Figure 14.1 The workforce analytics operating model.

“We are being very proactive in defining the operating model and who catches what—which person to go to for which types of questions.”

—Rebecca White

Talent Analytics Senior Manager, LinkedIn

The goal of workforce analytics is to inform decision making and improve business performance. To fully realize this objective, the organization must embrace the workforce analytics function and integrate it into its strategy and operations. In this chapter, we outline an operating model that will set you on the path to this desired state.

The intent of this guidance is to create efficiencies that help you maximize the time you spend conducting analyses, communicating insights, developing recommendations, and implementing and assessing actions that solve your business challenges. Instead of reacting in an ad hoc manner to issues and challenges, your operating model should allow you to focus on high-priority work with minimal unnecessary diversions.

This chapter discusses the following:

• The components of a workforce analytics operating model

• Ways to link your operations to your strategy

• Governance to guide your operations

• Clarity and operational discipline for your team and projects

• How to hold yourself accountable

An operating model describes how a group will conduct its business within the larger organization and external environment in which it resides. Operating models are useful for identifying important working relationships, helping resolve issues and conflicts, and guiding decision making. When designed carefully and thoughtfully, an operating model helps you achieve your workforce analytics mission by aligning daily execution with what you ultimately set out to achieve. Figure 14.1 illustrates the recommended workforce analytics operating model elements.

Figure 14.1 The workforce analytics operating model.

As you can see at the top of Figure 14.1, an operating model keeps your day-to-day operations consistent with your workforce analytics strategy, as defined by your vision and mission. A governance framework helps you balance the needs of various stakeholders, from specifying the proper handling of data, to operating within the designated reporting structure, to defining decision-making procedures. Within that framework, you need to structure the implementation of your ongoing work through team structure, clarity of roles and responsibilities, and a disciplined approach to project management. And as with any business investment, accountability for results is required, through articulating a business case and tracking metrics that demonstrate your impact relative to those investments.

To ensure ongoing relevance, it is important that the workforce analytics team’s work aligns with and supports the organization’s overall strategy. As business conditions change and the organization adapts, the workforce analytics team’s focus should similarly evolve to meet new challenges and requirements. Periodically verifying your team’s vision and mission will help maintain the alignment needed.

As you read in Chapter 7, “Set Your Direction,” validating your vision and mission early on is important. As you gain experience, business priorities shift, and you demonstrate what is possible, your vision and mission should continue to reflect these dynamics. Re-engage stakeholders and project sponsors with a renewed perspective of what your team can accomplish. Reformulate your team’s desired future (your revised vision statement) and perhaps articulate a bolder statement of what your team can accomplish and how (your revised mission statement). Validate these revised statements of purpose with your key stakeholders and project sponsors, and communicate methodically to reach all necessary audiences.

As you revisit your vision and mission, ensure that they reflect the right guiding policies to overcome the challenges you strive to address with workforce analytics.

Governance provides a framework for how a group operates within its larger organization and environment. It is extremely useful for clarifying rules of engagement when working with workforce data, as well as specifying effective reporting relationships and guiding decision making.

Working with HR data requires special care because of the often personal and sensitive nature of the information. HR datasets generally contain personal information about employees. This is referred to in the United States as sensitive personal information (SPI) and in the United Kingdom as sensitive personal data; other countries have similar designations. This is information that, if compromised or disclosed, could result in such damaging situations and legislative violations as identity theft, discrimination, or unwanted negative publicity. Proper data handling procedures must be established for the long-term operations of the workforce analytics function.

Working with organizational data requires a clear understanding of and adherence to all relevant data legislation, regulations, and guidelines. Some policies come from the organization itself, and the team must also follow country-specificlegislation and regulations. Additionally, requirements exist for transferring data between nations. For example, the Privacy Shield Frameworks1 were developed to help U.S. companies transfer personal data from European Union countries and Switzerland. When working with people data in organizations, the sensitivity is further heightened. Extraordinary care must be taken to respect and adhere to all requirements regarding data collection, storage, access, and use. Organizations often have functions such as corporate information councils and roles such as the chief privacy officer that are charged with overseeing data-related matters. The workforce analytics team should work with such functions and people to ensure appropriate use of the organization’s workforce data and avoid any misuse.

“There’s a risk of discrimination if the domain knowledge is not there. For example, a statistical model could detect something about people who take six to nine months off and then return to work. HR people would know this was probably due to mothers on maternity leave, whereas a computer scientist might not.”

—Andrew Marritt

Founder, OrganizationView

Data policies and regulations exist for good reason: to keep everyone safe from data misuse, fraud, and unethical and illegal activity. The increasing availability of data and the increasing ease of analysis should not be used to justify unconstrained and ill-conceived analyses. For example, organizations might have the ability to collect information on marital status or the number of children in an employee’s family, but using that information to make decisions about employees would be inappropriate in some jurisdictions or a violation of employment law. Furthermore, no organization should take action on the basis of the marital or family status of its workers. Eric Mackaluso, Senior Director of People Analytics, Global HR Strategy & Planning, ADP, further points out, “It’s an ethical question; just because you can do it doesn’t mean it’s the right thing to do.”

HR domain expertise is extremely useful in ensuring proper use of data. Having this expertise on your team makes you better prepared to avoid the pitfalls and dead ends that result from spending time on statistical relationships that are inappropriate, potentially unethical, and possibly irrelevant for consideration. As a cautionary tale, consider the case of a multinational organization we encountered. In this example, an entire analytics project was derailed because it pointed to recommendations that were potentially discriminatory. The analysis was sound and the business question was highly relevant to the organization, however, the team failed to spot the warning signs until the storytelling phase with the executive sponsors. At this point the project was halted. Upon reflection, the analytics professional realized this outcome could have been avoided with proper knowledge of HR practices surrounding the use of people-related data.

You must also be mindful that data collected for some purposes cannot always be analyzed for other purposes. Even if you have what appears to be the perfect dataset, you must respect legislation, regulations, and policies that indicate it is inappropriate for further analysis. In cases such as this, alternative data might need to be identified or new data collected. When collecting new data, do so with an eye to the future analyses you may wish to conduct and obtain suitable permissions accordingly.

Note that often it is perfectly acceptable to analyze existing data in aggregate at the group level. For example, a retail company might want to understand differences in performance across its different store outlets. Analyzing variables such as employee survey scores at the outlet level should be perfectly acceptable. The sensitivity tends to arise when data are used for making decisions about individuals—specifically, decisions that were not intended when the data were collected. For example, employee survey scores designed to measure department-level engagement should not be used to isolate particular employees with low scores for some sort of action (such as managing them out of the business).

Finally, when collecting new data, you must be open and transparent about analytical intentions. Teams can take steps to increase employees’ comfort level with sharing their data for analytics purposes. We recommend a four-factor framework developed by Nigel Guenole and Jonathan Ferrar in 2015, identified by the acronym FORT:

• Listen to feedback on the analytics goals from people who will be affected.

• Where possible, make sharing of data optional.

• Give some recognition to those who agree to share their data for workforce analytics.

• Be transparent about everything that is done.

To summarize, the following actions are essential to ensure responsible and ethical handling of HR data:

• Understand and adhere to all legal and regulatory requirements regarding collection, usage, storage, and sharing of data.

• Understand and adhere to all company-specific data guidelines.

• Keep your knowledge of guidelines and regulations up-to-date through relationships with information councils in your organization.

• Understand the boundaries of the appropriate use of people data.

• Strive for broad approvals for future data usage when undertaking new data collection efforts.

• Establish an environment (based on gathering feedback, opting in, recognizing contributions, and ensuring transparency) that encourages employees to share their data for workforce analytics purposes.

An important structural consideration is where the workforce analytics function reports organizationally. Two broad options exist: The workforce analytics team either reports into HR or is part of an enterprise-wide analytics function. Making it part of the HR function is the most common approach. In some cases, teams report directly to the chief human resources officer (CHRO). Others report into a subfunction of HR, such as organization development, talent, HR planning and strategy, or HR information systems. Still others are part of a shared services model within HR. Chapter 3, “The Workforce Analytics Leader,” covers this.

Despite the prevalence of workforce analytics functions reporting into HR, some practitioners favor the enterprise analytics approach to organizational structure. Rebecca White, the Talent Analytics Senior Manager at LinkedIn, is part of a team that reports into the head of business operations in the finance function. The team has had great success addressing business issues through workforce analytics within this reporting structure. For example, the team has improved the efficiency of the recruiting process in support of LinkedIn’s aggressive growth strategy, and it has increased the diversity of hires, a business imperative. Although the team does not report into the HR function, HR expertise resides directly in the team.

Some experts view this approach as a desirable progression as workforce analytics becomes more established in the organization. For example, Mariëlle Sonnenberg is the Global Director of HR Strategy and Analytics at Wolters Kluwer, and her team currently reports into HR. She aspires, however, to move her team into an enterprise-wide analytics function. She would like to see workforce analytics ultimately integrated fully into the business. “Workforce analytics does not need to be separate because the analytical capabilities are an integrated part of our organization,” she says. “It does not need to reside in HR.”

In our view, reporting directly to the CHRO (or at least having direct access to the CHRO) yields the best outcomes for the analytics team and the organization. This C-level reporting structure keeps the focus of the team closely aligned with strategic business priorities and has the greatest chance of informing decision making about important business topics. If the analytics team reports further down in the HR function, it is important to have a strong relationship with and direct access to the CHRO. If the workforce analytics team is part of a broader enterprise-wide analytics function, access to knowledgeable HR professionals, particularly the CHRO, is even more important. This provides the guidance that HR expertise brings in understanding people-related issues and working with people data. A dotted-line reporting relationship to the CHRO can formalize this connection.

Damien Dellala leads the People Data and Analytics Enablement team at Westpac.2 He comes from a digital banking background: “I started in digital, doing business analysis. I always loved data and am analytically minded. I wrote the digital strategy, operating model, and governance. I delivered a new enterprise data warehouse, forced all the data in there, created it from scratch.”

Damien’s experience in digital banking meant he understood the importance of setting things up the right way in an analytics function. He took on this challenge when he started leading the analytics team in HR. “When I joined the HR team, I noticed the analytics team was very immature compared to other organizations in the bank, and this was an opportunity to take Westpac to the next level. The concept was, we need to treat our employee data like we do our customer data.”

Damien decided on some key principles:

• Make sure everyone understands what you are doing.

• Define your capability.

• Set clear goals for your team and measure supply and demand.

• Get a really good senior stakeholder, a sponsor for the team.

Damien focused on setting things up properly. Skills, capability, data governance, mission, business governance, and even the name of the group took time to decide. This is where his senior stakeholder helped to supplement his earlier experience in digital banking and build a strong team. Damien concludes, “All of this led us to undertake some important projects with strong sponsorship to support the business success.”

Many decisions will need to be made in the course of your workforce analytics activities. For example, you need to decide whether the data you have obtained have adequate quality and completeness to proceed with analysis. After you have analyzed the data, you need to decide whether the results make sense and are actionable. You also need to decide on the right set of recommendations and how best to communicate them to your various audiences. And before all of this, you must decide which projects to select and how to prioritize if the number of potential projects exceeds the team’s capacity to manage them all.

To maximize your decision-making effectiveness, establish a decision-making process that will work well for your team. Decision making can be defined as selecting a course of action (or inaction) from a set of alternatives to achieve the best possible outcome. In many ways, the decision-making process mirrors the analytics process: defining a problem, gathering information, identifying options and analyzing the pros and cons, choosing an option based on evidence, implementing, and following up (see Figure 14.2 for our recommended workforce analytics decision-making process). Approaching decisions in such a structured manner should result in better outcomes than relying on intuition and “gut feel,” which is the very reason for embracing workforce analytics in the first place.

Figure 14.2 Workforce analytics decision-making process.

Seeking a broad perspective on key decisions, including perspectives that differ from your own, is also beneficial. In a 2014 Scientific American article, Katherine Phillips of Columbia Business School cites research showing that diverse groups challenge and process information more deeply, resulting in better decisions. This means the decision-making process will likely be less comfortable and more time consuming, but getting better outcomes is worth navigating the additional challenges. Diversity of opinion also provides useful checks and balances that help you avoid overlooking important facts and considerations. Engaging a broad set of stakeholders in key decisions helps secure commitment to the decisions as well, improving the chances of follow-through.

Finally, determine what you will do in case of an impasse. At some point, differing perspectives will likely impede getting to a decision. You will want a defined and agreed approach for moving forward. This could take the form of a designated final arbiter for different types of decisions or an advisory panel that will weigh in. You might even insist on consensus among a specific group of stakeholders for certain decisions. For particularly challenging decisions, agreeing on a set of decision criteria might be a good first step, followed by evaluating the alternatives relative to the criteria. For example, in deciding which project to undertake, criteria could include the following:

• Project complexity

• Business value (quantitative and qualitative)

• Cost of implementation

• Ease of implementation

• Willingness to implement

Agreeing on the criteria beforehand makes the actual decision-making process easier and more objective.

Table 14.1 shows examples of typical workforce analytics decisions and potential methods for resolving an impasse. Thinking through the options and choosing the most effective one for your organization’s culture will improve the time to resolution.

The best way to address the full spectrum of decisions you are likely to encounter—both routine and unanticipated—is to establish an advisory panel to provide guidance and assistance as needed. This can prove invaluable in deciding which projects are strategic, what data will be needed, how to handle privacy issues, and how to prioritize multiple project demands. Advisory panel members will likely vary, depending on factors such as the reporting structure for the analytics team; the panel might include representatives from finance, legal, HR, and other functions. The additional perspective the advisory panel provides will enable the team’s success, ensure the right sponsorship, and hold the team accountable to the organization and the workforce (in addition to HR).

Table 14.1 Examples of Typical Workforce Analytics Decisions and How to Resolve an Impasse

Well-defined structures and operating procedures help optimize your team’s efficiency and effectiveness. A properly designed team structure, well-defined roles and responsibilities, and a systematic approach to conducting projects will ensure that your team focuses on high-value work.

An important decision is how best to structure your team, given its mission and scope. If your scope includes both HR metrics reporting and statistical analyses, you need to decide whether to separate analytics and reporting organizationally or to keep both responsibilities within a single team. Teams can achieve success in both scenarios; the option you choose should be consistent with and enable your team’s mission. Importantly, if reporting is part of the mission, you should have clear and distinct definitions of reporting versus analytics, to avoid the common situation of reporting tasks consuming the time and capacity of the team’s analytics experts.

An example of separating reporting from analytics comes from Thomas Rasmussen, Vice President of HR Data and Analytics at Shell Oil and Energy. As you learned in Chapter 13, “Partner for Skills,” when tasked with building an end-to-end value chain from data through reporting to analytics, Thomas did so by separating the components into distinct teams. This allowed each team to focus on its core competencies, with reporting expertise residing within a shared-services center of excellence (CoE), and helped the analytics team focus on applying advanced statistical techniques to solve business problems.

Without this clear separation, you risk having business managers turn to anyone on the analytics team to support their reporting needs. When highly skilled analysts spend time on routine data requests, the team is not optimizing its capabilities. Another dynamic that can consume the analytics team’s time with reporting tasks is the differing skill levels—specifically, the business knowledge and acumen common among analytics professionals. Christian Cormack, Head of HR Analytics at AstraZeneca, describes this: “Despite having a separate reporting team, we found that the analytics team was being used as a high-quality reporting service. As the analytics team was closer to the business, we were often able to provide a more relevant answer. To be successful, whether in analytics or reporting, you need to really understand in detail what people in the business do; otherwise, it’s very hard to put the business questions into context.”

A different perspective comes from Damien Dellala at Westpac Group. Damien found synergies in keeping reporting and analytics together in a single team. Damien explains, “The data warehouse was the underlying infrastructure, and it makes sense to have analytics off the same common platform as reporting, therefore leveraging an aligned dataset. There’s a lot of prototyping that needs to be done first with a nice synergy at this stage of development. You hope your reporting generates the right questions to be asked of the analytics, and the actions from the analytics should inform the reporting.”

Placid Jover, Vice President of HR–Organisation & Analytics at Unilever, goes even further, arguing that reporting versus analytics is a meaningless distinction. “Not everyone needs reporting, just like not everyone needs some of the flashy predictive modeling. The business just knows that it has a problem that needs to be solved, and if you solve it, the business does not care that you used a reporting solution or an advanced analytics solution.”

Clearly, differing perspectives result from varying experiences and philosophies. Our view is that analytics goes beyond reporting. If reporting is part of your function’s scope, be very clear about the distinction between analytics and reporting and who is responsible for each. Ultimately, you will choose the setup that best supports your mission, best matches your culture, and is the most feasible to implement based on your organization’s existing capabilities (within HR as well as across the broader enterprise).

To enable productivity and avoid confusion, clarity of roles and responsibilities in organizations is essential. Tammy Erickson, in a 2012 Harvard Business Review article, wrote that teams perform and collaborate best when each member’s roles and responsibilities are clearly defined. This clarity allows team members to execute well even when the task at hand is ambiguous; they stay focused on the work, as opposed to negotiating who does what. The leader must ensure that roles are clearly defined and understood.

A responsibility matrix can be a useful framework for defining and communicating roles and responsibilities. One such matrix is commonly known by the acronym RACI, for responsible, accountable, consulted, and informed. The framework is used by creating a matrix of tasks and roles and then, for each cell in the matrix, indicating the following:

• Responsible. People who perform the work needed to execute a task

• Accountable. The person who is ultimately looked to for task completion (only one person should be designated accountable for any given task)

• Consulted. People whose opinions and input are solicited for their subject matter expertise (typically, two-way communications)

• Informed. People who need to be aware of the task and are kept updated on progress (typically, one-way communication)

This is one approach for achieving the clarity needed for success. Several variations of this approach have been developed as well; you can find them on publicly available sources (for example, www.racitraining.com). Select the approach that works best for your team and ensures the following:

• The buck stops here. For each major task, agree on the one person ultimately accountable for its successful completion.

• Nothing slips through the cracks. Agree on who will actually perform each task.

• No work takes place in a vacuum. Identify who to consult for input and who to update on progress, decisions, and outcomes.

Figure 14.3 illustrates how a partial RACI matrix might look for a workforce analytics project; this is an example and not intended as guidance for all projects. In this hypothetical example, a three-person workforce analytics team consists of the leader, the data scientist, and the industrial-organizational psychologist. The team must work with four stakeholders: a project sponsor, a data owner, a subject matter expert, and the organization’s data privacy officer. This example demonstrates that, for each task, a single person is accountable to ensure completion and specific individuals are designated as responsible for carrying out the work. In other words, the framework creates clarity about who is doing what.

Figure 14.3 Sample RACI matrix.

Another operating procedure to consider is how the team will conduct its work. When that work involves advanced analytics, it’s best to think in terms of projects with a defined beginning (project initiation), middle (project execution), and end (project conclusion). Our recommended approach to managing projects is to adopt a consulting model, with the attendant discipline that ensures clarity of objectives and deliverables, well-planned execution, and proper completion. See Figure 14.4 for an illustration.

Figure 14.4 Example consulting approach to project management.

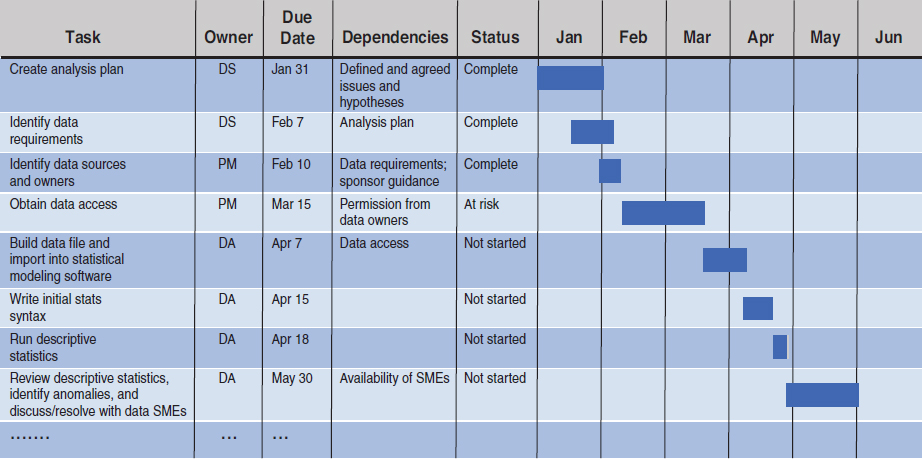

Well-managed projects are initiated with clearly defined objectives, designated project teams with specified roles and responsibilities, defined deliverables, and an initial high-level timeline. One of the most important roles is the project manager, who has accountability for fulfilling commitments, managing the team, communicating with stakeholders, negotiating changes when needed (for example, extending timelines and responding to changing priorities), and ensuring high-quality work. During the initiation phase, the project manager assembles the team, identifies stakeholders and sponsors, gathers preliminary input and perspectives, creates a high-level project plan with overall timelines and milestones (see Figure 14.5), and conducts a project kickoff meeting to discuss and establish the plans with the project sponsor and team.

Figure 14.5 Sample high-level project plan.

At this planning stage, it is helpful to build in work activities for potential actions to be implemented, along with methods for assessing the impact of actions. Although you cannot know at this early stage what the results will indicate or what actions will be recommended (or who will be responsible for implementing them), it is important to make explicit in your planning that implementation and follow-up evaluations are expected. In other words, the project does not end when results are presented. Implementation and assessment activities should be part of the project plan.

When the project is formally kicked off, a detailed project plan might be necessary. The rigor needed depends on the size and scale of the project. For more extensive projects (for example, 6 to 12 months or longer in duration), more detailed project management is needed. This includes specifying tasks, due dates, owners, dependencies, key meetings, and milestones. The project manager will track task status on a regular basis, highlight risks, identify and implement mitigating actions, and escalate issues to senior project leadership when needed. For shorter projects, a simpler high-level project plan will suffice. See Figure 14.6 for a sample portion of a detailed project plan.

Figure 14.6 Sample portion of detailed project plan.

With project management processes firmly in place, the team can proceed with the analytics work. This includes further defining the key issues and hypotheses, identifying data and analysis requirements, collecting and analyzing data, developing insights and recommended actions, and developing the story to be communicated.

In establishing his analytics operating model, Placid Jover, Vice President of HR–Organisation & Analytics at Unilever,3 has some clear advice. He believes that the following three points are essential in delivering successful analytics projects:

• Make better decisions about which projects to undertake: “Understand the way you are making money and losing money, where you are competing well and not competing well, and so on,” Placid says. He further explains that if you focus on the business, deciding which analytics projects to choose becomes much easier.

• Get the right skills for the right analytics: “Once you know the problems and hypotheses, make sure you then bring in the right people. Don’t just use Excel; this will not make you a good analytics person.” Placid strongly believes that you need to match the skills to the desired level of analytics. This can include bringing in a third party or other experts from elsewhere in the company. Whatever you do, bring in credible people and be clear about everyone’s roles and responsibilities.

• Be accountable with numeric targets: “If you can’t marry your agenda with the numbers agenda, then you will not succeed,” Placid says. He is clear that you need to be numerate not just in your analysis, but also in the way you tell your story and take accountability. Demonstrating success in a numerical way is important for a team’s credibility in the company.

When creating an analytics team, Placid advises taking on the right projects with the right skills to maximize your chances for success.

When the project execution phase is complete, closeout actions begin. Design an implementation plan for the recommended actions. Include key milestones, implementation responsibilities, change management actions, and success metrics.

Formal feedback should be given to team members (in addition to ongoing informal feedback throughout the project duration). Feedback should be gathered from project sponsors and stakeholders, to get their perspective on what went well and what future projects can improve.

Finally, the team should discuss and document the lessons learned and the insights gained from this project. For example, if you learned that you underestimated the amount of time it would take to obtain data access, build additional time into your next project plan for that activity.

If an organization makes an investment in workforce analytics, it is only reasonable to expect a positive return on that investment. The analytics team must demonstrate the value of workforce analytics through a well-structured business case and the capability to track the team’s performance through a set of relevant metrics.

A business case is a formal, structured, and logical justification used to obtain approval for an investment. It might be needed to justify setting up a team or function, or for obtaining initial funding for exploratory projects that will pave the way for more substantial projects in the future. As Mariëlle Sonnenberg of Wolters Kluwer puts it,“It takes investment to show what you can do. Because it is behavioral science, you always need a bit of experimenting with the data. This requires time, resources, and an investment.”

In addition, a business case can be used to justify investment in specific technologies to support the team, or for changing the skills or direction of the team to “take it to the next level.” This was the approach for Arun Chidambaram, Head of Global Talent Analytics at Pfizer: “It is a good idea to plan for growth and get investment early on. Why would you plan to keep trying to compete with the same people in your team if you could do better with different people?” Arun also regularly revises his plan against the demand from the business:“Once you have a solid analytics base, then be flexible and grow where your demand is, including growing skills in new countries and experimenting with new technologies when needed.”

Finally, a business case should include a clear statement of the problem, the impact of the problem (such as unnecessary costs, inefficiencies, or negative effect on a company’s brand), the recommended solution, the investment required for the solution, and benefits expected from the solution. Impact and benefits should be comprehensive and can include quantifiable as well as qualitative information. The business case should compare the benefits of the recommended action with the cost of doing nothing about the problem.

For workforce analytics, your focus should stay on linking people-related issues to organizational outcomes. The benefits of workforce analytics typically far exceed the investment needed. If you consider that people-related costs are among the largest expenditures for an organization, you have ample opportunity to bring value to your organization by improving the effectiveness of people-related processes and practices.

“HR has opportunities to think of their employees more like customers and leverage data that is generated from user interactions. Between 50 percent and 60 percent of operating expenses are people related. By looking at employees as customers, there are many business case examples for analytics across the employee lifecycle, from talent acquisition, to engagement, productivity to retention.”

—Damien Dellala

Head of People Data & Analytics Enablement, Westpac Group

In building the business case, you should work with stakeholders and prospective project sponsors. When consulting with them about what is possible, you might find it helpful to present case studies of similar work that has been well executed and clearly shows the return on investment (for example, quantified value of improved performance, faster time to productivity, or reduced cost). This helps set expectations and, if necessary, stimulates conversation about the expected deliverables of the analytics work.

In addition to comprehensively quantifying the benefits of workforce analytics, you must fully understand the cost of the investment. Specify what is needed in terms of people (internal staff and external partners), workspace, tools and technology, and any other expenditure needed. Be sure to obtain the organization’s commitment to the resources and funding required in exchange for your commitment to deliver value.

You’ve made projections and commitments in the business case about benefits that will result from your analytics work. To build momentum and keep the team funded and functioning, you need to demonstrate those benefits as they are realized. To do this, it is important to agree on a set of metrics for your team. Two broad categories of metrics exist: outcome metrics and proximal metrics.

• Outcome metrics. These metrics are your ultimate indicators of success. For example, what cost savings did you achieve? By how much did you improve productivity? How did customer satisfaction ratings change as a result of better enabling the customer support staff? How much did contract extensions and renewals increase by keeping customer facing staff in their roles for a longer period of time? Of course, you do not want to wait until the end of a project to learn that you did not get the result you were intending. This is why proximal metrics are so important.

• Proximal metrics. These metrics serve as interim measures of how you are doing relative to your ultimate outcome, and they allow for timely course correction as needed. Suppose your organization has a problem with contract extensions and renewals—specifically, compared to the competition, your company’s rates are subpar. Suppose, then, that your analyses reveal, as hypothesized, that customers are dissatisfied when the people working on their account change frequently. You recommend extending client assignment length from an average of four months to eight months, thus providing more continuity for clients. The recommendation is agreed upon, and after 12 months, you measure year-over-year renewals and extensions. Unfortunately, the rates are the same as last year at this time, before the intervention. Was the recommendation ineffective? Perhaps, but what if staff members weren’t actually staying the full eight months as recommended? Measuring the staff assignment duration would be a proximal metric that could shed light on an unexpected outcome—better yet, it could indicate an implementation issue that the company could fix before measuring the outcome metric and drawing a conclusion.

For each project your team undertakes, agree on a concise set of outcome and proximal metrics with the sponsors. Ensure that you are actually able to measure all your planned metrics, and be prepared to act on the results. Finally, keep in mind that not every outcome metric will have a monetary value associated with it. Some people-related objectives have a nonfinancial goal for individuals, the organization, and society. You will still want to measure your outcomes relative to that purpose, but you will do so in a nonfinancial way.

A well-planned operating model drives efficiencies and allows the workforce analytics team to focus on the work at hand: successfully implementing analytics projects that improve business results. Following are the key actions for establishing your operating model:

• Confirm your vision and mission, incorporating the renewed perspective that comes with experience.

• Understand data privacy legislation, regulations, and policies for all countries in which your organization operates, and adhere to them at all times.

• Understand the sensitivities of HR data; rely on local HR expertise to guide your analysis and ensure that you operate within policies and guidelines.

• Request broad permissions for data use when embarking on a new data collection effort, and encourage employee participation by applying the FORT framework (gathering feedback, opting in, recognizing contributions, and ensuring transparency).

• Ensure that the reporting structure provides access to the CHRO.

• Manage your team’s scope and configuration to ensure that analytics does not get displaced with metrics reporting activities.

• Clearly define the roles and responsibilities of your team and the people you interact with to execute your mission.

• Agree on a decision-making process that will serve your team well, and use an advisory panel as part of your process.

• Adopt a consultancy approach to project management, with clearly defined activities and checkpoints during project initiation, execution, and conclusion.

• Build a business case at least annually that contains a comprehensive view of investments and benefits, to demonstrate return on investment and obtain commitment for funding.

• Agree on and implement your own outcome and proximal metrics to hold your team accountable for delivering value to the organization.

1 Implemented in 2016 and 2017, the EU-U.S. and Swiss-U.S. Privacy Shield Frameworks are mechanisms to comply with EU and Swiss data protection requirements when transferring personal data from the European Union and Switzerland to the United States in support of transatlantic commerce (www.privacyshield.gov).

2 Westpac was Australia’s first bank, established in 1817 as the Bank of New South Wales; it became Westpac Banking Corporation in 1982. It has operations mainly across the Asia Pacific region, with nearly 13 million customers (www.westpac.com.au).

3 Unilever is an Anglo-Dutch multinational consumer goods company coheadquartered in Rotterdam and London. Its products include food, beverages, cleaning agents, and personal care products. It had a turnover of almost €53 billion in 2016, and its products are sold in approximately 190 countries globally (www.unilever.com).