In his annual message to Congress in 1935, President Roosevelt made clear his view that excessive market freedoms lay at the root of the economic and social problems of the 1930s Depression. Americans, he said, ‘must forswear that conception of the acquisition of wealth which, through excessive profits, creates undue private power’. Necessitous men are not free men. Everywhere, he argued, social justice had become a definite goal rather than a distant ideal. The primary obligation of the state and its civil society was to use its powers and allocate its resources to eradicate poverty and hunger and to assure security of livelihood, security against the major hazards and vicissitudes of life, and the security of decent homes.1 Freedom from want was one of the cardinal four freedoms he later articulated as grounding his political vision for the future. These broad themes contrast with the far narrower neoliberal freedoms that President Bush places at the centre of his political rhetoric. The only way to confront our problems, Bush argues, is for the state to cease to regulate private enterprise, for the state to withdraw from social provision, and for the state to foster the universalization of market freedoms and of market ethics. This neoliberal debasement of the concept of freedom ‘into a mere advocacy of free enterprise’ can only mean, as Karl Polanyi points out, ‘the fullness of freedom for those whose income, leisure and security need no enhancing, and a mere pittance of liberty for the people, who may in vain attempt to make use of their democratic rights to gain shelter from the power of the owners of property’.2

What is so astonishing about the impoverished condition of contemporary public discourse in the US, as well as elsewhere, is the lack of any serious debate as to which of several divergent concepts of freedom might be appropriate to our times. If it is indeed the case that the US public can be persuaded to support almost anything in the name of freedom, then surely the meaning of this word should be subjected to the deepest scrutiny. Unfortunately, contemporary contributions either take a purely neoliberal line (as does the political commentator Fareed Zakaria, who purports to demonstrate irrefutably that an excess of democracy is the main threat to individual liberty and freedom) or else trim their sails so closely to dominant neoliberal winds as to offer little in the way of counterpoint to the neoliberal logic. Such is, regrettably, the case with Amartya Sen (who finally, and deservedly, won a Nobel Prize in Economics but only after the neoliberal banker who had long chaired the Nobel committee was forced to step down). Sen’s Development as Freedom, by far the most sensitive contribution to the discussion over recent years, unfortunately wraps up important social and political rights in the mantle of free market interactions.3 Without a liberal-style market, Sen seems to say, none of the other freedoms can work. A substantial segment of the US public seems for its part to accept that the distinctively neoliberal freedoms that Bush and his fellow Republicans promote are all there is. These freedoms, we are told, are worth dying for in Iraq and the US ‘as the greatest power on earth’ has ‘an obligation’ to help spread them everywhere. The conferral of the prestigious Presidential Medal of Freedom on Paul Bremer, architect of the neoliberal reconstruction of the Iraqi state, says much about what this segment of the US public stands for.

Roosevelt’s entirely reasonable conceptions sound positively radical by contemporary standards, which probably explains why they have not been articulated by the current Democratic Party as a counterpoint to the narrow entrepreneurial conceptions that Bush holds so dear. Roosevelt’s vision does have an impressive genealogy in humanist thinking. Karl Marx, for example, also held the outrageously radical view that an empty stomach was not conducive to freedom. ‘The realm of freedom’, he wrote, ‘actually begins only where labour which is determined by necessity and of mundane considerations ceases’, adding, for good measure, that it therefore ‘lies beyond the sphere of actual material production’. He well understood that we could never free ourselves from our metabolic relations with nature or our social relations with each other, but we could at least aspire to build a social order in which the free exploration of our individual and species potential became a real possibility.4 By Marx’s standard of freedom, and almost certainly by that laid out by Adam Smith in his Theory of Moral Sentiments, neoliberalization would surely be regarded as a monumental failure. For those left or cast outside the market system—a vast reservoir of apparently disposable people bereft of social protections and supportive social structures—there is little to be expected from neoliberalization except poverty, hunger, disease, and despair. Their only hope is somehow to scramble aboard the market system either as petty commodity producers, as informal vendors (of things or labour power), as petty predators to beg, steal, or violently secure some crumbs from the rich man’s table, or as participants in the vast illegal trade of trafficking in drugs, guns, women, or anything else illegal for which there is a demand. This is the Malthusian world blamed on its victims in works such as political journalist Robert Kaplan’s influential essay on ‘the coming anarchy’.5 It never crosses Kaplan’s mind that neoliberalization and accumulation by dispossession have anything to do with any of the conditions he describes. The incredible number of anti-IMF riots on record, to say nothing of the crime waves that swept through New York City, Mexico City, Johannesburg, Buenos Aires, and many other major cities in the wake of structural adjustment and neoliberal reform, should surely have alerted him.6 At the other end of the wealth scale, those thoroughly incorporated within the inexorable logic of the market and its demands find that there is little time or space in which to explore emancipatory potentialities outside what is marketed as ‘creative’ adventure, leisure, and spectacle. Obliged to live as appendages of the market and of capital accumulation rather than as expressive beings, the realm of freedom shrinks before the awful logic and the hollow intensity of market involvements.

It is in this context that we can better understand the emergence of diverse oppositional cultures that from both within and without the market system either explicitly or tacitly reject the market ethic and the practices that neoliberalization imposes. Within the US, for example, there is a sprawling environmental movement hard at work promoting alternative visions of how to better connect political and ecological projects. There is also a burgeoning anarchist movement among the young, one wing of which—‘the primitivists’—believes that the only hope for humanity is to return to that stage of hunter-gathering that preceded the rise of civilization and, in effect, start human history all over again. Others, influenced by movements like CrimeThink and authors such as Derrick Jensen, seek to purge themselves of all traces of incorporation into the capitalist market logic.7 Others seek a world of mutual support through, for example, the formation of local economic trading systems (LETS) with their own ‘local moneys’ even in the very heart of a neoliberalizing capitalism. Religious variants of this secular trend are also flourishing, from the US through Brazil to rural China, where religious sects are reported to be forming at an astonishing rate.8 And many sectors of organized religion, the evangelical Christians, Wahabi Islam, and some variants of Buddhism and Confucianism, preach an intensely anti-market and specifically anti-neoliberal stance. Then there are all those social movements struggling against specific aspects of neoliberal practices, particularly accumulation by dispossession, that either resist predatory neoliberalism (such as the Zapatista revolutionary movement in Mexico) or seek access to resources hitherto denied them (such as the landless peasant movement in Brazil or those leading the factory occupations in Argentina). Centre-left coalitions, openly critical of neoliberalization, have taken over political power, and seem poised to deepen and extend their influence all over Latin America. The surprise success of the Congress Party returning to power in India with a left-wing mandate is yet another case in point. The desire for an alternative to neoliberalization is abundantly in evidence.9

There are even signs of discontent within ruling policy circles as to the wisdom of neoliberal propositions and prescriptions. Some earlier enthusiasts (such as the economists Jeffrey Sachs, Joe Stiglitz, and Paul Krugman) and participants (such as George Soros) have now turned critical, even to the point of suggesting some sort of return to a modified Keynesianism or a more ‘institutional’ approach to the solution of global problems—everything from better regulatory structures of global governance to closer supervision of the reckless speculations of the financiers.10 In recent years there have been not only insistent calls but also major blueprints for the reform of global governance.11 A revival of academic and institutional interest in the cosmopolitan ethic (‘an injury to one is an injury to all’) as a basis for global governance has also occurred and, problematic though its overly simplistic universalisms may be, it is not entirely bereft of merit.12 It is exactly in such a spirit that heads of states periodically assemble, as 189 of them did at the Millennium Summit in 2000, to sign pious declarations of their collective commitments to eradicate poverty, illiteracy, and disease in short order. But commitments to eradicate illiteracy, for example, sound hollow against the background of substantial and continuing declines in the proportion of national product going into public education almost everywhere in the neoliberal world.

Objectives of this sort cannot be realized without challenging the fundamental power bases upon which neoliberalism has been built and to which the processes of neoliberalization have so lavishly contributed. This means not only reversing the withdrawal of the state from social provision but also confronting the overwhelming powers of finance capital. Keynes held the ‘coupon clippers’, who parasitically lived off dividends and interest, in contempt and looked forward to what he called ‘the euthanasia of the rentier’ as a necessary condition for not only achieving some modicum of economic justice but also avoiding the devastation of those periodic crises to which capitalism was prone. The virtue of the Keynesian compromise and the embedded liberalism constructed after 1945 was that it went some way to realizing those goals. The advent of neoliberalization, by contrast, has celebrated the role of the rentier, cut taxes on the rich, privileged dividends and speculative gains over wages and salaries, and unleashed untold though geographically contained financial crises, with devastating effects on employment and life chances in country after country. The only way to realize the pious goals is to confront the powers of finance and to roll back the class privileges that have been built thereon. But there is no sign anywhere among the powers that be of doing anything of the sort.

With respect to the return to Keynesianism, however, the Bush administration, as I earlier pointed out, has beaten everyone to the gun, being prepared to countenance spiralling federal deficits stretching on endlessly into the future. Contrary to traditional Keynesian prescriptions, however, the redistributions in this case are upwards towards the large corporations, their wealthy CEOs, and their financial/legal advisers at the expense of the poor, the middle classes, and even ordinary shareholders (including the pension funds), to say nothing of future generations. But the fact that traditional Keynesianism can be bowdlerized and turned upside-down in this fashion should not surprise us. For, as I have also already shown, there is abundant evidence that neoliberal theory and rhetoric (particularly the political rhetoric concerning liberty and freedom) has also all along primarily functioned as a mask for practices that are all about the maintenance, reconstitution, and restoration of elite class power. The exploration of alternatives has, therefore, to move outside the frames of reference defined by this class power and market ethics while staying soberly anchored in the realities of our time and place. And these realities point to the possibility of a major crisis within the heartland of the neoliberal order itself.

The internal economic and political contradictions of neoliberalization are impossible to contain except through financial crises. So far these have proven locally damaging but globally manageable. The manageability depends, of course, upon departing substantially from neoliberal theory. The mere fact that the two main powerhouses of the global economy—the US and China—are deficit financing up to the hilt is, surely, a compelling sign that neoliberalism is in trouble if not actually dead as a viable theoretical guide to ensuring the future of capital accumulation. This will not prevent it from continuing to be deployed as a rhetoric to sustain the restoration/creation of elite class power. But when income and wealth inequalities reach a point—as they have today—close to that which preceded the crash of 1929, then the economic imbalances become so chronic as to be in danger of generating a structural crisis. Unfortunately, regimes of accumulation rarely if ever dissolve peacefully. Embedded liberalism arose out of the ashes of the Second World War and the Great Depression. Neoliberalization was born in the midst of the 1970s crisis of accumulation, emerging from the womb of a played-out embedded liberalism with enough violence to support Karl Marx’s observation that violence is invariably the midwife of history. The authoritarian option of neoconservatism is now emerging in the US. The violent assault upon Iraq abroad and incarceration policies at home signal a new-found determination on the part of the US ruling elite to redefine the global and domestic order to its own advantage. It therefore behoves us to consider very carefully whether and how a crisis of the neoliberal regime might unfold.

The financial crises that have so frequently preceded the predatory raiding of whole state economies by superior financial powers have usually been characterized by chronic economic imbalances. The typical signs are soaring and uncontrollable internal budgetary deficits, a balance of payments crisis, rapid currency depreciation, unstable valuations of internal assets (for example in property and financial markets), rising inflation, rising unemployment with falling wages, and capital flight. Of these seven main indicators the US now has the distinction of scoring high on the first three and there are serious concerns with respect to the fourth. The current ‘jobless recovery’ and stagnant wages suggest incipient problems with the sixth. Such a mix of indicators elsewhere would almost certainly have necessitated IMF intervention (and IMF economists are on record, as are both former and current Federal Reserve chairs Volcker and Greenspan, complaining that the economic imbalances within the US are threatening global stability).13 But since the US dominates the IMF this means nothing more than that the US should discipline itself, and that appears unlikely. The big questions are: will global markets do the disciplining (as according to neoliberal theory they should), and if so how and with what effects?

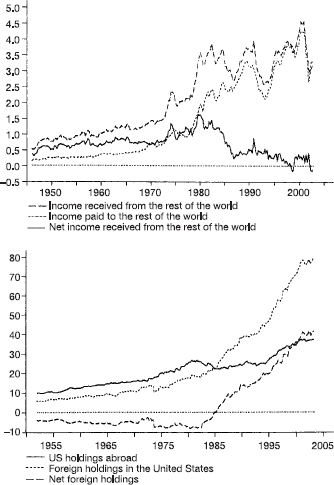

It is unthinkable but not impossible that the US will become like Argentina in 2001 overnight. The consequences would, however, be catastrophic not only internally but also for global capitalism. Since almost everyone who constitutes the capitalist class and its global managers everywhere is well aware of this fact, the rest of the world is currently willing (in some cases reluctantly) to continue to support the US economy with sufficient credits to sustain its profligate ways. Private capital flows into the US have, however, seriously diminished (except to buy up relatively cheap assets given the fall in the value of the dollar) and so it is the world’s central bankers—particularly in Japan and China—that now increasingly own America Inc. For them to withdraw support from the US would be devastating for their own economies since the US is still a major market for their exports. But there is a limit to which this system can progress. Already nearly one-third of stock assets on Wall Street and nearly half of US Treasury bonds are owned by foreigners, and the dividends and interest flowing out to foreign owners are now roughly equivalent to, if not more than, the tribute that US corporations and financial operations are extracting from abroad (Figure 7.1). This balance of benefits will turn more strongly negative the more the US borrows, and it is now borrowing from abroad at a rate approaching $2 billion per day. Furthermore, if US interest rates rise (as at some point they must) then what happened to Mexico after the Volcker interest rate increase in 1979 starts to loom as a real problem. The US will soon be paying out far more to service its debt to the rest of the world than it brings in.14 This extraction of wealth from the US will not be welcome domestically. The perpetual increases in debt-financed consumerism that have been the foundation of social peace in the US since 1945 would have to stop.

The imbalances seem not to trouble the Bush administration, judging by cavalier statements to the effect that the current account deficit, if it is a problem, can easily be dealt with by people buying US-made goods (as if such goods are readily available and cheap enough and as if nominally US-made goods do not have a high foreign-input component). If this really happened then Wal-Mart would be put out of business. The budget deficit, Bush says, can easily be dealt with without raising taxes by curbing domestic programmes (as if there are any large discretionary programmes left to dismantle). Vice-President Cheney’s remark that ‘Reagan taught us that budget deficits do not matter’ is alarming, because what Reagan also taught is that running up deficits is a way to force retrenchment in public expenditures and that attacking the standard of living of the mass of the population while feathering the nests of the rich can best be accomplished in the midst of financial turmoil and crisis. If, furthermore, we ask the general question, ‘Who has actually benefited from the numerous financial crises that have cascaded from one country to another in wave after wave of catastrophic deflations, inflations, capital flights and structural adjustments since the late 1970s?’, the weak commitment of the current US administration to fending off a fiscal crisis in spite of all the warning signs becomes more readily understandable. In the wake of a financial crash, the ruling elite may hope to emerge even more empowered than before.

Figure 7.1 The deteriorating position of the US in global capital and ownership flows, 1960–2002: inflow and outflow of US investments (above) and change in foreign ownership shares (below)

Source: Duménil and Lévy, ‘The Economics of US Imperialism’.

It may be that the US economy can finesse the current imbalances (much as it did after 1945) and grow its own way out of its self-inflicted problems. There are some weak signs that point in that direction. Current policy, however, seems to be based at best on the Micawber principle that something good is bound to turn up. Leaders of many US corporations, after all, managed to live in their own fantasy world before seemingly invulnerable entities like Enron came crashing down. This could also be the fate of America Inc., and the fantasy-like statements from the current leadership ought to trouble everyone who has the interests of the country at heart. It could also be that the US ruling elite calculates it can survive a global fiscal crisis in good shape and use it to complete its agenda of total domestic domination. But such a calculation could turn out to be a monumental error. The result may be to hasten the transfer of hegemony to some other regional economy (most probably based in Asia) while undercutting the ruling elite’s capacity to dominate both internally and externally.

The most immediate question concerns what sort of crisis might serve the US best in resolving its own situation, for that choice is indeed within the realm of policy options. In presenting these options it is important to recall that the US has not been immune to financial difficulties over the last twenty years. The stock market crash of 1987 deleted nearly 30 per cent of asset values, and at the trough of the crash that followed the bursting of the new economy bubble in the late 1990s more that $8 trillion in paper assets was lost, before the recovery to former levels. The bank and savings and loan failures of 1987 cost nearly $200 billion to remedy, and in that year matters became so bad that William Isaacs, chairman of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, warned that ‘the US may be headed towards the nationalization of banking’. And the huge bankruptcies of Long Term Capital Management, Orange County, and others who speculated and lost, followed by the collapse of several major companies in 2001–2 in the midst of astonishing accounting lapses, not only cost the public dear but also demonstrated how fragile and fictitious much of neoliberal financialization has become. The fragility is by no means confined to the US, of course. Most countries, including China, face financial volatility and uncertainty. The debt of the developing world, for example, rose ‘from $580 billion in 1980 to $2.4 trillion in 2002 and much of it is unrepayable. In 2002 there was a net outflow of $340 billion in servicing this debt, compared to overseas development aid of $37 billion.’15 In some cases the debt service exceeds foreign earnings and, understandably, some countries, such as Argentina, are exhibiting considerable recalcitrance in the face of their creditors.

Consider, then, the two worst-case scenarios from the standpoint of the US. A short burst of hyper-inflation would provide one way to delete the outstanding international and consumer debt. The US would in effect pay off its debts to Japan, China, and the others in grossly depreciated dollars. Such inflationary confiscation would not be well received in the rest of the world (though it could do little about it since sending gunboats up the Potomac is not a feasible option). Hyper-inflation would also destroy savings, pensions, and much else internally within the US. It would entail reversing the monetarist course that Volcker and Greenspan have generally followed. At the least hint of such a switch away from monetarism (in effect declaring neoliberalism dead), however, central bankers everywhere would almost certainly create a run on the dollar and thus prematurely precipitate a crisis of capital flight that would be unmanageable by US financial institutions alone. The US dollar would lose all credibility as a global reserve currency and lose all the future benefits (for example of seignorage—the power to print money) of being the dominant financial power. That mantle would then be assumed either by Europe or East Asia or both (the world’s central bankers are already exhibiting a preference to hold more of their balances in euros). A more modest return to inflation may also be on the cards, for there is abundant evidence that inflation is by no means the inherent evil that monetarists describe, and that some modest relaxation of monetary targets (as Thatcher showed in the more pragmatic phases of her drive towards neoliberalization) is workable.

The other option is for the US to accept a long-drawn-out period of deflation of the sort that Japan has been experiencing since 1989. This would create serious global problems unless other economies—with China, perhaps coupled with India, obviously in the vanguard—can pick up the slack of lagging dynamism. But, as we have seen, the China option is deeply problematic for both economic and political reasons. The internal imbalances in China are serious, and mainly take the form of excess capacity— everything from too many airports to too many car plants. This overcapacity would become even more palpable in the event of any prolonged stagnation in US consumer markets. The outstanding debt in China (in the form of non-performing bank loans), on the other hand, is by no means as monumental as that in the US. The dangers in the Chinese case are as much political as economic. But the extraordinary dynamism within the Asian complex of economies may be sufficient to propel capital accumulation well into the future, though almost certainly with remarkably deleterious effects on the quality of the environment as well as on the traditional US position as top dog in the global order. Whether or not the US will meekly surrender its hegemonic position is an open question. It will almost certainly maintain military domination even as its dominant position in almost every other significant realm of political-economic power diminishes. Whether or not the US will seek to use its military superiority, as it has done in Iraq, for political and economic purposes will then depend crucially upon the internal dynamics within the US itself.

Long-drawn-out deflation will be extremely hard for the US to absorb internally. If the debt problems of the federal government and of financial institutions are to be resolved without threatening the wealth of elite classes, then ‘confiscatory deflation’ (deeply inconsistent with neoliberalism) of the sort Argentina experienced (hints of which could be found in the US savings and loan crisis of the late 1980s when many depositors could not get access to their moneys) will be the only option. The substantial public programmes that still exist (Social Security and Medicare), pension rights, and asset values (property and savings in particular) will likely be the first victims, and under such conditions popular consent will almost certainly begin to fray at the seams. The big question would then be how extensive and expressive the discontent is, and how it might be handled.

The consolidation of neoconservative authoritarianism then emerges as one potential answer. Neoconservatism, I argued in Chapter 3, sustains the neoliberal drive towards the construction of asymmetric market freedoms but makes the anti-democratic tendencies of neoliberalism explicit through a turn into authoritarian, hierarchical, and even militaristic means of maintaining law and order. In The New Imperialism I explored Hannah Arendt’s thesis that militarization abroad and at home inevitably go hand in hand, and concluded that the international adventurism of the neoconservatives, long planned and legitimized after the 9/11 attacks, had as much to do with asserting domestic control over a fractious and much-divided body politic in the US as it did with a geopolitical strategy of maintaining global hegemony through control over oil resources. Fear and insecurity both internally and externally were all too easily—and in this case successfully when it came to re-election time—manipulated for political purposes.16

But the neoconservatives also assert a higher moral purpose, at the core of which lies an appeal to a nationalism that has long had, as we saw in Chapter 3, a fraught relationship with neoliberalization. US nationalism has, however, a dual character. On the one hand it presumes that it is the God-given (and the religious invocation is deliberate) manifest destiny of the US to be the greatest power on earth (if not number one in everything from baseball to the Olympics) and that, as a beacon of freedom, liberty, and progress, it has been and continues to be universally admired and considered worthy of emulation. Everyone, it is said, wants to either live in or be like the US. The US therefore benevolently and generously gives freely of its resources and its values and culture to the rest of the world, in the cause of conferring the privilege of Americanization and American values on all and sundry. But US nationalism also has a darker side in which paranoia about fearful threats from enemies and evil forces from outside take over. The fear is of foreigners and of immigrants, of outside agitators, and now, of course, of ‘terrorists’. This leads to the internal circling of wagons and the closing down of civil liberties and freedoms in episodes like the persecution of anarchists in the 1920s, the McCarthyism of the 1950s directed against communists and their sympathizers, the paranoid style of Richard Nixon towards opponents of the Vietnam War and, since 9/11, the tendency to characterize all critics of administration policies as aiding and abetting the enemy. This kind of nationalism easily fuses with racism (most particularly now towards Arabs), the restriction of civil liberties (the Patriot Act), the curbing of press freedoms (the gaoling of journalists for not revealing their sources), and the embrace of incarceration and the death penalty to deal with malfeasance. Externally this nationalism leads to covert action and now to preemptive wars to eradicate anything that seems like the remotest threat to the hegemony of US values and the dominance of US interests. Historically, these two strains of nationalism have always coexisted.17 They have sometimes been in open conflict with each other (in the divisions over how to deal with the revolutions in Central America in the 1980s, for example).

After 1945, the US was in a position to project the first assumption, always self-interestedly and sometimes benevolently (as in the Marshall Plan, which helped revive war-torn European economies after 1945), onto the world, at the same time as it was engaging with McCarthyism at home. But the end of the Cold War has changed everything. The rest of the world no longer looks to the US for military protection and has broken free from US domination in almost everything. The US has never been so isolated from the rest of the world politically, culturally, and even militarily as now. And this isolation is not, as it was in the past, the product of a US withdrawal from world affairs but a consequence of its excessive and unilateralist interventionism. It also comes at a time when the US economy is more interwoven into global production and financial networks than ever before. The result has been a dangerous fusion of the two forms of nationalism. Through the formulation of the doctrine of ‘pre-emptive strike’ against foreign nations in the midst of a supposedly all-threatening global war on terror, the US public can imagine that it is struggling benevolently to bring freedom and democracy everywhere (particularly in Iraq) while playing out its darkest fears regarding some unknown and hidden enemy that is threatening its very existence. The rhetoric of the Bush administration and of the neoconservatives plays indefatigably upon both themes. This served Bush well in his successful re-election campaign.

In The New Imperialism, I argued that there are many signs that US hegemony is crumbling. It lost its dominance in global production during the 1970s and its power in global finance began to erode in the 1990s. Its technological leadership role is being challenged and its hegemony with respect to culture and moral leadership is waning fast, leaving its military strength as its only clear weapon of global domination. Even its military might is confined to what can be done with high-tech destructive power wielded from thirty thousand feet up. Iraq has demonstrated its limits on the ground. The transition to some new hegemonic structure in global capitalism poses a choice for the US: to manage the transition peacefully or through catastrophe.18 The current stance of US ruling elites points more towards the latter rather than to the former course. Nationalism within the US can all too easily be rallied to the idea that the economic difficulties of either hyper-inflation or long-drawn-out deflation are attributable to others, such as China and East Asia or to OPEC and Arab states that fail to respond to its profligate demands for energy in an appropriate way. The doctrine of pre-emptive strike is already in place and the destructive capacities are readily at hand. A beleaguered and plainly threatened US state has, the argument goes, an obligation to defend itself, its values, and its way of life by military means if necessary. Such a catastrophic and in my judgement suicidal calculation is not beyond the capacity of the current US leadership. That leadership has already demonstrated its penchant to suppress internal dissent and in this it has garnered considerable popular support. A substantial proportion of the US populace, after all, views the US Bill of Rights as a communist-inspired document, while others, a minority to be sure, welcomes anything that smacks of Armageddon. The anti-terrorism laws, the abandonment of the Geneva Conventions in Guantánamo Bay, and the readiness to depict any oppositional force as ‘terrorist’ are warning signs.

Fortunately, there is a substantial opposition that can be and to some degree already is mobilized within the US against such catastrophic and suicidal tendencies. Unfortunately, as it is currently constituted this opposition is fragmented, rudderless, and lacking coherent organization. To some degree this is the consequence of self-inflicted wounds within the labour movement, within the movements that have broadly embraced identity politics, and within all those postmodern intellectual currents that accord, without knowing it, with the White House line that truth is both socially constructed and a mere effect of discourse. Terry Eagle-ton’s critique of Lyotard’s Postmodern Condition, in which ‘there can be no difference between truth, authority and rhetorical seductiveness; he who has the smoothest tongue or the raciest story has the power’, bears repeating. It is, I would argue, even more relevant to our times than when I cited it back in 1989.19 The story-telling from the White House and the spin-meistering from Downing Street have to be rebutted then stopped if we are to find any kind of exit from our current impasse. There is a reality out there and it is catching up with us fast. But where should we strive to go? If we were able to mount that wondrous horse of freedom, where would we seek to ride it?

Alternatives

There is a tendency to take up the issue of alternatives as if it is about describing some blueprint for a future society and an outline of the way to get there. Much can be gained from such exercises. But we first need to initiate a political process that can lead us to a point where feasible alternatives, real possibilities, become identifiable. There are two main paths to take. We can engage with the plethora of oppositional movements actually existing and seek to distil from and through their activism the essence of a broad-based oppositional programme. Or we can resort to theoretical and practical enquiries into our existing condition (of the sort I have engaged in here) and seek to derive alternatives through critical analysis. To take the latter path in no way presumes that existing oppositional movements are wrong or somehow defective in their understandings. By the same token, oppositional movements cannot presume that analytical findings are irrelevant to their cause. The task is to initiate dialogue between those taking each path and thereby to deepen collective understandings and define more adequate lines of action.

Neoliberalization has spawned a swath of oppositional movements both within and outside its compass. Many of these movements are radically different from the worker-based movements that dominated before 1980.20 I say ‘many’, but not ‘all’. Traditional worker-based movements are by no means dead even in the advanced capitalist countries where they have been much weakened by the neoliberal onslaught on their power. In South Korea and South Africa vigorous labour movements arose during the 1980s and in much of Latin America working-class parties are flourishing if not in power. In Indonesia a fledgling labour movement of great potential importance is struggling to be heard. The potential for labour unrest in China is immense though unpredictable. And it is not clear either that the mass of the working people in the US, who have over this last generation often willingly voted against their own material interests for reasons of cultural nationalism, religion, and moral values, will for ever stay locked into such a politics by the machinations of Republicans and Democrats alike. Given the volatility, there is no reason to rule out the resurgence of popular social democratic or even populist anti-neoliberal politics within the US in future years.

But struggles against accumulation by dispossession are fomenting quite different lines of social and political struggle.21 Partly because of the distinctive conditions that give rise to such movements, their political orientation and modes of organization depart markedly from those typical of social democratic politics. The Zapatista rebellion in Chiapas, Mexico, for example, did not seek to take over state power or accomplish a political revolution; it sought instead a more inclusionary politics. The idea is to work through the whole of civil society in a more open and fluid search for alternatives that would look to the specific needs of the different social groups and allow them to improve their lot.

Organizationally, it tended to avoid avant-gardism and refused to take on the form of a political party. It preferred instead to remain a social movement within the state, attempting to form a political power bloc in which indigenous cultures would be central rather than peripheral. Many environmental movements—such as those for environmental justice—proceed in the same way.

The effect of such movements has been to shift the terrain of political organization away from traditional political parties and labour organizing into a less focused political dynamic of social action across the whole spectrum of civil society. What such movements lose in focus they gain in terms of direct relevance to particular issues and constituencies. They draw strength from being embedded in the nitty-gritty of daily life and struggle, but in so doing they often find it hard to extract themselves from the local and the particular to understand the macro-politics of what neoliberal accumulation by dispossession and its relation to the restoration of class power was and is all about.

The variety of these struggles is simply stunning, so much so that it is hard sometimes to even imagine connections between them. They are all part of a volatile mix of protest movements that have swept the world and increasingly grabbed the headlines during and since the 1980s. These movements and revolts have sometimes been crushed with ferocious violence, for the most part by state powers acting in the name of ‘order and stability’. Elsewhere they have degenerated into inter-ethnic violence and civil war as accumulation by dispossession produced intense social and political rivalries. The divide-and-rule tactics of ruling elites or competition between rival factions (for example French versus US interests in some African countries) have more often than not been central to these struggles. Client states, supported militarily or in some instances with special forces trained by the major military apparatuses (led by the US, with Britain and France playing a minor role) often take the lead in a system of repressions and liquidations to ruthlessly check activist movements challenging accumulation by dispossession in many parts of the developing world.

The movements themselves have produced a plethora of ideas regarding alternatives. Some seek to de-link wholly or partially from the overwhelming powers of neoliberal globalization. Others (such as the ‘Fifty Years Is Enough’ movement) seek global social and environmental justice by reform or dissolution of powerful institutions such as the IMF, the WTO, and the World Bank (though, interestingly, the core power of the US Treasury is rarely mentioned). Still others (particularly environmentalists such as Greenpeace) emphasize the theme of ‘reclaiming the commons’, thereby signalling deep continuities with struggles of long ago as well as with struggles waged throughout the bitter history of colonialism and imperialism. Some (such as Hardt and Negri) envisage a multitude in motion, or a movement within global civil society, to confront the dispersed and decentred powers of the neoliberal order (construed as ‘Empire’), while others more modestly look to local experiments with new production and consumption systems (such as the LETS) animated by completely different kinds of social relations and ecological practices. There are also those who put their faith in more conventional political party structures (for example the Workers Party in Brazil or the Congress Party in India in alliance with communists) with the aim of gaining state power as one step towards global reform of the economic order. Many of these diverse currents now come together at the World Social Forum in an attempt to define their commonalities and to build an organizational power capable of confronting the many variants of neoliberalism and of neoconservatism. A flurry of literature suggesting that ‘another world is possible’ has emerged. This summarizes and on occasion attempts to synthesize the diverse ideas arising from the various social movements occurring in all parts of the world. There is much here to admire and to inspire.

But what sorts of conclusions can be derived from an analytical exercise of the sort here constructed? To begin with, the whole history of embedded liberalism and the subsequent turn to neoliberalization indicates the crucial role played by class struggle in either checking or restoring elite class power. Though it has been effectively disguised, we have lived through a whole generation of sophisticated strategizing on the part of ruling elites to restore, enhance, or, as in China and Russia, to construct an overwhelming class power. The further turn to neoconservatism is illustrative of the lengths to which economic elites will go and the authoritarian strategies they are prepared to deploy in order to sustain their power. And all of this occurred in decades when working-class institutions were in decline and when many progressives were increasingly persuaded that class was a meaningless or at least long defunct category. In this, progressives of all stripes seem to have caved in to neoliberal thinking since it is one of the primary fictions of neoliberalism that class is a fictional category that exists only in the imagination of socialists and crypto-communists. In the US in particular, the phrase ‘class warfare’ is now confined to the right-wing media (for example the Wall Street Journal) to denigrate all forms of criticism that threaten to undermine a supposedly unified and coherent national purpose (i.e. the restoration of upper-class power!). The first lesson we must learn, therefore, is that if it looks like class struggle and acts like class war then we have to name it unashamedly for what it is. The mass of the population has either to resign itself to the historical and geographical trajectory defined by overwhelming and ever-increasing upper-class power, or respond to it in class terms.

To put it this way is not to wax nostalgic for some lost golden age when some fictional category like ‘the proletariat’ was in motion. Nor does it necessarily mean (if it ever should have) that there is some simple conception of class to which we can appeal as the primary (let alone exclusive) agent of historical transformation. There is no proletarian field of utopian Marxian fantasy to which we can retire. To point to the necessity and inevitability of class struggle is not to say that the way class is constituted is determined or even determinable in advance. Popular as well as elite class movements make themselves, though never under conditions of their own choosing. And those conditions are full of the complexities that arise out of race, gender, and ethnic distinctions that are closely interwoven with class identities. The lower classes are highly racialized and the increasing feminization of poverty has been a notable feature of neoliberalization. The neoconservative assault on women’s and reproductive rights, which, interestingly, got into high gear at the end of the 1970s when neoliberalism first came to prominence, is a key element in its notion of a proper moral order built upon a very particular conception of the family.

Analysis also shows how and why popular movements are currently bifurcated. On the one hand there are movements around what I call ‘expanded reproduction’ in which the exploitation of wage labour and conditions defining the social wage are the central issues. On the other hand there are movements against accumulation by dispossession. These include resistance to classic forms of primitive accumulation (such as displacement of peasant populations from the land); to the brutal withdrawal of the state from all social obligations (except surveillance and policing); to practices destructive of cultures, histories, and environments; and to the ‘confiscatory’ deflations and inflations wrought by the contemporary forms of finance capital in alliance with the state. Finding the organic link between these different movements is an urgent theoretical and practical task. But our analysis has also shown that this can only be done by tracking the dynamics of a capital accumulation process that is marked by volatile as well as deepening uneven geographical developments. This unevenness, as we saw in Chapter 4, actively promotes the spread of neoliberalization through inter-state competition. Part of the task of a rejuvenated class politics is to turn this uneven geographical development into an asset rather than a liability. The divide-and-rule politics of ruling-class elites must be confronted with alliance politics on the left sympathetic to the recuperation of local powers of self-determination.

But analysis also points up exploitable contradictions within the neoliberal and neoconservative agendas. The widening gap between rhetoric (for the benefit of all) and realization (the benefit of a small ruling class) is now all too visible. The idea that the market is about competition and fairness is increasingly negated by the fact of the extraordinary monopolization, centralization, and internationalization of corporate and financial power. The startling increase in class and regional inequalities, both within states (such as China, Russia, India, and Southern Africa) and internationally between states, poses a serious political problem that can no longer be swept under the rug as something ‘transitional’ on the way to a perfected neoliberal world. The more neoliberalism is recognized as a failed utopian rhetoric masking a successful project for the restoration of ruling-class power, the more the basis is laid for a resurgence of mass movements voicing egalitarian political demands and seeking economic justice, fair trade, and greater economic security.

The rise of rights discourses, of the sort considered in the previous chapter, presents opportunities as well as problems. Even appeal to the conventional liberal notions of rights can form a powerful ‘sword of resistance’ from which to critique neoconservative authoritarianism, particularly given the way in which ‘the war on terror’ has everywhere (from the US to China and Chechnya) been deployed as an excuse to diminish civil and political liberties. The rising call to acknowledge Iraqi rights to self-determination and sovereignty is a powerful weapon with which to check US imperial designs there. But alternative rights can also be defined. The critique of endless capital accumulation as the dominant process that shapes our lives entails critique of those specific rights— the right to individual private property and the profit rate—that ground neoliberalism and vice versa. I have argued elsewhere for an entirely different bundle of rights, to include the right to life chances, to political association and ‘good’ governance, for control over production by the direct producers, to the inviolability and integrity of the human body, to engage in critique without fear of retaliation, to a decent and healthy living environment, to collective control of common property resources, to the production of space, to difference, as well as rights inherent in our status as species beings.22 To propose different rights to those held sacrosanct by neoliberalism carries with it, however, the obligation to specify an alternative social process within which such alternative rights can inhere.

A similar argument can be made against the neoconservative assertion of a moral high ground for its authority and legitimacy. Ideals of moral community and of a moral economy are not foreign to progressive movements historically. Many of those, like the Zapatistas, now struggling against accumulation by dispossession are actively articulating the desire for alternative social relations in moral economy terms. Morality is not a field to be defined solely by a reactionary religious right mobilized under the hegemony of media and articulated through a political process dominated by corporate money power. The restoration of ruling-class power under a welter of confusing moral arguments has to be confronted. The so-called ‘culture wars’—however misguided some of them may have been—cannot be sloughed off as some unwelcome distraction (as some on the traditional left argue) from class politics. Indeed, the rise of moral argument among the neoconservatives attests not only to the fear of social dissolution under an individualizing neoliberalism but also to the broad swaths of moral repugnance already in motion against the alienations, anomie, exclusions, marginalizations, and environmental degradations produced through the practices of neoliberalization. The transformation of that moral repugnance towards a pure market ethic into cultural and then political resistance is one of the signs of our times that needs to be read correctly rather than shunted aside. The organic link between such cultural struggles and the struggle to roll back the overwhelming consolidation of ruling-class power calls for theoretical and practical exploration.

But it is the profoundly anti-democratic nature of neoliberalism backed by the authoritarianism of the neoconservatives that should surely be the main focus of political struggle. The democratic deficit in nominally ‘democratic’ countries such as the US is now enormous.23 Political representation is there compromised and corrupted by money power, to say nothing of an all too easily manipulated and corrupted electoral system. Basic institutional arrangements are seriously biased. Senators from twenty-six states with less than 20 per cent of the population have more than half the votes to determine the Congressional legislative agenda. The blatant gerrymandering of congressional districts to advantage whoever is in power is, furthermore, deemed constitutional by a judicial system increasingly packed with political appointees of a neoconservative persuasion. Institutions with enormous power, like the Federal Reserve, are outside any democratic control whatsoever. Internationally the situation is even worse since there is no accountability, let alone democratic influence, over institutions such as the IMF, the WTO, and the World Bank, while NGOs can also operate without democratic input or oversight no matter how well-intentioned their actions. This is not to say that there is nothing unproblematic about democratic institutions. Neoliberal theoretical fears of the undue influence of special-interest groups on legislative processes are all too well illustrated by the corporate lobbyists and the revolving door between the state and corporations that ensure that the US Congress (as well as state legislatures in the US) does the bidding of moneyed interests and moneyed interests alone.

To bring back the demands for democratic governance and for economic, political, and cultural equality and justice is not to suggest a return to some golden age. The meanings in each instance have to be reinvented to deal with contemporary conditions and potentialities. Democracy in ancient Athens has little to do with the meanings we must invest that term with today in circumstances as diverse as São Paulo, Johannesburg, Shanghai, Manila, San Francisco, Leeds, Stockholm, and Lagos. But the stunning point here is that right across the globe, from China, Brazil, Argentina, Taiwan, and Korea to South Africa, Iran, India, and Egypt, in the struggling nations of eastern Europe as well as the heartlands of contemporary capitalism, there are groups and social movements in motion that are rallying to reforms expressive of some version of democratic values.24

US leaders have, with considerable domestic public support, projected upon the world the idea that American neoliberal values of freedom are universal and supreme, and that such values are to die for. The world is in a position to reject that imperialist gesture and refract back into the heartland of neoliberal and neoconservative capitalism a completely different set of values: those of an open democracy dedicated to the achievement of social equality coupled with economic, political, and cultural justice. Roosevelt’s arguments are one place to start. Within the US an alliance has to be built to regain popular control of the state apparatus and to thereby advance the deepening rather than the evisceration of democratic practices and values under the juggernaut of market power.

There is a far, far nobler prospect of freedom to be won than that which neoliberalism preaches. There is a far, far worthier system of governance to be constructed than that which neoconservatism allows.