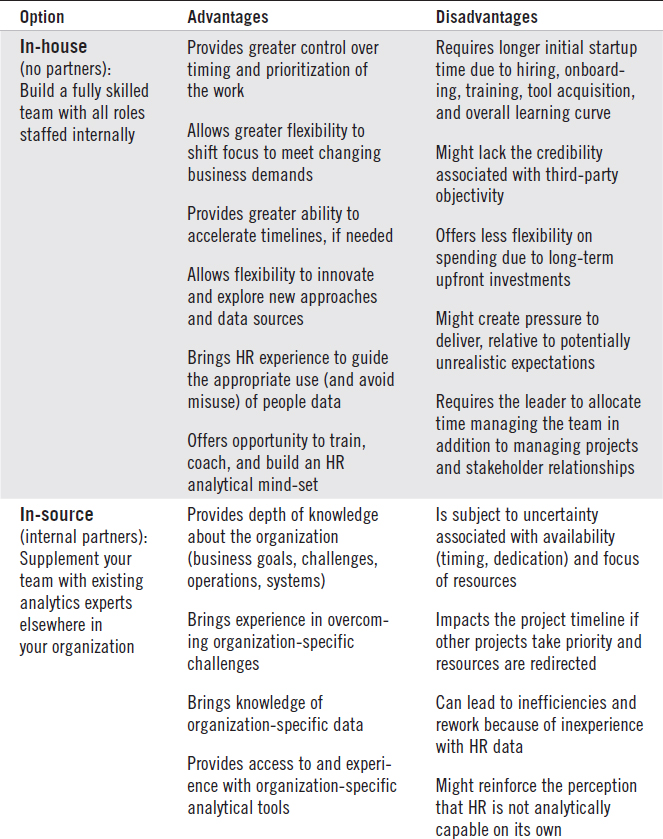

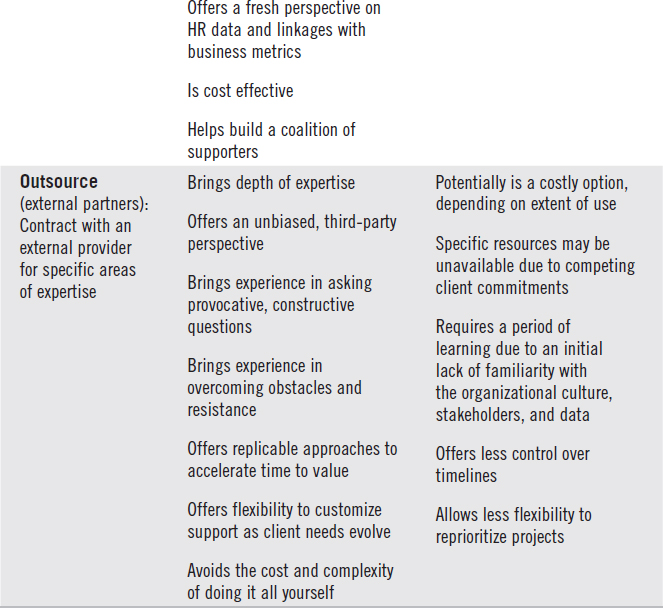

Table 13.1 Advantages and Disadvantages of Partner Options

“Synergy comes from knowing who you are, and finding the strength in others to complement your strengths.”

—Jeremy Shapiro

Global Head of Talent Analytics, Morgan Stanley

Team up or go it alone? When setting up a workforce analytics function, you have various options for bringing together the needed skills, including partnering with experts from inside or outside your organization. All workforce analytics functions need a core set of foundational skills, but beyond that, team composition and use of partners can vary depending on the circumstances. Although having all the required skills within the function has benefits, partners can provide a unique advantage in overcoming the challenges an analytics team faces. It is also worth noting that the partner options appropriate for your initial team formulation might not necessarily match your ultimate operating model. As circumstances change, team composition and partner relationships will likely evolve as well.

This chapter discusses the following topics:

• Deciding when to partner for skills

• Options for acquiring skills: in-house, in-source, and outsource

• Factors to consider when choosing among the options

Partnering involves some form of contracting or agreement, either formal or informal, that defines the relationship and obligations between the workforce analytics team and a third party. The third party can be internal (from another business unit or function) or external (a vendor or consultancy). Partners can assist with data, technology, and skills. Chapter 18, “The Road Ahead,” discusses the emerging field of partnering for data, and Chapter 11, “Know Your Technology,” covers partnering for technology. When contracting for skills, the topic of this chapter, your partner can be an individual expert, a large consultancy, or some variation in between. The relationship can range from short-term assistance on a single project to long-term retained relationships.

A workforce analytics team might choose to partner for skills for many reasons, such as budget limitations, specific expertise gaps, or an accelerated timeline for producing results. Partnering might also be needed when the analysis is of a sensitive nature or there are potential conflicts of interest, which require third-party objectivity or separation of duties. In all these situations, partners can be an indispensable resource.

Partnering can offer a great deal of flexibility, with the nature of the relationship varying depending on the team’s needs. Some teams might only require an initial consultation for strategic guidance and advice before they can proceed successfully on their own. Other teams opt for short-term support for specific projects on an interim or as-needed basis. In other situations, teams establish effective long-term relationships with a partner that provides ongoing support. The partner might even serve as an extended member of the workforce analytics team. The next section discusses partner and non-partner options to consider when assembling the skills needed to fulfill your workforce analytics vision and mission.

Earlier chapters (Chapter 3, “The Workforce Analytics Leader,” and Chapter 12, “Build the Analytics Team”) describe the skills needed for success, including the minimum skills needed internally within the workforce analytics team. This includes a workforce analytics leader with a breadth of knowledge who is well versed in the art of business acumen; a team member with a deep understanding of human resources (HR) data systems and the ability to extract and work with the data; and sufficient levels of HR expertise among team members to translate workforce analytics projects into the workings of the organization.

Beyond this recommended minimum, teams have flexibility in achieving the full end-to-end skill set needed for workforce analytics success. Three broad options exist:

• In-house (no partners). All required skills (the Six Skills for Success that Chapter 12 describes) reside directly within the internal workforce analytics team.

• In-source (internal partners). The analytics team supplements its skills with experts elsewhere in the organization.

• Outsource (external partners). Third-party vendors or consultants are formally contracted to support the workforce analytics team and complement their skills.

The best approach might be a combination of options—for example, in-sourcing specific skills that are readily available internally and then contracting externally for others. The following sections discuss the options in detail.

Building a fully staffed in-house workforce analytics team means having complete, end-to-end capability (the Six Skills for Success) contained within the team, with all resources reporting to the workforce analytics leader. This requires deep specialist skills that go beyond the minimum—for example, advanced statistical skills such as structural equation modeling and unstructured text analytics, or advanced communication skills such as storytelling and data visualization. People with these specialized skills need to be sourced, staffed, and continually developed into a high-performing collaborative team capable of delivering the projects needed to fulfill the workforce analytics vision and mission. Chapter 12 provides guidance on determining the specific skills needed and deciding how many people to hire.

The in-house approach for skills offers several advantages, such as control over the nature and timing of projects. Having resources all contained within a single team makes it relatively easy to reassign people to projects as needed, adjust project timelines as business demands evolve, and facilitate collaboration and knowledge sharing among team members. Another advantage of the in-house approach is the opportunity to invest time (for example, when in-between projects) to innovate and explore new statistical methods and novel data sources.

Having HR domain expertise and statistical skills on the same team also mitigates the risk of potentially misusing or misinterpreting HR data. This can happen, for example, when someone is adept at finding statistical relationships but is unfamiliar with the content and context of the data being analyzed (and, therefore, is unaware of the meaning and implications of the observed relationships).

In-house teams also have opportunities to expand their scope of responsibilities beyond specific project work, to support the overall workforce analytics mission. For example, they can engage in transformational activities such as training and coaching to increase the analytical acumen of the larger HR organization and help to advance an HR analytical mind-set.

Potential disadvantages of the in-house approach include needing to make an upfront investment in people and the tools they need to do their jobs. This requires in-depth planning for decisions with long-term implications; after committing to a team of people and purchasing a set of tools, backtracking is difficult. Staffing an in-house team also involves a lengthier initial startup time as you source candidates, bring new hires on board, train them and get them up to speed, and put tools and methodologies in place. The leader of a fully staffed in-house team can expect to spend a large proportion of time managing the team, with less time for managing projects and stakeholder relationships.

Sizable investments are often accompanied by sizable (if not outsized) expectations, and that can be the case when building an in-house analytics team. Expectations of what the team can deliver according to certain timelines could be unrealistic, leading to disappointment. Some practitioners operate with a low profile early on to avoid this issue. Their preference is to surprise stakeholders with valuable insights and results, as a way to garner further support.

Another factor to consider is the political environment in the organization, specifically in the context of challenging long-held assumptions and being able to effect change. In some organizations, an internal team might lack the credibility that comes from (perceived) third-party objectivity. Also relevant is whether HR is seen as having analytical prowess instead of being thought of primarily as a compliance-oriented and reporting function. Such perceptions can be challenging to overcome (although not impossible, as Chapter 16, “Overcome Resistance,” shows). Bringing in external expertise can help allay these types of concerns.

Thomas Rasmussen, Vice President of HR Data and Analytics, joined Shell1 with the mission of setting up a workforce analytics function. He quickly observed that Shell was already mature in two key areas: data management (including data definitions and data quality) and reporting. With Shell’s goal of building an end-to-end value chain, Thomas was asked to “take it to the next level with a focus on analytics.” Thomas achieved this by building an analytics capability within the HR function, yet keeping it separate and distinct from data and reporting, and by up-skilling HR leaders, enabling them to facilitate fact-based decision making.

Thomas recommends maintaining a balance in the team between technical expertise and business consulting skills: “It’s important to have people who are technically proficient in working with data and running statistics, as well as people who are adept at change management, who can work with stakeholders and position the results of analytics projects for action.”

Thomas also advises keeping the team relatively small (in his case, about three to five people). This forces a focus on the most important and impactful projects and keeps from overwhelming the organization with more findings than it can reasonably act on in a given period of time. With this model in place, Thomas’s team is able to focus on the highest priorities for Shell, including projects related to productivity, talent, and risk.

Given the breadth and depth of the work, the team is clearly in strong demand and is serving the business well.

The workforce analytics team can supplement its skills by bringing in people from other parts of the organization to assist with specific workforce projects. This can be a desirable option if building an end-to-end in-house workforce analytics team does not seem feasible, yet the preference is to keep workforce analytics within the organization. One variation of this option is to temporarily assign an expert to a workforce analytics project. Alternatively, a practitioner can formally transfer to the HR team from a function such as marketing or finance and apply his or her analytics know-how to the domain of HR.

“The risk modeling division inside the bank are very good partners. They have made fraud calculation predictions to very advanced levels. We use their data scientists when we need them. They are very good, they already predict customer attrition, so we just ask them to apply their models to different variables.”

—Kanella Salapatas

HR Data Manager and Reporting Service Owner, ANZ Bank

If a temporary, project-based assignment seems like a good option, it might be a challenge to borrow the time and expertise of people focused on fulfilling their own function’s mission. A possible solution is to arrange for rotational assignments that formalize participation on a temporary basis. This can be mutually beneficial for the functions and individuals involved. Cross-pollination of skills and ideas is almost always healthy for an organization, and the HR function is best positioned to structure and implement such a program. Some practitioners have mentioned that the most valuable analytics conversations happen when people from different functions meet informally and share stories and perspectives, such as during occasional lunch meetings. Rotational assignments can make such conversations more intentional and less subject to chance encounters.

Teams might also be able to leverage expertise in centralized functions such as communications on an as-needed basis. Peter Hartmann, Director of Performance, Analytics and HRIS at Getinge Group, used this approach in a previous role to in-source storytelling skills: “The ability to translate findings into a nice story is not my core competence. I translate the numbers into a conclusion and a recommendation, but when I have to take it into a nice rounded story, frankly, I am not a very good storyteller. But I know it’s important, so I’ve worked with the communications department, where they write using a journalistic approach, and this was a match made in heaven.”

In-sourcing skills offer several advantages, such as the depth of knowledge that internal experts have about the organization, in addition to their subject matter expertise. Internal experts bring a level of understanding about goals, challenges, operations, and systems that will be unmatched by an external provider or a newly hired team member. And somewhat similar to an external party, internal experts are less likely than an HR insider to have preconceived notions about HR-related projects and can bring a fresh perspective (and credibility) to the analysis.

In-sourcing is a cost-effective option that requires no substantial incremental investment, as long as all parties involved are able to fulfill their collective scope of responsibility. In-sourcing also extends the reach of workforce analytics to a broader audience within the organization, helping to build a coalition of supporters.

Among the disadvantages of relying on other people in the organization who have their own commitments and responsibilities is the uncertainty associated with team members’ availability, time, and focus to work on your projects. Other projects might take priority for them at any given time, and resources could be redirected, impacting your timelines and ability to fulfill your own commitments (although this is not an issue when resources are formally assigned to the HR team).

Another challenge is that, if the analysts are too far removed from the HR function, a lack of domain expertise could potentially lead to inefficiencies and rework. Without the HR “sixth sense” (see Chapter 12), the analysts might identify relationships in the data and recommend actions, without taking into account issues such as unfairness and discrimination.

Finally, borrowing expertise from elsewhere in the organization could give the appearance that HR is not capable of delivering analytically based insights. The in-sourcing option could potentially and inadvertently reinforce this type of preconceived notion that exists in some organizations.

Outsourcing allows you to quickly and flexibly acquire skills needed beyond the minimum capabilities. An external partner can be contracted on an as-needed basis and, if used judiciously, can provide a cost-effective option. External partners can be called upon to assist with a variety of tasks, such as advanced data management (for example, normalizing data or using predictive techniques to fill gaps in a dataset) or sophisticated analytical techniques that are difficult or unaffordable to source internally. Partners typically provide their own technology solutions to assist with these tasks, minimizing the need to invest in technology.

“Businesses don’t have two years to wait for you to build sophisticated analytical capability. By tapping into external partners, you get the skill you need immediately.”

—Mark Berry

Vice President and Chief Human Resources Officer, CGB Enterprises, Inc.

When chosen wisely, external providers will work with you as a true partner in realizing your workforce analytics goals. As Andrew Marritt, founder of OrganizationView, states, “The best consultants put themselves in the shoes of their clients.”

In addition to providing a ready source of deep expertise, external partners have the distinct advantage of providing a third-party perspective. Strong partners are skilled at asking provocative, constructive questions that might be difficult for an internal person in a politically complex environment to ask. Laurie Bassi, CEO of McBassi & Company, expands: “Our job really is shifting mind-sets by focusing on the power of asking good questions. As an outsider, this can be easier to do because we are not lost in the daily grind.”

Partners can also offer experience in overcoming obstacles and points of resistance. Peter O’Hanlon, Founder and Managing Director of Lever Analytics, says, “Partners can say the hard things and make things happen quickly because they’ve seen it before and they know how other organizations work.” Partners often bring repeatable approaches that have worked well in other organizations. As a result, you can benefit from their learning and experiences and thus accelerate the time to realizing value from analytics. Michael Bazigos, Managing Director and Global Head of Organizational Analytics & Change Tracking at Accenture Strategy, describes his approach at a previous organization: “We built a team with domain expertise as well as quantitative expertise, and we developed replicable solutions to take to clients to solve problems fast.”

Skilled external partners can customize their support to meet the evolving needs of their clients. They might be able to assume all responsibilities for statistical modeling, for example, or they might be able to coach their more advanced clients to continually improve their analytical skills. For those in between, partners can do as Andrew Marritt of OrganizationView has done and coach them to be a consumer of analytics—for example, teaching clients what to look for, what questions to ask, and how to interpret results.

In addition, not every organization has the need or desire to staff a complete analytics function in HR. Mark Berry of CGB Enterprises, Inc., asks, “Why build something internally when you can ‘buy’ deeper expertise on the outside? As an organization, you don’t have to build internal capabilities for every area of HR analytics. You can let expert service providers do it for you.”

Although utilizing external providers allows a degree of flexibility in spending, the cost can exceed that of having one or more full-time team members if the team uses external providers extensively. Another potential challenge is lack of continuity: Specific individuals at partner organizations might not always be available for your projects if they are in high demand by other clients.

External providers also need time to learn about your particular organizational culture and environment, the specifics of your data, and the details of your organization’s operations. Data security might also be a consideration because you will need to release your sensitive people data for analysis. In addition, you will likely have less flexibility to adjust your efforts to accommodate changing priorities. Organizational demands can and do shift, sometimes in the midst of a project. Keep in mind that you will still get billed for time spent on paused or halted projects, with limited, if any, value to show for it.

For Patrick Coolen, Manager of HR Metrics and Analytics at ABN AMRO Bank2, initially partnering with an external analytics firm was the way to go. “We started with an external analytics company. We didn’t want to worry about the quality of our models, so we did it to scale up quickly.” They began as a small internal team of three and, in the early days, spent their time serving as “translators” or liaisons among the business, HR, and the analytics team. The focus was on demonstrating to the business leaders how HR is impacting their key performance indicators (KPIs), the main metrics used to monitor business performance. This was time well spent.

Following early successes, the team doubled in size and increased its analytical capability. In this more mature state, it functions as “more of an internal consultancy with HR strategy-type people who have an affinity for and knowledge about statistics and machine learning,” Patrick says. Outsourcing served the team well in the beginning, and as they built internal capability over time, they were able to bring more of the data-related projects in-house. Although the analytics provider continues to play an important role in the team and handles the bigger projects, Patrick’s own team has been continually learning, becoming better informed, asking the right questions, and ultimately taking on the smaller projects themselves.

External expertise allowed Patrick’s team to quickly bring the value of workforce analytics to the business while building their own capability for the future. This proved a worthwhile investment: The team established credibility quickly, resulting in more requests from the business than the team can handle. Mission accomplished!

Table 13.1 summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of the three broad options for building workforce analytics skills: in-house, in-source, and outsource.

Table 13.1 Advantages and Disadvantages of Partner Options

We have described the Six Skills for Success that are needed for a workforce analytics team, and the options available for obtaining those skills. Now consider the factors that are important when building the team. First, follow the guidance in Chapter 12 to determine how many people with the required skills are needed, relative to the skills you are starting with and the work that needs to get done. Then consider the following factors in choosing among an in-house, in-source, or outsource approach (or some combination): budgets, skill availability, time, organizational expertise, organization size, perceptions of HR, and need for third-party objectivity.

Some organizations have the good fortune of generous budgets for building workforce analytics capabilities, but most face budgetary constraints. The amount of funding available defines the boundaries of what can initially be built. If you are in the fortunate position of having sufficient funds available, you might opt for fully staffing an internal team and supporting it with state-of-the-art tools and technology. As noted in the following sections, however, budget is not the only consideration. Teams with more limited budgets need to estimate the cost of each best-fit option and choose the path that conforms to their budget. As you execute your first few projects and demonstrate success, you will likely have further opportunities to build a business case for a larger investment.

Funding is necessary but not sufficient for staffing a team. You also need to find skilled resources in the local labor market, and certain skills such as data science might be in high demand but short supply (as a 2011 McKinsey & Company report highlighted). If you are unable to find all the skills you need locally, you might need to start with an external provider or find a way to leverage skills elsewhere in the organization. Other strategies to consider include recruiting outside your local labor market and hiring remote workers.

If you ultimately expect to build more capability in-house, you might want to start building a pipeline of skilled people you can eventually call upon when needed. For deep analytical skills, developing relationships with universities and expanding your personal network of analytics experts can help with sourcing skills in the future. Attending analytics conferences, for example, provides exposure to both ideas and the experts themselves. Associating with a network of analytics practitioners also gives you a source of potential qualified candidates when you need it.

The ability to respond to requests within the timeframe needed is an important consideration when deciding whether to hire or partner. If a great deal of urgency surrounds a particular business problem, or if the team needs to quickly demonstrate the benefits workforce analytics can bring, the fastest path might involve partnering with an external provider. Even if your long-term strategy is to build capability in-house, working with a partner initially can be an effective way to get started and accelerate time to value.

Some organizations are more analytically oriented by nature, given the type of business they are in; others might not have needed a strong analytics focus in the past. Josh Bersin, founder and Principal of Bersin by Deloitte, explains: “Insurance companies have actuaries—they understand statistics, it’s their core business. Retail companies have sophisticated analytics in customer and market segmentation. It’s starting to hit manufacturing, where there’s been a lot of focus on quality. In these industries, analytics is already embedded in the company, so it’s easier for them to get their arms around it.”

If your organization has strong analytics capabilities in functions such as marketing, research and development, finance, or supply chain, you might want to arrange access to these skills for your analytics function. This can come in the form of bringing a workforce analytics mission to an existing enterprise analytics function or bringing resources from other functions into the HR team to build analytics skills within.

The size of an organization partly dictates the approach for building analytical capability. Small organizations are likely to benefit most from outsourcing anything beyond the minimum capabilities. This is because, for a small organization, benefits are unlikely to scale to the same extent as in larger organizations. In addition, partnering allows small companies to connect with highly skilled experts when they need them, without the burden of large salary expenditures and lengthy ramp-up times. Mark Berry explains, “I don’t have to maintain those sunk costs, and I can manage the cyclical nature of the business. The outsourcing model is the right model for us.”

Another consideration is the internal perception of the HR function. In some instances, lines of business develop their own HR analytics capabilities separate from the HR function. This can occur because of a perception that HR is not meeting their business demand. For example, a business needing to hire a large number of staff in a short period of time might have prompted those business areas to develop their own analytical techniques for forecasting workforce requirements and filling vacancies.

If you encounter such a situation, a collaborative approach is recommended. Listen carefully to your colleagues’ needs, and demonstrate your team’s analytics know-how and willingness to experiment and take risks. If this situation arises an in-source approach, partnering with the line of business, is recommended. In most instances, the best outcomes result when the lines of business and HR work together to address business challenges.

Some organizations use external parties because of their impartiality and perceived credibility. In addition, some projects are sensitive in nature and preclude an internal team from working on them. For example, leadership analytics for selecting potential CEO successors would require restricted visibility, as would analytics related to a merger, acquisition, or divestiture. In these instances, partnering with an external provider will likely be necessary.

Partnering allows flexibility in acquiring the skills needed to fulfill the workforce analytics vision and mission. As your team evolves and your positive contributions to the business become clear, you will have opportunities to secure additional budget, source more skills, and, ultimately, build the function that best serves your needs. Mihaly Nagy, CEO of the HR Congress and Managing Director of Stamford Global, observes, “When organizations don’t have the resources in-house, they turn to consultants to help them on the journey. Once they see early wins, more funds become available. Then dedicated functions get built.”

Establishing a workforce analytics function does not necessarily mean staffing a fully skilled end-to-end in-house team. Although that is certainly one option, collaborating with partners (either internal to the organization or external providers) could be the best path to success. Consider the following when choosing among your options:

• Understand the options for bringing together the needed workforce analytics skills (in-house, in-source, outsource) and the advantages and disadvantages of each.

• Determine the availability of needed skills in the local labor market.

• Assess the time required for sourcing, hiring, and training new team members relative to timing expectations for project delivery.

• Estimate the cost of hiring versus outsourcing, given the skills needed.

• Assess the organization’s perception of HR, to determine whether the credibility typically associated with external experts will be advantageous.

• Determine whether the required skills reside elsewhere in the organization, and assess the feasibility of partnering with those functions to execute your initial projects.

• Investigate whether any people in other parts of your organization have undertaken their own workforce analytics efforts; if so, seek opportunities to collaborate.

• Consider all the factors (including budgets, skill availability, time, organizational expertise, organization size, perceptions of HR, and the need for third-party objectivity) to select the best option for your circumstances.

1 Royal Dutch Shell is a global group of energy and petrochemical companies that, at the end of 2015, had an average of 93,000 employees in more than 70 countries. It was formed in 1907 and is headquartered in The Hague, the Netherlands. Shell is helping to meet the world’s growing demand for energy in economically, environmentally, and socially responsible ways (www.shell.com).

2 ABN AMRO serves retail, private, and corporate banking clients with a primary focus on the Netherlands and with selective operations internationally. In the Netherlands, clients are offered a comprehensive and full range of products and services through omni-channel distribution, including advanced mobile application and Internet banking (www.abnamro.nl).