In the aftermath of the state investigations, political pressure for radical change in the Port of New York could not be ignored. The mayor, Common Council, and the Democratic political machine, however, opposed all efforts to move control of the port from the city to the state. Finally, in 1870, the city and the state agreed to modify the city charter and created a new municipal agency, the Department of Docks.1 The charter gave the new department sweeping power over the Manhattan waterfront. Where private development formerly had added new land to the shoreline, built piers and bulkheads, and managed the city’s piers, a public agency would now take over and eliminate the chaos on the waterfront. No longer would there be a lack of responsibility and accountability, since a public agency—not private interests—would control the waterfront.

Initially, five commissioners, appointed by the mayor, would oversee the new department, but in 1873, the state reduced that number to three. The legislation granted far-reaching powers to the Department of Docks. Sidney Hoag, assistant chief engineer of the department in 1905, details these extensive changes, which gave local government broad control over the city’s premier asset: the water surrounding Manhattan Island. The Department of Docks had jurisdiction over the entire Manhattan waterfront, including Governors Island, Ward Island, Randall’s Island and Blackwell’s Island (now Roosevelt Island)—a total of 38 miles of waterfront. The department was able to

• take possession of private piers and bulkheads, with owner agreement as to the purchase price;

• request the City Council to take legal proceedings to acquire piers and bulkheads by condemnation, if a price could not be agreed on;

• make contracts for constructing and repairing piers and for dredging slips;

• build pier sheds, for the protection of cargo;

• lease, at public auction, piers and wharf property belonging to the city for a period not to exceed ten years; and

• make rules and regulations for the use of the piers and bulkheads.2

At first, the new department would have a limit of $350,000 a year to spend on repairs to and reconstruction of the piers, bulkheads, and slips. In addition, the city comptroller would issue bonds, with the approval of the commissioners of the Sinking Fund, to repurchase the waterfront. The amount of bonds to be issued could not exceed $3,000,000 each year.

The new charter explicitly separated the finances of the Department of Docks from the general budget of the city. Leases for piers and ferries, as well as wharfage fees for the short-term use of piers and bulkheads, would be collected by the Department of Docks and kept in a separate account. The monies were to be used to cover expenses and pay the interest and principal on the bonds. Any remaining funds would be transferred to New York City each year, to reduce city debt. The charter prohibited the use of any city tax revenues for the Department of Docks, so it would be self-financing. To the modern ear, an expectation that a governmental agency would be self-financing from user fees and not rely on taxpayers may seem discordant. Despite the dilapidated condition of the city-owned piers, documented by the Sinking Fund study, in 1856 the East River piers still generated revenues of $61,005, and those on the Hudson, $65,500. Once the department repurchased, rebuilt, and modernized the waterfront, dramatically increased revenue seemed assured.

The Department of Docks, as a public agency, exercised power independent of direct oversight by the mayor or the Common Council. The new agency’s expenditures remained outside of the city’s normal review and approval process. The independent structure of the Department of Docks foreshadowed the creation of public authorities fifty years later, such as the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Numerous other authorities followed the establishment of the Port Authority, and, over time, they have exercised enormous power over transportation in the entire New York metropolitan region. Today a new generation of public and semipublic authorities have led the extraordinary rebirth of the city’s waterfront that dazzles New Yorkers and visitors alike: the Battery Park Housing Authority, the Hudson River Park Trust, and Friends of the High Line.

As soon as the new commissioners of the Department of Docks convened, they took up the task of selecting the engineer-in-chief. After some deliberation, they chose George B. McClellan, a West Point graduate, Civil War general, and the youngest candidate ever to run for president of the United States. The arrogant McClellan demanded and received a salary of $20,000 a year, twice that of the governor of New York. McClellan hired a professional staff and work began. Before any rebuilding could commence, however, the new department needed to develop a master plan for the revitalization of the Manhattan waterfront. For the first time in the city’s history, a rational planning process involving the shoreline of the island commenced.

One problem arose immediately: no systematic records of the waterfront’s development could be found. The department’s staff members conducted a title search of all water-lot grants, going back to 1684, to try to determine who owned the waterfront. They could not find any details of when the city-owned piers had been constructed, who constructed them, and at what cost. Even more-complicated problems involved the present ownership of the private bulkheads and piers, which had been sold and then resold over time. The Department of Docks planned to repurchase the privately owned piers and bulkheads and thus needed to identify the legal owners, in order to negotiate with them.

The department’s engineers concentrated their initial efforts on the bulkhead, the boundary between the city’s outermost streets and the water. The master plan included building a solid bulkhead wall of uniform design and height around the perimeter of the entire southern half of Manhattan Island.3 With a solid bulkhead, and the water dredged to a proper depth, South and West Streets would serve as wharves for smaller boats and barges, adding significant space along the waterfront.

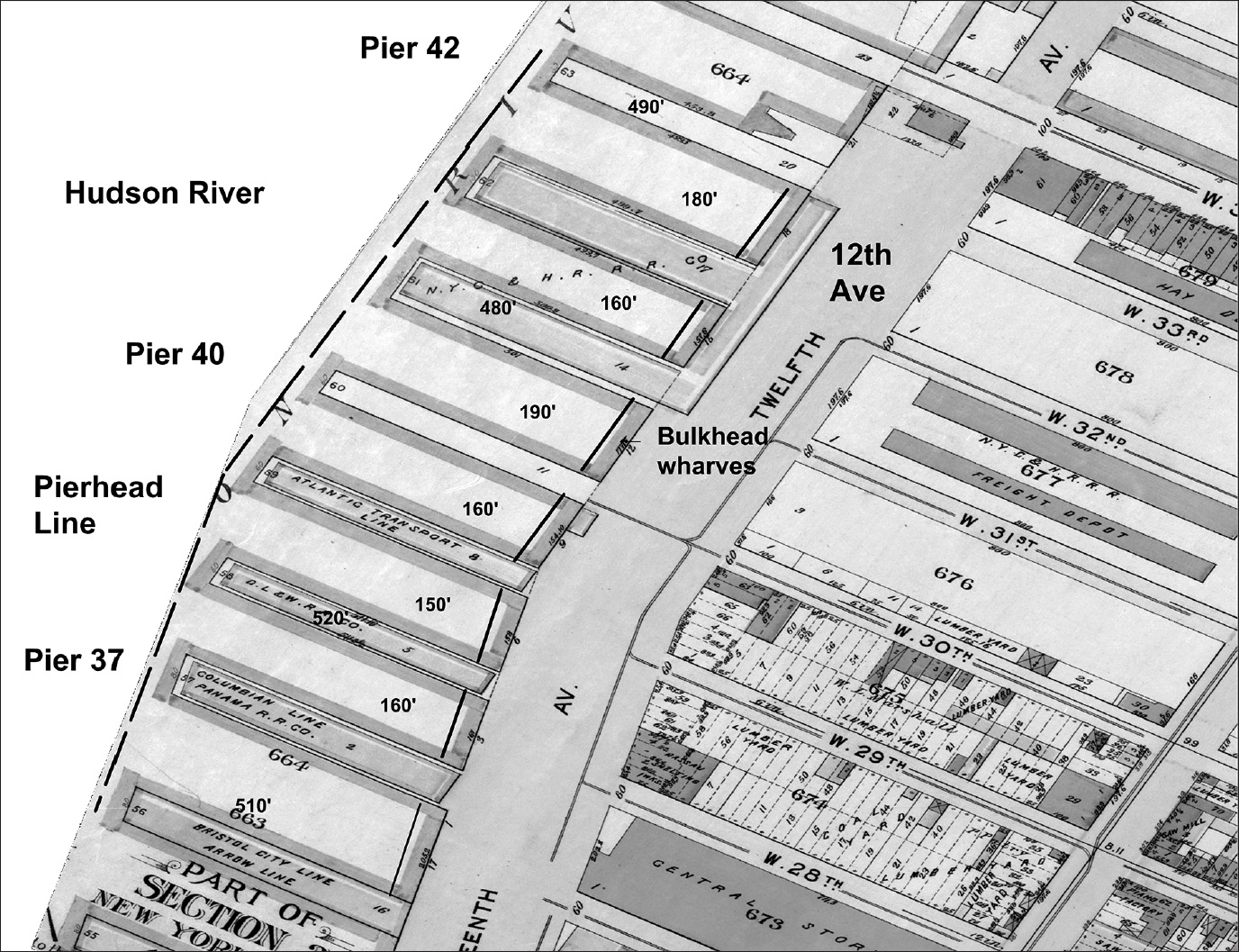

Map 7.1. The Department of Docks’ master plan for a new bulkhead and piers on the Hudson River, 1891. When completed, the master plan transformed the waterfront. The new piers extended out into the Hudson River to the pierhead line and were close to or over 500 feet in length. The relatively uniform width between the piers opened up space along the new bulkheads for small ships, barges, and car floats. Source: Created by Kurt Schlichting. Source GIS layer: historic street and pier maps, New York Public Library, Map Warper.

The pier line, established by the State of New York in 1856, defined the maximum length for all the new piers the Department of Docks planned to build. The master plan specified uniform distances between the new piers, to ensure slip space for two large ships at adjoining piers. An 1891 map of the rebuilt Chelsea waterfront between West 28th and West 33rd Streets illustrates the successful implementation of the master plan (map 7.1).

Miles of piers and their adjacent bulkhead remained in private hands, a legacy of the water-lot grants, which went back two centuries. As Hoag notes, “It appears safe to estimate that the city relinquished 95 percent of the waterfront on both rivers below Forty-second Street by this practice [water-lot grants].”4 The powerful railroads controlled much of the waterfront at that point, and they willingly paid very high lease rates for access to Manhattan’s shore. The Department of Docks raised capital to buy back the waterfront by issuing bonds over the next three decades, from 1870 to 1900. It would pay $19,319,981 to do so, an enormous expenditure.5

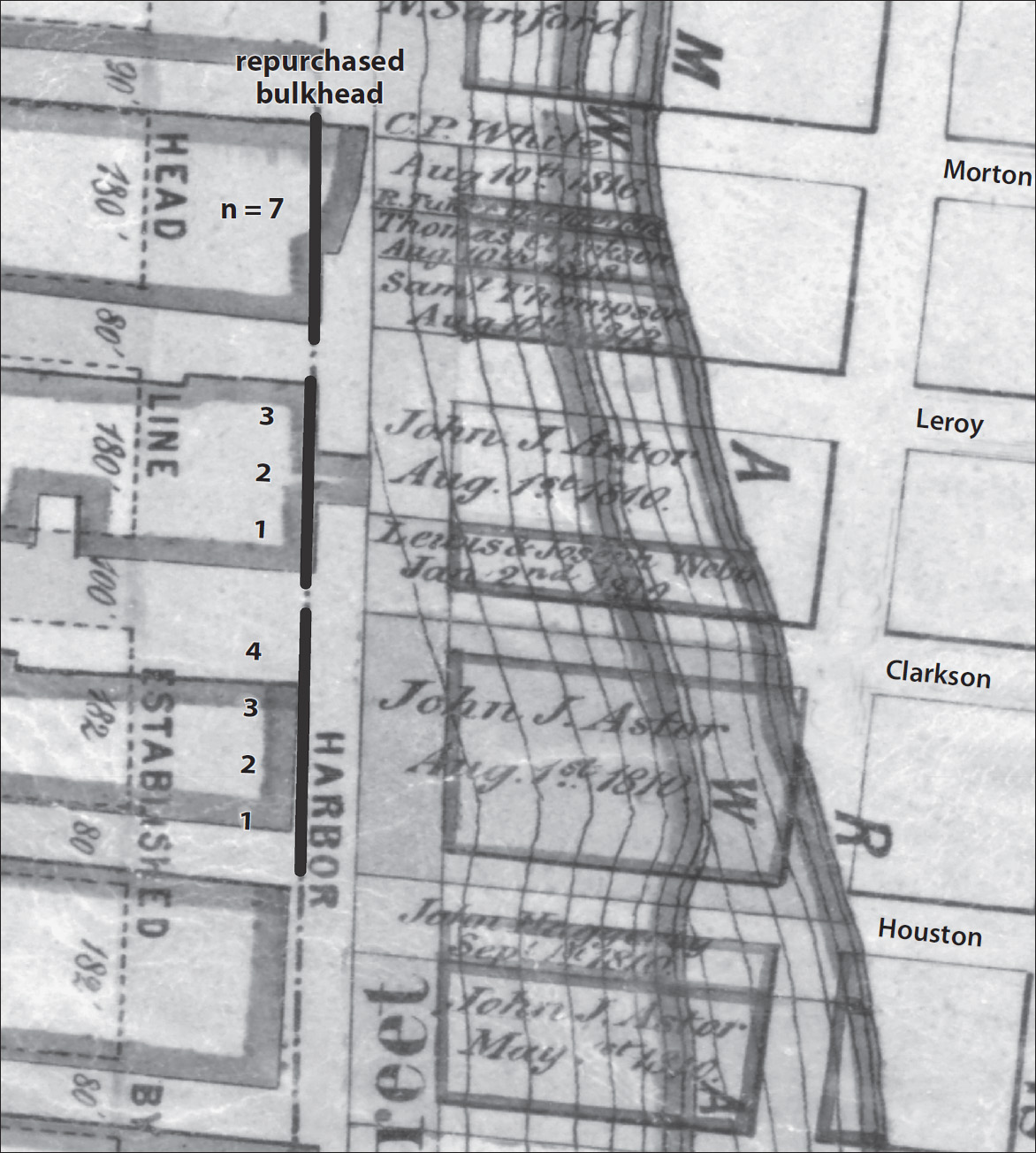

The Hudson River shoreline in Greenwich Village provides an example of the complicated process to repurchase the waterfront (map 7.2). In the first two decades of the nineteenth century, on the three blocks between Houston and Morton Streets, the city granted ten water-lots to the west of Greenwich Street, then the water’s edge. In turn, the grantees built West Street and then filled in the land from Greenwich Street out to the new shoreline. Among the grantees, John Jacob Astor stands out. Astor achieved fame as the founder of the American Fur Company, which monopolized the fur trade. A greater share by far of Astor’s vast fortune, however, came from real estate speculation in New York, including his water-lot grants on the Hudson River.

In the case of these ten grants, over time the original grantees sold their water-lots. By the 1870s, nineteen private owners controlled this section of the waterfront. The Department of Docks could not reach an agreement with the owners, so it went to court to condemn these properties and have the court determine the final cost. The court typically awarded $500 to $600 a foot for a bulkhead, but for the 200 feet of bulkhead between Clarkson and Leroy Streets, the court awarded $203,563—significantly more than $500 a foot.6 The department, in its haste to begin construction, seized the property and started work while the court deliberated. This action proved to be a costly move, as the court awarded the owners interest for the time between when the department started work and the final court settlements.

On the East River, the Department of Docks purchased the bulkhead between Beekman Street, Pecks Slip, and the Williamsburg Ferry. As it did on the Hudson River waterfront, the master plan included building a new bulkhead along South Street, on the river, and widening the street. From the new bulkhead line, the department planned to remove all the old piers and replace them with new piers of uniform design. The old bulkhead and piers belonged to the descendants of some of the original Dutch settlers, the Schermerhorns and Ver Plancks, who were grantees of the earliest water-lots. In 1905, the Schermerhorns received payments totaling $106,585, and the Ver Plancks, $323,764, close to a third of a million dollars.7 The families also retained title to the made-land created in earlier centuries on their water-lots between Pearl and South Streets, further enriching both dynasties.

Map 7.2. Hudson River water-lots and Department of Docks bulkhead repurchase, extending from Houston Street to Morton Street. To rebuild the bulkhead, the Department of Docks had to repurchase the water-lot land on the shoreline. The made-land across West Street remained as private property, creating enormous wealth for the original grantees and their descendants. From Houston Street to Clarkson Street (four separate parcels of land), the grantee was John Jacob Astor (August 1, 1810). From Clarkson Street to Leroy Street (3 separate parcels of land), the grantees were Lewis and Joseph Webb (January 2, 1810) and John Jacob Astor (August 1, 1810). From Leroy Street to Morton Street, the grantees were C. P. White et al. (1812–1816). Source: Created by Kurt Schlichting. Source GIS layer: historic water-lots map, New York Public Library, Map Warper.

When a government condemns private property for a public purpose, the owners often argue in court that the process represents an unconstitutional “taking” of property, which is prohibited by the Fifth Amendment. The Department of Docks, however, did not buy back the water-lots, that is, the made-land out from the original shore. They typically bought only the bulkhead along West and South Streets. New land created by filling in the original shoreline remained the private property of the water-lot grantees and their descendants, and many great real estate fortunes in New York history can be directly traced back to the creation of new waterfront land through water-lot grants.

Today, on the block between Clarkson and Leroy Streets at West and Washington Streets, the seven properties there are assessed at a total of $10,211,100. On West Street between Leroy and Morton Streets, two sleek new apartment buildings, with stunning water views, together are assessed at $55,396,830.8 The extraordinary value of these buildings rests on their expansive view of the Hudson, where once-decrepit piers and the crumbling West Side Highway had blocked even a glimpse of the river.

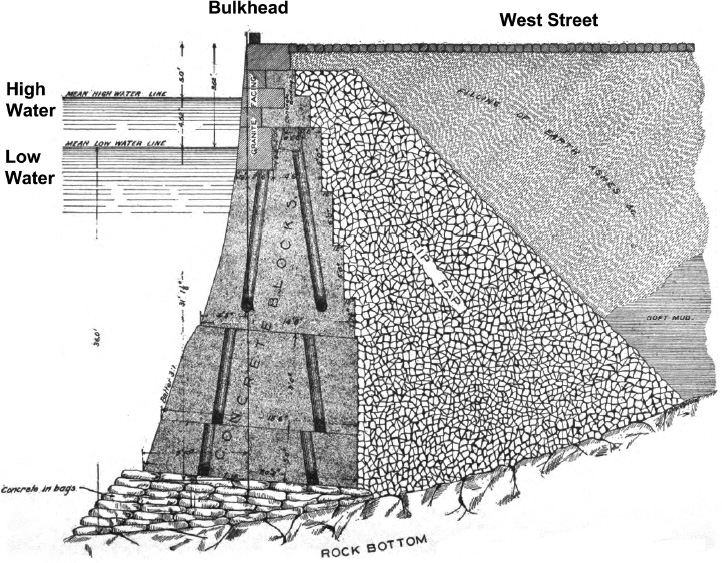

The Department of Docks eventually bought back 17.8 miles of Manhattan’s waterfront and created a new shoreline. The department first undertook a detailed study of the existing bulkheads, using underwater surveys and borings to determine how far below solid rock lay. Conditions varied, and the engineers utilized a number of designs for the new bulkhead. To lower the cost, the engineers used pre-cast concrete blocks below the water line and capped the last 10 feet with granite blocks. With the bulkhead in place, new piers replaced the rotten, dilapidated piers that threated to destroy the city’s maritime commerce. Today, thousands of people enjoy the new Hudson River Park’s pedestrian walkway, on the river’s edge, that sits atop the granite-capped bulkhead built over 100 years ago.

A typical section of the bulkhead measured 36 feet in depth at low water. The granite and pre-cast concrete blocks rested on bedrock. Behind the new bulkhead, stone riprap fill created a solid foundation for the newly widened West and South Streets (fig. 7.1). The department set up construction yards along the Hudson River at Gansevoort Street, and on the East River at East 17th Street, to build the cast concrete blocks, using molds to speed production. The concrete blocks were then loaded onto barges and towed to the section under construction. Dredges removed the debris and muck down to the bedrock, and divers, using primitive equipment, arranged concrete bags to provide a solid foundation for the first layer of cast blocks.

Figure 7.1. Schema for one of the Department of Docks’ new bulkheads. These uniform bulkheads stabilized the Manhattan shoreline and provided a foundation for the widened South and West Streets. The bulkheads were used by the railroad’s car floats and smaller ships. The newly created parks, walkways, and bike paths on the Manhattan shoreline today rest on these bulkheads, constructed at great cost by the Department of Docks more than 100 years ago. Source: Sidney Hoag Jr., “The Dock Department and the New York Docks,” paper no. 16, presented March 22, 1905, Municipal Engineers of the City of New York, Proceedings for 1905, plate 36

The heavy cast concrete blocks and granite caps needed to be moved and carefully fitted. This was done with the assistance of a giant floating derrick to lift the blocks, which weighed between 25 and 45 tons each.9 The derrick, named the “City of New York,” could hoist 100 tons. It became a familiar sight, symbolizing the rebuilding of the waterfront (fig. 7.2).

Figure 7.2. The “City of New York,” a 100-ton floating derrick, lifting a pre-cast concrete bulkhead block. This innovation, the largest floating derrick in the world, allowed the Department of Docks to use such blocks to build the new bulkheads. Multiple concrete blocks could be quickly poured in construction yards on the waterfront. The blocks were loaded onto barges and towed to the section of the shoreline under construction, where they were lowered into place by the derrick. Source: Sidney Hoag Jr., “The Dock Department and the New York Docks,” paper no. 16, presented March 22, 1905, Municipal Engineers of the City of New York, Proceedings for 1905, plate 21

When the Department of Docks was first organized in 1870, it contracted out the construction of the new bulkheads and piers. Difficulties with the contractors arose, however, and by 1880, the department hired its own workforce. Tammany Hall supported the change and used its political muscle to ensure that the new labor force included many of its loyalists. Scandal followed, as critics charged that the new workers had to pay kickbacks to Tammany to secure a job. The whiff of corruption lingered, but after initial difficulties, the department pushed ahead. For the next twenty plus years, work continued. Each year the engineer-in-chief submitted details of all construction activity. The 1903 report listed the completion of 7.8 miles (30,575 feet) of new bulkhead; 214 piers, with a total of 7.6 million square feet of space; and the grading and paving of 265,700 square feet of the widened West and South Streets.10 The department had completely rebuilt the waterfront around the southern portion of Manhattan Island, creating modern facilities to sustain the city’s maritime commerce.

Revenue from both the new dock and ferry leases and from wharfage increased dramatically. This totaled $460,164 in 1871 and, with the leasing of the new bulkhead and piers, reached $2,775,172 in 1900, an increase of slightly over 500 percent. In most years, revenue exceeded expenses, generating a surplus. The Department of Docks not only met the legal requirement to be self-financing, but it also sent a significant amount of surplus funds to the city of New York to reduce the general debt, as the 1871 charter required.11 The increased revenue covered the cost of building longer and more-modern piers along the Hudson River. By the turn of the century, the Department of Docks had spent over $11 million to repurchase the Manhattan waterfront, enabling the construction of a new, modern, maritime infrastructure.12

The success of the Department of Docks served the interests of Tammany Hall. As the rebuilding of the port’s infrastructure expanded, the department’s payroll became a source of patronage for the Democratic machine, dominated by Irish politicians. James Fisher, in his masterful work, On the Irish Waterfront, characterizes the department’s payroll as a “patronage windfall.”13

The department’s 1887 annual report included five pages of small print listing all of the employees and either their salaries or their hourly wages. Engineer-in-Chief George S. Greene earned an annual salary of $6,000, while ninety-one laborers earned 23 cents per hour: from approximately $9 to up to $12 a week for 40–50 hours on the docks. These workers included Thomas Ahearn, Peter Burke, James Kennedy, John McSorley, John Murphy, and Thomas Sullivan.14 Securing a job at the Department of Docks required the support of Tammany Hall. On the Irish waterfront, employment required a note or a word from the local ward boss. Tammany expected the higher-paid salaried workers to hand over 5 or 10 percent of their income as a “donation” to the machine.

Tammany corruption was pervasive in the Department of Docks. In addition to jobs, the Democratic machine also expected that the major contracts awarded by the department for building piers, dredging, and supplying construction materials would go to the politically connected. In 1884, the Union Dredging Company, which had strong ties to Tammany Hall, was paid $111,509, over 25 percent of the entire construction account for that year. Charges of corruption in the Department of Docks led to a series of investigations, which charged that Union Dredging submitted bids with no price filled in. The department’s treasurer then wrote in a price, at slightly less than the lowest bidder. J. Sergeant Cram, an ex-commissioner of the Department of Docks who served in the mid-1880s, admitted that “Tammany men always had the preference, other things being equal.”15

A decade later, with the corruption and influence of Tammany on the city’s government continuing, the New York State Assembly appointed a special committee in 1894 to investigate the “offices and departments of the city of New York.” Chaired by Robert Mazet, a Republican assemblyman, the committee began conducting hearings.16 In August 1899, the committee called Charles F. Murphy, treasurer of the Department of Docks, to testify. The investigator asked Murphy to explain why seventeen dredging jobs were given to one company without competitive bidding, all on “treasurer’s orders.”17 These contracts went to the Morris & Cummings Company, whose president, George Leary, served as a high-ranking officer in Tammany Hall. Morris & Cummings bought all the piles for the new piers from Naughton & Company, owned by Daniel Naughton, a “Tammany leader,” according to the New York Times. Political connections obviously ruled the department. As Murphy’s testimony before the committee admitted, “he paid a good deal of attention to the patronage of the department. The men were mostly sent to him by [Tammany] district leaders he said. . . . He said he looked on that as a proper way of selecting appointees and a legitimate method of rewarding proper party service.”18

The influential New York Chamber of Commerce also publically criticized the department’s overall management of the waterfront in its annual report for 1896, listing “certain ills”:

1. An absolute lack of proper wharves and docks.

2. A most exorbitant charge for the use of the piers that do exist.

3. Steamship lines are also compelled to pay for the dredging of the docks.19

A. Foster Higgins, chair of the chamber’s Committee on the Harbor and Shipping of New York, demanded that the city of New York close the Department of Docks and turn the piers back to private companies.20 Higgins’s argument, however, ignored the waterfront’s history. Private interests, which had dominated the Manhattan waterfront from the colonial era to the middle of the nineteenth century, had completely failed to keep pace with the ever-increasing maritime commerce of the port. Despite the corruption, the comparative success of the Department of Docks proved that only a public enterprise, responsible for the entire waterfront, could marshal the financial resources and political will to improve the port’s infrastructure.

Nonetheless, the Chamber of Commerce did correctly identify one of the most serious problems on the rebuilt waterfront: the intense competition for space among the major users of the port. Of the 13,439 feet of space on the Hudson waterfront from the Battery to Gansevoort Street, foreign steamship lines occupied only 1,779 feet (13.2%) and coastal shipping, 1,861 feet (13.9%). The railroads took up more space than either of these two major shipping businesses combined: 3,883 feet (28.9%).21 Without the ability to bring freight back and forth to Manhattan, they could not compete with the only railroad with direct access to the island: their bitter rival, the New York Central.

Despite the legislative investigations into political corruption and criticism from the city’s chamber of commerce, at the beginning of the new century, the future looked bright for the port, the Department of Docks, and the port’s maritime commerce. New York reigned as the busiest port in the world, with—in terms of both imports and exports—no serious American rival. The city also remained the leading manufacturing center in the country, and its population continued to grow. In 1898, Manhattan and the four outer boroughs—Brooklyn, the Bronx, Queens, and Staten Island—merged to form greater New York City, the most populous place in the United States. Across the river in New Jersey, the cities along the Hudson River also prospered as their maritime and railroad-based commercial activity increased. The Port of New York now encompassed not just the Manhattan waterfront, but over 650 miles of shorefront in the bi-state metropolitan region, seemingly enough shoreline to meet the demands of the twentieth century.22

During its first two decades, the Department of Docks devoted a great deal of energy to building the bulkhead around the lower part of Manhattan Island, acquiring the decrepit docks owned by the water-lot grantees, and constructing modern piers. All were major accomplishments, but a serious problem remained: the ever-increasing size of ships, especially the British transatlantic steamships that necessitated longer piers.

The Montgomerie Charter granted control of the waters around Manhattan Island out to 400 feet beyond the low-water line to the city of New York. Well into the nineteenth century, piers built out into the East and Hudson Rivers did not extend that far. As the dimensions of ships increased, however, piers on the East River could not be lengthened, since the construction of new, longer piers could be accommodated only along the Hudson River, where a mile of water separated the Manhattan shoreline from New Jersey. In 1856, New York State had asserted its legal control of all waters beyond the 400-foot mark. At that point, the state’s New York Harbor Commission established permanent pier lines around the entire island, beyond which no piers could be built. To further complicate the issue, in 1890 the US Congress passed legislation preempting the State of New York’s control of the waterways in the port and delegated responsibility to the US Army Corps of Engineers. Now, all plans to build beyond the newly established pier line required permission from the Corps of Engineers, representing the federal government. The government wanted no interference in the waterways around the country, in order to allow US Navy ships to maneuver.

With increasing numbers of transatlantic steamships coming to the port, the Department of Docks desperately needed to build longer piers that extended beyond the established pier line. The department petitioned for exemptions, and the Army’s Corps of Engineers refused the request. Only one solution proved to be feasible. Since piers could not extend farther out into the Hudson River, the Department would have to repurchase the made-land on the waterfront in Greenwich Village and, later, in Chelsea; excavate; and move the bulkhead 200 feet back toward Manhattan’s original shoreline! Here the repurchase included not just the bulkhead, but the actual made-land created by filling in the water-lots a century earlier. Without the longer piers, the transatlantic steamship companies would have to abandon the Port of New York.

The construction of the longer piers required an enormous expenditure, one beyond the capability of the private pier owners. Only a public agency, with the ability to issue bonds, could undertake a project on this scale. The Department of Docks, as part of the New York City government, could use eminent domain to acquire the made-land along the Hudson River from its private owners. As in Liverpool, the department would undertake a giant public construction project to build an absolutely crucial addition to the port’s infrastructure. In 1880, G. S. Greene, the Department of Docks’ engineer-in-chief, presented a bold plan to redevelop the entire waterfront between Christopher and West 18th Streets, a distance of 4,430 feet, more than three-quarters of a mile. The plan included removing six city blocks: 13th Avenue and “all buildings, piers, earth and mud, west of this 250-foot street [West Street] to the depth of 25 feet below mean low water mark.”23

Greene estimated the total cost—including purchasing the property; excavating 1,860,000 cubic yards of fill; and constructing twenty-one new piers—at $7.5 million. He expected the work to be completed in about eight years, but instead, twenty years of negotiations and court proceedings ensued. The land and buildings on just the six blocks between West 11th and Gansevoort Streets cost slightly over $5.9 million. This sum represented 79 percent of the original projected cost of the entire proposed project, an estimate that had included both the cost of land and construction of twenty-one piers.24 Real estate development in the City of New York has always been contentious, as the Department of Docks learned in the 1880s and as it remains today.

Map 7.3 illustrates the redevelopment of the waterfront between West 11th and Gansevoort Streets in Greenwich Village, superimposed on the six blocks that were removed. One street (13th Avenue) disappeared, as did the made-land between it and West Street. To acquire the needed made-land, the department repeatedly had to go to court to force the private owners to sell their land and buildings. Part of the extraordinary increase in cost resulted from the department’s decision to once again begin the demolition of existing buildings and then excavate before the courts determined the final cost. The Department of Docks argued that if it waited for the final judgments, the project would never have been completed in a reasonable period of time.

Map 7.3. Hudson River water-lots and the Department of Docks’ pier, bulkhead, and made-land repurchase in Greenwich Village, from West 11th Street to Gansevoort Street. The Department of Docks repurchased six city blocks between 13th Avenue and West Street; cleared and excavated the land; let the Hudson River flood the area; and then built new, longer piers from West Street out into the river, eliminating 13th Avenue. Source: Created by Kurt Schlichting. Source GIS layer: historic street and pier maps, New York Public Library, Map Warper.

In the end, Greene’s plan resulted in five new piers, which the Department of Docks leased to the major transatlantic steamship companies for steep fees. The British companies had no choice, since the new Greenwich Village docks provided the only piers on the entire Manhattan waterfront that could accommodate their large passenger ships. Moreover, all costs for maintenance and dredging remained the responsibility of the steamship companies, who negotiated leases for the docks. To stay competitive, all the British steamship companies needed to remain on the Manhattan waterfront. Talk of moving across the Hudson River to the waterfront in Jersey City or Hoboken remained just talk. Even though officials in both of these cities offered incentives, the companies knew that their passengers did not want to end a luxurious Atlantic crossing on the other side of the river, a ferryboat ride away from their ultimate destination: Manhattan.

All of the major transatlantic lines anticipated a prosperous future carrying passengers and high-value freight across the Atlantic Ocean to New York. With long-term leases, the companies ensured their access to the waterfront.25 For New York City, the lucrative leases for the new piers testified to the value of the rebuilt waterfront and the modernized maritime infrastructure built by the Department of Docks. The department’s annual report for 1905 triumphantly pointed out that the new leases for the Greenwich Village piers would not only pay back the cost of construction, but also the bonds, as well as generate a surplus.

When the Department of Docks first proposed the Hudson River pier improvements, the plans included the Chelsea waterfront north of Gansevoort Street, from West 14th to West 30th Streets. Costs and delays postponed this work until after the completion of the new piers in Greenwich Village. Relentless technological innovations in ship design—in particular, the new, powerful steam turbines—and the fierce competition among the transatlantic lines led to the construction of larger and more luxurious ships. The planned Titanic and Lusitania measured over 800 feet long, and with still-bigger ships on the drawing boards, the new Chelsea piers needed to exceed these lengths. Even with the completion of the Greenwich Village piers, a number of the transatlantic shipping companies that had not obtained leases sent applications for new piers to the Department of Docks. In 1898, the president of the board, J. Sergeant Cram, argued for the addition of new piers in Chelsea. He contended that new piers would “cost $12,000,000, but not one cent would they cost the people of this city. We can rent them readily for sums that would realize 5 per cent on their cost.”26 Cram continued by emphasizing that with the city able to sell bonds at 3 percent, the new piers would pay for themselves and could be constructed in two years.

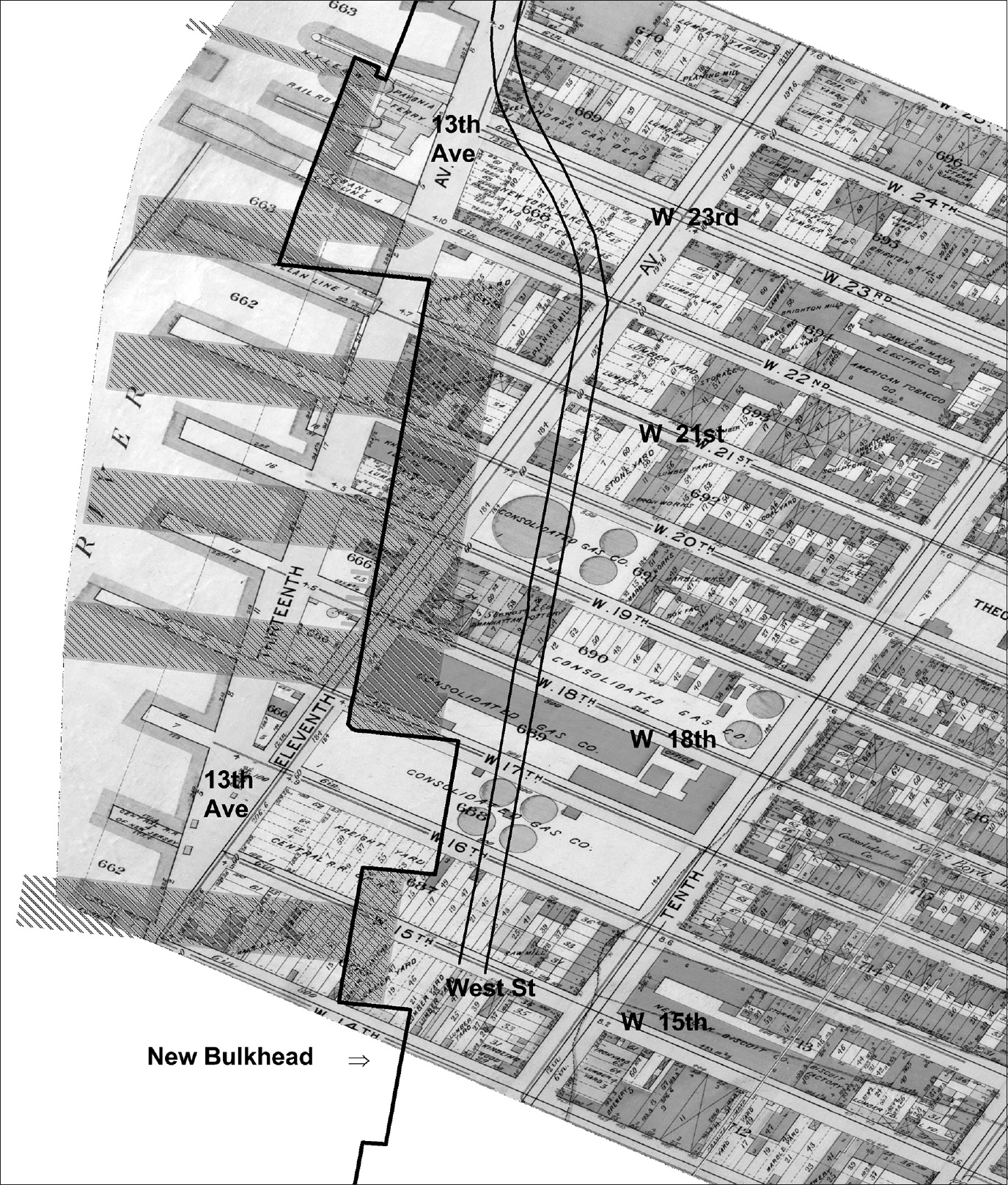

The proposed longer piers would extend beyond the established pier line in the Hudson River, and the Department of Docks again appealed to the Army Corps of Engineers to build 200 feet past that line. Once more, the appeal failed, and only one course of action remained. Just as with the new piers in Greenwich Village, the department would undertake the expensive and time-consuming process of repurchasing the inland water-lots and moving the bulkhead back toward the original shoreline. The department began the legal process of buying back the made-land between West 14th and West 23rd Streets owned by Clement C. Moore, the General Theological Seminary, and other grantees (see map 2.4). Given the difficulties and delays encountered earlier, the condemnation of these properties proceeded more quickly, but not inexpensively. The price for acquiring this land almost equaled Cram’s optimistic estimate for the cost of the entire project. Between 1871 and 1920, the Department spent $42.6 million acquiring the bulkhead around the lower part of Manhattan Island and repurchasing water-lots. The Chelsea pier acquisitions alone accounted for a quarter of the total expenditure.

Construction of the new piers began in 1895 and continued for the next decade, completely transforming the Chelsea waterfront (map 7.4). At 16th Street, the new bulkhead stood 560 feet inland from the old bulkhead along 13th Avenue, an avenue that disappeared. To the north, at West 21st Street, the project extended the bulkhead past 13th Avenue and into the Hudson River. A new, wide extension of West Street in front of the new piers created open space that heightened the impact of the new piers’ architecture.

Map 7.4. The Chelsea piers were another massive and costly project. Once again, the Department of Docks purchased entire city blocks, excavated, and moved the new bulkhead back toward the original Manhattan shoreline. West Street was also relocated, and 1,000-foot piers were built out into the Hudson River. Source: Created by Kurt Schlichting. Source GIS layers: historic street and pier maps, New York Public Library, Map Warper; Chelsea piers map, New York City Planning Department.

Figure 7.3. The Chelsea piers, circa 1912. These new piers were the longest in the port and could accommodate luxurious ocean liners over 1,000 feet in length. Source: Shorpy Inc. / Vintagraph / Juniper Gallery.

Since the new piers served the luxury transatlantic passenger service, the Department of Docks engaged Whitney Warren, the architect for the new Grand Central Terminal, to design an elaborate façade along West Street. Warren employed the Beaux-Arts style to introduce a sense of grandeur. Previously, a typical pier shed included a utilitarian façade, adorned with garish lettering advertising the name of the railroad or shipping company. Warren’s ornate portico faced the widened new section of West Street, embellishing the pink granite façade with ornamental figures decorating the cornice (fig. 7.3).

As work progressed, the New York Times hailed the new piers as “one of the most remarkable water-fronts in the history of municipal improvements . . . converting an extensive section of Manhattan’s Hudson River waterfront into the most colossal steamship terminal.” The Times praised the new piers’ magnificent architecture, “so imposing that the foreign visitor will no longer find false impressions of the great city—no tawdriness in the way of piers.”27 The Chelsea piers created a new streetscape, bringing the City Beautiful Movement to New York’s waterfront. Warren’s Grand Central Terminal (1913), Carrere and Hastings’s New York Public Library (1907), the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 5th Avenue façade (1902), and Pennsylvania Station (1910) all celebrated the rise of New York to a world-class city. Now transatlantic passengers would use the new Chelsea piers as the city’s magnificent gateway to the Atlantic World. At Warren’s Grand Central Station, the main concourse provided an even more-elaborate gateway for passengers arriving by train.

On February 21, 1910, the Chelsea piers officially opened when the White Star Line’s Oceanic berthed at Pier 60. The major transatlantic passenger lines now moved to these nine new piers.28 To cover the cost of the new piers ($4,505,540) and the purchase of the relevant water-lots, the Department of Docks negotiated long-term leases for a ten-year period, renewable for two more ten-year periods, extending from 1910 to 1940.29 The steamship lines all believed the future of transatlantic passenger service to be boundless, and they planned to continue using the piers for the next several decades. Another challenge for the port arose when these steamship companies announced plans for even larger ships, with the White Star Line’s new Oceanic to be over 1,000 feet in length. Once again, the department would have to build new, longer piers farther up the Hudson River, at Midtown.

With the Department of Docks’ rebuilding of the Manhattan waterfront, both shipping and railroad freight traffic to the port continued to grow, especially along the Irish waterfront in Greenwich Village and Chelsea. In the decade and a half before World War I, the number of arriving and departing ships dealing in international commerce increased from 8,178 in 1907 to 10,580 in 1916.30 A half century earlier, in 1860, the number of ships handling foreign commerce had totaled 3,960.31 At the turn of the twentieth century, 50 percent of the total exports and imports for the entire United States moved through the Port of New York.

The number of ships in international service consisted of only a modest share of the vessels arriving and departing in the port. Yearly, thousands of coastal ships and smaller boats arrived via the port’s waterway empires. In addition to shipping, the volume of freight handled in the port by the railroads reached a staggering 76 million tons in 1914.32 With 20 million tons of this total inbound for Manhattan, New York Central freight cars carried almost 3 million tons directly onto Manhattan Island. The New Jersey–based railroads handled the remaining 17 million tons in their rail yards on the New Jersey side of the harbor and then floated the freight across the Hudson River to the Manhattan waterfront. Once on the New York side, the freight had to be landed at the freight terminals and then either hauled by drays and trucks to final destinations in Manhattan or carted to a pier, where longshoremen loaded a waiting ship.

Even after the grand opening of the Chelsea piers, a series of systemic problems remained. Crowding along the shoreline did not lessen, and corruption, crime, and labor unrest persisted on the docks and in the surrounding neighborhoods where the longshoremen lived. By 1900, Manhattan no longer handled all of the ships and cargo arriving in the Port of New York. The Brooklyn and Staten Island waterfronts expanded. Across the Hudson, new piers were built in Jersey City and Hoboken, and some shipping companies relocated to the Jersey shore. That state’s politicians and business leaders were more than delighted for the railroads to handle more freight on the New Jersey side of the harbor. The railroads thus saved the added cost of moving freight the “final mile” across the Hudson River to ships docked in Manhattan.

By the dawn of the twentieth century, the Port of New York included more than just the waterfront on Manhattan Island. Piers lined the Queens shore along the East River, as well as the shores of Brooklyn, Staten Island, Newark Bay, and the New Jersey waterfront cities of Bayonne, Jersey City, Hoboken, and Weehawken. A sprawling bi-state region evolved, encompassing numerous local governments. It included the largest city in the country, New York, and one of the smallest, Hoboken’s 1 square mile. The multiple local governments each pursued their own agendas and sought to maximize their gains.

The Department of Docks viewed the cities across the Hudson River as rivals for the port’s maritime business. The eight railroads in New Jersey vigorously complained about the cost advantage the New York Central enjoyed, with its direct rail service onto Manhattan Island. The US Interstate Commerce Commission, however, continued to prohibit the New Jersey–based railroads from adding additional freight costs for hauling goods across the Hudson. Thus a manufacturing company in Manhattan paid the same rate to have freight delivered by the New Jersey railroads as by the New York Central.

In additional to the fight over freight rates, New York State and New Jersey clashed over plans to build longer piers out into the Hudson River, and both states had conflicts with the Corps of Engineers, which was concerned about the Hudson remaining navigable for large ships. New Jersey politicians, from the governor to mayors, resented the dominance of New York City in the Port of New York. No one political entity or interest group, however, exercised administrative oversight or coordinated development for the entire bi-state port.

William J. Wilgus, the New York Central Railroad’s chief engineer, who planned the massive Grand Central project, realized that the transportation challenges in the port involved more than the railroads. The fragmentation of political and regulatory power in the region stymied all efforts to improve the maritime and railroad infrastructure throughout the port, in order to accommodate the ever-increasing number of ships and volume of freight. In 1909, he proposed the creation of an interstate metropolitan district, which would include all of the cities, towns, and villages in the bi-state region surrounding the Port of New York.33 This district would form a quasi-governmental metropolitan agency, with delegated power from both New York State and New Jersey, to plan necessary improvements and exercise regulatory control over the entire port. Transportation experts in both railroads and shipping would lead the needed rational process to maintain the port as the busiest and most important in the country.

Almost all of the major interests in the port opposed Wilgus’s plan. Each viewed any effort to change the status quo as a threat to its own parochial benefits. All of the railroads in New Jersey operated their own tugboats, lighters, and car floats, at great expense. New York City’s Department of Docks worried that any efforts to coordinate with New Jersey would result in a loss of revenue from the wharves and piers in the city. The mayor and the City Council—and, behind the scenes, Tammany Hall, the longshoremen’s union, and the mobsters who now controlled the piers—all saw the proposed district as a threat to patronage-based waterfront jobs and the spoils from graft and corruption on the docks. While Wilgus’s plan received some support in both the New York State and the New Jersey legislatures, the strong political and business opposition to it could not be overcome.34

World War I created enormous pressure, leading to massive congestion, thus stymieing the movement of freight through the Port of New York. Soon after the United States entered the war on April 6, 1917, planning got underway to transport and supply the American Expeditionary Force (AEF). The AEF would ship out from New York, and supplies would follow. Troop strength was projected to reach 2 million by December 1918, and that number of soldiers would need 52,000 tons of supplies each day, all to be shipped across the Atlantic Ocean.35

By 1917, the demands on the country’s railroads and the Port of New York in supplying the troops led to an almost complete breakdown of the transportation system. The inefficient means of moving freight across the Hudson River to ships bound for Europe could not meet the demand, and thousands of tons of freight piled up on the piers throughout the harbor. With the port paralyzed, trains bound for New York backed up all the way to Chicago, creating a serious shortage of freight cars. In December 1917, President Woodrow Wilson nationalized the railroads and appointed William McAdoo, a talented railroad executive who completed the Hudson & Manhattan Railroad passenger tunnels under the Hudson (today’s PATH rapid transit system tunnels), as head of the US Railroad Administration. With his direct control over all of the railroads and shipping companies serving the Port of New York, McAdoo soon solved the freight crisis. His efforts treated the entire bi-state port as one integrated system, which was administered by one set of executives, not by eleven separate railroads in New Jersey and New York, the Department of Docks, or the myriad shipping firms.

In the war’s aftermath, the idea for a metropolitan port district resurfaced. The success of McAdoo and the US Railroad Administration encouraged Wilgus and others to return to arguing for a metropolitan agency. The Russell Sage Foundation provided support for a regional planning model and, in 1922, established the Committee on the Regional Plan of New York and Its Environs. After seven years of research, the committee published its plan. It also established the Regional Plan Association, an organization to support regional planning.36

On the political front, in 1919, New York State and New Jersey, responding to pressure from the New York Chamber of Commerce and others, passed legislation to form the joint New York New Jersey Port and Harbor Development Commission. The commission’s charge included undertaking a detailed study of the then current transportation problems in the port and making recommendations for change. One basic premise underpinned the study: McAdoo had succeeded in the earlier freight crisis because he had the power to regulate transportation in the entire port and region. Any solution to the intertwined transportation challenges had to embrace not just the Manhattan waterfront, but a bi-state metropolitan region that extended for a 50-mile radius around Times Square. By the 1920 US census, this region was home to over 8.1 million people.

A metropolitan region—crossing the long-established political boundaries of state, city, and local governments—represented a new conceptualization of the port, the city of New York, and the surrounding counties in New York State and New Jersey. In the larger region, New York City and Manhattan Island continued to play a leading role, but the continued prosperity and commercial success of the port depended on a complicated relationship with the surrounding areas. Each depended on the other. When the commission published its detailed Joint Report with Comprehensive Plans and Recommendations in 1920, the key recommendation called for the formation of a bi-state authority to manage both the Port of New York and all rail and shipping, in order to benefit the entire region.37 In 1921, New York State and New Jersey passed legislation creating a new political entity: an “authority,” the first with that title in the United States. The two states, in establishing the Port of New York Authority, anticipated that professional management, a rational planning process, and “better coordination of the terminal, transportation and other facilities of commerce in, about and through the Port of New York, will result in greater economies, benefiting the nation, as well as the states of New York and New Jersey.”38

The new authority had a defined public purpose: to improve transportation in the Port of New York area. To accomplish this public good, the two states delegated to this new entity power to do what an elected local government usually did: borrow money and build public infrastructure. What set the authority apart was that the commissioners who ran the organization were appointed by the two governors, rather than being elected or chosen by local elected officials. The creation of the Port Authority was not without its issues, however. What oversight would the mayor of New York or the mayor of Jersey City or any other local elected official exercise? If the new Port Authority decided to relocate some of the shipping and freight handling from the Manhattan shorefront to the other side of the Hudson River, did it have that power? And if the Port Authority did, what would be the consequences? Serious questions regarding the power of independent public authorities—a mixture of public/private power—remain to this day.

Within a few years, the Port Authority’s vision expanded to encompass all forms of transportation in the metropolitan region, especially the new revolution created by the advent of automobiles, trucks, and airplanes. Jameson Doig’s masterful study tracks the expansion of the Authority’s reach, creating an “empire on the Hudson” far beyond the intent of the original legislation.39 The Port Authority gained control over the Holland Tunnel, the first vehicular tunnel under the Hudson River, in 1930. Traffic through the new tunnel exceeded projections, beginning from the first day it opened, and generated more than enough revenue to pay the construction bonds. In turn, the Authority used the surplus to fund other bridge and tunnel projects. The Port Authority also took over Newark Airport in New Jersey, plus LaGuardia and Idlewild Airports in Queens. When the Authority negotiated to take over Newark’s municipally owned airport, the final agreement included that city’s dilapidated piers on Newark Bay.

Beginning in 1927, the Port Authority expanded the transportation infrastructure throughout the metropolitan region. Conspicuous by their absence, however, are major improvements in rail facilities and the maritime infrastructure.40 During the Great Depression, the decline in shipping led to fiscal difficulties for the Department of Docks. The Port Authority offered to buy all of the piers in Manhattan and Brooklyn and invest in modernization. A political firestorm erupted, so the Port Authority turned away from that proposal and increased its efforts to expand the automobile and truck infrastructure. In the next decades, the Authority built bridges, tunnels, and trucking terminals and expanded the region’s four airports.

The Port Authority would not return its attention to the region’s maritime infrastructure until 1962, and then it focused all of its energy and investment in Newark Bay and the waterfront in Newark and Elizabeth, New Jersey. With the container revolution underway, the Port Authority orchestrated the shift of the Port of New York from the Manhattan and Brooklyn waterfronts across the harbor to Newark Bay. The Port Authority’s infrastructure projects from 1927 to 1973 included:

• Holland Tunnel, 1927 (the Port Authority took over operations in 1930)

• Goethals Bridge, 1928

• Outerbridge Crossing, 1928

• George Washington Bridge, 1931

• Bayonne Bridge, 1931

• Inland Terminal No. 1, 1932

• Lincoln Tunnel, south tube, 1937

• Grain Terminal and Columbia Street Pier, Brooklyn, 1944

• Lincoln Tunnel, second tube, 1945

• Newark Airport and Port Newark, 1947 (acquired under lease from the city of Newark)

• LaGuardia and Idlewild (now Kennedy) Airports, 1947 (acquired under lease from the city of New York)

• Teterboro Airport, 1948

• New York Truck Terminal, 1949

• Newark Truck Terminal, 1950

• Lincoln Tunnel, third tube, 1957

• Elizabeth, New Jersey, Port Authority Marine Terminal, 1962

• World Trade Center, 1973

This exodus of the maritime world to New Jersey would lead to cataclysmic change along the Manhattan waterfront.