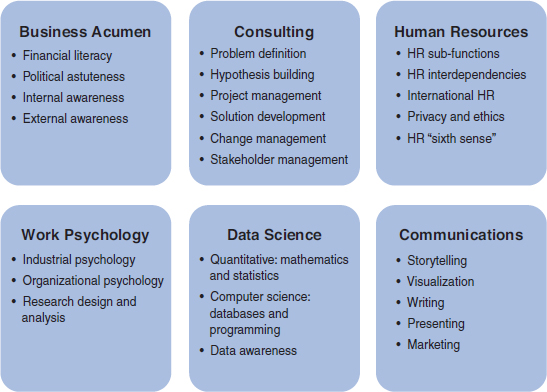

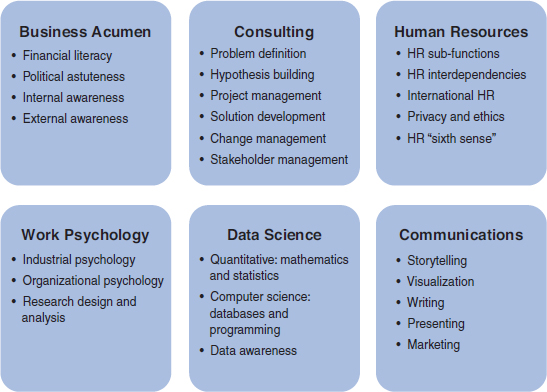

Figure 12.1 The Six Skills for Success.

“There are new skills that are fundamental. You must see the world from the outside in, use storytelling, be numerate, and have a consulting mind-set. The world of Human Resources is changing.”

—John Boudreau

Professor of Management and Organization, and Research Director of the Center for Effective Organizations, University of Southern California

The human resources (HR) profession is undergoing a transition that will shift HR’s approach from primarily intuition based to primarily evidence based. To make this transition, HR professionals need new skills.

These developments have partly spilled over from the benefits that analytical approaches have delivered in other areas, such as finance and marketing. The best way for HR to realize these same benefits is to develop a properly skilled workforce analytics function or team.

This chapter covers the following topics:

• Leveraging the Six Skills for Success in workforce analytics

• Configuring team roles based on anticipated workload

• Hiring versus developing the workforce analytics team

• Remembering the fundamentals of personnel selection

Figure 12.1 illustrates the Six Skills for Success1 in workforce analytics, a comprehensive and simple guide to help HR leaders earn credibility and achieve success.

Figure 12.1 The Six Skills for Success.

“There are so many different skill sets needed, from data infrastructure through to reading literature, forming hypotheses, collecting data, doing the analysis, and implementing recommendations.”

—Mark Huselid

Distinguished Professor of Workforce Analytics, Northeastern University

Business acumen refers to a keen and agile ability to understand, interpret, and deal with business situations. It requires gaining expertise across multiple disciplines, integrating lessons learned from diverse experiences, and then applying that knowledge to make decisions that lead to better organizational outcomes.

Business acumen is one of the Six Skills for Success because it ensures that you understand the finances that drive your business and that you are politically astute enough to complete projects in the face of complex internal and external operating environments. Without business acumen, analytics professionals might not fully tune their analytics projects to the specific business problem being analyzed.

Business acumen involves the following components:

• Financial literacy. Financial literacy involves an understanding of key accounting concepts such as profit, revenue, and sales, and an awareness of the factors that impact important business metrics, such as seasonal business cycles. It also includes the ability to read financial statements and an awareness of the commercial operating environment. Financial literacy is important in workforce analytics to give you credibility with other business leaders, to help you build investment cases for analytics projects, and to provide insight into how to align analytics with the important metrics in your business. Although formal classes can help you learn accountancy skills, much of this knowledge is acquired through what you do at work, such as getting involved in projects with financially literate people and working on tasks that require financial understanding.

• Political astuteness. Political astuteness means being able to understand organizational relationships, influence others, and resist influence as required. It also means being adept at navigating both the organization’s formal decision making and its often important informal structures. Political astuteness is critical in workforce analytics because the success of your work not only depends on its quality, but also how it is perceived in the organization. Gerald Ferris, a professor at Florida State University and an expert on politics at work, shows in his book Politics in Organizations (Routledge 2012), co-authored with Darren Treadway, that the willingness and ability to successfully navigate political relationships depend on your perceptions of the political environment and your ability to control politics. Political astuteness requires abilities such as emotional intelligence, self-awareness, and general courtesy. However, the most important skill is to be able to identify which of your many relationships and conversations are critical to success so that you can rigorously prioritize work activities. The best way to develop political astuteness is to work closely with people who seem to get things done despite challenges they face in the organization and then learn how they do it.

• Internal awareness. Whereas political astuteness refers to an ability to understand relationships and use this understanding to influence others, internal awareness refers to an understanding of your organization’s work environment. This means understanding the macro perspective on what your organization is there to do, as well as how your team’s work contributes to this overall objective. Even projects with substantial promise for cost savings or revenue generation might face obstacles if they conflict with or are not aligned with other organizational initiatives. You can develop internal awareness in many ways. For example, you can build relationships with people in your organization from a broad range of backgrounds and with diverse responsibilities. You can also monitor both media coverage of your organization and internal communications. The best way is likely to be a blend of multiple approaches.

In analytics, business acumen and the ability to define the business problem are key. “When we get a request, we think through what the problem really is, what’s driving the request, and then we figure out which skills on our team will best answer that question.” This is the philosophy of Rebecca White, Senior Manager of People Analytics at LinkedIn.2

Rebecca explains that building a team with complementary skills is important. “We have diversity of skills, and it serves us well,” she says. “I come from a consulting background, we have a couple of people with a traditional industrial–organizational psychology background, some people are more data science and analytics focused, and some have data visualization skills.”

When Rebecca and her colleagues seek to drive change, they draw on this breadth of skills to expertly channel the analytics projects in the right direction. “This range of skills has really helped our team to achieve success. Because we have so many skills on the team, it gives us flexibility to answer the business questions.”

She continues: “We focus every project on the real business need and what the impact will be. You can go very far in analytics down a rabbit hole, so we figure out how to collaborate across the team, using the right skills at the right time, to drive impact instead of giving executives a bunch of data for their back pockets.”

That philosophy and approach have served her well.

• External awareness. Having external awareness means taking account of external environments when running the workforce analytics function. This requires awareness of factors such as economic conditions, industry sustainability, competitors, and supply and demand. External awareness is important in workforce analytics to enable you to forecast the effects of decisions you make. You can learn much from the past, but given the rapid pace of change in most industries, you need to be aware of the past without being overly constrained by it. A strong external awareness means knowing the historical context of your market and having an informed perspective on the likely future conditions in which your business will need to operate. You can acquire external awareness about your industry by reading business news and industry magazines and by networking with leaders in your field.

Consulting skills include the ability to provide specialist expertise to organizations to improve some aspect of their business. Core components of consulting skills in the context of workforce analytics include the ability to define business problems, generate hypotheses about the causes of business problems, manage projects, develop solutions, manage stakeholders, and manage change.

• Problem definition. Problem definition refers to accurately understanding the nature of a problem. Doing this well requires skills with language, such as listening, questioning, and paraphrasing, as well as the ability to exercise good judgment. These skills are required in the first step of the analytics model that Chapter 4, “Purposeful Analytics,” outlines. Problem definition is an essential skill for workforce analytics success because it allows you to not only clarify the business problems, but also identify the most important ones. A good way to acquire skills in defining problems is to consider case study materials about business problems (for example, in business journals such as Harvard Business Review). You can aim to apply the same approaches and thinking to your own situations.

• Hypothesis building. Hypothesis building involves identifying plausible causes of the problems you have defined and, more important, generating potential courses of action that might solve the problem. Being able to articulate a hypothesis about the causes of the business problem allows analysts to determine whether the hypothesis itself is plausible. Hypothesis building also involves identifying the different data sources that allow you to test hypotheses. Hypothesis building is important in workforce analytics because hypotheses that focus on the causes of business problems and have data to support them represent potential intervention points to affect change in the organization. Some people have good intuition on formulating hypotheses. The most skilled people have received formal training in a discipline that prioritizes logic and rationality, such as economics or work psychology.

“When you are clarifying and building hypotheses, I have come to realize that one of the most useful skills is to have what you could call a beginner’s mind-set so that you can tackle every problem in an open-minded way.”

—Salvador Malo

Head of Global Workforce Analytics, Ericsson

• Project management. Project management skills enable the workforce analytics team to hold people accountable for what they agree to deliver: They agree on what is feasible, develop plans, list dependencies, identify risks, allocate owners, and monitor milestone achievement. Project management skills are required in workforce analytics to integrate and align numerous different streams and types of work. Such skills help ensure that projects are delivered to specification and on time. These skills are often acquired through project management training courses, some of which include an exam to ensure that participants understand the key concepts. If you work in an organization with a strong project management approach, you may be able to acquire these skills in the course of your work.

• Solution development. In addition to being able to identify the problem, successful management consultants can structure possible solutions to the problem. They generally propose multiple solutions and examine the feasibility of successful implementation of different solutions under various conditions before they determine the most plausible and effective solution. These experts, often known as organizational development specialists, tend to focus on solutions to problems that address changing the mind-sets of workers and/or the environment in which they work. Many people learn skills for solution development on the job, but often experts have some formal training in the field of organizational development. Alternatively, to acquire solution development skills without studying, you might consider taking a role in a consultancy that focuses on organizational development. This can give you experience in proposing solutions to business problems and evaluating their likely effectiveness.

• Change management. These skills involve understanding the stages workers go through as they experience change and, most important, helping workers understand the reasons for change and become comfortable in the new world. Essential skills involve communicating, educating, influencing, and managing people affected by change. This is important because analytics ultimately need to drive change. Terry Lashyn, Director of People Intelligence at ATB, captures this point: “If your insights or recommendations do not confirm or drive new strategies or change something in your business, then you have failed.” Implementing follow-up actions suggested by analyses provides the greatest source of possible value. For successful follow-up interventions, workers must be persuaded of the benefits that the new ways of working will deliver.

• Stakeholder management. Workforce analytics involves linking information about people to outcomes in nearly all areas of the business. This means you will come into contact with a diverse range of stakeholders who have different interests and perspectives (Chapter 8, “Engage with Stakeholders,” discusses this further). Identifying who these stakeholders are, understanding their perspectives, and managing their expectations are critical tasks. Because many workforce analytics teams are small, one potential strategy is to align the interests of as many stakeholders as possible and address the common needs of stakeholders simultaneously instead of trying to manage different needs on a stakeholder-by-stakeholder basis. Recognize the different types of stakeholders and take a systematic approach to managing your relationships with each.

Workforce analytics is about executing strategy through people, so you want to have human resources (HR) skills on your team to successfully implement analytics projects. This is because interventions in workforce analytics often require changes to HR policies and practices. The key areas are HR subfunction skills, HR interdependencies, international HR, and an HR “sixth sense”:

• HR subfunctions. These skills refer to knowledge of the HR subfunctions, including compensation, recruitment, and learning. Practices within HR subfunctions are often highly specialized. Specialist awareness in each area is important to ensure that your interventions take into account best practices and any company-specific policies. You might also need legal expertise. If a team member wants to develop skills in this area, some formal qualification will likely be needed. Work-shadowing an expert while undertaking a project can also help team members learn about HR subfunctions.

• HR interdependencies. This refers to knowledge of how the different functions in HR relate to one another—specifically, how changes in one function interact with others to impact the effectiveness of other functions and the workplace overall. This is important so that analytics projects are discussed alongside the impact they might have on other areas of HR and the business.

• International HR. If any of your workforce analytics projects span multiple countries, you might need people with a knowledge of the international HR environment on your team. International HR experts know the legal landscape and whether policies are likely to need tailoring for different operating environments. For projects with implications in numerous countries, it is wise to involve HR experts from the countries your projects affect. Alternatively, you might consider contracting with an HR consultancy firm that specializes in international HR or industrial relations.

• Privacy and ethics. The use of and interpretation of workforce-related data require sensitivity and, in some cases, legal involvement. Although building effective relationships with the chief privacy officer or other legal experts in your organization is important (see Chapter 8), having team members with knowledge of privacy regulations and ethics is helpful. Examples of particular relevance here are projects that involve several countries, the potential use of sensitive personal information, and algorithms from machine learning that might not be sensitive to the ethical values of your organization (see Chapter 5, “Basics of Data Analysis”).

• HR “sixth sense.” Someone who has a sixth sense for HR has strong HR knowledge, experience, and judgment. This skill involves an approach to thinking about HR issues that identifies important variables for analyses and follow-up actions. Not surprisingly, experienced HR professionals often naturally adopt such an approach. Such experience is also useful in ensuring that the team avoids pitfalls such as using data inappropriately or unethically. Because a sixth sense for HR usually comes from years of experience as an HR professional, the best way to bring this skill into a project is to make sure someone with HR expertise is involved in analytics from the outset. Christian Cormack, Head of HR Analytics at AstraZeneca, emphasizes this: “Our CEO wanted details of all the recently recruited senior leaders. A list had been extracted from our HR system and was about to be sent before someone asked me to double-check it. I knew instinctively that the list was too long, so I took a closer look. The list also included people who had recently moved from one country to another on assignment. Sometimes as an HR leader you have a sixth sense, which is important to use in analytics. The first test is always the common sense test: Does this look right?”

Dawn Klinghoffer is the General Manager of HR Business Insights at Microsoft.3 She has worked in analytics for much of her career and has a unique perspective about one particular skill on her team: “About 8 years ago, I made a case for having the employee data privacy manager on my team. She is a lawyer by background and understands the business very well.”

Dawn believes this skill is important for ensuring that the fundamental building blocks of the analytics function are based on the right principles and ethics:“I want someone on the team who understands what we really do with data and who can advise us on using them in the correct ways. This is not a one-off project, but on-going advice to ensure our projects are always undertaken respectfully.”

Dawn explains that although the privacy expert works closely with the legal department as needed, often her role is to advise the analytics team on ethical (instead of legal) matters. In a recent analytics project, for example, Dawn describes how the data privacy expert was intimately involved throughout to advise on the correct use of the data. “We needed advice throughout the project, clear guidelines on how to use the data, how it is stored, how it is contained, what elements were allowable in the algorithms, and how to ensure that the outcomes were used appropriately.

“It helps to have this person on my team to know exactly where our guard rails are.”

The Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology (SIOP)4 defines I-O psychology as “the strategic decision science behind human resources” and identifies I-O psychologists as “versatile behavioral scientists specializing in human behavior in the workplace.” The skills of I-O psychologists can be broadly grouped into industrial psychology skills and organizational psychology skills, which SIOP describes as follows:

• Industrial psychology. Industrial psychology is generally concerned with maximizing individual potential and related topics, including psychometric testing, selection and promotion, training and development, employee attitudes and motivation, and reduction of burnout, conflict, and stress. Industrial psychology skills in these areas are important so that you do not spend a lot of time trying to solve problems that scientists have already explored in depth (for example, identifying the best predictors of performance or attrition). Industrial psychology skills are best acquired through formal postgraduate study.

• Organizational psychology. Organizational psychology is generally concerned with maximizing organizational potential. It includes topics such as change management, strategic planning, surveys, job design and evaluation, organizational restructuring and workforce planning, and cross-cultural understanding. Organizational psychology skills are important for similar reasons as industrial psychology skills—that is, organizational psychologists already know a lot about the determinants of important outcomes such as work engagement. Study the existing literature first before starting your own investigations. Formal post-graduate study is the best way to acquire organizational psychology skills.

• Research design and analysis. In addition to having content expertise in the areas of industrial and organizational psychology, work psychologists often have technical experience in both designing studies to test hypotheses and running analyses to reach conclusions. These skills include experimental designs (for example, formal experiments) that allow you to infer causal relationships between variables, and designs that allow you to draw reasonably strong conclusions about causal relationships even when you cannot run an actual experiment (see Chapter 5). These skills are best learned formally rather than on the job. However, you can take data analysis courses to learn these skills; a number of prestigious universities often offer them for free.

Data scientists play a pivotal role in decisions regarding the causes of and likely solutions to problems in the realm of workforce analytics. Data science skills are often very specialized, and your team will benefit from including members who possess three broad types of skills:

• Quantitative skills (mathematics and statistics). Quantitative skills in workforce analytics refer to an ability to build statistical models. These types of analyses often involve methods known as traditional statistical modeling, which aims to understand causal relationships. On the other hand, quantitative analysis sometimes focuses exclusively on prediction without regard for causation, using machine learning methods that maximize prediction accuracy. Without strong quantitative skills, you risk applying the wrong methods and reaching unfounded conclusions. These skills are best learned through formal study, either in a classroom or via the increasing number of online courses available.

• Computer science (databases and programming). Computer science skills are necessary to interrogate databases and data storage systems and to integrate data from different sources in an auditable way. This skill is important because it allows computer scientists to think through problems in a logical way with associated implications for how different datasets relate to one another. When datasets become very large and cannot be managed with spreadsheets and personal computers, computer scientists use techniques such as parallelization, which distributes computing tasks across multiple computers and often involves cloud technology. To find out more about the requirements for this skill area in your team, speak with the people responsible for maintaining your HRIS and related technology. Computer science can involve high levels of specialization, so you need to know the precise technology used and the types of programming languages most suitable for workforce analytics in your organization. Then you can hire people with either the precise computer science skills you require or strong formal qualifications in computer science and a willingness to learn new technology and programing languages.

• Data awareness. The rate at which data are being produced and captured is increasing rapidly. A special skill set required for workforce analytics is to ascertain what new forms of data are becoming available and, more important, to assess their relevance to workforce analytics. One example is social media data. Some forms of social media have relevance to the workplace (for example, LinkedIn profiles), whereas the relevance of others is less clear. Knowing what these new forms of data are, how they can be captured, and their likely utility for workforce analytics is an important skill.

As your team begins to build momentum, your team members will need to develop or gain access to communication skills. These skills are critical to effectively create and tailor messages, and they involve the following key areas:

• Storytelling. Storytelling is a method of explaining a series of events through narrative. Telling an effective story to capture the essence of the problem, analysis, insights, recommendations, and change helps you gain buy-in for your ideas and projects. As analytics have become more important in the business environment, so have the skills required to explain data and insights using a compelling narrative. Chapter 17, “Communicate with Storytelling and Visualization,” covers this topic.

• Visualization. Skills in data visualization include the use of technology, graphics, and artistry to clearly show insights. These skills often require a combination of artistic creativity and technical ability with visualization methods and tools. These skills are relatively new in the world of workforce analytics; Chapter 17 discusses this topic, and Cole Nussbaumer Knaflic’s book Storytelling with Data (Wiley, 2015) is a comprehensive resource.

• Presenting. Creating and communicating your story through a structured presentation is an important and much-needed skill. The presentation might be informal and one-to-one, or it might be formal with many people in attendance. It might be in person, or it might be delivered remotely. Being able to adjust your presentation to the medium and audience is a critical skill if you are to communicate your ideas in a compelling way. For example, a slide deck should not be distributed without an accompanying explanation. Presentation skills can be acquired though experience and often via internal corporate training programs. All analytics professionals should receive formal training in presentation skills and basic presentation software such as Microsoft PowerPoint.

• Written communication. Clearly articulating written messages is essential in workforce analytics. This is because you are often dealing with complex ideas, diverse audiences, and different communication media (for example, email versus extended documents). Succinct written expression of ideas contributes to a clarity of understanding between your team and others. For highly important documents, you might choose to use writing and media specialists to improve the clarity of your messages.

• Marketing. Marketing is about communications that persuade an audience that an organization’s brand, products, or services have value. As you seek to persuade others of the benefits of your analytics team’s work, either internally or externally, you will want to market your team well. This includes managing your team’s brand and its reputation. Effective marketing often requires the services of a marketing professional, whether within your organization or from an outside specialist.

Ian Bailie leads Global Talent Acquisition and People Planning Operations at Cisco.5 It’s an important role that requires him to think differently. He views recruitment as one of the most measurable parts of HR. “Recruitment is a measurable process, basically a supply chain; you can measure every step of the process, and that provides good data.”

Ian uses the data to take a quantitative approach. He complements that with his experience in the business to create a strong connection with business executives. “During my nine years at Cisco, I have run analytics teams and been an operations manager in recruitment,” he says. “That enables me to really understand what the company is trying to achieve and what recruiters are trying to do. I think about the data, get to understand it, and use it to drive change.”

In his role, Ian has expanded his core mission to use analytics to look at the external world and undertake market mapping for talent. He started with the recruitment process and used his internal data to quantify the “talent supply chain.” He then introduced external market data (including LinkedIn data) into his analyses. The result was a business-critical market-mapping insight tool that the entire organization can use to understand talent. Essentially, Ian has used new levels of analytics to tell stories about where the best people are in the world and how to hire them.

The number of people you need on your team and how their skills should be organized into specific roles depends on the amount of work your team has and how long you have to complete the work. This, in turn, depends on the scope of your analytics function. Answering the following questions helps you structure the required skills into roles and determine how many and what types of workers you need (whether on your team or available to your team).

Before you can accurately estimate the number of workers you need on your team, carefully consider what you will commit to delivering in the foreseeable future. Planning and budget periods are typically annual processes, so a 12-month window is a good time horizon to use. In deciding what projects you will work on, be sure to revisit the list of project opportunities (see Chapter 7, “Set Your Direction”) in light of your function’s vision and mission. How many of these opportunities do you need to deliver so that you are seen to be meeting your mission? For example, you might have three major new projects to be delivered in the coming months, along with day-to-day requirements related to any ongoing projects from the previous year.

A common approach for large firms is to have workforce analytics teams with just a handful of workers. However, this tends to be for workforce analytics functions that keep reporting separate from analytics. Even then, workforce analytics functions could well have dozens of team members. In some cases, organizations of more than 100,000 employees have workforce analytics teams of more than 50 people. Therefore, the best recommendation is to match the size of the team with the scale of the work you need to deliver.

A general rule of thumb is that an organization of 100,000 employees with an approximate ratio of 1:100 HR practitioners to employees will have a team of roughly 1,000 HR people (the Bloomberg BNA HR Department Benchmarks recommends this ratio). In an HR team of this size, it is not uncommon to see a ratio of 1 workforce analytics practitioner to every 100 HR professionals. In fact we found organizations that had a ratio of almost 1:50, such that in organizations of 300,000 employees, there were approximately 60 workforce analytics practitioners (excluding reporting). This ratio is a guide, however we do see and predict a trend toward larger teams. The exact number varies depending on whether the organization is public, private, or voluntary, and also depends on its geographical breadth, industry complexity and the scale of workforce issues you encounter.

With a list of projects in mind, you can estimate the number of people who have some combination of the Six Skills for Success that you need to deliver the projects. As an illustration, a complex project that involves integrating datasets held by both internal departments and external vendors might require a full-time project manager and data scientist. On the other hand, a less complex project with easily accessible data in a central data management system might only need a shared project manager and a shared data scientist, both working across several projects.

Now that you know what projects you are likely to deliver and the skills you need to access if you are to successfully complete the projects, you should conduct a gap analysis. This involves determining the resources you currently have and then comparing those resources to what you discovered you need from the previous two questions. Resources you currently have should include your own personal skills, as well as the skills of any existing team members who will be working with you in the coming year. The difference between what you need and what you have represents the number of people and combination of skills that you need to acquire, whether from within or outside your organization, and whether on a temporary or permanent basis. Of course, you also need to build the business case for acquiring these skills (Chapter 14, “Establish an Operating Model,” covers this).

Hiring workers for your team signals commitment from the business that your work is important. Whether you get people who already have the skills you need or you hire people who can develop them depends on several factors. Hiring a person who has the skills you need now is certainly preferable to hiring someone you hope will develop the skills. First, having more qualified people helps you accelerate the rate at which you can achieve desired results. Second, your team will have enough challenges to focus on without adding concern about whether members need to develop additional skills to complete projects. However, hiring qualified people might not always be possible, and the workforce analytics function itself also needs to develop the ability to grow talent.

“I have an economics background and I was a management consultant in the former Soviet Union with EY. I left to run a water business and then came to workforce analytics. It was a great learning platform. You don’t necessarily follow a linear track. There's not a formal education track needed to be effective in workforce analytics.”

—Al Adamsen

Founder and Executive Director, Talent Strategy Institute

Tom Davenport, a professor at Babson College, wrote about the internal versus external hiring point in the online article “What Data Scientist Shortage? Get Serious and Get Talent.” He states: “I am convinced that many companies—particularly those that already employ a lot of technical people—could retrain substantial numbers of people to become data scientists. In some instances, it may be possible for workers in a closely related field to make a successful transition to workforce analytics, particularly if there is strong support for retraining.” An example might be moving from a data science role in marketing to taking on a similar role in workforce analytics.

Davenport points to Cisco as an example of a firm that developed a distance-learning retraining program for staff. Learning how to develop workforce analytics skills is also an important capability that can help establish an analytics culture in your organization. However, if timely delivery of projects is a concern and you have the choice between experienced and inexperienced potential workers, hire people who have formally trained in the skill sets you require and who can do the job from the outset.

At a minimum, your function needs to have a team leader. (Chapter 3, “The Workforce Analytics Leader,” covers this position in detail.) The next most important role to fill is someone with a deep understanding of the systems that store your HR data. This usually means a data scientist that has computer science skills for programming and database management. In addition, your team should include someone with enough HR expertise to be able to translate workforce analytics projects into the business environment. Beyond these requirements, you have enormous flexibility in how you configure the team. You can have the skills permanently on your team (in-house), elsewhere in the organization (in-source), or supplied through vendor relationships (outsource). We discuss these three approaches in Chapter 13, “Partner for Skills.”

So far, we have discussed the technical skills a workforce analytics function requires. Also be sure to remember the fundamentals of personnel selection that we know from I-O psychology. The basic building blocks of successful performance are cognitive ability, personality, and work interests. Cognitive ability and related concepts, such as intelligence quotient (IQ), predict task performance (or the quality and quantity of work) across nearly all occupations, and cognitive ability becomes more important as job complexity increases. Workforce analytics is recognized as a complex discipline, so we advocate cognitive ability testing for all roles within workforce analytics.

Personality tends to predict how people go about their work. Industrial psychologists stress desirable factors such as an ability and willingness to perform tasks that are not officially documented in job descriptions but are required for effective organizational functioning. This includes continuing to work hard when under pressure or stressed. The two personality factors most relevant here are conscientiousness and emotional stability. Each can be well assessed using standardized psychometric questionnaires.

Finally, whether a worker’s career interests are aligned with the skills required for the role predicts whether the workers will stay in their role. Candidates should express an interest in technical work, particularly for team members in highly specialized roles. However, when it comes to the leader of the workforce analytics function, assess the candidate’s interest in being a general manager instead of his or her willingness to get involved in highly technical work.

Building the analytics team or function is a critical task in the early phases of workforce analytics because the capability of your team is an important determinant of your success. This can seem like a challenging task, but taking a structured approach and following the principles outlined in this chapter sets you on the path to success. Be sure to cover these tasks:

• Ensure that you understand and have access to the Six Skills for Success, whether they are on your team or are easily accessible elsewhere. Configure the skills in your team and its size based on the expected workload and nature of projects.

• When deciding whether to hire new staff or develop existing staff, be aware of the pros and cons of each approach, such as whether skills developed in another area transfer to a workforce analytics context.

• Remember the fundamentals of personnel selection. Cognitive ability and certain personality traits, particularly conscientiousness, are important in all roles and can be tested with standardized psychometric testing.

1 The Six Skills for Success is a copyright of the authors of this book: Nigel Guenole, Jonathan Ferrar, and Sheri Feinzig.

2 LinkedIn is a business-oriented social networking service. Founded in December 2002 and launched in May 2003, it reported 433 million users in more than 200 countries and territories worldwide as of May 2016 (www.linkedin.com/about-us).

3 Microsoft, founded in 1975, is one of the world’s largest technology companies and most recognized brands. Based in Redmond, Washington, it employs more than 114,000 workers (www.microsoft.com).

4 The Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology is the world’s leading professional association for industrial and organizational psychology practitioners.

5 Cisco, founded in 1984, is an American multinational technology company headquartered in San Jose, California, that designs, manufactures, and sells networking equipment. At the end of 2015, it had annual revenues of $49.2 billion and more than 71,000 employees globally (www.cisco.com).