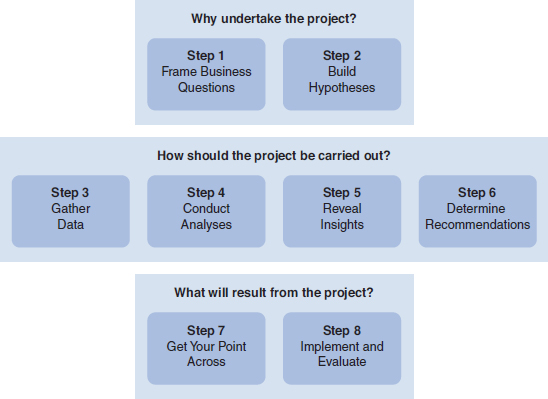

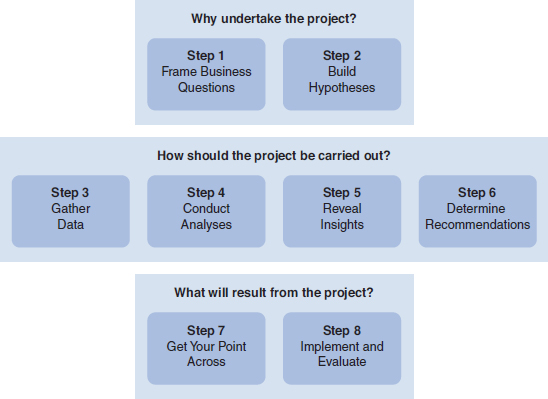

Figure 4.1 The Eight Step Model for Purposeful Analytics.1

“After a recent speech, an attendee came up to me and said, ‘I can predict attrition for my firm to 92 percent accuracy.’ I said, ‘Wow! That’s great. Is attrition a problem for your firm?’ And she said, ‘No, not really.’”

—Josh Bersin

Principal and Founder, Bersin by Deloitte

As this quote indicates, some people are undertaking analytics in the field of HR to solve irrelevant problems. This lack of a practical purpose is the result of a more fundamental issue: No standard methodology exists for undertaking workforce analytics projects to ensure that they deliver meaningful results. Another underlying issue is the lack of analytics project sponsors. For workforce analytics to impact the business, senior executives need to care about a project, what it reveals, and how it can change the business as a result.

This chapter aims to increase the robustness of workforce analytics projects by focusing on three key topics:

• A model for purposeful analytics

• The important role of the project sponsor

• Typical reasons analytics projects fail

Given the nascent state of the field, it is not surprising that workforce analytics has no standard methodology. However, it is also clear that many people struggle with achieving impact from their workforce analytics activity because they do not set about the project in a way that will lead to success. For these reasons, it is sensible, if not essential, for analytics practitioners to have a methodology for structuring analytics work. The methodology proposed here has eight steps that can be grouped into three parts, as Figure 4.1 shows. Chapter 6, “Case Studies,” illustrates this methodology through real examples that demonstrate how a clear approach can lead to organizational change and improved business performance.

Figure 4.1 The Eight Step Model for Purposeful Analytics.1

Unless you know why you are undertaking an analytics project, you will find it almost impossible to bring any meaningful value to the business. When it comes to workforce analytics, people often start with the data, but starting with the end in mind is a better approach. In other words, first define what you are trying to change and why. Alec Levenson, an economist and senior research scientist at the University of Southern California and the author of Strategic Analytics, states: “To complete an analytics project well takes time and energy. This means you need to be a systems thinker and consider all the links from the HR process to the business issues. For every project, there should be a business problem to solve.”

Framing the business question is another way of clarifying the business problem. This step must come first to avoid undertaking the wrong analysis and also to give the project the best chance of success. A clearly framed and well-defined business question ensures that the project or analytics work is actually necessary. Without such clarity, the project is unlikely to gain investment and sponsorship. Appropriately framing the business question provides unambiguous direction. Defining effective business questions involves several aspects:

• Focus on understanding the business. Christian Cormack, Head of HR Analytics at AstraZeneca, believes business understanding is the basis of framing questions: “You need to spend time with senior people understanding how the business works so that when the business requests something, you understand the context and can give a higher-quality answer. I’m lucky that there’s never a shortage of questions from our business.”

• Use appropriate consulting techniques. Questioning, listening, and paraphrasing skills help get to the heart of the problems. Issues such as internal business dynamics, external market forces, financial impact, and linkage to organizational values must be considered. Investigating these areas and using effective questioning techniques ensure that the business problem is properly understood and defined. Chapter 12, “Build the Analytics Team,” details the skills needed for this step.

• Summarize the business question back to the project sponsor. Be sure to get agreement on the business question your analytics project will address. Write down the question and ensure that the project sponsor signs off on it, to signal agreement that the project should begin.

• Be thorough. This step can be as simple as one conversation or it can be much more complex, with multiple conversations among several stakeholders to ensure clarity. Substantial resources (money, people, time) might be needed to deliver the project, so it is important to get clarity on the problem to be investigated. To proceed successfully, it is best not to move too quickly; although speed is important, diligence is critical.

Building and clarifying a hypothesis is important for “testing” beliefs about the causes of business issues. Strong hypotheses should guide the data gathering and analysis phases in a way that links to business questions. Formulating hypotheses in advance helps guard against reaching conclusions based on observed relationships in your data that result from chance instead of genuine underlying relationships. Appropriate hypotheses also make it easier to select the most appropriate analysis for the project in question.

These steps are key to writing a good hypothesis:

• Write a hypothesis as a statement, not as a question. Hypotheses are informed, testable explanations or predictions. The statement might look something like: If [we do this], then [this] will happen. For example, if people are leaving the company at a higher rate than expected, the hypothesis might be articulated as: If we increase salaries, then the turnover rate will reduce.

• Use relevant literature to inform the hypothesis. Industrial and organizational psychology and management scholars have studied many common people-related problems for years, and the industry has accumulated a wealth of knowledge on the causes and consequences of different problems. As you develop your hypotheses, make use of the latest scientific thinking in key academic journals in the field. Google Scholar is a good first port of call for a literature review.

• Discuss the hypothesis with the project sponsor. Share your hypothesis with the project sponsor to ensure that it accurately reflects the situation as the sponsor believes it to be.

• Ensure clarity. A good hypothesis is written in clear and simple language. Reading the hypothesis should clarify whether each possible analysis result will support or reject the hypothesis.

• Make sure the hypothesis is testable. A scientific approach tries to disprove hypotheses because a single refutation of a hypothesis shifts the attention to a different line of thinking. Analysts usually proceed when their hypotheses are not rejected. The number of times a hypothesis should be tested depends on, for example, the rigor of the research design, the quality of the data, and the magnitude of the work’s impact. However, keep in mind that numerous results supporting your hypotheses could be overturned by one additional test that disproves it.

• Don’t make the hypotheses too ambitious. Answering some business questions will likely involve more than one hypothesis. However, multiple hypotheses complicate the analysis, so be prepared to rationalize the number of hypotheses where possible to reduce complexity.

The choices you make here influence the validity of your project’s outcomes. This part of the methodology will likely be the most complex because of the deep technical knowledge and skills required.

The data gathering step requires identifying the most relevant data for testing the hypotheses and determining whether data quality is sufficient to proceed. Decisions need to be made about whether to gather existing data, collect new data, or do both. Note that this step can easily become unwieldy. Projects might begin with good, clear data intentions, but when analysts start data cleansing and then run some initial analyses, new and tempting areas of exploration could emerge. Reminding yourself of the business question you set out to answer and the related hypothesis you sought to test should help to avoid these distractions and ensure a better data focus. This step also includes managing any legal and ethical aspects concerning data privacy challenges; see Chapter 10, “Know Your Data,” for more details.

There are several tips for the data collection step of any project:

• Keep sight of your objective. Don’t get lost in data too quickly and, as a consequence, lose sight of your end goal. Naturally, many analysts are curious; this curiosity is an important element of succeeding in their role, but it can also distract from the desired focus of your project.

• Build a picture of your data before you gather it. Projects commonly progress too slowly. Resources are initially devoted to integrating existing data that people believe will permit hypothesis testing, but they find that the data are not as comprehensive as initially expected. To overcome this, take the time to map out data and undertake some checks before gathering it—for example, to ensure that it contains unique identifiers to link the datasets that you plan to analyze.

• Focus on data that you already have. This might sound straightforward, but many analytics practitioners complicate matters by thinking that they always need new data. Start with the data you have and evaluate its quality for testing your hypotheses before you collect new data.

• Think carefully about new data. Existing research (from inside or outside the organization) might help to answer at least part of the question driving your need for new data. If a new data set is required, think carefully about how to collect it. A small amount of new, high-quality data is better than a lot of semiuseful data. Also think comprehensively about data you might need in the future, to avoid having to repeat data collection.

• Remember existing scientific research. If existing data are poor and collecting new data is too difficult, you might be better off relying on research evidence in the scientific literature instead of collecting your own new data.

This step is what many people consider the real part of analytics. This is where the methodology and statistics are applied to data to test the hypotheses and provide the basis for insights. Without this step, the fundamental building blocks of any analytics project simply do not exist; without performing analysis, patterns in data will never be discovered. At this juncture, choosing the right method for analysis is critical because choosing the right—or wrong—method will determine the validity of the results.

Many different analytical methods and associated technologies can make analysis more focused and successful. Choosing the right technology and the right method for analysis requires at least a basic knowledge of what the various methods and technologies can deliver. To help with your selection see Chapter 5, “Basics of Data Analysis,” and Chapter 11, “Know Your Technology.”

One of the most frequent requests in workforce analytics is, “Bring me insights, not data.” Data are useful and analytical results are interesting, but understanding the context and implications of the results is what leads to insights. Workforce analysts must uncover insights for two main reasons. First, analysts cannot assume that project sponsors and stakeholders are able to derive the most pertinent insights themselves. Project sponsors might not be experts at this, so workforce analytics practitioners should make it one of their main tasks. The second reason is more subtle: If analysts present only data and analysis without insights, executives and project sponsors might draw their own conclusions to best fit their preconceptions. Bart Voorn, HR Analytics Leader at Ahold Delhaize, endorsed this: “We want to improve the quality of decision making by using insights. I prefer not to build dashboards or to create reports. We should focus on generating insights.”

Although this step has no magic formula, some helpful hints apply:

• Write insights clearly in single sentences. If you cannot write an insight clearly in a single sentence, ask yourself whether it really is an insight. Describing insights in single sentences is also helpful so that you can create effective visualizations and draw clear recommendations.

• Express each insight in one visualization, where possible. As part of the process of clarifying insights, try to express each insight in a visual format. Not all insights can be easily visualized, but whenever possible, visualization significantly aids effective communication. Chapter 17, “Communicate with Storytelling and Visualization,” discusses this in more detail.

• Avoid displaying raw data or analysis without interpretation. Leading practitioners recommend not using raw data as insights because this can be distracting and cumbersome. Similarly, avoid showing analytical output, such as lengthy tables of correlations and technical details. Instead, present the interpretation of the data.

• Ask yourself what each insight means. As you derive the insight, you should be able to articulate why it is important. Test the importance of the insight by asking questions such as the following:

• What does this insight tell me?

• Does this insight relate to the business question?

• Is this insight unique or just another twist on a familiar topic?

• Is the insight clear?

• What actions might result from this insight?

• Focus on revealing key insights. Leading practitioners in workforce analytics emphasize that staying focused on the most important insights is vital. You might generate a large number of insights that you feel compelled to share, but it’s better not to overwhelm your audiences with too much information. Refer back to the business question as a guide for where to focus the attention. Retaining this focus will contribute to the project’s success. Chapter 17 offers more guidance in this area.

Just as you need data for insights, you need insights for recommendations. Ask yourself the following: If my insight is important enough to highlight, then what should the business do about it? Analytics projects are all about helping the business improve its performance, so although insights are interesting, only recommendations will help improve the business. Recommendations are what business leaders and, in this case, project sponsors need. A well-articulated recommendation makes a great impetus for change.

Some analytics projects fail at this stage simply because recommendations are not expressed clearly. To ensure that recommendations are determined from insights, consider these tips:

• Provide one recommendation for each insight. Starting in this way focuses the analytics professional on clarifying why the insight is important and what the business will look like if something is done about it.

• Group individual recommendations into main themes. After all recommendations have been derived from insights, review them and draw out the main themes and major recommendations.

• Be bold. Analytics professionals have a unique perspective on the business question. Having considered empirical data and drawn insights, they are in a strong position to make recommendations. Go ahead and make those recommendations. Be bold.

• Write each recommendation clearly as a statement. Each recommendation should stand alone as a clear, simple statement. It should not need explanation. It might require discussion, but the recommendation itself should be very clear—for example: This insight shows … and, as such, I recommend ….

Successful analytics projects conclude with decisions. Those decisions might drive change in the organization or might reinforce the status quo—either way, a clear decision is made. Driving change, if necessary, requires effectively communicating the analytics findings and a clear process. Decision making, communication, and action should then prompt a period of evaluation for both the project itself and its associated outcomes.

All analytics projects have a moment of truth. This often happens as you communicate the outcomes of the project to the sponsor or other stakeholders, to get your point across. This is the moment when you are able to inform their decision making. Experienced practitioners and leaders know when they have been impactful and can tell whether their chosen method of communication has been effective. Ralf Buechsenschuss, Global HR Manager of People Analytics & Transformation at Nestlé, agrees: “Storytelling is the connection between the analyses, the data, and the senior leader. Analytics really adds value when you have that connection.”

We recommend the following approaches to get your point across:

• Translate insights into stories. Stories have to be inspired by insights and link, through visualizations, to recommendations. Figure 4.2 illustrates this.

Figure 4.2 Linkage of insights, visualizations, and recommendations to the story.

• Carefully consider your visualizations. Use interesting visualizations that capture attention. Before you add any visualizations, make sure that the message you expect from each one is clear. One tip is to write down the message you intend before you start creating the visualization. Don’t just copy and paste screenshots of data or statistical results, thinking that these will suffice. Terry Lashyn, Director of People Insights at ATB Financial, explains: “People look away from technical spreadsheets, so show the numbers in a way that others can understand. We tell a story using pictures rather than using columns and rows of data.”

• Start with a blank sheet of paper. Before you use any presentation software, such as Microsoft PowerPoint, sketch out your storyboard. You will get a better flow for your story and your presentation will no doubt be shorter: You are unlikely to sketch out 45 pages on paper, yet you’ve probably seen many presentations with that number of slides—or more!

The implementation and evaluation step has three discrete aims. First, it ensures that decisions are made as a result of your project. Second, it formulates actions for implementation based on those decisions. Finally, it facilitates evaluating the project against whether it returned value to the organization.

This is where the hard work really starts. As Ben Nicholas, Director of Global HR Data and Analytics at GlaxoSmithKline, articulates, “I’d describe the analytics function as welcome dinner party guests, but not someone the other guests want to bump into the next day.” In other words, they want to hear what you have to say, but they don’t necessarily want to have to do the hard work of using your analytical insights to change the business. Despite the risk of this perception, it is vital that analytics projects continue to their conclusion and return value back to the organization’s stakeholders (shareholders, workers, communities, and so on).

In this part of the project, several tips can help:

• Push for decisions. At this stage, sponsors and stakeholders need to accept (or reject) recommendations and agree on clear decisions. To help with this, ask the following questions as part of your communication and discussions: Do you agree with my recommendation? Do you agree something should be done about this recommendation? Perhaps you can take the discussion further by asking, What are the next steps for implementation? Who will be responsible for implementing the actions? Push for clarity to get real commitment.

• Engage a change management or implementation expert. Analytics projects can be small and can impact a few workers, or they can be extremely complex, extensive projects that impact thousands of workers in an organization. Depending on the scope of the recommendations, you or your sponsor might want to engage change management or implementation consultants to ensure that the results are delivered. This step might be unnecessary for something as straightforward as a one-off training course. However, if your recommendation is to implement, for example, a new technology to automate a process that affects every employee, you will undoubtedly need additional support.

• Work with your HR business partner (HRBP). Work closely with your HRBP, particularly as actions from your project are being implemented. Jonathon Frampton, Director of People Analytics at Baylor Scott & White Health articulates this: “Our impact is in empowering our HRBPs to act on the outcomes of the projects. We don’t measure ourselves on the number of reports we complete, but rather on the impact we have.”

• Evaluate your project at appropriate time points. Analyzing the effectiveness of the implemented recommendations by calculating a return on investment (ROI) is a key responsibility of every analytics professional. Consider the timing of the evaluation, taking into account both the short- and long-term impacts of the project. In addition to evaluating ROI, it is good practice to reflect on how well the project itself was delivered and identify what could enhance the success of future projects. Setting milestone dates for this reflection and evaluation during and at the end of the project will help determine the success of the entire project.

Alexis Fink, General Manager of Talent Intelligence & Analytics at Intel, supports these points: “Workforce analytics projects should be evaluated over both the short and long term. As an example, at a prior company, we built an executive assessment that was very difficult to pass. We developed coaching and learning programs based on analysis of the differences between successful and unsuccessful candidates and, in the space of a few years, we had more than doubled the pass rate.” Alexis indicated that, over time, they had measurably improved the overall quality of their leadership pipeline. However, the assessment was no longer differentiating. “By using analytical techniques, we could monitor results over time, short and long term, and identify when we needed to refresh the research. This ensured that the assessment delivered exactly in the way we wanted.”

For further discussion on evaluating the outcome of projects, see Chapter 14, “Establish an Operating Model.”

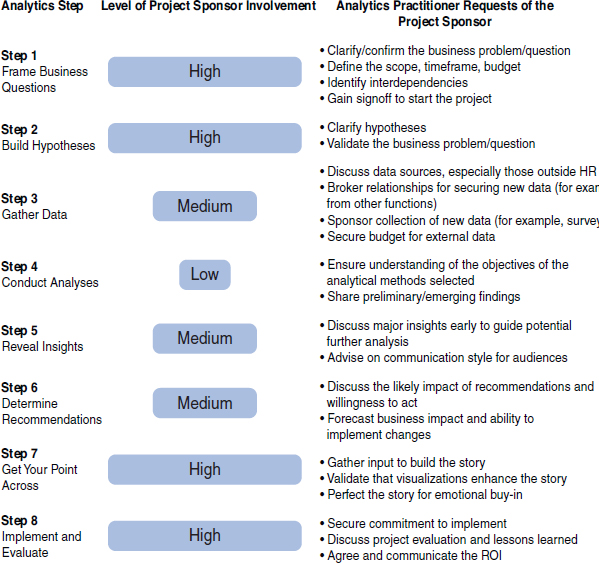

Throughout this chapter, you have seen project sponsors identified as a critical party. In this section, we discuss the relationship between the workforce analytics practitioner and the sponsor and explore why sponsorship is important for success. We also map the analytics practitioner’s requests of the project sponsor to each step in the purposeful analytics methodology.

Project sponsors are individuals who have an active interest in one or more specific workforce analytics project. They are usually responsible for approving the project, providing resources needed for project execution, advocating for the project, and working with stakeholders to ensure that actions are implemented. In short, the sponsor has a vested interest in the project from start to finish.

How do you know whether you have the right sponsor to help you deliver a successful analytics project? Strong sponsors are highly respected leaders in their organizations, with a deep understanding of the organization and the challenges it is facing. They are well connected and able to rally support, and are willing and able to secure the resources needed. Finally, the best sponsors are highly motivated and available to see the project through to completion and benefit realization. Damien Dellala, Head of People Data & Analytics Enablement at Westpac Group, emphasized the importance of a good sponsor: “Experience has taught me that, when starting a workforce analytics project, having an engaged sponsor is at the top of the list of success factors.”

When securing sponsorship, setting expectations on outcomes before undertaking an analytics project is important. This means thinking through the possible scenarios and posing them to the sponsor. For example, if the issue is high turnover among a certain group of employees, and the analysis reveals compensation is a strong contributing factor, is the sponsor willing to allocate budget to solve the problem? What if lack of career growth is a root cause—is the organization willing to design new career guidance and promote people at a more rapid pace than it has traditionally done? Thinking through these possible scenarios and building commitment and willingness to act increases the probability that the organization will actually implement the necessary actions.

Figure 4.3 summarizes the many actions required of the project sponsor to ensure analytics success.

Figure 4.3 Project sponsor involvement in workforce analytics.

In general, project sponsors need to prioritize project reviews and invest sufficient time. They also need to secure funding where needed, remove roadblocks, and leverage their relationships and status to help the analytics team succeed. Sponsors are expected to see the project through all the steps to completion and to be consistently available when needed. They must act as role models in embracing and acting on the analytics insights and recommendations, and they must hold others accountable for doing the same. Sponsors need to challenge the naysayers and be highly visible champions of workforce analytics.

Some people in organizations have power because it comes with the role—for example, the chief financial officer. This power is institutional power. Other people have power that comes from the relationships and influence they hold. This is relationship power.

Morten Kamp Andersen,2 an experienced consultant, puts workforce analytics leaders in the latter category. “They don’t have power because of the role; they create power because of the way they bring value through relationships.” He continues to identify their key skills in this role: “Workforce analytics leaders need to be able to sell their projects into the organization. They need to have strong business acumen, be good at storytelling, and be experts in stakeholder management. These are all relationship and communication skills.”

Without such relationship power, projects do not always run smoothly. Morten believes that a successful analytics leader in human resources builds relationship power and uses that with key stakeholders and sponsors: “Don’t build the project in the HR environment alone. If you leave your sponsorship too late, you will probably end up with no sponsorship. Create relationships with senior business leaders and make sure you get a non-HR sponsor for every project.” Wise words indeed!

Issues with a project sponsor are only one of the reasons analytics projects can falter. Being aware of all the potential pitfalls helps you take steps to avoid them and increase your chances of success. This section looks at reasons an individual analytics project might not succeed and examines the three parts of the model for purposeful analytics.

A project with no clear purpose is in high danger of failure. Some reasons for a lack of clarity at this stage follow:

• Lack of a project sponsor

• Poor communication with the project sponsor

• No clear purpose for the project or request

• Poorly defined reason for the project

Fundamentally, the best analysis in the world is of limited value unless you know why you are doing it and have clear project sponsorship.

Projects often fail because of poor execution and delivery. This can result from one or more of the following factors:

• Incomplete, inaccurate, or irrelevant data

• Poor choice of statistical technique or method

• Lack of investment in the right systems and technology

• Lack of technically competent people

• Poor extraction of insights and recommendations

• Not enough time to undertake the project properly

Even the most expertly defined business problem and well-crafted hypotheses will not yield benefit if the project is poorly executed and an inadequate investment is made.

Projects can fail when results are poorly communicated, no action results, or action occurs but with no evaluation to determine the business return. These factors can hinder success:

• Poor visualization with unclear insights

• Ineffective storytelling that loses the simplicity of the message or fails to articulate it

• No buy-in for the outcomes of the analytics project, with no accepted or implemented recommendations

• No clear plan or owner to implement the organizational change recommended by the project

• Lack of evaluation to determine the project’s impact

Even a good analysis that highlights well-founded recommendations to a known business problem can fail if it is poorly understood. And if nothing happens as a result of the analytics, the entire project was not worth undertaking anyway. As Terry Lashyn explains, “You need to believe that when you undertake analytics, you are going to change something.”

Discovering, interpreting and communicating meaningful patterns in workforce-related data demands a robust methodology. Whether for a short project of a few weeks or a longer one that spans many months, methods need to be straightforward and complete. Successful workforce analytics projects follow these main methodology recommendations:

• Consistently apply all eight steps of the purposeful analytics model to your analytics projects.

• Start projects by defining the business question and building strong hypotheses.

• Use the most appropriate technology and methods for your analyses to ensure robust results.

• Get the point of your analytics projects across to your sponsors and stakeholders through clear visualization and storytelling.

• Help your business translate project recommendations and decisions into action and evaluate the results.

• Choose your sponsors wisely, with an eye toward strong, consistent support throughout the entire lifecycle of your projects, from request to implementation.

• Familiarize yourself with the common reasons analytics projects fail, and throughout the eight steps, ensure that potential problems are avoided or addressed.

1 The Eight Step Model for Purposeful Analytics is a copyright of the authors of this book: Nigel Guenole, Jonathan Ferrar and Sheri Feinzig.

2 Morten Kamp Andersen is a partner and analytics expert at proacteur, a consulting firm based in Copenhagen, Denmark. It is an agile consultancy company that focuses on change management, manager development, project and program management, and process-driven support for IT implementation (www.proacteur.com).