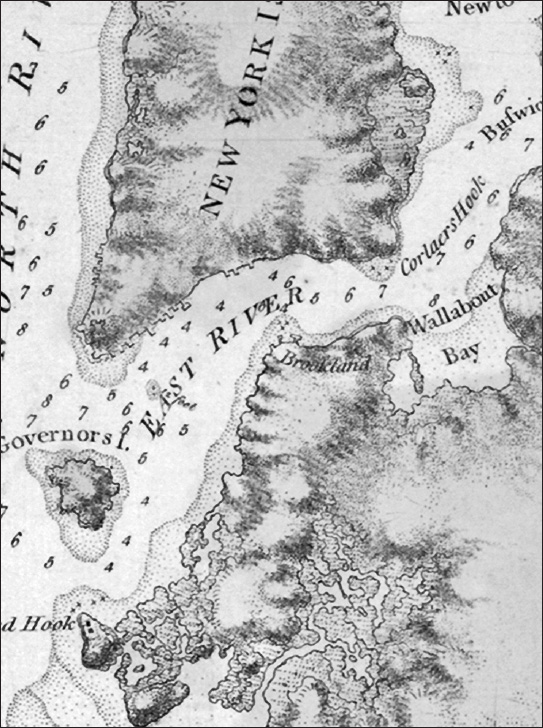

For 350 years, New York Harbor and Manhattan Island prospered in a maritime world. Across the shorefront of the island—the boundary between water and land—the trade, shipping, and commerce of the country passed, ensuring the city’s prosperity (fig. 2.1).

From the beginning, control of the harbor and Manhattan’s waterfront—the region’s magnificent geographical resource—has always been contentious. Colonial governments had limited fiscal resources, and the need to build wharves and piers provided a serious challenge. If the city of New York were to compete with other colonial seaports, did its government have the primary responsibility to construct and maintain the essential maritime waterfront? If not, and private interests and private capital instead built the wharves and piers, what role would the city’s government play? Were private interests and the public good the same on the waterfront? Would limited government oversight ensure the proper development of the port by private interests?

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the European settlement of North America created an Atlantic World.1 Three thousand miles of ocean separated Europe from the Atlantic seaboard. The voyage across the North Atlantic from Europe to America, traveling east to west, is one of the most difficult ocean passages in the world. Prevailing winds in the North Atlantic blow from the west, and in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries, sailing ships struggled against them, especially in winter, when the westerly gales blow. In US Navy Lieut. Matthew Fontaine Maury’s Explorations and Sailing Directions, published in 1851, his wind and current data for the North Atlantic warned mariners sailing west from Europe to America to expect adverse winds in January, February, and March more than 50 percent of the time.2

Figure 2.1. Manhattan’s waterfront infrastructure, circa the 1930s. Piers line both the Hudson River shoreline (extending from the Battery to Riverside Park and West 125th Street in Harlem) and the East River shoreline (extending from the Battery to Corlears Hook, and Grand Street to East 14th Street, Stuyvesant Cove, and East 23rd Street). Source: New York City Municipal Archives

The Mayflower left England on September 6, 1620, and arrived off the coast of Cape Cod in Massachusetts on November 9, a voyage of sixty-four days. Two hundred years later, crossings by the crack Black Ball Line packet ships, sailing from Liverpool to New York (1818–1853), averaged over thirty days in the winter, and some of their voyages lasted for sixty or even seventy days.3 Sailing ships carrying immigrants took seven or eight weeks to reach New York. Sometimes they ran low on water and food, and many died en route. In our modern world, when the Atlantic Ocean can be crossed in hours by air, it is nearly impossible to imagine weeks aboard a sailing ship in winter, with snow and freezing conditions in the middle of the North Atlantic.

While the ocean voyages were extremely dangerous at times, the goal was not simply to cross the Atlantic Ocean, but to also find a way to come ashore. To reach solid ground, explorers and settlers needed to find a safe harbor. All of the early colonial cities—Boston, Newport, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Charleston—grew around inlets, rivers, and bays that provided sheltered access to the land. Besides a protected harbor, a deep anchorage, close to a gently sloping shoreline, facilitated the transfer of people and cargo from ship to shore.

Each of New York’s rival colonial seaports offered some of the same geographical characteristics, so Manhattan’s rise to a position of commercial ascendancy required more than just the advantages nature provided. Robert Albion, in his groundbreaking The Rise of New York Port, points to those advantages but also adds a crucial ingredient—the drive and ambition of the merchant class who led New York to a position of dominance: “Nature can do a good deal, but not everything, to determine the success of a seaport. Human initiative also accounts for something. . . . Geographical considerations were all important in the story of New York port. . . . At no other spot on the North Atlantic coast was there such a splendid harbor. . . . Yet even New York trailed behind less favored rivals until local initiative [author’s emphasis] finally took full advantage of nature’s bounty.”4 Albion includes a chapter on the “Merchant Princes” that provided New York with the necessary local initiative. This initiative, however, involved more than just the city. New York State, led by its hard-driving governor, DeWitt Clinton, risked millions of dollars in state funds to construct the longest canal in the world. The Erie Canal created an inland waterway between the Port of New York and a vast maritime hinterland, stretching to the Midwest.5

One hundred miles to the east, Newport, Rhode Island, at the mouth of Narragansett Bay, provides a deep, secure anchorage just a few miles from the ocean. Moreover, Newport harbor is closer to the Atlantic Ocean than Manhattan Island. A British piloting guide, published in 1734, included a detailed map of the New England coast from Rhode Island to New York and warned captains not to sail above 40º north latitude. Crossing the Atlantic, a sailing ship arriving at 40º north latitude could find a protected harbor in either New York or in Newport (see map 4.1). For a brief period of time, Newport rivaled Boston and New York as a center of colonial maritime commerce. The British occupied both Newport and New York during the American Revolution, along with Boston, Baltimore, and Philadelphia. Their occupation of New York lasted seven long years, from 1776 until 1783, and during that period, early in 1776, the Great Fire destroyed an estimated 25 percent of the buildings in the city. New York recovered quickly, however, and soon become the commercial center of the new country. Newport never recovered its colonial status as a preeminent port, although the other rival seaports—Boston, Baltimore, and Philadelphia—did not meekly surrender to New York’s maritime ascendency. The merchants and shipowners in these cities were as ambitious as those in New York.

The Dutch chose Manhattan Island because of its superb geography, combined with access, via the Hudson River, to Albany, 140 miles to the north, which was the center of the North American fur trade. They established an all-important trading post in Albany, but they decided to build New Amsterdam on the lower tip of Manhattan Island, where the Upper Bay, just to the south of the island, forms one of the great natural harbors in the world. Once through the Narrows, which separates Brooklyn from Staten Island, ships are protected and find safe anchorage (see map 1.1). Albion describes its advantages: “New York possessed a landlocked harbor, which offered more perfect natural shelter than that of any other major American port as close to the sea. A century ago, a prominent engineer remarked that even if the sandy mass of Long Island might have no other use, it justified itself as a natural breakwater for New York. Staten Island served similar purposes. . . . Shipping in the Lower Bay or the Narrows might catch the force of a gale, but the waters around Manhattan were spared the surges of stormy seas.”6 The Battery, at the tip of Manhattan Island, is a short 16 nautical miles from the ocean. By comparison, Philadelphia is 88 miles up Delaware Bay, and Baltimore is 150 nautical miles, via Chesapeake Bay, from the Atlantic Ocean.

The Upper Bay forms a wide estuary leading to Manhattan Island, which is surrounded by the Hudson River to the west and the East River to the east. A 1779 British naval chart of the Upper Bay shows the depth of water at low tide along the Hudson and East Rivers, just offshore around Lower Manhattan (map 2.1). Close to the shoreline, the East River’s depth reaches 4 fathoms, or 24 feet, at low water. Another decided advantage to the harbor, which is actually a tidal estuary, is the minimal rise and fall of the tides, which average 4.5 feet. The deck of a ship tied to a pier along these rivers would be just 4 feet lower at the lowest point of the tide. Liverpool, an important British port located on the Mersey River, which flows into the Irish Sea and then the Atlantic Ocean, faces entirely different—and difficult—tidal conditions. Tides there rise and fall an average of 25 feet. In Liverpool, piers could not be built out into the Mersey River, as they could along the East River. At great expense, the city of Liverpool built gigantic stone basins with tidal gates. Nonetheless, ships could only enter or depart from the basins twice a day, during the few hours of high tide.

Map 2.1. Lower Manhattan Island and the East River, 1779. The numbers along the shoreline represent the depth of the rivers at low tide, in fathoms. Each fathom equals 6 feet. The shoreline of Manhattan Island is ideal for a port, with the water depth at low tide being 4 fathoms (24 feet). Source: “A Chart of New York Harbor, with the Soundings . . . ,” 1779, Map Division, New York Public Library

Another advantage to New York Harbor is that the currents in the Hudson and East Rivers and in the Upper Bay are not strong—only 3 or 4 miles an hour on the ebb tide, flowing south toward the Narrows and the Atlantic Ocean. The one exception was Hell Gate, the narrow passage up the East River, where the river turns to the east between Randall’s Island and the shoreline of New York’s borough of Queens, and then connects to Long Island Sound. Here the tide is particularly strong. Submerged rocks and ledges made the passage dangerous, especially for ships sailing in light winds, with the current running. Not until the 1880s did the US government, at great expense, blast the underwater rocks and clear Hell Gate.

Given the deep water just offshore, the Dutch first used the East River as the city’s port. From the Battery to Corlears Hook at Grand Street, where the river turns north to the Hell Gate, hundreds of ships crowded the wharves. Counting-houses, where the city’s merchant princes worked, lined the adjacent streets. A short walk away, grog shops and cheap boarding houses provided lodging for sailors, and prostitutes worked the streets.7

When the British finally gained control of New Amsterdam in 1674, they recognized the advantage of using the East River waterfront as the gateway to Manhattan Island. The population of the colonial city at the tip Manhattan Island grew throughout the eighteenth century. The city of New York’s population increased from 7,248 in 1723, to 13,294 in 1749, and to 21,863 in 1771, just before the American Revolution.8

New York did not dominate trade in the colonial period. In 1774, just before the Revolution, exports from the colonies to England totaled £804,286, with New York’s share at £80,008, about 10 percent of all exports. Exports from Baltimore and Charleston, which primarily consisted of tobacco, had a much higher value than the furs, timber, and agricultural products shipped from the city of New York. New York’s imports were significantly higher, totaling £437,937, or 28.6 percent of all imports.9

With the English in control, the city’s colonial government first sorted out legal issues surrounding both the ownership of property on Manhattan Island and control of the water around the island. The next step, if the port were to flourish, was to devise a way to build needed piers and wharves along the shoreline. Hendrik Hartog, in Public Property and Private Power, details the evolving legal status of the city of New York from 1686 to 1870.10 Two English governors, with the king’s permission, gave New York the charters that established the city as a corporate entity and defined the responsibilities of its government, as well as the rights and duties of its citizens.

In 1686, the Dongan Charter recognized New York as a corporate body, “Whereas the city of New-York, is an ancient city within the said province, and the citizens of the said city have anciently been a body politic and corporate.” The charter formally referred to the city’s government as the “Mayor, Aldermen, and Commonalty of the said Corporate city of New-York.”11 The charter also gave the city all of the “waste land”—the undeveloped land on the island—and specified that the city’s jurisdiction extended to “all the rivers, rivulets, coves, creeks, and water-courses, belonging to the same island, as far as the low water mark.”12 The Dongan Charter explicitly granted legal control of the shoreline and the surrounding water—out to the low-water line—to the city of New York.

Commercial activity along the shoreline of the East River continued to increase into the first years of the eighteenth century. As New York’s maritime commerce grew, so did the demand for space on the waterfront along the East River. Merchants and shippers pressured the British governors to grant the city the rights to the water surrounding Manhattan Island, in order to stimulate the development of the waterfront.

In 1730, Governor John Montgomerie granted a new charter, which established the city of New York as the local government, independent of the colony of New York. Legal scholars regard the Montgomerie Charter as the foundation for the government of the city. Into the twentieth century (and beyond), the charter “could be seen as the residual source of authority, as part of the ‘organic’ law of New York City.”13 Hartog describes the structure of the city’s government as a combination of public and private powers, a complex political arrangement that echoes into the twenty-first century.

A key part of the Montgomerie Charter granted the city the right to the land, then underwater, extending out from the shoreline for an additional 400 feet beyond the low-water line. The charter defined the underwater land around Manhattan as “water-lots,” the equivalent of the undeveloped “waste land” on the island, creating a public asset of immense value. Along the waterfront, the water-lots would provide additional space to build wharves and piers for the ships crowding the harbor. The adjacent waterfront streets would provide access and space for warehouses and business offices for the city’s merchants. All of this development required a significant investment, however, and some crucial questions still remained. Would the city of New York underwrite the cost of constructing a commercial waterfront at public expense, as Liverpool did, or would development be transferred to private owners? Would the development and regulation of the waterfront be decided by the city of New York, exercising its inherent political power, or would this be ceded to private interests?

The city of New York required its private citizens, in exchange for the privilege of being part of the “Communality,” to pave and clean the streets in front of their property or be penalized. Each year, the Common Council reaffirmed all local laws and published them in the Minutes of the Common Council. The laws listed in November 1731 include “A Law for Cleaning the Street Lanes and Alleys of the Said City” and “A Law for Paving the Streets, Lanes, & Alleys within the City of New York.”14

The Common Council declared that “the former Laws of the City Made for Paving the Streets within the same have been much neglected,” and, as a consequence, “the Intercourse of Trade . . . [is] thereby much lessened.”15 Visitors and residents complained constantly about the rutted streets, filled with garbage and turning to mud whenever it rained, creating an impediment to commercial activity. The Common Council placed the burden for paving the streets on the private property owners, stating “that all and Every the Citizens, Freeholders and Inhabitants that dwell in the Respective Streets Lanes & Alleys of this City, or are or shall be in Possession of any Lott or Lotts of Ground fronting any of them shall . . . Well and sufficiently Pave or Cause to be well and sufficiently Paved with good and sufficient Pibble Stones . . . and keep and Maintain the same in good Repair . . . directed by the Alderman and Assistant of each Respective Ward.”16 Thus all expenses for paving the streets and maintaining them in proper order were to be paid by the private property owners, not by the city.

With no municipal garbage system, the streets fronting each house became dumping grounds for commercial as well as private refuse, including human waste. In the mornings, people emptied their chamber pots in front of their homes. The city law for keeping the streets clean required that, on every Friday, the citizens “or [their] servants Rake and sweep together all the Dirt, Filth and soil lying in the Streets before their Respective dwelling Houses” and then have it carted away and “thrown into the [East] River.”17

The street-cleaning law also levied fines for throwing animal or human waste in the streets and asserted that if “any Person or Persons within this City do Cast, throw or Empty any Tubs of Dung, Close Stools or Pots of Ordure or Nastiness in any of the Streets of this City,” they would face a fine of 40 shillings, a substantial amount of money in the 1730s.18 The city ordered people to “empty their Ordures into the River and no where else.” From the Dutch settlement through the colonial era and until the late twentieth century, the rivers around Manhattan served as the city’s garbage dumps and sewers. Residents of New York in the 1730s were not unaware of the ecological damage caused by dumping raw sewage into the rivers. Human waste polluted the water around the docks, and commentators and merchants complained of the noxious smells. While the city ordered its citizens to keep the streets clean and dispose of human waste, it viewed cleaning the streets as a civic responsibility, not the role of government.

In the North American colonial world, no expectation existed that any level of government would undertake major public projects to build roads, wharves, or piers. City officials viewed their primary governmental responsibility as support for the growing commercial activity of the port. Persistent political pressure came from the shippers and merchants, whom George Edwards characterizes as “by far the most powerful” interest groups in the city. The rapidly growing trade in the Port of New York “brought wealth to many inhabitants. Sons usually followed fathers in an established mercantile business, so that family fortunes tended to increase. . . . Through common economic and family ties were formed combinations potent in politics as well as business.”19 Above all, the shipowners and merchant princes demanded that the city facilitate the development of the waterfront.

The city of New York controlled one incredibly valuable asset, the water-lots. It utilized water-lot grants to develop needed maritime facilities, built by private interests, using private capital, who expected private profits in return. As Hartog writes, “The property rights of the Montgomerie Charter [water-lots] were granted in pursuit of the goal of creating a major seaport in New York City.”20 The water-lot grants gave private individuals ownership rights to the underwater land along the shoreline out into the East and Hudson Rivers. Typically, the grants identify the city of New York as “the party of the first” and the grantee as “the party of the second.” They then define the terms: “do grant, bargain etc., unto said party of the second part, his heirs and assignees forever all that certain water-lot, vacant ground and soil under water to be made-land and gained out of the North [East River] or Hudson River.”

First the English kings and then, in the eighteenth century, the city granted these prized water-lots to favored individuals. The beneficiaries of the grants, usually the owners of adjacent shorefront property, “came to realize the significance of the newly acquired grant to the city [and] they became eager to purchase from the city the water lots which lay in front of their own property and thereby acquire that 400-foot territory . . . anticipating the commercial growth of the city.”21 In return, the grantees were obligated to extend the shorefront out into the rivers and construct, at their own expense, a new city street and a bulkhead wharf along the river. Private owners collected the wharfage fees ships paid to moor to the shore, in return for their legal agreement to maintain the bulkhead and wharves, as well as to keep the river along the shoreline dredged. All of the legal requirements of the water-lots had one purpose: to encourage private capital and private interests to build, maintain, and expand the city’s port facilities.

For example, Peter Lorillard’s grant, between Vestry and Desbroffes (now Desbrosses) Streets, required him to construct a new waterfront street, West Street, along the Hudson River. The new section of West Street was to be 70 feet in width, with “a good and sufficient firm wharf or street” for 380 feet along the Hudson. On this new shore, Lorillard was required to construct a wharf for ships to tie up to and, “at their [Lorillard’s] own costs, charges and expenses [to] uphold and keep in good order and repair the whole parts of said streets and wharf.”22 A final clause required that this new portion of West Street be perpetually “for the free and common use and passages of the inhabitants of said city.” Lorillard, in turn, could collect all of the wharfage fees from ships using the bulkhead, or wharf, he had constructed.

The real private gain for Lorillard, however, consisted of the two new parcels of made-land along West Street, to be added to the inland property he already owned between Vestry and Desbrosses Streets. Lorillard, like all the other water-lot grantees, held title in fee simple (i.e., absolute title) to the land created by filling in the waterfront and extending the shoreline out into the river. The city, in turn, had valuable real estate added to the waterfront, and it obtained the needed extra wharf space for maritime commerce to flourish.

In some cases, the grants specified an amount the grantees would pay the city for their water-lot. Fees varied from “one peppercorn” to the 24 pounds, 11 shillings Carlyle Pollock paid in 1799 for a water-lot on the Hudson River, between Rector and Carlyle Streets. In return, Pollock’s obligations included the requirement to, “within three years . . . at his and their own costs and charges and expense, build, erect, and make . . . a good, sufficient, and firm wharf or street seventy feet in breadth.”23 This 70-foot-wide street became West Street, the new shoreline on the western side of Manhattan. Pollock also agreed to fill in his water-lot and build a pier out into the Hudson River, if requested to do so by the city.

The Montgomerie Charter left the city with some regulatory power over the day-to-day operations of the port, however. While the water-lot grants transferred development of the port to private interests, the city retained the right to set wharfage fees, that is, the fees ships paid to tie up to the private docks. The city appointed dockmasters to allocate scarce wharf and pier space to the flood of ships arriving each day. The city also constructed a number of piers and ferry slips, at public expense, and leased them to private individuals to operate.

In order to rebuild the waterfront, the newly formed Department of Docks needed to identify and catalogue all existing grants. In 1871, the department prepared detailed maps of all the Manhattan water-lots, as part of their master plan for the waterfront. The mapmakers used the 1776 Ratzer map, drawn by British naval cartographers, as their base map, which included both high- and low-water lines—marking how far the high and low tides reached on land—for this section of the East River. Pearl Street (Queen Street in the colonial era) marked the original high-water line, and Water Street, a short block south, marked the low-water line. The made-land between Pearl and Water Streets came from the initial water-lot grants made by the English crown. Later grants created the new land between Water, Front, and South Streets, moving the shoreline 700 feet out into the East River.

Decades before the Montgomerie Charter, in 1686, King James II granted Peter De Lancey [sic] the city’s first water-lot, between Broad and Moore Streets along the East River.24 De Lancey was a Huguenot who married into the powerful Van Cortlandt family. In March 1722, King George granted a water-lot to Rip Van Dam and “18 others” between Coffee House Slip and Maiden Lane, creating two new city blocks between Water and Front Streets. The early grantees built Water Street and a bulkhead wharf between Old Slip and Maiden Lane. In turn, at their own expense, they filled in their water-lots between Pearl and Water Streets, forming 4 acres of new made-land along this section of the East River. Filling in the water-lots created real estate that belonged to the grantees, not to the city of New York, giving them a benefit of immense value. At the same time, the water-lot grants promoted the construction of a commercial waterfront.

Empowered by the 1730 Montgomerie Charter, the city of New York began to award water-lots. Anthony Rutgers obtained a grant from the Common Council for “water-lots along East River between the Great Dock and Whitehall, the Corner Lot on the East Side of the Street commonly called the Broadway.”25 Rutgers, a wealthy merchant, was among those most well-connected politically. In 1730, he was appointed by Governor Montgomerie to serve as an alderman in the Common Council, the same Common Council that granted him a water-lot.

In the next two decades, the city made only a few more grants, but in the 1750s, the number of grants increased to fifty-seven.26 On July 10, 1772, four years before the start of the American Revolution, the Common Council approved grants to the east of Rutgers’s water lot—extending to Coenties Slip—to seven individuals: Augustus and Frederick Van Cortlandt, Peter Jay, John Vredenburgh, Joris and Henry Remsen, Henry Holland, Waldron Blau, and William Milliner. The grants reflected the preference given to wealthy landowners along the shoreline, as all seven owned houses on Water Street. The growth of the city of New York and the construction of thousands of commercial and residential buildings ensured a steady supply of dirt and rubble to act as fill for the water-lots. Excavations for each new building created hundreds of carts’ worth of materials, which were dumped along the East River shoreline.27

Map 2.2. Water-lot grants on the East River, from Old Slip to Maiden Lane. Top: The earliest water-lots (1776), from Pearl Street to Water Street. Middle: Additional water-lots (1800–1850s), extending out to South Street. Bottom: The same area in 1857, with the water-lots filled in (i.e., made-land) and real estate developed on them, containing counting-houses, warehouses, factories, and tenements. Source: Created by Kurt Schlichting. Source GIS layer: historic street maps, New York Public Library, Map Warper.

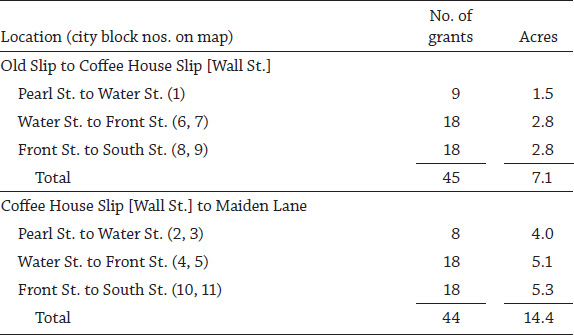

After the Revolution, the city continued to grant water-lots on into the early nineteenth century. Farther up the East River—between Old Slip, Coffee House Slip (now Wall Street), and Maiden Lane—a bewildering number of grants filled in the waterfront blocks from Pearl Street to South Street (map 2.2). The Department of Docks map identifies 149 water-lot grants. Between Old Slip and Maiden Lane, these water-lots added over 21 acres of made-land to Manhattan Island.

South Street became the new East River shoreline. The final step in the building of the city’s maritime infrastructure involved the construction of piers out into the East River. By the time of the Revolution, Water Street (then called Burnels Street) and Front Street defined the harbor frontage, with wharves along the two streets and a number of small piers out into the river. The original grantees of the city blocks filled in their water-lots from Pearl Street out to Water and Front Streets. At the foot of Maiden Lane, the Long Island ferry provided a connection across the river to Brooklyn.

Table 2.1.

Water-lot grants

Source: Water-lot grants, 92–61, box 1, folders 1–4, Department of Ports and Trade, New York City Municipal Archives.

In 1810, the Common Council designated South Street, extending farther out into the East River, as the new waterfront and then awarded fifty-four additional grants. Over time, the water-lot grantees filled in these new lots, creating six additional city blocks. To finance the building of the new South Street piers, the water-lot owners formed partnerships and shared the proceeds from the wharfage. They remained jointly responsible for maintenance and improvements. They were also required to keep the water depths between the piers dredged. The city of New York constructed Piers 15 and 16 for the ferry to Montague Street in Brooklyn and leased the operation of the ferry to a private company.

Over the next decades, commercial and residential development followed on this new made-land along the East River. By 1857, the made-land from Pearl to South Streets was filled with maritime-related businesses. Taverns and brothels served the sailors who manned the sailing ships that were tied to the piers in the East River. Tenements crowded Water and Pearl Streets, where longshoremen and their families lived in the crowded immigrant neighborhood along the East River. Tens of thousands of immigrants arrived in New York each year, and they found housing available, even though conditions in many of the tenements were wretched.

All of the five-, six-, and seven-story buildings on the 1857 map were privately owned. Some of the original water-lot grantees developed their property; others sold it to developers. They and their descendants drew great wealth from the teeming waterfront neighborhoods, which were built on made-land along the East River. The city’s original intent to develop a maritime infrastructure by granting water-lots had evolved to spawn real estate development along Manhattan’s shore.

Development of the East River waterfront continued up from the Battery to Corlear’s Hook, at Grand Street in the Lower East Side—a distance of over 2 miles. At Fulton Street, the city’s fresh fish market prospered, adding to the crush of business on South Street. From north of Corlear’s Hook to 14th Street, the city’s shipyards expanded and justly earned fame for the quality of the vessels constructed there, including the renowned packet ships. With the ever-increasing number of ships coming to the East River, the demand for space along the shore motivated speculators to press the city to grant more water-lots farther up the river.

Stuyvesant Cove—from 13th Street to 23rd Street along 1st Avenue—offered the last open area on the East River. The river narrowed beyond 23rd Street, and there was not enough space between the Manhattan shoreline and Blackwell’s Island (now Roosevelt Island) to build piers. Past the bend at 13th Street, Stuyvesant Cove had once reached as far inland as 1st Avenue. Eric Sanderson’s imaginative Mannahatta Project website superimposes his re-creation of the topology of Manhattan Island in 1609 over a Google street map, tracing the expansion of the island into the East River.28 The cove, once part of the Stuyvesant family’s land, which stretched from Bowery Street to the East River, provided a rural retreat where New Yorkers could fish and swim at a time when the city’s northern development ended at Canal Street.

Between 1825 and 1846, the city awarded four large water-lot grants for all the land underwater in Stuyvesant Cove. John Flack, an Irish immigrant and shipowner, and Nicholas Gouverneur, the scion of one the oldest and wealthiest Dutch families in New York, received a grant on August 1, 1825, for a major portion of Stuyvesant Cove. Their water-lot extended to the high-water line at 1st Avenue and included all of the underwater land from East 15th Street to East 23rd Street, an enormous area covering almost fifteen square city blocks (map 2.3, #1). The grant required Flack and Gouverneur to build “a good and sufficient firm wharf or street . . . from the Westerly to the Easterly sides,” extending out into the river from 15th Street through 22nd Street.29 From the south to the north, they would construct 1st Avenue, 80 feet in width, and then Avenues A, B, and C. Along the East River, Tompkins Street (later Avenue D) delineated the new shoreline, where the grantees would build a bulkhead for ships to moor alongside. The grant created approximately 58 acres of new made-land, potentially a fortune in real estate once the water-lots were filled.

The grant required Flack and Gouverneur, at their own expense, to extend the city’s street grid and, in addition, pay the city a yearly rent. That amount started at $346.13 on May 1, 1826, and increased in each succeeding decade until 1861, when the rent was capped at $1,846 a year. As with all water-lot grants, the grantees were expected to fill in all of the underwater land between the new streets, although the grant did not include a schedule for construction.

For the next nine years, Flack and Gouverneur did not even begin to build any new streets in Stuyvesant Cove. An 1834 D. H. Burr map of the East River shows the cove with no new streets, and the high-water line still at 1st Avenue. What the two partners did was to sell their water-lot to the New York Gaslight Company in February 1848 for $25,933.33. Perhaps they never had any intention of developing the land and instead used their water-lot grant for real estate speculation.

Map 2.3. Water-lot grants at Stuyvesant Cove, on the East River. The grantees and the dates of the grants (indicated by the numbers on the map) were John Flack and Nicholas Gouverneur (1), August 1, 1825; Hezekiah Bradford (2), June 22, 1846; Eliphalett Nott (3), May 13, 1844; and Charles and Henry Hall (4), February 18, 1825. Source: Created by Kurt Schlichting. Source GIS layer: 1870 water-lot map, New York Public Library, Map Warper.

The New York Gaslight Company produced manufactured gas to light the city’s streets and businesses. All of the city’s gas companies employed coal gasification technology to manufacture gas. Natural gas, today delivered by a complex network of underground pipelines from the Midwest, would not arrive in New York for decades. The coal gasification process heated coal at a high temperature in an enclosed boiler to generate gas, which was stored in large tanks and then distributed by pipes under the city streets. Coal gasification produced a toxic byproduct, coal tar, which the gas companies simply dumped into barges and emptied into the harbor. Manufactured gas itself smelled like rotten eggs, because of the sulfur in the coal. Only the poorest residents of the city lived near the gas plants.

The production of manufactured gas required large supplies of coal, so the gas companies were located along the riverfront. The New York Gaslight Company sold their property in Stuyvesant Cove to the Manhattan Gaslight Company. That company built a gas works along 14th Street and then, as the demand increased, expanded their facilities to fill four square blocks from 1st Avenue to the East River, between 20th and 22nd Streets. At 21st Street on the East River, the company constructed a long pier out into the river, where coal barges unloaded. In the 1860s, the area north of 14th Street along the East River became known as the Gashouse District. Two gas storage tanks towered off 1st Avenue and remained there until after World War II, with the construction of Stuyvesant Town. In 1883, all of the independent gas companies merged into the Consolidated Gas Company of New York and eventually became part of Consolidated Edison, or Con Ed, the largest public utility in the country.

Three additional grants in Stuyvesant Cove included one to Eliphalett Nott in 1884, for a narrow water-lot along 14th Street to the East River (map 2.3, #3). Nott’s made-land was first a gas works; later, when electricity came to New York, Con Ed converted it to a coal-fired generating station. Disaster struck in September 2012, when Superstorm Sandy inundated New York City. Water surged out of the East River and flooded that Con Edison facility. An enormous explosion followed, lighting up the sky and plunging Lower Manhattan into darkness. Damages exceeded millions of dollars, and Con Ed struggled for over a week to restore the power plant built on the made-land where once the clear waters of Stuyvesant Cove served as a bathing beach.

After World War II, the made-land in the cove became part of Metropolitan Life’s massive Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village housing developments, which, at the time, formed the largest housing project in Manhattan’s history. The complex, an 80-acre, tree-lined oasis on the Lower East Side, includes eighty-nine buildings with 8,757 apartments and over 25,000 residents. Most of the complex is built on the made-land that was once Stuyvesant Cove.

The use of water-lot grants to develop the waterfront of Manhattan Island for maritime industry added over 2,000 acres of new land, extending the shoreline out into the surrounding rivers. Stuyvesant Town illustrates the process of large-scale real estate development on the made-land. Yet in an era of climate change, another Superstorm Sandy would threaten the 25,000 people living on that land, highlighting the city’s vulnerability.

With the ever-increasing maritime commerce of the port, the East River waterfront could not provide all of the needed pier and wharf space, so the merchant princes turned to the other side of Manhattan Island. The process of creating new land and moving the shoreline outward had begun along the Hudson River before the Revolution. The city made a series of water grants, starting at the Battery and moving north to Rector Street between Greenwich and Washington Streets (see map 1.2). Originally, Greenwich Street fronted the shoreline at high tide. The new water-lots created made-land first between Greenwich and Washington Streets, and then from Washington to West Streets, repeating the pattern of expanding the city outward from the original shore, just as had happened along the East River.

The first grantees owned property along Greenwich Street. On October 28, 1765, the Common Council made grants to Oliver Delancey and Augustus Van Cortlandt. Once again the politically connected triumphed, as early critics had charged.30 Oliver Delancey was the brother of James Delancey, the governor of the colony of New York from 1753 to 1755. During the American Revolution, Oliver remained a staunch loyalist, became a brigadier general in the British army, and raised a battalion of loyalists to fight with the British. James Delancey’s estate, confiscated after the Revolution, became the Lower East Side, with Delancey Street as a main thoroughfare.

In the 1830s, the city designated West Street as the new shoreline along the Hudson River, and its water-lot grants between Washington and West Streets came with the same requirements: the grantees had to fill in the water-lots, construct a bulkhead, build and pave West Street, and construct wharves, all at their own expense. The grantees filled in the water-lots with refuse, and even abandoned ships, but the city’s construction boom provided the key, never-ending supply of fill. Excavating a cellar for a typical tenement—25 feet wide by 70 feet deep—produced approximately 520 cubic yards of dirt and rock that had to be carted away. Hundreds of horse-drawn carts moved the rubble to the river’s edge, to be used as fill.

As the Port of New York prospered, the demand for pier space along the Hudson River also continued to far outpace the supply. In the 1830s, the city continued to grant water-lots farther up the Hudson, almost to 30th Street. Shipping companies did not want to use piers above West 11th Street, the location of the Gansevoort Market, which supplied the city with food. This market occupied a four-block-square location, where numerous small schooners tied up to the bulkhead daily to deliver fresh food. In 1837, the city persuaded the New York State Legislature to move the shoreline of Manhattan farther out into the Hudson River. The new boundary on paper, 13th Avenue, extended from West 11th to 135th Streets and created the potential for a large number of new water-lots.

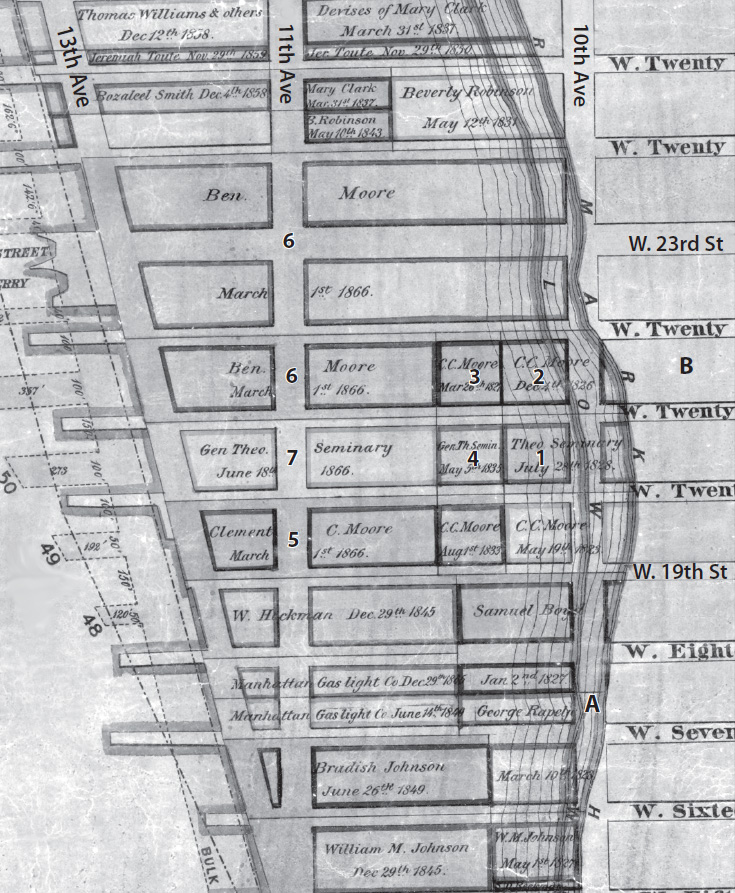

In the Chelsea neighborhood north of 14th Street, private waterfront property owners with the right political connections received valuable water-lot grants from the city of New York, some of which were on the expansive scale of those in Stuyvesant Cove. In 1823, Clement C. Moore, the author of “ ’Twas the Night before Christmas” and the son of the Episcopal bishop of New York, secured a number of water-lot grants to develop the shore of his Chelsea estate, which ran for four city blocks along 10th Avenue, between West 19th and West 24th Streets (map 2.4, section B). At the time of the American Revolution, Manhattan Island’s original shoreline ran along 10th Avenue and the Moore estate. Clement Moore’s first water-lots, in the 1820s, extended out into the Hudson River for only a few hundred feet. A second set of grants moved the shore farther west, toward 11th Avenue. In 1866, the year Moore died, he obtained another water-lot out to 13th Avenue. Moore’s son Benjamin was awarded an enormous water-lot of six city blocks (map 2.4, #6). The Moore family donated the land between West 20th and West 21st Streets to the General Theological Seminary, the seat of the Episcopal Church in New York. The seminary also obtained additional water-lots (map 2.4, #7) and used the property for new buildings. Over time, the Moore water-lots extended the original shoreline of the island over 1,230 feet out into the Hudson River at 19th Street and 1,530 feet at 24th Street, creating a huge addition of made-land. A hodgepodge of piers built along the new waterfront included the 33rd Street ferry slip to Jersey City.31

Map 2.4. Chelsea water-lot grants, 1826–1866. The grantees and the dates of the grants (indicated by the numbers on the map) were Clement C. Moore (1), May 19, 1823; Clement C. Moore (2), December 4, 1826; Clement C. Moore (3), March 26, 1827; Clement C. Moore (4), August 1, 1833; Clement C. Moore (5), March 1, 1866; Benjamin Moore (6), March 1, 1866; and General Theological Seminary (7), June 1, 1866. Source: Created by Kurt Schlichting. Source GIS layer: historic water-lots map, New York Public Library, Map Warper.

The Chelsea water-lots not only provided for additional piers from West 14th to West 34th Streets, but the made-land also dramatically expanded the size of the neighborhood, which became filled with private housing, tenements, warehouses, and factories. Longshoremen and immigrants settled in the neighborhood, just as they had along the East River. Beginning with the first water-lot grant in 1686, to Benjamin Moore’s Chelsea grants in 1866, and then continuing up the Hudson River to 30th Street and beyond, this process of private—not public—enterprise succeeded in building a maritime infrastructure around the entire southern half of Manhattan Island. Enabled by water-lot grants but financed by private capital, New York’s port dominated the maritime commerce of the country (see chapter 3). In the process, the island of Manhattan expanded out into the surrounding rivers and created a new waterfront world. For hundreds of years, the waterfront remained a place of ships, piers, sailors, and longshoremen. Today this waterfront world is a place with upscale housing and spectacular views.