scientific evidence and do nothing (except cut back on the resources for relevant scientific research). But his own research team reports that the human contribution to global warming soared after 1970. The Pentagon also argues that global warming might well in the long run be a more serious threat to the security of the US than terrorism.28 Interestingly, the two main culprits in the growth of carbon dioxide emissions these last few years have been the powerhouses of the global economy, the US and China (which increased its emissions by 45 per cent over the past decade). In the US, substantial progress has been made in increasing energy efficiency in industry and residential construction. The profligacy in this case largely derives from the kind of consumerism that continues to encourage high-energy-consuming suburban and ex-urban sprawl and a culture that opts to purchase gas-guzzling SUVs rather than the more energy-efficient cars that are available. Increasing US dependency on imported oil has obvious geopolitical ramifications. In the case of China, the rapidity of industrialization and of the growth of car ownership doubles the pressure on energy consumption. China has moved from self-sufficiency in oil production in the late 1980s to being the second largest global importer after the US. Here, too, the geopolitical implications are rife as China scrambles to gain a foothold in the Sudan, central Asia, and the Middle East to secure its oil supplies. But China also has vast rather low-grade coal supplies with a high sulphur content. The use of these for power generation is creating major environmental problems, particularly those that contribute to global warming. Furthermore, given the acute power shortages that now bedevil the Chinese economy, with brownouts and blackouts common, there is no incentive whatsoever for local government to follow central government mandates to close down inefficient and ‘dirty’ power stations. The astonishing increase in car ownership and use, largely replacing the bicycle in large cities like Beijing in ten years, has brought China the negative distinction of having sixteen of the twenty worst cities in the world with respect to air quality.29 The cognate effects on global warming are obvious. As usually happens in phases of rapid industrialization, the failure to pay any mind to the environmental consequences is having deleterious effects everywhere. The rivers are highly polluted, water supplies are full of dangerous cancer-inducing chemicals, public health provision is weak (as illustrated by the problems of SARS and the avian flu), and the rapid conversion of land resources to urban uses or to create massive hydroelectric projects (as in the Yangtze valley) all add up to a significant bundle of environmental problems that the central government is only now beginning to address. China is not alone in this, for the rapid burst of growth in India is also being accompanied by stressful environmental changes deriving from the expansion of consumption as well as the increased pressure on natural resource exploitation.

Neoliberalization has a rather dismal record when it comes to the exploitation of natural resources. The reasons are not far to seek. The preference for short-term contractual relations puts pressure on all producers to extract everything they can while the contract lasts. Even though contracts and options may be renewed there is always uncertainty because other sources may be found. The longest possible time-horizon for natural resource exploitation is that of the discount rate (i.e. about twenty-five years) but most contracts are now far shorter. Depletion is usually assumed to be linear, when it is now evident that many ecological systems crash suddenly after they have hit some tipping point beyond which their natural reproduction capacity cannot function. Fish stocks—sardines off California, cod off Newfoundland, and Chilean sea bass—are classic examples of a resource exploited at an ‘optimal’ rate that suddenly crashes without any seeming warning.30 Less dramatic but equally insidious is the case of forestry. Neoliberal insistence upon privatization makes it hard to establish any global agreements on principles of forest management to protect valuable habitats and biodiversity, particularly in the tropical rain forests. In poorer countries with substantial forest resources, the pressure to increase exports and to allow foreign ownerships and concessions means that even minimal protections of forests break down. The over-exploitation of forestry resources after privatization in Chile is a good case in point. But structural adjustment programmes administered by the IMF have had even worse impacts. Imposed austerity means that poorer countries have less money to put into forest management. They are also pressurized to privatize the forests and to open up their exploitation to foreign lumber companies on short-term contracts. Under pressure to earn foreign exchange to pay off their debts, the temptation exists to concede a maximal rate of short-term exploitation. To make matters worse, when IMF-mandated austerity and unemployment strikes, redundant populations may seek sustenance on the land and engage in indiscriminate forest clearance. Since the favoured method is by burning, landless peasant populations together with the logging companies can massively destroy forest resources in very short order, as has happened in Brazil, Indonesia, and several African countries.31 It was no accident that at the height of the fiscal crisis that displaced millions from the job market in Indonesia in 1997–8, forest fires raged out of control in Sumatra (associated with the logging operations of one of Suharto’s richest ethnic Chinese businessmen), creating a massive smoke-pall that engulfed the whole of South-East Asia for several months. It is only when states and other interests are prepared to buck the neoliberal rules and the class interests that support them—and this has occurred on a significant number of occasions—that any modicum of balanced use of the environment is achieved.

Neoliberalization has spawned within itself an extensive oppositional culture. The opposition tends, however, to accept many of the basic propositions of neoliberalism. It focuses on internal contradictions. It takes questions of individual rights and freedoms seriously, for example, and opposes them to the authoritarianism and frequent arbitrariness of political, economic, and class power. It takes the neoliberal rhetoric of improving the welfare of all and condemns neoliberalization for failing in its own terms. Consider, for example, the first substantive paragraph of that quintessential neoliberal document, the WTO agreement. The aim is:

raising standards of living, full employment and a large and steadily growing volume of real income and effective demand, and expanding the production of and trade in goods and services while allowing for the optimal use of the world’s resources in accordance with the objective of sustainable development, seeking both to protect and preserve the environment and to enhance the means for doing so in a manner consistent with their respective needs and concerns at different levels of economic development.32

Similar pious hopes can be found in World Bank pronouncements (‘the reduction of poverty is our chief aim’). None of this sits easily with the actual practices that underpin the restoration or creation of class power and the results in terms of impoverishment and environmental degradation.

The rise of opposition cast in terms of rights violations has been spectacular since 1980. Before then, Chandler reports, a prominent journal such as Foreign Affairs carried not a single article on human rights.33 Human rights issues came to prominence after 1980 and positively boomed after the events in Tiananmen Square and the end of the Cold War in 1989. This corresponds exactly with the trajectory of neoliberalization, and the two movements are deeply implicated in each other. Undoubtedly, the neoliberal insistence upon the individual as the foundational element in political-economic life opens the door to individual rights activism. But by focusing on those rights rather than on the creation or recreation of substantive and open democratic governance structures, the opposition cultivates methods that cannot escape the neoliberal frame. Neoliberal concern for the individual trumps any social democratic concern for equality, democracy, and social solidarities. The frequent appeal to legal action, furthermore, accepts the neoliberal preference for appeal to judicial and executive rather than parliamentary powers. But it is costly and time-consuming to go down legal paths, and the courts are in any case heavily biased towards ruling class interests, given the typical class allegiance of the judiciary. Legal decisions tend to favour rights of private property and the profit rate over rights of equality and social justice. It is, Chandler concludes, ‘the liberal elite’s disillusionment with ordinary people and the political process [that] leads them to focus more on the empowered individual, taking their case to the judge who will listen and decide’.34

Since most needy individuals lack the financial resources to pursue their own rights, the only way in which this ideal can be articulated is through the formation of advocacy groups. The rise of advocacy groups and NGOs has, like rights discourses more generally, accompanied the neoliberal turn and increased spectacularly since 1980 or so. The NGOs have in many instances stepped into the vacuum in social provision left by the withdrawal of the state from such activities. This amounts to privatization by NGO. In some instances this has helped accelerate further state withdrawal from social provision. NGOs thereby function as ‘Trojan horses for global neoliberalism’.35 Furthermore, NGOs are not inherently democratic institutions. They tend to be elitist, unaccountable (except to their donors), and by definition distant from those they seek to protect or help, no matter how well-meaning or progressive they may be. They frequently conceal their agendas, and prefer direct negotiation with or influence over state and class power. They often control their clientele rather than represent it. They claim and presume to speak on behalf of those who cannot speak for themselves, even define the interests of those they speak for (as if people are unable to do this for themselves). But the legitimacy of their status is always open to doubt. When, for example, organizations agitate successfully to ban child labour in production as a matter of universal human rights, they may undermine economies where that labour is fundamental to family survival. Without any viable economic alternative the children may be sold into prostitution instead (leaving yet another advocacy group to pursue the eradication of that). The universality presupposed in ‘rights talk’ and the dedication of the NGOs and advocacy groups to universal principles sits uneasily with the local particularities and daily practices of political and economic life under the pressures of commodification and neoliberalization.36

But there is another reason why this particular oppositional culture has gained so much traction in recent years. Accumulation by dispossession entails a very different set of practices from accumulation through the expansion of wage labour in industry and agriculture. The latter, which dominated processes of capital accumulation in the 1950s and 1960s, gave rise to an oppositional culture (such as that embedded in trade unions and working-class political parties) that produced embedded liberalism. Dispossession, on the other hand, is fragmented and particular—a privatization here, an environmental degradation there, a financial crisis of indebtedness somewhere else. It is hard to oppose all of this specificity and particularity without appeal to universal principles. Dispossession entails the loss of rights. Hence the turn to a universalistic rhetoric of human rights, dignity, sustainable ecological practices, environmental rights, and the like, as the basis for a unified oppositional politics.

This appeal to the universalism of rights is a double-edged sword. It may and can be used with progressive aims in mind. The tradition that is most spectacularly represented by Amnesty International, Médecins sans Frontières, and others cannot be dismissed as a mere adjunct of neoliberal thinking. The whole history of humanism (both of the Western—classically liberal—and various non-Western versions) is too complicated for that. But the limited objectives of many rights discourses (in Amnesty’s case the exclusive focus, until recently, on civil and political as opposed to economic rights) makes it all too easy to absorb them within the neoliberal frame. Universalism seems to work particularly well with global issues such as climate change, the ozone hole, loss of biodiversity through habitat destruction, and the like. But its results in the human rights field are more problematic, given the diversity of political-economic circumstances and cultural practices to be found in the world. Furthermore, it has been all too easy to co-opt human rights issues as ‘swords of empire’ (to use Bartholomew and Breakspear’s trenchant characterization37). So-called ‘liberal hawks’ in the US, for example, have appealed to them to justify imperialist interventions in Kosovo, East Timor, Haiti, and, above all, in Afghanistan and Iraq. They justify military humanism ‘in the name of protecting freedom, human rights and democracy even when it is pursued unilaterally by a self-appointed imperialist power’ such as the US.38 More broadly, it is hard not to conclude with Chandler that ‘the roots of today’s human rights-based humanitarianism lie in the growing consensus of support for Western involvement in the internal affairs of the developing world since the 1970s’. The key argument is that ‘international institutions, international and domestic courts, NGOs or ethics committees are better representatives of the people’s needs than are elected governments. Governments and elected representatives are seen as suspect precisely because they are held to account by their constituencies and, therefore, are perceived to have “particular” interest, as opposed to acting on ethical principle’.39 Domestically, the effects are no less insidious. The effect is to narrow ‘public political debate through legitimizing the developing decision-making role for the judiciary and unelected task forces and ethics committees’. The political effects can be debilitating. ‘Far from challenging the individual isolation and passivity of our atomised societies, human rights regulation can only institutionalise these divisions.’ Even worse, ‘the degraded vision of the social world provided by the ethical discourse of human rights serves, like any elite theory, to sustain the self-belief of the governing class’.40

The temptation in the light of this critique is to eschew all appeal to universals as fatally flawed and to abandon all mention of rights as an untenable imposition of abstract, market-based ethics as a mask for the restoration of class power. While both propositions deserve to be seriously considered, I think it unfortunate to abandon the field of rights to neoliberal hegemony. There is a battle to be fought, not only over which universals and what rights should be invoked in particular situations but also over how universal principles and conceptions of rights should be constructed. The critical connection forged between neoliberalism as a particular set of political-economic practices and the increasing appeal to universal rights of a certain sort as an ethical foundation for moral and political legitimacy should alert us. The Bremer decrees impose a certain conception of rights upon Iraq. At the same time they violate the Iraqi right to self-determination. ‘Between two rights’, Marx famously commented, ‘force decides’.41 If class restoration entails the imposition of a distinctive set of rights, then resistance to that imposition entails struggle for entirely different rights.

The positive sense of justice as a right has, for example, been a powerful provocateur in political movements: struggles against injustice have often animated movements for social change. The inspiring history of the civil rights movement in the US is a case in point. The problem, of course, is that there are innumerable concepts of justice to which we may appeal. But analysis shows that certain dominant social processes throw up and rest upon certain conceptions of justice and of rights. To challenge those particular rights is to challenge the social process in which they inhere. Conversely, it proves impossible to wean society away from some dominant social process (such as that of capital accumulation through market exchange) to another (such as political democracy and collective action) without simultaneously shifting allegiance from one dominant conception of rights and of justice to another. The difficulty with all idealist specifications of rights and of justice is that they hide this connection. Only when they come to earth in relation to some social process do they find social meaning.42

Consider the case of neoliberalism. Rights cluster around two dominant logics of power—that of the territorial state and that of capital.43 However much we might wish rights to be universal, it is the state that has to enforce them. If political power is not willing, then notions of rights remain empty. Rights are, therefore, derivative of and conditional upon citizenship. The territoriality of jurisdiction then becomes an issue. This cuts both ways. Difficult questions arise because of stateless persons, illegal immigrants, and the like. Who is or is not a ‘citizen’ becomes a serious issue defining principles of inclusion and exclusion within the territorial specification of the state. How the state exercises sovereignty with respect to rights is itself a contested issue, but there are limits placed on that sovereignty (as China is discovering) by the global rules embedded in neoliberal capital accumulation. Nevertheless, the nation-state, with its monopoly over legitimate forms of violence, can in Hobbesian fashion define its own bundle of rights and be only loosely bound by international conventions. The US, for one, insists on its right not to be held accountable for crimes against humanity as defined in the international arena at the same time as it insists that war criminals from elsewhere must be brought to justice before the very same courts whose authority it denies in relation to its own citizens.

To live under neoliberalism also means to accept or submit to that bundle of rights necessary for capital accumulation. We live, therefore, in a society in which the inalienable rights of individuals (and, recall, corporations are defined as individuals before the law) to private property and the profit rate trump any other conception of inalienable rights you can think of. Defenders of this regime of rights plausibly argue that it encourages ‘bourgeois virtues’, without which everyone in the world would be far worse off. These include individual responsibility and liability; independence from state interference (which often places this regime of rights in severe opposition to those defined within the state); equality of opportunity in the market and before the law; rewards for initiative and entrepreneurial endeavour; care for oneself and one’s own; and an open marketplace that allows for wide-ranging freedoms of choice of both contract and exchange. This system of rights appears even more persuasive when extended to the right of private property in one’s own body (which underpins the right of the person to freely contract to sell his or her labour power as well as to be treated with dignity and respect and to be free from bodily coercions such as slavery) and the right to freedom of thought, expression, and speech. These derivative rights are appealing. Many of us rely heavily upon them. But we do so much as beggars live off the crumbs from the rich man’s table.

I cannot convince anyone by philosophical argument that the neoliberal regime of rights is unjust. But the objection to this regime of rights is quite simple: to accept it is to accept that we have no alternative except to live under a regime of endless capital accumulation and economic growth no matter what the social, ecological, or political consequences. Reciprocally, endless capital accumulation implies that the neoliberal regime of rights must be geographically expanded across the globe by violence (as in Chile and Iraq), by imperialist practices (such as those of the World Trade Organization, the IMF, and the World Bank) or through primitive accumulation (as in China and Russia) if necessary. By hook or by crook, the inalienable rights of private property and the profit rate will be universally established. This is precisely what Bush means when he says the US dedicates itself to extend the sphere of freedom across the globe.

But these are not the only rights available to us. Even within the liberal conception as laid out in the UN Charter there are derivative rights, such as freedoms of speech and expression, of education and economic security, rights to organize unions, and the like. Enforcing these rights would have posed a serious challenge to neoliberalism. Making these derivative rights primary and the primary rights of private property and the profit rate derivative would entail a revolution of great significance in political-economic practices. There are also entirely different conceptions of rights to which we may appeal—of access to the global commons or to basic food security, for example. ‘Between equal rights force decides.’ Political struggles over the proper conception of rights, and even of freedom itself, move centre-stage in the search for alternatives.